How to support a friend with an eating disorder

How to Support a Friend with an Eating Disorder

It took me a long time to realize that my best friend had an eating disorder. In the high school cafeteria, our table was always busy joking or studying, and it never even occurred to me to notice how much she was eating. Later, when we were home on break from college, I’d suggest going for a meal out. She would counter with heading to Whole Foods and picking up free samples throughout the store. I thought it was a fun game that fit into our budget as broke college students. It didn’t occur to me that the singular popcorn kernels, the blueberries, or olives on toothpicks were all she would eat that day.

It was only after a vacation we took together that I realized the extent of the situation since we were together for every meal that week. At every meal, she offered to split a dish and I ended up eating the whole thing. Was it me? Was I being a pig? I tried to match my eating habits to hers and my blood sugar plummeted.

This wasn’t normal. I remember thinking: Why hadn’t I noticed this earlier?

I remember returning home and gathering our mutual friends in a coffee shop. “I think she might have an eating disorder,” I said in a hushed voice. My friends stared at me. “Obviously,” one said. “But what can we do?”

The path to supporting a friend with an eating disorder is difficult to navigate because every person, including their needs and their preferences, is unique.Having an eating disorder is a painful, sometimes deadly mental illness. But as I’ve learned over a decade, it also creates a radiating wave of pain through the friends and family who love that person. All those years ago, I thought maybe an intervention or confrontation could heal my friend. I was so wrong – an eating disorder is not something that can be cured by a loving friend yelling in your face, “You’re sick! Don’t you realize it! Let me help you!”. There is no simple fix, and that’s the first lesson.

The path to supporting a friend with an eating disorder is difficult to navigate because every person, including their needs and their preferences, is unique. There are some common threads to be aware of, though.

There are some common threads to be aware of, though.

1. Realize that eating disorders aren’t about food.

Watching someone you love seemingly waste away is heart-wrenching. I remember passing my friend in a locker room once. She was turned away from me, and her back ribs jutted out as she bent over. “Oh my god,” I thought. “That poor person.” Then she turned around and I was shocked to see it was my friend.

It’s tempting to cling to an “easy” solution, like “just eat more!” But that won’t work because eating disorders are not about food. They are about control.

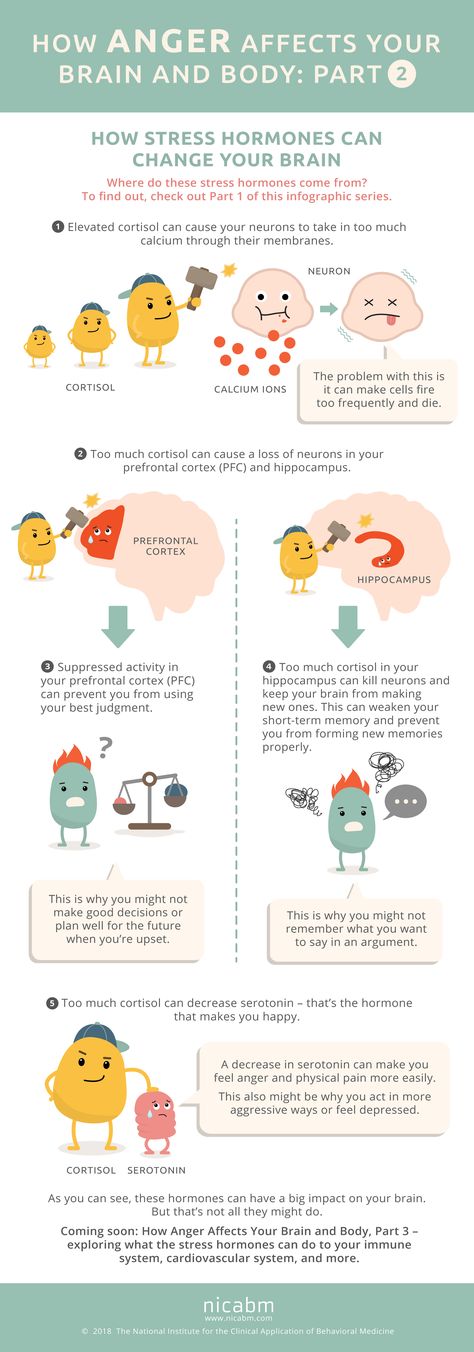

The Temper spoke to Dr. Jaime Coffino, Ph.D., MPH, a clinical psychologist who researches eating disorders, and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at both the NYU Grossman School of Medicine and New York Anxiety Treatment. “People who experience a loss of control in various domains of their life (e.g., work, home, relationships, etc.) may engage in restrictive or compensatory eating behaviors as a coping strategy to deal with negative emotions,” Coffino says. “This perception of control overeating and weight can cause behaviors that spiral into the development of an eating disorder.”

“This perception of control overeating and weight can cause behaviors that spiral into the development of an eating disorder.”

This is to say that your friend might feel a lack of control in their life, and controlling their food intake or their body appearance is their way of clawing back control. There might be external stressors that trigger an eating disorder, and this probably has absolutely nothing to do with food itself.

2. Speaking out is important — but it matters how you do it.

With the perspective of control as the cause of eating disorders, you can see why telling or asking someone with an eating disorder to “please eat more” does not address the root of their issue. In fact, asking your friend to eat more will just draw more attention to the disordered behavior and place the blame on them.

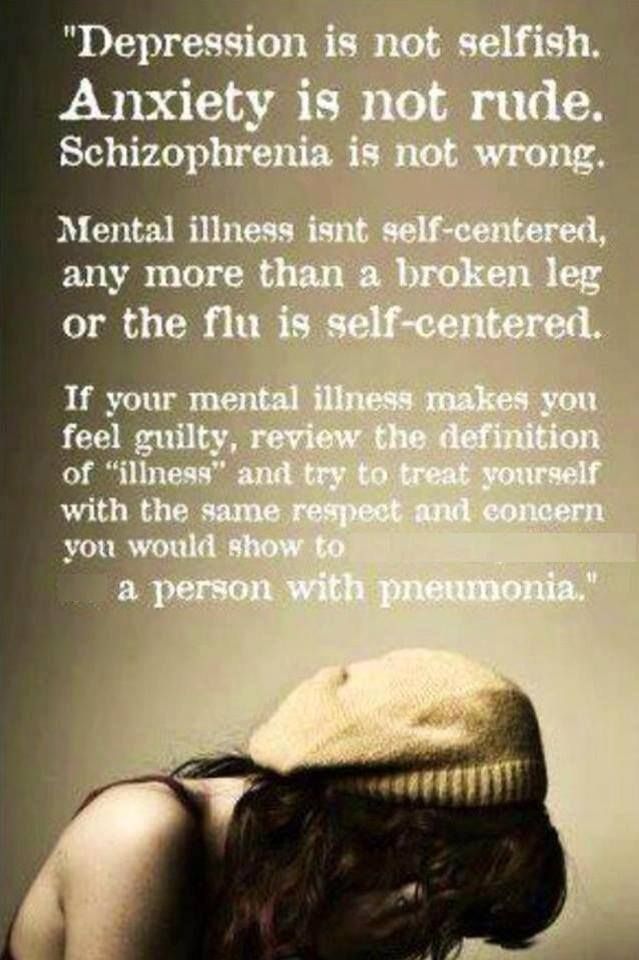

Remember: It’s not their fault. An eating disorder is a mental illness, and it is something external to your friend. The disorder is not your friend themselves. It is painful to see a loved one suffer but remember they are not making these choices willfully; they are sick.

It is painful to see a loved one suffer but remember they are not making these choices willfully; they are sick.

Letting your friend know that you’ve noticed their patterns, that you’re worried about them, and that you care for them is all really important. Eating disorders can be deadly, so it is also important to speak out to keep your friend safe — although you shouldn’t put the entire responsibility for their safety on your shoulders or you risk damaging your own mental health.

Speaking out is important for all those reasons but it will only be effective if you approach the conversation in a sensitive and educated way. It’s important to choose a good time to speak one-on-one and not overwhelm your friend like it’s a confrontation. Talking about your own feelings and concerns, and not focusing the conversation just on food intake, will also take some of the pressure or feelings of accusation off your friend. It has always helped me to rehearse the conversations, or write down points, before I speak to my friend.

3. Encourage your friend to seek help.

As I learned from the first time I ever approached my best friend about her eating disorder, being met with denial, anger, and defensiveness is very common. I remember feeling angry at her response, and so frustrated and desperate that she was unwilling to acknowledge what I so clearly saw before me.

According to Coffino, this is very common. “It is important to be patient and supportive during your conversation because you may be met with resistance,” she explains. Coffino’s research shows how help-seeking behaviors might be impacted by a person’s gender or race or ethnicity, so this is another important factor to consider when broaching the topic with your friend. I personally found these conversations very difficult, but Coffino’s advice is to share “genuine concern” for your friend’s wellbeing and maintain an “open and vulnerable” conversation as best you can.

What I’ve learned over time is that what was painful for me was 100 times more painful for her. She was meticulously covering up her disordered eating patterns yet hadn’t even acknowledged what was happening to herself. To her, I was a threat to the only strand of control she had left.

She was meticulously covering up her disordered eating patterns yet hadn’t even acknowledged what was happening to herself. To her, I was a threat to the only strand of control she had left.

Over time, I’ve learned about the Stages of Change — a concept used in many settings, but particularly relevant to eating disorders. There are five stages of change:

- Pre-contemplation

- Contemplation

- Preparation and determination

- Action

- Maintenance

What stage of change your friend is currently in will determine how they react to you speaking out, and also the appropriate ways for you to encourage your friend to seek help.

What I’ve learned over time is that what was painful for me was 100 times more painful for her.When I first spoke to my friend, and she was defensive and in denial about having an eating disorder, she was in the pre-contemplation stage. Asking someone in this stage to seek help will not be effective because that person does not acknowledge that they have a problem that needs helping. However, as I found, it’s still important to gently and respectfully speak out because this might plant the seed of change that they need.

However, as I found, it’s still important to gently and respectfully speak out because this might plant the seed of change that they need.

If your loved one is in the pre-contemplation stage, but you are seriously worried for their life, you can speak to their family, a school counselor if you are in school or university, or a mental health professional. If your friend is over 18, it is difficult to “force” them into life-saving treatment, but there are still actions you can take. Know, however, that ultimately change is something a person has to desire in themselves in order for treatment to be effective. Forcing treatment on an unwilling person is not necessarily the answer.

4. Staying supportive through your friend’s recovery.

Along the latter stages of change, it is important to encourage your friend to seek help — through therapy, recovery retreats, doctor’s visits, or eating disorder support groups, and support them as they do so.

But as I found, it is also really important to know that ultimately it is up to your friend to make these changes. All you can do is love and support them, but placing the blame or sole responsibility for their health on your own shoulders is both inaccurate and harmful.

All you can do is love and support them, but placing the blame or sole responsibility for their health on your own shoulders is both inaccurate and harmful.

Coffino’s advice is to be direct when asking your friend what type of support they need. “Let them know you are available to listen to them,” she explains. Additionally, Coffino says that “when engaging in conversations, avoid commenting on their weight or shape, or using triggering language such as ‘it’s okay, just eat’.”

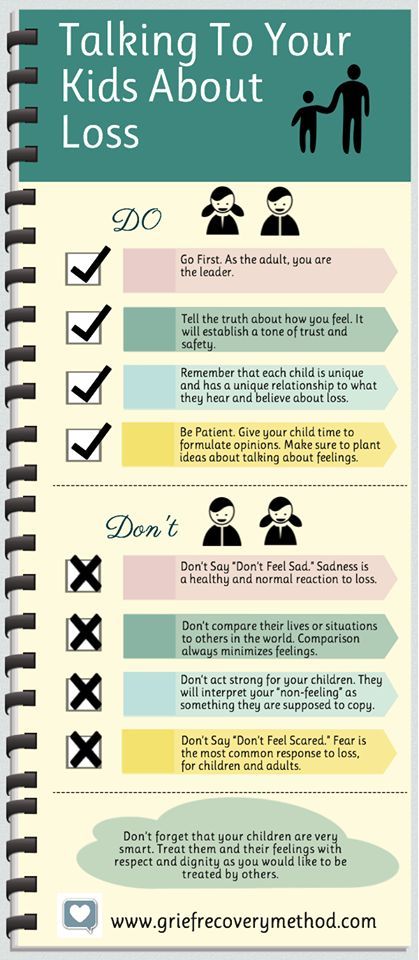

If your friend has chosen to seek help, this is something you should encourage and let them know how proud you are of them. You can continue to support them by:

- Not focusing conversations or activities around food

- Not talking about bodies or body image

- Don’t comment on their weight — whether it’s a loss or gain

- Ask about their reasons for change and support these

- Do activities together that boost self-esteem

- Don’t force them to eat or blame them for their behavior

- Listen to them when they are ready to talk, but don’t force an intervention

- Ask open-ended questions and let them guide to conversations when they’re ready

5.

Remember it’s not your fault.

Remember it’s not your fault.As I know personally, it is heartbreaking to watch a friend suffer. I regretted and blamed myself for years because I did not recognize my friend’s eating disorder sooner. “I could’ve changed everything, I could have helped her, she wouldn’t be in this situation now,” I used to tell myself.

I know it’s hard, but if you are also experiencing these thought patterns, it’s important to shift your perspective. It is not your fault that your friend is still sick, and it is not even your responsibility to “fix” them. An eating disorder is often a lifelong mental illness that your friend will learn to recover from, but still battle daily. There is no simple fix, and it certainly isn’t up to you. All you can do is support your friend, and be there for them when they need you.

I learned these tips through trial and error, supporting my best friend through over a decade of her eating disorder. If someone in your own life has an eating disorder, my heart goes out to both you and them. Hopefully, with this advice in mind, you will feel prepared to both support your friend, and uphold your own mental health.

Hopefully, with this advice in mind, you will feel prepared to both support your friend, and uphold your own mental health.

MORE POSTS

How to Support Someone Struggling With An Eating Disorder

Written by Lilianna Hogan

Medically Reviewed by Melinda Ratini, DO, MS on September 09, 2021

In this Article

- Ways to Help Without Directly Speaking to Them About It

- How to Speak to Someone With an Eating Disorder

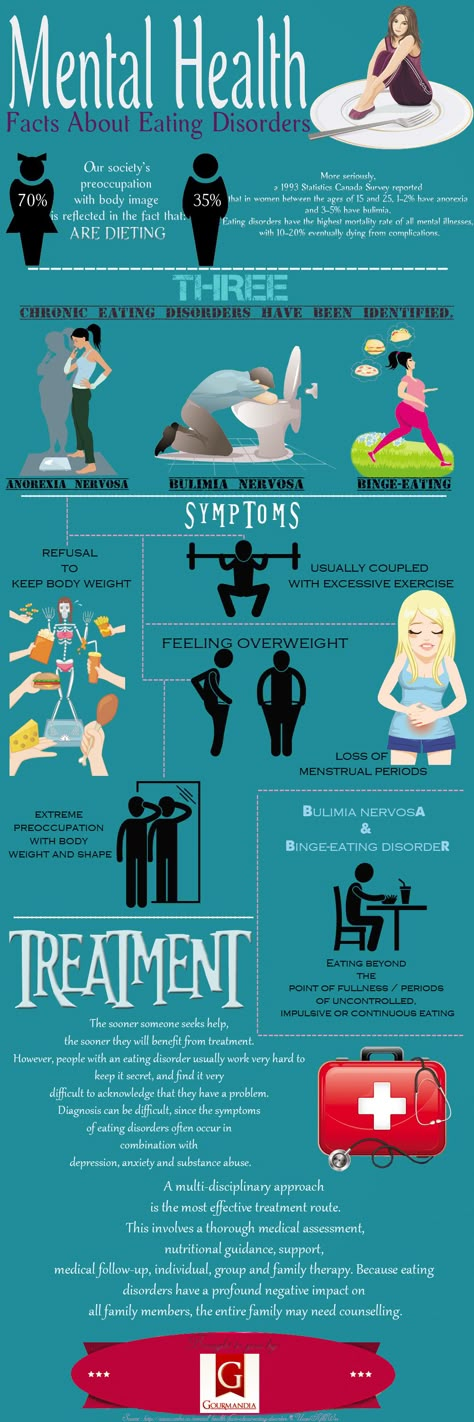

Being in the grips of an eating disorder can disrupt someone’s mind in a very real way. They may or may not realize that they have this problem. If they do acknowledge it, they may have conflicting feelings about seeking treatment or changing their behavior. That's why friends and family can often play a key role in helping those with eating disorders get the help they need.

Ways to Help Without Directly Speaking to Them About It

Oftentimes, your family member or friend might not realize or accept that they have an eating disorder. The best chance for treating this problem is by speaking with a mental healthcare professional.

The best chance for treating this problem is by speaking with a mental healthcare professional.

Here are some ways you can guide your friend or family member toward seeking help without directly speaking to them about it.

- Continue to let them know they're welcome. This person may be in a place where they're self-isolating. It may be hard to encourage them to engage in the outside world. But keep trying. Even if they say no, being invited will let them know you still value them as a person.

- Shower them with love. Telling them how much you love them and appreciate them can build their self-esteem and help them through this challenging time in their life.

- Listen to them. This may be difficult, but simply giving them your time and listening to them without judgment can mean the world to them. It can be tough to hear them speak about themselves and what they eat but not giving advice or passing judgment is what's important.

Offering support is essential, and you can do this indirectly by:

- Understanding that their eating disorder is not your fault.

- Understanding how hard this affliction is for them.

- Educating yourself about eating disorders from reputable sources.

- Avoiding talk about body image, weight loss, diets, or other related topics.

- Modeling healthy behaviors around food, eating, and body image.

- Reminding yourself that recovery is always possible and that things can change for your friend or loved one.

- Taking stock of any behaviors you exhibit that directly accommodate or enable your friend or loved one's eating disorder.

How to Speak to Someone With an Eating Disorder

If you're ready and feel the time is right to speak with your friend or loved one about their eating disorder, here are some tips that may help:

- Think of what you'll say beforehand. Writing down what you want to say or rehearsing what you'll say helps.

That way, you'll be less anxious as you speak to your friend or loved one, and your thoughts will be more clear.

That way, you'll be less anxious as you speak to your friend or loved one, and your thoughts will be more clear. - Create the time and space. Make sure there's a private, safe place to talk. These issues are very sensitive and you don’t want any outside distractions to interrupt your conversation.

- Share your experience with honesty. Honestly let them know how concerned you are for their safety. Holding back will not help.

- Stick to using “I” statements. Sticking to your own experience by structuring all your statements with "I" is very helpful. Otherwise, you risk sounding accusatory and making your friend or loved one feel attacked or shamed.

- Remember the facts. Discussing someone’s eating disorder with them can stir up several conflicting emotions. Always bring things back to the facts of the situation, like things you've observed and why those things alarm or upset you, so that you can keep your conversation on a more productive track.

- Love them but hold your ground. Being loving doesn’t always mean being sweet. Don't let your friend manipulate you. Avoid making extreme rules, promises, or expectations that are not helpful.

- Let them know they're not judged. Eating disorders carry an incredible amount of stigma and shame with them. Remind your loved one there's no shame in admitting that they struggle with an eating disorder.

- Don’t give them simple remedies. Simply telling your friend or loved one to start eating and stop having an eating disorder isn't helpful. Most likely, they'll walk away from the conversation feeling unseen, unheard, and defensive.

- Know that you could face a very negative reaction. From anger to disbelief to denial, there can be a whole range of negative responses to raising your concerns over another person’s eating disorder. Be prepared for this person to react unkindly to you.

- Research treatment options ahead of your conversation.

Seeking professional help increases the likelihood of recovery from an eating disorder. Sharing your research with your friend or loved one might help them understand the problem and find the right treatment option.

Seeking professional help increases the likelihood of recovery from an eating disorder. Sharing your research with your friend or loved one might help them understand the problem and find the right treatment option.

5 Ways to Support the Person with an Eating Disorder » MAKEOUT - A Gender & Sexuality Magazine

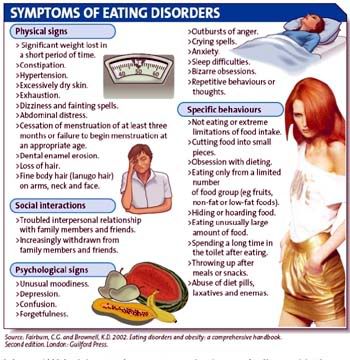

Eating Disorder Recovery (EDD) is, simply put, a long-term effort to give up erratic eating behavior for the sake of your health. And most often this process is felt as a constant balancing somewhere “on the edge”.Constantly surrounded by things that can trigger a relapse, many people recovering from eating disorders behave in the same way as those who struggle with alcohol addiction: they are "stuck" in a world where their destructive behavior can easily return.

The need to constantly be strong in order to fight bad thoughts and self-destructive actions is debilitating. One wrong decision can be a disaster. Therefore, a supportive environment is very important on the path to recovery.

But where do I start? How to organize a safe space for someone you love? This article can be a good starting point.

While I hope that people with eating disorders find it useful (and share it with their loved ones), it is not primarily intended for them.

To be precise, this article is written for those who say, “I know that my friend or someone in my family has an eating disorder. What should I do now?

1. Find out more

Before supporting a loved one in need, it is important to deal with your prejudices and delusions on your own. You can find a book about eating disorders, watch a documentary, or find personal stories of people with eating disorders online. Harriet Brown's Brave Girl Eating (2010) and Laurie Holes Andersen's Wintergirls (2010) are my favorite books. And then there is the documentary film "THIN" ("Anorexia", 2006): it shows the life of rehabilitation centers without embellishment.

You can look at informal online resources (such as social media groups) about eating disorders if you want to know how some people with these disorders think, but don't jump to conclusions about your loved one's experience based on information from such sources. Remember, your lover should not be the first and only source of information about what it's like to experience or recover from an eating disorder. There are thousands of resources that can be found just by googling. A little effort in self-education will serve you well in the future.

Remember, your lover should not be the first and only source of information about what it's like to experience or recover from an eating disorder. There are thousands of resources that can be found just by googling. A little effort in self-education will serve you well in the future.

2. Be a good ally

Be present in the life of your loved one, but don't pressure them. Listen if she needs it, but don't make her say something if she doesn't want to. Try not to criticize or judge the words of your loved one, even if you find it hard to contain yourself. Count to 5 (or 10 or even 20!) before answering. Avoid unsolicited advice.

Remember, a person with eating disorders needs to regain his independence.

Try to figure out her feelings together and work with their manifestations. Talk about your feelings and formulate your wishes based on your own thoughts and emotions, trying not to offend or blame others. Try to do this with the help of personal pronouns: "I", "me", "me". Ask your loved one to do the same. If you want to offer something, do it gently, without pressure, without saying that he "should" do something. If you don't understand something or want to know more information, just ask.

Ask your loved one to do the same. If you want to offer something, do it gently, without pressure, without saying that he "should" do something. If you don't understand something or want to know more information, just ask.

But always be prepared for the fact that the person you love may not want to discuss certain things. Try to approach the questions in a casual manner: “Do you mind if I ask you a few questions? You don't have to answer if you don't want to." Be sympathetic, but collected.

3. Avoid talking about physicality

Don't draw attention to her body, don't try to deal with her experience by talking about her own weight or body. Phrases such as "I would like a figure like yours!" or "I already think you're beautiful" may seem supportive, but they can also be harmful to a person in remission.

Your kind compliments may sound very different to her, so it's best to avoid them. Remember! What seems like a passing remark about your own body (such as "Those jeans got big on me" or "I feel so fat today") can be a trigger for a person with an eating disorder.

Instead, focus on accomplishments and character traits that are not related to the body. Take your attention away from the physical. This is difficult to do in a culture where we are constantly open about the body (especially our dissatisfaction with it), so it may take some effort.

©Wendy van Santen4. Be sensitive to the amount of food

Food and quantity can be very stressful for people with eating disorders. Keep this in mind when planning, for example, gifts or activities (friendly advice: going out to eat or go shopping are not the best ideas). If you are eating in front of a person with an eating disorder, avoid talking about the food (“You can afford to eat more” or “You can order more than just a salad”).

Numbers often define (and therefore worry about) people with eating disorders. People in remission find it difficult to rewire their thinking to stop making constant calculations. Therefore, you'd better avoid any statements about food, weight, calories, etc. (“I lost 5 kg” or “There are 600 calories in this dish”). Think about what you are saying.

(“I lost 5 kg” or “There are 600 calories in this dish”). Think about what you are saying.

When in doubt, ask the person about her triggers.

5. Recognize accomplishments, but do so tactfully

When a person is in remission, they (finally!) begin to overcome their aversion to food and stabilize their weight. When your loved one overcomes the fear of food and reaches the desired weight, it is worth celebrating. But think twice how this holiday is worth celebrating.

Remember point number 3: avoid talking about the body. When you say to someone who has (had) an eating disorder, "you look so healthy!", he may interpret it as "you look fat". Focus on the achievement itself, not on its external manifestations. A simple “I’m proud of you” or “You did a great job, keep going” will be better.

©Wendy van SantenBONUS: Remember to take care of yourself

You are not responsible for someone else's treatment. It's not in your power. Being close to those who need support is a sincere act of caring. You are doing something really important for a person.

Being close to those who need support is a sincere act of caring. You are doing something really important for a person.

But don't forget your own needs. It's okay if the current situation starts to put pressure on you. It's okay if you need to take a step back. It's okay if you're confused, if you have questions. Take care of yourself. The most important thing is that you are trying to help.

Eating is very hard not only for the person, but also for those who try to be around. It's complicated. And all people are different.

But no matter how different people with eating disorders are, they all want their loved ones to know that the best way to support a person with eating disorders is to ask what she needs and be honest in her answers, reactions and assessment of her abilities.

Communication Skills for Families - Eating Disorder

No one teaches us how to properly support a loved one with an eating disorder. While there are many helpful and informative books on the subject, the sheer volume of material can be shocking, in addition to the stress associated with a loved one's illness. This is why it is so important to know the basic communication skills for an eating disorder.

This is why it is so important to know the basic communication skills for an eating disorder.

Here are some quick communication skills to help you get comfortable in your new role and understand what's going on with your loved one if they have an eating disorder.

Act with love

Fortunately, this is exactly what you already know how to do. Eating disorders control the sufferer by instilling fear, darkness, helplessness and despair. Is there a better way to deal with this than showering them with unconditional, nonjudgmental and inspiring love? When you approach EDI (Eating Disorders Individual), use love as your guide and follow this golden rule in all your activities.

If you are frustrated by your loved one's rigid thinking or eating habits, exhausted and overwhelmed by their treatment, and don't know how to help them, start with love.

Be open to learning and let you be taught

Many people know little about eating disorders until they themselves or their loved ones experience the disease. You are not expected to immediately learn all about eating disorders, but EDI communication skills will certainly help in learning.

You are not expected to immediately learn all about eating disorders, but EDI communication skills will certainly help in learning.

Browse articles or look for answers to questions you have about a particular disorder. In addition, it will be great if your loved one tells you about his personal experience, and you can find in a conversation with him why he might feel this way right now. Some of it may be the same as what you read, and some of it may be unique to their experience of dealing with the disease, and this knowledge will help you support your loved one in the way they need.

Don't judge

This is very important. Feeling constantly judged will cause an eating disorder sufferer to build a wall and isolate themselves from others. Especially during the period when he is most vulnerable. Make sure you communicate without judgment as you listen to your loved one's story and help them through their healing and recovery process.

Provide yourself with support

It is equally important to have your own support in the process of treatment to maintain a positive attitude.