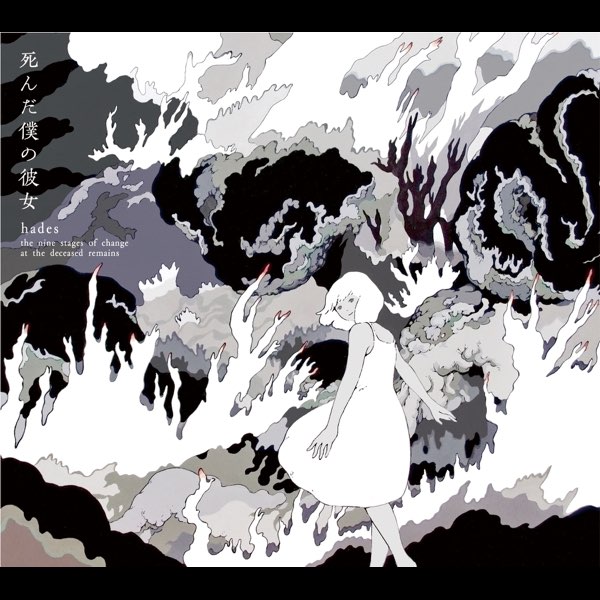

9 stages of death

The Japanese Art of Kusozu Explained

There are a lot of ways humans express themselves through art. In many cultures, it’s common to use art to depict aspects of the human experience that are hard to put into words. This is why you’re likely to encounter various different forms of art about death. In Japan, there’s a particular form of art known as Kusozu, or the art of decomposition.

Jump ahead to these sections:

- What Is Kusozu?

- What Are the Nine Stages of a Decaying Corpse in Kusozu?

- Where Does Kusozu Come From?

- Notable Kusozu Works of Art

What exactly is Kusozu, and how does this art relate to the Japanese attitude toward death? There’s a lot we can understand about death in different cultures by exploring art, literature, and culture. Death is inevitable. It’s a part of humanity that connects everyone together.

Coming to terms with one’s mortality isn’t always easy, so it’s natural to seek meaning through art and self-expression. In this guide, we’ll describe Kusozu as well as the history behind it. Though it might sound grotesque at first, this is a beautiful way to honor our final stage of being—and beyond.

What Is Kusozu?

First, what exactly is Kusozu? In short, this is a form of Japanese watercolor painting that began to get popular starting in the 13th century. Though these are still done today, they decreased in popularity in the 19th century. The paintings themselves use traditional forms of Japanese art and symbolism to depict graphic images of death and decay.

People don’t always feel comfortable talking about what happens to the human body after death. The reality is far from pretty, and these stages of decomposition are off-putting today. This has led to the increase in embalming and other preservation techniques to delay the decomposition process. Conversely, these Japanese artists embraced these stages of death, turning it into an art form in itself.

Another important thing to note about Kusozu is the subject. Not just anyone is depicted as dying through these images. The subject was usually a noblewoman. While the main goal of these images was to show the frailty of mortality and the human body, it’s also a form of objectification for women whose bodies were depicted in these stages of decay.

Not just anyone is depicted as dying through these images. The subject was usually a noblewoman. While the main goal of these images was to show the frailty of mortality and the human body, it’s also a form of objectification for women whose bodies were depicted in these stages of decay.

Nowadays, most people in Japan are cremated (vs. buried). This means the stages of decay are far different, as are cultural customs like Kotsuage. However, the art form still remains preserved in different art courses, schools, and museums.

» MORE: Need help with funeral costs? Create a free online memorial to gather donations.

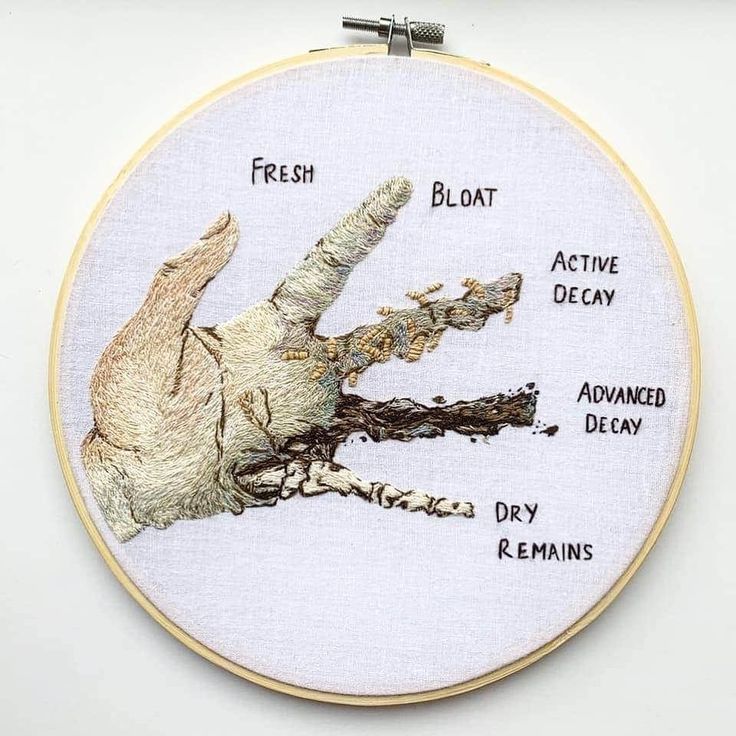

What Are the Nine Stages of a Decaying Corpse in Kusozu?

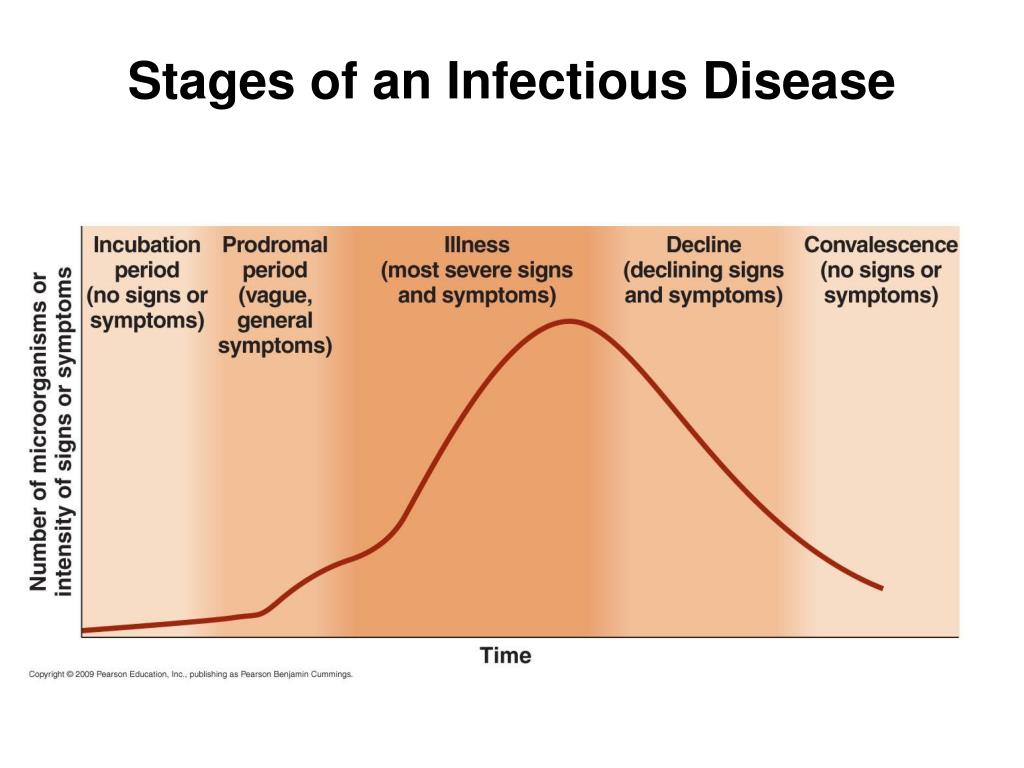

Next, there are nine distinct stages of Kusozu. These begin before death and continue long after the person’s body has decomposed. Though not intended for educational purposes, these stages are similar to what really happens to a body during decomposition. Today, these processes are usually delayed with embalming, freezing, or other modern disposition techniques.

Today, these processes are usually delayed with embalming, freezing, or other modern disposition techniques.

- Stage 1 (Preparation): The noblewoman is very ill, and death is on the horizon. She makes her final preparations and surrounds herself with loved ones.

- Stage 2 (Death): The woman is recently deceased. Her body is attended to by mourners.

- Stage 3 (Distention): As the body begins to decompose, it swells. The muscles stiffen into place (rigor mortis), and bacteria are released into the body from the gut which produces a swelling gas.

- Stage 4 (Leaking): Since there is so much built-up gas within the body, the pressure leads to liquid leaking from parts of the body. It begins in the nose, ears, and mouth.

- Stage 5 (Putrification): The body begins to spill into the nearby soil, nurturing the ground around it.

- Stage 6 (Scavenging): As the body purifies, it emits an aroma that attracts insects and animals who scavenge the remaining flesh.

- Stage 7 (Decay): Only the skeleton remains of the noblewoman.

- Stage 8 (Fragments): Over time, many of the bones have been scattered, scavenged, or destroyed. Only small fragments remain.

- Stage 9 (Memorial): Finally, the process of decay is complete. Nothing remains of the woman’s body except her manmade memorial.

Though these stages are depicted in a series of nine images, this can take much longer in real life. The actual decomposition process depends on many things like the temperature, natural elements, and how the body is prepared for burial. It can take weeks or even months for the stages to be complete, though these visuals give the appearance of minimal time passing.

Where Does Kusozu Come From?

Now that you know the stages of Kusozu, where exactly does this art form come from? From our western perspective, it’s hard to imagine why people would depict such gruesome images of decomposition. This is something we shy away from today. To understand, you have to take a look at how Buddhism depicts death and dying.

In Buddhism, death is a natural part of life. It’s the final step for achieving enlightenment. If you want to become closer to the Buddha’s teachings, you have to acknowledge death and avoid attachment to your mortal form. By depicting death as something gruesome that belongs to the animal kingdom, these artists show the transient nature of humanity.

Viewers of Kusozu were meant to meditate on these works of art. By thinking about what might become of their own bodies after death, they can get closer to true enlightenment. Humans are not seen as important in the grand scheme of eternity. They’re passing beings, and their bodies are inconsequential.

The visibility of corpses

Another reason for Kusozu rising in popularity was the visibility of corpses. In medieval Japan, it was not common for bodies to be buried underground. They weren’t buried until much later in history. During this time, bodies would be laid on the ground and exposed to the elements and wildlife.

Because corpses were so visible, monks often meditated on rotting bodies as a way to understand their own mortality. Even when cremation and burials became more common, this was typically not a luxury afforded to the lower classes. Instead, corpses were left to decay aboveground in graveyards. This acted as source material for many of the images that survive today.

Kusozu and sexuality

Finally, it’s important to note the sexual undertones in some of these images. Because they almost exclusively feature women in the nude, there’s a form of eroticism to these images. There is inherent misogyny to Buddhism, a religion that believes women are inferior to men. Meanwhile, men were expected to overcome their carnal desires to resist womanly charms.

Meanwhile, men were expected to overcome their carnal desires to resist womanly charms.

By depicting these nude images postmortem, beauty is juxtaposed with decay. This not only shows that vanity is shallow, but it also encouraged men (especially monks) to remain celibate. In some ways, kusozu was a form of aversion therapy for those fighting their base desires.

Notable Kusozu Works of Art

Finally, let’s put this into practice by examining some of the most notable Kusozu works of art. These all have similar themes, though artists choose to focus on different parts of the decomposition process throughout time.

» Did you know? Caskets can be bought online, without the funeral home markup. Find the perfect casket

Body of a Courtesan in Nine Stages by Kobayashi EitakuThis work is from the Meiji Era, and it was painted in the 1870s. It’s ink and color on a silk handscroll, depicting nine stages of decomposition. The first image shows a beautiful, wealthy courtesan lounging as she prepares for death. Once deceased, her upper body is fully exposed and she appears to be asleep.

Once deceased, her upper body is fully exposed and she appears to be asleep.

Quickly, her body contrasts her beauty early on as it bloats and leaks blood. In the advanced stages of decomposition, her organs are exposed within her body. Wild animals pick away any remaining flesh until all that’s left are a handful of bones.

The Death of a Noble Lady and the Decay of Her BodyCreated in the 17th century, this is one of the more graphic interpretations of the human cadaver in stages of decay. The woman depicted in this image is suspected to be a ninth-century poetess who was well known for her beauty. In the first image, she sits at a low red table writing her farewell poem to the world. In the second image, she’s dead and is attended by two mourners.

In the third image, she is fully nude. Her body begins to decompose into putrefaction and bones. At last, all that remains is a stupa, a memorial symbol of the Buddha. Nature itself is unaffected, continuing on all the same.

Finally, modern Japanese artist Fukuko Matsue brought this style back in 2004 to critique the misogyny she found present in this art form. Instead of the body rotting away, the subject performs an act of self-mutilation to prevent objectification.

With more anatomical dissection, viewers have a sense of discomfort while viewing. Lastly, this subject stares directly at the viewer, challenging them to watch throughout the stages of decomposition. Matsue believes art in Japan today is too pure, and she uses her skill to challenge these normals while evoking traditional methods.

Explore Death Through Japanese Art

As you can see, the Japanese are one of the pioneers when it comes to the art of the corpse. Finding beauty in the natural world, this genre of painting has strong roots in Japanese ideals. While they remain popular today, many are questioning the social issues on display.

Ultimately, these simple and accurate drawings of human corpses reveal what connects us all: death. Though we might carry ourselves differently throughout life, we all meet the same end.

Though we might carry ourselves differently throughout life, we all meet the same end.

Sources:

- Chin, Gail. “The Gender of Buddhist Truth: The Female Corpse in a Group of Japanese Paintings.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. PSU. PSU.edu.

- Clements, Thomas. “Art of the Corpse.” History Today. HistoryToday.com.

- “Kusōzu: the death of a noble lady and the decay of her body. Watercolors.” Wellcome Collection. WellcomeCollection.org.

- “Trauma and Pain in the Art of Matsui Fuyuko.” Haverford Libraries. HaverfordLibraries.edu.

Categories:

Death and dying Symbols of death

Human Decomposition in Japanese Artwork

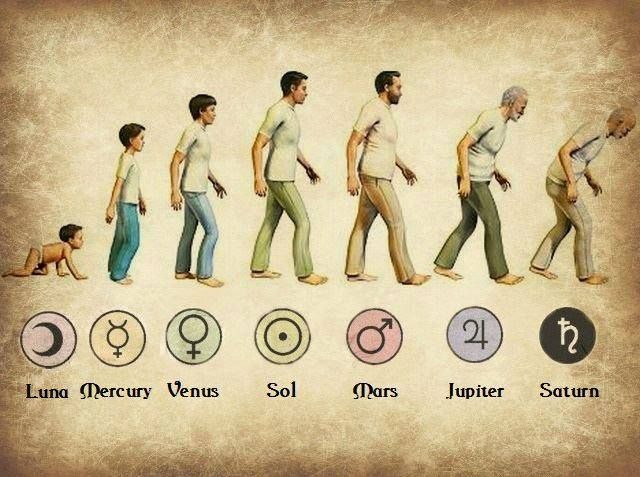

In traditional Buddhist teachings, contemplating about death is an integral part of meditation. Buddha himself said that death is “the greatest of all teachers”, for it teaches us to be humble, destroys vanity and pride, and crumbles all the barriers of caste, creed and race that divide humans, for all living beings are unescapably destined to die. Many Buddhist cultures also practice sky burials, where human corpses are left out in the open, such as mountain tops and forests, to be eaten by wild animals. This may seem macabre and gruesome for people of other cultures, but for practicing Buddhists, sky burial is yet another way of acknowledging the impermanence of life.

Many Buddhist cultures also practice sky burials, where human corpses are left out in the open, such as mountain tops and forests, to be eaten by wild animals. This may seem macabre and gruesome for people of other cultures, but for practicing Buddhists, sky burial is yet another way of acknowledging the impermanence of life.

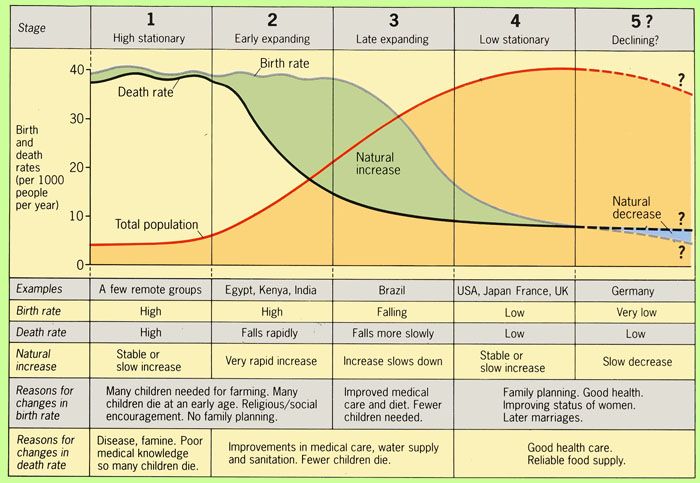

Such pragmatic and mature approach to the subject of death is the rationale behind the gory and unapologetic Japanese art form called kusôzu that appeared in the 13th century and continued until the late 19th century. Kusôzu, which means “painting of the nine stages of a decaying corpse”, portrays the sequential decay of a cadaver, usually female, in graphic detail. The shocking art genre appeared routinely for more than five hundred years in various formats, including scrolls and printed books.

One of the earliest examples of this genre is a 14th-century scroll titled Kusōshi emaki, whose English translation is rare lengthy—”Illustrated handscroll of the poem of the nine stages of decaying corpse”. The scroll consist of ten narrative illustrations portraying the nine stages of decomposition starting with a healthy subject—an aristocratic female who has been identified as the 9th-century poetess, Ono no Komachi. In the second panel, she has died and is laid out on the floor and covered with a blanket. In subsequent panels, her body, now in the open, can be seen getting progressively decomposed and putrefied until all remaining flesh and bones had been pecked clean by scavenging animals.

The scroll consist of ten narrative illustrations portraying the nine stages of decomposition starting with a healthy subject—an aristocratic female who has been identified as the 9th-century poetess, Ono no Komachi. In the second panel, she has died and is laid out on the floor and covered with a blanket. In subsequent panels, her body, now in the open, can be seen getting progressively decomposed and putrefied until all remaining flesh and bones had been pecked clean by scavenging animals.

Below: Body of a courtesan in nine stages of decomposition. Ink and color on silk, circa 1870s. Courtesy: British Museum

“The function of these works is to demonstrate the effects of impermanence and the gross nature of the human form, especially the female one,” writes Gail Chin. “The pictorial function is attuned to Buddhist meditation on the corpse, which is to instill a deep sense of revulsion for the human body, particularly that of the opposite sex, so that the monk or devotee will not be tempted by the flesh and realize the impermanence of the body, especially their own, and renounce it. ”

”

In Buddhism, overcoming sexual desire is a necessary step towards achieving enlightenment. Since the female body was a source of desire for men, meditating on a decaying corpse became a form of aversion therapy for Buddhist monks. Not only men, women too were asked to meditate on the repulsive aspects of their own body.

The use of the female cadaver as a tool to despise one’s own body has a long tradition in Buddhist literature dating back to medieval times. However, the visual depiction of this theme is a specifically Japanese adaptation.

Some modern scholars have interpreted the exclusive use of female corpses in the kusōzu genre as a testament to the prevalence of misogyny in Japanese Buddhist thought. But Gail Chin denies this claim by arguing that because the female body is used to teach one of the most important Buddhist lessons, she must be inherently valued as representing Buddhist truth.

Below: The death of a noble lady and the decay of her body. circa 1700s

circa 1700s

In the first painting a court lady in a kimono is seated indoors at a low red table, with a scroll in her left hand, upon which she has written her farewell poem: she is pallid, and her expression is preoccupied.

In the second painting, she has died, and is laid out on the floor covered to her shoulders with a blanket, with a lady and a gentleman in attendance.

In this painting, her body is out of doors, naked apart from a loincloth, on a mat, the lower part of which is folded up over her legs; her skin now has flesh tones.

In the fourth painting, putrefaction has just begun.

Here her body is decaying in the advanced stages of putrefaction.

The putrefying body is now carrion for scavenging birds and small animals.

The flesh has almost all decayed revealing the skeleton. There are wisteria flowers in blossom above her body.

Only a few fragments of bone, including the skull and fragments of rib. hand and vertebrae remain visible.

hand and vertebrae remain visible.

The final image is of a memorial structure upon which her Buddhist death-name is inscribed in Sanskrit.

Five stages of grief. The Rise and Fall of Kübler-Ross

- Lucy Burns

- BBC

Image copyright Getty Images

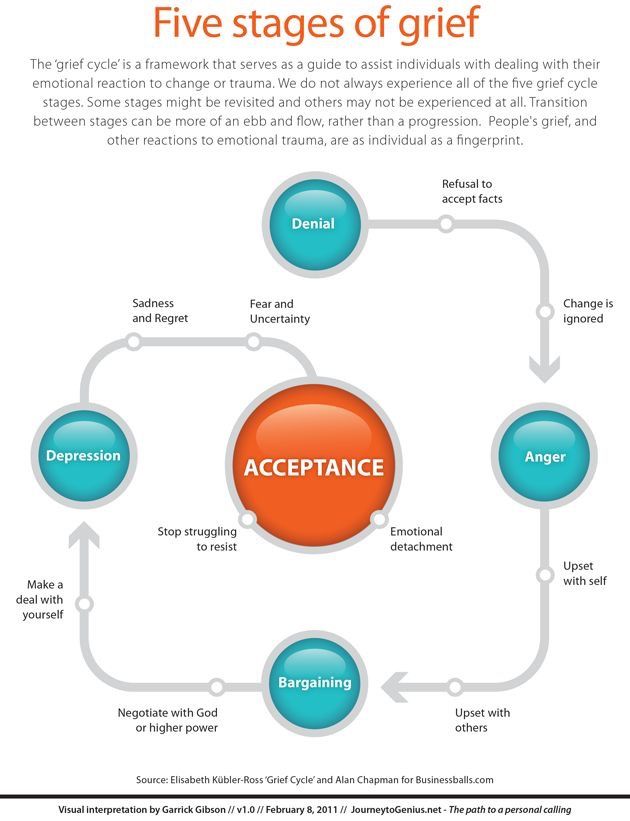

Denial. Anger. Finding a compromise. Despair. Adoption. Many people know the theory according to which grief, when receiving unbearable information for a person, goes through these steps. The scope of its application is wide: from hospices to boards of directors of companies.

A recent interview with a psychologist in English on the Internet proves that the perception of the current quarantine is subject to the same rules. But do we all experience the same?

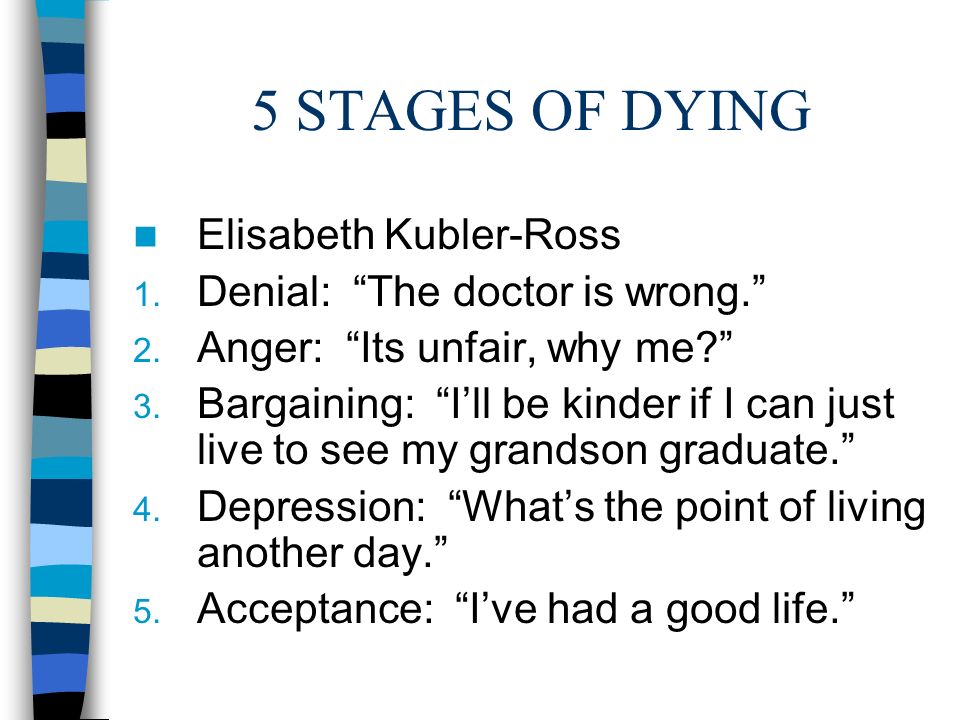

When Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross began working in American hospitals in 1958, she was struck by the lack of methods of psychological care for dying patients.

- A method that can predict your death

"Everything was impersonal, the attention was paid exclusively to the technical side of things," she told the BBC at 1983 year. “Terminally ill patients were left to their own devices, no one talked to them.”

She started a workshop with Colorado State University medical students based on her conversations with cancer patients about what they thought and felt.

Author photo, LIFE/Getty Images

Photo caption,Elisabeth Kübler-Ross talks to a woman with leukemia in Chicago, 1969. Seminar participants observe through a special mirror glass

Despite the misunderstanding and resistance of a number of colleagues, soon there was nowhere for an apple to fall at the Kübler-Ross seminars.

In 1969 she published a book, On Death and Dying, in which she quoted typical statements from her patients and then moved on to discuss how to help doomed people pass from life as free of fear and pain as possible.

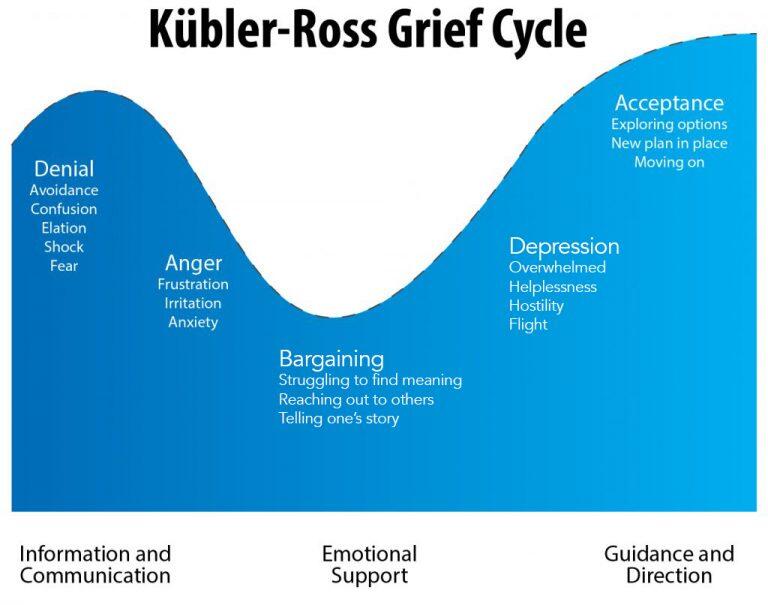

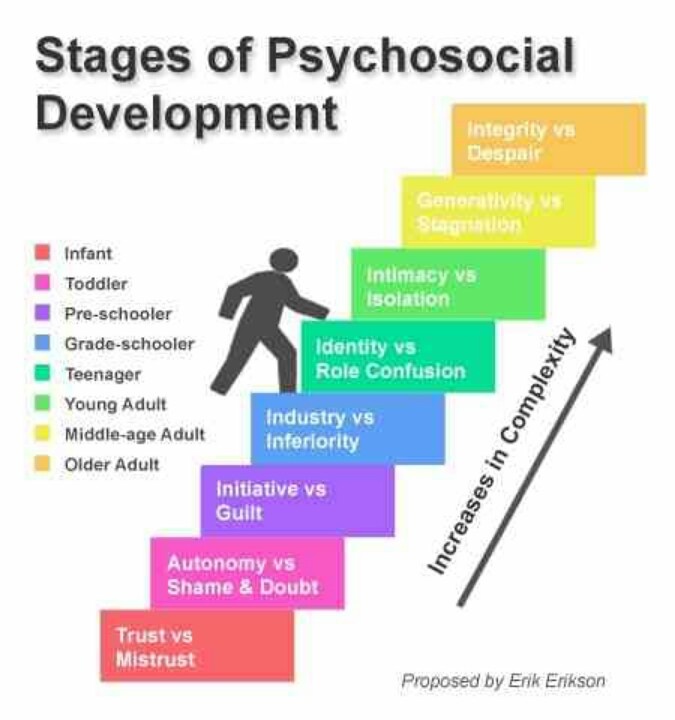

Kübler-Ross described in detail the five emotional states that a person goes through after being diagnosed with a terminal diagnosis:

- Denial: "No, that can't be true"

- Anger: "Why me? Why? It's not fair!!!"

- Bargaining: "There must be a way to save myself, or at least improve my situation! I'll think of something, I'll behave properly and do whatever is necessary!"

- Depression: "There is no way out, everything is indifferent"

- Acceptance: "Well, we must somehow live with this and prepare for the last journey"

difficult situation.

A separate chapter of the book is devoted to each of the stages. In addition to the five main ones, the author identified intermediate states - the first shock, preliminary grief, hope - from 10 to 13 types in total.

Image copyright Getty Images

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross died in 2004. Her son, Ken Ross, says she never insisted that every person must go through these five stages in sequence.

Her son, Ken Ross, says she never insisted that every person must go through these five stages in sequence.

"It was a flexible framework, not a panacea for dealing with grief. If people wanted to use other theories and models, the mother did not object. She wanted to start a discussion of the topic first," he says.

- Last will: how did the photo of a dying American touch the world?

- "You hear everything, Fernando." How was the evening in honor of the terminally ill football player

The book "On Death and Dying" became a bestseller, and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was soon inundated with letters from patients and doctors from all over the world.

"The phone kept ringing, and the postman started visiting us twice a day," recalls Ken Ross.

The notorious five steps took on a life of their own. Following the doctors, patients and their relatives learned about them. They were mentioned by the characters of the series "Star Trek" and "Sesame Street". They were parodied in cartoons, they gave food for creativity to the mass of musicians and artists and gave rise to many successful memes.

They were mentioned by the characters of the series "Star Trek" and "Sesame Street". They were parodied in cartoons, they gave food for creativity to the mass of musicians and artists and gave rise to many successful memes.

Literally thousands of scientific papers have been written that have applied the theory of the five steps to a wide variety of people and situations, from athletes suffering career-incompatible injuries to Apple fans' worries about the release of the 5th iPhone.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of History Podcast

Kübler-Ross's legacy has found its way into corporate governance: Big companies from Boeing to IBM (including the BBC) have used her "change curve" to help employees at times of great business change.

And during the coronavirus pandemic, it applies, says psychologist David Kessler.

Kessler worked with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and co-authored her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve. His interview with the Harvard Business Review at the start of the pandemic garnered a lot of attention online as people everywhere searched for solutions to their emotional problems.

"And here, first comes denial: the virus is not terrible, nothing will happen to me. Then anger: who dares to deprive me of my usual life and force me to stay at home?! Then an attempt to find a compromise: okay, if after two weeks of social distancing it gets better, then why not? Followed by sadness: no one knows when it will end. And, finally, acceptance: the world is now like this, you have to somehow live with it, "describes David Kessler.

"As you can see, strength comes with acceptance. It gives you control: I can wash my hands, I can keep a safe distance, I can work from home," he says.

"It's a roadmap," says George Bonanno, professor of clinical psychology and head of the Loss, Trauma, and Emotion Laboratory at Columbia University. "When people are in pain, they want to know: how long will it last? What will happen to me? something to grab on to. And the five-step model gives them that opportunity."

"This scheme is seductive," notes Charles Corr, social psychologist and author of Death and Dying, Life and Being. "It offers an easy solution: sort everyone, and it takes no more than the fingers of one hand to label each one." .

George Bonanno sees this as a possible harm.

"People who don't fit exactly into these stages - and I've seen the majority of them - may decide they're grieving the wrong way, so to speak," he explains.

According to him, over the years he has seen many cases when people themselves inspired that they must certainly experience this and that, or they were convinced of this by friends and relatives, but they did not feel it and decided, that they need a doctor.

Experimental evidence of the existence of the five stages of grief is not enough. The longest and most extensive bereavement interview was conducted in 2007.

According to him, the most common state at any time is acceptance, only a few go through the stage of denial, and the second most common emotion is longing.

However, according to David Kessler, while scientists debate the nuances and terms, people who experience grief continue to find meaning in the Kübler-Ross scheme.

"I meet people who tell me, 'I don't know what's wrong with me. Now I'm angry, and a minute later I'm sad. I must be crazy.” And I say, “It has names. These are called the stages of grief.” The person says, “Oh, so there is a special stage called 'anger'? It's about me!" And feels more normal."

Image copyright, Getty Images

"People need catchy statements. If Kübler-Ross hadn't called it stages and stated that there are exactly five of them, then she probably would have been closer to the truth. But then she would not have attracted to attention," says Charles Corr.

But then she would not have attracted to attention," says Charles Corr.

He believes that talking about the five stages distracts from the main scientific legacy of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

"She wanted to take on the topic of death and dying in the broadest sense: how to help terminally ill people come to terms with their diagnosis, how to help those who care for them, support these patients and cope with their own emotions, how to help everyone live a full life, realizing that we are not eternal,” says Charles Corr.

"The terminally ill can teach us everything: not only how to die, but also how to live," said Elisabeth Kübler-Ross at 1983 year.

During the 1970s and 1980s, she traveled the world, giving lectures and giving workshops to thousands of people. She was a passionate supporter of the hospice idea pioneered by British nurse Cecily Saunders.

Kübler-Ross has established hospices in many countries, the first in the Netherlands in 1999. Time magazine named her one of the 100 most important thinkers of the 20th century.

Time magazine named her one of the 100 most important thinkers of the 20th century.

Professor Kübler-Ross' scientific reputation was shaken after she became fascinated with theories about the afterlife and began to experiment with mediums.

One of them, a certain Jay Barham, practiced non-standard religious-erotic therapy, in particular, he persuaded women to have sex, assuring that he was possessed by a person close to them from the afterlife. In 1979, because of this, a loud scandal arose.

In the late 1980s, she tried to set up a hospice for children with AIDS in rural Virginia, but faced strong local opposition to the idea.

In 1995, her house caught fire under suspicious circumstances. The next day Kübler-Ross had her first stroke.

She spent the last nine years of her life with her son in Arizona, moving around in a wheelchair.

In her last interview with the famous TV presenter Oprah Winfrey, she said that at the thought of her own death she feels only anger.

"The public wanted the famed expert on death and dying to be some kind of angelic personality and quickly get to the stage of acceptance," says Ken Ross. "But we all deal with grief and loss as best we can."

The theory of the five stages of grief is not widely taught in medical schools these days. It is more popular at corporate trainings under the name "Curve of Change".

Since then, there have been many theories about how to deal with your grief.

David Kessler, with the consent of Kübler-Ross's family, added a sixth stage to the five: the understanding that everything that is done makes sense.

"Understanding can come in a million different ways. Let's say I've become a better person after losing a loved one. Maybe my loved one passed away in a different way than it should have happened, and I can try to make the world a better place to this has not happened to others," says David Kessler.

Charles Corr recommends the "double process model". It was developed by Dutch researchers Margaret Stroebe and Nenk Schut and suggests that a person in grief is simultaneously experiencing a loss and preparing himself for new things and life challenges.

It was developed by Dutch researchers Margaret Stroebe and Nenk Schut and suggests that a person in grief is simultaneously experiencing a loss and preparing himself for new things and life challenges.

George Bonanno talks about four trajectories of grief. Some people have great stamina and do not fall into depression, or it is weakly expressed in them, others remain morally broken for many years, still others recover relatively close, but then a second wave of grief rolls over them, and finally, fourth ones become stronger from loss.

Over time, one way or another, the vast majority of people get better.

But Professor Bonanno admits that his approach is less clear-cut than the five-stage theory.

"I can say to a person: 'Time heals.' But that doesn't sound so convincing," he says.

Grief is difficult to control and hard to endure. The thought that there is some kind of road map that suggests a way out is comforting, even if it is an illusion.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, in her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve, wrote that she did not expect to sort out the tangled human emotions.

Everyone experiences grief in their own way, even if some patterns can sometimes be deduced. Everyone goes their own way.

Stages of accepting the inevitable: what you need to know HR

A person's life consists not only of joyful events and success, sometimes we face problems or situations that we cannot influence in any way. Confirmation is the COVID-19 pandemic and the global crisis, due to which many people lost their jobs, the owners were forced to close both projects and organizations completely. During these drastic and unpleasant changes, we go through the five stages of accepting the inevitable: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Since HR is a person whose job is to interact with people, we decided that it would be useful for you to understand both how you feel in difficult situations, when nothing depends on you, and the feelings of employees. Today we'll discuss Elisabeth Kübler-Ross' model for accepting the inevitable and break down each of the five stages.

Today we'll discuss Elisabeth Kübler-Ross' model for accepting the inevitable and break down each of the five stages.

A bit of history: the Kubler-Ross model

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross is an American doctor and psychiatrist who was the first to reveal and describe all five stages of accepting the inevitable in her book On Death and Dying. Initially, the practice of the five stages was used only to help people come to terms with the loss of a loved one due to a terminal illness.

After the release of Elizabeth's book, this model began to be actively used in psychology to help people who are in a state of stress or crisis. Today, this technique is known all over the world. It helps a person to look at the situation from a different perspective, rethink the problem, accept it and move on.

How long each of the stages will last depends on the person's environment, his status in society, and the characteristics of the generation to which he belongs. For example, people of generation Y, when inevitable and unpleasant situations arise, can radically change their lives: move to another city or withdraw into themselves. Thus, they want to start from scratch and escape from problems.

Thus, they want to start from scratch and escape from problems.

Stage #1. Denial

The first stage in which a person tries in every possible way to deny reality, ignoring both external events and the internal state. At the stage of denial, we feel stupor, shock, pretend that nothing has changed.

The danger of this state is that a person accumulates a lot of negativity and negative energy, because of which this stage can last a very long time. But on the other hand, such detachment and stupor gives a person time to realize everything in proportion and accept difficult information in stages, and not en masse.

How to help a person go through the stage of denial?

It is very important to maintain contact with a person and carefully help him to return to reality. Try asking him questions he's afraid to answer. For example, what happened, how does he feel about it, what would he like to change, etc. The answers to these questions will help a person to see the problem from different angles. It is difficult to do this on your own, because the subconscious mind understands that after that it will be very painful.

It is difficult to do this on your own, because the subconscious mind understands that after that it will be very painful.

A person can go through this stage both in a few minutes, and in a few weeks, months or even years. In most cases, the duration of this stage takes about two months. It is important to remember that denial is a normal and inherent reaction of the body to a difficult situation and it is impossible to avoid it.

Stage #2. Anger

After realizing the situation or after unpleasant changes, the stage of anger begins, which is considered one of the most difficult. At this stage, a person experiences bursts of aggression, thinks that no one understands him and is looking for an object with which he will be angry. It can be bosses, neighbors, friends and even the person himself.

The danger of this stage is that a person may try to restrain the negative energy inside, because of which it will not be possible to get out of this state painlessly. There are many ways to release negativity. For example, go in for sports: exercise, jog, fitness, or join the art: draw, write poetry, etc. Sublimating negative energy into some kind of activity will help balance the hormonal background, which will mitigate anger, aggression and tension.

There are many ways to release negativity. For example, go in for sports: exercise, jog, fitness, or join the art: draw, write poetry, etc. Sublimating negative energy into some kind of activity will help balance the hormonal background, which will mitigate anger, aggression and tension.

In addition, another danger of the anger stage is that in this state we can lash out at others. Because of this, relationships with people can deteriorate, you can lose friends or even work.

How to help a person to pass the stage of anger?

Help to find a way to splash energy into some activity and do not take its negative emissions to heart. Remember that this stage proceeds faster than the others and is delayed only in rare cases.

Subscribe to HR and Recruiters Newsletter! Be trendy with Hurma 😉

Thank you!

You are subscribed!

Stage #3. Bargaining

When a person understands that the situation or changes are inevitable and there is no point in looking for the guilty, the third stage begins - bargaining. At this stage, we want to postpone the inevitable, correct the situation by starting to bargain. Psychologists call the trading stage “What if?”. It is in this phrase that the very trades are hidden. A person asks himself questions, what if I change, find another job, behave differently, then maybe everything will change. In this way we bargain with ourselves or even with those around us.

At this stage, we want to postpone the inevitable, correct the situation by starting to bargain. Psychologists call the trading stage “What if?”. It is in this phrase that the very trades are hidden. A person asks himself questions, what if I change, find another job, behave differently, then maybe everything will change. In this way we bargain with ourselves or even with those around us.

The danger of this stage lies in the loss of authority and reputation when bargaining with subordinates, employees, partners in order to pity them. In addition, at the trading stage, a person feeds himself with the illusion that the problem is about to be solved and everything will be as before. Bidding lasts for several weeks, but in individual cases, it can be delayed for an indefinite period.

How to help a person pass the bargaining stage?

At this stage, little depends on others. All that is needed is time, after which the person himself realizes that attempts to find solutions do not bring the desired result. Then he will move on to one of the most difficult stages - depression.

Then he will move on to one of the most difficult stages - depression.

Stage #4. Depression

The stage of depression is considered one of the most difficult and protracted, and it sets in abruptly, literally in one second. Depressed people behave differently, some can withdraw into themselves, not go out and not take care of themselves, while others, on the contrary, actively communicate with people, work, but suffer at the same time.

The danger of depression is that because of it a person looks negatively at the whole world around him. He can be financially secure, constantly travel, have many friends, but perceive everything in a negative way and not receive positive emotions. According to WHO data for 2018, about 264 million people worldwide suffer from depression.

Another danger of depression is the activation of all addictions. A person begins to smoke, drink alcohol, seize grief, constantly play games. Thus, he is looking for an activity that will help him to forget at least for a while. In addition, during depression, people often experience complete emotional and professional burnout.

In addition, during depression, people often experience complete emotional and professional burnout.

The stage of depression is often noticeable in the working environment. Employees who experience depression are extremely demotivated and often absent: they take sick leave, vacations.

How to help a person go through depression?

At the stage of depression, a psychologist is the best help, since this is already a psychological problem. As an HR specialist, you can spend 1:1 with an employee, talk to his manager, perhaps offer a vacation or pay a psychologist. Remember that a depressed person needs the support of a team and loved ones.

Stage #5. Acceptance

At this stage, a person begins to think rationally and accept the situation. He recognizes that the problem does not allow him to live normally and understands that he needs to step over it and move on. After the acceptance stage, we begin a “new life” with new circumstances.