Prevention of schizophrenia

Is It Possible to Prevent Schizophrenia?

Written by Kara Mayer Robinson

Although there is no proven way to prevent schizophrenia, scientists are looking for ways to make it less likely.

Schizophrenia is a complex illness that may partly involve your genes. But events in your life may also play a role.

The condition can sometimes run in families. But there isn't one specific gene that causes it. And in some people who get schizophrenia, there are no signs of a family history of the illness.

It's possible that someone has genes linked to schizophrenia and then faces events that make them more likely to develop the disorder, says Julia Samton, MD, the director of Manhattan Neuropsychiatric PC in New York.

Some of these events are in your control, and some aren't:

Pregnancy complications. Infection, stress, and complications during pregnancy such as preeclampsia may raise the chance that your child will one day have schizophrenia. But that’s not certain.

Depression or other major stressful events during pregnancy may also play a role. "A woman who experiences a death or other tragedy during pregnancy is also more likely to have a child at risk," Samton says.

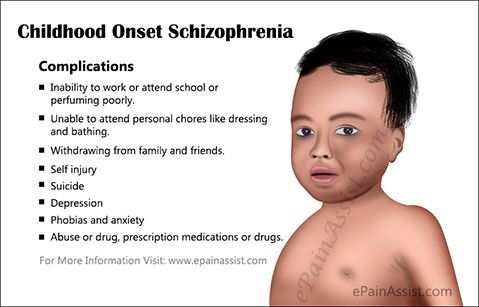

Harmful childhood experiences. Brain injury, sexual abuse, and traumatic early experiences may raise the risk.

"Children who were exposed to any trauma before age 16 were three times more likely to become psychotic," Samton says. If the trauma was severe, children were 50 times more likely.

Drug abuse. Early and long-term use of marijuana and other illicit drugs may raise the risk.

Don't use drugs. This is especially important for teens, because their brains are still developing. Remember, alcohol is a drug, so you should limit or avoid it.

Avoid abusive or traumatic situations. If you're in an abusive relationship or you're going through trauma, get help. For instance, you can call a doctor, therapist, crisis line, or 911.

Keep strong social ties. Socializing helps you maintain self-esteem, lower stress, not feel lonely, and keep busy. Teens, especially, should be encouraged to connect with friends and avoid isolation, Samton says.

Learn how to manage stress. Ongoing stress and anxiety are bad for your health.

Set up strategies to manage stress, says Cheryl Corcoran, MD, a research scientist at Columbia University's New York State Psychiatric Institute. You can do this in therapy or learn from your parents, teachers, or other role models who seem to manage stress well.

Take care of your body. Good nutrition and plenty of exercise are important.

Take steps to protect yourself from head injuries, too. For example, wear helmets when biking or playing contact sports.

Try fish oil. One study suggests that omega-3 fatty acids (found in fish oil) may help prevent psychotic disorders from getting worse, and might even prevent them in young children who are at risk of them. This isn’t certain, though.

This isn’t certain, though.

Take steps to stay well if you're pregnant or trying to get pregnant. Make sure you get good medical care for your physical and mental health.

See a psychiatrist. If you have any symptoms, such as feeling suspicious or having unusual thoughts, see a psychiatrist. Cognitive behavioral therapy (a type of counseling) may help you better spot the early signs of schizophrenia and limit its impact on your work, school, and social life. In this type of therapy, a trained psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker helps people recognize negative patterns of thought and come up with new ways of thinking about problems.

Remember, it’s not likely. Even if schizophrenia runs in your family, there’s a good chance that you won't get it. About 85% of people with a family history of schizophrenia don't develop it themselves, Corcoran says. "So along with doing all of these things, keep these numbers in mind and try not to worry. "

"

Prediction and prevention of schizophrenia: what has been achieved and where to go next?

1. Bundesministeriums für Gesundheit. Maßnahmen des Bundesministeriums für Gesundheit zur Umsetzung nationaler Gesundheitsziele. Berlin: Bundesministerium für Gesundheit; 2007. [Google Scholar]

2. Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care. Promotion, prevention and early intervention for mental health – a monograph. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care; 2000. [Google Scholar]

3. European Commission. Green Paper – Improving mental health of the population: towards a strategy on mental health for the European Union. Brussels: European Commission; 2005. [Google Scholar]

4. World Health Organization. Prevention of mental disorders: effective interventions and policy options. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

5. Häfner H, an der Heiden W. In: Clinical handbook of schizophrenia. Mueser KT, Jeste DV, editors. New York: Guilford; 2008. pp. 100–113. [Google Scholar]

pp. 100–113. [Google Scholar]

6. Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:506–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Clouth J. Costs of early retirement – the case of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Prax. 2004;31(Suppl. 2):S238–S245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Rössler W, Salize HJ, van Os J. Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15:399–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Samnaliev M, Clark RE. The economics of schizophrenia. In: Mueser KT, Jeste DV, editors. Clinical handbook of schizophrenia. New York: Guilford; 2008. pp. 507–515. [Google Scholar]

10. Gutiérrez-Maldonado J, Caqueo-Urízar A, Kavanagh D. Burden of care and general health in families of patients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:899–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Harrison PJ, Weinberger DR. Schizophrenia genes, gene expression and neuropathology on the matter of their convergence. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(Suppl. 3):40–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(Suppl. 3):40–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Seidman LJ, Giuliano AJ, Meyer EC. Neuropsychology of the prodrome to psychosis in the NAPLS consortium: relationship to family history and conversion to psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:578–588. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374:635–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Häfner H, Maurer K, Löffler W. The ABC Schizophrenia Study: a preliminary overview of the results. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:380–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Berning J. Basic symptoms and ultrahigh risk criteria: symptom development in the initial prodromal state. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:182–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J. Early detection and intervention in the initial prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(Suppl. 3):S162–S167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3):S162–S167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:975–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Klosterkötter J, Hellmich M, Steinmeyer EM. Diagnosing schizophrenia in the initial prodromal phase. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:158–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Huber G, Gross G. The concept of basic symptoms in schizophrenic and schizoaffective psychoses. Recent Prog Med. 1989;80:646–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Gross G. The ‘basic’ symptoms of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;7:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Gross G, Huber G, Klosterkötter J. Bonner Skala für die Beurteilung von Basissymptomen (BSABS; Bonn Scale for the Assessment of Basic Symptoms) Berlin: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

22. Schultze-Lutter F, Addington J, Ruhrmann S. Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, Adult version (SPI-A) Rome: Fioriti; 2007. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

23. Schultze-Lutter F, Koch E. Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, Child & Youth version (SPI-CY) Rome: Fioriti; 2010. [Google Scholar]

24. Schultze-Lutter F, Steinmeyer EM, Ruhrmann S. The dimensional structure of self-reported ‘prodromal’ disturbances in schizophrenia. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2008;5:140–150. [Google Scholar]

25. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Klosterkötter J. Evolving psychosis. In: Johannessen JO, Martindale B, Cullberg J, editors. Different stages, different treatments. London: Routledge; 2006. pp. 104–123. [Google Scholar]

26. Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J, Picker H. Predicting first-episode psychosis by basic symptom criteria. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2007;4:11–22. [Google Scholar]

27. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, McGorry PD. Prediction of psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172(Suppl. 33):14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Phillips LJ, Yung AR, McGorry PD. Identification of young people at risk of psychosis: validation of personal assessment and crisis evaluation clinic intake criteria. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:S164–S169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:S164–S169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:964–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL. Prospective diagnosis of the initial prodrome for schizophrenia based on the structured interview for prodromal syndromes: preliminary evidence of interrater reliability and predictive validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:863–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. McGlashan T, Walsh B, Woods S, editors. The psychosis-risk syndrome. Handbook for diagnosis and follow-up. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

32. Cornblatt B. The New York High-Risk Project to the Hillside Recognition and Prevention (RAP) Program. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114:956–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Riecher-Rössler A, Geschwandtner U, Aston J. The Basel early-detection-of-psychosis (FEPSY)-study – design and preliminary results. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115:114–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115:114–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Yung AR, Stanford C, Cosgrave E. Testing the ultra high risk (prodromal) criteria for the prediction of psychosis in a clinical sample of young people. Schizophr Res. 2006;84:57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Yung AR, Nelson B, Stanford C. Validation of “prodromal” criteria to detect individuals at ultra high risk of psychosis: 2 year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2008;105:10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Woods SW, Addington J, Cadenhead KS. Validity of the prodromal risk syndrome for first psychosis: findings from the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:894–908. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Lencz T, Smith CW, Auther A. The assessment of “prodromal schizophrenia”: unresolved issues and future directions. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:717–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Mason O, Startup M, Halpin S. Risk factors for transition to first episode psychosis among individuals with ‘at-risk mental states’ Schizophr Res. 2004;71:227–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2004;71:227–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Salokangas RK. Prediction of psychosis in adolescents and young adults at high risk: results from the prospective European Prediction of Psychosis Study (EPOS). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:241–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C. Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: findings from the 3-center AESOP study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:250–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ, editors. Reducing risks for mental disorders: frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington: National Academy Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

Reducing risks for mental disorders: frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington: National Academy Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

44. McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first-episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:921–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, Yuen HP. Medium-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra high risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2007;96:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Morrison AP, French P, Walford L. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra-high risk. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:291–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Morrison AP, French P, Parker S. Three-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultrahigh risk. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:682–687. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:682–687. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D. The PRIME North America randomized double-blind clinical trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients at risk of being prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. I. Study rationale and design. Schizophr Res. 2003;61:7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Häfner H, Maurer K, Ruhrmann S. Early detection and secondary prevention of psychosis: facts and visions. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:117–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Bechdolf A, Wagner M, Harrigan S. Preventing progression to first-episode psychosis in early initial prodromal states. Br J Psychiatry. in press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Maier W. Pharmacological intervention in the initial prodromal phase of psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Bechdolf A, Müller H, Stützer H. Rationale and baseline characteristics of PREVENT: a second generation intervention trial in subjects at-risk (prodromal) of developing first episode psychosis evaluating cognitive behaviour therapy, aripiprazole and placebo for the prevention of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schizophr Bull. in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Woods SW, Tully EM, Walsh BC. Aripiprazole in the treatment of the psychosis prodrome. An open-label pilot study. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191(Suppl. 51):96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Smith CW. Can antidepressants be used to treat the schizophrenia prodrome? Results of a prospective, naturalistic treatment study of adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:546–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Hampel H, Frank R, Broich K. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: academic, industry and regulatory perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:560–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Borgwardt SJ, McGuire PK, Aston J. Structural brain abnormalities in individuals with an at-risk mental state who later develop psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191(Suppl. 51):69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Brockhaus-Dumke A, Schultze-Lutter F, Mueller R. Sensory gating in schizophrenia: P50 and N100 gating in antipsychotic-free subjects at risk, first-episode, and chronic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:376–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:376–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, Wood SJ. Neuroimaging and emerging psychotic disorders: the Melbourne ultra-high risk studies. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19:371–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Pukrop R, Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S. Neurocognitive functioning in subjects at risk for a first episode of psychosis compared with first- and multiple-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychiatry. 2006;28:1388–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Witthaus H, Kaufmann C, Bohner G. Gray matter abnormalities in subjects at ultra-high risk for schizophrenia and first-episode schizophrenic patients compared to healthy controls. Psychiatry Res. 2008;173:163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. The European Network of Schizophrenia Networks for the Study of Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) Schizophrenia aetiology: do gene-environment interactions hold the key? Schizophr Res. 2008;102:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J. Probably at-risk, but certainly ill - Advocating the introduction of a psychosis spectrum disorder in DSM-V. Schizophr Res. 2010;120:23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J. Probably at-risk, but certainly ill - Advocating the introduction of a psychosis spectrum disorder in DSM-V. Schizophr Res. 2010;120:23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Lieberman JA. Neuroprotection: a new strategy in the treatment of schizophrenia. Neurobiological basis of neurodegeneration and neuroprotection. CNS Spectr. 2007;12(Suppl. 18):4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Berger G, Dell’Olio M, Amminger P. Neuroprotection in emerging psychotic disorders. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2007;1:114–127. [Google Scholar]

65. Amminger GP, Schäfer MR, Papageorgiou K. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:146–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Woods SW, Walsh B, Pearlson GD. Glycine treatment of prodromal symptoms. Schizophr Res. 2006;86:S7–S17. [Google Scholar]

67. Berger G, Wood SJ, Dell’Olio M. Neuroprotective effects of low dose lithium in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis. A longitudinal MRI/MRS study. Schizophr Res. 2008;102:39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A longitudinal MRI/MRS study. Schizophr Res. 2008;102:39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Nelson B, McGorry P, Yung A. The NEURAPRO (North America, Europe, Australia Prodrome) Study: a multicenter RCT of treatment strategies for symptomatic patients at ultra-high risk for progression to schizophrenia and related disorders. Design and study plan. Schizophr Res. 2008;102(Suppl. 2):295–295. [Google Scholar]

Prevention of schizophrenia

There is no doubt that the prevention of schizophrenia is based on knowledge of the etiology and pathogenesis of this mental disorder.

Based on our knowledge of the etiology of schizophrenia, persons with a hereditary burden of this disease should be included in the risk group for its occurrence. At the same time, the latter circumstance is not a cause for unnecessary concern. Only the impact of environmental factors can activate a hereditary predisposition to schizophrenia.

An important etiological factor in schizophrenia is brain damage at an early stage of ontogenesis. As a result of the foregoing, proper care for health, nutrition, positive emotional support for a pregnant woman are considered the main factors in the formation of a healthy child. Poor nutrition, stress, environmental disasters, depression during pregnancy due to the undesirability of having a baby also increase the vulnerability of the central nervous system in the process of fetal development.

As a result of the foregoing, proper care for health, nutrition, positive emotional support for a pregnant woman are considered the main factors in the formation of a healthy child. Poor nutrition, stress, environmental disasters, depression during pregnancy due to the undesirability of having a baby also increase the vulnerability of the central nervous system in the process of fetal development.

If there is a family history of schizophrenia, pregnancy planning is recommended at least three months in advance. Before pregnancy, you need to make sure that all sexually transmitted diseases, especially herpes and chlamydia, are cured. It is important to have a normal weight before pregnancy. Alcohol intake and smoking should be excluded during pregnancy.

Brain damage at an early stage of ontogenesis is more likely if a child is born in the winter season, if the family lives in the city. Infectious diseases that appear at 5-7 months of pregnancy, especially influenza, rubella and poliomyelitis, negatively affect the development of the fetal brain.

Obstetrical factors that contribute to susceptibility to schizophrenia include Rh incompatibility, hypoxia, birth trauma, low birth weight, and preeclampsia. These factors are especially relevant for people with hereditary burden of schizophrenia.

For adolescents at risk for schizophrenia, avoiding drug and alcohol use is important. They should continually strive to develop their social skills, avoid social isolation, and form good relationships with adults. Make efforts to perceive life in a positive way. It is recommended to conduct special trainings aimed at the formation of adequate psychological mechanisms for dealing with stress and depression. In the families of a person with schizophrenia, it is important to build stable and calm relationships, without excessive emotional expression (shouting, arguing, etc.), physical violence, excessively dependent or uncontrolled behavior, and to form conflict resolution skills.

In case of detecting distinct manifestations of negative symptoms, cognitive impairment in adolescence, some psychiatrists recommend short-term administration of atypical antipsychotics in small doses for prophylactic purposes.

For schizophrenia, as for any mental disorder, the following “positive steps” are considered important elements of prevention: self-acceptance, physical activity, stress management, reduced alcohol consumption, the opportunity to “talk out”, the acquisition of new skills, creative and spiritual activity, participation in the life of the community, strong friendships and social ties, the ability to find those who can help (Jenkins R. et al., 2005).

Back to Contents

Clinical Clinical Hospital No. 5 - Schizophrenia

State Budgetary Healthcare Institution of the City of Moscow

Psychiatric Clinical Hospital No. 5 of the Department of Health of the City of Moscow

+7 (495-245) (496) 724-33-33

Moscow region, Chekhov, s. Troitskoye, 5

Medical Tourism

Site search

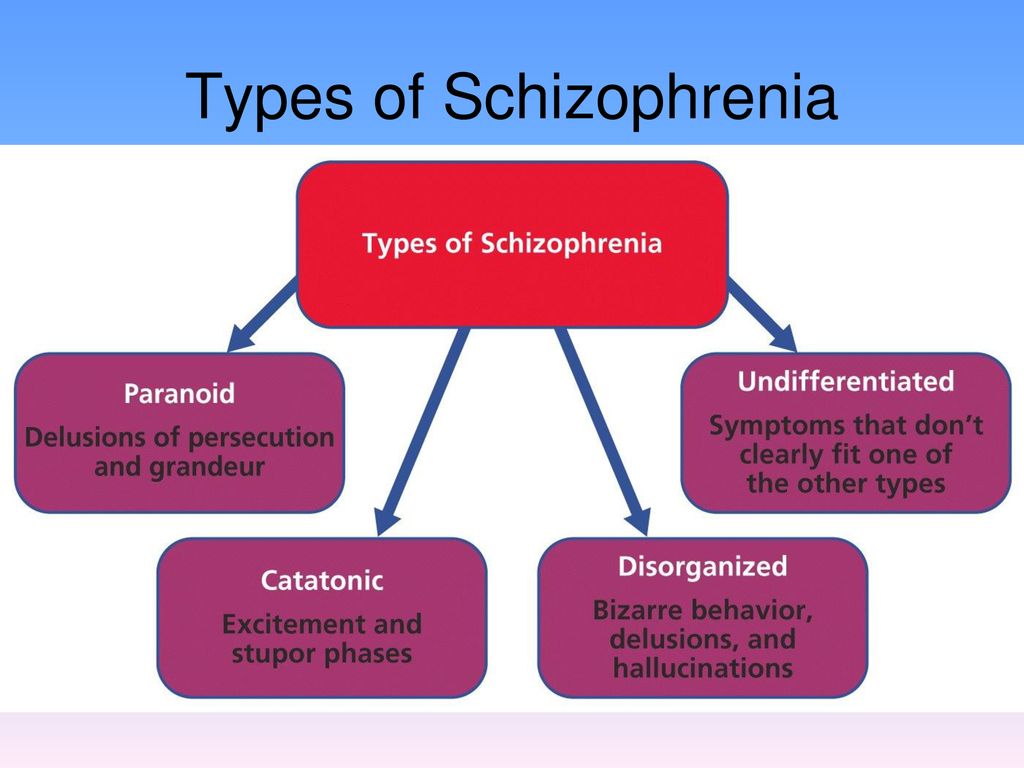

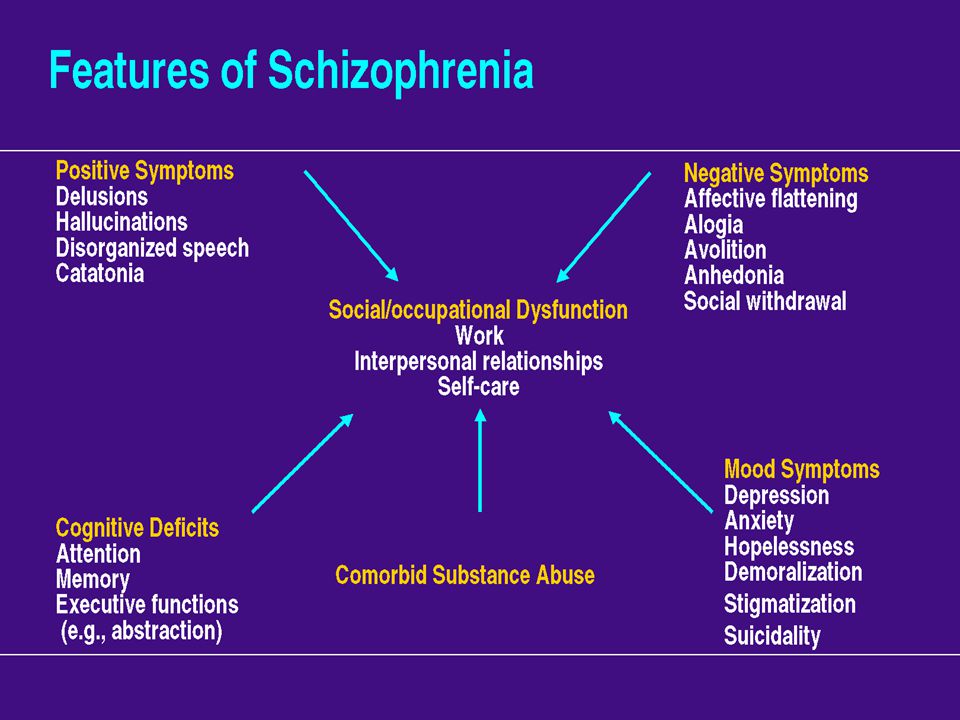

Schizophrenia is a chronic mental illness, which is characterized by a violation of the unity of thought processes, with a relatively intact intellect, which is combined with significant emotional impoverishment and a decrease in will. Often hallucinatory and delusional disorders join.

Often hallucinatory and delusional disorders join.

The term "schizophrenia" itself is made up of two Greek words - "schizo" - I split and "freni" - the mind of reason.

The term was first used by the Swiss psychiatrist Eigen Bleuler in 1908. Schizophrenia, of course, existed before, but only by the beginning of the 20th century did the idea of it as a special kind of psychosis mature.

In the mass consciousness, there is an unreasonable identification of schizophrenia with a "split personality" - that is, in fact, with a very rare mental disorder in which different "I"s are alternately activated in one person.

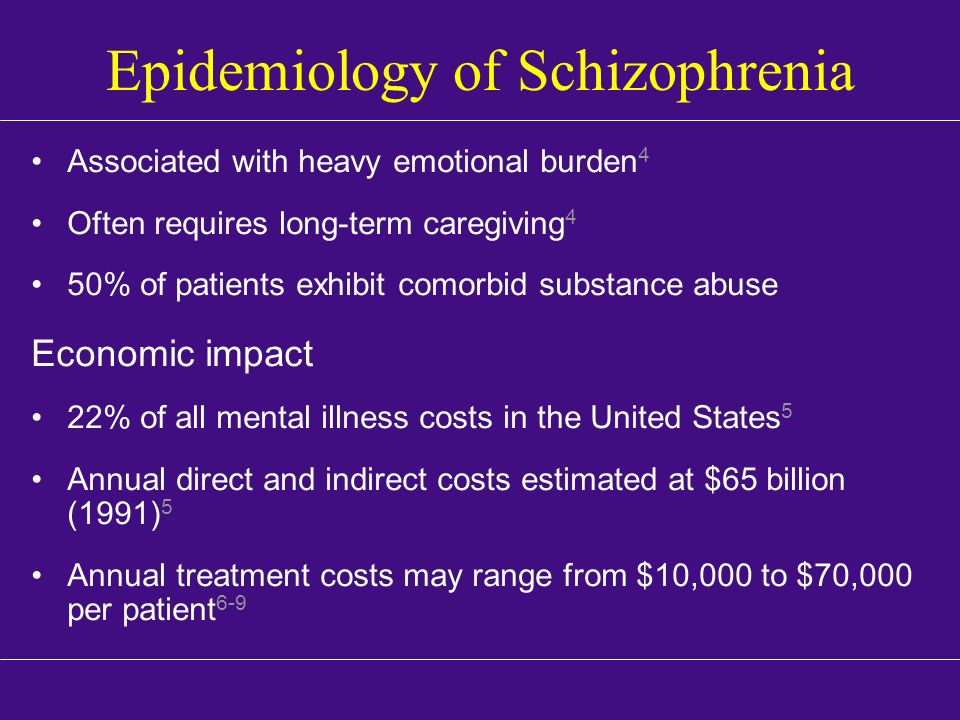

Schizophrenia, unfortunately, is quite common. Its prevalence among the Russian population is 35 per 10,000 people, with no significant difference between the sexes. Thus, in Russia there are at least half a million patients with this serious pathology.

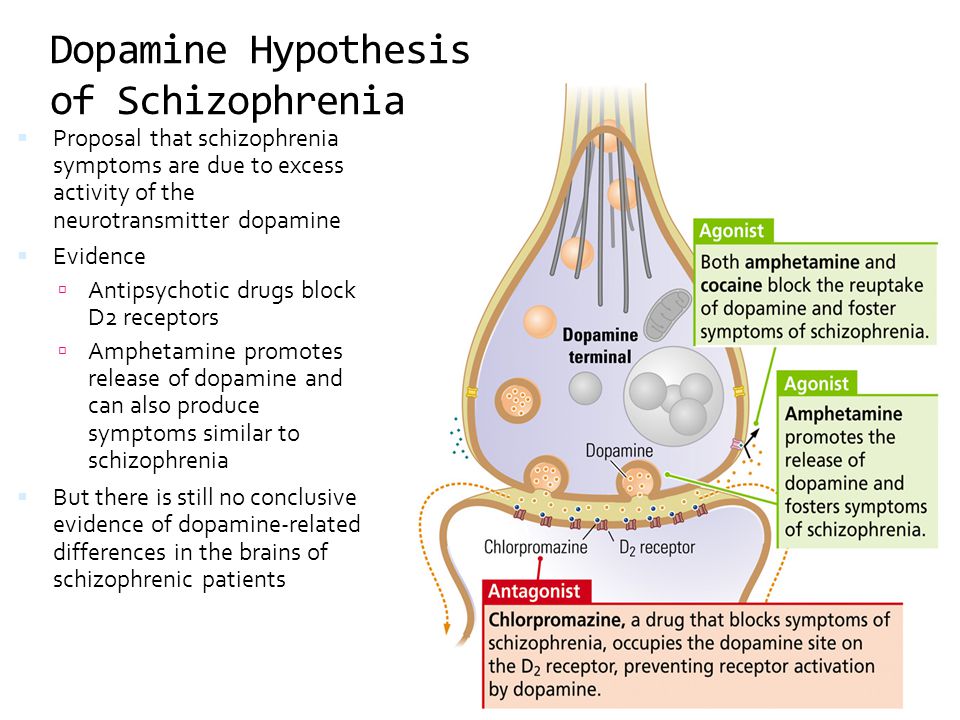

Schizophrenia refers to endogenous mental illness, which means that it is an internal breakdown of the psyche. It cannot be caused by any factors acting on the brain from the outside (trauma, intoxication, severe stress). Of course, these factors can affect the rate of development of schizophrenia, but not its occurrence. However, the mechanism of development of the schizophrenic process has not yet been established with certainty. There are several hypotheses about this. Thus, there is evidence of a relationship between schizophrenia and a violation of the distribution of dopamine in the central nervous system.

It cannot be caused by any factors acting on the brain from the outside (trauma, intoxication, severe stress). Of course, these factors can affect the rate of development of schizophrenia, but not its occurrence. However, the mechanism of development of the schizophrenic process has not yet been established with certainty. There are several hypotheses about this. Thus, there is evidence of a relationship between schizophrenia and a violation of the distribution of dopamine in the central nervous system.

The role of heredity is very important. So, if one of the twins fell ill with schizophrenia, then the risk of getting sick for the other twin is 17% in a fraternal couple and 48% in an identical one. However, it is believed that in half of the cases of schizophrenia arises from a random mutation, that is, on the basis of genetic changes that were absent in the parents and appeared after conception.

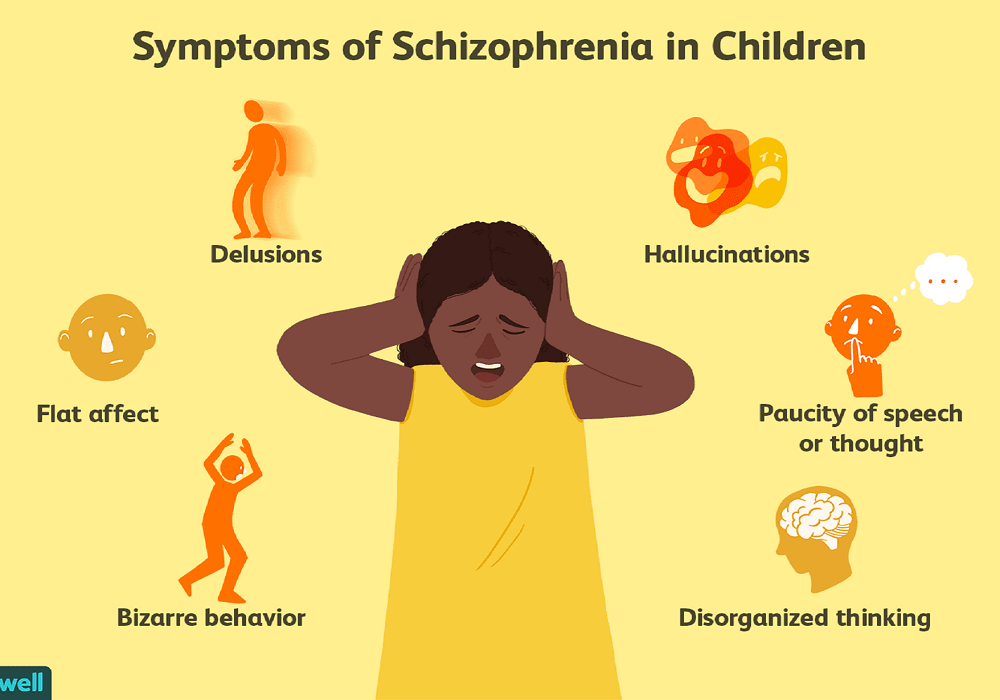

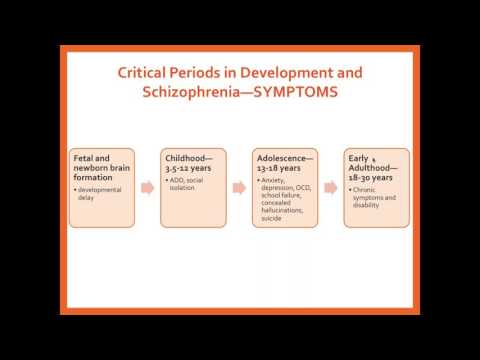

Symptoms can develop at any age (possibly even in utero), but usually its onset is timed to coincide with the third pubertal crisis, that is, by the age of 12-18 years or several years later (up to about 30 years).

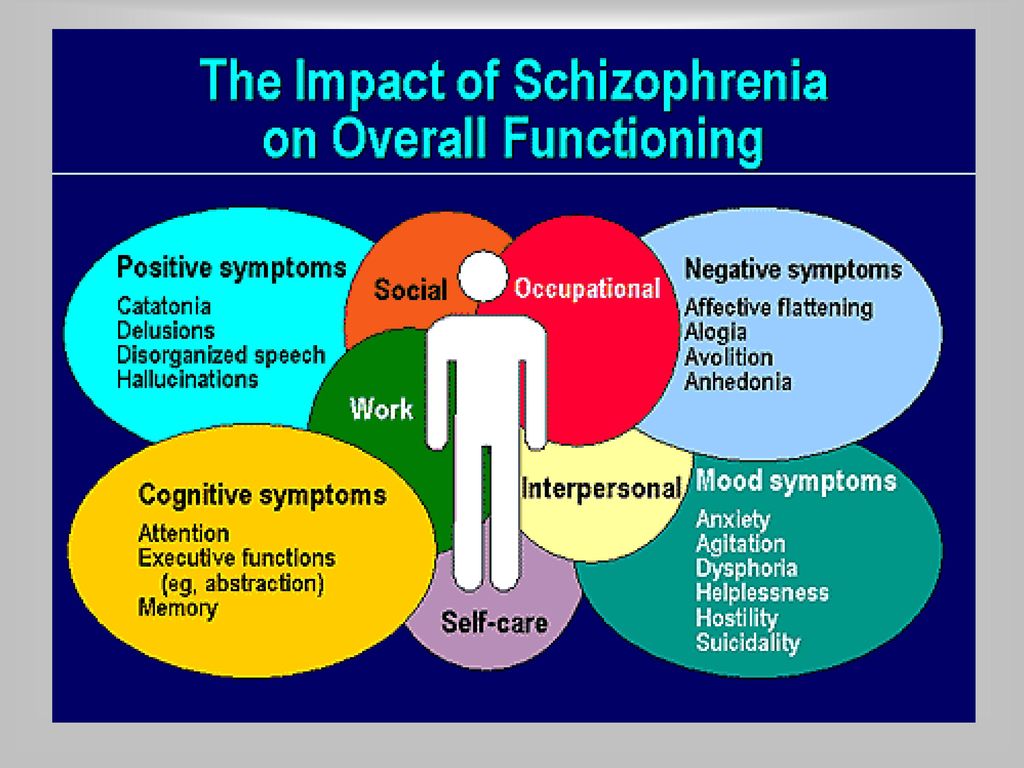

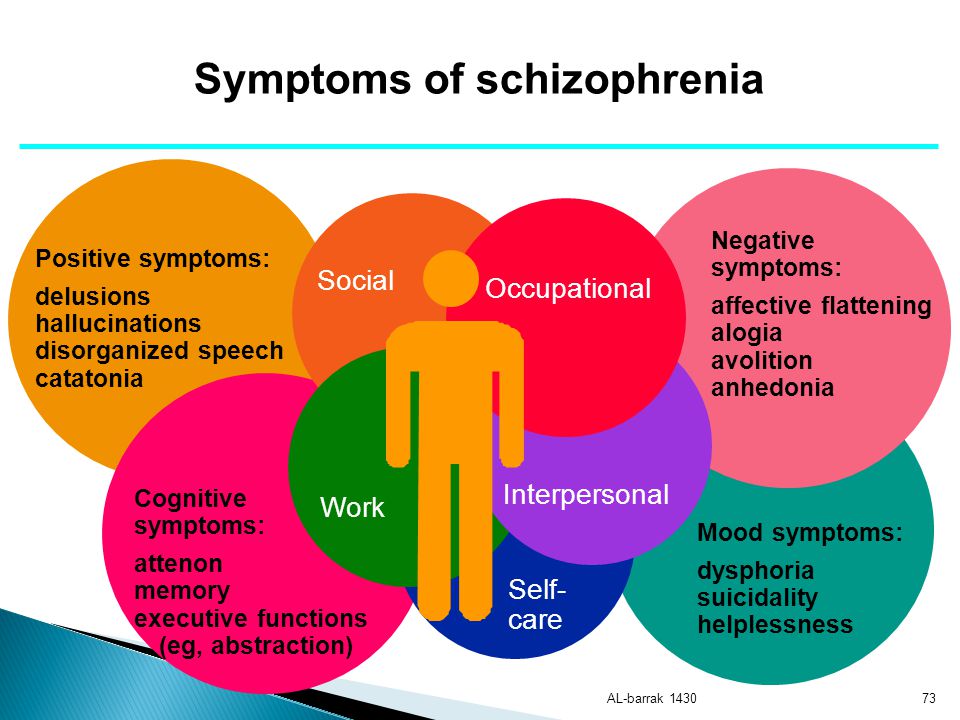

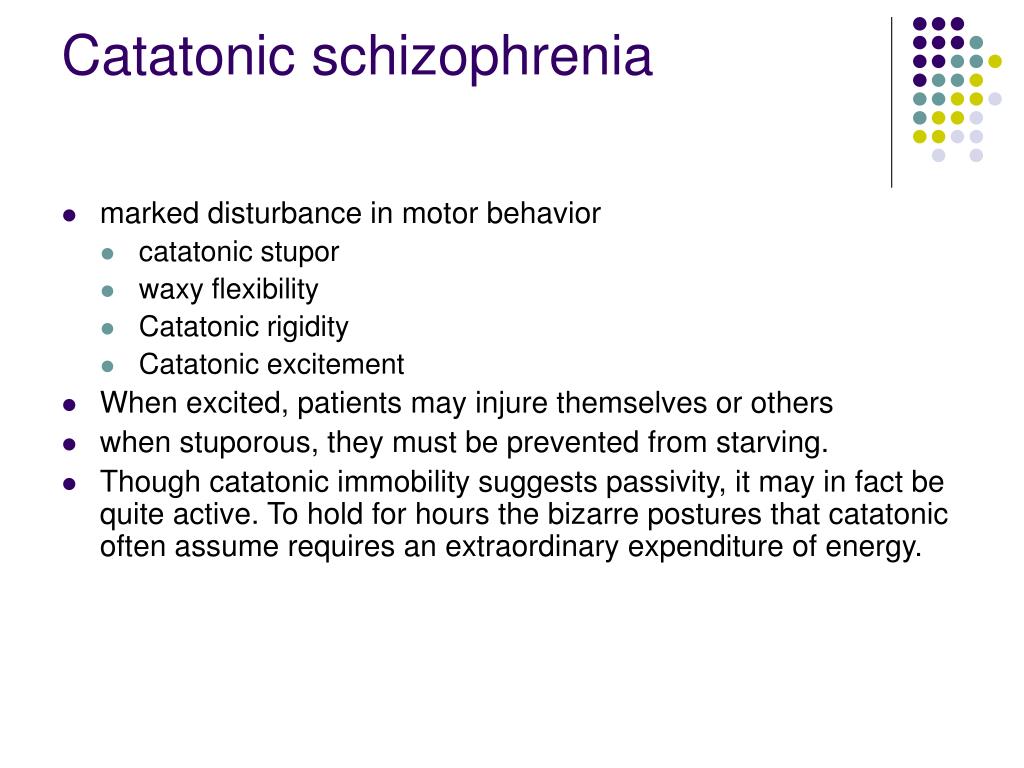

Most often, the disease begins with negative symptoms associated with the loss of normal functioning - a person changes in character for no apparent reason, becomes closed, fenced off, loses social contacts, emotional warmth in relation to relatives disappears. Former interests disappear, school or university performance drops sharply, or official duties are not fulfilled. Thus, from the very beginning of clinical manifestations there is a very high risk of disability. In the most unfavorable variant, which is designated as simple schizophrenia, the patient can lie for days on end, staring at the ceiling, and with a clear mind and normal physical strength, he is not able to simply serve himself. Even with more favorable options, thinking disorders increase, which are expressed in the influx of thoughts or in the feeling that there are no thoughts at all. Reasoning becomes unproductive, unfocused, an ambivalent attitude to life phenomena (ambivalence) is formed. Speech is distinguished by ornateness, sometimes with neologisms that the patient himself comes up with. During the conversation, there are distractions from his topic (sliding), and not to specific details and circumstances, but to the “bad” attitude of certain characters towards the patient, or to global philosophical topics. People with schizophrenia tend to be somewhat cynical about many aspects of their environment.

During the conversation, there are distractions from his topic (sliding), and not to specific details and circumstances, but to the “bad” attitude of certain characters towards the patient, or to global philosophical topics. People with schizophrenia tend to be somewhat cynical about many aspects of their environment.

Patients have a painful feeling that everything around is somehow changed, devoid of naturalness, harmony (- derealization), the same feelings can arise in relation to their personality (- depersonalization). With depersonalization, the consciousness (but not the personality!) seems to split in two: one part of it looks at what is happening from the side, and the other is horrified by the realization of the loss of control over oneself.

One's own thoughts and ideas begin to be perceived as alien. According to modern views, this is why schizophrenia causes verbal hallucinations (“voices”), and it is not surprising that the sound of “voices” inside the head is typical for this disease. For the same reason, it seems to the patient that someone controls him from the outside, up to the control of movements and the work of internal organs. Visions are less common.

For the same reason, it seems to the patient that someone controls him from the outside, up to the control of movements and the work of internal organs. Visions are less common.

Such a growing wave of unusual sensations is very painful. In many cases, internal tension is somewhat relieved by the formation of delusional ideas (quickly - like an insight - the crystallization of delirium occurs). It suddenly becomes “clear” to the patient that what is happening to him is, for example, the “intrigues” of some “organization”, which, with the help of modern equipment, “influences” him from the outside (delusions of persecution, influence). There is also delusions of jealousy, damage. It is clear that the plot of experiences is influenced by the level of development of society, including the plots of popular works of literature and cinema.

This whole clinical picture often develops acutely, in the form of an attack that lasts from several days to several months, and then may recur. Attack-like forms of schizophrenia are more favorable, in terms of prognosis, than continuous ones. The intervals between attacks are very long (sometimes - tens of years), and between them the person looks almost the same as before, before the illness. But this is rather an exception. Much more often, exacerbations of symptoms are repeated annually or several times a year, and after each new attack, it turns out that the will has become even weaker and emotions have faded even more. Gradually, over many years, hallucinatory experiences become less relevant. Parallel, but also very slowly, delirium is falling apart as a system of pseudo-logical conclusions - separate fragments of delirium remain. As a result, a state of defect develops, which resembles simple schizophrenia.

Attack-like forms of schizophrenia are more favorable, in terms of prognosis, than continuous ones. The intervals between attacks are very long (sometimes - tens of years), and between them the person looks almost the same as before, before the illness. But this is rather an exception. Much more often, exacerbations of symptoms are repeated annually or several times a year, and after each new attack, it turns out that the will has become even weaker and emotions have faded even more. Gradually, over many years, hallucinatory experiences become less relevant. Parallel, but also very slowly, delirium is falling apart as a system of pseudo-logical conclusions - separate fragments of delirium remain. As a result, a state of defect develops, which resembles simple schizophrenia.

Patients either do not recognize themselves as ill or have conflicting thoughts about it. As a rule, they negatively meet the persuasion of relatives about the need to contact a psychiatrist. There are attempts to alleviate their condition with alcohol and drugs, which only complicates the clinical picture and leads to further social maladaptation.

Under the influence of orders "voices" and against the background of delusional experiences, the risk of socially dangerous actions of patients increases. For example, cases of attacks on imaginary "persecutors" are known. But much more often, patients with endogenous mental pathology commit OOD through other mechanisms, including when their behavior is influenced by alcohol or drug intoxication, which is superimposed on negative symptoms.

Schizophrenia is the most common disease among patients in the Clinical Hospital No. 5 in Moscow.

Common diagnosis: Paranoid schizophrenia, episodic type of course with progressive defect, incomplete remission. The clinical picture with this diagnosis includes delusions and hallucinations (usually delusions of persecution and verbal hallucinations - "voices").

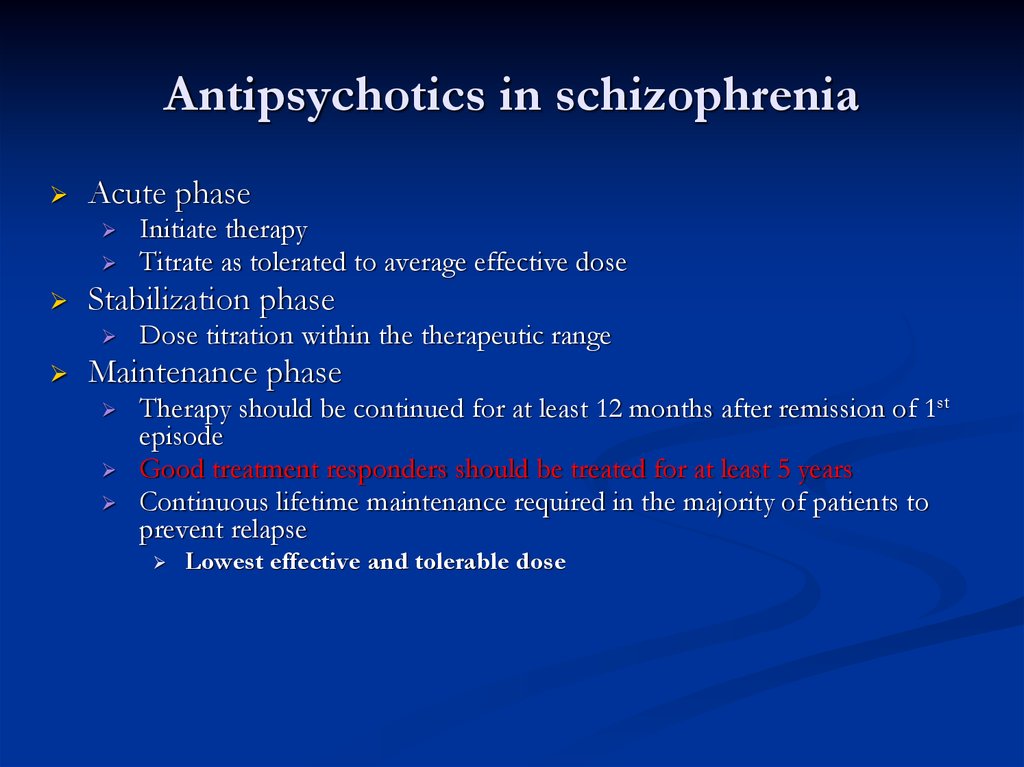

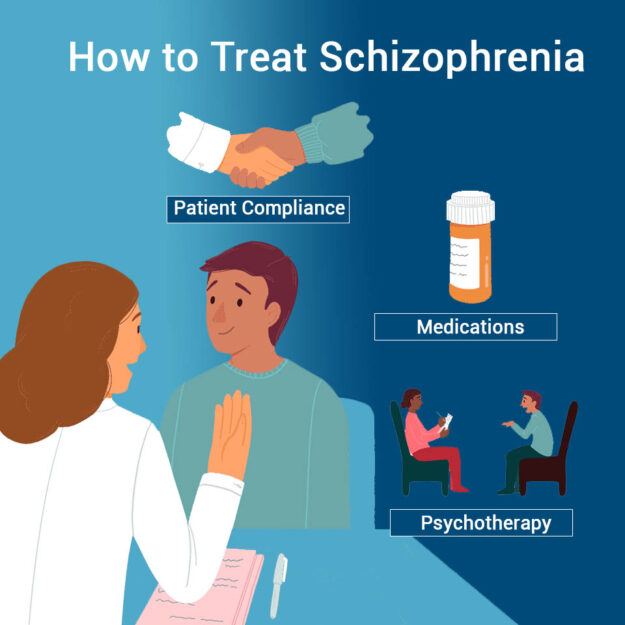

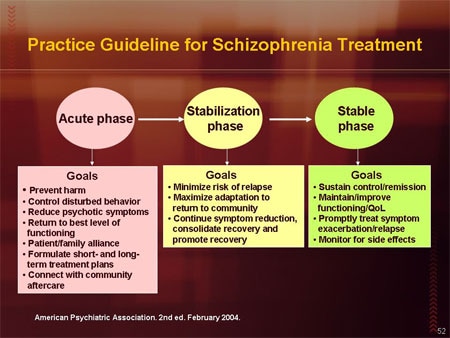

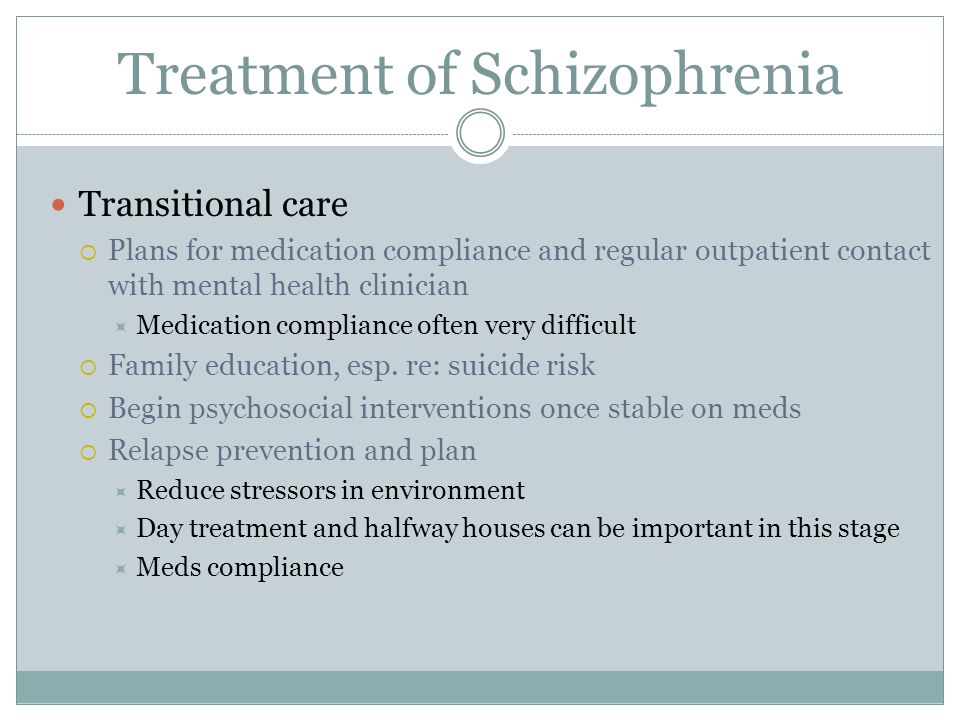

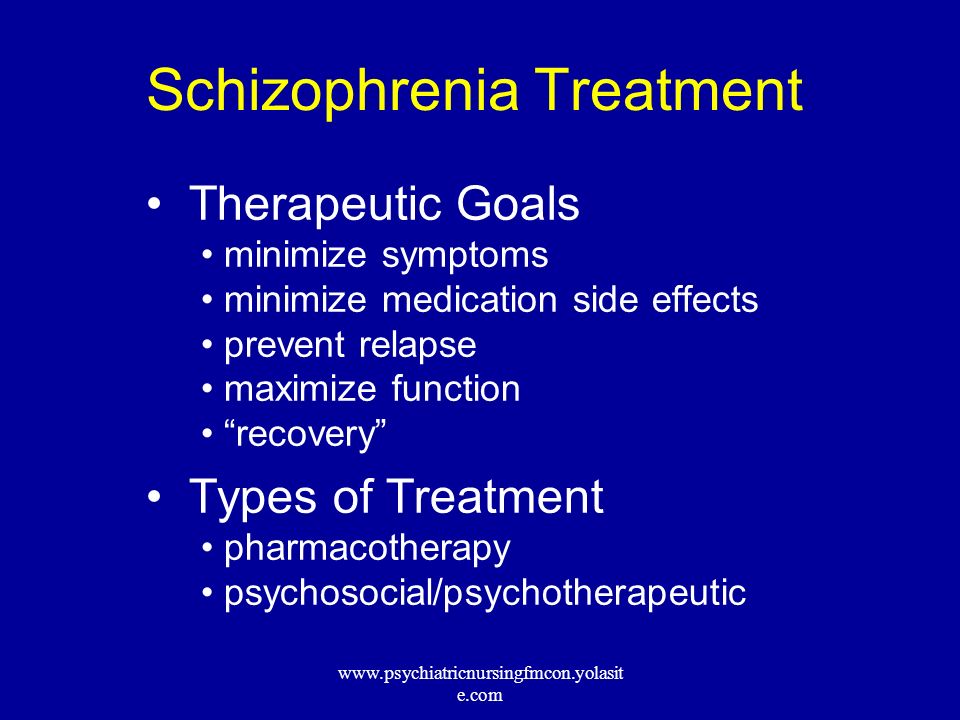

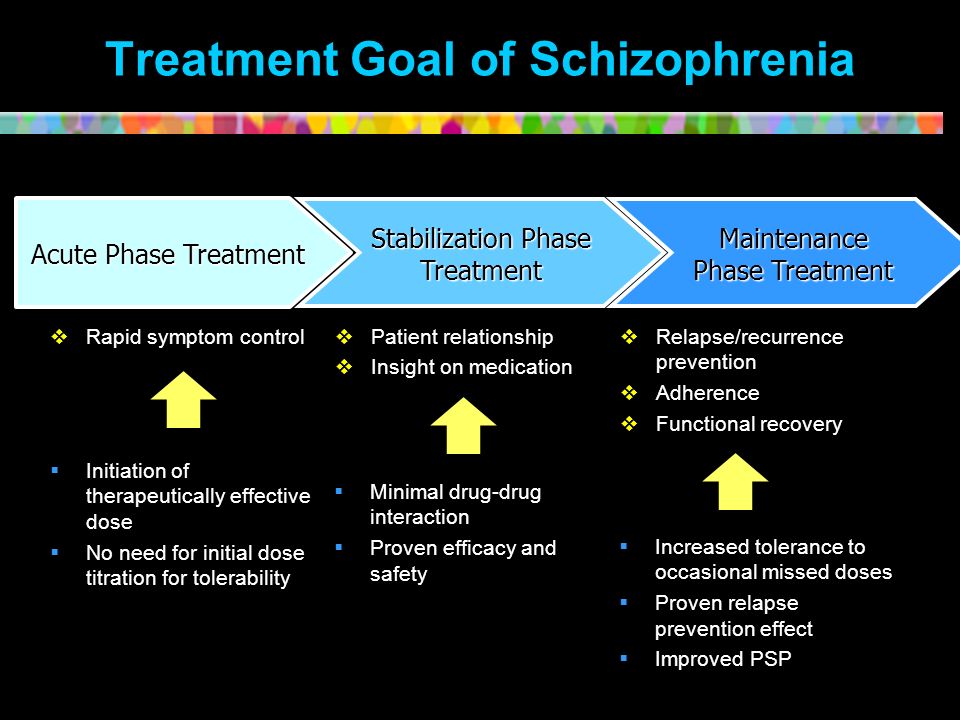

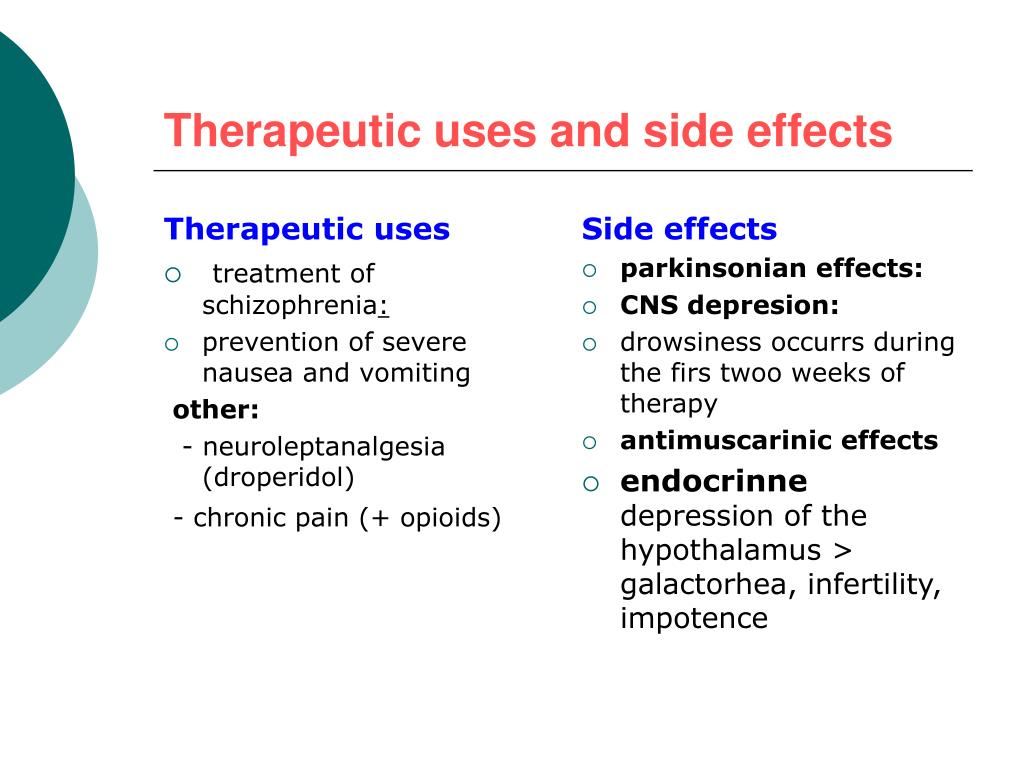

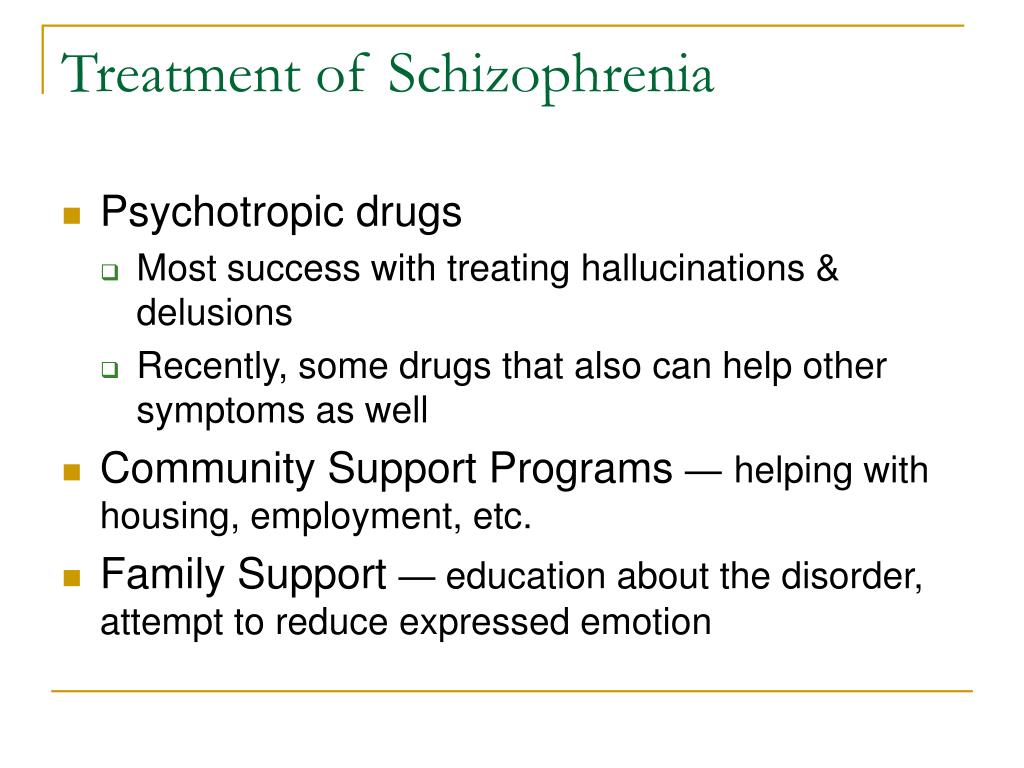

Treatment of schizophrenia includes antipsychotics, antidepressants, nootropics. The leading role belongs to antipsychotics, the action of which is aimed primarily at combating delusions and hallucinations. Against the background of treatment, at first, as a rule, the patient's affective reaction to his own experiences is dulled - he becomes calmer, psychomotor agitation passes. Then the hallucinations decrease in intensity or completely disappear. All these positive changes become noticeable already in the first days of the use of neuroleptics. But the plot (that is, the plot) of delirium can linger for a long time, although in the picture of internal experiences it fades significantly in relevance. After the relief of acute symptoms, the task comes to the fore: how to reduce negative symptoms and eliminate psychopathic (that is, as in psychopathy) behavioral disorders. This is helped by neuroleptics of the latest generations, such as olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone. Already at this stage, it is worth thinking about the rehabilitation of the patient. Contrary to the earlier opinion, psychotherapy is indicated for these patients, and it helps to strengthen remission and resocialization.

Against the background of treatment, at first, as a rule, the patient's affective reaction to his own experiences is dulled - he becomes calmer, psychomotor agitation passes. Then the hallucinations decrease in intensity or completely disappear. All these positive changes become noticeable already in the first days of the use of neuroleptics. But the plot (that is, the plot) of delirium can linger for a long time, although in the picture of internal experiences it fades significantly in relevance. After the relief of acute symptoms, the task comes to the fore: how to reduce negative symptoms and eliminate psychopathic (that is, as in psychopathy) behavioral disorders. This is helped by neuroleptics of the latest generations, such as olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone. Already at this stage, it is worth thinking about the rehabilitation of the patient. Contrary to the earlier opinion, psychotherapy is indicated for these patients, and it helps to strengthen remission and resocialization.