Psychology security blanket

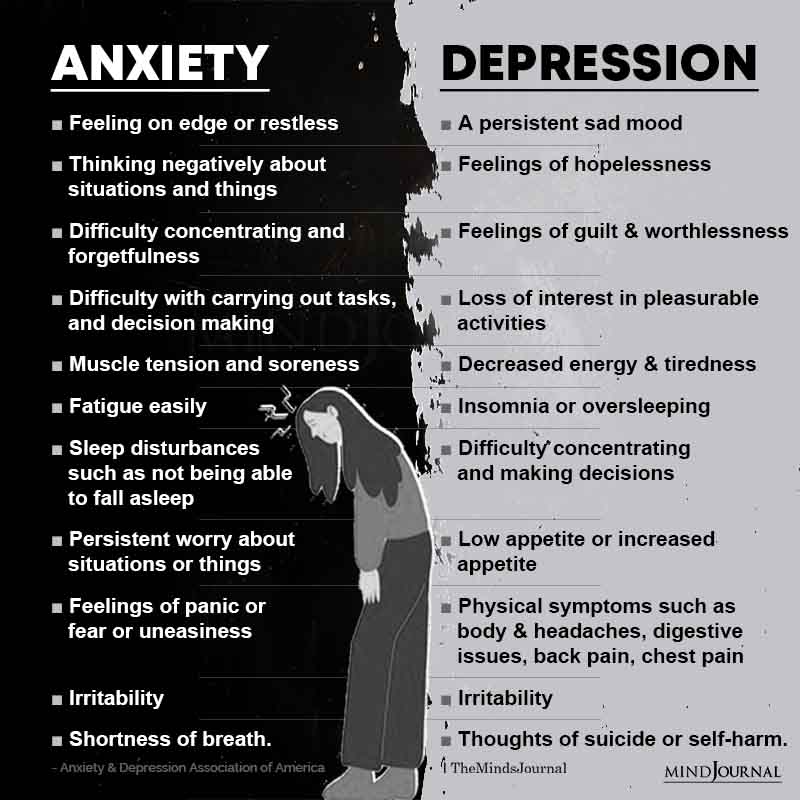

What Science Reveals About A Child's Lovey or Security Blanket

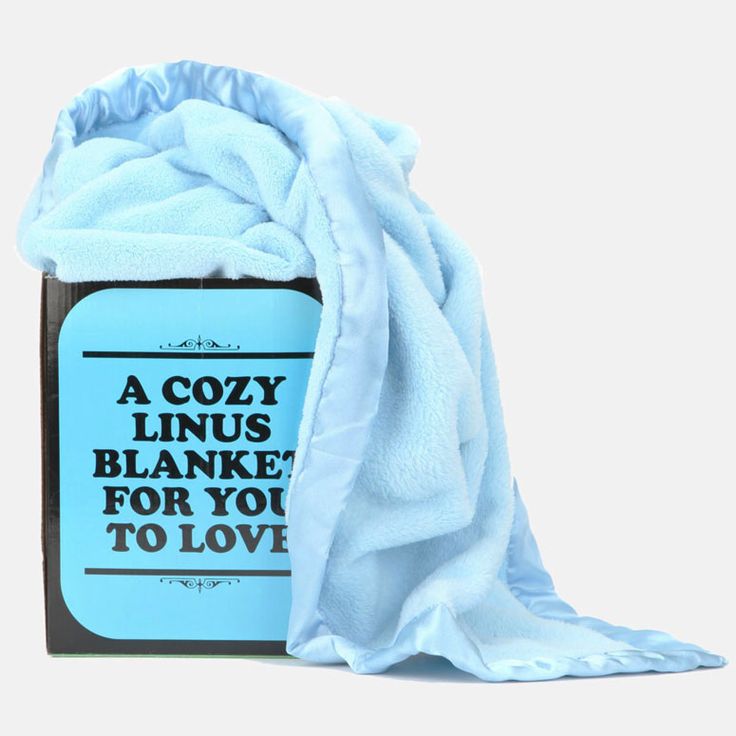

We all remember Linus from the Peanuts – confident, caring, smart, and still carrying a blanket around everywhere. While Linus is endearing, we all wonder if letting children indefinitely carry blankies aka security blankets or loveys will harm their development.

Will they face judgment from peers? Will they struggle to make friends? Will they lack the independence of other children?

These are daunting questions. The great news is that these fears and questions are unfounded, and science shows that these objects are tools that children naturally gravitate toward.

Research shows that a child’s security blanket or beloved teddy is actually a good thing. Turns out, blankies and loveys are a tool to boost a child’s confidence level, self-value, and they are even empowering.

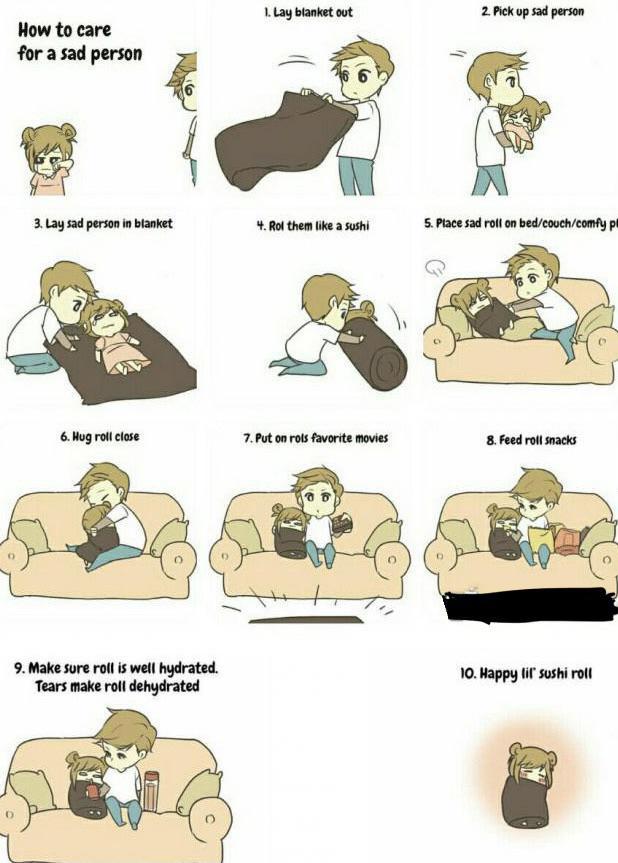

Why? Blankets and loveys are a sense of security for children — a way to help them leave their parent or caregiver for the day, to work through the tears of an emotional moment, and to handle those tough transitions that they need extra support with. With that blanket or lovey in tow, they are “less shy and more focused than children who don’t use these things.”

While added focus and being less shy are great benefits in and of themselves, there is even more good news about the advantage of letting children have blankies and loveys. Research also tells us that “their lovey objects are like the first training wheels for telling themselves ‘you’re all right’. With a built-in sense of security, children feel safe enough to take small risks, explore and grow.”

Training wheels provided a safety net which increases confidence and then are shed when no longer needed.

By taking small risks, children will feel free and unafraid to transition to taking larger risks as they grow and change.

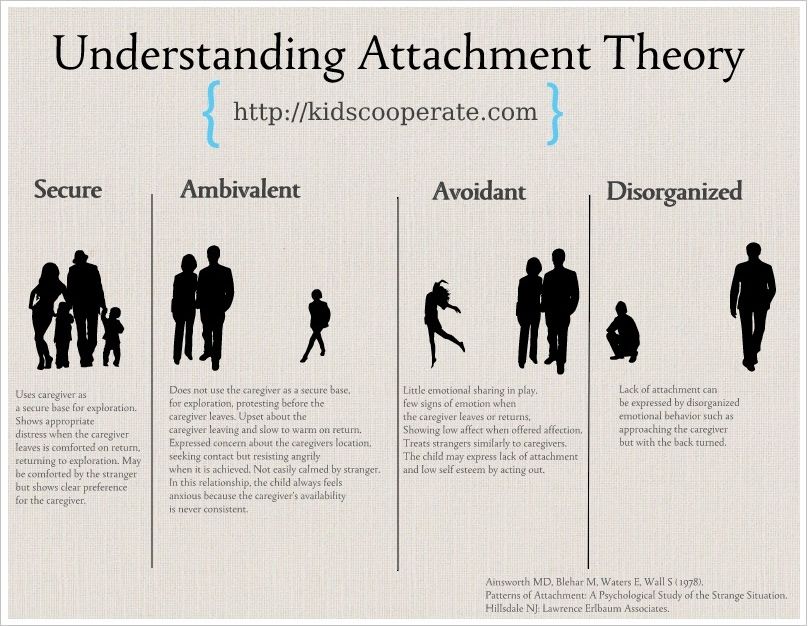

Security Blankets as Transitional ObjectsThe debate about the value of security blankets and other lovey objects has been taking place since 1951, the same year in which the term transitional object was first used by D. W. Winnicott.

W. Winnicott.

Winnicott defines the term transitional object as “a designation for any material to which an infant attributes a special value and by means of which the child is able to make the necessary shift from the earliest oral relationship with mother to genuine object-relationships.”

In simpler terms, this means that security objects:

- Empower children

- Help children make connections outside of their parents

- Help navigate separation for a child

- Indicate how children will create human friendships

According to Psychology Today, security objects are “rooted in sensorial elements that lessen the stress of separation, while they soothe and comfort the child.” Each aspect of the item — from how it smells, to feeling the worn spots, to the faded color — is part of the unique relationship between the security object and the child. Not only does the security blanket or lovey act as a comfort, but it has become a physical keepsake of memories and nostalgia.

With all these positives coming from security blankets and loveys, it is difficult to know when to take your child’s lovey away or even if you should take this away. As adults, we can feel apologetic or worried about how our child’s lovey will be received by others. Our own insecurities may lead us to take away our child’s beloved object.

However, research has shown that if the transitional object is removed or denied access to, it can actually create more anxiety and trauma. It is better to support the child by using the security blanket or lovey at key times.

Use reassuring statements to let the child know that it will be waiting for them.

Put your blanket in your cubby, and it will be waiting for you at nap time.

At home you can pick up the special object when it is not being used and place it somewhere the child can easily have access to it when they are needing extra emotional support.

Your blanket is waiting for you on your bed.

While it can be uncomfortable for us as adults, children need the freedom to discard their object when they are ready.

Bottom line, blankies, loveys, or any other transitional object are a positive tool for children. Security blankets, loveys, and similar items:

- Foster independence and security

- Ease anxiety in new situations

- Help children as they transition to different life stages

- Create self-worth and awareness

- Invite emotional wellbeing

The truth is that even adults find benefits from security objects.

I still have my own lovey tucked away at the bottom of my dresser. He smells like my childhood. He reminds me of innocence, safety, and security.

Even our friend Linus always had great friends and was a respected leader among his peer group. So, no need to worry.

Children benefit greatly from their blankies and loveys and will let them go when they are ready.

- Author

- Recent Posts

Editor

This was made by the combined efforts of the Preschool Inspirations team!

Latest posts by Editor (see all)

Even Grown-Ups Need Security Blankets

When Kaitlin Lipe was 6 months old, someone gave her a Puffalump. The stuffed pink cow is more than two decades old now, but Lipe, 24, a social media manager in New York, can't part with Puff. She gets comfort wrapping her arms around the childhood toy without all the meowing that comes from her real cat or the sassy comments she might get from her boyfriend.

The stuffed pink cow is more than two decades old now, but Lipe, 24, a social media manager in New York, can't part with Puff. She gets comfort wrapping her arms around the childhood toy without all the meowing that comes from her real cat or the sassy comments she might get from her boyfriend.

"She is a reminder of my childhood, has always been a comfort to me, and is in every way a symbol for the happier times in life," Lipe told LiveScience.

Lipe isn't alone in her affection for what psychologists call a "security" or "transitional" object. These are objects that people feel a bond with, despite the fact that the relationship is, by definition, one-sided.

And while it may not be the social norm for grown-ups to lug around teddy bears, adults regularly become attached to inanimate objects in a manner similar to a child's grip on a security blanket, researchers say.

Plush security

There are no precise numbers on how many people carry a love for their childhood blankie into adulthood, but a survey of 6,000 British adults by the hotel chain Travelodge in August found that 35 percent admitted to sleeping with stuffed animals.

The survey is perhaps not the most scientific, but the phenomenon of adults with security objects is "a lot more common than people realize," University of Bristol psychologist Bruce Hood told LiveScience. Hood has studied people's sentimental attachments to objects, and he said the studies never lack for participants.

"We've had no problem finding adults, especially females, who have their child sentimental objects with them," Hood said.

A 1979 study by psychologist and security object expert Richard Passman, now retired from the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, found that around 60 percent of kids are attached to a toy, blanket, or pacifier during the first three years of life. Until kids reach school age, there is no gender difference in attachment, but girls tend to pull ahead around age 5 or 6, probably because of social pressure on boys to put away soft toys, Hood said.

Until the 1970s, psychologists believed that these attachments were bad, reflecting a failing by the child's mother.

But research by Passman and others began to contradict that notion. One study published in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology in 2000, for example, found that kids who had their beloved blankets with them at the doctor's office experienced less distress, as measured by blood pressure and heart rate. Apparently, security blankets really do live up to their name.

Even as the need for a security object fades, the attachment may linger. One small study of 230 middle-school students, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry in 1986, found that while 21 percent of girls and 12 percent of boys still used their security object at age 13 or 14, 73 percent of the girls and 45 percent of the boys still knew where the object was.

The essence of an object

So why might grown-ups harbor affection for a ratty old blanket or well-worn stuffed dog? Part of the reason is probably nostalgia, Hood said, but there seems to be a deep emotional attachment to the objects as well.

It's called "essentialism," or the idea that objects are more than just their physical properties.

Consider: If someone offered to replace a cherished item, like your wedding ring, with an exact, indistinguishable replica, would you accept? Most people refuse, Hood said, because they believe there is something special about their particular ring. It's the same reason we might feel revulsion at wearing a shirt owned by a murderer. Objects are emotional.

Belief in essentialism starts early. In a 2007 study published in the journal Cognition, Hood and his colleagues told 3- to 6-year-old children that they could put their toys in a "copy box" that would exchange them for duplicates. The kids didn't care whether they played with originals or duplicates of most toys, but when offered the chance to duplicate their most cherished item, 25 percent refused. Most of those who did agree to duplicate their beloved toy wanted the original back right away, Hood reported. The kids had an emotional connection to that blanket, or that teddy bear, not one that looked just like it.

Even in adulthood, those emotions don't fade. In a study published in August 2010 in the Journal of Cognition and Culture, Hood and his fellow researchers asked people to cut up photographs of a cherished item. While the participants cut, the researchers recorded their galvanic skin response, a measure of tiny changes in sweat production on the skin. The more sweat, the more agitated the person.

The results showed that participants had a significant stress response to cutting up pictures of their beloved item compared with cutting up a picture of a valuable or neutral item. People even became distressed when researchers had them cut up a picture of their cherished item that was blurred past recognition.

Mine, mine, mine

Researchers know little about what's going on in the brain to bond us to certain objects. Hood is now using brain imaging to investigate what goes on when people watch videos of what looks like their cherished objects being destroyed.

However, studies on marketing and purchasing decisions suggest that our tendency to love objects goes beyond the soft and cuddly. [World's Cutest Baby Animals]

A 2008 study in the Journal of Judgment and Decision Making revealed that people who held onto a mug for 30 seconds before bidding for it in an auction offered an average of 83 cents more for it than people who held the mug for 10 seconds.

The effect is even greater when the item is fun to touch, said Suzanne Shu, a professor of behavioral sciences in the school of management at the University of California, Los Angeles. She's done studies finding that people get more attached to a pen with a "nice, smooshy grip" than an identical, gripless pen.

The findings seem to be an extension of what's called the "endowment effect," or people's tendency to value things more when they feel ownership over it, Shu said.

"Part of the story of what happens with touch is it almost becomes an extension of yourself," she said. "You feel like it's more a part of you, and you just have this deeper attachment to it."

"You feel like it's more a part of you, and you just have this deeper attachment to it."

Whether this touch-based attachment might relate to the love people feel for snuggly childhood teddy bears, no one yet knows. But human relationships to objects can certainly be long-running and deep.

"She's been there for me when I've been sick, when I've been lonely and when I really needed a hug and no one was around," Lipe said of her stuffed cow, citing the characters from Pixar's Toy Story movies: "She's the Woody and Buzz to my adulthood, really, a reminder of my past and definitely a connection to my family."

- 7 Ways the Mind and Body Change with Age

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About You

- Weighted Blankets: How They Work

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Weighted blanket: benefits and harms, principle of operation, how to choose weight

Trends

TV channel

Pro

Investments

Events

RBC+

New economy

Trends nine0003

Real estate

Sport

Style

National projects

Town

Crypto

Debating Club

Research

Credit ratings nine0003

Franchises

Newspaper

Special projects St. Petersburg

Petersburg

Conferences St. Petersburg

Special projects

Checking counterparties

RBC Library

Podcasts

ESG index nine0003

Policy

Economy

Business

Technology and media

Finance

RBC CompanyRBC Life

RBC Trends

Photo: Shutterstock

In recent decades, sleep has been rethought with new technologies. One of them is weighted blankets. We understand whether they effectively fight insomnia and other problems

How it works

Weighted blankets differ from ordinary blankets in their greater weight: from 2 to 15 kg. The pressure from the extra mass triggers a special effect called Deep Sensory Pressure (DSP). It is believed to be relaxing and may be beneficial to the nervous system, which is why DSP is a key pressure therapy practice that has been used for decades, for example, to treat people with autism spectrum disorders or those with intellectual or mental delays or disabilities. Moreover, DSP can be used not only during sleep: sometimes weighted vests and even special help dogs are used. nine0003

The pressure from the extra mass triggers a special effect called Deep Sensory Pressure (DSP). It is believed to be relaxing and may be beneficial to the nervous system, which is why DSP is a key pressure therapy practice that has been used for decades, for example, to treat people with autism spectrum disorders or those with intellectual or mental delays or disabilities. Moreover, DSP can be used not only during sleep: sometimes weighted vests and even special help dogs are used. nine0003

Effect

Volunteers who regularly used weighted blankets as part of the experiment compared their effect to the feeling of being hugged or held in their arms. In recent decades, studies have been conducted repeatedly on how effectively weighted blankets alleviate various symptoms of disorders and diseases. The results of some experiments already indicate that the use of such blankets is useful, since sleeping with them is able to:

- Alleviate the perception of pain.

nine0083 In a recent study, 94 volunteers with chronic pain used either a regular light blanket or a weighted blanket for a week. It turned out that the perception of pain in people from the latter group was facilitated, especially if it was previously accompanied by anxiety.

nine0083 In a recent study, 94 volunteers with chronic pain used either a regular light blanket or a weighted blanket for a week. It turned out that the perception of pain in people from the latter group was facilitated, especially if it was previously accompanied by anxiety. - Improve sleep quality. There are many variations of sleep problems with many more causes. Weighted blankets help to cope with them, as the pressure calms and stabilizes the pulse. This makes it easier to fall asleep. nine0084

- Reduce anxiety . Numerous studies by scientists from different countries have repeatedly proven that weighted blankets help reduce anxiety levels - also by lowering the heart rate.

- Reassure a person before a frightening event, such as a medical procedure. In several studies, scientists gave weighted blankets to people who were about to have tooth extractions. Their excitement from the upcoming event decreased several times.

nine0084

nine0084 - Relieve symptoms of depression. In a 2020 Swedish study, 120 volunteers with depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, and ADHD used weighted blankets for a month. They found that their symptoms of depression (as well as weakness and anxiety) were reduced.

No panacea

But do not think that a weighted blanket is a universal cure for depression or anxiety. It can only alleviate the symptoms. Martin Anthony, professor of psychology at Ryerson University in Toronto, says: “I am absolutely convinced that weighted blankets can be soothing and relaxing for many people. However, this does not mean that they have any long-term effects or that they can be used to fully combat anxiety.” nine0003

Whom the blanket may be harmful for

There are not many risks or potential side effects associated with using weighted blankets. However, do not cover them with children under two years old - for them it can be dangerous. In addition, blankets can negatively affect people with the following problems:

- Sleep apnea.

This condition causes intermittent breathing difficulties at night, and a weighted blanket can exacerbate this problem.

This condition causes intermittent breathing difficulties at night, and a weighted blanket can exacerbate this problem. - Asthma - for the same reason. nine0084

- Claustrophobia. The fear of closed or cramped spaces may be exacerbated by the weight of the blanket.

How to Determine the Correct Weight for a Weighted Blanket

The weight of a weighted blanket should be approximately 5-10% of your body weight. Its area should not exceed the size of the bed.

- Adults can use weighted blankets that weigh between 2 and 15 kg.

- For a child weighing between 9 and 32 kg, a blanket weighing between 1.5 and 3.5 kg is suitable. nine0084

- For a child weighing up to 60 kg, it is better to use a blanket weighing between 2 and 7 kg.

- For the elderly, it is better to use a weighted blanket weighing between 2 and 3.5 kg.

Updated on 09.12.2022

Text

Semyon Bashkirov

Top of the trend

Related materials

nine0000 Sleeping under a blanket is psychologically necessary for us even in the heat

Tags

Home Summer Bed Psychology Sleep Despite the season, every night we fall asleep sweetly in bed, wrapped in a soft warm blanket. Even if it is very hot, we have some inexplicable need to cover ourselves with at least a sheet, otherwise there is no way to fall asleep. So why, when all the windows are wide open to lower the temperature in the room, do we still take and cover ourselves with a blanket? Today revision "So Easy!" will tell you how sleeping under a blanket affects a person and why we can’t do without shelter.

Even if it is very hot, we have some inexplicable need to cover ourselves with at least a sheet, otherwise there is no way to fall asleep. So why, when all the windows are wide open to lower the temperature in the room, do we still take and cover ourselves with a blanket? Today revision "So Easy!" will tell you how sleeping under a blanket affects a person and why we can’t do without shelter.

© Depositphotos

There are several reasons why we feel the need to wrap ourselves in a blanket. If it seems strange to you that some people sleep under a winter blanket even in summer, there is an explanation for this. Whether it's a blanket, a thin sheet or a blanket, we will definitely wrap ourselves in it. As it turned out, there are more psychological reasons for this action than physiological ones. nine0003

© Depositphotos

The blanket regulates body temperature

Man is a warm-blooded creature. This means that thanks to thermoregulation, we stay warm. In the phase of deep sleep, our control disappears, so in order not to freeze, we take cover with a blanket. Too cold in the room or too hot, a blanket will help maintain the right body temperature.

This means that thanks to thermoregulation, we stay warm. In the phase of deep sleep, our control disappears, so in order not to freeze, we take cover with a blanket. Too cold in the room or too hot, a blanket will help maintain the right body temperature.

© Depositphotos

A comfortable temperature is the key to sound healthy sleep. If the room is too hot or too cold, the body will work in an enhanced mode to keep itself warm, and we will not be able to relax, and as a result, we will not get enough sleep. nine0003

© Depositphotos

If you can't sleep, experts advise taking a warm shower and wearing soft socks at night, this will also help you relax and keep your feet warm if they are constantly cold.

© Depositphotos

An integral part of the routine

From childhood, our parents covered us with a blanket before going to bed. Covering up before going to bed is one of the daily habits that signals that it's time to sleep. Even if it seems to you that you won’t be able to sleep, just wrap yourself properly in a blanket. nine0003

Even if it seems to you that you won’t be able to sleep, just wrap yourself properly in a blanket. nine0003

© Depositphotos

Reduces anxiety

One of the chemicals that make us feel good is serotonin. He is responsible for making a person feel calm and happy. In a state of stress, insomnia often torments. Covering ourselves with a blanket, we calm down and fall asleep.

© Depositphotos

This happens because the blanket exerts gentle pressure on the body, as if hugging us, and serotonin is released in the body. At the same time, experts note that too heavy a blanket can cause irritation and interfere with healthy sleep. nine0003

© Depositphotos

Increases feelings of security

The most common childhood fear is the fear of the dark. Then we hid under the covers from invisible monsters and felt safe. The blanket became a shelter that helped us sleep.