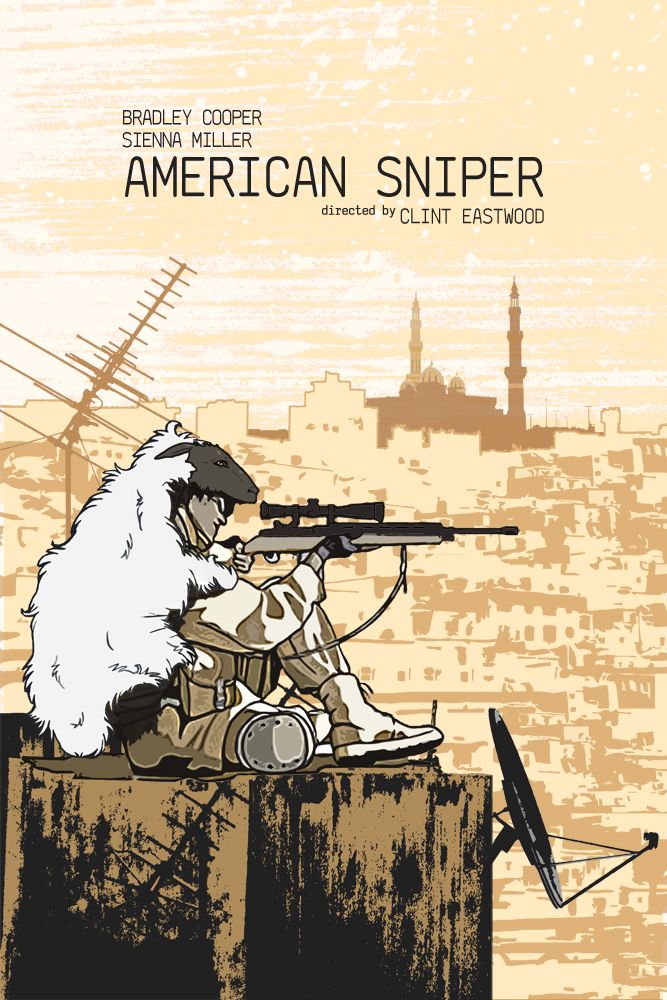

Sheep wolves and sheepdogs american sniper

American Sniper’s “wolves, sheep, and sheepdogs” speech has a surprising history with conservatives and the right wing.

Wolf, sheep, or sheepdog?Photo by Keith Bernstein © 2014 Warner Bros. Entertainment

This past weekend, American Sniper sold millions of tickets, and introduced millions of Americans to a novel turn of phrase. In an early scene set at the dinner table, Chris Kyle’s father tells him that there are three kinds of people in the world: “wolves, sheep, and sheepdogs.”

The scene is a canny invention by screenwriter Jason Hall, but he didn’t come up with that analogy. The origins of this sheepdog analogy help explain why the film has resonated with audiences. The sheepdog speech comes from Lieutenant Colonel David Grossman’s book On Combat, published in 2004. (It doesn’t appear in Kyle’s best-selling memoir, although the family and friends running Chris Kyle’s Twitter account did tweet about it in December.) Since then it has spread through military and police circles and the right-wing blogosphere. It’s proved particularly durable with gun rights groups. With the release of American Sniper, it has reached its largest audience yet.

Grossman crafted this analogy in response to 9/11 and the war in Iraq. And it’s not enough to classify the human race into these three simple categories; Grossman—and those who parrot his metaphor—are issuing a call to action to defend yourself against your enemies. In a country where innocent, unarmed, mostly black Americans keep getting killed, it’s a pernicious worldview to hold.

In Grossman’s original essay, now available on his website, he credits an “old war veteran” with first telling him about wolves, sheep, and sheepdogs. He writes:

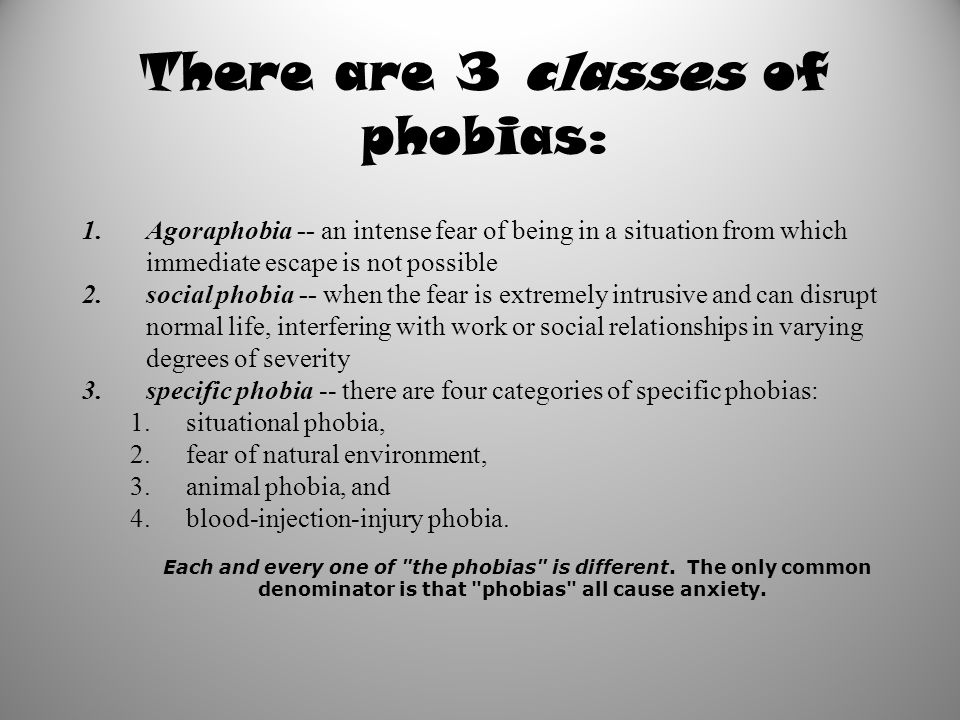

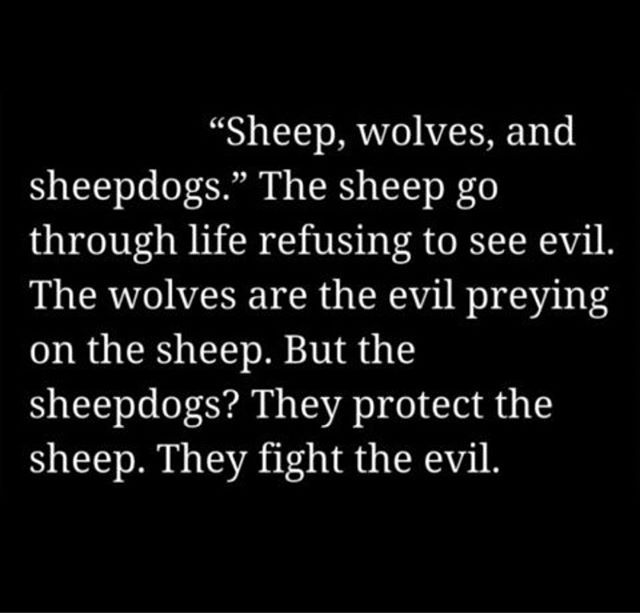

If you have no capacity for violence then you are a healthy productive citizen: a sheep. If you have a capacity for violence and no empathy for your fellow citizens, then you have defined an aggressive sociopath—a wolf. But what if you have a capacity for violence, and a deep love for your fellow citizens? Then you are a sheepdog, a warrior, someone who is walking the hero’s path.

In Grossman’s telling, the wolves will do anything they can to hurt sheep. Grossman variously identifies wolves as school shooters, terrorists, criminals, and anyone looking to hurt the innocent. Internationally, think ISIS, al-Qaida, and Boko Haram. Domestically, think gangsters, criminals, and thugs. Grossman makes it clear that, no matter how much society fears its sheepdog protectors, the sheep need their sheepdogs. That means that a sheepdog cannot “take out its teeth.” In gun rights terms, this means that gun owners should never go anywhere without a concealed firearm: “If you are a warrior who is legally authorized to carry a weapon and you step outside without that weapon, then you become a sheep, pretending that the bad man will not come today.”

Internationally, think ISIS, al-Qaida, and Boko Haram. Domestically, think gangsters, criminals, and thugs. Grossman makes it clear that, no matter how much society fears its sheepdog protectors, the sheep need their sheepdogs. That means that a sheepdog cannot “take out its teeth.” In gun rights terms, this means that gun owners should never go anywhere without a concealed firearm: “If you are a warrior who is legally authorized to carry a weapon and you step outside without that weapon, then you become a sheep, pretending that the bad man will not come today.”

And the wolf will come, says Grossman. “If you want to be a sheepdog and walk the warrior’s path,” he writes, “then you must make a conscious and moral decision every day to dedicate, equip and prepare yourself to thrive in that toxic, corrosive moment when the wolf comes knocking at the door. ” He emphasizes practicing “when/then” thinking as opposed to “if/when” thinking. He encourages sheepdogs to view their surroundings with fear and paranoia.

” He emphasizes practicing “when/then” thinking as opposed to “if/when” thinking. He encourages sheepdogs to view their surroundings with fear and paranoia.

Since the sheepdog analogy was published in On Combat, it’s been referenced or copied wholesale on countless military, special operations, and police blogs. It has been featured at least eight times on the Internet’s most popular military blog, BlackFive.net, as well as other popular milblogs like A Soldier’s Perspective, SOFREP, and This Ain’t Hell. And we’ve found dozens of other blogs that reference or link to Grossman.

Off the Internet the analogy has spread to T-shirts by at least four different companies, one of which calls itself “Sheepdog Inc. ” (Slogan: “Shirts for heroes who hunt down evil.”) It has inspired pastors of churches, and an organization called “Sheepdog Seminars for Churches” that teaches congregations self-defense. It has also been adopted as the name for many gun rights groups. There is even a sheepdog disaster-relief charity—like the Red Cross, but “small, flexible, and reactive” like a Marine Corps Quick Reaction Force. And the sheepdog analogy is all over social media.

” (Slogan: “Shirts for heroes who hunt down evil.”) It has inspired pastors of churches, and an organization called “Sheepdog Seminars for Churches” that teaches congregations self-defense. It has also been adopted as the name for many gun rights groups. There is even a sheepdog disaster-relief charity—like the Red Cross, but “small, flexible, and reactive” like a Marine Corps Quick Reaction Force. And the sheepdog analogy is all over social media.

While Grossman does have a Ph.D. in psychology, his analogy has zero basis in science. Good and evil aren’t scientific phenomena. While some humans have inclinations toward aggression and violence, it is not a gene that some people have and others do not. Yet Grossman still teaches more than 300 seminars a year on the sheepdog analogy and “conditioning the mind.” Conditioning it for what? We live in the safest times in human history. True “random acts of violence” are incredibly rare in our society; terror events rarer still. But the sheepdog analogy wouldn’t exist if people weren’t afraid

True “random acts of violence” are incredibly rare in our society; terror events rarer still. But the sheepdog analogy wouldn’t exist if people weren’t afraid

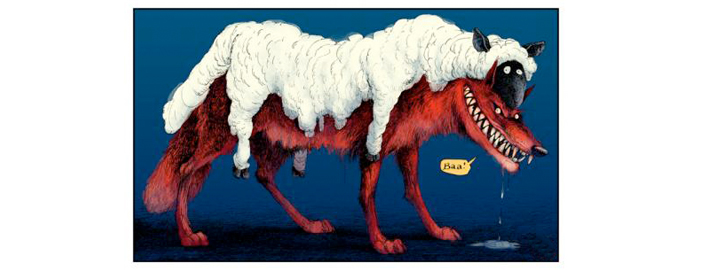

And people are afraid, so they take action. As a result, this simple analogy is undone by an even simpler (and older) one: the wolf in sheep’s clothing. After all, all humans basically look alike. Faced with this problem, how can you tell a wolf from a sheep?

The easiest way is race.

Chris Kyle, when he went to Iraq, spent zero time distinguishing the sheep from the wolves: Every Iraqi was a wolf. Kyle called Muslims “savages,” and described the unofficial rules of engagement of the battlefield simply: “If you see anyone from about sixteen to sixty-five and they’re male, shoot ’em. Kill every male you see.” That doesn’t sound like someone protecting the sheep (innocent Iraqi males) from the wolves (the insurgents).

Kyle called Muslims “savages,” and described the unofficial rules of engagement of the battlefield simply: “If you see anyone from about sixteen to sixty-five and they’re male, shoot ’em. Kill every male you see.” That doesn’t sound like someone protecting the sheep (innocent Iraqi males) from the wolves (the insurgents).

Domestically, black Americans are the victims of this analogy. White Americans, in general, view threats through the lens of race. Studies show that many Americans believe black men are the most dangerous group in America. Experiments, using first-person shooter video games, have shown that unarmed black men are more likely to be shot than their white counterparts by police officers. In other words, some “sheepdogs” tend to reflexively identify black people as “wolves.” Is it a coincidence that black men are 21 times more likely to be shot by police? Or that America has seen a rash of unarmed (mostly black) Americans killed by armed civilians in recent years?

In reality, some sheepdogs act an awful lot like the wolves. Take Jimmy Lewis Fennell, Jr., a police officer who was convicted of committing sexual assault on duty. If he’s not a wolf, then who is? And how does a sheepdog handle that threat?

And while the majority of veterans (sheepdogs through and through) return home to lead normal lives, some do not. (Statistically, veterans with PTSD do have higher rates of violent crime, though the vast majority of veterans do not commit crimes.) Have these sheepdogs turned into wolves, or were they always wolves?

We don’t want to paint police officers and veterans as “whackos” or evil. (One of the co-writers of this post is a veteran.) We want to point out how foolish, and potentially tragic, the distinctions between good “sheepdogs” and evil “wolves” really are.

(One of the co-writers of this post is a veteran.) We want to point out how foolish, and potentially tragic, the distinctions between good “sheepdogs” and evil “wolves” really are.

After leaving his service as a Navy SEAL and publishing his memoir, Chris Kyle started mentoring other veterans with PTSD. As the movie mentions in its conclusion, Chris Kyle was killed by another veteran, a Marine. Are Marines not sheepdogs? Or did Kyle’s killer turn into a wolf? Most importantly, as the analogy goes, why couldn’t Kyle tell the difference?

Because the analogy is simplistic, and in its simplicity, dangerous. It divides the world into black and white, into a good-versus-evil struggle that the real world doesn’t match. We aren’t divided into sheep, sheepdogs, and wolves. We are all humans.

We aren’t divided into sheep, sheepdogs, and wolves. We are all humans.

Ask Michael Brown. Ask Eric Garner.

Ask Chris Kyle.

- Movies

American Sniper and the Trope of the Sheepdog

The invasion of Iraq resulted in hundreds of thousands—perhaps even a million—people losing their lives. How can one attempt to justify so much killing?

Enter Clint Eastwood’s new film American Sniper.

Early in the movie , Chris Kyle’s father breaks life down for his infant son (who will grow to be the titular sniper):

There are three types of people in this world: sheep, wolves, and sheepdogs.

Now, some people prefer to believe that evil doesn’t exist in the world…those are the sheep. And then you got predators who use violence to prey on the weak. They’re the wolves. And then there are those who have been blessed with the gift of aggression, and the overpowering need to protect the flock. These men are the rare breed that live to confront the wolf. They are the sheepdogs.

This “wolves-sheep-sheepdogs” triad—the metaphor by which the film justifies Kyle’s bloody career—does not appear in Kyle’s autobiography. Rather, it comes from the work of military psychologist Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, best known for his 1995 text On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society.

In that book, Grossman suggests that, historically, most soldiers have not taken any human lives. In the heat of battle, he says, they tend to revert to an animal instinct that leads them to avoid deadly encounters with other members of their own species. In the natural world, competing males either posture to scare off rivals, or make a gesture of submission. During the Second World War, Grossman argues, most soldiers in close combat did the same: they fired their weapons harmlessly in the air or didn’t fire them at all. (The evidence he cites for this remarkable claim—primarily, SLA Marshall’s classic Men Against Fire—has been widely contested, but that’s another story.)

In the natural world, competing males either posture to scare off rivals, or make a gesture of submission. During the Second World War, Grossman argues, most soldiers in close combat did the same: they fired their weapons harmlessly in the air or didn’t fire them at all. (The evidence he cites for this remarkable claim—primarily, SLA Marshall’s classic Men Against Fire—has been widely contested, but that’s another story.)

Grossman’s book On Killing was hailed by some progressives as a defense of humanity against the more common libel—that, as a species, we can be easily encouraged to gleefully slaughter each other, given the right circumstances. But Grossman’s fans fundamentally misunderstand his project. He is not a pacifist, but a soldier; On Killing is less a celebration of non-violence than it is a how-to guide.

Grossman claims that modern armies had, without really understanding how, developed techniques to break down our natural resistance to killing. So, in a sense, his work merely theorizes about what our militaries are already doing. But he also argues that there is a certain percentage of men who, he said, don’t need such guidance to be able to kill. That’s the basis of the “sheepdog” trope. In his 2004 book On Combat, he explains:

So, in a sense, his work merely theorizes about what our militaries are already doing. But he also argues that there is a certain percentage of men who, he said, don’t need such guidance to be able to kill. That’s the basis of the “sheepdog” trope. In his 2004 book On Combat, he explains:

If you have no capacity for violence then you are a healthy productive citizen: a sheep. If you have a capacity for violence and no empathy for your fellow citizens, then you have defined an aggressive sociopath—a wolf. But what if you have a capacity for violence, and a deep love for your fellow citizens? Then you are a sheepdog, a warrior, someone who is walking the hero’s path. Someone who can walk into the heart of darkness, into the universal human phobia, and walk out unscathed.

All of American Sniper can be summed up in those last two sentences.

Grossman has built a career running training sessions about killing for soldiers and police and really any other people who “walk the warrior’s path. ” As he writes in On Combat, “If you in a war, you are a warrior. Is there a war on drugs? Is there a war on crime? Is there a war against terrorism?… Then you are in a war and you are a warrior.”

” As he writes in On Combat, “If you in a war, you are a warrior. Is there a war on drugs? Is there a war on crime? Is there a war against terrorism?… Then you are in a war and you are a warrior.”

It’s worth thinking through these metaphors, particularly now that they’ve hit the big screen. What does it mean to call men with guns “sheepdogs”? Obviously, it makes the rest of us, as Grossman explains, “sheep,” feeble herd animals who require shepherding. We could never do what the warriors do—indeed, we can’t even comprehend it. “The sheep live in denial,’ writes Grossman, “that is what makes them sheep. They do not want to believe that there is evil in the world.”

This system is, more or less explicitly, a program for permanent militarism; by definition, the sheep can’t govern the sheepdogs. In American Sniper, the Kyle character has no time for those who question the value of the Iraq catastrophe. There’s evil in Baghdad; therefore, he must kill people, irrespective of the baah-ing of the flock.

Moreover, the metaphor provides a justification for military violence as an end in itself. That’s the whole message of American Sniper. By shooting hundreds of people, did the Chris Kyle character make the world a better place? Within the logic of the film, this question makes no sense. Kyle is a sheepdog precisely because he performs acts that most of us wouldn’t. The men he shoots matter only insofar as they reveal Kyle’s nature. Kyle’s ability to kill becomes, in and of itself, an act of heroism—one that doesn’t require external justification from those who can’t, by definition, understand it.

The Iraq War cost the U.S. trillions of dollars and devastated Iraq. But it did provide lots of opportunities for killing—something that American Sniper presents, to extraordinary box office success, as a kind of victory. Of course, that’s the other corollary of seeing the public as sheep. You’re always looking for opportunities to fleece them.

"American Sniper": We are fair sheepdogs

So the famous Clint Eastwood was noted for his work on standard military propaganda, releasing his film "American Sniper". Based on the book by Christopher "Shaitan" Kyle, the famous horror sniper who reportedly killed 160 people during the invasion of Iraq, the film is traditionally jingoistic, with a set of typical clichés. There is no story about the war and even the history of a man in the war in the picture, and the main line has become the traditional direction "how ours bring peace to the barbarians in Iraq." However, such agitation is far from the first in Hollywood film distribution. nine0003

Based on the book by Christopher "Shaitan" Kyle, the famous horror sniper who reportedly killed 160 people during the invasion of Iraq, the film is traditionally jingoistic, with a set of typical clichés. There is no story about the war and even the history of a man in the war in the picture, and the main line has become the traditional direction "how ours bring peace to the barbarians in Iraq." However, such agitation is far from the first in Hollywood film distribution. nine0003

So, on a Texas farm, there lived such a “shirt-guy”, participated in rodeos, shot accurately and drank beer in a bar. Suddenly, after watching TV, in particular, news from Iraq and the tragedy of September 11, Chris wakes up with "patriotic feelings", and he joins the army to bring, as they say throughout the film, to the "barbarians" the light of American democracy.

By the way, the traditional superiority of the opinion of an ordinary US citizen over other opinions is shown quite typically. This was clearly explained to Chris by his father when he made it clear that his deeds must be fair. nine0003

Chris's father (4th minute of the film):

“There are people who don't know how to protect themselves - these are sheep. There are predators who, with the help of violence, devour the weak - these are wolves. And there are people endowed with both aggression and a great need to protect their herd - these are shepherd dogs.

Whom Chris considered himself to be, and who the director presents the American soldiers as, is not hard to guess. Throughout the film, the thread of the message “we are not bad, we are just” is stretching, which is expressed in the active suppression of those who think otherwise. And, typically, there is no explanation in the film of the reasons for the invasion of Iraq, not even a mention of missions to control the presence of chemical weapons, which were never found. The whole essence of the war is illustrated by Chris's personal opinion and his so-called "patriotism". nine0003

So, having arrived in Iraq as a sniper, the main character begins to destroy people at a truly Stakhanovite pace, regardless of whether it is a man, a woman or a child. By the way, the target audience of this picture immediately becomes “clear” that 99% of the inhabitants of Iraq are inveterate terrorists right from the cradle, which is clearly shown by the example of a little boy trying to lift a heavy RPG-7, or a woman hiding an anti-tank grenade under her hijab.

By the way, the target audience of this picture immediately becomes “clear” that 99% of the inhabitants of Iraq are inveterate terrorists right from the cradle, which is clearly shown by the example of a little boy trying to lift a heavy RPG-7, or a woman hiding an anti-tank grenade under her hijab.

Meanwhile, Chris is waiting at home for his pregnant wife, who, by the way, can be called the positive hero of the film, in contrast to the sniper. Chris returns home, the baby is born, but the sniper's thoughts are still on the war, where, as he believes, his "duty" is to be. The wife, on the contrary, believes that Chris's duty is the family, and suffers greatly from separation, realizing that her husband is just a cog in another planned meat grinder. nine0003

Four times Chris went to Iraq and finally, watching the death of his fighting friends and surrendering to his wife's requests to return, he still goes home forever, to raise two children already. But before leaving, Chris kills the formidable Iraqi sniper Mustafa, who, as shown in the film, became an exception to the "barbarian-Iraqi" rule, killing several fighters from the Navy SEAL squad in which Chris served.

As a result - a "wonderful" propaganda picture for the US Armed Forces.

"Shaitan" - the legend of the Iraqi war, who killed more than one and a half hundred people, enjoys universal respect and is presented as an example to follow. To give Chris at least a little humanity, Eastwood literally screwed a contrasting line of wife and children into the picture, and designed the ending in the style of "the perfect dad and hero of the United States." nine0003

So the target audience of the film can applaud – the campaign was a success, and we can expect new volunteers to replenish the ranks of the army, to whom, like in the film, no one will explain the goals and reasons for “defending the motherland” even on the other side of the globe. What for? The classic pretext of "fighting terrorism" can justify an invasion even on Mars, and even if the grass doesn't grow there... nine0003

What does the film teach us?

The film "teaches" us the typical concept of "colonial patriotism" known since the Middle Ages. For a long time, films about the heroes of foreign wars were not made in the USA, and recruits with powdered brains are always needed.

Quotes from the movie The Sniper (2014)

Add a quote

There are three types of people in this world: sheep, wolves and sheepdogs. Some prefer to believe that evil does not exist in our world, and if it suddenly appears on their doorstep, they will not be able to defend themselves - these people are sheep. There are also predators, they use violence to oppress the weak, these are wolves. The third type is those who are naturally endowed with the gift of aggression and the need to protect the weak - these are people of a rare breed, born to repel wolves - these are shepherd dogs. nine0003

- Dee, what the hell are you doing in my group? Everyone knows black people can't swim.

- All right, sir, I'm not black.

- What?

- I'm new-black. I run slowly, jump low, swim well and shop at the Gap. All white people are proud of me when I fuck their women. I drink them regularly.

All white people are proud of me when I fuck their women. I drink them regularly.

- Do you really have guys, is it always like this: three beers - and you are no longer married?

- Personally, after three bottles, I only think about the fourth. nine0003

- A real rustic.

- I'm not a redneck, I'm from Texas.

- What's the difference?

- We ride horses, and they ride their cousins.

There are three things to be afraid of: your ego, alcohol and women.

Aim for the button and you miss by a couple of centimeters, aim at the shirt and you miss by a couple of meters.

“I can't help but think of that pink dress you wore on your honeymoon. nine0047 - Yes, it's called a negligee. And three days is not considered a honeymoon.

- Saw?

- Announcement. Yes, I saw it, sir.

Yes, I saw it, sir.

- You are now the most wanted man in Iraq, they give 180,000 dollars for your head, congratulations!

- Just don't tell my wife, otherwise she'll call this number.

When I was little, there was an electric fence near our house. We had a game: who will grab it and last longer. War is very much like this - it sends electricity through you and forces you to hold on tight. nine0003

war

If you think war doesn't change you, you're wrong.

Fame is something some people strive for and others stumble over with no hope of finding it.

The smaller the target, the more accurate the shot.

- Stop, be afraid. lady. Hands up, give away your laundry, slowly and carefully.

- Can I tell you something? nine0047 - Repent, sinner.