Native american word for nature

Native American Indian Words

Native American Indian WordsAmerican Indian languages American Indian tribes What's new on our site today!

Sponsored Links

Algonquin words

Anishinabe words

Arapaho words

Atikamekw words

Blackfoot words

Cheyenne words

Cree words

Etchemin words

Gros Ventre words

Kickapoo words

Lenape/Delaware words

Loup A

Loup B

Lumbee/Croatan words

Maliseet/Passamaquoddy words

Menominee words

Meskwaki/Sauk words

Miami/Illinois words

Mi'kmaq/Micmac words

Mohegan/Pequot words

Mohican/Stockbridge words

Montagnais Innu words

Munsee Delaware words

Nanticoke words

Narragansett words

Naskapi words

Ojibway/Chippewa/Ojibwe words

Potawatomi words

Powhatan words

Shawnee words

Wampanoag words

Wiyot words

Yurok words

Arawakan Language Family Achagua words

Aikana words

Amarizana words

Amuesha words

Anauya words

Apurina words

Arawak words

Aruan words

Ashaninka words

Baniva words

Baniwa words

Bare words

Baure words

Cabiyari words

Canamari words

Caquetio words

Caquinte words

Carutana words

Cawishana words

Chamicuro words

Chontaquiro words

Curripaco words

Garifuna words

Guana words

Guajiro words

Guarequena words

Guinao words

Inapari words

Inyeri words

Irantxe words

Island Carib words

Jumana words

Kariai words

Karipuna words

Machiguenga words

Maipure words

Manao words

Mandawaka words

Mapidian words

Marawa words

Marawan words

Mariate words

Mawakwa words

Mehinaku words

Mojo words

Nomatsiguenga words

Paicone words

Palikur words

Paresi words

Pase words

Paunaca words

Piapoco words

Piro words

Resigaro words

Saraveca words

Shebayo words

Taino words

Tariano words

Terena words

Wainuma words

Wapishana words

Waraiku words

Waura words

Wirina words

Xiriana words

Yabaana words

Yavitero words

Yawalpiti words

Yucuna words

Athabaskan Language Family Ahtna words

Babine words

Western Apache words

Beaver words

Carrier words

Chipewyan/Dene words

Clatskanie words

Deg Xitan words

Dogrib words

Gwich'in words

Haida words

Hupa words

Kaska words

Kato words

Koyukon words

Mattole words

Navajo words

Sarcee words

Sekani words

Tanana words

Tlingit words

Tolowa words

Tututni words

Wailaki words

Barbacoan Language Family Awa Pit words

Cara words

Chachi words

Coconuco words

Colorado words

Guambiano words

Pasto words

Telembi words

Totoro words

Caddoan Language Family Arikara words

Caddo words

Kitsai words

Pawnee words

Wichita words

Cariban Language Family Akawaio words

Akurio words

Apalai words

Arara do Para words

Atruahi words

Bakairi words

Camaracoto words

Carib words

Carijona words

Chaima words

Cumanagoto words

Enepa words

Hixkaryana words

Ingariko words

Ikpeng words

Japreria words

Kaxuiana words

Kuikuro words

Macushi words

Mapoyo words

Matipuhy words

Maquiritari words

Pemon words

Saluma words

Shikiana words

Tamanaku words

Trio words

Waiwai words

Wayana words

Yabarana words

Yaruma words

Yukpa words

Chibchan Language Family Bari words

Bogota words

Boruca words

Bribri words

Buglere words

Cabecar words

Changuena words

Chibcha words

Corobici words

Cueva words

Cuna words

Damana words

Dorasque words

Duit words

Huetar words

Ika words

Kankuamo words

Kogui words

Maleku words

Ngabere words

Nutabe words

Rama words

Teribe words

U'wa words

Gulf Language Family Atakapa words

Bidai words

Chitimacha words

Natchez words

Tunica words

Hokan Language Family Achumawi words

Atsugewi words

Chimariko words

Chumash words

Cochimi words

Cocopa words

Esselen words

Karok words

Kashaya words

Kiliwa words

Kumiai words

Havasupai words

Maricopa words

Mojave words

Oaxaca Chontal words

Paipai words

Pomo words

Quechan (Yuma) words

Salinan words

Seri words

Shasta words

Washo words

Iroquoian Language Family Cayuga words

Cherokee words

Iroquois words

Laurentian words

Mohawk words

Nottoway words

Oneida words

Onondaga words

Seneca words

Susquehannock words

Tuscarora words

Wyandot/Huron words

Jivaroan Language Family Achuar words

Aguaruna words

Huambisa words

Shuar words

Macro-Ge Language Family Apinaye words

Bororo words

Xavante words

Mayan Language Family Acatec words

Achi words

Aguacateco words

Chicomuceltec words

Ch'ol words

Chontal de Tabasco words

Chorti words

Chuj words

Huasteco words

Itza Maya words

Ixil words

Jacalteco words

Kakchikel Maya words

Kanjobal words

Kekchi words

Lacandon words

Mam words

Mocho words

Mopan words

Pocomchi words

Pokomam words

Quiche words

Sacapulteco words

Sipacapense words

Tectiteco words

Tojolabal words

Tzeltal words

Tzotzil words

Tzutujil words

Uspanteco words

Yucatec Maya words

Muskogean Language Family Alabama words

Apalachee words

Chickasaw words

Choctaw words

Hitchiti words

Houma words

Koasati words

Miccosukee words

Muskogee words

Oto-Manguean Language Family Amuzgo words

Chatino words

Chinanteco words

Chocho words

Chorotega words

Ixcatec words

Mangue words

Matlatzinca words

Mazahua words

Mazateco words

Mixteco words

Otomi words

Pame words

Popoloca words

Subtiaba words

Tlahuica words

Tlapaneco words

Triqui words

Zapotec words

Pano-Tacanan Language Family Amahuaca words

Araona words

Atsahuaca words

Capanahua words

Cashibo words

Cashinahua words

Cavinena words

Chacobo words

Chitonahua words

Huarayo words

Katukina words

Kaxarari words

Marubo words

Mastanahua words

Matis words

Mayoruna words

Pacahuara words

Poyanawa words

Reyesano words

Sharanahua words

Shipibo words

Tacana words

Tuxinawa words

Yaminawa words

Yawanawa words

Penutian Language Family Alsea words

Chinook words

Chinook Jargon words

Costanoan words

Kathlamet words

Klamath words

Miwok words

Nez Perce words

Maidu words

Molalla words

Tsimshian words

Wasco-Wishram words

Wintu words

Yakama Sahaptin words

Yokuts words

Salishan Language Family Chehalis words

Coeur d'Alene words

Columbian words

Cowlitz words

Halkomelem words

Klallam words

Lushootseed words

Nooksack words

Nuxalk/Bella Coola words

Okanagan words

Quinault words

Salish words

Twana words

Straits Salish words

Siouan Language Family Assiniboine words

Biloxi words

Catawba words

Crow words

Dakota Sioux words

Hidatsa words

Hochunk words

Kansa words

Lakota Sioux words

Mandan words

Ofo words

Omaha-Ponca words

Osage words

Oto words

Quapaw words

Sioux words

Stoney words

Tutelo words

Woccon words

Tucanoan Language Family Bara words

Barasana words

Orejon words

Secoya words

Tupian Language Family Ache words

Guarani words

Shipaya words

Uto-Aztecan Language Family Cahuilla words

Chemehuevi words

Comanche words

Cora words

Cupeno words

Gabrielino words

Hopi words

Huichol words

Juaneno words

Kawaiisu words

Luiseno words

Mayo words

Mono words

Nahuatl/Aztec words

Northern Paiute words

Opata words

Panamint words

Pima Bajo words

Pipil words

Serrano words

Shoshone words

Southern Paiute words

Tarahumara words

Tepehuan words

Tohono O'odham/Papago words

Tubatulabal words

Varihio words

Yaqui words

Wakashan Language Family Haisla words

Heiltsuk words

Kwakiutl words

Makah words

Nootka words

Other American Indian Languages Abipon words

Adai words

Amarakaeri words

Andoa words

Arabela words

Ayaman words

Aymara words

Ayoreo words

Beothuk words

Bora words

Camsa words

Cahuarano words

Candoshi words

Chayahuita words

Cofan words

Gayon words

Guahibo words

Huachipaeri words

Huave words

Jebero words

Jirajara words

Kadiweu words

Karankawa words

Keres words

Kiowa words

Kootenai words

Mapuche words

Matlatzinca words

Michif creole words

Miskito words

Mixe words

Mocovi words

Muinane words

Muniche words

Ona words

Paez words

Pilaga words

Popoloca words

Puelche words

Quechua words

Quileute words

Sumu words

Tehuelche words

Tepehua words

Tewa words

Ticuna words

Timucua words

Tlahuica words

Toba words

Tonkawa words

Totonac words

Ulwa words

Urarina words

Vilela words

Waorani words

Wappo words

Warao words

Witoto words

Yagua words

Yuchi words

Yuki words

Zaparo words

Zoque words

Zuni words

Other Native Languages of the Americas Hawaiian words

Inuktitut words

Aleut words

Yupik words

Alutiiq wordsSponsored Links

Back to American Indian Cultures

Back to American Indian Names

Go on to American Indian Genealogy

SitemapContact UsOrrinLaura

Would you like to help support our organization's work with endangered American Indian languages?

Native Languages of the Americas website © 1998-2020

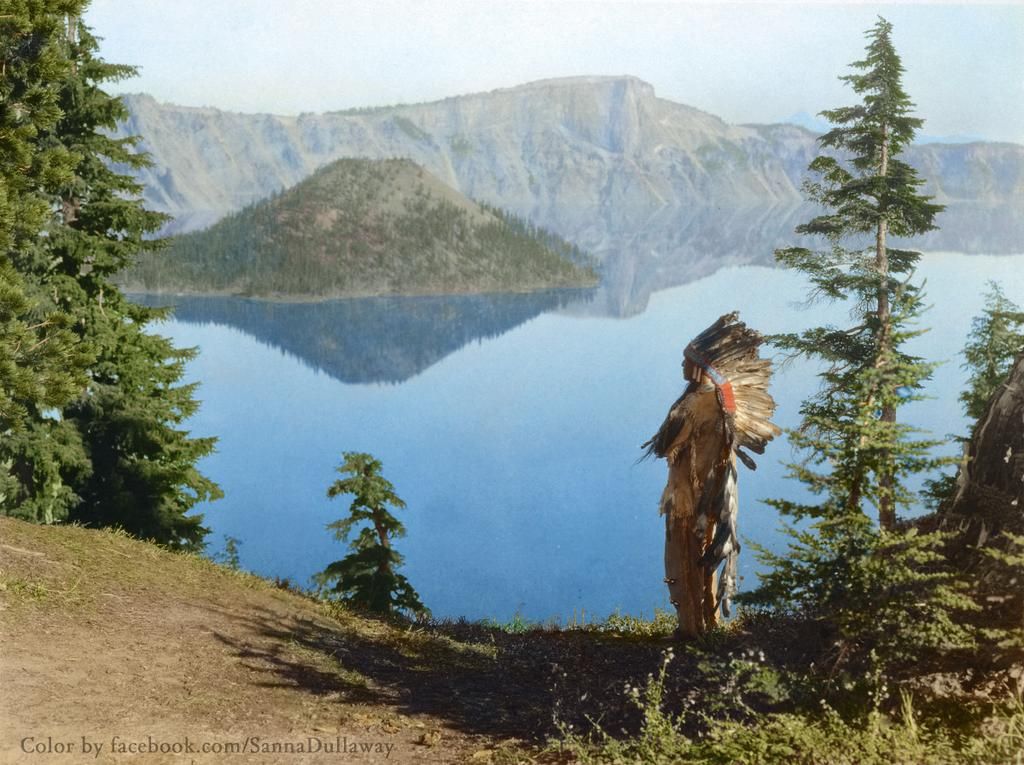

Nature’s Role in American Indian Culture

Posted

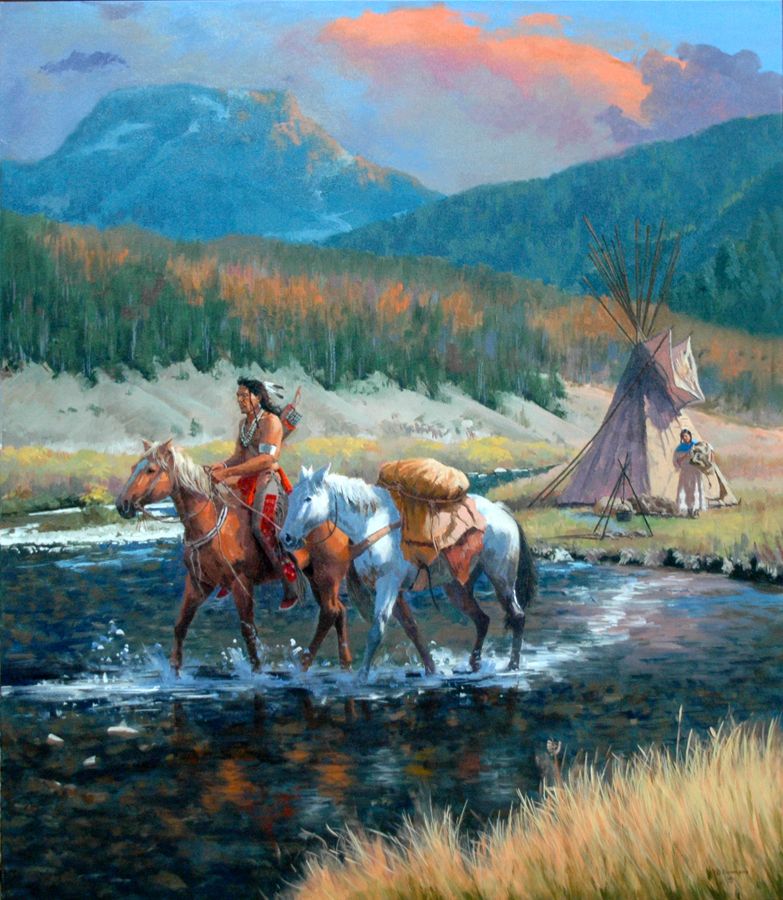

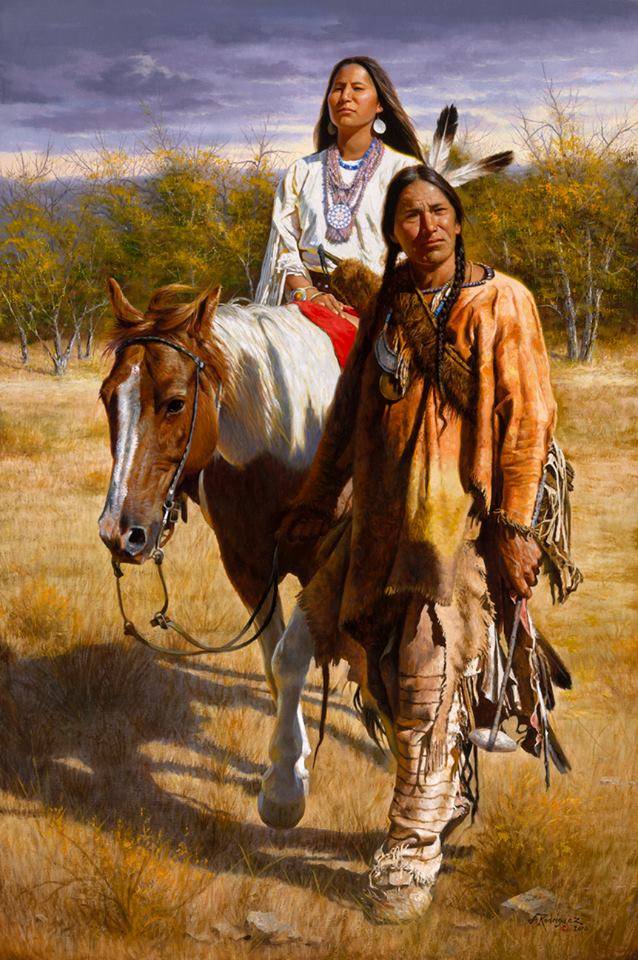

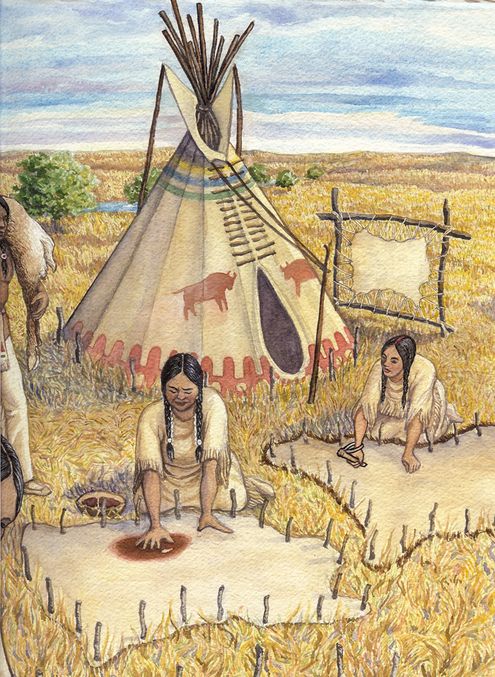

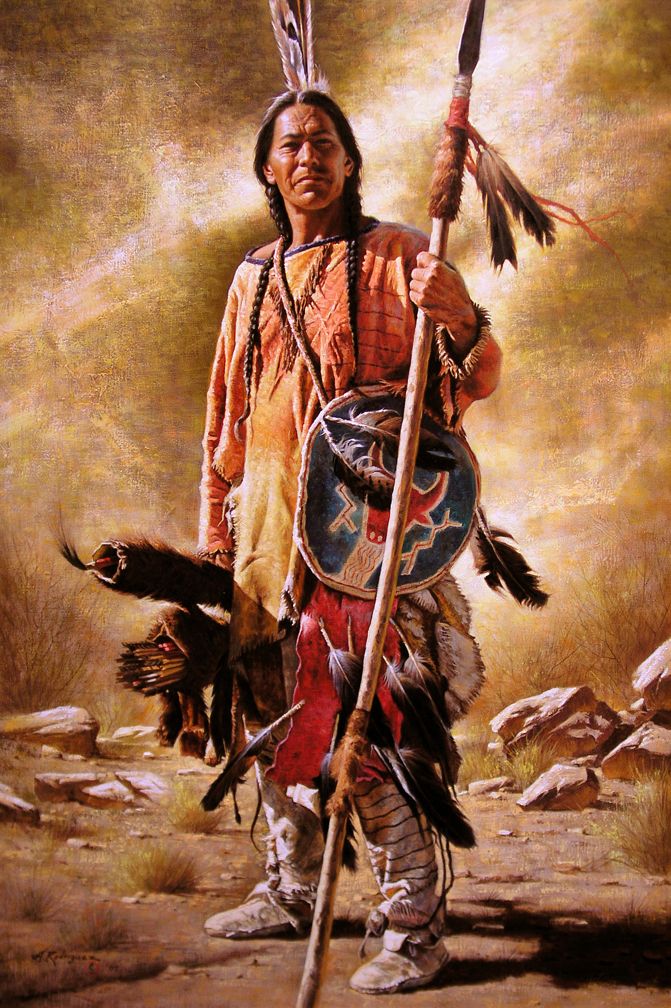

The importance of nature in Native American culture is a widely noted fact throughout history that continues to reign true to present-day. The natural world permeates all aspects of American Indian life—religion, daily rituals, mythology, writings, food, medicine, art, and so much more. Their way of life goes hand in hand with the land and environment.

The natural world permeates all aspects of American Indian life—religion, daily rituals, mythology, writings, food, medicine, art, and so much more. Their way of life goes hand in hand with the land and environment.

Once you understand the crucial role that nature plays in Native American culture, it’s easy to understand how and why it has become so prominent in all forms of art they create. We’ve put together a brief but comprehensive overview about how nature shapes and defines the world of indigenous peoples.

Having this knowledge is an insightful and effective way to dive into—and fully appreciate—the unique and fascinating world of Native American art.

Native Americans hold a deep reverence for nature.

American Indian culture respects nature above all else. The concept is significantly intertwined with the society’s beliefs regarding spirituality, both of which act as vital defining aspects of their understanding and way of life.

Native Americans operate under the conviction that all objects and elements of the earth—both living and nonliving—have an individual spirit that is part of the greater soul of the universe. This principle adheres to a religion called Animism, which is categorized by the belief in and worship of this overarching spirituality.

Theories of Animism extend to all living and natural objects, as well as nonliving phenomena. This would include humans, plants, and animals, as well as elements and geographic features like a river, mountain, or thunderstorm. Native American culture is fiercely devoted to respecting and honoring the spirit of the land and everything with which it provides them.

There was no science in the development of the culture.

While there are many conflicting stories and debates that still occur regarding the origin of the Earth, science is generally the field we turn to for answers on how the world works and how certain realities came to be. The process of photosynthesis may now be a well-understood and generally accepted explanation for plant growth, but to Native Americans a growing flower was a gift from the land imbued with a spirit of its own.

The process of photosynthesis may now be a well-understood and generally accepted explanation for plant growth, but to Native Americans a growing flower was a gift from the land imbued with a spirit of its own.

American Indians of the past—and many still today—turn to nature to explain phenomena that cannot be fully understood. The world and its natural elements, to them, were controlled by spirits. Therefore, they began to worship animals, plants, wind, water, etc.

All Native American culture can determine for sure is that life is sacred, and it comes from the land, which implies that Mother Earth is also divine. This notion clearly colors every work of art they produce.

All elements of nature are endowed with higher meaning.

Features of nature are symbolic and multi-functional in the American Indian universe—making them valuable and pervasive in everything they practice and cultivate. Native Americans derive power and strength through totems and understand and communicate with the world through the symbols that forge their writings and artwork. If symbols are their words, then nature is the dictionary.

If symbols are their words, then nature is the dictionary.

Trees, for example, represent more than just a source of life and healing; their spirit emanates permanence and longevity. Even different types have different purposes. The Cherry tree symbolizes rebirth and compassion and helps with digestion, while the Elm is integral to gaining wisdom and strength of will and can provide a salve for wounds.

The Animal Spirit is another form through which nature weaves itself indispensably through Native American beliefs and customs. Individuals often have a particular animal whose spirit they connect with—a guide that strongly shapes who they are and how they live. Similarly, groups often identify Spirit Animals that serve as Tribe Totems, animals that are most influential and prevalent in the area of each specific tribe and provide important resources and spiritual insights to navigate through life.

The Bat, for example, is the guardian of the night, signaling death and rebirth, while the Turtle guards Mother Earth and conveys tenacity. The Wolf serves as the Pathfinder, guiding with the spirit of leadership and intelligence.

The Wolf serves as the Pathfinder, guiding with the spirit of leadership and intelligence.

To Native American culture, nature is the foundational anchor off of which all life and spirit is built. The emergence of this belief through art is what often sets Native American artists apart from their contemporaries and allows their pieces to more easily connect with a wider audience. Fully grasping just how integral nature is to their culture provides observers with a much deeper comprehension of and appreciation for the meaningful, one-of-a-kind works American Indian artists produce.

Head on over to the Faust Gallery to put your newfound perception into action! We proudly exhibit, house, and sell a variety of works from the most talented American Indian artists in the country—each piece an object of nature with a radiant spirit of its own.

filed under: Native American Culture, Nature in American Indian Art

Tags: Native American Beliefs About Nature, Native American Religion, Nature in Native American Culture, Nature Symbols in American Indian Art

Mamihlapinatapai, the hardest word to translate

- Anna Bitong

- BBC Travel

Image copyright MARTIN BERNETTI/Getty Images

There is only one person left in the whole world who speaks fluent Yaghan. When Cristina Calderon dies, this ancient language may preserved only one word, which is very difficult to translate accurately, but which is loved by the whole world.

When Cristina Calderon dies, this ancient language may preserved only one word, which is very difficult to translate accurately, but which is loved by the whole world.

I reached the end of the world in spring. Mid-September was cold, and on that day in Argentinean Ushuaia, the southernmost city on Earth, it was raining.

However, while I was wandering through the Tierra del Fuego National Park, the sky cleared up, the sun reflected off the waters of the glaciers, the snow-covered mountain peaks shone with snow-white purity.

In 1520, the Portuguese-Spanish navigator Ferdinand Magellan must have contemplated a similar sight when his flotilla approached these shores.

He led his ships through the strait (later named after him) that separates the South American mainland and the windswept archipelago, which the traveler called Tierra del Fuego, because he noticed several fires on the shore.

- Why is it so rare to say "I", "me", "mine" in South Korea

- Finland: a country with the wrong name

- Why do Lithuanians have such respect for bees

- Why do the Dutch always say what they think

For millennia, the indigenous people, the Yagan Indians, had a custom of burning fires to keep warm, and also in order to transmit different signals to each other with their help.

The flame could be seen in the middle of the forest, and in the mountains, and in the valleys, and on the banks of the rivers, and even on the long canoes of the Yagans.

16 years ago, Cristina Calderón started the tradition of lighting three bonfires every year at Playa Larga in Ushuaia, where the ancient yaghans used to gather on various occasions. Christina is one of about 1,600 Yaghan descendants still living in the area.

It takes place on November 25 and is dedicated to the Yaghan tradition of lighting three bonfires in honor of a fish feast where anyone could eat.

With the help of smoke signals, the whole tribe was convened for the holiday - it was customary to share food and have a bite to eat together right on the shore.

"Bonfires are much more than just a way to keep warm in the cold and hostile climate of this corner of our planet," Victor Vargas Filgueira, a guide at the World's End Museum in Ushuaia, told me. "They inspired people to do all sorts of things." .

"They inspired people to do all sorts of things." .

Photo copyright Andres Camacho/Municipality od Ushuaia

Photo captionArgentinean Ushuaia is considered the southernmost city in the world

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

End of Story Podcast

One of those "things" is a word that has a lot of fans. A word that awakens the imagination and makes you think about many other phenomena of our life.

Mamihlapinatapai - a word from the almost extinct Yagan language. In the interpretation of our guide, "this is a moment of common thought by the fire ( pusakí in Yaghan), when the older generation passes on their experience, their history to their grandchildren. At this moment, everyone sits quietly."

At this moment, everyone sits quietly."

However, since the 19th century this word has a slightly different meaning - understandable to people from any country.

After Magellan discovered Tierra del Fuego, travelers and missionaries rushed here. In the 1860s, the British linguist Thomas Bridges settled in Ushuaia and spent 20 years living among the Yagans and compiling a Yagan-English dictionary, which included about 32,000 words and expressions.

A translation of mamihlapinatapai (different from Victor Vargas' version) first saw light in Bridges' essay: "Looking at each other, hoping that the other person will offer to do something that both of them very much desire, but neither of them wants to be first."

Photo copyright, Anna Bitong

Photo caption, Magellan named the archipelago Tierra del Fuego after seeing the fires of yagans on the shore0080 , "awkward", from which are formed ihlapi-na , "feel awkward"; ihlapi-na-ta , "cause embarrassment"; and mam-ihlapi-na-ta-pay , which means “to make them feel awkward together,” if translated literally, explains Yoram Meros, one of the few linguists in the world who studies the Yaghan language. - And Bridges' translation of mamihlapinatapai is more free, idiomatic. his dictionary, on which he worked, but did not finish, because in 1898 year died.

- And Bridges' translation of mamihlapinatapai is more free, idiomatic. his dictionary, on which he worked, but did not finish, because in 1898 year died.

"Perhaps he heard this word once or twice - in that context - and therefore wrote down such a translation of it, not knowing about its wider meaning," says Meros. - Bridges knew Yaghan better than any European of his time, yes and ours too. However, he was prone to exotic interpretations and in his translations sinned with verbosity.

Accurate or not, Bridges' translation of mamihlapinatapai was enthusiastically received by all lovers of exotic expressions, and this enthusiasm has survived to this day.

"The word became popular around the world thanks to Bridges, whose essay has been cited many times in English-language sources," notes Meros.

Image copyright, London Stereoscopic Company/Getty Images

Image caption, Indigenous Indian tribes have inhabited Tierra del Fuego for thousands of years. Films, music, art, literature have given the word a romantic meaning, many authors are in awe of its ability to capture and contain such a difficult moment in relationships between people.

Films, music, art, literature have given the word a romantic meaning, many authors are in awe of its ability to capture and contain such a difficult moment in relationships between people.

In 1994, the Guinness Book of Records named mamihlapinatapai the most capacious word in the world.

"The meaning of the word is beautiful," says one girl in a 2011 documentary that describes a day in the lives of people around the world.

"It could be two chieftains who were thinking about how to achieve peace between their tribes, but neither of them wanted to start first. Or it could be a guy and a girl who met at a party, but neither she nor he I had the courage to take the first step towards my feelings."

But what the word mamihlapinatapai really meant for the Yagans, most likely, will remain a mystery.

Cristina Calderon is now 89 years old, she is the last person on Earth who speaks fluent Yaghan. She was born on the Chilean island of Navarino, across the strait from Ushuaia, and began learning Spanish only at the age of nine.

She was born on the Chilean island of Navarino, across the strait from Ushuaia, and began learning Spanish only at the age of nine.

Meros visited Calderon several times, asking her to help translate texts and audio recordings into Yaghan. However, when he asked her about the meaning of mamihlapinatapai , she said she didn't know that word.

"Throughout her life, Calderón hasn't had much opportunity to talk to people in Yaghan," Meros explains. "The fact that she can't remember a word doesn't mean anything."

Image copyright, MARTIN BERNETTI/Getty Images

Image caption,Cristina Calderon (pictured left) is the last person on Earth who speaks fluent Yaghan

Could it be that this ancient language will soon be left in world culture? just one word?

"It used to be called a dying language," says Meros. "Now they talk about it more optimistically - especially the Yaghans themselves. There is hope that the language will be revived. "

"

- How a dying language in Japan is being revived in Brazil

Calderón and her granddaughter Cristina Sarraga give occasional open lessons in Yaghan in Puerto Williams, a port town on the island of Navarino, not far from the birthplace of the now 89-year-old Cristina Calderón .

Her children became the first generation of Yaghan who grew up speaking Spanish, because at that time those who spoke Yaghan were ridiculed.

Recently, however, the Chilean government decided to support the use of indigenous languages, and now Yaghan is taught in kindergarten in these parts.

"It's great to have a person nearby for whom Yaghan is native," Meros says of Calderon. "I always have so many questions for her."

Image copyright MARTIN BERNETTI/Getty Images

Image captionCalderón works with professional linguists to preserve his mother tongue

Many difficulties in learning and understanding Yagan stem from the fact that the life of the indigenous population in the old days was intertwined with nature.

Meros recalls how Calderon described the flight of birds, using one verb for a solitary bird and another for the flight of a flock. Similarly, different verbs are used for one and several canoes.

There are different words to describe the process of eating: there is a verb for eating in general, there is a separate word for "eat fish" and a completely different word for "eat seafood," says Meros.

In the 19th century, when Yagan contacts with Europeans became frequent, new diseases brought from other continents led to a reduction in the indigenous population. The Yagans lost part of their lands, and settlers from Europe settled in Tierra del Fuego.

Vargas' great-great-grandfather was one of the last Yagans who lived as a tribe. He fished in a canoe, warmed himself with his fellow tribesmen by the fire. In many ways, it was the memory of him that inspired Vargas to write the book "My Yaghan Blood".

Vargas recalls listening to the language spoken by the older generation of his family. "They spoke slowly, in short sentences, with frequent pauses. We can say a lot with a few words."

"They spoke slowly, in short sentences, with frequent pauses. We can say a lot with a few words."

Photo copyright, Anna Bitong

Photo caption,Understanding the Yaghan language for modern people is further complicated by how the indigenous peoples of South America interacted with nature

the Beagle Strait separating Ushuaia and Navarino Island.

It's always very windy here. On small islands there are many representatives of the local fauna. Black and white Magellanic penguins, along with orange-billed Gentoo penguins, roam the beach in the Martillo Island Reserve, ignoring the people standing nearby. Sea lions and fur seals sprawled on the shore in picturesque poses.

Vargas kindles fires in designated areas and, as he believes, feels what can be called a real mamihlapinatapai.

"I have experienced this many times when I was sitting around a fire with friends," he says.

Read the original English version of this article at BBC Travel .

How does language affect the picture of the world?

Breaking news

The best works of the Film Science!

The best works of the Film Science!

Evgenia Shmeleva

Why do Finnish children learn about their gender later than Jewish ones, how does the Pirahan tribe manage without numbers, and the Amondava without concepts of time?

Why do Finnish children learn about their gender later than Jewish ones, how does the Pirahan tribe manage without numbers, and the Amondava without concepts of time?

Scientists use experiments to prove differences in the thinking of people who think in different languages. Human ideas about time, space, causal relationships, relationships with other people are formed from childhood, and if your language does not have numbers or names of colors, ideas about the past and future, landmarks left and right, then these concepts are unlikely to be included in your picture of the world.

Perception of time

There are 12 tenses in English, and the word "time" is in the top of the most frequently used words, but there are people on earth who have no concept of time at all. These are, for example, the Amondava Indians living in the Amazon jungle. As shown by a recent study by Brazilian and British scientists, amondawas do not have any words for days, months, years and other periods. All changes in life - the transition to another social status or their growing up - they denote by changing their own names.

Time can neither be caught nor touched, but many peoples have learned to make it more concrete, associating it with spatial characteristics: as a rule, the future is ahead of us, and the past is behind. In the course of experiments, scientists have proven that an English-speaking person subconsciously leans forward when thinking about the future, and back when thinking about the past. The representative of the Bolivian Aymara Indians behaves exactly the opposite: talking about the past makes him lean forward, and talking about the future back. This is due to the fact that the future is unknown, it is invisible, like what is hidden behind us. The past is clearly visible, like everything that is before our eyes.

This is due to the fact that the future is unknown, it is invisible, like what is hidden behind us. The past is clearly visible, like everything that is before our eyes.

Researchers of the Amondawa Amazons were surprised to note their complete lack of spatial means to indicate the passage of time. If in our picture of the world there is a Monday, which we grieve, and a Friday, which we rejoice, then in the picture of amondava, time seems to be frozen, it does not run and does not flow, it just exists. Try complaining to an aboriginal about the lack of time, and you will feel what the difference in mentality is.

Perception of space

Most of the world's languages are self-centered. People constantly use the pronoun "I" and describe the location of objects and people relative to themselves, using the words "in front", "behind", "right", "left". A completely different spatial picture of the world belongs to the Australian Guugu Yimitir tribe, which lives in Queensland. They do not know the concepts of "left" and "right", but are guided exclusively by the cardinal points. In order for the interlocutor to understand you, you need to determine where the north is and where the south is, and say: “The ant is crawling along the western leg” or “The plate is in the southeast of the cup.” Instead of a greeting, it is supposed to ask: “Where are you going?”, And even a five-year-old child can immediately name the direction.

They do not know the concepts of "left" and "right", but are guided exclusively by the cardinal points. In order for the interlocutor to understand you, you need to determine where the north is and where the south is, and say: “The ant is crawling along the western leg” or “The plate is in the southeast of the cup.” Instead of a greeting, it is supposed to ask: “Where are you going?”, And even a five-year-old child can immediately name the direction.

According to linguists, about a third of the world's languages use absolute landmarks - cardinal points - to designate space. This can create difficulties for those who are just learning the language. So, there is a case with a little boy on the island of Bali in Indonesia, who was sent to dance in another village. However, a week later the dancer returned with nothing. The teacher's commands - "take a step to the south" or "raise your western hand" - he simply could not follow, as he lost his bearings in an unfamiliar area. Adults, according to scientists, navigate the terrain much better.

Adults, according to scientists, navigate the terrain much better.

Time and space

Professor of psychology at Stanford University, Lera Boroditsky, conducted an interesting experiment: she asked native speakers of different languages to lay out cards that depicted a process stretched over time: eating a banana, growing a crocodile, aging a person. Each participant did the procedure twice, being in different positions relative to the cardinal points. The results surprised. So, English speakers always laid out cards from left to right, Hebrew speakers - from right to left, according to the way they used to write or read. In the case of the Australian Aborigines from Pormpurow, who speak the Tayore language, writing did not matter. Regardless of their own position in space, they arranged the cards in the direction from east to west. At the same time, they were guided by themselves: scientists did not give them any clues.

A language without numbers

While progressive humanity has developed a multi-valued system of numbers, there is a language in the world that is completely devoid of numbers.

The language of the Pirahão tribe living in Brazil in the state of Amazonas surprised the researcher Daniel Everett so much that he lived among this people for 30 years and turned from a missionary into an atheist and a linguistic professor. There are no numbers and numerals in the Pirahan language, the Indians manage with the concepts of “several” (one to four pieces) and “many” (more than five), while it is impossible for them to explain what “one” means - this is outside their worldview. Scientists note that for the first time they encountered a language in which, in principle, there are no exact quantitative indicators for measuring something.

Pirahãs, like Amondavas, have no concept of time. The past does not matter to them, as does the future: they do not make any food supplies, live "here and now" and avoid sleep in every way, because they believe that sleep is harmful, changes a person and makes him weak. Their language is very primitive, characterized by a limited vocabulary, it has only seven consonants and three vowels. His colleague Steven Pinker called Everett's study "a bomb thrown at a party": for the first time, a language was found that completely contradicts the generally accepted theory of Noam Chomsky about the universal grammar of the world's languages.

His colleague Steven Pinker called Everett's study "a bomb thrown at a party": for the first time, a language was found that completely contradicts the generally accepted theory of Noam Chomsky about the universal grammar of the world's languages.

Colors

The Pirahão language has no symbols for colors. They say about red color "like blood", about black - "dirty blood", and instead of "green" and "blue" - "yet immature". On the island of Rossela in Papua New Guinea, the isolated Papuan language Yele has survived. It does not contain the concept of “color” and specific names for shades; people talk about colors using metaphors. Red is denoted by the word "mtjemte", from the breed of red parrots - "mte". Black - "mgidimgidi", from the word "night" - "mgidi". About a white-skinned person, the Papuan will say: "The skin of this person is white, like a parrot."

It has been found that people whose language contains the names of colors and shades better perceive differences in colors. For example, the Zuni, a Pueblo Indian people of the southwestern United States, do not have separate names for orange and yellow, so the Zuni find it difficult to talk about these colors as different. The Russian language has two words for shades of blue: "blue" and "blue" - which allows us to distinguish between these two colors better than the British.

For example, the Zuni, a Pueblo Indian people of the southwestern United States, do not have separate names for orange and yellow, so the Zuni find it difficult to talk about these colors as different. The Russian language has two words for shades of blue: "blue" and "blue" - which allows us to distinguish between these two colors better than the British.

By the way, the Zuni have a colored cosmological model of the world: each direction of light is colored in a certain shade for them. The north is yellow, the south is red, the west is blue, the east is white, the zenith (the “up” direction, and above it the four upper worlds) is multicolored, and the nadir (the “down” direction and below it the four lower worlds) is black.

Who is to blame?

If a vase is broken, the Englishman will say: "John broke the vase", while the Japanese and Spaniards will most likely formulate differently: "The vase is broken." In 2010, Boroditskaya and her colleagues conducted an experiment: speakers of English, Spanish and Japanese were shown video clips of two people piercing balloons, breaking eggs and spilling liquids: in some cases by accident, in others on purpose. Respondents were asked to remember who exactly was responsible for the incident. Speakers of all three languages described intentional events using “accusatory” constructions (“It was he who pierced the balloon”) and remembered the perpetrators of the incident equally well. However, recalling random incidents, the Spaniards and Japanese were less likely than the British to name the culprit.

Respondents were asked to remember who exactly was responsible for the incident. Speakers of all three languages described intentional events using “accusatory” constructions (“It was he who pierced the balloon”) and remembered the perpetrators of the incident equally well. However, recalling random incidents, the Spaniards and Japanese were less likely than the British to name the culprit.

What picture of the world does native speakers have with this structure? Boroditskaya argues that there is a connection between the focus of the English language on the protagonist and the desire of US law enforcement to punish offenders rather than help victims.

Gender and gender

Language affects not only the picture of the world, but also a person's perception of himself. University of Michigan researcher Alexander Giora in 1983 observed groups of children who spoke Hebrew, English, and Finnish. It turned out that Jewish children realize their gender a whole year earlier than Finnish ones (the British were somewhere in the middle). The scientist explains this by the peculiarities of linguistics: in Hebrew, gender is denoted in many ways, and even the word “you” differs depending on gender, while in Finnish the category of gender is absent in principle. English occupies an intermediate position.

The scientist explains this by the peculiarities of linguistics: in Hebrew, gender is denoted in many ways, and even the word “you” differs depending on gender, while in Finnish the category of gender is absent in principle. English occupies an intermediate position.

Words also have gender, and we are used to thinking about them with certain associations in mind. So, the bridge in Russian is masculine, and we associate it with masculine qualities: strong, durable, massive. And in German it is feminine - die Brücke, and native speakers are used to giving it other associations: graceful, virtuoso, elegant, etc. to understand why a turnip is she, and a girl or a girl is it. This linguistic paradox was ridiculed by Mark Twain in his article "On the Terrifying Difficulties of the German Language":

Gretchen. Wilhelm, where is the turnip?

Wilhelm. She went to the kitchen.

Gretchen. And where is the beautiful and educated English maid?

Wilhelm.