Psychology behind self mutilation

A new look at self-injury

What makes young people cut, scratch, carve or burn their skin, hit or punch themselves, or even bang their heads against a wall?

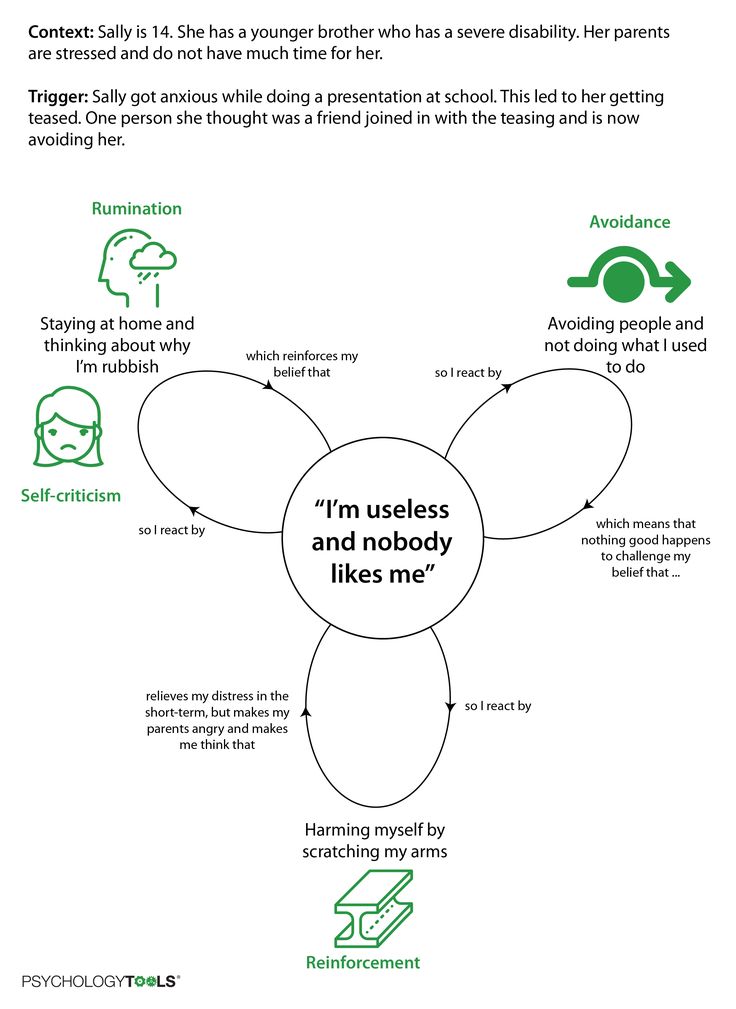

For years, psychologists theorized that such self-harming behaviors helped to regulate these sufferers' negative emotions. If a person is feeling bad, angry, upset, anxious or depressed and lacks a better way to express it, self-injury may fill that role.

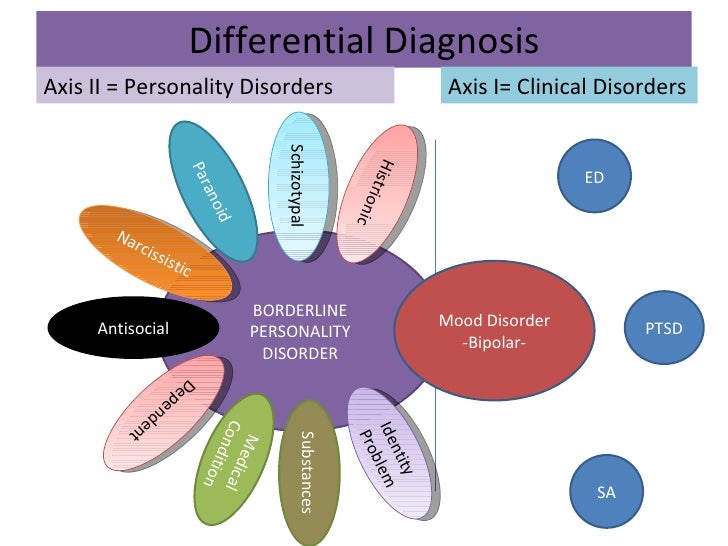

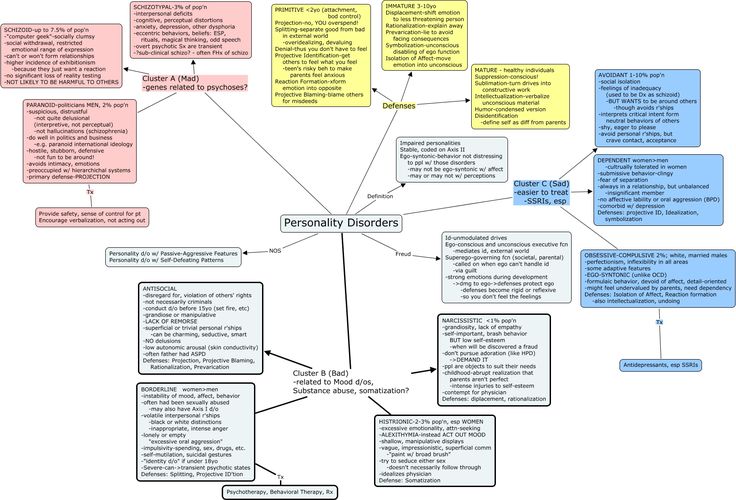

Also known as non-suicidal self-injury, or NSSI, the condition is classified in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (2013) as a "new disorder in need of further study," as well as a symptom of borderline personality disorder, which is marked by such tendencies as emotional instability, unstable relationships and chronic feelings of emptiness. (See companion article on who is more likely to self-injure.)

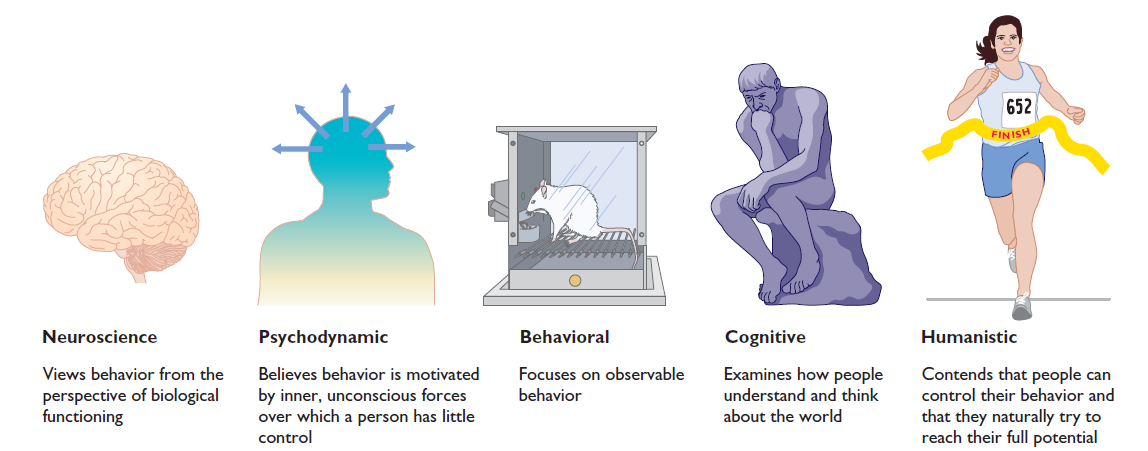

For treatment, practitioners often turn to dialectical behavior therapy because of its effectiveness in treating borderline personality disorder in general. But now, two researchers at Harvard University are taking a different tack on this inquiry. Joseph Franklin, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of suicide researcher and psychologist Matthew Nock, PhD, wanted to step back from earlier assumptions about self-injury and think more broadly about what might be driving self-harming behavior.

Although researchers generally accepted that NSSI helped people deal with strong negative emotions, Franklin wanted to understand more about why that was the case. Around the same time, Jill Hooley, DPhil, who heads Harvard's experimental psychopathology and clinical psychology program, was finding that people who engaged in NSSI would endure experimentally induced pain for much longer than control participants, and she wondered why. What factors kept self-injurers from apparently acting in their best interests and avoiding pain? And could identifying those factors help explain why people were motivated to engage in NSSI in the first place?

"We were both interested in knowing why people hurt themselves," says Hooley, "but Joe was focused on the possible [emotional] benefits of NSSI and I was looking at the motivations behind it. "

"

While over time their interests and investigations have converged, when they first discovered each other's work, "we were like, ‘Oh, this makes so much sense!'" Hooley adds. "This is how the various findings fit together. It was very exciting."

Why self-injury?

Franklin started his investigation with one of the central questions in the field: Why would people report feeling better after hurting themselves?

"It seemed very strange to me, and to a lot of other people," says Franklin. Most studies on the topic had relied on self-reports, "but I wanted to look at this experimentally and biologically to see if it was really true."

In a 2010 study in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology, Franklin and colleagues used a task that measured people's defensive eye-blink responses before and after they dipped their hands into ice-cold water. The results indicated that self-injurers do in fact feel better afterward, he found.

A second finding was more surprising.

"Everyone else reported feeling better, too," he says.

That is, healthy controls showed exactly the same degree of physiological defensiveness and subsequent physiological relief as those who engaged in self-injury. In a 2013 paper in Clinical Psychological Science, Franklin's team replicated the finding and also showed that most people had equivalent changes in positive emotions in response to shocking stimuli.

Franklin then turned to the pain literature to see if he could gain more understanding. There, he discovered something described by psychologists 70 years ago: a phenomenon called pain offset relief. According to this concept, virtually everyone experiences an unpleasant physical reaction to a painful stimulus. Removing the stimulus does not return the individual to their pre-stimulus state, however. Rather, it leads them into a short but intense state of euphoria.

Using a technique called pain offset relief conditioning, those scientists also found that if you paired the pain with a stimulus, over time, people would react more favorably to the pain because they had learned to associate it with pain relief. For example, when researchers shocked rats and then presented them with a pleasant odor, over time, the rats began seeking out the smell.

For example, when researchers shocked rats and then presented them with a pleasant odor, over time, the rats began seeking out the smell.

Testing this paradigm with various types of shocks and physiological measures, Franklin continued to find powerful pain-offset relief effects in all of his participants, self-injurers and controls alike. People who self-injure may unwittingly be tapping into this mechanism, Franklin surmises. The first time they hurt themselves, they experience unpleasant pain. But when they keep doing it and experience pain relief, they begin to associate cutting or other forms of self-injury with relief, and they return for more.

"That is contrary to what a lot of people assumed and what a lot of treatments focus on," Franklin says. "People, including myself, were thinking there was something unique about these folks" — that if they were injuring themselves repeatedly, they must perceive or experience pain differently from others.

"But that doesn't appear to be the case at all," he says. "It looks like it's this natural phenomenon that [people who self-injure] happen to be tapping into."

"It looks like it's this natural phenomenon that [people who self-injure] happen to be tapping into."

Harmonic convergence

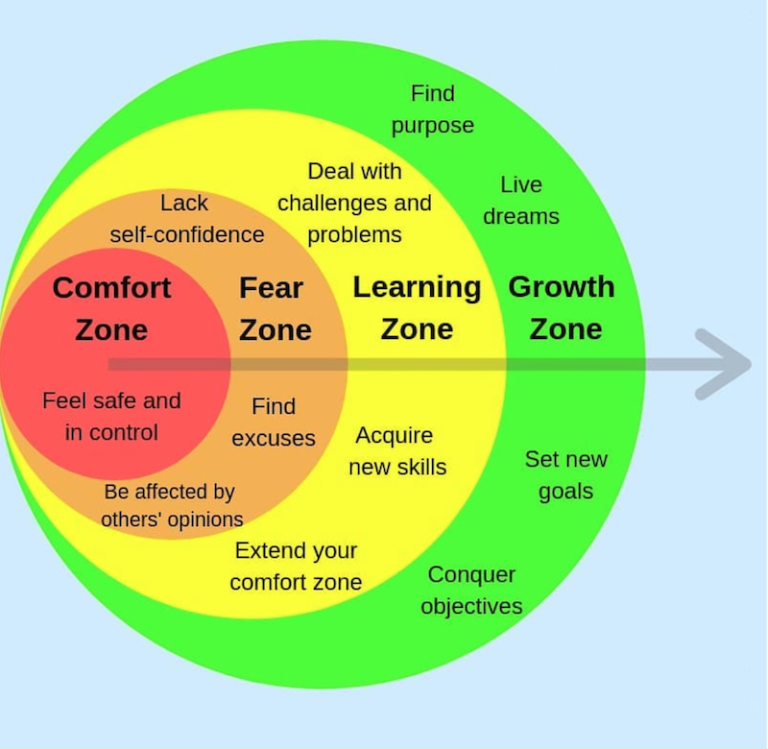

The next research question may seem obvious: If anyone can experience pain relief by inflicting pain on themselves, why don't more of us do it? To ask the question a different way, why do self-injurers harm themselves instead of opting for healthier or more pleasant ways of relieving emotional pain, such as watching a movie, meeting a friend or going to a yoga class?

As Franklin was pondering this question in light of possible benefits to the self-injurer, Hooley and her team wondered about psychological explanations. She already knew that self-injurers would endure physical pain for longer, but why? Was this increased pain endurance linked to some of the psychological factors that are commonly associated with self-injury — depression, hopelessness or dissociation, for instance?

Somewhat surprisingly, her team found no significant associations. So having interviewed all of her self-injuring research participants in detail, she returned to her notes in search of clues.

So having interviewed all of her self-injuring research participants in detail, she returned to her notes in search of clues.

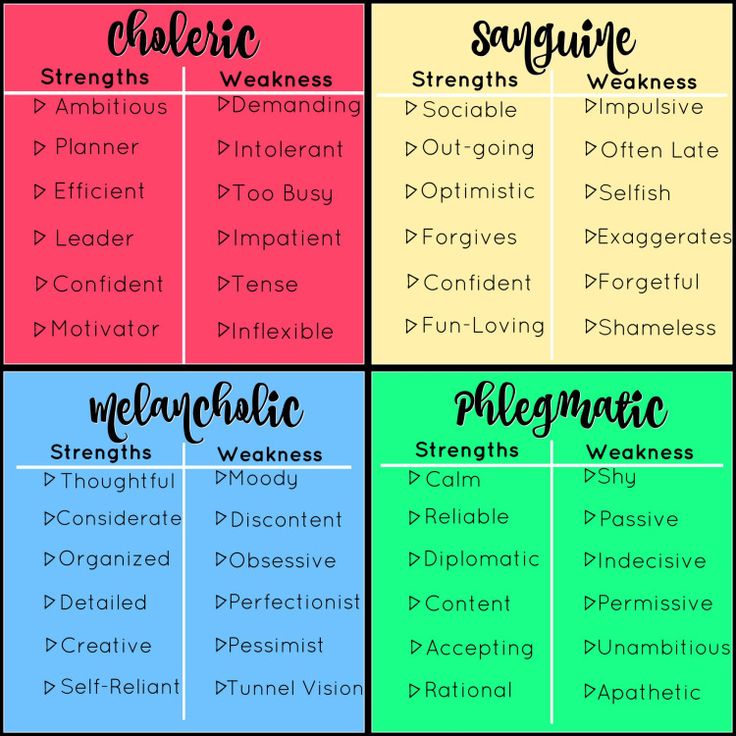

That's when one factor stood out: How often they spontaneously described themselves as being "bad," "defective" or "deserving of punishment."

"It was as if harming themselves or experiencing pain was somehow congruent with their highly negative self-image," she explains.

To test this possibility, her team developed a measure that specifically assesses self-beliefs about being "bad" and deserving criticism. This time, they found an answer: The higher a person's score on negative self-beliefs, the longer they were willing or able to endure pain.

Given his conversations with Hooley, Franklin was thinking along similar lines. When he asked himself why people would undertake this behavior, he looked at it in context of the fact that most people probably like themselves and therefore don't want to hurt themselves. In ongoing, still unpublished work, he asked participants to rate words like "me," "myself" and "I" on a 10-point scale ranging from most unpleasant to most pleasant. Most people rated themselves between a seven and eight, but self-injurers gave themselves only a two or a three.

Most people rated themselves between a seven and eight, but self-injurers gave themselves only a two or a three.

Likewise, Franklin reasoned that most people would not be overly fond of stimuli that depict blood, wounds, knives or equivalent images. But he surmised that people who self-injure might feel differently, partly because his findings suggested they would associate such images with pain relief. A 2014 study in Clinical Psychological Science shows this is the case: People who had engaged in NSSI over the past year or who had 10 or more lifetime episodes of self-cutting were much less likely to report aversion to these kinds of stimuli than non-injuring controls.

Meanwhile, Hooley has recently completed a neuroimaging study looking at how people process such stimuli.

"We're predicting that images of self-injury will activate reward-processing areas in the brains of people who engage in NSSI," she says, "but not in non-self-injuring controls."

Treatment targets

Now, based on some of these findings, the researchers and their colleagues are exploring new ways to treat self-injury.

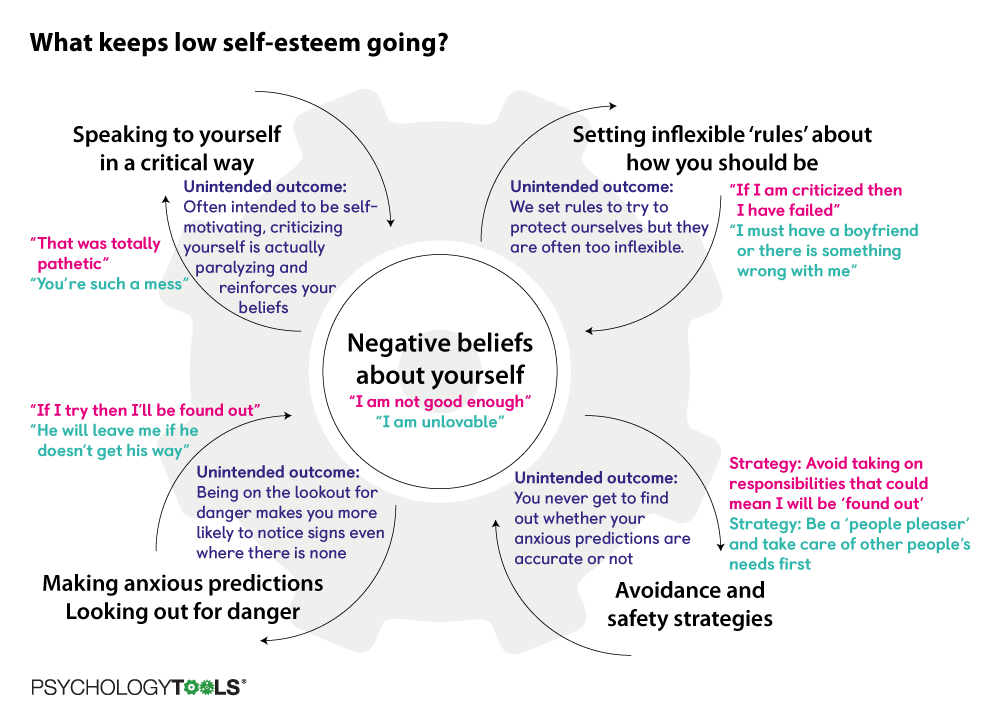

In keeping with her discovery that self-worth is an important intervention variable, Hooley is taking a cognitive route. Clinicians might be able to lift self-injurers' inclination to do bad things to themselves, she thinks, by helping them change what are often deeply engrained negative self-views.

In a 2014 paper in Clinical Psychological Science, Hooley and then-graduate student Sarah A. St. Germain report on the results of a five-minute intervention they developed that seeks to change beliefs about self-worth, but in ways that are believable, grounded in reality and relatively subtle.

"You can't do this by simply telling people who self-injure that they should think more positively about themselves," she comments.

The team asked people with NSSI and controls to choose which positive characteristics on a list best described themselves, and then to elaborate on some of those characteristics in detail using examples. Before and after the intervention, the researchers tested people's pain endurance by recording how long they kept their fingers clamped in a pressure device. (To control for noncognitive effects of good mood, the researchers also included a "happy music" condition with NSSI and healthy controls.)

(To control for noncognitive effects of good mood, the researchers also included a "happy music" condition with NSSI and healthy controls.)

After the intervention, self-injurers in the cognitive condition kept their fingers in the device for only about half the time they did initially. And the more their sense of self-worth increased, the less willing they were to stay in the painful situation. Meanwhile, the pain endurance of those in all other conditions remained the same. She has not yet looked at effect duration.

"The natural and adaptive response is to say, ‘I'm done with this.' But people who engage in self-injury don't necessarily see pain as something to escape from," Hooley explains. Instead, experiencing pain validates their sense of being a bad or damaged person.

Increasing their sense of self-worth may undermine this propensity, she adds.

"The more valuable that people feel, the less willing they are to endure a bad situation," she says. "Conversely, the worse people feel about themselves, the more inclined they will be to try [painful] methods of mood regulation that most other people would not even consider. " Franklin, meanwhile, is using his findings to test a behavioral intervention using novel counter-conditioning techniques. The intervention targets self-injurers' propensity to pair pain images with relief, and to harbor negative associations to self-related words. The study is under review, but preliminary evidence suggests that changing people's feelings about self-related words and NSSI-related images can be effective treatments, Franklin says.

" Franklin, meanwhile, is using his findings to test a behavioral intervention using novel counter-conditioning techniques. The intervention targets self-injurers' propensity to pair pain images with relief, and to harbor negative associations to self-related words. The study is under review, but preliminary evidence suggests that changing people's feelings about self-related words and NSSI-related images can be effective treatments, Franklin says.

Studies also show that associating pain with relief and negative thoughts with self-related words are good predictors of future self-injury, suggesting such tasks could be used as early screening tools for NSSI, report Franklin and colleagues in a 2014 article in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology.

These efforts are a step toward effectively treating people who self-injure, and Hooley and Franklin hope that psychologists who create and study interventions will add their own insights to the mix.

"We hope that our research is improving our knowledge about how self-injury works and providing novel treatment targets," Franklin says. "Our goal is for researchers and clinicians to use their creativity to attack these targets in new ways."

"Our goal is for researchers and clinicians to use their creativity to attack these targets in new ways."

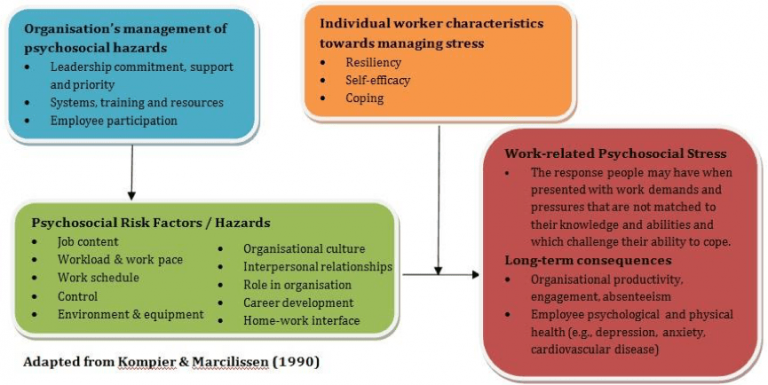

Looking at the Underlying Causes

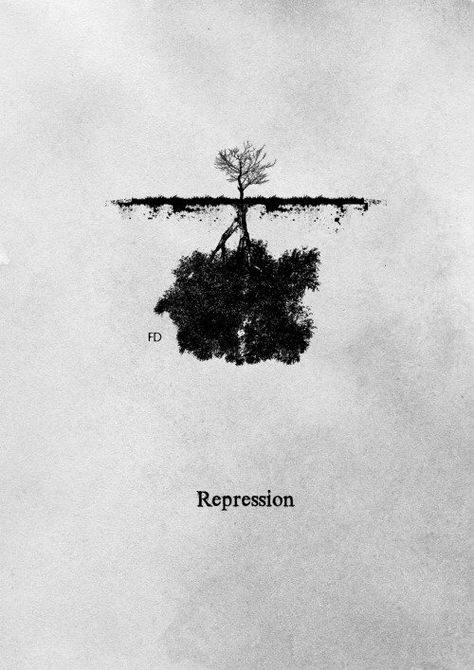

Self-harm is the act of hurting oneself, whether it is physical or emotional, intentional, or non-intentional. When many individuals hear the term “self-harm,” they often associate it with intentional physical self-harm behaviors such as cutting, burning, or skin picking, but self-harm can present in other ways as well. Unhealthy and self-destructive behaviors that are either intentional or unintentional are often highly linked to emotional self-harm. Emotional self-harm comes in all forms and can be just as dangerous as physical self-harm. Self-harm behavior can lead to mental health disorders, eating disorders, and substance abuse disorders, but what is it specifically that causes an individual to engage in self-harm? The psychology behind self-harm is multifactorial meaning that there is no one single trigger or cause. Research shows that self-harm frequently starts in adolescence and is particularly prevalent in homes where there is a repressive environment, where negative emotions are swept under the carpet or where feelings aren’t discussed. One factor common to many people who self-harm is that they were taught at an early age that their feelings were “bad” and “wrong.”

One factor common to many people who self-harm is that they were taught at an early age that their feelings were “bad” and “wrong.”

Psychology behind cutting

Cutting is the most common form of physical self-harm, formally known as non-suicidal self-injury. Like other forms of self-injury behavior, cutting is not a form of suicide but rather an unhealthy coping mechanism individuals use to relieve stress. Knives, paper clips, razors, and other sharp objects are commonly used in this behavior. Cutting is part of a vicious cycle associated with anger, sadness neglect followed by a quick mental relief from cutting. Once the act of cutting is completed and the feelings of mental relief dissipate, the individual if often overtaken by feelings of guilt and shame, which then turn to anger and neglect until the cycle continues again. Individuals who have a past or current history of abuse, trauma, low self-esteem, family conflict, bullying, and sexual identity conflicts are often at risk for extreme stress and negative feelings that he/she may not be able to control. As a result, cutting is used as an unhealthy coping mechanism to relieve the stress and these negative feelings. Some individuals may even engage in cutting to numb their pain or actually feel pain because they are numbed from their negative emotions. Many individuals who engage in self-harm view this behavior as a psychological release, a way to unravel their deep underlying negative emotions and thoughts.

As a result, cutting is used as an unhealthy coping mechanism to relieve the stress and these negative feelings. Some individuals may even engage in cutting to numb their pain or actually feel pain because they are numbed from their negative emotions. Many individuals who engage in self-harm view this behavior as a psychological release, a way to unravel their deep underlying negative emotions and thoughts.

The psychology behind emotional self-harm

Emotional self-harm ranges from telling ourselves we are not good enough and becoming our own worst enemy to engaging in a pattern of destructive friendships and relationships. Emotional self-harm is tied to past events that occurred in childhood or adolescence. Maybe one’s parents were too strict, or there was a history of neglect, sexual abuse, a history of bullying, or maybe there was a coach or a teacher who always gave negative criticism. Emotional self-harm also occurs when the individual’s emotional needs are not met during their formative years. After years of being neglected or being told, one is not good enough; it becomes ingrained in their head to the point that the individual begins to believe it. As a result, they may seek out unhealthy co-dependent relationships, may engage in disordered eating to cover up their emotions or may sacrifice their own happiness at the expense of others because they so desperately want to be liked and accepted.

After years of being neglected or being told, one is not good enough; it becomes ingrained in their head to the point that the individual begins to believe it. As a result, they may seek out unhealthy co-dependent relationships, may engage in disordered eating to cover up their emotions or may sacrifice their own happiness at the expense of others because they so desperately want to be liked and accepted.

Reasons individuals engage in self-harm

- To feel a sense of control

- Express pain

- As a distraction

- As punishment

- To feel pleasure

- To feel anything at all

The psychology behind the treatment for self-harm

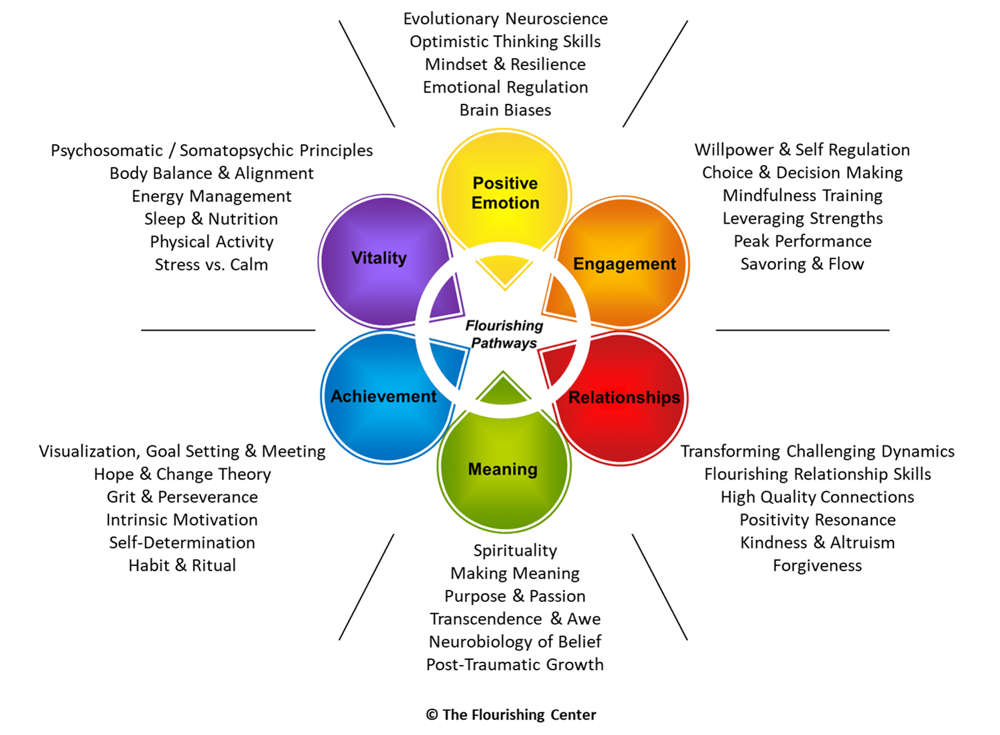

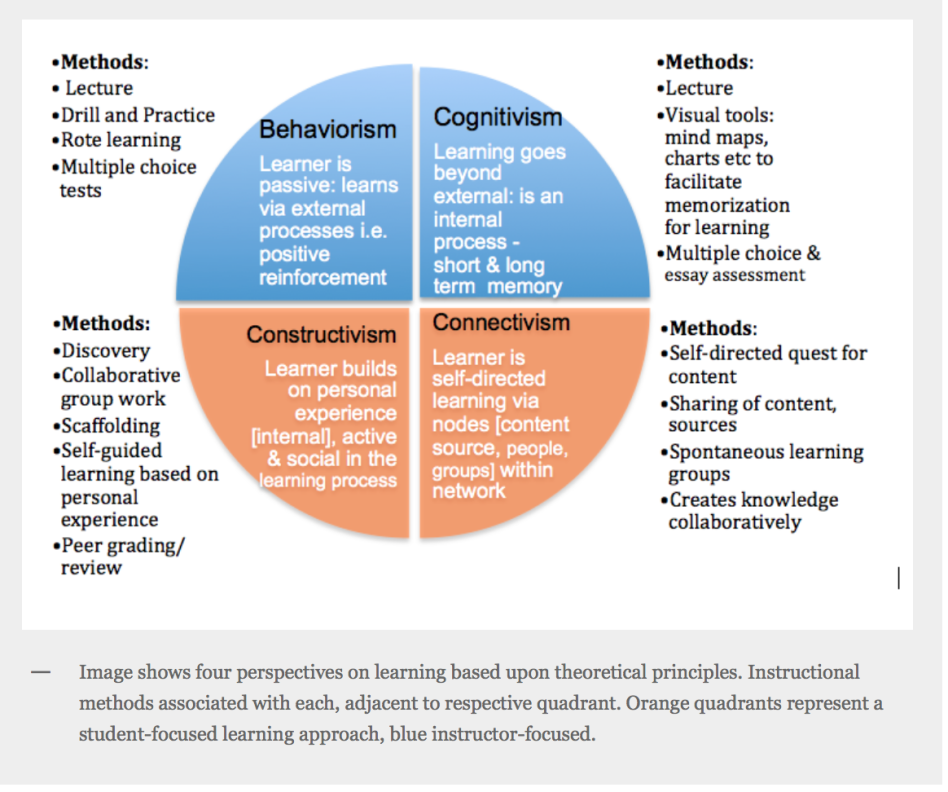

Psychotherapy is the mainstay treatment for individuals who engage in self-harm behaviors, whether it is physical or emotional self-harm. A recent study identified that psychological treatments specific to self-harm have better success than those that are more general in nature. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a short-term treatment approach that is very goal-oriented. This treatment approach focuses on identifying dysfunctional emotions, behaviors, and thoughts underlying the self-harm behaviors and then analyzing them and replacing them with more positive and healthier ways of dealing with the underlying triggers and stressors that are contributing to the self-harm behaviors.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a short-term treatment approach that is very goal-oriented. This treatment approach focuses on identifying dysfunctional emotions, behaviors, and thoughts underlying the self-harm behaviors and then analyzing them and replacing them with more positive and healthier ways of dealing with the underlying triggers and stressors that are contributing to the self-harm behaviors.

For instance, an individual may tend to magnify a negative situation rather than seeing it as part of reality. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) would work to identify that negative thought pattern, challenge it, and replace it with a thought pattern that is more realistic and positive.

Be healthy :: Self-mutilation: flight from emotions

They cut themselves with razors and other sharp objects. They burn themselves with cigarettes and soldering irons. Such wounds are rarely put on public display. In most cases, this "secret" is carefully hidden under clothing. If someone nevertheless notices a fresh scar and demands an explanation, they will receive in response: “burnt with an iron” or “cut with a kitchen knife.” Think, an accident, who does not happen to?

If someone nevertheless notices a fresh scar and demands an explanation, they will receive in response: “burnt with an iron” or “cut with a kitchen knife.” Think, an accident, who does not happen to?

... the vast majority of self-harming people have experienced physical and/or sexual abuse.

In fact, it doesn't even smell of domestic injuries, we are talking about self-harm, that is, deliberately causing physical harm to oneself without the intention of committing suicide. Approximately every hundredth person lives with this problem. If we talk only about teenagers, especially girls, then the numbers will be even higher.

Self-mutilation usually becomes an irresistible craving, a kind of addiction. People are well aware of how such behavior should look in the eyes of others, but they cannot help themselves. After all, their wounds on the body are a direct consequence and expression of spiritual wounds that they cannot get rid of. nine0005

Not masochistic or suicidal

Although “self-harmers” are, on average, more likely to think about suicide and even attempt suicide, their behavior is not directly related to suicide. On the contrary, one of the explanations they give for their actions is the desire to avoid suicide.

On the contrary, one of the explanations they give for their actions is the desire to avoid suicide.

Paradoxically, but self-mutilation is their way of self-help, if you like, self-treatment, albeit dangerous to health. Most often, these people say that in this way they cope with overwhelming emotions (anger, fear, self-disgust, despair), get out of a state of extreme stress or emotional numbness (“at least feel something”). nine0005

According to statistics, 67% of those who practice self-harm experience little or no pain during their actions. They rarely can explain the reason that causes them to harm themselves. However, they know exactly what they are achieving: after a “dose of suffering”, calmness and relief come.

Who is prone to such, to put it mildly, specific struggle with spiritual wounds?

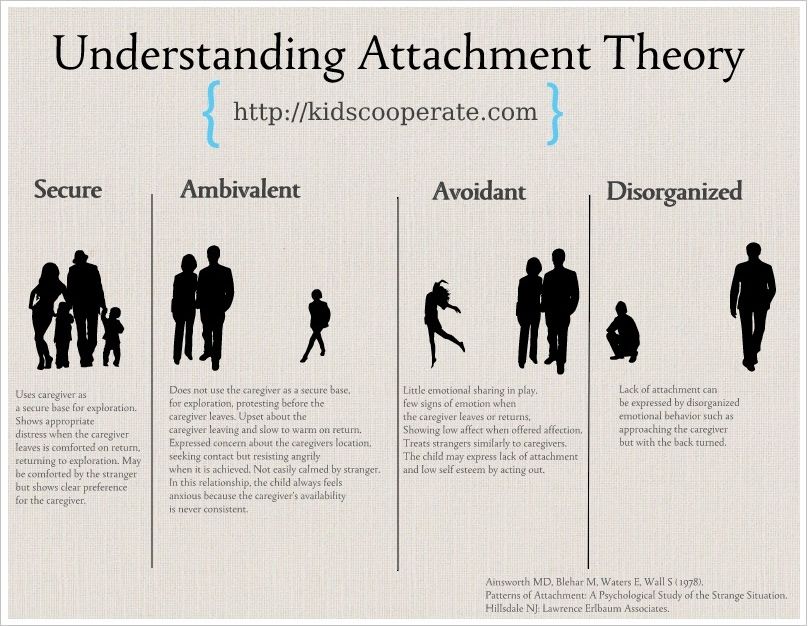

Researchers Van der Kolk and Herman conducted a study in 1991 among patients who cut themselves. It turned out that most of them were either physically or sexually abused in childhood, or grew up in an unhealthy family atmosphere, with parents who neglected their responsibilities. The third option is systematic bullying at school. nine0005

The third option is systematic bullying at school. nine0005

In addition, the study revealed the following patterns:

- the earlier the violence occurred, the higher the risk that, as an adult, a person will engage in self-harm;

- Sexual abuse is more likely to result in self-harm than physical or psychological abuse.

Van der Kolk and Herman's findings were later confirmed: indeed, the vast majority of self-harming people have experienced physical and/or sexual abuse. However, it is important to note that after all, “most” does not mean “all”. Some people who engage in self-harm have not been subjected to violence or other serious injuries. Scientists have come to the conclusion that there are people "predisposed" to the development of such behavior, and the trauma experienced only stimulates such a predisposition. nine0005

A rather curious explanation of self-mutilation was proposed by the psychologist Linehan in 1993. It looks like this: “People who practice self-harm grew up in an atmosphere that devalued their feelings. Families where violence exists will definitely guarantee such an atmosphere, but they can also be quite “normal” families. "Devaluation of feelings" means that the child from childhood could not talk about personal experiences and emotions, as he was ignored or ridiculed.

Families where violence exists will definitely guarantee such an atmosphere, but they can also be quite “normal” families. "Devaluation of feelings" means that the child from childhood could not talk about personal experiences and emotions, as he was ignored or ridiculed.

Finally, people with certain biological characteristics may be predisposed to self-harm. According to one such theory, self-harm leads to a sharp change in the level of certain substances in the brain, for example, the substance serotonin. This can lead to a sharp decrease in aggressive feelings, and as a result, a person gets the opportunity to "manage anger", which he cannot express at the address. nine0005

"Women's disease"

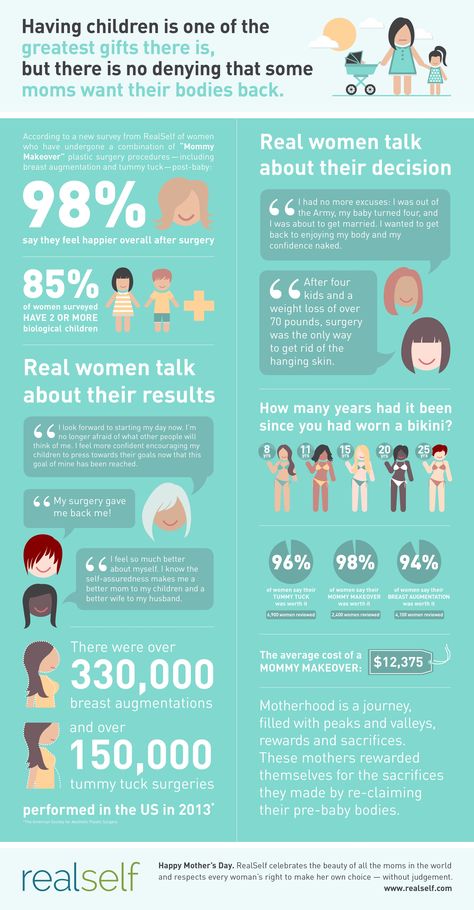

Although self-harm is thought to be most common among teenagers, this behavior can occur among people of any age, gender, nationality and economic status. However, most often self-mutilation occurs among women. According to various estimates, they make up from 67% to 85% of those who cause physical harm to themselves.

There are different explanations for why women are more prone to self-harm. The most popular theory of psychologist Miller. She believes that girls are taught from childhood to suppress anger and aggression, because it is "unfeminine" to show them. Of course, boys are also taught to suppress emotions, but with aggression and anger, it is easier for them. Men are allowed to throw them out "out", and women, due to the nature of their upbringing, more often direct them "on themselves." nine0005

On the other hand, the link between sexual violence and self-harm must be taken into account. Still, in most cases, girls and women suffer from sexual violence ...

Get rid of wounds

The "classic" treatment of a person suffering from self-harm involves isolation in the clinic, control of his behavior and the appointment of appropriate drugs - primarily antidepressants. Recently, however, most foreign experts have come to the conclusion that it is dangerous to physically prevent self-mutilation. This may backfire. nine0005

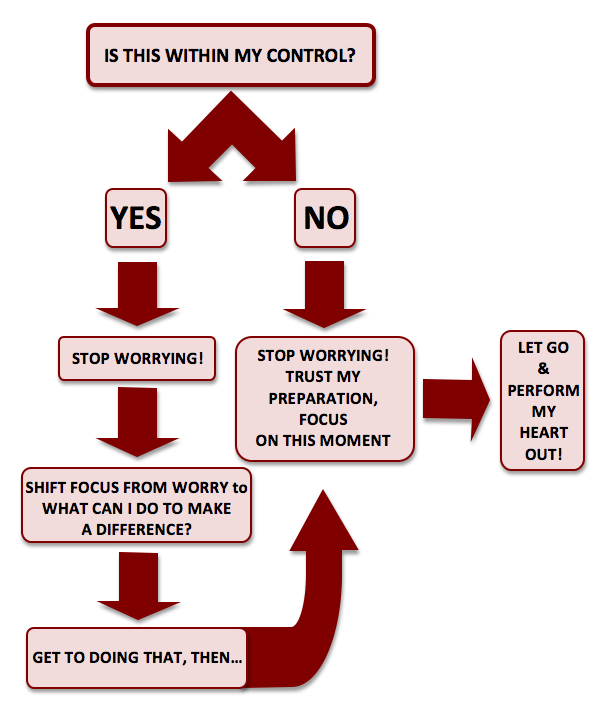

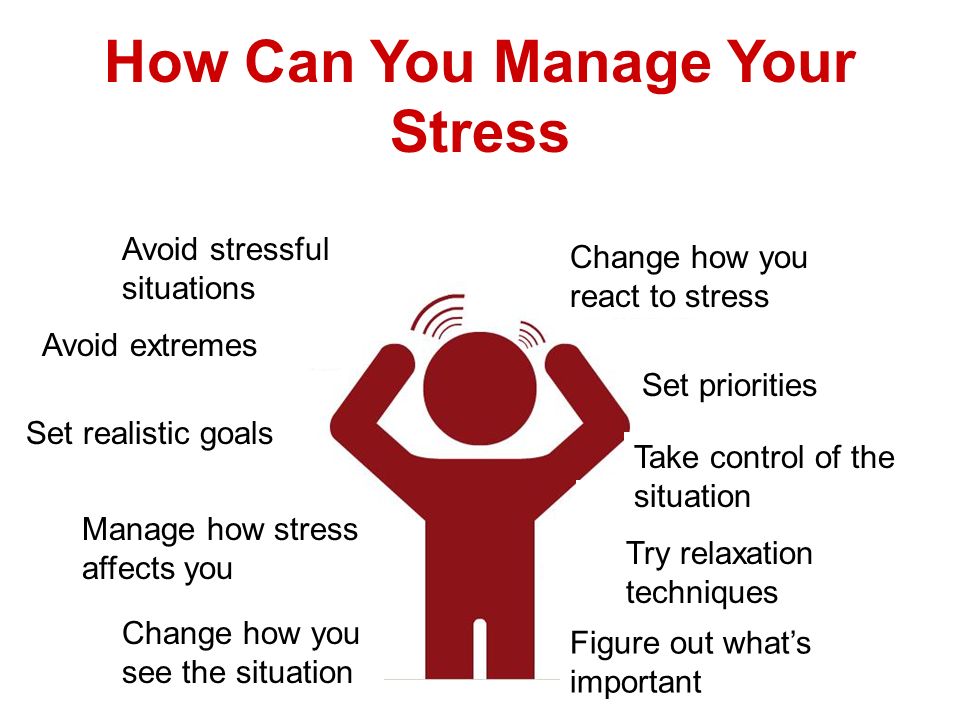

It is also useless to fight self-harm with the methods used to overcome "bad habits" like overeating or smoking. It is not just a habit or “addiction”, a person cannot give up self-harm if he does not receive alternatives - effective stress management methods.

Today, psychiatrists recommend starting with the prescription of antidepressants and various mood stabilizers in order to reduce the patient's craving for self-harm by reducing emotional distress. In addition to drug treatment, training in stress management skills will serve. nine0005

Since physical damage is only the “tip of the iceberg”, the next step in treatment should be psychotherapy, which will be aimed at solving problems that lie “under water”. This could be trauma work or family therapy. Here the key to success is the attitude of the patient himself, the desire to actively cooperate with specialists and look for his own path to healing.

Elizaveta Morozova

Psychosocial interventions for adult self-harm

Why is this review important?

Self-harm (HM), i. e. non-fatal (non-fatal) intentional self-poisoning/overdose and self-harm (self-injury), is an ongoing problem in many countries and is associated with a risk of future suicide. This causes suffering and pain to both patients and their families and friends, and places high demands on medical services. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the evidence for the treatment of patients with signs of self-harm (SH). nine0005

e. non-fatal (non-fatal) intentional self-poisoning/overdose and self-harm (self-injury), is an ongoing problem in many countries and is associated with a risk of future suicide. This causes suffering and pain to both patients and their families and friends, and places high demands on medical services. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the evidence for the treatment of patients with signs of self-harm (SH). nine0005

Who will be interested in this review?

Clinicians working with people who engage in self-harm, policy makers, people who engage in self-harm or are at risk of self-harm, and their families and relatives.

What questions does this review seek to answer?

This review is an update of a previous Cochrane review dated 1999, who found little to no evidence of a beneficial effect of psychosocial treatment on relapse (re-commitment) of CV. This update aims to evaluate the evidence for the effectiveness of psychosocial treatment for patients undergoing CV from a broader perspective on outcomes.

What studies were included in this review?

To be included in this review, the studies had to be randomized controlled trials of psychosocial interventions in adults with a recent CV. We searched electronic databases to identify all such clinical trials published on 29April 2015 and found 55 trials that met our inclusion criteria.

What does the evidence from this review tell us?

To date, there are many studies on the psychosocial treatment of HF in adults, with more recent years of trials from low- and middle-income countries such as China, Iran, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

Some moderate-quality evidence suggests that cognitive-behavioral (CB) psychotherapy (psychotherapy aimed at changing unbeneficial ways of thinking, behavior, and emotions) may help prevent recurrence of SR, although it did not reduce the overall incidence of SR. There were encouraging results (medium to very low quality small clinical trials) for other interventions aimed at reducing the frequency of FR in people with probable personality disorders (personality disorders, psychopathy), including group psychotherapy for managing emotions, mentalization (psychosocial therapy aimed at increasing understanding (awareness) of their own and other mental (mental, mental) states), and dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT; psychosocial therapy aimed at helping with the identification of initiating factors (triggers) leading to reactive behavior, and learning skills to emotionally cope with difficulties in life to avoid such reactions. While DPT was not associated with a significant reduction in recurrence of PV at final follow-up compared with conventional treatment, there was low-quality evidence suggesting a reduction in PV.

While DPT was not associated with a significant reduction in recurrence of PV at final follow-up compared with conventional treatment, there was low-quality evidence suggesting a reduction in PV.

There was no clear evidence to support the effectiveness of long-term exposure to DBT, case management, methods to improve treatment adherence, mixed multimodal (combined) interventions (including psychosocial therapy and remote contact interventions), remote contact interventions (postcards, emergency postcards and contact over the telephone), training in interpersonal problem solving skills), behavioral therapy, information and support, alcohol abuse treatment, home problem solving therapy, inpatient and outpatient (community) care, routine hospitalization, intensive outpatient treatment or long-term psychotherapy. nine0005

We had limited evidence from a subset of studies looking at differences in the effects of interventions between men and women. The trials reported no side effects other than suicidal behavior.