Lobotomy before and after brain

When Faces Made the Case for Lobotomy

All in Their Heads

By Carla Garnett

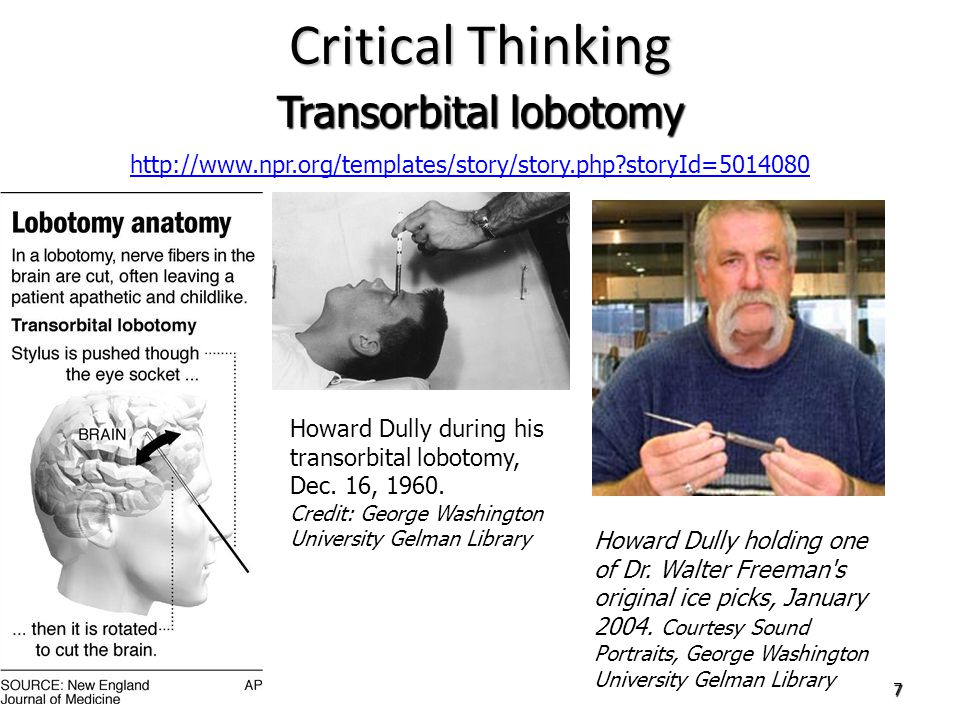

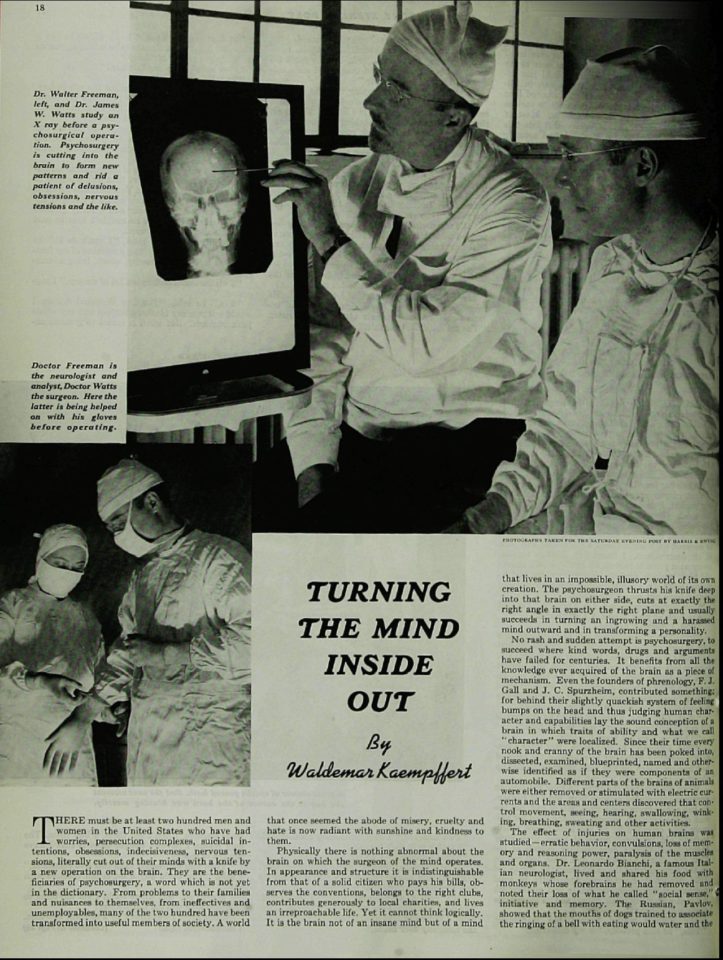

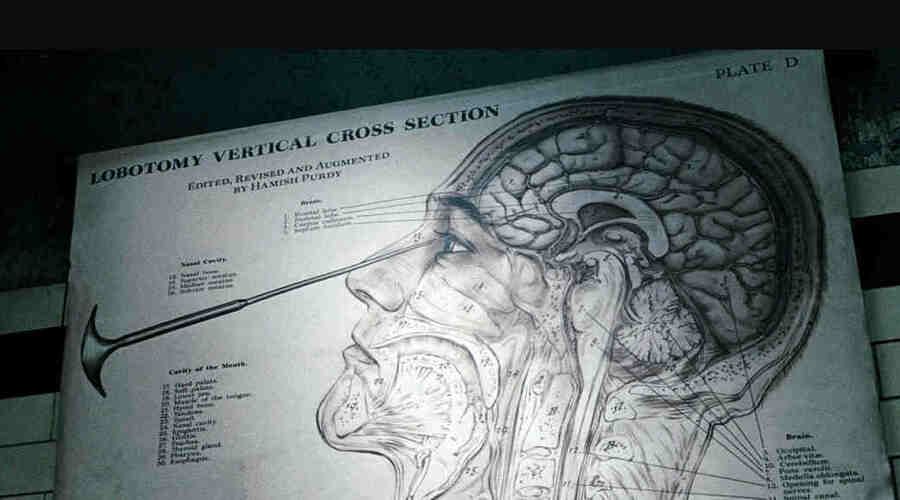

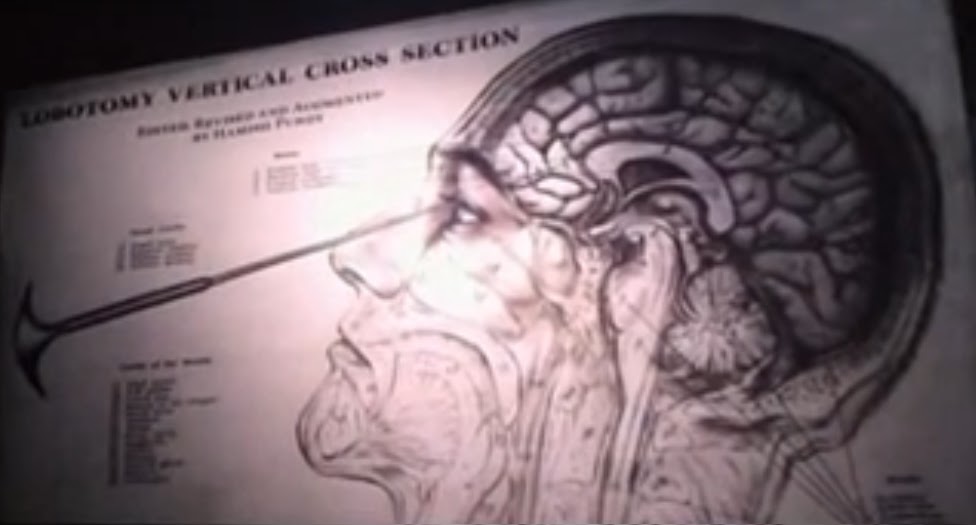

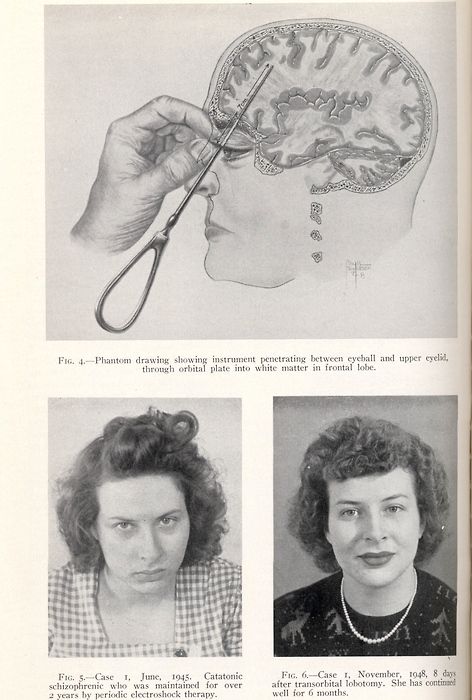

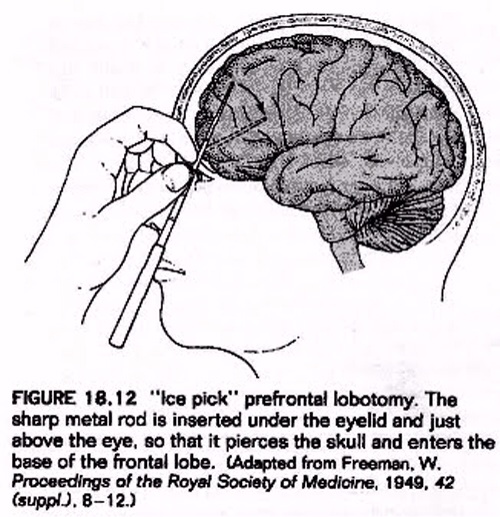

A drawing from Dr. Walter Freeman’s book, Psychosurgery in the Treatment of Mental Disorders and Intractable Pain, shows his icepick-inspired transorbital lobotomy instrument.

If you were mentally ill back in the late 1930s to late 1950s, doctors might have tried to cure you by drilling a hole in your brain and disconnecting the thalamus from the frontal lobe. They may have been convinced to employ this drastic surgery by eccentric neuroscientist Dr. Walter Freeman, “the world’s greatest proponent and pioneer of lobotomy,” who used portraits as scientific proof of concept.

Why did the medical community back then accept what seems preposterous to us now?

That was the fascinating question in “Scientists’ Mind-Body Problems: Lobotomy, Science and the Digital Humanities,” the 2019 NLM James Cassedy Lecture in the History of Medicine delivered Sept. 19 by Dr. Miriam Posner, assistant professor in the information studies department at UCLA.

Dr. Miriam Posner of UCLA discusses “Lobotomy, Science and the Digital Humanities” at an NLM lecture.

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

“This whole lecture is the story of different modes of proof coming in and out of fashion,” she said. “We find ourselves now in a time when data and statistics claim an enormous amount of cultural authority. One of the central questions of digital humanities is, what can statistics capture and what kind of meaning eludes these methods?”

In the mid-20th century, lobotomies were commonly practiced “on tens of thousands of mentally ill people,” Posner pointed out. “We now think of lobotomy as an atrocity and rightfully so, but it’s also important to understand how a lot of very smart, educated people could have believed otherwise during the procedure’s prime.”

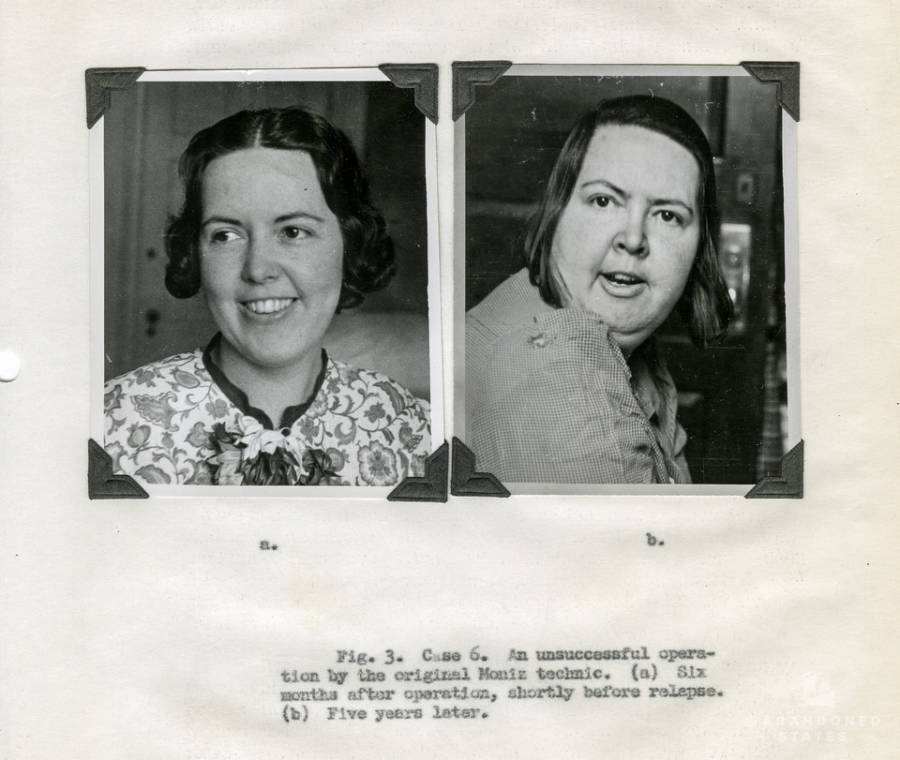

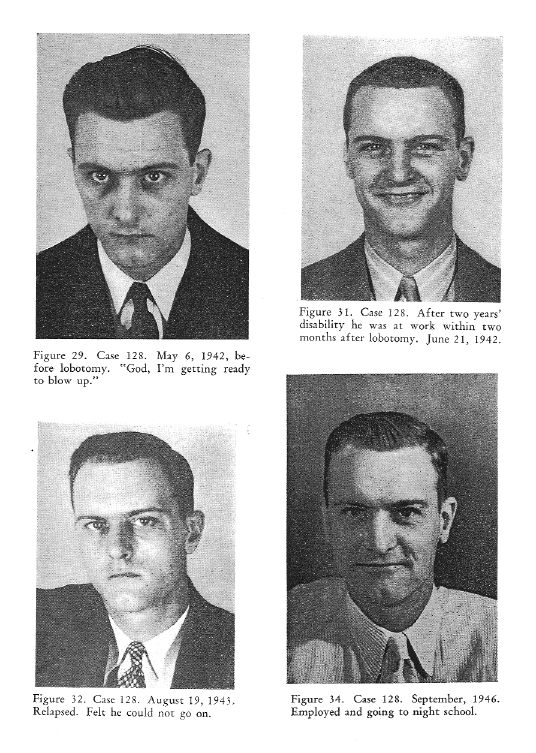

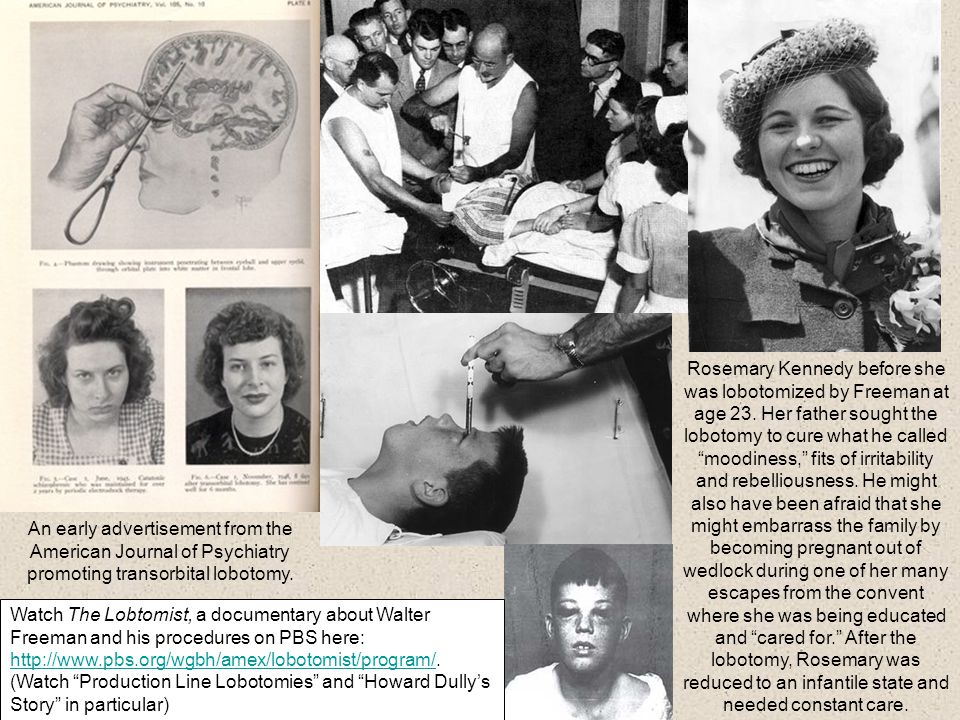

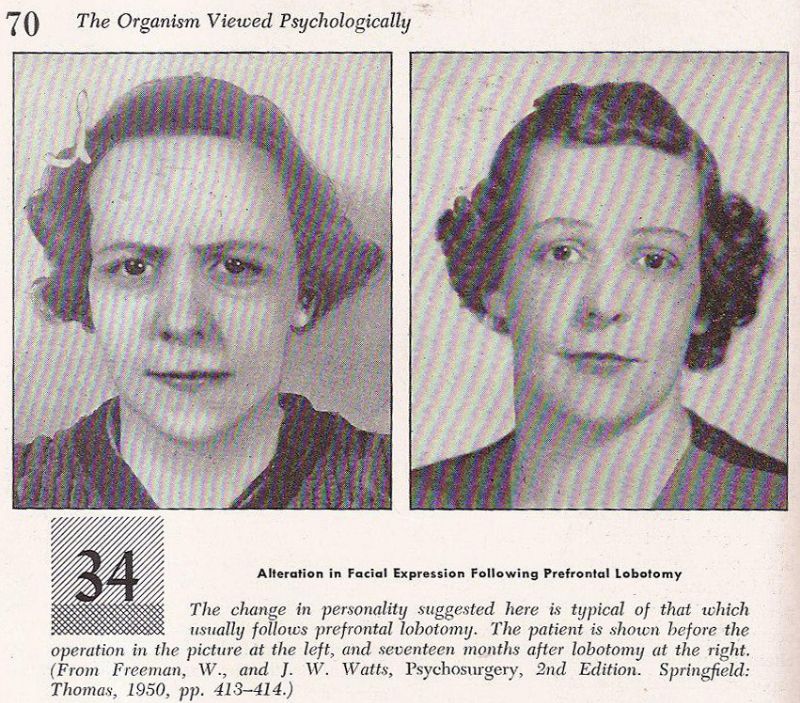

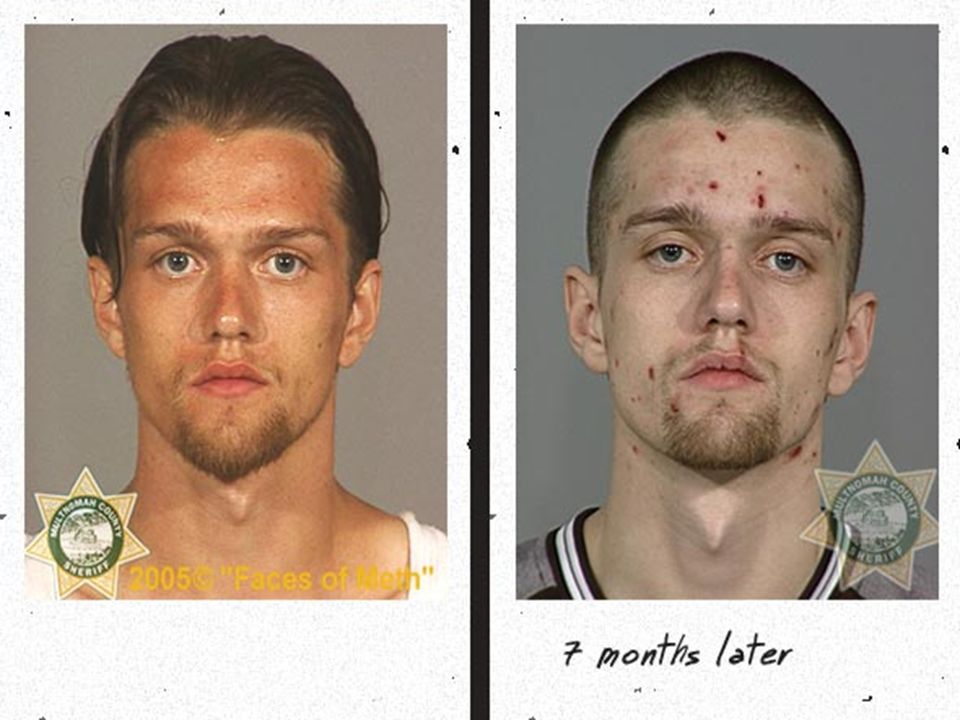

Posner was compelled to examine the surgery’s history, and Freeman’s career, by a photo—and then more photos and old film clips—that she happened to see. The images—before-and-after close-ups of patient faces—were presented in medical journals and textbooks as proof that partial brain excision succeeded in healing mentally ill people.

“It seemed strange to me that there was a time when people’s affect and expressions could be accepted as medical evidence,” Posner recalled. “How could it be that faces made sense as proof 50 years ago?”

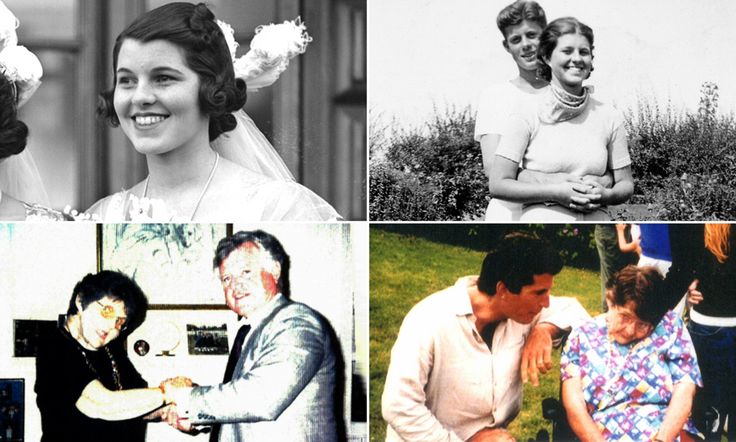

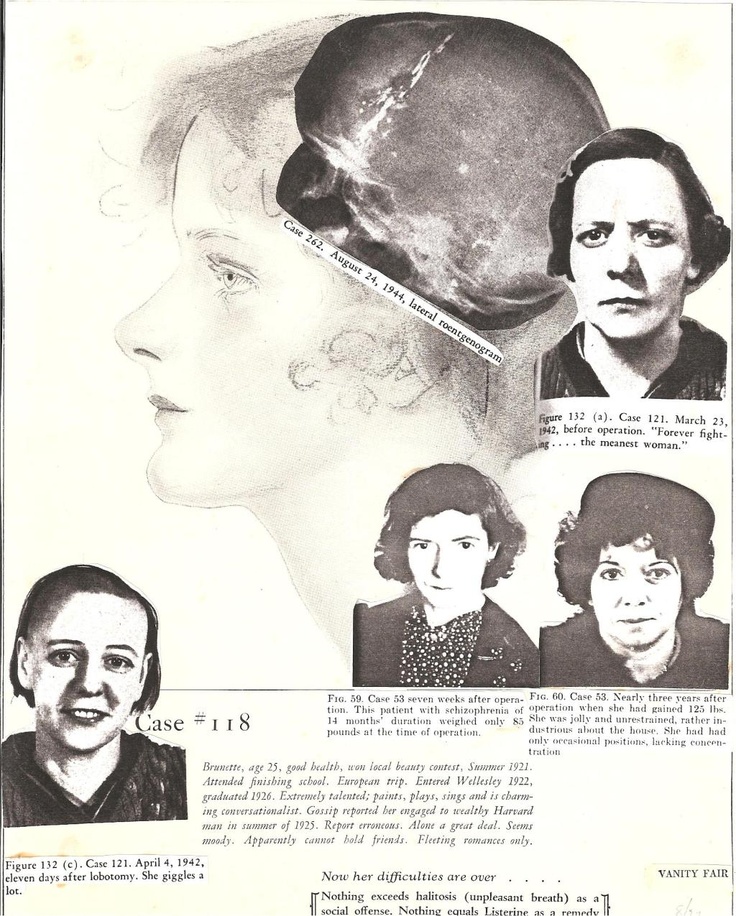

Freeman’s case number 121, a woman he photographed several times: In the first portrait, pre-lobotomy, she looks slightly combative; in the second—after the procedure—she’s smiling. Freeman used the photos as evidence of lobotomy’s effectiveness.

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

Take Freeman’s case number 121, a woman he photographed several times over the course of some 4 years. In the first portrait, a young woman glares into the camera, unsmiling, brows furrowed. She looks slightly combative. The caption notes, “March 23, 1942 before operation. ‘Forever fighting….the meanest woman.’”

Another image shows the same woman, the top front portion of her hair shorn to the scalp. She’s smiling. The caption reads, “April 4, 1942, eleven days after lobotomy. She giggles a lot. ”

”

By the series’ fifth photo, the woman has donned a contemporary ladies’ hat for her portrait, which was taken 4 years post-lobotomy. Images in between captured her modest weight gain and note that she has found regular employment—both circumstances offered as further “evidence” that lobotomy has benefited her. In picture 5, again she’s smiling. Freeman’s caption: “June 15, 1946, three [sic] years after lobotomy. ‘Refused to marry a drunkard.’”

By the series’ fifth photo, the woman has donned a contemporary ladies’ hat for her portrait, which was taken 4 years post-lobotomy.

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

By then, 10 years after Freeman had performed the first lobotomy in 1936, the procedure “was very much on the frontlines of medical science,” said Posner. Freeman’s photos illustrated journal articles that he—and many in the medical establishment then—believed were documentation that his surgeries cured severe mental illness.

“Freeman thought psychosis was the result of excessive self-reflection, thoughts that circled back on themselves over and over again,” Posner explained. “He was being literal when he said lobotomy was a way of cutting those endlessly circling thoughts off within the brain, [a way] of breaking that circle.”

“He was being literal when he said lobotomy was a way of cutting those endlessly circling thoughts off within the brain, [a way] of breaking that circle.”

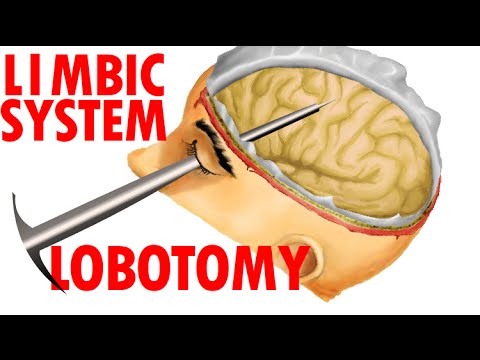

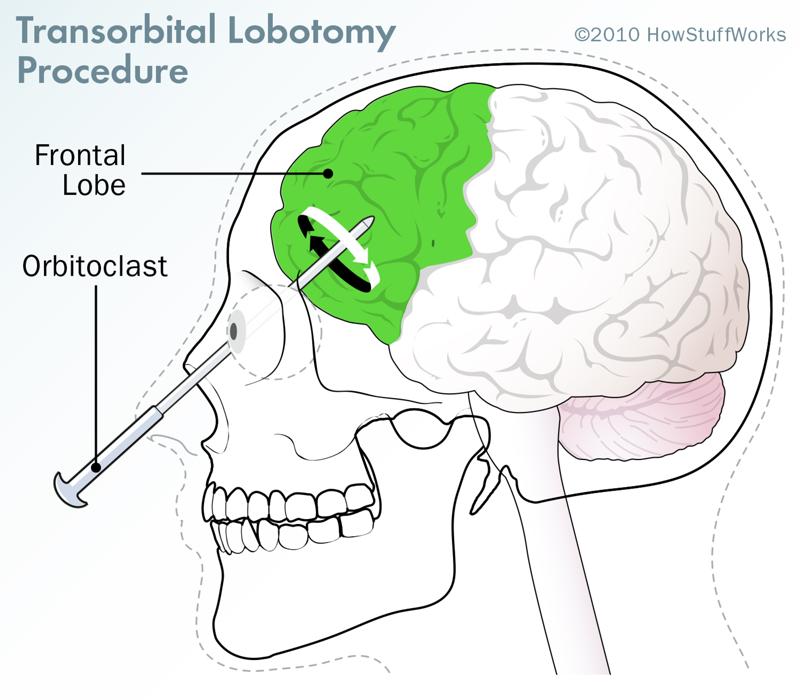

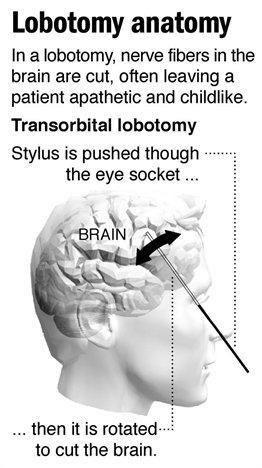

Following Freeman’s lead, hundreds of physicians performed thousands of lobotomies in the United States during the procedure’s prime. By 1945, he had revolutionized the technique. By inserting a long, thin instrument—modeled after an icepick—to pierce the brain via the patient’s eye socket, Freeman devised what he called the “transorbital lobotomy.”

With this invention, he claimed he no longer needed a drill, sterile field nor surgical scrubs. His longtime operating room partner quit in protest. Freeman was undeterred, taking operations on the road by way of a camper van. He traveled the country, performed lobotomies and gave lectures “at an almost frenzied pace,” Posner said.

In a sort of makeshift longitudinal study, Freeman diligently kept a journal, recording his work in words and images, sometimes logging more than two dozen lobotomies in a single day. In a stretch of August 1958 entries, he journeyed from Lincoln, Nebraska, to St. Joseph, Missouri, to Cherokee, and then Independence, Iowa—50 transorbital lobotomies in just more than 4 days across 650 miles of America’s heartland. His new scaled-down method went quicker sans drill, O.R. and surgical assistants.

In a stretch of August 1958 entries, he journeyed from Lincoln, Nebraska, to St. Joseph, Missouri, to Cherokee, and then Independence, Iowa—50 transorbital lobotomies in just more than 4 days across 650 miles of America’s heartland. His new scaled-down method went quicker sans drill, O.R. and surgical assistants.

A slide from Posner's talk shows neuroscientist Freeman, “the world’s greatest proponent and pioneer of lobotomy,” performing the surgery.

Only the development of Thorazine as an effective, less invasive anti-psychotic brought the widespread practice of lobotomy to an end, Posner reported. The medical community quickly moved on. Freeman, however, still held that his procedure was better.

So lobotomy fell out of fashion, but in the course of her research, Posner learned there was more to the story of portraits as proof.

“There’s actually a solid foundation for Freeman’s belief that photographs constituted acceptable medical evidence,” she recounted. “He was drawing on centuries of psychiatric and philosophic tradition that saw the face as a legitimate and reliable indicator of the contents of the soul. ”

”

Posner traced the ideology back to 18th century theologian Johann Kasper Lavater, a physiognomy advocate who argued that the face revealed specifics about a person’s character. Some hundred years later, French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot “used photography as a tool of scientific scrutiny.” He gained—and shared—medical insights from having his patients look directly at the camera lens for “the clinical gaze.”

By 1920, Dr. Harvey Cushing was transforming the field of neurosurgery with, among other innovations, his extensive documentation and collection of patient images and brain samples.

“So Freeman’s photographic practice was not as unhinged as it might have seemed at first,” explained Posner. “He actually inherited a long tradition of using faces to demonstrate sanity or insanity.”

Sure, Freeman’s approach to scientific corroboration seemed unorthodox and even shocking when viewed initially, Posner said, but placed in context, our perspective may have changed.

In her history of medicine talk, Posner examines evidence now viewed in the digital age.

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

“When we talk about the history of psychiatry, we have to be careful about which mode of evidence we use to bolster our claim,” she cautioned. “The story the journals tell is different from the psychiatry physicians performed for each other on the lecture stage…The oral performance of medicine could differ markedly from the way medicine is articulated and circulated in medical journals. It’s more theatrical, more improvisational and more visual.”

As 21st century medicine ventures ever farther into the era of Big Data and its widely foretold promise, a history lesson on how scientific evidence is derived, used and communicated to inform treatment strategy seems timely.

“Freeman’s photos suggest to me that for all of 20th century medicine that’s well documented,” Posner concluded, “there are apparently important features of its visual culture that are yet to be excavated. ”

”

Her entire lecture is archived at https://videocast.nih.gov/summary.asp?Live=29010&bhcp=1.

Howard Dully's Journey : NPR

Hear a 1968 Diary Entry from Dr. Walter Freeman

Howard Dully during his transorbital lobotomy, Dec. 16, 1960. George Washington University Gelman Library hide caption

Enlarge

toggle caption

George Washington University Gelman Library

On Jan. 17, 1946, a psychiatrist named Walter Freeman launched a radical new era in the treatment of mental illness in this country. On that day, he performed the first-ever transorbital or "ice-pick" lobotomy in his Washington, D.C., office. Freeman believed that mental illness was related to overactive emotions, and that by cutting the brain he cut away these feelings.

Freeman believed that mental illness was related to overactive emotions, and that by cutting the brain he cut away these feelings.

Freeman, equal parts physician and showman, became a barnstorming crusader for the procedure. Before his death in 1972, he performed transorbital lobotomies on some 2,500 patients in 23 states.

One of Freeman's youngest patients is today a 56-year-old bus driver living in California. Over the past two years, Howard Dully has embarked on a quest to discover the story behind the procedure he received as a 12-year-old boy.

In researching his story, Dully visited Freeman's son; relatives of patients who underwent the procedure; the archive where Freeman's papers are stored; and Dully's own father, to whom he had never spoken about the lobotomy.

Dr. Walter Freeman operating on a patient, c. 1950. University Archives, The Gelman Library, The George Washington University hide caption

toggle caption

University Archives, The Gelman Library, The George Washington University

"If you saw me you'd never know I'd had a lobotomy," Dully says. "The only thing you'd notice is that I'm very tall and weigh about 350 pounds. But I've always felt different — wondered if something's missing from my soul. I have no memory of the operation, and never had the courage to ask my family about it. So two years ago I set out on a journey to learn everything I could about my lobotomy."

"The only thing you'd notice is that I'm very tall and weigh about 350 pounds. But I've always felt different — wondered if something's missing from my soul. I have no memory of the operation, and never had the courage to ask my family about it. So two years ago I set out on a journey to learn everything I could about my lobotomy."

Neurologist Egas Moniz performed the first brain surgery to treat mental illness in Portugal in 1935. The procedure, which Moniz called a "leucotomy," involved drilling holes in the patient's skull to get to the brain. Freeman brought the operation to America and gave it a new name: the lobotomy. Freeman and his surgeon partner James Watts performed the first American lobotomy in 1936. Freeman and his lobotomy became famous. But soon he grew impatient.

"My father decided that there must be a better way," says Freeman's son, Frank. Walter Freeman set out to create a new procedure, one that didn't require drilling holes in the head: the transorbital lobotomy. Freeman was convinced that his 10-minute lobotomy was destined to revolutionize medicine. He spent the rest of his life trying to prove his point.

Freeman was convinced that his 10-minute lobotomy was destined to revolutionize medicine. He spent the rest of his life trying to prove his point.

Howard Dully holding one of Dr. Walter Freeman's original ice picks, January 2004. Courtesy Sound Portraits, George Washington University Gelman Library hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy Sound Portraits, George Washington University Gelman Library

As those who watched the procedure described it, a patient would be rendered unconscious by electroshock. Freeman would then take a sharp ice pick-like instrument, insert it above the patient's eyeball through the orbit of the eye, into the frontal lobes of the brain, moving the instrument back and forth. Then he would do the same thing on the other side of the face.

Then he would do the same thing on the other side of the face.

Freeman performed the procedure for the first time in his Washington, D.C., office on Jan. 17, 1946. His patient was a housewife named Ellen Ionesco. Her daughter, Angelene Forester, was there that day.

Howard, standing in front, with his parents, June Dully and Rodney Dully (holding Howard's brother Brian), in Oakland, Calif., c. 1950. Courtesy Howard Dully hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy Howard Dully

"She was absolutely violently suicidal beforehand," Forester says of her mother. "After the transorbital lobotomy there was nothing. It stopped immediately. It was just peace. I don't know how to explain it to you, it was like turning a coin over. That quick. So whatever he did, he did something right."

That quick. So whatever he did, he did something right."

Ellen Ionesco, now 88 years old, lives in a nursing home in Virginia. "He was just a great man. That's all I can say," she says. But Ionesco says she remembers little about Freeman, including what he looked like.

By 1949, the transorbital lobotomy had caught on. Freeman lobotomized patients in mental institutions across the country.

"There were some very unpleasant results, very tragic results and some excellent results and a lot in between," says Dr. Elliot Valenstein, who wrote Great and Desperate Cures, a book about the history of lobotomies.

Valenstein says the procedure "spread like wildfire" because alternative treatments were scarce. "There was no other way of treating people who were seriously mentally ill," he says. "The drugs weren't introduced until the mid-1950s in the United States, and psychiatric institutions were overcrowded... [Patients and their families] were willing to try almost anything. "

"

By 1950, Freeman's lobotomy revolution was in full swing. Newspapers described it as easier than curing a toothache. Freeman was a showman and liked to shock his audience of doctors and nurses by performing two-handed lobotomies: hammering ice picks into both eyes at once. In 1952, he performed 228 lobotomies in a two-week period in West Virginia alone. (He lobotomized 25 women in a single day.) He decided that his 10-minute lobotomy could be used on others besides the incurably mentally ill.

Anna Ruth Channels suffered from severe headaches and was referred to Freeman in 1950. He prescribed a transorbital lobotomy. The procedure cured Channels of her headaches, but it left her with the mind of a child, according to her daughter, Carol Noelle. "Just as Freeman promised, she didn't worry," Noelle says. "She had no concept of social graces. If someone was having a gathering at their home, she had no problem with going in to their house and taking a seat, too."

Howard Dully's mother died of cancer when he was 5. His father remarried and, Dully says, "My stepmother hated me. I never understood why, but it was clear she'd do anything to get rid of me."

His father remarried and, Dully says, "My stepmother hated me. I never understood why, but it was clear she'd do anything to get rid of me."

A search of Dully's records among Freeman's files archived at George Washington University turned up clues about why Freeman lobotomized him.

Howard Dully's stepmother, Lou, in California, 1955. Courtesy Howard Dully hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy Howard Dully

Howard Dully, tree climbing in Los Altos, Calif., 1955. Courtesy Howard Dully hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy Howard Dully

"My Lobotomy" was produced by Piya Kochhar and Dave Isay at Sound Portraits Productions. The editor was Gary Covino. Special thanks to Larry Blood and Barbara Dully. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting with additional support from the National Endowment for the Arts.

The editor was Gary Covino. Special thanks to Larry Blood and Barbara Dully. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting with additional support from the National Endowment for the Arts.

According to Freeman's notes, Lou Dully said she feared her stepson, whom she described as defiant and savage looking. "He doesn't react either to love or to punishment," the notes say of Howard Dully. "He objects to going to bed but then sleeps well. He does a good deal of daydreaming and when asked about it he says 'I don't know.' He turns the room's lights on when there is broad sunlight outside."

On Nov. 30, 1960, Freeman wrote: "Mrs. Dully came in for a talk about Howard. Things have gotten much worse and she can barely endure it. I explained to Mrs. Dully that the family should consider the possibility of changing Howard's personality by means of transorbital lobotomy. Mrs. Dully said it was up to her husband, that I would have to talk with him and make it stick. "

"

Then on Dec. 3, 1960: "Mr. and Mrs. Dully have apparently decided to have Howard operated on. I suggested [they] not tell Howard anything about it."

In an entry dated Jan. 4, 1961, two and a half weeks after the boy's lobotomy, Freeman wrote: "I told Howard what I'd done to him... and he took it without a quiver. He sits quietly, grinning most of the time and offering nothing."

Dully says that when Lou Dully realized the operation didn't turn him "into a vegetable, she got me out of the house. I was made a ward of the state.

"It took me years to get my life together. Through it all I've been haunted by questions: 'Did I do something to deserve this?, Can I ever be normal?', and most of all, 'Why did my dad let this happen?'"

For more than 40 years, Howard Dully had never discussed the lobotomy with his father. In late 2004, Rodney Dully agreed to talk with his son about the operation.

"So how did you find Dr. Freeman?" Howard Dully asks.

"I didn't," Rodney Dully replies, adding that Lou Dully was the one. "She took you... I think she tried some other doctors who said, '...there's nothing wrong here. He's a normal boy.' It was the stepmother problem."

"She took you... I think she tried some other doctors who said, '...there's nothing wrong here. He's a normal boy.' It was the stepmother problem."

Why would a father let this happen to his son?

"I got manipulated, pure and simple," Rodney Dully says. "I was sold a bill of goods. She sold me and Freeman sold me. And I didn't like it."

The meeting proves cathartic for Howard Dully. "Although he refuses to take any responsibility, just sitting here with my dad and getting to ask him about my lobotomy is the happiest moment of my life," Howard Dully says.

Rebecca Welch's mother Anita was lobotomized by Freeman for postpartum depression in 1953. After spending most of her life in mental institutions, Anita McGee now lives in a nursing home in Birmingham, Ala. Rebecca visits her every week. She believes Walter Freeman's lobotomy destroyed her mother's life.

"I personally think that something in Dr. Freeman wanted to be able to conquer people and take away who they were," Welch says.

Patricia Moen was lobotomized by Walter Freeman in 1962 at the age of 36. As a staff physician at Ohio, Wolfhard Baumgartel observed Freeman perform a series of lobotomies. Harvey Wang hide caption

toggle caption

Harvey Wang

Read Their Oral Histories

At a meeting in the nursing home, Welch and Howard Dully find common ground in their experiences with Freeman. "It does wonders to know that other people have the same pain," Dully says.

Howard Dully's two-year journey in search of the story behind his lobotomy is over. "I'll never know what I lost in those 10 minutes with Dr. Freeman and his ice pick," Dully says. "By some miracle it didn't turn me into a zombie, crush my spirit or kill me. But it did affect me. Deeply. Walter Freeman's operation was supposed to relieve suffering. In my case it did just the opposite. Ever since my lobotomy I've felt like a freak, ashamed."

But it did affect me. Deeply. Walter Freeman's operation was supposed to relieve suffering. In my case it did just the opposite. Ever since my lobotomy I've felt like a freak, ashamed."

But now, after meeting with Welch and her mother, Dully says his suffering is over. "I know my lobotomy didn't touch my soul. For the first time I feel no shame. I am, at last, at peace."

After 2,500 operations, Freeman performed his final ice-pick lobotomy on a housewife named Helen Mortenson in February 1967. She died of a brain hemorrhage, and Freeman's career was finally over. Freeman sold his home and spent the rest of his days traveling the country in a camper, visiting old patients, trying desperately to prove that his procedure had transformed thousands of lives for the better. Freeman died of cancer in 1972.

Additional interviews, oral histories and information about the documentary:

'My Lobotomy'

In 2004, for the first time since the operation, Rodney Dully, Howard Dully's father, agreed to discuss the lobotomy with his son.

Walter Freeman's son Frank tells Howard Dully about the origins of the transorbital lobotomy developed by Dr. Freeman.

Howard Dully meets Carol Noelle, who describes the results of a Freeman lobotomy on her mother.

Audio will be available later today.

Great & Desperate Cures by Elliot S. Valenstein (Basic Books, 1986)

Last Resort: Psychosurgery and the Limits of Medicine by Jack Pressman (Cambridge University Press, 1998)

Psychosurgery.org: A site dedicated to lobotomy survivors and their relatives

'The Lobotomist,' a biography of Walter Freeman by Jack El-Hai

The Walter Freeman / James Watts Collection at George Washington University

An Account of One of Dr. Walter Freeman's Transorbital Lobotomies

consequences of brain lobotomy, history of brain lobotomy operation

Gleb Pospelovo lobotomy - the most famous and darkest of psychosurgical operations

- Oh, yes, after treatment, he will turn into a vegetable! to persuade the patient and his relatives to hospitalization. Everyone knows that in psychiatric hospitals people are "zombified", "burned out the brain", "poisoned", "turned into a plant" - in general, they destroy as a person in all possible ways.

Everyone knows that in psychiatric hospitals people are "zombified", "burned out the brain", "poisoned", "turned into a plant" - in general, they destroy as a person in all possible ways.

And before the hospital, the patient was just a feast for the eyes, aha!

Actually, this way of thinking has a very scientific name: social stigmatization. In fact, a person who is discharged from a psychiatric hospital is often completely different from what his relatives are used to. Was sociable - became withdrawn, was active, nimble - became inhibited and lethargic. And the media, books, cinema - willingly show exactly how pests in white coats carry out their hellish experiments on people. I will tell you a "secret": if anything turns our patients into "plants", it is not a cure, but a disease. However, this was not always the case…

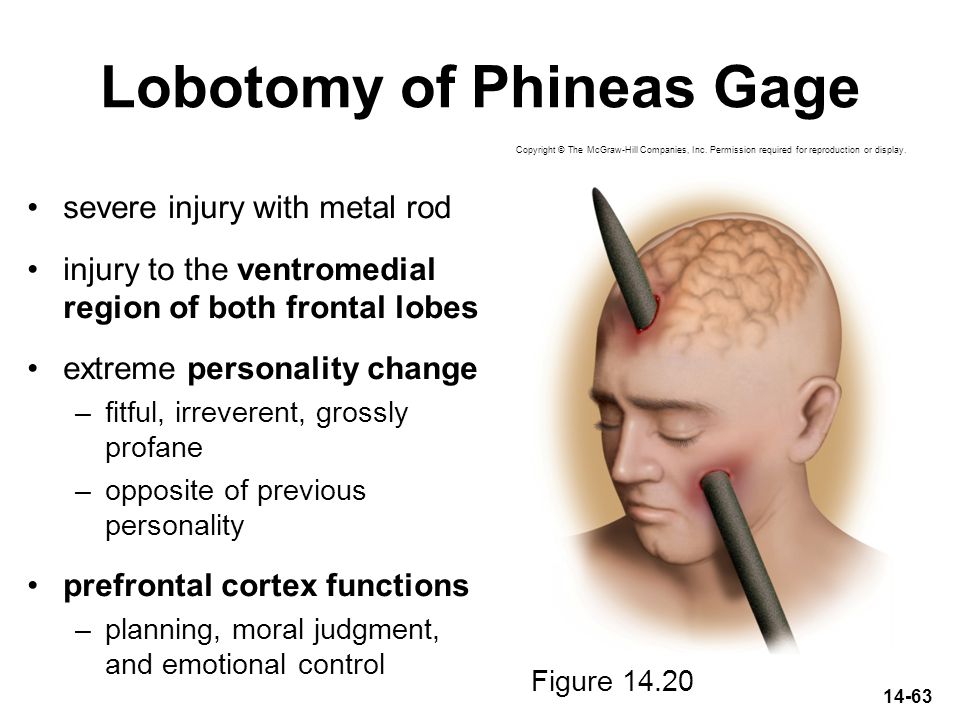

Do you remember the famous book (or its adaptation) One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and the fate of its main character, McMurphy? Let me remind you: McMurphy was subjected to a lobotomy for violations of the hospital regime. Cheerful, self-confident, groovy rogue-simulant turns into a weak-minded, into a drooling ruin. The author of the novel, Ken Kesey, who worked as an orderly in a mental hospital, described the "frontal syndrome" or "frontal lobe syndrome" that developed in people after lobotomy surgery.

Cheerful, self-confident, groovy rogue-simulant turns into a weak-minded, into a drooling ruin. The author of the novel, Ken Kesey, who worked as an orderly in a mental hospital, described the "frontal syndrome" or "frontal lobe syndrome" that developed in people after lobotomy surgery.

A bold idea

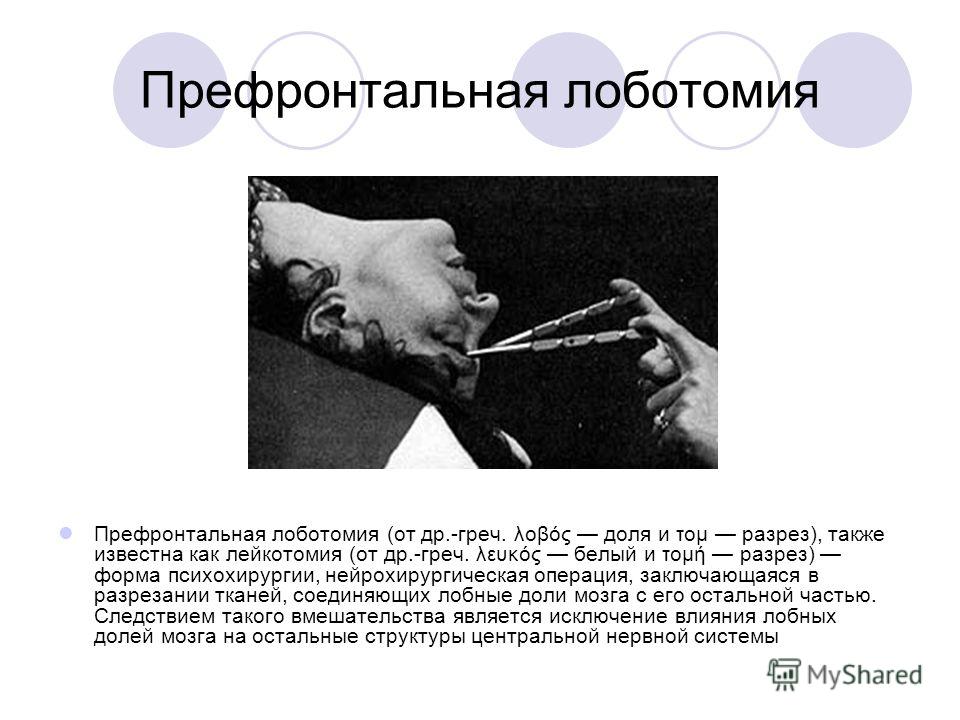

Brain lobotomy was developed in 1935 by the Portuguese psychiatrist and neurosurgeon Egas Moniz. In 1935, at a conference, he heard a report on the consequences of damage to the prefrontal zone in chimpanzees. Although the focus of this report was on learning difficulties associated with damage to the frontal lobes, Moniz was particularly interested in how one monkey became calmer and more docile after surgery. He hypothesized that the intersection of nerve fibers in the frontal lobe can help in the treatment of mental disorders, in particular - schizophrenia (the nature of which was still very vaguely understood). Moniz believed that the procedure was indicated for patients in serious condition or those whom aggressiveness made socially dangerous. Moniz performed his first operation at 1936 year. He called it "leukotomy": a loop was inserted into the brain with the help of a guide, and the white matter of the neuronal connections connecting the frontal lobes with other parts of the brain was cut through with rotational movements.

Moniz performed his first operation at 1936 year. He called it "leukotomy": a loop was inserted into the brain with the help of a guide, and the white matter of the neuronal connections connecting the frontal lobes with other parts of the brain was cut through with rotational movements.

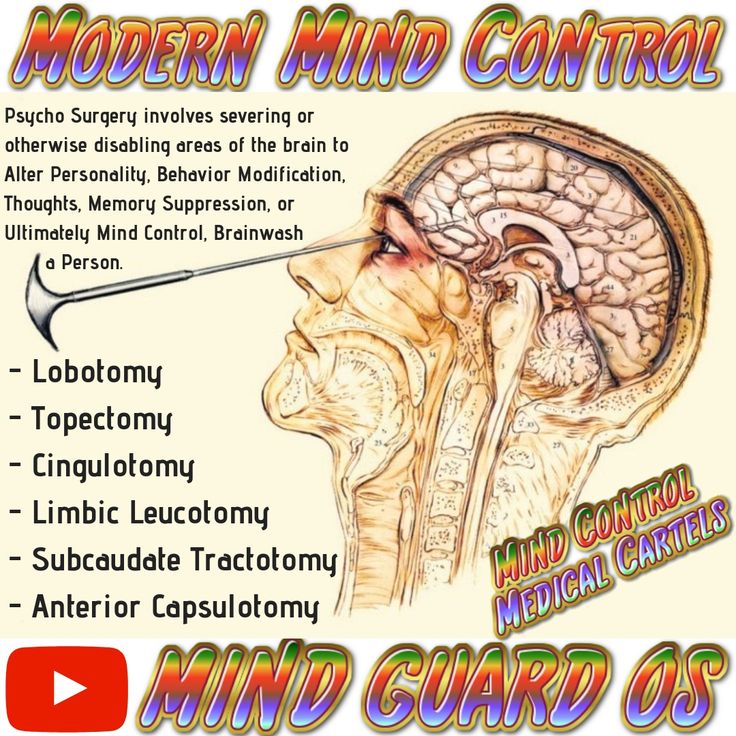

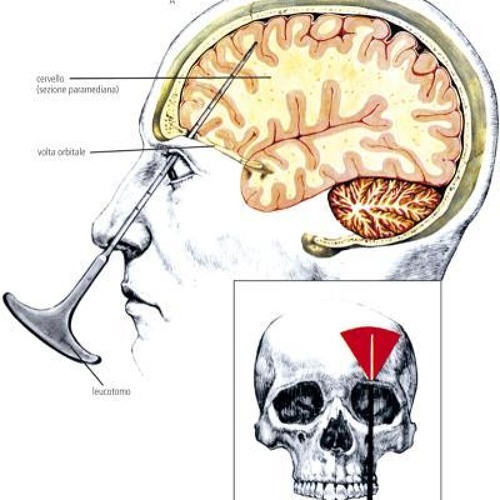

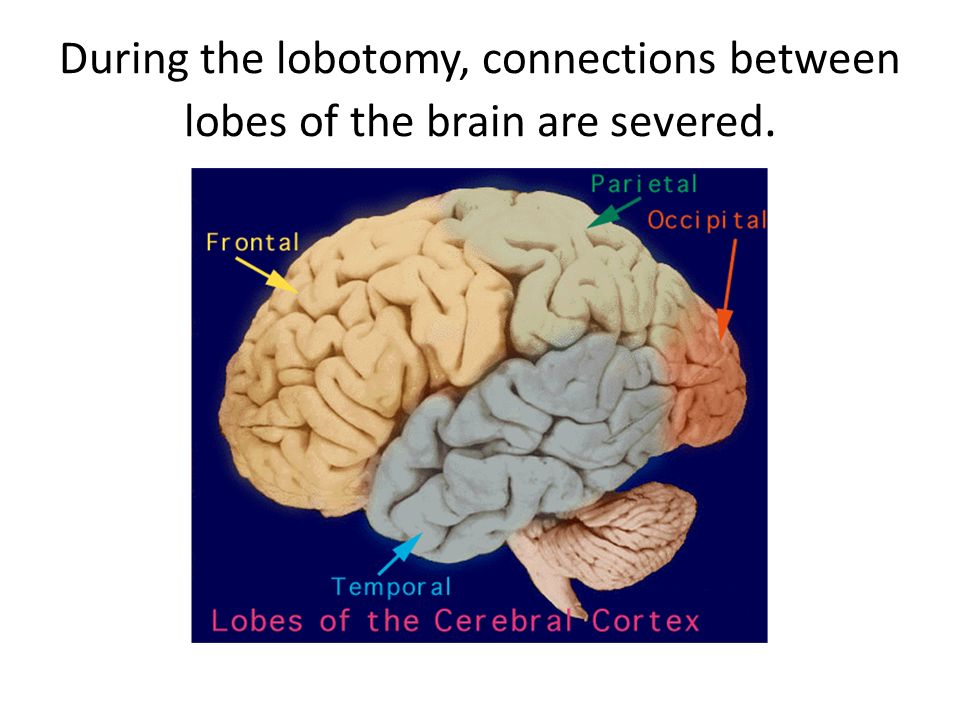

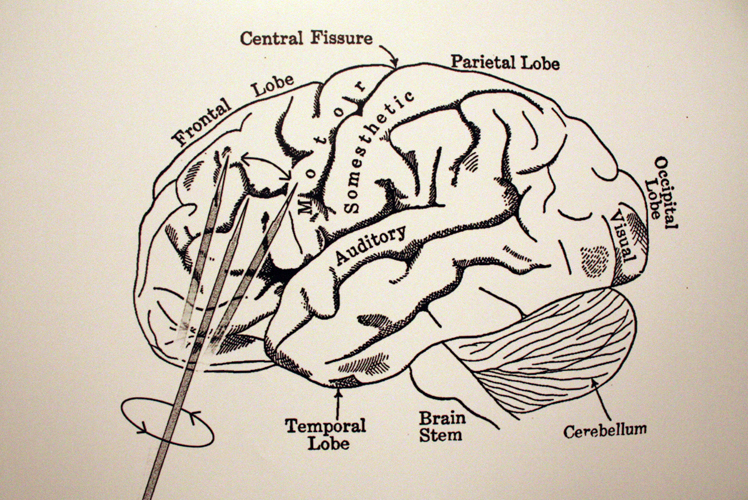

Prefrontal lobotomy, or leucotomy (from other Greek λοβός — share and τομή — cut), — brain surgery, in which a dissection of the white matter of the frontal lobes of the brain is performed on one or both sides, separation of the cortex from the lower parts of the brain. The consequence of such an intervention is the exclusion of the influence of the frontal lobes of the brain on the rest of the structures of the central nervous system.

Moniz performed about a hundred of these operations and observed patients. He liked the results, and in 1936 the Portuguese published the results of the surgical treatment of twenty of his first patients: seven of them recovered, seven improved, and six showed no positive dynamics.

Egas Moniz was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1949 "for his discovery of the therapeutic effects of leucotomy in certain mental illnesses". Since the Monish Prize, leucotomy has become more widely used.

So, Egas Moniz, in his “lobotomy” practice, observed hardly two dozen patients; he never saw most of the others after the operation. Moniz has written several articles and books on lobotomy. Criticism followed: opponents argued that the changes after the operation most of all resemble the consequences of a brain injury and, in fact, represent a degradation of the personality. Many believed that brain mutilation could not improve brain function and damage could lead to the development of meningitis, epilepsy, and brain abscesses. Despite this, Moniz's report (Prefrontal leucotomy. Surgical treatment of certain psychoses, Torino, 1937) led to rapid adoption of the procedure on an experimental basis by individual clinicians in Brazil, Cuba, Italy, Romania, and the United States.

In the Land of Opportunity

American psychiatrist Walter Jay Freeman became the leading promoter of this operation. He developed a new technique that did not require drilling of the patient's skull and called it "transorbital lobotomy". Freeman aimed the narrow end of a surgical instrument, resembling an ice pick, at the eye socket bone, pierced a thin layer of bone with a surgical hammer, and inserted the instrument into the brain. After that, the fibers of the frontal lobes of the brain were cut with the movement of the knife handle. Freeman argued that the procedure would remove the emotional component from the patient's "mental illness". The first operations were carried out with a real ice pick. Subsequently, Freeman developed special instruments for this purpose - the leukotome, and then the orbitoclast.

In the 1940s, lobotomy in the United States became more common for purely economic reasons: the "cheap" method allowed the "treatment" of many thousands of Americans held in closed psychiatric institutions, and could reduce the costs of these institutions by a million dollars a day ! Leading newspapers wrote about the successes of the lobotomy, drawing public attention to it. It is worth noting that at that time there were no effective methods of treating mental disorders, and cases of returning patients from closed institutions to the community were extremely rare.

It is worth noting that at that time there were no effective methods of treating mental disorders, and cases of returning patients from closed institutions to the community were extremely rare.

In the early 1950s, about five thousand lobotomies were performed in the United States a year. Between 1936 and the late 1950s, between 40,000 and 50,000 Americans were lobotomized. The indications were not only schizophrenia, but also severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lobotomy was often performed by doctors who had no surgical training. Although not trained as a surgeon, Freeman nevertheless performed about 3,500 of these operations, traveling around the country in his own van, which he called the "lobotomobile".

Lobotomy was widely used not only in the USA, but also in other countries of the world - Great Britain, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Japan, the USSR. In European countries, tens of thousands of patients underwent this operation

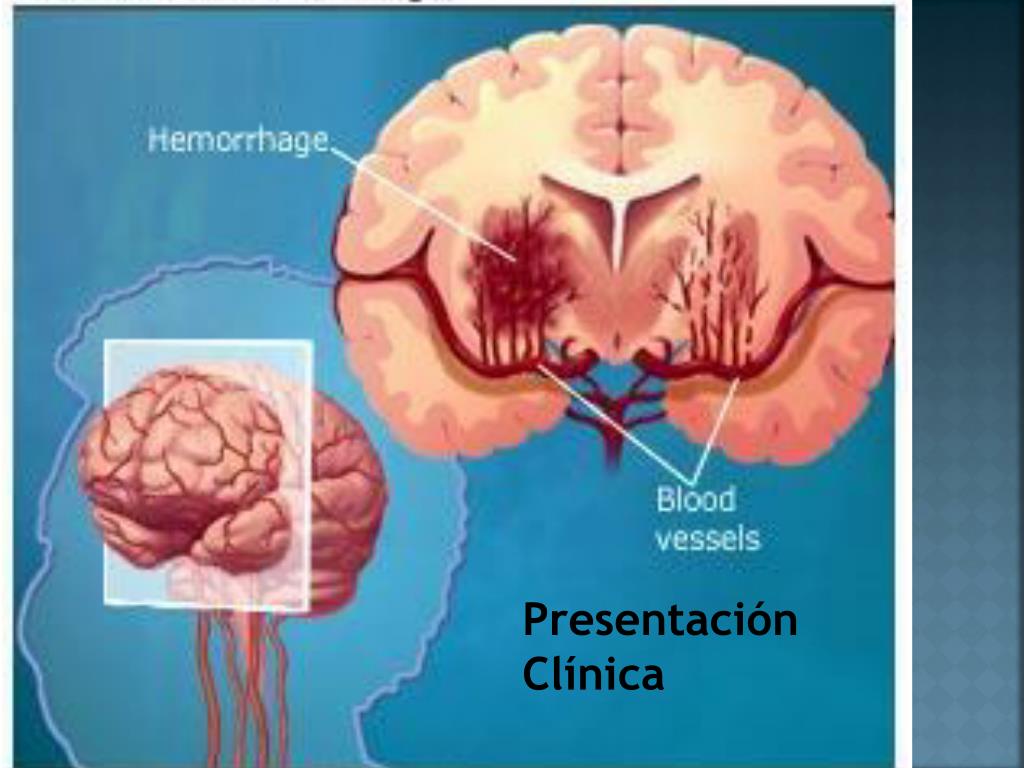

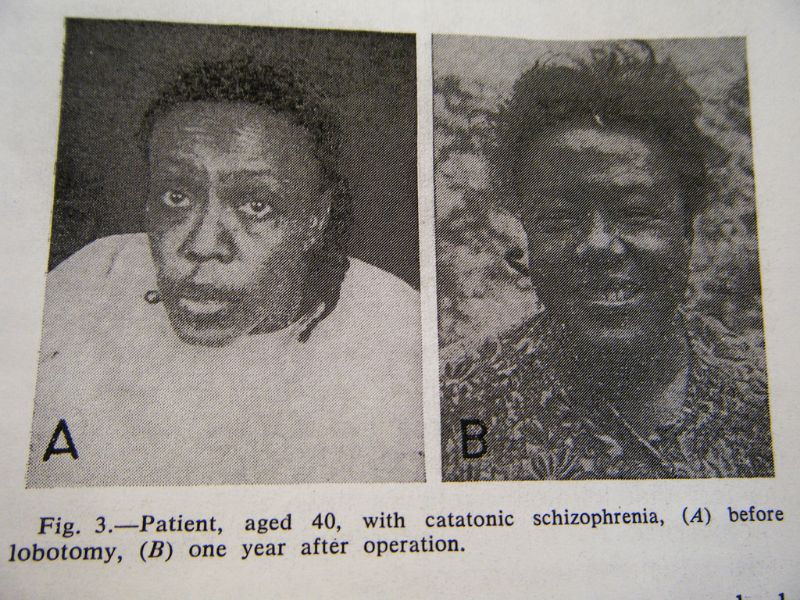

The result on the face

Already in the late 40s, psychiatrists "saw" that the first studies of lobotomy were carried out without a solid methodology: they operated with incomparable methods on patients with different diagnoses. Whether or not recovery has occurred is a question that has often been decided on the basis of such a criterion as improving the patient's manageability. At 19In the 1950s, more thorough research revealed that, in addition to death, which was observed in 1.5–6% of those operated on, lobotomy can cause seizures, large weight gain, loss of coordination, partial paralysis, urinary incontinence and other problems. Standard tests of intelligence and memory usually did not show any significant deterioration. Patients retained all types of sensitivity and motor activity, they did not experience impairments in recognition, practical skills and speech, but complex forms of mental activity disintegrated. More subtle changes have often been reported in the form of reduced self-control, foresight, creativity, and spontaneous action; selfishness and lack of concern for others. At the same time, criticism of one's own behavior was significantly reduced.

Whether or not recovery has occurred is a question that has often been decided on the basis of such a criterion as improving the patient's manageability. At 19In the 1950s, more thorough research revealed that, in addition to death, which was observed in 1.5–6% of those operated on, lobotomy can cause seizures, large weight gain, loss of coordination, partial paralysis, urinary incontinence and other problems. Standard tests of intelligence and memory usually did not show any significant deterioration. Patients retained all types of sensitivity and motor activity, they did not experience impairments in recognition, practical skills and speech, but complex forms of mental activity disintegrated. More subtle changes have often been reported in the form of reduced self-control, foresight, creativity, and spontaneous action; selfishness and lack of concern for others. At the same time, criticism of one's own behavior was significantly reduced.

Patients could answer ordinary questions or perform habitual actions, but the performance of any complex, meaningful and purposeful acts became impossible. They stopped experiencing their failures, experiencing hesitation, conflicts, and most often were in a state of indifference or euphoria. People who were previously energetic, restless, or aggressive in nature may develop changes towards impulsiveness, rudeness, emotional breakdowns, primitive humor, and unreasonable ambitions.

They stopped experiencing their failures, experiencing hesitation, conflicts, and most often were in a state of indifference or euphoria. People who were previously energetic, restless, or aggressive in nature may develop changes towards impulsiveness, rudeness, emotional breakdowns, primitive humor, and unreasonable ambitions.

In the USSR, special techniques for performing lobotomy were developed - much more accurate in the surgical sense and sparing in relation to the patient. The surgical method was offered only in cases of failure of long-term treatment, which included insulin therapy and electroshock. All patients underwent a general clinical and neurological examination and were carefully studied by psychiatrists. After the operation, both acquisitions in the emotional sphere, behavior and social adequacy, as well as possible losses, were recorded. The lobotomy method itself was recognized as fundamentally acceptable, but only in the hands of experienced neurosurgeons and in cases where the lesion was recognized as irreversible.

With maintenance therapy with nootropics and drugs that correct mental disorders, a significant improvement in the condition was possible, which could last for several years, but the end result still remained unpredictable. As Freeman himself noted, after hundreds of operations performed by him, about a quarter of patients were left to live with the intellectual capabilities of a pet, but "we are quite satisfied with these people ...".

Beginning of end

The decline of lobotomy began in the 1950s after serious neurological complications of the operation became apparent. In the future, lobotomy was prohibited by law in many countries - data have accumulated about the relatively low effectiveness of the operation and its greater danger compared to antipsychotics, which were becoming more and more perfect and actively introduced into psychiatric practice.

In the early 70s, the lobotomy gradually faded away, but in some countries continued to operate until the end of the 80s. In France between 19Between 80 and 1986, 32 lobotomies were performed, during the same period - 70 in Belgium and about 15 at the Massachusetts Hospital; about 15 operations were performed annually in the UK.

In France between 19Between 80 and 1986, 32 lobotomies were performed, during the same period - 70 in Belgium and about 15 at the Massachusetts Hospital; about 15 operations were performed annually in the UK.

In the USSR, lobotomy was officially banned in 1950. And this was not only an ideological underpinning. In the foreground were reasons of a purely scientific nature: the absence of a strictly substantiated theory of lobotomy; lack of strictly developed clinical indications for surgery; severe neurological and mental consequences of the operation, in particular "frontal defect".

“Lobotomy” with a bullet

More than 60 years have passed since the ban on lobotomy in our country. But people continue to get head injuries, get sick with various ailments (Peak's disease, for example), leading to a completely distinct "frontal" symptomatology. I will give a vivid observation of the consequences of the “frontal syndrome” from my own practice.

Two soldiers at the firing range, laughing, began pointing machine guns loaded with live ammunition at each other and shouting something like “Tra-ta-ta!..”. Suddenly he said his "word" and the machine gun ... The result - one had a bullet in the head. The neurosurgeons somehow managed to revive and repair the guy; they inserted several plates into his skull and sent him to us to resolve the issue of further treatment and disability.

During the conversation, the patient made a strange impression. Formally, his mind was not affected, his memory and stock of knowledge were at a normal level; he behaved quite adequately too — at first glance... An unnatural calmness, up to indifference, was striking; the guy indifferently talked about the injury, as if it did not happen to him; made no plans for the future. In the department he was absolutely passive, subordinating; for the most part, he lay on the bed. They invited me to play chess or backgammon, asked me to help the staff - I agreed. Sometimes it seemed - order him to jump out the window - he will do so, and without hesitation.

Sometimes it seemed - order him to jump out the window - he will do so, and without hesitation.

And we received an answer to our questions a week later, when the patient was “caught up” with documents from neurosurgery, where his injury was treated. The surgeons described that the wound channel passed right through the frontal lobes of the guy. After that, all questions about the patient's behavior were removed for us.

By the will of fate, I happened to meet this patient again, almost ten years after we met. It happened in a rehabilitation center where I worked as a consultant. The guy has changed little in appearance. In communication appeared sharpness, rudeness; mental faculties were completely preserved. I did not notice the main thing: self-confidence and independence. The man had empty eyes... In life, he "went with the flow", completely indifferent to what was happening around him.

In conclusion, as before, I would like to wish: take care of yourself and your loved ones and remember that in most cases even severe and painful treatment is worth defeating a disease that deprives a person of his human appearance.

10 facts about the terrible operation

History remembers many barbaric practices in medicine, but lobotomy is perhaps the most frightening. Today, this operation can only be seen in the cinema, but in the middle of the last century, you could well be forced to undergo a lobotomy for your wayward character.

Alisa Gorbunova

1. Lobotomy, or leucotomy is an operation in which one of the lobes of the brain is separated from the rest of the areas, or completely excised. It was believed that this practice could treat schizophrenia.

2. The method was developed by the Portuguese neurosurgeon Egas Moniz in 1935, and trial lobotomy took place in 1936 under his supervision. After the first hundred operations, Moniz observed the patients and made a subjective conclusion about the success of his development: the patients calmed down and became surprisingly submissive.

3. The results of the first 20 operations were as follows: 7 patients recovered, 7 patients showed improvement, and 6 people remained with the same illness. But the lobotomy continued to cause disapproval: many of Moniz's contemporaries wrote that the actual result of such an operation was the degradation of the personality.

4. The Nobel Committee considered the lobotomy a discovery ahead of its time. Egas Moniz received the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1949. Subsequently, the relatives of some patients requested that the award be canceled, since lobotomy causes irreparable harm to the patient's health and is generally a barbaric practice. But the request was rejected.

5. If Egas Moniz argued that leucotomy is a last resort, then Dr. Walter Freeman considered lobotomy a remedy for all problems, including willfulness and aggressive character. He believed that lobotomy eliminates the emotional component and thereby "improves the behavior" of patients. It was Freeman who coined the term "lobotomy" in 1945. Throughout his life, he operated on about 3,000 people . By the way, this doctor was not a surgeon.

It was Freeman who coined the term "lobotomy" in 1945. Throughout his life, he operated on about 3,000 people . By the way, this doctor was not a surgeon.

6. Freeman once used an ice pick from his kitchen for an operation. Such a "necessity" arose because the former instrument - the leukote - could not withstand the load and broke in the skull of patient .

7. Later, Freeman realized that ice pick was great for lobotomizing . Therefore, the doctor designed a new medical instrument based on this model. The orbitoclast had a pointed end on one side and a handle on the other. A division was applied to the tip to control the depth of penetration.

8. By the middle of the last century, lobotomy had become an incredibly popular procedure : it was practiced in Great Britain, Japan, the United States and many European countries. In the United States alone, about 5,000 operations were performed per year.