I talk to myself in my head

Why Do I Talk To Myself? Causes and When to Worry

Do you talk to yourself? We mean out loud, not just under your breath or in your head — pretty much everyone does that.

This habit often begins in childhood, and it can become second nature pretty easily. Even if you don’t see anything wrong with talking to yourself (and you shouldn’t!), you might wonder what others think, especially if you often catch yourself musing aloud at work or in the grocery store.

If you’re worried this habit is a little strange, you can rest easy. Talking to yourself is normal, even if you do it often. If you’d like to be more mindful around talking to yourself so you can avoid doing it in specific situations, we have some tips that can help.

Beyond being a perfectly normal habit, private or self-directed speech (scientific terms for talking to yourself) can actually benefit you in a number of ways.

It can help you find things

You just completed an impressive shopping list. Congratulating yourself on remembering everything you need for the next week or so, you get ready to head out to the store. But where did you leave the list? You wander through the house searching, muttering, “shopping list, shopping list.”

Of course, your list can’t respond. But according to 2012 research, saying the name of whatever you’re looking for out loud can help you locate it more easily than simply thinking about the item.

The authors suggest this works because hearing the name of the item reminds your brain what you’re looking for. This helps you visualize it and notice it more easily.

It can help you stay focused

Think back to the last time you did something difficult.

Maybe you built your bed by yourself, even though the instructions clearly said it was a two-person job. Or perhaps you had to take on the extremely technical task of repairing your computer.

You may have vented some frustration with a few exclamations (even expletives). You probably also talked yourself through the toughest parts, maybe even reminded yourself of your progress when you felt like giving up. In the end, you succeeded, and talking to yourself may have helped.

You probably also talked yourself through the toughest parts, maybe even reminded yourself of your progress when you felt like giving up. In the end, you succeeded, and talking to yourself may have helped.

Explaining processes to yourself aloud can help you see solutions and work through problems, since it helps you focus on each step.

Asking yourself questions, even simple or rhetorical ones —”If I put this piece here, what happens?” can also help you concentrate on the task at hand.

It can help motivate you

When you feel stuck or otherwise challenged, a little positive self-talk can do wonders for your motivation.

These words of encouragement usually have more weight when you say them aloud rather than simply think them. Hearing something often helps reinforce it, after all.

There’s one big thing to keep in mind, though. Research from 2014 suggests this type of self-motivation works best when you talk to yourself in the second or third person.

In other words, you don’t say, “I can absolutely do this.” Instead, you refer to yourself by name or say something like, “You’re doing great. You’ve got so much done already. Just a little bit more.”

When you refer to yourself with second- or third-person pronouns, it can seem like you’re speaking to another person. This can provide some emotional distance in situations where you feel stressed and help relieve distress associated with the task.

It can help you process difficult feelings

If you’re grappling with difficult emotions, talking through them can help you explore them more carefully.

Some emotions and experiences are so deeply personal that you might not feel up to sharing them with anyone, even a trusted love one, until you’ve done a little work with them first.

Taking some time to sit with these emotions can help you unpack them and separate potential worries from more realistic concerns. While you can do this in your head or on paper, saying things aloud can help ground them in reality.

It can also make them less upsetting. Simply giving voice to unwanted thoughts brings them out into the light of day, where they often seem more manageable. Voicing emotions also helps you validate and come to terms with them. This can, in turn, diminish their impact.

By now, you probably feel a little better about talking to yourself. And self-talk certainly can be a powerful tool for boosting mental health and cognitive function.

Like all tools, though, you’ll want to use it correctly. These tips can help you maximize the benefits of self-directed speech.

Positive words only

Though self-criticism may seem like a good option for holding yourself accountable and staying on track, it usually doesn’t work as intended.

Blaming yourself for unwanted outcomes or speaking to yourself harshly can affect your motivation and self-confidence, which won’t do you any favors.

There’s good news, though: Reframing negative self-talk can help. Even if you haven’t yet succeeded at your goal, acknowledge the work you’ve already done and praise your efforts.

Instead of saying: “You’re not trying hard enough. You’ll never get this done.”

Try: “You’ve put a lot of effort into this. It’s taking a long time, true, but you can definitely get it done. Just keep going a little longer.”

Question yourself

When you want to learn more about something, what do you do?

You ask questions, right?

Asking yourself a question you can’t answer won’t magically help you find the correct response, of course. It can help you take a second look at whatever you’re trying to do or want to understand. This can help you figure out your next step.

In some cases, you might actually know the answer, even if you don’t realize it. When you ask yourself “What might help here?” or “What does this mean?” try answering your own question (this can have particular benefit if you’re trying to grasp new material).

If you can give yourself a satisfactory explanation, you probably do understand what’s going on.

Pay attention

Talking to yourself, especially when stressed or trying to figure something out, can help you examine your feelings and knowledge of the situation. But this won’t do much good if you don’t actually listen to what you have to say.

But this won’t do much good if you don’t actually listen to what you have to say.

You know yourself better than anyone else does, so try to tune in to this awareness when you feel stuck, upset, or uncertain. This can help you recognize any patterns contributing to distress.

Don’t be afraid to talk through difficult or unwanted feelings. They might seem scary, but remember, you’re always safe with yourself.

Avoid first person

Affirmations can be a great way to motivate yourself and boost positivity, but don’t forget to stick with second person.

Mantras like “I am strong,” “I am loved,” and “I can face my fears today” can all help you feel more confident.

When you phrase them as if you’re speaking to someone else, you might have an easier time believing them. This can really make a difference if you struggle with self-compassion and want to improve self-esteem.

So try instead: “You are strong,” “You are loved,” or “You can face your fears today. ”

”

Again, there’s nothing at all wrong with talking to yourself. If you do it regularly at work or other places where it could disrupt others, you might wonder how you can break this habit or at least scale it back a bit.

Keep a journal

Talking to yourself can help you work through problems, but so can journaling.

Writing down thoughts, emotions, or anything you want to explore can help you brainstorm potential solutions and keep track of what you’ve already tried.

What’s more, writing things down allows you to look over them again later.

Keep your journal with you and pull it out when you have thoughts you need to explore.

Ask other people questions instead

Maybe you tend to talk yourself through challenges when you get stuck at school or work. The people around you can also help.

Instead of trying to puzzle something out yourself, consider chatting to a co-worker or classmate instead. Two heads are better than one, or so the saying goes. You might even make a new friend.

You might even make a new friend.

Distract your mouth

If you really need to keep quiet (say you’re in the library or a quiet workspace), you might try chewing gum or sucking on hard candy. Having to talk around something in your mouth can remind you not to say anything out loud, so you might have more success keeping your self-talk in your thoughts.

Another good option is to carry a drink with you and take a sip whenever you open your mouth to say something to yourself.

Remember that it’s very common

If you slip up, try not to feel embarrassed. Even if you don’t notice it, most people do talk to themselves, at least occasionally.

Brushing off your self-talk with a casual, “Oh, just trying to stay on task,” or “Searching for my notes!” can help normalize it.

Some people wonder if frequently talking to themselves suggests they have an underlying mental health condition, but this usually isn’t the case.

While people with conditions that affect psychosis such as schizophrenia may appear to talk to themselves, this generally happens as a result of auditory hallucinations. In other words, they often aren’t talking to themselves, but replying to a voice only they can hear.

In other words, they often aren’t talking to themselves, but replying to a voice only they can hear.

If you hear voices or experience other hallucinations, it’s best to seek professional support right away. A trained therapist can offer compassionate guidance and help you explore potential causes of these symptoms.

A therapist can also offer support if you:

- want to stop talking to yourself but can’t break the habit on your own

- feel distressed or uncomfortable about talking to yourself

- experience bullying or another stigma because you talk to yourself

- notice you mostly talk down to yourself

Have a habit of running through your evening plans aloud while walking your dog? Feel free to keep at it! There’s nothing strange or unusual about talking to yourself.

If self-talk inconveniences you or causes other problems, a therapist can help you explore strategies to get more comfortable with it or even break the habit, if you choose.

Crystal Raypole has previously worked as a writer and editor for GoodTherapy. Her fields of interest include Asian languages and literature, Japanese translation, cooking, natural sciences, sex positivity, and mental health. In particular, she’s committed to helping decrease stigma around mental health issues.

Why Do I Talk To Myself? Causes and When to Worry

Do you talk to yourself? We mean out loud, not just under your breath or in your head — pretty much everyone does that.

This habit often begins in childhood, and it can become second nature pretty easily. Even if you don’t see anything wrong with talking to yourself (and you shouldn’t!), you might wonder what others think, especially if you often catch yourself musing aloud at work or in the grocery store.

If you’re worried this habit is a little strange, you can rest easy. Talking to yourself is normal, even if you do it often. If you’d like to be more mindful around talking to yourself so you can avoid doing it in specific situations, we have some tips that can help.

Beyond being a perfectly normal habit, private or self-directed speech (scientific terms for talking to yourself) can actually benefit you in a number of ways.

It can help you find things

You just completed an impressive shopping list. Congratulating yourself on remembering everything you need for the next week or so, you get ready to head out to the store. But where did you leave the list? You wander through the house searching, muttering, “shopping list, shopping list.”

Of course, your list can’t respond. But according to 2012 research, saying the name of whatever you’re looking for out loud can help you locate it more easily than simply thinking about the item.

The authors suggest this works because hearing the name of the item reminds your brain what you’re looking for. This helps you visualize it and notice it more easily.

It can help you stay focused

Think back to the last time you did something difficult.

Maybe you built your bed by yourself, even though the instructions clearly said it was a two-person job. Or perhaps you had to take on the extremely technical task of repairing your computer.

Or perhaps you had to take on the extremely technical task of repairing your computer.

You may have vented some frustration with a few exclamations (even expletives). You probably also talked yourself through the toughest parts, maybe even reminded yourself of your progress when you felt like giving up. In the end, you succeeded, and talking to yourself may have helped.

Explaining processes to yourself aloud can help you see solutions and work through problems, since it helps you focus on each step.

Asking yourself questions, even simple or rhetorical ones —”If I put this piece here, what happens?” can also help you concentrate on the task at hand.

It can help motivate you

When you feel stuck or otherwise challenged, a little positive self-talk can do wonders for your motivation.

These words of encouragement usually have more weight when you say them aloud rather than simply think them. Hearing something often helps reinforce it, after all.

There’s one big thing to keep in mind, though. Research from 2014 suggests this type of self-motivation works best when you talk to yourself in the second or third person.

Research from 2014 suggests this type of self-motivation works best when you talk to yourself in the second or third person.

In other words, you don’t say, “I can absolutely do this.” Instead, you refer to yourself by name or say something like, “You’re doing great. You’ve got so much done already. Just a little bit more.”

When you refer to yourself with second- or third-person pronouns, it can seem like you’re speaking to another person. This can provide some emotional distance in situations where you feel stressed and help relieve distress associated with the task.

It can help you process difficult feelings

If you’re grappling with difficult emotions, talking through them can help you explore them more carefully.

Some emotions and experiences are so deeply personal that you might not feel up to sharing them with anyone, even a trusted love one, until you’ve done a little work with them first.

Taking some time to sit with these emotions can help you unpack them and separate potential worries from more realistic concerns. While you can do this in your head or on paper, saying things aloud can help ground them in reality.

While you can do this in your head or on paper, saying things aloud can help ground them in reality.

It can also make them less upsetting. Simply giving voice to unwanted thoughts brings them out into the light of day, where they often seem more manageable. Voicing emotions also helps you validate and come to terms with them. This can, in turn, diminish their impact.

By now, you probably feel a little better about talking to yourself. And self-talk certainly can be a powerful tool for boosting mental health and cognitive function.

Like all tools, though, you’ll want to use it correctly. These tips can help you maximize the benefits of self-directed speech.

Positive words only

Though self-criticism may seem like a good option for holding yourself accountable and staying on track, it usually doesn’t work as intended.

Blaming yourself for unwanted outcomes or speaking to yourself harshly can affect your motivation and self-confidence, which won’t do you any favors.

There’s good news, though: Reframing negative self-talk can help. Even if you haven’t yet succeeded at your goal, acknowledge the work you’ve already done and praise your efforts.

Instead of saying: “You’re not trying hard enough. You’ll never get this done.”

Try: “You’ve put a lot of effort into this. It’s taking a long time, true, but you can definitely get it done. Just keep going a little longer.”

Question yourself

When you want to learn more about something, what do you do?

You ask questions, right?

Asking yourself a question you can’t answer won’t magically help you find the correct response, of course. It can help you take a second look at whatever you’re trying to do or want to understand. This can help you figure out your next step.

In some cases, you might actually know the answer, even if you don’t realize it. When you ask yourself “What might help here?” or “What does this mean?” try answering your own question (this can have particular benefit if you’re trying to grasp new material).

If you can give yourself a satisfactory explanation, you probably do understand what’s going on.

Pay attention

Talking to yourself, especially when stressed or trying to figure something out, can help you examine your feelings and knowledge of the situation. But this won’t do much good if you don’t actually listen to what you have to say.

You know yourself better than anyone else does, so try to tune in to this awareness when you feel stuck, upset, or uncertain. This can help you recognize any patterns contributing to distress.

Don’t be afraid to talk through difficult or unwanted feelings. They might seem scary, but remember, you’re always safe with yourself.

Avoid first person

Affirmations can be a great way to motivate yourself and boost positivity, but don’t forget to stick with second person.

Mantras like “I am strong,” “I am loved,” and “I can face my fears today” can all help you feel more confident.

When you phrase them as if you’re speaking to someone else, you might have an easier time believing them. This can really make a difference if you struggle with self-compassion and want to improve self-esteem.

So try instead: “You are strong,” “You are loved,” or “You can face your fears today.”

Again, there’s nothing at all wrong with talking to yourself. If you do it regularly at work or other places where it could disrupt others, you might wonder how you can break this habit or at least scale it back a bit.

Keep a journal

Talking to yourself can help you work through problems, but so can journaling.

Writing down thoughts, emotions, or anything you want to explore can help you brainstorm potential solutions and keep track of what you’ve already tried.

What’s more, writing things down allows you to look over them again later.

Keep your journal with you and pull it out when you have thoughts you need to explore.

Ask other people questions instead

Maybe you tend to talk yourself through challenges when you get stuck at school or work. The people around you can also help.

The people around you can also help.

Instead of trying to puzzle something out yourself, consider chatting to a co-worker or classmate instead. Two heads are better than one, or so the saying goes. You might even make a new friend.

Distract your mouth

If you really need to keep quiet (say you’re in the library or a quiet workspace), you might try chewing gum or sucking on hard candy. Having to talk around something in your mouth can remind you not to say anything out loud, so you might have more success keeping your self-talk in your thoughts.

Another good option is to carry a drink with you and take a sip whenever you open your mouth to say something to yourself.

Remember that it’s very common

If you slip up, try not to feel embarrassed. Even if you don’t notice it, most people do talk to themselves, at least occasionally.

Brushing off your self-talk with a casual, “Oh, just trying to stay on task,” or “Searching for my notes!” can help normalize it.

Some people wonder if frequently talking to themselves suggests they have an underlying mental health condition, but this usually isn’t the case.

While people with conditions that affect psychosis such as schizophrenia may appear to talk to themselves, this generally happens as a result of auditory hallucinations. In other words, they often aren’t talking to themselves, but replying to a voice only they can hear.

If you hear voices or experience other hallucinations, it’s best to seek professional support right away. A trained therapist can offer compassionate guidance and help you explore potential causes of these symptoms.

A therapist can also offer support if you:

- want to stop talking to yourself but can’t break the habit on your own

- feel distressed or uncomfortable about talking to yourself

- experience bullying or another stigma because you talk to yourself

- notice you mostly talk down to yourself

Have a habit of running through your evening plans aloud while walking your dog? Feel free to keep at it! There’s nothing strange or unusual about talking to yourself.

If self-talk inconveniences you or causes other problems, a therapist can help you explore strategies to get more comfortable with it or even break the habit, if you choose.

Crystal Raypole has previously worked as a writer and editor for GoodTherapy. Her fields of interest include Asian languages and literature, Japanese translation, cooking, natural sciences, sex positivity, and mental health. In particular, she’s committed to helping decrease stigma around mental health issues.

why dialogue with oneself is dangerous - T&P

In psychology, internal dialogue is one of the forms of thinking, the process of a person communicating with himself. It becomes the result of the interaction of different ego states: "child", "adult" and "parent". The inner voice often criticizes us, gives advice, appeals to common sense. But is he right? T&P asked several people from different fields what their inner voices sound like and asked a psychologist to comment on this.

Internal dialogue has nothing to do with schizophrenia. Everyone has voices in their heads: it is we ourselves (our personality, character, experience) who speak to ourselves, because our Self consists of several parts, and the psyche is very complex. Thinking and reflection are impossible without an internal dialogue. Not always, however, it is framed as a conversation, and not always some of the remarks seem to be uttered by the voices of other people - as a rule, relatives. The “voice in the head” can also sound like one’s own, or it can “belong” to a completely stranger: a classic of literature, a favorite singer. nine0005

From the point of view of psychology, internal dialogue is a problem only if it develops so actively that it begins to interfere with a person in everyday life: it distracts him, confuses him. But more often this silent conversation "with oneself" becomes material for analysis, a field for finding sore spots and a testing ground for developing a rare and valuable ability to understand and support oneself.![]()

Roman

sociologist, marketer

It is difficult for me to distinguish any characteristics of the inner voice: shades, timbre, intonations. I understand that this is my voice, but I hear it in a completely different way, not like the others: it is more booming, low, rough. Usually in the internal dialogue, I imagine the acting role model of some situation, hidden direct speech. For example, what would I say to this or that public (despite the fact that the public can be very different: from casual passers-by to clients of my company). I need to convince them, to convey my idea to them. Usually I also play intonations, emotions and expression. nine0005

At the same time, there is no discussion as such: there is an internal monologue with reflections like: “What if?”. Does it happen that I myself call myself an idiot? It happens. But this is not a condemnation, but rather something between annoyance and a statement of fact.

If I need an outside opinion, I change the prism: for example, I try to imagine what one of the classics of sociology would say. In terms of sound, the voices of the classics are no different from mine: I remember exactly logic and "optics". I can clearly distinguish alien voices only in a dream, and they are accurately modeled by real counterparts. nine0005

In terms of sound, the voices of the classics are no different from mine: I remember exactly logic and "optics". I can clearly distinguish alien voices only in a dream, and they are accurately modeled by real counterparts. nine0005

Anastasia

prepress specialist

In my case, the inner voice sounds like my own. Basically, he says: "Nastya, stop it", "Nastya, don't be stupid" and "Nastya, you're a fool!". This voice appears infrequently: when I feel uncollected, when my own actions make me dissatisfied. The voice is not angry - rather irritated.

I have never heard in my thoughts either my mother's, or my grandmother's, or anyone else's voice: only my own. He can scold me, but within certain limits: without humiliation. This voice is more like my coach: it presses the buttons that encourage me to take action. nine0005

Ivan

screenwriter

What I hear in my mind is not formed as a voice, but I recognize this person by the structure of my thoughts: she looks like my mother. And even more precisely: it is an "internal editor" that explains how to make the mother like it. For me, as a hereditary filmmaker, this is an unflattering name, because in the Soviet years for a creative person (director, writer, playwright) an editor is a stupid protege of the regime, a not very educated censor who revels in his own power. It is unpleasant to realize that this type in you censors thoughts and clips the wings of creativity in all areas. nine0005

And even more precisely: it is an "internal editor" that explains how to make the mother like it. For me, as a hereditary filmmaker, this is an unflattering name, because in the Soviet years for a creative person (director, writer, playwright) an editor is a stupid protege of the regime, a not very educated censor who revels in his own power. It is unpleasant to realize that this type in you censors thoughts and clips the wings of creativity in all areas. nine0005

The "internal editor" gives many of his comments on the case. However, the question lies in the purpose of this "case". To summarize, he says: "Be like everyone else and don't stick your head out." He feeds the inner coward. “You need to be an excellent student,” because it eliminates problems. Everyone likes it. He makes it difficult to understand what I myself want, whispers that comfort is good, and the rest later. This editor doesn't really let me be an adult in the good sense of the word. Not in the sense of dullness and lack of play space, but in the sense of the maturity of the individual. nine0005

nine0005

I hear my inner voice mostly in situations that remind me of my childhood, or when a direct display of creativity and fantasy is needed. Sometimes I succumb to the "editor" and sometimes I don't. The most important thing is to recognize his intervention in time. Because he disguises himself well, hiding behind pseudological conclusions that do not really make sense. If I recognized him, then I try to understand what the problem is, what I myself want and where the truth really is. When this voice, for example, interferes with my creativity, I try to stop and go into the space of "complete emptiness", starting all over again. The difficulty lies in the fact that the "editor" can be difficult to distinguish from simple common sense. To do this, you need to listen to your intuition, move away from the meaning of words and concepts. Often this helps. nine0005

Irina

translator

My internal dialogue is designed as the voices of my grandmother and Masha's friend. These are people whom I considered close and important: I lived with my grandmother in my childhood, and Masha was there at a difficult time for me. Grandma's voice says that I have crooked hands and that I'm clumsy. And Masha's voice repeats different things: that I again got in touch with the wrong people, I lead the wrong lifestyle and do the wrong things. They both always judge me. At the same time, voices appear at different moments: when something doesn’t work out for me, my grandmother “says”, and when everything works out for me and I feel good, Masha. nine0005

I react aggressively to these voices: I try to silence them, I argue with them mentally. I tell them back that I know better what and how to do with my life. Most often, I manage to argue with my inner voice. But if not, I feel guilty and feel bad.

Kira

prose editor

In my mind I sometimes hear my mother's voice, which condemns me and devalues my achievements, doubts me. This voice is always dissatisfied with me and says: “What are you talking about! Are you out of your mind? Do better profitable business: you have to earn. Or: "You must live like everyone else." Or: "You will not succeed: you are nobody." It appears if I have to take a bold step or take a risk. In such situations, the inner voice, as it were, tries to manipulate me (“mom is upset”) to persuade me to the safest and most unremarkable course of action. To make him happy, I must be inconspicuous, diligent, and everyone likes me. nine0005

I also hear my own voice: he calls me not by my name, but by a nickname that my friends have come up with. He usually sounds a bit annoyed but friendly and says, “So. Stop”, “Well, what are you, baby” or “Everything, come on.” It encourages me to focus or take action.

Ilya Shabshin

counseling psychologist, leading specialist of the Psychological Center on Volkhonka

This whole selection speaks of what psychologists are well aware of: most of us have a very strong inner critic. We communicate with ourselves mainly in the language of negativity and rude words, using the whip method, and we have practically no self-support skills. nine0005

In Roman's commentary, I liked the technique, which I would even call psychotechnics: "If I need an outside opinion, I try to imagine what one of the classics of sociology would say." This technique can be used by people of different professions. In Eastern practices, there is even the concept of an "inner teacher" - a deep wise inner knowledge that you can turn to when it's hard for you. A professional usually has one or another school or authoritative figures behind him. Imagine one of them and ask what he would say or do is a productive approach. nine0005

An illustrative illustration of the general theme is Anastasia's commentary. A voice that sounds like your own and says: “Nastya, you are a fool! Don't be dumb. Stop it,” is, of course, according to Eric Berne, the Critical Parent. It is especially bad that the voice appears when she feels "uncollected", if her own actions cause dissatisfaction - that is, when, in theory, the person just needs to be supported. And instead, the voice tramples into the ground. .. And although Anastasia writes that he acts without humiliation, this is a small consolation. Maybe, as a “coach”, he presses the wrong buttons, and it’s not worth kicking, not reproaching, not insulting him to encourage himself to action? But, I repeat, such interaction with oneself is, unfortunately, typical. nine0005

.. And although Anastasia writes that he acts without humiliation, this is a small consolation. Maybe, as a “coach”, he presses the wrong buttons, and it’s not worth kicking, not reproaching, not insulting him to encourage himself to action? But, I repeat, such interaction with oneself is, unfortunately, typical. nine0005

You can induce yourself to action by first removing your fears by saying to yourself: “Nastya, everything is fine. It's okay, we'll figure it out." Or: "Here, look: it turned out well." "Yes, well done, you can do it!". “Do you remember how you did everything great then?” This method is suitable for any person who tends to criticize himself.

The last paragraph in Ivan's text is important: it describes the psychological algorithm for dealing with the inner critic. Point one: "Recognize interference." This problem often arises: something negative is disguised under the guise of useful statements, penetrates a person’s soul and establishes its own rules there. Then the analyst turns on, trying to understand what the problem is. According to Eric Berne, this is the adult part of the psyche, the rational one. Ivan even has author's tricks: "go out into the space of complete emptiness", "listen to intuition", "depart from the meaning of words and understand everything". Great, that's how it's supposed to be! Based on general rules and a common understanding of what is happening, it is necessary to find your own approach to what is happening. As a psychologist, I applaud Ivan: he has learned to talk to himself well. Well, what he fights is a classic: the internal editor is still the same critic. nine0005

Then the analyst turns on, trying to understand what the problem is. According to Eric Berne, this is the adult part of the psyche, the rational one. Ivan even has author's tricks: "go out into the space of complete emptiness", "listen to intuition", "depart from the meaning of words and understand everything". Great, that's how it's supposed to be! Based on general rules and a common understanding of what is happening, it is necessary to find your own approach to what is happening. As a psychologist, I applaud Ivan: he has learned to talk to himself well. Well, what he fights is a classic: the internal editor is still the same critic. nine0005

“At school we are taught to extract square roots and carry out chemical reactions, but they don’t teach us to communicate normally with ourselves anywhere”

Ivan has another interesting observation: “You need to keep a low profile and be an excellent student.” Kira notes the same. Her inner voice also says that she should be invisible and everyone should like her. But this voice introduces its own, alternative logic, because you can either be the best or keep a low profile. However, such statements are not taken from reality: these are all internal programs, psychological attitudes from various sources. nine0005

But this voice introduces its own, alternative logic, because you can either be the best or keep a low profile. However, such statements are not taken from reality: these are all internal programs, psychological attitudes from various sources. nine0005

The “keep your head down” attitude (like most others) comes from upbringing: in childhood and adolescence, a person draws conclusions about how to live, gives himself instructions based on what he hears from parents, educators, and teachers.

In this regard, the example of Irina looks sad. Close and important people - a grandmother and a friend - tell her: "You have crooked hands, and you are clumsy", "you live wrong." A vicious circle arises: her grandmother condemns her when something does not work out, and her friend when everything is fine. Total criticism! Neither when it is good, nor when it is bad, there is no support and consolation. Always a minus, always a negative: either you are clumsy, or something else is wrong with you. nine0005

nine0005

But Irina is doing well, she behaves like a fighter: she silences voices or argues with them. This is how it should be done: the power of the critic, whoever he may be, must be weakened. Irina says that most often she gets votes over an argument - this phrase suggests that the opponent is strong. And in this regard, I would suggest that she try other ways: firstly (since she hears it as a voice), imagine that it comes from the radio, and she turns the volume knob towards the minimum, so that the voice fades, it gets worse heard. Then, probably, his power will weaken, and it will become easier to outguess him - or even just brush him off. After all, such an internal struggle creates quite a lot of tension. Moreover, Irina writes at the end that she feels guilty if she fails to argue. nine0005

Negative ideas penetrate deeply into our psyche in the early stages of its development, especially easily in childhood, when they come from big authoritative figures with whom, in fact, it is impossible to argue. The child is small, and around him are huge, important, strong masters of this world - adults on whom his life depends. You can't really argue here.

The child is small, and around him are huge, important, strong masters of this world - adults on whom his life depends. You can't really argue here.

In adolescence, we also solve difficult problems: we want to show ourselves and others that you are already an adult, and not a little one, although in fact, in the depths of your soul, you understand that this is not entirely true. Many teenagers become vulnerable, although outwardly they look prickly. At this time, statements about yourself, about your appearance, about who you are and what you are, sink into the soul and later become dissatisfied with inner voices that scold and criticize. We talk to ourselves so badly, so nastily, as we would never talk to other people. You would never say anything like that to a friend - and in your head your voices towards you easily allow yourself to do this. nine0005

To correct them, first of all, you need to realize: “The things that sound in my head are not always good thoughts. There may be opinions and judgments that were simply learned once. They don’t help me, it’s not useful for me, and their advice doesn’t lead to anything good.” You need to learn to recognize them and deal with them: to refute, muffle or otherwise remove the inner critic from yourself, replacing it with an inner friend who provides support, especially when it’s bad or difficult. nine0005

They don’t help me, it’s not useful for me, and their advice doesn’t lead to anything good.” You need to learn to recognize them and deal with them: to refute, muffle or otherwise remove the inner critic from yourself, replacing it with an inner friend who provides support, especially when it’s bad or difficult. nine0005

At school, we are taught to extract square roots and carry out chemical reactions, but nowhere is it taught to communicate normally with oneself. And you need to cultivate healthy self-support instead of self-criticism. Of course, you do not need to draw a halo of holiness around your own head. When it is difficult, you need to be able to cheer yourself up, support, praise, remind yourself of successes, achievements and strengths. Do not humiliate yourself as a person. Say to yourself: “In a specific area, at a specific moment, I can make a mistake. But this has nothing to do with my human dignity. My dignity, my positive attitude towards myself as a person is an unshakable foundation. And mistakes are normal and even good: I will learn from them, I will develop and move on.” nine0005

And mistakes are normal and even good: I will learn from them, I will develop and move on.” nine0005

Icons: Justin Alexander from the Noun Project

Why do we talk to ourselves? — Knife

What is your voice in your head? Is this your own voice? Velvety male bass? Or, on the contrary, a female voice - and sweet-voiced Scarlett Johansson distributes comments in her head? Maybe your inner speech changes every now and then, jumping from bass to airy mezzo-soprano.

Put your hand to your throat: while you are talking to yourself, the muscles of the larynx are barely noticeable there. And now move your hand to the area near the left ear, a little higher and closer to the temple - somewhere there rustle neurons in the left lower frontal gyrus and superior temporal gyrus, Broca's and Wernicke's zones. These areas of the brain are responsible for the production and perception of speech: they allow us to have a normal conversation, they also create an internal one. nine0005

nine0005

The chorus of voices in the head is fragile, it can easily get out of rhythm and start to get out of tune. If the speech areas of the brain are damaged due to a stroke or injury, aphasia occurs, a violation of oral speech, while the inner voice also loses harmony. Patients with aphasia, for example, cannot tell if a pair of words rhyme when they are spoken to themselves.

It also happens that inner speech is perceived as generated by someone else.

Normally, during dialogue-in-itself, a signal should come to the area of speech perception, which will mute the activity of her neurons, which means that they will not react to internal speech as much as to a live conversation.

For some reason this muting does not work in psychiatric disorders.

“I hear distinct voices. Each voice has its own personality. They often try to tell me what to do, they try to impose their own thoughts or feelings, ”a patient with auditory hallucinations described his experience.

“If the voice attacks and insults the patient, he will be depressed and suicidal. If the voice tells the patient to kill, then, if self-control is lost, the patient is likely to attack other people. If a voice tells a person that he is beautiful and powerful, manic forms of behavior appear, ”the English psychologist Lorna Smith Benjamin wrote about voice hallucinations. nine0005

Sometimes voices, on the contrary, turn out to be positive experiences that have nothing to do with pathology. They can calm, inspire confidence, suggest solutions.

Another variant of the norm is the absence of inner speech. In a small study in 2011, volunteers were given sound-producing devices and asked to record their thoughts and feelings each time they heard a peep, a technique called the description intercept method. The study found significant differences between the volunteers: some chatted 75% of the time, others played silent in their head and never talked to themselves. nine0005

nine0005

“Today I told my mom that I don’t have an internal monologue, and she stared at me like I had three heads,” a Reddit user shared. “I sincerely believed that this was a fictional concept, a trick that the creators of the Dexter series about the psychopath came up with. How do you do it? How do you talk in your head? I can not imagine".

It turned out that the absence of inner speech is not a rare phenomenon. Instead of a dialogue, images, feelings, symbols swarm in the head of such people. And every time they have to get out of their own heads and communicate with words, they are forced to "translate" their thoughts. nine0005

nine0004 But how did the voices - good and bad, chatty and silent - get inside the skull?“When I have to communicate verbally (for example, I need to make a phone call), I prepare myself so that I know what words I really need to say,” another user joined the discussion of the entry. - If I participate in a conversation where I don’t have time to prepare, organize and “translate” my thoughts in advance, long pauses constantly appear in speech.

This may seem strange. This annoyed my wife until we both figured out why this was happening."

See also

Voices in the head: how auditory hallucinations change the concept of normality and pathology

Moving from childhood

Children around the age of three during the game all the time talking aloud: giving instructions not only to toys, but also to themselves. Their tendency to chat with themselves, to self-centered speech helps to trace the origins of the voice in the head. nine0005

Psychologists of the last century suggested that internal dialogue is nothing but external speech that has moved inside.

One of the first hypotheses was proposed by the psychologist and founder of behaviorism John Brodes Watson. His idea was rather mechanical: there is a simple fading of verbal behavior—from loud thinking aloud in a child, through mumbling and whispering, to silent dialogue in the head of an adult. A somewhat similar idea was expressed by the Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky. He also believed that internal speech is the result of internalization, that is, absorption, of external speech. According to Vygotsky, children become independent, move away from their parents, and therefore, in the absence of instructions from adults, begin to direct their actions aloud. This self-guidance in the child will then become an internal dialogue. nine0005

A somewhat similar idea was expressed by the Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky. He also believed that internal speech is the result of internalization, that is, absorption, of external speech. According to Vygotsky, children become independent, move away from their parents, and therefore, in the absence of instructions from adults, begin to direct their actions aloud. This self-guidance in the child will then become an internal dialogue. nine0005

However, we do not “grow out” of egocentric speech; adults also like to chat with themselves out loud. For some, such reasoning is an aid to difficult tasks. Others use it to plan actions, organize chaos in their heads. And still others seek solace in egocentric speech.

“When I'm anxious, I can calm myself out loud,” says Yulia, a respondent to my online survey. - I call it the "voice of reason", which tells me: "This is nonsense", "You can handle it." After fakapov exactly out loud saying it's okay to make mistakes, it helps to chew yourself less.

The phenomenon of self-consolation and self-support through egocentric speech can be considered evidence of Vygotsky's hypothesis. After all, in childhood we heard words of support from adults, and now we are often forced to pronounce them ourselves. Probably, it is precisely because of this replacement of external support with internal that the words spoken as if from the side - "YOU will succeed" - in experiments work better than those said in the first person: "I will succeed." nine0005

Dialogues from the shadows

From Vygotsky's idea, we can conclude that the structure of inner speech should resemble outer speech - it should be a dialogue. For a normal dialogue, some idea of the interlocutor's position is important, which will be refined as the conversation progresses: through questions and answers, arguments and counterarguments, expression of agreement and disagreement.

If the structure of inner speech is somewhat similar to an ordinary dialogue, it means that not only areas of language zones, but also those involved in recognizing the interlocutor's position, should be activated in the brain. The scientists were able to confirm this assumption. Once they asked volunteers, carefully placed in an MRI scanner, to first conduct an internal monologue (imagine that they are speaking to schoolchildren), and then a dialogue (imagine that they are talking to the principal). On fMRI, it was noticeable that in the conditions of dialogue, but not monologue, not only speech zones were active, but also social cognition centers located in the right hemisphere. These areas of the brain form ideas about the lifestyle, desires and beliefs of other people, and probably do the same for a fictional interlocutor. nine0005

The scientists were able to confirm this assumption. Once they asked volunteers, carefully placed in an MRI scanner, to first conduct an internal monologue (imagine that they are speaking to schoolchildren), and then a dialogue (imagine that they are talking to the principal). On fMRI, it was noticeable that in the conditions of dialogue, but not monologue, not only speech zones were active, but also social cognition centers located in the right hemisphere. These areas of the brain form ideas about the lifestyle, desires and beliefs of other people, and probably do the same for a fictional interlocutor. nine0005

However, although inner speech retains the structure of the dialogue, it also undergoes changes. For example, it becomes shorter - condenses and abbreviates.

Agree, it is unlikely that you, smelling the smell of burning from the kitchen, will bother to formulate full sentences: “I must have forgotten that I put the rice to boil.” No, in your head you shout "Rice!" or even some swear word. And this applies not only to emergency situations: any sentences addressed to oneself, as a rule, are much shorter than those addressed to a real interlocutor. The tendency to contraction was noted by people in one of the surveys about the features of inner speech. nine0005

And this applies not only to emergency situations: any sentences addressed to oneself, as a rule, are much shorter than those addressed to a real interlocutor. The tendency to contraction was noted by people in one of the surveys about the features of inner speech. nine0005

Condensation of inner speech is connected with the fact that we understand ourselves literally “at a glance”, while in a normal dialogue the interlocutor does not have such an exhaustive idea of our thoughts or accompanying circumstances. The reduction in speech is also due to the fact that we adjust our inner speech to suit ourselves: we can create word hybrids, imbue words with additional meanings (“an interview” said in the head means not only an “interview”, but also a complex of experiences from excitement to hope, but also intentions and plans to prepare). nine0005

In general, the voice in the head is short, because it compresses the words to pure meaning. “We think not in words, but in shadows of words,” wrote Vladimir Nabokov, and he seemed to be damn right. The fact that thoughts sounded by a voice in the head turn out to be completely different than the same thoughts spoken aloud leads to amusing consequences. Everything may sound better in your head than in reality.

The fact that thoughts sounded by a voice in the head turn out to be completely different than the same thoughts spoken aloud leads to amusing consequences. Everything may sound better in your head than in reality.

“I think I'm smarter on the inside. And as soon as I open my mouth - so forgive me, Lord ... ”- Anya mockingly complains in the survey.

Control it

Why do we need a voice in our heads? How will life change if we can't talk about ourselves? What will become more difficult, and what is completely impossible? Researchers identify several roles of the inner voice. For example, participation in executive functions, that is, the processes of planning, self-control, problem solving. “If there is a difficult conversation ahead, I can think in advance how to express my thought”; “For me, this is a way of control: I go to work and discuss what to do and in what sequence. If something didn’t work out at work, I go home and discuss all the stages with myself. It seems to me that this improves concentration and accuracy of execution,” the respondents noted. nine0005

It seems to me that this improves concentration and accuracy of execution,” the respondents noted. nine0005

Talking to yourself, both out loud and to yourself, can really be helpful. In the experiment with athletes participants who talked to themselves performed better on the control task and reported increased self-confidence and reduced anxiety .

On the contrary, delayed development of egocentric and inner speech, for example, in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, may partly cause a violation of self-regulation. At the same time, cognitive-behavioral therapy using “self-talk” is effective in correcting self-control in ADHD. nine0005

But sometimes the executive function of speech-in-itself can take on painful proportions.

“I used to say all the dialogues before meetings,” Anya says. - And when the dialogue happened live, everything did not go according to the script written in my head - I was covered with anxiety.

“Everything didn’t go according to plan, Carl!” I didn’t know what to answer, what to ask. The psychologist specially retrained me, so now I don’t rehearse the dialogues in my head.”

Memory words

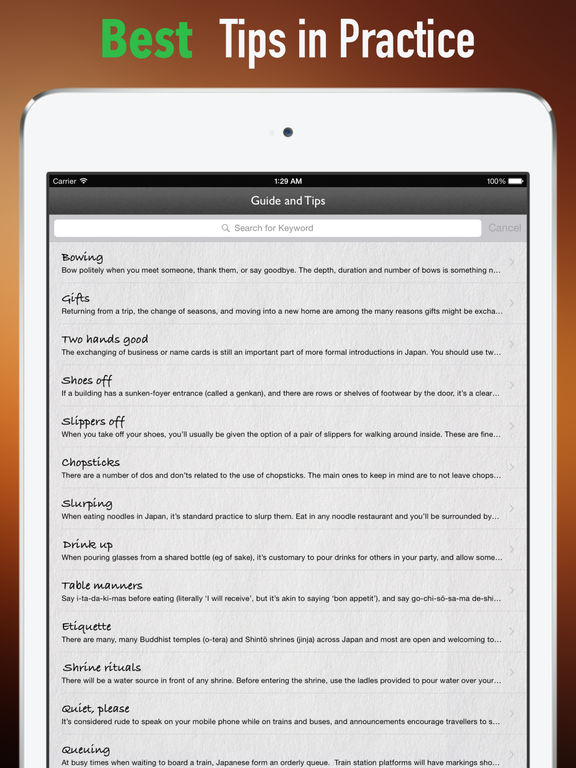

The inner voice is also needed for working memory, i.e. keeping information in your head while you are busy doing something, say to "save" your shopping list while you go shopping.

In 1974, British psychologists Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch proposed a multicomponent model of working memory. Its essence is that memory consists of a central executive body that manages attention resources and its three "servants": an episodic buffer - a temporary storage of stimuli, a visual-spatial "notebook" and a phonological circuit responsible for the presentation of sound and speech information. Due to the fact that the inner voice seems to "voice" part of the working memory, the phonology of words affects their memorization: long words are more difficult to remember; we also have a harder time remembering words that sound similar than words that sound different. nine0005

nine0005

The participation of the “voice” in memory processes is also indicated by the fact that in patients with damage to the speech areas of the brain, along with aphasia and impaired internal dialogue, working memory also limps.

Maybe interesting

Anatomy of decision making: what is working memory and can it be improved

It is curious, however, that speaking memories out loud can also play a cruel joke. When "speech" memory creeps into visual, that is, when we talk about what we saw, verbal eclipse . The term was coined by cognitive psychologists Jonathan Skuler and Tonia Engst-Skuler when they showed that verbal description of a criminal was associated with a 25% reduction in face recognition (currently, verbal eclipse steals 4-16%). The verbal part of our memory can distort the visual image, so even in private, pronounce memories with caution.

How do you like it, Elon Musk?

Charles Fernyhow, Professor of Psychology at Durham University, in his book Voices Within suggests that inner speech is also a dope for creativity. He cites the example of the physicist Richard Feynman, who could stop in the middle of the street and, actively gesturing, start talking to himself ... or someone in his head. This is because, in trying to solve a scientific problem, Feynman was conducting an internal interrogation:

He cites the example of the physicist Richard Feynman, who could stop in the middle of the street and, actively gesturing, start talking to himself ... or someone in his head. This is because, in trying to solve a scientific problem, Feynman was conducting an internal interrogation:

“The integral will be greater than the sum of the terms, so as you can see, the pressure will be higher. - No, you're crazy! - And here it is not!

In our heads, we can start a casual conversation with any interlocutor: living or dead, real or fictional. People in their heads play unrealizable dialogues: they come up with what they would answer if they were interviewed by Yuri Dud or Irina Shikhman; as if they dodged, answering questions from the time of Marcel Proust in the program of Vladimir Pozner; what "Dissenting Opinion" could be expressed on "Echo of Moscow". nine0005

“Sometimes I lose a dialogue that won’t take place in principle,” says Ilya.

— I can talk with an alien in my head, for example. Or I discuss space exploration with Elon Musk, what he thinks about the oil powers that can squeeze him for electric cars.

Conversations with imaginary interlocutors can be unpredictable and exciting, and it is possible that they contribute to the birth of new ideas.

See also

"There are no pictures in my head, only text." nine0136 How do non-fiction people live - people unable to represent visual images

Hey Siri?

Recently, another type of conversation has appeared without a real interlocutor. Sociologist Polina Aronson, in her book Do-it-yourself Love, notes that more and more people are seeking solace from their gadgets:

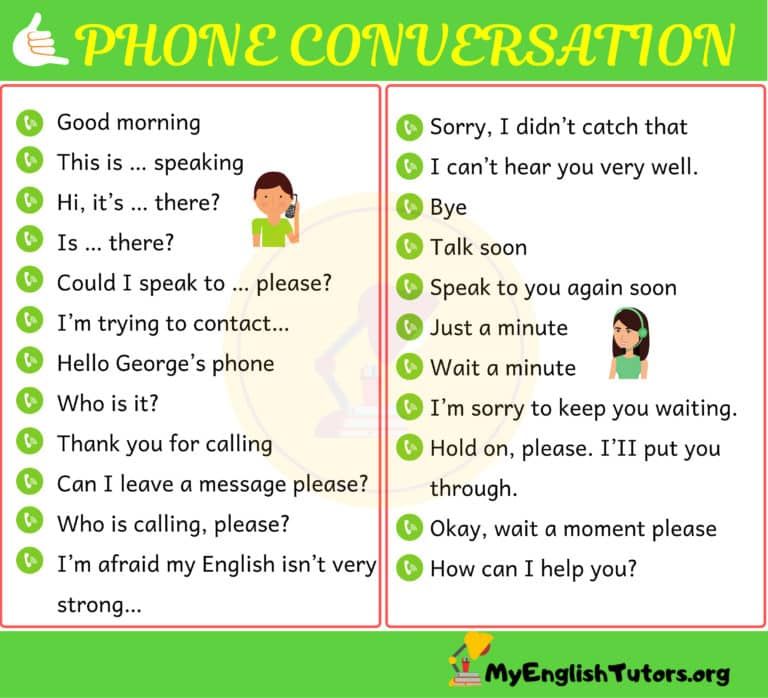

jokes, questions about the meaning of life. “People talk to Siri in a variety of situations: sometimes they complain about a hard day, sometimes they want to discuss exciting issues. Sometimes they turn to her in emergency situations, sometimes they ask for advice about a healthy lifestyle, "says Apple's announcement of a vacancy for the position of an IT specialist who is able to" teach "a voice assistant to talk to people about their emotions.

" nine0005

According to one study , people are less afraid of frankness when talking to artificial intelligence. And that is why consolation from a real person is constantly replaced by a search for sympathy at a digital screen.

While we are banging on the microphone to Alice or Siri, IT giants are teaching empathy to artificial intelligence. After chewing through a huge amount of data, the machine learns to empathize with the help of the most repeated reactions. And therefore, voice assistants become a grotesque reflection of the emotional regime of society, that is, "the rules and norms that determine how to experience our feelings and how to express them." A Californian hipster Google Assistant responds to a user’s complaint “I’m sad” by complaining about the lack of arms for hugs. Siri will prompt you to talk to a close friend or family member. And Alice, tailored for a Russian-speaking user who is used to irony and black humor, will cut off: "No one promised that it would be easy.