Temper dysregulation disorder symptoms

NIMH » Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder: The Basics

What is disruptive mood dysregulation disorder?

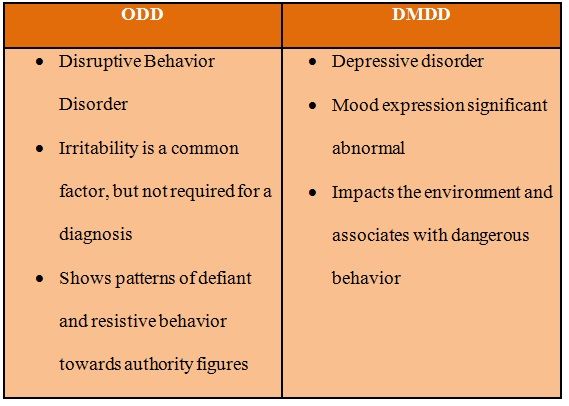

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) is a condition in which children or adolescents experience ongoing irritability, anger, and frequent, intense temper outbursts. The symptoms of DMDD go beyond a “bad mood.” DMDD symptoms are severe. Youth who have DMDD experience significant problems at home, at school, and often with peers. They also tend to have high rates of health care service use, hospitalization, and school suspension, and they are more likely to develop other mood disorders.

DMDD can be treated. If you are concerned that your child may have DMDD, talk to your child’s pediatrician or health care provider.

Did You Know?

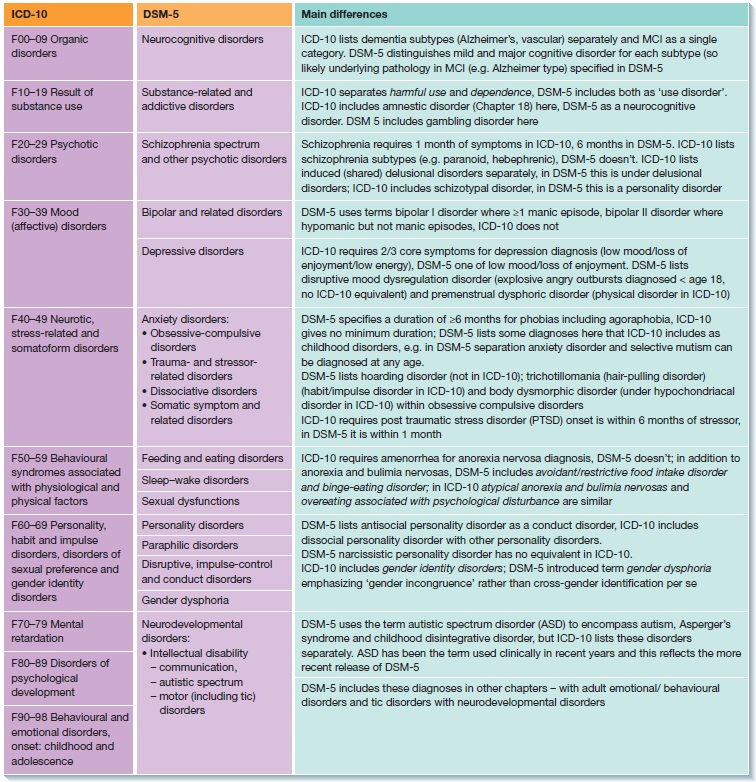

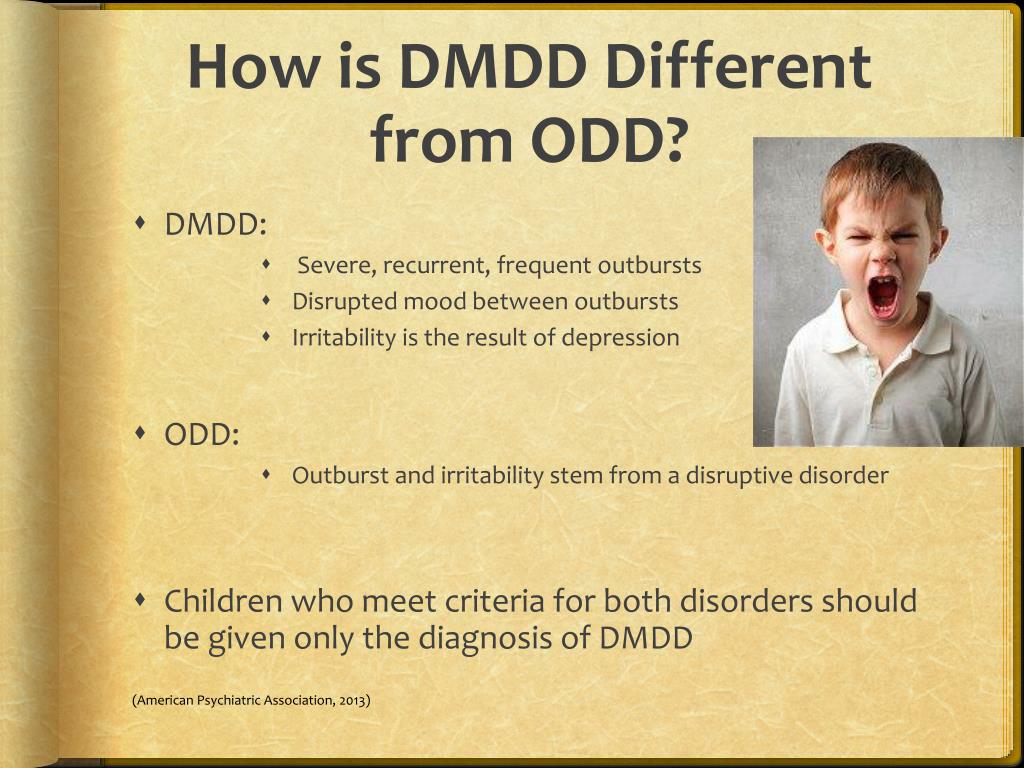

DMDD is a newly classified disorder, first appearing in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) in 2013. The DSM is used for the assessment and diagnosis of mental disorders; it does not include specific guidelines for the treatment of any disorder.

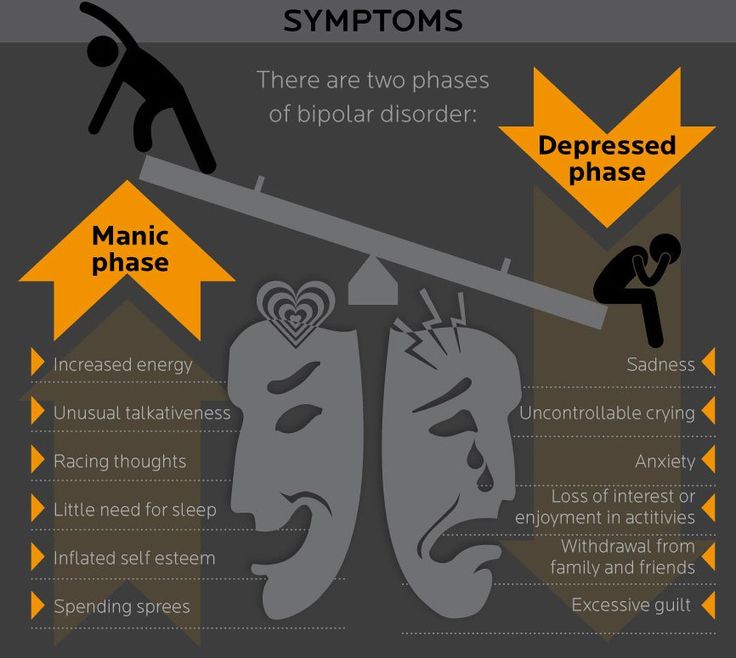

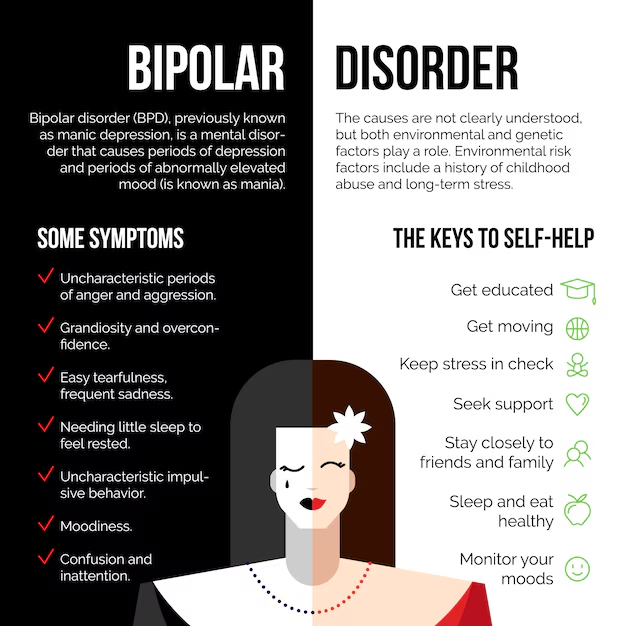

Researchers at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) developed the DMDD diagnosis to diagnose more accurately youth who may have been previously diagnosed with pediatric bipolar disorder (despite not experiencing the symptoms needed for a diagnosis of bipolar disorder).

For more information on this research, visit the NIMH website and search for “DMDD.”

What are the signs and symptoms of DMDD?

Children or adolescents with DMDD experience:

- Severe temper outbursts (verbal or behavioral), on average, three or more times per week

- Outbursts and tantrums that have been ongoing for at least 12 months

- Chronically irritable or angry mood most of the day, nearly every day

- Trouble functioning due to irritability in more than one place (at home, at school, and with peers)

Youth with DMDD are diagnosed between the ages of 6 and 10. To be diagnosed with DMDD, a child must have experienced symptoms steadily for 12 or more months.

All children can become irritable sometimes. It’s a normal reaction to frustration. Children experiencing severe irritability (as observed in DMDD) have difficulty tolerating frustration and have outbursts that are out of proportion for the situation at hand. These outbursts occur more often and are more severe than what you would typically expect for children of this age.

For example, a parent tells the child to stop playing a game and do their homework. Any child might be frustrated or annoyed. But a child with DMDD may become extremely upset and emotional and have an intense temper outburst with yelling or hitting. A child with DMDD experiences these intense temper outbursts a few times a week.

Over time, as children grow and develop, the symptoms of DMDD may change. For example, an adolescent or young adult with DMDD may experience fewer tantrums, but they begin to exhibit symptoms of depression or anxiety. For these reasons, treatment may change over time, too.

For these reasons, treatment may change over time, too.

Children with DMDD may have trouble in school and experience difficulty maintaining healthy relationships with family or peers. They also may have a hard time in social settings or participating in activities such as team sports. If you think your child has DMDD, it is essential to seek a diagnosis and treatment.

How is DMDD diagnosed?

If you think your child may be experiencing symptoms of DMDD, talk to your child’s health care provider. Describe your child’s behavior, and report what you have observed and learned from talking with others, such as a teacher or school counselor. An evaluation by your child’s health care provider can help clarify problems that may be underlying your child’s behavior, and the provider may recommend the next steps.

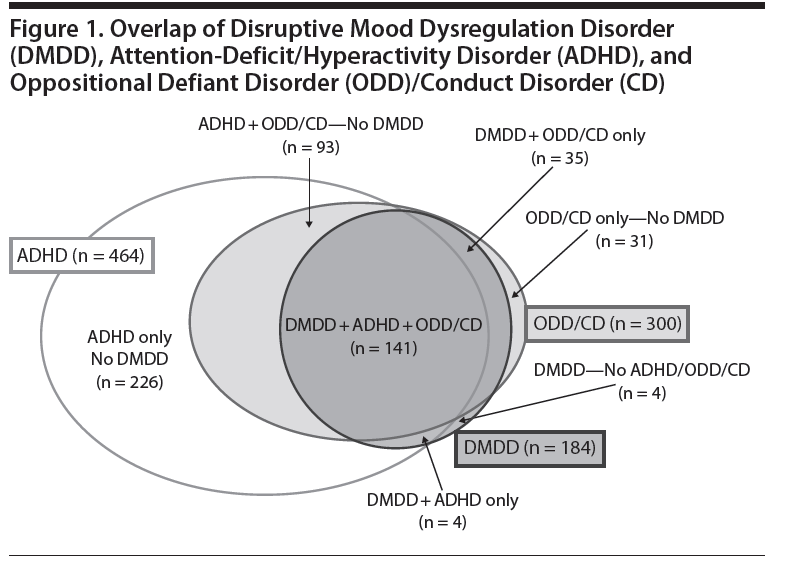

You also can ask your health care provider for a referral to a mental health professional who has experience working with children and adolescents. DMDD symptoms also can occur at the same time as other disorders associated with irritability, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or anxiety disorders. An accurate diagnosis is vital for effective treatment.

DMDD symptoms also can occur at the same time as other disorders associated with irritability, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or anxiety disorders. An accurate diagnosis is vital for effective treatment.

For more information about diagnosis and treatment of children and tips for talking to your health care provider, check out NIMH’s fact sheets, Children and Mental Health and Tips for Talking With Your Health Care Provider. If you need help identifying a provider in your area, call the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Treatment Referral Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357). SAMHSA also has a Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator that can be searched by location.

How is DMDD treated?

DMDD is a newly classified disorder, and few DMDD-specific treatment studies have been conducted to date. Current treatments are primarily based on research focused on other childhood disorders associated with irritability (such as anxiety and ADHD). Fortunately, many of these treatments also work for DMDD. NIMH is currently funding studies focused on further improving these treatments and identifying new treatments specifically for DMDD. It is important for parents or caregivers to work closely with their child’s doctor to make treatment decisions that are best for their child.

Fortunately, many of these treatments also work for DMDD. NIMH is currently funding studies focused on further improving these treatments and identifying new treatments specifically for DMDD. It is important for parents or caregivers to work closely with their child’s doctor to make treatment decisions that are best for their child.

Treatment for DMDD generally includes certain types of psychotherapy (“talk therapy”) and sometimes medications. In many cases, psychotherapy is considered first, with medication added later. However, at times, providers recommend that children receive both psychotherapy and medication at the start of their treatment.

Psychotherapies

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is used to help children and adolescents learn how to cope with thoughts and feelings that contribute to their feeling depressed or anxious. CBT for anxiety often includes exposing the child to situations that make them anxious so that they can learn to respond to those situations better. Clinicians can use similar techniques to teach children to increase their ability to tolerate frustration without having an outburst. This therapy also teaches coping skills for controlling anger and ways to identify and re-label the distorted perceptions that contribute to outbursts.

Clinicians can use similar techniques to teach children to increase their ability to tolerate frustration without having an outburst. This therapy also teaches coping skills for controlling anger and ways to identify and re-label the distorted perceptions that contribute to outbursts.

Researchers also are studying the use of dialectical behavior therapy for children (DBT-C) with DMDD. This type of therapy may help children learn to regulate their emotions and avoid extreme or prolonged outbursts. In DBT-C, the clinician helps children learn skills that can help with regulating their moods and emotions.

It can be effective to combine therapy for the child or adolescent with parent training. Parent training teaches parents or caregivers more effective ways to respond to irritable behavior, such as anticipating events that might lead a child to have a temper outburst and working ahead to avert it. Training also focuses on the importance of predictability, being consistent with children, and rewarding positive behavior.

Computer-based training

New approaches currently are being tested to leverage mobile and computer-based platforms to help address certain DMDD symptoms in children. However, this research is in the early stages. After studies are complete, findings from this line of research may be disseminated on NIMH’s News and Events webpage.

Medications

Currently, there are no medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for treating children or adolescents with DMDD. However, health care providers may prescribe certain medications—such as stimulants, antidepressants, and atypical antipsychotics—to help relieve your child’s DMDD symptoms. All medications have side effects. Monitor and report your child’s side effects and review the medications frequently with your child’s health care provider. Visit the FDA website for the most up-to-date information on medications, side effects, and warnings.

- Stimulants are often used in the treatment of ADHD, and research suggests that stimulant medications also may decrease irritability in youth.

- Antidepressants are sometimes used to treat irritability and mood problems that children with DMDD may experience. One study suggests that citalopram (a serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant), when combined with the stimulant methylphenidate, can decrease irritability in youth with DMDD. Please note: Antidepressants may increase suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth, who should be monitored closely by their health care provider.

- Certain atypical antipsychotic medications are used to treat children with irritability, severe outbursts, or aggression. FDA has approved these medications for the treatment of irritability associated with autism, and they are sometimes used to treat DMDD, too. However, due to the side effects associated with these medications, they are often used only when other approaches have not been successful.

Tips for Parents and Caregivers

Being a parent or caregiver for a child or adolescent with DMDD can be stressful and overwhelming. While working on creating a better environment for the child, you may want to consider the following:

While working on creating a better environment for the child, you may want to consider the following:

Learn as much as you can about the disorder. Talk to your child’s health care provider or mental health professional. Ask questions about risks, benefits, and treatment options. You can find additional information (including the latest news, videos, and information about clinical trials) on NIMH's health topic page about DMDD.

Talk to your child’s teacher, counselor, or school psychologist. Together, you may come up with strategies, plans, and accommodations that can help your child thrive in school. For more information, check out NIMH’s Children and Mental Health fact sheet.

Find ways to manage your stress. Take practical steps to manage your own stress to avoid the risk of negative health effects. For tips, see NIMH’s 5 Things You Should Know About Stress.

Seek additional support and professional help. Parents and caregivers may be able to find resources and encouragement through their local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the National Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health, Mental Health America, and other organizations. (Please Note: These resources are provided for informational purposes only. They are not comprehensive and do not constitute an endorsement by NIMH.)

Parents and caregivers may be able to find resources and encouragement through their local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the National Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health, Mental Health America, and other organizations. (Please Note: These resources are provided for informational purposes only. They are not comprehensive and do not constitute an endorsement by NIMH.)

Communicate regularly and effectively with your child’s health care provider. Find tips to help you prepare for your child’s visit. For additional resources, including questions to ask your doctor, visit the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website.

Are there clinical trials studying DMDD?

NIMH supports a wide range of research, including clinical trials that look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions—including DMDD. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge so that others may be better helped in the future.

Children are not little adults, yet they are often given medicines and treatments that have been tested only in adults. There’s a lot of evidence that children’s developing brains and bodies can respond to medicines and treatments differently than adults’ brains and bodies respond. The way to get the best treatments for children is through research designed specifically for them. To find studies being conducted at NIMH for children and adolescents, visit Pediatric Studies on NIMH’s Join a Study webpage. To find a clinical trial near you, visit ClinicalTrials.gov.

Reprints

This publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission from NIMH. Citation of NIMH as a source is appreciated. To learn more about using NIMH publications, refer to our reprint guidelines.

For More Information

MedlinePlus (National Library of Medicine) (En español)

ClinicalTrials. gov (En español)

gov (En español)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

National Institutes of Health

NIH Publication No. 20-MH-8119

NIMH » Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder

Overview

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) is a childhood condition of extreme irritability, anger, and frequent, intense temper outbursts. DMDD symptoms go beyond a being a “moody” child—children with DMDD experience severe impairment that requires clinical attention. DMDD is a fairly new diagnosis, appearing for the first time in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published in 2013.

Read transcript.

Signs and Symptoms

DMDD symptoms typically begin before the age of 10, but the diagnosis is not given to children under 6 or adolescents over 18. A child with DMDD experiences:

- Irritable or angry mood most of the day, nearly every day

- Severe temper outbursts (verbal or behavioral) at an average of three or more times per week that are out of keeping with the situation and the child’s developmental level

- Trouble functioning due to irritability in more than one place (e.

g., home, school, with peers)

g., home, school, with peers)

To be diagnosed with DMDD, a child must have these symptoms steadily for 12 or more months.

Risk Factors

It is not clear how widespread DMDD is in the general population, but it is common among children who visit pediatric mental health clinics. Researchers are exploring risk factors and brain mechanisms of this disorder.

Treatment and Therapies

DMDD is a new diagnosis. Therefore, treatment is often based on what has been helpful for other disorders that share the symptoms of irritability and temper tantrums. These disorders include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety disorders, oppositional defiant disorder, and major depressive disorder.

If you think your child has DMDD, it is important to seek treatment. DMDD can impair a child’s quality of life and school performance and disrupt relationships with his or her family and peers. Children with DMDD may find it hard to participate in activities or make friends. Having DMDD also increases the risk of developing depression or anxiety disorders in adulthood.

Having DMDD also increases the risk of developing depression or anxiety disorders in adulthood.

While researchers are still determining which treatments work best, two major types of treatment are currently used to treat DMDD symptoms:

- Medication

- Psychological treatments

- Psychotherapy

- Parent training

- Computer based training

Psychological treatments should be considered first, with medication added later if necessary, or psychological treatments can be provided along with medication from the beginning.

It is important for parents or caregivers to work closely with the doctor to make a treatment decision that is best for their child.

Medication

Many medications used to treat children and adolescents with mental illness are effective in relieving symptoms. However, some of these medications have not been studied in depth and/or do not have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use with children or adolescents. All medications have side effects and the need for continuing them should be reviewed frequently with your child’s doctor.

All medications have side effects and the need for continuing them should be reviewed frequently with your child’s doctor.

For basic information about these and other mental health medications, you can visit the NIMH Mental Health Medications webpage. For the most up-to-date information on medications, side effects, and warnings, visit the FDA website.

Stimulants

Stimulants are medications that are commonly used to treat ADHD. There is evidence that, in children with irritability and ADHD, stimulant medications also decrease irritability.

Stimulants should not be used in individuals with serious heart problems. According to the FDA, people on stimulant medications should be periodically monitored for change in heart rate and blood pressure.

Antidepressants

Antidepressant medication is sometimes used to treat the irritability and mood problems associated with DMDD. Ongoing studies are testing whether these medicines are effective for this problem. It is important to note that, although antidepressants are safe and effective for many people, they carry a risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in children and teens. A “black box” warning—the most serious type of warning that a prescription can carry—has been added to the labels of these medications to alert parents and patients to this risk. For this reason, a child taking an antidepressant should be monitored closely, especially when they first start taking the medication.

It is important to note that, although antidepressants are safe and effective for many people, they carry a risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in children and teens. A “black box” warning—the most serious type of warning that a prescription can carry—has been added to the labels of these medications to alert parents and patients to this risk. For this reason, a child taking an antidepressant should be monitored closely, especially when they first start taking the medication.

Atypical Antipsychotic

An atypical antipsychotic medication may be prescribed for children with very severe temper outbursts that involve physical aggression toward people or property. Risperidone and aripiprazole are FDA-approved for the treatment of irritability associated with autism and are sometimes used to treat DMDD. Atypical antipsychotic medications are associated with many significant side-effects, including suicidal ideation/behaviors, weight gain, metabolic abnormalities, sedation, movement disorders, hormone changes, and others.

Psychological treatments

Psychotherapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy, a type of psychotherapy, is commonly used to teach children and teens how to deal with thoughts and feelings that contribute to their feeling depressed or anxious. Clinicians can use similar techniques to teach children to more effectively regulate their mood and to increase their tolerance for frustration. The therapy also teaches coping skills for regulating anger and ways to identify and re-label the distorted perceptions that contribute to outbursts. Other research psychotherapies are being explored at the NIMH.

Parent Training

Parent training aims to help parents interact with a child in a way that will reduce aggression and irritable behavior and improve the parent-child relationship. Multiple studies show that such interventions can be effective. Specifically, parent training teaches parents more effective ways to respond to irritable behavior, such as anticipating events that might lead a child to have a temper outburst and working ahead to avert the outburst. Training also focuses on the importance of predictability, being consistent with children, and rewarding positive behavior.

Training also focuses on the importance of predictability, being consistent with children, and rewarding positive behavior.

Computer-based training

Evidence suggests that irritable youth with DMDD may be prone to misperceiving ambiguous facial expressions as angry. There is preliminary evidence that computer-based training designed to correct this problem may help youth with DMDD or severe irritability.

Join a Study

Clinical trials are research studies that look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions. The goal of clinical trials is to determine if a new test or treatment works and is safe. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge so that others may be better helped in the future.

Researchers at NIMH and around the country conduct many studies with patients and healthy volunteers. We have new and better treatment options today because of what clinical trials uncovered years ago.:strip_icc():format(jpeg)/kly-media-production/medias/3018655/original/008121600_1578662842-Infografis_Penderita_Skizofrenia_Meningkat_di_Indonesia.jpg) Be part of tomorrow’s medical breakthroughs. Talk to your health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you.

Be part of tomorrow’s medical breakthroughs. Talk to your health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you.

To learn more or find a study, visit:

- NIMH’s Clinical Trials webpage: Information about participating in clinical trials

- Clinicaltrials.gov: Current Studies on DMDD: List of clinical trials funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) being conducted across the country

- Join a Study: Children – DMDD: List of studies being conducted on the NIH Campus in Bethesda, MD

Learn More

Free Fact Sheets

- Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder: The Basics: This factsheet provides information about disruptive mood dysregulation disorder including a description of the condition, signs and symptoms, how it is diagnosed, treatment options, and tips for parents and caregivers.

Multimedia

- Watch: Severe Irritability in Youth: Dr.

Melissa Brotman, Assistant Clinical Investigator in the NIMH Emotion and Development Branch, discusses NIMH research on irritability in children.

Melissa Brotman, Assistant Clinical Investigator in the NIMH Emotion and Development Branch, discusses NIMH research on irritability in children. - Watch: Depression in Adolescents: Mechanisms and Treatment of a Global Health Concern and Mechanism-based Treatments for Irritability in Youth: Dr. Melissa Brotman, Assistant Clinical Investigator in the NIMH Emotion and Development Branch, describes NIMH research on treatments for DMDD. Her presentation starts at approximately minute 30 of the video.

- Watch: Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder: Dr. Ellen Leibenluft, Senior Investigator and Chief of the NIMH Emotion and Development Branch, explains the history of Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder.

- Watch: Irritability in Children - Dr. Ellen Leibenluft: Dr. Ellen Leibenluft, Senior Investigator and Chief of the NIMH Emotion and Development Branch, discusses research on irritability in children.

- Webinar: Severe Irritability and DMDD in Youth -- Dr.

Kenneth Towbin: NIMH child and adolescent psychiatrist Dr. Kenneth Towbin discusses NIMH research into childhood severe irritability and disruptive mood dysregulation.

Kenneth Towbin: NIMH child and adolescent psychiatrist Dr. Kenneth Towbin discusses NIMH research into childhood severe irritability and disruptive mood dysregulation.

Research and Statistics

- Journal Articles: References and abstracts from MEDLINE/PubMed (National Library of Medicine)

Last Reviewed: December 2019

Unless otherwise specified, NIMH information and publications are in the public domain and available for use free of charge. Citation of NIMH is appreciated. Please see our Citing NIMH Information and Publications page for more information.

Early childhood temperament and development of anxiety and depression

Nathan A. Fox, PhD, Tahl I. Frenkel, MA

University of Maryland, USA

(English). Translation: June 2015

Translation: June 2015

Introduction

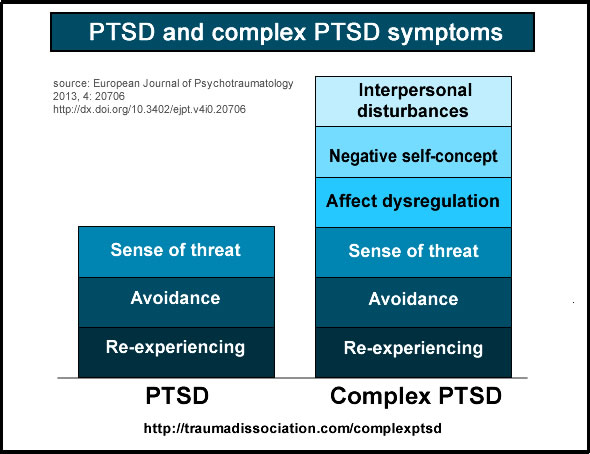

Anxiety disorders in general, and social anxiety disorder (SAD) in particular, cause severe distress and increase the risk of long-term adverse effects. Most anxiety disorders in adults begin in childhood or adolescence at an extremely steady rate of 5 to 10 percent; and the level of social phobia varies from 1.6% to 8.5%. 2-4 Longitudinal studies show that the temperamental trait of behavioral inhibition appears to be the most likely predictor of anxiety risk later on. 5-6

The purpose of this chapter is to explore in general terms the relationship between this temperament and the occurrence of anxiety disorders. We will review research on two cognitive processes, attention and executive processes, that contribute to anxiety disorders among children with behavioral inhibition. Finally, in line with recent evidence that behavioral inhibition may represent not only a specific temperamental predisposition to anxiety, but also a more general risk factor for internalizing disorders, 7 we will review the existing (still limited) literature linking early temperament with the subsequent development of depression.

Item

Behavioral inhibition is a type of temperament that can be identified in infancy and early childhood. Infants with this temperament show increased irritability and motor reactivity to unusual stimuli. During their early preschool years, they avoid social contact and tend to withdraw in unfamiliar social situations, which makes them less self-confident5,6 and more susceptible to peer rejection, 8.9 what is the reason for negative self-perception. 10 In general, inhibited children have fewer friends, 11 they are more likely to show increased anxiety and feel lonely. 12

Anxiety risk studies focus on early temperamental traits, especially behavioral inhibition. 10,13,14 For example, Schwartz et al6 found that 61% of thirteen-year-olds who were noted to show signs of behavioral inhibition at age two showed clear signs of anxiety during social interaction, compared with only 27% of those who showed no inhibition. Similarly, Chronis-Tuscano et al. 15 found a fourfold increased likelihood of a lifetime diagnosis of social anxiety disorder among adolescents with consistently high levels of behavioral inhibition between the ages of 1 and 7 years. Data from both studies suggest that early temperament limits but does not predetermine outcomes. Only about half of inhibited children are at significant risk, and anxiety tends to wax and wane over time. 16

Similarly, Chronis-Tuscano et al. 15 found a fourfold increased likelihood of a lifetime diagnosis of social anxiety disorder among adolescents with consistently high levels of behavioral inhibition between the ages of 1 and 7 years. Data from both studies suggest that early temperament limits but does not predetermine outcomes. Only about half of inhibited children are at significant risk, and anxiety tends to wax and wane over time. 16

We argue that temperament in childhood shapes how a person perceives their environment, which reciprocally affects social interaction and possible social outcomes and mental health outcomes. 17 This dynamic is particularly evident in early adolescence, during which the emergence of a peer group with more significant developmental influence coincides with a dramatic increase in psychopathology,16 in particular social phobia. 6,15,18 Temperament also shapes vital cognitive processes such as attention and certain executive processes that underpin how children perceive and respond to social stimuli in the environment.

Issues

Questions concerning the functional and structural relationship between temperament and anxiety remain open. 19 Several reviews 10,17,20,21 noted a variety of behavioral and physiological similarities and differences between temperamentally retarded and anxious individuals. If anxiety and inhibited temperament are seen as two distinct constructs, then temperament either exposes the child to the risk of developing anxiety or influences the persistence or severity of anxiety disorders once they occur. 10 On the other hand, these terms may simply refer to different aspects of the same construct, and the differences between them are then forced by opinions in the field. 21

Scientific context

The scientific literature suggests that deviations in both "upward" a attentional mechanisms and "downward" a executive control processes may play a key role in the etiology and maintenance of anxiety. 22 These disturbances extend to both emotionally charged and emotionally neutral stimuli, reflecting a prioritization of certain categories of stimuli (i.e. erroneous attitudes towards stimuli) along with increased alertness to one's own activity and behavior (i.e. cognitive monitoring) .

22 These disturbances extend to both emotionally charged and emotionally neutral stimuli, reflecting a prioritization of certain categories of stimuli (i.e. erroneous attitudes towards stimuli) along with increased alertness to one's own activity and behavior (i.e. cognitive monitoring) .

Anxious children 23-25 and adults 26-27 show attention bias towards threatening stimuli. Previous work has shown 28.29 that adolescents with clinically severe anxiety showed disturbances in the reaction of the amygdala b and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex c (vlPFC) to threat when performing tasks for attention distortions. Attention distortions, as such, are automatic "bottom-up" mechanisms that shape cognition and behavior. The study also implies a neural network in the prefrontal cortex that engages attention to closely follow the activity, taking into account the feedback as the person then applies more specialized executive control mechanisms to correct subsequent behavior. 30-32 Anxiety-related disturbances of this pattern are evident in both children, 33 and adults. 34 Imaging studies have implicated the anterior cingulate cortex d (ACC) in this process, as it is hyperactive in anxious individuals during tasks that require cognitive control or "top-down" control. 35

30-32 Anxiety-related disturbances of this pattern are evident in both children, 33 and adults. 34 Imaging studies have implicated the anterior cingulate cortex d (ACC) in this process, as it is hyperactive in anxious individuals during tasks that require cognitive control or "top-down" control. 35

Key Questions

Among typically developing children, approximately 15-20% of Caucasian children in the United States exhibit a behaviorally inhibited temperament in early childhood. Longitudinal studies have shown that about half of these behaviorally retarded children go on to develop anxiety disorders into adolescence and adulthood. A key research question in terms of early intervention is to identify the factors that lead to these different trajectories over time. That is, what factors (either in surrounding adults or in the child himself) protect against anxiety or increase the risk of developing it.

Recent research findings

Attention distortions in relation to threat

Recent research suggests that behavioral retardation is characterized by impaired control of attention. 36.37 Two recent longitudinal studies 18.38 examined the relationship between behavioral inhibition in childhood, distortions in attention to threatening stimuli, and propensity to withdraw from social contacts. Pérez-Edgar et al 18 found that adolescents who were behaviorally retarded as children exhibited a distortion of attention towards a potential threat. In addition, threat attention bias mediated a statistical association between behavioral inhibition in childhood and propensity to withdraw from social contact during adolescence. In a separate study, Pérez-Edgar et al. 38 found that behavioral inhibition at the age of walking was predictive of high social avoidance in early childhood. Again, this relationship was statistically mediated by threat attention bias such that the relationship between behavioral inhibition and social avoidance was only noticeable in children who showed threat attention bias. These data provide support for a view that threat attention distortions are an important mediator of behavioral inhibition and the subsequent occurrence of clinical anxiety.

These data provide support for a view that threat attention distortions are an important mediator of behavioral inhibition and the subsequent occurrence of clinical anxiety.

Executive processes: inhibitory control and cognitive monitoring

Inhibitory control characterizes the ability to restrain and suppress dominant responses and behaviors in favor of more appropriate or subdominant responses and behaviors39. Cognitive monitoring represents the ability to pay attention to one's own activities, notice errors, and correct behavior based on feedback. It is believed that these control processes play a role in the regulation of negative emotions and in such a property of temperament as reactivity. 40-42

Several studies have shown that inhibitory control mediates the ability to predict anxiety behaviors based on measurements of temperamental manifestations of behavioral inhibition. Children with a high level of inhibitory control were found to be more socially anxious, 43 less socially competent and more socially withdrawn, 44 than behaviorally inhibited children with a low level of inhibitory control. Similarly, White et al. 45 found that a high level of inhibitory control increased the risk of anxiety disorders among highly behaviorally inhibited children.

Similarly, White et al. 45 found that a high level of inhibitory control increased the risk of anxiety disorders among highly behaviorally inhibited children.

In independent studies, increased cognitive monitoring has been found to be associated with increased anxiety in both adults, 46,47 and children. 48 McDermott et al49 found that cognitive monitoring was higher in adolescents with severe childhood behavioral retardation compared with adolescents with low levels of behavioral retardation. Moreover, increased monitoring mediated early behavioral inhibition and later anxiety disorders. 49 Thus, like the distortions of attention to threatening stimuli, the executive processes of inhibitory control and cognitive monitoring mediate a child's temperament prone to an increased risk of anxiety.

Unexplored areas

Age changes result from the interaction between the child's innate characteristics and environmental context, making the child both creator and product of the environment. 50 Behavioral inhibition may prompt the child to go in one of a number of directions, and the expected outcome may be the result of multiple provocative paths. 10 Research thus needs to explain the operation of a number of mediating factors that may come into play at various points during development. So far, there are very few studies analyzing the discontinuous nature of behavioral retardation and possible confounding protective factors that may contribute to the discontinuity of the behavioral retardation trajectory and further prevention of psychopathology. The discontinuity of these behaviors provides a good opportunity to identify factors that could potentially be used in prevention efforts.

50 Behavioral inhibition may prompt the child to go in one of a number of directions, and the expected outcome may be the result of multiple provocative paths. 10 Research thus needs to explain the operation of a number of mediating factors that may come into play at various points during development. So far, there are very few studies analyzing the discontinuous nature of behavioral retardation and possible confounding protective factors that may contribute to the discontinuity of the behavioral retardation trajectory and further prevention of psychopathology. The discontinuity of these behaviors provides a good opportunity to identify factors that could potentially be used in prevention efforts.

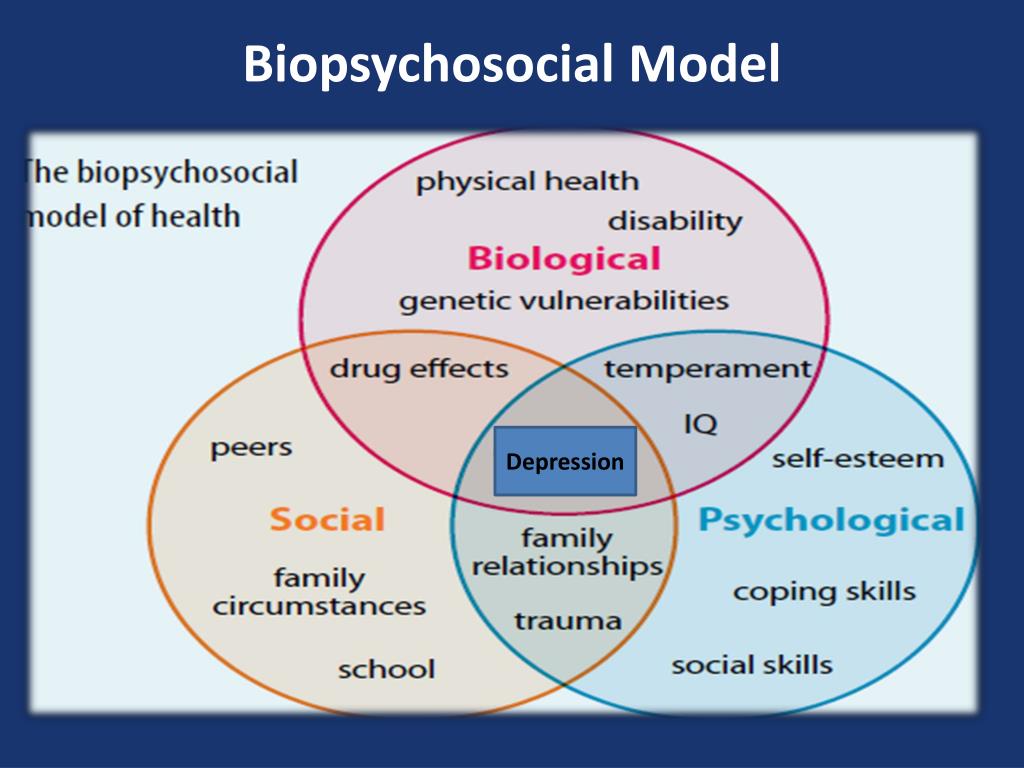

In addition, the relationship between behavioral retardation and depression is much less understood. Given the relationship between behavioral retardation and depression, it is important to note that people with anxiety disorders have an increased risk of developing depression compared to non-anxious people, 51 and data show that in many cases, the presence of an anxiety disorder precedes the development of depression. deep depression. 52 Given this temporal relationship between anxiety and depression, it is important to understand that the relationship between behavioral inhibition and depression can be highly dependent on the presence of anxiety. One study is known to have found that social anxiety was a necessary intermediate between behavioral retardation and depression. 53 Similarly, other studies 54 that have found relationships between behavioral retardation, anxiety, and depression have used structural equation modeling, which showed that the pathway by which behavioral retardation leads to anxiety, which in turn leads to depression, provided the most accurate match to the data.

deep depression. 52 Given this temporal relationship between anxiety and depression, it is important to understand that the relationship between behavioral inhibition and depression can be highly dependent on the presence of anxiety. One study is known to have found that social anxiety was a necessary intermediate between behavioral retardation and depression. 53 Similarly, other studies 54 that have found relationships between behavioral retardation, anxiety, and depression have used structural equation modeling, which showed that the pathway by which behavioral retardation leads to anxiety, which in turn leads to depression, provided the most accurate match to the data.

The specificity of the social and non-social components of childhood behavioral retardation and their relationship to symptoms of anhedonic depression, social anxiety, and agitation in young adults has now been studied by self-reporting in additional studies. The results were compared with studies showing that non-social behavioral retardation (“fearfulness”), but not social behavioral retardation, increased the risk of future depression; 55 and with other studies showing that depressive symptoms were more strongly associated with childhood social than with non-social behavioral disorder. 56

56

Interestingly, Sportel 57 et al. investigated the direct (additive) and indirect (interactive) effects of behavioral inhibition and attention control on different dimensions of internalization in a sample of normal adolescents. The results showed a stronger association of behavioral retardation, compared with attention control, with symptoms of anxiety, and a stronger association of attention control, compared with behavioral retardation, with symptoms of depression. Moreover, while behavioral retardation was associated with both anxiety and depression, attentional control mediated this relationship, thus reducing the impact of severe behavioral retardation on both dimensions of internalization.

Finally, in considering temperament as a vulnerability factor for depression, it is important to note that, in addition to behavioral inhibition, some theorists have developed temperament models that associate additional temperament styles, namely Positive Emotion (PE) and Negative Emotion (NE), with depression. 58 Many cross-sectional studies have provided evidence that youth and adults diagnosed with depressive symptoms exhibit reduced levels of PE and increased levels of NE, 59,60,61 and their combination was associated with coinciding depressive symptoms in samples of clinical groups 62,63 and groups of people examined en masse at the place of residence. 61,64,65 Moreover, longitudinal studies have shown that lower levels of PE 60,66,67 and higher levels of NE in childhood 68-70 predict the development of depressive symptoms and disorders. For example, low levels of PE in preschoolers predicted high levels of depressogenic-type cognitive style at age 7 and depressive symptoms at age 10. 71.72

58 Many cross-sectional studies have provided evidence that youth and adults diagnosed with depressive symptoms exhibit reduced levels of PE and increased levels of NE, 59,60,61 and their combination was associated with coinciding depressive symptoms in samples of clinical groups 62,63 and groups of people examined en masse at the place of residence. 61,64,65 Moreover, longitudinal studies have shown that lower levels of PE 60,66,67 and higher levels of NE in childhood 68-70 predict the development of depressive symptoms and disorders. For example, low levels of PE in preschoolers predicted high levels of depressogenic-type cognitive style at age 7 and depressive symptoms at age 10. 71.72

Conclusions

Behavioral inhibition is a risk factor for the development of internalizing disorders, although research suggests that not all children with this temperament develop the disorder. Current research is focused on describing the complex interplay of temperament with potential mediating factors that can alter temperament trajectories. Studies focusing on endogenous factors suggest that both attention and executive processes are important regulators of the development of behavioral inhibition towards anxiety or psychological resistance to such disorders. Although it is not mentioned in this review, there is a large body of work on the role of exogenous factors in regulating the temperament of behavioral inhibition. 16.73

Current research is focused on describing the complex interplay of temperament with potential mediating factors that can alter temperament trajectories. Studies focusing on endogenous factors suggest that both attention and executive processes are important regulators of the development of behavioral inhibition towards anxiety or psychological resistance to such disorders. Although it is not mentioned in this review, there is a large body of work on the role of exogenous factors in regulating the temperament of behavioral inhibition. 16.73

Recommendations for parents, services and policy

Identifying young children who are at risk of developing anxiety disorders and implementing preventive (prophylactic) interventions to reduce risk are important findings in behavioral inhibition research. Due to the obedient and "comfortable" nature of behaviorally retarded children, teachers and parents may not always recognize such children in early childhood and primary school. Since only a few children with inhibited behavior develop anxiety disorders later on, it is important to identify both endogenous and exogenous factors that mediate the relationship of temperament and psychopathology. Preliminary research contributes to an optimistic view of prevention strategies and easily accessible educational programs for parents and caregivers of adult behaviorally inhibited preschoolers. 74 These programs aim to teach adults about the nature of temperament and withdrawal and how to apply techniques by which they can help behaviorally retarded children develop the ability to manage reactions to new situations, thus promoting the development of social skills and reducing inhibited and anxious behavior over time. Finally, innovative approaches that include training in attention and executive processes can significantly reduce anxiety-induced withdrawal in temperamentally at-risk individuals.

Since only a few children with inhibited behavior develop anxiety disorders later on, it is important to identify both endogenous and exogenous factors that mediate the relationship of temperament and psychopathology. Preliminary research contributes to an optimistic view of prevention strategies and easily accessible educational programs for parents and caregivers of adult behaviorally inhibited preschoolers. 74 These programs aim to teach adults about the nature of temperament and withdrawal and how to apply techniques by which they can help behaviorally retarded children develop the ability to manage reactions to new situations, thus promoting the development of social skills and reducing inhibited and anxious behavior over time. Finally, innovative approaches that include training in attention and executive processes can significantly reduce anxiety-induced withdrawal in temperamentally at-risk individuals.

Literature

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y.

The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry . Jan 1998;55(1):56-64.

The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry . Jan 1998;55(1):56-64. - Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Frequency and comorbidity of social phobia and social fears in adolescents. Behavior Research and Therapy . Sep 1999;37(9):831-843.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Prevalence and comorbidity of DSM-III-R diagnoses in a birth cohort of 15 year olds. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Nov 1993;32(6):1127-1134.

- McGee R, Feehan M, Williams S, Partridge F, Silva PA, Kelly J. DSM-III disorders in a large sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Jul 1990;29(4):611-619.

- Hayward C, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB. Linking self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition to adolescent social phobia. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry .

Dec 1998;37(12):1308-1316.

Dec 1998;37(12):1308-1316. - Schwartz CE, Snidman N, Kagan J. Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Aug 1999;38(8):1008-1015.

- Schofield CA, Coles ME, Gibb BE. Retrospective reports of behavioral inhibition and young adults' current symptoms of social anxiety, depression, and anxious arousal. Journal of Anxiety Disorders . Oct 2009;23(7):884-890.

- Kagan J. Temperamental contributions to affective and behavioral profiles in childhood. In: Hoffman S.G., Dibartolo, P.M., ed. From social anxiety to social phobia: Multiple perspectives. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001:216-234.

- Prior M, Smart D, Sanson A, Oberklaid F. Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Apr 2000;39(4):461-468.

- Perez-Edgar K, Fox NA. Temperament and anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America . Oct 2005;14(4):681-706, viii.

- Garcia C, Kagan J, Resnick JS. Behavioral inhibition in young children. Child Development. 1984;55(3):1005-1019.

- Wichmann C, Coplan R, Daniels T. The social cognitions of socially withdrawn children. Social Development . 2004(13):377-392.

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, et al. Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of Psychiatry . Oct 2001;158(10):1673-1679.

- Hirshfeld DR, Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, et al. Stable behavioral inhibition and its association with anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Jan 1992;31(1):103-111.

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, et al. Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence.

Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Sep 2009;48(9):928-935.

Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Sep 2009;48(9):928-935. - Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, Ghera MM. Behavioral inhibition: linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology . 2005;56:235-262.

- Lonigan CJ, Vasey MW, Phillips BM, Hazen RA. Temperament, anxiety, and the processing of threat-relevant stimuli. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology . Mar 2004;33(1):8-20.

- Perez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, McDermott JM, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA. Attention biases to threat and behavioral inhibition in early childhood shape adolescent social withdrawal. Emotion . Jun 2010;10(3):349-357.

- Rapee RM, Coplan RJ. Conceptual Relations Between Anxiety Disorder and Fearful Temperament. Social Anxiety in Childhood: Bridging Developmental and Clinical Perspectives . 2010;127:17-31.

- Degnan KA, Fox NA.

Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: multiple levels of a resilience process. Developmental Psychopathology . Summer 2007;19(3):729-746.

Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: multiple levels of a resilience process. Developmental Psychopathology . Summer 2007;19(3):729-746. - Lahey BB. Commentary: role of temperament in developmental models of psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology . Mar 2004;33(1):88-93.

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van-IJzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin . Jan 2007;133(1):1-24.

- Roy AK, Vasa RA, Bruck M, et al. Attention bias towards threat in pediatric anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Oct 2008;47(10):1189-1196.

- Waters AM, Henry J, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS. Attentional bias towards angry faces in childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry . Jun 2010;41(2):158-164.

- Waters AM, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS. Attentional bias for emotional faces in children with generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Apr 2008;47(4):435-442.

- Mathews A, MacLeod C. Selective processing of threat cues in anxiety states. Behavior Research and Therapy . 1985;23(5):563-569.

- Wilson E, MacLeod C. Contrasting two accounts of anxiety-linked attentional bias: selective attention to varying levels of stimulus threat intensity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology . May 2003;112(2):212-218.

- Monk CS, Nelson EE, McClure EB, et al. Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation and attentional bias in response to angry faces in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry . Jun 2006;163(6):1091-1097.

- Monk CS, Telzer EH, Mogg K, et al. Amygdala and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation to masked angry faces in children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder.

Archives of General Psychiatry . May 2008;65(5):568-576.

Archives of General Psychiatry . May 2008;65(5):568-576. - Ridderinkhof KR, van den Wildenberg WP, Segalowitz SJ, Carter CS. Neurocognitive mechanisms of cognitive control: the role of prefrontal cortex in action selection, response inhibition, performance monitoring, and reward-based learning. Brain and Cognition . Nov 2004;56(2):129-140.

- Botvinick MM, Braver TS, Barch DM, Carter CS, Cohen JD. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review . Jul 2001;108(3):624-652.

- Eysenck MW, Derakshan N, Santos R, Calvo MG. Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory. Emotion . May 2007;7(2):336-353.

- Ladouceur CD, Dahl RE, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Ryan ND. Increased error-related negativity (ERN) in childhood disorders: ERP and source localization. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry . Oct 2006;47(10):1073-1082.

- Hajcak G, McDonald N, Simons RF. Anxiety and error-related brain activity.

Biological Psychology . Oct 2003;64(1-2):77-90.

Biological Psychology . Oct 2003;64(1-2):77-90. - Ursu S, Stenger VA, Shear MK, Jones MR, Carter CS. Overactive action monitoring in obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging. Psychological Science . Jul 2003;14(4):347-353.

- Fox NA, Hane AA, Pine DS. Plasticity for affective neurocircuitry - How the environment affects gene expression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. Feb 2007;16(1):1-5.

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Perez-Edgar K, White L. The Biology of temperament: An integrative approach. In: Nelson C, Luciana M, eds. The handbool of developmental cognitive neuroscience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2008:839-854.

- Perez-Edgar K, Reeb-Sutherland BC, McDermott JM, et al. Attention biases to threat link behavioral inhibition to social withdrawal over time in very young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology . Aug 2011;39(6):885-895.

- Rothbart MK, Ellis LK, Rueda MR, Posner MI.

Developing mechanisms of temperamental effortful control. J Pers . Dec 2003;71(6):1113-1143.

Developing mechanisms of temperamental effortful control. J Pers . Dec 2003;71(6):1113-1143. - Derryberry D, Rothbart MK. Reactive and effortful processes in the organization of temperament. Development and Psychopathology . Fall 1997;9(4):633-652.

- Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM. Temperamental basis of anxiety dosorders in children. In: Vasey MW, Dadds M, eds. The Developmental Psychopathology of anxiety . New York: Oxford University Press; ; 2001:60-91.

- Waters AM, Valvoi JS. Attentional bias for emotional faces in pediatric anxiety disorders: an investigation using the emotional Go/No Go task. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry . Jun 2009;40(2):306-316.

- Thorell L, Bohlin G, Rydell A. Two types of inhibitory control: predictive relations to social functioning. International Journal of Behavioral Development . 2004; 28:193-203.

- Fox NA, Henderson HA. Temperament, emotion, and executive function: Influences on the development of self-regulation.

Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society. San Francisco, 2000, April.

Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society. San Francisco, 2000, April. - White LK, McDermott JM, Degnan KA, Henderson HA, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and anxiety: the moderating roles of inhibitory control and attention shifting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology . Jul 2011;39(5):735-747.

- Righi S, Mecacci L, Viggiano MP. Anxiety, cognitive self-evaluation and performance: ERP correlates. Journal of Anxiety Disorders . Dec 2009;23(8):1132-1138.

- Sehlmeyer C, Konrad C, Zwitserlood P, Arolt V, Falkenstein M, Beste C. ERP indices for response inhibition are related to anxiety-related personality traits. Neuropsychologia . Jul 2010;48(9):2488-2495.

- Hum KM, Manassis K, Lewis MD. Neural mechanisms of emotion regulation in childhood anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry . In Press. 2012.

- McDermott JM, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA.

A history of childhood behavioral inhibition and enhanced response monitoring in adolescence are linked to clinical anxiety. Biological Psychiatry . Mar 1 2009;65(5):445-448.

A history of childhood behavioral inhibition and enhanced response monitoring in adolescence are linked to clinical anxiety. Biological Psychiatry . Mar 1 2009;65(5):445-448. - Lerner RM, Hess LE, Nitz KA. Developmental perspective on psychopathology. In: Herson M, Last CG, eds. Handbook of child and adult psychopathology: a longitudinal perspective . Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press; 1991:9-32.

- Stein MB, Fuetsch M, Muller N, Hofler M, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. Social anxiety disorder and the risk of depression: a prospective community study of adolescents and young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry . Mar 2001;58(3):251-256.

- Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology . Nov 2001;110(4):585-599.

- Gladstone GL, Parker GB. Is behavioral inhibition a risk factor for depression? Journal of Affective Disorders .

Oct 2006;95(1-3):85-94.

Oct 2006;95(1-3):85-94. - Muris P, Merckelbach H, Schmidt H, Gadet B, Bogie N. Anxiety and depression as correlates of self-reported behavioral inhibition in normal adolescents. Behavior Research and Therapy . 2001;39(9):1051-1061.

- Hayward C, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB. Linking self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition to adolescent social phobia. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Dec 1998;37(12):1308-1316.

- Neal JA, Edelmann RJ, Glachan M. Behavioral inhibition and symptoms of anxiety and depression: is there a specific relationship with social phobia? British Journal of Clinical Psychology . Nov 2002;41(Pt 4):361-374.

- Sportel BE, Nauta MH, de Hullu E, de Jong PJ, Hartman CA. Behavioral Inhibition and Attentional Control in Adolescents: Robust Relationships with Anxiety and Depression. Journal of Child and Family Studies . Apr 2011;20(2):149-156.

- Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S.

Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Feb 1994;103(1):103-116.

Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Feb 1994;103(1):103-116. - Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology . May 1998;107(2):179-192.

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry . Nov 1996;53(11):1033-1039.

- Lonigan CJ, Hooe ES, David CF, Kistner JA. Positive and negative affectivity in children: confirmatory factor analysis of a two-factor model and its relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology . Jun 1999;67(3):374-386.

- Joiner TE, Jr., Catanzaro SJ, Laurent J. Tripartite structure of positive and negative affect, depression, and anxiety in child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology . Aug 1996;105(3):401-409.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology . Aug 1996;105(3):401-409. - Lonigan CJ, Carey MP, Finch AJ, Jr. Anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: negative affectivity and the utility of self-reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology . Oct 1994;62(5):1000-1008.

- Anthony JL, Lonigan CJ, Hooe ES, Phillips BM. An affect-based, hierarchical model of temperament and its relations with internalizing symptomatology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology . Dec 2002;31(4):480-490.

- Chorpita BF. The tripartite model and dimensions of anxiety and depression: an examination of structure in a large school sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology . Apr 2002;30(2):177-190.

- Block JH, Gjerde PF. Personality antecedents of depressive tendencies in 18-year-olds: a prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology . May 1991;60(5):726-738.

- van Os J, Jones P, Lewis G, Wadsworth M, Murray R.

Developmental precursors of affective illness in a general population birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry . Jul 1997;54(7):625-631.

Developmental precursors of affective illness in a general population birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry . Jul 1997;54(7):625-631. - Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S. Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Psychol . Feb 1994;103(1):103-116.

- Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM, Hooe ES. Relations of positive and negative affectivity to anxiety and depression in children: evidence from a latent variable longitudinal study. Journal of Consultunf and Clinical Psychology . Jun 2003;71(3):465-481.

- Rende RD. Longitudinal relations between temperament traits and behavioral syndromes in middle childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry . Mar 1993;32(2):287-290.

- Dougherty LR, Klein DN, Durbin CE, Hayden EP, Olino TM. Temperamental Positive and Negative Emotionality and Children's Depressive Symptoms: A longitudinal prospective study from age three to age ten.

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29(4):462-488.

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29(4):462-488. - Hayden EP, Klein DN, Durbin CE, Olino TM. Positive emotionality at age 3 predicts cognitive styles in 7-year-old children. Development and Psychopathology . Spring 2006;18(2):409-423.

- Lahat A, Hong M, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition: is it a risk factor for anxiety? International Review of Psychiatry . Jun 2011;23(3):248-257.

- Rapee RM. The development and modification of temperamental risk for anxiety disorders: prevention of a lifetime of anxiety? Biological Psychiatry . Nov 15 2002;52(10):947-957.

Notes

- “Upward” and “downward” information processing strategies are two complementary cognitive processes. The "bottom-up" strategy refers to processes that involve sensory stimulation leading to perceptual processing and subsequent cortical interpretation. In general, the structures involved are, firstly, the subcortical, limbic, then the cortical areas of the brain.

"Downstream" processing refers to the control or modulation of subcortical or limbic processing by cortical regions. – (approx. per.)

"Downstream" processing refers to the control or modulation of subcortical or limbic processing by cortical regions. – (approx. per.) - A brain structure believed to be involved in the detection of a threat or novelty and the production of a conditioned response in connection with the experience of fear.

- The most initial part of the anterior cerebral cortex, located behind the frontal bone. This region of the brain is involved in higher-level executive functions such as attention control, emotion regulation, conflict resolution, complex goal-directed behavior planning, and decision-making processes.

- Subdivision of the anterior cingulate cortex responsible for error detection, response and conflict monitoring, anticipation, attention, motivation, and regulation/impairment of emotional response.

For citation:

Fox NA, Frenkel TI. Temperament in early childhood and the development of anxiety and depression. In: Tremblay RE, Buavan M, Peters RDeV, eds. Rapi RM, ed. Topics. Encyclopedia of early childhood development [online]. https://www.encyclopedia-deti.com/trevozhnost-i-depressiya/ot-ekspertov/temperament-v-rannem-detstve-i-razvitie-trevozhnosti-i. Published: March 2013 (English). Viewed on December 9, 2022

In: Tremblay RE, Buavan M, Peters RDeV, eds. Rapi RM, ed. Topics. Encyclopedia of early childhood development [online]. https://www.encyclopedia-deti.com/trevozhnost-i-depressiya/ot-ekspertov/temperament-v-rannem-detstve-i-razvitie-trevozhnosti-i. Published: March 2013 (English). Viewed on December 9, 2022

Text copied to clipboard ✓

Types of attention disorders in children and related behavioral disorders

The function of attention and its role in the regulation of behavior is one of the most urgent problems of both fundamental (psychology and psychophysiology) and clinical (neurology and psychiatry) sciences.

One of the pillars of Russian psychology L.S. Vygotsky wrote: "The history of a child's attention is the history of the organization of his behavior" [1]. K. Buhler considered attention as the driving force in the development of the child [2]. Attention, as one of the most important cognitive functions, provides control and organization of information processing processes [3, 4]. The role of attention in the organization of cognitive activity is especially high in children of primary school age, which is characterized by the beginning of systematic schooling, which requires a change in the level of voluntary organization of mental processes [5].

The role of attention in the organization of cognitive activity is especially high in children of primary school age, which is characterized by the beginning of systematic schooling, which requires a change in the level of voluntary organization of mental processes [5].

According to A.R. Luria [6], attention is a factor that ensures the selectivity and direction of mental processes. He wrote that attention is both a process of isolating elements essential for mental activity and a process of maintaining control over other areas of mental activity.

D.N. Uznadze [7] did not consider attention only in the context of cognitive functions. In his opinion, attention is significantly related to behavior and determines its success.

M. Rothbart et al. [8] suggested that good attention development helps to carry out emotional regulation, and a high level of attention control is associated with a low level of negative affects. According to N. Eisenberg and M. Sulik [9], the ability to control the level of attention is an index of emotional regulation. In this regard, it is interesting to note the studies by S. Calkins and N. Fox [10], the results of which showed that children with greater ability to control attention better control emotions and behavior. According to A. Diamond [11], attention together with working memory and cognitive flexibility are the three main components underlying the organization of executive functions.

In this regard, it is interesting to note the studies by S. Calkins and N. Fox [10], the results of which showed that children with greater ability to control attention better control emotions and behavior. According to A. Diamond [11], attention together with working memory and cognitive flexibility are the three main components underlying the organization of executive functions.

In 1975, M. Posner introduced the term “cognitive control” in his book “Attention and cognitive control” [12]. Currently, cognitive control is understood as the ability for cognitive analysis, anticipation and planning of activities. E.A. Sergienko formulated the main functions of cognitive control: “Cognitive control is responsible for switching between activities, maintaining current activities, and suppressing external impulses” [13].

Attention problems are one of the most common reasons for parents to visit a pediatric neurologist. Given the extreme importance of the development of attention for children and the high frequency of disorders of this function, we attempted to create a typology of attention disorders in childhood.

Types of attention/disorder in childhood

The following types of attention development in children were distinguished: normal, borderline and pathological.

Normal type

"Ideal" children. They are characterized by the absence of disturbances in attention and behavior and do not require drug therapy and psychotherapeutic correction.

Features of temperament . Temperament is currently defined as biologically determined individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation [14, 15]. Children with a normal type of attention demonstrate excessive activity without significant impairment of attention. At the same time, such hyperactivity usually does not lead to significant difficulties in learning and communicating with peers.

M. Rothbart et al. [16] distinguish three factors (scales) of temperament, each of which includes a number of psychological traits: the first factor is “extraversion” (positive emotionality), it is expressed by the desire for communication, pleasure from new situations, a high level of activity, impulsiveness; the second factor - "negative emotionality", includes shyness, a feeling of discomfort from new situations, fear, anxiety; the third factor - "volitional regulation" ("self-control"), is described by the authors as the ability to suppress the dominant reaction in order to implement a subdominant one, which is more adequate in a given situation. Persons with a high level on the “volitional regulation” scale are characterized by diligence, perseverance, reliability and responsibility.

Persons with a high level on the “volitional regulation” scale are characterized by diligence, perseverance, reliability and responsibility.

Attention disorders due to competing motivation : an intellectually gifted child does not receive sufficient stimulation, as he may be occupied with other (more interesting or important) thoughts or activities [17, 18]. Excessive stimulation : the receipt of too much information, improperly organized educational process can cause situational hyperactivity in a child [18].

Border Type

"Low cognitive tempo" (sluggish cognitive tempo). Such children are characterized by a general decrease in activity, a tendency to daytime sleepiness, immersion in their thoughts and fantasies [19-21]. This condition can also be observed in healthy children during periods of excessive stress, and in some pathological conditions, such as asthenic disorders, attention deficit disorder (ADD) without hyperactivity. Educational activity in such children is characterized by difficulties in entering the task, rapid exhaustion, fluctuations in working capacity, etc. [19, 22].

Educational activity in such children is characterized by difficulties in entering the task, rapid exhaustion, fluctuations in working capacity, etc. [19, 22].

Overfocused attention. These children are characterized by a lack of flexibility in their psychological attitude, difficulties in switching and focusing attention [18, 23]. They have difficulty adapting to new requirements and situations, the desires of other children, which makes them stand out during social contacts. This entails perseveration, slowness, avoidance of contact and seriously affects the child's behavior in society. Children with overfocused attention are more prone to anxiety and affective (depression) disorders than to behavioral and asocial ones [18].

Primary learning difficulties. In such cases, the child is not able to cope with cognitive tasks that are difficult for him. At preschool age, these children do not show problems associated with insufficient attention.

Pathological type

Such children do not have significant developmental disorders, except for the development of attention and associated regulatory and behavioral disorders.

ADD with hyperactivity (ADHD). According to the literature [24-26], this syndrome occurs in 5-7% of children, significantly more often in males. So, M. Skounti et al. [27] identified signs of ADHD in 8% of the examined schoolchildren and only in 3.8% of schoolgirls. It should be noted that some "blurring" in the existing criteria for making this diagnosis sometimes leads to overdiagnosis of ADHD [28, 29].

Clinical manifestations of ADHD are defined by three main symptoms: inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. Impulsivity is understood as the impossibility of controlling one's impulses. There are cognitive impulsivity (reflecting hasty thinking) and behavioral impulsivity (reflecting difficulty in suppressing reactions). Interesting is the work of V. Douglas [30], who put forward the theory of “four major deficits” at the heart of the disease: 1) reduced ability to hold attention; 2) weakness of inhibition of impulsive behavior; 3) weakness of modulation of the level of activating influences during a situational request; 4) an unusually strong propensity for immediate reward.

Children with ADHD have a lack of continuous (supported) attention, which manifests itself in the impossibility of long-term performance of an uninteresting task. In this regard, it is necessary to note the studies by P. Leung and K. Conolly [31], who did not find a pronounced deficit of sustained attention in children with this pathology and noted that children with ADHD are more likely to have a deficit of selective attention, which is manifested by increased distractibility to extraneous stimuli, especially if these stimuli are bright, interesting.

According to R. Barkley's model [32], ADHD is characterized not so much by attention disturbances as by a deficit in inhibition (inhibition), i.e., a person's ability to control impulsive or automatic reactions. In his opinion, the basis of the disease is a disorder of executive functions (executive desfunction), the implementation of which is carried out mainly by the prefrontal sections of the cerebral cortex. Inhibition deficiency contributes to increased distractibility and impairs sustained attention. Along with this, violations of executive functions lead to hyperactivity and behavioral disorders.

Along with this, violations of executive functions lead to hyperactivity and behavioral disorders.

ADD (without hyperactivity) with a predominance of inattention

According to R. Milich et al. [33], this disorder is a completely independent disease. Such children give the impression of inhibited, drowsy, timid, shy. They perceive information more slowly than their peers, they remember worse. They are characterized by the state of low cognitive pace described above. There is evidence in the literature [32] that this type occurs in 30–50% of children with ADHD. The results of our studies indicate that this subtype is detected in 16.6% of children with ADHD [34]. Patients with this type of ADHD are characterized by severe manifestations of inattention and minor manifestations of hyperactivity. At the same time, their impulsiveness indicators remain within the age norm. In our studies, the severity of asthenic symptoms in ADHD was greater than in ADHD [35]. In addition, data from a psychophysiological study indicate a significantly higher level of attention deficit in children with ADHD compared to children with ADHD. At the same time, the level of impulsivity was significantly higher in children with ADHD [35].

In addition, data from a psychophysiological study indicate a significantly higher level of attention deficit in children with ADHD compared to children with ADHD. At the same time, the level of impulsivity was significantly higher in children with ADHD [35].

According to A.R. Agris et al. [36], if disorders of frontostriate interactions play a leading role in the pathogenesis of ADHD, then ADD is characterized by weakness of frontoparietal interactions. The leading cognitive impairment for ADD is a deficit in working memory, another component of executive functions. Thus, according to these authors, ADD can be described as a regulatory-activation deficit with a weakness in working memory, while ADHD can be described as a regulatory-motor deficit with difficulties in voluntary inhibition [36]. N. Ahmadi et al. [37] observed that children with ADHD are characterized by more pronounced impairment of executive functions than children with ADHD.

Secondary attention disorders. These disorders are associated with marked cognitive, socio-emotional, sensory and neurological deficits. This group includes children with various types of mental retardation, mental retardation, asthenic disorders.

These disorders are associated with marked cognitive, socio-emotional, sensory and neurological deficits. This group includes children with various types of mental retardation, mental retardation, asthenic disorders.

Recently, the attention of researchers has been attracted by the possibility of combining ADHD and autism spectrum disorders (ASD) [38–40]. It should be noted that children with ASD have not only a deficit of attention, but also a wider range of pronounced cognitive impairments. In our opinion, in this case we can rather speak not of primary, but of secondary attention disorders.

Treatment of attention disorders

In Russia, nootropic drugs have traditionally been used to treat cognitive impairments, i.e. drugs that positively affect the higher integrative functions of the brain, the main manifestation of which is the improvement of learning and memory processes in case of their impairment [41]. A common neurophysiological correlate of the pharmacological effect of nootropics is their facilitating effect on glutamatergic transmission, enhancement and lengthening of long-term potentiation. Nootropic and neuroprotective drugs used in the treatment of cognitive impairment in children include Cortexin, Pantogam, Nooklerin, Phenibut (Noofen, Anvifen), Picamilon, etc.

A common neurophysiological correlate of the pharmacological effect of nootropics is their facilitating effect on glutamatergic transmission, enhancement and lengthening of long-term potentiation. Nootropic and neuroprotective drugs used in the treatment of cognitive impairment in children include Cortexin, Pantogam, Nooklerin, Phenibut (Noofen, Anvifen), Picamilon, etc.

Peptide bioregulator Cortexin, included in this group of drugs, is a complex of polypeptides isolated from the cerebral cortex of calves and pigs not older than 12 months of age by the method of acetic acid extraction. Cortexin improves memory and learning performance under the action of amnestic agents in animals, which indicates its nootropic activity. T.N. Platonov et al. [42] showed the high efficiency of Cortexin in the treatment of various cognitive impairments in children.

In our previous studies [43], it was found that after a course of Cortexin, clinical improvement occurred in approximately 72% of patients with ADHD. The best result was obtained in the treatment of children with ADD. These data were confirmed by an objective reduction in inattention and a reduction in reaction time, which were registered using a psychophysiological study. The results of the repeated neuropsychological study showed a significant improvement in the performance of Ozeretsky's neuropsychological tests and finger counting. In addition, positive clinical dynamics was accompanied by an improvement in electroencephalographic parameters. Only in 2.0% of cases there was a slight increase in impulsivity after the course of treatment. Other side effects are not registered. The obtained results make it possible to recommend Cortexin for the treatment of children with various forms of ADHD.