History of clinical depression

What Is the History of Depression?

Throughout human history, and long before our current definition for major depression or major depression disorder treatment, the concept of depression has been repeatedly molded and reconceived. As society changes, so does its view of depression, with philosophers, social theorists, artists, and laypeople all adding their own input into what constitutes this hard to pin down experience, which, for many, is part of their daily lives.

Today’s view of depression, as a mood disorder characterized by feelings of emptiness and sadness, contains the echoes of past views and its associations with different characteristics. For this reason, a deeper, more comprehensive understanding of depression necessitates a more in-depth look at how this condition has developed over time.

A Melancholic State of Mind

Considered the “Father of Medicine,” Hippocrates (460 – 370 BCE) was an ancient Greek physician who saw all bodily mechanisms as caused by the relative amount of four internal fluids, called humors: blood, black bile, yellow bile, and phlegm. He believed that a balance between the four brought on good health, while an extreme deficiency or excess of one caused physical ailments.

Greek physician and philosopher Galen (129AD – c. 200/c. 216) expanded upon Hippocrates’ theory, by stating that personality types were also derived from an excess of one of the four humors.

According to the humors theory, melancholic personality type was created by an excess of black bile. Melancholics were accordingly seen as introverted, deep thinkers, who typically related more to the sadder part of the emotional spectrum. It is from this perception of melancholia that our current concept of depression eventually evolved.

Depression and a Dual Approach to Mental Illness

It was 19th Century German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin who began referring to various forms of melancholia as “depressive states,” due to the low mood that defines it. Kraepelin also took a dual approach to mental illness, separating depression into two categories: manic depression and dementia praecox.

Kraepelin’s distinction was based on whether the depression’s source was external or internal: if the depression was caused by an external tragedy, such as the death of a loved one, it was considered a form of manic depression and expected to be episodic and passing.

However, depression that did not stem from a known, external cause was understood to have “grown” out of the individual’s psyche, and as such was considered a break from reality that is similar to present-day schizophrenia.

The distinction Kraepelin made between both types of depression is still relevant today: many patients continue to recount how people are more willing to offer sympathy if the source of their depression is clearly understood: as such, an individual whose depression was caused by witnessing a traumatic event is likely to receive more social support than someone whose depression appeared during adolescence.

Mourning a Love with No Name

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, published his own thoughts on depression in his 1917 essay, Mourning and Melancholia. In it, Freud described melancholy in a similar manner to our current view on depression, elaborating that melancholy is defined by a sense of loss that arises when the object that has been lost is unknown, due to the mental process of repression.

In it, Freud described melancholy in a similar manner to our current view on depression, elaborating that melancholy is defined by a sense of loss that arises when the object that has been lost is unknown, due to the mental process of repression.

Freud posited that depression interferes with the normal mourning process, causing the individual to feel a general sadness when coming in contact with the world at large, while experiencing the anguish and hopelessness assailing them as inescapable. Rather than internalize the positive aspects of the person or object that has been lost, and come to terms with their shortcomings, the person experiencing melancholy redirects any lingering resentment toward themselves, while maintaining the memory of their lost loved one as an ideal, untouchable version of who they were in real life.

A More Grounded View of Depression

Moving away from psychoanalysis, in favor of a more empirically-based approach to depression, was Swiss psychiatrist Adolf Meyer. The eventual President of the American Psychiatric Association, Meyer argued in favor of considering biological factors, together with mental and familial ones, as elements that significantly contribute to the appearance of depression.

The eventual President of the American Psychiatric Association, Meyer argued in favor of considering biological factors, together with mental and familial ones, as elements that significantly contribute to the appearance of depression.

ICD, DSM and a Consensus of Diagnosing Mental Illness

With mental health theories abounding from the end of the 19th Century, it became necessary to reach a working consensus on how to identify, group and treat mental health conditions based on statistical field data. Thus, a number of attempts were made to create a comprehensive mental health classification system.

Eventually, two main systems emerged: the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death (ICD) in 1949, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952. While the ICD examines both physical and mental ailments and is used across the globe, the DSM specifically examines mental disorders and is primarily used in the US. Both are periodically updated to reflect the changing times and their shifting approaches to mental health.

Both are periodically updated to reflect the changing times and their shifting approaches to mental health.

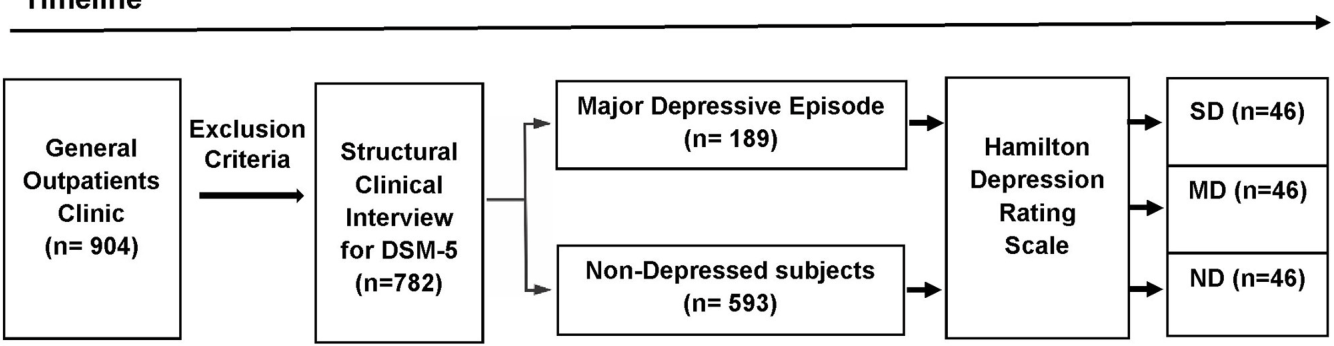

The 1960s and ‘70s saw a push for greater reliance on statistical analysis, with the field of psychiatry aiming to solidify its status as an empirical medical profession. As a result, more sophisticated tools were developed for assessing depression, chiefly the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HDRS) from 1960, and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) from 1961. Both are considered gold standards and are still used today.

Following these changes, the DSM-III, which was published in 1980, aimed to reassess how people talk about mental health, by moving away from pathologizing language and offering a more compassionate approach. This helped counter some of the stigmas that individuals battling depression had to face (and still often do).

As times changed, so did the ICD and DSM’s definitions of depression, with the various symptoms that go into the diagnosis reflecting up-to-date field data. As an example of this change, the DSM-IV, which was published in 1994, excluded instances of depression that can be better explained by bereavement.

As an example of this change, the DSM-IV, which was published in 1994, excluded instances of depression that can be better explained by bereavement.

DSM-V, which was published in 2013, added a “mixed features” sub-diagnosis of depression that includes manic episodes, in addition to an “anxious distress” sub-diagnosis that is defined by having at least two of the following symptoms: tension, restlessness, difficulty concentrating due to worrying, fear that something awful might happen, and feeling a loss of control.

Biological Breakthroughs in Treating Depression

In addition to the diagnostic developments of the ICD and DSM, the mid-20th Century saw a revolution in treating depression when antidepressant medication was introduced as an efficient and increasingly common healthcare option. Addressing depression through medication highlighted the possible biological and genetic causes behind it, and offered many patients long-awaited symptom relief.

Antidepressants affect the brain’s secretion of neurotransmitters, which are chemicals that relay information between nerve cells. Over the years, several generations of antidepressants have been approved and made publicly available, with each influencing the neural pathways involved in depression in a different way.

Over the years, several generations of antidepressants have been approved and made publicly available, with each influencing the neural pathways involved in depression in a different way.

The three classes of antidepressants most commonly prescribed today are:

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), which work on norepinephrine and were introduced in the late 1950s and early ‘60s. Examples include Elavil and Tofranil

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which were introduced in the mid-1980s. Examples include Prozac and Zoloft.

- Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which were introduced during the mid-‘90s. Examples include Cymbalta and Effexor.

All three classes of medication have been found to effectively alleviate symptoms of depression, though their efficacy can only be gauged after several months’ treatment. In addition, their accompanying side effects can sometimes be severe, and include weight gain, sexual dysfunction, nausea, blurred vision and increased heart rate.

Offering an Alternative View: Existentialism, Humanism, Cognitive Psychology

The writings of earlier visionaries (in particular Freud) helped the modern world begin to conceptualize and approach depression. Eventually, though, these consensus points of view were given a somewhat humbler perspective, as more contemporary approaches to depression began to be considered, as well. Enter existentialism, humanism and cognitive psychology, as three branches of psychology that developed during roughly the same time period, while offering their own takes on depression.

Existentialism: Existentialism gained popularity following WWII, due to its focus on the individual’s search for meaning in a world that often seems incomprehensible.

Among the leading existential theorists was psychologist Rollo May, who described depression as “the inability to construct a future.” He posited that when a person is unable to imagine a future where they can truly live out their passions, they experience a deep helplessness that can develop into depression. To counter this, May encouraged accepting sadness as part of the human experience, rather than deny its existence.

To counter this, May encouraged accepting sadness as part of the human experience, rather than deny its existence.

Humanism: Humanism views people as agents of change in their own lives, with depression arising when meeting one need comes at the expense of another.

Psychologist Abraham Maslow illustrated this point in his 1943 paper on the “hierarchy of needs,” describing how depression is caused when more urgent survival needs (such as food, shelter or security) are met at the expense of social and emotional needs. As a result, someone who, for example, invests all their time and energy in working toward financial security, may become depressed and emotionally depleted due to a lack of close relationships.

Cognitive Psychology: Cognitive psychology grew out of the “cognitive revolution” of the 1950s-’80s, striving to understand the mind through empirical tools. A leading figure in this movement was psychiatrist Aaron Beck, who developed the BDI assessment tool for depression, as well as Beck’s cognitive triad for depression.

Looking at the factors contributing to depression, Beck reasoned that an individual’s beliefs regarding themselves, the world and the future influenced each other and determined their susceptibility to depression: as such, an individual who believes they are to blame for their depression, that the world is a fundamentally sad and lonely place, and that none of this will ever change, will likely develop depression as a result.

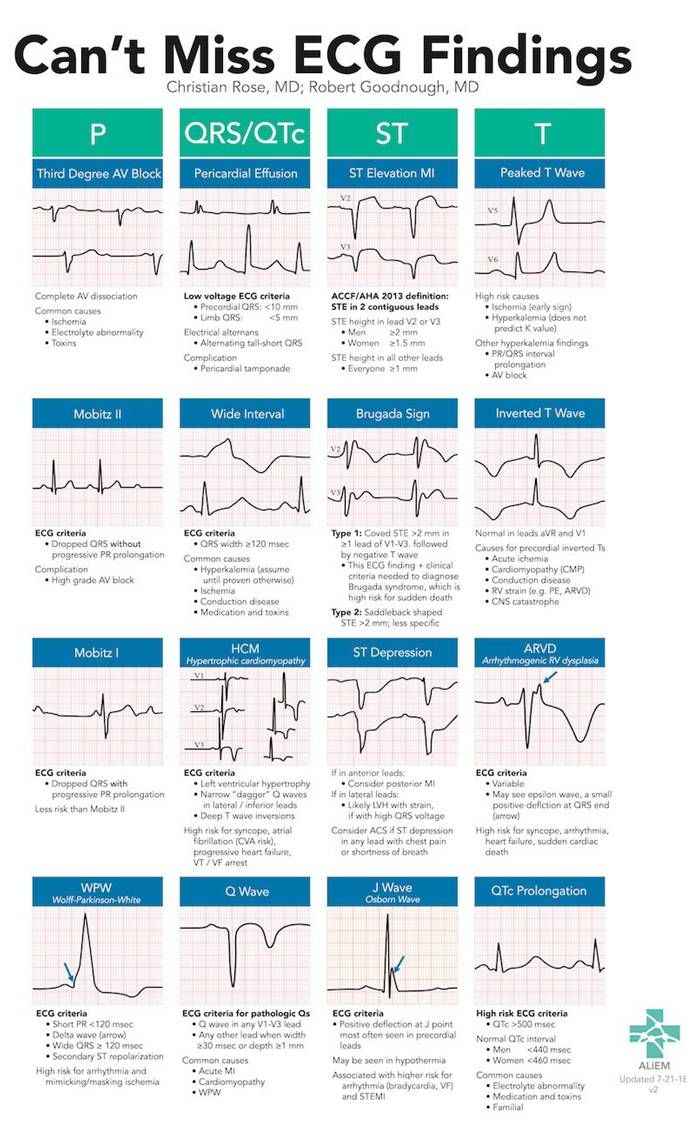

Medical Technology Breakthroughs: ECT, TMS and Deep TMS

During the 20th Century, several cutting edge medical technologies were invented and shown to effectively treat depression. Out of the different options that were made available, ECT, TMS and its most recent advancement, Deep TMS have gained greater professional and public recognition

ECT: Electroconvulsive therapy was originally used to treat schizophrenia, before it was shown between the 1960s-‘80s to be even more effective in treating mood disorders, depression in particular. As a result, it is presently primarily used to treat this condition.

As a result, it is presently primarily used to treat this condition.

ECT works by using electric pulses to stimulate the brain and induce a brief set of seizures. While it has been shown to be highly effective in treating severe depression, ECT does have its drawbacks: namely, that it requires full sedation, the possibility of short-term memory loss, and its negative public perception, much of which has to do with misinformation characterizing it as a traumatic, personality-altering procedure.

TMS: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation has been clinically available since 2008, as a non-invasive option for treatment-resistant patients with depression who are wary of ECT. The procedure initiates a series of electromagnetic pulses, held inside a figure-8-shaped handheld device. Once activated, the pulses regulate the neural activity of brain structures that have been shown to be related to depression.

BrainsWay’s Deep TMS HelmetThough TMS has been shown to be both safe and effective in alleviating symptoms of depression, certain limitations have been shown in regard to this original, standard form of TMS: first, the figure 8-coil’s relatively narrow scope means that standard TMS can only regulate a few structures at any given moment. This means that TMS sometimes suffers from targeting issues, as the regulating pulses may miss some of the relevant structures. Additionally, standard TMS at times has trouble directly stimulating deeper brain structures, which can also possibly decrease the treatment’s efficacy.

This means that TMS sometimes suffers from targeting issues, as the regulating pulses may miss some of the relevant structures. Additionally, standard TMS at times has trouble directly stimulating deeper brain structures, which can also possibly decrease the treatment’s efficacy.

Deep TMS: Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, or Deep TMS, an advancement of the standard, figure-8 TMS treatment, answers some of the issues raised with its predecessor. Deep TMS was first introduced in 1985, and gain FDA clearance in 2014, as a form of noninvasive brain stimulation, and like standard TMS, utilizes magnetic fields to safely and effectively regulate brain structures associated with depression, as well as other mental health conditions.

Deep TMS’s patented H-Coil technology is held inside a cushioned helmet that is fitted onto the patient’s head. The magnetic fields produced by the H-Coil not only manage to reach wider areas of the brain, but also to directly stimulate structures located in deeper regions of the brain, which contributes to the treatment’s efficacy.

Depression Today

These days, our perception of depression is the most diverse and well-studied it has ever been. The vast interest in this condition has, however, caused a divergence in fields of study, treatment methods and takes on what constitutes depression as a mental health disorder. All these possibilities can understandably confuse those dealing with depression, as well as their caregivers and others around them. It is thus important to stay well-informed as to the different available options you have for battling depression, and figure out what works for you in a supportive, professional and caring environment. Consulting a mental health professional familiar with your medical and mental health history is highly advisable, as is considering both tried-and-true methods and newer, low-risk alternatives.

Be it through deep psychoanalytic treatment, a more existential approach, exploring scientifically proven treatment options like Deep TMS, incorporating medication into your healthcare regimen or taking a look at the detrimental set of beliefs that define it, individuals battling depression today are able to benefit from those who came before them. The philosophy, research and cultural shifts that continue to this day have resulted in a multitude of perspectives, a range of available treatment options, and the somewhat comforting knowledge that our passion to gain a better understanding of depression has already progressed us as a society toward a fuller, broader and more compassionate view of this complex condition.

The philosophy, research and cultural shifts that continue to this day have resulted in a multitude of perspectives, a range of available treatment options, and the somewhat comforting knowledge that our passion to gain a better understanding of depression has already progressed us as a society toward a fuller, broader and more compassionate view of this complex condition.

You may also be interested in...

Types, Treatment Models, and Studies

-

Ancient Greece

-

Renaissance

-

The 18th Century

-

The 1950s and 60s

-

Current Times

Depression and its unipolar varieties are one of the oldest emotional and psychological illnesses known to man. Currently, the World Health Organization estimates that over 300 million people across the globe suffer from the disease.

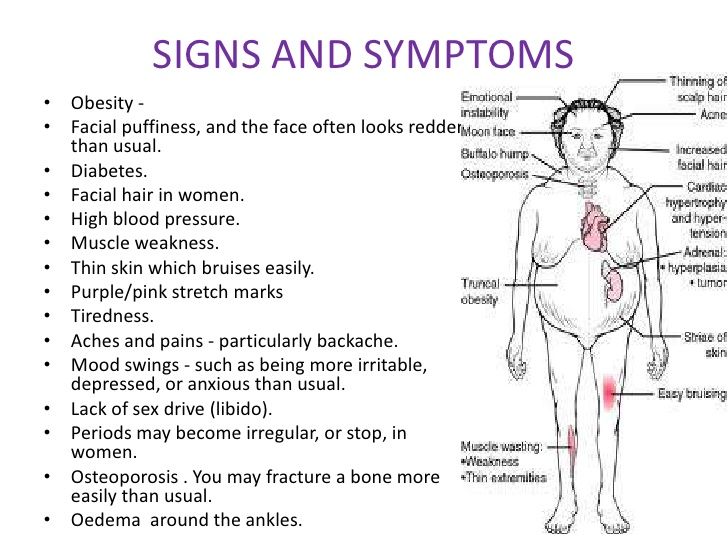

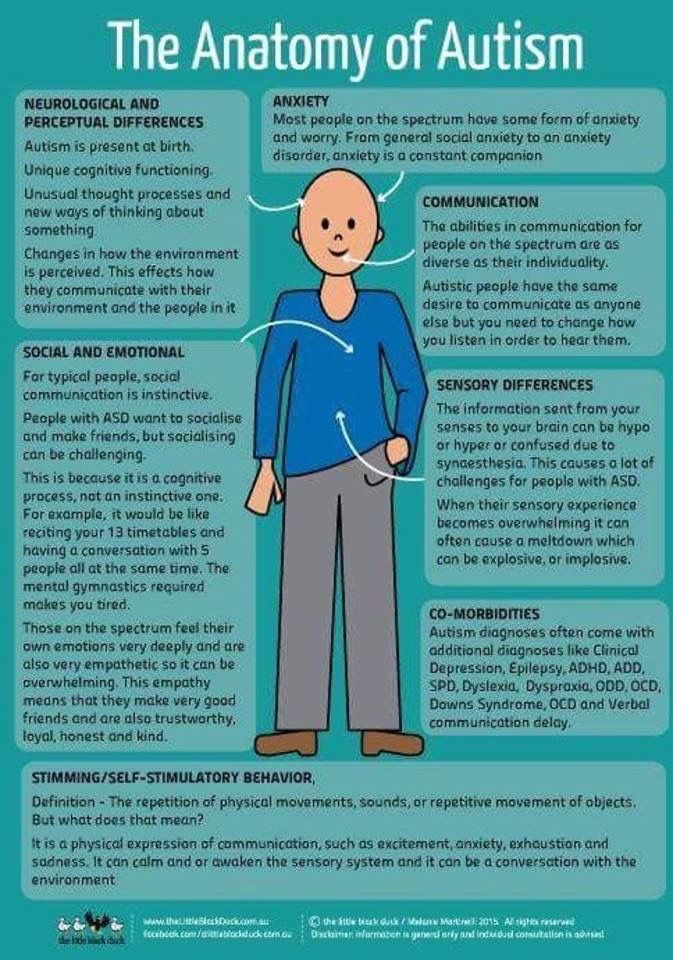

Symptoms of depression are behavioral, emotional, and physical. Sufferers experience a marked change in mood, outlook, and habits. They may go from being outgoing and confident, to negative and socially withdrawn. Depression can cause someone to quit their job, stop going to school, or divorce their spouse. The disease wreaks havoc on a person’s personal and professional life, and can also cause physical symptoms, such as aches, muscle pains, severe fatigue, and slowed movements.

They may go from being outgoing and confident, to negative and socially withdrawn. Depression can cause someone to quit their job, stop going to school, or divorce their spouse. The disease wreaks havoc on a person’s personal and professional life, and can also cause physical symptoms, such as aches, muscle pains, severe fatigue, and slowed movements.

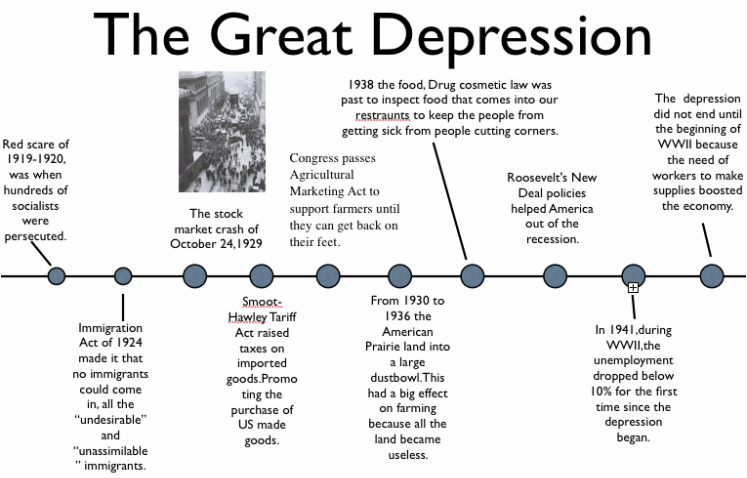

Since written and recorded history began several millennia ago, depression has been diagnosed, treated, and studied. The first recorded instance of the disease was written in Mesopotamian texts in the second century B.C. Understandings of mental illnesses were rudimentary, at best. Ancient Mesopotamians, Chinese, and Egyptian civilizations thought demonic influences caused depression. Depression sufferers were exorcised by priests, shamans, and religious leaders and authorities.

Treatments in societies where mental disorders were thought to have their origins in the demonic world and the dark arts were barbaric. Sufferers were put in leg irons, beaten, or starved. In medieval Europe, people thought to have depression were also drowned or burned as witches. Medieval Europeans thought the disorder was contagious, and all sufferers needed to either be destroyed or locked away like prisoners.

In medieval Europe, people thought to have depression were also drowned or burned as witches. Medieval Europeans thought the disorder was contagious, and all sufferers needed to either be destroyed or locked away like prisoners.

While the majority of ancient and medieval societies believed depression was something caused by demons and witchcraft, there was always an alternative, enlightened school of thought running throughout recorded history. The ancient Romans and several Greek physicians thought depression was a mental disorder, caused by grief or blood and bile imbalances. The cure was exercise, music, hydrotherapy, or a primitive form of behavioral therapy, where good behavior was rewarded.

Physicians believed depression had its roots in a specific triggering event or a physical imbalance of the bodily humours. Hippocrates used bloodletting as a way to restore the humours in depressed patients.

During the Renaissance in Europe, spanning the 15th through the 17th centuries, treatments and views of depression were highly polarized. Most of society believed people with depression were witches and demons, and burnings and executions were commonplace. However, the medical communities and professions at the time still carried the view that depression was a brain illness, and people with mental disorders deserved fair and humane treatment for their afflictions.

Most of society believed people with depression were witches and demons, and burnings and executions were commonplace. However, the medical communities and professions at the time still carried the view that depression was a brain illness, and people with mental disorders deserved fair and humane treatment for their afflictions.

Robert Burton, an Anglican clergyman, wrote and published the Anatomy of Melancholy in 1621. In it, he asserted that depression had specific causes, such as poverty, fear, and isolation. Burton suggested music, bloodletting, travel, herbal medicines, and even marriage as a cure for the disorder.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, views on depression took a rather grim turn. During this period, people with the disorder were thought to have a weak temperament which was inherited; therefore, there was no cure and nothing anyone could do for people with the disease. Patients were locked up in asylums or condemned to a life of poverty and homelessness.

In the latter part of the 19th century, the medical community began to experiment with different techniques for treating the disorder. Immersion therapy, spinning stools, lobotomies, and electroshock therapy (ECT) were all invented and deployed at this time.

Lobotomies and ECT were in their infancy, and use was primitive. Lobotomy patients were sometimes rendered comatose or even killed with a botched procedure. With ECT, inexperienced doctors sometimes used too high of a voltage or failed to take necessary safety precautions which are commonplace with the practice now.

In the early 1900s, Sigmund Freud proffered the theory that depression had its roots in the concept of ‘loss,’ either real or perceived within the patient’s subconscious. Freud was one of the first psychologists of the modern era who developed a form of talk therapy for depressed patients. During Freud’s time, other schools of thought, mainly physicians, still believed depression had its roots in imbalanced brain chemistry.

During the 1950s and 1960s, diagnosis and treatment for depression made significant headway within the scientific and medical communities. Doctors noticed a drug used to treat tuberculosis was having a positive effect on patients with comorbid depression. At this time, doctors began to study the effects of pharmacology on the disorder. Drugs were developed and deployed in treatment methods for the disease.

After centuries of back-and-forth between depression as caused by a chemical imbalance and depression rooted in an emotional response to outside stimuli, doctors started treating depression as if both things caused it. Medications, along with talk therapy, were first used for depressed patients during the mid to latter half of the last century. The practice still holds.

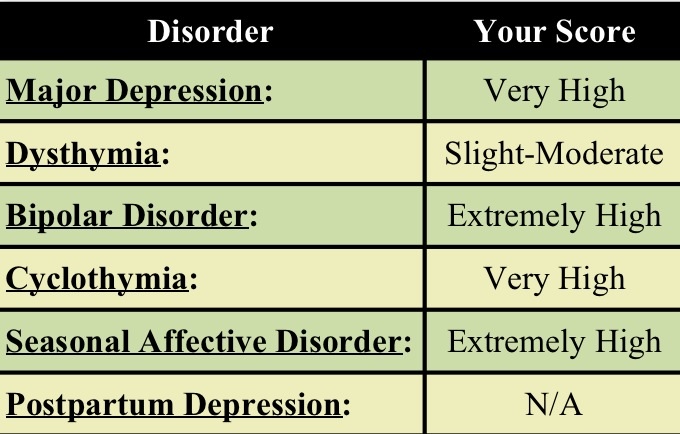

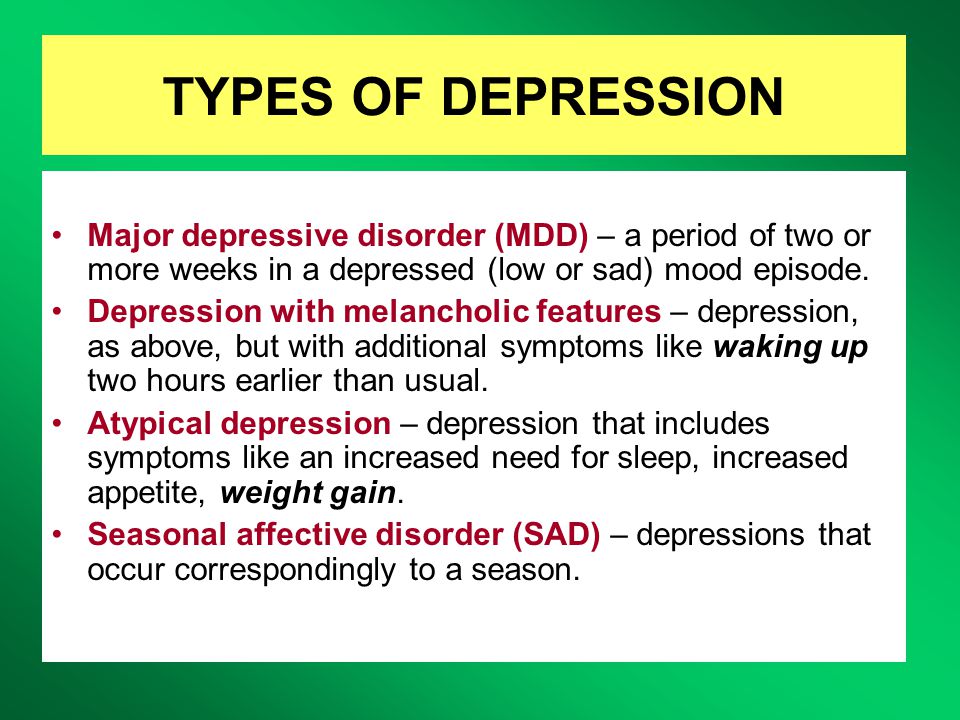

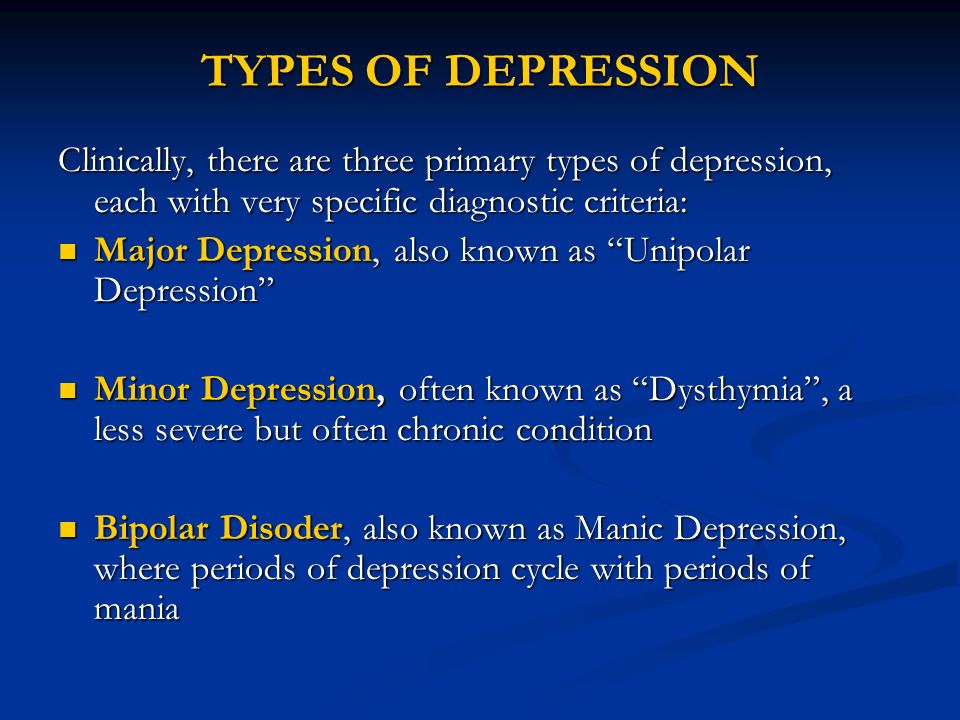

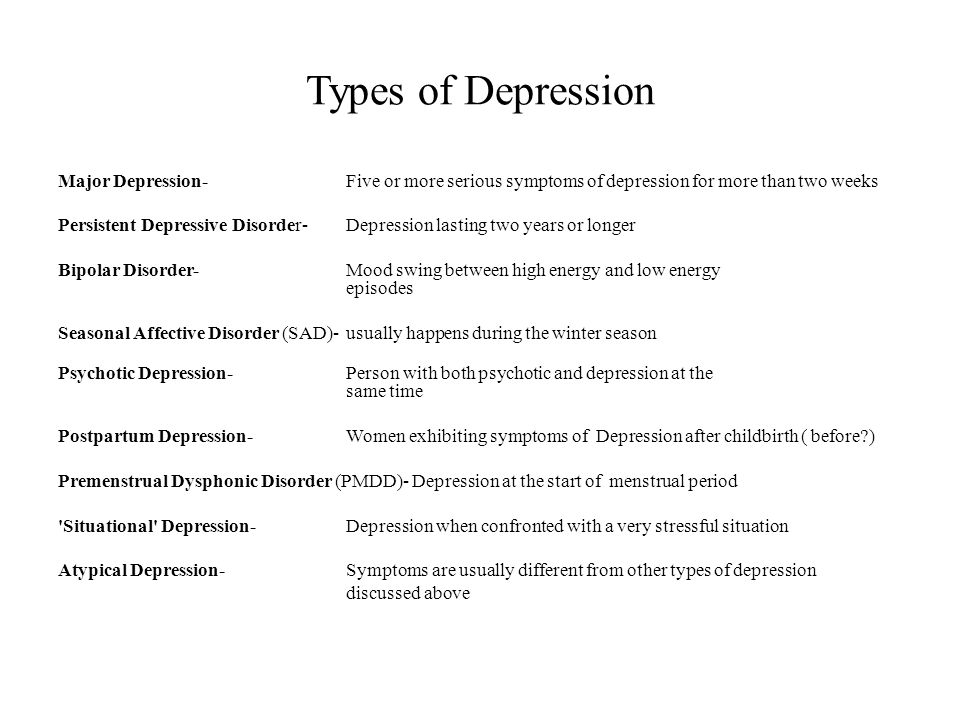

At this time as well, depression started to be classified into subcategories.

- Major, or Unipolar Depression

- Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD)

- Postpartum Depression

- Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD)

- Dysthymia

- Psychotic Depression

- Bipolar Depression

- Anxiety, PTSD, and Panic Attacks

Anxiety and panic attacks can sometimes trigger an episode of depression. While these subcategories have always existed, it wasn’t until the middle of the 20th century that doctors, therapists, and scientist began to actively recognize and classify the different symptoms and triggers of these depressive subtypes.

While these subcategories have always existed, it wasn’t until the middle of the 20th century that doctors, therapists, and scientist began to actively recognize and classify the different symptoms and triggers of these depressive subtypes.

With this practice of subcategory diagnosis in place, doctors can now tailor and customize more effective treatment options for their patients. Modern medicine doesn’t view depression as an either/or disease. Environmental triggers, genetics, temperament, and physical and chemical causes can all trigger a depressive episode. Having a close relative with the disorder, having an emotional or sensitive disposition, and experiencing a stressful event have all been found to kick-start a depressive episode in at-risk individuals.

With a better understanding of the disease, patients are no longer abused and isolated from society. They are treated with medications, brain stimulation techniques like ECT or TMS, and behavioral and talk therapy sessions.

Depression, unfortunately, does not have a cure. But, these techniques and treatment options are incredibly effective at alleviating a patient’s symptoms. Like any other chronic illness, depression requires ongoing care and maintenance to prevent a relapse. After initial treatment and remission, average relapse rates for patients who’ve experienced one depressive episode is 50%. For patients with two episodes, relapse is at 70%, and for those with three or more, relapse rates are as high as 90%.

Despite the high risk of relapse, having a prevention plan or maintenance plan is crucial for the patient’s safety and well-being. With adequate procedures in place, doctors and patients can either prevent a relapse from ever occurring or substantially limit the severity and duration of a relapse.

Since depression is an incredibly complex disorder, with different subcategories and symptoms that vary by individual, treatment plans may take months or years of experimenting to get right. While most patients do respond well to current antidepressant medications and therapy, about one-third will have treatment-resistant depression.

While most patients do respond well to current antidepressant medications and therapy, about one-third will have treatment-resistant depression.

Treatment-resistant depression is depression that doesn’t respond to medication or therapy attempts. Most of the costs and prevalence of depression rates are attributed to treatment-resistant strains of the disease. But, older antidepressants, such as MAOIs, and ECT and transcranial magnetic therapies (TMS) are incredibly effective at alleviating the pain of treatment-resistant depression.

With ECT and TMS, patients aren’t subjected to some of the more unpleasant side effects of medications. TMS is also non-invasive and is a quick and simple outpatient procedure. Magnetic coils are placed onto the patient’s forehead, where electromagnetic pulses are aimed at areas of the brain responsible for mood and emotional regulation. TMS is painless, and studies indicate that for the majority of patients, TMS dramatically reduces depressive symptoms where medications and therapy have failed.

What is the current state of depression in the U.S.?

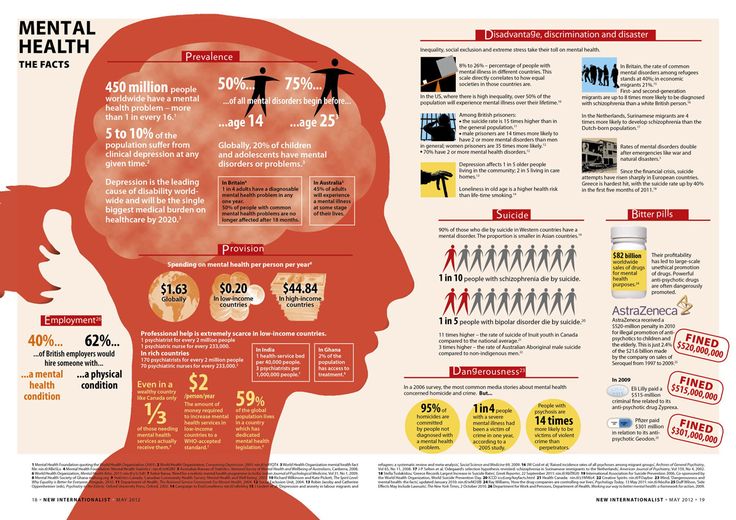

The World Health Organization and the UN all recognize depression as a severe disorder, affecting millions of people per year. Depression and suicide create a ripple effect. For every suicide, up to 8 people are directly affected. While there are numerous and effective treatment methods for the disorder, depression rates are on the rise. Studies of U.S. adults, those aged 12 and older, show depression and all of its subcategories rising since the early 2000s. Depression amongst children, teens, and young adults have grown the most, while suicide attempts amongst middle-aged men have skyrocketed.

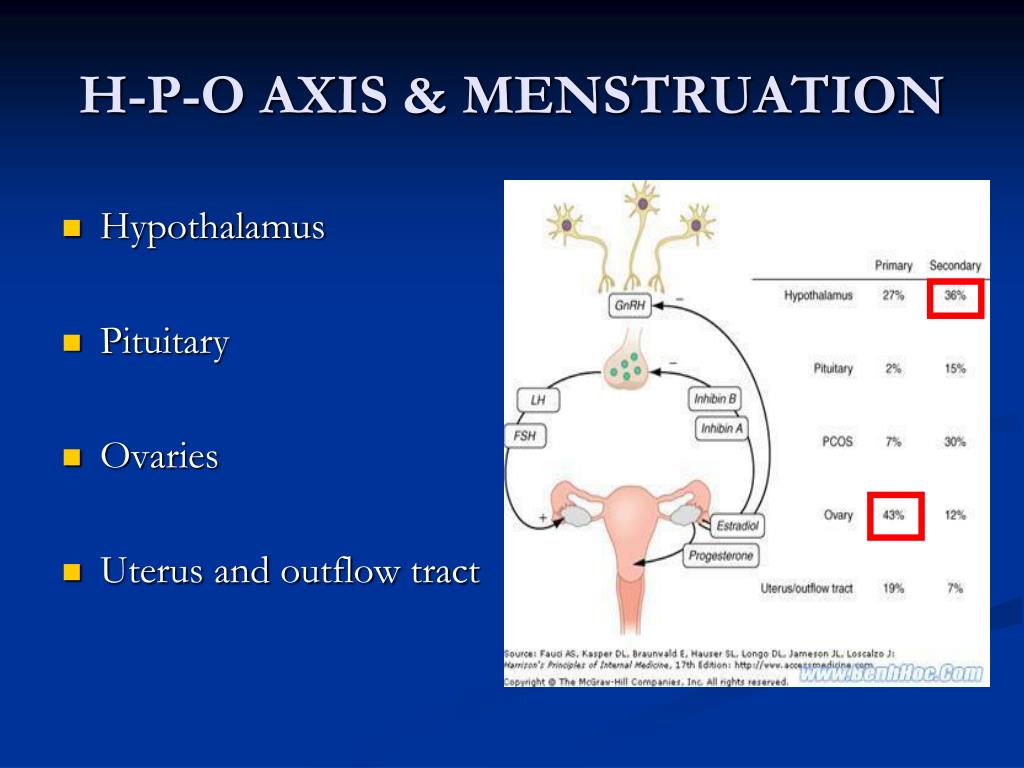

Women are also more likely to receive a diagnosis in their lifetimes than men. Two subcategories of depression, postpartum and PMDD, are unique to women. On average, a woman will experience more trauma and stressful, adverse life events than a man, increasing her risk of developing the disorder.

Comorbid disorders are also on the rise. Anxiety, along with suicidal ideation and self-harm, and drug addiction have all increased, leading to more depressed adults within society. Government authorities, federal and local, have been teaming up to bring more easily accessible mental health resources to at-risk communities and demographics.

Anxiety, along with suicidal ideation and self-harm, and drug addiction have all increased, leading to more depressed adults within society. Government authorities, federal and local, have been teaming up to bring more easily accessible mental health resources to at-risk communities and demographics.

For example, poverty plays a role in depressive rates. But, it is still unclear whether poverty is the trigger or perpetrator of depression. Surveys indicate that in places with high rates of depression and other mental disorders, that these places are also impoverished.

In Appalachia, one of the poorest regions in the U.S., up to 15% of the adult population suffers from a mental health disorder. But, authorities believe high rates of depression in places like Appalachia may have more to do with the fact that people in impoverished areas don’t have the resources or access to treatment that wealthier populations do. Therefore, it’s possible that poverty isn’t necessarily the cause of depression, but may, in fact, indicate that it prevents people from getting help for their symptoms.

What have recent studies discovered about the disease?

Recent studies indicate that depression is even more complicated than initially believed, involving many areas of the brain. Brain imaging scans suggest that changes in the brain, along with environmental stressors, converge into a ‘perfect storm’ to trigger a depressive episode in at-risk populations.

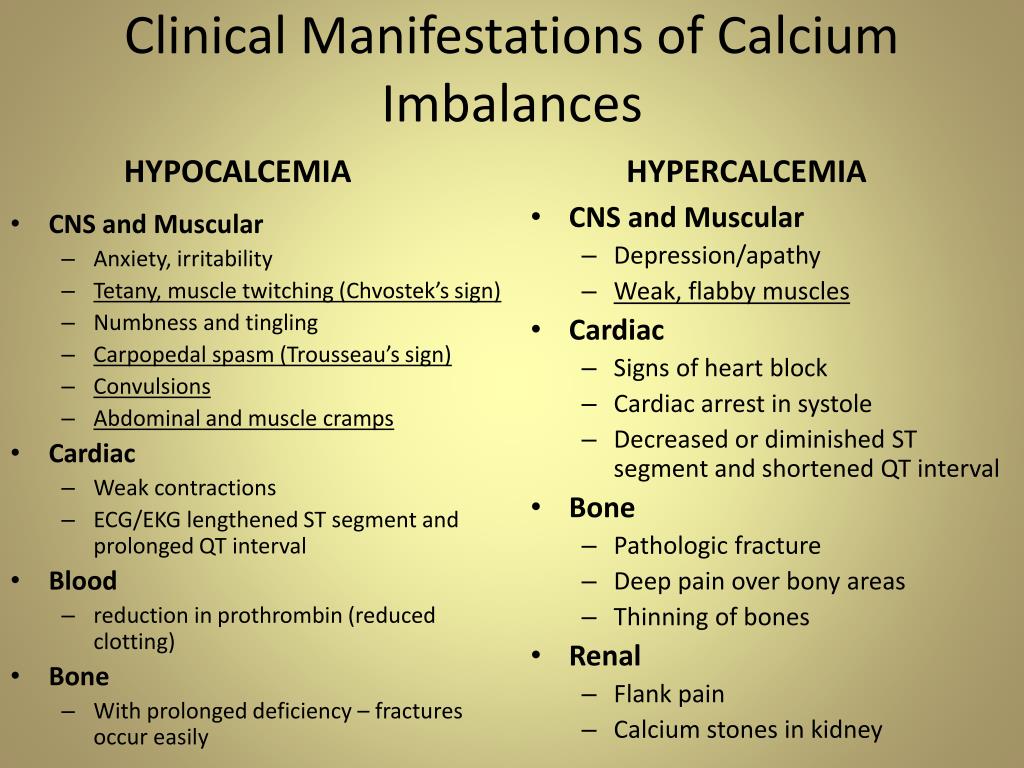

While it is true that an imbalance of brain chemistry is a significant factor in depression, specific areas of the brain may also play a role in its occurrence. Dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin are neurotransmitters, or chemicals that regulate mood, and energy. An imbalance here can cause depressive symptoms. Modern medications, SSRIs, and SNRIs rebalance these chemicals.

But, research shows that regions of the brain, the amygdala, hippocampus, and thalamus, all play a role in mood and emotional regulation. TMS can target these specific areas of the brain and is one of the reasons why the treatment is so useful when medications fail.

Twin studies have also found a genetic prevalence of mental health disorders. An identical twin whose sibling has a mental health disorder has a 60% to 80% change of developing the condition as well. In fraternal twins, the risk is 20%. Individuals with a first-degree relative who has depression have a 1.5% to 3% greater chance of getting the disorder than people with no genetic history of depression.

Psychologists have found that a person’s temperament may also influence their risk of developing depression. People who withdraw from the world, who isolate themselves, or who hold negative assumptions about the world or others have a higher risk of experiencing depressive symptoms. But, behavioral and emotional regulation can lessen the chances of depression if a person is aware of their tendencies.

Also, stressful events are known triggers. In these cases, psychotherapy can help individuals regulate their emotions and responses to adverse events and situations, limiting the occurrence of depressive symptoms.

Despite the prevalence and severity of depression, modern medicine and advances in brain imaging and technology have developed numerous, practical techniques for managing the disorder. Cutting-edge, painless and noninvasive methods like TMS can quickly treat the symptoms of depression and help patients regain their well-being. If you or someone you love is suffering from depression, don’t hesitate to reach out and get help today.

Adult Depression - Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment

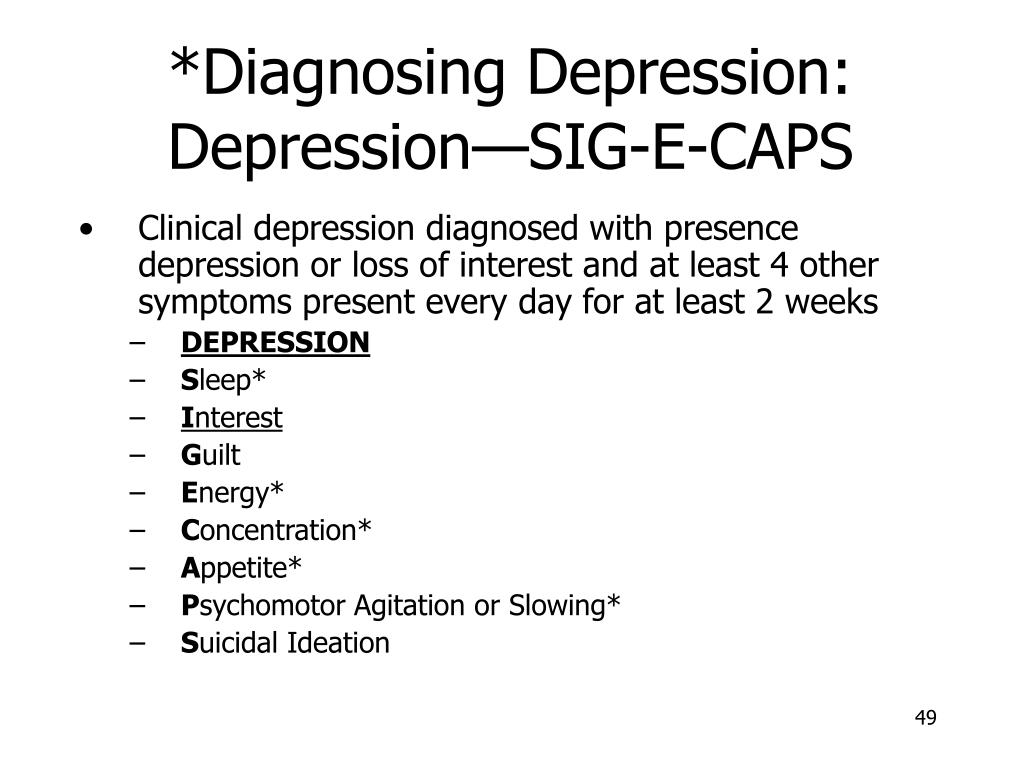

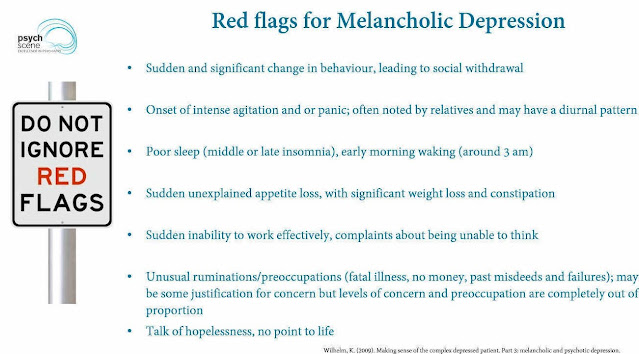

Common symptoms include persistent low mood, loss of interest and enjoyment, changes in sleep and appetite, feelings of guilt or self-criticism, decreased concentration and energy.

Affects 5-10% of patients in primary care settings.

Risk factors include prior depression and a family history of depression. Recent loss, stress, or illness can contribute.

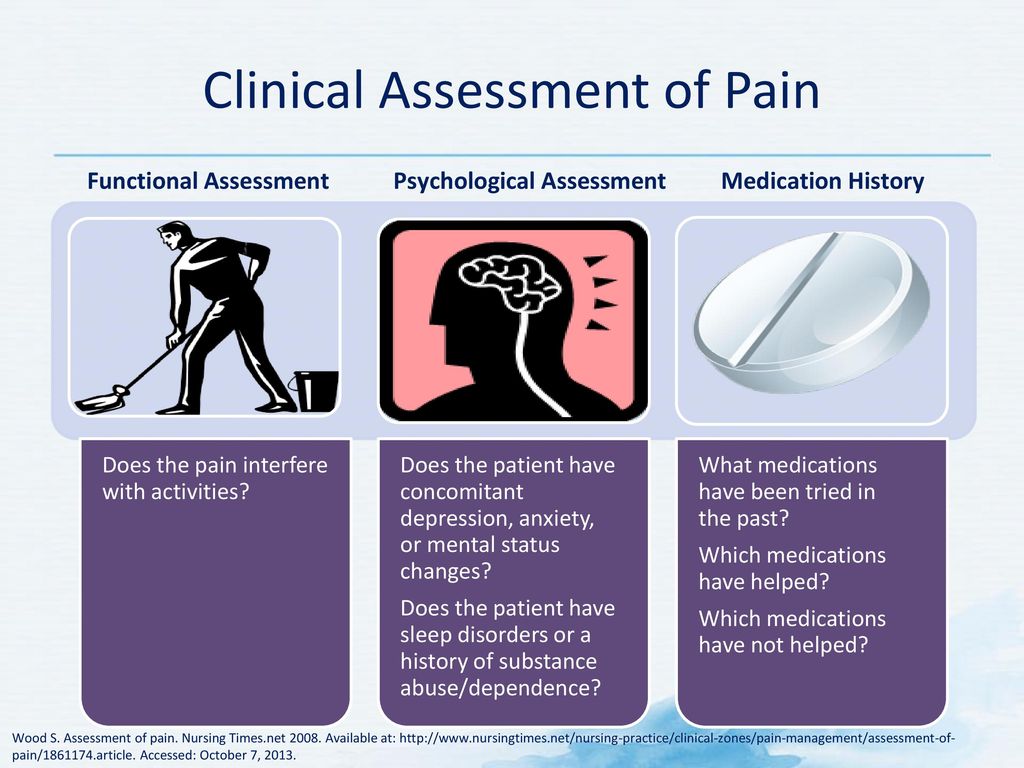

Self-assessment forms are very important for screening and diagnosis, but clinical diagnosis is also required. A positive screening should initiate a detailed history, mental status assessment, treatment, and follow-up. nine0003

A positive screening should initiate a detailed history, mental status assessment, treatment, and follow-up. nine0003

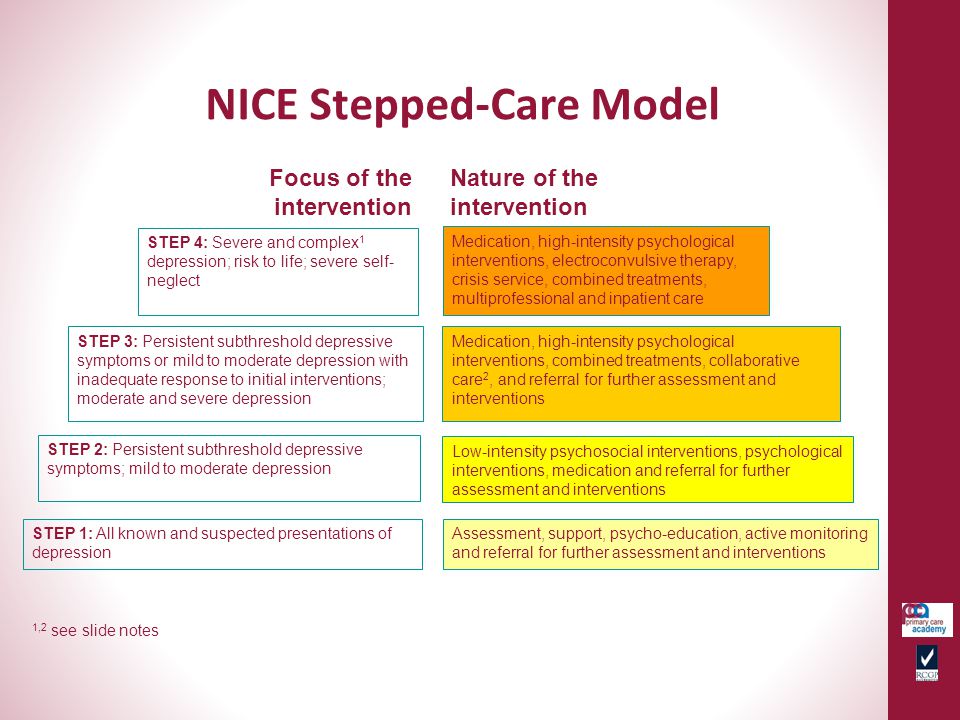

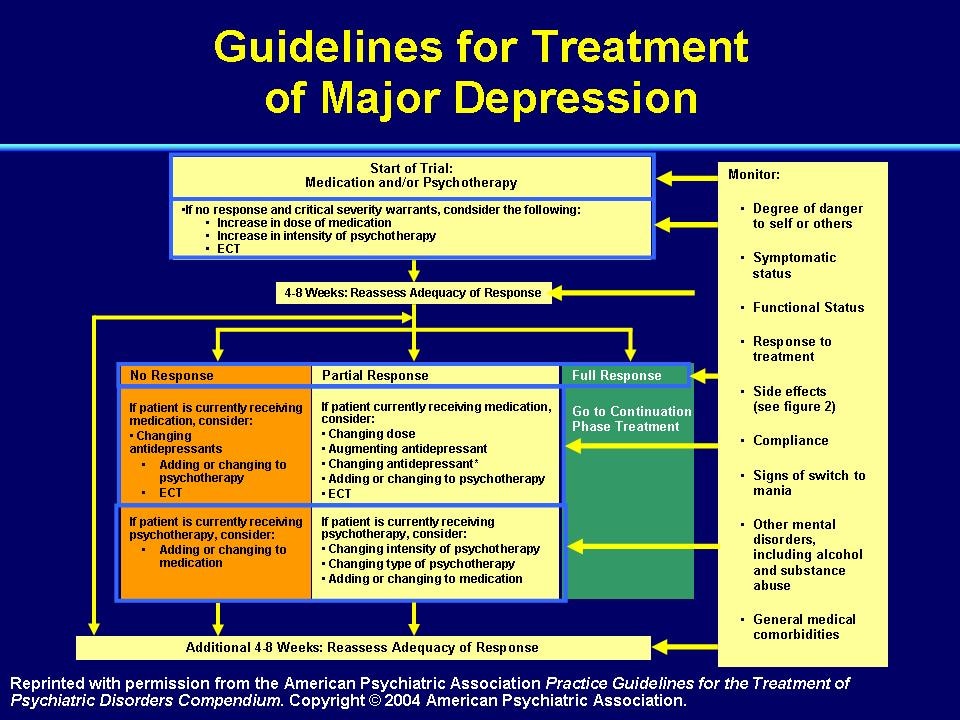

Most patients respond well to drug treatment, therapeutic talks, or a combination of the two.

Suicidal ideation may occur before and during treatment, so early close monitoring is recommended.

Definition

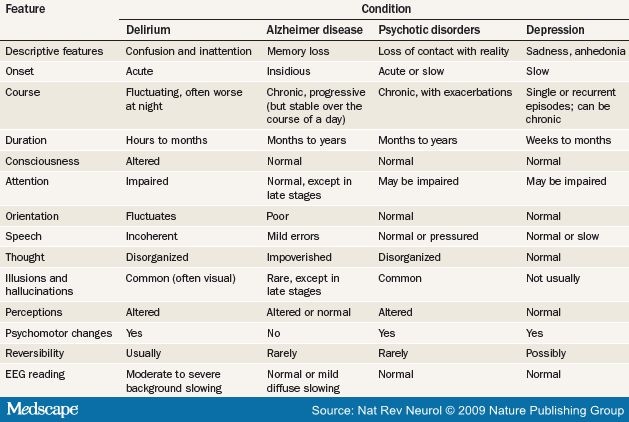

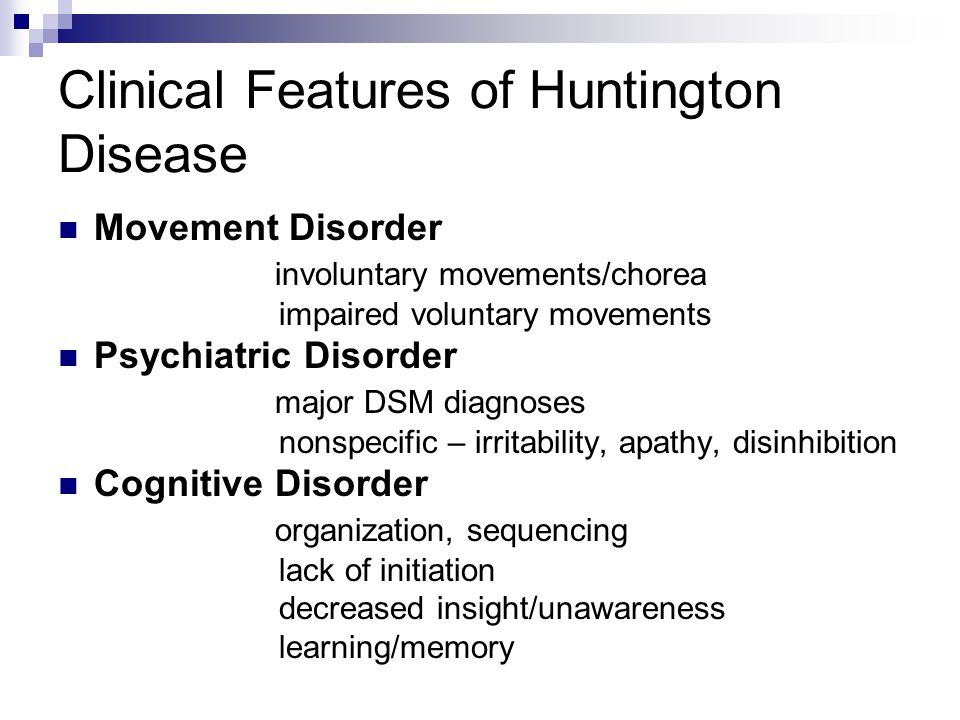

Depressive disorders are typically characterized by persistent low mood, loss of interest and enjoyment, neurovegetative disturbances, and decreased energy, causing varying levels of social and occupational dysfunction. Symptoms of depression include mood swings, anhedonia, weight changes, libido changes, sleep disturbances, psychomotor problems, loss of energy, excessive guilt, poor concentration, and suicidal thoughts. In some cases, the mood is not sad, but anxious, irritable, or indifferent.[1]American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed., (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Major depressive disorder is characterized by the presence of at least five symptoms and can be classified on a spectrum from mild to severe. Severe episodes may include psychotic symptoms such as paranoia, hallucinations, or functional maladjustment.

Subthreshold (minor) depression is characterized by the presence of two to four depressive symptoms, including depressed mood or anhedonia, lasting more than 2 weeks.

Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymic disorder) is characterized by the presence of three or four dysthymic symptoms for at least 2 years, of which symptoms were present for more than 50% of the days. Dysthymic symptoms include depressed mood, changes in appetite, disturbed sleep, decreased energy, low self-esteem, poor concentration, and feelings of hopelessness. nine0028

Age

risk factors

risk factors

risk factors

. condition after childbirth

risk factors

. condition after childbirth

More studies that are indicated first

Studies to consider

- daily free cortisol analysis

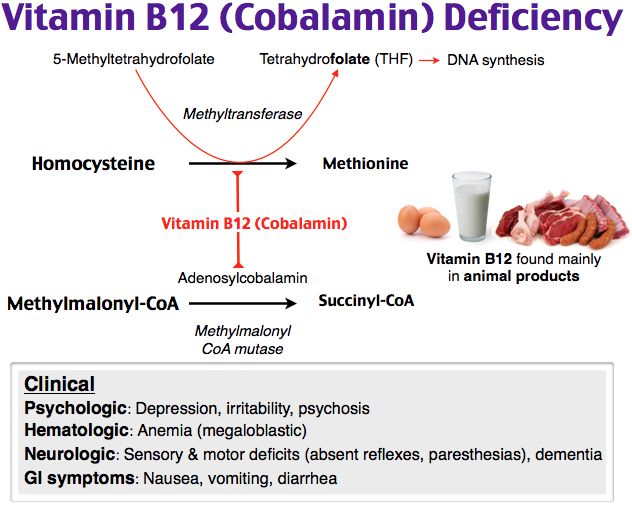

- Vitamin B12

- Folic acid

More research, which need to be considered

acute

Severe depression: psychotic, suicidal symptoms, severe psychomotor inhibitory, preventing everyday activity, catatonia or expressed excitement of 9,00022222

moderate depression, not pregnant: severe symptoms, significant deterioration, but no psychotic symptoms, no suicidal ideation, no severe psychomotor retardation or agitation. nine0015

nine0015

mild depression, not pregnant: mild to moderate symptoms, partial worsening, no psychotic symptoms, no suicidal ideation, no psychomotor retardation or agitation.

resistant/refractory depression

Pregnancy

Continuation

reacts to the treatment

Repeated episode

9000

Comples0015

Authors

DEPRESSION IS THE MAIN CAUSE OF DISABILITY IN THE WORLD

This diagnosis is often misdiagnosed. Depression is a disease that has many causes and about which we still do not know much.

Sadness, dark thoughts, low self-esteem, loss of interest or inability to enjoy... Depression is not just a blues, but a real illness. It affects all aspects of daily life and is accompanied by an increased risk of suicide. It can lead to the formation of various addictions, as well as heart disease, diabetes or sexual disorders.

nine0003

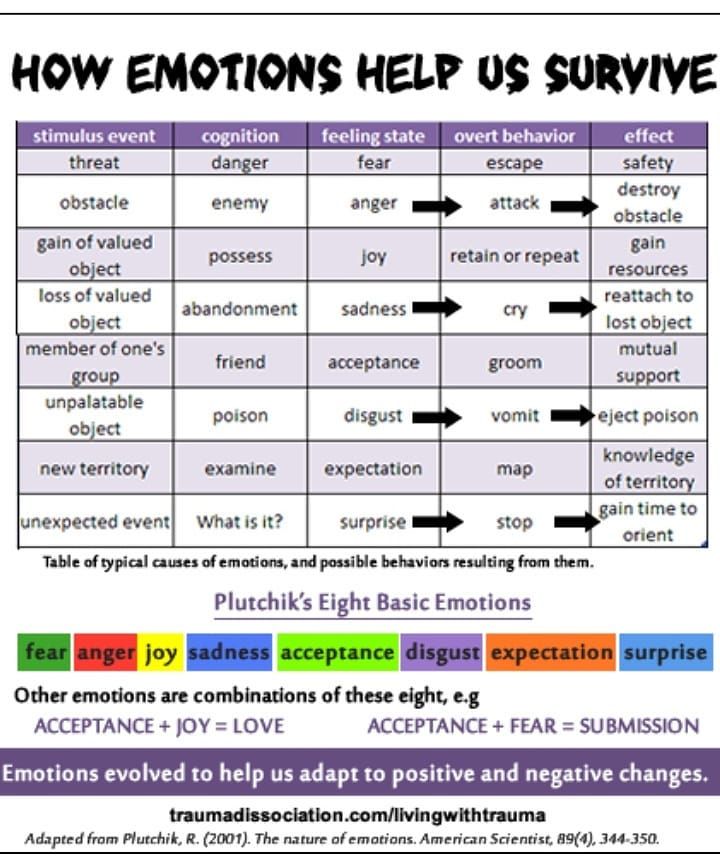

Many factors are involved in the development of depression. Vulnerability factors are at the basis, for example, if a person was a victim of abuse in childhood. The development of depression is usually preceded by the impact of so-called trigger factors. They can be a breakup in a relationship, the death of a loved one, or financial problems.

Apparently, genetic factors also play a certain role, which makes it possible to speak of hereditary predisposition. Chronic illness, smoking, dependence on alcohol or other psychoactive substances, and even an unbalanced diet can also increase the risk of depression. nine0003

322 million

people living with depression in 2017 1

+ 18.4% 2

Less than half of people with depression are treated with antidepressants. 3

GETTER UNDERSTANDING THE CAUSES OF DEPRESSION

DISTURBANCES IN THE OPERATION OF THE SYSTEM OF NEURO-MEDIATORS

In people with depression, the biochemical processes occurring in the brain are disturbed. This disorder can manifest itself as a deficiency or imbalance in the content of one or more types of neurotransmitters - molecules that are released from the terminal part of the neuron (at the synapse) and act as carriers of chemical signals in the brain. Depression disrupts the balance of three neurotransmitters: serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. They are involved in the regulation of mood and behavior, and their function can be restored with the help of antidepressants. nine0003

This disorder can manifest itself as a deficiency or imbalance in the content of one or more types of neurotransmitters - molecules that are released from the terminal part of the neuron (at the synapse) and act as carriers of chemical signals in the brain. Depression disrupts the balance of three neurotransmitters: serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. They are involved in the regulation of mood and behavior, and their function can be restored with the help of antidepressants. nine0003

SYMPTOMS

According to guidelines issued by the World Health Organization and republished by the French health authority (Haute Autorité de Santé) in October 2017, “an episode of depression is characterized by the presence of at least two of the following three main symptoms (see infographic) for two consecutive weeks with a certain degree of severity; they must be different from the patient's previous condition and cause significant distress."

nine0002 Depressive episodes usually resolve after a few weeks or months with treatment or spontaneously. This state is called remission.

This state is called remission. If subsequent episodes of depression do not recur, recovery is declared, but this rarely happens. In 50–80% of cases, a new episode occurs within the next 5 years. 6 Depression is considered chronic when certain symptoms persist, sometimes less severely, for at least 2 years. nine0003

TREATMENTS

Psychotherapy is recommended regardless of the severity of the depression.

Several types of psychotherapy are used, including supportive, cognitive-behavioral, and analytic-based psychotherapies, as well as psychotherapies based on individual, family, and group sessions.

Relatives and friends invariably play a special role in the treatment of the patient. The patient's expression of his suffering and his acceptance of help are of the utmost importance for successful treatment. nine0003

In addition to psychotherapy, the use of drugs, in particular antidepressants, is most often useful or even necessary.

Antidepressants are recommended for moderate to severe episodes of depression.

There are several classes of antidepressants. Most of them target nerve cells that release serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine. Their action is realized through various mechanisms through which the concentration of neurotransmitters increases or the nerve circuits damaged due to depression are restored. nine0003

The physician selects the antidepressant that is most appropriate for the patient, based on the patient's symptoms, medical history, past or current conditions and treatment. The effectiveness of antidepressants usually becomes noticeable only after a few weeks.

TWO PHASES OF TREATMENT (THREE IN THE EVENT OF RECURRENCE):

- The acute phase (6 to 12 weeks) is necessary to overcome the current episode of depression.

- Consolidation phase (4 to 6 months) aims to reduce the risk of disease recurrence in the short term. nine0028

- Maintenance phase: After three episodes of depression, treatment can be given for several years to prevent relapse.

In most cases, treatment is carried out on an outpatient basis (at the patient's home) under the regular supervision of a healthcare professional. However, sometimes a patient may require emergency care or an episode of depression may be resistant to conventional medications. In this case, hospitalization may be considered. nine0003

THE ROLE OF SERVIER

For over 30 years, Servier has been providing medical solutions to people who suffer from depression. Recently, the attention of our group has been focused, in particular, on the development of a digital cognitive-behavioral approach.

It combines a cognitive approach, which focuses on correcting the thoughts that keep the patient in a state of emotional decline, and a behavioral approach, which focuses on correcting inappropriate behavior. The goal of therapy is for patients to adopt a new way of thinking and develop optimal behavior. nine0003

RECURRENCE PREVENTION MEASURES

- Incorporate regular, moderate-intensity physical activity into your daily routine

Exercise (walking, running, swimming, cycling) at the recommended frequency of 30-40 minutes 5 times a week.

- Eat a balanced diet

A diet rich in fresh fruits and vegetables, fish and seafood, vegetable oils and whole grains. This type of food is high in essential fatty acids, vitamin B12, selenium, zinc, and iron, a lack of which increases the risk of depression. nine0028 - Discuss your psychological problems without delay

Talking to family, friends or a doctor can help prevent a relapse of depression. In addition, there are communities that provide the necessary assistance to those in need

(1) (2) (3) WHO Report: Depression and other common mental disorders 2017 https://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/prevalence_global_health_estimates/en/

(4) http://www.info-depression.fr/spip.php?rubrique16

(5) Léon C, Chan Chee C, du Roscoät E, the Baromètre santé 2017 survey group. La depression en France chez les 18-75 ans: résultats du Baromètre santé 2017. Bulletin épidémiologique hebdomadaire.