Fazes of death

Faces of Death (1978) - IMDb

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

- Trivia

IMDbPro

- 19781978

- Not RatedNot Rated

- 1h 45m

IMDb RATING

4.2/10

7.3K

YOUR RATING

DocumentaryHorror

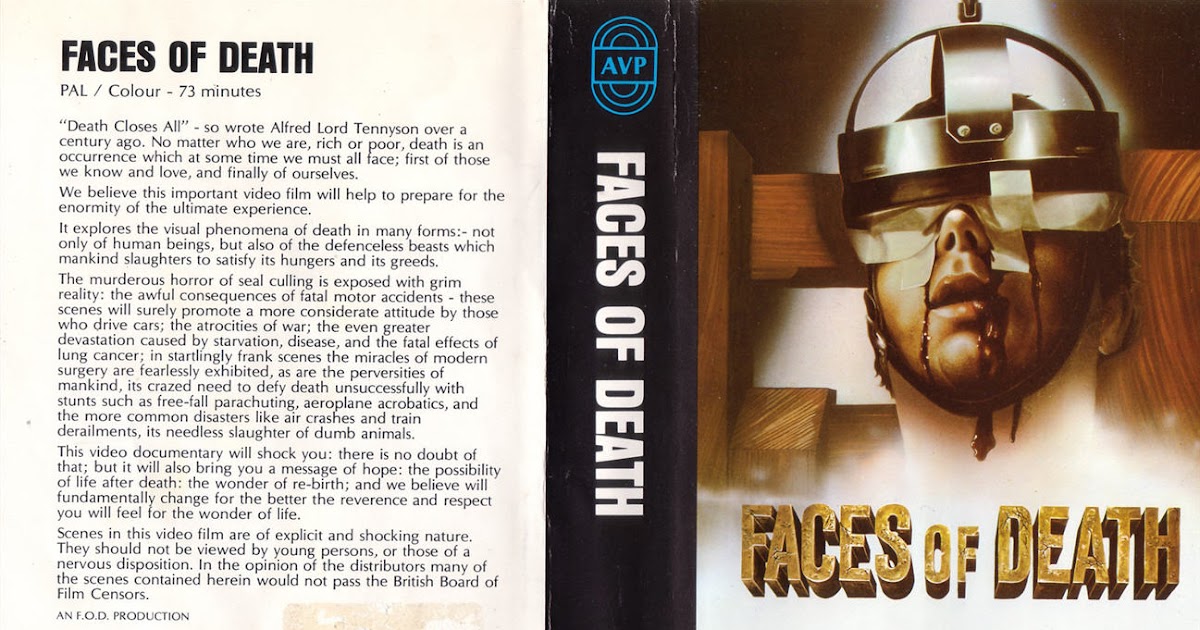

A collection of death scenes, ranging from TV material to homemade super 8 movies.A collection of death scenes, ranging from TV material to homemade super 8 movies.A collection of death scenes, ranging from TV material to homemade super 8 movies.

IMDb RATING

4.2/10

7.3K

YOUR RATING

- Director

- John Alan Schwartz

- Writer

- John Alan Schwartz

- Stars

- Michael Carr

- Samuel Berkowitz

- Mary Ellen Brighton

- Director

- John Alan Schwartz

- Writer

- John Alan Schwartz

- Stars

- Michael Carr

- Samuel Berkowitz

- Mary Ellen Brighton

Videos1

Trailer 2:17

Watch Trailer [EN]

Photos32

Top cast

Michael Carr

- Dr.

Francis B. Gröss

Samuel Berkowitz

Mary Ellen Brighton

- Self - Suicide Victim

Thomas Noguchi

- Self - Chief Medical Examiner Coroner

Adolf Hitler

- Self

- (archive footage)

- (uncredited)

Benito Mussolini

- Self

- (archive footage)

- (uncredited)

John Alan Schwartz

- Leader of Flesh Eating Cult

- (uncredited)

- Director

- John Alan Schwartz

- Writer

- John Alan Schwartz

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

More like this

Faces of Death II

Faces of Death IV

Faces of Death III

Traces of Death

Guinea Pig 2: Flower of Flesh and Blood

Cannibal Holocaust

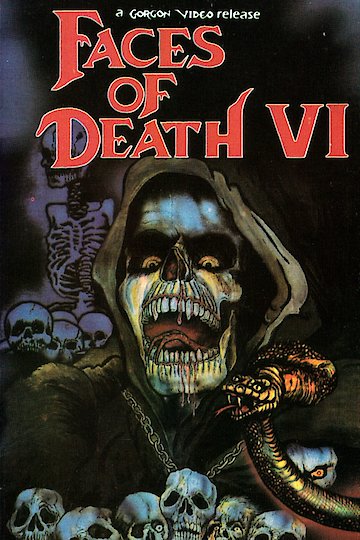

Faces of Death VI

A Dog's Life

Guinea Pig: Devil's Experiment

Faces of Death V

Facez of Death 2000

Snuff 102

Storyline

Did you know

- Trivia

In a February 2012 interview with the National Public Radio program "On the Media," the movie's creator, John Alan Schwartz, said that the scene that purports to show real tourists in Egypt killing a monkey and eating its brains was really filmed in a Moroccan restaurant in the US using Schwartz's friends as actors, foam mallets, a model monkey with a prosthetic breakaway head, a trick table, and cauliflower covered in theater blood for the brains.

- Connections

Edited into Nudo e crudele (1984)

User reviews107

Review

Featured review

WARNING!

I love gore. I am for anti-censorship. But FOR GOD'S SAKE SOMETHINGS ARE TOO MUCH. The first movie was interesting once... ONCE. The others may be first rate entertainment for Redneak teens and sick demented freaks, but for people who have socially redeeming values in they're lives should steer clear. It's cheap, and it's sick. To watch 90 (Gorgon videos lie about the run time as well) minutes of people squashing monkeys and eating them, along with slaughter house footage, mixed with executions, the torchuring and killing of animals, reinactments of murders (poorly done), and finally tossed in with a sex change operation seems sad, and very disturbing. To think people buy these videos, and watch them over again is enough to make your head spin. The implications of these movies are sevear. Not only has it spun whole cults of macabre and extreme violence, but has actually lead to murder. In New England, some years back, a troubled teen bought and watched these tapes over and over. He suffered nothing more then mild depression due to a divorce and a probably anti-social life. In the end, he shot, and gutted his best friend in his back yard in a Faces of Death fashion. Law enforcement officials and Phycologists alike link the murder to the videos. AVOID AT ALL COASTS! You will sleep easier if you never subject yourself to them.

In New England, some years back, a troubled teen bought and watched these tapes over and over. He suffered nothing more then mild depression due to a divorce and a probably anti-social life. In the end, he shot, and gutted his best friend in his back yard in a Faces of Death fashion. Law enforcement officials and Phycologists alike link the murder to the videos. AVOID AT ALL COASTS! You will sleep easier if you never subject yourself to them.

helpful•14

12

- flamingfingers87

- Aug 8, 2002

What are the differences between the British BBFC-18 DVD version and the uncut version?

Details

- Release date

- November 10, 1978 (United States)

- Country of origin

- United States

- Languages

- English

- German

- Also known as

- The Original Faces of Death

- Filming locations

- 6404 Wilshire Blvd, Los Angeles, California, USA

- Production company

- F.

O.D. Productions

O.D. Productions

- F.

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

Technical specs

- Runtime

1 hour 45 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

Related news

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content

Top Gap

By what name was Faces of Death (1978) officially released in India in English?

Answer

More to explore

Recently viewed

You have no recently viewed pages

Kubler-Ross Stages of Dying and Subsequent Models of Grief - StatPearls

Continuing Education Activity

Medical professionals will work with dying patients in all disciplines, and the process is difficult as care shifts from eliminating or mitigating illness to preparing for death. This is a difficult transition for patients, their loved ones, and healthcare providers to undergo. This activity provides paradigms for the process of moving toward death as well as a discussion of how they should and should not be applied, supporting the interprofessional team to address the unique needs of their patients and guide them and their loved ones through the process.

This is a difficult transition for patients, their loved ones, and healthcare providers to undergo. This activity provides paradigms for the process of moving toward death as well as a discussion of how they should and should not be applied, supporting the interprofessional team to address the unique needs of their patients and guide them and their loved ones through the process.

Objectives:

Describe the five stages of death, as outlined by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross.

Describe alternative paradigms for experiencing death and grief, in addition to those introduced by Kubler-Ross.

Explain the potential underlying process generating these outwardly demonstrated stages to provide a context for supporting patients, families, caregivers, and healthcare providers experiencing death.

Outline interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication in a dying patient.

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Introduction

Medical professionals in all disciplines work with dying patients, and doing so effectively can be difficult. In the context of death and dying, patients, their loved ones, and the health care team must shift their goals. Where treating acute and chronic illness usually involves finding a tolerable path to eliminating or preventing the progression of a condition, treating terminal illness must involve preparing for death as well as efforts to mitigate symptoms.[1] Understanding the experience of dying and grief allows providers to support the unique needs of patients, their loved ones, and other healthcare team members.[2][3][4]

Function

Dr. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross introduced the most commonly taught model for understanding the psychological reaction to imminent death in her 1969 book, On Death and Dying. The book explored the experience of dying through interviews with terminally ill patients and outlined the five stages of dying: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance (DABDA). This work is historically significant as it marked a cultural shift in the approach to conversations regarding death and dying. Prior to her work, the subject of death was somewhat taboo, often talked around or avoided altogether. Dying patients were not always given a voice or choices in their care plan. Some were not even explicitly told about their terminal diagnosis. Her work was popular in both the medical and lay cultures and shifted the nature of conversations around death and dying by emphasizing the experience of the dying patient.[4][5] This led to new approaches to working with patients through the final phase of life. She highlighted the importance of listening to and supporting their unique experiences and needs and spurred new perspectives on ways practitioners can support terminally ill patients and their family members in adjusting to the reality of impending death.[6]

This work is historically significant as it marked a cultural shift in the approach to conversations regarding death and dying. Prior to her work, the subject of death was somewhat taboo, often talked around or avoided altogether. Dying patients were not always given a voice or choices in their care plan. Some were not even explicitly told about their terminal diagnosis. Her work was popular in both the medical and lay cultures and shifted the nature of conversations around death and dying by emphasizing the experience of the dying patient.[4][5] This led to new approaches to working with patients through the final phase of life. She highlighted the importance of listening to and supporting their unique experiences and needs and spurred new perspectives on ways practitioners can support terminally ill patients and their family members in adjusting to the reality of impending death.[6]

Kubler-Ross and others subsequently applied her model to the experience of loss in many contexts, including grief and other significant life changes. Though the stages are frequently interpreted strictly, with an expectation that patients pass through each in sequence, Kubler-Ross noted that this was not her contention and that individual patients could manifest each stage differently, if at all. The model, which resulted from a qualitative and experiential study, was purposely personal and subjective and should not be interpreted as natural law. Rather, the stages provide a heuristic for patterns of thought, emotions, and behavior, common in the setting of terminal illness, which may otherwise seem atypical.[7] Facility with these patterns can help health care providers provide empathy and understanding to patients, families, and team members for whom these patterns may cause confusion and frustration.[6]

Though the stages are frequently interpreted strictly, with an expectation that patients pass through each in sequence, Kubler-Ross noted that this was not her contention and that individual patients could manifest each stage differently, if at all. The model, which resulted from a qualitative and experiential study, was purposely personal and subjective and should not be interpreted as natural law. Rather, the stages provide a heuristic for patterns of thought, emotions, and behavior, common in the setting of terminal illness, which may otherwise seem atypical.[7] Facility with these patterns can help health care providers provide empathy and understanding to patients, families, and team members for whom these patterns may cause confusion and frustration.[6]

Kubler-Ross's Five Stages of Dying

Denial is a common defense mechanism used to protect oneself from the hardship of considering an upsetting reality. Kubler-Ross noted that patients would often reject the reality of the new information after the initial shock of receiving a terminal diagnosis. Patients may directly deny the diagnosis, attribute it to faulty tests or an unqualified physician, or simply avoid the topic in conversation. While persistent denial may be deleterious, a period of denial is quite normal in the context of terminal illness and could be important for processing difficult information. In some contexts, it can be challenging to distinguish denial from a lack of understanding, and this is one of many reasons that upsetting news should always be delivered clearly and directly. However, unless there is adequate reason to believe the patient truly misunderstands, providers do not need to repeatedly reeducate patients about the truth of their diagnosis, though recognizing the potential confusion can help balance a patient's right to be informed with their freedom to reconcile that information without interference.

Patients may directly deny the diagnosis, attribute it to faulty tests or an unqualified physician, or simply avoid the topic in conversation. While persistent denial may be deleterious, a period of denial is quite normal in the context of terminal illness and could be important for processing difficult information. In some contexts, it can be challenging to distinguish denial from a lack of understanding, and this is one of many reasons that upsetting news should always be delivered clearly and directly. However, unless there is adequate reason to believe the patient truly misunderstands, providers do not need to repeatedly reeducate patients about the truth of their diagnosis, though recognizing the potential confusion can help balance a patient's right to be informed with their freedom to reconcile that information without interference.

Anger is commonly experienced and expressed by patients as they concede the reality of a terminal illness. It may be directed at blaming medical providers for inadequately preventing the illness, family members for contributing to risks or not being sufficiently supportive, or spiritual providers or higher powers for the diagnosis' injustice. The anger may also be generalized and undirected, manifesting as a shorter temper or a loss of patience. Recognizing anger as a natural response can help health care providers and loved ones tolerate what might otherwise feel like hurtful accusations. However, they must take care not to disregard criticism that may be warranted by attributing them solely to an emotional stage.[8]

The anger may also be generalized and undirected, manifesting as a shorter temper or a loss of patience. Recognizing anger as a natural response can help health care providers and loved ones tolerate what might otherwise feel like hurtful accusations. However, they must take care not to disregard criticism that may be warranted by attributing them solely to an emotional stage.[8]

Bargaining typically manifests as patients seeking some measure of control over their illness. The negotiation could be verbalized or internal and could be medical, social, or religious. The patients' proffered bargains could be rational, such as a commitment to adhere to treatment recommendations or accept help from their caregivers, or could represent more magical thinking, such as efforts to appease misattributed guilt they may feel is responsible for their diagnosis. While bargaining may mobilize more active participation from patients, health care providers and caregivers should take care not to mislead patients about their own power to fulfill the patients' negotiations. Again, caregivers and providers do not need to repeatedly correct bargaining behavior that seems irrational but should recognize that participating too heartily in a patient's bargains may distort their eventual understanding.

Again, caregivers and providers do not need to repeatedly correct bargaining behavior that seems irrational but should recognize that participating too heartily in a patient's bargains may distort their eventual understanding.

Depression is perhaps the most immediately understandable of Kubler-Ross's stages, and patients experience it with unsurprising symptoms such as sadness, fatigue, and anhedonia. Spending time in the first three stages is potentially an unconscious effort to protect oneself from this emotional pain. While the patient's actions may potentially be easier to understand, they may be more jarring in juxtaposition to behaviors arising from the first three stages. Consequently, caregivers may need to make a conscious effort to restore compassion that may have waned while caring for patients progressing through the first three stages.

Acceptance describes recognizing the reality of a difficult diagnosis while no longer protesting or struggling against it. Patients may focus on enjoying the time they have left and reflecting on their memories. They may begin to prepare for death practically by planning their funeral or helping to provide financially or emotionally for their loved ones. It is often portrayed as the last of Kubler-Ross's stages and a sort of goal of the dying or grieving process. While caregivers and providers may find this stage less emotionally taxing, it is important to remember that it is not inherently more healthy than the other stages. As with denial, anger, bargaining, and depression, understanding the stages has less to do with promoting a fixed progression and more to do with anticipating patients' experiences to allow more empathy and support for whatever they go through.[4][5][6][7]

Patients may focus on enjoying the time they have left and reflecting on their memories. They may begin to prepare for death practically by planning their funeral or helping to provide financially or emotionally for their loved ones. It is often portrayed as the last of Kubler-Ross's stages and a sort of goal of the dying or grieving process. While caregivers and providers may find this stage less emotionally taxing, it is important to remember that it is not inherently more healthy than the other stages. As with denial, anger, bargaining, and depression, understanding the stages has less to do with promoting a fixed progression and more to do with anticipating patients' experiences to allow more empathy and support for whatever they go through.[4][5][6][7]

Issues of Concern

Criticisms of the Kubler-Ross Model

The DABDA model has been increasingly criticized in recent years. The model has both historical and cultural significance as one of the most well-known models for understanding grief and loss. Many alternative models have been developed based at least in part on the original DABDA model. The principal criticisms of Kubler-Ross's stages of death and dying are that the stages were developed without sufficient evidence and are often applied too strictly. Kubler-Ross and her collaborators developed their ideas qualitatively through in-depth interviews with over two hundred terminally ill patients.[7]

Many alternative models have been developed based at least in part on the original DABDA model. The principal criticisms of Kubler-Ross's stages of death and dying are that the stages were developed without sufficient evidence and are often applied too strictly. Kubler-Ross and her collaborators developed their ideas qualitatively through in-depth interviews with over two hundred terminally ill patients.[7]

Critics have focused on the fact that her research and use of "stages" have not been empirically validated. It is also said that the concept of "stages" is applied too rigidly and linearly. Instead, she aimed to describe a set of behaviors and emotions that may be experienced by a patient facing the end of life, and by describing them, improve understanding for both the patient and caregivers. Another important criticism of the model arises when it is viewed as prescriptive rather than descriptive, indicating that a patient must move through each stage to reach the final goal of "acceptance. " This view holds many assumptions, including that progression through the stages is linear and that some stages are inherently less adaptive than others. Caregivers may view their job as helping a patient move through each stage, for example, moving through denial or anger onto more easily palatable stages such as bargaining or acceptance. Attempting to push the patient through the stages has the potential to cause harm, as they need to process their grief in their unique way. Dr. Kubler Ross and others have reminded readers that many patients will experience the stages fluidly, often exhibiting more than one at a time and moving between them in a non-linear fashion. It is also important to note that each stage can serve a protective role, and each patient will have a unique experience in their grief process.[4][6]

" This view holds many assumptions, including that progression through the stages is linear and that some stages are inherently less adaptive than others. Caregivers may view their job as helping a patient move through each stage, for example, moving through denial or anger onto more easily palatable stages such as bargaining or acceptance. Attempting to push the patient through the stages has the potential to cause harm, as they need to process their grief in their unique way. Dr. Kubler Ross and others have reminded readers that many patients will experience the stages fluidly, often exhibiting more than one at a time and moving between them in a non-linear fashion. It is also important to note that each stage can serve a protective role, and each patient will have a unique experience in their grief process.[4][6]

Other Models of Grief

Four additional models of grief will be described below.

Bowlby and Parkes' Four Phases of Grief

Bowlby and Parkes proposed a reformulated theory of grief based in the 1980s. Their work is based on Kubler-Ross's model and describes four phases of grief. It emphasizes that the grieving process is not linear.

Their work is based on Kubler-Ross's model and describes four phases of grief. It emphasizes that the grieving process is not linear.

Shock and Disbelief

The initial phase replaced the term "denial" due to negative connotations. In this phase, the reality becomes altered as the mind responds to a stressful situation by becoming unresponsive or numb to the new situation. Over time, the mind processes the new reality, and the patient moves to a new phase.

Searching and Yearning

This phase is closely related to the Anger and Bargaining stage of the DABDA model. The patient will attempt to undo the new reality and question the reason for it.

Disorganization and Repair

This phase closely relates to the Depression stage of the DABDA model. The patient experiences full acceptance of the new reality. They show signs of depression and apathy.

Rebuilding and Healing

In this phase, the patient experiences a "renewed sense of identity," which represents overcoming the sense of loss and beginning to feel in control of their destiny. They no longer show signs of depression.

They no longer show signs of depression.

Worden's Four Basic Tasks In Adapting To Loss

Worden's model of grief does not rely on stages but instead notes that the patient must complete four tasks to complete bereavement. These tasks do not occur in any specific order. The grieving person may work on a task intermittently until it is complete. This model applies to the grief of a survivor but may also be applied to a patient facing death.

Accepting Reality of Loss

Initially, the patient may have difficulty accepting the reality of impending death. Typically, acceptance is viewed as being ready to move forward with the process of preparing for death.

Experiencing Pain of Grief

Patients may feel sadness, anger, or confusion. They are experiencing the pain of loss. The task is completed as the patient begins to feel "normal" again.

Adjusting to Environment

An all-consuming focus on impending death will cause the patient to ignore other roles in life that are important to them. The patient will typically resume daily activities such as restarting work or hobbies or becoming engaged as a spouse or parent to complete this task.

The patient will typically resume daily activities such as restarting work or hobbies or becoming engaged as a spouse or parent to complete this task.

Redirecting Emotional Energy

This task is generally applicable to grieving survivors. Survivors redirect their emotional energy from suffering the loss of a loved one to engaging in new activities that bring pleasure and new experiences. Subsequent theories on grieving have transitioned from stages and tasks of grief to more experiential and narrative methods.

Wolfelt's Companioning Approach to Grieving

Wolfelt's companioning approach views grief as a natural extension of the ability to give and receive love. As such, grief is not something to avoid but should be fully experienced and even embraced in the path to healing. The grieving person must feel their grief and learn to incorporate it into their ongoing lives. A person supporting the bereaved serves as a witness and companion alongside the bereaved as they walk through their grief journey. Wolfelt states, "Companioning is about going to the wilderness of the soul with another human being; it is not about thinking you are responsible for finding the way out."[9][10][9]

Wolfelt states, "Companioning is about going to the wilderness of the soul with another human being; it is not about thinking you are responsible for finding the way out."[9][10][9]

There are no tasks to complete, and no focus is placed on "fixing" the grief. However, he does describe six "needs of grief" or mourning that are more experiential. He acknowledges the need for grief to be both experienced and expressed, confronting the reality of the loss in tolerable doses. The bereaved must lean into or embrace the pain of the loss while focusing on self-compassion and self-care. He includes a narrative component as the bereaved transition their relationship with the departed from one of presence to one of memory and the need to explore their new identity in living without their lost beloved. They find a sense of meaning or peace with the loss and possibly confront their spiritual beliefs and framework while doing so. They also need to explore the positive aspects of their new identity after the loss. Finally, he also stresses the need to develop a support system that will encourage the bereaved toward self-compassion as grief resurges over the coming months and years.[9]

Finally, he also stresses the need to develop a support system that will encourage the bereaved toward self-compassion as grief resurges over the coming months and years.[9]

Neimeyer's Narrative and Constructivist Model

Neimeyer views grieving as a process of meaning-making. He acknowledges that people co-construct their understanding of reality through a narrative of their own life stories, influenced by their beliefs and world views. He describes "six key realities influenced by death." In these six realities, he acknowledges that significant loss can validate or invalidate a person's framework and beliefs in life. It may require developing a new framework to heal and incorporate the loss into their worldview. Grief is simultaneously universal and unique, so the therapy for the bereaved must be tailored to each client's individual needs. The process of griefing is inherently an active rather than passive period, filled with decision-making and reconstruction both practically and existentially.

Emotions during the grieving period are useful and can serve as guides in the process of reconstructing a sense of balance and meaning in life after the disruption caused by significant loss. Reconstructing an identity after a significant loss is an inherently social process, as the new identity is in part defined in relation to their community and social norms. And finally, adapting to loss involves finding a way to incorporate the loss into a new identity and self-narrative, giving the loss a sense of meaning, and making sense of the changes. This can enable not only survival after a loss but eventual thriving.[9][11]

Therapists using the narrative and constructivist model may have patients re-tell the story of their loss with visual aids exploring the thoughts and feelings that accompany the story. They may also suggest writing a goodbye letter to the deceased or exploring their feelings through metaphors.

Clinical Significance

The transition in care, from attempting to heal the patient to caring for them near death, can be difficult for everyone involved. Healthcare providers sometimes feel as if "their job is done" as they can no longer heal the patient and "drop out" of the patient's care. This can lead patients, and their loved ones, to feel they are being abandoned as they near death. They often wish for guidance on the complex changes that the patient is going through emotionally and physically. Actions that are a normal part of the dying process, such as anger and refusing visitors, can leave loved ones confused and upset. Understanding the stages of grief allows providers to give support and guidance during the dying process. The explanations provided by medical caregivers hold particular importance for patients and family members as they seek to understand and subsequently make sense of terminal illness. These key moments of communication and connection can be pivotal in the process of making sense of and healing from significant loss.[12][13] Facility with the grieving process is also imperative for the healing and resiliency of medical caregivers as they navigate through grief alongside their patients.

Healthcare providers sometimes feel as if "their job is done" as they can no longer heal the patient and "drop out" of the patient's care. This can lead patients, and their loved ones, to feel they are being abandoned as they near death. They often wish for guidance on the complex changes that the patient is going through emotionally and physically. Actions that are a normal part of the dying process, such as anger and refusing visitors, can leave loved ones confused and upset. Understanding the stages of grief allows providers to give support and guidance during the dying process. The explanations provided by medical caregivers hold particular importance for patients and family members as they seek to understand and subsequently make sense of terminal illness. These key moments of communication and connection can be pivotal in the process of making sense of and healing from significant loss.[12][13] Facility with the grieving process is also imperative for the healing and resiliency of medical caregivers as they navigate through grief alongside their patients. [14]

[14]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

For the healthcare team, caring for patients near death can be uniquely challenging for everyone involved. Healthcare providers sometimes feel as if "their job is done" as they can no longer heal the patient and "drop out" of the patient's care. This can lead to patients and their loved ones feeling abandoned by the healthcare team as they near death.[15] They often wish for guidance emotionally and physically. This is where an end-of-life interdisciplinary team can be very helpful. Physicians can provide clarity on diagnostic and prognostic information. Pharmacists participate by dispensing appropriate comfort medication in a timely fashion by working directly with the nursing staff. Hospice care providers, including social workers and nursing staff, can provide counsel, administer comfort care, deliver emotional support, and empathize with both the patient and the family. The healthcare team should possess an understanding of the models for grief, which allows providers to give support and guidance during the dying process and provides a coordinated effort to provide the patient and family with much-needed emotional support. [Level 5]

[Level 5]

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

References

- 1.

Friedrichsdorf SJ, Bruera E. Delivering Pediatric Palliative Care: From Denial, Palliphobia, Pallilalia to Palliactive. Children (Basel). 2018 Aug 31;5(9) [PMC free article: PMC6162556] [PubMed: 30200370]

- 2.

Pravin RR, Enrica TEK, Moy TA. The Portrait of a Dying Child. Indian J Palliat Care. 2019 Jan-Mar;25(1):156-160. [PMC free article: PMC6388603] [PubMed: 30820120]

- 3.

Thurn T, Borasio GD, Chiò A, Galvin M, McDermott CJ, Mora G, Sermeus W, Winkler AS, Anneser J. Physicians' attitudes toward end-of-life decisions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2019 Feb;20(1-2):74-81. [PubMed: 30789031]

- 4.

Corr CA. Should We Incorporate the Work of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in Our Current Teaching and Practice and, If So, How? Omega (Westport).

2021 Sep;83(4):706-728. [PubMed: 31366311]

2021 Sep;83(4):706-728. [PubMed: 31366311]- 5.

Bregman L. Kübler-Ross and the Re-visioning of Death as Loss: Religious Appropriation and Responses. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2019 Mar;73(1):4-8. [PubMed: 30895849]

- 6.

Ross Rothweiler B, Ross K. Fifty Years Later: Reflections on the Work of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross M.D. Am J Bioeth. 2019 Dec;19(12):3-4. [PubMed: 31746702]

- 7.

Corr CA. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and the "Five Stages" Model in a Sampling of Recent American Textbooks. Omega (Westport). 2020 Dec;82(2):294-322. [PubMed: 30439302]

- 8.

Smaldone MC, Uzzo RG. The Kubler-Ross model, physician distress, and performance reporting. Nat Rev Urol. 2013 Jul;10(7):425-8. [PubMed: 23609853]

- 9.

Bruce CA. Helping patients, families, caregivers, and physicians, in the grieving process. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2007 Dec;107(12 Suppl 7):ES33-40. [PubMed: 18165376]

- 10.

Schuelke T, Crawford C, Kentor R, Eppelheimer H, Chipriano C, Springmeyer K, Shukraft A, Hill M.

Current Grief Support in Pediatric Palliative Care. Children (Basel). 2021 Apr 04;8(4) [PMC free article: PMC8066285] [PubMed: 33916583]

Current Grief Support in Pediatric Palliative Care. Children (Basel). 2021 Apr 04;8(4) [PMC free article: PMC8066285] [PubMed: 33916583]- 11.

Neimeyer RA, Baldwin SA, Gillies J. Continuing bonds and reconstructing meaning: mitigating complications in bereavement. Death Stud. 2006 Oct;30(8):715-38. [PubMed: 16972369]

- 12.

Meert KL, Eggly S, Kavanaugh K, Berg RA, Wessel DL, Newth CJ, Shanley TP, Harrison R, Dalton H, Dean JM, Doctor A, Jenkins T, Park CL. Meaning making during parent-physician bereavement meetings after a child's death. Health Psychol. 2015 Apr;34(4):453-61. [PMC free article: PMC4380228] [PubMed: 25822059]

- 13.

Berbís-Morelló C, Mora-López G, Berenguer-Poblet M, Raigal-Aran L, Montesó-Curto P, Ferré-Grau C. Exploring family members' experiences during a death process in the emergency department: A grounded theory study. J Clin Nurs. 2019 Aug;28(15-16):2790-2800. [PubMed: 29752844]

- 14.

Zhai Y, Du X.

Loss and grief amidst COVID-19: A path to adaptation and resilience. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Jul;87:80-81. [PMC free article: PMC7177068] [PubMed: 32335197]

Loss and grief amidst COVID-19: A path to adaptation and resilience. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Jul;87:80-81. [PMC free article: PMC7177068] [PubMed: 32335197]- 15.

Stroebe M, Schut H, Boerner K. Cautioning Health-Care Professionals. Omega (Westport). 2017 Mar;74(4):455-473. [PMC free article: PMC5375020] [PubMed: 28355991]

Fear of death: causes of thanatophobia and how to get rid of it

Thanatophobia (fear of death) is an anxiety that many people face, especially in moments like today. Existential psychologist Alena Vanchenko talks about why obsessive thoughts about death arise and how to get rid of the fear of dying - in this material

What is thanatophobia?

Thanatophobia is the fear of death, but one must separate fear, phobia and phobic disorder. Each of us has fears, and it is normal that from time to time we are afraid of something. If we listened to behavioral psychologists, they would say that the fear of death is the mother of all fears. We are not afraid of dogs, we are afraid that dogs will harm us. We are not afraid of spiders, we are afraid that they will bite us. We are not afraid of heights, but we are afraid that we will break. Behind every fear is the need to save one's own life. All living things are afraid of death. The problem arises when this fear escalates.

If we listened to behavioral psychologists, they would say that the fear of death is the mother of all fears. We are not afraid of dogs, we are afraid that dogs will harm us. We are not afraid of spiders, we are afraid that they will bite us. We are not afraid of heights, but we are afraid that we will break. Behind every fear is the need to save one's own life. All living things are afraid of death. The problem arises when this fear escalates.

Fear of death: causes

In adults, obsessive thoughts about death appear at the time of existential crises related to existential issues. Very often, such fears are exacerbated by funerals, the death of loved ones, the discovery of diseases, in principle, awareness of one's own mortality at different stages of life. They are also aggravated with phobias.

The encyclopedic definition of a phobia is an irrational fear, but death is completely logical, it will happen to us all. Although a kind of fuse turns on in our head, which suggests that death is happening, but not with us.

Although a kind of fuse turns on in our head, which suggests that death is happening, but not with us.

The fear of death is also aggravated when a person is in age crises, for example, in a midlife crisis when parents pass away. At this moment, we remember our own mortality and understand that half of our life has passed, we begin to ask questions: what good have I done in my life? And at this moment, people embark on various interesting actions - they make young lovers, look for other forms of realization, leave work, because the crisis reminds them that there is not much left to live.

It is also associated with medical operations and physiological changes, such as finding a gray hair or getting a dental implant. And thus we understand that our body is changing, even if we are not aware of such changes.

Why it is normal to be afraid of death

It is typical for any living creature to feel fear for his life, because our main task is to save ourselves. The instinct of self-preservation is triggered: it is very important for us to survive. Therefore, of course, death as the antipode of life causes panic fear.

The instinct of self-preservation is triggered: it is very important for us to survive. Therefore, of course, death as the antipode of life causes panic fear.

It must be said that man has gone far from other mammals, because they do not experience an obsessive fear of death. Man is the only being who has realized his own mortality, and this thought has to be digested somehow, no matter how hard it may be. True, there is a hypothesis that elephants also guess about their mortality, because they have the equivalent of a human funeral, they also mourn for the departed.

Phobia of death: when it is time to see a psychotherapist

Thanatophobia is seen as a constant anxiety tension from panic fear and uncertainty about what will happen after. And if it becomes pathological - all thoughts of a person are drowning in anxiety and horror from the fact that he is mortal, and thoughts about death become obsessive, obsessive - this begins to affect the quality of a person's life, manifests itself in seizures, panic attacks. If a person stops leaving the house, limits his life, then we are already talking about a phobic disorder, and this is already a psychiatric diagnosis that requires appropriate treatment.

If a person stops leaving the house, limits his life, then we are already talking about a phobic disorder, and this is already a psychiatric diagnosis that requires appropriate treatment.

If we are not talking about a phobic disorder, then a psychologist and psychotherapist can help overcome both fear and phobia, and in the case of a phobic disorder, you need to contact a psychiatrist.

Related material

How to get rid of the fear of death

When we talk about working with phobias in psychotherapy, one of the best means is the techniques of cognitive-behavioral therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, where we refocus a person’s thought, fight obsessive thoughts, learn tools how to calm yourself, cope with the psychosomatic manifestations of the phobia. We are trying to reframe experience: when we switch from what awaits us beyond death, something terrible and all-consuming, to something that is unknown, and we most likely will not care when it happens to us.

There is a humanistic approach that says that life is worth living, because after death we will not care anymore. From this point of view, the enjoyment of life is promoted, because knowing your deadline, it would be good to accumulate some amount of experience, pleasure and joy by this deadline. Every life ends the same way. But at the same time, the difference is in what it was filled with. This is a kind of refocusing of attention and a possible approach to how to overcome obsessive fear.

How different cultures view death

Different cultures view death differently. In Bali, for example, there are parades of the dead. And when a person passes away in New Orleans in the USA, it is celebrated with dances and songs. This is due to the idea that a loved one ends up in a better world after death, and therefore we need to be happy for him. Attitudes towards death depend not so much on religion as on culture. Religion sets the direction of thought, but culture supports it with rituals and practices.

Religion sets the direction of thought, but culture supports it with rituals and practices.

Related material

How we learn to fear death

Every culture maintains attitudes towards death and burial through social tools and interactions between people. We teach our children how to properly respond to death from a very young age. From the age of five, we learn about death in books and fairy tales. The child has a question: what happened next? And here parents need to very gently and carefully explain this topic to the child. Because the wrong approach in education can lead to the onset of a phobia, the child will have anxiety and obsessive thoughts. Therefore, parents should discuss the topic of death with their children if they have questions.

How the pandemic has affected the perception of death

The pandemic has changed our attitude towards death, but not in terms of the fact that it has become commonplace, because the sudden death of loved ones is never commonplace. This is an incredible loss for which the emotion of grief is reserved in the human emotional intelligence, which allows us to learn to live in a new reality.

This is an incredible loss for which the emotion of grief is reserved in the human emotional intelligence, which allows us to learn to live in a new reality.

The pandemic reminded people of mortality, and by doing so did an amazing thing: people suddenly realized that until the moment of leaving for another world came, it would be nice to live. We see activity in the labor market: people leave jobs where they feel uncomfortable because they don’t want to spend their whole lives there. Because they want to do something new, cool in their life, from which they enjoy. Therefore, in response, companies began to think about how to make the lives of employees better.

Is the fear of death dangerous?

The fear of death itself is not dangerous, it's a wonderful thing because it encourages us to avoid making risky decisions that could harm us. Thanatophobia thus contributes to our security. He also reminds us that this life would be worth living. Memento mori - remember death. This fear on the horizon of our consciousness reminds us that everything in life is finite, including ourselves.

Memento mori - remember death. This fear on the horizon of our consciousness reminds us that everything in life is finite, including ourselves.

But the absence of fear of death is incredibly dangerous. People who have this part of the brain removed, and such an operation is possible, increase the number of risks in life. A person begins to jump with a parachute, put himself in dangerous situations, feels invulnerable and therefore tests his own viability. That is why such things never end well, because the fear of death is an important thing that keeps us alive.

Related material

About the fear of death

Fear of death is typical for phobic anxiety disorder. We receive a lot of letters describing him. If you want to stop envy from pills, you will have to change your attitude towards the treatment process. You no longer even notice how you are programming yourself for the anxious expectation of an “attack” and the fear of death. You have already formed a powerful phobic installation. The attitudes that shape our words, thoughts and images are a very powerful force. They permeate our entire lives. And we are either their blind hostages, or they are our faithful helpers. Without understanding the mechanism of your harmful thoughts and harmful (as they say dysfunctional among professionals) attitude, it is impossible to get rid of your bad habit of unconscious self-intimidation. It is important to understand that panic disorder or agoraphobia, manifested by panic attacks or regular increased anxiety, is the result of a bad habit. Therefore, it is necessary to treat fear not as a disease that does not depend on you, but as a bad habit, the maintenance or overcoming of which depends on you. The same applies to treatment. It should not be approached passively by simply bringing your body to the specialist and plopping it into a chair or hospital bed. The attitude of therapy of neurosis as to the treatment of a fracture - "they put a cast and wait for it to grow together" - will not work here.

You have already formed a powerful phobic installation. The attitudes that shape our words, thoughts and images are a very powerful force. They permeate our entire lives. And we are either their blind hostages, or they are our faithful helpers. Without understanding the mechanism of your harmful thoughts and harmful (as they say dysfunctional among professionals) attitude, it is impossible to get rid of your bad habit of unconscious self-intimidation. It is important to understand that panic disorder or agoraphobia, manifested by panic attacks or regular increased anxiety, is the result of a bad habit. Therefore, it is necessary to treat fear not as a disease that does not depend on you, but as a bad habit, the maintenance or overcoming of which depends on you. The same applies to treatment. It should not be approached passively by simply bringing your body to the specialist and plopping it into a chair or hospital bed. The attitude of therapy of neurosis as to the treatment of a fracture - "they put a cast and wait for it to grow together" - will not work here. As Avicenna (Abu Ali Hussein ibn Abdallah ibn Sina) said a thousand years ago: “There are three of us, you, me and your disease. And whichever side you take, that one will win."

As Avicenna (Abu Ali Hussein ibn Abdallah ibn Sina) said a thousand years ago: “There are three of us, you, me and your disease. And whichever side you take, that one will win."

For a person who has experienced symptoms of fear and panic for many years, the need to be aware and recognize something there may seem strange. Many people think that they can immediately distinguish the symptoms of fear from a physical illness, but this is not always the case, and some still confuse one with the other. For example, a person suffering from panic attacks often believes that chest pain or shortness of breath is due to a physical illness (problems with the heart or blood vessels). And these symptoms, no matter how hard it is to believe, are caused precisely by fear. In addition, the symptoms of fear can appear seemingly "out of nothing", but in fact due to stresses that we are not aware of. Since the cardiovascular system is primarily involved in the body's response to stress and it works in an enhanced, but healthy (!) version of functioning, therefore “attacks” can seem like signs of a physical illness. Despite a conscious understanding of the groundlessness of one's own doubts, negative thoughts that sharply exaggerate the degree of danger can still obsessively crawl into one's head. However, nothing at all would ever be attempted if it were required to refute all possible objections. Therefore, it is important to refute your erroneous judgments, justify the safety of your choice and act despite residual anxiety (go outside, enter the elevator or subway). It cannot be said that there are no dangers around us. Anyone who claims this is at least disingenuous or seriously unhealthy. You should not change the black glasses of paranoia for rose-colored glasses of complacency. In both cases, we are in for trouble. Of course, there are dangers and there are many of them, but their probability differs significantly in different situations. And most importantly, learn to accurately and adequately assess these probabilities and risks. The guarantee that nothing can happen to a person is given only by death.

Despite a conscious understanding of the groundlessness of one's own doubts, negative thoughts that sharply exaggerate the degree of danger can still obsessively crawl into one's head. However, nothing at all would ever be attempted if it were required to refute all possible objections. Therefore, it is important to refute your erroneous judgments, justify the safety of your choice and act despite residual anxiety (go outside, enter the elevator or subway). It cannot be said that there are no dangers around us. Anyone who claims this is at least disingenuous or seriously unhealthy. You should not change the black glasses of paranoia for rose-colored glasses of complacency. In both cases, we are in for trouble. Of course, there are dangers and there are many of them, but their probability differs significantly in different situations. And most importantly, learn to accurately and adequately assess these probabilities and risks. The guarantee that nothing can happen to a person is given only by death. Then nothing can happen, only then it is absolutely safe. Therefore, it is important to accept the conditions of real life, where everything is possible. But everything has a different probability. Having accepted the risk of real life, you can, however, not lose your calmness and presence of mind due to accurate and adequate understanding. The main principle in challenging harmful thoughts is a specific and meaningful answer, confirmed by facts and arguments that convince you. Since the harmful thoughts themselves, although they contain errors, are very specific, meaningful and plausible. They cannot be defeated with captive phrases “everything is fine” or “we will break through”. They require hard work, regular and consistent confrontation.

Then nothing can happen, only then it is absolutely safe. Therefore, it is important to accept the conditions of real life, where everything is possible. But everything has a different probability. Having accepted the risk of real life, you can, however, not lose your calmness and presence of mind due to accurate and adequate understanding. The main principle in challenging harmful thoughts is a specific and meaningful answer, confirmed by facts and arguments that convince you. Since the harmful thoughts themselves, although they contain errors, are very specific, meaningful and plausible. They cannot be defeated with captive phrases “everything is fine” or “we will break through”. They require hard work, regular and consistent confrontation.

If something is wrong with you and your life, the first thing to do is admit it. One of the most unfortunate ways to deal with things that get in the way of your life is to ignore your inner problems. The second step is to recognize that something needs to be done about these problems, and not sometime, but right now. The third step is a plan of action, which includes the stage of collecting information, the stage of action, consolidating the action with regular training and feedback.

The third step is a plan of action, which includes the stage of collecting information, the stage of action, consolidating the action with regular training and feedback.

You need to make a list of all your typical harmful thoughts that provoke and increase fear. You will be able to notice and uncover these thoughts if you regularly use the structured self-observation diary described in cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy and train yourself to new thoughts and a new position, which in the future will become as automatic as the harmful habit program worked before.

At the moment of a panic attack, try to remind yourself that "attacks", or rather, states of anxiety and fear, are already familiar to you and have been safely experienced before. The present state is not unique (just as the inner diversionary voice of your irrational position does not want to deceive you) and therefore, like the past ones, it will soon pass. This usually takes five to ten minutes.

It is better to abandon the strategy of getting rid of fear as soon as possible. This only reinforces your state of emotional and physical tension. First of all, pinpoint the object of your fear and try to explain to yourself how unreasonable and even ridiculous it is.

This only reinforces your state of emotional and physical tension. First of all, pinpoint the object of your fear and try to explain to yourself how unreasonable and even ridiculous it is.

Repeat to yourself that, despite your terrible fear, no one has yet died or gone crazy from these attacks. Say to yourself, "This will definitely pass."

Try to identify your current body sensations and emotional state. Explaining to himself: "These are just strong emotions and natural bodily reactions to them, which is safe and harmless for my healthy body."

Give yourself the opportunity to feel uneasy about breathing difficulties and immediately start breathing slowly and rhythmically. You make sure you get enough oxygen.

Every one to two minutes, measure your level of anxiety using a 10-point scale. You will see that despite fluctuations in the level of anxiety, it gradually subsides. Explain to yourself that you are in control and know how to help yourself.

Take 10 slow, deep breaths using the diaphragm.