Is there a correlation between intelligence and depression

High Intelligence Disorders | Origins Behavioral Healthcare

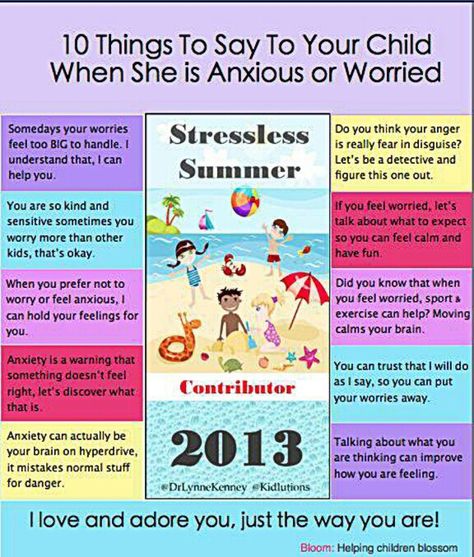

Higher intelligencehas many advantages. Higher IQ is associated with better grades, better jobs, higher pay, and even longer life. However, intelligence has drawbacks too. For example, studies have found that higher IQ is associated with more and earlier drug use. Studies have also found that higher IQ is associated with more mental illness, including depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.

One large study led by Ruth Karpinski of Pitzer College surveyed more than 3,700 members of Mensa, a society whose members must have an IQ in the top two percent, which is typically about 132 or higher. The team asked about many factors, including mental health. They discovered that mood disorders and anxiety disorders were extremely common among Mensa members.

Among the general population, about 10 percent of people have mood disorders and about 10 percent of people have some anxiety disorder, with some degree of overlap between the two. Among Mensa members, those percentages were much higher.

About 20 percent reported having been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and nearly 27 percent had been diagnosed with a mood disorder such as major depression or bipolar disorder. [See ‘High intelligence: A risk factor for psychological and physiological overexcitabilities for more details about the study.]

The Possible Cause: Psychological Overexcitability

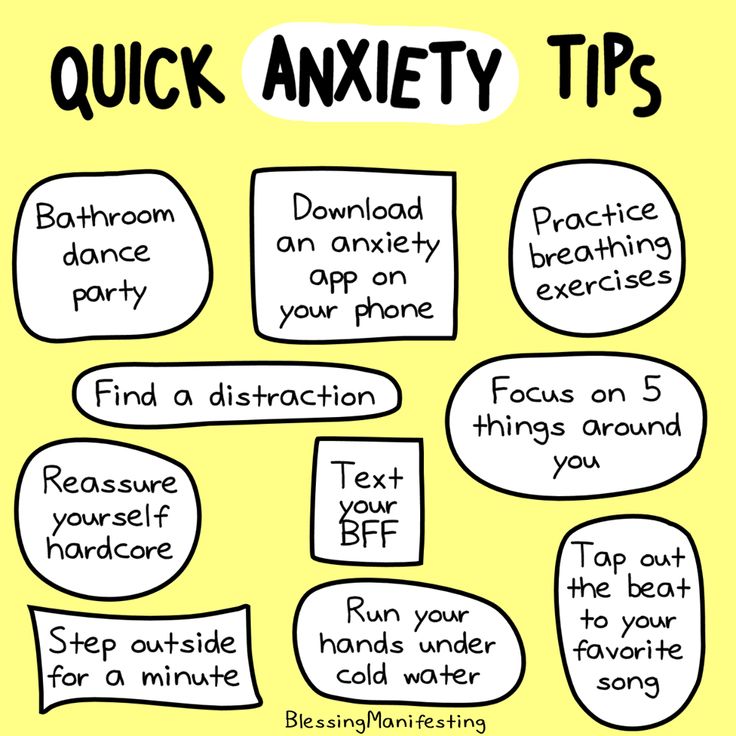

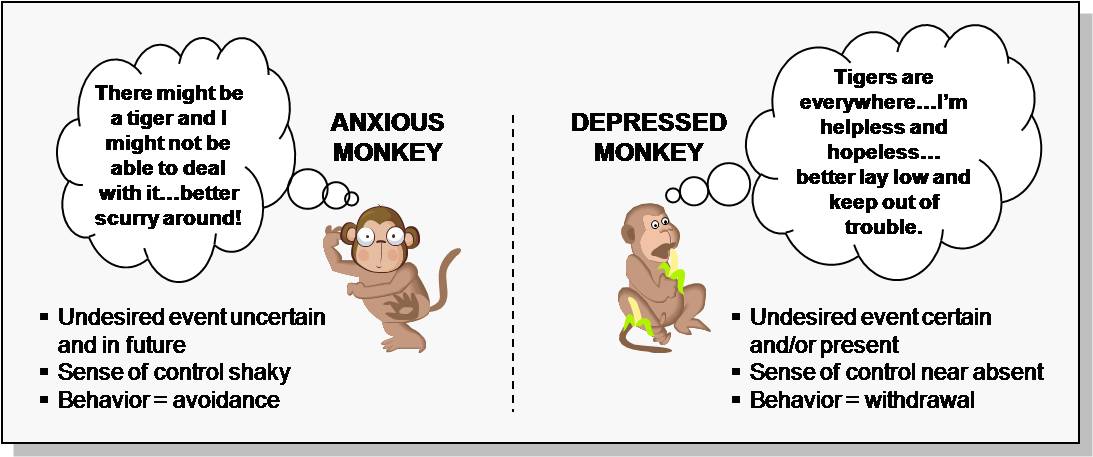

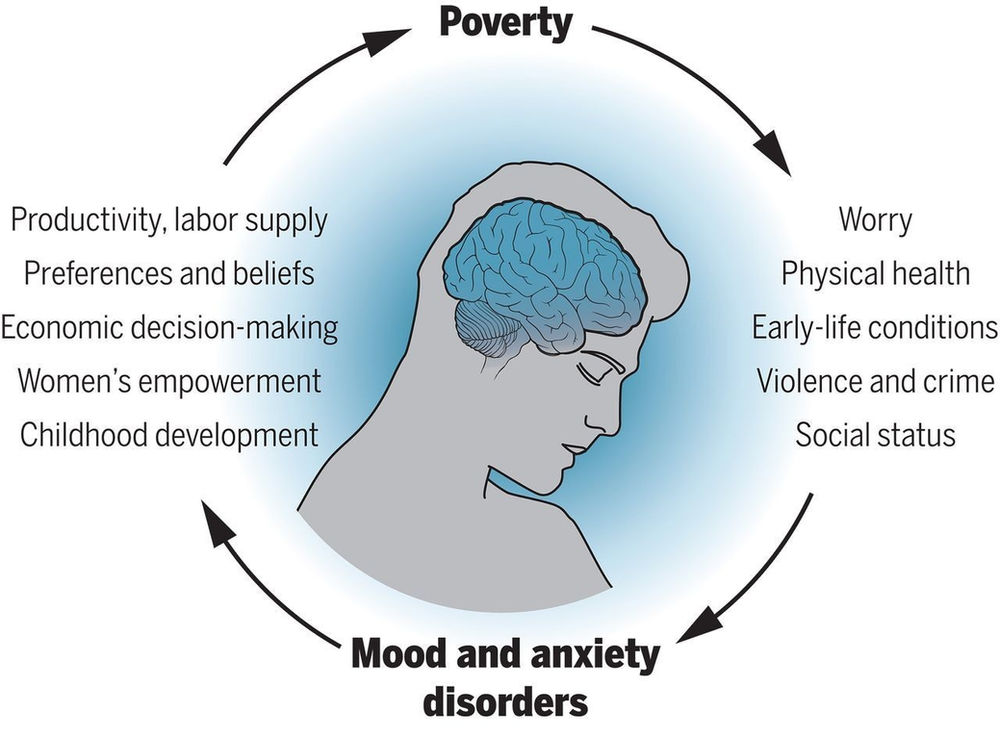

Karpinski and her team suspect the reason for this high rate of mental illness among Mensa members has to do with psychological overexcitability. Psychological overexcitability includes a greater tendency to ruminate and worry, both of which are common features of mood and anxiety disorders. For example, a very intelligent person may obsessively overanalyze a critical comment from her boss, trying to anticipate the possible consequences it might foretell.

While this is an asset when used to plan complex projects or acquire subject matter expertise, when the same tendency is turned toward worry and rumination, the psychological effects can be disastrous. The team also found that Mensa members are physically overexcitable, as indicated by a very high rate of allergies, and this physical overexcitability may play a role in aggravating worry and rumination.

The team also found that Mensa members are physically overexcitable, as indicated by a very high rate of allergies, and this physical overexcitability may play a role in aggravating worry and rumination.

There may, in fact, be many different explanations for this phenomenon in addition to the overexcitability hypothesis, and they may all be relevant to some degree. One possibility is that the genes associated with intelligence also make you more prone to mental illness, but intelligence doesn’t directly increase your risk of mental illness. Another possibility is that people with higher IQs are often more socially isolated, which leads to more anxiety and depression.

For example, people with autism spectrum disorders and above-average IQ are at much higher risk for depression. That may also happen to a lesser extent with intelligent people not on the spectrum.

Another possibility is that more intelligent people are more likely to be diagnosed than people of average or below-average intelligence. People who are educated, health-conscious, and generally well-informed are more likely to seek help for mental illness and less likely to be dissuaded by perceived stigma. In other words, part of that higher rate might simply reflect more awareness of mental health and greater access to mental health care.

People who are educated, health-conscious, and generally well-informed are more likely to seek help for mental illness and less likely to be dissuaded by perceived stigma. In other words, part of that higher rate might simply reflect more awareness of mental health and greater access to mental health care.

Origins Treat a Wide Range of Mental Health Problems

Origins Behavioral Healthcare is a well-known care provider offering a range of treatment programs targeting the recovery from substance abuse, mental health issues, and beyond. Our primary mission is to provide a clear path to a life of healing and restoration. We offer renowned clinical care for addiction and have the compassion and professional expertise to guide you toward lasting sobriety.

For information on our programs, call us today: 561-841-1296.

Intelligence and neuroticism in relation to depression and psychological distress: Evidence from two large population cohorts

1. Ferrari A.J., Charlson F.J., Norman R.E., Patten S.B., Freedman G., Murray C.J. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ferrari A.J., Charlson F.J., Norman R.E., Patten S.B., Freedman G., Murray C.J. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Kendler K.S., Neale M.C., Kessler R.C., Heath A.C., Eaves L.J. A longitudinal twin study of personality and major depression in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(11):853–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Jardine R., Martin N.G., Henderson A.S. Genetic covariation between neuroticism and the symptoms of anxiety and depression. Genet Epidemiol. 1984;1(2):89–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Matthews G., Deary I., Whiteman M. 3rd ed. Cambridge Univeristy Press; Cambridge: 2009. Personality traits. [Google Scholar]

5. Jylhä P., Isometsä E. The relationship of neuroticism and extraversion to symptoms of anxiety and depression in the general population. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23(5):281–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Chan S.W., Goodwin G.M., Harmer C.J. Highly neurotic never-depressed students have negative biases in information processing. Psychol Med. 2007;37(9):1281–1291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chan S.W., Goodwin G.M., Harmer C.J. Highly neurotic never-depressed students have negative biases in information processing. Psychol Med. 2007;37(9):1281–1291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Muris P., Roelofs J., Rassin E., Franken I., Mayer B. Mediating effects of rumination and worry on the links between neuroticism, anxiety and depression. Pers Individual Differrences. 2005;39(6):1105–1111. [Google Scholar]

8. Roelofs J., Huibers M., Peeters F., Arntz A., van Os J. Rumination and worrying as possible mediators in the relation between neuroticism and symptoms of depression and anxiety in clinically depressed individuals. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(12):1283–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Farmer A., Korszun A., Owen M.J., Craddock N., Jones L., Jones I. Medical disorders in people with recurrent depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(5):351–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Hirschfeld R.M., Klerman G.L., Lavori P., Keller M.B., Griffith P., Coryell W. Premorbid personality assessments of first onset of major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(4):345–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(4):345–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Kendler K.S., Gatz M., Gardner C.O., Pedersen N.L. Personality and major depression: a Swedish longitudinal, population-based twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(10):1113–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Fanous A.H., Neale M.C., Aggen S.H., Kendler K.S. A longitudinal study of personality and major depression in a population-based sample of male twins. Psychol Med. 2007;37(8):1163–1172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Schmutte P.S., Ryff C.D. Personality and well-being: reexamining methods and meanings. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(3):549–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Spijker J., de Graaf R., Oldehinkel A.J., Nolen W.A., Ormel J. Are the vulnerability effects of personality and psychosocial functioning on depression accounted for by subthreshold symptoms? Depress Anxiety. 2007;24(7):472–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Fergusson D.M., Horwood L.J., Lawton J.M. The relationships between neuroticism and depressive symptoms. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1989;24(6):275–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1989;24(6):275–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Kendler K.S., Kuhn J., Prescott C.A. The interrelationship of neuroticism, sex, and stressful life events in the prediction of episodes of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):631–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Neeleman J., Ormel J., Bijl R.V. The distribution of psychiatric and somatic III health: associations with personality and socioeconomic status. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(2):239–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Lahey B.B. The public health significance of neuroticism. Am Psychol. 2009;64(4):241–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Hardeveld F., Spijker J., De Graaf R., Nolen W.A., Beekman A.T. Recurrence of major depressive disorder and its predictors in the general population: results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS) Psychol Med. 2013;43(1):39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Conley J.J. Longitudinal stability of personality traits: a multitrait-multimethod-multioccasion analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;49(5):1266–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;49(5):1266–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Humphreys L. The construct of general intellience. Intelligence. 1979:105–120. [Google Scholar]

22. Wraw C., Deary I.J., Gale C.R., Der G. Intelligence in youth and health at age 50. Intelligence. 2015;53:23–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Deary I.J., Weiss A., Batty G.D. Intelligence and personality as predictors of illness and death: how researchers in differential psychology and chronic disease epidemiology are collaborating to understand and address health inequalities. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2010;11(2):53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Calvin C.M., Deary I.J., Fenton C., Roberts B.A., Der G., Leckenby N. Intelligence in youth and all-cause-mortality: systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(3):626–644. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Gale C.R., Deary I.J., Boyle S.H., Barefoot J., Mortensen L.H., Batty G.D. Cognitive ability in early adulthood and risk of 5 specific psychiatric disorders in middle age: the Vietnam experience study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1410–1418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1410–1418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Marazziti D., Consoli G., Picchetti M., Carlini M., Faravelli L. Cognitive impairment in major depression. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;626(1):83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Sackeim H., Steif B. The neuropsychology of depression and mania. In: Georgotas A., Cancro R., editors. Depression and mania. Elsevier; New York: 1988. pp. 265–289. [Google Scholar]

28. Gale C., Hatch S., Batty G., Deary I. Intelligence in childhood and risk of psychological distress in adulthood: the 1958 National Child Development Survey and the 1970 British Cohort Study. Intelligence. 2009:92–99. [Google Scholar]

29. Gale C.R., Batty G.D., Tynelius P., Deary I.J., Rasmussen F. Intelligence in early adulthood and subsequent hospitalization for mental disorders. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):70–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Maccabe J.H. Population-based cohort studies on premorbid cognitive function in schizophrenia. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Zammit S., Allebeck P., David A.S., Dalman C., Hemmingsson T., Lundberg I. A longitudinal study of premorbid IQ Score and risk of developing schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression, and other non-affective psychoses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(4):354–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Beck A., Rush A., Shaw B. Guilford press; New York: 1979. Cognitive therapy of depression. [Google Scholar]

33. Snaith R.P. The concepts of mild depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:387–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Goldberg D.P., Bridges K., Duncan-Jones P., Grayson D. Dimensions of neuroses seen in primary-care settings. Psychol Med. 1987;17(2):461–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Kessler R.C., Wang P.S. The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:115–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Singleton N., Bumpstead R. , O’Brien M., Lee A., Meltzer H. Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households, 2000. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2003;15(1–2):65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, O’Brien M., Lee A., Meltzer H. Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households, 2000. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2003;15(1–2):65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Goldberg D., Hillier V. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Kroencke K., Spitzer R., Williams J. The phq-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001:606–613. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Ormel J., Wohlfarth T. How neuroticism, long-term difficulties, and life situation change influence psychological distress: a longitudinal model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60(5):744–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Hatch S.L., Jones P.B., Kuh D., Hardy R., Wadsworth M.E., Richards M. Childhood cognitive ability and adult mental health in the British 1946 birth cohort. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(11):2285–2296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Gulliver A., Griffiths K.M. , Christensen H., Brewer J.L. A systematic review of help-seeking interventions for depression, anxiety and general psychological distress. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, Christensen H., Brewer J.L. A systematic review of help-seeking interventions for depression, anxiety and general psychological distress. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Weiss A., Gale C., Batty D., Deary I. Emotionally stable, intelligent men live longer: the Vietnam Experience Study Cohort. Psychosom Med. 2009:385–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Leikas S., Mäkinen S., Lönnqvist J.E., Verkasalo M. Cognitive ability × emotional stability interactions on adjustment. Eur J Pers. 2009:329–342. [Google Scholar]

44. Smith B.H., Campbell A., Linksted P., Fitzpatrick B., Jackson C., Kerr S.M. Cohort profile: Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study (GS:SFHS). The study, its participants and their potential for genetic research on health and illness. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(3):689–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Smith B.H., Campbell H., Blackwood D., Connell J., Connor M., Deary I.J. Generation Scotland: the Scottish Family Health Study; a new resource for researching genes and heritability. BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Allen N., Sudlow C., Downey P., Peakman T., Danesh J., Elliot P. UK Biobank: current status and what it means for epidemiology. Health Policy Technol. 2012:123–126. [Google Scholar]

47. Sudlow C., Gallacher J., Allen N., Beral V., Burton P., Danesh J. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12(3):e1001779. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. First M., Spitzer R., Gibbon M., Williams J. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; Washington, DC, USA: 1997. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-CV) [Google Scholar]

49. Wechsler D. Williams & Wilkens; Baltimore, Md: 1958. The measurement and appraisal of adult intelligence. [Google Scholar]

50. Wechsler D. A standardized memory scale for clinical use. J Psychol. 1945:87–95. [Google Scholar]

51. Raven J. H.K. Lewis & Co; Oxford, England: 1958. Guide to using the Mill Hill Vocabulary Scale with the Progressive Matrices Scales. [Google Scholar]

Raven J. H.K. Lewis & Co; Oxford, England: 1958. Guide to using the Mill Hill Vocabulary Scale with the Progressive Matrices Scales. [Google Scholar]

52. Marioni R., Batty G., Hayward C., Kerr S., Campbell A., Hockling L. Common genetic variants explain the majority of the correlation between height and intelligence: the Generation Scotland Study. Behav Genet. 2014:91–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Eysenck H. Dimensions of personality: 16, 5 or 3 criteria for a taxonomic paradigm. Pers Individual Differ. 1991:773–790. [Google Scholar]

54. Gow A., Whiteman M., Pattie A., Deary I. Goldberg's ‘IPIP’ Big-Five factor markers: internal consistency and concurrent validation in Scotland. Pers Individual Differ. 2005:317–329. [Google Scholar]

55. Eysenck S., Eysenck H., Barrett P. A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Pers Individual Differ. 1985:21–29. [Google Scholar]

56. Payne R., Abel G. UK indices of multiple deprivation – a way to make comparisons across constituent countries easier. Health Stat Q. 2012;22 [Google Scholar]

Health Stat Q. 2012;22 [Google Scholar]

57. Smith D.J., Nicholl B.I., Cullen B., Martin D., Ul-Haq Z., Evans J. Prevalence and characteristics of probable major depression and bipolar disorder within UK biobank: cross-sectional study of 172,751 participants. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e75362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Biobank U. 2011. UK Biobank: protocol for a large-scale prospective epidemiological resource. [Available from: http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/UK-Biobank-Protocol.pdf ; cited 2011 24/10/2016] [Google Scholar]

59. Biobank U. 2012. Touchscreen questionnaire. [Available from: http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Touch_screen_questionnaire.pdf?phpMyAdmin=trmKQIYdjjnQlgJ%2CfAzikMhEnx6] [Google Scholar]

60. World Health Organisation . WHO; Geneva: 1992. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. [Google Scholar]

61. American Psychiatric Association . 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV [Internet] [Google Scholar]

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV [Internet] [Google Scholar]

62. Townsend P. Deprivation. J Soc Policy. 1987:125–146. [Google Scholar]

63. Lynch M., Wasl B. Sinauer Assoicates; Sunderland, Massachusetts: 1998. Genetics and analysis of quantitative traits. [Google Scholar]

64. Robinson M., Oishi S. Trait self-reports as a ‘fill-in’ belief system: categorization speed moderates the extraversion/life satisfaction relation. Self Identity. 2006:15–34. [Google Scholar]

65. Deary I.J. Looking for ‘system integrity’ in cognitive epidemiology. Gerontology. 2012;58(6):545–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Hasler G., Drevets W.C., Manji H.K., Charney D.S. Discovering endophenotypes for major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(10):1765–1781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Fergusson M., Horwood L., Ridder E. Show me the child at seven II: childhood intelligence and later outcomes in adolescence and young adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005:850–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2005:850–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Garmezy N., Masten A.S., Tellegen A. The study of stress and competence in children: a building block for developmental psychopathology. Child Dev. 1984;55(1):97–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. LeDoux J.E., Gorman J.M. A call to action: overcoming anxiety through active coping. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):1953–1955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Higgins J., Endler N. Coping, life stress, and psychological and somatic distress. Eur J Pers. 2006:253–270. [Google Scholar]

71. Roberts B.W., Kuncel N.R., Shiner R., Caspi A., Goldberg L.R. The power of personality: the comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2(4):313–345. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Why are people with high IQ more likely to suffer from mental disorders?

Headings : Translations, Latest articles, Psychology

Did you find something useful here? Help us stay free, independent, and free by making any donation or purchasing some of our literary merchandise.

How do people with high IQ pay for their insights? We understand why very smart people are more likely to suffer from mental disorders and diseases of the body and whether they can somehow protect themselves from mental problems.

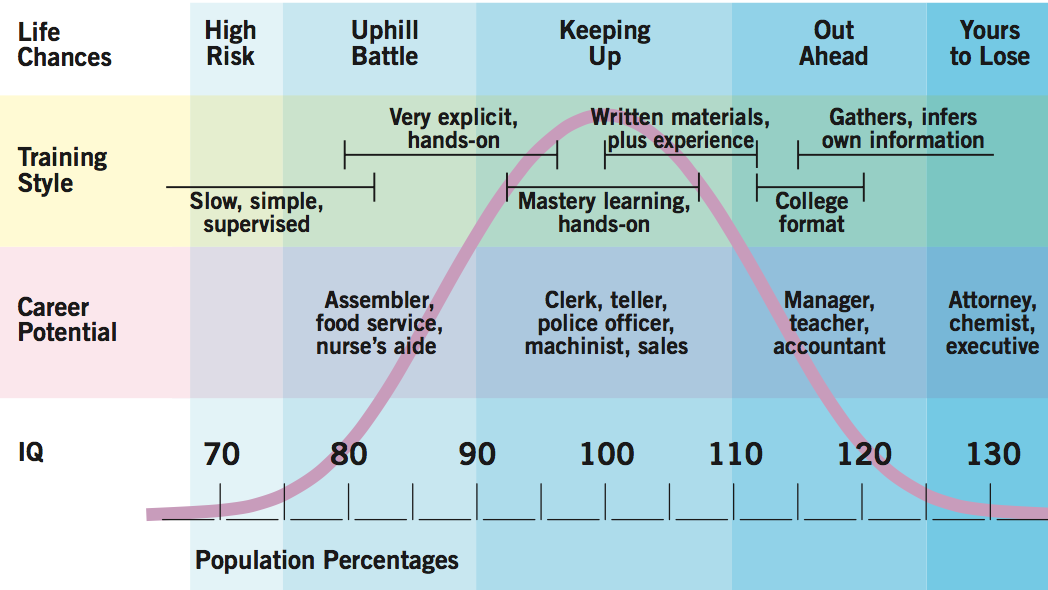

It is believed that people with high IQ excel in many areas of life. They are the ones who get the best education, they get the sweet jobs, and they probably have a higher income than people with an average IQ.

But it turns out that everything is not so optimistic and rosy. It is high IQ that is most often the cause of mental and immunological disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, all kinds of anxiety conditions, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as allergies, asthma and immune problems.

Why such injustice? A study published recently in Intelligence takes a closer look at the mechanisms that may underlie this phenomenon.

When we talk about IQ, we mean the system of testing what is called intelligence that has evolved to this day. The fact is that intelligence is a culturological concept, so an engineer, an artist or a psychologist will understand this word differently. This abstraction only takes on concrete meaning in certain cultural contexts. Nevertheless, we use the word "intellectual" to describe people who are able to acquire useful knowledge and use it to solve complex problems, using logic, intuition, creativity, experience, wisdom for this.

The fact is that intelligence is a culturological concept, so an engineer, an artist or a psychologist will understand this word differently. This abstraction only takes on concrete meaning in certain cultural contexts. Nevertheless, we use the word "intellectual" to describe people who are able to acquire useful knowledge and use it to solve complex problems, using logic, intuition, creativity, experience, wisdom for this.

The authors of the study tested 3,715 members of the Mensa Society of America, the largest and oldest organization of people with a high IQ. The aim of the study was to study the prevalence of certain diseases in them compared with the same indicators in people with an average IQ.

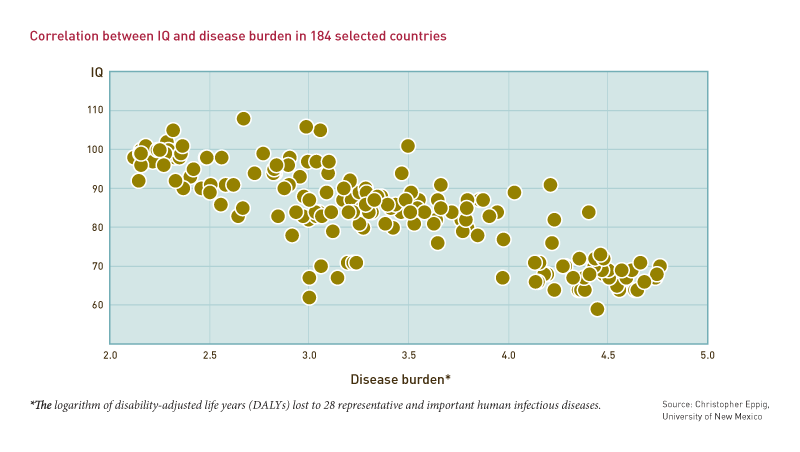

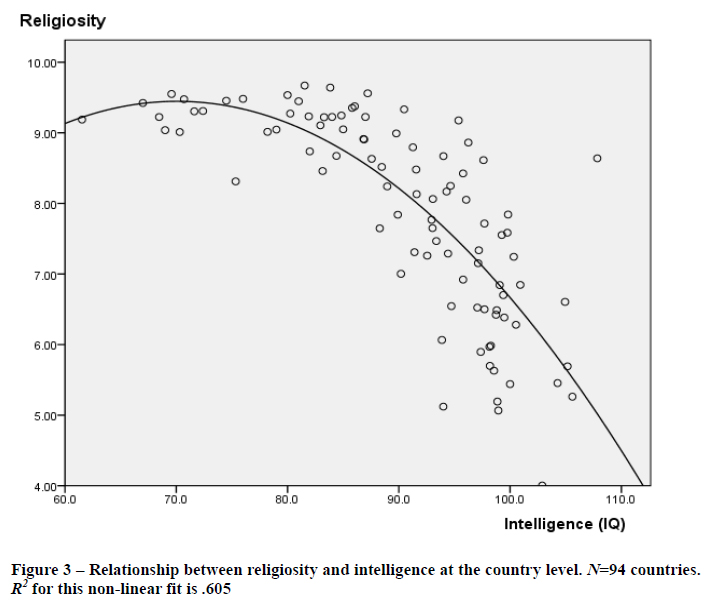

It turned out that highly intelligent people are 20% more likely to be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), 80% more likely to have ADHD, and 83% have an increased level of anxiety. The associated relative risk is 2.82, indicating a 182% increase in risk for high-intelligence patients who develop at least one of these mood disorders.

© Journal of Intelligence

In terms of physiology, people with high cognitive abilities are 213% more likely to suffer from allergies, 108% more likely to get asthma, and 84% more likely to develop autoimmune diseases.

To find out how chronic stress accumulated in response to adverse environmental factors affects the connections between the brain and the immune system, researchers turned to the field of psychoneuroimmunology.

It turns out that in highly intelligent people their passion for solving problems and riddles causes the so-called intellectual hyperexcitability and hyperreactivity of the central nervous system. On the one hand, this contributes to a deep understanding of the essence of things, helps in scientific and creative work, but on the other hand, this increased reactivity of the nervous system leads to overstrain, and, consequently, to depression or emotional instability as a kind of protection against overstrain.

It is known that the intense emotional response to the environment of writers, artists and poets requires constant rethinking and reflection. If this need does not find a good enough form of expression - does not turn into a novel, a picture or a poetic work, then then it leads either to increased anxiety, or to mania, or even to depression.

If this need does not find a good enough form of expression - does not turn into a novel, a picture or a poetic work, then then it leads either to increased anxiety, or to mania, or even to depression.

People with increased nervous excitability, the ability to empathize and empathize can react more than the average person to ordinary, seemingly harmless, external stimuli (sound, color) simply because they have a higher perceptual ability. But accumulating and not getting the proper release, these reactions can lead to a decrease in stress tolerance or chronic stress.

In this case, the activity of the immune system is disrupted, because the body believes that it is in chronic danger. It doesn't matter if the danger is real or imagined, a cascade of physiological responses is set in motion: millions of hormones, neurotransmitters and signaling molecules are being released. When these processes are activated too often, our body, brain and overall immune balance are affected. Then we get asthmatic and allergic symptoms, as well as autoimmune diseases.

Then we get asthmatic and allergic symptoms, as well as autoimmune diseases.

It is believed that gifted children are often allergic or asthmatic. Indeed, data from a study published in Intelligence shows that 44% of people with an IQ above 160 suffered from allergies more often than their peers.

The results of this study, as well as previous studies, allowed the authors to talk about the importance of mind-body integration in the case of people with high IQ:

Hypersensitivity to external events or events of the mental world, as well as those overloads that people with a high level of intelligence can withstand, automatically place them at risk.

Obsessive thinking, anxiety, re-experiencing that accompany deep mental processes and the intellectual work of scientists, poets and other representatives of creative intellectual work can cause their psyche to freeze in the “fight”, “run” or “freeze” states, which then triggers a cascade immunological events.

[…] Indeed, ideally, the immune system should provide a balance between inflammation and anti-inflammatory response. The immune signal should “light up” and then go out. In those who are chronically over-excited (including those with autism spectrum disorders), this system does not seem to have reached equilibrium and therefore the allertic signals are chronically activated.

The authors of the study conclude that there is no doubt that the topic of the relationship between high intelligence and an increased risk of physical and mental illness is important and requires further study. But even today it is obvious that this gift can be either "a catalyst for the empowerment of a person and self-actualization, or a harbinger of imbalance and debilitation."

In order for people with high IQ not to lose the quality of life, it is important for them, like no one else, to “remember also the roar of thunder that usually follows the lightning of insight.” We should not forget about the season of melancholy rains in case of failure. And if you are ready for this and mentally equipped, you can hope for many years of creative work in a healthy body.

And if you are ready for this and mentally equipped, you can hope for many years of creative work in a healthy body.

Related resource pack

- Paradoxes of the intellect: why do smart people do stupid things?

- 3 types of intelligence needed for success: Sternberg's triarchic theory

- The neuroscience of bilingualism: how multilingualism prevents dementia

Based on: Why highly intelligent people suffer more mental and physical disorders / Big Think

Cover: "Self-portrait", Vincent van Gogh, 1888

If you find an error, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter .

human intelligencepsychology

between depression and intelligence found a genetic connection

myth about a “crazy genius” to almost everyone. It is believed that if not all, then many brilliant people necessarily pay for their talent with one or another mental illness. Vincent van Gogh suffered from bouts of psychosis, Ernest Hemingway was deeply depressed and drank heavily, Nobel Laureate in Economics Joe Nash suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, and Edvard Munch apparently had bipolar disorder. The list could go on and on, but the question of whether there really is a link between mental illness and genius is much more interesting. Let's take depression for example. This serious disease, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), worldwide affects more than 264 million people from all age groups. How many geniuses are among these 264 million and is it even correct to ask such a question? Recently, an international team of scientists published the results of a study, according to which there is a genetic link between depression and intelligence.

Vincent van Gogh suffered from bouts of psychosis, Ernest Hemingway was deeply depressed and drank heavily, Nobel Laureate in Economics Joe Nash suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, and Edvard Munch apparently had bipolar disorder. The list could go on and on, but the question of whether there really is a link between mental illness and genius is much more interesting. Let's take depression for example. This serious disease, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), worldwide affects more than 264 million people from all age groups. How many geniuses are among these 264 million and is it even correct to ask such a question? Recently, an international team of scientists published the results of a study, according to which there is a genetic link between depression and intelligence.

Is there a link between depression and intelligence?

Paying for intelligence

There are advantages to being smart. People who do well on standard intelligence tests (IQ tests) tend to do well in school and at work. According to Scientific American, although the reasons are not fully understood, people with high IQs also tend to live longer, have better health, and are less likely to experience negative life events like bankruptcy.

According to Scientific American, although the reasons are not fully understood, people with high IQs also tend to live longer, have better health, and are less likely to experience negative life events like bankruptcy.

But every coin has a reverse side. So, the results of a study published in the journal Intelligence in 2017 showed that a particular mental disorder is more common in a sample of people with high IQ than in the general population.

The survey, which covered mood disorders (depression, dysthymia and bipolar disorder), anxiety disorders (generalized, social and obsessive-compulsive disorders), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism, was attended by members of the association Mensa is the largest, oldest and best known organization for people with a high IQ (with an average IQ of around 132 and above). The survey also asked subjects to indicate whether they suffer from allergies, asthma, or other autoimmune disorders. The results obtained showed that people with high intelligence really often suffer from one mental illness or another.

The results obtained showed that people with high intelligence really often suffer from one mental illness or another.

Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking are believed to have an IQ of 160.

I note that the results of the study should be interpreted with caution. That the disorder is more common in a sample of high-IQ individuals than in the general population, does not prove that high intelligence is the cause of the disorder. It is also possible that Mensa members differ from other people in more than just IQ. For example, knowledge workers may spend less time than the average person on physical exercise and social interaction, which have psychological and physical health benefits.

Interested in science and technology news? Subscribe to our news channel in Telegram so as not to miss anything interesting!

To explain the results obtained in the course of the work, the authors of the study proposed the "hyper brain/hyper body theory" of integration, according to which, for all its advantages, high intelligence is associated with psychological and physiological "hyper excitability". And the results of a new study published in the journal Nature Human Behavior reveal "a surprising common genetic architecture between depression and intelligence."

And the results of a new study published in the journal Nature Human Behavior reveal "a surprising common genetic architecture between depression and intelligence."

Relationship between depression and intelligence

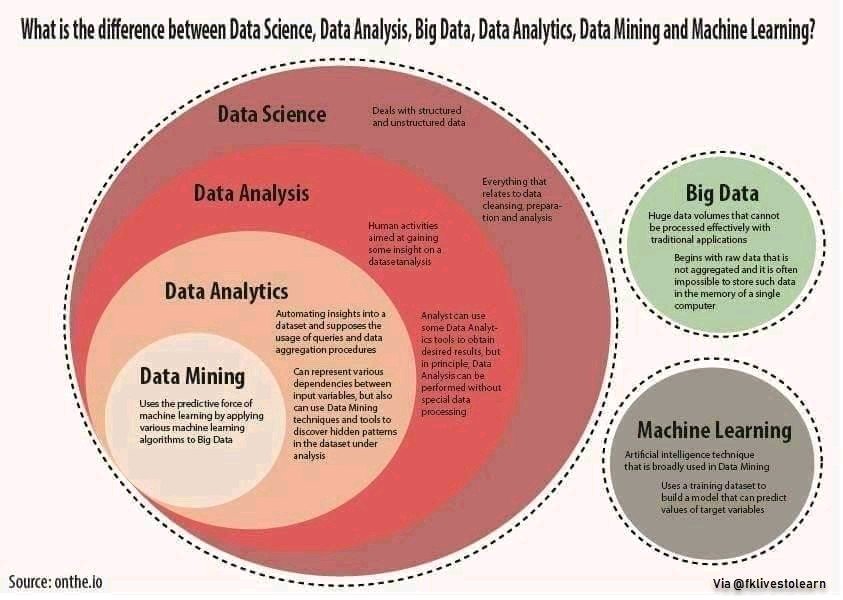

To be more precise, the new work is an extensive analysis of a large number of scientific studies. In the course of the work, the team of scientists used a statistical approach to analyze large datasets studying the relationship between genetics and depressive disorders. The data used by the scientists was collected by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium and 23andMe, which included cases where people reported any symptoms of depression.

Depression is the worst disease you can get. At least that's what the neuroendocrinologist, Stanford University professor Robert Sapolsky thinks.

Read also: How should one live in order not to suffer from depression?

The sample consisted of 135,458 cases of major depression and 344,901 controls. Data on general cognitive abilities were collected from 269,867 people, with 72% coming from the UK Biobank research database. Interestingly, each of the 14 cohort studies included in the extensive meta-analysis measured intelligence differently using different mathematical, intelligence, and verbal cognitive tests. The authors of the studies also tested people on their memory, attention, processing speed and IQ.

Data on general cognitive abilities were collected from 269,867 people, with 72% coming from the UK Biobank research database. Interestingly, each of the 14 cohort studies included in the extensive meta-analysis measured intelligence differently using different mathematical, intelligence, and verbal cognitive tests. The authors of the studies also tested people on their memory, attention, processing speed and IQ.

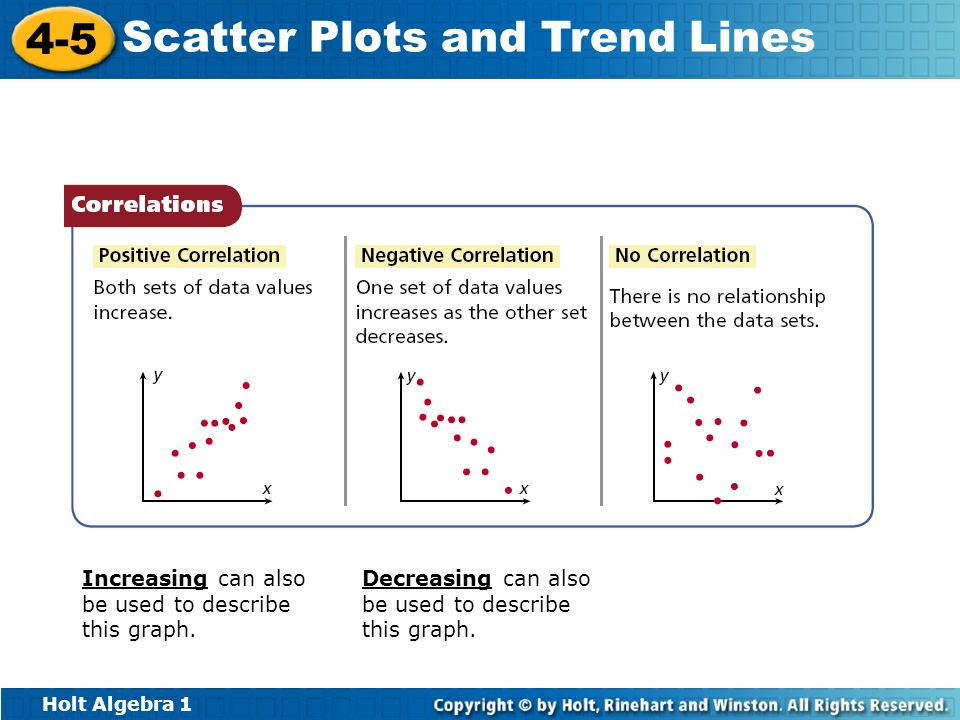

The results showed that the effects of genes that affect both intelligence and mood are mixed: about half of the common genes work in coordination, promoting or suppressing both traits, and the other half promote one trait while suppressing the other. In fact, the genes that underlie depression and intelligence work haphazardly - sometimes the more severe a person's depression, the worse their cognitive functions; in other cases, the more severe the depression, the higher his mental abilities, - the words of the authors of the scientific work are quoted by the publication Inverse.