Is a broken heart real

Is Broken Heart Syndrome Real?

When Your Heart Breaks … Literally

When you think of a broken heart, you may picture a cartoon drawing with a jagged line through it. But a real-life broken heart can lead to cardiac issues. Depression, mental health and heart disease have established ties. Read on for more information about how an extremely stressful event can have an impact on your heart.

Breakdown of a Broken Heart

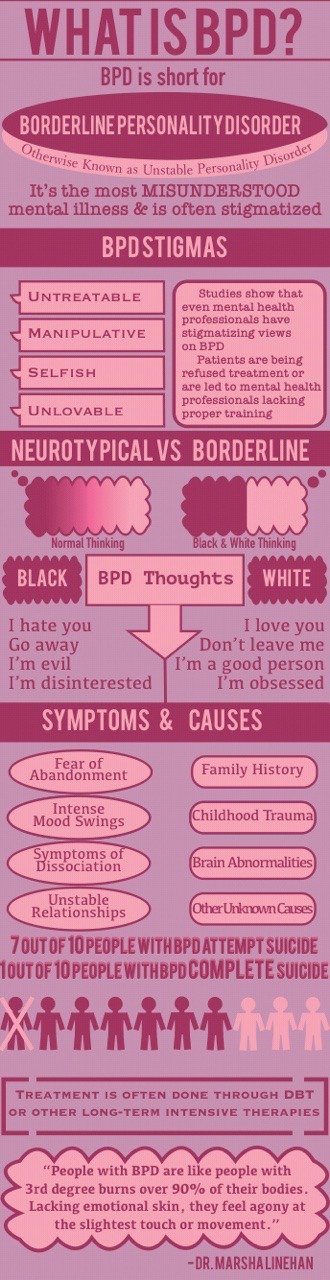

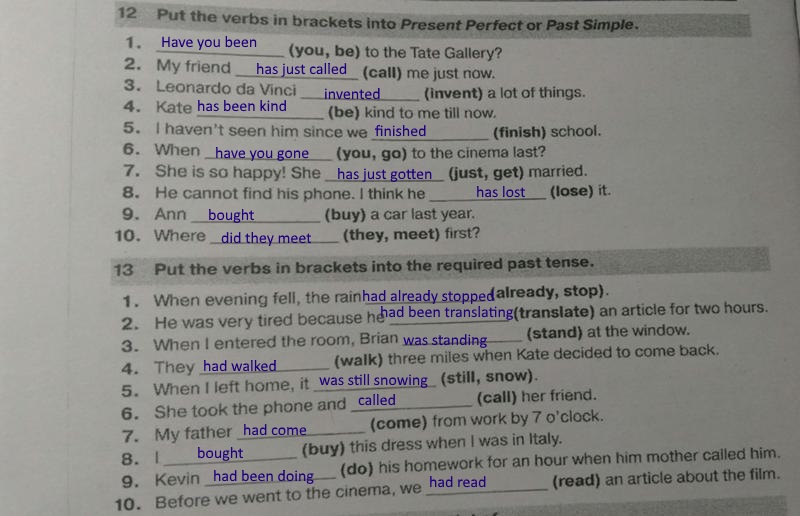

Broken heart syndrome, also called stress-induced cardiomyopathy or takotsubo cardiomyopathy, can strike even if you’re healthy. (Takotsubo are octopus traps that resemble the pot-like shape of the stricken heart.)

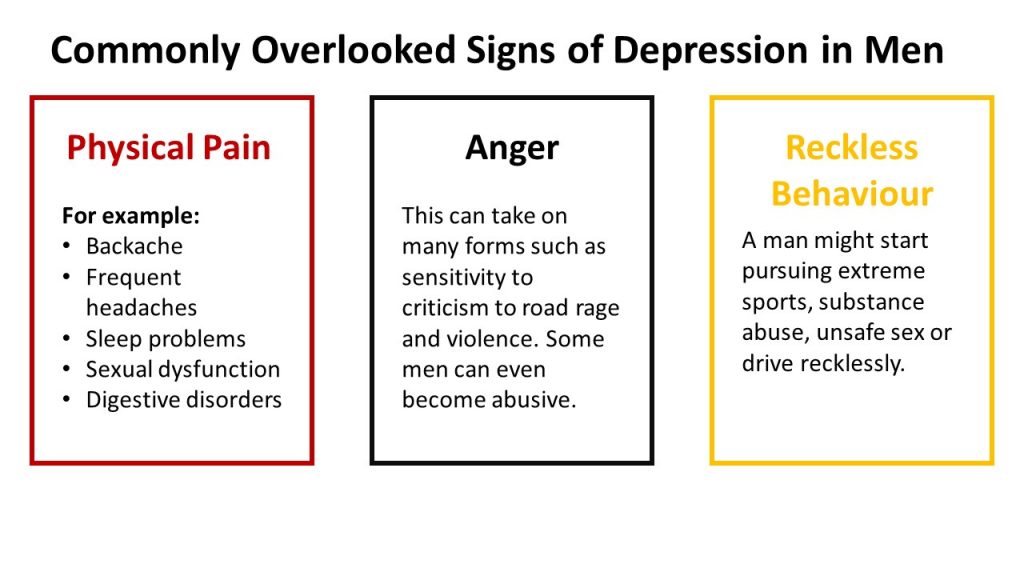

Women are more likely than men to experience sudden, intense chest pain — the reaction to a surge of stress hormones — that can be caused by an emotionally stressful event. It could be the death of a loved one or a divorce, breakup or physical separation, betrayal or romantic rejection. It could even happen after a good shock, such as winning the lottery.

Broken heart syndrome may be misdiagnosed as a heart attack because the symptoms and test results are similar. Tests show dramatic changes in rhythm and blood substances that are typical of a heart attack. But unlike a heart attack, there’s no evidence of blocked heart arteries.

In broken heart syndrome, a part of your heart temporarily enlarges and doesn’t pump well, while the rest of your heart functions normally or with even more forceful contractions. Researchers continue to learn more about the causes, and how to diagnose and treat it.

The bad news: Broken heart syndrome can lead to severe, short-term heart muscle failure.

The good news: Broken heart syndrome is usually treatable. Most people who experience it make a full recovery within weeks, and they’re at low risk for it happening again (although in rare cases it can be fatal).

What To Look For: Signs and Symptoms

The most common signs and symptoms of broken heart syndrome are angina (chest pain) and shortness of breath. You can experience these things even if you have no history of heart disease.

Arrhythmias (abnormal heartbeats) or cardiogenic shock also may occur with broken heart syndrome. Cardiogenic shock is a condition in which a suddenly weakened heart can’t pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs, and it can be fatal if it isn’t treated right away. When people die from heart attacks, cardiogenic shock is the most common cause.

Heart attack and broken heart syndrome: What’s the difference?

Some signs and symptoms of broken heart syndrome differ from those of heart attack. In broken heart syndrome, symptoms occur suddenly after extreme emotional or physical stress. Here are some other differences:

- EKG (a test that records the heart’s electric activity) results don’t look the same as the EKG results for a person having a heart attack.

- Blood tests show no signs of heart damage.

- Tests show no signs of blockages in the coronary arteries.

- Tests show ballooning and unusual movement of the lower left heart chamber (left ventricle).

- Recovery time is usually within days or weeks, compared with the recovery time of a month or more for a heart attack.

Learn More About Broken Heart Syndrome

If your health care professional thinks you have broken heart syndrome, you may need coronary angiography, a test that uses dye and special X-rays to show the inside of your coronary arteries. Other diagnostic tests are blood tests, EKG, echocardiography (a painless test that uses sound waves to create moving pictures of your heart) and cardiac MRI.

To keep tabs on your heart health, your health care professional may recommend an echo about a month after you’re diagnosed with the syndrome. Ask how often you should schedule follow-up visits.

Written by American Heart Association editorial staff and reviewed by science and medicine advisers. See our editorial policies and staff.

Last Reviewed: May 4, 2022

Related Articles

Warning Signs of a Heart Attack

Taking Care of Yourself

Stress Management

How Emotional Trauma Can Harm Your Heart

Written by WebMD Editorial Contributors

In this Article

- The Heart Responds

- Who Gets It?

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

- Recovery

You’ve seen it in movies or in the news: Sweethearts married for decades die within a few days of each other. People call it “broken heart syndrome,” and it’s real.

Losing a loved one can be emotionally devastating. It’s rare, but sometimes an overwhelming loss can affect physical health, including the heart, too.

Luckily, doctors can treat most cases, if you know what to look out for.

The Heart Responds

Broken heart symptoms, such as chest tightness and shortness of breath, can seem like a heart attack.

The problem happens when psychological distress triggers sudden weakness of the heart muscle. It can be caused by sudden shock or acute anxiety. Doctors call it “stress-induced cardiomyopathy” or “takotsubo cardiomyopathy.”

The heart has its mysteries, including the reason why it can suddenly grow weak due to physical or emotional stress.

It could be that a flood of the stress hormone adrenaline is too much for it to handle. One theory is that adrenaline causes the heart’s arteries to narrow so much that they cut off blood flow to the muscle.

Unlike a heart attack, broken heart syndrome makes part of your heart larger, temporarily.

This can change how your ticker pumps, which causes the symptoms.

Who Gets It?

It can happen to anyone, but it’s more common among women than men, in middle age or older. What makes the condition even more puzzling is that the people who get it usually have no history of heart trouble.

While we tend to hear about broken heart syndrome when someone loses their long-time spouse or partner, it can happen in other situations, too. Someone might go through it after a major relationship breakup, serious financial problems, job loss, or domestic abuse. It can also happen in situations that make you extremely anxious, like public speaking, or very startled, such as a surprise party. The stress of surgery and other major physical issues may also act as a trigger.

Diagnosis

Because the symptoms can feel like a heart attack, you should call 911. Even if it is not a heart attack, the initial symptoms may be life-threatening, so it is important to get medical attention.

At the hospital, you may get blood tests and an electrocardiogram (EKG). If it’s broken heart syndrome, those results will help confirm that it wasn’t a heart attack.

Imaging tests -- a coronary angiogram, for example -- would show that your organ's lower left chamber is bigger than normal, and that your heart isn’t pumping the way it should.

Tell your doctor about your loss and your grief, too. This can help them figure out what’s going on.

Treatment

You may need medicines to manage your blood pressure and lighten some of the strain on the heart. These drugs include “water pills” or diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and beta blockers.

Talk with your doctor about how you’ll need to take these medications.

Because your heart became weaker, you may be more likely to get heart failure or to have heart rhythm problems. Your doctor should talk about that with you and tell you what follow-up care you’ll need.

Counseling can also help you with the grief or anxiety that brought on your symptoms. Ask your doctor to recommend a therapist who can help you talk through your feelings and find ways to manage them as you face your new situation.

Recovery

In a few months, you should be past the heart problems.

After that, you’re not at any higher risk of a broken heart than anyone else.

Broken Heart Syndrome: a disease "out of the head" from which you can die

Sign up for our "Context" newsletter: it will help you understand the events.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Your heart can suffer after some unfortunate event, and your brain is most likely responsible for your "heartbreak", experts say.

Swiss scientists are conducting a study on the so-called "broken heart syndrome".

Psychological stress can cause acute transient left ventricular dysfunction. The syndrome is manifested by the sudden development of heart failure or chest pain, combined with ECG changes characteristic of myocardial infarction of the anterior wall of the left ventricle.

- Scientists have found out how stress causes heart disease

Most often, this syndrome develops against the background of stressful situations that cause strong, often sharply negative, emotions. Such events can be the death of a loved one or separation.

Scientists do not yet have complete clarity on how this happens. In the publication of scientists in the medical journal European Heart Journal, it is suggested that the syndrome is provoked by the brain's response to stress.

The "broken heart syndrome" was first described by the Japanese scientist Hikaru Sato in 1990 and was named "takotsubo cardiomyopathy" (from the Japanese "takotsubo" - a ceramic pot with a round base and a narrow neck).

Image copyright Getty Images

This is different from a "normal" heart attack, when blood flow to the heart muscle is blocked. Blockage of blood flow to the heart occurs when there is a blood clot in the coronary arteries.

However, the symptoms of broken heart syndrome and heart attack are similar in many ways, most notably difficulty breathing and chest pain.

- Scientists: the brain of boys and girls reacts differently to severe stress

- Scientists: early baldness can be a sign of heart disease

Often some sad event is a kind of trigger that provokes the onset of the syndrome. However, joyful events that cause strong emotions can also lead to the development of broken heart syndrome. For example, getting married or getting a new job.

Broken heart syndrome can be temporary, in which case the heart muscle will recover in a few days, weeks or months, and in some cases the syndrome can be fatal.

In Britain, about 2500 patients are diagnosed with broken heart syndrome each year.

Image copyright Christian Templin, University Hospital Zurich

Image captionX-ray of the heart of a person diagnosed with takotsubo syndrome

Skip Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

End of story Podcast

The exact cause of broken heart syndrome is unknown to scientists. However, it is suggested that this syndrome may be associated with an increase in the level of stress hormones - for example, adrenaline.

Elena Gadri from the University Hospital Zurich, together with her colleagues, studied the brain activity of 15 patients diagnosed with broken heart syndrome.

Imaging data showed significant differences in the brain activity of these patients from that seen in 39 healthy controls.

Much less communication has been noted between the areas of the brain responsible for controlling emotions and the body's unconscious (automatic) responses (such as the heartbeat).

"Emotions are formed in the brain, so it is quite possible that the disease is formed in the brain. And then the brain sends the appropriate signals to the heart," says Gadry.

Further research is needed to understand the mechanism of the syndrome.

The Swiss scientists who conducted the study had no CT scans of the patients before they were diagnosed with broken heart syndrome. Therefore, researchers cannot claim that the reduction in connections between different parts of the brain was a consequence of the development of the syndrome, or that the syndrome developed due to the reduction in connections.

"This is a very important part of the study, it will help us better understand the nature of this syndrome, which is often overlooked, and it continues to be a mystery to us," says Joel Rose, head of the British organization Cardiomyopathy.

"These studies will help us understand what role the brain plays in the syndrome and why some people are affected and others are not," says Joel Rose.

"These observations confirm our long-standing assumption about the special role of the connection between the brain and the heart in the formation of takotsubo cardiomyopathy," says researcher Dana Dawson from the British Heart Foundation.

A broken heart is not a metaphor, but the real cause of death. How Heart Disease and Emotions Are Linked

No other human organ — really, nothing else in people's lives is associated with so many metaphors and meanings as the heart. Throughout history, it is a symbol of emotional life. But is there a real connection between the heart and emotions? Or are we just living in a world of metaphors? Cardiologist Sandeep Jauhar says.

Even the very word "emotions" refers us to the French "émouvoir", which means "to stir up". That is, it is logical that emotions are associated with an organ that is always in motion. And as a cardiologist, I would like to say: there is a connection between them. Emotions, as you will soon see, can and do affect the human heart.

Before we dive into the facts, let's stay in the world of metaphors for a while. The symbolism of emotions is what is still with us. If we ask people what they associate with love, there is no doubt that the heart will lead this hit parade. The cardioid, the shape of the heart, is common in nature. We can find it in leaves, flowers, plant seeds, including silphium, which was used for birth control in the Middle Ages. Perhaps this was the reason why the heart became associated with sex and romantic love.

We now know that the heart itself is not a source of love and emotion. The ancient people were wrong. But nevertheless, we are becoming more and more convinced that there is a direct connection between the heart and emotions. No, of course, the heart cannot be a source of feelings, but it reacts vividly to everything that happens to us. Our emotional life is inseparable from our heart. We can say that it documents it.

Grief or fear experienced by people can lead to serious heart problems

The nerves that control the heartbeat can trigger the fight-or-flight response in distress. This, in turn, causes narrowing of blood vessels, leading to an increase in blood pressure, which can be followed by damage to the heart. Simply put, our hearts are incredibly sensitive and dependent on emotions, on those very metaphorical meanings.

Several decades ago, a disease called "takotsubo cardiomyopathy" or "broken heart syndrome" was recognized as existing. In response to severe stress or grief (for example, after a difficult breakup or death of a loved one), myocardial weakness occurs.

The grieving heart even visually looks completely different. It looks dazed and swells up in the shape of a takotsubo, a Japanese pot with a wide base and a narrow neck. We still don't know exactly why this happens, and the syndrome itself usually goes away within a few weeks. But it can cause acute heart failure, arrhythmia that threatens a person's life, and even death.

The husband of one of my elderly patients recently died. She accepted this death, but, of course, she did not stop grieving. The man died after a long illness, he had senile dementia. A week after the funeral, she looked at his photographs. And then there was pain in my chest. Along with her - shortness of breath, swollen neck veins, she began to choke, sitting on a chair. In general, all signs of heart failure. The woman was hospitalized, an ultrasound in the hospital confirmed what we already suspected: her heart took the shape of a takotsubo. At the same time, there were no signs of blockage of the arteries. The woman's condition returned to normal after two weeks. The heart on the ultrasound returned to its usual shape.

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy can be triggered by a variety of factors. Public speaking, for example. Domestic disputes. Losing at gambling. And even a birthday surprise.

It is also associated with social upheavals and natural disasters. For example, in 2004, a powerful earthquake occurred in Japan. More than 60 people died and thousands were injured. After this disaster, an increase in the number of cases of takotsubo cardiomyopathy was recorded - their frequency increased 24 times compared to a year earlier. The place where people lived also mattered - more often cardiomyopathy was recorded in those who were near the epicenter.

Not only grief matters. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy can also appear after a happy event, but the heart reacts differently to grief and happiness - for example, the left ventricle behaves differently.

Why different emotional factors lead to different changes in the heart, we still do not know. This is a mystery

The emotional heart is larger than its biological counterpart in a surprising and mysterious way.

Yes, it is no longer a secret that severe emotional disturbances can cause heart problems and even death. At 19In 1942, Harvard physiologist Walter Cannon published an article entitled "The Death of Voodoo", where he described the death from fear of those people who believed that they were cursed by sorcerers. The victim of the "curse" could fall dead on the spot. Common to all cases was that the victim believed in a force that could kill her. A force that cannot be countered.

Cannon suggested that this belief prompted a physiological response: the blood vessels constricted to such an extent that blood volume and pressure plummeted, the heart weakened, and massive organ damage occurred as a result of the lack of oxygen. He suggested that the lethality of voodoo rituals is connected with the primitiveness of people. But time has shown that this does not play a role. This type of death has happened and is happening. Broken hearts are dangerous, literally and figuratively.

A similar picture is observed in animals. In one experiment published in Science in 1980, researchers fed caged rabbits a diet high in cholesterol to study its effect on cardiovascular disease. In the end, they found that with the same diet, some rabbits got sick more often. With almost the same diet, environment and genetics.

The researchers speculated that this might be due to the way technicians work with animals, so they repeated the experiment, dividing the rabbits into two groups. Both were on a high-cholesterol diet, but one group of animals lived in cages while others were let out, stroked, played with and talked to. As a result, in the group where the rabbits communicated with people, the incidence of aortic diseases was 60% lower than in the other. With the same cholesterol level, blood pressure and heart rate.

Today, it is not philosophers who care more about hearts, but doctors. From an object filled with a thousand metaphorical meanings, it has turned into a machine that can be controlled and manipulated. But, as in the old days, these manipulations must have an emotional background.

Consider another study, Lifestyle of the Heart, published in The Lancet in 1990. The scientists randomly divided 48 patients with moderate and severe coronary disease into groups. Some were prescribed routine care, others a lifestyle that included a vegetarian diet, moderate aerobic exercise, group psychosocial support, and stress management advice. As a result, it turned out that diet and exercise alone are not enough to facilitate the regression of coronary disease. Stress management was more strongly correlated with coronary disease than exercise.

In general, there are few rather than many such studies, and correlation is not yet proof of causation. Perhaps stress leads to a host of unhealthy habits that increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. But, as in the case of smoking and lung cancer, it is clear that studies pointing to the connection of these conditions should not be denied.

It probably exists. Many physicians have come to the same conclusion that I have (in almost two decades as a cardiologist) that the emotional heart intersects with its biological counterpart in surprising and mysterious ways.

Medicine continues to think of the heart as a machine. And that's good

In cardiology, my area of expertise, a lot of incredible things have happened over the past 100 years. Stents, pacemakers, defibrillators, coronary artery bypass grafts, heart transplants have all been developed or invented since World War II.

But let's think, what if we are approaching our maximum, the limit of what scientific medicine is capable of in the field of heart disease? Yes, their mortality rate is decreasing. But what's next? We need to move to a new paradigm so as not to miss the progress, the pace that we are used to. In this newest paradigm, psychosocial factors must come into focus.

This is a huge challenge for us. An area that has largely remained unexplored. The American Heart Association still does not consider emotional stress to be a key modifiable risk factor for heart disease. Why? If only because lowering the level of cholesterol in the blood is much easier than working with emotional and social disorders.

Let's admit it already: when we say the phrase "heartbreak", we sometimes mean it literally. We must pay more attention to the power and importance of emotions in order to take care of our hearts. After all, emotional stress, without exaggeration, often becomes a matter of life and death.