Icd 10 psychosis nos

Unspecified psychosis not due to a substance or known physiological condition

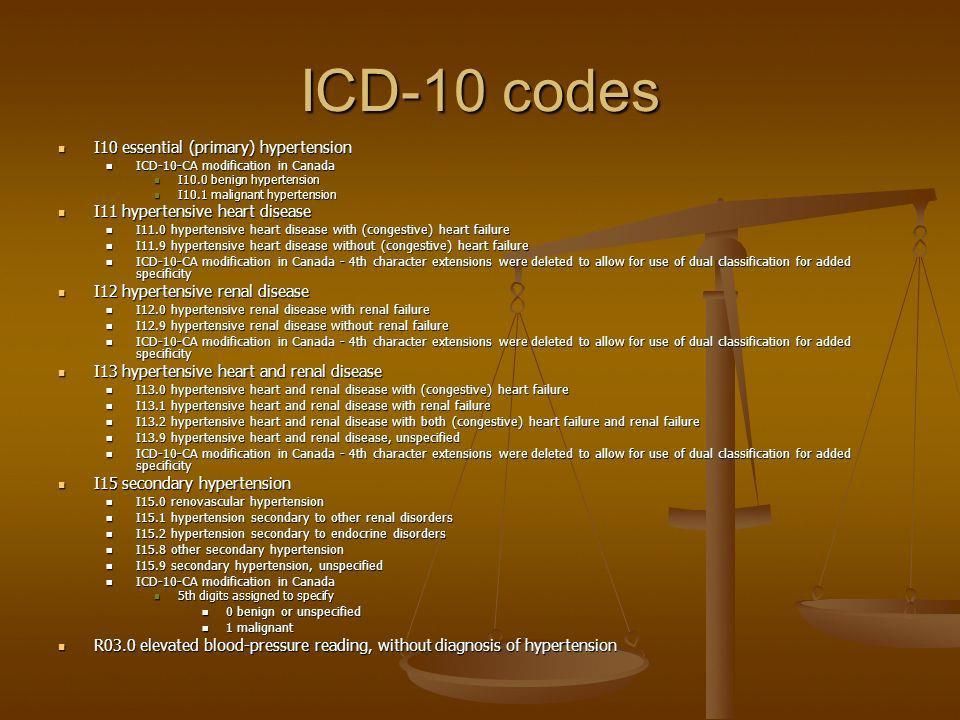

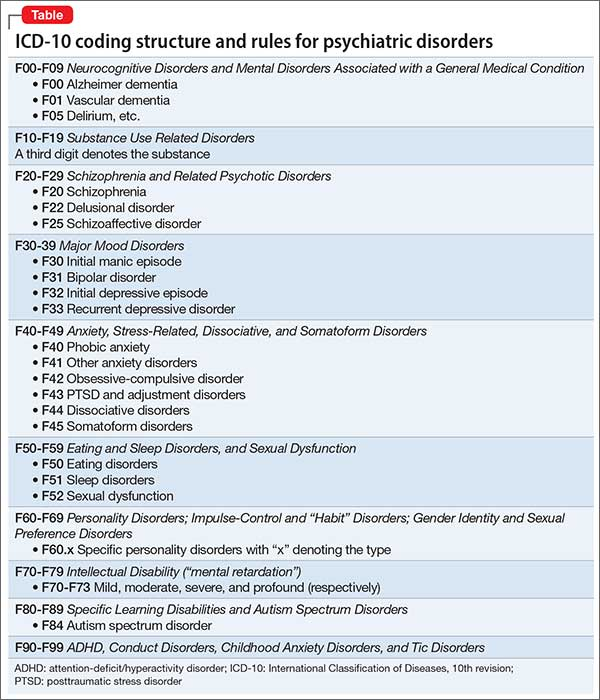

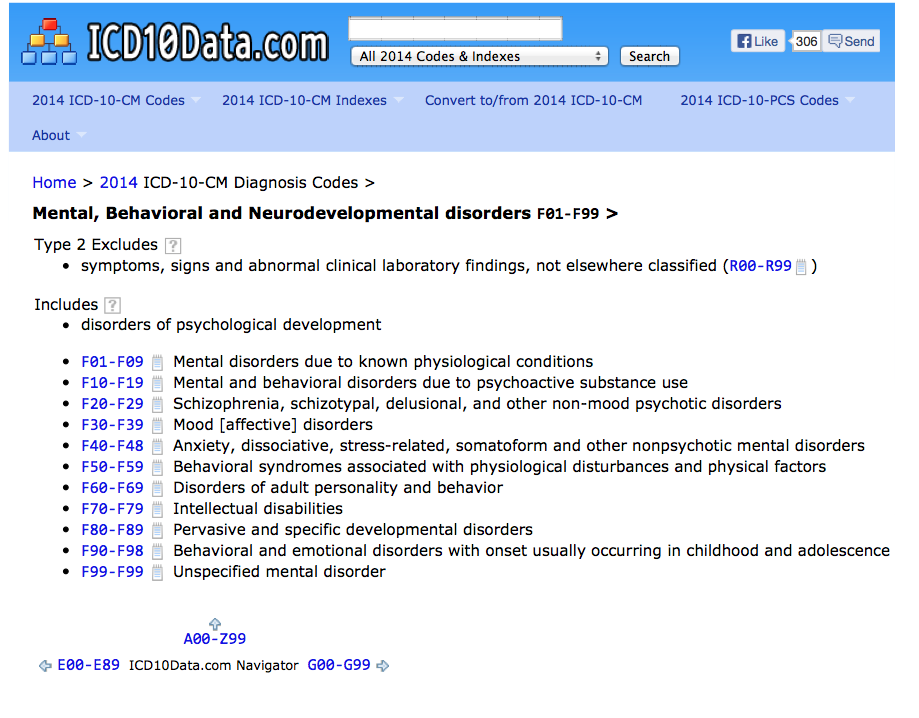

- ICD-10-CM Codes ›

- F01-F99 ›

- F20-F29 ›

- F29- ›

- 2023 ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code F29

Unspecified psychosis not due to a substance or known physiological condition

- 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 Billable/Specific Code

- F29 is a billable/specific ICD-10-CM code that can be used to indicate a diagnosis for reimbursement purposes.

- Short description: Unsp psychosis not due to a substance or known physiol cond

- The 2023 edition of ICD-10-CM F29 became effective on October 1, 2022.

- This is the American ICD-10-CM version of F29 - other international versions of ICD-10 F29 may differ.

Applicable To

- Psychosis NOS

- Unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder

Type 1 Excludes

Type 1 Excludes Help

A type 1 excludes note is a pure excludes. It means "not coded here". A type 1 excludes note indicates that the code excluded should never be used at the same time as F29. A type 1 excludes note is for used for when two conditions cannot occur together, such as a congenital form versus an acquired form of the same condition.

- mental disorder NOS (

ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code F99

Mental disorder, not otherwise specified

- 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 Billable/Specific Code

Applicable To

- Mental illness NOS

Type 1 Excludes

- unspecified mental disorder due to known physiological condition (F09)

- unspecified mental disorder due to known physiological condition (

ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code F09

Unspecified mental disorder due to known physiological condition

- 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 Billable/Specific Code

Applicable To

- Mental disorder NOS due to known physiological condition

- Organic brain syndrome NOS

- Organic mental disorder NOS

- Organic psychosis NOS

- Symptomatic psychosis NOS

Code First

- the underlying physiological condition

Type 1 Excludes

- mild neurocognitive disorder due to known physiological condition (F06.

7-)

7-) - psychosis NOS (F29)

The following code(s) above F29 contain annotation back-references

Annotation Back-References

In this context, annotation back-references refer to codes that contain:

- Applicable To annotations, or

- Code Also annotations, or

- Code First annotations, or

- Excludes1 annotations, or

- Excludes2 annotations, or

- Includes annotations, or

- Note annotations, or

- Use Additional annotations

that may be applicable to F29:

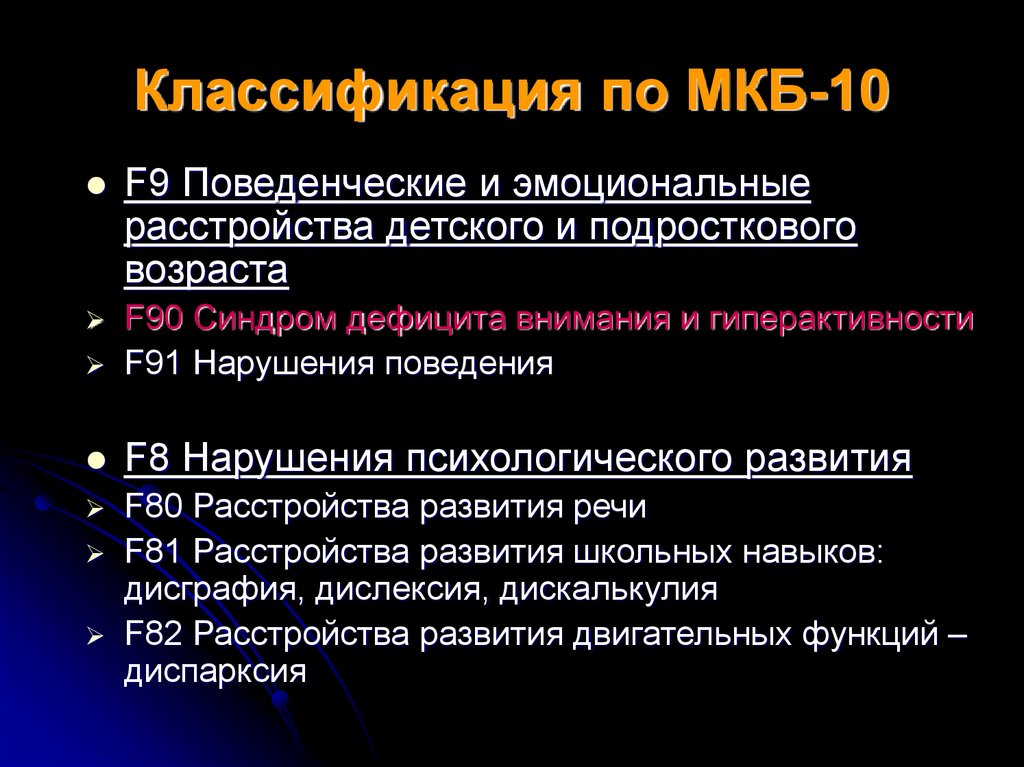

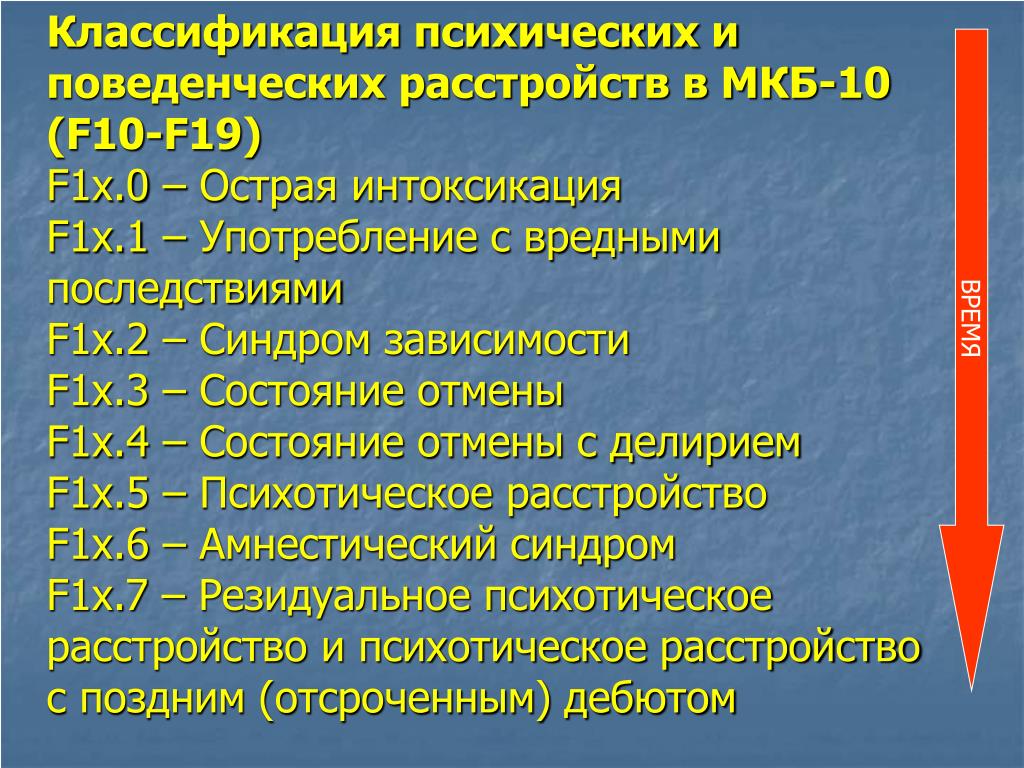

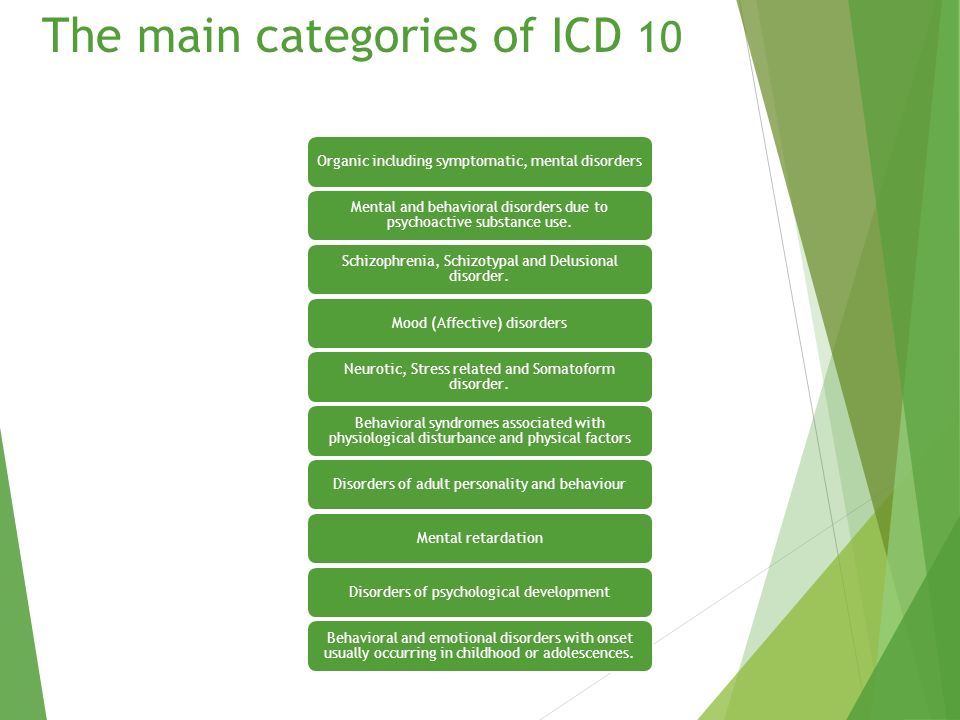

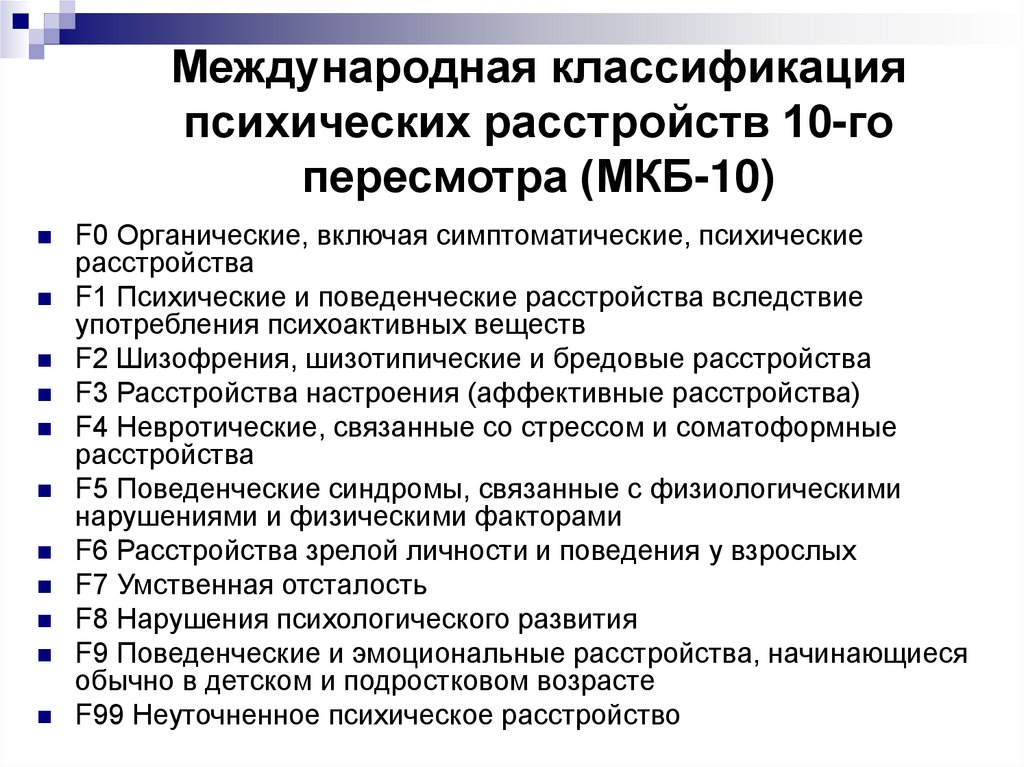

- F01-F99

2023 ICD-10-CM Range F01-F99

Mental, Behavioral and Neurodevelopmental disorders

Includes

- disorders of psychological development

Type 2 Excludes

- symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (R00-R99)

Approximate Synonyms

- Psychosis in childbirth

- Psychosis in pregnancy

- Psychotic

- Psychotic disorder

ICD-10-CM F29 is grouped within Diagnostic Related Group(s) (MS-DRG v40. 0):

0):

- 885 Psychoses

- 974 Hiv with major related condition with mcc

- 975 Hiv with major related condition with cc

- 976 Hiv with major related condition without cc/mcc

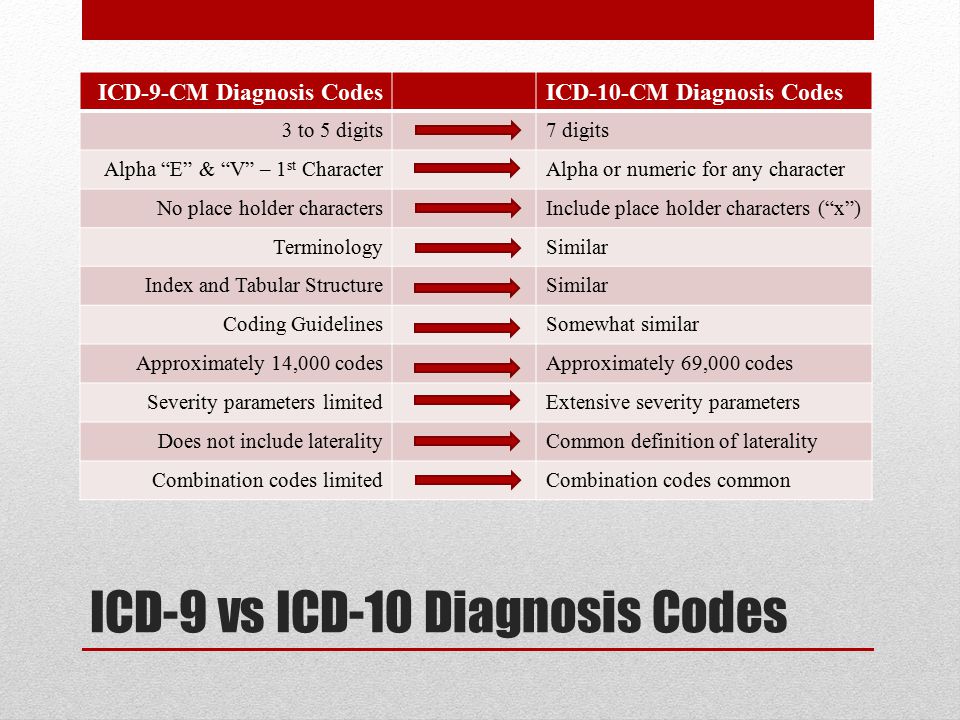

Convert F29 to ICD-9-CM

Code History

- 2016 (effective 10/1/2015): New code (first year of non-draft ICD-10-CM)

- 2017 (effective 10/1/2016): No change

- 2018 (effective 10/1/2017): No change

- 2019 (effective 10/1/2018): No change

- 2020 (effective 10/1/2019): No change

- 2021 (effective 10/1/2020): No change

- 2022 (effective 10/1/2021): No change

- 2023 (effective 10/1/2022): No change

Code annotations containing back-references to F29:

Diagnosis Index entries containing back-references to F29:

- Disorder (of) - see also Disease

- schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder F29

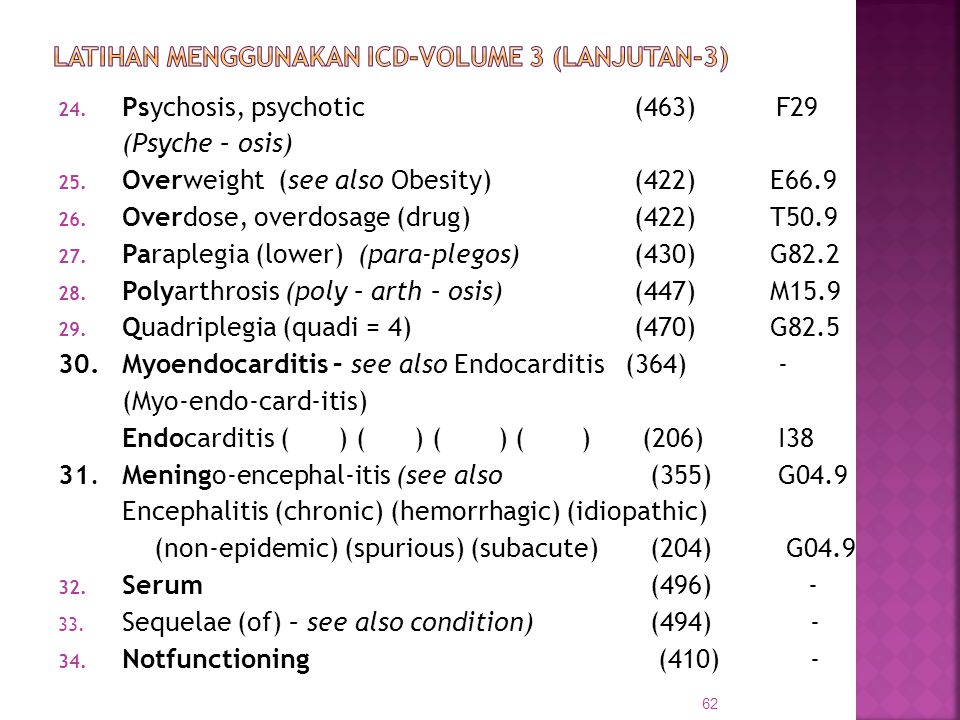

- Psychosis, psychotic F29

- confusional F29

- nonorganic F29

- Schizophrenia, schizophrenic F20.

9

9ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code F20.9

Schizophrenia, unspecified

- 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 Billable/Specific Code

- spectrum and other psychotic disorder F29

ICD-10-CM Codes Adjacent To F29

F21 Schizotypal disorder

F22 Delusional disorders

F23 Brief psychotic disorder

F24 Shared psychotic disorder

F25 Schizoaffective disorders

F25. 0 Schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type

0 Schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type

F25.1 Schizoaffective disorder, depressive type

F25.8 Other schizoaffective disorders

F25.9 Schizoaffective disorder, unspecified

F28 Other psychotic disorder not due to a substance or known physiological condition

F29 Unspecified psychosis not due to a substance or known physiological condition

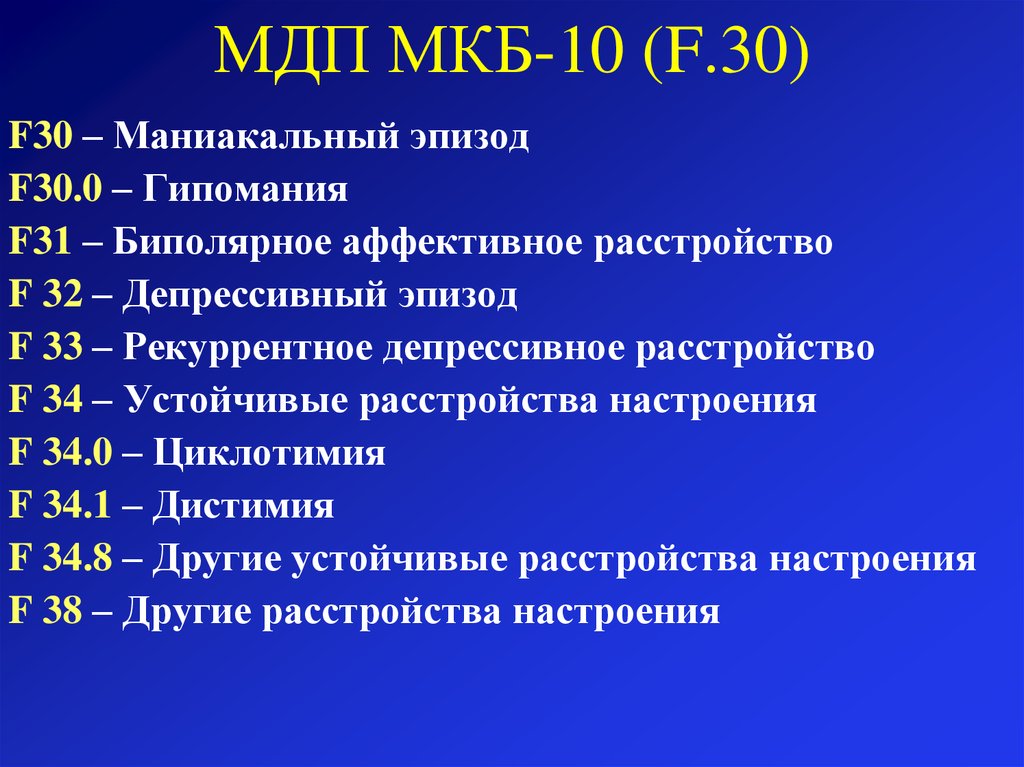

F30 Manic episode

F30. 1 Manic episode without psychotic symptoms

1 Manic episode without psychotic symptoms

F30.10 …… unspecified

F30.11 …… mild

F30.12 …… moderate

F30.13 Manic episode, severe, without psychotic symptoms

F30. 2 Manic episode, severe with psychotic symptoms

2 Manic episode, severe with psychotic symptoms

F30.3 Manic episode in partial remission

F30.4 Manic episode in full remission

F30.8 Other manic episodes

Reimbursement claims with a date of service on or after October 1, 2015 require the use of ICD-10-CM codes.

Evaluation of Four-Year Stability of Unspecified Psychosis

Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2019 Mar; 56(1): 47–51.

Published online 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.29399/npa.22903

,1,2 and 3

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Introduction

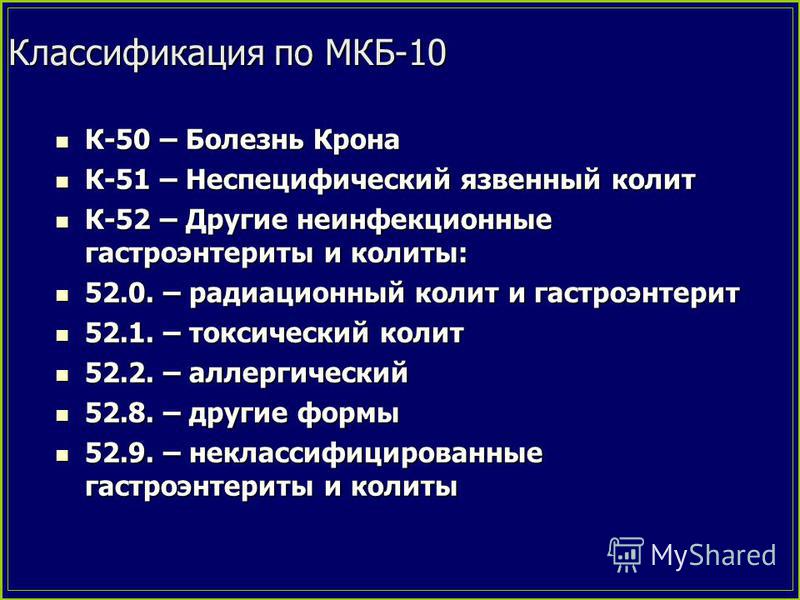

Unspecified psychosis, defined with the F29 code in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10th version is commonly used if there is inadequate information to make the diagnosis of a specific psychotic disorder. There is a lack of data about the prevalence, incidence, diagnostic validity and stability of this diagnosis. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the prevalence and diagnostic consistency of unspecified psychosis in the outpatient unit.

There is a lack of data about the prevalence, incidence, diagnostic validity and stability of this diagnosis. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the prevalence and diagnostic consistency of unspecified psychosis in the outpatient unit.

Methods

Patients diagnosed with the ICD-10 F29 code at the first visit and interviewed at least three times between January 2012–2016 in the Psychiatry Outpatient Clinic were included (n=138). Hospital records were reviewed retrospectively and data were analyzed with SPSS 19th version.

Results

Mean duration of follow-up was 22.8±14.7 months. The diagnoses at the final follow-up were unspecified psychosis (43%), bipolar disorders (18%), schizophrenia (11%), major depression (7%), and anxiety disorders (4%). No significant difference was found between the follow-up diagnoses in terms of age, duration of follow-up, gender, educational status and marital status.

Conclusion

The diagnostic stability of unspecified psychosis is low compared to other psychotic disorders. Follow-up studies with larger sample sizes are required to elucidate the the low diagnostic stability of unspecified psychosis.

Follow-up studies with larger sample sizes are required to elucidate the the low diagnostic stability of unspecified psychosis.

Keywords: Unspecified psychosis, diagnostic stability, diagnosis, psychosis-not-otherwise-specified, psychosis-NOS

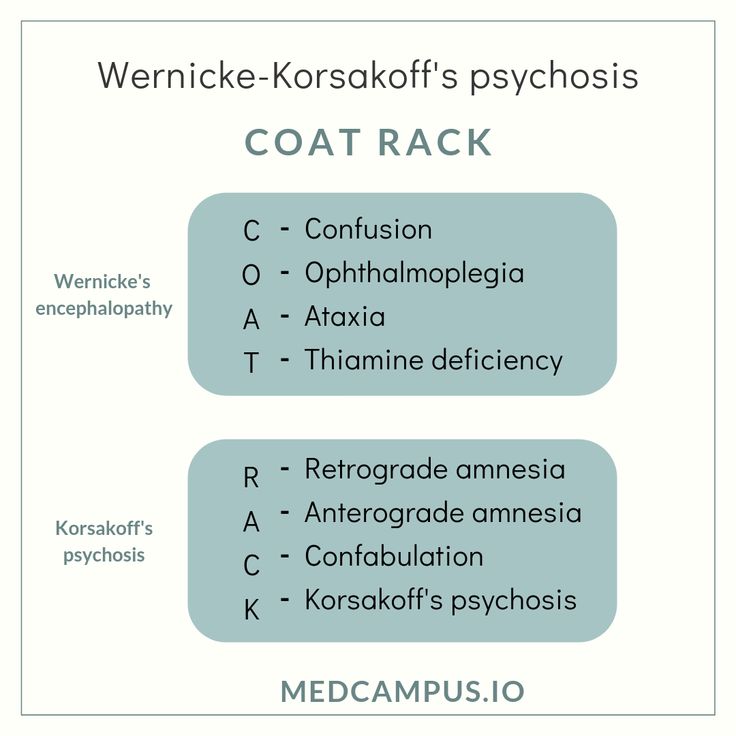

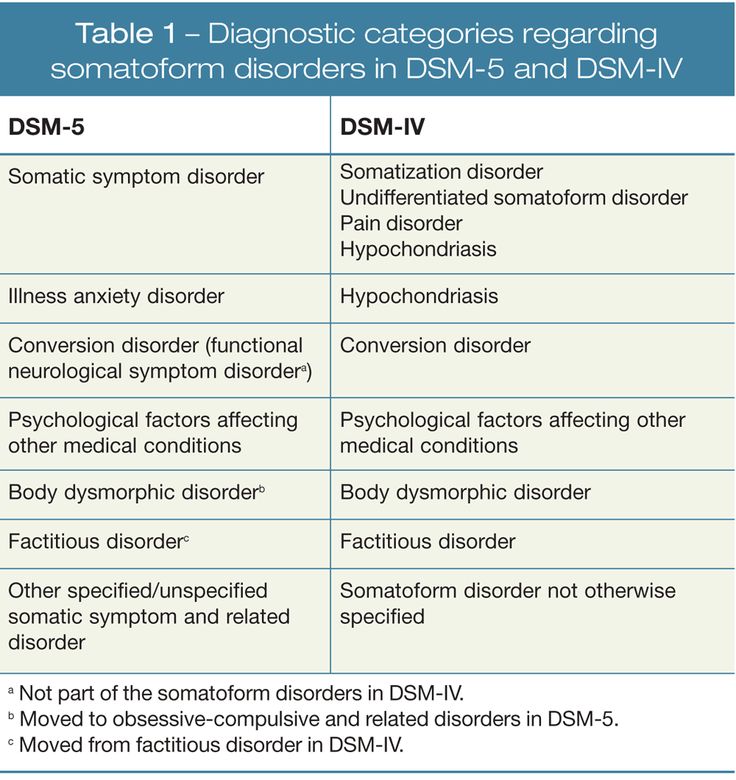

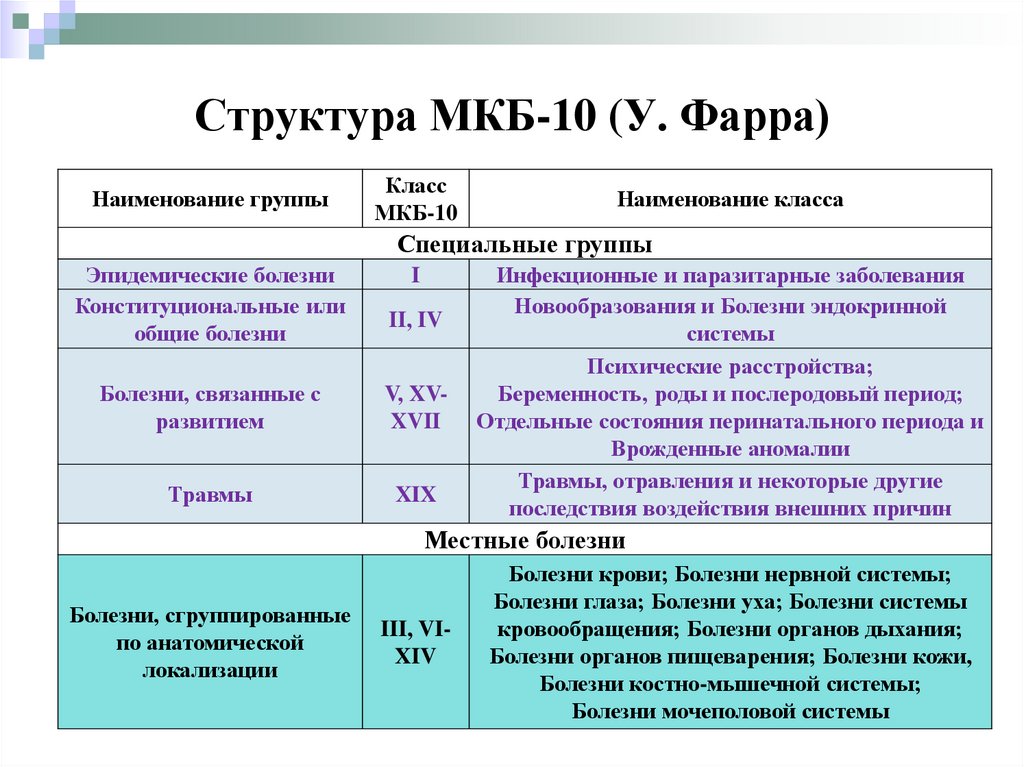

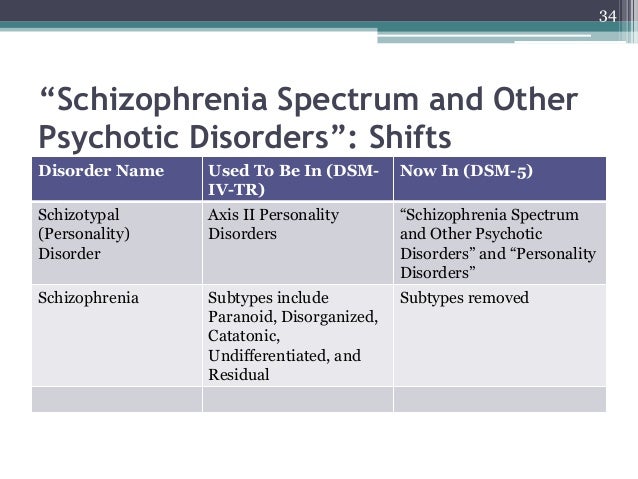

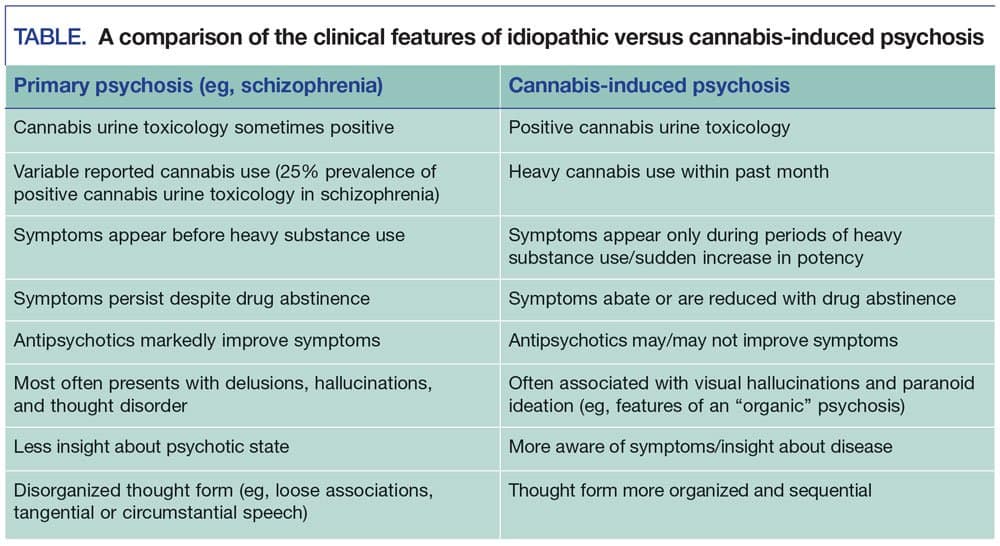

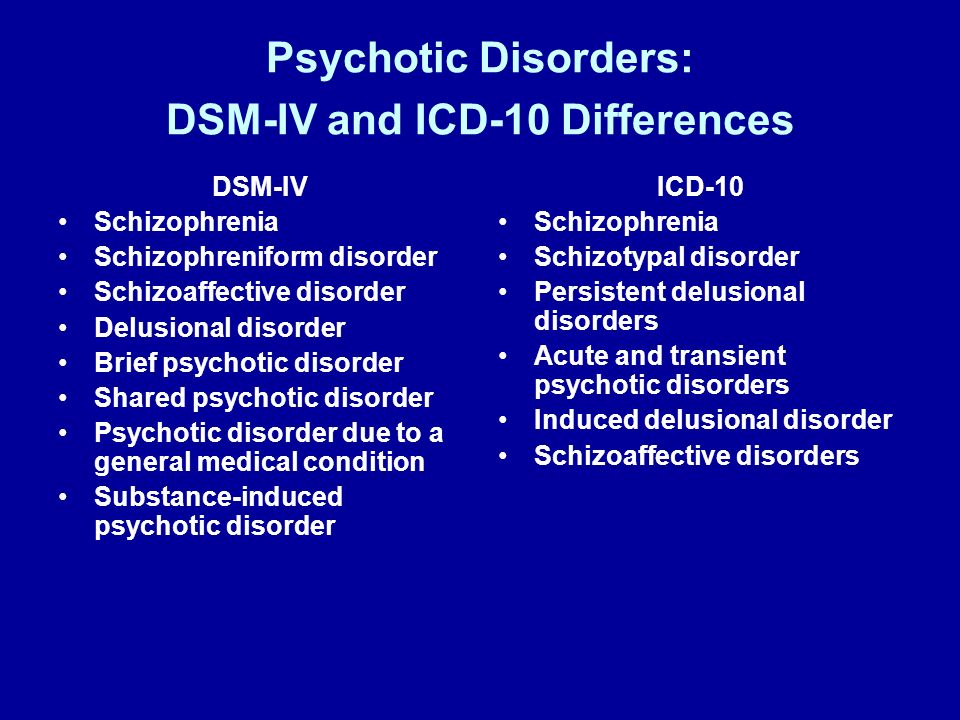

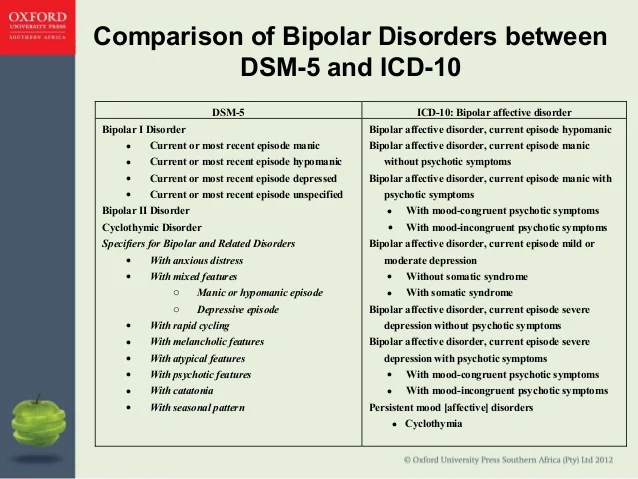

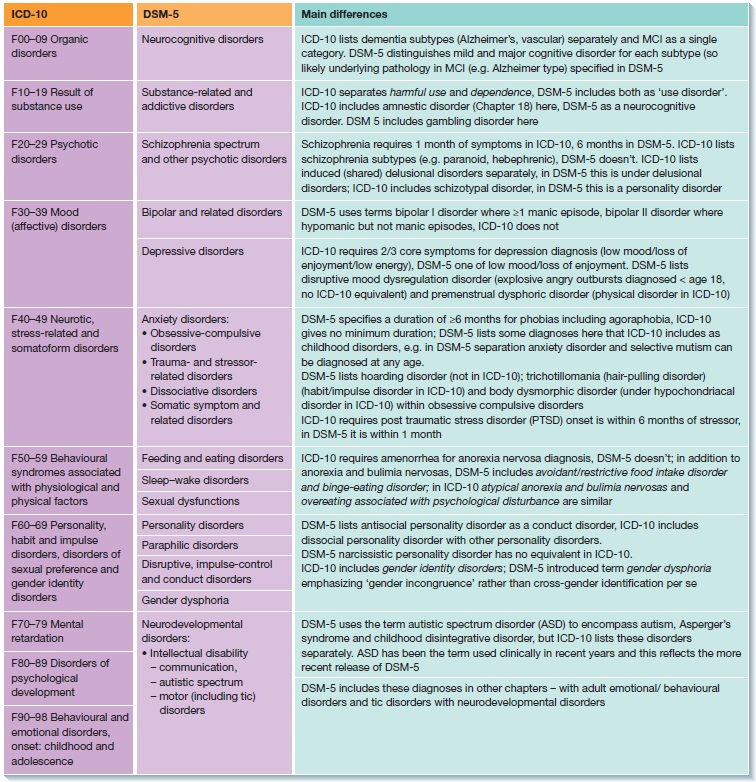

Many studies have been done investigating the insufficiency in the stability and continuity of the diagnoses using the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) of the World Health Organization, the two most commonly used diagnostic systems, categorically and statistically determining diagnostic clusters (1-9). Reasons such as lack of a dimensional evaluation, omission of subthreshold symptoms, gender, the age of onset, substance abuse, and similar characteristics of different disorders may be causes of this deficiency (8,10). Moreover, transient or intermediate diagnoses such as the short psychotic disorder and schizophreniform disorder lead to deterioration in the stability of the diagnoses. Besides, a longitudinal evaluation is needed for the diagnosis of the schizoaffective disorder, and thus, it is challenging to establish this diagnosis at the first interview, which decreases the consistency of the earlier diagnosis (11). “Psychotic Disorder: Not Otherwise Specified” (PD-NOS) according to the DSM IV was included under “Unspecified Scizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorder” in the DSM V, and “F29-Unspecified nonorganic psychosis” (UNP) according to the ICD10. However, this diagnosis is frequently used in cases of contradictory or inadequate information, when the process of the general medical condition is not clear enough, where symptoms change over time, emergency conditions, and in cases where psychotic disorders triggered by substance use cannot be differentiated (13,14). The stability of the diagnosis in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in ICD-10 and DSM-IV for up to four years follow-up was reported to vary between 80% and 100% (15,19). The findings of other psychotic disorder categories are more variable (17,20-22).

Besides, a longitudinal evaluation is needed for the diagnosis of the schizoaffective disorder, and thus, it is challenging to establish this diagnosis at the first interview, which decreases the consistency of the earlier diagnosis (11). “Psychotic Disorder: Not Otherwise Specified” (PD-NOS) according to the DSM IV was included under “Unspecified Scizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorder” in the DSM V, and “F29-Unspecified nonorganic psychosis” (UNP) according to the ICD10. However, this diagnosis is frequently used in cases of contradictory or inadequate information, when the process of the general medical condition is not clear enough, where symptoms change over time, emergency conditions, and in cases where psychotic disorders triggered by substance use cannot be differentiated (13,14). The stability of the diagnosis in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in ICD-10 and DSM-IV for up to four years follow-up was reported to vary between 80% and 100% (15,19). The findings of other psychotic disorder categories are more variable (17,20-22).

The diagnostic stability of patients applying to the clinics with the first psychotic attack was reported as approximately 70% in long-term follow-up studies. In this regard, schizophrenia had the highest diagnostic stability with 90%, while the diagnostic consistency of other psychotic disorders was around 30% (15). In another study (23), the stability of a UNP diagnosis was evaluated as 44% according to ICD-10. In a follow-up study conducted with 500 patients diagnosed with first-episode psychotic disorder, it was observed that the diagnosis of 112 (22.4%) patients had changed two years later. Among the diagnoses with the highest change was the schizophreniform disorder, followed by UNP (17). Diagnostic stability is an important criterion determining the reliability and validity of psychiatric diagnoses and has implications to the clinical practice, where pharmacological as well as psychosocial interventions may vary depending on the diagnosis (3,16).

Validation of the diagnosis over time is particularly crucial for psychotic disorders because they typically have a more chronic course than other psychiatric conditions and require long-term treatment. It is imperial to ensure the diagnostic validity of PD-NOS according to the DSM, or UNP according to ICD and to measure the diagnostic inconsistencies, to optimize the long-term treatments. In light of this information, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between the diagnostic stability and related factors during the follow-up of the patients first-time diagnosed in our clinic.

It is imperial to ensure the diagnostic validity of PD-NOS according to the DSM, or UNP according to ICD and to measure the diagnostic inconsistencies, to optimize the long-term treatments. In light of this information, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between the diagnostic stability and related factors during the follow-up of the patients first-time diagnosed in our clinic.

Sample Selection

This study included cases admitted to the Psychiatry clinics of the Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University Medical Faculty Hospital between January 2012 and January 2016 with a first-time diagnosis of UNP. The study was conducted per the Declaration of Helsinki and has a retrospective and descriptive design. Therefore, ethical committee approval was not found necessary. The inclusion criteria were as follows: at least three visits since the first follow-up date, no relationship of the diagnosis with drug use, and having no psychiatric application before the diagnosis of UNP. At least three previous psychiatric outpatient clinics were considered as the minimum number of interviews in the evaluation of the stability of the diagnosis. Files of a total of 156 cases with a first diagnosis of UNP were retrospectively reviewed. Eighteen patients with less than three psychiatric outpatient visits were excluded from the study.

Files of a total of 156 cases with a first diagnosis of UNP were retrospectively reviewed. Eighteen patients with less than three psychiatric outpatient visits were excluded from the study.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 19.0 (NY, USA) software. Conformity of the variables to the normal distribution was investigated by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, frequency, and percentage values were used in the presentation of descriptive data. Due to skewed data, the relationship between the total number of applicants and the number of people diagnosed with UNP was investigated by the Spearman correlation test. The diagnosis of UNP during the follow-up period was evaluated by the Kaplan Meier analysis. The mean age and follow-up month of the groups were examined by the Kruskal-Wallis Variance Analysis Test. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Socio-demographical Clinical Features of the Sample

The mean age of the 13 patients was 44. 6 ± 15.8 years (min: 19, max: 85). Of the participants, 79 (57.2%) were female, 59 (483.1%) were male, 53 (42.4%) were married, 54 (43.2%) were single, 44 (44.0%) had primary education, 28 (28.0%) were university graduates, and 21 (21.0%) were high school graduates. The mean follow-up period of the patients included was 22.8 ± 14.7 months. Approximately 8% of the patients included in the study applied to the polyclinics thrice. The proportion who applied 3-10 times was 38%, and the percentage of those with ten or more examinations was 44% ().

6 ± 15.8 years (min: 19, max: 85). Of the participants, 79 (57.2%) were female, 59 (483.1%) were male, 53 (42.4%) were married, 54 (43.2%) were single, 44 (44.0%) had primary education, 28 (28.0%) were university graduates, and 21 (21.0%) were high school graduates. The mean follow-up period of the patients included was 22.8 ± 14.7 months. Approximately 8% of the patients included in the study applied to the polyclinics thrice. The proportion who applied 3-10 times was 38%, and the percentage of those with ten or more examinations was 44% ().

Table 1

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

| Variables | Mean ±Standard deviation (min-max) |

|---|---|

| Age (n=138) | 44,6±15,8 (19–85) |

| Sex (n=138) | n (%) |

| Female | 79 (57. 2) 2) |

| Male | 59 (43.1) |

| Marital status (n=125) | |

| Single | 54 (43.2) |

| Married | 53 (42.4) |

| Widow/divorced | 18 (14.4) |

| Educational status (n=100) | |

| Illiterate | 6 (6.0) |

| Literate | 1 (1. 0) 0) |

| Primary school | 44 (44.0) |

| High school | 21 (21.0) |

| University | 28 (28.0) |

| Number of visits (n=138) | |

| 3 times | 11 (8.0) |

| 4–5 times | 24 (17.4) |

| 6–9 times | 43 (31.1) |

| 10 and above | 60 (43. 5) 5) |

Open in a separate window

min: minimum; max: maximum; n: frequency; %, column percentage.

Assessment of Diagnostic Stability

When the diagnosis of the patients in the last application is examined; 59 (42%) were diagnosed with PD-NOS, 25 (18%) had bipolar disorders, 15 (11%) had schizophrenia, 11 (7%) had depressive disorders, and 6 (4%) had anxiety disorders (). When the demographic data were compared according to the definitive diagnosis, no significant difference was found regarding age, duration of follow-up, sex, educational status, and marital status (p=0.929, p=0.126, p=0.840, p=0.117, p=0.895, respectively) ().

Table 2

Psychiatric diagnoses of patients at their last applications

| Diagnosis | n(%) |

|---|---|

| Unspecified psychosis (UNP) | 59 (43) |

| Bipolar disorders | 25 (18) |

| Schizophrenia | 15 (11) |

| Depressive disorders | 11 (8) |

| Anxiety disorders | 6 (4) |

| Other | 22 (16) |

Open in a separate window

n: frequency; %: column percentage.

Table 3

Comparison of demographic data according to outcome diagnoses

| UNP (n=59) | Schizophrenia (n=15) | Mood disorder (n=36) | Other (n=28) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Age | 47.3±16.0 | 46.3±14. 6 6 | 41.1±13.3 | 42.5±18.5 | 0.929 |

| Follow-up (month) | 21.4±151 | 29.4±15.3 | 24.8±13.3 | 19.6±14.5 | 0.187 |

| Sex | p* | ||||

| Female | 36 (61.0) | 9 (60. 0) 0) | 19 (52.8) | 15 (53.6) | 0.840 |

| Male | 23 (39.0) | 6 (40.0) | 17 (47.2) | 13 (46.4) | |

| Educational status | |||||

| Primary school and less | 26 (61.9) | 5 (45.5) | 14 (50. 0) 0) | 6 (31.6) | 0.171 |

| High school and above | 16 (38.1) | 6 (54.5) | 14 (50.0) | 13 (68.4) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 22 (43.1) | 4 (30.8) | 14 (38.9) | 13 (52. 0) 0) | |

| Single | 22 (43.1) | 6 (46.2) | 17 (47.2) | 9 (36.0) | 0.895 |

| Divorced, widowed | 7 (13.8) | 3 (23.1) | 5 (13.9) | 3 (12.0) |

Open in a separate window

UNP: Unspecified psychosis; SD: Standard deviation; p: Kruskal-Wallis variance analysis; p*: Chi-Square Test.

Studies examining the variability of the diagnoses at the first-episodes of UNP are limited. The diagnostic stability was 95% in patients with first-episode psychosis, while the consistency of the diagnosis in patients with a preliminary diagnosis of UNP was reported as 39-44%. 37% of the patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia at the end of the follow-up (23-25). The high stability in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders may reflect the confidence of clinicians in the diagnosis of schizophrenia. In general, the diagnosis of UNP may appear clinically more complicated, especially in cases of insufficient patient information. Hence, the attitudes of physicians can be variable in this clinical complexity. As to our setting, treating physicians could change during the follow-up period. Additionally, factors affecting the diagnostic process such as family attitude could have interfered with the diagnostic continuity.

The diagnostic stability was 95% in patients with first-episode psychosis, while the consistency of the diagnosis in patients with a preliminary diagnosis of UNP was reported as 39-44%. 37% of the patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia at the end of the follow-up (23-25). The high stability in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders may reflect the confidence of clinicians in the diagnosis of schizophrenia. In general, the diagnosis of UNP may appear clinically more complicated, especially in cases of insufficient patient information. Hence, the attitudes of physicians can be variable in this clinical complexity. As to our setting, treating physicians could change during the follow-up period. Additionally, factors affecting the diagnostic process such as family attitude could have interfered with the diagnostic continuity.

The mean age of the patients included in our study was 44.6 ± 15.8. As the studies usually focus on the first episode of psychotic disorders, the probability of observing an early onset age is very high due to the nature of the disease. Therefore, the average age reported in the studies varies between 20 and 30 years. In a study evaluating diagnostic stability, it was reported that the age of onset under 20 years and female gender caused a delay in the diagnosis of the bipolar disorder (7). In a study performed with five hundred patients, it was said that diagnostic consistency decreased significantly with the decreasing age at first diagnosis (17). In our study, the reason for the high mean age can be explained by the fact that unclassified psychotic disorder occurs at any age (3,5,23). One of the essential diagnoses to remember in late-onset psychotic disorders is psychotic disorder associated with the general medical condition (11). Psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition, which may start at later age and can be skipped due to the lack of adequate medical evaluation, was not considered as a final diagnosis in any of our patients.

Therefore, the average age reported in the studies varies between 20 and 30 years. In a study evaluating diagnostic stability, it was reported that the age of onset under 20 years and female gender caused a delay in the diagnosis of the bipolar disorder (7). In a study performed with five hundred patients, it was said that diagnostic consistency decreased significantly with the decreasing age at first diagnosis (17). In our study, the reason for the high mean age can be explained by the fact that unclassified psychotic disorder occurs at any age (3,5,23). One of the essential diagnoses to remember in late-onset psychotic disorders is psychotic disorder associated with the general medical condition (11). Psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition, which may start at later age and can be skipped due to the lack of adequate medical evaluation, was not considered as a final diagnosis in any of our patients.

On the other hand, in the literature on diagnostic consistency, Addington et al. followed 228 cases with a first-episode psychotic disorder for one year and reported the stability of diagnosis as 95% in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and 62% in other psychotic disorders. In 68% of the patients included in the study, the diagnosis did not change, 26% converted to schizophrenia, 4% were associated with affective disorders, and 2% were labeled as another group of psychotic disorders. It was reported that the diagnosis did not change at one-year follow-up in 12 of the 27 patients (44%) who were initially diagnosed with UNP, 10 turned into schizophrenia (37%), and two cases (7%) had developed into mood disorder (23). Schwartz et al. reported that the stability of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression was high in 44% of the patients with schizophrenia, 36% of the patients with schizoaffective disorder, and 27% of the patients with a short psychotic disorder (15).

followed 228 cases with a first-episode psychotic disorder for one year and reported the stability of diagnosis as 95% in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and 62% in other psychotic disorders. In 68% of the patients included in the study, the diagnosis did not change, 26% converted to schizophrenia, 4% were associated with affective disorders, and 2% were labeled as another group of psychotic disorders. It was reported that the diagnosis did not change at one-year follow-up in 12 of the 27 patients (44%) who were initially diagnosed with UNP, 10 turned into schizophrenia (37%), and two cases (7%) had developed into mood disorder (23). Schwartz et al. reported that the stability of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression was high in 44% of the patients with schizophrenia, 36% of the patients with schizoaffective disorder, and 27% of the patients with a short psychotic disorder (15).

Nicolson et al. in a study of 26 children, diagnosed with UNP and followed-up from 2 to 8 years, reported a change in the diagnosis in half of the patients and observed schizoaffective disorder in 12%, bipolar disorder in 15%, and major depressive disorder in 23% of the cases. Most of the children diagnosed with UNP had lost their psychotic symptoms at the end of the follow-up period. High levels of psychopathology, low cognitive capacity and movement disorders at the baseline were associated with poor outcome (26).

Most of the children diagnosed with UNP had lost their psychotic symptoms at the end of the follow-up period. High levels of psychopathology, low cognitive capacity and movement disorders at the baseline were associated with poor outcome (26).

In a meta-analysis conducted in 2016, it was reported that the stability of the first-episode UNP diagnosis was 36%, and the final diagnosis was schizophrenia in 31% of the cases (25). In a study, conducted by Heslin et al., referencing ICD and DSM and evaluating diagnostic stability for eight years, the consistency of the diagnosis of schizophrenia according to DSM was 72.9%, while its stability according to ICD was 75.1%. In the same study, the stability of UNP was 26.7% according to DSM and 25% according to ICD (21). In a study performed with 500 patients, the diagnostic consistency of 66 patients diagnosed as UNP was 51.5%, and among the UNP diagnoses, the highest change was with 28.8% for schizoaffective disorder, followed by 10.6% who changed to mood disorders and 7. 6% who were reported as schizophrenia (17). In studies investigating the diagnostic stability of acute and transient psychotic disorders, it is stated that the diagnostic stability is better in developing countries than in the industrialized countries, and the most common change is towards bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (27).

6% who were reported as schizophrenia (17). In studies investigating the diagnostic stability of acute and transient psychotic disorders, it is stated that the diagnostic stability is better in developing countries than in the industrialized countries, and the most common change is towards bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (27).

Since most studies focus in general on the stability of first-episode psychotic disorders, previous studies are highly limited concerning patients diagnosed with UNP. Therefore, evaluating the stability of the diagnosis of UNP in a larger sample, our study is the first study in this area. Similar to the available literature, in our study, diagnostic stability was achieved in 43% of patients with UNP, and the final diagnoses were bipolar disorder in 18% and schizophrenia in 11% of the patients. In our research, the stability of the UNP diagnosis was consistent with the literature. Contrary to the previous work, the final diagnosis included less schizophrenia and higher bipolar disorder cases. About one-fourth of the cases in our study had mood disorders as the definitive diagnosis. Because of the abundance and details of the phenomena that may occur in the early stages of most psychiatric disorders, the initial diagnosis can be judged as UNP in cases accompanied by a psychotic disorder. The fact that first attacks of mood disorders under age 20 usually have mixed features and a history of impairment of school success and substance abuse precedes the attack, make the differential diagnosis of schizophrenia and mood disorder difficult in young patients. Although the diagnostic process is based on a detailed examination, the definitive diagnosis in these patients is usually the result of follow-up (28). In a study conducted with first-episode psychotic disorder patients, it was reported that diagnostic instability was associated with early onset age, auditory hallucinations, male gender, homicidal behavior, and non-affective psychotic disorder. However, in this study, all first-episode psychotic disorders, including UNP, were included as initial diagnosis, and thus, the relationship of UNP with these factors could not be evaluated (17).

About one-fourth of the cases in our study had mood disorders as the definitive diagnosis. Because of the abundance and details of the phenomena that may occur in the early stages of most psychiatric disorders, the initial diagnosis can be judged as UNP in cases accompanied by a psychotic disorder. The fact that first attacks of mood disorders under age 20 usually have mixed features and a history of impairment of school success and substance abuse precedes the attack, make the differential diagnosis of schizophrenia and mood disorder difficult in young patients. Although the diagnostic process is based on a detailed examination, the definitive diagnosis in these patients is usually the result of follow-up (28). In a study conducted with first-episode psychotic disorder patients, it was reported that diagnostic instability was associated with early onset age, auditory hallucinations, male gender, homicidal behavior, and non-affective psychotic disorder. However, in this study, all first-episode psychotic disorders, including UNP, were included as initial diagnosis, and thus, the relationship of UNP with these factors could not be evaluated (17). Whitty et al. have reported a decline in the diagnostic stability of the first-episode psychotic disorders with a low level of education, the presence of initially medium-severity psychopathology, and the presence of comorbidity with substance and alcohol use (16). On the other hand, in another study that focused on diagnostic stability and change, Haahr et al. assessed patients with the first-episode psychotic disorder, and re-evaluated the diagnoses at the end of one and two years. They reported diagnostic stability as 53% at the end of the first year and 38% at the end of the second year. The same study indicated the stability of schizophrenia diagnosis as 99% at the end of both the first and second year (3). Especially in cases where dimensional assessment is important, more stable diagnoses can be made as a result of reaching new information with frequent assessments and time.

Whitty et al. have reported a decline in the diagnostic stability of the first-episode psychotic disorders with a low level of education, the presence of initially medium-severity psychopathology, and the presence of comorbidity with substance and alcohol use (16). On the other hand, in another study that focused on diagnostic stability and change, Haahr et al. assessed patients with the first-episode psychotic disorder, and re-evaluated the diagnoses at the end of one and two years. They reported diagnostic stability as 53% at the end of the first year and 38% at the end of the second year. The same study indicated the stability of schizophrenia diagnosis as 99% at the end of both the first and second year (3). Especially in cases where dimensional assessment is important, more stable diagnoses can be made as a result of reaching new information with frequent assessments and time.

Our study demonstrated that UNP diagnostic stability was not related to age, gender, follow-up period, educational status, and marital status. In this respect, it can be explained by the fact that our sample was only from one university clinic, and perhaps most importantly, such limitations as the retrospective pattern of our study.

In this respect, it can be explained by the fact that our sample was only from one university clinic, and perhaps most importantly, such limitations as the retrospective pattern of our study.

Limitations

The retrospective pattern of our study is the most significant limitation. Although it may appear to be a limitation that we did not use a measurement tool, all cases were evaluated by a clinician. The fact that the patients were not seen by the same physicians during the four-year follow-up and that the conditions of application (time, the inadequacy of information) were different can be mentioned other limitations of our study. Due to these limitations, follow-up studies with larger sample sizes will be useful to evaluate the stability and validity of the UNP diagnosis.

In our study, it was observed that the diagnoses of 43% of the individuals with first-line psychotic disorder did not change during the follow-up period. Of those with a change in the diagnosis during the follow-up period, 18% were diagnosed with bipolar disorder and 11% with schizophrenia. We determined that the stability of UNP diagnosis was not related to age, gender, follow-up period, educational status, and marital status. Since the diagnosis of UNP is a preferred diagnostic category under emergency conditions, inadequate information about the person, and unsuitable general medical conditions, its stability is lower than other psychotic disorders. Therefore, it is absolutely necessary to reconsider the diagnosis during follow-up. This study has the largest sample size in Turkey and around the world in this diagnostic category. Nevertheless, there is a need for further studies with even larger sample sizes and long-term follow-up, controlling for the variables implicated in this diagnosis.

We determined that the stability of UNP diagnosis was not related to age, gender, follow-up period, educational status, and marital status. Since the diagnosis of UNP is a preferred diagnostic category under emergency conditions, inadequate information about the person, and unsuitable general medical conditions, its stability is lower than other psychotic disorders. Therefore, it is absolutely necessary to reconsider the diagnosis during follow-up. This study has the largest sample size in Turkey and around the world in this diagnostic category. Nevertheless, there is a need for further studies with even larger sample sizes and long-term follow-up, controlling for the variables implicated in this diagnosis.

Oral Presentation: WPA XVII World Congress of Psychiatry, Room R13 Diagnostic and classification, Is unspecified psychosis a stable diagnosis? Berlin, 8-12 October 2017

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethical committee approval was not obtained since retrospective data was screened and evaluated. Our study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the permission was obtained from the institution for the use of the data

Our study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the permission was obtained from the institution for the use of the data

Informed Consent: Hospital records were screened retrospectiveliy. Thus, inform consent was not taken.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept – HİT, KA; Design – HİT, KA; Supervision – KA; Source- MÇ, HİT; Materials – MÇ; Data Collection and/or Processing – MÇ, HİT; Analysis and/or Interpretation – HİT, KA; Literature Search – HİT; Writing Manuscript – HİT; Critical Review – HİT, KA.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

1. Rahm C, Cullberg J. Diagnostic stability over 3 years in a total group of first-episode psychosis patients. Nord J Psychiatry. 2007;61:189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Subramaniam M, Pek E, Verma S, Chan YH, Chong SA. Diagnostic stability 2 years after treatment initiation in the early psychosis intervention programme in Singapore. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41:495–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Haahr U, Friis S, Larsen TK, Melle I, Johannessen JO, Opjordsmoen S, Simonsen E, Rund BR, Vaglum P, McGlashan T. First-episode psychosis:diagnostic stability over one and two years. Psychopathology. 2008;41:322–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Kim JS, Baek JH, Choi JS, Lee D, Kwon JS, Hong KS. Diagnostic stability of first-episode psychosis and predictors of diagnostic shift from non-affective psychosis to bipolar disorder:a retrospective evaluation after recurrence. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Pope MA, Joober R, Malla AK. Diagnostic stability of first-episode psychotic disorders and persistence of comorbid psychiatric disorders over 1 year. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Queirazza F, Semple DM, Lawrie SM. Transition to schizophrenia in acute and transient psychotic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Kessing LV. Diagnostic stability in bipolar disorder in clinical practise as according to ICD-10. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Chen YR, Swann AC, Johnson BA. Stability of diagnosis in bipolar disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Baca-Garcia E, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Basurte-Villamor I, Fernandez del Moral AL, Jimenez-Arriero MA, Gonzalez de Rivera JL, Saiz-Ruiz J, Oquendo MA. Diagnostic stability of psychiatric disorders in clinical practice. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:210–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Sorias S. Psikiyatrik Tanıda Betimsel ve Kategorik Yaklaşımların KısıtlılıklarınıAşmak:Bayes Ağlarına DayalıBir Öneri. Türk Psikiyatri Derg. 2014;26:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Amerikan Psikiyatri Birliği, Ruhsal Bozuklukların Tanısal ve Sayımsal Elkitabı, Beşinci Baskı(DSM-5), TanıÖlçütleri Başvuru Elkitabı'ndan, çev. yay. yön. Köroğlu E, Hekimler Yayın Birliği, Ankara. 2014 [Google Scholar]

yay. yön. Köroğlu E, Hekimler Yayın Birliği, Ankara. 2014 [Google Scholar]

12. World Health Organization, ICD-10 Classification Ment. Behav. Disord. Diagnostic Criteria Res. Geneva. 1993 [Google Scholar]

13. Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. Testing hypotheses about the relationship between cannabis use and psychosis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Mojtabai R, Susser ES, Bromet EJ. Clinical characteristics, 4-year course, and DSM-IV classification of patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:2108–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Schwartz JE, Fennig S, Tanenberg-Karant M, Carlson G, Craig T, Galambos N, Lavelle J, Bromet EJ. Congruence of diagnoses 2 years after a first-admission diagnosis of psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:593–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Whitty P, Clarke M, McTigue O, Browne S, Kamali M, Larkin C, O'Callaghan E. Diagnostic stability four years after a first episode of psychosis. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1084–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1084–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Salvatore P, Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, Khalsa HM, Sanchez-Toledo JP, Zarate CA, Jr, Vieta E, Maggini C. The McLean-Harvard International First Episode Project:two-year stability of DSM-IV diagnoses in 500 first-episode psychotic disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:183–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Baldwin P, Browne D, Scully PJ, Quinn JF, Morgan MG, Kinsella A, Owens JM, Russell V, O'Callaghan E, Waddington JL. Epidemiology of first-episode psychosis:illustrating the challenges across diagnostic boundaries through the Cavan-Monaghan study at 8 years. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:624–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Veen ND, Selten JP, Schols D, Laan W, Hoek HW, van der Tweel I, Kahn RS. Diagnostic stability in a Dutch psychosis incidence cohort. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:460–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Schimmelmann BG, Conus P, Edwards J, McGorry PD, Lambert M. Diagnostic stability 18 months after treatment initiation for first-episode psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1239–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Diagnostic stability 18 months after treatment initiation for first-episode psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1239–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Heslin M, Lomas B, Lappin JM, Donoghue K, Reininghaus U, Onyejiaka A, Crudace T, Jones PB, Murray RM, Fearon P, Dazzan P, Morgan C, Doody GA. Diagnostic change 10 years after a first episode of psychosis. Psychol Med. 2015;45:2757–2769. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Bromet EJ, Kotov R, Fochtmann LJ, Carlson GA, Tanenberg-Karant M, Ruggero C, Chang SW. Diagnostic shifts during the decade following first admission for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1186–1194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Addington J, Chaves A, Addington D. Diagnostic stability over one year in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2006;86:71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Castagnini A, Bertelsen A, Berrios GE. Incidence and diagnostic stability of ICD-10 acute and transient psychotic disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2008;49:255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Fusar-Poli P, Cappucciati M, Rutigliano G, Heslin M, Stahl D, Brittenden Z, Caverzasi E, McGuire P, Carpenter WT. Diagnostic stability of ICD/DSM first episode psychosis diagnoses:meta-analysis. Schizopr Bull. 2016;42:1395–1406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Nicolson R, Lenane M, Brookner F, Gochman P, Kumra S, Spechler L, Giedd JN, Thaker GK, Wudarsky M, Rapoport JL. Children and adolescents with psychotic disorder not otherwise specified:a 2- to 8-year follow-up study. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:319–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Aadamsoo K, Saluveer E, Küünarpuu H, Vasar V, Maron E. Diagnostic stability over 2 years in patients with acute and transient psychotic disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65:381–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Haldun S, Köksal A, Cem A, Hasan H. Şizofreni ve Diğer Psikotik Bozukluklar. Türkiye Psikiyatri Derneği Bilimsel Çalışma Birimleri Dizisi - No:6. Ekim 2007, Ankara [Google Scholar]

Journal "Psychiatry" №2 2003

editorial

Biological psychiatry at the Scientific Center for Mental Health of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences (to the 20th anniversary of the Center)

Tiganov A. S.

S.

clinical psychiatry

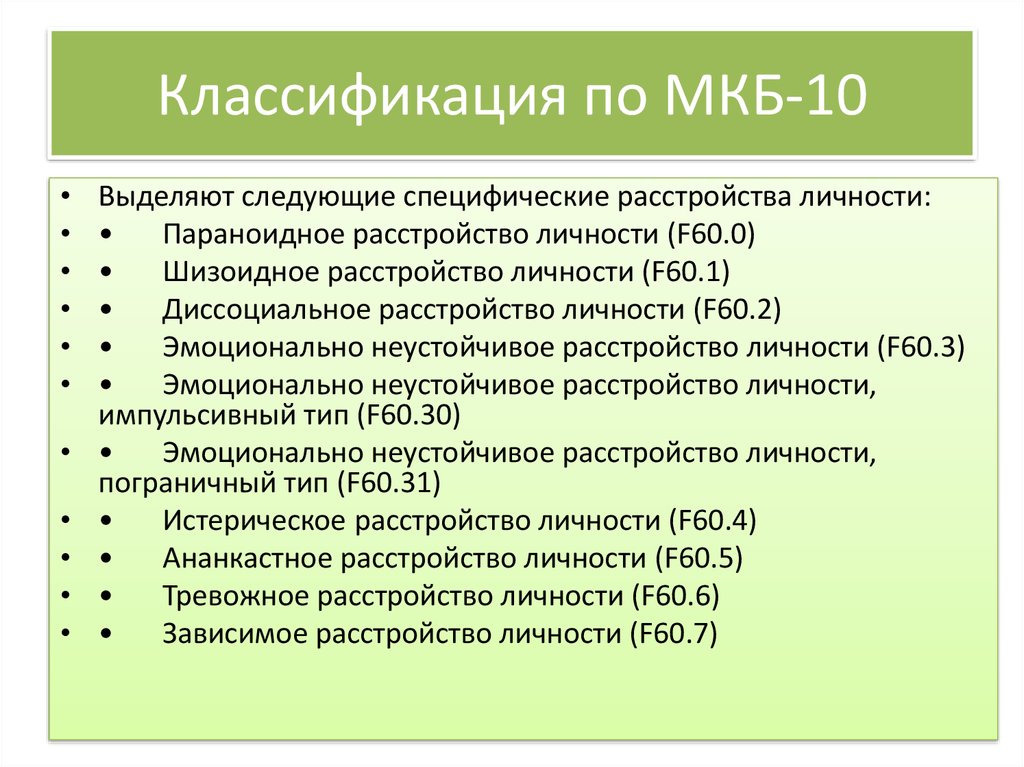

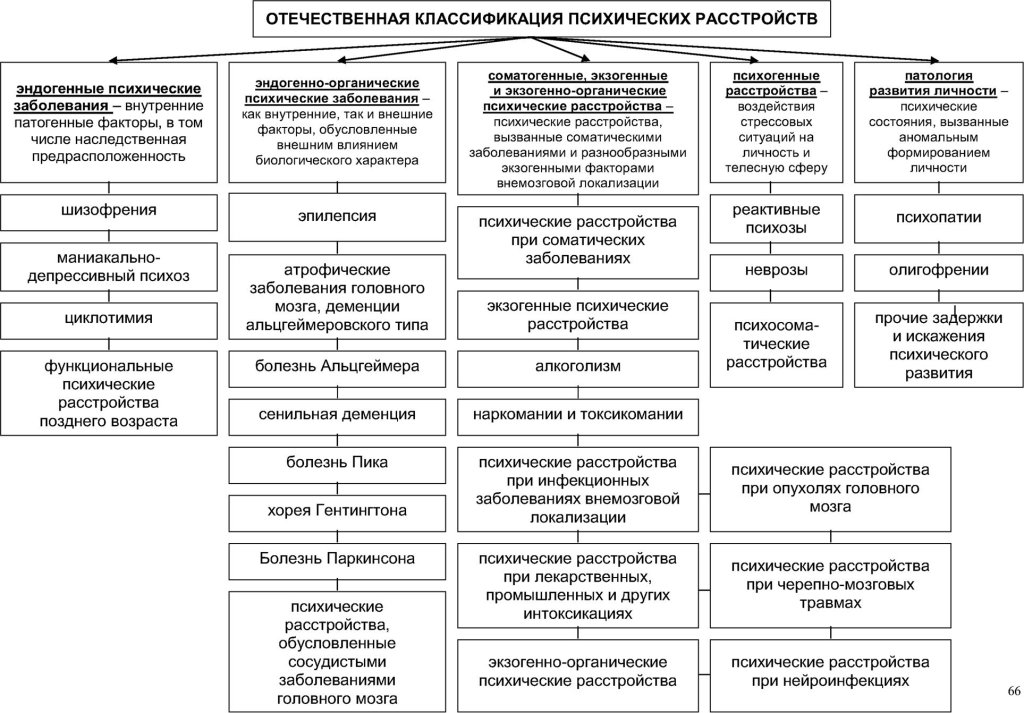

Endogenous mental illness in the version of the International Classification of Diseases of the Tenth Revision (ICD-10) adapted for use in the Russian Federation1

Tiganov A.S., Panteleeva G.P., Tsutsulkovskaya M.Ya.

The article continues the discussion of modern approaches to the classification of endogenous mental illnesses — schizophrenia and schizoaffective psychosis — in domestic clinical psychiatry and diagnostic criteria for their assessment used in coding in the version of ICD-10 adapted for Russia. Additions to the official adapted version are proposed, clarifying the diagnostic assessment of the forms of the course of schizophrenia and schizoaffective psychosis and their systematics in the practical use of the ICD-10.

The article continues the discussion of up-to-date approaches to the classification of endogenous mental diseases — schizophrenia and schizoaffective psychosis — in the Russian clinical psychiatry and diagnostic criteria for their evaluation applied during the coding for the ICD-10 adapted for Russia. It suggests certain addenda to the official adapted version specifying the diagnostic evaluation of forms of the course of schizophrenia and schizoaffective psychosis and their systematization in the practical application of the ICD-10.

It suggests certain addenda to the official adapted version specifying the diagnostic evaluation of forms of the course of schizophrenia and schizoaffective psychosis and their systematization in the practical application of the ICD-10.

The place of the pathopsychological method in the nosological diagnosis of the first depressive episodes in adolescence

Zvereva N.V., Goryunov A.V.

In order to establish the pathopsychological features of the first depressive conditions in adolescents and their diagnostic significance, 37 patients aged 10 to 15 years were examined, which comprised three clinical groups: the first with depressive episodes within schizophrenia (F20; F21), the second with affective disorder (F32; F33), the third group includes patients with a differential diagnosis between schizophrenia and affective disorder. Differences in these groups were revealed in terms of indicators reflecting the features of impaired thinking, arbitrary auditory memory and self-esteem, and their dynamics during therapy. The expediency of using the pathopsychological method for differential diagnostic and prognostic purposes in the study of adolescent depression has been established.

The expediency of using the pathopsychological method for differential diagnostic and prognostic purposes in the study of adolescent depression has been established.

In order to determine the pathopsychological features of early depressions in teenagers and their diagnostic value, we studied 37 patients at the age of 10-15, who made up three clinical groups: the first one — with depressive occurrences within the framework of schizophrenia (F20 ; F21), the second one - with affective disorders (F32; F33), and the third one - patients with a differential diagnosis ranging from schizophrenia to an affective disorder. We revealed the differences between the groups according to indices reflecting the particular features of impaired thinking, arbitrary aural and vocal memory and self-appraisal, and their dynamics in the process of treatment. We also established the expediency of using the pathopsychological method for differential and diagnostic as well as prognostic purposes in studying juvenile depressions.

Pathology of drives in schizophrenia and residual organic lesions of the central nervous system in children and adolescents (comparative age aspect)

Luss L.A.

In order to determine the features of the pathology of drives and to establish their comparative age and nosological differences in psychopathic-like schizophrenia and residual organic lesions of the CNS (ROC CNS), 111 patients aged 7 to 18 years were examined. In patients with schizophrenia (68 people), a pronounced polymorphism of disturbed drives was found with a predominance of aggressive-sadistic, disinhibited sexual drives and drives to vagrancy. In patients with ROP CNS (43 people), there was a predominance of aggressive-sadistic drives and the drive to steal, with a lower prevalence of other options. Age differences in phenomenological manifestations and psychopathological qualities of the studied pathology were revealed in both clinical groups. In particular, a certain influence of the age factor on the clinic of disturbed drives has been established: the younger the age, the more pronounced the psychopathological incompleteness, the fragmentation of the disturbed drives, the inability to separate the drive from one's own personality, which causes the egosintonity of these disorders. Among the studied patients, psychopathologically incomplete forms of pathological inclinations predominated, while impulsive and obsessive inclinations occurred mainly already in adolescence. Age-specific features of the formation of disturbed drives, observed in the "socialized forms" of this pathology, were revealed.

In particular, a certain influence of the age factor on the clinic of disturbed drives has been established: the younger the age, the more pronounced the psychopathological incompleteness, the fragmentation of the disturbed drives, the inability to separate the drive from one's own personality, which causes the egosintonity of these disorders. Among the studied patients, psychopathologically incomplete forms of pathological inclinations predominated, while impulsive and obsessive inclinations occurred mainly already in adolescence. Age-specific features of the formation of disturbed drives, observed in the "socialized forms" of this pathology, were revealed.

111 patients at the age from 7 to 18 were examined in order to determine the particular features of drive pathology as well as their comparative, age-specific and nosological differences in case of psychopathy-like schizophrenia and residual-organic CNS"s affection ( CNS's ROA). Evident polymorphism of abnormal drives with the prevalence of aggressive-sadistic, disinhibited sexual drives and inclinations to vagrancy was revealed in patients with schizophrenia (68 people). Prevalence of aggressive-sadistic drives as well as the inclination to stealing with the smaller prevalence of other variants was recorded in patients with CNS's ROA (43 people). Age-specific differences of phenomenological manifestations and psychopathological properties of the examined pathology were discovered in both clinical groups. drives and own personality that determines egosyntonicity of the above-mentioned disorders are. specific features of the formation of abnormal drives observed in “socialize d forms” of the above-mentioned pathology were discovered.

Prevalence of aggressive-sadistic drives as well as the inclination to stealing with the smaller prevalence of other variants was recorded in patients with CNS's ROA (43 people). Age-specific differences of phenomenological manifestations and psychopathological properties of the examined pathology were discovered in both clinical groups. drives and own personality that determines egosyntonicity of the above-mentioned disorders are. specific features of the formation of abnormal drives observed in “socialize d forms” of the above-mentioned pathology were discovered.

mental health treatment

Experience in the treatment of delusional and hallucinatory psychoses with seroquel in elderly people

Kontsevoi V.A., Medvedev A.V., Safarova T.P.

The effectiveness and safety of short-term (6 weeks) therapy with seroquel for delusional and hallucinatory-delusional psychoses was studied in 18 patients aged 60 years and older with schizophrenia (n=10), persistent delusional disorder (n=4) and schizoaffective psychosis (n=4). ). In most cases, a reduction of psychotic symptoms by at least 50% was noted. Seroquel most effectively affected late-developing psychoses with relatively short periods of the disease. He also found a reducing effect on the phenomena of cognitive weakness that occurred in a number of patients. Of the side effects, drowsiness, muscle weakness and orthostatic phenomena were noted, which can be significant only in isolated cases. At the same time, the drug has a reducing effect on the phenomena of parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia caused by traditional antipsychotics.

). In most cases, a reduction of psychotic symptoms by at least 50% was noted. Seroquel most effectively affected late-developing psychoses with relatively short periods of the disease. He also found a reducing effect on the phenomena of cognitive weakness that occurred in a number of patients. Of the side effects, drowsiness, muscle weakness and orthostatic phenomena were noted, which can be significant only in isolated cases. At the same time, the drug has a reducing effect on the phenomena of parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia caused by traditional antipsychotics.

There was a study of the efficiency and safety of a short-term (six-week) Seroquel treatment of delirious and hallucinatory-delirious psychoses in 18 patients at the age of 60 and older suffering from schizophrenia (n=10), persistent delirious disorder (n=4) and schizoaffective psychosis (n=4). In most cases there was a reduction of psychotic symptoms by at least 50%. Seroquel had the most positive effect on psychoses of late development with relatively short terms of the disease. It also showed a reducing effect on the occurrences of cognitive impotence present in a number of the patients. The side effects were hypersomnia, muscle weakness and orthostatic occurrences, which can be considerable only in single cases. At the same time, the preparation had a reducing effect on the occurrences of parkinsonism and late dyskinesia caused by traditional neuroleptics.

It also showed a reducing effect on the occurrences of cognitive impotence present in a number of the patients. The side effects were hypersomnia, muscle weakness and orthostatic occurrences, which can be considerable only in single cases. At the same time, the preparation had a reducing effect on the occurrences of parkinsonism and late dyskinesia caused by traditional neuroleptics.

Therapeutic response to drugs with different mechanisms of action in Alzheimer's disease

Selezneva N.D.

The variety of psychopathological manifestations of Alzheimer's disease, due to the presence of different clinical forms of the disease, the structure of the dementia syndrome and its severity, requires a differentiated drug effect. A comparative analysis of the effectiveness of three drugs with different mechanisms of action was carried out - cholinergic, glutamatergic and neuroprotective. 120 patients received course treatment with amyridine, 106 patients with akatinol memantine, and 9 patients with cerebrolysin. 6 patients. The comparability of the results of the analysis was ensured by the homogeneity of the therapeutic cohorts in terms of the main clinical parameters, demographic indicators, and genotypic (ApoE4+/ApoE4-) distribution. Differentiated indications for the choice of pharmacotherapy in patients with Alzheimer's disease were determined.

6 patients. The comparability of the results of the analysis was ensured by the homogeneity of the therapeutic cohorts in terms of the main clinical parameters, demographic indicators, and genotypic (ApoE4+/ApoE4-) distribution. Differentiated indications for the choice of pharmacotherapy in patients with Alzheimer's disease were determined.

The variety of psychopathological manifestations of Alzheimer's disease determined by the presence of different clinical forms of the disease as well as the structure of dementia syndrome and its severity requires a differential drug intervention. There was a comparative efficiency analysis of three preparations with different mechanisms of their action, namely of cholinergic, glutamatergic and neuroprotective actions.6 patients were treated with Cerebrolysin. The homogeneity of therapeutic cohorts by basic clinical parameters, demographic indices and genotypic (ApoE4+/ApoE4-) distribution ensured the comparability of the analysis results. Differential indications for the selection of a pharmacotherapy for patients with Alzheimer's disease were determined.

Differential indications for the selection of a pharmacotherapy for patients with Alzheimer's disease were determined.

scientific reviews

Dysthymia: history of the problem, age aspects

Siranchiev M.A.

book reviews, reviews, reviews

Review of the monograph by D.N. Isaeva "Psychopathology of childhood"

Kozlova I.A.

Review of the book "Schizophrenia" by A. Weitzman, M. Poyarovsky, V. Tal

Oleichik I.V.

anniversaries

To the anniversary of A.K. Anufrieva

our legacy

On the concepts of "latent" and "residual" in schizophrenia

Anufriev A.K.

Borderline psychiatric disorders as milestones of delimitation of state, reactions and illness in psychiatric practice

Anufriev A. K.

K.

current information

WHO Workshop

Yastrebov V.S., Mikhailova N.I., Stepanova A.F.

International Conference of Public Organizations in Psychiatry

Solokhina T.A.

PKB No. 5 - Reactive States

State Budgetary Institution of Healthcare of the City of Moscow

Psychiatric Clinical Hospital No. 5 of the Department of Health of the City of Moscow

+7 (495) 445-55-25) +7 (495) 724-33-33

Moscow region, Chekhov, s. Troitskoye, 5

Medical Tourism

Site search

Reactive states are a special group of mental disorders (psychogeny) that develop as a result of a psychic trauma and reflect the content of a traumatic event.

This is an attempt to adapt the psyche (including the normal one) to extreme stresses.

In the current International Classification of Diseases of the Tenth Revision, there is no separate heading devoted to psychogenies, they are, as it were, scattered across different blocks of the ICD-10.

The prevalence of reactive psychoses in the population remains to be determined. Women are known to be affected about twice as often as men. Reactive depressions account for 40-50% of all reactive psychoses.

In our practice, we often encounter the following diagnoses: “Depressive episode”; "Mixed Emotional and Behavioral Disorder Due to Adjustment Disorder".

Patients with psychogenic illness tend to focus on an internal reliving of a recent misfortune. These experiences are overvalued for them. But in typical cases, they do not want to discuss what happened with strangers (in particular, with psychiatrists). On the contrary, with appropriate questions, patients become isolated, they may stop talking altogether. The mood is lowered, with ideas of self-blame. Sometimes outwardly accusatory tendencies prevail. There is often anxiety. Some patients have a reactive paranoid - there is fear, suspicion, thoughts of persecution, possible murder. Mental disorders that occur in a reactive state are not easy to distinguish from set behavior, when, for one reason or another, it seems to the patient that it is beneficial to simulate a mental illness. According to our observations, the installation behavior can be combined with real symptoms.

The mood is lowered, with ideas of self-blame. Sometimes outwardly accusatory tendencies prevail. There is often anxiety. Some patients have a reactive paranoid - there is fear, suspicion, thoughts of persecution, possible murder. Mental disorders that occur in a reactive state are not easy to distinguish from set behavior, when, for one reason or another, it seems to the patient that it is beneficial to simulate a mental illness. According to our observations, the installation behavior can be combined with real symptoms.

In the Clinical Clinical Hospital No. 5 of the Moscow Department of Health, the patient is usually in a reactive state until recovery from a temporary painful disorder. He's on his way to us, under investigation on suspicion of wrongdoing. Behind him is a forensic psychiatric examination, at which it was impossible to resolve the issue of his sanity precisely because of the reactive state, and this, in turn, is a consequence of the stress from the forensic investigative situation. In addition, one should not forget about the stress that a person experienced during a socially dangerous act (whether it was committed by him or someone else).

In addition, one should not forget about the stress that a person experienced during a socially dangerous act (whether it was committed by him or someone else).

Treatment in almost all cases includes antidepressants, if necessary, neuroleptics are included. Psychotherapy can help such patients, but there are significant difficulties in its implementation, due to the installation behavior.

The prognosis is usually favorable. Within a relatively short period of time (usually within a few months), the psychogenic disorder is leveled, although this process is not always smooth. Rather, we have to talk about undulating attenuation with returns of symptoms.

It should be remembered that reactive states occur not only against the background of health, but also in patients suffering from chronic mental illness. In this case, the main psychopathological process can influence the clinical picture. But in many cases, psychogeny obscures the characteristic manifestations of schizophrenia or other long-term mental illness.