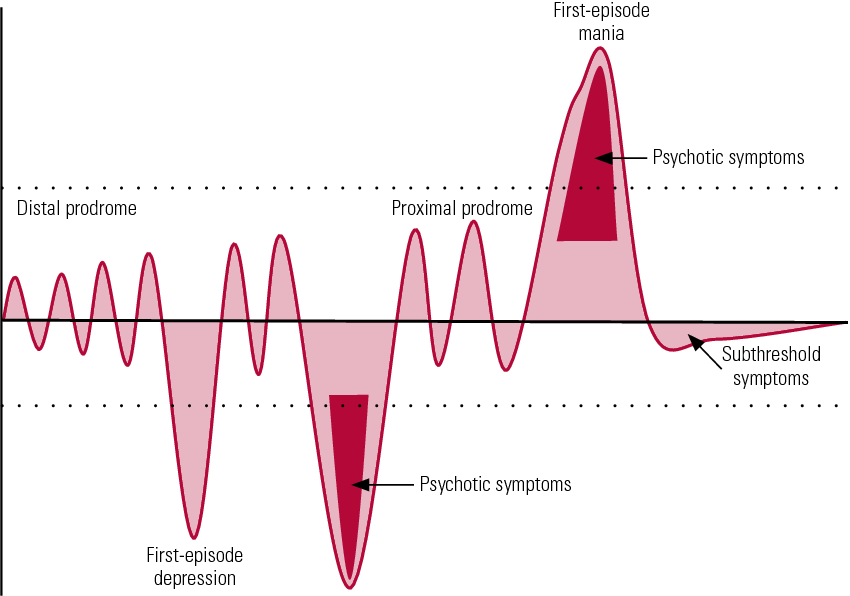

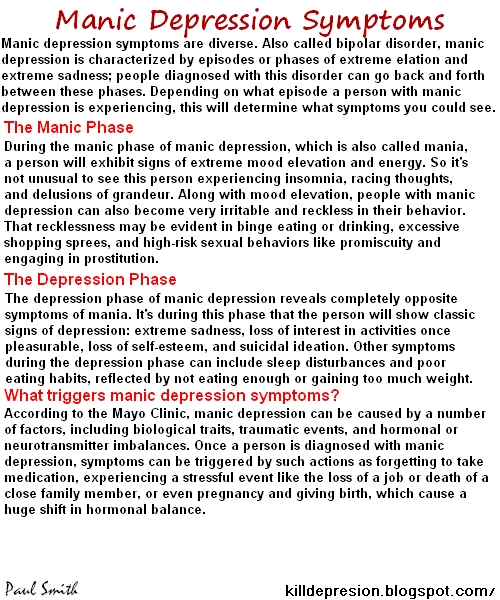

Manic depressive episode length

NIMH » Bipolar Disorder

Do you have periods of time when you feel unusually “up” (happy and outgoing, or irritable), but other periods when you feel “down” (unusually sad or anxious)? During the “up” periods, do you have increased energy or activity and feel a decreased need for sleep, while during the “down” times you have low energy, hopelessness, and sometimes suicidal thoughts? Do these symptoms of fluctuating mood and energy levels cause you distress or affect your daily functioning? Some people with these symptoms have a lifelong but treatable mental illness called bipolar disorder.

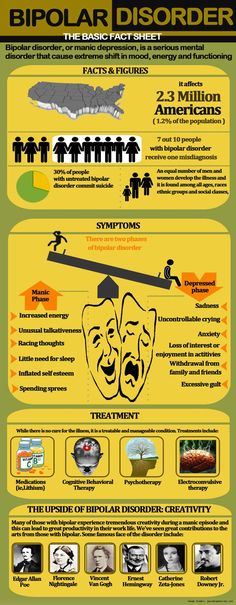

What is bipolar disorder?

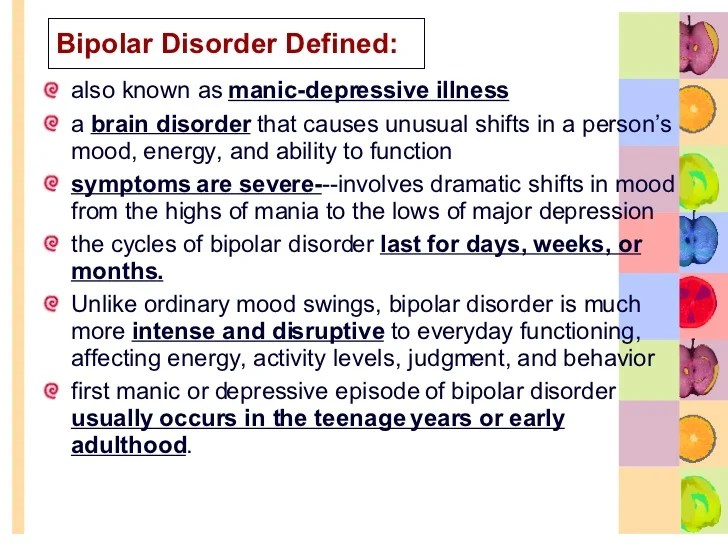

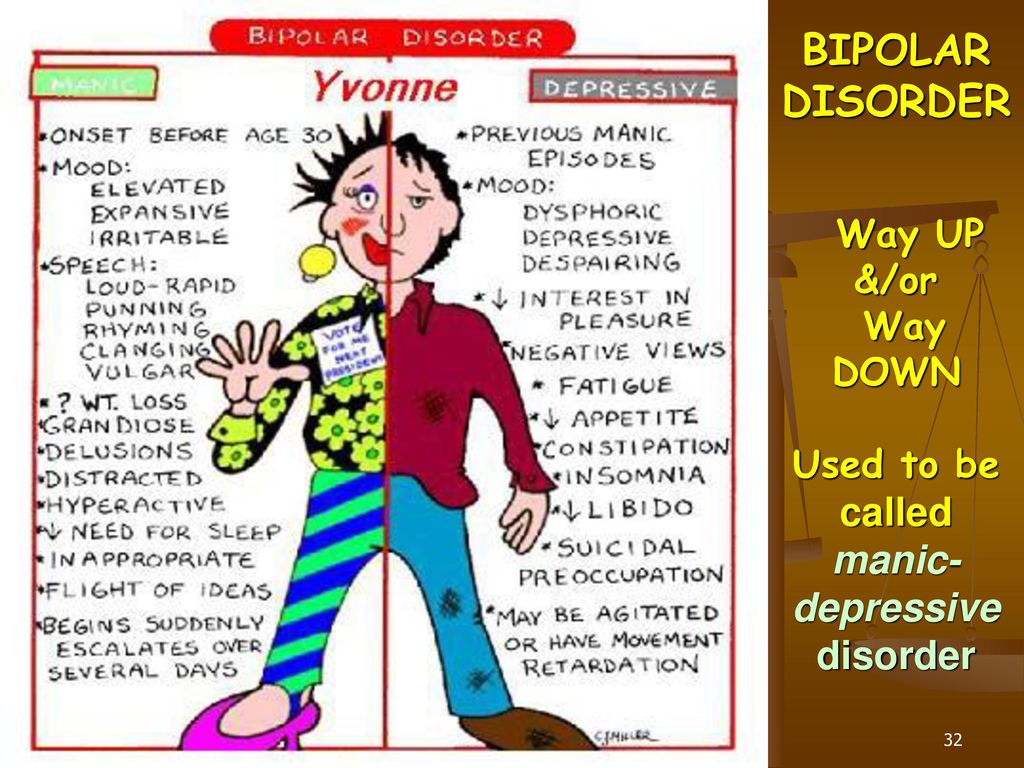

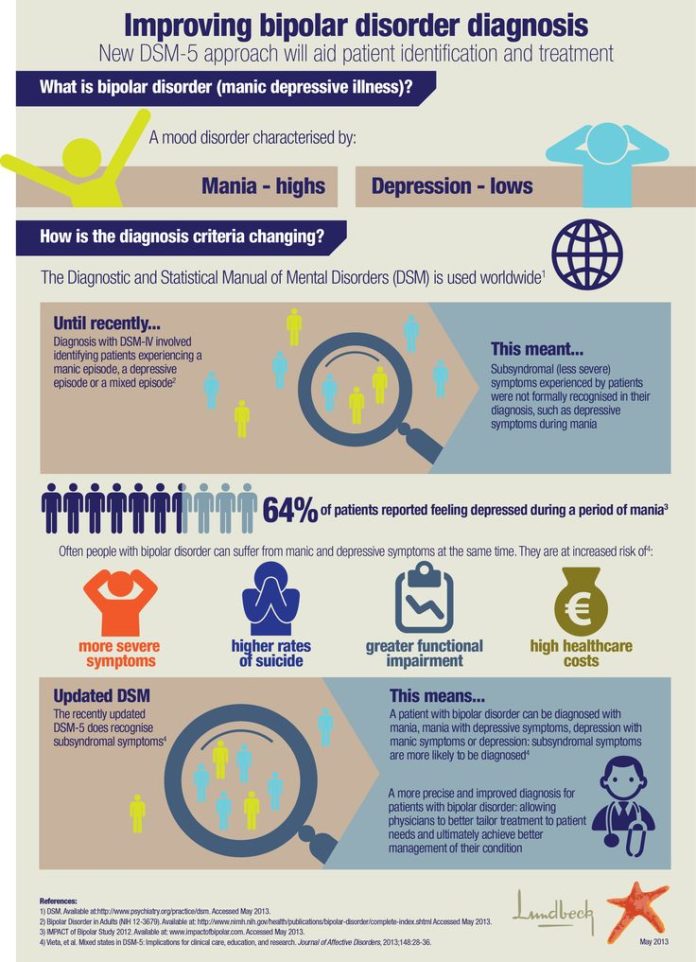

Bipolar disorder is a mental illness that can be chronic (persistent or constantly reoccurring) or episodic (occurring occasionally and at irregular intervals). People sometimes refer to bipolar disorder with the older terms “manic-depressive disorder” or “manic depression.”

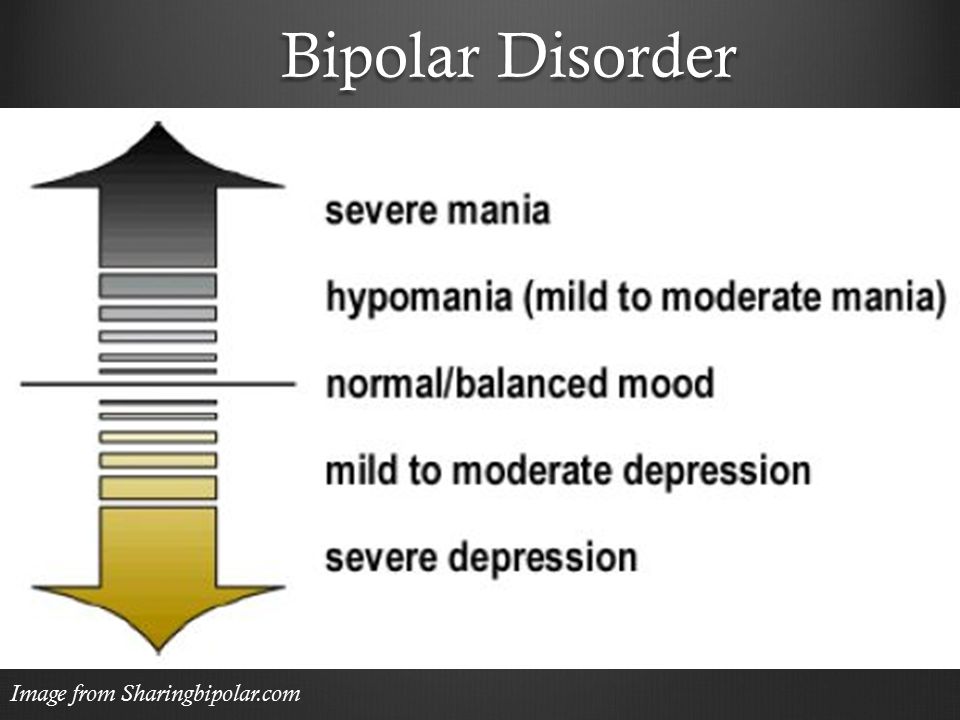

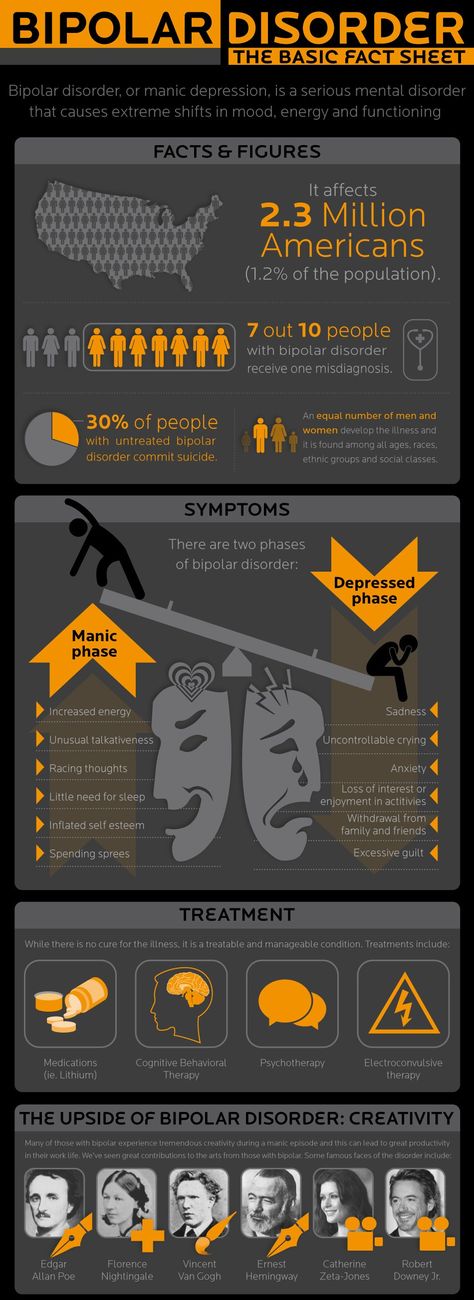

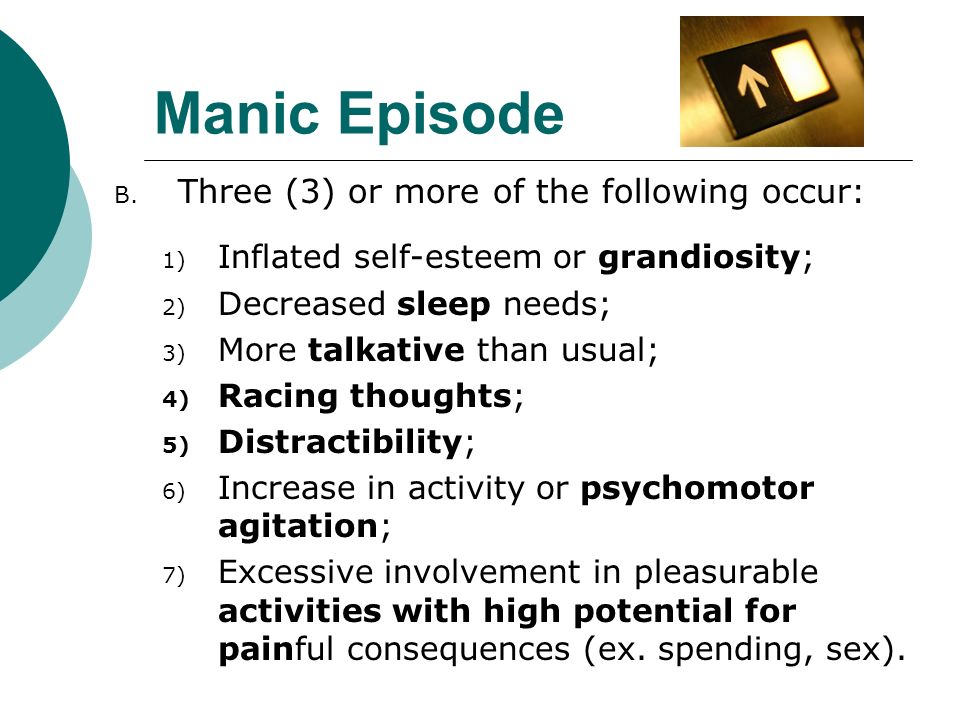

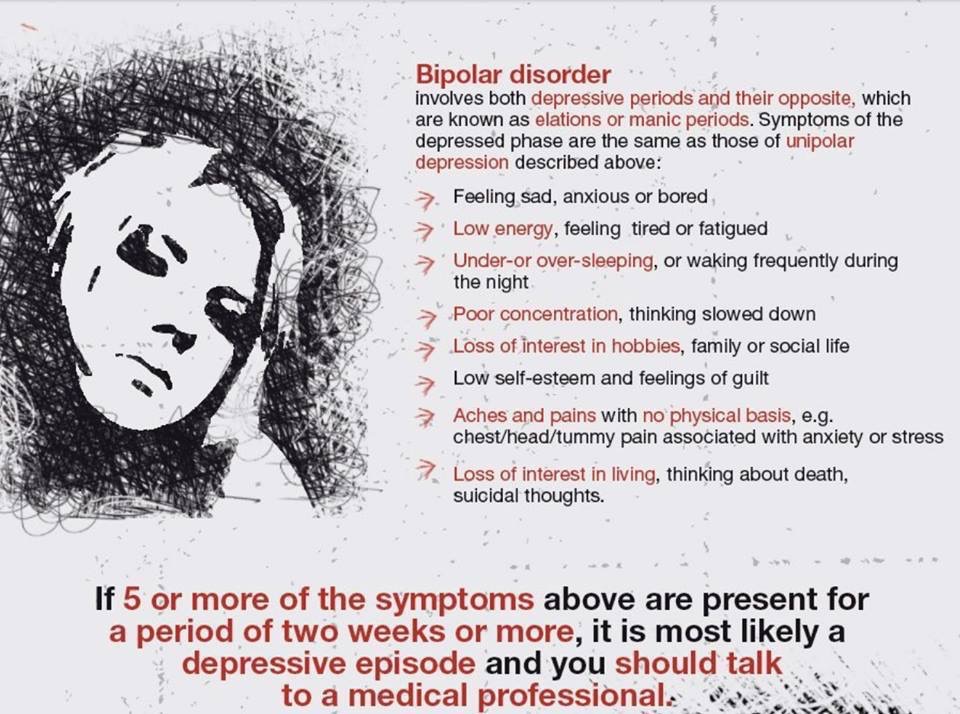

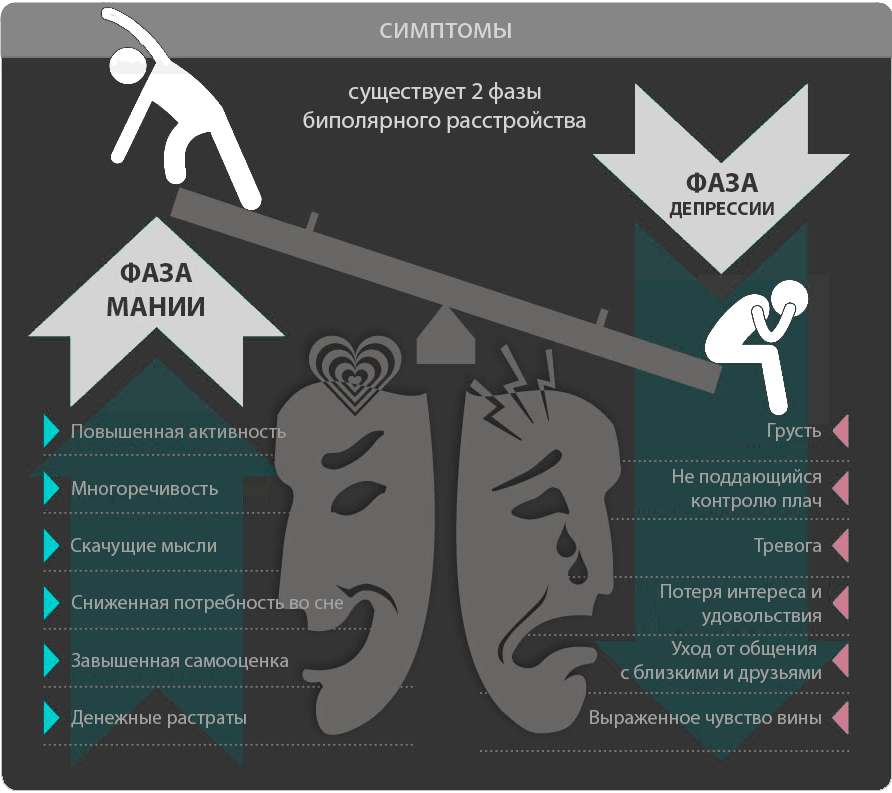

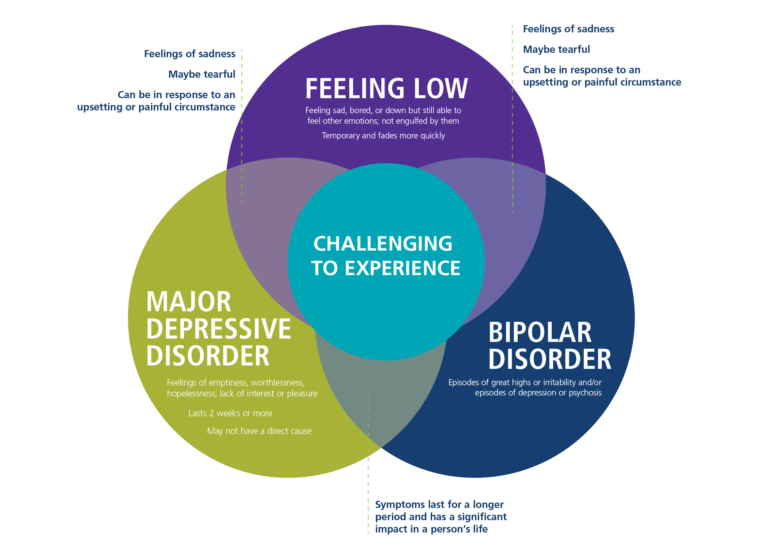

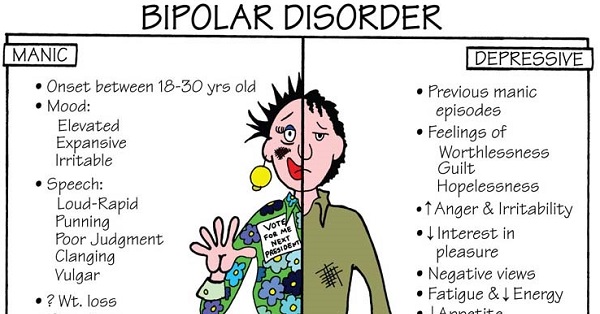

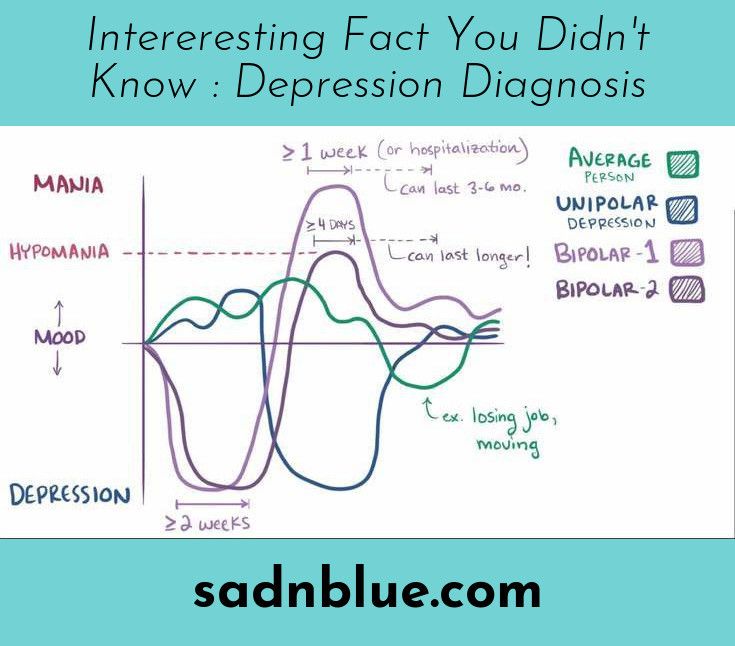

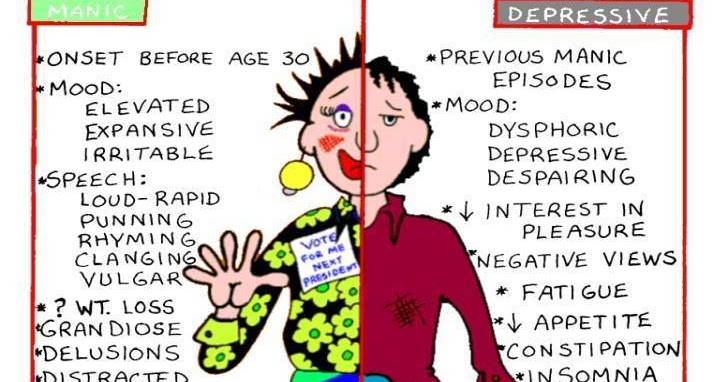

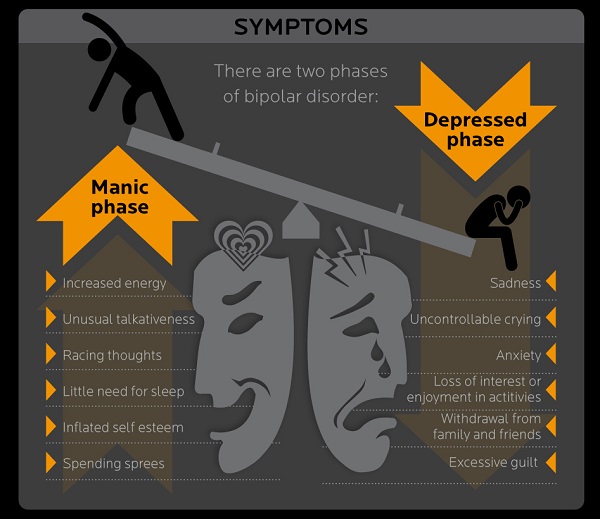

Everyone experiences normal ups and downs, but with bipolar disorder, the range of mood changes can be extreme. People with the disorder have manic episodes, or unusually elevated moods in which the individual might feel very happy, irritable, or “up,” with a marked increase in activity level. They might also have depressive episodes, in which they feel sad, indifferent, or hopeless, combined with a very low activity level. Some people have hypomanic episodes, which are like manic episodes, but not severe enough to cause marked impairment in social or occupational functioning or require hospitalization.

Most of the time, bipolar disorder symptoms start during late adolescence or early adulthood. Occasionally, children may experience bipolar disorder symptoms. Although symptoms may come and go, bipolar disorder usually requires lifelong treatment and does not go away on its own. Bipolar disorder can be an important factor in suicide, job loss, ability to function, and family discord. However, proper treatment can lead to better functioning and improved quality of life.

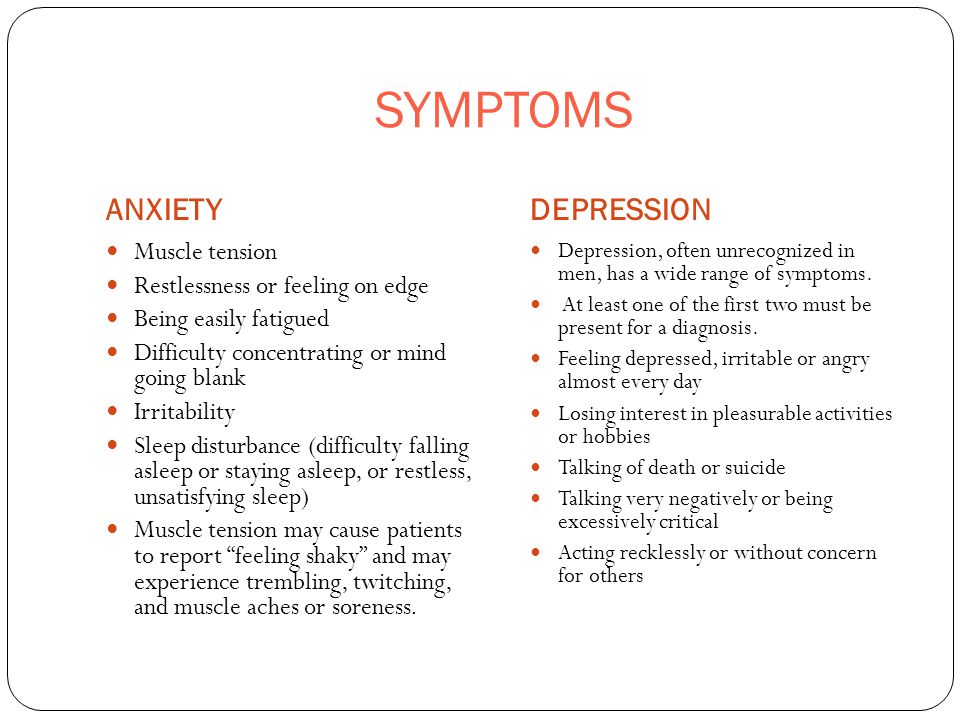

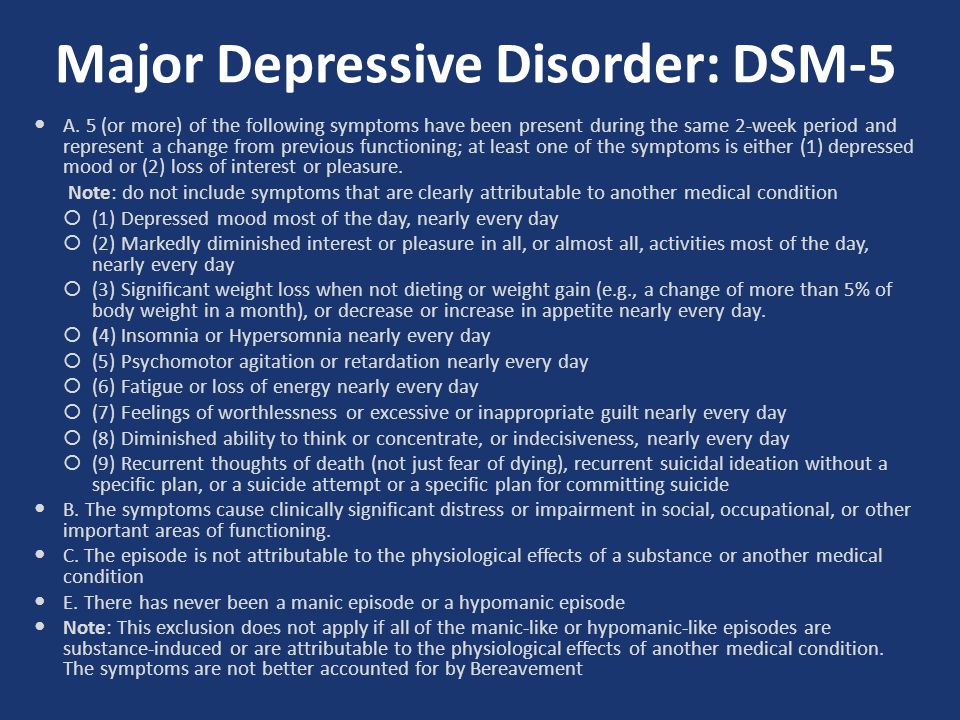

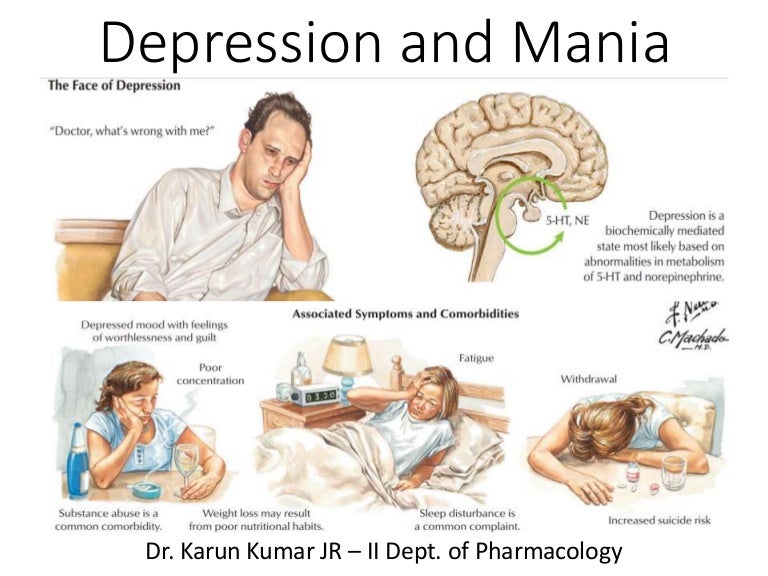

What are the symptoms of bipolar disorder?

Symptoms of bipolar disorder can vary. An individual with the disorder may have manic episodes, depressive episodes, or “mixed” episodes. A mixed episode has both manic and depressive symptoms. These mood episodes cause symptoms that last a week or two, or sometimes longer. During an episode, the symptoms last every day for most of the day. Feelings are intense and happen with changes in behavior, energy levels, or activity levels that are noticeable to others. In between episodes, mood usually returns to a healthy baseline. But in many cases, without adequate treatment, episodes occur more frequently as time goes on.

An individual with the disorder may have manic episodes, depressive episodes, or “mixed” episodes. A mixed episode has both manic and depressive symptoms. These mood episodes cause symptoms that last a week or two, or sometimes longer. During an episode, the symptoms last every day for most of the day. Feelings are intense and happen with changes in behavior, energy levels, or activity levels that are noticeable to others. In between episodes, mood usually returns to a healthy baseline. But in many cases, without adequate treatment, episodes occur more frequently as time goes on.

| Symptoms of a Manic Episode | Symptoms of a Depressive Episode |

|---|---|

| Feeling very up, high, elated, or extremely irritable or touchy | Feeling very down or sad, or anxious |

| Feeling jumpy or wired, more active than usual | Feeling slowed down or restless |

| Racing thoughts | Trouble concentrating or making decisions |

| Decreased need for sleep | Trouble falling asleep, waking up too early, or sleeping too much |

| Talking fast about a lot of different things (“flight of ideas”) | Talking very slowly, feeling unable to find anything to say, or forgetting a lot |

| Excessive appetite for food, drinking, sex, or other pleasurable activities | Lack of interest in almost all activities |

| Feeling able to do many things at once without getting tired | Unable to do even simple things |

| Feeling unusually important, talented, or powerful | Feeling hopeless or worthless, or thinking about death or suicide |

Some people with bipolar disorder may have milder symptoms than others. For example, hypomanic episodes may make an individual feel very good and productive; they may not feel like anything is wrong. However, family and friends may notice the mood swings and changes in activity levels as unusual behavior, and depressive episodes may follow hypomanic episodes.

For example, hypomanic episodes may make an individual feel very good and productive; they may not feel like anything is wrong. However, family and friends may notice the mood swings and changes in activity levels as unusual behavior, and depressive episodes may follow hypomanic episodes.

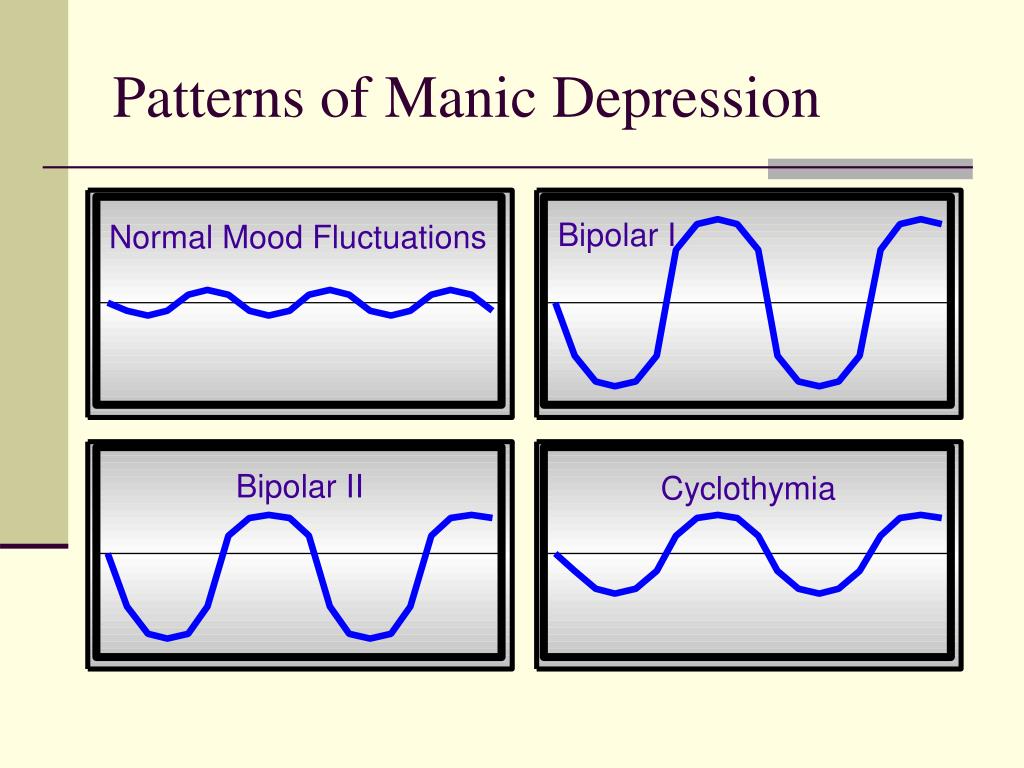

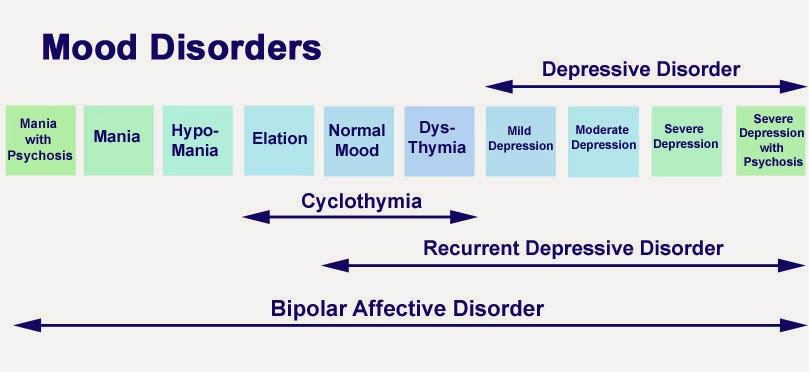

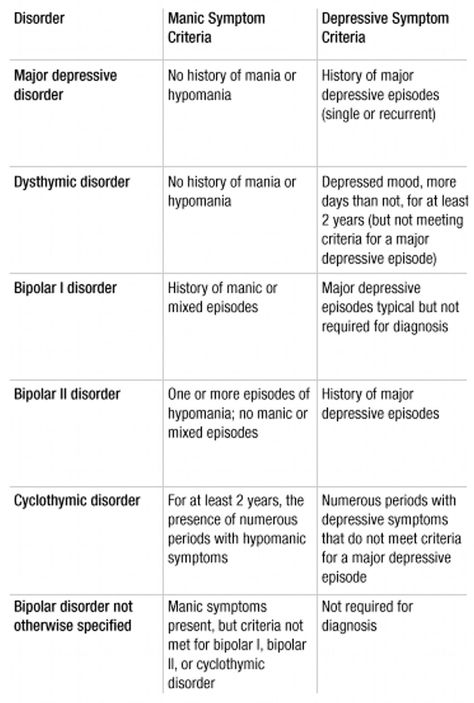

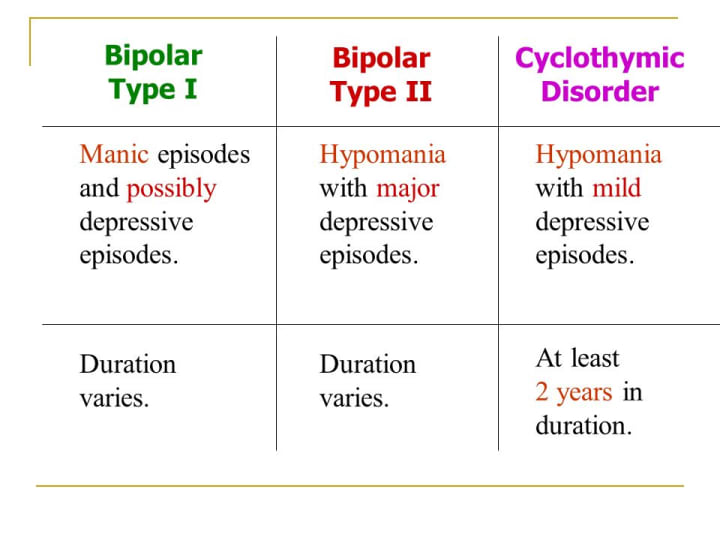

Types of Bipolar Disorder

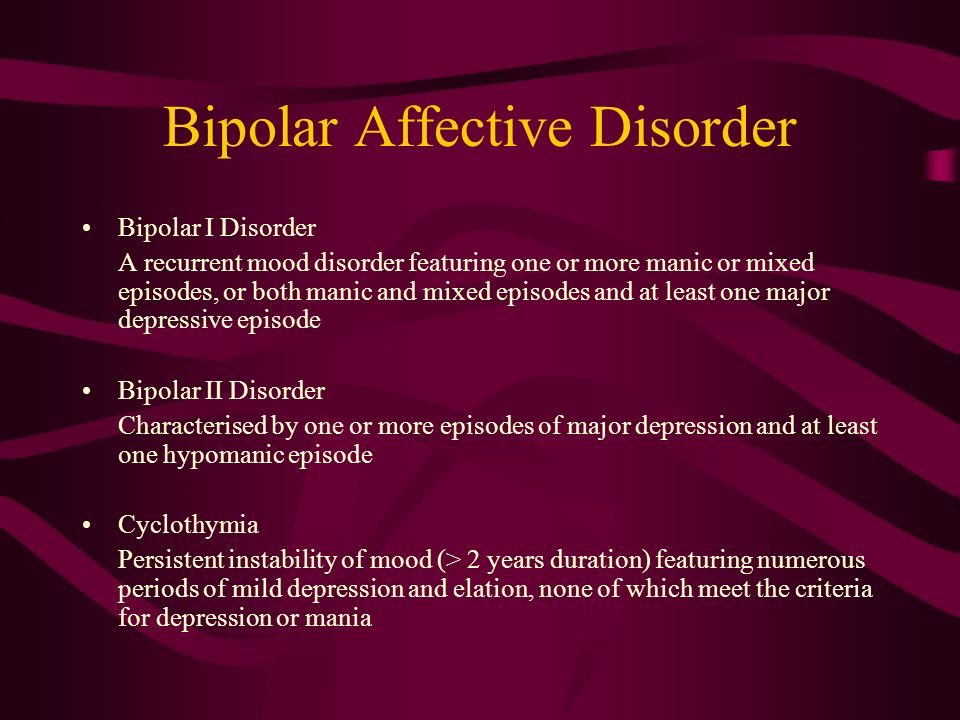

People are diagnosed with three basic types of bipolar disorder that involve clear changes in mood, energy, and activity levels. These moods range from manic episodes to depressive episodes.

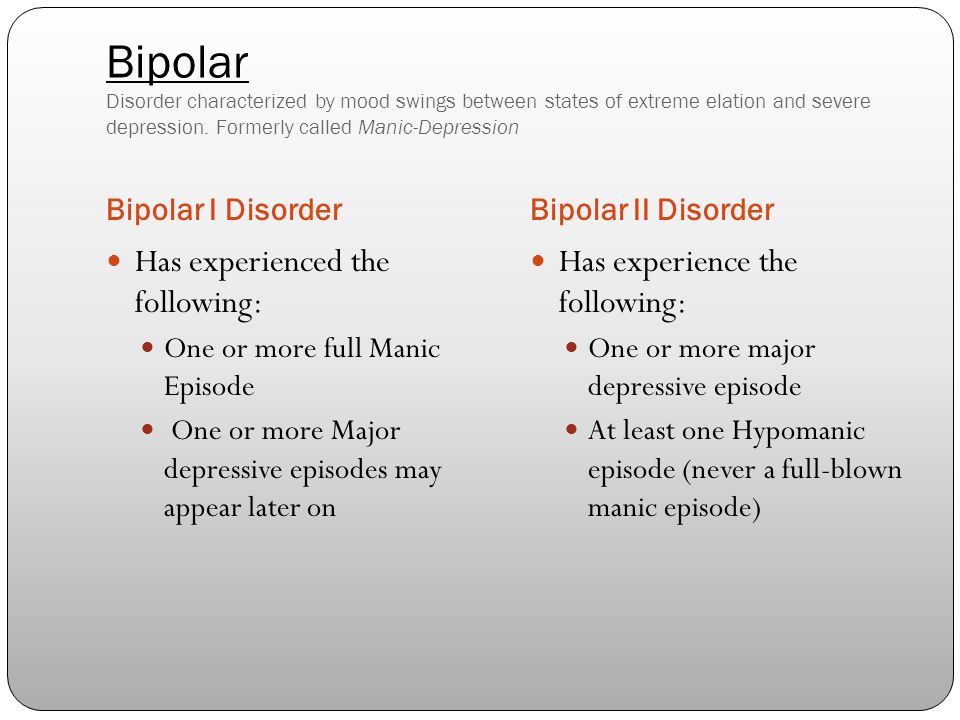

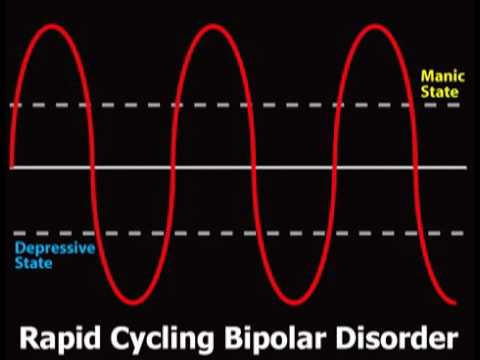

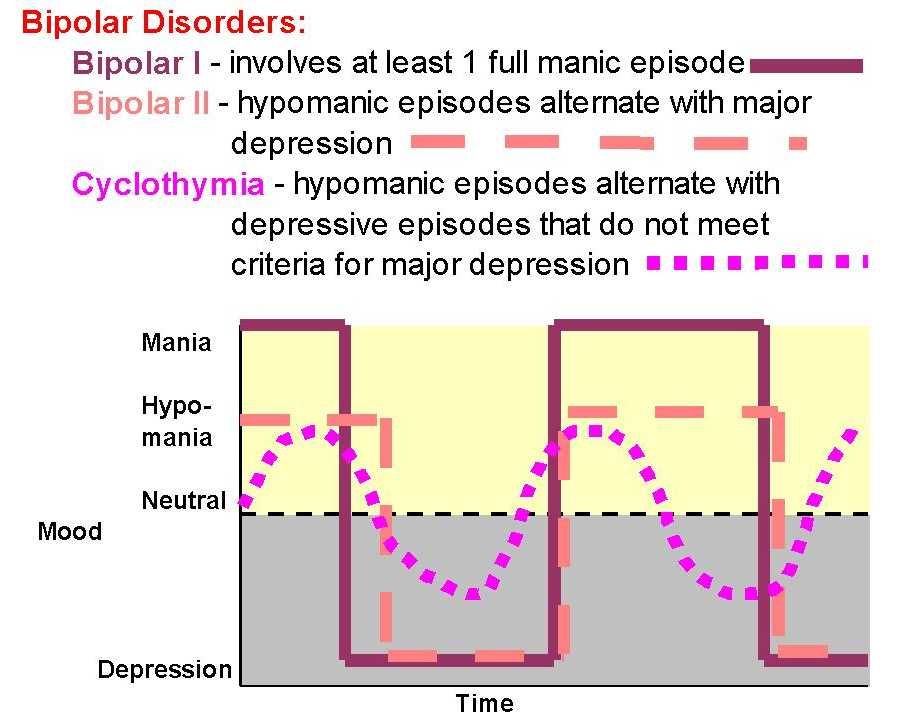

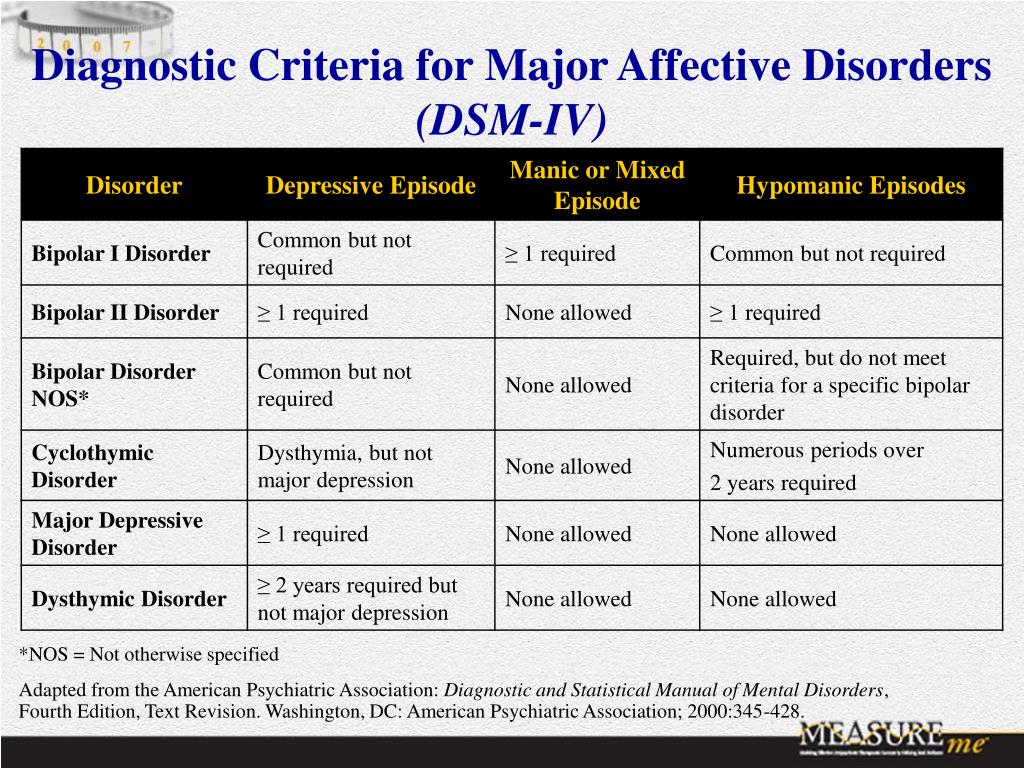

- Bipolar I disorder is defined by manic episodes that last at least 7 days (most of the day, nearly every day) or when manic symptoms are so severe that hospital care is needed. Usually, separate depressive episodes occur as well, typically lasting at least 2 weeks. Episodes of mood disturbance with mixed features are also possible. The experience of four or more episodes of mania or depression within a year is termed “rapid cycling.”

- Bipolar II disorder is defined by a pattern of depressive and hypomanic episodes, but the episodes are less severe than the manic episodes in bipolar I disorder.

- Cyclothymic disorder (also called cyclothymia) is defined by recurrent hypomanic and depressive symptoms that are not intense enough or do not last long enough to qualify as hypomanic or depressive episodes.

“Other specified and unspecified bipolar and related disorders” is a diagnosis that refers to bipolar disorder symptoms that do not match the three major types of bipolar disorder outlined above.

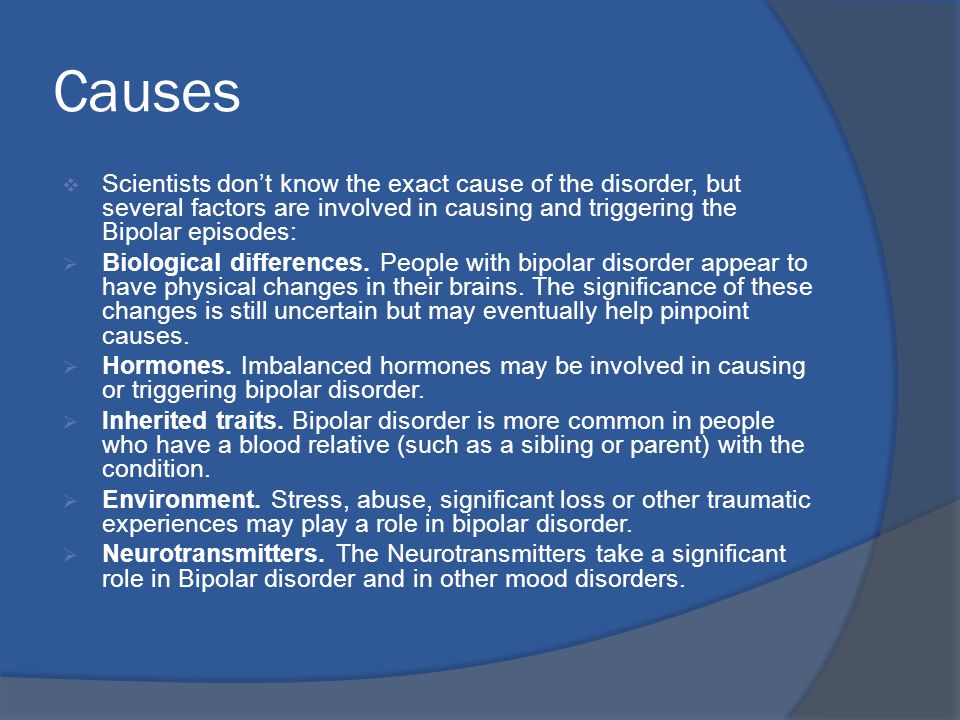

What causes bipolar disorder?

The exact cause of bipolar disorder is unknown. However, research suggests that a combination of factors may contribute to the illness.

Genes

Bipolar disorder often runs in families, and research suggests this is mostly explained by heredity—people with certain genes are more likely to develop bipolar disorder than others. Many genes are involved, and no one gene can cause the disorder.

But genes are not the only factor. Studies of identical twins have shown that one twin can develop bipolar disorder while the other does not. Though people with a parent or sibling with bipolar disorder are more likely to develop it, most people with a family history of bipolar disorder will not develop it.

Though people with a parent or sibling with bipolar disorder are more likely to develop it, most people with a family history of bipolar disorder will not develop it.

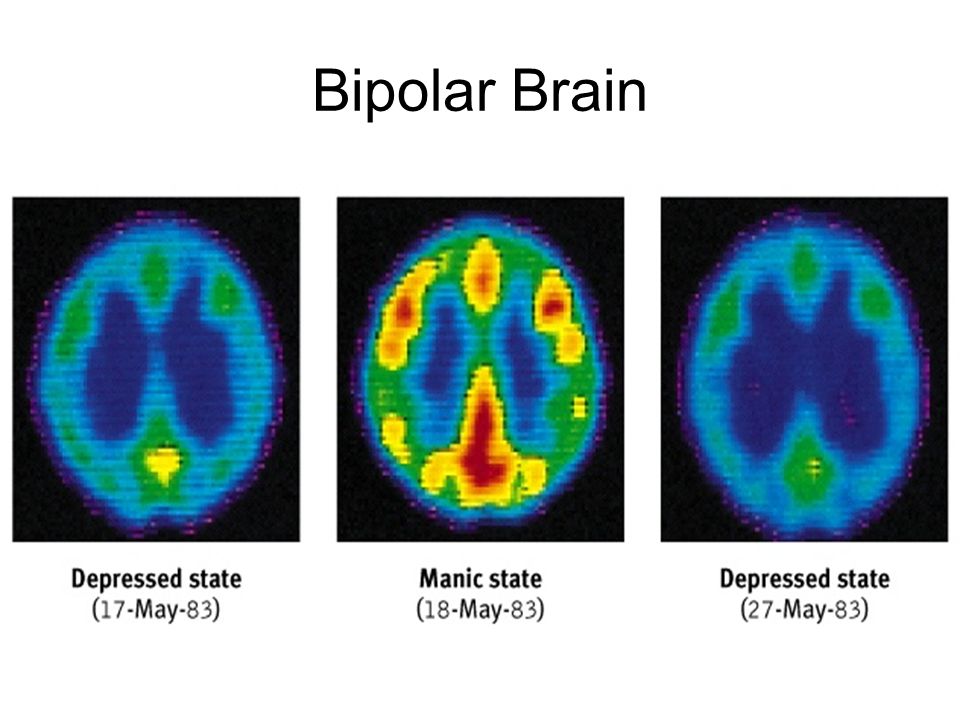

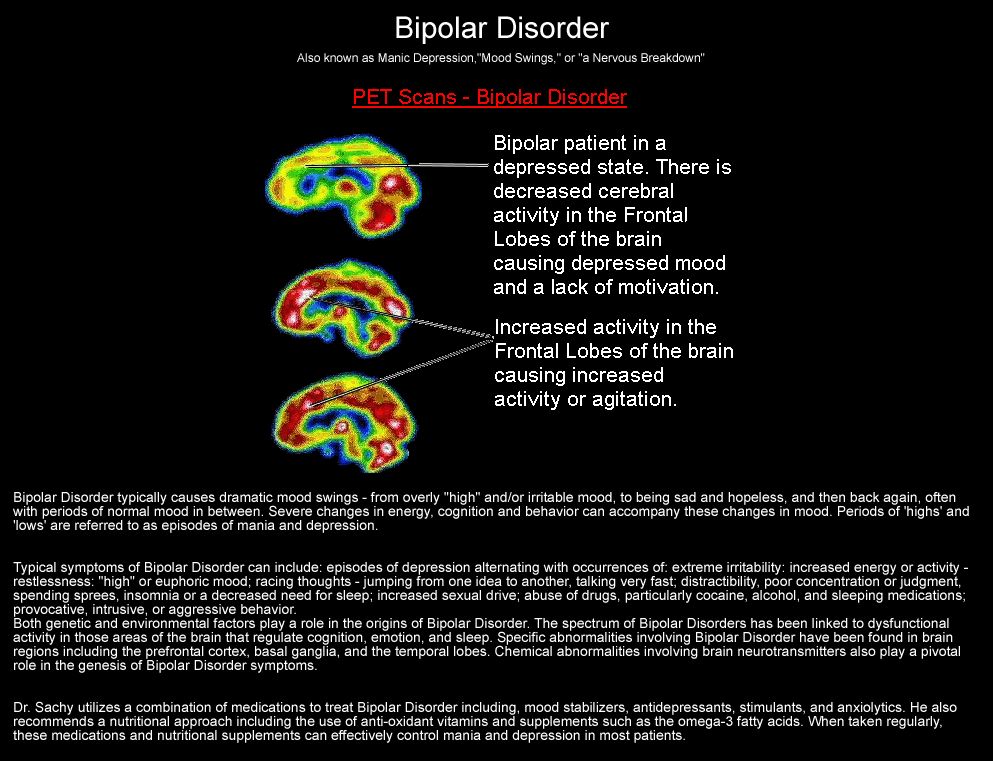

Brain Structure and Function

Research shows that the brain structure and function of people with bipolar disorder may differ from those of people who do not have bipolar disorder or other mental disorders. Learning about the nature of these brain changes helps researchers better understand bipolar disorder and, in the future, may help predict which types of treatment will work best for a person with bipolar disorder.

How is bipolar disorder diagnosed?

To diagnose bipolar disorder, a health care provider may complete a physical exam, order medical testing to rule out other illnesses, and refer the person for an evaluation by a mental health professional. Bipolar disorder is diagnosed based on the severity, length, and frequency of an individual’s symptoms and experiences over their lifetime.

Some people have bipolar disorder for years before it’s diagnosed for several reasons. People with bipolar II disorder may seek help only for depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes may go unnoticed. Misdiagnosis may happen because some bipolar disorder symptoms are like those of other illnesses. For example, people with bipolar disorder who also have psychotic symptoms can be misdiagnosed with schizophrenia. Some health conditions, such as thyroid disease, can cause symptoms like those of bipolar disorder. The effects of recreational and illicit drugs can sometimes mimic or worsen mood symptoms.

Conditions That Can Co-Occur With Bipolar Disorder

Many people with bipolar disorder also have other mental disorders or conditions such as anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), misuse of drugs or alcohol, or eating disorders. Sometimes people who have severe manic or depressive episodes also have symptoms of psychosis, such as hallucinations or delusions. The psychotic symptoms tend to match the person’s extreme mood. For example, someone having psychotic symptoms during a depressive episode may falsely believe they are financially ruined, while someone having psychotic symptoms during a manic episode may falsely believe they are famous or have special powers.

The psychotic symptoms tend to match the person’s extreme mood. For example, someone having psychotic symptoms during a depressive episode may falsely believe they are financially ruined, while someone having psychotic symptoms during a manic episode may falsely believe they are famous or have special powers.

Looking at symptoms over the course of the illness and the person’s family history can help determine whether a person has bipolar disorder along with another disorder.

How is bipolar disorder treated?

Treatment helps many people, even those with the most severe forms of bipolar disorder. Mental health professionals treat bipolar disorder with medications, psychotherapy, or a combination of treatments.

Medications

Certain medications can help control the symptoms of bipolar disorder. Some people may need to try several different medications before finding the ones that work best. The most common types of medications that doctors prescribe include mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics. Mood stabilizers such as lithium or valproate can help prevent mood episodes or reduce their severity. Lithium also can decrease the risk of suicide. While bipolar depression is often treated with antidepressant medication, a mood stabilizer must be taken as well, as an antidepressant alone can trigger a manic episode or rapid cycling in a person with bipolar disorder. Medications that target sleep or anxiety are sometimes added to mood stabilizers as part of a treatment plan.

Mood stabilizers such as lithium or valproate can help prevent mood episodes or reduce their severity. Lithium also can decrease the risk of suicide. While bipolar depression is often treated with antidepressant medication, a mood stabilizer must be taken as well, as an antidepressant alone can trigger a manic episode or rapid cycling in a person with bipolar disorder. Medications that target sleep or anxiety are sometimes added to mood stabilizers as part of a treatment plan.

Talk with your health care provider to understand the risks and benefits of each medication. Report any concerns about side effects to your health care provider right away. Avoid stopping medication without talking to your health care provider first. Read the latest medication warnings, patient medication guides, and information on newly approved medications on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy (sometimes called “talk therapy”) is a term for various treatment techniques that aim to help a person identify and change troubling emotions, thoughts, and behaviors.![]() Psychotherapy can offer support, education, skills, and strategies to people with bipolar disorder and their families.

Psychotherapy can offer support, education, skills, and strategies to people with bipolar disorder and their families.

Some types of psychotherapy can be effective treatments for bipolar disorder when used with medications, including interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, which aims to understand and work with an individual’s biological and social rhythms. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an important treatment for depression, and CBT adapted for the treatment of insomnia can be especially helpful as a component of the treatment of bipolar depression. Learn more on NIMH’s psychotherapies webpage.

Other Treatments

Some people may find other treatments helpful in managing their bipolar disorder symptoms.

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a brain stimulation procedure that can help relieve severe symptoms of bipolar disorder. ECT is usually only considered if an individual’s illness has not improved after other treatments such as medication or psychotherapy, or in cases that require rapid response, such as with suicide risk or catatonia (a state of unresponsiveness).

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) is a type of brain stimulation that uses magnetic waves, rather than the electrical stimulus of ECT, to relieve depression over a series of treatment sessions. Although not as powerful as ECT, TMS does not require general anesthesia and presents little risk of memory or adverse cognitive effects.

- Light Therapy is the best evidence-based treatment for seasonal affective disorder (SAD), and many people with bipolar disorder experience seasonal worsening of depression in the winter, in some cases to the point of SAD. Light therapy could also be considered for lesser forms of seasonal worsening of bipolar depression.

Complementary Health Approaches

Unlike specific psychotherapy and medication treatments that are scientifically proven to improve bipolar disorder symptoms, complementary health approaches for bipolar disorder, such as natural products, are not based on current knowledge or evidence. For more information, visit the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health website.

For more information, visit the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health website.

Coping With Bipolar Disorder

Living with bipolar disorder can be challenging, but there are ways to help yourself, as well as your friends and loved ones.

- Get treatment and stick with it. Treatment is the best way to start feeling better.

- Keep medical and therapy appointments and talk with your health care provider about treatment options.

- Take medication as directed.

- Structure activities. Keep a routine for eating, sleeping, and exercising.

- Try regular, vigorous exercise like jogging, swimming, or bicycling, which can help with depression and anxiety, promote better sleep, and is healthy for your heart and brain.

- Keep a life chart to help recognize your mood swings.

- Ask for help when trying to stick with your treatment.

- Be patient. Improvement takes time. Social support helps.

Remember, bipolar disorder is a lifelong illness, but long-term, ongoing treatment can help manage symptoms and enable you to live a healthy life.

Are there clinical trials studying bipolar disorder?

NIMH supports a wide range of research, including clinical trials that look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions—including bipolar disorder. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge to help others in the future. Researchers at NIMH and around the country conduct clinical trials with patients and healthy volunteers. Talk to a health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you. For more information, visit the NIMH clinical trials webpage.

Finding Help

Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

This online resource, provided by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), can help you locate mental health treatment facilities and programs. Find a facility in your state by searching SAMHSA’s online Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator. For additional resources, visit NIMH's Help for Mental Illnesses webpage.

Find a facility in your state by searching SAMHSA’s online Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator. For additional resources, visit NIMH's Help for Mental Illnesses webpage.

Talking to a Health Care Provider About Your Mental Health

If you or someone you know is in immediate distress or is thinking about hurting themselves, call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org. You can also contact the Crisis Text Line (text HELLO to 741741). For medical emergencies, call 911.

Communicating well with a health care provider can improve your care and help you both make good choices about your health. Find tips to help prepare for and get the most out of your visit. For additional resources, including questions to ask a provider, visit the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website.

Reprints

This publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission from NIMH. We encourage you to reproduce and use NIMH publications in your efforts to improve public health. If you do use our materials, we request that you cite the National Institute of Mental Health. To learn more about using NIMH publications, refer to NIMH’s reprint guidelines.

We encourage you to reproduce and use NIMH publications in your efforts to improve public health. If you do use our materials, we request that you cite the National Institute of Mental Health. To learn more about using NIMH publications, refer to NIMH’s reprint guidelines.

For More Information

MedlinePlus (National Library of Medicine) (en español)

ClinicalTrials.gov (en español)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

National Institutes of Health

NIH Publication No. 22-MH-8088

Revised 2022

NIMH » Bipolar Disorder

Overview

Bipolar disorder (formerly called manic-depressive illness or manic depression) is a mental illness that causes unusual shifts in a person’s mood, energy, activity levels, and concentration. These shifts can make it difficult to carry out day-to-day tasks.

There are three types of bipolar disorder. All three types involve clear changes in mood, energy, and activity levels. These moods range from periods of extremely “up,” elated, irritable, or energized behavior (known as manic episodes) to very “down,” sad, indifferent, or hopeless periods (known as depressive episodes). Less severe manic periods are known as hypomanic episodes.

These moods range from periods of extremely “up,” elated, irritable, or energized behavior (known as manic episodes) to very “down,” sad, indifferent, or hopeless periods (known as depressive episodes). Less severe manic periods are known as hypomanic episodes.

- Bipolar I disorder is defined by manic episodes that last for at least 7 days (nearly every day for most of the day) or by manic symptoms that are so severe that the person needs immediate medical care. Usually, depressive episodes occur as well, typically lasting at least 2 weeks. Episodes of depression with mixed features (having depressive symptoms and manic symptoms at the same time) are also possible. Experiencing four or more episodes of mania or depression within 1 year is called “rapid cycling.”

- Bipolar II disorder is defined by a pattern of depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes. The hypomanic episodes are less severe than the manic episodes in bipolar I disorder.

- Cyclothymic disorder (also called cyclothymia) is defined by recurring hypomanic and depressive symptoms that are not intense enough or do not last long enough to qualify as hypomanic or depressive episodes.

Sometimes a person might experience symptoms of bipolar disorder that do not match the three categories listed above, and this is referred to as “other specified and unspecified bipolar and related disorders.”

Bipolar disorder is often diagnosed during late adolescence (teen years) or early adulthood. Sometimes, bipolar symptoms can appear in children. Although the symptoms may vary over time, bipolar disorder usually requires lifelong treatment. Following a prescribed treatment plan can help people manage their symptoms and improve their quality of life.

Signs and symptoms

People with bipolar disorder experience periods of unusually intense emotion and changes in sleep patterns and activity levels, and engage in behaviors that are out of character for them—often without recognizing their likely harmful or undesirable effects. These distinct periods are called mood episodes. Mood episodes are very different from the person’s usual moods and behaviors. During an episode, the symptoms last every day for most of the day. Episodes may also last for longer periods, such as several days or weeks.

These distinct periods are called mood episodes. Mood episodes are very different from the person’s usual moods and behaviors. During an episode, the symptoms last every day for most of the day. Episodes may also last for longer periods, such as several days or weeks.

| Symptoms of a Manic Episode | Symptoms of a Depressive Episode |

|---|---|

| Feeling very up, high, elated, or extremely irritable or touchy | Feeling very down or sad, or anxious |

| Feeling jumpy or wired, more active than usual | Feeling slowed down or restless |

| Having a decreased need for sleep | Having trouble falling asleep, waking up too early, or sleeping too much |

| Talking fast about a lot of different things (“flight of ideas”) | Talking very slowly, feeling unable to find anything to say, or forgetting a lot |

| Racing thoughts | Having trouble concentrating or making decisions |

| Feeling able to do many things at once without getting tired | Feeling unable to do even simple things |

| Having excessive appetite for food, drinking, sex, or other pleasurable activities | Having a lack of interest in almost all activities |

| Feeling unusually important, talented, or powerful | Feeling hopeless or worthless, or thinking about death or suicide |

Sometimes people have both manic and depressive symptoms in the same episode, and this is called an episode with mixed features. During an episode with mixed features, people may feel very sad, empty, or hopeless while at the same time feeling extremely energized.

During an episode with mixed features, people may feel very sad, empty, or hopeless while at the same time feeling extremely energized.

A person may have bipolar disorder even if their symptoms are less extreme. For example, some people with bipolar II disorder experience hypomania, a less severe form of mania. During a hypomanic episode, a person may feel very good, be able to get things done, and keep up with day-to-day life. The person may not feel that anything is wrong, but family and friends may recognize changes in mood or activity levels as possible symptoms of bipolar disorder. Without proper treatment, people with hypomania can develop severe mania or depression.

Diagnosis

Receiving the right diagnosis and treatment can help people with bipolar disorder lead healthy and active lives. Talking with a health care provider is the first step. The health care provider can complete a physical exam and other necessary medical tests to rule out other possible causes. The health care provider may then conduct a mental health evaluation or provide a referral to a trained mental health care provider, such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, or clinical social worker who has experience in diagnosing and treating bipolar disorder.

The health care provider may then conduct a mental health evaluation or provide a referral to a trained mental health care provider, such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, or clinical social worker who has experience in diagnosing and treating bipolar disorder.

Mental health care providers usually diagnose bipolar disorder based on a person’s symptoms, lifetime history, experiences, and, in some cases, family history. Accurate diagnosis in youth is particularly important.

Find tips to help prepare for and get the most out of your visit with your health care provider.

Bipolar disorder and other conditions

Many people with bipolar disorder also have other mental disorders or conditions such as anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), misuse of drugs or alcohol, or eating disorders. Sometimes people who have severe manic or depressive episodes also have symptoms of psychosis, which may include hallucinations or delusions. The psychotic symptoms tend to match the person’s extreme mood. For example, someone having psychotic symptoms during a depressive episode may falsely believe they are financially ruined, while someone having psychotic symptoms during a manic episode may falsely believe they are famous or have special powers.

For example, someone having psychotic symptoms during a depressive episode may falsely believe they are financially ruined, while someone having psychotic symptoms during a manic episode may falsely believe they are famous or have special powers.

Looking at a person’s symptoms over the course of the illness and examining their family history can help a health care provider determine whether the person has bipolar disorder along with another disorder.

Risk factors

Researchers are studying possible causes of bipolar disorder. Most agree that there are many factors that are likely to contribute to a person’s chance of having the disorder.

Brain structure and functioning: Some studies show that the brains of people with bipolar disorder differ in certain ways from the brains of people who do not have bipolar disorder or any other mental disorder. Learning more about these brain differences may help scientists understand bipolar disorder and determine which treatments will work best. At this time, health care providers base the diagnosis and treatment plan on a person’s symptoms and history, rather than brain imaging or other diagnostic tests.

At this time, health care providers base the diagnosis and treatment plan on a person’s symptoms and history, rather than brain imaging or other diagnostic tests.

Genetics: Some research suggests that people with certain genes are more likely to develop bipolar disorder. Research also shows that people who have a parent or sibling with bipolar disorder have an increased chance of having the disorder themselves. Many genes are involved, and no one gene causes the disorder. Learning more about how genes play a role in bipolar disorder may help researchers develop new treatments.

Treatments and therapies

Treatment can help many people, including those with the most severe forms of bipolar disorder. An effective treatment plan usually includes a combination of medication and psychotherapy, also called talk therapy.

Bipolar disorder is a lifelong illness. Episodes of mania and depression typically come back over time. Between episodes, many people with bipolar disorder are free of mood changes, but some people may have lingering symptoms. Long-term, continuous treatment can help people manage these symptoms.

Long-term, continuous treatment can help people manage these symptoms.

Medications

Certain medications can help manage symptoms of bipolar disorder. Some people may need to try different medications and work with their health care provider to find the medications that work best.

The most common types of medications that health care providers prescribe include mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics. Mood stabilizers such as lithium or valproate can help prevent mood episodes or reduce their severity. Lithium also can decrease the risk of suicide. Health care providers may include medications that target sleep or anxiety as part of the treatment plan.

Although bipolar depression is often treated with antidepressant medication, a mood stabilizer must be taken as well—taking an antidepressant without a mood stabilizer can trigger a manic episode or rapid cycling in a person with bipolar disorder.

Because people with bipolar disorder are more likely to seek help when they are depressed than when they are experiencing mania or hypomania, it is important for health care providers to take a careful medical history to ensure that bipolar disorder is not mistaken for depression.

People taking medication should:

- Talk with their health care provider to understand the risks and benefits of the medication.

- Tell their health care provider about any prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications, or supplements they are already taking.

- Report any concerns about side effects to a health care provider right away. The health care provider may need to change the dose or try a different medication.

- Remember that medication for bipolar disorder must be taken consistently, as prescribed, even when one is feeling well.

It is important to talk to a health care provider before stopping a prescribed medication. Stopping a medication suddenly may lead symptoms to worsen or come back. You can find basic information about medications on NIMH's medications webpage. Read the latest medication warnings, patient medication guides, and information on newly approved medications on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy, also called talk therapy, can be an effective part of treatment for people with bipolar disorder. Psychotherapy is a term for treatment techniques that aim to help people identify and change troubling emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. This type of therapy can provide support, education, and guidance to people with bipolar disorder and their families.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an important treatment for depression, and CBT adapted for the treatment of insomnia can be especially helpful as part of treatment for bipolar depression.

Treatment may also include newer therapies designed specifically for the treatment of bipolar disorder, including interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT) and family-focused therapy.

Learn more about the various types of psychotherapies.

Other treatment options

Some people may find other treatments helpful in managing their bipolar symptoms:

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a brain stimulation procedure that can help relieve severe symptoms of bipolar disorder.

Health care providers may consider ECT when a person’s illness has not improved after other treatments, or in cases that require rapid response, such as with people who have a high suicide risk or catatonia (a state of unresponsiveness).

Health care providers may consider ECT when a person’s illness has not improved after other treatments, or in cases that require rapid response, such as with people who have a high suicide risk or catatonia (a state of unresponsiveness). - Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a type of brain stimulation that uses magnetic waves to relieve depression over a series of treatment sessions. Although not as powerful as ECT, rTMS does not require general anesthesia and has a low risk of negative effects on memory and thinking.

- Light therapy is the best evidence-based treatment for seasonal affective disorder (SAD), and many people with bipolar disorder experience seasonal worsening of depression or SAD in the winter. Light therapy may also be used to treat lesser forms of seasonal worsening of bipolar depression.

Unlike specific psychotherapy and medication treatments that are scientifically proven to improve bipolar disorder symptoms, complementary health approaches for bipolar disorder, such as natural products, are not based on current knowledge or evidence. For more information, visit the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health website.

For more information, visit the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health website.

Finding treatment

- A family health care provider is a good resource and can be the first stop in searching for help. Find tips to help prepare for and get the most out of your visit.

- To find mental health treatment services in your area, call the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357), visit the SAMHSA online treatment locator, or text your ZIP code to 435748.

- Learn more about finding help on the NIMH website.

If you or someone you know is struggling or having thoughts of suicide, call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org. In life-threatening situations, call 911.

Coping with bipolar disorder

Living with bipolar disorder can be challenging, but there are ways to help make it easier.

- Work with a health care provider to develop a treatment plan and stick with it.

Treatment is the best way to start feeling better.

Treatment is the best way to start feeling better. - Follow the treatment plan as directed. Work with a health care provider to adjust the plan, as needed.

- Structure your activities. Try to have a routine for eating, sleeping, and exercising.

- Try regular, vigorous exercise like jogging, swimming, or bicycling, which can help with depression and anxiety, promote better sleep, and support your heart and brain health.

- Track your moods, activities, and overall health and well-being to help recognize your mood swings.

- Ask trusted friends and family members for help in keeping up with your treatment plan.

- Be patient. Improvement takes time. Staying connected with sources of social support can help.

Long-term, ongoing treatment can help control symptoms and enable you to live a healthy life.

Join a study

Clinical trials are research studies that look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions. The goal of clinical trials is to determine if a new test or treatment works and is safe. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge so that others may be better helped in the future.

The goal of clinical trials is to determine if a new test or treatment works and is safe. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge so that others may be better helped in the future.

Researchers at NIMH and around the country conduct many studies with patients and healthy volunteers. We have new and better treatment options today because of what clinical trials uncovered years ago. Be part of tomorrow’s medical breakthroughs. Talk to your health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you.

To learn more or find a study, visit:

- NIMH’s Clinical Trials webpage: Information about participating in clinical trials

- Clinicaltrials.gov: Current Studies on Bipolar Disorder: List of clinical trials funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) being conducted across the country

- Join a Study: Bipolar Disorder – Adults: List of studies being conducted on the NIH Campus in Bethesda, MD

Learn More

Free Brochures and Shareable Resources

- Bipolar Disorder: A brochure on bipolar disorder that offers basic information on signs and symptoms, treatment, and finding help.

Also available en español.

Also available en español. - Bipolar Disorder in Children and Teens: A brochure on bipolar disorder in children and teens that offers basic information on signs and symptoms, treatment, and finding help. Also available en español.

- Bipolar Disorder in Teens and Young Adults: Know the Signs: An infographic presenting common signs and symptoms of bipolar disorder in teens and young adults. Also available en español.

- Shareable Resources on Bipolar Disorder: Digital resources, including graphics and messages, to help support bipolar disorder awareness and education.

Multimedia

- Mental Health Minute: Bipolar Disorder in Adults: A minute-long video to learn about bipolar disorder in adults.

- NIMH Expert Discusses Bipolar Disorder in Adolescents and Young Adults: A video with an expert who explains the signs, symptoms, and treatments of bipolar disorder.

Research and Statistics

- Journal Articles: This webpage provides information on references and abstracts from MEDLINE/PubMed (National Library of Medicine).

- Treatment for Bipolar Disorder in Adults: A Systematic Review: A review from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality that assesses the effectiveness of medications and other therapies for treating mania or depression symptoms and preventing relapse in adults with bipolar disorder.

- Bipolar Disorder Statistics: An NIMH webpage that provides information on the prevalence of bipolar disorder among adults and adolescents.

Last Reviewed: February 2023

Unless otherwise specified, NIMH information and publications are in the public domain and available for use free of charge. Citation of NIMH is appreciated. Please see our Citing NIMH Information and Publications page for more information.

Types of depression - iFightDepression [EN]

There are different types of depression, which are different.

Signs and symptoms vary in number, time, severity and frequency, but are generally very similar. Because different types of depression are treated differently, it is important to pinpoint the type of depression. Depending on gender, age and cultural characteristics, people have different symptoms and severity of depression.

Neurotic, reactive (minor) depression is treated with psychotherapy.

Somatic and psychotic - medication. These terms are used by psychiatrists.

Studies have shown that depression has a phasic course. Periods of normal mood alternate with depressive episodes. Sometimes, instead of a depressive phase,

there may be a manic phase, which is manifested by irritability and high mood. If so, then it is not depression, but bipolar disorder (a more serious illness).

1. Depressive episode

The most common and typical form of depression is the depressive episode. An episode lasts from a few weeks to a year, but is always longer than 2 weeks. A single depressive episode is called a unipolar episode. Approximately one third of affected people experience only one episode, or "phase", during their lifetime. However, if a person does not receive appropriate treatment for depression, there is a risk of recurrent depressive episodes in the future. Depressive episodes always affect a person's performance to one degree or another.

An episode lasts from a few weeks to a year, but is always longer than 2 weeks. A single depressive episode is called a unipolar episode. Approximately one third of affected people experience only one episode, or "phase", during their lifetime. However, if a person does not receive appropriate treatment for depression, there is a risk of recurrent depressive episodes in the future. Depressive episodes always affect a person's performance to one degree or another.

2. Intermittent (recurrent) depressive disorder

When a depressive episode recurs, it is recurrent depressive disorder or major depressive disorder, which usually begins in adolescence or early adulthood. With this kind of depression, depressive phases, which can last from several months to several years, alternate with phases of normal mood. This type of depressive disorder can seriously affect performance and is unipolar in nature (no manic or hypomanic phase). This is the so-called "classic" or "clinical" depression.

3. Dysthymia

Dysthymia presents with milder and less severe symptoms than a depressive episode or recurrent depression. However, the disorder is permanent, with symptoms lasting much longer, at least 2 years, sometimes decades, which is why it is called "chronic depression". This disorder is unipolar and also affects performance. This type of depression sometimes develops into a more severe form (major depressive episode) and if this happens it is called double depression.

4. Bipolar depression, type I

This is the type of depression in bipolar disorder, formerly called manic-depressive illness, and is less common than unipolar depression. It consists of alternating depressive phases, phases of normal mood and so-called manic phases.

Manic phases are characterized by excessively high mood associated with hyperactivity, anxiety, and decreased need for sleep.

Mania affects thinking, judgment and social behavior causing serious problems and difficulties. When a person is in a manic phase, he makes frequent casual unsafe sex, makes unwise financial decisions. After a manic episode, such people often experience depression.

When a person is in a manic phase, he makes frequent casual unsafe sex, makes unwise financial decisions. After a manic episode, such people often experience depression.

The best way to describe these "emotional upheavals" is "to be on top of the world and fall into the depths of despair".

Symptoms of the phases of depression in bipolar disorder are sometimes difficult to distinguish from unipolar depression.

5. Bipolar depression type II

More like recurrent depressive disorder than bipolar disorder. In this disorder, multiple depressive phases alternate with phases of mania, but with less pronounced euphoria. During these phases, family and loved ones may even mistakenly assume that the person is doing well.

6. Mixed anxiety-depressive disorder

In anxiety-depressive disorder, the clinical picture is very similar to depression, however, in depression, depressive syndromes always come first. In this case, both anxious and depressive symptoms are evenly combined.

7. Depressive psychotic episode

A special form of depressive episode is psychotic or delusional depression. Psychosis is a condition in which people see or hear things that do not exist (hallucinations) and/or have false ideas or beliefs (delusions). There are various types of delusions such as self-accusation for no reason (delusion of guilt), financial ruin (delusions of poverty), feeling of an incomprehensible illness (hypochondriac delusions). People with delusional depression almost always require inpatient psychiatric treatment. Psychotic episodes can be either unipolar or bipolar.

8. Atypical depression

This type of depression is characterized by hypersensitivity and mood swings, overeating and drowsiness, panic attacks. This type of depression is mild and can be bipolar.

9. Seasonal depressive disorder

This type of depression is similar to atypical depression and comes on seasonally with climate change, usually in autumn or winter. Usually, when the season ends, people return to normal functioning again.

Usually, when the season ends, people return to normal functioning again.

10. Brief depressive disorder

This is a milder variant of depression that more often affects young people and is characterized by short depressive episodes lasting less than 2 weeks.

gender characteristics of the course and therapy

For the first time about circular psychosis, or "insanity in two forms", two French psychiatrists J. Falret and J. Baillarger reported in the middle of the 19th century. E. Kraepelin in 1896 proposed to combine a group of affective psychoses with polar clinical manifestations (depressive and manic) into a single manic-depressive psychosis based on the phase course of the disease with alternating exacerbations and remissions and a favorable prognosis, in contrast to dementia praecox. At the same time, he pointed out the difficulty of drawing clear boundaries between these polar affective disorders, since they can quickly replace each other and mix. For example, one may encounter depression with agitation or mania with lethargy [1]. Later, E. Bleuler noted that “the more it is possible to trace the patient's life, the less often it is possible to make the correct series of one homogeneous attacks” [2]. This was confirmed in later studies, which showed that during the life of the patient the polarity of attacks, their frequency, duration and severity may change. Approximately 40% of patients who were initially diagnosed with recurrent depression were subsequently diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder (BAD). In other words, a "drift" from a pseudo-monopolar flow to a BAR is possible [3].

For example, one may encounter depression with agitation or mania with lethargy [1]. Later, E. Bleuler noted that “the more it is possible to trace the patient's life, the less often it is possible to make the correct series of one homogeneous attacks” [2]. This was confirmed in later studies, which showed that during the life of the patient the polarity of attacks, their frequency, duration and severity may change. Approximately 40% of patients who were initially diagnosed with recurrent depression were subsequently diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder (BAD). In other words, a "drift" from a pseudo-monopolar flow to a BAR is possible [3].

In 1957, K. Leonhard [4] proposed the division of affective psychoses into monopolar and bipolar ones, which was confirmed in a number of subsequent studies [5, 6].

In 1976, the American psychiatrist D. Dunner proposed to divide bipolar disorder into two types, depending on the manifestations of manic syndrome [7]. In DSM-5, in addition to BAD type I, which occurs with mania, and BAD type II, which occurs with hypomania, which, as a rule, does not require hospitalization [8], cyclothymia is distinguished, which is considered by a number of authors as BAD type III. The position of the latter remained controversial for a long time. E. Kraepelin considered it as a "cyclothymic temperament" - a predictor of manic-depressive psychosis [6]. Yu.V. Kannabich considered cyclothymia to be a non-psychotic form of phasic diseases, and P.B. Gannushkin attributed cyclothymia to a number of psychopathy [9]. A subsequent study showed that in 1/3 of the personalities of the cyclothymic circle, affective symptoms worsen over time - the appearance of more pronounced hypomania, accompanied by the abuse of psychoactive substances and alcohol, violations of the law, and more severe and prolonged depressions [10, 11]. J. Klerman (1987) included cyclothymia in the bipolar spectrum of disorders, and also proposed his own variants of the bipolar disorder classification, including 6 types of the course of the disease. The classification has been expanded to include antidepressant-induced manias; unipolar, or recurrent, mania without depression; depressions associated with hyperthymic temperament; recurrent depression in patients whose relatives suffer from bipolar disorder; late depression with mixed features progressing to a syndrome similar to dementia.

The position of the latter remained controversial for a long time. E. Kraepelin considered it as a "cyclothymic temperament" - a predictor of manic-depressive psychosis [6]. Yu.V. Kannabich considered cyclothymia to be a non-psychotic form of phasic diseases, and P.B. Gannushkin attributed cyclothymia to a number of psychopathy [9]. A subsequent study showed that in 1/3 of the personalities of the cyclothymic circle, affective symptoms worsen over time - the appearance of more pronounced hypomania, accompanied by the abuse of psychoactive substances and alcohol, violations of the law, and more severe and prolonged depressions [10, 11]. J. Klerman (1987) included cyclothymia in the bipolar spectrum of disorders, and also proposed his own variants of the bipolar disorder classification, including 6 types of the course of the disease. The classification has been expanded to include antidepressant-induced manias; unipolar, or recurrent, mania without depression; depressions associated with hyperthymic temperament; recurrent depression in patients whose relatives suffer from bipolar disorder; late depression with mixed features progressing to a syndrome similar to dementia. The latter are more often diagnosed in the elderly due to the burden of somatic and neurological diseases [12].

The latter are more often diagnosed in the elderly due to the burden of somatic and neurological diseases [12].

The ICD-10 does not distinguish between individual types of bipolar disorder, using a predominantly syndromic approach to diagnosis, which allows the most accurate characterization of the patient's status and the stage of his disease at the present time, taking into account the severity and accompanying symptoms [13].

Difficulties in diagnosing BAD

If at present the definition of BAD as an independent nosology has been resolved, then the issues of differential diagnosis of recurrent affective disorder (RDD) and BAD, as well as the establishment of differences in the depressive syndrome within these disorders, constitute a certain diagnostic difficulty and many studies are devoted to them [14].

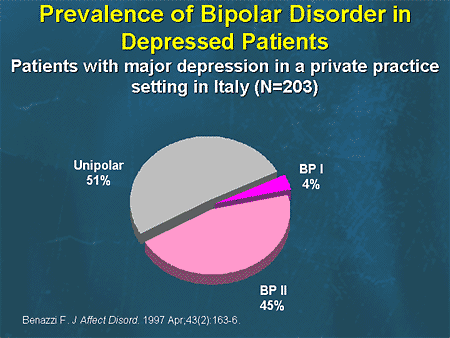

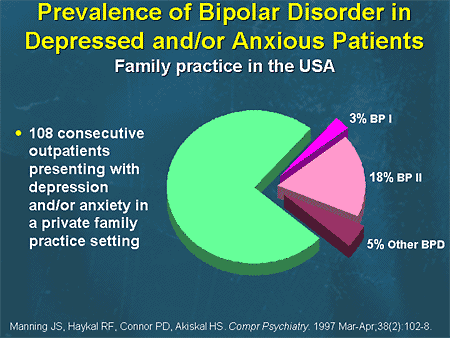

The key differential criterion for the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, as mentioned above, is the presence of hypomanic or manic phases in the anamnesis of the disease. However, the frequent misdiagnosis of recurrent depressive disorder in patients with bipolar disorder is due to the fact that patients do not assess the hypomanic or manic state as painful, therefore they do not go to the doctor and do not report the past "mood lift" when collecting anamnestic information. In the French study EPIDEP [15], using a specially designed questionnaire to objectify the history data obtained from patients, the prevalence of bipolar disorder among depressed patients increased almost 2-fold, from 22 to 40%.

However, the frequent misdiagnosis of recurrent depressive disorder in patients with bipolar disorder is due to the fact that patients do not assess the hypomanic or manic state as painful, therefore they do not go to the doctor and do not report the past "mood lift" when collecting anamnestic information. In the French study EPIDEP [15], using a specially designed questionnaire to objectify the history data obtained from patients, the prevalence of bipolar disorder among depressed patients increased almost 2-fold, from 22 to 40%.

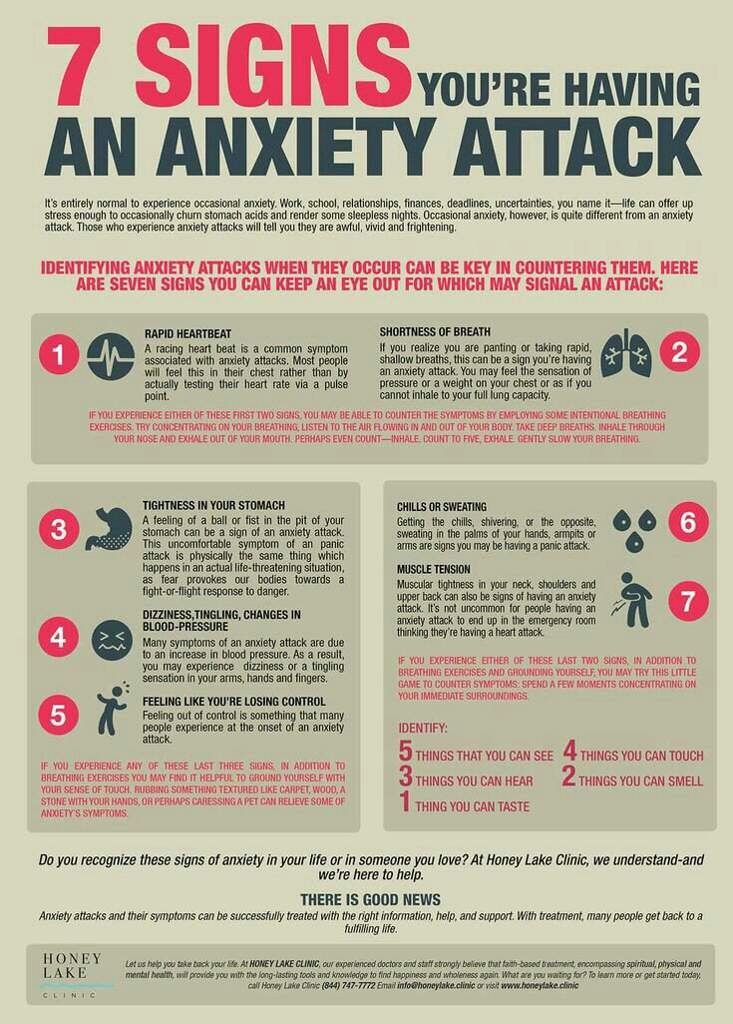

Factors complicating the process of diagnosis include frequent comorbidity of bipolar disorder with other disorders, especially with anxiety and addictive disorders [16, 17], as well as delayed onset of manic or hypomanic symptoms in patients with recurrent depressive phases [18].

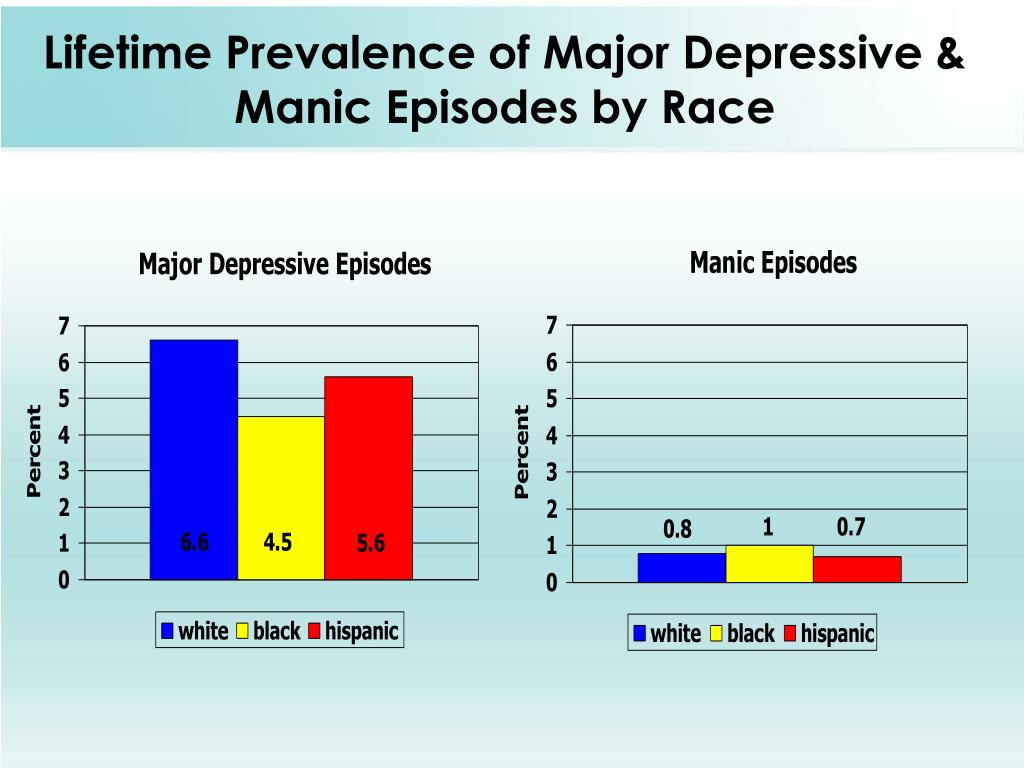

Epidemiology and medical and social significance of bipolar disorder

Due to the difficulty of correctly and timely diagnosing bipolar disorder, information on the prevalence of this disorder in the population varies widely. Incidence rates in the general population range from 1.5-6.5%. The ratio of incidence among men and women is 1:1. At the same time, there is evidence of a higher incidence of women with BAD type II [19]. According to the results of a number of studies, the frequency of BAD I is from 0.4 to 1.6%, and BAD II is from 0.5 to 1.9% [20]. In Russia, there is no separate record of cases of BAD I and BAD II due to the absence of separate codes for them in the ICD-10 [19].

Incidence rates in the general population range from 1.5-6.5%. The ratio of incidence among men and women is 1:1. At the same time, there is evidence of a higher incidence of women with BAD type II [19]. According to the results of a number of studies, the frequency of BAD I is from 0.4 to 1.6%, and BAD II is from 0.5 to 1.9% [20]. In Russia, there is no separate record of cases of BAD I and BAD II due to the absence of separate codes for them in the ICD-10 [19].

Despite the fact that the specific contribution of bipolar disorder to the total number of depressive states is not so large, the disorder itself is associated with a high risk of social maladaptation. R. Joffe et al. [21] showed that 50% of the time per year, patients with bipolar disorder are in a euthymic state, 41% are in a state of depression, and only 9% - in a state of mania. However, the quality of their life, social and family functioning, the possibility of self-realization are violated even in the euthymic period, which a number of authors [16, 22] associate with “strange”, defiant and impulsive behavior both during affective upsurges and in the period between attacks. Among patients with bipolar disorder, the unemployment rate is 2 times higher than in the general population. Also, the frequency of divorces in families in which the husband or wife suffers from bipolar disorder is 3 times higher than in the control group of mentally healthy people.

Among patients with bipolar disorder, the unemployment rate is 2 times higher than in the general population. Also, the frequency of divorces in families in which the husband or wife suffers from bipolar disorder is 3 times higher than in the control group of mentally healthy people.

The risk of developing alcoholism in bipolar disorder is 6-7 times higher than in the general population [17], while in men it is 3 times higher, and in women it is 7 times higher [23]. The views of individual researchers on the relationship between BAD and alcoholism are different: some believe that BAD can be a risk factor for the formation of dependence on psychoactive substances (alcohol and drugs), others allow the provoking effect of the latter on the development of affective disorders, and others believe that there are common links in the pathogenesis these diseases.

A decrease in the quality of life of patients with bipolar disorder is associated not only with a mental health problem, but also with concomitant somatic diseases, such as overweight and obesity, hyperlipidemia, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, pathology of the osteoarticular system, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [24] . These data can presumably be explained by a decrease in adherence to treatment due to a decrease in motivation in such patients [25], especially considering that patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder are much more likely to have comorbid addictive disorders [26].

These data can presumably be explained by a decrease in adherence to treatment due to a decrease in motivation in such patients [25], especially considering that patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder are much more likely to have comorbid addictive disorders [26].

BAD is also associated with a high suicidal risk - more than ¼ of patients make a suicide attempt during their lifetime [27]. According to the WHO (2001), BAD ranks 6th among the causes of disability [28]. A number of studies have found that, on average, patients with bipolar disorder lose about 9 years of life expectancy, 14 years of working capacity, and 12 years of normal health [29–31].

BAR course and forecast

BAD is a disease with a complex psychopathological structure, in which there are affective phases of different polarity and severity. The intermission following the completion of the phase is characterized by an euthymic mood and the formation of criticality towards the painful episode. In some cases, the hypomanic state is assessed by patients not as painful, but, on the contrary, as a period of increased efficiency and productivity. Depending on the combination of phases and the presence of intermissions between them, several types of BAR flow are distinguished.

In some cases, the hypomanic state is assessed by patients not as painful, but, on the contrary, as a period of increased efficiency and productivity. Depending on the combination of phases and the presence of intermissions between them, several types of BAR flow are distinguished.

The relapsing "classic" type of flow, described by E. Kraepelin, is characterized by phase alternation with euthymic intervals between them. At the same time, the duration of interictal intervals shortens with age, and residual affective symptoms often persist in the interictal period [32, 33]. Intermission after the first affective attack is usually the longest and averages 4.5 years, subsequently reduced to 1 year [34].

Dual phases of different polarity with the subsequent onset of intermission constitute an alternating type of flow. As with the relapsing course, there is a tendency to lengthen the phases and shorten the euthymic intervals up to the transition to a continual course, characterized by the absence of remissions between episodes.

A special type of continual flow is the fast cyclic type. In accordance with the DSM-IV criteria, it is determined by the development of at least four affective phases within 1 year, which can be separated by short-term remissions up to 2 months. Each depressive episode should last at least 2 weeks, each manic or mixed episode should last at least 1 week, and each hypomanic episode should last at least 4 days [35]. This type of course is more common in women with type II bipolar disorder who suffer from hypothyroidism and are constantly taking antidepressants. Such patients have an early onset of the disease and a more severe course of depressive phases associated with a high suicidal risk [36, 37]. The fast cyclic flow tends to transition to ultrafast forms with phase change over the course of a month or even a day and are actually represented by mixed states [38].

Mixed states are longer compared to manic and depressive phases, characterized by a more severe course, resistance to therapy, and unexpected suicidal attempts [39].

The disease has very pronounced gender characteristics. In men, bipolar disorder begins earlier than in women [40], while the first phase is more often manic in men, and depressive in women [41, 42]. During the course of the disease, this dependence persists: the proportion of manic episodes in men is greater than in women. In women, the manifestation of the disease is often associated with menstrual-generative function and periods of hormonal changes (pubertal, postpartum, menopausal) [43]. In 20–30% of women with bipolar disorder, within 1 month after delivery, another attack of the disease develops, more often depressive [44, 45]. A postpartum episode of bipolar disorder (mania or depression in general) occurs in 40–67% of cases [46]. Although manic (hypomanic) phases are a key phenomenon in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, patients spend most of their time depressed [47, 48]. This may be related to the fact that BAD type II is diagnosed more often in women, and BAD type I is equally common in women and men [49]. Consequently, the longer clinically expressed mania does not fall into the field of vision of a psychiatrist, the longer patients (more often women) will receive inadequate treatment.

Consequently, the longer clinically expressed mania does not fall into the field of vision of a psychiatrist, the longer patients (more often women) will receive inadequate treatment.

Features of depressive syndrome in bipolar disorder

Determining the nosological status of depression, i.e., within the framework of which disease an affective disorder arose, is still a debatable issue in psychiatry. This is due to the fact that until now the etiology of depression is not completely clear. A depressive state is considered as multifactorial, i.e. dependent on biological, psychological and social causes.

Despite the development of biological research (neurochemistry, genetics, neuroendocrinology), most specialists, when diagnosing RDR or BAD and prescribing therapy in practice, still focus on the clinical features of depressive states and the course of the disease.

Bipolar spectrum disorders are characterized by an earlier age of onset (19. 5 ± 0.7 years) compared to RDR (37.9 ± 1.6 years), a higher frequency of exacerbations, with a shorter duration of episodes, deterioration in the autumn winter time versus classic spring-autumn exacerbations in RDR, more pronounced diurnal fluctuations with deterioration in the morning hours. Hyperthymic premorbid predominates in the group of patients with bipolar disorder, while anxiety premorbid predominates in patients with RDR, and affective disorders, schizophrenia, and alcoholism are less common in immediate relatives than in patients with phase change [50]. A weak response to antidepressant monotherapy may also be indicative of a bipolar course [51].

5 ± 0.7 years) compared to RDR (37.9 ± 1.6 years), a higher frequency of exacerbations, with a shorter duration of episodes, deterioration in the autumn winter time versus classic spring-autumn exacerbations in RDR, more pronounced diurnal fluctuations with deterioration in the morning hours. Hyperthymic premorbid predominates in the group of patients with bipolar disorder, while anxiety premorbid predominates in patients with RDR, and affective disorders, schizophrenia, and alcoholism are less common in immediate relatives than in patients with phase change [50]. A weak response to antidepressant monotherapy may also be indicative of a bipolar course [51].

Despite the importance of identifying hypomania or mania for inclusion in section F31 "Bipolar affective disorder" of the ICD-10 [13], depressive episodes are of much greater clinical and socioeconomic importance in the structure of the disease.

There are significant differences in the ratio of the total duration of depressive and manic phases and between different types of bipolar disorder. One study by the US National Institute of Mental Health [43] found that patients with BAD type I and BAD type II spend a total of 30% and 52% of the observation time in the depressive phase, respectively.

One study by the US National Institute of Mental Health [43] found that patients with BAD type I and BAD type II spend a total of 30% and 52% of the observation time in the depressive phase, respectively.

Along with the differences in the duration of the depressive phase, according to many domestic and foreign authors, there are also clinical features of depression in BAD type I and BAD type II. In patients with type II bipolar disorder, anxiety affect predominates, while in patients with type I bipolar disorder, complaints of apathy are more common. Despite a higher level of psychomotor retardation, the risk of suicidal activity is significantly higher in the type I bipolar group. Patients with BAD type II are more likely to have somatic complaints and the development of panic attacks [10].

Depression in the structure of bipolar disorder does not always meet the criteria for a typical depressive episode (F32) according to ICD-10. In recent decades, special attention has been paid to the study of atypical depressions, the symptoms of which do not fit into the classical triad. With psychopathological differentiation of the disorders dominant in the clinical picture, A.S. Avedisova and M.P. Marachev [52] identified three variants of atypical depression with a predominance of 1) mood reactivity, 2) inversion of autonomic symptoms (hyperphagia, hypersomnia, "lead paralysis"), 3) sensitivity to rejection. According to these authors, in patients with bipolar disorder more often (33.3%) than in patients with RDR (5.5%), atypical depression occurs with a predominance of inverted autonomic symptoms. The psychopathological picture of this variant suggests the presence of hypersomnia (up to 16 hours/day, including daytime sleep), hyperphagia with an increase in body weight and sensations of heaviness in the limbs ("lead paralysis").

With psychopathological differentiation of the disorders dominant in the clinical picture, A.S. Avedisova and M.P. Marachev [52] identified three variants of atypical depression with a predominance of 1) mood reactivity, 2) inversion of autonomic symptoms (hyperphagia, hypersomnia, "lead paralysis"), 3) sensitivity to rejection. According to these authors, in patients with bipolar disorder more often (33.3%) than in patients with RDR (5.5%), atypical depression occurs with a predominance of inverted autonomic symptoms. The psychopathological picture of this variant suggests the presence of hypersomnia (up to 16 hours/day, including daytime sleep), hyperphagia with an increase in body weight and sensations of heaviness in the limbs ("lead paralysis").

Patients with bipolar disorder are characterized by comorbid somatic, mental disorders and addiction diseases. Moreover, certain differences were found in women and men. In a large-scale retrospective study conducted in 45 US states from 2010 to 2014 [53], it was found that the most common comorbid somatic diseases in patients with bipolar disorder were hypertension (20. 5%), asthma (12.5%) and hypothyroidism. (8.1%). At the same time, they were 3 times more common in women. Also, women with bipolar disorder had a higher risk of developing cardiometabolic disorders (obesity, diabetes mellitus).

5%), asthma (12.5%) and hypothyroidism. (8.1%). At the same time, they were 3 times more common in women. Also, women with bipolar disorder had a higher risk of developing cardiometabolic disorders (obesity, diabetes mellitus).

Of the comorbid psychiatric disorders, men diagnosed with bipolar disorder are more prone to addiction disorders, while anxiety and personality disorders are more common in women. There is a clear relationship between anxiety symptoms and depression in bipolar disorder [54, 55].

The rarest comorbid mental disorder in patients with bipolar disorder is eating disorder (0.1% of men and 0.6% of women), but women are 11 times more likely to develop it [53].

Domestic and foreign authors agree that gender features exist not only within disorders in general, but are also determined when considering individual syndromes.

It has been found that depressive syndrome in women is more characteristic of diurnal mood swings, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, fatigue and lack of sleep, increased appetite and weight gain; in men, sad affect, motor retardation, somatic symptoms, concomitant diseases of the cardiovascular, respiratory and genitourinary systems, alcohol and psychoactive substance abuse are more often detected [51, 56]. Some researchers single out the concept of "male depressive syndrome", which is characterized by sudden and recurrent bouts of anger, irritability, aggression, which can be explained by the reluctance to share experiences and seek help [57].

Some researchers single out the concept of "male depressive syndrome", which is characterized by sudden and recurrent bouts of anger, irritability, aggression, which can be explained by the reluctance to share experiences and seek help [57].

There are a number of gender differences in depression in terms of socio-psychological functioning. In women, depression often leads to a pronounced decrease in volitional self-regulation, which is expressed in a decrease in performance at work, an untidy appearance, and problems in the sexual sphere [58].

It should be noted that the results obtained reflect the gender characteristics of predominantly unipolar depression, but do not give an idea of the features of the depressive syndrome within the framework of bipolar disorder, which may be important for prognosis and treatment.

Treatment of depression in bipolar disorder

The presence of two polar phases in the structure of one disease is important for determining the tactics of treating patients with bipolar disorder. Approaches to the treatment of bipolar depression differ significantly from the treatment of depressive syndrome in other diseases. If in the case of recurrent depression the need for the use of antidepressants is not in doubt, then the use of antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder is one of the most discussed issues.

Approaches to the treatment of bipolar depression differ significantly from the treatment of depressive syndrome in other diseases. If in the case of recurrent depression the need for the use of antidepressants is not in doubt, then the use of antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder is one of the most discussed issues.

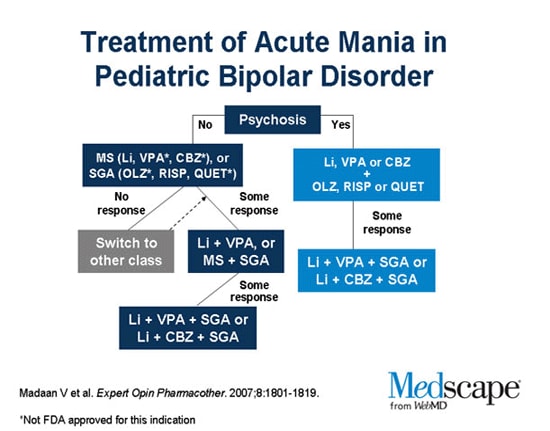

There are several typical approaches to the treatment of bipolar depression. Thus, experts of the American Psychiatric Association consider lithium and lamotrigine to be the first-line drugs for the treatment of non-psychotic bipolar depression. Additional prescription of antidepressants is recommended only for very severe depression [59, 60]. The recommendations of the British Association of Psychopharmacologists state the need for a combination of drugs from the group of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and antimanic drugs (lithium, valproates, atypical antipsychotics) for depression of any severity from the very beginning of therapy [61]. The Canadian guidelines for the treatment of bipolar depression in BAD type I follow similar approaches. Quetiapine is considered the first-line treatment for depression in type II bipolar disorder and has been shown to be effective in many studies. If it is ineffective, combined therapy with mood stabilizers and antidepressants is recommended [62, 63].

The Canadian guidelines for the treatment of bipolar depression in BAD type I follow similar approaches. Quetiapine is considered the first-line treatment for depression in type II bipolar disorder and has been shown to be effective in many studies. If it is ineffective, combined therapy with mood stabilizers and antidepressants is recommended [62, 63].

Most researchers agree that the appointment of antidepressants "bipolar" patients significantly increases the risk of phase inversion and the development of unfavorable forms of the course of BAD (continuous, fast-cyclic). According to some authors, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) provoke phase inversion in bipolar disorder in more than 30% of cases [64]. The frequency of inversion is directly proportional to the dosages of antidepressants used.

Modern studies have shown that the inclusion of an antidepressant in the regimen of relief therapy accelerates the process of recovery from an attack and significantly increases the effectiveness of treatment without provoking the development of an inversion of the depressive phase in patients with bipolar disorder [65].

One of the first studies was conducted to study the effectiveness of paroxetine in the treatment of bipolar depression. The frequency of antidepressant-induced manias was 2–3%, which is several tens of times less than with TCAs [66].

Factors associated with a high risk of phase reversal include young age, type I bipolar disorder, rapid phase change bipolar disorder, substance abuse, mixed state, and a history of similar response to antidepressant therapy.

When using antidepressant monotherapy, a full remission is observed only in 15-20% of patients, and 20-25% of patients relapse within a few months, regardless of whether the antidepressant was continued or discontinued [67].

In accordance with the clinical guidelines for the treatment of depression in bipolar disorder, it is recommended to limit the prescription of antidepressants to a minimum period and, already at the first stage of treatment, use them in combination with an antipsychotic and / or mood stabilizer in order to prevent phase inversion.

Monotherapy with mood stabilizers seems appropriate for mild or moderate symptoms in patients who do not have a suicidal risk [68]. A number of studies have shown good efficacy of lithium carbonate, carbamazepine and lamotrigine in the treatment of depressive conditions in the context of bipolar disorder, however, the development of a thymoanaleptic effect usually takes more than 6 weeks. One double-blind, placebo-controlled study [69] of 195 patients with type I bipolar disorder showed a positive antidepressant effect after 7 weeks of lamotrigine therapy. In another study [70], the addition of the anticonvulsant topiramate or the antidepressant bupropion to normothymic therapy with valproate or lithium in 36 outpatients with bipolar depression found a reduction in depressive symptoms after 2 weeks of treatment. There is also a work [71], in which it was found that the combination of the mood stabilizer and the antidepressant paroxetine leads to an earlier manifestation of the antidepressant effect without phase inversion.

J. Doree et al. [72] found that in cases of failure of antidepressant monotherapy, the combination of an antidepressant with quetiapine is statistically significantly more effective than the combination of an antidepressant with lithium, both in terms of the number of responders (88 and 50%, respectively) and the number of patients who achieved remission (88 and 50%, respectively). 38% respectively).

In the proposed treatment algorithms for bipolar depression, quetiapine at a dose of 600 mg/day or more is the first-line drug for type I bipolar disorder, while it is recommended to start with lamotrigine 50-200 mg/day for type II bipolar depression, and quetiapine is an alternative option in lower doses [73].

Therapy of bipolar depression with atypical antipsychotics is usually recommended for bipolar depression type 1, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, delusions of self-blame, self-deprecation. Thus, olanzapine monotherapy proved to be effective for patients with bipolar depression and comorbid anxiety [27].

Some modern authors [74] insist on the abolition of antidepressant therapy on the 2nd week after the establishment of clinical remission with a gradual dose reduction, but allow the return of thymoanaleptic therapy in case of deterioration of the patient's condition.

Since the end of the last century, scientists and physicians have been increasingly interested in the study of gender specifics in the treatment of depression.

The lower rate of renal filtration and hepatic metabolism in women, the higher percentage of adipose tissue compared to men and, at the same time, lower body weight lead to a higher level of concentration and a longer half-life of therapeutic drugs. These pharmacokinetic features may explain the better efficacy of antidepressant therapy in women and the possibility of using lower dosages [75].

However, a number of studies have found differences in therapeutic response to different groups of antidepressants. A slower response in women compared to men was obtained with TCAs, while women achieved faster clinical improvement with SSRIs [76].

In a study by J. Davidson et al. [77] showed that monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) were more effective than TCAs in women, while men improved more quickly when treated with the latter.

The researchers explain the observed differences by a number of factors. S. Kornstein et al. [76] noted a difference in therapeutic response to sertraline (SSRI) and imipramine (TCA) only in premenopausal women; no differences were found in postmenopausal women. Separate studies have also shown that estrogens can increase serotonergic activity [78]. An assumption was made about the effect of female sex hormones on the pharmacodynamics of antidepressants in terms of stimulating the action of SSRIs and inhibiting the activity of TCAs [76]. It is necessary to take into account the clinical features of depression. In women, depression more often includes atypical symptoms, which may explain the better response to SSRIs and MAO inhibitors [76, 77].

In one of the comparative placebo-controlled studies of venlafaxine (selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor SNRI) and drugs from the SSRI group (fluoxetine, paroxetine, fluvoxamine) in groups of men and women, it was found that in men there were no clinically significant differences in response to drugs, while women treated with venlafaxine had a faster response (at week 2) compared to SSRIs (at week 4) and achieved sustained clinical improvement [79].

A number of studies have noted gender differences not only in the efficacy but also in the tolerability of antidepressants: when using TCAs, men are more likely to experience side effects such as difficulty urinating, sexual dysfunctions, and nausea in women. Adverse events with the use of SSRIs: in men - dyspepsia, sexual dysfunction, frequent urination; in women - nausea, dizziness.

In recent years, the antidepressant Valdoxan (Agomelatine), an agonist of melatonin MT1- and MT2- and an antagonist of serotonin 5-HT2C receptors, has positively proven itself in the treatment of depression, which, due to its unique mechanism of action, has high antidepressant efficacy in depression of various genesis and varying severity, including severe endogenous depressive states [80]. Disorders of circadian rhythms in endogenous depression, manifested by sleep disturbances, diurnal fluctuations in the state with the corresponding dynamics of therapy, are an additional indication for the appointment of agomelatine. The results of one of the meta-analyzes [81] showed that the efficacy of agomelatine is comparable to other antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs), and also has a better tolerability profile, leading to a lower risk of discontinuing treatment due to the development of adverse events. Another meta-analysis [82], which summarized the results of 76 clinical trials (16,389patients) in a study of the efficacy and tolerability of the 10 most common antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder, it was shown that agomelatine was in first place in the number of patients in remission, and also differed in the maximum indicators of good tolerance.

The results of one of the meta-analyzes [81] showed that the efficacy of agomelatine is comparable to other antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs), and also has a better tolerability profile, leading to a lower risk of discontinuing treatment due to the development of adverse events. Another meta-analysis [82], which summarized the results of 76 clinical trials (16,389patients) in a study of the efficacy and tolerability of the 10 most common antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder, it was shown that agomelatine was in first place in the number of patients in remission, and also differed in the maximum indicators of good tolerance.