How does autism present in girls

Why Do Many Autistic Girls Go Undiagnosed?

Many more boys than girls are diagnosed on the autism spectrum: more than four boys for every autistic girl, according to the latest numbers from the Centers for Disease Control. Researchers point to genetic differences. But clinicians and researchers have also come to realize that many “higher functioning” autistic girls are simply missed. They’ve been termed the “lost girls” or “hiding in plain sight” because they’re overlooked or diagnosed late. They don’t fit the stereotypes or their symptoms are misinterpreted as something else. And they may be better at hiding the signs, at least when they’re young.

Even when girls’ presentation is clearer, they can be overlooked. Take Melissa’s two children. Both have an autism diagnosis. But while daughter Lisa’s symptoms were much more obvious than son Justin’s, the girl’s were waved off for three years by a variety of clinicians.

“On paper,” Melissa says, “she seemed to check all the boxes. ” Lisa had a significant language delay — she didn’t speak in sentences until she was 4 — did no pretend play, and had several meltdowns each day. There were also other signs, like lining up her stuffed animals, spinning in circles, and constantly seeking sensory input. She was also unable to handle any change in routine.

Though Lisa’s challenges qualified her for Early Intervention at 18 months, it wasn’t until she was 6 that a developmental neurologist would diagnose her with autism.

Melissa’s son was also diagnosed at 6 — but by the first clinician who saw him, despite the fact that his symptoms were far less obvious.

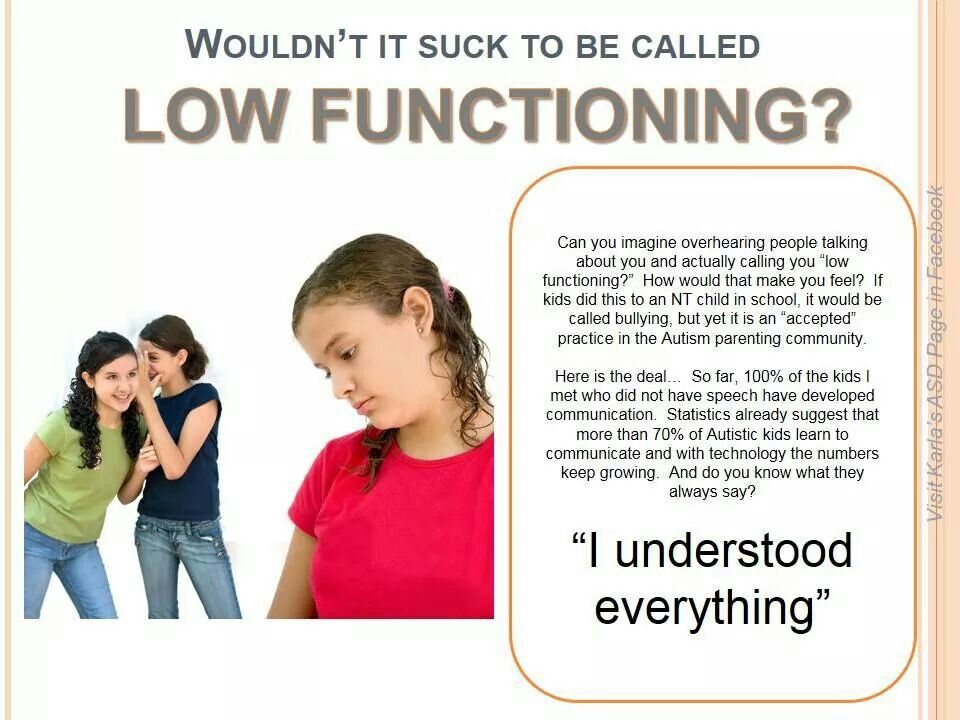

“The developmental pediatrician who saw Lisa didn’t believe autism was common in girls. He came up with excuses for her behavior and reasons why she couldn’t be on the spectrum,” Melissa says. “At one point, we were even told that my daughter just had low self-esteem and that’s why she didn’t speak. And, of course, that her issues were just a parenting problem. We were never told those things about our son.”

We were never told those things about our son.”

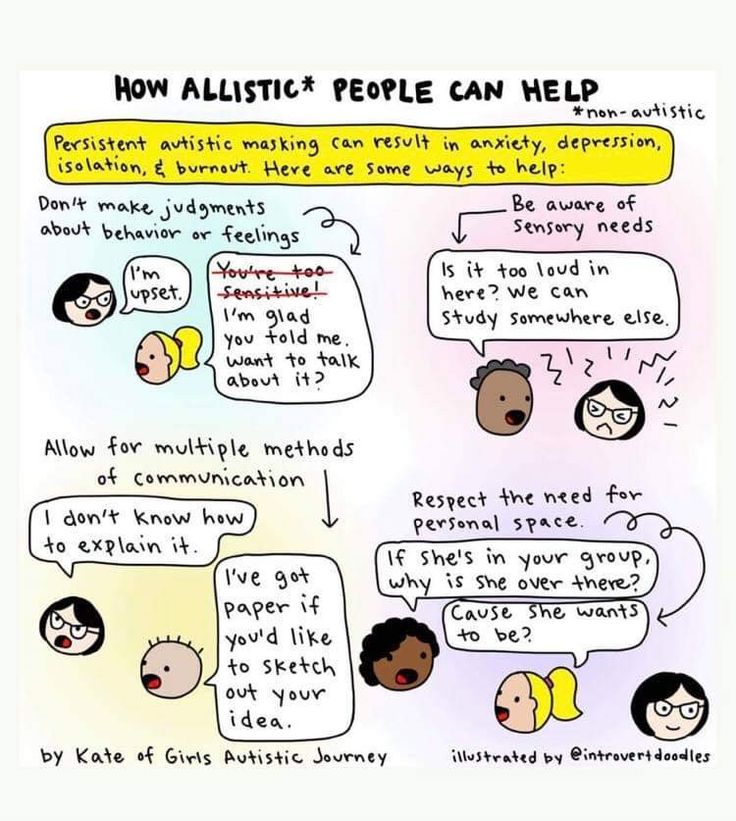

Autism is a developmental disorder that is marked by two unusual kinds of behaviors: deficits in communication and social skills, and restricted or repetitive behaviors. Children with autism also often have sensory processing issues. But here’s the hitch, according to Susan F. Epstein, PhD, a clinical neuropsychologist. “The model that we have for a classic autism diagnosis has really turned out to be a male model. That’s not to say that girls don’t ever fit it, but girls tend to have a quieter presentation, with not necessarily as much of the repetitive and restricted behavior, or it shows up in a different way.”

Stereotypes may get in the way of recognition. “So where the boys are looking at train schedules, girls might have excessive interest in horses or unicorns, which is not unexpected for girls,” Dr. Epstein notes. “But the level of the interest might be missed and the level of oddity can be a little more damped down. It’s not quite as obvious to an untrained eye.” She adds that as the spectrum has grown, it’s gotten harder to diagnose less-affected boys as well.

It’s not quite as obvious to an untrained eye.” She adds that as the spectrum has grown, it’s gotten harder to diagnose less-affected boys as well.

In fact, according to a 2005 study at Stanford University, autistic girls exhibit less repetitive and restricted behavior than boys do. The study also found brain differences between autistic boys and girls help explain this discrepancy.

Wendy Nash, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, adds that girls are more likely to control their behavior in public, so teachers don’t catch differences. “A lot of autistic girls get ruled out because they may share a smile or may have a bit better eye contact or they’re more socially motivated. It can be a more subtle presentation,” Dr. Nash explains. If girls are socially interested but odd, which is the case with the majority of these girls, she adds, “I think people give them a pass.”

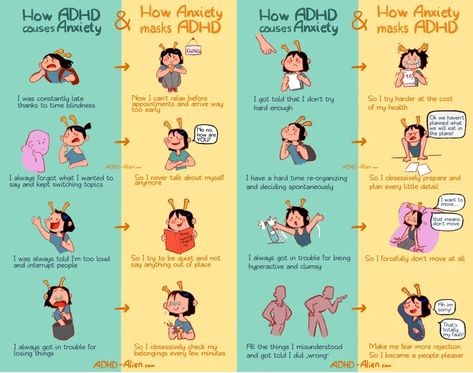

Another problem: misdiagnosesDr. Epstein says there’s another reason autistic girls are misdiagnosed, or diagnosed later than boys. Girls struggling with undiagnosed autism often develop depression, anxiety or poor self-esteem, and clinicians may not “really dig underneath to see the social dysfunction” caused by autism.

Girls struggling with undiagnosed autism often develop depression, anxiety or poor self-esteem, and clinicians may not “really dig underneath to see the social dysfunction” caused by autism.

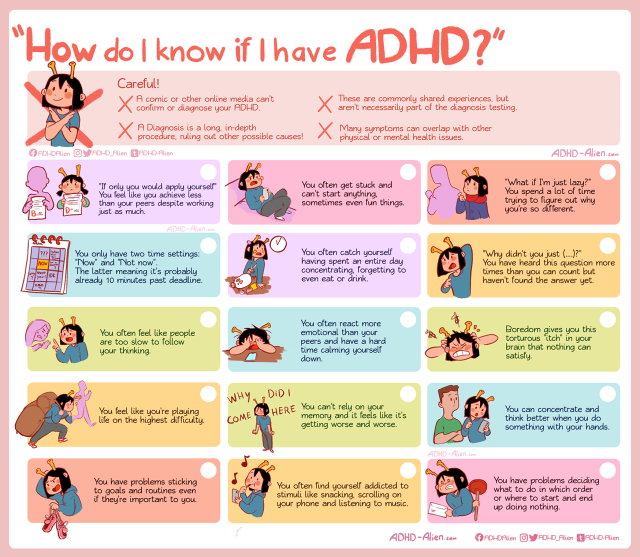

Dr. Nash adds that these girls can also be misdiagnosed with ADHD. “I see a lot of girls who are diagnosed with ADHD when they’re young who actually meet the criteria for autism,” she says. “There’s hyperactivity without as much social impairment or a different kind of social impairment, so the autism is missed.”

Autistic girls “pass”… at least for a whileAnother reason girls may not be diagnosed is because they’re able to “pass.”

“Girls tend to get by,” Dr. Epstein says. “They might not understand what’s going on but they’ll try to just go along and imitate what they see. And they may get away with it to third grade or fifth grade, but once they get to junior high and high school, it shows as a problem.”

This has been the case for Lisa, now 13. Melissa says of her daughter, “She is less mature than her typical peers, and girls are so intricate in how they behave socially. It’s very difficult for her to maintain friendships because of this and, let me tell you, 13-year-old girls are not very accepting of someone different.”

Melissa says of her daughter, “She is less mature than her typical peers, and girls are so intricate in how they behave socially. It’s very difficult for her to maintain friendships because of this and, let me tell you, 13-year-old girls are not very accepting of someone different.”

Dr. Epstein says undiagnosed autistic girls end up wondering “what’s wrong” with them, which can lead to depression, anxiety and loss of self-esteem. They work so hard to fit in that it wears them out. “That’s the thing about imitating,” she says. “You don’t necessarily ‘get’ it so you’re just trying to do what people do. If you’re just trying to mimic and you don’t really understand, it makes it pretty rough.”

Dr. Nash says less severe autism in girls is often first flagged because of these social issues, or the depression they generate. “In people we call mildly autistic, there are adolescent social problems or they’re seeming hyperfocused on a topic and not participating in school to their potential or abilities,” she says. “Depression can be more common among high-functioning kids on the spectrum. So they’ll come in for something like depression or poor school performance. Then it becomes more clear to me that they have a restricted interest and social communication issues.”

“Depression can be more common among high-functioning kids on the spectrum. So they’ll come in for something like depression or poor school performance. Then it becomes more clear to me that they have a restricted interest and social communication issues.”

Another cost of being overlooked is missing out on early support for skill-building. “We talk about early intervention,” Dr. Epstein says. “When the girls are identified late, they’ve missed out on a lot of social interventions that are much harder later. That’s the danger for anybody who gets a late diagnosis.”

Dr. Nash concurs, adding that they’ve missed opportunities to get the proper support in school as well as socially: “Academically, it’s harder for them to focus on topics that are not of interest. That’s true for people who have ADHD and even to a greater degree for kids who are on the autism spectrum.”

Safety risks for autistic girlsAutistic girls may be bullied simply because they’re “different. ” Also, Dr. Epstein says, because these girls miss social cues and want to be liked, their autism can leave them more naïve. This makes them easy prey for someone trying to take advantage of them, be it a bully or a sexual predator. “The girls may be wanting the interaction but not understanding what it’s about, what the cues are,” Dr. Epstein says. “It can be very easy for them to follow their hormones without an understanding of what the dangers are. And sometimes even if they have been taught, they need ongoing support to be able to maintain safety.”

” Also, Dr. Epstein says, because these girls miss social cues and want to be liked, their autism can leave them more naïve. This makes them easy prey for someone trying to take advantage of them, be it a bully or a sexual predator. “The girls may be wanting the interaction but not understanding what it’s about, what the cues are,” Dr. Epstein says. “It can be very easy for them to follow their hormones without an understanding of what the dangers are. And sometimes even if they have been taught, they need ongoing support to be able to maintain safety.”

Melissa says this has been true with Lisa. “I’ve had to think about female issues at a much earlier age than I expected,” she says. “We’ve already had an incident of her being inappropriately touched by a boy, for whom the excuse was made that because he’s also disabled, he ‘didn’t understand what he was doing was wrong.’”

One of her daughter’s greatest strengths is how accepting she is of others, Melissa adds. “She always finds the good in people, even when they are mean to her,” she says. “But because she is so accepting and kind, others can easily take advantage of her, or bully her, and she won’t say anything.”

“But because she is so accepting and kind, others can easily take advantage of her, or bully her, and she won’t say anything.”

Dr. Nash notes that there’s an area of study that’s rethinking how to help girls on the spectrum: “There’s expanding research on how boys and girls present differently and how our treatments may need to be specified a bit more for a girl’s presentation vs. a boy’s presentation.”

But first the girls need to be identified — and accepted. This will require more awareness and sensitivity on the part of parents, teachers and clinicians.

Video Resources for Kids

Teach your kids mental health skills with video resources from The California Healthy Minds, Thriving Kids Project.

Start Watching

Autism--It's Different in Girls - Scientific American

When Frances was an infant, she was late to babble, walk and talk. She was three before she would respond to her own name. Although there were hints that something was unusual about her development, the last thing her parents suspected was autism. “She was very social and a very happy, easy baby,” says Kevin Pelphrey, Frances's father.

“She was very social and a very happy, easy baby,” says Kevin Pelphrey, Frances's father.

Pelphrey is a leading autism researcher at Yale University's world-renowned Child Study Center. But even he did not recognize the condition in his daughter, who was finally diagnosed at about five years of age. Today Frances is a slender, lightly freckled 12-year-old with her dad's warm brown eyes. Like many girls her age, she is shy but also has strong opinions about what she does and does not want. At lunchtime, she and her little brother, Lowell, engage in some classic sibling squabbling—“Mom, he's kicking me!”

Lowell, seven, received an autism diagnosis much earlier, at 16 months. Their mom, Page, can recall how different the diagnostic process was for her two children. With Lowell, it was a snap. With Frances, she says, they went from doctor to doctor and were told to simply watch and wait—or that there were various physical reasons for her delays, such as not being able to see well because of an eye condition called strabismus that would require surgical treatment at 20 months. “We got a lot of different random little diagnoses,” she recalls. “They kept saying, ‘Oh, you have a girl. It's not autism.’”

“We got a lot of different random little diagnoses,” she recalls. “They kept saying, ‘Oh, you have a girl. It's not autism.’”

In fact, the criteria for diagnosing autism spectrum disorder (ASD)—a developmental condition that is marked by social and communication difficulties and repetitive, inflexible patterns of behavior—are based on data derived almost entirely from studies of boys. These criteria, Pelphrey and other researchers believe, may be missing many girls and adult women because their symptoms look different. Historically the disorder, now estimated to affect one out of every 68 children in the U.S., was thought to be at least four times more common in boys than in girls. Experts also believed that girls with autism were, on average, more seriously affected—with more severe symptoms, such as intellectual disability. Newer research suggests that both these ideas may be wrong.

Many girls may, like Frances, be diagnosed late because autism can have different symptoms in females. Others may go undiagnosed or be given diagnoses such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and even, some researchers believe, anorexia. As scientists study how this disorder plays out in girls, they are confronting findings that could overturn their ideas not only about autism but also about sex and how it both biologically and socially affects many aspects of development. They are also beginning to find ways to meet the unique needs of girls and women on the spectrum.

Others may go undiagnosed or be given diagnoses such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and even, some researchers believe, anorexia. As scientists study how this disorder plays out in girls, they are confronting findings that could overturn their ideas not only about autism but also about sex and how it both biologically and socially affects many aspects of development. They are also beginning to find ways to meet the unique needs of girls and women on the spectrum.

It's Different for Girls

Scientists in recent years have investigated several explanations for autism's skewed gender ratio. In the process, they have uncovered social and personal factors that may help females mask or compensate for the symptoms of ASD better than males do, as well as biological factors that may prevent the condition from developing in the first place [see “The Protected Sex” below]. Research has also revealed bias in the way the disorder is diagnosed.

A 2012 study by cognitive neuroscientist Francesca Happ of King's College London and her colleagues compared the occurrence of autism traits and formal diagnoses in a sample of more than 15,000 twins. They found that if boys and girls had a similar level of such traits, the girls needed to have either more behavioral problems or significant intellectual disability, or both, to be diagnosed. This finding suggests that clinicians are missing many girls who are on the less disabling end of the autism spectrum, previously designated Asperger's syndrome.

In 2014 psychologist Thomas Frazier of the Cleveland Clinic and his colleagues assessed 2,418 autistic children, 304 of them girls. They, too, found that girls with the diagnosis were more likely to have low IQs and extreme behavior problems. The girls also had fewer (or perhaps less obvious) signs of “restricted interests”—intense fixations on a particular subject such as dinosaurs or Disney films. These interests are often a key diagnostic factor on the less severe end of the spectrum, but the examples used in diagnosis often involve stereotypically “male” interests, such as train timetables and numbers. In other words, Frazier had found further evidence that girls are being missed. And a 2013 study showed that, like Frances, girls typically receive their autism diagnoses later than boys do.

In other words, Frazier had found further evidence that girls are being missed. And a 2013 study showed that, like Frances, girls typically receive their autism diagnoses later than boys do.

Pelphrey is among a growing group of researchers who want to understand what biological sex and gender roles can teach us about autism—and vice versa. His interest in autism is both professional and personal. Of his three children, only his middle child is typical. Kenneth, Pelphrey jokes, has classic “middle-child syndrome” and complains that his siblings “get away with murder because they can blame it on their autism.”

Pelphrey is now leading a collaboration with researchers at Harvard University, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of Washington to conduct a major study of girls and women with autism, which will follow participants over the course of childhood through early adulthood. The researchers want “every bit of clinical information we can get because we do not know what we ought to be looking for,” Pelphrey says. Consequently, they are also asking participants and family members to suggest areas of investigation because they know firsthand what is most helpful and most problematic.

Consequently, they are also asking participants and family members to suggest areas of investigation because they know firsthand what is most helpful and most problematic.

Girls in the study will be compared with autistic boys, as well as typically developing children of both sexes, using brain scans, genetic testing and other measures. Such comparisons can help researchers tease out which developmental differences are attributable to autism, as opposed to sex, as well as whether autism itself affects sex differences in the brain and how social and biological factors interact in producing gender-typical behaviors.

Already Pelphrey is seeing fascinating differences in autistic girls in his preliminary research. “The most unusual thing we keep finding is that everything we thought we knew in terms of functional brain development is not true,” he says. “Everything we thought was true of autism seems to only be true for boys.” For example, many studies show that the brain of a boy with autism often processes social information such as eye movements and gestures using different brain regions than a typical boy's brain does. “That's been a great finding in autism,” Pelphrey says. But it does not hold up in girls, at least in his group's unpublished data gathered so far.

“That's been a great finding in autism,” Pelphrey says. But it does not hold up in girls, at least in his group's unpublished data gathered so far.

Pelphrey is discovering that girls with autism are indeed different from other girls in how their brain analyzes social information. But they are not like boys with autism. Each girl's brain instead looks like that of a typical boy of the same age, with reduced activity in regions normally associated with socializing. “They're still reduced relative to typically developing girls,” Pelphrey says, but the brain-activity measures they show would not be considered “autistic” in a boy. “Everything we're looking at, brain-wise, now seems to be following that pattern,” he adds. In short, the brain of a girl with autism may be more like the brain of a typical boy than that of a boy with autism.

A small study by Jane McGillivray and her colleagues at Deakin University in Australia, published in 2014, provides behavioral evidence to support this idea. McGillivray and her colleagues compared 25 autistic boys and 25 autistic girls with a similar number of typically developing children. On a measure of friendship quality and empathy, autistic girls scored as high as typically developing boys the same age—but lower than typically developing girls.

McGillivray and her colleagues compared 25 autistic boys and 25 autistic girls with a similar number of typically developing children. On a measure of friendship quality and empathy, autistic girls scored as high as typically developing boys the same age—but lower than typically developing girls.

Pelphrey is finding that autism also highlights normal developmental differences between girls and boys. Sex hormones, he says, “affect just about every structure you might be interested in and just about every process you might be interested in.” Although boys generally mature much later than girls do, the differences in brain development appear to be quite big—far larger than the differences in behavior.

Masking Autism

Jennifer O'Toole, an author and founder of the Asperkids Web site and company, was not diagnosed until after her husband, daughter and sons were found to be on the spectrum. On the outside, she looked pretty much the opposite of autistic. At Brown University, she was a cheerleader and sorority girl whose boyfriend was the president of his fraternity.

But inside, it was very different. Social life did not come at all naturally to her. She used her formidable intelligence to become an excellent mimic and actress, and the effort this took often exhausted her. From the time she started reading at three and throughout her childhood in gifted programs, O'Toole studied people the way others might study math. And then, she copied them—learning what most folks absorb naturally on the playground only through voracious novel reading and the aftermath of embarrassing gaffes.

O'Toole's story reflects the power of an individual to compensate for a developmental disability and hints at another reason females with autism can be easy to miss. Girls may have a greater ability to hide their symptoms. “If you were just judging on the basis of external behavior, you might not really notice that there's anything different about this person,” says University of Cambridge developmental psychopathologist Simon Baron-Cohen. “It relies much more on getting under the surface and listening to the experiences they're having rather than how they present themselves to the world. ”

”

O'Toole's obsessive focus on reading and finding rules and regularities in social life is far more characteristic of girls with autism than boys, clinical experience suggests. Autistic boys sometimes do not care whether they have friends or not. In fact, some diagnostic guidelines specify a disinterest in socializing. Yet autistic girls tend to show a much greater desire to connect.

In addition, girls and boys with autism play differently. Studies have found that autistic girls exhibit less repetitive behavior than the boys do, and as the 2014 findings from Frazier and his colleagues suggest, girls with autism frequently do not have the same kinds of interests as stereotypical autistic boys. Instead their pastimes and preferences are more similar to those of other girls.

Frances Pelphrey's obsession with Disney characters and American Girl dolls might seem typical, not autistic, for example. O'Toole remembers compulsively arranging her Barbie dolls. Furthermore, although autism is often marked by an absence of pretend play, research finds that this is less true for girls.

Here, too, they can camouflage their symptoms. O'Toole's behavior might have seemed like typical make-believe to her parents because she staged Barbie weddings just like other little girls. But rather than imagining she was the bride, O'Toole was actually setting up static visual scenes, not story lines.

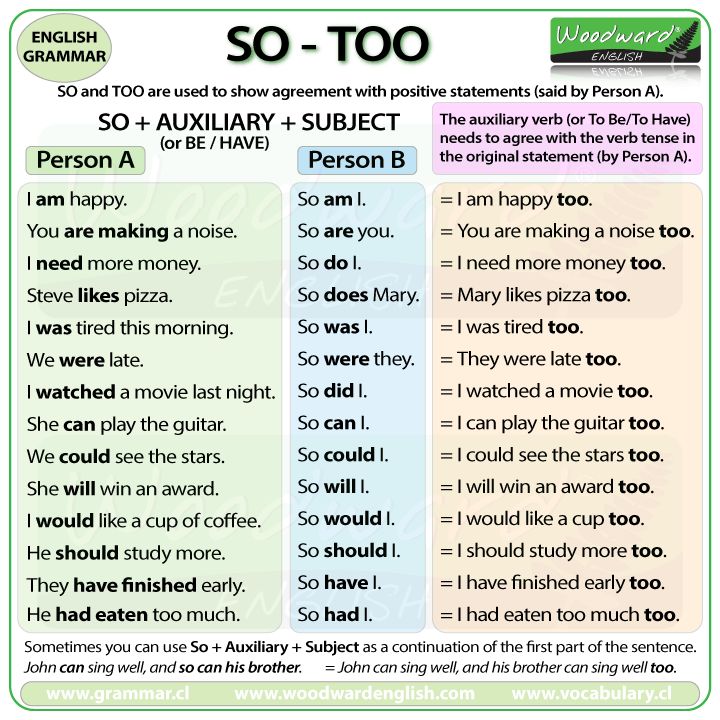

Also, unlike in boys, the difference between typical and autistic development in girls may lie less in the nature of their interests than in its level of intensity. These girls may refuse to talk about anything else or take expected conversational turns. “The words used to describe women on the spectrum come down to the word ‘too,’” O'Toole says. “Too much, too intense, too sensitive, too this, too that.”

She describes how both her sensory differences—she can be overwhelmed by crowds and is bothered by loud noise and certain textures—and her social awkwardness made her stand out. Her life was dominated by anxiety. Speaking broadly of people on the spectrum, O'Toole says, “There is really not a time when we're not feeling some level of anxiety, generally stemming from either sensory or social issues. ”

”

As she grew up, O'Toole channeled her autistic hyperfocus into another area to which culture frequently directs women: dieting and body image, with a big dollop of perfectionism. “I used to have a spreadsheet of how many calories, how many grams of this, that and the other thing [I could eat],” she says. The resulting anorexia became so severe that she had to be hospitalized when she was 25.

In the mid-2000s researchers led by psychiatrist Janet Treasure of King's College London began to explore the idea that anorexia might be one way that autism manifests itself in females, making them less likely to be identified as autistic. “There are striking similarities in the cognitive profiles,” says Kate Tchanturia, an eating disorder researcher and colleague of Treasure's at King's College London. Both people with autism and those with anorexia tend to be rigid, detail-oriented and distressed by change.

Furthermore, because many people with autism find certain tastes and food textures aversive, they often wind up with severely restricted diets. Some research hints at the connection between anorexia and autism: in 2013 Baron-Cohen and his colleagues gave a group of 1,675 teen girls—66 of whom had anorexia—assessments measuring the degree to which they had various autism traits. The research found that women with anorexia have higher levels of these traits than typical women do.

Some research hints at the connection between anorexia and autism: in 2013 Baron-Cohen and his colleagues gave a group of 1,675 teen girls—66 of whom had anorexia—assessments measuring the degree to which they had various autism traits. The research found that women with anorexia have higher levels of these traits than typical women do.

No one is suggesting that the majority of women with anorexia also have autism. A 2015 meta-analysis by Tchanturia and her colleagues puts the figure at about 23 percent—a rate of ASD far higher than that seen in the general population. What all of this suggests is that some of the “missing girls” on the spectrum may be getting eating disorder diagnoses instead.

Further, because autism and ADHD often occur together—and because people diagnosed with ADHD tend to have higher levels of autism traits than typical people do—girls who seem easily distracted or hyperactive may get this label, even when autism is more appropriate. Obsessive-compulsive behavior, rigidity and fear of change also occur in both people with autism and those with OCD, suggesting that autistic females might also be hidden in this group.

Double Standards

Even when young women are comparatively “easy” to diagnose, they still face many challenges in the course of development—particularly social ones. This was the case for Grainne. Her mother, Maggie Halliday, had grown up in a large Irish family and could see early on that her third child, Grainne, was different. “I knew from when she was a couple of months old that there was something not right,” Halliday says. “She didn't like to be held or cuddled. She could make herself a dead weight and just—you couldn't pick her up.”

Although Grainne's IQ tests are in the low normal range, the results do not capture either her abilities or her disabilities well. Today the teenager's intense interests are boy bands and musical theater. Despite being extremely shy, she blooms on stage and loves to sing. “The play she's in, when they deliver the script, within a week, she has everybody's part memorized and every song in the score memorized,” Halliday says.

Because of a genetic condition, Grainne is short: 47—and a half, she insists. And although she is laconic and does not tend to initiate conversation, she is also bubbly and smiles frequently, clearly interested in connecting. She weighs what she does say very carefully. For example, when asked whether she thinks autistic girls are more social than boys with autism, Grainne says, “Some might be,” not wanting to generalize.

And although she is laconic and does not tend to initiate conversation, she is also bubbly and smiles frequently, clearly interested in connecting. She weighs what she does say very carefully. For example, when asked whether she thinks autistic girls are more social than boys with autism, Grainne says, “Some might be,” not wanting to generalize.

Of course, adolescence is difficult for most kids, but it is especially challenging for autistic girls. Many can cope with the far simpler world of elementary school friendships, but they hit a wall with the “mean girls” of junior high and the subtleties of flirting and dating. Moreover, puberty involves unpredictable changes such as breast development, mood swings and periods—and there are few things that autistic people hate more than change that occurs without warning. “She would like to have a boyfriend—that's why she loves the boy bands,” says Halliday, adding that she thinks Grainne may not understand what such a relationship would really mean.

Unfortunately, the autistic tendency to be direct and take things literally can make affected girls and women easy prey for sexual exploitation. O'Toole herself was the victim of an abusive relationship, and she says the problem is “endemic” among women on the spectrum, particularly because so many are acutely aware of their social isolation. “When you feel you're too difficult to love, you'll love for crumbs,” she says.

In this way, autism may be more painful for women. Autistic people who do not seem interested in social life probably do not obsess about what they are missing—but those who want to connect and cannot are tormented by their loneliness. A study published in 2014 by Baron-Cohen and his colleagues found that 66 percent of adults with the milder form of ASD (so-called Asperger's) reported suicidal thoughts, a rate nearly 10 times higher than that seen in the general population. The proportion was 71 percent among women, who made up about one third of the sample.

Until very recently, few resources have been available to help autistic girls through these difficulties. Now researchers and clinicians are starting to fill these gaps. For example, Rene Jamison, an assistant clinical professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center, runs a program in Kansas City called Girls Night Out. Aimed at helping affected girls navigate adolescence, it focuses on specific issues such as hygiene and dress. Although this emphasis might seem trivial or a concession to gender stereotypes, in fact, failing to address such “superficial” concerns can cause serious life problems and restrict independence.

Even many highly intelligent girls on the spectrum have difficulties with washing their hair, wearing deodorant and dressing appropriately, Jamison says. Some of this behavior is linked to sensory issues; other aspects of the problem are related to difficulty following the appropriate sequence of behavior when doing something you think is unimportant. “When Grainne was in seventh grade, I had to tell her it was against the law not to wear a bra,” Halliday says of her daughter, who found bras uncomfortable. Grainne also did not want to wear deodorant—saying, almost certainly accurately, that the boys smelled worse.

Grainne also did not want to wear deodorant—saying, almost certainly accurately, that the boys smelled worse.

The Girls Night Out group does fun activities, ranging from having manicures to playing sports. Typical girls who get school credit for volunteering provide mentoring and talk about boys and other issues the girls might not want to discuss with adults. “One of the things that we really work on is getting them to try new things to figure out what they might like,” Jamison says.

In New York City, Felicity House, which its founders tout as the world's first community center for women on the spectrum, opened in 2015. Funded by the Simons Foundation, it occupies several floors of a spectacular Civil War–era mansion near Gramercy Park and offers classes and social events so autistic women can get to know and support one another. Five of the autistic women who helped to found Felicity House met a few weeks before it opened to talk about life on the spectrum. Only two had been diagnosed as children—one with Asperger's and another with what she said was “ADHD with autistic tendencies. ” Of the other three women, two had struggled with depression before their diagnosis as adults.

” Of the other three women, two had struggled with depression before their diagnosis as adults.

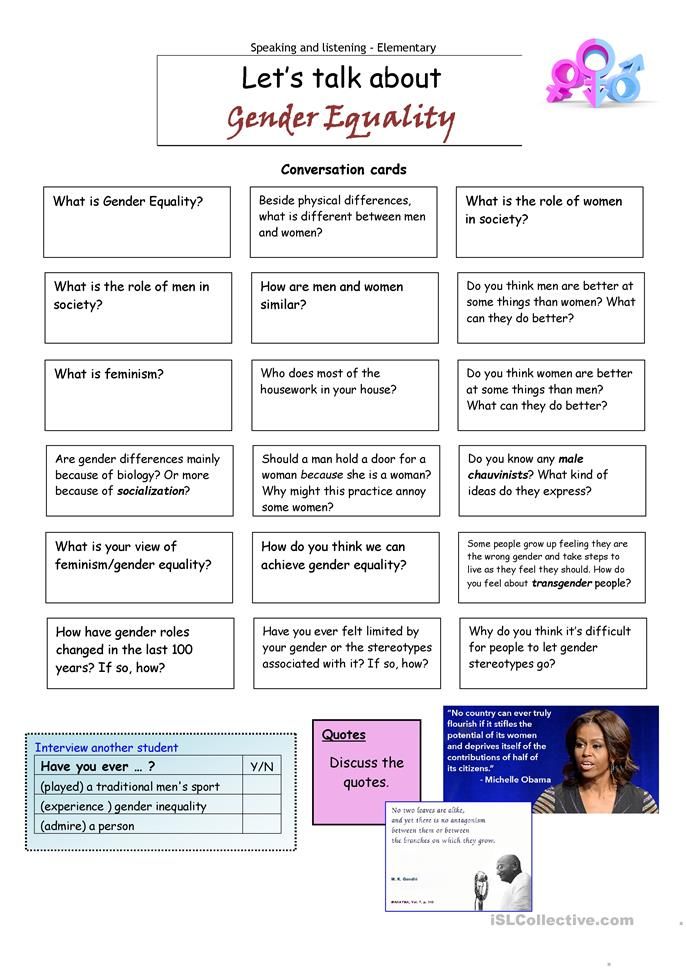

Emily Brooks, 26, is a writer studying for her master's in disability studies at City University of New York. She identifies as gender queer and believes gender norms cause many problems for people on the spectrum. She noted, to broad agreement, that boys are allowed far greater leeway to deviate from social expectations. “If a guy does something that is considered socially inappropriate … his friends may sometimes encourage some of those behaviors,” she said, adding that “teen girls will shut you down if you do anything that's different.”

Leironica Hawkins, an artist who has created a comic book about Asperger's, also has to contend with social cues about race. “It's not just because I'm a woman on the spectrum. I'm a black woman on the spectrum, and I have to deal with social cues that [other] people can afford to ignore,” she said. She added that she thought women “are probably punished more for not behaving the way we should. I've always heard women are socially aware to the needs of others, and that's not me, most of the time … I feel like I get pressured to be that way.”

I've always heard women are socially aware to the needs of others, and that's not me, most of the time … I feel like I get pressured to be that way.”

Because of these expectations, there is less tolerance for unusual behavior—and not just in high school. Many of the women report having difficulty keeping—but not getting—jobs, despite excellent qualifications. “You can see that in a faculty meeting even at the high-level academic departments,” Yale's Pelphrey says. “The guys still get away with much, much more.”

As awareness of autism grows, women and girls are already increasingly likely to be diagnosed; this generation clearly has significant advantages over those past. But much more research will need to be done to design better and more gender-appropriate diagnostic tools. Perhaps in the interim, the experiences of women with autism should teach us to be more tolerant of socially inept behavior in women—or less tolerant of it in men. Either way, it is clear that a greater understanding of autism in girls is needed to recognize this condition. And in the process it could illuminate new facets of typical behavior and the way that gender shapes the social world.

And in the process it could illuminate new facets of typical behavior and the way that gender shapes the social world.

The Protected Sex

Simon Baron-Cohen, a professor of developmental psychopathology and director of the University of Cambridge’s Autism Research Center, has helped develop several of the major theories that are guiding current thinking about autism. One of these hypotheses, which he is continuing to test, is the “extreme male brain” theory, which first appeared in the literature in 2002. The idea is that autism is caused by fetal exposure to higher than normal levels of male hormones, such as testosterone. This occurrence shapes a mind that is more focused on “systemizing” (understanding and categorizing objects and ideas) than “empathizing” (considering social interactions and other people’s perspectives).

In other words, autistic minds may be stronger in areas where male brains, on average, tend to have strengths—and weaker in areas where females, again, speaking broadly, are the superior sex. (When it comes to individuals, of course, these averages do not say anything about a particular man or woman’s ability or capacity—nor do the differences necessarily reflect immutable biology rather than culture.)

(When it comes to individuals, of course, these averages do not say anything about a particular man or woman’s ability or capacity—nor do the differences necessarily reflect immutable biology rather than culture.)

Numerous recent studies have supported Baron-Cohen’s idea. In 2010 he and his colleagues found that male fetuses exposed to higher levels of testosterone in amniotic fluid during pregnancy tend to grow up to have more autism traits. A 2013 study he co-authored, led by his Cambridge colleague MengChuan Lai, found that the brain-scan differences seen in children with autism occurred most often in regions that tend to vary by gender in typical children.

In 2015 Baron-Cohen and his colleagues published results of an analysis of a large group of amniotic fluid samples from Denmark that are linked to population registries of mental health. They found that in boys, having an autism diagnosis was linked with higher levels of fetal testosterone and various other hormones, but the first cohort tested had too few girls with autism, so they are analyzing later births to see if the same results will be found. Further evidence came from a large Swedish study, also published last year, that found a 59 percent increased risk of giving birth to a child with autism among women with polycystic ovary syndrome—an endocrine disorder involving elevated levels of male hormones.

Further evidence came from a large Swedish study, also published last year, that found a 59 percent increased risk of giving birth to a child with autism among women with polycystic ovary syndrome—an endocrine disorder involving elevated levels of male hormones.

Few scientists—including Baron-Cohen—think that the extreme male brain theory is the whole story. A second idea emerges when looking at the typical strengths of women. If having female hormones and a female-type brain structure increases the ability to read the emotions of others and makes social concerns more salient, it might take a greater number of genetic or environmental “hits” to alter this capacity to the level where autism would be diagnosed. This idea is known as the “female protective” hypothesis.

Along these lines, several studies have shown that in families with affected daughters, there are higher numbers of mutations known as copy-number variations than there are in families where only boys are affected. A 2014 study by geneticist Sbastien Jacquemont of the University of Lausanne in Switzerland and his colleagues found that there was a 300 percent increase in harmful copy-number variants in females with autism, compared with males.

A 2014 study by geneticist Sbastien Jacquemont of the University of Lausanne in Switzerland and his colleagues found that there was a 300 percent increase in harmful copy-number variants in females with autism, compared with males.

If either—or both—of these hypotheses is correct, then there will always be more boys than girls on the spectrum. “I imagine that once we’re very good at recognizing autism in females, there will still be a male bias,” Baron-Cohen says. “It just won’t be as marked as four to one. It might be more like two to one.” —M.S.

This article was originally published with the title "The Invisible Girls" in SA Mind 27, 2, 48-55 (March 2016)

doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0316-48

MORE TO EXPLORE

Thinking in Pictures: My Life with Autism. Expanded edition. Temple Grandin. Vintage, 2006.

Aspergirls: Empowering Females with Asperger Syndrome. Rudy Simone. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2010.

The Autistic Brain: Thinking across the Spectrum. Temple Grandin and Richard Panek. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013.

Temple Grandin and Richard Panek. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013.

Sisterhood of the Spectrum: An Asperger Chick's Guide to Life. Jennifer Cook O'Toole. Jessica Kingsley Pub, 2015.

Seeking Precise Portraits of Girls with Autism. Somer Bishop in Spectrum. Published online October 6, 2015. https://spectrumnews.org/opinion/seeking-precise-portraits-of-girls-with-autism

The Lost Girls. Apoorva Mandavilli in Spectrum. Published online October 19, 2015. https://spectrumnews.org/features/deep-dive/the-lost-girls

From Our Archives

Taking Early Aim at Autism. Luciana Gravotta; January/February 2014.

Autism Grows Up. Jennifer Richler; January/February 2015.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Maia Szalavitz is the author of, most recently, Undoing Drugs: The Untold Story of Harm Reduction and the Future of Addiction. She is a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times and author or co-author of seven other books. Credit: Nick Higgins

She is a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times and author or co-author of seven other books. Credit: Nick Higgins

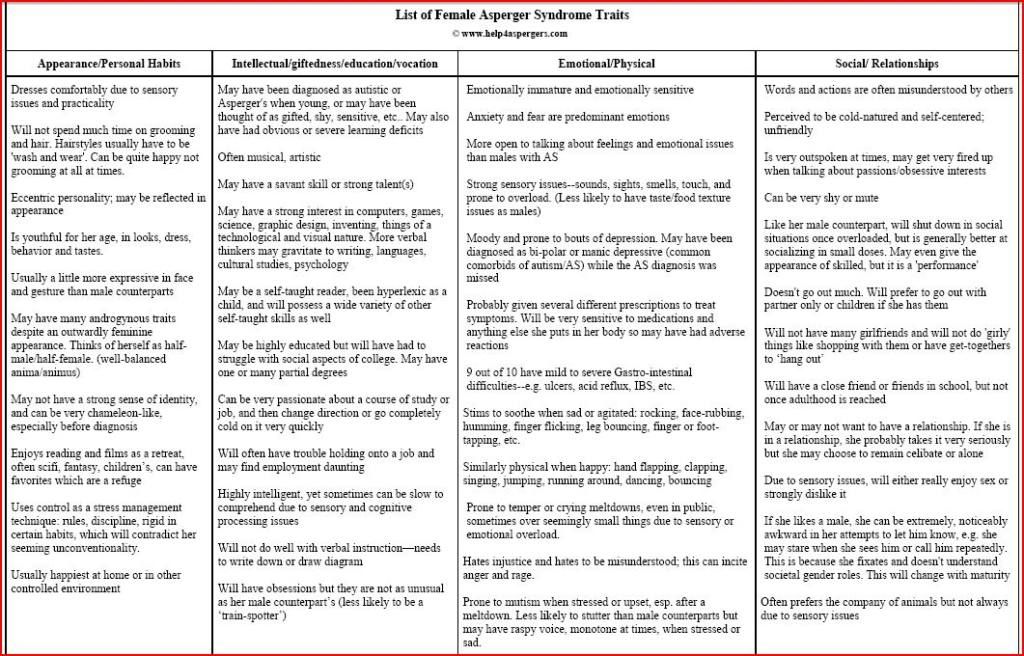

What are the features of the manifestation of autism in girls?

10.12.13

more and more data indicate that autism is different in girls

Author: Eilin Bailey / Eileen Bailey

Translation: Alexander Anosov

Source: Health Central

9000

Autism spectrum disorders are diagnosed four times more often in boys than in girls - in some sources this number is much higher - 10-15 times more often they are detected in men than in women.

Scientists cannot understand why this is due: either men have a certain predisposition to autism and the diagnostic criterion is already “refracted” by male behavior, or autism in women manifests itself in a completely different way and doctors simply cannot detect its symptoms.

One theory is that girls have some kind of "protection" against autism spectrum disorders, perhaps hormones that interfere with autism genes during fetal development.

According to another theory, girls are more socially active than boys, which means that their degree of autism must be higher in order to be noticeable. This theory may explain the following observation: although girls are not diagnosed with autism as often as they might be, they have an order of magnitude more difficulties.

For example, in girls with mild symptoms, the latter are much better compensated or even hidden.

A number of specific differences between male and female autism:

- Girls with ASD are more likely to have learning disabilities and are more likely to have learning difficulties.

- Girls with autism are more likely to be interested in the same things as neurotypical girls, namely: ponies, dolls, princesses, drawings. Boys, on the other hand, may be interested in more unusual subjects. For example, one boy with ASD adored washing machines and spent most of his time looking at and studying them.

For example, one boy with ASD adored washing machines and spent most of his time looking at and studying them.

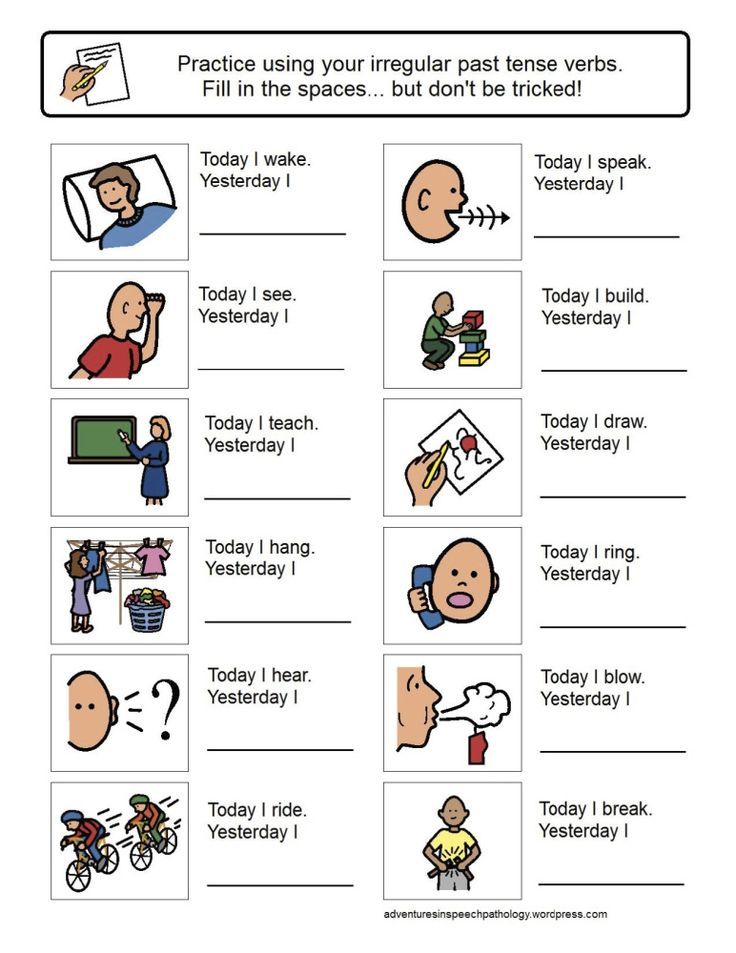

- Autistic boys may be more prone to repetitive behavior - rocking back and forth, twisting objects. Girls are much less likely to do such things.

In one study of emotion recognition, the results of autistic women were close to those of men. However, in tasks requiring attention to detail or strategic thinking, the results of women with ASD were very similar to those of ordinary women. Men with ASD had more difficulty doing these tasks.

Social expectations are one of the factors that make it difficult to make a possible diagnosis of autism in girls. Generally, girls can appear shy, timid, etc. Actually, there is a stereotype in society that girls should be exactly like that. But boys, on the contrary, should be active, mobile, and cases of discrepancy between their behavior and the expected ones attract much more attention.

It is not uncommon for girls to be diagnosed with autism later than boys, for example during middle school, when communication skills become more important. Girls who have learned to "imitate" social skills, such as smiling and nodding, find it difficult to connect with peers. They begin to stand out from the general background.

Girls who have learned to "imitate" social skills, such as smiling and nodding, find it difficult to connect with peers. They begin to stand out from the general background.

I would like to believe that in the near future the situation with diagnosis will change. According to Judith Gould, a physiologist and director of the National Autism Society's Lorna Wing Diagnostic Center, girls and women are now being better diagnosed. This is the result of scientific research and observations of parents. Obviously, the sooner a correct diagnosis is made, the sooner treatment and assistance can begin, and this is so important for people with autism spectrum disorders.

Thanks to Alexander Anosov for the translation.

Diagnosis and Tests

11 Symptoms of High-Functioning Autism in Girls • Autism is

Autism is usually diagnosed in girls with very obvious symptoms, such as severe speech delay, expressed in self-stimulating behaviors (stimuli) and problems with cognitive development .

But if girls' intelligence allows them to mask symptoms, or if these symptoms differ from "classic" autism, then on average, girls are diagnosed later than boys, often only in preadolescence or adolescence. In many ways, these missed diagnoses in girls are linked to our culture. For example, girls are usually expected to be quiet and not so confident.

If a girl seems to be shy and avoids social situations, this may be attributed to femininity, while a similar behavior in a boy is more likely perceived as atypical. In the same way, a girl who is “lost around” and cannot focus on what is required of her can be perceived as “dreamy”, and this does not alert adults.

Symptoms that may indicate high functioning autism in girls

There is no one symptom that means autism. In addition, some of the symptoms may become more pronounced as the girl grows older, but looking back, you can understand that she had them from a very young age.

In addition, the symptoms of autism must be severe enough to seriously interfere with daily life and limit the person's functioning in normal situations. In other words, any girl may have one or two of the following, but this does not mean that she has autism. In addition, if a girl is well adapted and successful in her daily life, then it is very unlikely that she is autistic.

In other words, any girl may have one or two of the following, but this does not mean that she has autism. In addition, if a girl is well adapted and successful in her daily life, then it is very unlikely that she is autistic.

Possible signs of autism

1. The girl relies on other children (usually other girls) in everyday situations, and she allows and relies on other children to speak for her.

2. The girl has passionate, very specific and limited interests. Often these interests do not differ from those of other girls of the same age in content, but they are much more intense, all-consuming and associated with the collection of any available information on the interest, and the form of this interest can be very different from what is expected. Very often these are films or series, celebrities or animals. For example, an autistic girl collects all available information on her favorite series, knows all the facts about the series thoroughly, can talk endlessly about the characters, props, and how the shooting of each series went, but at the same time she does not understand the plot, the motives of the characters and the genre of the series.

3. The girl has unusual sensory problems, such as being intolerant of loud noises, bright lights, or strong smells. (These symptoms are equally common in autistic boys.) Sensory hypersensitivity is not only found in autism, but it is one of its manifestations.

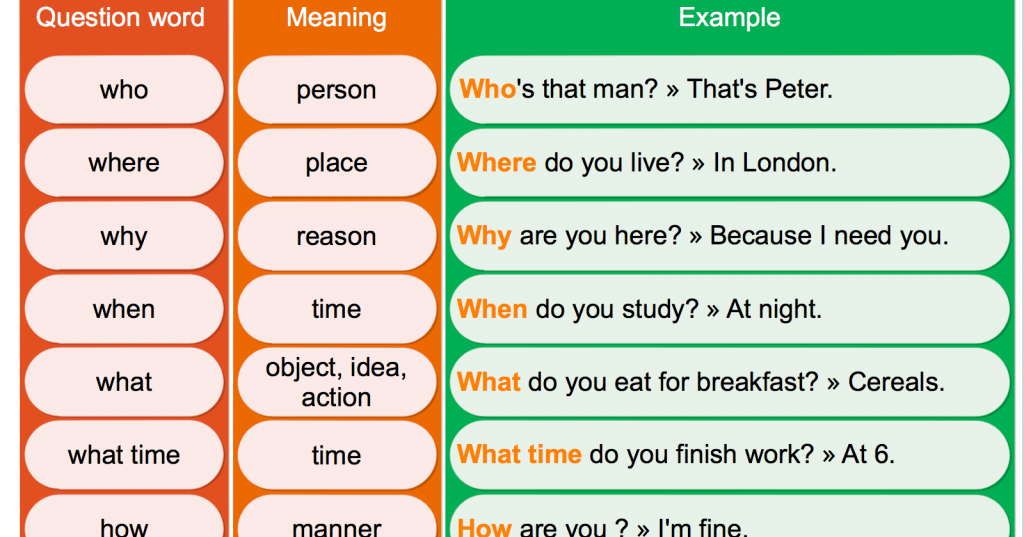

4. It is difficult for a girl to keep up a conversation, she often wants to talk only about the topic of her interest. At the same time, she can speak in a monologue - talk about what interests her, not paying attention to the reactions and answers of the interlocutors. These difficulties can make it difficult for her to make friends, and often autistic girls do not know how to join a peer group or participate in a group conversation.

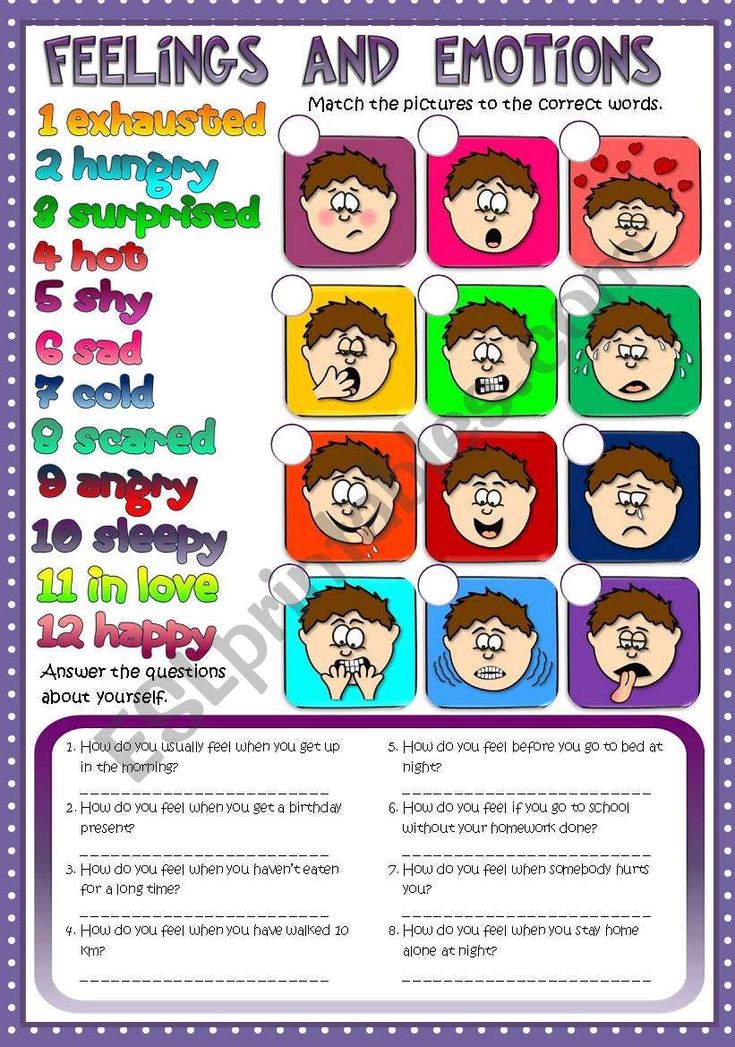

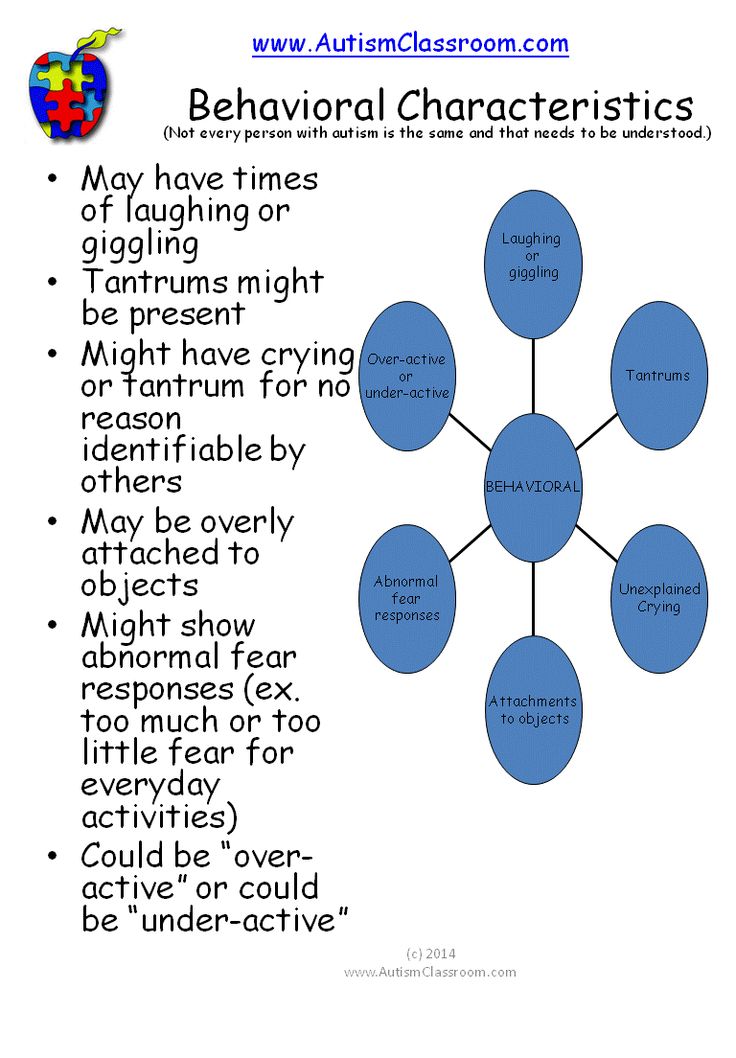

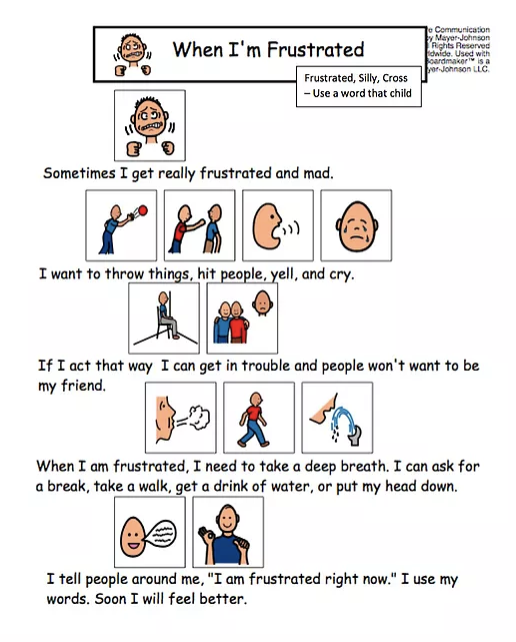

5. An autistic girl may have serious problems with emotional self-regulation: she has a very low threshold for strong emotional reactions, and she has difficulty coping with her feelings. She may have "tantrums" that do not meet expectations for her age. Emotional outbursts can complicate relationships with teachers or lead to disciplinary consequences at school.

6. An autistic girl may suffer from unusually high levels of anxiety, mood swings, and an increased risk of depression. Again, these symptoms are not unique to autism, but autism is associated with mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

7. It is difficult for a girl to communicate with peers, find and maintain friendships, although she may strive for them. She does not seem to see non-verbal cues (for example, when people turn away from her or their facial expressions change). She may try to copy the behavior of other girls, but she does it mechanically, not understanding its meaning, and as a result it is still difficult for her to fit in.

8. The girl is often considered quiet and shy in social situations. Shyness is not a symptom of autism, but an autistic girl may be quiet due to problems with speaking and understanding other people's speech. Because of this, she may not understand how to enter into a conversation and, in general, how to react in social situations, which is why she behaves aloof.

9. The girl is unusually passive. Although some people with autism may be active and glib, passive behavior may indicate that the girl simply does not know what to do or say, so she chooses the safest type of behavior (also approved at school) and tries not to do anything extra do and not say.

10. The girl seemed to have a fairly typical development at an early age, but as she progresses into adolescence, she develops more and more social problems. Research indicates that girls with high-functioning autism learn to mask their difficulties during social interactions, such as why they act passively or let others speak for themselves. For a while, they may be able to camouflage their problems, but by adolescence, social expectations and demands become very complex, and it becomes more and more difficult for a girl to cope with them.

11. The girl has some form of epilepsy. For people with autism, the risk of epilepsy is significantly higher than for people without autism.