How to stop yourself being hungry

13 Ways to Help Curb Appetite, According to Science

Hunger and appetite are something each of us knows quite well.

For the most part, we navigate these biological processes continuously throughout the day, even when we don’t realize we’re doing so.

Generally, hunger and appetite are signals from your body that it needs energy or is craving a certain type of food.

While feeling hungry is a normal sign from your body that it’s time to eat again, it’s not fun to constantly feel hungry, especially if you’ve just finished a meal. That may be a sign you’re not eating enough or not eating the right combinations of foods.

If you’re trying to lose weight, living with certain health conditions, or adopting a new meal routine like intermittent fasting, you may be wondering how to reduce feelings of hunger throughout the day (1).

Hunger and appetite are complicated processes though, and they’re influenced by many internal and external factors — which can make reducing either one difficult at times.

To make it easier, we put together this list of 13 science-based ways to help reduce hunger and appetite.

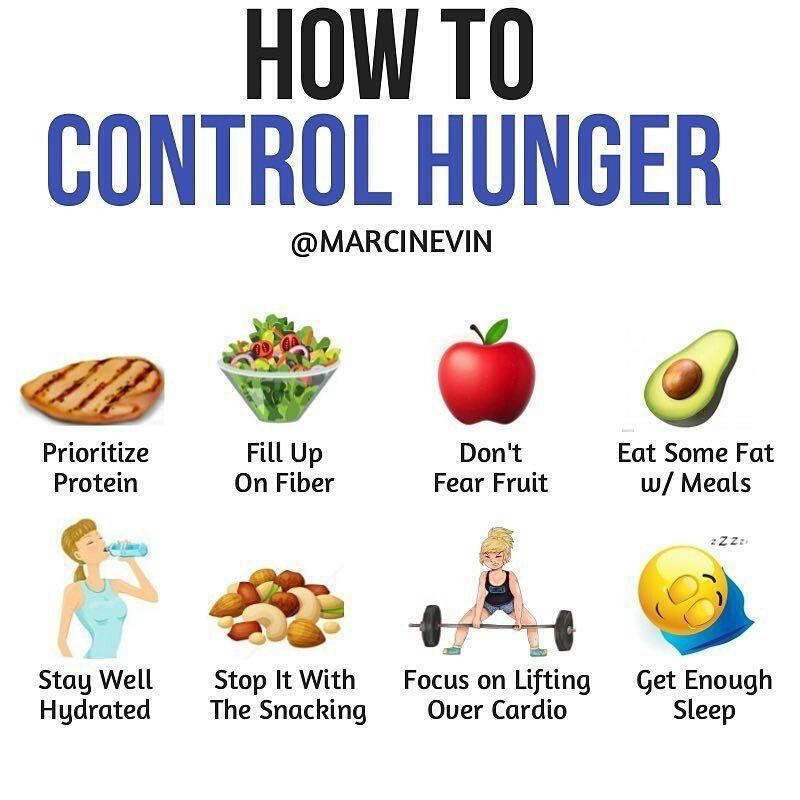

1. Eat enough protein

Adding more protein to your diet can increase feelings of fullness, lower hunger hormone levels, and potentially help you eat less at your next meal (2, 3, 4, 5).

In a small study including 20 healthy adults with overweight or obesity, those who ate eggs (a high protein food) instead of cereal (a lower protein food) experienced increased feelings of fullness and lowered hunger hormones after breakfast (5).

Another study including 50 adults with overweight found that drinking a beverage high in protein and fiber 30 minutes prior to eating pizza appeared to reduce feelings of hunger, as well as the amount of pizza the participants ate (2).

The appetite-suppressing effects of protein aren’t just limited to animal sources like meats and eggs either. Vegetable proteins including beans and peas might be just as useful for keeping you satisfied and moderating your intake (6, 7).

Getting at least 20–30% of your total calorie intake from protein, or 0.45-0.55 grams per pound (1.0–1.2 grams per kg) of body weight, is sufficient to provide health benefits. Yet, some studies suggest up to 0.55–0.73 grams per pound (1.2–1.6 grams per kg) of body weight (8, 9, 10).

Still, other studies have found conflicting results when it comes to high protein diets (11, 12, 13).

Thus, it’s important to remember that there may be another type of diet that better suits your dietary habits and personal preferences.

SUMMARYProtein is a nutrient that helps keep you full. Getting sufficient protein in your diet is important for many reasons, but it may help promote weight loss, partly by decreasing your appetite.

2. Opt for fiber-rich foods

A high fiber intake helps fill you up by slowing digestion and influencing the release of fullness hormones that increase satiety and regulate appetite (3, 14, 15).

In addition, eating fiber helps produce short-chain fatty acids in your gut, which are believed to further promote feelings of fullness (16, 17, 18, 19).

Viscous fibers like pectin, guar gum, and psyllium thicken when they’re mixed with liquids and might be especially filling. Viscous fibers occur naturally in plant foods but are also commonly used as supplements (14, 20, 21, 22).

A recent review even reports that viscous, fiber-rich beans, peas, chickpeas, and lentils can increase feelings of fullness by 31%, compared with equivalent meals not based on beans. Fiber-rich whole grains can also help reduce hunger (19, 23).

Still, the methods of studies examining how dietary fiber intake influences appetite have not always been consistent, and some researchers believe it’s too soon to make generalizations about the relationship between fiber and appetite (24).

Nevertheless, few negative effects have been linked to high fiber diets. Fiber-rich foods often contain many other beneficial nutrients, including vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and helpful plant compounds (25, 26, 27).

Therefore, opting for a diet containing sufficient fruits, vegetables, beans, nuts, and seeds can also promote long-term health. What’s more, pairing protein together with fiber might provide double the benefits for fullness and appetite (28, 29, 30, 31).

SUMMARYEating a fiber-rich diet can decrease hunger and help you eat fewer calories. It also promotes long-term health.

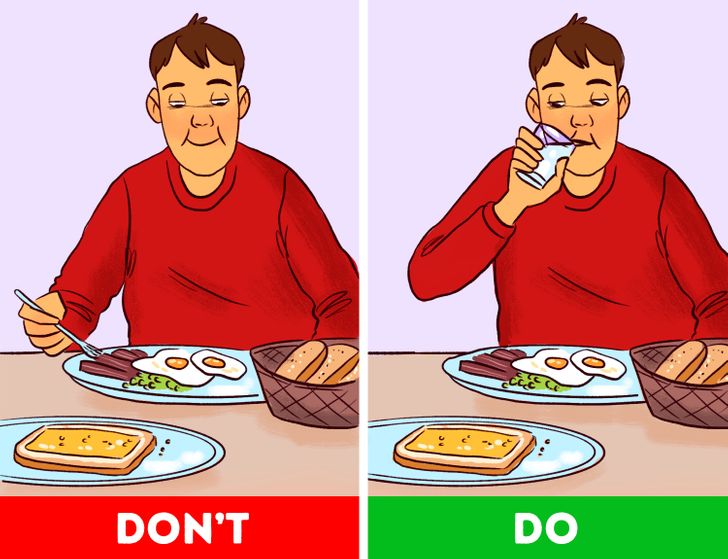

Anecdotal evidence suggests that drinking water might suppress hunger and promote weight loss for some people. Animal studies have also found that thirst is sometimes confused with hunger (32, 33).

One small human study found that people who drank 2 glasses of water immediately before a meal ate 22% less than those who didn’t (34).

Scientists believe that about 17 ounces (500 mL) of water may stretch the stomach and send signals of fullness to the brain. Since water empties from the stomach quickly, this tip may work best when you have water as close to the meal as possible (34).

Interestingly, starting your meal with a broth-based soup may act in the same way. In an older study, researchers observed that eating a bowl of soup before a meal lowered hunger and reduced total calorie intake from the meal by about 100 calories (35).

This may not be the case for everyone though. Genetics, the type of soup you eat, and various other factors are all at play. For example, soups with savory umami flavor profiles might be more satiating than others (36, 37, 38).

While the neurons that regulate your appetite for both water and food are closely related, there’s still much to be learned about how exactly they interact and why drinking water might also satisfy your hunger or appetite for solid foods (39, 40, 41, 42).

Some studies have found that thirst status and water intake appear to influence your preferences for certain foods more than it influences hunger and how much food you eat (41, 43, 44).

While it’s important to stay hydrated — drinking water shouldn’t replace your meal. In general, keep a glass of water with you and sip it during meals or have a glass before you sit down to eat.

In general, keep a glass of water with you and sip it during meals or have a glass before you sit down to eat.

SUMMARYDrinking low calorie liquids or having a cup of soup before a meal may help you eat fewer calories without leaving you hungry.

Solid calories and liquid calories may affect your appetite and your brain’s reward system differently (45, 46).

Two recent research reviews found that solid foods and those with a higher viscosity — or thickness — significantly reduced hunger compared with thin and liquid foods (47, 48, 49).

In one small study, those who ate a lunch comprising hard foods (white rice and raw vegetables) ate fewer calories at lunch and their next meal compared with those who ate a lunch comprising soft foods (risotto and boiled veggies) (50).

Another study found that people who ate foods with more complex textures ate significantly less food during the meal overall (51).

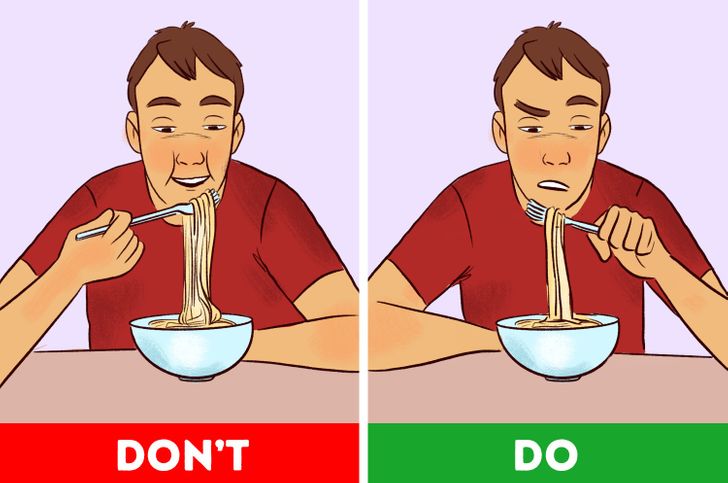

Solid foods require more chewing, which might grant more time for the fullness signal to reach the brain. On the other hand, softer foods are quick to consume in large bites and may be easier to overeat (52, 53, 54).

On the other hand, softer foods are quick to consume in large bites and may be easier to overeat (52, 53, 54).

Another theory as to why solid food help reduce hunger is that the extra chewing time allows solids to stay in contact with your taste buds for longer, which can also promote feelings of fullness (55).

Aim to include a variety of textures and flavors in your meal to stay satisfied and get a wide variety of nutrients.

SUMMARYEating thick, texture-rich foods rather than thin or liquid calories can help you eat less without feeling more hungry.

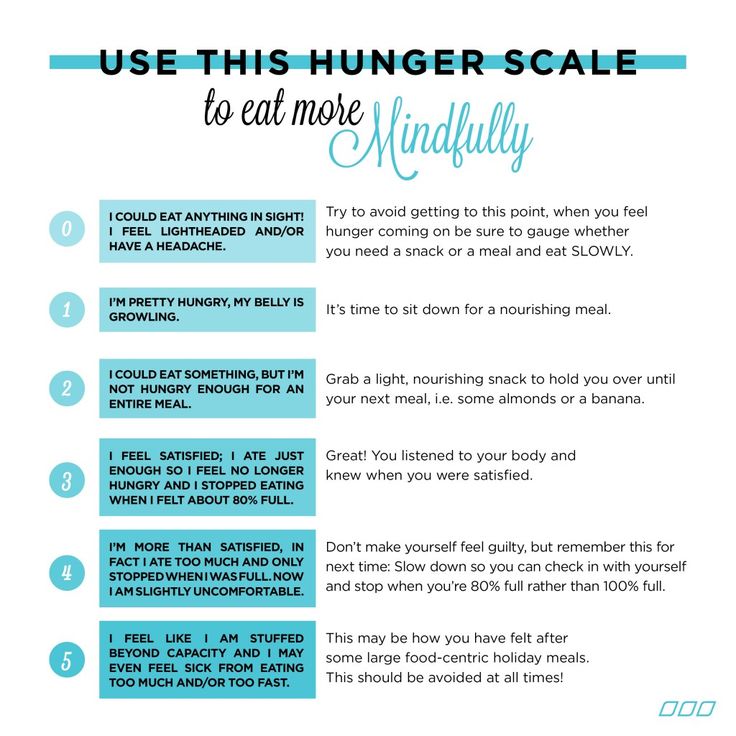

Under normal conditions, your brain helps your body recognize when you’re hungry or full.

However, eating too quickly or while you’re distracted makes it more difficult for your brain to notice these signals.

One way to solve this problem is to eliminate distractions and focus on the foods in front of you — a key aspect of mindful eating.

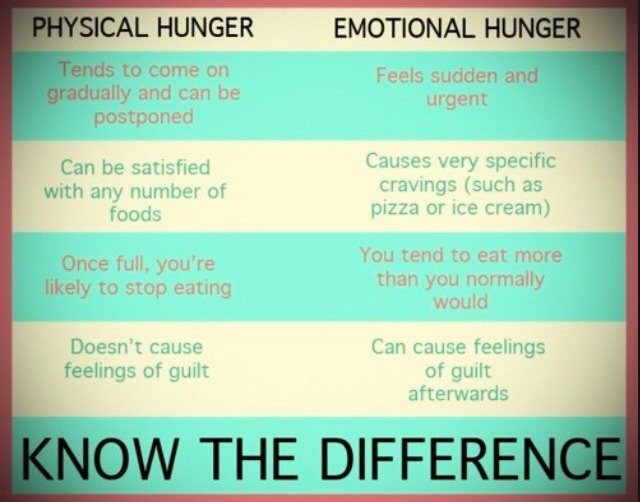

As opposed to letting external cues like advertisements or the time of day dictate when you eat, mindful eating is a way of tapping into your internal hunger and satiety cues, such as your thoughts and physical feelings (56).

Research shows that mindfulness during meals may weaken mood-related cravings and be especially helpful for people susceptible to emotional, impulsive, and reward-driven eating — all of which influence hunger and appetite (57, 58, 59, 60).

Nevertheless, it appears that mindful eating works best for limiting food cravings and increasing your awareness around food when it’s paired with a healthy diet, regular physical activity, and other behavior-focused therapies (61).

SUMMARYEating mindfully has been shown to decrease hunger and increase feelings of fullness. It may also reduce calorie intake and help cut down on emotional eating.

When your appetite or hunger levels are high, it can be especially easy to eat more than you planned. Slowing the pace at which you eat might be one way to curb the tendency to overeat (62, 63).

One study found that people who ate faster took bigger bites and ate more calories overall (64).

Another study found that foods eaten slowly were more satiating than those eaten quickly (65).

Interestingly, some newer research even suggests that your eating rate can affect your endocrine system, including blood levels of hormones that interact with your digestive system and hunger and satiety cues, such as insulin and pancreatic polypeptide (66).

SUMMARYEating slowly could leave you feeling more satisfied at the end of a meal and reduce your overall calorie intake during a meal.

You might have heard that eating from a smaller plate or using a certain size utensil can help you eat less.

Reducing the size of your dinnerware might also help you unconsciously reduce your meal portions and consume less food without feeling deprived. When you have more on a larger plate, you’re likely to eat more without realizing it (67, 68).

Some studies have found that eating with a smaller spoon or fork might not affect your appetite directly, but it could help you eat less by slowing your eating rate and causing you to take smaller bites (69, 70).

Yet, other studies have found conflicting results.

Researchers are beginning to understand that how the size of your dinnerware affects your hunger levels is influenced by a number of personal factors, including your culture, upbringing, and learned behaviors (71, 72).

The benefits of eating on a smaller plate may have been overstated in the past, but that doesn’t mean this technique isn’t worth trying (73, 74, 75, 76).

Experiment with different plate and utensil sizes to see for yourself whether they have any effect on your hunger and appetite levels or how much you eat overall.

SUMMARYEating from smaller plates may help you unconsciously eat less without increasing your feelings of hunger, though the results of this technique can vary greatly from person to person.

Exercise is thought to reduce the activation of brain regions linked to food cravings, which can result in a lower motivation to eat high calorie foods and a higher motivation to eat low calorie foods (77, 78).

It also reduces hunger hormone levels while increasing feelings of fullness (79, 80, 81, 82).

Some research shows that aerobic and resistance exercise are equally effective at influencing hormone levels and meal size after exercise, though it also suggests that higher intensity exercise has greater subsequent effects on appetite (77, 83, 84).

Overall, exercise appears to have a relatively positive effect on appetite for most people, but it’s important to note that studies have noticed a wide variability in the way individuals and their appetite respond to exercise (85).

In other words, there’s no guarantee the results will be the same for everyone. However, exercise has many benefits, so it’s a great idea to incorporate movement you enjoy into your day.

SUMMARYBoth aerobic and resistance exercise can help increase fullness hormones and lead to reduced hunger and calorie intake. Higher intensity activities might have the greatest effects.

Getting enough quality sleep might also help reduce hunger and protect against weight gain (86, 87).

Studies show that too little sleep can increase subjective feels of hunger, appetite, and food cravings (88, 89).

Sleep deprivation can also cause an elevation in ghrelin — a hunger hormone that increases food intake and is a sign that the body is hungry, as well as the appetite-regulating hormone leptin (90, 91).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), most adults need 7–9 hours of sleep, while 8–12 hours are recommended for children and teens (92).

SUMMARYGetting at least 7 hours of sleep per night is likely to reduce your hunger levels throughout the day.

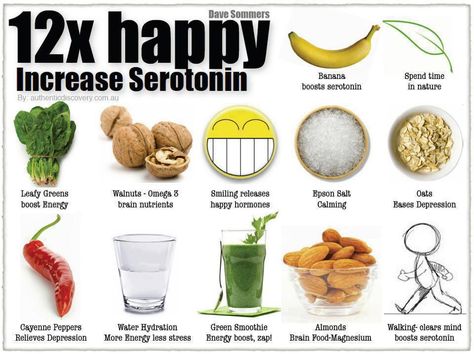

10. Manage your stress level

Excess stress is known to raise levels of the hormone cortisol.

Although its effects can vary from person to person, high cortisol levels are generally thought to increase food cravings and the drive to eat, and they have even been linked to weight gain (93, 94, 95, 96).

Stress may also decrease levels of peptide YY (PYY) — a fullness hormone (97).

On the other hand, some people react differently to stress.

One study found that acute bouts of stress actually decreased appetite (98).

Whether you’ve noticed that you tend to feel hungrier when you’re under stress or often find yourself stress eating in tense situations, consider some of these techniques to alleviate your stress (99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104):

- eat a healthy diet rich in stress-relieving foods

- exercise regularly

- sip green tea

- consider a supplement like ashwagandha

- try yoga or stretching

- limit your caffeine intake

SUMMARYReducing your stress levels may help decrease cravings, increase fullness, and even protect against depression and obesity.

Ginger has been linked to many health benefits due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties from the bioactive compounds it contains (105, 106, 107, 108).

When it comes to appetite, ginger actually has a reputation for increasing appetite in cancer patients by helping to ease the stomach and reduce nausea (109, 110, 111).

However, recent research adds another benefit to the list — it may help reduce hunger (112).

One animal study fed rats an herbal mix that contained ginger along with peppermint, horse gram, and whey protein. The mixture was found to help regulate appetite and induce satiety, though the results can’t be attributed to the ginger alone (113).

Still, more studies in humans are needed before strong conclusions about ginger and hunger can be reached (114).

SUMMARYIn addition to adding flavor and settling your stomach, ginger may help decrease feelings of hunger. Yet, more research is needed to confirm this effect.

12. Opt for filling snacks

Snacking is a matter of personal choice. Some people like to include snacks as part of their daily meal routine, whereas others don’t.

If you’re having trouble regulating your hunger and appetite levels throughout the day, some research suggests that eating snacks could help (3).

To promote feelings of fullness and satiety, choose snacks that are high in (3):

- protein

- fiber

- healthy fats

- complex carbs

For instance, a high protein yogurt decreases hunger more effectively than high fat crackers or a high fat chocolate snack (68).

In fact, eating a serving of high protein yogurt in the afternoon not only helps keep you full but also might help you eat fewer calories later in the day (115, 116).

SUMMARYEating a protein or fiber-rich snack will likely decrease hunger and may prevent you from overeating at your next meal.

13. Don’t deprive yourself

The relationship between appetite, hunger, and cravings is complex and includes many biological pathways.

Researchers are still working to understand exactly what happens when you restrict certain foods, and whether doing so is an effective approach to lessen cravings for those foods (117, 118).

Some people tend to experience cravings more intensely and are therefore more susceptible to them than others (119).

For most people, it’s not necessary to completely cut your favorite foods out of your diet. You can and should eat your favorite foods, after all.

If you have a craving for a certain specific food, enjoy that food in moderation to see whether it relieves the craving and lowers your appetite again.

SUMMARYEnjoying the foods you crave in moderation might be more effective at reducing hunger and cravings than depriving yourself of them completely.

The bottom line

Hunger and appetite are normal bodily functions.

Typically, they’re simply a sign that your body needs energy and it’s time to eat.

The tips mentioned here are just a few simple ways to reduce your appetite and hunger during times when it feels like those sensations are higher than normal.

If you’ve tried these things but still find yourself feeling hungry more than usual, consider talking with a healthcare professional about additional support for regulating your appetite.

Just one thing

Try this today: Did you know that emotions like boredom can sometimes be confused with hunger? This article on boredom eating can help you discern between true hunger and emotional hunger.

How to stop yourself from feeling hungry

Whether it’s on the morning commute, when you’re sat in a meeting or you’re in the middle of nowhere, pangs of hunger always tend to come at completely the wrong time. The urge to snack between meals because you’re feeling hungry is an all-too-common occurrence for most people - but what can be done to reduce the want to devour everything in sight?

Follow these top tips and you’ll have no problem keeping those pangs of hunger well and truly at bay.

Keep hydrated

One of the common misconceptions with hunger is that you’re actually mistaking it for being thirsty. On average, we should have two litres of water a day to ensure we are fully hydrated. But not having enough liquids in your body can leave you with the feeling of hunger. Having a water bottle on you at all times will help you get all the water you need into your diet. So next time you’re feeling a bit peckish, have a glass of water instead of snacking. Here are some tips on how to identify the symptoms of dehydration and prevent it.

Having a water bottle on you at all times will help you get all the water you need into your diet. So next time you’re feeling a bit peckish, have a glass of water instead of snacking. Here are some tips on how to identify the symptoms of dehydration and prevent it.

Make sure you have breakfast

In the morning, you need to get the right fuel down you to set you up for the day and keep your appetite at bay until lunchtime. Without breakfast, your body will feel as if it is being starved. You’ll experience tiredness, a lack of concentration and, of course, hunger pains in your stomach. Whether it’s a bowl of cereal or a fresh omelette, having some form of breakfast once you’ve woken up is key to staving off hunger pangs. Click here for 3 amazing vegan, delicious and healthy breakfast recipes.

Get your protein

Acting as an appetite suppressor, eating more protein is an effective way of staving off any hunger pangs. Not only does protein help give you a boost in energy through the day, they’ll also help increase your body fat metabolism by 32 per cent. From seafood to beans, try having around 50g of protein every four hours to truly keep you going and fight off the urge to snack on sugars and sweets.

From seafood to beans, try having around 50g of protein every four hours to truly keep you going and fight off the urge to snack on sugars and sweets.

Stay away from sugar

If you’re feeling hungry and you eat a sugary snack, you aren’t actually solving the issue. Sugars cause a disruption in the communication between your brain and your stomach as to when you’re full - in short, sugars only mask the problem, they don’t actually fix it. Don’t have sugars on their own - instead, ensure they are part of a mixed meal to help control your hunger. Find out what happens to your body when you ditch sugar.

Boost your fibre intake

Foods that are packed with fibre will take longer to digest than other food groups, so getting plenty into your diet will leave you feeling fuller for longer. Apples, carrots and spinach are three great examples of fresh produce to eat, but the likes of red kidney beans, chia seeds and pumpkin are fibre alternatives. Plus, eating fibre-rich food will help with your bowel health and reduce the risk of you feeling constipated.

Slow down!

According to research, it takes approximately 20 minutes for food to reach your stomach and start to make you feel full. But the study highlights that the majority of people eat their meal in five minutes and complain about still being hungry. When eating, try putting your fork down between mouthfuls to elongate the time you spend eating to 20 minutes, then you won’t feel the need to snack as soon as you’ve finished.

If you must give in to the cravings, here are 5 cheat meals you should always have on hand.

7 ways to cope with hunger during fasting and dieting

Impressions

© depositphoto.com/zentock

Author Alisa Kurmanaeva

April 19, 2016

In the spring, many go on a diet, and someone fasts. In any of these cases, people cut back on their diet and feel hungry. RBC Style found out from expert nutritionists how to avoid this unpleasant sensation.

Method #1 Eat right

“If the body receives food regularly and at approximately the same time, then it will not put aside anything in case it is fed at random,” explains Marina Alyamkina, dietitian at the TerraSport Copernicus fitness center. “5-6 meals a day is a prerequisite for proper nutrition.” According to her, breakfast should be 40% of the daily diet, lunch - 30% and dinner - 20%. The rest is for snacks. “In order for the fat cells of the body to give off energy, and not store calories in reserve, you need to eat every 2.5-3 hours,” says Anna Kozyreva, wellness coach, founder of the Ideal Day nutrition delivery project. “Only such a diet allows you to avoid surges in insulin, which regulates the energy metabolism of fat cells.”

Advertising on RBC www.adv.rbc.ru

Method No. 2. Do not replace a full meal with vegetables and fruits

Many fasting or dieters try to relieve hunger by eating apples, celery, vegetable salads, pears, carrots and other foods containing crude fiber. However, these vegetables and fruits should never replace a full meal. “They do not “clog” hunger, but, on the contrary, prepare our body for the main meal, activating the esophagus and the production of digestive enzymes. It is useful to eat them 45-60 minutes before a full lunch or dinner, - Marina Alyamkina explains.

However, these vegetables and fruits should never replace a full meal. “They do not “clog” hunger, but, on the contrary, prepare our body for the main meal, activating the esophagus and the production of digestive enzymes. It is useful to eat them 45-60 minutes before a full lunch or dinner, - Marina Alyamkina explains.

Method #3. Avoid drinks that contain sugar.

Soda, tea or coffee with sugar, fruit juices, and berry juices are all perceived by the brain as fast carbohydrates. Due to the entry of glucose into the blood, a person experiences a short-term feeling of satiety, and the body starts the process of producing insulin. “Free insulin causes a feeling of hunger that occurs very quickly after the last meal,” says Marina Alyamkina.

depositphoto.com/ victoreus

Method number 4. Do not give up coffee, but drink it with water this drink does not wake up. In fact, coffee suppresses the feeling of hunger, but at the same time removes fluid from the body. “Therefore, one cup of coffee should be balanced with one glass of pure water,” says Anna Kozyreva.

“Therefore, one cup of coffee should be balanced with one glass of pure water,” says Anna Kozyreva.

Method No. 5. Don't drink water with meals

All nutritionists say that you should drink as much water as possible because people often confuse feeling hungry and feeling thirsty. The daily norm is 1.5-2 liters per day. However, you also need to drink water properly. “Drink 15-20 minutes before meals and 20-30 minutes after. But you should not drink while eating - the liquid dilutes the gastric juice and the food is poorly digested, which leads to bloating, ”says Marina Alyamkina.

depositphoto.com/CITAlliance

Method #6 Eat 2 hours before bed, but no later than 21:00

suitable for modern man with his frantic pace of life. The last meal should be 1.5-2 hours before bedtime, but preferably no later than 21:00. If you are very hungry before going to bed, it is recommended to drink low-fat yogurt or yogurt with soy milk. “If we eat heavy protein or carbohydrate foods late at night, then the body will not absorb it, digest it somehow and dispose of already toxic residues in “problem” places. That's why "owls" almost never lose weight. Poor quality sleep or its lack is one of the first causes of weight gain and food breakdowns, ”explains Anna Kozyreva.

“If we eat heavy protein or carbohydrate foods late at night, then the body will not absorb it, digest it somehow and dispose of already toxic residues in “problem” places. That's why "owls" almost never lose weight. Poor quality sleep or its lack is one of the first causes of weight gain and food breakdowns, ”explains Anna Kozyreva.

Method #7. Choose the right dishes

The size and color of the plate also matter. “To control your appetite, choose dishes in neutral colors: white, blue, blue. But yellow, red and even black dishes only increase the feeling of hunger, says Anna Kozyreva. “Choose dessert plates over canteen plates so you can fill up faster and cut down on food without stress, even if you eat multiple times.”

how the brain makes us eat

Michael Graziano, neuroscientist, professor at Princeton University and author of The Science of Consciousness. The Modern Theory of Subjective Experience, believes that the problem of gaining excess weight and the desire to "eat something else" does not hide in an empty stomach and is not as strongly associated with blood sugar levels as we used to think.

It is in our head, in our mind, and it is there that we must look for a way out of the problem of overeating. We publish an abridged translation and adaptation of the scientist's article in the journal Aeon , in which he analyzes the phenomenon of "hungry mood".

It is in our head, in our mind, and it is there that we must look for a way out of the problem of overeating. We publish an abridged translation and adaptation of the scientist's article in the journal Aeon , in which he analyzes the phenomenon of "hungry mood". Once I decided to try my hand at solving the great problem of our time - how to lose weight without effort - and conducted an experiment on myself. Eight months later, I was 22 kilos lighter, so it seemed to work, but my approach to the problem was different from what I was used to. I am a psychologist after all, not a doctor, so from the very beginning I suspected that weight management was a matter of psychology, not physiology. If weight depended on the number of calories consumed and expended, we would all walk at the weight that we chose for ourselves. We all know the “just eat less” principle, and it seems that following it, losing weight should be no more difficult than choosing the color of a shirt. And yet, for some reason, it's not. […]

[…]

Hunger is one of the motivated states of mind, and psychologists have been studying these states for at least a century. We all feel hungry before dinner and full after a banquet, but these moments are just the tip of the iceberg. Hunger is a process that is always with us, it runs in the background and only occasionally awakens in consciousness. Hunger is more like a mood. When it slowly builds or recedes, even when it is out of consciousness, it changes and influences our decisions, distorts our priorities and emotional investment in long-term goals. It even changes our sensory perception, and often quite dramatically.

You sit down to dinner and say: “Why is this hamburger so tiny? Why did they have to be made so small? I need to eat three to be full" - and this is nothing but a "hungry mood" that makes the food on your plate smaller. After you have eaten, the exact same hamburger will look huge. And it's not just about food - your own body is also distorted. When your “hungry mood” rises, you feel a little leaner, you know the diet is working, and you can allow a little self-indulgence. As soon as the feeling of satiety sets in, you feel like a whale.

When your “hungry mood” rises, you feel a little leaner, you know the diet is working, and you can allow a little self-indulgence. As soon as the feeling of satiety sets in, you feel like a whale.

Moreover, even memory can be distorted. Let's say you keep a journal of everything you eat. Is he trustworthy? It's entirely possible that not only have you grossly underestimated the size of your meals, but you've almost certainly forgotten to write them down. Depending on the size of your hunger, you can eat three pieces of bread, and after dinner, it is quite sincere to remember only one. It's no wonder that most of the calories people consume come from snacking between meals, but when you ask people about it, they deny the impact of snacking. And they are surprised to find out how much they actually eat during them.

The "hungry mood" is difficult to control because it operates outside of consciousness. Perhaps that's why obesity is such an intractable problem.

"Hungry mood" is controlled by the brainstem, and the part most responsible for regulating hunger and other basic motivated states is called the hypothalamus and is located in the lower part of your brain. There are sensors in the hypothalamus that literally taste blood. They measure fat, protein, and glucose levels, as well as blood pressure and temperature. The hypothalamus collects this data and combines it with sensory signals that filter through other brain systems - about intestinal fullness, sensations, taste and smell of food, type of food, even about the time of day and other related circumstances.

Given all this data, neural circuits are gradually learning our dietary habits. This is why we get hungry at certain times of the day - not because of an empty stomach, but because of a complex neural processor that anticipates the need for additional nutrition at that time. If you skip a meal, you will feel acutely hungry at first, but then you will feel less hungry again as your usual meal time passes. That's why we get full at the end of the meal, again, not because of satiety. And if this is your only signal, then you are overeating a lot. Paradoxical as it may sound, there is a healthy gap between feeling full and being physically full.

That's why we get full at the end of the meal, again, not because of satiety. And if this is your only signal, then you are overeating a lot. Paradoxical as it may sound, there is a healthy gap between feeling full and being physically full.

Psychological satiety is a feeling of sufficiency resulting from much more complex calculations. In effect, the hypothalamus is saying, “You just ate a hamburger. From past experience with hamburgers, I know that after about two hours, the level of protein and fat in the blood will increase. Therefore, in anticipation of this, I will now turn off your hunger. ” . The system learns, anticipates and regulates, it works in the background, and we can consciously intervene in these processes, but usually not very effectively.

Let's say you decide to reduce your calorie intake and eat less throughout the day. Result? It's like grabbing a stick and poking a tiger with it. Your “hungry mood” will rise, and you will eat more and snack more over the next five days—perhaps only vaguely aware of it. People tend to judge how much they have eaten based on how full they feel after eating. But because this feeling of satiety is partly psychological, when your "hungry mood" is up, you may eat more than usual, but feel less full and mistakenly think you've cut back on food. You may feel like you are making progress. After all, you are constantly vigilant about your nutrition. Of course, you make mistakes from time to time, but you return to the right path again and again. You feel good until you step on the scale and notice that your weight is not responding. One fine day, it can decrease, and the next two days it can jump sharply. Dancing beneath the surface of consciousness, the "hungry mood" distorts your perceptions and choices.

People tend to judge how much they have eaten based on how full they feel after eating. But because this feeling of satiety is partly psychological, when your "hungry mood" is up, you may eat more than usual, but feel less full and mistakenly think you've cut back on food. You may feel like you are making progress. After all, you are constantly vigilant about your nutrition. Of course, you make mistakes from time to time, but you return to the right path again and again. You feel good until you step on the scale and notice that your weight is not responding. One fine day, it can decrease, and the next two days it can jump sharply. Dancing beneath the surface of consciousness, the "hungry mood" distorts your perceptions and choices.

I don't deny physics. If you eat fewer calories, you will lose weight, but if you explicitly try to cut them down, you will most likely do the exact opposite. After all, if you burn calories in the gym, you will definitely lose weight, right? Yes, except that after a workout, for the rest of the day, you are so exhausted that you can actually burn fewer calories than you would on a normal non-sporting day.

Moreover, by completing the workout, you get rid of guilt, your emotional tension goes away, and you reward yourself with a chocolate bun. Yes, you can try to be nice and refuse treats, but the exercises you just did increase your subtle hunger, and now you don't even notice how much you overeat. There is more food, but it seems that less.

Source: Amy Shamblen / unsplash.com

Let's say you've tried all the standard advice and all the existing diets. Some of them might even work for a short time before you lose your way and end up making even more money than before. After a while, you begin to doubt your willpower. After all, if the prevailing medical theory is correct, if weight is a matter of calorie control, then your problem is a weak character. Being overweight is your own fault, this is the message that is spreading from all sides through our culture.

However, cognitive control is much more subtle, complex, and limited in its scope than the usual notion of willpower.

Moreover, it is false and harmful to mental health. What does the concept of willpower do? Opposes long-term rewards to short-term rewards, and sooner or later you go astray. Every time you fall, you deal more damage than you can undo, and therefore fail to realize how much you are sabotaging your own efforts.

What does this lead to? To the fact that in the end you find yourself completely demoralized and depressed. You can do whatever you want, but for some reason you can't handle the weight loss and fall into a catastrophic spiral. After all, if you're going to be miserable anyway, you can indulge yourself. Food at least alleviates suffering. You fall into the habit of eating, start self-medicating with food, form an addiction and lose all motivation. You fall into the deepest part of the psychological swamp, where your chances of recovery are slim. […]

Most doctors, trainers and healthcare professionals think of weight in terms of chemistry - calories in vs. calories out.

Eat less, exercise more. Some schools of thought argue that all calories are equivalent, others that calories from fat are especially harmful, or that calories from carbohydrates should be especially avoided. But all these approaches focus on how calories are digested and distributed in the body, they ignore psychology. Most studies view the psychology of hunger as an inconvenience. […]

However, the obesity epidemic is not a problem of calories or willpower, it is a problem of poisoning the normal regulatory system

We have a complex and finely calibrated system that has evolved over millions of years to do its job well. It should run in the background without any conscious effort, but for more than two-thirds of us, it doesn't. What are we doing to ourselves that we violate the system of hunger and satiety?

Experimented on myself for about a year - and ate the same thing every day to establish a constant baseline of nutrition and hunger.

I measured weight, waist circumference and wrote down everything I could think of. Then I changed one thing in one meal and over the next few days watched for its tiny irritant effect. When the measurements returned to the original level, I tried a new replacement - after a while I was able to average many indicators and observe how the pattern manifested itself. Of course, I had no illusions about discovering something new, my experiments are not formal science, the sample consists of only one person. My task was only to find out which of all the conflicting advices resonated with my personal data. What should I believe?

As usual, the most instructive part of the experiment was the random observation. It doesn't matter if certain foods have increased or decreased my weight, I have noticed that certain activities increase or decrease my hunger levels. I knew when my "hungry mood" was going up, even if I didn't consciously feel it, because somehow I ended up at lunch earlier than usual.

[…] When my "hungry mood" went down, the list of priorities shifted and I immersed myself in my work - somehow I was delayed with lunch for an hour. […]

Three bad habits consistently increased my hunger: I call them the ultra-high-dead-carb diet, the low-fat craze, and the calorie-counting trap. We get up in the morning and eat a sandwich, porridge, or carbohydrate-packed cereal. Then we go to lunch. Let's say I don't have healthy habits and I eat fast food, lunch from McDonald's. We think of it as a fatty food, but in addition to fat, there is a bun in a burger, and ketchup is a sugar paste. […] Maybe you feel morally superior and prefer a "healthy" lunch - a sandwich, mainly consisting of bread.

An afternoon snack is a sweet coffee and a biscuit or muesli bar that also contains only carbohydrates. Maybe you eat a banana, but that doesn't make much of a difference. Dinner? Filled with potatoes, pasta, rice and bread. We think we eat seafood when we order sushi, but it's mostly rice.

Maybe you will choose a good healthy soup - it has noodles or potatoes. And every meal is accompanied by soda, juice, iced tea or other sweetened beverage. Then dessert. Then a snack before bed. In general, you understand.

You can't walk through a supermarket without being attacked from all sides by carbohydrates. And yes, some people talk about the superiority of complex carbohydrates over refined sugar, and they are right. But even if you cut out refined sugar, the amount of carbs is still amazing. A diet high in deadly carbohydrates has warped our sense of normalcy.

People who prefer a low carbohydrate diet may be right for the wrong reasons. […] According to this nutritional theory, if you cut out enough carbohydrates, your body will switch from using glucose to using ketones as the main energy-carrying molecule in the blood. Using ketones, the body will begin to consume its own fat reserves. What's more, by lowering your blood sugar, you lower your levels of insulin, the main hormone that promotes fat storage in the body.

Less carbs means less fat. […]

Theory and experiments may be correct, but they miss the most important point - they emphasize how calories are distributed in the body, instead of emphasizing the motivated state of hunger. It would be encouraging to see more research on how different diets affect hunger regulation. It is now well known that a high-carbohydrate diet increases hunger, and a low-carbohydrate diet eliminates this stimulus. Taken together, these data suggest that a low-carbohydrate diet does not help you lose weight because of its effect on energy use—it makes you lose weight because you eat less. Whereas a diet high in deadly carbohydrates fires up the hunger mechanism and your eating goes out of control. […]

Source: Amy Shamblen / unsplash.com

The low-fat craze works the same way. […] Don't eat butter. Don't eat eggs. Don't drink whole milk. Remove the skin from the chicken. […] I don't think the medical evidence is completely clear yet, but cutting out fat seems to have led to disaster.

As numerous studies have shown, fat reduces the feeling of hunger - remove it, and the "hungry mood" will increase, but the effect will be gradual. Remember, your hypothalamus takes in complex data and learns associations over time. Train him for a few months on a fat-free diet and it will increase your hunger.

But the most insidious attack on the hunger mechanism may be chronic dieting, the calorie-counting trap. The more you try to control your automatic hunger control mechanism, the more you disrupt its dynamics. Skip breakfast, cut calories for lunch, eat a small dinner, keep track of your calories, and you're successfully poking a hungry tiger with a stick. All you achieve by doing this is falling into a vicious circle of willpower and failure. […]

At the end of all my introspection and meditation, it was time to test the theory. I tried a simple formula. Firstly, I chose a moderately low-carb diet - I cut my carbohydrate intake by about 90% and at the same time did not even come close to a low-carb diet.

[…] Secondly, I added a little more fat. […] Thirdly, I allowed myself to eat as much as I want at every meal. The last one was the most difficult: when you want to lose weight, it's hard to imagine eating more. I just had to believe in a strange psychological paradox: if I try to eat less, I end up eating more.

I could list my products, but the concept is actually more revealing than the details. My diet had nothing to do with standard health advice and how these foods chemically affect my body. I didn't think about my arteries, or about my liver, or about insulin. This approach was designed to talk to my unconscious hunger control mechanism to encourage it to eat less. And it worked: with a slow weight loss of about a kilogram per week, I gradually got rid of the accumulation of twenty years - 22 extra pounds, which were gone in a few months.

The beauty of the method was that it was effortless (by effort I mean this questionable concept of willpower). […] When hunger mounts, the personal struggle becomes heartbreaking… and the strangest thing is that this struggle is alluring.