Not extrovert or introvert

Neither Introvert Nor Extrovert? You Need A Break Too

It is well-established that introverts need quiet breaks so that they can recharge their batteries in solitude. And extroverts equally need social breaks to fill up their emotional tanks. But what about ambiverts? What kind of breaks do they take? If introverts and extroverts get to recharge, isn’t it fair that ambiverts get the chance too?

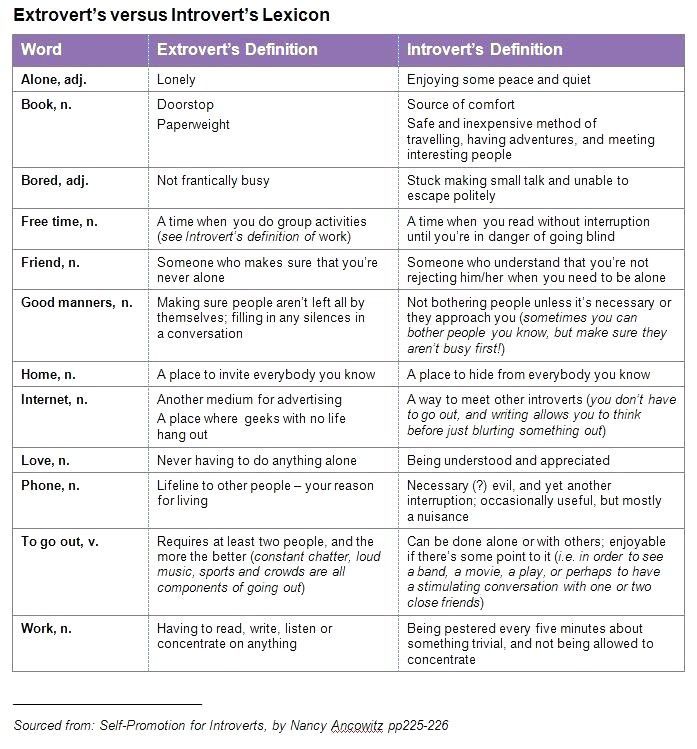

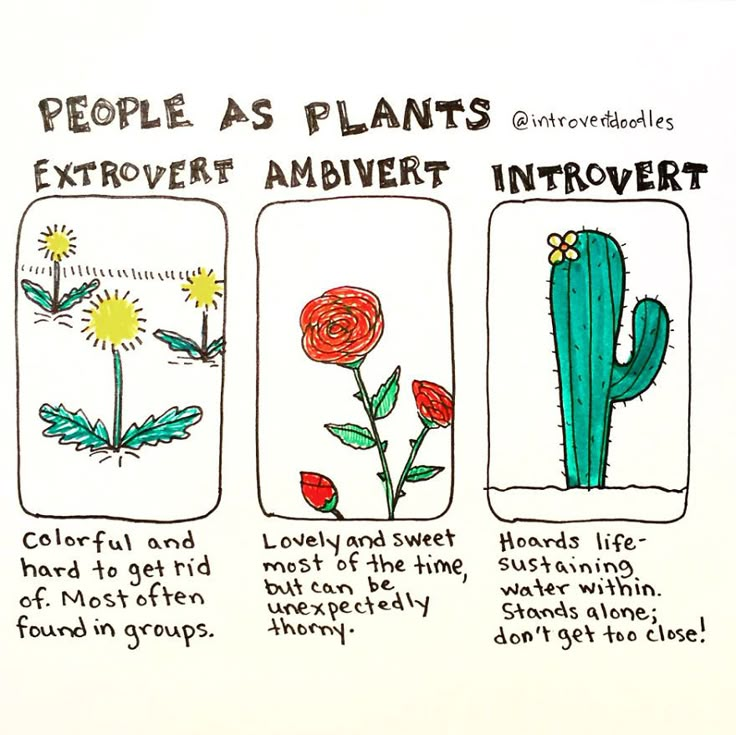

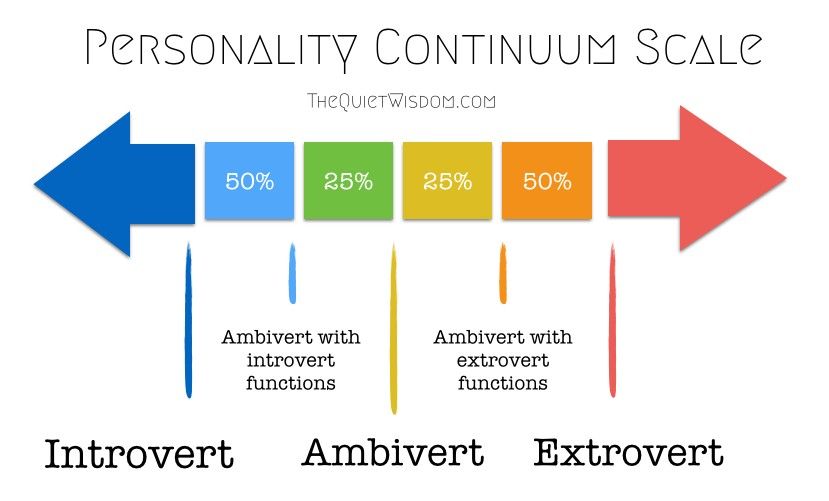

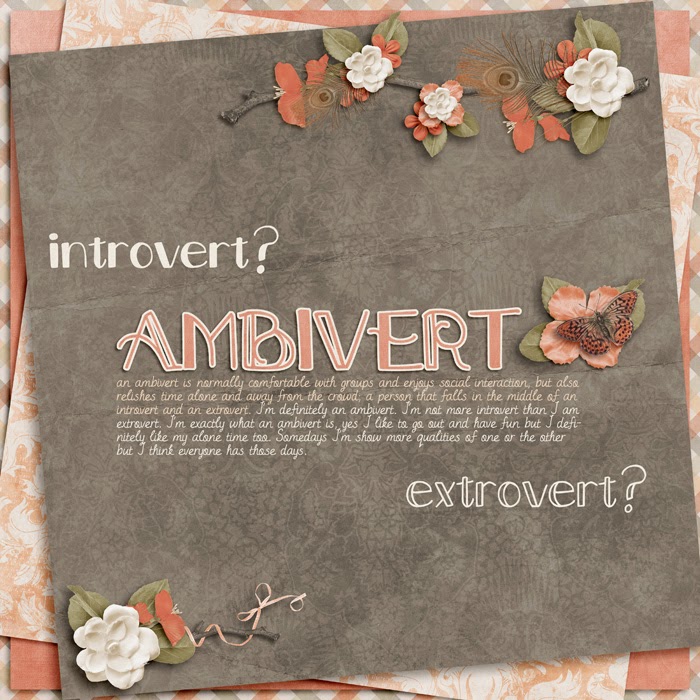

Ambiverts, for those not familiar with the term, are people that fit into a category between introverts and extroverts on the introversion to extroversion continuum. A defining characteristic is that they are capable of manifesting both types of behaviour, depending on what the task they have at hand requires of them. So, they have the strengths of both introverts and extroverts. When I first heard about ambiverts, I felt that this was a bit unfair. I was under the impression that they had the best of both worlds, and as such that they were simply better people than my fellow extroverts or introverts.

Yet, nothing is so black and white.

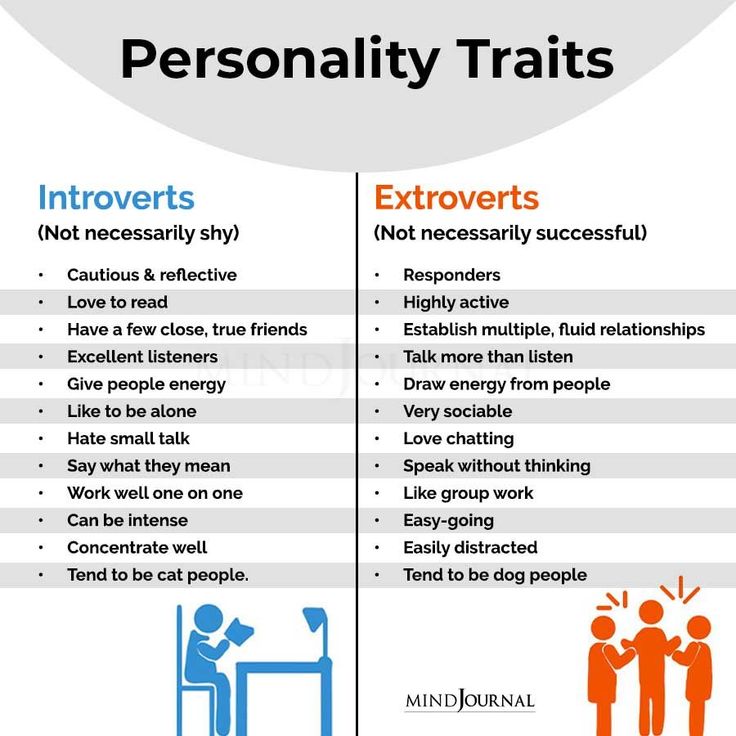

I interviewed more than 50 ambiverts to try and learn about the weaknesses that came with such an adaptable personality type. Based on this research, I believe that I can establish two weaknesses. First, ambiverts often confuse other people with their changing levels of engagement. It is hard to gauge intent and intimacy when someone sometimes acts on the more reclusive tendencies of an introvert, and other times displays the energetic connections that come with the personality traits of an extrovert. It is as though they are chameleons, making it difficult to predict how they are going to act. Many people, understandably, find this perplexing. The other weakness, and this is not really a material weakness, is that ambiverts don’t manifest the strengths of introversion or extroversion to the degree that strong introverts or extroverts do. They may present the same patterns of engagement, but it can be far less pronounced than those on either end of the continuum.

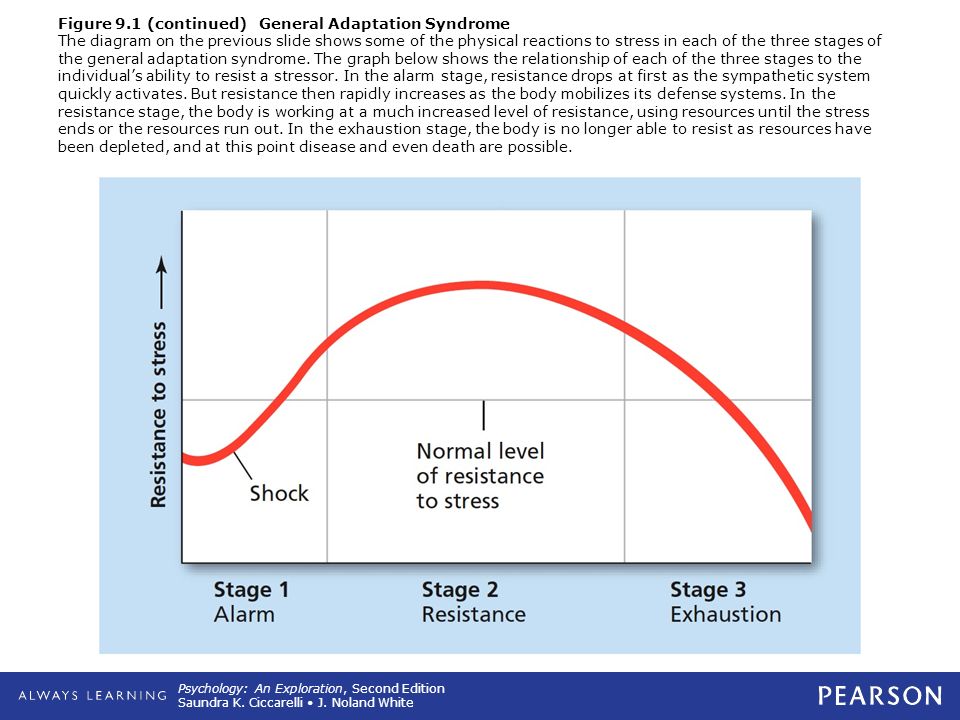

From our interviews, it seems fairly clear that the kind of breaks ambiverts take are a result of having overused one end of the continuum, enticing them to swing back to the other side of the pendulum in an effort to find balance. That is, when an ambivert has acted like an introvert for some time, they need to recharge their social batteries by taking what we would typically describe as an extrovert break. After being alone, they crave social stimulation. On the other end, when they have acted like an extrovert for some length of time, they may need to take an introvert break. Instead of talking and connecting, they may feel the need to have quiet time by themselves to recharge. Interestingly enough, our informants suggest that the length of the break would typically be less than that which the introvert or the extrovert may need to recharge. Ambiverts return to stasis more rapidly.

So, if you happen to manage an ambivert, recognize that breaks are useful to make up for the overuse of one side of their personality. Chances are, after a long time of acting like an introvert or an extrovert, they could need a moment to rebalance. While it may well be different than what you do as an introvert or extrovert, it makes perfectly good sense.

Chances are, after a long time of acting like an introvert or an extrovert, they could need a moment to rebalance. While it may well be different than what you do as an introvert or extrovert, it makes perfectly good sense.

This article was first published by The Globe and Mail.

Are You an Ambivert? Signs You're Not Introvert or Extrovert

Every editorial product is independently selected, though we may be compensated or receive an affiliate commission if you buy something through our links. Ratings and prices are accurate and items are in stock as of time of publication.

Ambiverts fall between introverts and extroverts, and that comes with advantages—and some disadvantages as well.

What is an ambivert?

You probably know what extroverts and introverts are, but there’s a third type of personality: the ambivert. Think of ambiverts as a mix between the two—they’re not as outgoing as extroverts or as quiet as introverts.

“When you look at the continuum from introversion to extroversion, it looks like a curve and bulges in the middle,” says Laurie Helgoe, PhD, a clinical psychologist and the author of Introvert Power: Why Your Inner Life Is Your Hidden Strength. “Most people live in the middle, and the ones who really don’t seem to lean over one side or the other and kind of draw from both orientations are considered ambiverts.”

“Most people live in the middle, and the ones who really don’t seem to lean over one side or the other and kind of draw from both orientations are considered ambiverts.”

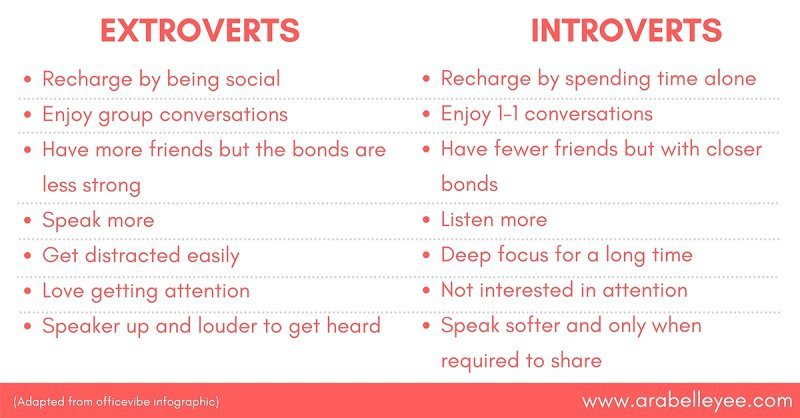

Introverts, extroverts, and ambiverts

A good way to find out where you fall on the spectrum is by asking what you do when you’re tired at the end of the day, says Helgoe. Do you seek out stimulation, such as by getting together with friends, heading to a club, or going to a party? Or do you turn inward, such as by going for a walk alone? Your answer will give you a clue as to your personality type.

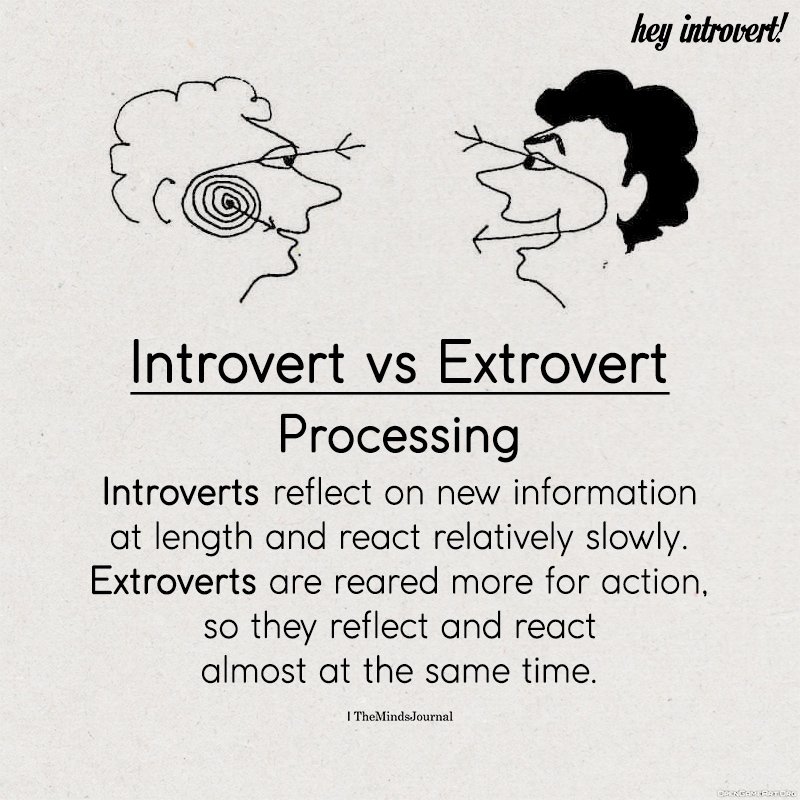

“Extroverts enjoy stimulation—it lights up their brains with dopamine,” says Karl Moore, PhD, an associate professor of strategy and organization at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, who’s writing a book about ambiverts. “Introverts love people, love stimulation, but at a certain point, they tip over and go, ‘Enough of that. I need my own alone time.'”

Genuine ambiverts, on the other hand, are more likely to say their need to recharge depends on what kind of mood they’re in, says Helgoe.

Even babies show signs of responding differently to stimulation, and that’s because it may be hardwired in us.

“An introvert’s brain, when exposed to external stimulation, registers more activity. There’s just more processing internally,” explains Helgoe, who is also an associate professor of behavioral sciences at Ross University School of Medicine in Barbados. “An introvert is more likely to kind of go inward and try to process all the information.”

An extrovert’s brain also reacts to that external stimulation, but in a different way: “For an extrovert, there are specific areas of the brain that have to do with seeking rewards in the external environment,” she says. “So in a way, an extrovert gets stimulated to engage more.”

Signs you’re an ambivert

You can stay on track

Ambiverts don’t seem to be as distracted by external stimuli. Malaysian researchers found that when they hooked ambiverts up to electrodes to measure their brain response, they found they were better able than extroverts to stay focused on tasks, as judged by the more powerful response in the front areas of their brains.

You’re more flexible

If you’re an ambivert, you can act like an introvert and an extrovert, says Moore. After studying executive-level managers, Moore has found that savvy bosses learn to embrace their inner ambivert—chatting up their employees while riding in the elevator, say, and listening carefully to their ideas in meetings instead of talking over them.

True ambiverts do this naturally, he explains. They know how to be outgoing when circumstances demand it (like knowing the right things to say on date nights) and when to be quiet and listen carefully. “So there’s a bit of a back and forth, but they have that flexibility,” Moore notes.

Ambiverts also find it easier to adjust to a variety of people, says Helgoe. “Being an ambivert doesn’t automatically mean that you have emotional intelligence or social skills,” she says. “But there is that ability to adjust—like maybe to step back and listen a little bit more and be more comfortable with that.”

You’re better at persuasion

One of the few studies on ambiverts found that they made better salespeople, racking up more money than introverts or extroverts.

Here’s why, says Moore: “Before I tell you I’ve got something that you need, I’ve listened to what you’re looking for. Then I move into being an extrovert, and I’m excited about my product and how it makes your life better. So a good salesperson both has to listen—introvert—and then be enthusiastic—extrovert.”

You know when to speak up

Introverts only speak up in public when they’ve connected the dots, says Moore, and they don’t jump to conclusions as extroverts do. “Now, there are some negatives that go with that,” Moore says. “One is a paralysis by analysis.”

That’s not you, ambivert. You’re more inclined to share your ideas, even though you won’t air them all the way extroverts do. And you know when to shut up, which extroverts have to work hard at, says Moore.

Bottom line: You have an easier time expressing yourself, engaging both interactively and passively, says Helgoe.

Of course, it’s not all gold stars and good-for-yous: Being so adaptable has its drawbacks, say experts.

Simple decisions might feel draining

“Carl Jung, for example, thought that ambiverts expend more energy because they don’t have a home base,” says Helgoe. By knowing themselves, introverts, for instance, can easily decide to skip an event because they know parties and small talk don’t generally work for them.

An ambivert may be more inclined to waffle. “So it might take more energy to really decide what to do,” says Helgoe.

Your strengths aren’t as strong

“In their better moments, ambiverts are more thoughtful and better listeners, but they aren’t as strong as a real introvert,” says Moore. And your people skills may not be as finely tuned as an extrovert’s either.

You may lack direction

Being so flexible and easygoing gives you a wider range of choices, says Helgoe, especially if you’re self-aware (more on that later). But all that freedom might be overwhelming, leading you to lose direction. The result: you can become indecisive.

You’re unpredictable

“One time you’re like this, and the next time, you’re like that,” says Moore, adding that your flip-flopping can confuse other people—and yourself. For example, people know Moore is an extrovert, so if they happen to find him sitting by himself, they assume he’s sick. “That’s predictable behavior,” he says.

For example, people know Moore is an extrovert, so if they happen to find him sitting by himself, they assume he’s sick. “That’s predictable behavior,” he says.

Ambiverts have to explain themselves by saying, “‘Oh, I’m actually an ambivert. So sometimes I’ll be like an introvert; other times, like an extrovert. And I’m not entirely sure when I do it,'” Moore notes.

The key: knowing yourself

“Ambiverts who are very self-aware can actually really match situations well with what their energies and needs are,” says Helgoe. “Maybe some ambiverts really like certain kinds of stimulation, or they know that ‘I hate public speaking, but I like spontaneous large-group discussions.’ They know the varieties of extroversion and of introversion that they like.”

So how do you gain self-awareness? You can take personality tests that help you spot your patterns. “That would help you be aware that, as a general rule, you like things toned down or revved up more,” says Helgoe. Maybe you don’t have a general rule, but even knowing that is helpful, she says.

If you switch back and forth between introversion and extroversion, you need to become more sensitive to what works for you, and when. Keeping a journal is a way to check in with yourself and track your thoughts, Helgoe says.

“Noticing how things work for you when you engage more out of extroversion or out of introversion is going to help you get more of what you want,” she says.

That’s a lesson everyone can learn, whether you’re an ambivert, introvert, or extrovert.

If you are neither an introvert nor an extrovert, then you are

We readily classify ourselves as introverts or extroverts, the former being especially eager to categorize themselves, uniting with other introverts (virtually, not actually) in a general aversion to parties and small talk. Although in reality, few people fully fit into the definition of one of these types of personalities. For those of us who find ourselves in the middle of the introversion-extroversion scale, there is also a name. Psychologists call such people ambiverts. This means that a person exhibits qualities and demonstrates the behavior of an introvert and an extrovert, depending on the situation.

Psychologists call such people ambiverts. This means that a person exhibits qualities and demonstrates the behavior of an introvert and an extrovert, depending on the situation.

Of course, some can be classified as introverts or extroverts without reservation. But about 38 percent of people fall somewhere between those two extremes, says personality psychologist Robert R. McCrae.

Personal ambivalence has two definitions:

1. if you correspond to the average indicators of the scale (introversion-extroversion) on all points - for example, you feel neutral when you are in a crowd and you are also quite comfortable being alone;

2. if you vacillate between two extremes - sometimes you are the soul of the company, but at other times the only desire is to be alone.

To some extent the classification is arbitrary. Judging the degree of extraversion is like judging a tall person or a short one. The judgment of height is related to what we mean by the definition of "low" and "high", so the assessment of the level of extraversion depends on how we define introvert, extrovert and ambivert.

However, people who can capitalize on the strengths of both personality types—the introvert's ability to withdraw, focus, and introspect with the extrovert's sociability, friendliness, and openness—have an advantage.

"Ambiverts can get the best of both types," says psychologist Brian Little, author of Me, Myself and Us: The Science of Personality and the Art of Well-Being. "Ambiverts have more freedom to build their own lives than those people who belong to the two opposite extremes."

What you should know about ambiverts and the introversion-extroversion scale.

Your extraversion level is determined by how excitable you are.

The definition of introversion or extroversion is not limited to the question of how friendly or social a person is. It is more a question of differences in the degree of excitation of neurons in the cerebral cortex, which acts as the center of such higher mental functions as spatial thinking, thought consciousness, speech, and sensory perception. When the level of arousal is too high, a state of fatigue, tension and congestion can occur. Too low a feeling of boredom and restlessness.

When the level of arousal is too high, a state of fatigue, tension and congestion can occur. Too low a feeling of boredom and restlessness.

There is an optimal level of cortical arousal, explains Brian Little. For extroverts, this level is less than ideal and, therefore, they need exciting, stimulating situations. Introverts have a chronically higher arousal level (meaning they have a lower arousal threshold). As a result, introverts try to reduce their arousal levels by seeking out quiet environments and quiet activities, which is often misinterpreted as antisocial behavior.

Ambiverts, by definition, are alternately at both levels of arousal or may be at an optimal level, which can be considered average, most comfortable and balanced.

Ambiverts can exploit the fluid nature of the personality.

19th-century American psychologist William James once said that by the age of 30, personality hardens like plaster. Some research supports this claim, and the idea of introversion-extroversion as a criterion for categorizing personality implies that we have relatively fixed traits. But Little argues that our personalities can be much more fluid.

But Little argues that our personalities can be much more fluid.

"I think James is only 50 percent right," says Little, who believes that people have what are called "loose traits." An introvert can behave like an extrovert for a while and vice versa, but not for long. If an introvert forces himself to act like an extrovert for too long a period of time - going out and socializing every night, being in turbulent situations too often - he is likely to burn out.

The ambivert moves sequentially between the two categories and has a greater opportunity to take advantage of the nature of variability. The flexible personality of the ambivert adapts better to different situations and makes the most of various personality characteristics.

Little says that ambiverts are in that comfort zone where they can act like pseudo-introverts or pseudo-extroverts without wasting their nervous system.

The advantage of ambiverts in some activities.

Psychologist Dan Pink coined the term "ambivert advantage" to describe the superior ability of ambiverts to build on the strengths of introverts and extroverts.

In particular, ambiverts excel in sales, contrary to the stereotype of the charismatic, ultra-extroverted salesperson. A study by psychologist Adam Grant of the University of Pennsylvania, published in the journal Psychological Science, found that ambiverts are more effective in sales than introverts and extroverts.

Grant studied software company employees and rated each employee on an introversion-extroversion scale from 1 to 7 (1 being the most introverted, 7 being the most extroverted). He found that neither strong introverts (those who scored 1 or 2) nor strong extroverts (those who scored 6-7) were among the best sellers. Ambiverts sold software most effectively.

Grant suggested that while successful salespeople need a certain degree of self-confidence, strong extroverts can be too self-confident and pushy to close a sale. Ambiverts are better able to balance between confidence and sociability.

"My research shows that organizations can benefit from training highly extroverted salespeople to develop some of the calm, reserved traits of their more introverted counterparts," Grant concludes.

Based on huffingtonpost.com

With the light hand of lovers of popular psychology and online tests, we are used to dividing everyone into extroverts and introverts - those who, in their emotions and feelings, are turned to the outside world, and those whose attention is directed to the contemplation of the inner world. However, in the classical classification of Carl Jung, there is also a third type - ambivert. It combines the qualities of both psychotypes and serves as a kind of compromise between the two extremes - thanks to the ability to understand people and quickly adapt to changing conditions, ambiverts more often achieve their goals.

We have collected seven signs of ambiverts - read and perhaps you will recognize yourself in some of them.

They get along well with people

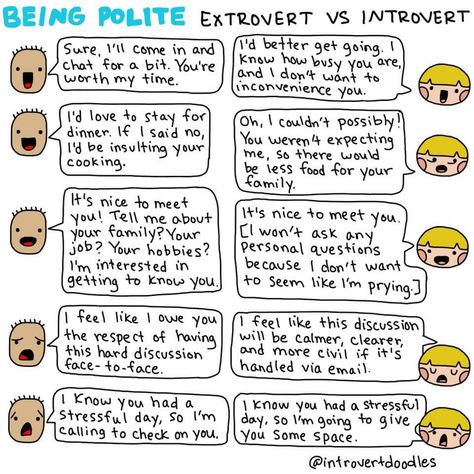

The strength of ambiverts is their phenomenal sense of tact - they understand the "context" and always correlate their actions with the mood of others. No, they do not compromise and do not adapt to others - it's just that ambiverts know what, how and when to do or say in order to get their way and not make enemies.

No, they do not compromise and do not adapt to others - it's just that ambiverts know what, how and when to do or say in order to get their way and not make enemies.

They realize that they need a break from socializing from time to time

Yes, ambiverts can have fun all night long, be the ringleaders at the noisiest party and keep up small talk with ten strangers at the same time, but at some point their internal battery “sits down” and they silently leave the stage. Unlike extroverts, they do not have a dependence on communication - ambiverts understand when to turn off the phone and get out of the “web” of social networks for at least a couple of days. By the way, thanks to such a conscious approach to the needs of their body, people of this psychotype are less prone to emotional burnout.

They prefer to talk one on one

Ambiverts value not the quantity of social connections, but their quality. So when choosing between non-committal chatter and face-to-face conversation, they will, of course, choose the latter. Yes, as mentioned above, ambiverts have no problems with communication - small talk is given to them as easily as James LeBron three-pointers. However, as such, they do not get pleasure from such communications. But a heart-to-heart conversation with a truly interesting person is the value for which ambiverts are ready to drive the whole city and cancel all other important things.

Yes, as mentioned above, ambiverts have no problems with communication - small talk is given to them as easily as James LeBron three-pointers. However, as such, they do not get pleasure from such communications. But a heart-to-heart conversation with a truly interesting person is the value for which ambiverts are ready to drive the whole city and cancel all other important things.

They value personal time and sometimes like to be alone

First, when they receive an invitation to a meeting or event, ambiverts rarely immediately answer yes (and if they agree, they always think over an escape plan in advance). To begin with, they need to weigh everything - is the game worth the candle and time in principle. Secondly, the prospect of staying at home and arranging books in the closet all day does not seem like a bad scenario to them. And finally, they enjoy such conscious social deprivation. However, everything is good in moderation - the daytime isolation of an ambivert must certainly end with an evening conversation with loved ones.

They are tired of relationships that have to be constantly taken care of

Ambiverts like to be friends with their own kind - self-sufficient people who do not require constant attention and communication. Episodic meetings are quite satisfactory for them, but endless correspondence and calls during the day, on the contrary, are tiring. Ambiverts respect the feelings of others and expect the same attitude towards themselves. They can meekly and patiently listen to the complaints of a friend two or three times, but the fourth time they will most likely find some excuse to avoid the conversation (they are unlikely to decide directly about their unwillingness).

They don't like to be noticed

Ambiverts, in principle, do not mind being in the spotlight, but for this they need a good mood and an appropriate attitude. Playing for the public, witty remarks, juggling with jokes, active participation in the discussion require inspiration - ambiverts are not always ready to "spend" their mental strength and take part in the general fun.