Mild anxiety disorders

What it is and How to Treat It

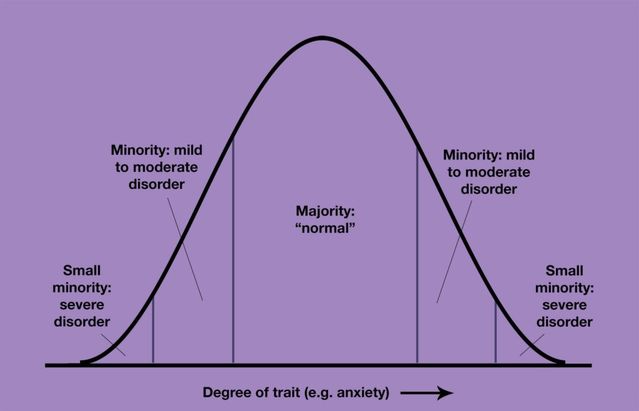

There are varying levels of anxiety, both subjectively and biologically. Some people deal with severe, debilitating anxiety that needs immediate medical intervention. Some people deal with moderate anxiety that drastically impacts their life but they're still able to live through every day. Others experience mild anxiety, which is something they can manage fairly easily but still makes their life more stressful.

Almost no one dealing with constant anxiety would describe their anxiety as "mild." Most people dealing with subjectively mild anxiety are unlikely to think they have anxiety at all. But what is mild anxiety anyway, and are there easier ways to overcome it?

A "Mild" Anxiety Disorder

It's easy for someone else to look at your anxiety and tell you it's "mild" compared to theirs.

But no matter what the results say, suffering from anxiety is always hard. No matter how mild or severe your anxiety is, it's always a struggle - otherwise, you wouldn't realize you had anxiety.

It is important to remember that if anxiety is hurting your quality of life, it deserves to be treated. Don't pay attention to labels like "mild" or "severe." If you suffer from anxiety and it bothers you, get help.

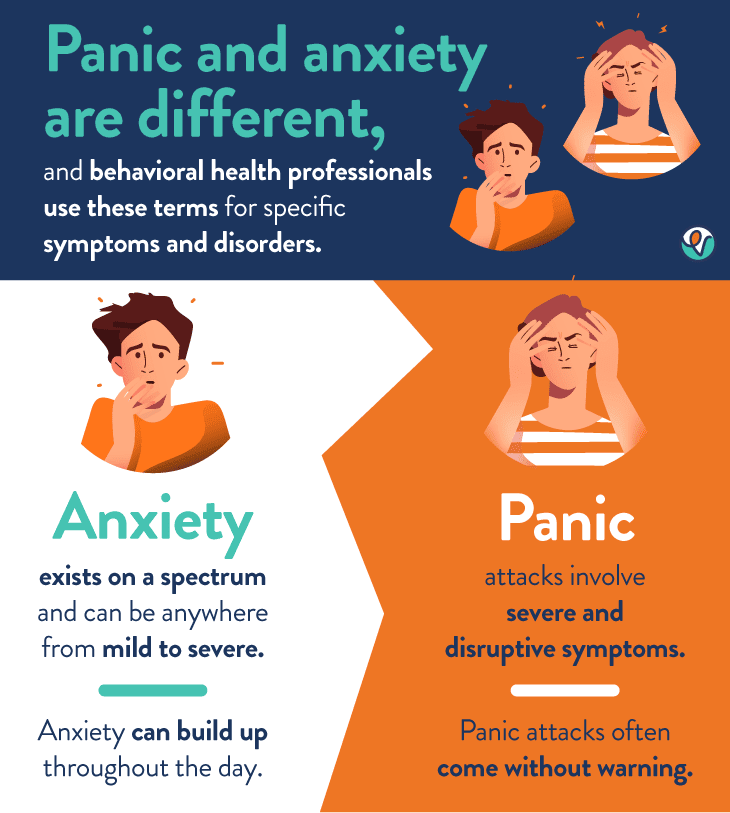

How to Describe Mild Anxiety

Mild anxiety is anxiety that is manageable without any additional techniques. By "manageable," we're not saying that it goes away easily. We're saying that you can still get through your day without panicking, you can enjoy a social life, and you can even find hobbies and activities fun. You may even think positively about the future.

Mild anxiety tends to be when you have irritating symptoms that don't seem to go away, but that otherwise doesn't control you. For example:

- You have constant worries but you can generally ignore them.

- You may feel nervous, nauseated, shaky, or sweat, but you aren't debilitated by these symptoms.

- You don't have panic attacks or become overwhelmed by your anxiety to the point where you start to fear the anxiety itself.

Mild anxiety is not unlike moderate anxiety, except that it tends to never or rarely reach that point of becoming truly overwhelming. It's more of a hassle that you simply cannot seem to control, and one that occasionally has spurts of severity that remind you that it's something you need to deal with.

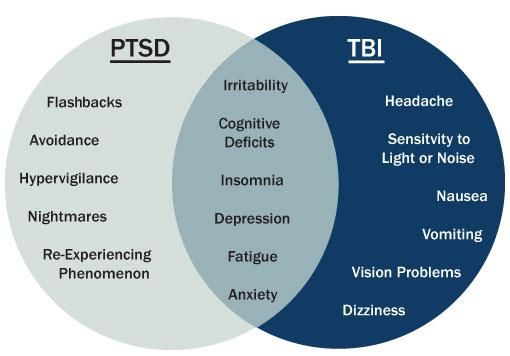

Many anxiety disorders can be mild as well. Panic attacks are rarely mild, but mild obsessive-compulsive disorder exists, as does mild generalized anxiety disorder and mild phobias. Post-traumatic stress disorder is a bit trickier, and mild social anxiety is actually fairly common and rarely considered a significant disorder.

All Anxiety Deserves to Be Treated

If your anxiety falls into the category of "mild," that doesn't mean that it's something you should ignore. Most anxiety starts out as mild before escalating as you get older, especially if you don't treat it. Also, anxiety is such a treatable condition that those that allow themselves to suffer from mild anxiety simply because it's not severe enough are needlessly hurting their quality of life.

Anxiety should always be treated. Mild anxiety should always be treated. Even anxiety that doesn't qualify as an anxiety disorder deserves attention. Anxiety is a negative emotion. If you were always sad or angry you would seek help, so there is no reason not to seek the same amount of help if you live with mild anxiety.

How to Fight Mild Anxiety

The only advantage to having mild anxiety over more severe anxiety is that those with mild anxiety are less likely to fear the symptoms of their anxiety in the way that those with severe anxiety do. That helps because severe anxiety attacks can set you back for your treatment in a way that those with mild anxiety shouldn't experience.

You may be able to control mild anxiety with simple lifestyle changes. Strongly consider the following:

- Exercise Regularly Even if you do nothing else, make sure that you are regularly exercising. Exercise is a powerful and important mental health tool. Exercise releases endorphins which calm your entire body.

It uses up adrenaline that is released when you are anxious and potentially burns away stress hormones. It tires out muscles to reduce your anxiety symptoms, and it reduces general physical stress, which studies have shown can decrease mental stress as well. Exercise is the most important thing you can do for your mild anxiety.

It uses up adrenaline that is released when you are anxious and potentially burns away stress hormones. It tires out muscles to reduce your anxiety symptoms, and it reduces general physical stress, which studies have shown can decrease mental stress as well. Exercise is the most important thing you can do for your mild anxiety. - Sleep, Diet, etc. While not quite as beneficial as exercise, general healthy living is also important. Remember that real science has proven that a stressed body can actually create worries and negative thoughts. Your mind and body are linked in a very real way. Getting enough sleep and eating healthier drastically reduce physical and mental stress, and can make coping with anxiety much easier.

- Learn Relaxation Strategies Counseling can still be very beneficial for those with mild anxiety. But for those that are hoping to avoid therapy, basic relaxation strategies may be enough. Try deep breathing, visualization, and progressive muscle relaxation to start.

Make sure you commit to them for at minimum two months. Contrary to popular belief, relaxation exercises do not work right away. They only work when you become used to doing them without overthinking the behaviors.

Make sure you commit to them for at minimum two months. Contrary to popular belief, relaxation exercises do not work right away. They only work when you become used to doing them without overthinking the behaviors.

These are extremely basic strategies for coping with mild anxiety, but they're generally effective ones and may be enough for those whose anxiety is otherwise manageable. Don't be afraid to also seek help if you need it.

Was this article helpful?

- Yes

- No

NIMH » Anxiety Disorders

Overview

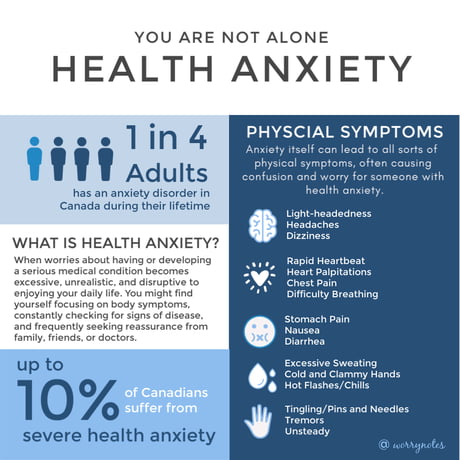

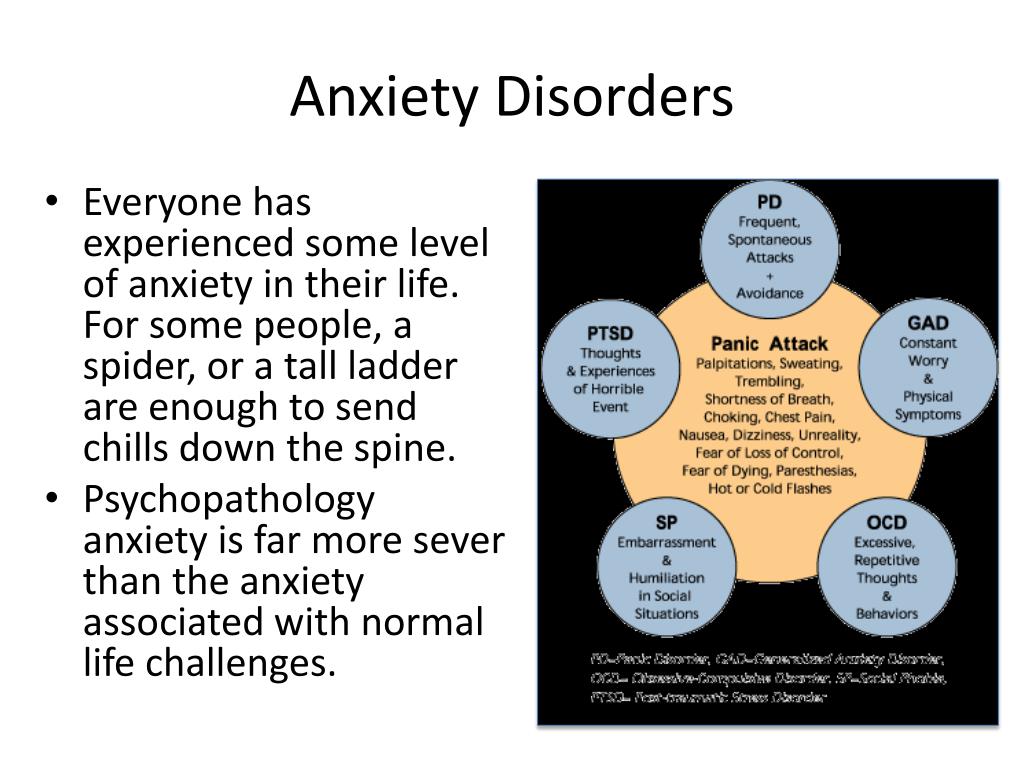

Occasional anxiety is a normal part of life. Many people worry about things such as health, money, or family problems. But anxiety disorders involve more than temporary worry or fear. For people with an anxiety disorder, the anxiety does not go away and can get worse over time. The symptoms can interfere with daily activities such as job performance, schoolwork, and relationships.

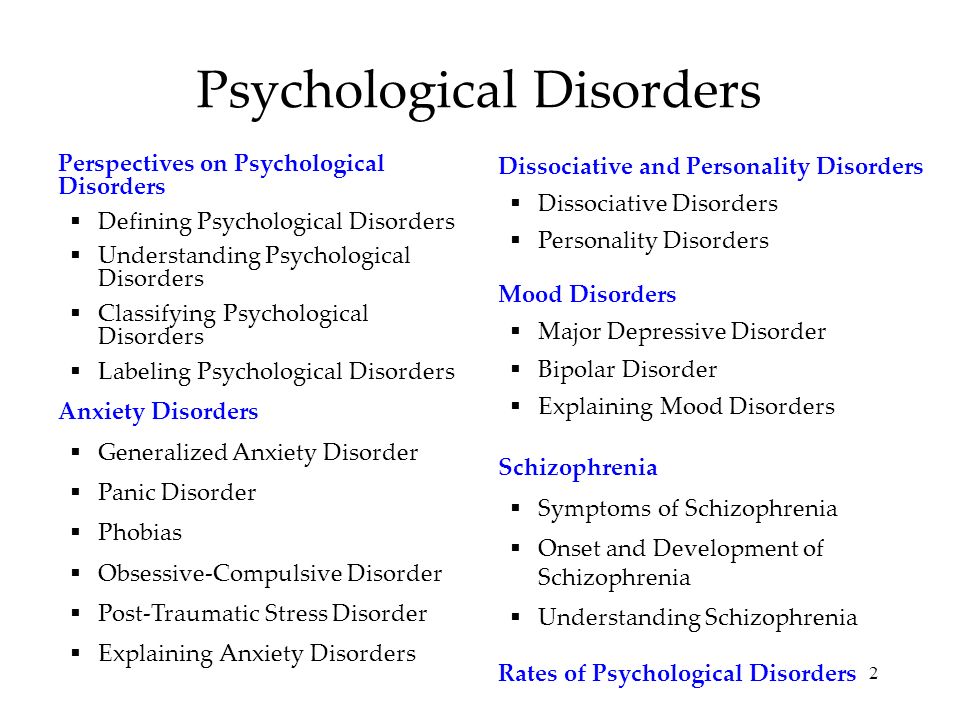

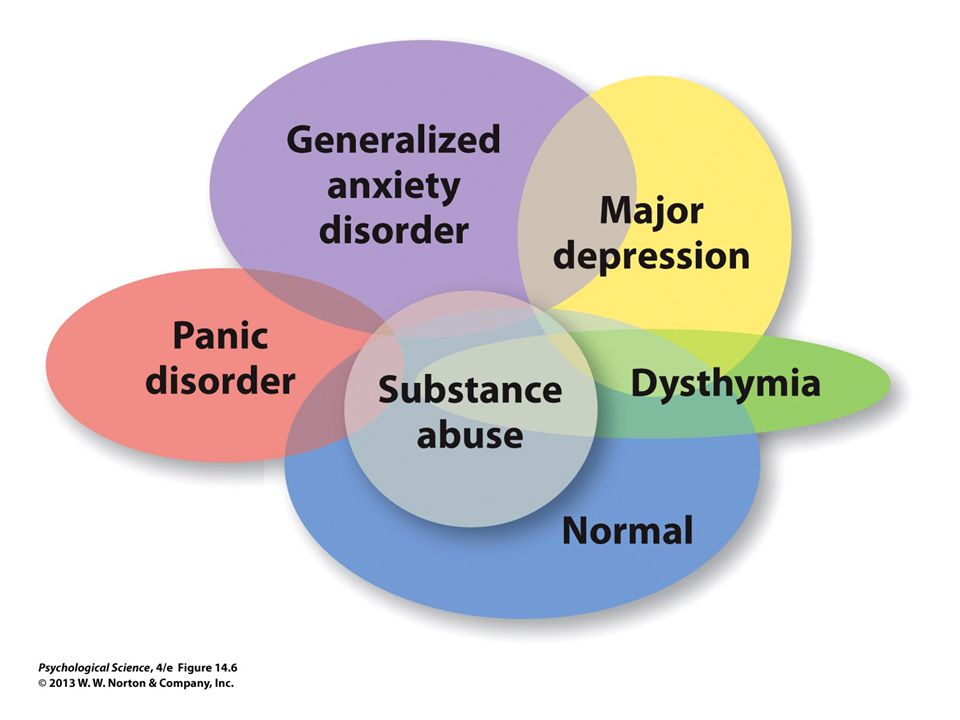

There are several types of anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and various phobia-related disorders.

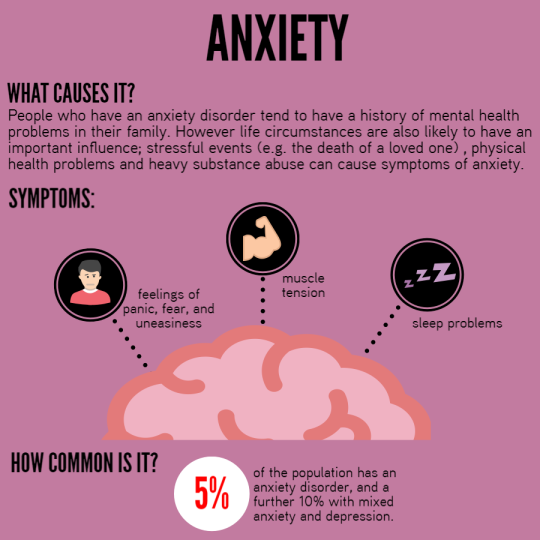

Signs and Symptoms

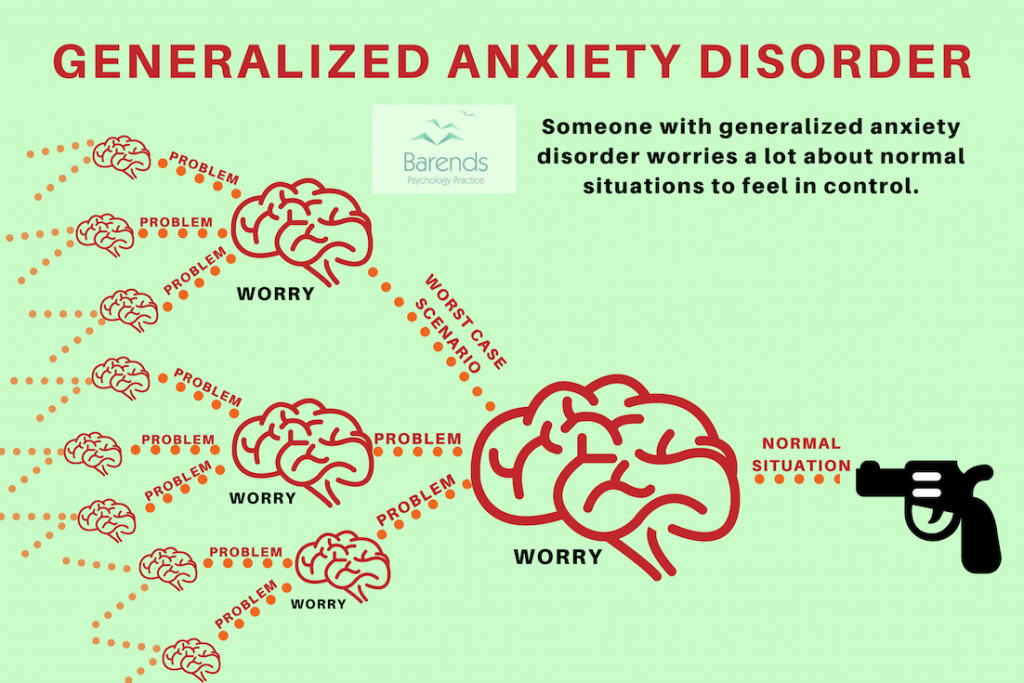

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) usually involves a persistent feeling of anxiety or dread, which can interfere with daily life. It is not the same as occasionally worrying about things or experiencing anxiety due to stressful life events. People living with GAD experience frequent anxiety for months, if not years.

Symptoms of GAD include:

- Feeling restless, wound-up, or on-edge

- Being easily fatigued

- Having difficulty concentrating

- Being irritable

- Having headaches, muscle aches, stomachaches, or unexplained pains

- Difficulty controlling feelings of worry

- Having sleep problems, such as difficulty falling or staying asleep

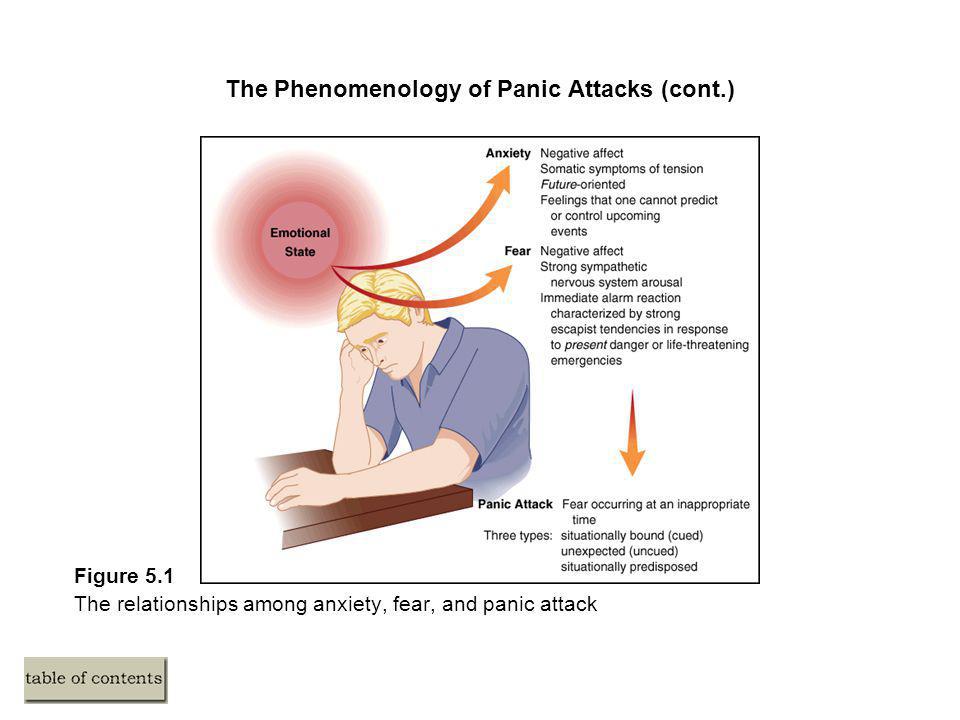

Panic Disorder

People with panic disorder have frequent and unexpected panic attacks. Panic attacks are sudden periods of intense fear, discomfort, or sense of losing control even when there is no clear danger or trigger. Not everyone who experiences a panic attack will develop panic disorder.

Panic attacks are sudden periods of intense fear, discomfort, or sense of losing control even when there is no clear danger or trigger. Not everyone who experiences a panic attack will develop panic disorder.

During a panic attack, a person may experience:

- Pounding or racing heart

- Sweating

- Trembling or tingling

- Chest pain

- Feelings of impending doom

- Feelings of being out of control

People with panic disorder often worry about when the next attack will happen and actively try to prevent future attacks by avoiding places, situations, or behaviors they associate with panic attacks. Panic attacks can occur as frequently as several times a day or as rarely as a few times a year.

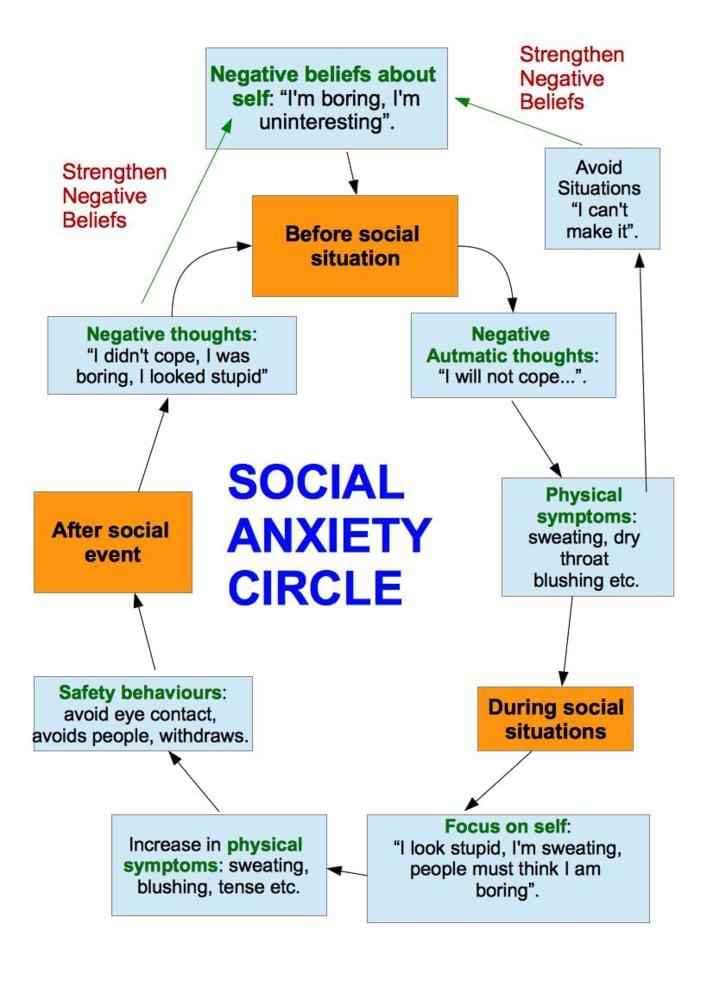

Social Anxiety Disorder

Social anxiety disorder is an intense, persistent fear of being watched and judged by others. For people with social anxiety disorder, the fear of social situations may feel so intense that it seems beyond their control. For some people, this fear may get in the way of going to work, attending school, or doing everyday things.

For some people, this fear may get in the way of going to work, attending school, or doing everyday things.

People with social anxiety disorder may experience:

- Blushing, sweating, or trembling

- Pounding or racing heart

- Stomachaches

- Rigid body posture or speaking with an overly soft voice

- Difficulty making eye contact or being around people they don’t know

- Feelings of self-consciousness or fear that people will judge them negatively

Phobia-related disorders

A phobia is an intense fear of—or aversion to—specific objects or situations. Although it can be realistic to be anxious in some circumstances, the fear people with phobias feel is out of proportion to the actual danger caused by the situation or object.

People with a phobia:

- May have an irrational or excessive worry about encountering the feared object or situation

- Take active steps to avoid the feared object or situation

- Experience immediate intense anxiety upon encountering the feared object or situation

- Endure unavoidable objects and situations with intense anxiety

There are several types of phobias and phobia-related disorders:

Specific Phobias (sometimes called simple phobias): As the name suggests, people who have a specific phobia have an intense fear of, or feel intense anxiety about, specific types of objects or situations. Some examples of specific phobias include the fear of:

Some examples of specific phobias include the fear of:

- Flying

- Heights

- Specific animals, such as spiders, dogs, or snakes

- Receiving injections

- Blood

Social anxiety disorder (previously called social phobia): People with social anxiety disorder have a general intense fear of, or anxiety toward, social or performance situations. They worry that actions or behaviors associated with their anxiety will be negatively evaluated by others, leading them to feel embarrassed. This worry often causes people with social anxiety to avoid social situations. Social anxiety disorder can manifest in a range of situations, such as within the workplace or the school environment.

Agoraphobia: People with agoraphobia have an intense fear of two or more of the following situations:

- Using public transportation

- Being in open spaces

- Being in enclosed spaces

- Standing in line or being in a crowd

- Being outside of the home alone

People with agoraphobia often avoid these situations, in part, because they think being able to leave might be difficult or impossible in the event they have panic-like reactions or other embarrassing symptoms. In the most severe form of agoraphobia, an individual can become housebound.

In the most severe form of agoraphobia, an individual can become housebound.

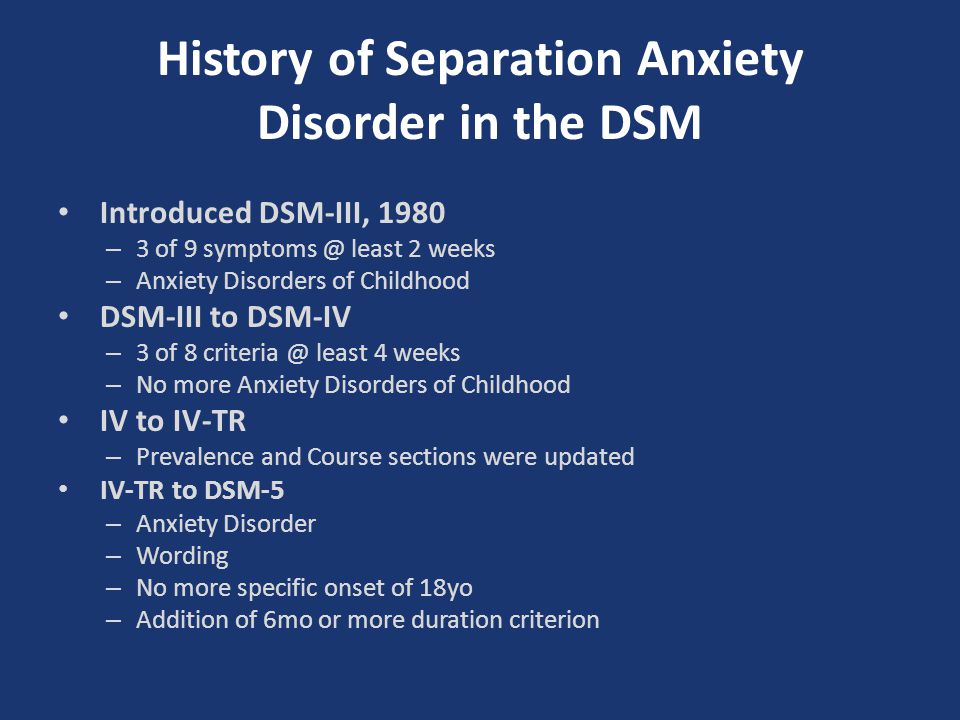

Separation anxiety disorder: Separation anxiety is often thought of as something that only children deal with; however, adults can also be diagnosed with separation anxiety disorder. People who have separation anxiety disorder have fears about being parted from people to whom they are attached. They often worry that some sort of harm or something untoward will happen to their attachment figures while they are separated. This fear leads them to avoid being separated from their attachment figures and to avoid being alone. People with separation anxiety may have nightmares about being separated from attachment figures or experience physical symptoms when separation occurs or is anticipated.

Selective mutism: A somewhat rare disorder associated with anxiety is selective mutism. Selective mutism occurs when people fail to speak in specific social situations despite having normal language skills. Selective mutism usually occurs before the age of 5 and is often associated with extreme shyness, fear of social embarrassment, compulsive traits, withdrawal, clinging behavior, and temper tantrums. People diagnosed with selective mutism are often also diagnosed with other anxiety disorders.

Selective mutism usually occurs before the age of 5 and is often associated with extreme shyness, fear of social embarrassment, compulsive traits, withdrawal, clinging behavior, and temper tantrums. People diagnosed with selective mutism are often also diagnosed with other anxiety disorders.

Risk Factors

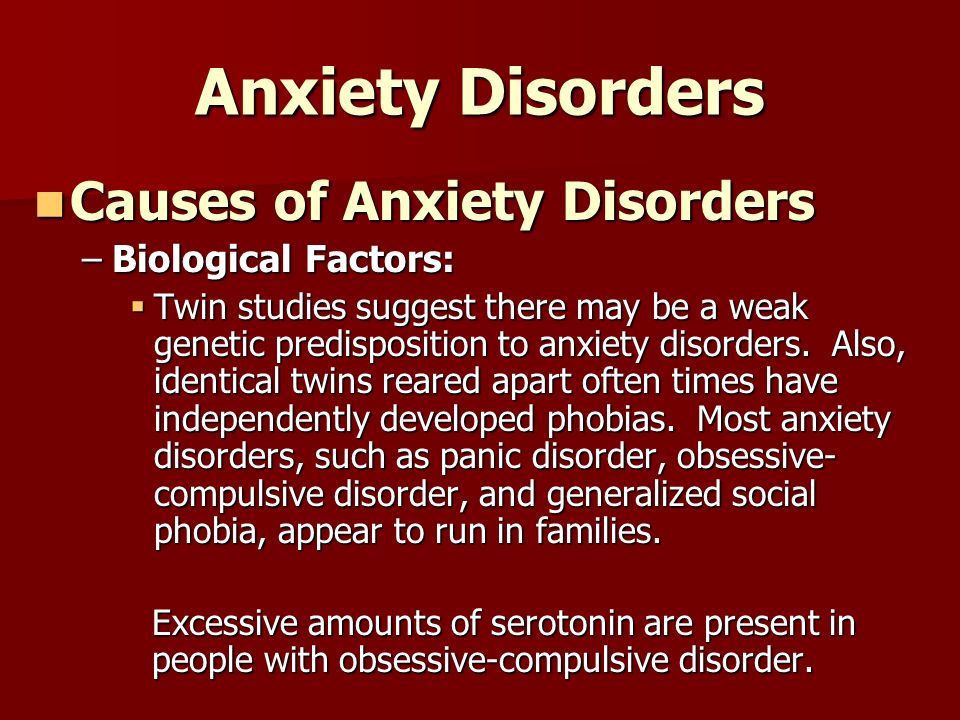

Researchers are finding that both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the risk of developing an anxiety disorder.

The risk factors for each type of anxiety disorder vary. However, some general risk factors include:

- Shyness or feeling distressed or nervous in new situations in childhood

- Exposure to stressful and negative life or environmental events

- A history of anxiety or other mental disorders in biological relatives

Anxiety symptoms can be produced or aggravated by:

- Some physical health conditions, such as thyroid problems or heart arrhythmia

- Caffeine or other substances/medications

If you think you may have an anxiety disorder, getting a physical examination from a health care provider may help them diagnose your symptoms and find the right treatment.

Treatments and Therapies

Anxiety disorders are generally treated with psychotherapy, medication, or both. There are many ways to treat anxiety, and you should work with a health care provider to choose the best treatment for you.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy or “talk therapy” can help people with anxiety disorders. To be effective, psychotherapy must be directed at your specific anxieties and tailored to your needs.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is an example of one type of psychotherapy that can help people with anxiety disorders. It teaches people different ways of thinking, behaving, and reacting to situations to help you feel less anxious and fearful. CBT has been well studied and is the gold standard for psychotherapy.

Exposure therapy is a CBT method that is used to treat anxiety disorders. Exposure therapy focuses on confronting the fears underlying an anxiety disorder to help people engage in activities they have been avoiding. Exposure therapy is sometimes used along with relaxation exercises.

Exposure therapy is sometimes used along with relaxation exercises.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Another treatment option for some anxiety disorders is acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). ACT takes a different approach than CBT to negative thoughts. It uses strategies such as mindfulness and goal setting to reduce discomfort and anxiety. Compared to CBT, ACT is a newer form of psychotherapy treatment, so less data are available on its effectiveness.

Medication

Medication does not cure anxiety disorders but can help relieve symptoms. Health care providers, such as a psychiatrist or primary care provider, can prescribe medication for anxiety. Some states also allow psychologists who have received specialized training to prescribe psychiatric medications. The most common classes of medications used to combat anxiety disorders are antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications (such as benzodiazepines), and beta-blockers.

Antidepressants

Antidepressants are used to treat depression, but they can also be helpful for treating anxiety disorders. They may help improve the way your brain uses certain chemicals that control mood or stress. You may need to try several different antidepressant medicines before finding the one that improves your symptoms and has manageable side effects.

They may help improve the way your brain uses certain chemicals that control mood or stress. You may need to try several different antidepressant medicines before finding the one that improves your symptoms and has manageable side effects.

Antidepressants can take several weeks to start working so it’s important to give the medication a chance before reaching a conclusion about its effectiveness. If you begin taking antidepressants, do not stop taking them without the help of a health care provider. Your provider can help you slowly and safely decrease your dose. Stopping them abruptly can cause withdrawal symptoms.

In some cases, children, teenagers, and adults younger than 25 may experience increased suicidal thoughts or behavior when taking antidepressant medications, especially in the first few weeks after starting or when the dose is changed. Because of this, people of all ages taking antidepressants should be watched closely, especially during the first few weeks of treatment.

Anti-anxiety Medications

Anti-anxiety medications can help reduce the symptoms of anxiety, panic attacks, or extreme fear and worry. The most common anti-anxiety medications are called benzodiazepines. Although benzodiazepines are sometimes used as first-line treatments for generalized anxiety disorder, they have both benefits and drawbacks.

Benzodiazepines are effective in relieving anxiety and take effect more quickly than antidepressant medications. However, some people build up a tolerance to these medications and need higher and higher doses to get the same effect. Some people even become dependent on them.

To avoid these problems, health care providers usually prescribe benzodiazepines for short periods of time.

If people suddenly stop taking benzodiazepines, they may have withdrawal symptoms, or their anxiety may return. Therefore, benzodiazepines should be tapered off slowly. Your provider can help you slowly and safely decrease your dose.

Beta-blockers

Although beta-blockers are most often used to treat high blood pressure, they can help relieve the physical symptoms of anxiety, such as rapid heartbeat, shaking, trembling, and blushing. These medications can help people keep physical symptoms under control when taken for short periods. They can also be used “as needed” to reduce acute anxiety, including to prevent some predictable forms of performance anxieties.

Choosing the Right Medication

Some types of drugs may work better for specific types of anxiety disorders, so people should work closely with a health care provider to identify which medication is best for them. Certain substances such as caffeine, some over-the-counter cold medicines, illicit drugs, and herbal supplements may aggravate the symptoms of anxiety disorders or interact with prescribed medication. People should talk with a health care provider, so they can learn which substances are safe and which to avoid.

Choosing the right medication, medication dose, and treatment plan should be done under an expert’s care and should be based on a person’s needs and their medical situation. Your and your provider may try several medicines before finding the right one.

Support Groups

Some people with anxiety disorders might benefit from joining a self-help or support group and sharing their problems and achievements with others. Support groups are available both in person and online. However, any advice you receive from a support group member should be used cautiously and does not replace treatment recommendations from a health care provider.

Stress Management Techniques

Stress management techniques, such as exercise, mindfulness, and meditation, also can reduce anxiety symptoms and enhance the effects of psychotherapy. You can learn more about how these techniques benefit your treatment by talking with a health care provider.

Join a Study

Clinical trials are research studies that look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions. The goal of clinical trials is to determine if a new test or treatment works and is safe. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge so that others may be better helped in the future.

The goal of clinical trials is to determine if a new test or treatment works and is safe. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge so that others may be better helped in the future.

Researchers at NIMH and around the country conduct many studies with patients and healthy volunteers. We have new and better treatment options today because of what clinical trials uncovered years ago. Be part of tomorrow’s medical breakthroughs. Talk to your health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you.

To learn more or find a study, visit:

- NIMH’s Clinical Trials webpage: Information about participating in clinical trials

- Clinicaltrials.gov: Current Studies on Anxiety Disorders: List of clinical trials funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) being conducted across the country

- Join a Study: Adults - Anxiety Disorders: List of studies being conducted on the NIH Campus in Bethesda, MD

- Join a Study: Children - Anxiety Disorders: List of studies being conducted on the NIH Campus in Bethesda, MD

Learn More

Free Brochures and Shareable Resources

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): When Worry Gets Out of Control: This brochure describes the signs, symptoms, and treatment of generalized anxiety disorder.

- I’m So Stressed Out!: This fact sheet intended for teens and young adults presents information about stress, anxiety, and ways to cope when feeling overwhelmed.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: When Unwanted Thoughts Take Over: This brochure describes the signs, symptoms, and treatment of OCD.

- Panic Disorder: When Fear Overwhelms: This brochure describes the signs, symptoms, and treatments of panic disorder.

- Social Anxiety Disorder: More Than Just Shyness: This brochure describes the signs, symptoms, and treatment of social anxiety disorder.

- Shareable Resources on Anxiety Disorders: Help support anxiety awareness and education in your community. Use these digital resources, including graphics and messages, to spread the word about anxiety disorders.

Multimedia

- Mental Health Minute: Anxiety Disorders in Adults:Take a mental health minute to watch this video about anxiety disorders in adults.

- Mental Health Minute: Stress and Anxiety in Adolescents: Take a mental health minute to watch this video about stress and anxiety in adolescents.

- NIMH Expert Discusses Coping with the Pandemic and School Re-Entry Stress: Learn about the causes or triggers of stress and coping techniques to help reduce anxiety and improve the transition back to school.

- NIMH Expert Discusses Managing Stress and Anxiety: Learn about coping with stressful situations and when to seek help.

- GREAT: Learn helpful practices to manage stress and anxiety. GREAT was developed by Dr. Krystal Lewis, a licensed clinical psychologist at NIMH.

- Getting to Know Your Brain: Dealing with Stress: Test your knowledge about stress and the brain. Also learn how to create and use a “stress catcher” to practice strategies to deal with stress.

- Guided Visualization: Dealing with Stress: Learn how the brain handles stress and practice a guided visualization activity.

- Panic Disorder: The Symptoms: Learn about the signs and symptoms of panic disorder.

Federal Resources

- Anxiety Disorders (MedlinePlus – also en español)

Research and Statistics

- Journal Articles: References and abstracts from MEDLINE/PubMed (National Library of Medicine).

- Statistics: Anxiety Disorder: This webpage provides information on the statistics currently available on the prevalence and treatment of anxiety among people in the U.S.

Last Reviewed: April 2022

Unless otherwise specified, NIMH information and publications are in the public domain and available for use free of charge. Citation of NIMH is appreciated. Please see our Citing NIMH Information and Publications page for more information.

Therapy of anxiety disorders: a modern view of the problem

Summary. The International Classification of Diseases-10 group of anxiety disorders includes generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, specific phobias, and social anxiety disorder (F40 and F41). Anxiety disorders are very common in the general population and occur in every 5th inhabitant of developed countries throughout life. One of the most difficult to treat in this group is Generalized Anxiety Disorder, characterized by excessive worrying about various events or activities, resulting in significant distress and disruption of social, work, and daily functioning. The use of antidepressants is ineffective in about ⅓ of these patients. In modern clinical guidelines, other groups of drugs are indicated in first and second line therapy - anticonvulsants, atypical antipsychotics. Among them, an important place is occupied by pregabalin, a drug of the anticonvulsant group, which is also used for chronic pain syndrome. The article considers the current state of the problem of treating anxiety disorders and (using pregabalin as an example) the feasibility of using alternative drugs to antidepressants.

Urgency

Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental health problems in the world. In addition, among all medical problems, anxiety also occupies a leading position in terms of prevalence. Within the framework of epidemiological studies, it is customary to talk about two variants of the prevalence of any condition - annual, that is, an assessment of this indicator in a small time slice (12-month prevalence), and lifelong - the proportion of people who have experienced this condition at least once. For the entire group of anxiety disorders, research has shown a 12-month prevalence of >15% and a lifetime prevalence of >20%.

As a clear demonstration of the relevance of the problem, we present the results of a large-scale study on the assessment of the mental and somatic health of US residents "National Comorbidity Survey". Along with Framingham, this is one of the largest observational studies, the results of which are often used to evaluate epidemiological data and the relationship between various factors that affect health. According to him, the 12-month prevalence of anxiety disorders is 17.2%, which means that every 6th person in the United States develops an anxiety disorder within one year. The lifetime prevalence is 24.9%; this means that every 4th person during his life at least once encounters an anxiety disorder (Kessler R.C. et al., 1994). These data are approximately the same for both Caucasians and African Americans. Thus, with a sufficiently high degree of accuracy, they can be extrapolated to the Ukrainian population.

According to him, the 12-month prevalence of anxiety disorders is 17.2%, which means that every 6th person in the United States develops an anxiety disorder within one year. The lifetime prevalence is 24.9%; this means that every 4th person during his life at least once encounters an anxiety disorder (Kessler R.C. et al., 1994). These data are approximately the same for both Caucasians and African Americans. Thus, with a sufficiently high degree of accuracy, they can be extrapolated to the Ukrainian population.

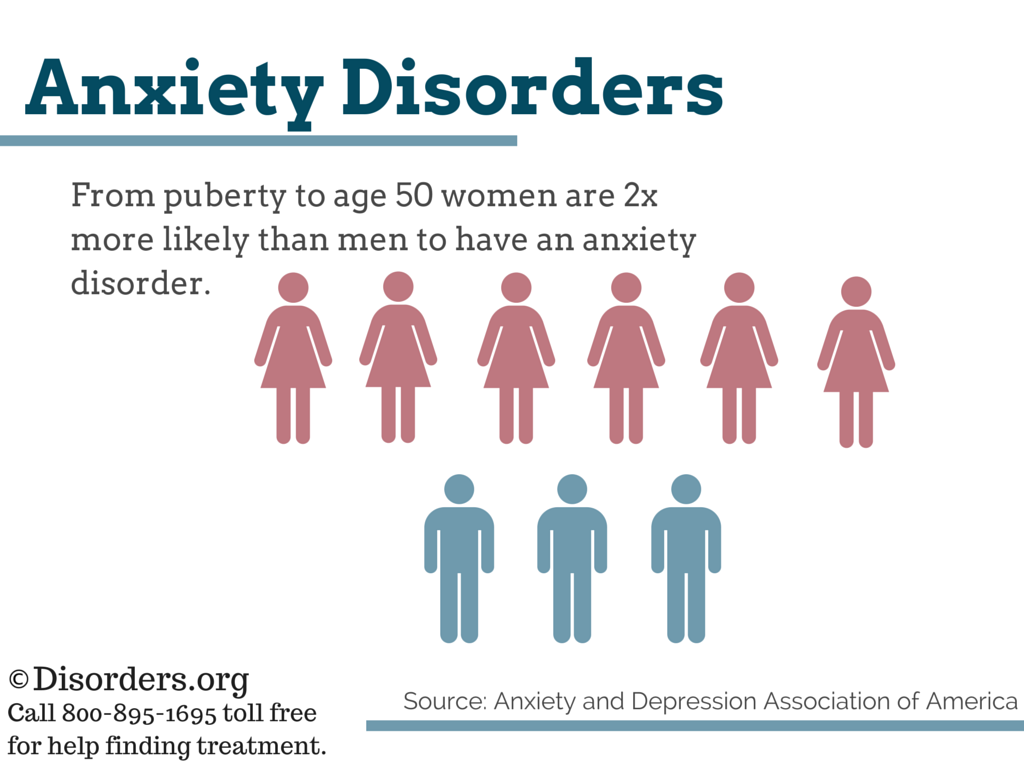

An analysis of World Health Organization data suggests that this group of mental health problems is the 6th most common cause of disability in both high-income, middle- and low-income countries, including Ukraine. For every 100 thousand inhabitants of the Earth, anxiety disorders account for 390 years of disability. Among women, anxiety disorders are responsible for 65% of all years of life lost (disabled) from all causes (Baxter A.J. et al., 2014).

Among anxiety disorders, a special place is occupied by generalized anxiety disorder, which is characterized by excessive anxiety and feelings in relation to a large number of events or activities (for example, work), accompanied by severe anxiety, fatigue, irritability, difficulty concentrating, muscle tension and impaired sleep. This state of affairs leads to significant distress and difficulties in social, work or even normal daily functioning. For example, anxiety significantly complicates the performance of work duties, which can lead to job loss or provoke conflict in the family.

This state of affairs leads to significant distress and difficulties in social, work or even normal daily functioning. For example, anxiety significantly complicates the performance of work duties, which can lead to job loss or provoke conflict in the family.

The sleep disturbance that often accompanies anxiety can be a serious problem in itself, as anxiety-induced insomnia is usually long-term and thus poorly controlled with benzodiazepines or their derivatives, as they are not recommended for long-term use. Another serious problem that deserves attention is a significant decrease in the quality of life of patients with anxiety. Given the gradual transition to patient-centered care, it is also recommended to use this indicator as a marker of the severity of the condition, in addition to standard diagnostic measures (clinical scales for assessing anxiety).

Studies have shown that anxiety is associated with a significant reduction in quality of life, especially when taking into account the widely used SF-36 quality of life scale. To a greater extent, the deterioration relates to the psychological and some characteristics of the somatic component of the quality of life. Thus, anxiety is associated with a deterioration in indicators on such a somatic scale as pain intensity. This may be due to the fact that patients with anxiety are often diagnosed with conditions associated with pain, such as chronic tension headache, nonspecific back pain, and a number of others. As an example, let's cite the results of a large-scale multinational survey, which also included Ukraine. According to the data obtained in our country, chronic pain has been noted in 19 patients over the past 12 months..7% of patients with anxiety or depression (Tsang A. et al., 2008). Thus, every 5th patient with an anxiety disorder also needs therapy aimed at eliminating pain.

To a greater extent, the deterioration relates to the psychological and some characteristics of the somatic component of the quality of life. Thus, anxiety is associated with a deterioration in indicators on such a somatic scale as pain intensity. This may be due to the fact that patients with anxiety are often diagnosed with conditions associated with pain, such as chronic tension headache, nonspecific back pain, and a number of others. As an example, let's cite the results of a large-scale multinational survey, which also included Ukraine. According to the data obtained in our country, chronic pain has been noted in 19 patients over the past 12 months..7% of patients with anxiety or depression (Tsang A. et al., 2008). Thus, every 5th patient with an anxiety disorder also needs therapy aimed at eliminating pain.

Evidence-based therapy

A rational approach to patient care includes both an individualized approach, taking into account the characteristics of each individual case, and reliance on the existing evidence base, including clinical guidelines, meta-analyses and the results of recent randomized controlled clinical trials.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), UK, is one of the well-known and leading providers of evidence-based clinical guidelines. In the latest guidelines on the quality standard of care for anxiety, a team of leading experts note that benzodiazepines and antipsychotics should be avoided in routine practice in patients with anxiety disorders (NICE, 2014). These recommendations are explained by the fact that taking the former is associated with the development of tolerance and dependence, and the latter with a relatively high risk of side effects. The authors recommend taking this into account, and if prescribed, then a short course in cases of exacerbation of symptoms, when other methods of treatment do not demonstrate sufficient effectiveness. Thus, antidepressants and/or cognitive-behavioral therapy are recommended as first-line therapy. For the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, in particular generalized anxiety disorder, NICE recommends selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and pregabalin. The authors of the guidelines note that one should also be aware of the possible withdrawal syndrome when using SSRIs and SNRIs, especially paroxetine and venlafaxine.

The authors of the guidelines note that one should also be aware of the possible withdrawal syndrome when using SSRIs and SNRIs, especially paroxetine and venlafaxine.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the American Psychiatric Association (APA) are other well-known organizations that compile guidelines for the treatment of mental disorders, offering the same psychological and pharmacological treatments. We are talking, in particular, about the guidelines for the diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety and panic disorder (AAFP, 2015) and the APA clinical guidelines (2009) only for panic disorder, which practically duplicate the above, however, the regimens for prescribing drugs and psychological methods of treatment are prescribed in more detail. The list of recommended drugs is presented in the table.

Table AAFP recommended drugs for first and second line therapy

for generalized and panic disorder

| Drug | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| SSRI | |

| Escitalopram | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Fluvoxamine | Panic disorder |

| Fluoxetine | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Paroxetine | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Sertraline | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| SNRI | |

| Duloxetine | Generalized anxiety disorder |

| Venlafaxine | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Azaperone | |

| Buspirone | Generalized anxiety disorder |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | |

| Amitriptyline | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Imipramine | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Nortriptyline | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Antiepileptic drugs | |

| Pregabalin | Generalized anxiety disorder |

| Antipsychotics | |

| Quetiapine | Generalized Anxiety Disorder |

In addition to the medical communities of Great Britain and the USA, we also note the World Federation of Biological Psychiatry, which brings together specialists from different countries. In 2012, based on a review of the evidence base, this organization also published clinical guidelines for the treatment of anxiety disorders. The authors separately identified for panic, generalized disorder and social anxiety drugs included in first-line therapy:

In 2012, based on a review of the evidence base, this organization also published clinical guidelines for the treatment of anxiety disorders. The authors separately identified for panic, generalized disorder and social anxiety drugs included in first-line therapy:

- for social anxiety: escitalopram, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine;

- for panic disorder: same drugs + citalopram and fluoxetine;

- for generalized disorder: escitalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, quetiapine, and pregabalin.

Particular attention in this list should be given to pregabalin, which belongs to the group of antiepileptic drugs. It should be noted that for a long time in the medical and pharmacological communities there has been a discussion of changing the existing approach to the classification of psychotropic drugs. Often the name of a group of drugs, such as antidepressants, antipsychotics (neuroleptics), or anticonvulsants (antiepileptic drugs), does not correspond to the diagnosis for which they are prescribed. So, antidepressants can be prescribed for anxiety, bulimia; antipsychotics - for anxiety, depression; anticonvulsants - for the same anxiety or bipolar affective disorder. Assigning a prescribed drug to any of these groups often confuses patients, which can be a cause for additional concern or reduced compliance. Discussion of the transition from the old classification model based on symptoms to the new one was one of the main topics of one of the largest annual world conferences on psychiatry and psychopharmacology "ECNP Congress" in 2014, 2015 and 2016, and it is possible that in the near future this new model will be implemented.

So, antidepressants can be prescribed for anxiety, bulimia; antipsychotics - for anxiety, depression; anticonvulsants - for the same anxiety or bipolar affective disorder. Assigning a prescribed drug to any of these groups often confuses patients, which can be a cause for additional concern or reduced compliance. Discussion of the transition from the old classification model based on symptoms to the new one was one of the main topics of one of the largest annual world conferences on psychiatry and psychopharmacology "ECNP Congress" in 2014, 2015 and 2016, and it is possible that in the near future this new model will be implemented.

Pregabalin differs in its chemical structure and mechanism of action from SSRIs and SNRIs, while remaining highly effective in generalized anxiety disorder, as evidenced by its inclusion as first-line therapy in various management guidelines for these patients. Pregabalin is a γ-aminobutyric acid derivative and was originally used and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of epilepsy and various types of chronic pain syndrome, including diabetic peripheral neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and fibromyalgia. Later, evidence began to emerge for its effectiveness in anxiety disorders, especially generalized anxiety disorder and, to a lesser extent, social phobia.

Later, evidence began to emerge for its effectiveness in anxiety disorders, especially generalized anxiety disorder and, to a lesser extent, social phobia.

Recently, this drug has increasingly become the subject of study specifically in the context of anxiety treatment as an alternative to SSRIs. The problem of the widespread use of the latter is mainly due to the relatively slow onset of action, the risk of withdrawal syndrome and the lack of a significant effect in relation to such often comorbid conditions as chronic pain syndrome of various origins. In addition, in about ⅓ of patients, the use of SSRIs and SNRIs does not lead to the desired effect and there is a need to look for another therapy with a different mechanism of action.

This was reflected in a systematic review of scientific studies conducted by the staff of the Villa San Benedetto Menni clinics in Rome, Maastricht University and the University of Miami. Summarizing the available evidence base for all drugs used in anxiety disorders, the researchers concluded that pregabalin is highly effective in generalized anxiety disorder. At the same time, as the authors note, the drug showed a low risk of adverse effects with long-term use and did not have a negative effect on cognitive or psychomotor functioning (Perna G. et al., 2016).

At the same time, as the authors note, the drug showed a low risk of adverse effects with long-term use and did not have a negative effect on cognitive or psychomotor functioning (Perna G. et al., 2016).

Also published this year are the results of an analysis of several randomized clinical trials that evaluated the effectiveness of pregabalin in the context of pain reduction and improvement in various areas of functioning. The authors note that taking pregabalin led to a significant reduction in pain, improved sleep quality and physical functioning. The analysis also assessed symptoms of anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). On the one hand, no significant differences were found with the control group (placebo), on the other hand, the study sample consisted of individuals with a low initial level of anxiety and depression, which did not reach the level of clinical significance (6 points each on the HADS anxiety and depression subscales at the threshold level ≥8 points and clinically significant ≥11 points) (Sadosky A. et al., 2016).

et al., 2016).

The problem of anxiety is also relevant for patients undergoing surgical treatment. This disorder often accompanies these patients both in the pre- and postoperative period. In addition, anxiety about the upcoming operation and pain has a negative effect on surgery and anesthesia. A new clinical trial conducted in 2016 demonstrated the effectiveness of pregabalin adjunctive therapy for bone surgery. In this study, patients of the experimental group were premedicated with pregabalin in different dosages before blockade of peripheral nerves. The control group did not receive any additional therapy. According to the results, the use of pregabalin significantly contributed to the maintenance of hemodynamic parameters during the intervention at a normal level and greater patient satisfaction with the quality of anesthesia. When using pregabalin at a dose of 150 and 300 mg, a significantly shorter duration of surgical intervention was also noted compared with the control (76. 5; 68.0 and 83.3 minutes, respectively).

5; 68.0 and 83.3 minutes, respectively).

Conclusions

Anxiety disorders are a common problem of our time, one of the main characteristics of which is a high comorbidity with both somatic and other mental disorders. The gradual discovery of new drugs and the study of additional properties of already long-term use has replaced benzodiazepines from the first-line therapy recommended in current guidelines for patients with anxiety disorders. Highly effective drugs are not limited to the SSRI and SNRI group; Today, there are other effective medicines classified as anticonvulsants and atypical antipsychotics. In particular, the study of the additional properties of pregabalin has demonstrated its high efficacy in generalized anxiety disorder, which is reflected in the most significant clinical guidelines and recommendations of the European Medical Agency. Experts conclude that pregabalin can be used as a first-line therapy for this disorder, and it may also be the best pharmacological alternative to SSRIs when they are ineffective or poorly tolerated. This drug occupies a special place in anxiety in patients with a neurological profile and those undergoing surgical interventions, since, in addition to the effect on anxiety, it reduces the intensity of pain and improves postoperative outcomes.

This drug occupies a special place in anxiety in patients with a neurological profile and those undergoing surgical interventions, since, in addition to the effect on anxiety, it reduces the intensity of pain and improves postoperative outcomes.

List of references

Address for correspondence:

Bezsheiko Vitaly Grigorievich

01030, Kyiv,

st. Mykhailo Kotsiubynskogo, 8A

Ukrainian Research Institute of Social and Forensic Psychiatry and Narcology

Anxiety and depressive spectrum disorders in patients with larynx disease

mononuclear phagocytes. The disease is quite rare in otorhinolaryngological practice: 0.9-2.7% of all vocal cord disorders in adults. A feature of the disease is the high frequency of relapses after surgical treatment. The insufficient knowledge of the etiology of the disease, its recurrent nature, the absence of predictors of recovery or possible recurrence, the need for repeated surgical interventions make laryngeal granuloma an urgent problem, the development of which requires an interdisciplinary approach [1].

The most common factors provoking granuloma growth include hyperfunctional use of the voice, intubation during surgical intervention in the larynx, and gastroesophageal reflux [2]. However, it should be noted that trauma to the larynx after surgical intubation has now become a rare provoking factor. In this regard, the term "laryngeal contact granuloma", widely used in the past, is mentioned less and less. The conventionality of classifying laryngeal granuloma as an organic disease was noted by P. Moses [3], who defined this disease as a "neurosis" of the vocal cords. He pointed out that "emotional conflicts often go hand in hand with this disease" and drew attention to the special role of anxiety. Other authors [4, 5] also noted the importance of personality traits (anankastic and depressive) and, in addition, alexithymia and low extraversion, and emphasized the role of such stress factors as work overload in the provocation of the disease. E. Mans et al. [6] believe that patients with granuloma can be attributed to the psychosomatic functional type, which is characterized by a special somatic tension during stress and an inability to analyze their emotions. The significance of stress factors in the framework of psychosomatic disorders is also noted by other researchers [7].

The significance of stress factors in the framework of psychosomatic disorders is also noted by other researchers [7].

The considered points of view correspond to modern ideas about chronic stress. It is known that it leads to pro-inflammatory shifts in the immune system, creating conditions for the development of both chronic inflammatory processes and depressive and anxiety disorders [8, 9]. It is currently assumed that these disorders are associated with an inadequate response in the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal cortex system, in particular, the synthesis of cortisol and norepinephrine, which have an anti-inflammatory effect.

Depressive disorders in patients with organic voice disorders (papillomatosis, granuloma, paresis and paralysis of the larynx) are detected quite often - from 35 to 85.9% [10, 11]. According to the results of some studies [12], in these cases they occur even more often than in functional disorders (functional aphonia/dysphonia, spastic dysphonia). At the same time, the average duration of mental disorders is approximately 3 times longer than the duration of the main organic voice disorder. These data explain the frequency of development of voice pathology against the background of disorders of the anxiety-depressive spectrum, which are often preceded by psycho-traumatic factors [13]. In recent years, in the literature, when considering the association of depression with inflammatory diseases, special attention is paid to their bilateral psychosomatic relationships [14]. However, despite this, many aspects of the problem of the relationship between psychopathological disorders and laryngeal granulomas remain insufficiently studied.

At the same time, the average duration of mental disorders is approximately 3 times longer than the duration of the main organic voice disorder. These data explain the frequency of development of voice pathology against the background of disorders of the anxiety-depressive spectrum, which are often preceded by psycho-traumatic factors [13]. In recent years, in the literature, when considering the association of depression with inflammatory diseases, special attention is paid to their bilateral psychosomatic relationships [14]. However, despite this, many aspects of the problem of the relationship between psychopathological disorders and laryngeal granulomas remain insufficiently studied.

There is a point of view according to which, in order to solve this problem, it is necessary to develop a diagnostic model that uses the possibilities of psychopathological and psychological diagnostics of disorders that develop under stressful situations. One of these approaches is an affective-stress model based on complex psychopathological and psychological diagnostics with the definition of anxious, melancholy or apathetic affectivity, which predisposes to the development of anxiety and depressive disorders of various structures [9, fifteen].

The purpose of this study is to determine the variants of mental disorders in patients with laryngeal granuloma based on an affective-stress model.

Material and methods

Outpatients with granuloma of the larynx were examined, who applied for help to the Moscow Scientific and Practical Center of Otorhinolaryngology. L.I. Sverzhevsky.

We examined 30 patients with granuloma of the larynx, 26 men and 4 women, aged 33 to 65 years (mean - 48.04±8.36 years). The average duration of the disease was 22.8±25.43 months. Among the examined patients, there were 13 patients with recurrence of laryngeal granuloma after surgery and 17 with newly diagnosed granuloma.

Most of the patients included in the study are men, which objectively reflects a more frequent incidence among men, according to modern literature. 83.3% of patients had a higher education, 16.7% had a specialized secondary education. Most of the patients were employed in highly skilled labor, being middle managers, company managers and university professors prevailed among them. 76% of patients were married, 16% were divorced, 4% were unmarried, and 4% were widowers/widows. When assessing professional activity and activity in everyday life, 23.3% of patients had increased voice load, 26.7% had medium load, and 50.0% had low voice load. Thus, socio-demographic indicators indicate a fairly good socialization of the studied patient population.

76% of patients were married, 16% were divorced, 4% were unmarried, and 4% were widowers/widows. When assessing professional activity and activity in everyday life, 23.3% of patients had increased voice load, 26.7% had medium load, and 50.0% had low voice load. Thus, socio-demographic indicators indicate a fairly good socialization of the studied patient population.

The following methods were used in the work: 1) psychopathological using a semi-structured interview in accordance with the ICD-10 criteria to assess the structure and dynamics of mental disorders, as well as assessment cards for psychotraumatic situations and the psychopathological structure of disorders identified in patients; 2) psychometric , which included the use of the Hamilton Anxiety Scale and the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale; 3) psychological - to determine the type of affectivity, assess cognitive functions (memory, concentration, logical thinking, etc.), as well as the significance of psycho-traumatic events. In this case, the methods of "direct memorization of 10 words" were used; mediated memorization with the help of pictograms, projective technique "unfinished sentences"; drawing test Wartegg; methods "exclusion of the superfluous", "simple analogies", "complex analogies", "classification of objects"; 4) statistical - processing of results using the Statistica 6.0 program using parametric and non-parametric methods.

In this case, the methods of "direct memorization of 10 words" were used; mediated memorization with the help of pictograms, projective technique "unfinished sentences"; drawing test Wartegg; methods "exclusion of the superfluous", "simple analogies", "complex analogies", "classification of objects"; 4) statistical - processing of results using the Statistica 6.0 program using parametric and non-parametric methods.

Results and discussion

Among the most frequent complaints of patients were sore throat (36.6%), discomfort, discomfort in the throat (36.6%), hoarseness (20%), fatigue, weakness of voice (16.6%), feeling coma in the throat (13.3%). Most of the patients did not complain about poor mental health, and only with active questioning spoke about general physical stress. Anxiety or depression, ideational and somatovegetative manifestations of the anxiety syndrome, sleep disturbances, a feeling of overload with everyday problems were perceived by patients as a normal reaction to existing difficulties. Attention was drawn to the fact that most patients experienced difficulties in differentiating mental and bodily sensations.

Attention was drawn to the fact that most patients experienced difficulties in differentiating mental and bodily sensations.

All patients were diagnosed with mental disorders of the anxiety-depressive spectrum (ADDS). When analyzed according to the ICD-10 criteria, it was found that they are dominated by chronic, long-term disorders such as dysthymia, recurrent depressive and generalized anxiety disorder. Single depressive episodes of mild and moderate severity were also characterized by an average duration of more than 1 year (see table).

Distribution of patients with RTDS by diagnosis and duration of illness

In the vast majority of cases — 26 (86%), laryngeal granuloma developed against a background of severe mental disorder.

The following types of leading affect determined the syndromic assessment of RTDS: anxiety, melancholy, or apathy [16]. The affect of anxiety prevailed in 67% of cases, the affect of melancholy was detected in 24%, apathy - in 9%. Anxiety as the leading affect was determined in all cases of generalized anxiety disorder. Its high proportion was also noted in other RTDS - with a depressive episode (68.8%) and dysthymia (56.2%). The leading melancholy affect was more often determined in recurrent depressive disorder, apathetic — in dysthymia.

Anxiety as the leading affect was determined in all cases of generalized anxiety disorder. Its high proportion was also noted in other RTDS - with a depressive episode (68.8%) and dysthymia (56.2%). The leading melancholy affect was more often determined in recurrent depressive disorder, apathetic — in dysthymia.

In 7 (23.3%) out of 30 patients, different variants of mild cognitive impairment were identified, among which mental disorders dominated (85.7%) in the form of distortion of generalization processes, inconsistency of judgments, attention disorders were less pronounced (57.1 %), associative (28.5%) and mechanical (14.2%) memory.

The average age of the group of patients with mild cognitive impairment was 58.2±11.2 years, which is 10 years more than the average age of patients without such disorders. It could also be noted that in the group of patients with cognitive disorders, patients with higher education (71.4%) and those who continued to work (57.1%) predominated. The duration of mental disorders in the group with mild cognitive disorders was longer than in the group without them ( p <0.01), and the duration of the laryngeal granuloma did not matter.

The duration of mental disorders in the group with mild cognitive disorders was longer than in the group without them ( p <0.01), and the duration of the laryngeal granuloma did not matter.

In the psychological assessment of affectivity in patients, a uniform distribution of apathetic (36%), melancholy (32%) and anxious (32%) types was revealed, which indicates the heterogeneity of the corresponding predisposition to the development of RTDS in patients with laryngeal granuloma.

Analysis of the clinical and psychopathological structure of the syndrome and the type of affectivity made it possible to identify the following five variants of RTDS.

Anxious variant (32%) was characterized by generalized anxious mood, the severity of which depended on the influence of external traumatic factors, but at the height of anxiety, when it became diffuse, it was difficult to identify the influence of a particular psychotraumatic factor. Anxiety was not of a vital nature; no phobias or panic attacks were noted. The behavior of patients was determined by mental stress, often unconscious to the patient, unproductive fussiness and the inability to maintain attention. Such vegetative manifestations of anxiety as palpitations, sweating, instability of blood pressure were identified. There was a pronounced and stable fixation of the experiences of patients in psychotraumatic situations with the inability to cope with them. Characteristic was avoidance behavior with limited contacts, as well as postponing activities aimed at solving anxiety-producing problems.

The behavior of patients was determined by mental stress, often unconscious to the patient, unproductive fussiness and the inability to maintain attention. Such vegetative manifestations of anxiety as palpitations, sweating, instability of blood pressure were identified. There was a pronounced and stable fixation of the experiences of patients in psychotraumatic situations with the inability to cope with them. Characteristic was avoidance behavior with limited contacts, as well as postponing activities aimed at solving anxiety-producing problems.

The dreary variant (28%) was characterized by an experience of vital anguish, perceived as a painful feeling of tightness, pressure, heaviness in the chest or upper shoulder girdle. Motor and ideational retardation was noted, manifested in the slowness of speech and motor reactions. Events and habitual activities that previously aroused the patient's interest did not attract and please, as before; there was a painful sense of loss, a painful feeling of desensitization to external events, ideas of one's own guilt and low value. Sleep disorders were noted - shallow and intermittent night sleep and a decrease in appetite. Characteristic were early awakenings with a feeling of weakness and fatigue. Relief of the general condition and improvement of mood were noted in the evening hours. The dreary variant of the anxiety-depressive spectrum was characterized by stable manifestations with a tendency to form circadian dynamics.

Sleep disorders were noted - shallow and intermittent night sleep and a decrease in appetite. Characteristic were early awakenings with a feeling of weakness and fatigue. Relief of the general condition and improvement of mood were noted in the evening hours. The dreary variant of the anxiety-depressive spectrum was characterized by stable manifestations with a tendency to form circadian dynamics.

Anxious and dreary variant (12%). The melancholy syndrome in these cases was masked by severe anxiety, which made this variant similar to anxiety. However, in this variant, the pointless nature of anxiety was more often detected. The relationship between the severity of anxiety and feelings of guilt and loss was characteristic.

Anxious-apathetic variant (19%) was characterized by the presence of anxiety, which in content was associated with the circumstances of the disease. Anxiety was predominantly experienced as a feeling of inner tension, stiffness, fear for one's mental health or loss of control over it. In the anamnesis, such patients often had panic attacks or phobias, at the height of which there was a vital fear of death or loss of control over their behavior. Patients showed increased attention to their own health, aggravation of both somatic and mental pathology (formalized complaints about "depression", "anxiety", or a request for a psychiatrist's consultation). At the same time, a psychopathological examination revealed mental anesthesia (insensibility) without a hint of pain, indifference to the environment, including the means to achieve the goal. As a rule, apathy was not of a global nature and indifference was not manifested in all areas, in particular, there was no indifference to one's health.

In the anamnesis, such patients often had panic attacks or phobias, at the height of which there was a vital fear of death or loss of control over their behavior. Patients showed increased attention to their own health, aggravation of both somatic and mental pathology (formalized complaints about "depression", "anxiety", or a request for a psychiatrist's consultation). At the same time, a psychopathological examination revealed mental anesthesia (insensibility) without a hint of pain, indifference to the environment, including the means to achieve the goal. As a rule, apathy was not of a global nature and indifference was not manifested in all areas, in particular, there was no indifference to one's health.

The apathetic variant (9%) was characterized by dominance in the clinical picture of mental anesthesia, which, unlike the dreary variant, did not bear painful perception. In this regard, indifference to the environment and the limitation of the range of motivations were revealed. Patients almost did not complain about the mental state, were not interested in assessing the disorder, conducting an examination and possible treatment. In general, this variant was characterized by the stability of manifestations of apathy.

Patients almost did not complain about the mental state, were not interested in assessing the disorder, conducting an examination and possible treatment. In general, this variant was characterized by the stability of manifestations of apathy.

Anxious, dreary and apathetic variants of RTDS are the main ones.

In the analysis of psychotraumatic factors, first of all, stress factors that were in effect for 12 months before the onset of both symptoms of laryngeal granuloma and RTDS were taken into account, while the duration of events was assessed with a conditional allocation of acute and chronic factors, and the specifics of the disease were taken into account, in particular the presence of chronic stress in the form of increased voice load due to professional or other factors. The latter occurred in more than 1/3 (36.6%) of patients, although only 1/3 of them had professions related to the voice (teachers of higher and secondary educational institutions, dispatchers). Most of these patients were characterized by an incorrect use of the voice that did not correspond to their needs and abilities, which was associated with muscle tension, characteristic of psychomotor manifestations of anxiety, which dominated in most cases.

Most of these patients were characterized by an incorrect use of the voice that did not correspond to their needs and abilities, which was associated with muscle tension, characteristic of psychomotor manifestations of anxiety, which dominated in most cases.

When analyzing psychotraumatic factors, it was also revealed that the significance of the situation directly related to the diagnosis of laryngeal granuloma and the unclear prognosis of this disease turned out to be much less significant for patients than other psychotraumatic factors. It was in these cases that a mental disorder developed almost simultaneously with the appearance of the first symptoms of the disease. An analysis of the anamnestic data showed that 63.3% of patients did not associate the onset of voice disorders with a traumatic event, while 36.6% of patients found a temporal relationship between the onset of the first symptoms of laryngeal granuloma and chronic stressful events.

Among the psycho-traumatic factors preceding the development of laryngeal granuloma, long-term psycho-traumatic situations were identified in the form of social stressful situations (28. 5%) and family conflicts (20.0%). Traumatic factors associated with the course of any other somatic disease (diagnosis, unclear outcome, surgery) were observed in 19.0%.

5%) and family conflicts (20.0%). Traumatic factors associated with the course of any other somatic disease (diagnosis, unclear outcome, surgery) were observed in 19.0%.

In general, most often RTDS was preceded by family conflicts (23.8%), the loss of a loved one (19.1%) and a change in social status (19,one%).

Thus, psychotraumatic factors preceding the onset of mental disorders can be divided into acute, acute, with a subsequent transition to chronic and chronic. Chronic psycho-traumatic factors or exacerbation of the corresponding situations had the greatest significance (90.0%) for the development of RTDS. Stress factors associated with the diagnosis, including the need to exclude cancer, unclear prognosis, possible surgery, were typical for patients with newly diagnosed laryngeal granuloma. Most often, these situations served as an additional mental burden against the background of chronic trouble. For the development of mental disorders, personal conflicts, determined by the different affectivity of patients, also mattered. In this regard, the perception of psychotraumatic situations in the form of an obstacle in achieving the goal (36.6%), a violation of external regulatory frameworks (33.4%) and an ethical conflict with the significance of interpersonal relationships (30%) was significant for patients. A change in social status was more often perceived as a conflict of loss or violation of external regulatory frameworks. Family conflicts and somatic problems often hindered the achievement of the goal. Ethical conflict was predominantly associated with feelings of guilt in violation of interpersonal relationships.

In this regard, the perception of psychotraumatic situations in the form of an obstacle in achieving the goal (36.6%), a violation of external regulatory frameworks (33.4%) and an ethical conflict with the significance of interpersonal relationships (30%) was significant for patients. A change in social status was more often perceived as a conflict of loss or violation of external regulatory frameworks. Family conflicts and somatic problems often hindered the achievement of the goal. Ethical conflict was predominantly associated with feelings of guilt in violation of interpersonal relationships.

Clinical and therapeutic analysis of the results of a short course of therapy was carried out in 15 patients with RTDS with laryngeal granuloma. Antidepressants (sertraline, mianserin, amitriptyline) and neuroleptics with antidepressant action (flupentixol, sulpiride) were prescribed mainly as monotherapy in small initial daily doses. In addition, all patients underwent individual psychotherapeutic sessions based on the diagnosis of affectivity and aimed at resolving the conflict. This approach made it possible to identify vulnerable personality traits and develop a strategy for overcoming negative life situations that corresponds to this affective structure. The choice of therapeutic tactics was based on both the syndromic psychopathological diagnosis of RTDS and the determination of the type of affectivity. The study showed good results of a short course of monotherapy with antidepressants with a positive effect on both depressive and anxiety syndrome ( p <0.001). A pronounced statistically significant reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms appeared from the 2nd week of therapy ( p <0.001). A significant reduction in anxiety symptoms contributed to a decrease in muscle tension, including the muscles of the larynx, which in turn contributed to an improvement in voice function. During the treatment, there were no pronounced side and undesirable effects, as well as incompatibility with the therapy received by patients for laryngeal granuloma.

This approach made it possible to identify vulnerable personality traits and develop a strategy for overcoming negative life situations that corresponds to this affective structure. The choice of therapeutic tactics was based on both the syndromic psychopathological diagnosis of RTDS and the determination of the type of affectivity. The study showed good results of a short course of monotherapy with antidepressants with a positive effect on both depressive and anxiety syndrome ( p <0.001). A pronounced statistically significant reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms appeared from the 2nd week of therapy ( p <0.001). A significant reduction in anxiety symptoms contributed to a decrease in muscle tension, including the muscles of the larynx, which in turn contributed to an improvement in voice function. During the treatment, there were no pronounced side and undesirable effects, as well as incompatibility with the therapy received by patients for laryngeal granuloma.

It should be noted that in 10 (67%) of 15 patients after the end of the course of treatment, there was a decrease in the intensity of perifocal inflammation, as well as a tendency to stop the growth of the granuloma. In addition, 6 months after psychopharmacotherapy, most patients experienced stable remission.

Thus, the results of the study showed a close relationship between laryngeal granuloma and mental disorders of the anxiety-depressive spectrum, identified in all examined patients. At the same time, the development of inflammatory phoniatric disease in most patients occurred against the background of a mental disorder. The psychopathological structure of RTDS was characterized by a high frequency and severity of anxiety syndrome with psychomotor disorders affecting the voice function. In addition, mental disorders were characterized by a long, often chronic course, significantly complicating everyday adaptation. These observations confirm current concepts of a two-way relationship between anxiety and depressive disorders and some chronic inflammatory diseases, possibly due to the influence of chronic stress factors. Psychotraumatic factors preceding a mental disorder were distinguished by a long-term effect, mainly in the form of social and family problems. The fact of diagnosing laryngeal granuloma and the fears caused by this, as a rule, were not the primary stress factor provoking RTDS.

Psychotraumatic factors preceding a mental disorder were distinguished by a long-term effect, mainly in the form of social and family problems. The fact of diagnosing laryngeal granuloma and the fears caused by this, as a rule, were not the primary stress factor provoking RTDS.

Analysis of the data obtained confirmed that the affectivity of patients determined the selectivity of perception and response to psycho-traumatic factors. The results of the study showed a uniform distribution of the three types of affectivity in the sample of examined patients. The presence of anxious, melancholy or apathetic affectivity in patients suggested the absence of a unified therapeutic approach for the treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders in patients with laryngeal granuloma.

High sensitivity of patients to pharmacotherapy of depression in terms of reduction of psychopathological symptoms and granuloma dynamics was revealed. The most significant result is the improvement in the prognosis of laryngeal granuloma with successful treatment of RTDS, which was observed in almost ½ of patients who underwent a course of psychopharmacotherapy.

The results generally confirm the effectiveness of an interdisciplinary approach based on an affective-stress model in the diagnosis and treatment of patients suffering from laryngeal granuloma and anxiety-depressive spectrum disorders.

adverse effects, as well as incompatibility with the therapy received by patients for laryngeal granuloma.

It should be noted that in 10 (67%) of 15 patients after the end of the course of treatment, there was a decrease in the intensity of perifocal inflammation, as well as a tendency to stop the growth of the granuloma. In addition, 6 months after psychopharmacotherapy, most patients experienced stable remission.

Thus, the results of the study showed a close relationship between laryngeal granuloma and mental disorders of the anxiety-depressive spectrum, identified in all examined patients. At the same time, the development of inflammatory phoniatric disease in most patients occurred against the background of a mental disorder. The psychopathological structure of RTDS was characterized by a high frequency and severity of anxiety syndrome with psychomotor disorders affecting the voice function. In addition, mental disorders were characterized by a long, often chronic course, significantly complicating everyday adaptation. These observations confirm current concepts of a two-way relationship between anxiety and depressive disorders and some chronic inflammatory diseases, possibly due to the influence of chronic stress factors. Psychotraumatic factors preceding a mental disorder were distinguished by a long-term effect, mainly in the form of social and family problems. The fact of diagnosing laryngeal granuloma and the fears caused by this, as a rule, were not the primary stress factor provoking RTDS.

The psychopathological structure of RTDS was characterized by a high frequency and severity of anxiety syndrome with psychomotor disorders affecting the voice function. In addition, mental disorders were characterized by a long, often chronic course, significantly complicating everyday adaptation. These observations confirm current concepts of a two-way relationship between anxiety and depressive disorders and some chronic inflammatory diseases, possibly due to the influence of chronic stress factors. Psychotraumatic factors preceding a mental disorder were distinguished by a long-term effect, mainly in the form of social and family problems. The fact of diagnosing laryngeal granuloma and the fears caused by this, as a rule, were not the primary stress factor provoking RTDS.

Analysis of the data obtained confirmed that the affectivity of patients determined the selectivity of perception and response to psychotraumatic factors. The results of the study showed a uniform distribution of the three types of affectivity in the sample of examined patients.