Mental asylums in america

History of Psychiatric Hospitals • Nursing, History, and Health Care • Penn Nursing

Philadelphia Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, PA c. 1900The history of psychiatric hospitals was once tied tightly to that of all American hospitals. Those who supported the creation of the first early-eighteenth-century public and private hospitals recognized that one important mission would be the care and treatment of those with severe symptoms of mental illnesses. Like most physically sick men and women, such individuals remained with their families and received treatment in their homes. Their communities showed significant tolerance for what they saw as strange thoughts and behaviors. But some such individuals seemed too violent or disruptive to remain at home or in their communities. In East Coast cities, both public almshouses and private hospitals set aside separate wards for the mentally ill. Private hospitals, in fact, depended on the money paid by wealthier families to care for their mentally ill husbands, wives, sons, and daughters to support their main charitable mission of caring for the physically sick poor.

But the opening decades of the nineteenth-century brought to the United States new European ideas about the care and treatment of the mentally ill. These ideas, soon to be called “moral treatment,” promised a cure for mental illnesses to those who sought treatment in a very new kind of institution—an “asylum.” The moral treatment of the insane was built on the assumption that those suffering from mental illness could find their way to recovery and an eventual cure if treated kindly and in ways that appealed to the parts of their minds that remained rational. It repudiated the use of harsh restraints and long periods of isolation that had been used to manage the most destructive behaviors of mentally ill individuals. It depended instead on specially constructed hospitals that provided quiet, secluded, and peaceful country settings; opportunities for meaningful work and recreation; a system of privileges and rewards for rational behaviors; and gentler kinds of restraints used for shorter periods.

Many of the more prestigious private hospitals tried to implement some parts of moral treatment on the wards that held mentally ill patients. But the Friends Asylum, established by Philadelphia’s Quaker community in 1814, was the first institution specially built to implement the full program of moral treatment. The Friends Asylum remained unique in that it was run by a lay staff rather than by medical men and women. The private institutions that quickly followed, by contrast, chose physicians as administrators. But they all chose quiet and secluded sites for these new hospitals to which they would transfer their insane patients. Massachusetts General Hospital built the McLean Hospital outside of Boston in 1811; the New York Hospital built the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum in Morningside Heights in upper Manhattan in 1816; and the Pennsylvania Hospital established the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital across the river from the city in 1841. Thomas Kirkbride, the influential medical superintendent of the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, developed what quickly became known as the “Kirkbride Plan” for how hospitals devoted to moral treatment should be built and organized. This plan, the prototype for many future private and public insane asylums, called for no more than 250 patients living in a building with a central core and long, rambling wings arranged to provide sunshine and fresh air as well as privacy and comfort.

This plan, the prototype for many future private and public insane asylums, called for no more than 250 patients living in a building with a central core and long, rambling wings arranged to provide sunshine and fresh air as well as privacy and comfort.

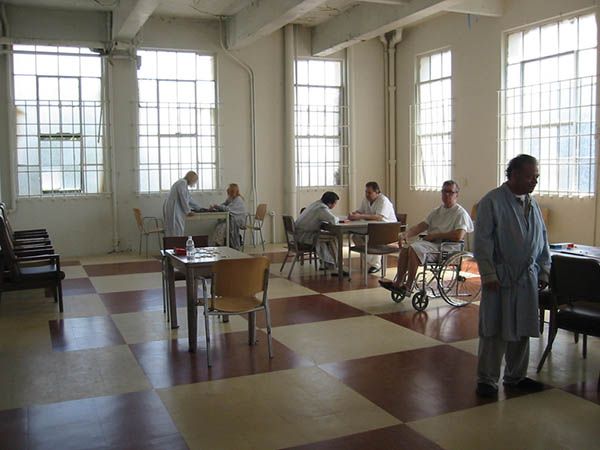

Occupational Therapy Group, Philadelphia Hospital for Mental Diseases, Thirty-fourth and Pine StreetsWith both the ideas and the structures established, reformers throughout the United States urged that the treatment available to those who could afford private care now be provided to poorer insane men and women. Dorothea Dix, a New England school teacher, became the most prominent voice and the most visible presence in this campaign. Dix travelled throughout the country in the 1850s and 1860s testifying in state after state about the plight of their mentally ill citizens and the cures that a newly created state asylum, built along the Kirkbride plan and practicing moral treatment, promised. By the 1870s virtually all states had one or more such asylums funded by state tax dollars.

By the 1890s, however, these institutions were all under siege. Economic considerations played a substantial role in this assault. Local governments could avoid the costs of caring for the elderly residents in almshouses or public hospitals by redefining what was then termed “senility” as a psychiatric problem and sending these men and women to state-supported asylums. Not surprisingly, the numbers of patients in the asylums grew exponentially, well beyond both available capacity and the willingness of states to provide the financial resources necessary to provide acceptable care. But therapeutic considerations also played a role. The promise of moral treatment confronted the reality that many patients, particularly if they experienced some form of dementia, either could not or did not respond when placed in an asylum environment.

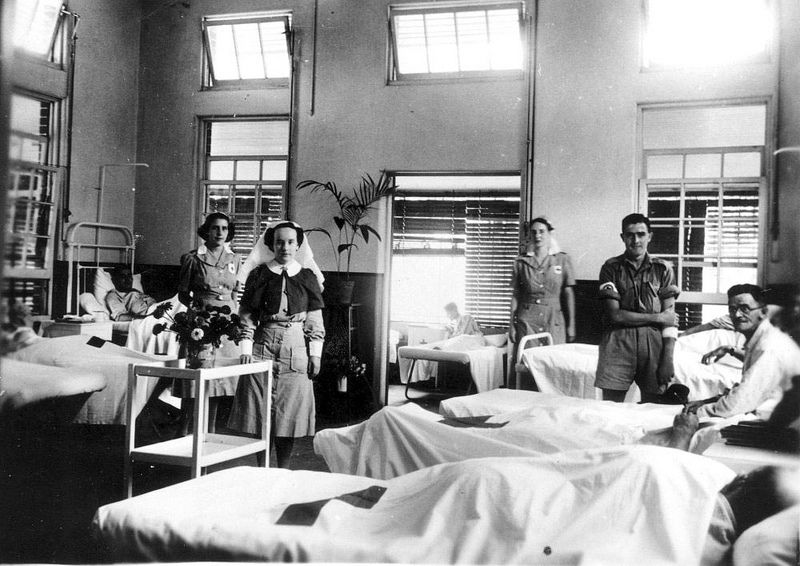

Philadelphia Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, PA c. 1900The medical superintendents of asylums took such critiques seriously. Their most significant effort to improve the quality of the care of their patients was the establishment of nurses’ training schools within their institutions. Nurses’ training schools, first established in American general hospitals in the 1860s and 1870s, had already proved critical to the success of these particular hospitals, and asylum superintendents hoped they would do the same for their institutions. These administrators took an unusual step. Rather than following an accepted European model in which those who trained as nurses in psychiatric institutions sat for a separate credentialing exam and carried a different title, they insisted that all nurses who trained in their psychiatric institutions sit for the same exam as those who trained in general hospitals and carry the same title of “registered nurse.” Leaders of the nascent American Nurses Association fought hard to prevent this, arguing that those who trained in asylums lacked the necessary medical, surgical, and obstetric experiences common to general-hospital-trained nurses.

Their most significant effort to improve the quality of the care of their patients was the establishment of nurses’ training schools within their institutions. Nurses’ training schools, first established in American general hospitals in the 1860s and 1870s, had already proved critical to the success of these particular hospitals, and asylum superintendents hoped they would do the same for their institutions. These administrators took an unusual step. Rather than following an accepted European model in which those who trained as nurses in psychiatric institutions sat for a separate credentialing exam and carried a different title, they insisted that all nurses who trained in their psychiatric institutions sit for the same exam as those who trained in general hospitals and carry the same title of “registered nurse.” Leaders of the nascent American Nurses Association fought hard to prevent this, arguing that those who trained in asylums lacked the necessary medical, surgical, and obstetric experiences common to general-hospital-trained nurses. But they could not prevail politically. It would be decades before American nursing leaders had the necessary social and political weight to ensure that all training school graduates—irrespective of the site of their training—had comparable clinical and classroom experiences.

But they could not prevail politically. It would be decades before American nursing leaders had the necessary social and political weight to ensure that all training school graduates—irrespective of the site of their training—had comparable clinical and classroom experiences.

Byberry State Hospital, Philadelphia, PA c. 1920It is, at present, hard to assess the impact of nurses’ training schools on the actual care of patients in psychiatric institutions. In some larger public institutions, the students worked only on particular wards. It does seem that they had a more substantive impact on the care of patients in much smaller and private psychiatric hospitals where they had more contact with more patients. Still, it may be that their most enduring contribution was opening the practice of professional nursing to men. Training schools in asylums, unlike those in general hospitals, actively welcomed men. Male students found places either in schools that also accepted women or in separate schools formed just for them.

Training schools for nurses, however, could not stop the assault on psychiatric asylums. The economic crisis of the 1930s drastically cut state appropriations, and World War II created acute shortages of personnel. Psychiatrists, themselves, began looking for other practice opportunities by more closely identifying with general, more reductionistic, medicine. Some established separate programs—often called “psychopathic hospitals”—within general hospitals to treat patients suffering from acute mental illnesses. Others turned to the early-twentieth-century’s new Mental Hygiene Movement and created outpatient clinics and new forms of private practice focused on actively preventing the disorders that might result in a psychiatric hospitalization. And still others experimented with new forms of therapies that posited brain pathology as a cause of mental illness in the same way that medical doctors posited pathology in other body organs as the cause of physical symptoms: they tried insulin and electric shock therapies, psychosurgery, and different kinds of medications.

By the 1950s, the death knell for psychiatric asylums had sounded. A new system of nursing homes would meet the needs of vulnerable elders. A new medication, chlorpromazine, offered hopes of curing the most persistent and severe psychiatric symptoms. And a new system of mental health care, the community mental health system, would return those suffering from mental illnesses to their families and their communities.

Today, only a small number of the historic public and private psychiatric hospitals exist. Psychiatric care and treatment are now delivered through a web of services including crisis services, short-term and general-hospital-based acute psychiatric care units, and outpatient services ranging from twenty-four-hour assisted living environments to clinics and clinicians’ offices offering a range of psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments. The quality and availability of these outpatient services vary widely, leading some historians and policy experts to wonder if “asylums,” in the true sense of the word, might be still needed for the most vulnerable individuals who need supportive living environments.

Patricia D’Antonio is Carol E. Ware Professor in Mental Health Nursing, Chair, Department of Family and Community Health, Director, Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing, and Senior Fellow, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics.

The American Mental Asylum: A Remnant of History

Growing up as a boy in northern New Jersey, my first encounter with psychiatry was driving with my grandparents past a large, imposing hospital complex in Essex County called Overbrook. Built in a cottage style, the hospital center was comprised of various buildings spread out over the beautiful rolling hills of Cedar Grove, New Jersey.

Overbrook was just one of several asylums in northern and central New Jersey that were still in operation when I was a boy, including Greystone Park in Morris Plains and Marlboro State Hospital in Monmouth County. Like most American asylums, all three closed permanently in the late 1990s and 2000s.

Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital, closed in 2008 and demolished in 2015.

Source: Public domain

The mass closure of state mental hospitals in the United States coincided with the advent and popularity of neuroleptic medications, the patient rights movement, and the well-intentioned, but poorly delivered, national transition towards community-based mental health care (see my article with Allen Frances, M.D., in Psychiatric Times on this subject here).

At one point in the 1950s, more than half a million Americans were confined to state psychiatric institutions, many of them for life. Today, the total number of state psychiatric beds in the U.S. sits around 37,000, with most beds on short-term, acute inpatient units in general medical hospitals.

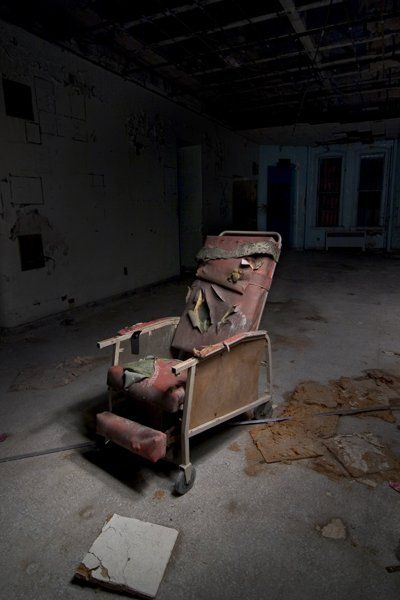

The state mental hospital occupies a position of great importance in the history of American psychiatry. Their grand architecture and historical value reflect a special era of psychiatry, even with its shortcomings. These magnificent buildings, and the psychiatric beds once contained within them, are dwindling as the years pass. Their history must be preserved.

These magnificent buildings, and the psychiatric beds once contained within them, are dwindling as the years pass. Their history must be preserved.

Best known as a tireless advocate for psychiatric care for the poor and disenfranchised, Dorothea Dix is chiefly responsible for the mass construction of state mental hospitals in the U.S. in the 1800s. Waves of immigration from Ireland, Germany, and Italy led to rapid population growth, prompting a greater need for appropriate medical and psychiatric treatment. Dix, a hero in the field of social work, cited the mental health of the citizenry to be of vital importance to the state. The American mental asylum was born.

A second influential figure in the history of the American psychiatric hospital is Thomas Story Kirkbride. A Pennsylvania psychiatrist, Kirkbride founded the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane, a group that later became the American Psychiatric Association. He is best known as the originator of the Kirkbride Plan for the construction of state mental hospitals. Kirkbride hospitals represent the most classic and numerous of the asylums constructed in the 19th century.

Kirkbride hospitals represent the most classic and numerous of the asylums constructed in the 19th century.

The structural features of Kirkbride hospitals reflected Dr. Kirkbride's approach to treating mental illness, which emphasized exposure to natural light and proper air circulation. Built with characteristically long, rambling wings arranged en echelon, Kirkbride hospitals maximized sunlight and fresh air and were intended to provide the utmost privacy and comfort for patients. The hospital building itself was meant to have a curative effect, "a special apparatus for the care of lunacy, [whose grounds should be] highly improved and tastefully ornamented" (Kirkbride, 1854). Thus, the idea of institutionalization was central to Kirkbride's plan for effectively treating persons with mental illness.

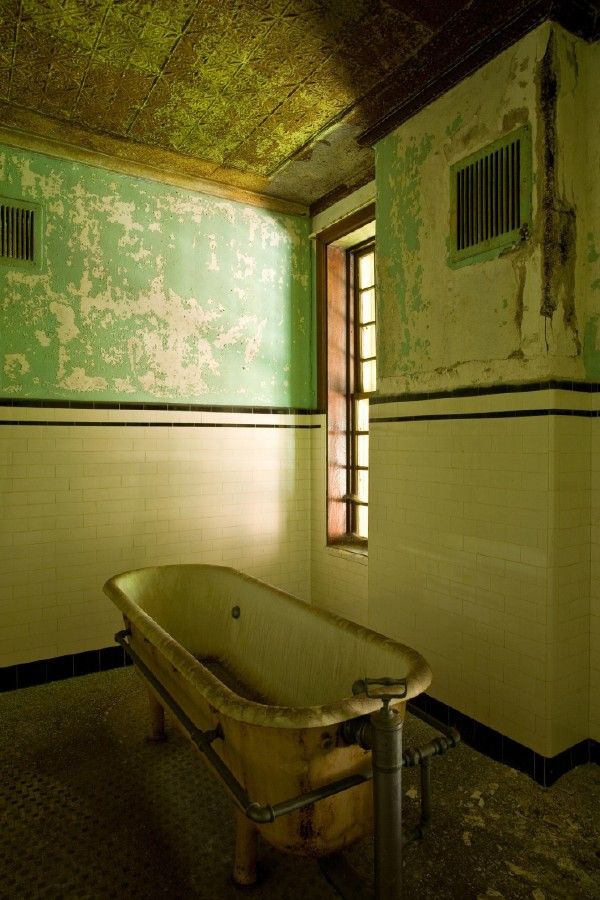

Now a museum of psychiatry, Weston State Hospital in Weston, West Virginia, was closed permanently in 1994.

Source: Mark L. Ruffalo, LCSW

Kirkbride hospitals tended to be large, imposing, Victorian-era buildings surrounded by extensive grounds, often including farmland which was sometimes worked by patients for exercise and therapy. The architecture of these buildings was stately and dramatic, and they were originally well appointed with furnishings and other amenities. Writing in 1854, Kirkbride stated, "There is no reason why an individual who has the misfortune to become insane should, on that account, be deprived of any comfort or even luxury."

The architecture of these buildings was stately and dramatic, and they were originally well appointed with furnishings and other amenities. Writing in 1854, Kirkbride stated, "There is no reason why an individual who has the misfortune to become insane should, on that account, be deprived of any comfort or even luxury."

By 1900, however, the idea of "building-as-cure" had been largely discredited in psychiatric circles, and these massive structures started to become too expensive to properly maintain. In the 20th century, Kirkbride's hospitals became vastly overcrowded with a growing number of psychiatric inpatients. Pilgrim State Hospital in Brentwood, New York, provides an example of this problem of overcrowding. Once the largest psychiatric hospital in the world, Pilgrim housed 13,875 patients at the peak of institutionalization in the 1950s.

Another example of the mass institutionalization of the mid-twentieth century is Weston State Hospital (formerly the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum) in Weston, West Virginia. A few years back, I had the chance to visit this beautiful Kirkbride hospital, once slated for demolition and now a museum of psychiatry. At its peak population, it housed over 2,600 patients in the 1950s. It was designed to treat 250. Weston was closed permanently in 1994.

A few years back, I had the chance to visit this beautiful Kirkbride hospital, once slated for demolition and now a museum of psychiatry. At its peak population, it housed over 2,600 patients in the 1950s. It was designed to treat 250. Weston was closed permanently in 1994.

Traverse City State Hospital now hosts condos, offices, and retail space.

Source: Andrew Jameson, used with permission

Today, most Kirkbride hospitals sit abandoned, neglected, and vandalized, though several are still in operation (at greatly reduced capacity) or have been renovated for uses other than mental health care. Perhaps the best example of mixed-use renovation is the former Traverse City State Hospital in Traverse City, Michigan. Closed in 1989, the hospital has been converted into residential condos, offices, and retail space.

The state mental hospital reflects a bygone era in American psychiatry. Gone are the days of long-term psychiatric hospitalization and housing for the most severely mentally ill. Instead, for better or for worse, patients in need of psychiatric admission are treated for five or seven days and discharged back to the community—sometimes without a place to live.

Instead, for better or for worse, patients in need of psychiatric admission are treated for five or seven days and discharged back to the community—sometimes without a place to live.

While many state mental hospitals in the U.S. have been closed and demolished, their history will stand forever as a remnant of the psychiatry of years past.

"Crazy Quarters" in America: what the closure of budget mental hospitals led to

Remember the classic horror films about mental hospitals - crazy people with aloof faces, insane doctors who are passionate about experiments on patients, inhuman conditions of detention and methods of treatment that raise many questions. There is both truth and fiction in this.

In the 1960s, the process of deinstitutionalization of psychiatry began in the United States: asylums for the mentally ill began to be disbanded and closed en masse. After a short stay in clinics, patients began to be transferred to home care. As a result, some were able to integrate into society, while others ended up on the street or in prison.

Let's tell you what the closure of mental hospitals in America led to and how the authorities are now trying to correct the consequences.

Why mental hospitals began to close

After World War II, the United States, like many other countries, had to get out of the financial crisis. It was decided to reduce the state budget for the maintenance of psychiatric clinics, which led to a deterioration in the situation of the mentally ill.

Public attention to this problem was attracted by an investigation of Life magazine, published in 1946 year. Journalist Albert Meisel interviewed about 3,000 employees of mental hospitals who worked in hospitals during the war.

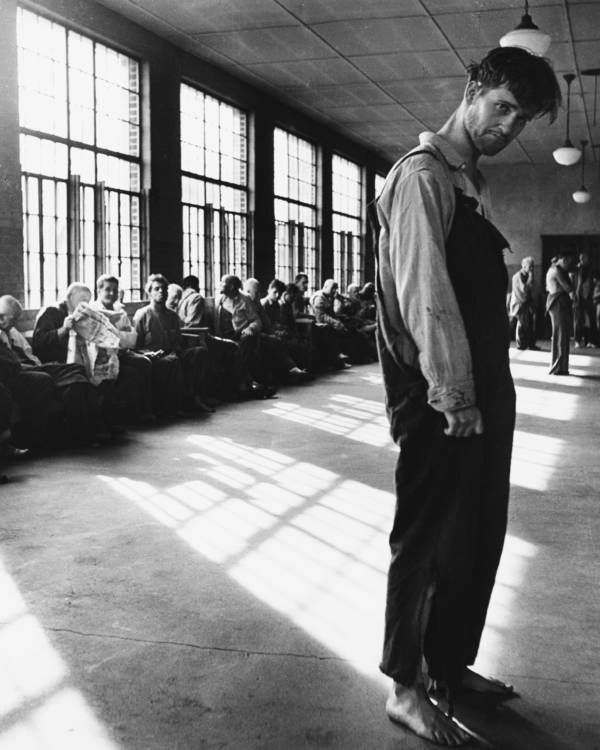

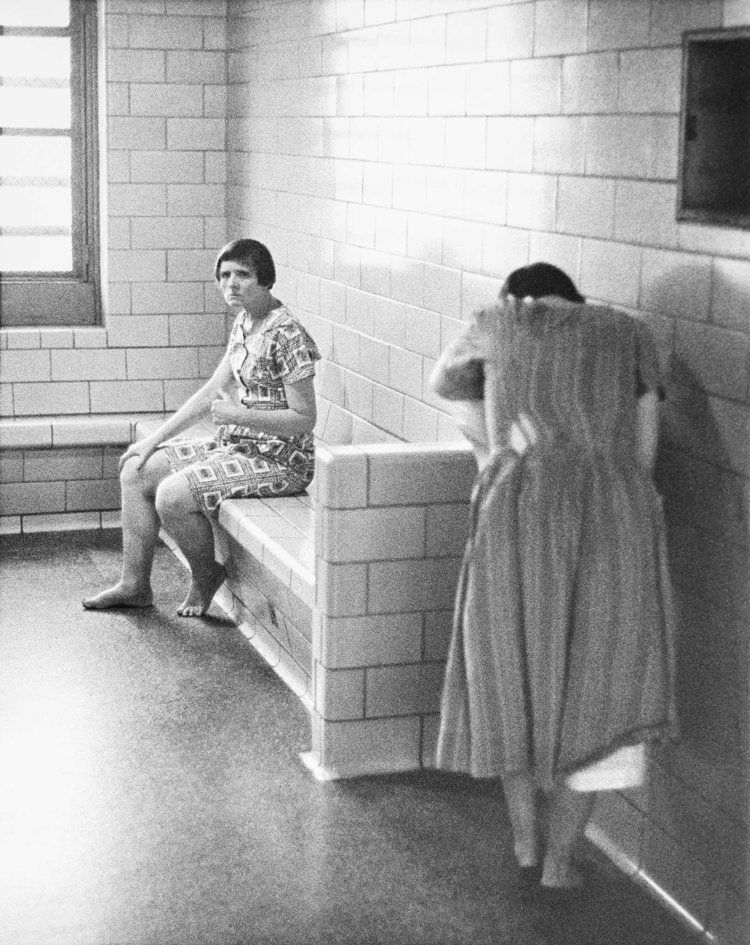

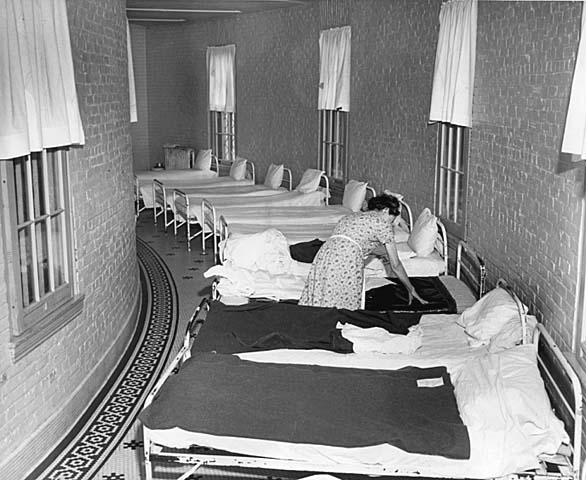

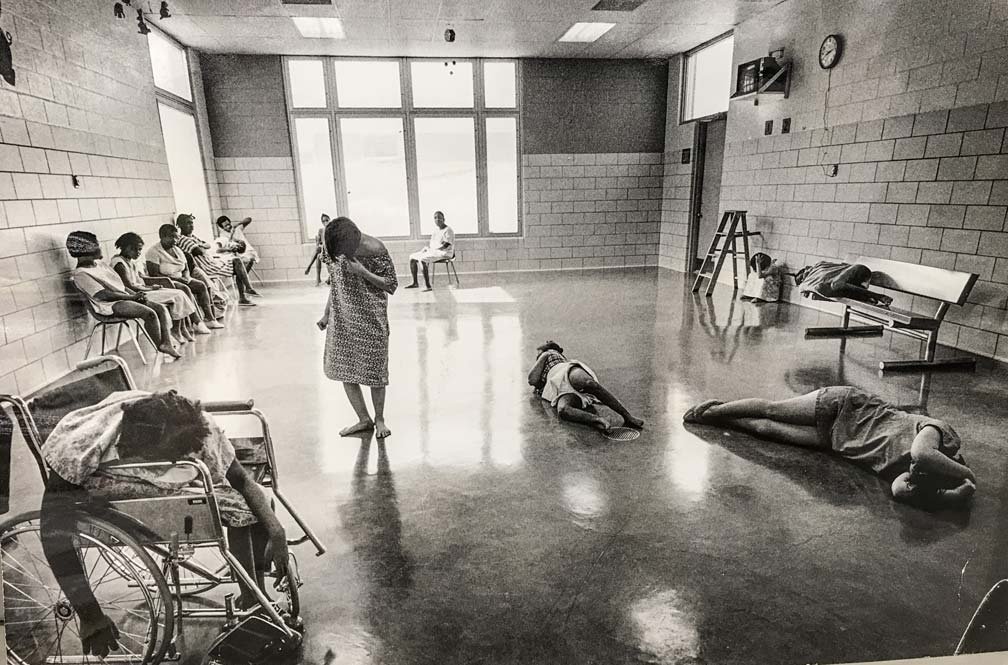

According to the interviewees, the clinics were critically short of staff due to low wages. The hospitals were overcrowded, often patients had to share one bed for two. The patients were malnourished, walked in rags, lived 60-70 people in cramped wards, not intended for such a large number of people.

Outdated and inhumane methods of therapy fueled public outrage. Lobotomy, bloodletting, prescriptions for laxatives instead of neuroleptics, the use of electric shocks, dousing with cold water and other dubious procedures - this is not the kind of "treatment" for which people go to the dispensary.

Patients were bedridden, supposedly so that they could not harm themselves. Sometimes vaccines were tested on patients without their permission, for example, against polio.

The authorities could no longer ignore the problems of mental health care. A series of reforms followed, which radically reshaped the system of mental health care. But did it lead to improvements?

How the process started

For the first time, the Italian professor Franco Basaglia spoke about the need to disband psychiatric hospitals. The scientist believed that medical institutions as places of isolation of the mentally ill should be liquidated.

Some countries in Europe: Italy, Switzerland and Sweden have implemented this concept and completely closed psychiatric hospitals for long-term stays of patients.

This step was made possible by the appearance in 1954 of the first neuroleptic, chlorpromazine. At first it was used as an anesthetic, and then began to be used to treat schizophrenia.

This made it possible to keep the mentally ill in less harsh conditions: rehabilitation centers, institutions for the disabled and at home.

In 1956, the drug was used to treat mental patients in 37 states. Many of them, after completing the course, were able to reintegrate into society, lead a normal life and even get a job.

In the 1960s, with the coming to power of John F. Kennedy, the reform of the psychiatric system began in the USA. So, in 1963, the "Law on Psychiatric Care for the Local Population" was passed.

Plans were made to close inpatient hospitals and instead create outpatient centers to help patients during a flare-up of mental disorders. But due to insufficient funding, not many institutions were able to switch to this format, or rather, less than half of the 1,500 clinics.

But due to insufficient funding, not many institutions were able to switch to this format, or rather, less than half of the 1,500 clinics.

After the insurance reform in 1965, Medicare and Medicaid were introduced for the poor and the elderly. The insurance provided free mental health care, but only in general hospitals. Accordingly, the mentally ill were massively sent to hospitals, nursing homes and rehabilitation centers.

In 1975, regional outpatient temporary detention centers received financial support. Now such institutions were supposed not only to treat patients, but also to help them integrate into social life after discharge: provide housing, train and find work, issue food stamps, etc.

However, funding was again modest - $6 million a year. In 1988, the amount was raised to 19 million, but the project was soon curtailed, federal funding was reduced by 30%, and the costs were shifted to the states.

As a result, the number of places in specialized psychiatric clinics continued to decline. If in 1955 one out of 300 mentally ill people could get a place in the hospital, then by 2004 - one out of 3000.

If in 1955 one out of 300 mentally ill people could get a place in the hospital, then by 2004 - one out of 3000.

more. Many of them, without receiving quality care, ended up on the streets, ended up in prison and died.

The number of mentally ill criminals and the homeless has increased exponentially, as has the number of shootings and fatal crimes.

What led to the massive closure of clinics

The scale of deinstitutionalization carried out from 1955 to 1998 was significant. As a result, the number of places in specialized hospitals for the mentally ill decreased from 339 to 21 per 100,000 Americans.

Today, about 10 million US adults suffer from mental disorders. The annual funding of mental hospitals is only 6% of the budget allocated for medical care.

The massive closure of psychiatric clinics that began in the middle of the last century continues today. About 90% of the mentally ill, who in 1955 would have been sent to hospitals, are now among ordinary people.

Thus, entire neighborhoods appeared in America, in which mostly homeless and mentally unhealthy people live. The most violent most often end up behind bars, the rest live as they have to. Local residents try not to go into areas that can be potentially dangerous for both adults and especially children.

The lack of qualified doctors and the high cost of staying in private clinics mean that most patients cannot afford hospital care.

Private mental health clinics today refuse to accept Medicare and Medicaid payments. As a result, mentally ill people either cannot receive adequate medical care, or are left without it at all.

After leaving the hospital, the authorities expected that relatives should take care of patients. Those without families or spouses often end up homeless or in prison.

In 1984, more than 30% of the homeless suffered from serious mental disorders. Every year their number grew, which continues to this day.

By 2012, there were 10 times more mental patients in American prisons than in specialized clinics.

What is the danger

Permission to freely carry weapons in some states makes the picture really scary.

Thus, in August of this year, several tragedies occurred in the United States involving people who needed psychiatric help.

In one incident in El Paso, a man opened fire on customers in a supermarket, killing 22 people and seriously injuring more than 20.

In Dayton, Ohio, a similar situation occurred: more than 20 people were injured, and another 9 died.

Remember how often in the news they talk about another school shooting, when an unbalanced student, teacher or just a random passerby breaks into an educational institution and shoots random victims.

It also happens that the patients themselves are in no hurry to be treated for their ailments and sell the medicines prescribed to them to drug addicts in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

If the wholesale closure of specialized psychiatric clinics and cuts in the budget for medical care continue, American society will not avoid disaster. The inaction of the authorities and the lack of qualified assistance for those in need of treatment can lead to a mass repetition of tragic stories and an increase in the number of innocent victims.

Read our articles about how attitudes towards the mentally ill have changed and about the structure of the system of psychiatric hospitals in Russia:

From asylums for the possessed by the devil to humane treatment: how psychiatric hospitals have changed

Compulsory psychiatry in Russia. How the system works from the inside.

Letchworth Clinic and the History of American Psychiatry: samsebeskazal - LiveJournal

Letchworth Clinic and the History of American Psychiatry. From isolation, prison regime, torture and suffering, to humanization, deinstitutionalization and mass closure of mental hospitals.

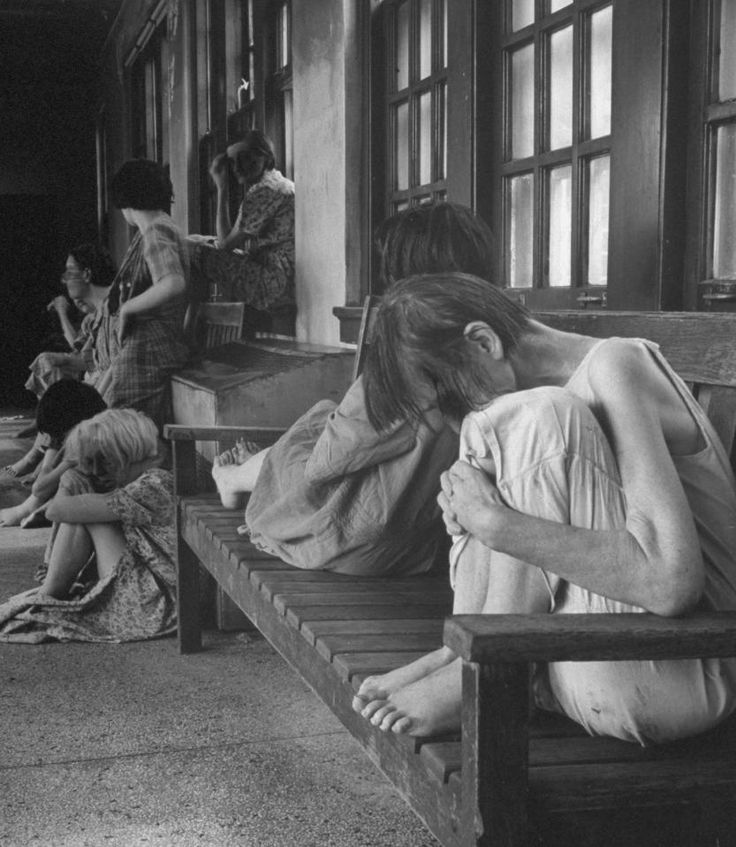

For a long time, both in America and all over the world, there was a problem of treating mentally ill people. More precisely, there was no treatment as such. There were isolated attempts to somehow analyze and systematize their condition and, if possible, try to improve it. The violent and active ones were simply isolated, the quiet ones were looked after. Psychiatry, as a science, appeared only in the 19th century and moved forward in very small steps, making many mistakes. What are today called psychiatric clinics at that time were only asylums, more like prisons, where unfortunate sick people were kept in the most terrible conditions. Any deviation from normal behavior was severely punished. The sick were tied up, locked in dark rooms, doused with cold water and beaten. Since there was no normal diagnosis of diseases, and they were often placed in psychiatric hospitals for completely ridiculous reasons, there were often completely healthy people with the sick, who could well go crazy about the conditions in which they found themselves.

There were isolated attempts to somehow analyze and systematize their condition and, if possible, try to improve it. The violent and active ones were simply isolated, the quiet ones were looked after. Psychiatry, as a science, appeared only in the 19th century and moved forward in very small steps, making many mistakes. What are today called psychiatric clinics at that time were only asylums, more like prisons, where unfortunate sick people were kept in the most terrible conditions. Any deviation from normal behavior was severely punished. The sick were tied up, locked in dark rooms, doused with cold water and beaten. Since there was no normal diagnosis of diseases, and they were often placed in psychiatric hospitals for completely ridiculous reasons, there were often completely healthy people with the sick, who could well go crazy about the conditions in which they found themselves.

Bloodletting, laxatives, cold water pouring, wheel spinning, physical punishment, and restraints such as shackles were used as “treatment”. The first changes in attitude towards mentally ill people happened at the very end of the 18th century in France. Thanks to the doctor Philippe Pinel and the French Revolution, a movement for the humanization of psychiatric hospitals began, which led to a radical change in the conditions of the patients. The chains were removed from the mentally ill, they were transferred from gloomy dungeons to bright rooms, and they were also allowed to move freely around the territory. A hospital regime was established, which included medical rounds, medical procedures, and much more.

The first changes in attitude towards mentally ill people happened at the very end of the 18th century in France. Thanks to the doctor Philippe Pinel and the French Revolution, a movement for the humanization of psychiatric hospitals began, which led to a radical change in the conditions of the patients. The chains were removed from the mentally ill, they were transferred from gloomy dungeons to bright rooms, and they were also allowed to move freely around the territory. A hospital regime was established, which included medical rounds, medical procedures, and much more.

Pinel's innovation was crowned with success: fears that the insane, not chained, would be dangerous both for themselves and for others, did not materialize. In the well-being of many people who were locked up for decades, significant improvements appeared in a short time, and these patients were released. Unfortunately, all these progressive changes have little effect on clinics and shelters outside of a number of European countries.

One of the high-profile stories that led to reforms in the United States was the investigation of 23-year-old journalist Nellie Bly, who disguised herself as a patient entered the women's psychiatric clinic on Blackwell Island and escaped from there with the help of Joseph Pulitzer wrote a series of articles subsequently collected into a book “10 days in a lunatic asylum”, where she described all the horrors and sufferings of the patients. If interested, this book has been translated into Russian.

In 1911, a completely new type of medical institution was opened near New York, the concept of which was supposed to radically change the way mentally ill people are kept and treated. The new hospital was named after William Pryor Letchworth, a Quaker, successful businessman and renowned philanthropist. After earning a decent fortune, at the age of 50, Letchworth retired to devote the rest of his life to the Quaker ideals of charity and concern for the welfare of people less fortunate than him. He was especially worried about the fate of disabled children, so he went to Europe, where he actively studied new methods of treating mental illness and epilepsy.

He was especially worried about the fate of disabled children, so he went to Europe, where he actively studied new methods of treating mental illness and epilepsy.

Assuming the presidency of the New York State Board of Charities in 1878, he began to promote a new progressive model of mental health care that was radically different from anything that existed at the time. Instead of large, cramped and always overcrowded orphanages and almshouses, more like prisons than hospitals - an autonomous and self-sufficient village consisting of many small cottages located in the bosom of nature next to a working farm. Instead of isolation and torment - a dignified and productive way of life that helps to cure the sick or stabilize their condition. All this must be done under the supervision of the best doctors, researchers and psychiatrists.

New York State has approved Letchworth's plan and allocated diseased land for the construction of a new facility. Unfortunately, William Letchworth died before the building was completed, but he knew that the future clinic would bear his name - Letchworth Village (Lechworth Village).

The clinic received its first patients on July 10, 1911, and quite soon the concept proposed by Letchworth was recognized as successful and the clinic began to expand. Under the guidance of an experienced psychiatrist Charles Little, the "Village" grew to 130 administrative, residential and medical buildings and was ready to receive up to 3,000 patients. The village was beautifully planned and well built. It had its own boiler house and power plant.

Patients, according to their abilities, helped with housekeeping, worked in the fields, cared for animals, cooked, sewed, cleaned and did many other useful things. Some received special training and acquired professional skills - they worked as carpenters, repaired shoes, were engaged in metalworking and many other things.

Dr. Little and his staff conducted research into the causes of mental retardation and offered courses to physicians visiting from all over the US and Europe. At its peak, the village employed about 10,000 locals. It was the finest facility of its kind in the entire country, but it unfortunately fell victim to its own success.

It was the finest facility of its kind in the entire country, but it unfortunately fell victim to its own success.

In 1935, Letchworth Village reached its maximum capacity of 3,000, and the flow of new patients continued unabated. Patients were transferred from other psychiatric clinics, such as, for example, New York's Bellevue Hospital, which by that time itself had long been overcrowded. As a result, the number of patients grew every year, but funding remained at the same level. This has become a real problem.

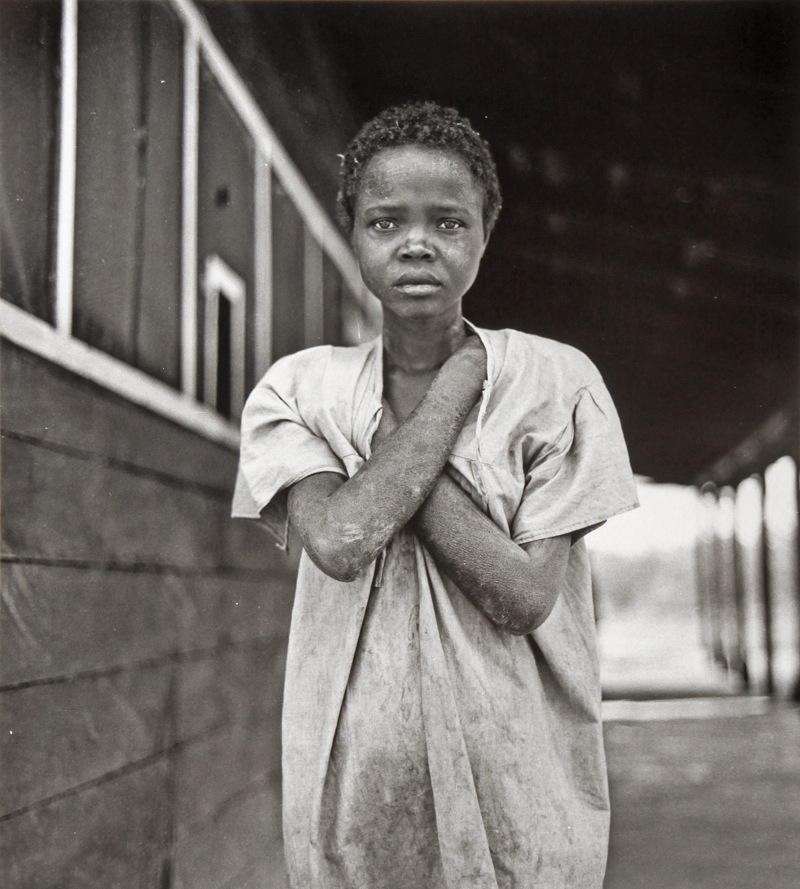

By the end of the 1960s, there were more than 5,000 patients in the clinic. Due to overcrowding, patients were forced to live in cramped wards with 70 people in one room. Visitors commented that the children in the clinic were malnourished and looked ill. Reports indicated that Letchworth lacked food, water, and many other things that patients needed to live a normal life. In addition, children were constantly subjected to testing, abuse and neglect by the staff.

For example, in February 1950, Dr. Hilary Koprowski administered a polio vaccine he had developed to 20 juvenile Letchworth residents. At first, he tested the vaccine on himself, and then he needed other patients to continue the study. People held in psychiatric clinics at that time were practically powerless and served as excellent material for such scientific experiments. Fortunately, none of the children experienced adverse events as a result of trials of this vaccine.

In 1972, ABC News aired an investigative program called "Willowbrook - The Last Great Shame" which described how patients were kept in psychiatric hospitals in New York State. Journalist Geraldo Rivera visited the nation's largest boarding school for mentally retarded children, Willowbrook, in New York's Staten Island, and was shocked by what he saw. The footage he took inside one of the buildings is impossible to watch without tears. Children were kept in terrible conditions like animals. Being in complete isolation from society, they did not even have any minimal proper care. They spent all their days sitting in dimly lit rooms without socializing, without study or therapy, and were essentially left to their own devices. And so day after day, month after month, year after year. Due to budget cuts carried out by Governor Nelson Rockefeller, the severely cut staff of the boarding school was physically unable to cope with the huge number of patients. There was not enough time even for normal feeding of children, not to mention something more serious. Due to the lack of care, many children spent whole days in clothes and in their own feces. The only thing the others were wearing was a straitjacket. Even before they had time to become adults, the unfortunate children actually just lived out their lives surrounded by their own kind, completely unaware of how the world looks outside their ward. Seeing the real picture, Rivera included other similar institutions in his investigation, including Letchworth. Unfortunately, the picture there was not much different from what Rivera saw in Willowbrook.

They spent all their days sitting in dimly lit rooms without socializing, without study or therapy, and were essentially left to their own devices. And so day after day, month after month, year after year. Due to budget cuts carried out by Governor Nelson Rockefeller, the severely cut staff of the boarding school was physically unable to cope with the huge number of patients. There was not enough time even for normal feeding of children, not to mention something more serious. Due to the lack of care, many children spent whole days in clothes and in their own feces. The only thing the others were wearing was a straitjacket. Even before they had time to become adults, the unfortunate children actually just lived out their lives surrounded by their own kind, completely unaware of how the world looks outside their ward. Seeing the real picture, Rivera included other similar institutions in his investigation, including Letchworth. Unfortunately, the picture there was not much different from what Rivera saw in Willowbrook. Insufficient funding here again led to a shortage of personnel and the same terrible conditions for the unfortunate sick children who could not even be properly dressed and fed.

Insufficient funding here again led to a shortage of personnel and the same terrible conditions for the unfortunate sick children who could not even be properly dressed and fed.

Rivera's investigations uncovered massive cases of negligence, abuse, inadequate care, and physical and sexual abuse by staff towards mentally retarded patients. As a result of the investigation, a lawsuit was filed by the parents of the children held in the clinics against the governor of the state, Nelson Rockefeller. The publicity caused by this investigation was the main factor that contributed to the adoption of the federal law "On Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons" adopted in 1980 and numerous reforms that changed the attitude towards patients in psychiatric clinics in the United States.

At the same time, under the influence of public opinion in the United States, the process of deinstitutionalization began - the replacement of a long stay in a psychiatric clinic with community care with the active participation of specialized specialists, social workers and services. This made it possible to prevent the development of hospitalism in patients, protect their rights and remove the separation from society and social life.

This made it possible to prevent the development of hospitalism in patients, protect their rights and remove the separation from society and social life.

The process took place in different states in different ways. Somewhere, like in California, active processes of deinstitutionalization begin to take place already in the 50s and 60s of the last century, and somewhere, like in the state of New York, everything remains almost unchanged for another three decades, and only thanks to investigations and raised wave of public discontent, begin to carry out the necessary reforms. Interestingly, the change in public opinion was influenced not only by sharp reports, investigations and litigation, but also by films. One of them was the famous film by Milos Forman "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest", filmed in 1975 year.

The emergence of psychotropic medications, budgetary reforms, and most importantly, a change in the mentality of society in relation to mentally ill people, led to the closure of a huge number of psychiatric hospitals throughout the country. For comparison, in 1955, 560,000 people were kept in American psychiatric clinics (this is the largest number of patients in history). By 1980, their number was reduced to 130,000. In the same 1955, there were 340 beds in psychiatric hospitals per 100,000 inhabitants of the United States. In 2005 there were only 17 left.

For comparison, in 1955, 560,000 people were kept in American psychiatric clinics (this is the largest number of patients in history). By 1980, their number was reduced to 130,000. In the same 1955, there were 340 beds in psychiatric hospitals per 100,000 inhabitants of the United States. In 2005 there were only 17 left.

Today, 90 percent of those who would have been placed in a psychiatric hospital in the middle of the last century are not in it. As a result of the reforms, many patients who would previously have faced lifelong isolation have successfully integrated into society. The decline in the number of patients who need a long stay in the hospital walls has led to the fact that most of the old American hospitals have been closed. Letchworth Village is one of them.

Unfortunately, there is a downside to all this. Many of those who have mental problems and would have ended up in the hospital before are now homeless. Studies show that 30 to 50 percent of people living on the street have mental illnesses and disorders. All this, in turn, has led to the fact that those who are aggressive, uncontrollable and do not obey the requirements often end up in prisons, since their maintenance there is cheaper than that in psychiatric clinics.

All this, in turn, has led to the fact that those who are aggressive, uncontrollable and do not obey the requirements often end up in prisons, since their maintenance there is cheaper than that in psychiatric clinics.

Despite all the existing problems, American society has taken a giant step towards the humanization of psychiatry and has radically changed its attitude towards people with mental illness. And these changes happened primarily not thanks to the authorities (although their participation was very important), but thanks to journalists and the wave of public discontent raised by them, followed by active criticism of the existing system, lawsuits, emerging anti-psychiatric movements and even movies. In fact, due to the fact that society has ceased to ignore and hush up the problem.

From my small foray into the desert, a decent longread turned out, which is difficult to somehow normally illustrate in the Facebook format. I will insert here some photos from Letchworth, but if you are interested in the topic and want to immerse yourself in the atmosphere, then it is better to watch my video on YouTube - https://www.