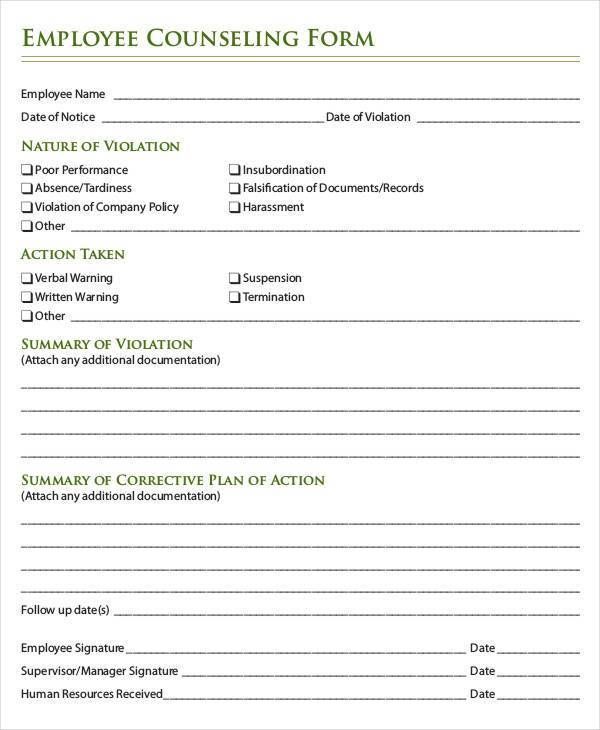

List of boundary violations in counseling

Boundaries and Multiple Relationships in Psychotherapy

The process of psychotherapy is relationship based. As such, how psychotherapists conduct themselves in these relationships has significant clinical and ethical implications. The Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (APA Ethics Code, APA, 2010) makes clear the ethical obligations relevant to boundaries and multiple relationships that are likely to be well known by psychotherapists (e.g., it is unethical to engage in sexual relations with your clients). Yet, the APA Ethics Code cannot provide strict rules to apply to every clinical situation that may arise in practice. Psychotherapists must apply their judgment in making decisions about the appropriateness of different actions and behaviors, hopefully utilizing the guidance provided by the Ethics Code, consultation with colleagues, and a decision-making process.

Boundaries in the Psychotherapy Relationship

In psychotherapy there is a need for rules and expectations to be discussed and agreed upon in order for the relationship to be acceptable and successful for all parties. Boundaries constitute the agreed upon rules and expectations that articulate the parameters of the relationship.

Boundaries provide:

- “A therapeutic frame which defines a set of roles for the participants in the therapeutic process” (Smith and Fitzpatrick, 1995, p. 499)

- “a foundation for this relationship by fostering a sense of safety and the belief that the clinician will always act in the client’s best interest (Smith & Fitzpatrick, 1995, p. 500)

- a “distinction between the expectations and interactions that would be considered appropriate within the relationship and those that would be considered inappropriate within the relationship” (R. Sommers-Flanagan, Elliot, & J. Sommers-Flanagn, 1998, p. 38).

Six of the most common boundaries within the psychotherapy relationship include:

- Touch

- Time

- Space

- Location

- Gifts

- Self-disclosure

How each of these is addressed and managed in the psychotherapy relationship holds great implications for the client’s welfare as well as for achieving desired therapeutic outcomes.

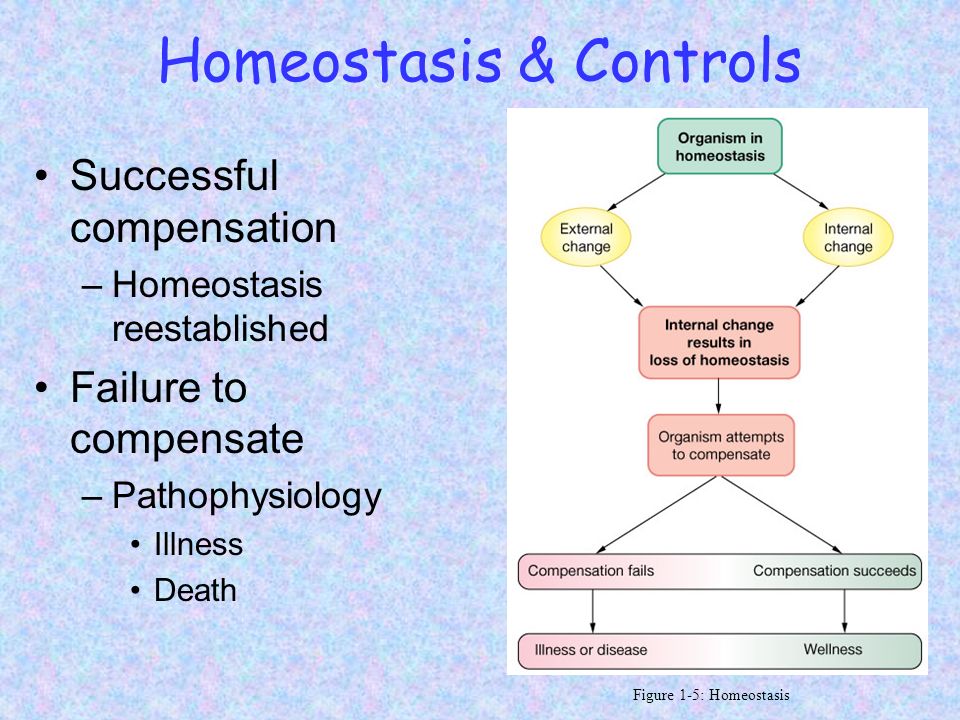

Managing Boundaries

Boundaries may be avoided, crossed, or violated. To avoid a boundary means that it is not traversed at all. For example, with regard to the boundary of touch, consider a psychotherapist treating a client who is a survivor of sexual assault or trauma. It may be inappropriate and unbeneficial for the psychotherapist to use touch with the client, and in fact may be harmful. Another example would be a male psychotherapist providing psychotherapy to a female Orthodox Jew for whom any touch by a man who is not her husband would be considered taboo.

Smith and Fitzpatrick (1995) defined boundary crossing as “a nonpejorative term that describes departures from commonly accepted clinical practice that may or may not benefit the client” (p. 500). Thus, traversing a boundary in a manner that is not harmful or exploitative to the client and that may in fact, be supportive of a strong therapeutic alliance and that may promote achieving treatment goals is considered a boundary crossing. Possible examples of boundary crossings include shaking a client’s extended hand upon first meeting or extending the time of a treatment session for a client who is in crisis.

Possible examples of boundary crossings include shaking a client’s extended hand upon first meeting or extending the time of a treatment session for a client who is in crisis.

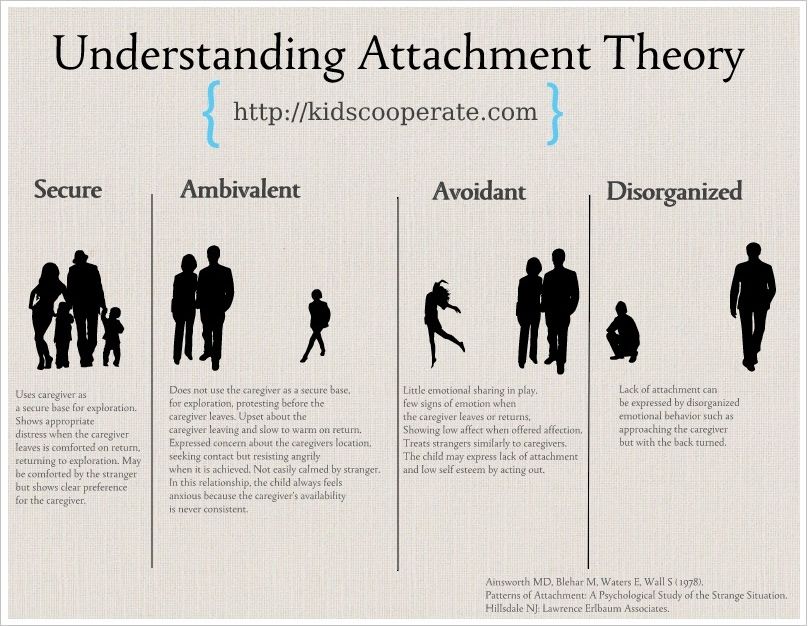

In contrast, a boundary violation is “a departure from accepted practice that places the client or the therapeutic process at serious risk” (Smith & Fitzpatrick, 1995, p. 500). Boundary violations are likely to be harmful, exploitative, and not in the client’s best interest. Additionally, boundary violations are likely to take advantage of the client’s dependence and trust, and often are confusing to clients and inconsistent with their treatment needs. Examples of boundary violations include engaging in sexually intimate behaviors with a client and a psychotherapist disclosing her or his personal issues and life challenges with a client in an effort to receive emotional support from the client.

Boundary Decision-Making

As was previously stated, boundaries should not always be avoided. In fact, a strict application of boundaries with clients may prove to be clinically ineffective and may create a cold or sterile environment that is contrary to the goals of a good working alliance (Zur & Lazarus, 2002). Flexibility with boundaries is recommended so that each client’s unique needs are met in the most appropriate manner possible.

In fact, a strict application of boundaries with clients may prove to be clinically ineffective and may create a cold or sterile environment that is contrary to the goals of a good working alliance (Zur & Lazarus, 2002). Flexibility with boundaries is recommended so that each client’s unique needs are met in the most appropriate manner possible.

It is likely that most psychotherapists are clear on those behaviors that are clearly ethical and those behaviors that are clearly unethical. It is the gray areas where there is no apparent right or wrong answer will likely prove most challenging to psychotherapists in determining the most appropriate course of action. When faced with these situations psychotherapists may benefit from engaging in a thoughtful decision-making process when deciding on the appropriateness of certain behaviors and in determining if a proposed action constitutes a boundary crossing or a boundary violation (Pope & Keith-Spiegel, 2008).

There are a number of factors that should be considered when engaging in a thoughtful decision-making process about boundaries.

These include:

- What are the motivations for taking the proposed action? Are they to meet the psychotherapist’s needs in some way or are they motivated by the client’s best interest?

- What is the likely effect or impact of the proposed action? Will it be of therapeutic value to the client or is it likely to be exploitative or harmful?

- Will the proposed action be welcomed by the client or viewed negatively? If this is not imminently clear, have you openly discussed the proposed action with the client to seek her or his input?

- Is the action under consideration consistent with widely accepted roles of psychotherapists and will taking this action risk jeopardizing the client’s, and the public’s, trust in the profession?

- Will the action under consideration promote the client’s autonomous functioning over time or is it more likely to create more dependence on the psychotherapist?

- Is the proposed action consistent with the agreed upon treatment plan and consistent with the client’s treatment goals?

- Are there any cultural factors or expectations, or other individual differences, that would impact the client’s needs and how the client might interpret or be impacted by the proposed action?

- Is the action under consideration consistent with your theoretical orientation?

- If unsure of any of the above, have you consulted with a colleague to receive input and feedback on your proposed course of action prior to taking it?

- Have you documented your decision-making process, the rationale for the decision you have made, and the impact of your action on the client?

As can be seen, there are a number of considerations that may be relevant for determining if a particular action or behavior would be considered a potentially helpful boundary crossing or a harmful boundary violation. Thus, a thoughtful decision-making process, at a minimum includes considerations of these questions, should occur in order to help ensure that the therapeutic relationship is preserved and that the client’s best interest is served.

Thus, a thoughtful decision-making process, at a minimum includes considerations of these questions, should occur in order to help ensure that the therapeutic relationship is preserved and that the client’s best interest is served.

Multiple Relationships

To engage in a multiple relationship is to enter into a secondary relationship in addition to the primary psychotherapy relationship. Multiple relationships may be social, business or financial, or sexual in nature. The APA Ethics Code (APA, 2010) makes it very clear that all multiple relationships need not be avoided; only those that hold a significant potential for exploitation of, or harm to, the client, and those that are likely to lead to impaired objectivity and judgment for the psychotherapist, must be avoided. Of course, knowing this in advance may prove challenging. Thus, the use of a decision-making process and consultation with colleagues is recommended when the outcome and effects of an anticipated multiple relationship is unclear.

In addition to considering the questions listed above prior to entering into a multiple relationship with a client or other individuals associated with the client, there are ethical decision-making models that may prove helpful for making these decisions. Younggren and Gottlieb (2004) suggest that the psychotherapist consider the following questions when contemplating entering into a multiple relationship with a client:

- Is entering into a relationship in addition to the professional relationship necessary, or should I avoid it?

- Can the [multiple] relationship potentially cause harm to the patient?

- If harm seems unlikely or unavoidable, would the additional relationship prove beneficial?

- Is there a risk that the [multiple] relationship could disrupt the therapeutic relationship?

- Can I evaluate this matter objectively? (pp. 256-257)

In many settings the complete avoidance of multiple relationships may prove impossible. These may include being a member of a community who both lives and works in that community such as in a rural setting; a small or isolated community; a religious, ethnic, or LGBT community; and others. Often, it is because the psychotherapist has been active in the community and known to its members in a variety of roles, that the community members feel comfortable in seeking professional services from the psychotherapist. In addition, in these settings, options for making referrals to other clinicians may be quite limited, further impacting decisions about providing psychotherapy to individuals with whom the psychotherapist has pre-existing relationships (Hargrove, 1986).

Often, it is because the psychotherapist has been active in the community and known to its members in a variety of roles, that the community members feel comfortable in seeking professional services from the psychotherapist. In addition, in these settings, options for making referrals to other clinicians may be quite limited, further impacting decisions about providing psychotherapy to individuals with whom the psychotherapist has pre-existing relationships (Hargrove, 1986).

In these settings the question is not “should I participate in multiple relationships?”, but “how should I best participate in multiple relationships so that my clients’ best interests are served?”. Curtin and Hargrove (2010) share the following representative example of life as a psychotherapist in a rural community: “my son’s third-grade teacher (a former client before I had children) also serves on the library board with my spouse and is a member of the Sunday school class that we attend. She shops at the same drug store and local discount house and eats at the same restaurants” (p. 550). But, as has been emphasized, not all multiple relationships are appropriate, and even in these settings, some multiple relationships will need to be avoided. How one makes these decisions, the factors one considers, when engaging in necessary multiple relationships is okay, and how they are managed is key.

550). But, as has been emphasized, not all multiple relationships are appropriate, and even in these settings, some multiple relationships will need to be avoided. How one makes these decisions, the factors one considers, when engaging in necessary multiple relationships is okay, and how they are managed is key.

Important Considerations

In keeping with the information shared above, it is important to take a flexible approach to boundaries and multiple relationships that takes into consideration the many factors addressed above. Our clients’ best interest and the promotion of their treatment goals should always guide us. Further, it is important to consider the guidance provided by the APA Ethics Code (APA, 2010), to access the wisdom of colleagues when faced with dilemmas and unclear situations, and to utilize a decision-making process to assist us in making these decisions.

+42

-3

Boundaries, inside and outside the therapy room

Do you greet your clients with a casual wave and “hey” or a firm handshake, or do they sometimes get a hug? Do you discuss what the client should expect if you bump into each other in public? And in what situations are you made most aware of the therapeutic boundaries, whether inside or outside your practice?

Therapeutic boundaries relate to many things, from the therapist’s self-disclosure, touch, and exchange of gifts to bartering and fees, length and location of sessions and contact outside the office. Issues with boundaries can come up in the therapy room, or appear outside of the sessions. For instance, a client might ask you to reveal personal information about your life (Do you have children?) or you might live in the same neighborhood and have to deal with encounters on the streets. These types of situations might shed some light on the complexity of boundaries, and make you think about when boundary crossings are beneficial and when they can turn into harmful violations.

Issues with boundaries can come up in the therapy room, or appear outside of the sessions. For instance, a client might ask you to reveal personal information about your life (Do you have children?) or you might live in the same neighborhood and have to deal with encounters on the streets. These types of situations might shed some light on the complexity of boundaries, and make you think about when boundary crossings are beneficial and when they can turn into harmful violations.

A boundary violation happens when a therapist crosses the line of decency and integrity and misuses his/her power to exploit a client for the therapist’s own benefit. Boundary violations usually involve exploitive business or sexual relationships. They are always unethical and often illegal. But harmful boundary violations are different from boundary crossings, and, when appropriately employed, the latter can increase clinical effectiveness and therapeutic outcome (Zur, 2018).

Helpful boundary crossings

From a psychoanalytical point of view almost all boundary crossings are detrimental to the transference and the clinical work. The perspective of the depravity of boundary crossings communicates that crossing boundaries is likely to lead us down the slippery slope to exploitative sexual relationships. The message is that we should never leave the office with a client, be very careful about gifts, never socialize with clients and limit physical contact to a handshake.

The perspective of the depravity of boundary crossings communicates that crossing boundaries is likely to lead us down the slippery slope to exploitative sexual relationships. The message is that we should never leave the office with a client, be very careful about gifts, never socialize with clients and limit physical contact to a handshake.

But particularly behavioral, humanistic, existential, group, feminist, Ericksonian and family therapies often support many forms of helpful boundary crossings, with the belief that boundary crossing, when executed with the clients’ welfare in mind, is likely to enhance therapeutic alliance — the best predictor of therapeutic outcome.

A few examples of beneficial boundary crossings could include walking with an agoraphobic client to an open space outside the office (common in CBT), self-disclosure as a way of offering an alternative perspective, exemplifying cognitive flexibility, creating an authentic connection, increase therapeutic alliance or leveling the playing field, or take a depressed client on a vigorous walk (Zur, 2018).

Dual Relationships

Dual relationships are also referred to as multiple relationships, and occurs whenever multiple roles exist between a therapist and a client. Dual relationships are subtypes of boundary crossing, and aren’t in all cases unethical. For instance, therapists practicing in small communities will regularly encounter unavoidable dual relationships, e.g. the person who pumps gas might also be their client. Such unavoidable dual relationships can also happen in small, distinct populations in larger metropolitan areas, e.g. LGBTQIA, handicapped, various minorities, religious congregations, and other distinct small societies. In these communities, the duality and prior knowledge of each other are arguably preconditions for the development of trust and respect, and so, non-sexual, non-exploitative dual relationships and familiarity between therapists and clients are not only normal but can, in fact, increase trust (Zur, 2018).

While dual relationships may be sometimes unavoidable, therapists have to pay close attention to the harm that can arise from them, especially where there is a conflict of interest. Conflicts of interest are often present in situations where the client is also a student, employee, employer or business partner. Of course, sexual dual relationships are always unethical, counter-clinical and illegal in most (if not all?) countries.

Conflicts of interest are often present in situations where the client is also a student, employee, employer or business partner. Of course, sexual dual relationships are always unethical, counter-clinical and illegal in most (if not all?) countries.

The Ethics of Boundaries and the Standard of Care

Interestingly, there are no clear guidelines that specifically deal with boundary crossings. The APA’s and almost all other professional organizations’ codes of ethics do not regulate non-sexual touch, gifts, length of sessions or self-disclosure. Of course, they all have a mandate to avoid harm and exploitation and respect clients’ integrity and autonomy and say things like: “Multiple relationships that would not reasonably be expected to cause impairment or risk exploitation or harm are not unethical” (APA, 2016, section 3.05).

The standard of care is defined as qualities and conditions that should prevail in a particular mental health service. The requirements of the standard are closely dependent on circumstances, and is closely tied to a theoretical orientation. The examples of boundary crossings mentioned above clearly fall within the standard of care of behavioral, humanistic, family, and other non-analytic therapies. However, boards, courts and ethics committees too often confuse the standard of care with analytic standards or with risk management guidelines. This confusion has caused injustice to therapists, when boards’ and courts’ experts apply an analytic criterion and proclaim clinically appropriate boundary crossings and dual relationships to be below the standard of care.

The examples of boundary crossings mentioned above clearly fall within the standard of care of behavioral, humanistic, family, and other non-analytic therapies. However, boards, courts and ethics committees too often confuse the standard of care with analytic standards or with risk management guidelines. This confusion has caused injustice to therapists, when boards’ and courts’ experts apply an analytic criterion and proclaim clinically appropriate boundary crossings and dual relationships to be below the standard of care.

Of course, intentional boundary crossings should be implemented with two things in mind: the welfare of the client and therapeutic effectiveness. Boundary crossing, like any other intervention, should be part of a well-constructed treatment plan which takes into consideration the client’s problem, personality, situation, history, culture, etc. and the therapeutic setting and context. Boundary crossings with certain clients, such as those with Borderline Personality Disorders or those who are acutely paranoid are not usually recommended, since effective therapy with such clients often requires well-defined boundaries of time and space. Dual relationships, since they always entail boundary crossing, impose the same criteria on the therapist. Even when such relationships are unplanned and unavoidable, the welfare of the client and clinical effectiveness should always be the main concern (Zur, 2018).

Dual relationships, since they always entail boundary crossing, impose the same criteria on the therapist. Even when such relationships are unplanned and unavoidable, the welfare of the client and clinical effectiveness should always be the main concern (Zur, 2018).

Reference: Zur, O. To Cross or Not to Cross: Do boundaries in therapy protect or harm. Psychotherapy Bulletin, 39 (3), 27–32. Posted by permission of Division 29 (psychotherapy) of APA (updated 2018).

Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy - Teachers of the Department - Yuri Viktorovich Zaretsky

Associate Professor of the Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy of the Faculty of Counseling and Clinical Psychology

Academic degree: "The subjective position of schoolchildren in relation to learning activities in different age periods" was defended at MSUPE in 2014)

Education level: Higher, MGPPU, Faculty of Psychological Consulting, Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy (2008)

Name of the direction of preparation and (or) Specialty: Psychology

Psychologist

data on advanced training and (or) professional retraining:

- 2010, advanced training under the program "Integrative Psychotherapy of Affective Spectrum Disorders" at MSUPE - 72 hours

- 2011, correspondence (on-line) training under the program of the Oxford Center for Cognitive Therapy (modules: Basic CBT Theory; Assessment and Formulation; Collaborative Working; Socratic Method and CBT for Panic Disorder and OCD) - 72 hours

- 2018, NIGHT DPO "Institute of Practical Psychology and Psychoanalysis".

Transference-Focused Psychotherapy in the Treatment of Borderline Disorders - 72 hours

Transference-Focused Psychotherapy in the Treatment of Borderline Disorders - 72 hours - 2020, First aid in educational institutions (4 p.m., Helmets LLC, St. Petersburg)

Total work experience: Since 2006

SCIDAGOGIC ACTIVITIONS: Since 2007

Sphere of Scientific interests:

- Subject position in relation to educational activities as a development resource

- problems of development of children in the conditions of the boarding system of education

- emotional disorders in adolescence and adolescence

reading disciplines

- Psychological assistance to a family with a problem child (specialty)

- Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy (master's degree)

- Supervision (specialty)

- Educational and fact-finding practice (specialty)

- Supervision of term papers and theses (specialty)

main publications:

articles in publications recommended by the Higher Attestation Commission of the Russian Federation:

- Zaretsky, Yu.

V. The subjective position of the child in overcoming educational difficulties (a case from practice) [Text] / V.K. Zaretsky, Yu.V. Zaretsky // Counseling psychology and psychotherapy. - 2012. - No. 2. - C. 110-133

V. The subjective position of the child in overcoming educational difficulties (a case from practice) [Text] / V.K. Zaretsky, Yu.V. Zaretsky // Counseling psychology and psychotherapy. - 2012. - No. 2. - C. 110-133 - Zaretsky, Yu.V. Subjective position in relation to educational activity as a resource of development and a subject of research [Text] / Yu.V. Zaretsky // Counseling psychology and psychotherapy. - 2013. - No. 2. - C. 110-128

- Zaretsky, Yu.V. Methods of studying the subjective position of students of different ages [Text] / Yu.V. Zaretsky, V.K. Zaretsky, I.Yu. Kulagina // Psychological science and education. - 2014. - No. 1. - P. 99-110.

- Zaretsky V.K., Zaretsky Yu.V. The experience of providing psychological and pedagogical assistance by means of a reflexive-activity approach: the case of Denis G. // Consultative Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2015. Volume 23. No. 2. S. 142–156. doi:10.17759/cpp.2015230209

monographs:

- Zaretsky, Yu.

V. Three main problems of a teenager with deviant behavior: Why do they arise? How to help? [Text] / V.K. Zaretsky, N.S. Smirnova, Yu.V. Zaretsky, N.M. Evlashkina, A.B. Kholmogorova // Three main problems of a teenager with deviant behavior: Why do they arise? How to help?. - M.: Forum, 2011. - 208 p.

V. Three main problems of a teenager with deviant behavior: Why do they arise? How to help? [Text] / V.K. Zaretsky, N.S. Smirnova, Yu.V. Zaretsky, N.M. Evlashkina, A.B. Kholmogorova // Three main problems of a teenager with deviant behavior: Why do they arise? How to help?. - M.: Forum, 2011. - 208 p.

articles in conference proceedings:

- Zaretsky, Yu.V. Help in overcoming educational difficulties in adolescents with deviant behavior [Text] / Yu.V. Zaretsky // Proceedings of the IV International Conference of defectologists "Actual aspects of the convergence of educational institutions and families in the upbringing of children with health problems." - M., 2009. - S.38-39.

- Zaretsky, Yu.V. Psychological and pedagogical counseling of adolescents with deviant behavior to overcome educational difficulties within the framework of a reflexive-activity approach [Text] / Yu.V. Zaretsky // Proceedings of the V International Conference of defectologists "Creating a rehabilitation educational environment for children and adolescents with deviant behavior.

" - M., 2010. - P.144-145.

" - M., 2010. - P.144-145. - Zaretsky Yu.V., Lotareva T.Yu. Support technology for foster families in the Nash Dom State Budgetary Institution of Healthcare Centers as a Condition for Successful Socialization of an Adopted Child // Human Mental Health of the 21st Century Collection of scientific articles based on the materials of the Congress. 2016. S. 46-49.

publications on PsyJournlas

publications in the RSCI

address: Moscow, st. Sretenka, 29, room. 307 (department)

work schedule: classes according to the schedule

| Phone: | +7 (495) 632-92-12 |

| Email: | kafedra-kp@yandex. ru ru |

Applicants - South Ural State University

The department trains specialists in the specialty 37.05.01 "Clinical Psychology"

What is clinical psychology?

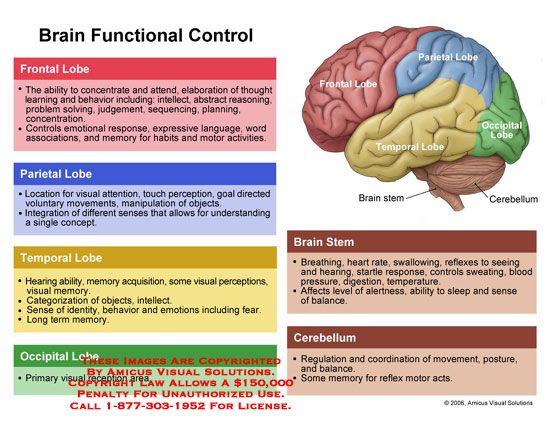

Clinical psychology is the branch of psychology that is closest to medicine. Therefore, a clinical psychologist is the closest colleague of a doctor and helps him in working with people who have not only mental, but also bodily illnesses. In addition, a clinical psychologist has knowledge of human development disorders, from infancy to old age. At the same time, he can work with a wide range of problems: psychological support for pregnant women, patients with neurotic disorders and people who find themselves in a difficult life situation, speech disorders and other mental functions after strokes. One of the areas of work is forensic psychological examination in criminal and civil proceedings.

For his successful work, a clinical psychologist must understand Latin terminology, master various forms and methods of non-medical psychotherapy, know many psychodiagnostic methods and be able to “read” a Person like a book with their help.

Recently, knowledge of clinical psychology has become necessary for working in educational institutions (especially in schools for children with disabilities and special abilities), as well as in helping gifted and developed children.

What do future clinical psychologists study?

Future clinical psychologists study all the same disciplines as other psychologists: general psychology, animal psychology, history of psychology, personality psychology, social psychology, educational psychology, etc. But a large amount of training is made up of special clinical and psychological disciplines. This special knowledge is grouped into five sections.

Pathopsychology studies methods and techniques for diagnosing and correcting various mental disorders in a psychiatric clinic, is the basis of forensic psychological examination.

Neuropsychology studies disorders caused by diseases and developmental disorders of the brain in adults and children, as well as special techniques for helping such patients.

Psychosomatics studies the psychological nature of human bodily diseases, the internal picture of the disease and the reaction of the individual to the disease, the psychology of the behavior of a healthy and sick person.

Non-medical psychotherapy and psychological correction – a group of methods for influencing the personality and behavior of healthy and sick people, used for neurotic and borderline disorders. The psychological model of psychotherapy excludes the use of medications, but is no less effective.

Psychology of abnormal development studies childhood mental disorders and various methods of working with problem children.

In addition, future clinical psychologists study the basics of medical knowledge in psychiatry, neurology and internal medicine, and psychopharmacotherapy.

Separate special courses are devoted to the study of stress, neurosis, human sexuality and other topical issues. These areas are complemented by independent work of students on many other interesting problems.

These areas are complemented by independent work of students on many other interesting problems.

A large place in the training of clinical psychologists is occupied by workshops that are held in medical institutions in the city of Chelyabinsk. At these workshops, students work with adults and children, patients of various hospitals, conduct psychodiagnostics, provide advice together with doctors and practicing psychologists, and learn other practical skills necessary for their professional growth.

Who will be the graduate with the specialty "Clinical Psychology"?

The future of a clinical psychologist is described by an informal slogan: “Among psychologists we are doctors, among doctors we are psychologists”.

You can learn about the life of the department on the website http://www.klynepsy.susu.ru/

What do you need to do to join us?

-

Finish school and pass the USE well in mathematics, Russian language and biology.

-

Gather the required documents (application; proof of previous education; 6 photos 3x4 cm; documents entitling to benefits (if any)).