Howard gardner and emotional intelligence

The Importance of Emotional Intelligence in the Workplace

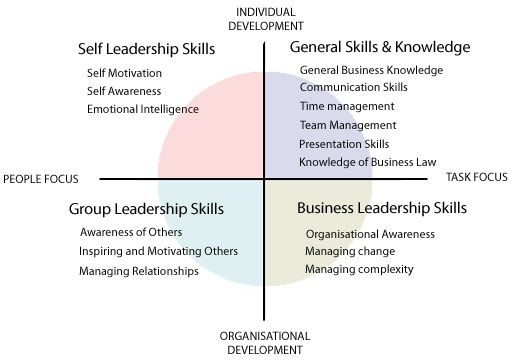

Some employers measure applicants’ intelligence with tests designed to assess their ability to grasp and synthesize facts, which may provide insight into their potential for success. While conventional measures of intelligence focused on logic and reasoning have been the standard, there’s an increased interest in expanding this to include measures of emotional intelligence. While a relatively new term, emotional intelligence is increasingly recognized as a critical component of an individual’s skill set.

In fact, the World Economic Forum’s “Future of Jobs Survey 2020” projected that emotional intelligence will be one of the top skills needed in business in 2025. Employers are considering the importance of emotional intelligence in the workplace because it can be a crucial indicator of a prospective employee’s capabilities, including how well they would function as part of the company’s culture. An advanced degree such as a master’s in applied psychology can help those in human resources and people analytics positions understand and identify emotional intelligence, which can aid in hiring and other leadership decisions.

What Is Emotional Intelligence?

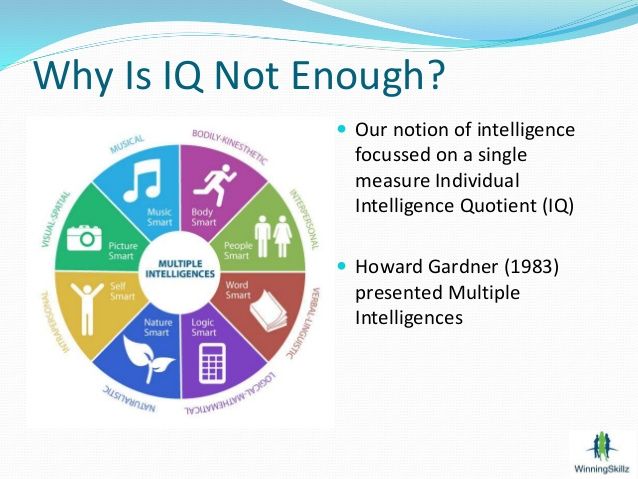

Emotional intelligence describes a person’s capacity to recognize and contextualize their emotions and the emotions of others. The concept stems from Dr. Howard Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Developed in the 1980s. The theory suggests that people possess intellectual capacity in different forms that correlate to specific attributes such as music or athletics. The work of people such as psychologist Dr. Daniel Goleman has helped to shape our understanding of emotional intelligence by focusing on two of Gardner’s theoretical intellectual forms:

- Interpersonal Intelligence — Detecting and responding to others’ moods, motivations and desires

- Intrapersonal Intelligence — Being self-aware and attuned with one’s own values, beliefs and thinking

Emotional intelligence differs from rational intelligence in its focus. Rational intelligence involves facts and tight logical reasoning. On the other hand, emotional intelligence concerns how facts and reasoning are applied. This leads some to theorize that high emotional intelligence (quantified by EQ) is more important in business than high rational intelligence (quantified by IQ).

On the other hand, emotional intelligence concerns how facts and reasoning are applied. This leads some to theorize that high emotional intelligence (quantified by EQ) is more important in business than high rational intelligence (quantified by IQ).

Ideally, the two work in concert — without the guiding influence of rational intelligence, emotional intelligence has the potential to become deeply subjective in a way that isn’t conducive to business goals. Used effectively, however, it can be key to fostering internal collaboration and external alliances in professional contexts.

Why Is Emotional Intelligence Important in the Workplace?

In its most refined form, emotional intelligence provides the empathy necessary to fully understand another’s perspective even when it contradicts one’s own. Emotional intelligence has much to offer the modern workplace and stakeholders across all functions:

- It helps leaders motivate and inspire good work by understanding others’ motivations.

- It brings more individuals to the table and helps avoid the many pitfalls of groupthink.

- It empowers leaders to recognize and act on opportunities others may be unaware of.

- It assists in the recognition and resolution of conflict in a fair and even-handed way.

- It can produce higher morale and assist others in tapping their professional potential.

Like rational intelligence, emotional intelligence can be cultivated through dedicated effort and study. The first step to developing greater emotional intelligence is often to strengthen one’s powers of introspection. Recognizing thought processes, emotions and biases can lead to more well-rounded decisions. Exercising emotional intelligence often requires one to act with confidence, rise above worries about status and question or bypass knee-jerk reactions.

Here are some reasons why emotional intelligence is important in the workplace:

It Helps in the Hiring Process

Although technical skills can be imparted through training, it is far more difficult to inculcate emotional intelligence in new hires. Enterprises can integrate theories of emotional intelligence into their hiring and professional development processes at all levels. For example, entry-level hires may be tested for their “EQ” when in competition for a new role or a promotion. Stakeholders who are identified as having high leadership potential might deliver better results if emotional intelligence is made part of their development process.

Enterprises can integrate theories of emotional intelligence into their hiring and professional development processes at all levels. For example, entry-level hires may be tested for their “EQ” when in competition for a new role or a promotion. Stakeholders who are identified as having high leadership potential might deliver better results if emotional intelligence is made part of their development process.

Although all roles might benefit from emotional intelligence, not all roles require highly developed emotional intelligence. However, the higher one climbs in the typical organization, the more valuable it may be — even as its absence may make high-stakes failures more likely. Professionals in some areas, such as human resources or public relations, benefit from emotional intelligence throughout their careers. Proactively vetting these hires for their state of emotional development may help companies maximize their contribution and optimize future development investments.

It Eases Navigation of the Globalized Economy

As the global economy has developed into a system characterized by collaboration, negotiation and communication — with all the conceptual ambiguities those denote — emotional intelligence has grown to play a bigger role in the public sphere. Emotional intelligence is correlated with traits like perseverance, self-control and performance under pressure. It provides leaders, no matter their skills, with the emotional fortitude to adapt to change and deal with setbacks.

Emotional intelligence is correlated with traits like perseverance, self-control and performance under pressure. It provides leaders, no matter their skills, with the emotional fortitude to adapt to change and deal with setbacks.

No matter how the economy transforms, “conventional” intelligence will always be immensely important. However, even the most highly technical roles now include increasing contact with diverse stakeholders, advocating for positions in complex environments and investing mental and emotional capital to deal with uncertain situations. Both rational intelligence and emotional intelligence are here to stay, and well-rounded leaders exhibit and develop both of them.

Key Takeaways for Management

With the emerging emphasis on emotional intelligence in the workplace, managers should remember these points:

- Rational intelligence focuses on rational, “objective” analysis of facts and figures.

- Emotional intelligence consists of insight into others’ emotions as well as one’s own.

- High emotional intelligence drives collaborative leadership and win-win outcomes.

- Emotional intelligence is correlated with confidence, resilience and perseverance.

- Testing for emotional intelligence can help with hiring and leadership development.

- Both rational and emotional intelligence have roles to play for “whole” leaders.

Bring a New Perspective to the Office

Being mindful of emotional intelligence in the workplace does more for business leaders than provide them with a greater understanding of current and prospective employees’ skills and capabilities, it also gives them a broader perspective on their business as a whole.

USC’s online Master of Science in Applied Psychology program can help you develop a sophisticated understanding of employee behavior and motivation. The program is uniquely structured to explore human behavior in depth, which can help you develop the tools you’ll need to make informed real-world business decisions that affect both organizational and consumer behavior. Learn how you can help shape the future of business.

Learn how you can help shape the future of business.

Recommended Readings

Change and Organizational Adaptability: Three Challenges

How Cultural Competence in the Workplace Creates Psychological Safety for Employees

Why a Healthy Team Culture Is Important in Hybrid Work Environments

Sources:

Bloomsbury Publishing, “Emotional Intelligence: 25th Anniversary Edition”

Business News Daily, “Emotional Intelligence Skills: How to Spot Them in Hiring”

Howard Gardner, “Frequently Asked Questions: Multiple Intelligences and Related Educational Topics”

International Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, “Importance of Emotional Intelligence in the Workplace”

Journal of Management and Organization, “Building Collaboration in Teams Through Emotional Intelligence: Mediation by SOAR (Strengths, Opportunities, Aspirations, and Results)”

SpringerLink, “Understanding and Developing Emotional Intelligence”

Howard Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences | Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning

- Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning

- Resources

- Guides

- Instructional Guide

- Howard Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences

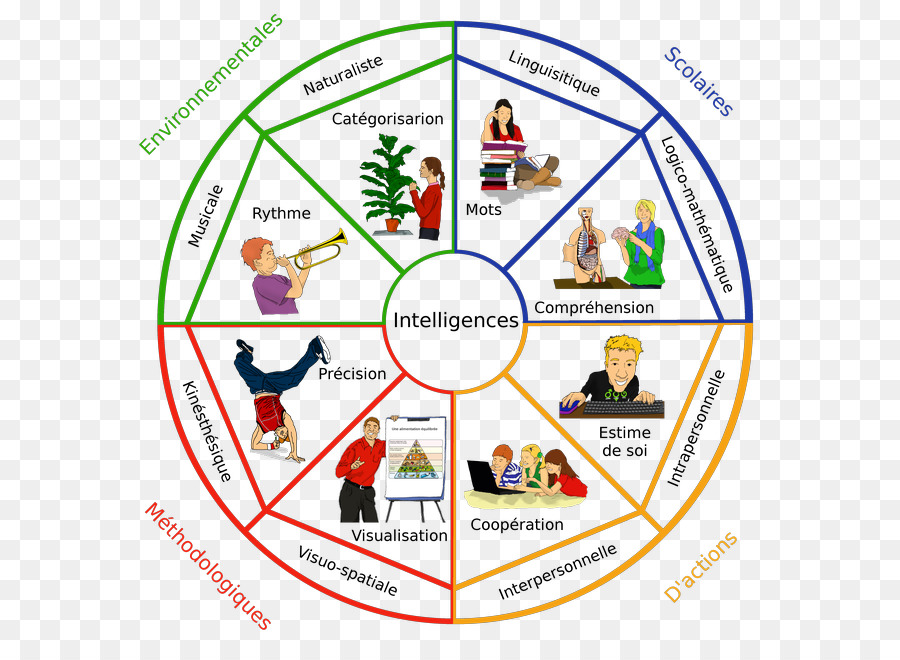

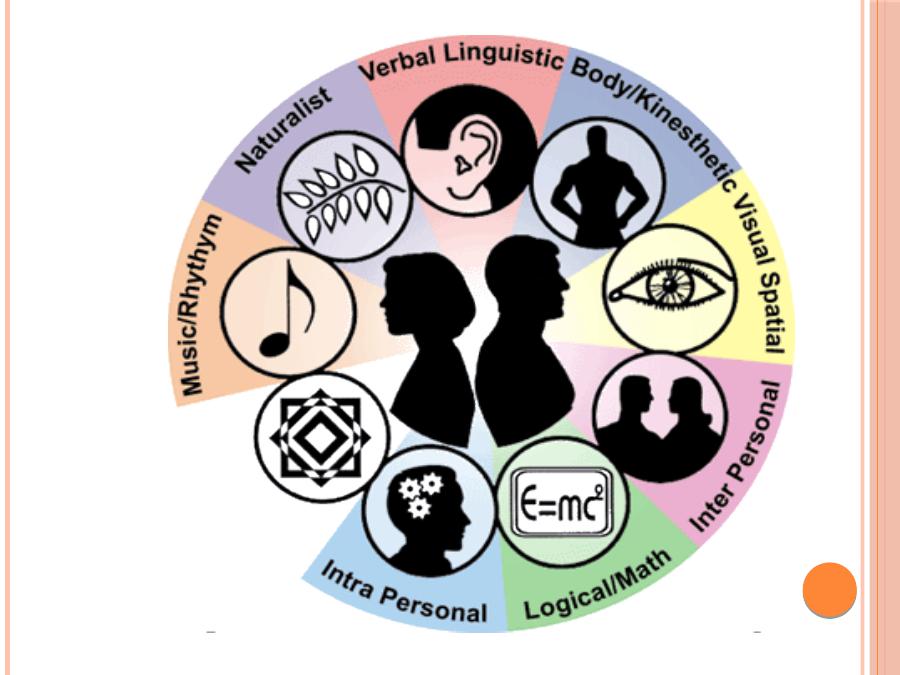

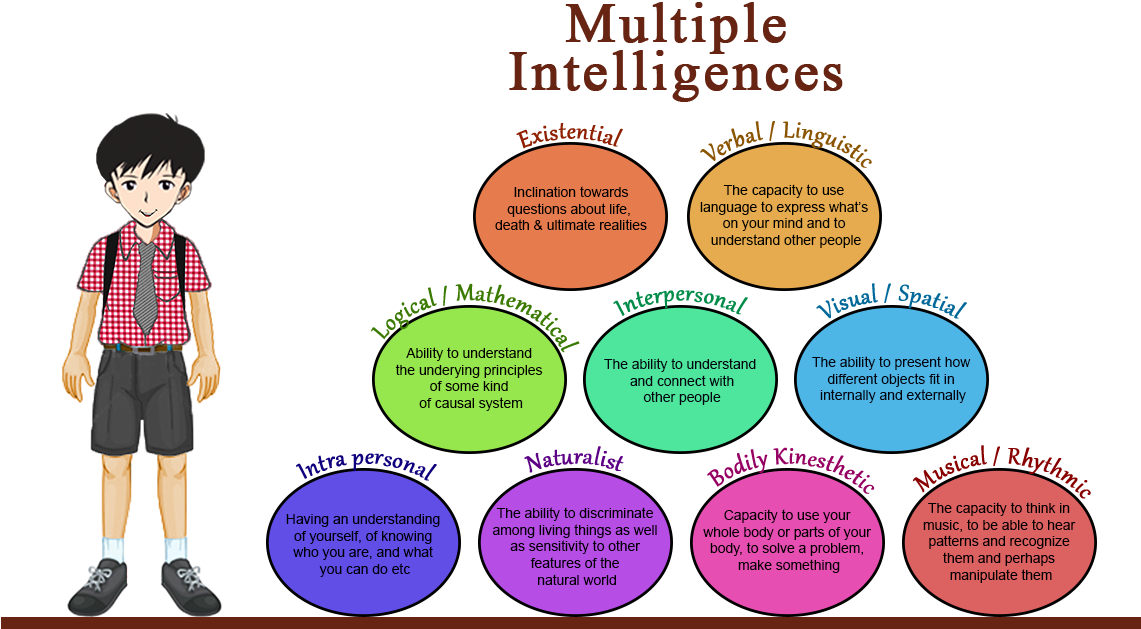

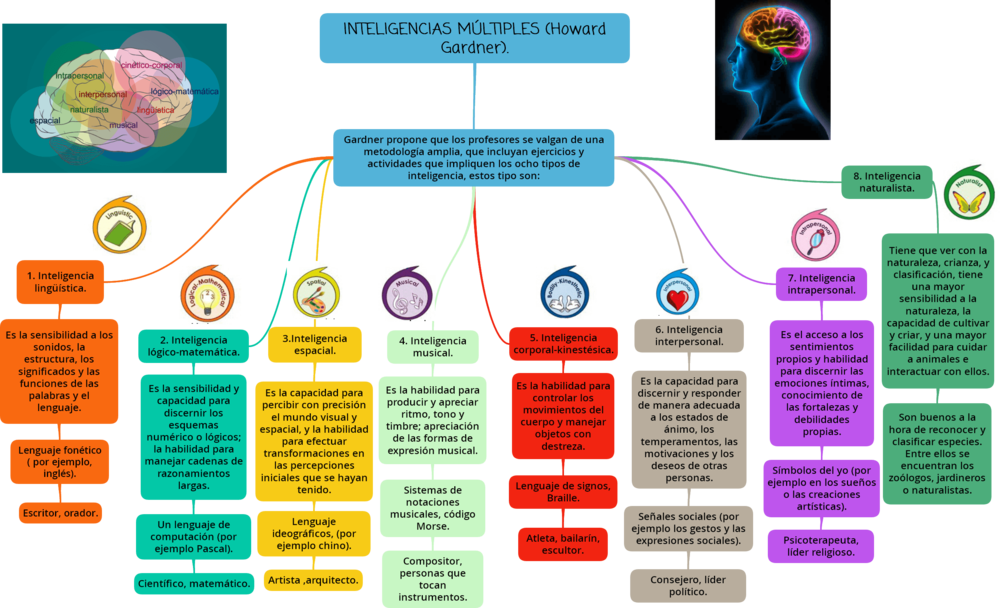

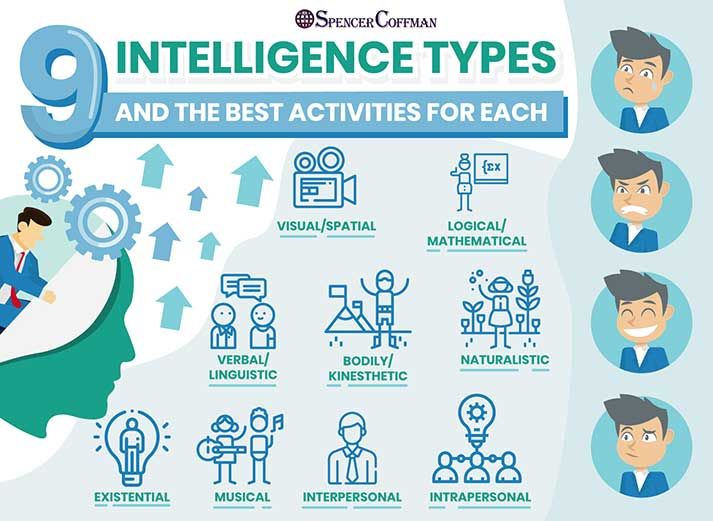

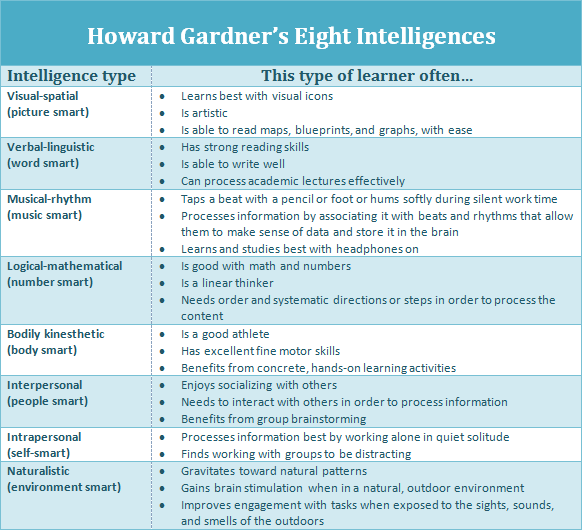

Many of us are familiar with three broad categories in which people learn: visual learning, auditory learning, and kinesthetic learning. Beyond these three categories, many theories of and approaches toward human learning potential have been established. Among them is the theory of multiple intelligences developed by Howard Gardner, Ph.D., John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs Research Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education at Harvard University. Gardner’s early work in psychology and later in human cognition and human potential led to his development of the initial six intelligences. Today there are nine intelligences, and the possibility of others may eventually expand the list.

Beyond these three categories, many theories of and approaches toward human learning potential have been established. Among them is the theory of multiple intelligences developed by Howard Gardner, Ph.D., John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs Research Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education at Harvard University. Gardner’s early work in psychology and later in human cognition and human potential led to his development of the initial six intelligences. Today there are nine intelligences, and the possibility of others may eventually expand the list.

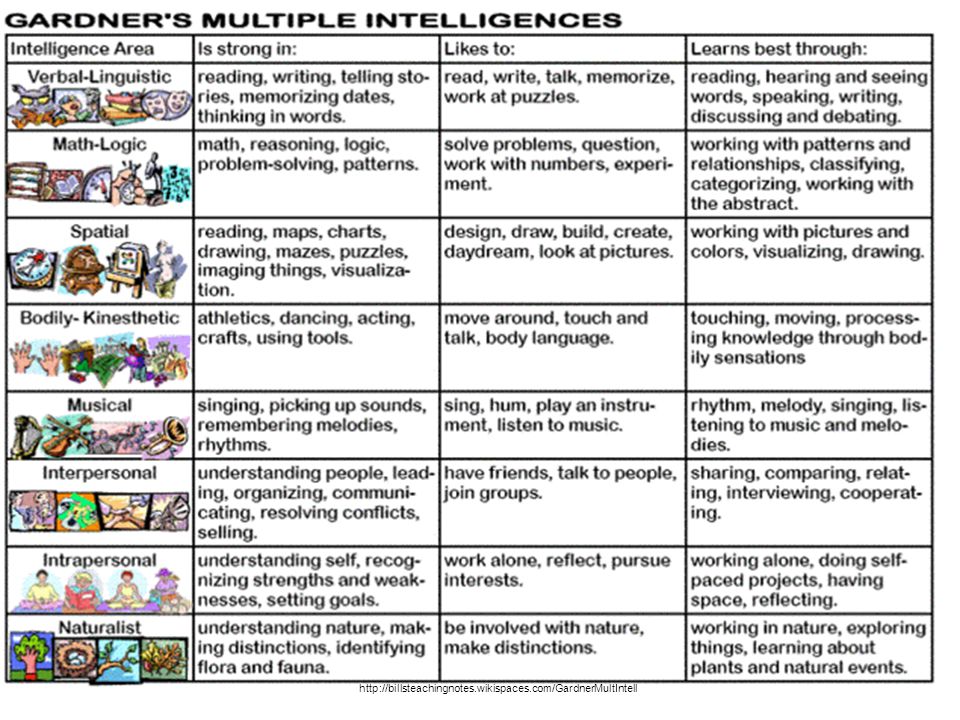

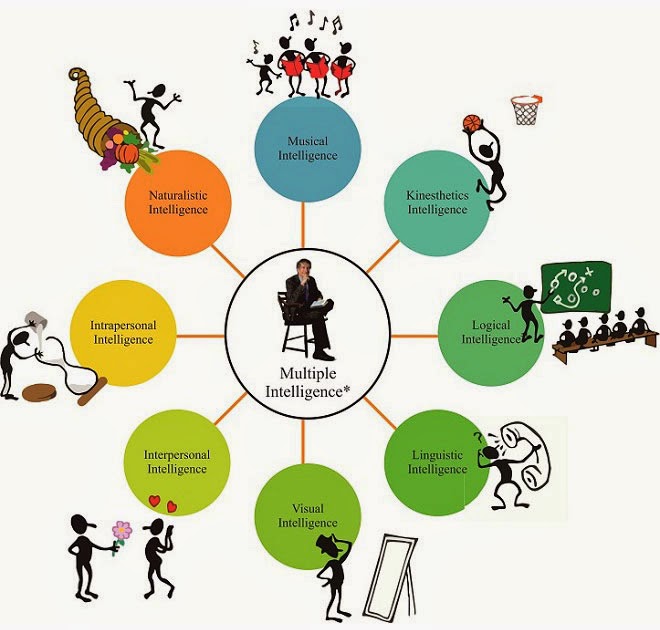

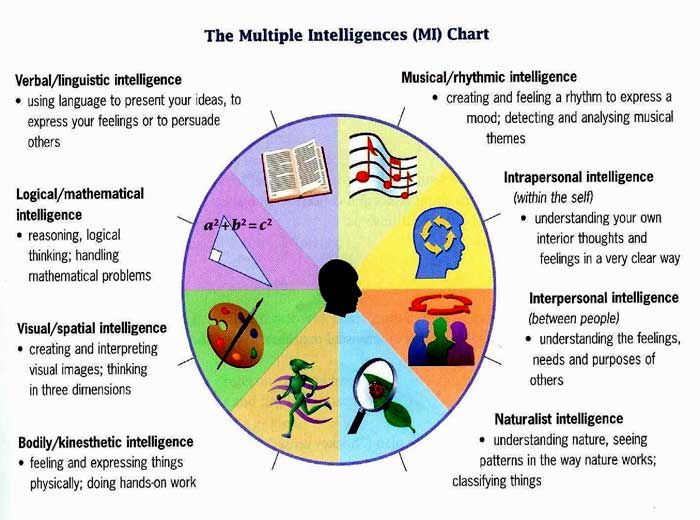

Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences Summarized

- Verbal-linguistic intelligence (well-developed verbal skills and sensitivity to the sounds, meanings and rhythms of words)

- Logical-mathematical intelligence (ability to think conceptually and abstractly, and capacity to discern logical and numerical patterns)

- Spatial-visual intelligence (capacity to think in images and pictures, to visualize accurately and abstractly)

- Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence (ability to control one’s body movements and to handle objects skillfully)

- Musical intelligences (ability to produce and appreciate rhythm, pitch and timber)

- Interpersonal intelligence (capacity to detect and respond appropriately to the moods, motivations and desires of others)

- Intrapersonal (capacity to be self-aware and in tune with inner feelings, values, beliefs and thinking processes)

- Naturalist intelligence (ability to recognize and categorize plants, animals and other objects in nature)

- Existential intelligence (sensitivity and capacity to tackle deep questions about human existence such as, “What is the meaning of life? Why do we die? How did we get here?”

(“Tapping into Multiple Intelligences,” 2004)

Gardner (2013) asserts that regardless of which subject you teach—“the arts, the sciences, history, or math”—you should present learning materials in multiple ways. Gardner goes on to point out that anything you are deeply familiar with “you can describe and convey … in several ways. We teachers discover that sometimes our own mastery of a topic is tenuous, when a student asks us to convey the knowledge in another way and we are stumped.” Thus, conveying information in multiple ways not only helps students learn the material, it also helps educators increase and reinforce our mastery of the content.

Gardner goes on to point out that anything you are deeply familiar with “you can describe and convey … in several ways. We teachers discover that sometimes our own mastery of a topic is tenuous, when a student asks us to convey the knowledge in another way and we are stumped.” Thus, conveying information in multiple ways not only helps students learn the material, it also helps educators increase and reinforce our mastery of the content.

… regardless of which subject you teach—“the arts, the sciences, history, or math”—you should present learning materials in multiple ways.

Gardner’s multiple intelligences theory can be used for curriculum development, planning instruction, selection of course activities, and related assessment strategies. Gardner points out that everyone has strengths and weaknesses in various intelligences, which is why educators should decide how best to present course material given the subject-matter and individual class of students. Indeed, instruction designed to help students learn material in multiple ways can trigger their confidence to develop areas in which they are not as strong. In the end, students’ learning is enhanced when instruction includes a range of meaningful and appropriate methods, activities, and assessments.

Indeed, instruction designed to help students learn material in multiple ways can trigger their confidence to develop areas in which they are not as strong. In the end, students’ learning is enhanced when instruction includes a range of meaningful and appropriate methods, activities, and assessments.

Multiple Intelligences are Not Learning Styles

While Gardner’s MI have been conflated with “learning styles,” Gardner himself denies that they are one in the same. The problem Gardner has expressed with the idea of “learning styles” is that the concept is ill defined and there “is not persuasive evidence that the learning style analysis produces more effective outcomes than a ‘one size fits all approach’” (as cited in Strauss, 2013). As former Assistant Director of Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching Nancy Chick (n.d.) pointed out, “Despite the popularity of learning styles and inventories such as the VARK, it’s important to know that there is no evidence to support the idea that matching activities to one’s learning style improves learning. ” One tip Gardner offers educators is to “pluralize your teaching,” in other words to teach in multiple ways to help students learn, to “convey what it means to understand something well,” and to demonstrate your own understanding. He also recommends we “drop the term ‘styles.’ It will confuse others and it won’t help either you or your students” (as cited in Strauss, 2013).

” One tip Gardner offers educators is to “pluralize your teaching,” in other words to teach in multiple ways to help students learn, to “convey what it means to understand something well,” and to demonstrate your own understanding. He also recommends we “drop the term ‘styles.’ It will confuse others and it won’t help either you or your students” (as cited in Strauss, 2013).

… “pluralize your teaching,” in other words to teach in multiple ways to help students learn, to “convey what it means to understand something well,” and to demonstrate your own understanding.

Summary

Gardner himself asserts that educators should not follow one specific theory or educational innovation when designing instruction but instead employ customized goals and values appropriate to teaching, subject-matter, and student learning needs. Addressing the multiple intelligences can help instructors pluralize their instruction and methods of assessment and enrich student learning.

References

Chick, N. (n.d.). Learning styles. Retrieved from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/learning-styles-preferences/

Gardner, H. (2013). Frequently asked questions—Multiple intelligences and related educational topics. Retrieved from https://howardgardner01.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/faq_march3013.pdf

Strauss, V. (2013, Oct. 16). Howard Gardner: “Multiple intelligences” are not “learning styles.” The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2013/10/16/howard-gardner-multiple-intelligences-are-not-learning-styles/

Tapping into multiple intelligences. (2004). Retrieved from https://www.thirteen.org/edonline/concept2class/mi/index.html

Selected Resources

MI OASIS: The Official Authoritative Site of Multiple Intelligences. Access at https://www.multipleintelligencesoasis.org/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4. 0 International License.

0 International License.

Suggested citation

Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. (2020). Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences. In Instructional guide for university faculty and teaching assistants. Retrieved from https://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guides/instructional-guide

Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences (GWP)

The book "Introduction to Psychology". Authors - R.L. Atkinson, R.S. Atkinson, E.E. Smith, D.J. Boehm, S. Nolen-Hoeksema. Under the general editorship of V.P. Zinchenko. 15th international edition, St. Petersburg, Prime Eurosign, 2007.

Article from chapter 12. Individual differences

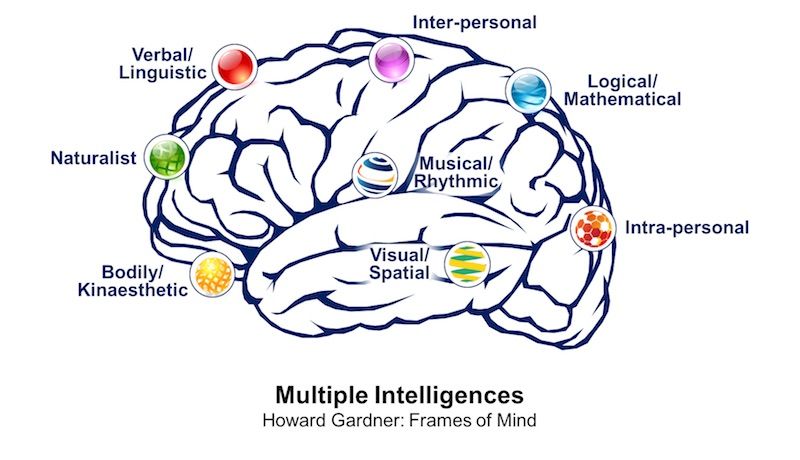

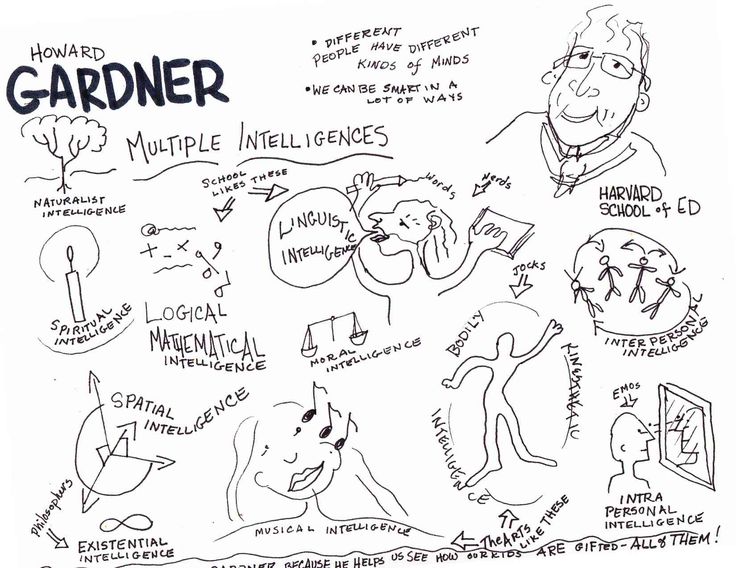

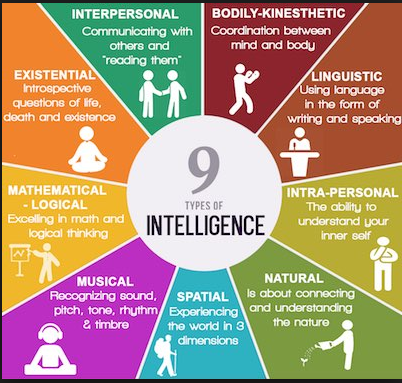

Howard Gardner (Gardner, 1983) developed his theory of multiple intelligences as a radical alternative to what he calls the "classical" view of intelligence as the capacity for logical reasoning.

Gardner was struck by the diversity of adult roles in different cultures—roles based on a wide variety of abilities and skills equally necessary for survival in their respective cultures. Based on his observations, he came to the conclusion that instead of a single basic intellectual ability, or "g factor", there are many different intellectual abilities that occur in various combinations. Gardner defines intelligence as “the ability to solve problems or create products due to specific cultural characteristics or social environment” (1993, p. 15). It is the multiple nature of intelligence that allows people to take on such diverse roles as doctor, farmer, shaman, and dancer (Gardner, 1993a).

Based on his observations, he came to the conclusion that instead of a single basic intellectual ability, or "g factor", there are many different intellectual abilities that occur in various combinations. Gardner defines intelligence as “the ability to solve problems or create products due to specific cultural characteristics or social environment” (1993, p. 15). It is the multiple nature of intelligence that allows people to take on such diverse roles as doctor, farmer, shaman, and dancer (Gardner, 1993a).

Gardner notes that the intellect is not a "thing", not a device located in the head, but "a potential, the presence of which allows the individual to use forms of thinking that are adequate to specific types of context" (Kornhaber & Gardner, 1991, p. 155) . He believes that there are at least 6 different types of intelligence that do not depend on each other and act in the brain as independent systems (or modules), each according to its own rules. These include:

a) linguistic;

b) logical and mathematical;

c) spatial;

d) musical;

e) bodily-kinesthetic and

f) personality modules.

The first three modules are familiar components of intelligence and are measured by standard intelligence tests. The last three, according to Gardner, deserve a similar status, but Western society has emphasized the first three types and virtually excluded the rest. These types of intelligence are described in more detail in the table:

Gardner's Seven Intelligences

(adapted from: Gardner, Kornhaber & Wake, 1996)

- Verbal intelligence is the ability to generate speech, including mechanisms responsible for the phonetic (speech sounds), syntactic (grammar), semantic (meaning) and pragmatic components of speech (the use of speech in various situations).

- Musical intelligence - the ability to generate, transmit and understand the meanings associated with sounds, including the mechanisms responsible for the perception of pitch, rhythm and timbre (qualitative characteristics) of sound.

- Logico-mathematical intelligence - the ability to use and evaluate the relationship between actions or objects when they are not actually present, i.

e. to abstract thinking.

e. to abstract thinking. - Spatial intelligence - the ability to perceive visual and spatial information, modify it and recreate visual images without recourse to the original stimuli. Includes the ability to construct images in three dimensions, as well as mentally move and rotate these images.

- Body-kinesthetic intelligence - the ability to use all parts of the body in solving problems or creating products; includes control over gross and fine motor movements and the ability to manipulate external objects.

- Intrapersonal intelligence - the ability to recognize one's own feelings, intentions and motives.

- Interpersonal intelligence - the ability to recognize and discriminate between the feelings, attitudes and intentions of other people.

In particular, Gardner argues that musical intelligence, including the ability to perceive pitch and rhythm, has been more important than logico-mathematical for most of human history. Body-kinesthetic intelligence includes control of one's body and the ability to skillfully manipulate objects: dancers, gymnasts, artisans, and neurosurgeons are examples. Personal intelligence consists of two parts. Intrapersonal intelligence is the ability to monitor one's feelings and emotions, distinguish between them, and use this information to guide one's actions. Interpersonal intelligence is the ability to notice and understand the needs and intentions of others and monitor their mood in order to predict their future behavior.

Personal intelligence consists of two parts. Intrapersonal intelligence is the ability to monitor one's feelings and emotions, distinguish between them, and use this information to guide one's actions. Interpersonal intelligence is the ability to notice and understand the needs and intentions of others and monitor their mood in order to predict their future behavior.

Gardner analyzes each type of intelligence from several positions: the cognitive operations involved in it; the appearance of child prodigies and other exceptional personalities; data on cases of brain damage; its manifestations in various cultures and the possible course of evolutionary development. For example, with certain brain damage, one type of intelligence may be impaired, while others remain unaffected. Gardner notes that the abilities of adults of different cultures are different combinations of certain types of intelligence.

Although all normal individuals are capable of exhibiting all varieties of intelligence to some degree, each individual has a unique combination of more and less developed intellectual abilities (Walters & Gardner, 1985), which explains the individual differences between people.

As we have noted, conventional IQ tests are good predictors of college grades, but they are less valid in predicting subsequent job success or career advancement. Measures of other abilities, such as personal intelligence, may help explain why some excellent college performers become miserable failures later in life, while less successful students become worship leaders (Kornhaber, Krechevsky & Gardner, 1990). Therefore, Gardner and his colleagues call for an "intellectual-objective" assessment of students' abilities. This will allow children to demonstrate their abilities in ways other than paper tests, such as matching items together to demonstrate spatial imagination skills.

Other theories of intelligence

- Anderson's theory of intelligence and cognitive development See →

- Sternberg's triarchic theory See →

- Cexi Bioecological Theory See→

Theories of intelligence: results

Despite these differences, all theories of intelligence have a number of common features. All of them try to take into account the biological basis of intelligence, whether it be a basic processing mechanism or a set of multiple intellectual abilities, modules or cognitive potentials. See →

All of them try to take into account the biological basis of intelligence, whether it be a basic processing mechanism or a set of multiple intellectual abilities, modules or cognitive potentials. See →

Nine types of intelligence: know yours

1. Visual-spatial intelligence

Not everyone can create 3D models in their head by solving a geometric problem or drawing a three-dimensional image. This ability is typical for people with visual-spatial intelligence.

Strengths: creation of visual and spatial images, easy handling of them.

Characteristics of a person:

- likes to read, write, draw;

- solves puzzles quickly;

- interprets pictures, graphs and diagrams well;

- memorizes maps and navigates the terrain.

Potential career:

- architect;

- artist;

- engineer.

2. Linguistic-verbal intelligence

This kind of intelligence refers to a person's ability to use words effectively to express what he means.

Strengths: effective work with information, rapid learning of languages and writing.

Human characteristics:

- remembers written and oral information well;

- likes to read and can write good text;

- makes persuasive speeches;

- can explain well;

- often uses humor when telling stories.

Potential career:

- writer or journalist;

- lawyer;

- teacher.

3. Logical and mathematical intelligence

Usually the most obvious indicators used in determining intelligence are logical and mathematical abilities. In Gardner's concept, this is one of the types of intelligence.

In Gardner's concept, this is one of the types of intelligence.

Strengths: ability to recognize patterns and analyze information, conceptual thinking and quick math problem solving.

Personal characteristics:

- excellent problem-solving skills;

- thinks abstractly;

- likes to do scientific experiments;

- solves complex calculations well.

Potential career:

- scientist;

- mathematician;

- programmer;

- engineer;

- accountant.

4. Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence

High coordination of consciousness and body is inherent in people with bodily-kinesthetic intelligence.

Strengths: high motor activity, precise coordination, dexterity, tactile memory.

Characteristics of a person:

- dances well and loves sports;

- likes to make things with his own hands;

- excellent physical coordination;

- physical endurance.

Potential career:

- dancer;

- builder;

- sculptor;

- actor.

5. Musical intelligence

If a person has the talent to disassemble musical compositions into elements and track all the instruments that sound in it, then he is the owner of musical intelligence.

Strengths: sense of rhythm, ear and musical talent.

Human characteristics:

- loves to sing and play musical instruments;

- easily guesses musical compositions;

- memorizes songs and melodies well;

- understands musical structure, rhythm and notes.

Potential career:

- musician;

- composer;

- singer;

- music teacher.

6. Interpersonal Intelligence

Interpersonal Intelligence

Emotions are closely related to your intellect. Interpersonal intelligence refers to the ability to sense the feelings of other people as well as understand the motives behind their behavior.

Strengths: empathy and interaction with other people.

Characteristics of a person:

- knows how to evaluate the emotions, motives, desires and intentions of others;

- communicates well;

- is skilled in non-verbal communication;

- sees situations from different points of view;

- creates positive relationships with others;

- is able to resolve conflicts.

Potential career:

- psychologist;

- consultant;

- coach;

- salesman;

- policy

7. Intrapersonal intelligence

Self-awareness is also a form of intelligence. If a person understands himself, his desires, knows what he feels and why he feels it, then we can say with confidence that he has intrapersonal intelligence.

If a person understands himself, his desires, knows what he feels and why he feels it, then we can say with confidence that he has intrapersonal intelligence.

Strengths: introspection and self-reflection.

Characteristics of a person:

- understands his strengths and weaknesses well;

- likes to analyze theories and ideas;

- excellent self-awareness;

- clearly defines his emotional state.

Potential career:

- philosopher;

- writer;

- scientist.

8. Naturalistic intelligence

The ability to “read” and understand nature and all living beings inhabiting it is the main characteristic of naturalistic intelligence.

Strengths: ability to study the environment.

Human characteristics:

- interested in such subjects as botany, biology and zoology;

- categorizes information well;

- can enjoy camping, gardening, hiking and outdoor activities;

- does not like to study unfamiliar topics that are not related to nature.