High functioning social anxiety

High-Functioning Social Anxiety – Bridges to Recovery

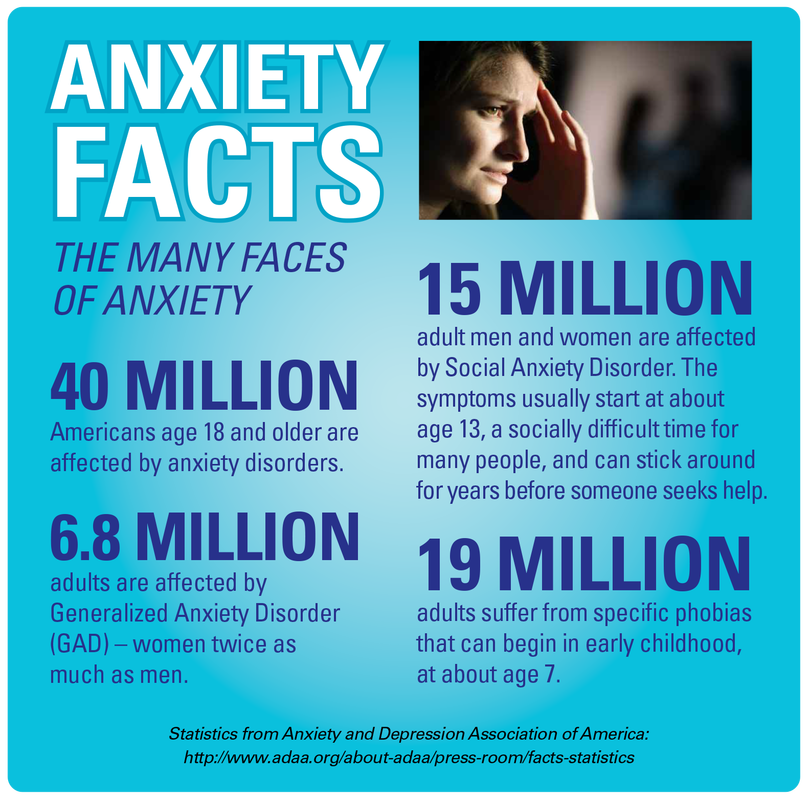

Social anxiety disorder is a mental health condition that impacts the lives of millions of Americans. After treatment and other efforts to get better many people with severe social anxiety improve dramatically, to the point where they can be classified as high-functioning. People who reach this stage—or who were always high-functioning—can form relationships, pursue careers, and make sustained efforts to fulfill their potential in all areas of life. Nevertheless, they continue to experience symptoms of anxiety that are unpleasant and life-altering, and that is why people with high-functioning social anxiety can still benefit from treatment.

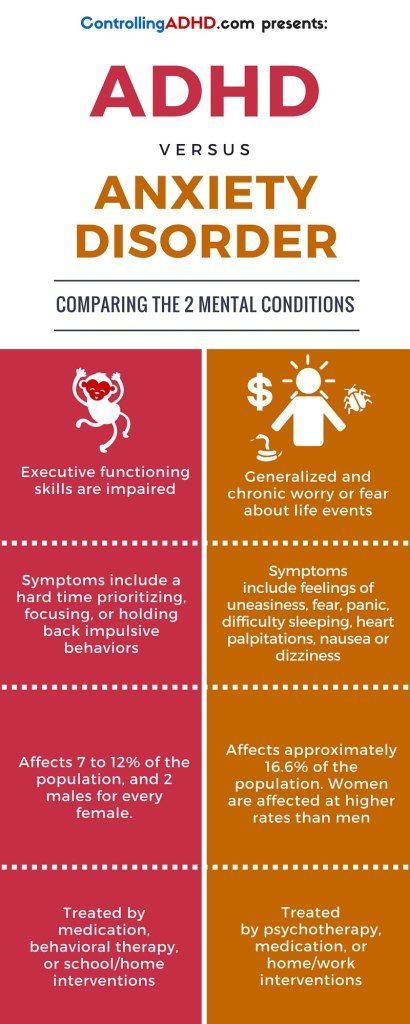

Social anxiety disorder is the second most commonly diagnosed form of anxiety disorder. Sufferers experience overwhelming feelings of nervousness and fear of rejection during most social interactions, which leads them to avoid such situations if possible.

People with full-blown social anxiety disorder can be severely limited by their social phobia, experiencing difficulties in many areas of their lives.

But chronic social anxiety is not always this disabling. Some people experience the fear and anxiety, but at a level that does not prevent them from forming relationships, holding down jobs, pursuing volunteer opportunities, making speeches, or otherwise performing or speaking in public. These individuals have high-functioning social anxiety, which is unpleasant and stressful but not paralyzing enough to keep sufferers from living a normal life.

Some people with high-functioning social anxiety have always been that way, while others experienced improvements in their anxiety symptoms and/or performance levels over time.

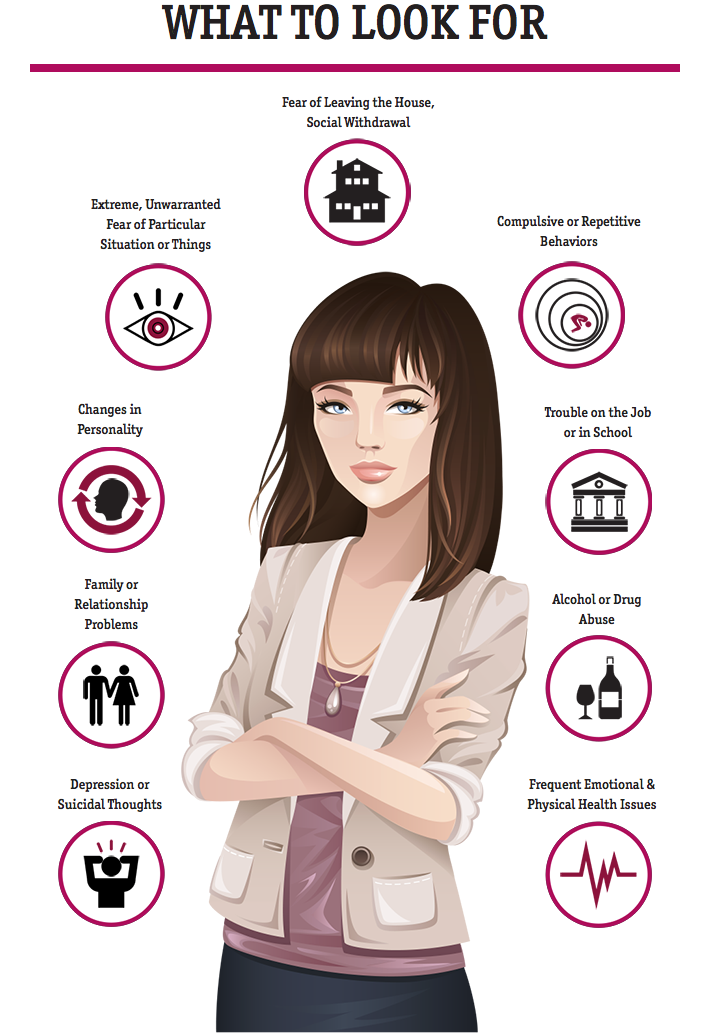

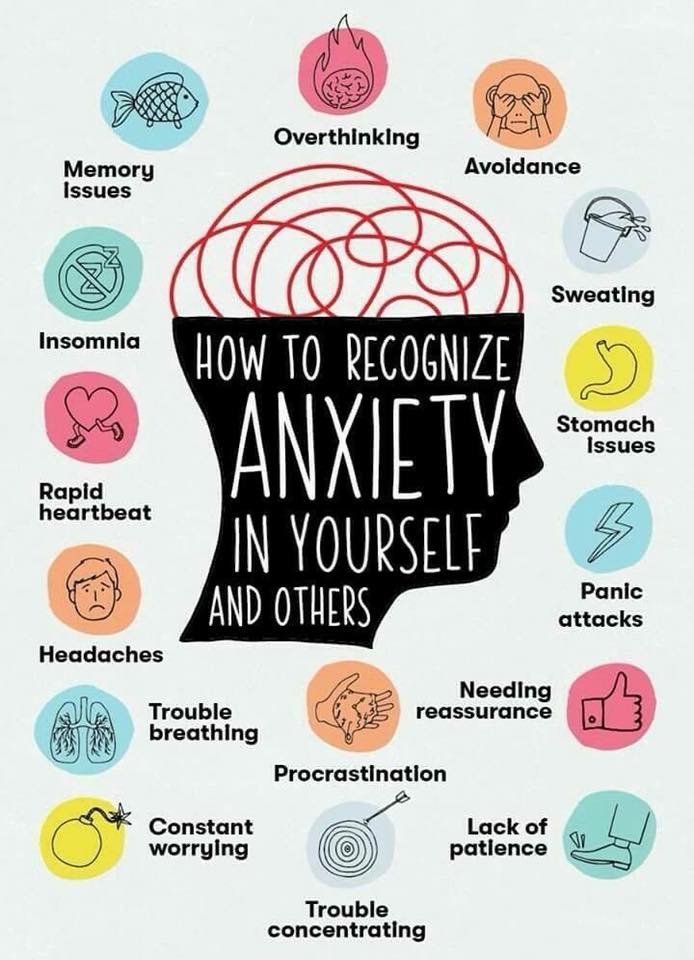

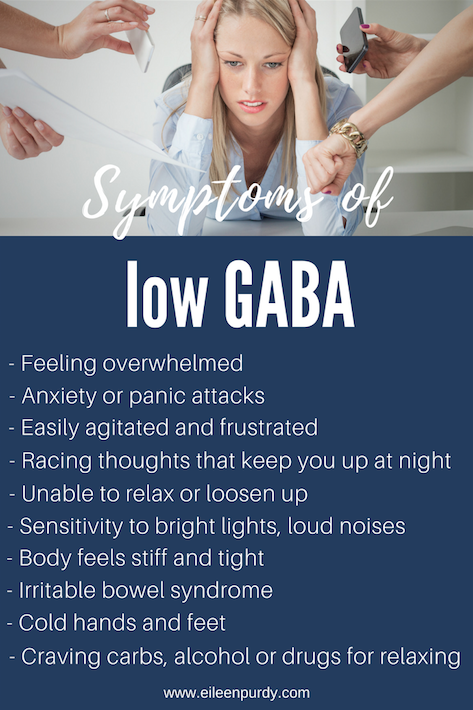

Social anxiety produces physical, psychological, emotional, and behavioral symptoms. For those with normal social anxiety disorder, all their symptoms reinforce their inability to socialize and communicate.

People with high-functioning social anxiety do experience the same physical and psychological/emotional symptoms as other social anxiety sufferers, but usually at reduced levels of intensity. And they exhibit far fewer behavioral symptoms, which is the primary reason their social anxiety carries the label high-functioning.

The physical symptoms of social anxiety include:

- Blushing

- Sweating

- Rapid heartbeat

- Lightheadedness, dizziness

- Stomach cramps or nausea

- Difficulty breathing

- Trembling

- Dry mouth

- Difficulty thinking of the right words when speaking

People with high-functioning social anxiety are familiar with each of these symptoms, although they don’t manifest as frequently or as strongly as they do in people with more serious social phobia. Nevertheless, such symptoms can be exhausting and unpleasant, and high-functioning social anxiety sufferers don’t look forward to social encounters that are likely to provoke such reactions.

Meanwhile, the psychological and emotional symptoms of social anxiety can be experienced before, during, and after social encounters. They include:

- An intense fear of rejection

- Constant fear of saying or doing something embarrassing

- Extreme discomfort around authority figures

- Reluctance to express viewpoints openly and honestly

- Obsession over worst-case scenarios and negative outcomes

- Defensiveness and paranoia when asked questions

- Fear that anxiety reactions are visible and will be noticed by others

- Assuming that others are hostile and quick to judge

- Shame over the social anxiety, or about being “different”

- Intense self-criticism and second-guessing after social encounters have ended

People with social anxiety disorder suffer from excessive and disabling self-consciousness, which can make even previously desired social interactions hard to endure. Those with high-functioning social anxiety experience many of the same thoughts and fears, but they have developed strategies to push through the fear and engage with others when necessary.

Social anxiety disorder impacts behavior as well as emotions, as sufferers often go to extreme lengths to avoid unnecessary social encounters. When interactions are unavoidable they will speak as little as possible and escape as quickly as they can, despite the shame their avoidant behavior makes them feel. They tend to prefer online interactions over using the phone or speaking to people in person, and they develop the habit of doing things alone that others do with companions.

People with high-functioning social anxiety may also avoid human contact if they judge it as non-essential. But for the most part they don’t let their social fears prevent them from doing what they really want to do. Because their avoidant behavior is more restrained and controllable they can make friends, find romantic partners, apply for jobs, ask for help in stores, or do a thousand other things those with severe social anxiety find problematic.

The amount of human contact they initiate is still somewhat limited in comparison to more outgoing people, and they still tend to be uncomfortable around strangers or casual acquaintances. But people with high-functioning social anxiety are not so quick to let opportunities for satisfying experiences pass them by, and their lives are richer and more rewarding than those of social anxiety disorder sufferers as a result.

But people with high-functioning social anxiety are not so quick to let opportunities for satisfying experiences pass them by, and their lives are richer and more rewarding than those of social anxiety disorder sufferers as a result.

Call for a Free Confidential Assessment.

877-727-4343The symptoms of some with high-functioning social anxiety were always mild or moderate. What they’ve experienced is more stressful and life-altering than normal shyness, but their social anxiety was never powerful or intimidating enough to seriously hamper their ability to build relationships or achieve their goals.

However, the situation for many high-functioning social anxiety sufferers is different. In childhood, during adolescence and into young adulthood, their social anxiety symptoms were strong and persistent, limiting their activities in many ways and inhibiting them in their search for happiness and fulfillment. Only over time were they able to get a handle on their social anxiety, learning to cope with it well enough to finally break out of their self-imposed social exile.

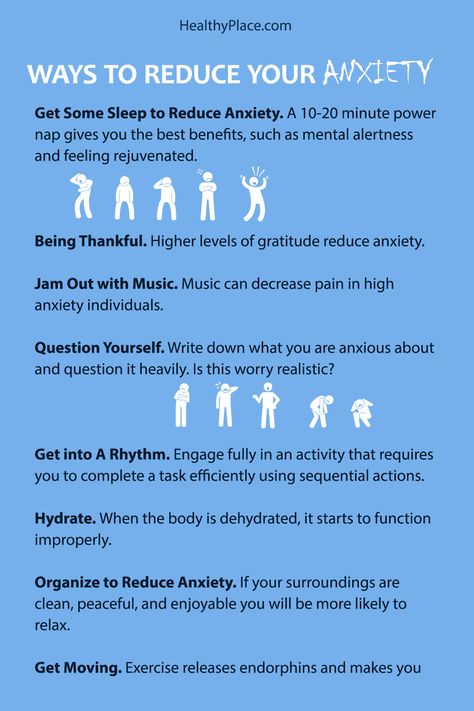

There are a number of reasons why some people overcome the worst of their social anxiety symptoms. Most men and women who recover from social anxiety disorder do so only after seeking treatment, often at a residential mental health treatment facility. With a combination of psychotherapy and medication, most social anxiety sufferers can eventually learn to manage their symptoms, which may decline in intensity if treatment continues for an extended period.

While treatment for social anxiety disorder is vitally important, there are often other factors involved that help sufferers make the transition from severe to high-functioning social anxiety. Some of these factors include:

Self-help

In addition to or in place of treatment, many social anxiety sufferers will turn to self-help books that describe techniques or strategies for overcoming their nervousness around people. They may also sign up for courses that promise to teach communication skills or methods for overcoming shyness or self-esteem problems. Online forums and social media offer still more options for self-help, for socially anxious people looking to connect with peers for advice and moral support.

Online forums and social media offer still more options for self-help, for socially anxious people looking to connect with peers for advice and moral support.

While books, classes, and online friends cannot replace organized treatment, as a supplement to it they can be quite impactful.

Mind-body healing techniques

Holistic wellness practices have grown in popularity in recent years, as word about the health-enhancing effects of yoga, meditation, massage therapy, Tai Chi, music and art therapy, hypnosis, biofeedback, and other mind-body healing techniques has spread. Many residential mental health treatment centers now offer holistic healing practices as a part of their recovery programs, which is a testament to how well they work both inside and outside of rehab.

For social anxiety sufferers, and those who experience anxiety in general, holistic mind-body practices can help relieve stress and assist in the ongoing process of retraining the brain to react with less fear and paranoia during social interactions.

Declines in intensity related to aging

One long-term study of social anxiety disorder sufferers found that 37 percent showed significant improvement in their symptoms over a 12-year period, despite not receiving any treatment.

However, the average survey participant had already experienced social anxiety for 19 years at the beginning of the experiment, so these statistics don’t suggest much hope of spontaneous improvement for younger social anxiety sufferers. Also, the 37-percent improvement rate was markedly lower than the recovery rates for generalized anxiety disorder (58 percent) and panic disorder (82 percent). So age-related improvements aside, treatment remains critically important for most people suffering the symptoms of severe social anxiety.

The need to take care of life’s necessities

Regardless of the severity of their initial social phobia symptoms, most social anxiety sufferers still must fulfill certain life responsibilities in order to survive. This could mean enrolling in college, meeting all academic requirements on chosen career tracts, interviewing for jobs, and performing all workplace duties and assignments necessary to do a job correctly once it has been secured. Interpersonal imperatives also cause many social anxiety disorders sufferers to reach out to others for love or friendship, and that is now easier to do through various online venues.

This could mean enrolling in college, meeting all academic requirements on chosen career tracts, interviewing for jobs, and performing all workplace duties and assignments necessary to do a job correctly once it has been secured. Interpersonal imperatives also cause many social anxiety disorders sufferers to reach out to others for love or friendship, and that is now easier to do through various online venues.

The strength of their social anxiety symptoms notwithstanding, most social anxiety disorder sufferers will eventually reach out to, connect with, or be forced to interact with other people, and as they gain more experience interacting with others their social skills and comfort level are bound to improve to a degree.

People with high-functioning social anxiety are relatively privileged in comparison to those with social anxiety disorder. But they often earned their high-functioning status through hard work, dedicated effort, and an ongoing commitment to treatment, which is an avenue for recovery potentially open to all.

As a starting point, inpatient social anxiety treatment programs in a residential mental health facility gives social anxiety disorder sufferers the best chance for eventual recovery. But inpatient treatment also has much to recommend it for those who’ve been high-functioning for many years, who often suffer in silence despite outward appearances.

With intensive, round-the-clock treatment services in a fully supportive healing environment, men and women with high-functioning social anxiety can find further relief from their most persistent symptoms, which may remain unpleasant, stress-inducing, and limiting in many ways despite not being fully debilitating.

While there is no cure for social anxiety, when its symptoms are present there is always room for improvement, even if those symptoms haven’t been a substantial barrier to achievement. Mild-to-moderate social anxiety is still social anxiety, and inpatient and outpatient treatment programs are still appropriate and usually highly effective for those who experience social anxiety in any form or at any level of intensity.

What Is It Like To Have High-Functioning Anxiety? – Bridges to Recovery

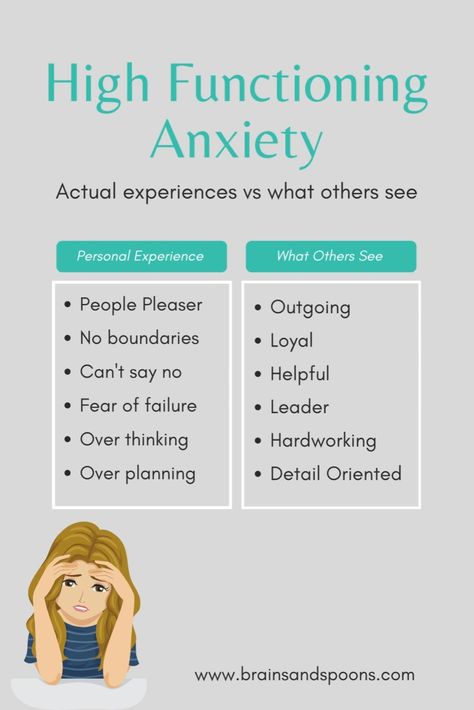

High-functioning anxiety can be difficult to manage. While a person may look fine on the outside, he or she may be struggling inside just to make it through the day. People with high-functioning anxiety are often able to accomplish tasks and appear to function well in social situations, but internally they are feeling all the same symptoms of anxiety disorder, including intense feelings of impending doom, fear, anxiety, rapid heart rate, and gastrointestinal distress. People who suffer from high-functioning anxiety generally do not avoid situations that can trigger anxiety, and do not appear to experience an obvious disruption or impairment in their daily living functions.

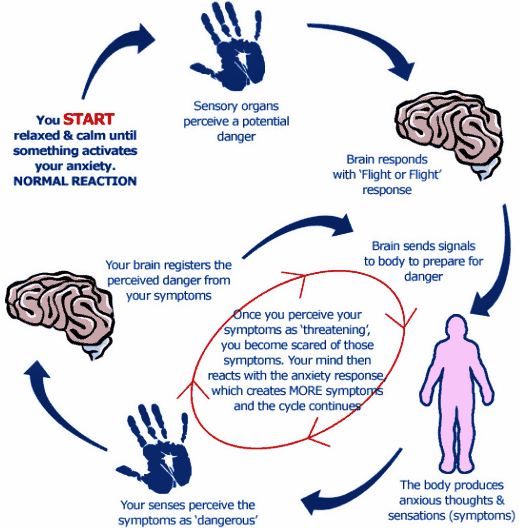

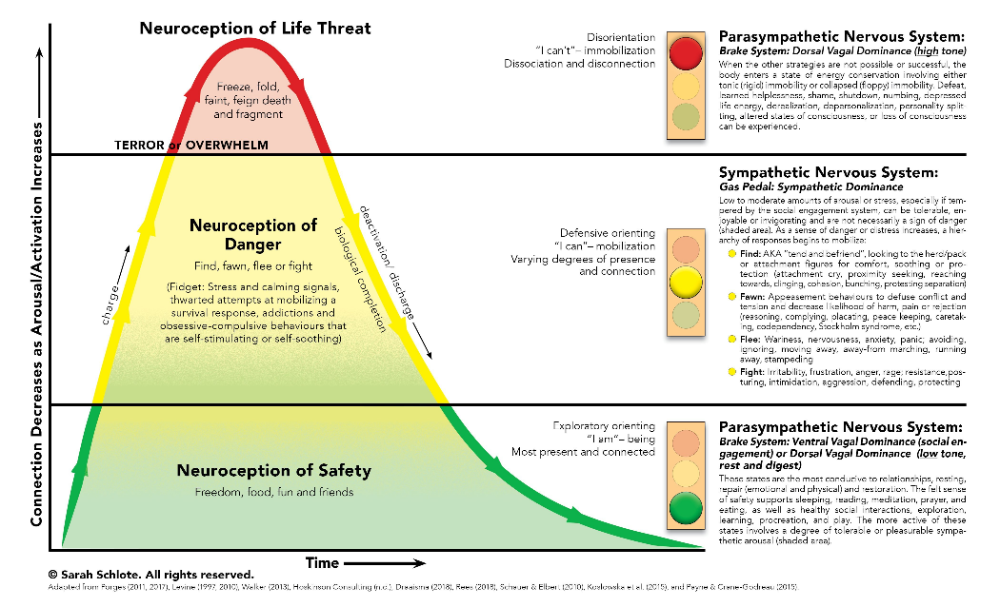

Anxiety is a natural and healthy emotion most everyone experiences. It is a vital feeling, because it alerts people to pay attention to important issues or warns of potential danger. But, with anxiety disorder, the fear response becomes exaggerated, and a person becomes anxious and fearful in situations that do not call for it. The fear and anxiety can become so great, steps are taken to avoid situations that trigger the feeling. Additionally, worrying about anxiety and the situations that cause the anxiety can result in further anxiety.

It is a vital feeling, because it alerts people to pay attention to important issues or warns of potential danger. But, with anxiety disorder, the fear response becomes exaggerated, and a person becomes anxious and fearful in situations that do not call for it. The fear and anxiety can become so great, steps are taken to avoid situations that trigger the feeling. Additionally, worrying about anxiety and the situations that cause the anxiety can result in further anxiety.

Common symptoms of anxiety disorder include rapid heart rate, sweating, lightheadedness or feeling faint, inability to concentrate or a feeling of “losing it,” trouble breathing, sleep disruptions, nausea, and an intense feeling of dread.

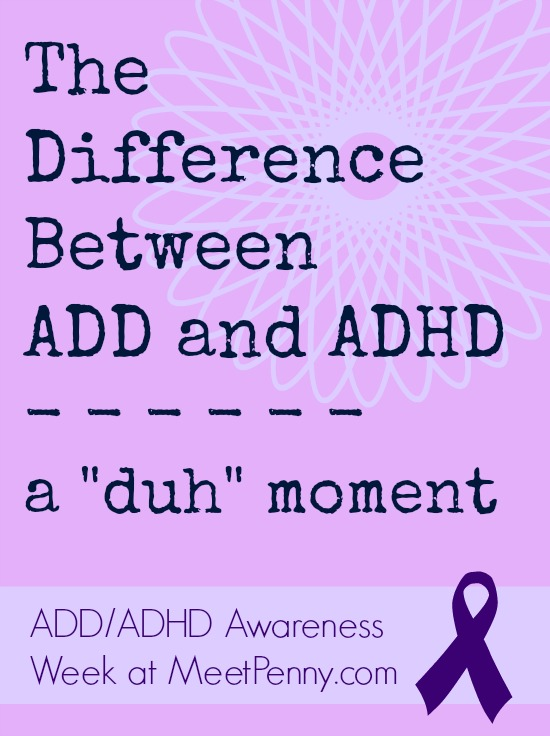

Is High-Functioning Anxiety An Official Diagnosis?

High-functioning anxiety is not an official diagnosis and is not listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the prevailing guidelines for mental health diagnoses. According to the DSM-5, a required element of anxiety disorder is the anxiety must cause a disruption or impairment of life activities, and a change in behavior to avoid situations that trigger anxiety. Since disruption or impairment of life functions is a required element, there is an argument that if no clear impairment exists then anxiety disorder is not present. But many mental health professionals recognize that when a person suffers from anxiety disorder, they may experience varying degrees of impairment. Thus, when the impairment appears mild, it is simply characterized as anxiety disorder with mild impairment, rather than absent impairment. The prevailing thought is that this condition is mild anxiety, rather than high-functioning anxiety.

According to the DSM-5, a required element of anxiety disorder is the anxiety must cause a disruption or impairment of life activities, and a change in behavior to avoid situations that trigger anxiety. Since disruption or impairment of life functions is a required element, there is an argument that if no clear impairment exists then anxiety disorder is not present. But many mental health professionals recognize that when a person suffers from anxiety disorder, they may experience varying degrees of impairment. Thus, when the impairment appears mild, it is simply characterized as anxiety disorder with mild impairment, rather than absent impairment. The prevailing thought is that this condition is mild anxiety, rather than high-functioning anxiety.

With mild anxiety, the individual experiences minor life impairment and is often characterized as having mild symptoms rather than being “high-functioning.” However, this reasoning does not address the conflict between how an individual feels internally, and how he or she displays those feelings externally. In other words, while the resultant impairment—the external manifestation of anxiety—might be mild, the way the person feels inside—the internal manifestation of anxiety—might be extremely high. The notion of high-functioning anxiety comes from this conflict between the intense internal feelings and the ability to function despite those feelings. The argument is not that the symptoms are mild, but that the individual suffering from high-functioning anxiety may be better able to manage how extreme symptoms appear to affect him or her, even though he or she is suffering silently.

In other words, while the resultant impairment—the external manifestation of anxiety—might be mild, the way the person feels inside—the internal manifestation of anxiety—might be extremely high. The notion of high-functioning anxiety comes from this conflict between the intense internal feelings and the ability to function despite those feelings. The argument is not that the symptoms are mild, but that the individual suffering from high-functioning anxiety may be better able to manage how extreme symptoms appear to affect him or her, even though he or she is suffering silently.

Though high-functioning anxiety may not be officially listed as a mental health disorder, it does not mean that people who suffer from high-functioning anxiety do not experience intense symptoms. They may just be able to hide them well.

Call for a Free Confidential Assessment.

877-727-4343Our Caring Staff is Here to Help

877-727-4343

What Does It Mean To Be High-Functioning?

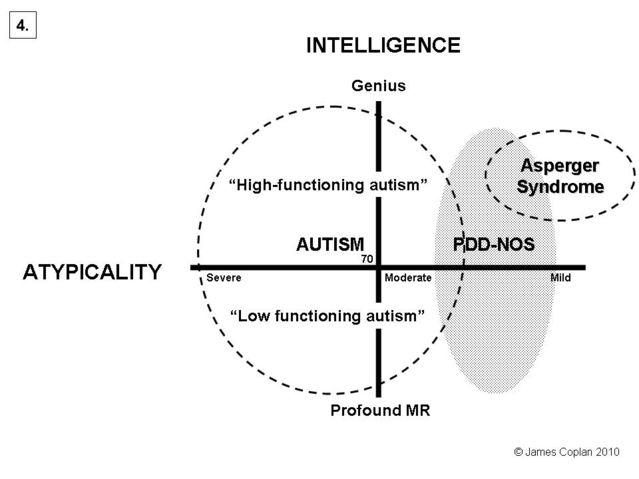

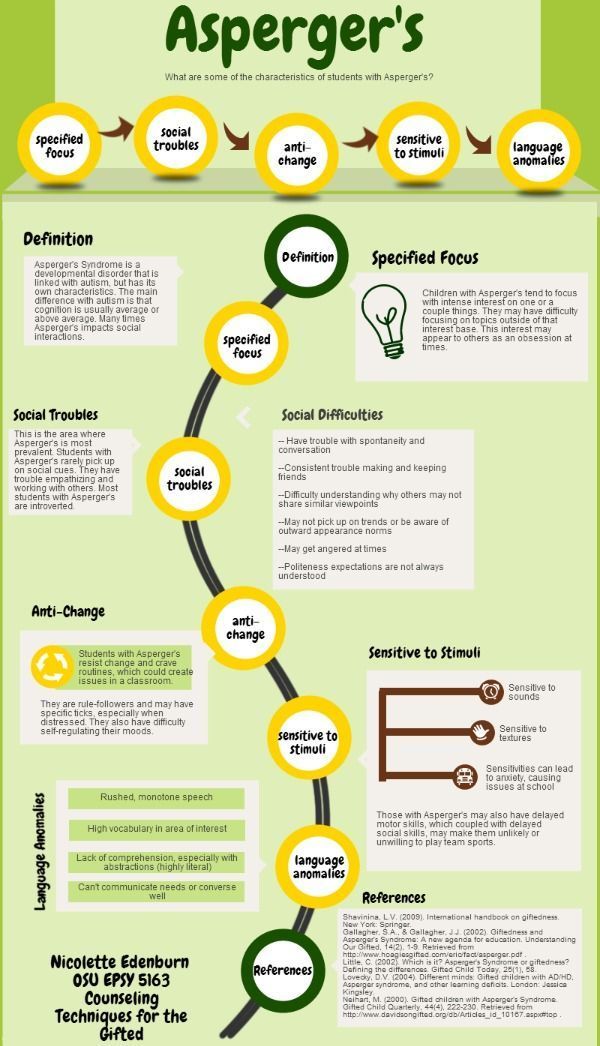

The term “high-functioning” generally means a person is operating at an elevated level, usually one that is above average functioning of others under the same or similar circumstances. The term is often used in relationship to developmental disorders, but it has often been used in relationship to mental health disorders to signify that a person is operating above whatever threshold is considered the norm.

The term is often used in relationship to developmental disorders, but it has often been used in relationship to mental health disorders to signify that a person is operating above whatever threshold is considered the norm.

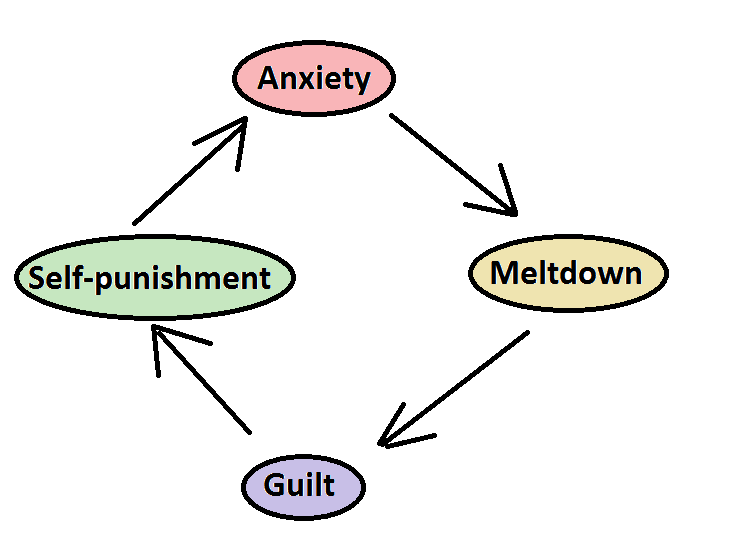

With regard to anxiety disorder, the term high functioning has been the subject of much debate. While not an official diagnosis, the symptoms one feels are very real. But because people who suffer from high functioning anxiety appear not to have any disruptions or impairments of life functions, many people do not know anything is wrong, not even the person who is experiencing the anxiety. A person might look fine, even though his or her heart rate might be elevated, and intense feelings of doom and gastrointestinal distress are present. However, the ability to “power through to get the job done” is also high enough to overcome the anxiety while in public. Some of the same people later “crash” when in private. The exercise of controlling intense emotions can take a toll and require time alone, or periods of very low functioning in order to regroup. Other medical and mental health issues can develop under these circumstances.

Other medical and mental health issues can develop under these circumstances.

Mental health professionals are beginning to acknowledge that difficulty functioning is not always easy to identify. For instance, David Roane, MD, chairman of psychiatry at New York’s Lenox Hill Hospital, maintains, “Sometimes you have to dig pretty hard to see how the anxiety is affecting life or work.” Although one may not be exhibiting significant life impairment, the struggle to control anxiety and perform can affect the overall quality of life. The question becomes whether one is thriving or just surviving.

Because a person is high functioning, they likely are not getting treatment. And without treatment, symptoms often only get worse. By the time someone with high function in anxiety meets the requirements for an official diagnosis, the issue has gone on far too long without treatment.

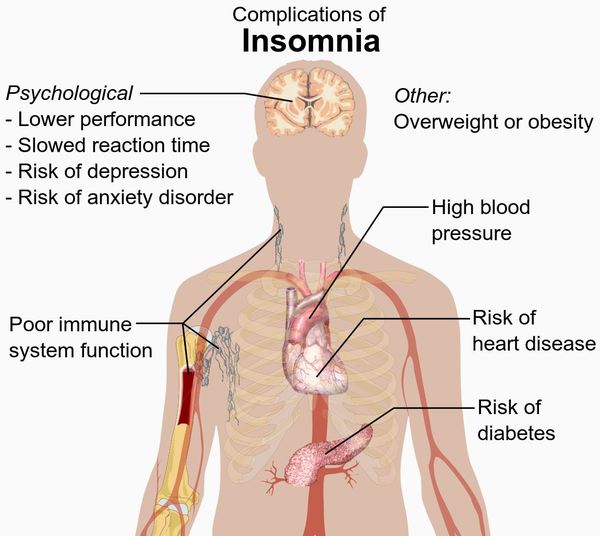

Hidden Dangers Of High Functioning Anxiety

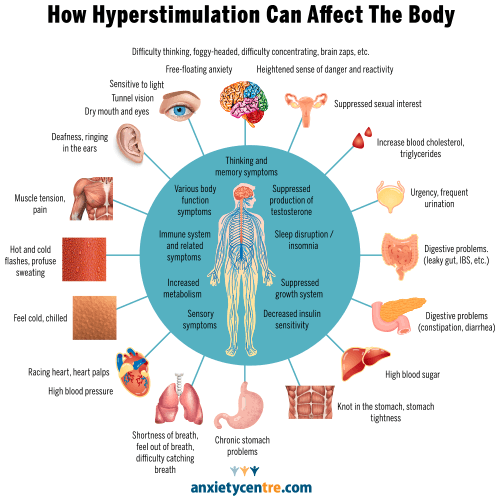

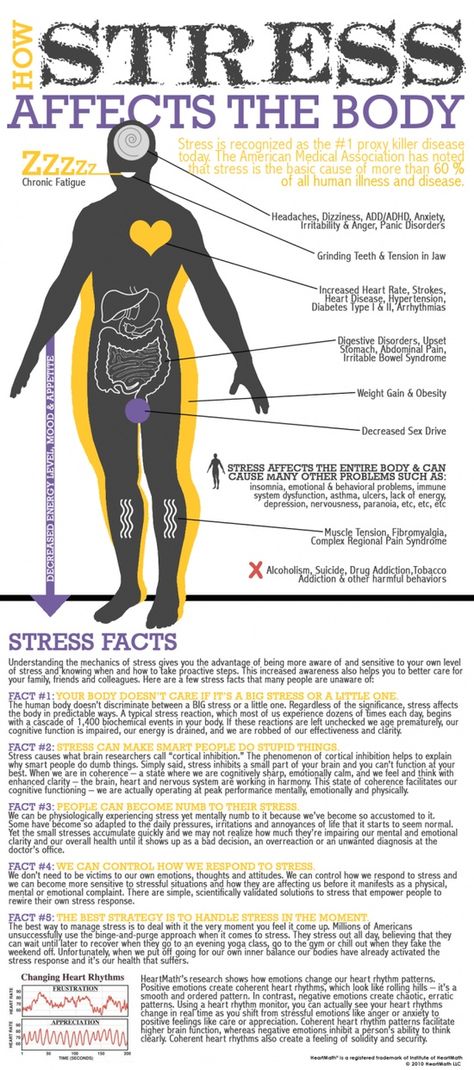

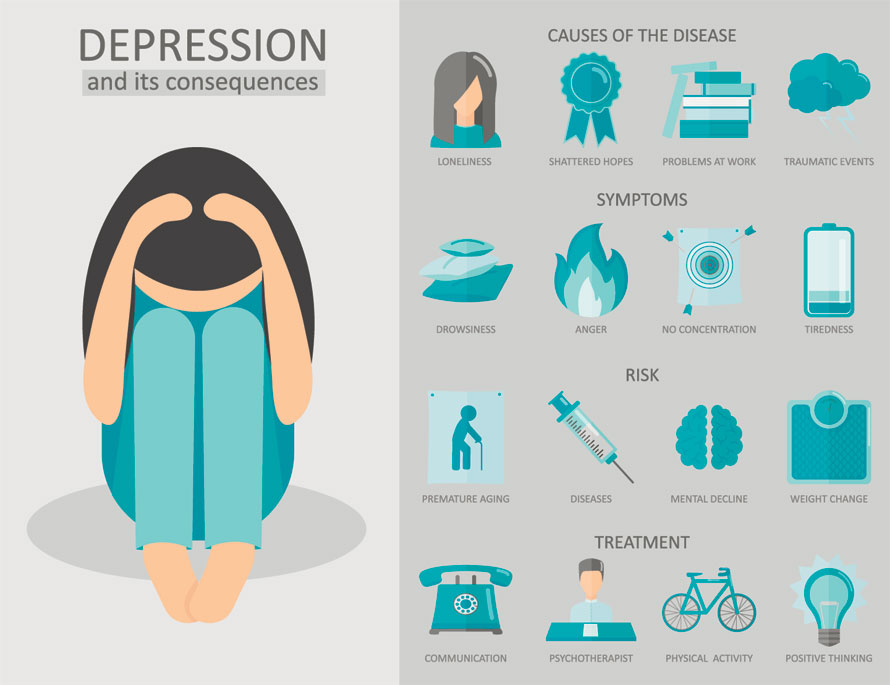

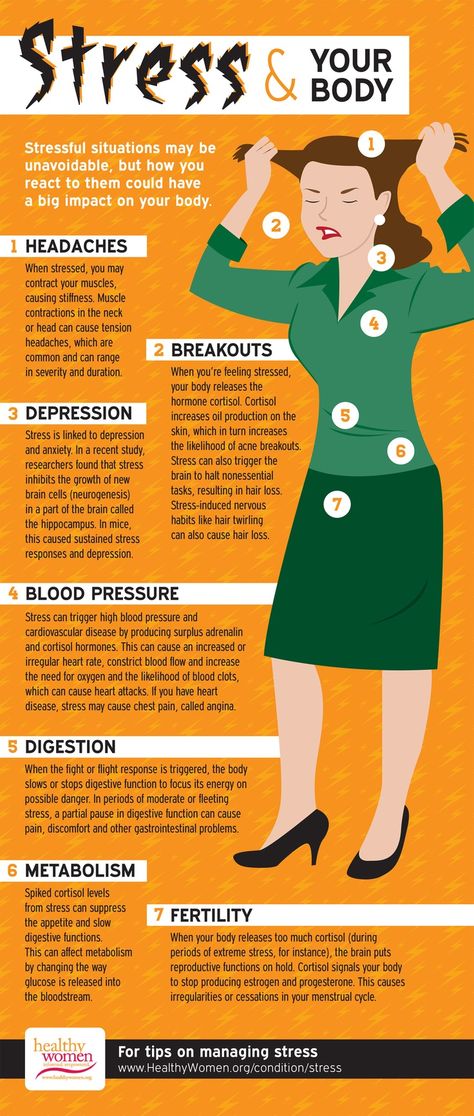

When anxiety goes untreated, the potential for developing other serious medical or mental health issues increases. Research shows anxiety affects cognition, specifically memory, the ability to reason, and make basic decisions. Additionally, when people with certain chronic medical issues also have untreated anxiety, the risk the medical issue will worsen or cause death also increases. The stress of anxiety on the body can be significant, especially when left unchecked for a prolonged period.

Research shows anxiety affects cognition, specifically memory, the ability to reason, and make basic decisions. Additionally, when people with certain chronic medical issues also have untreated anxiety, the risk the medical issue will worsen or cause death also increases. The stress of anxiety on the body can be significant, especially when left unchecked for a prolonged period.

Common medical problems that can occur as a result of untreated anxiety include:

- Heart Issues—Several studies have shown a causal link between anxiety, heart disease, and related health problems. In one study, risk of heart attack or stroke tripled in men and women who had heart disease, and was twice as likely to occur than if no history of anxiety disorder was present. Another study showed women with high levels of anxiety were 59 percent more likely to have a heart attack and 31 percent were more likely to die from a heart attack.

- Respiratory Issues—Difficulty breathing is a common symptom of anxiety.

The inability to breathe places stress on other body functions as each requires oxygen to function properly. Decreases in oxygen intake can interfere with cognition, muscle operation, and other body functions. Chronic respiratory problems have also been linked to anxiety disorder. Several studies have identified a correlation between a more severe level of distress and hospitalizations of people who have chronic respiratory disease and anxiety. Anxiety is indicated in a reduction of overall quality of life when coupled with respiratory issues.

The inability to breathe places stress on other body functions as each requires oxygen to function properly. Decreases in oxygen intake can interfere with cognition, muscle operation, and other body functions. Chronic respiratory problems have also been linked to anxiety disorder. Several studies have identified a correlation between a more severe level of distress and hospitalizations of people who have chronic respiratory disease and anxiety. Anxiety is indicated in a reduction of overall quality of life when coupled with respiratory issues. - Gastrointestinal Issues—One of the main symptoms of anxiety is gastrointestinal distress, such as upset stomach or nausea. When anxiety goes untreated, gastrointestinal distress can become worse. Though there is little research to link the development of gastrointestinal issues with anxiety, anxiety disorder treatments have been linked to a decrease in symptoms of gastrointestinal distress.

People who suffer from untreated high functioning anxiety also are at greater risk for developing a substance abuse problem. Many people with untreated mental health disorders look to self-medication through alcohol and drugs. Anxiety disorders have a high co-occurrence rate with substance abuse issues.

Many people with untreated mental health disorders look to self-medication through alcohol and drugs. Anxiety disorders have a high co-occurrence rate with substance abuse issues.

It is important to seek treatment for high functioning anxiety to help prevent the development or worsening of other medical, mental health, or substance abuse issues.

Begin Your Recovery Journey.

877-727-4343Begin Your Recovery Journey Today

How We Treat Anxiety

Why Consider Residential Treatment?

Treatment for high functioning anxiety is like other anxiety treatments. A combination of psychotherapy and medication tends to show increased positive outcomes.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is designed to help people deal with negative thoughts that lead to anxiety. Even though a person suffering from high functioning anxiety may not show outward signs of the issue, they are still struggling with internal negative thoughts and feelings. CBT can help identify the root causes of negative thoughts and feelings, and how to control or eliminate them. Alleviating the internal struggle may improve overall quality of life and allow a person who suffers from high functioning anxiety to thrive, rather than just survive.

CBT can help identify the root causes of negative thoughts and feelings, and how to control or eliminate them. Alleviating the internal struggle may improve overall quality of life and allow a person who suffers from high functioning anxiety to thrive, rather than just survive.

Medication can also be beneficial treating high functioning anxiety. Usually, antidepressants—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), anti-anxiety medications—benzodiazepines, and beta blockers are prescribed to decrease anxiety symptoms. SSRIs take a few weeks to begin working and carry some side effects. Benzodiazepines work faster and have few side effects but can be habit forming. Beta blockers are generally prescribed to reduce heart-related issues connected to anxiety.

Most people who suffer from anxiety disorders do not get treatment. The number is even higher for people with high functioning anxiety disorder, partly because it is not readily diagnosed, but more often because most people do not realize anything is wrong. Observers do not see any unusual behavior and sufferers are often used to dealing with the anxiety as “normal.”

Observers do not see any unusual behavior and sufferers are often used to dealing with the anxiety as “normal.”

Combining residential treatment with therapy and medication can further improve positive outcomes for controlling high functioning anxiety disorder. Residential treatment centers are live-in health care facilities that offer individualized treatment in a home-like setting, 24 hours a day, away from external stressors at home or work.

Residential treatment for high-functioning anxiety provides a safe and controlled environment that allows individuals to remove themselves from anxiety-causing situations that feel normal, and begin to learn how to function those situation in a healthier way. Typical periods of stay in residential treatment is 30-60 days or more.

High anxiety among young people: causes and ways to overcome

References:

Afonina, S. A. High anxiety among young people: causes and ways to overcome / S. A. Afonina, G. A. Karakyan. - Text: direct // Young scientist. - 2021. - No. 15 (357). — S. 291-293. — URL: https://moluch.ru/archive/357/79857/ (date of access: 12/13/2022).

A. Afonina, G. A. Karakyan. - Text: direct // Young scientist. - 2021. - No. 15 (357). — S. 291-293. — URL: https://moluch.ru/archive/357/79857/ (date of access: 12/13/2022).

The article deals with the concept of youth and youth as an age period, as well as issues related to the increased level of anxiety of today's youth, recommendations are given to combat high anxiety. The relevance of the topic of the work is due to the high level of personal anxiety of young people and the need for psychological and pedagogical work with young people.

Keywords: youth, youth, living conditions, stress, anxiety, anxiety, influence, social work.

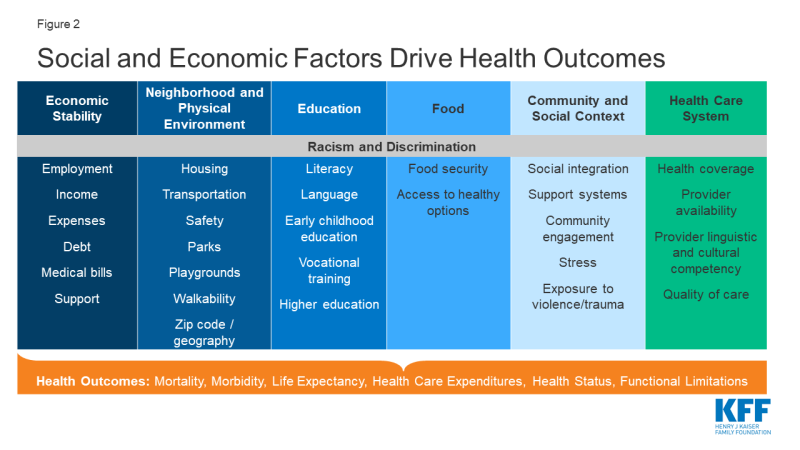

Modern life, due to the influence of rapidly changing social, economic and technological conditions, places high demands on the ability of a person to adapt. Today, not only the inhabitants of our country, but also the majority of the world's population, to one degree or another, is experiencing stress and anxiety. This was influenced by wars, and all kinds of rallies, protests, and the economic crisis, and of course quarantine and self-isolation in a pandemic. All this affects one of the main human needs - the need for security, which in turn has a huge impact on the psychological state of a person, causing stress and anxiety.

This was influenced by wars, and all kinds of rallies, protests, and the economic crisis, and of course quarantine and self-isolation in a pandemic. All this affects one of the main human needs - the need for security, which in turn has a huge impact on the psychological state of a person, causing stress and anxiety.

As for young people, their high expectations of life, their violent reaction to any failures and lack of experience, anxiety about not having their own home and good jobs, and for many, in addition, the need to adhere to the austerity regime are the reasons why today's young people are very anxious, it is difficult for them to adapt to difficult situations.

The most complete definition of youth was given by I. S. Kohn: “Youth is a socio-demographic group, singled out on the basis of a combination of age characteristics, social status, due to both socio-psychological properties.” At this age, some of the most significant events take place: the creation of a family and the arrangement of family life, mastering the chosen profession, establishing an attitude to public life and one's role in it. This is the most favorable time for self-realization. Young people master the norms of relations between people (business, personal, etc.), as well as professional and labor skills.

This is the most favorable time for self-realization. Young people master the norms of relations between people (business, personal, etc.), as well as professional and labor skills.

But despite the above, we can note the high anxiety of young people. According to the results of a study conducted on the basis of the Moscow State Pedagogical University, using the methodology of Ch. D. Spielberg "The scale for assessing the level of reactive and personal anxiety", it was revealed that the level of personal anxiety of young people was in most cases high. The sample consisted of 58 people aged 20 to 30. . (Fig. 1)

Personal anxiety - in 58.5% of the subjects at a high level, in 38% - at a moderate level, and only 3.5% - at a low level.

Rice. 1. The level of personal anxiety of young people

High anxiety in youth may be associated with changes in the social and economic conditions of life, and with a huge mental and neuro-emotional load associated with a constant increase in the amount of information and lack of time for proper sleep due to study or work, unresolved issues related to the beginning independent life, well-established life, dissatisfaction of needs, etc.

Surely you have heard the concepts of anxiety and anxiety. If you often feel psychological discomfort, uncertainty about the future and your strengths, mood swings, anxiety, then you are probably faced with anxiety. But without correction of the condition, it can turn into anxiety. "What is the difference?" - you ask.

Anxiety - stable quality of personality, while anxiety — temporary state (emotion). If it’s normal to experience anxiety sometimes, then anxiety needs to be dealt with.

Increased anxiety is a mental state caused by imaginary or real situations, a reaction to fear, whether it is real or imagined. This condition may be accompanied by increased concentration of attention and excessive motor activity, but still the manifestations are individual.

It should be noted that there is a concept of useful anxiety. This is her level necessary for the development of personality. Normal and useful anxiety arises in response to a real threat, is not a form of suppression of internal conflict, does not cause a defense reaction, and can be eliminated by an arbitrary change in the situation or by one's attitude towards it.

Normal and useful anxiety arises in response to a real threat, is not a form of suppression of internal conflict, does not cause a defense reaction, and can be eliminated by an arbitrary change in the situation or by one's attitude towards it.

A high level of anxiety can also have an extremely adverse effect on the quality of social life as a whole, both for an individual and for society as a whole. Therefore, social work with young people is needed to help young people overcome the problem.

We have given some recommendations to young people in the fight against high anxiety:

- First you need to determine the cause of the alarm. Remember, without knowing the cause, you should not fight the effect.

- You should learn to relieve stress - instantly relax. To do this, it is worth mastering the skills of auto-training, which can be found in numerous manuals.

- Give your nervous system a rest.

Remember: only those who have a good rest work well. The best rest for the nervous system is sleep, including short-term daytime sleep (from 5 to 30 minutes). Ideally, at the end of each hour of work, you should rest for 2-5 minutes.

Remember: only those who have a good rest work well. The best rest for the nervous system is sleep, including short-term daytime sleep (from 5 to 30 minutes). Ideally, at the end of each hour of work, you should rest for 2-5 minutes. - Change of life situation. If anxious experiences are associated with any particular area - work, marital status, circle of friends, try to change something in this particular part of your life. Start small, you don't have to quit your job or divorce your spouse right away. Think about what changes are available to you that will bring comfort and more satisfaction, put them into practice.

- Communicate with loved ones. The presence of a wide circle of communication and close social ties in a person significantly reduces the level of anxiety.

- Go in for sports. Regular training has a beneficial effect on the human body, helps to throw out the accumulated stress, switch to a positive way.

- Try ways of self-regulation, such as: switching, distraction or deemphasis, etc.

- Try drawing your worries. Look at them from afar. Ask yourself questions: “When does it appear? What for? What qualities of yours make her stronger, and what vice versa?

- Accept that you cannot control everything. Put your anxiety in perspective - is it really as bad as you think?

- One of the main weapons in the fight against anxiety is self-awareness. Thus, to get rid of anxiety, work on yourself, on your worldview, paint your life plans (for a month, a year, five years, ten). Do not think whether it will work or not, what will happen. Just act, being confident in your strengths and capabilities.

In conclusion, it is worth saying that the main principle of anxiety is: the more you worry, the more the quality of activity suffers. And that makes the anxiety even worse. Yes, this is a vicious circle and it literally needs to be broken.

Note that it is sometimes possible to reduce anxiety on your own, but most often, only a specialist can help to effectively and for a long time correct a high level of anxiety. If anxiety interferes with life and is accompanied by obsessive thoughts, such as suicide, vivid physiological symptoms such as severe fatigue, nausea that do not go away for a long time, and behavior patterns such as avoidance (you panic in public), you should definitely seek help from a specialist. .

If anxiety interferes with life and is accompanied by obsessive thoughts, such as suicide, vivid physiological symptoms such as severe fatigue, nausea that do not go away for a long time, and behavior patterns such as avoidance (you panic in public), you should definitely seek help from a specialist. .

So, reducing the level of anxiety is one of the urgent tasks of psychology and social pedagogy. It confronts researchers with the need for the most complete and multidimensional study of this area and the application of the data obtained in practice.

Literature:

- Ananiev BG Selected works on psychology. In two volumes. Volume 1 Publisher: St. Petersburg University, 2007

- Arakelov N., Shishkova N. “Anxiety: methods of its diagnosis and correction” / Vestnik MU, ser. Psychology. - 1998, no. 1.

- Astapov V. M. Functional approach to the study of the state of anxiety - Psychological Journal, 1992, No. 5, p. I1–120.

- Kon I. S. In search of oneself: Personality and its self-consciousness - M .: Politizdat, 1987. - 366 p.

- Rubinshtein, S. L. Fundamentals of General Psychology [Text]. — M.: SPb.: ELBI, 2008. — 632 p.

Basic terms (automatically generated) : high anxiety, youth personal anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, high anxiety, personality anxiety, young, nervous system, useful anxiety, social work.

Early childhood temperament and development of anxiety and depression

Nathan A. Fox, PhD, Tahl I. Frenkel, MA

University of Maryland, USA

(English). Translation: June 2015

Introduction

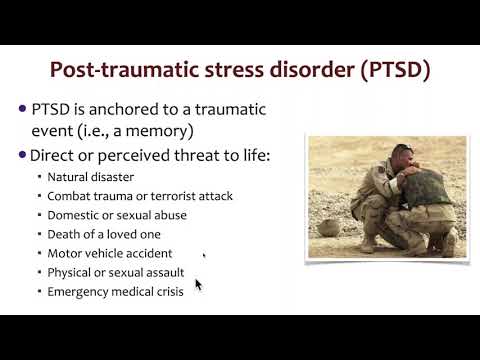

Anxiety disorders in general, and social anxiety disorder (social anxiety disorder, SAD), in particular, cause severe distress and increase the risk of long-term adverse effects. Most anxiety disorders in adults begin in childhood or adolescence at an extremely steady rate of 5 to 10 percent; and the level of social phobia varies from 1.6% to 8.5%. 2-4 Longitudinal studies show that the temperamental trait of behavioral inhibition appears to be the most likely predictor of the risk of developing anxiety later on. 5-6

Most anxiety disorders in adults begin in childhood or adolescence at an extremely steady rate of 5 to 10 percent; and the level of social phobia varies from 1.6% to 8.5%. 2-4 Longitudinal studies show that the temperamental trait of behavioral inhibition appears to be the most likely predictor of the risk of developing anxiety later on. 5-6

The purpose of this chapter is to explore in general terms the relationship between this temperament and the occurrence of anxiety disorders. We will review research on two cognitive processes, attention and executive processes, that contribute to anxiety disorders among children with behavioral inhibition. Finally, in line with recent evidence that behavioral inhibition may represent not only a specific temperamental predisposition to anxiety, but also a more general risk factor for internalizing disorders, 7 we will review the existing (still limited) literature linking early temperament with the subsequent development of depression.

Item

Behavioral inhibition is a type of temperament that can be identified in infancy and early childhood. Infants with this temperament show increased irritability and motor reactivity to unusual stimuli. During their early preschool years, they avoid social contact and tend to withdraw in unfamiliar social situations, which makes them less self-confident5,6 and more susceptible to peer rejection, 8.9 what is negative self-perception connected with. 10 In general, inhibited children have fewer friends, 11 they are more likely to show increased anxiety and feel lonely. 12

Anxiety risk studies focus on early temperamental traits, especially behavioral inhibition. 10,13,14 For example, Schwartz et al6 found that 61% of thirteen-year-olds who were noted to show signs of behavioral inhibition at age two showed clear signs of anxiety during social interaction, compared with only 27% of those who showed no inhibition. Similarly, Chronis-Tuscano et al. 15 found a four-fold increased likelihood of a lifetime diagnosis of social anxiety disorder among adolescents with consistently high levels of behavioral inhibition between the ages of 1 and 7 years. Data from both studies suggest that early temperament limits but does not predetermine outcomes. Only about half of inhibited children are at significant risk, and anxiety tends to wax and wane over time. 16

Similarly, Chronis-Tuscano et al. 15 found a four-fold increased likelihood of a lifetime diagnosis of social anxiety disorder among adolescents with consistently high levels of behavioral inhibition between the ages of 1 and 7 years. Data from both studies suggest that early temperament limits but does not predetermine outcomes. Only about half of inhibited children are at significant risk, and anxiety tends to wax and wane over time. 16

We argue that temperament in childhood shapes how a person perceives their environment, which reciprocally affects social interaction and possible social outcomes and mental health outcomes. 17 This dynamic is particularly evident in early adolescence, during which the emergence of a peer group with more significant developmental influence coincides with a dramatic increase in psychopathology,16 in particular social phobia. 6.15.18 Temperament also shapes vital cognitive processes such as attention and certain executive processes that underpin how children perceive and respond to social stimuli in the environment.

Issues

Questions concerning the functional and structural relationship between temperament and anxiety remain open. 19 Several reviews of 10,17,20,21 noted a variety of behavioral and physiological similarities and differences between temperamentally retarded groups and anxious individuals. If anxiety and inhibited temperament are seen as two distinct constructs, then temperament either exposes the child to the risk of developing anxiety or influences the persistence or severity of anxiety disorders once they occur. 10 On the other hand, these terms may simply refer to different aspects of the same construct, and the differences between them are then forced by opinions in the field. 21

Scientific context

The scientific literature suggests that deviations in both "upward" a attention mechanisms and "downward" a executive control processes may play a key role in the etiology and maintenance of anxiety. 22 These disturbances extend to both emotionally charged and emotionally neutral stimuli, reflecting a prioritization of certain categories of stimuli (i.e. erroneous attitudes towards stimuli) along with increased alertness to one's own activity and behavior (i.e. cognitive monitoring) .

22 These disturbances extend to both emotionally charged and emotionally neutral stimuli, reflecting a prioritization of certain categories of stimuli (i.e. erroneous attitudes towards stimuli) along with increased alertness to one's own activity and behavior (i.e. cognitive monitoring) .

Anxious children 23-25 and adults 26-27 show attention bias towards threatening stimuli. Previous work has shown 28.29 that adolescents with clinically significant anxiety showed disturbances in the reaction of the amygdala b and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex c (vlPFC) to threat when performing tasks for attention distortions. Attention distortions, as such, are automatic "bottom-up" mechanisms that shape cognition and behavior. The study also implies a neural network in the prefrontal cortex that engages attention to closely follow the activity, taking into account the feedback as the person then applies more specialized executive control mechanisms to correct subsequent behavior. 30-32 Anxiety-related disorders of this pattern are evident in both children, 33 and adults. 34 Imaging studies have implicated the anterior cingulate cortex d (ACC) in this process, as it is hyperactive in anxious individuals during tasks that require cognitive control or "top-down" control. 35

30-32 Anxiety-related disorders of this pattern are evident in both children, 33 and adults. 34 Imaging studies have implicated the anterior cingulate cortex d (ACC) in this process, as it is hyperactive in anxious individuals during tasks that require cognitive control or "top-down" control. 35

Key Questions

Among typically developing children, approximately 15-20% of Caucasian children in the United States exhibit a behaviorally inhibited temperament in early childhood. Longitudinal studies have shown that about half of these behaviorally retarded children go on to develop anxiety disorders into adolescence and adulthood. A key research question in terms of early intervention is to identify the factors that lead to these different trajectories over time. That is, what factors (either in surrounding adults or in the child himself) protect against anxiety or increase the risk of developing it.

Recent research results

Attention distortions in relation to threat

Recent research suggests that behavioral retardation is characterized by impaired control of attention. 36.37 Two recent longitudinal studies 18.38 examined the relationship between behavioral inhibition in childhood, attentional distortions to threatening stimuli, and propensity to withdraw from social contact. Pérez-Edgar et al 18 found that adolescents who were behaviorally retarded as children exhibited a distortion of attention towards a potential threat. In addition, threat attention bias mediated a statistical association between behavioral inhibition in childhood and propensity to withdraw from social contact during adolescence. In a separate study, Pérez-Edgar et al. 38 found that behavioral inhibition at the age of walking was predictive of high social avoidance in early childhood. Again, this relationship was statistically mediated by threat attention bias such that the relationship between behavioral inhibition and social avoidance was only noticeable in children who showed threat attention bias. These data provide support for a view that threat attention distortions are an important mediator of behavioral inhibition and the subsequent occurrence of clinical anxiety.

These data provide support for a view that threat attention distortions are an important mediator of behavioral inhibition and the subsequent occurrence of clinical anxiety.

Executive processes: inhibitory control and cognitive monitoring

Inhibitory control characterizes the ability to restrain and suppress dominant responses and behaviors in favor of more appropriate or subdominant responses and behaviors39. Cognitive monitoring represents the ability to pay attention to one's own activities, notice errors, and correct behavior based on feedback. It is believed that these control processes play a role in the regulation of negative emotions and in such a property of temperament as reactivity. 40-42

Several studies have shown that inhibitory control mediates the ability to predict the occurrence of anxiety behaviors based on measurements of temperamental manifestations of behavioral inhibition. Children with a high level of inhibitory control were found to be more socially anxious, 43 less socially competent and more socially withdrawn, 44 than behaviorally inhibited children with a low level of inhibitory control. Similarly, White et al. 45 found that a high level of inhibitory control increased the risk of anxiety disorders among highly behaviorally inhibited children.

Similarly, White et al. 45 found that a high level of inhibitory control increased the risk of anxiety disorders among highly behaviorally inhibited children.

In independent studies, increased cognitive monitoring has been found to be associated with increased anxiety in both adults and children. 48 McDermott et al49 found that the level of cognitive monitoring was higher in adolescents with severe childhood behavioral retardation compared with adolescents with low levels of behavioral retardation. Moreover, increased monitoring mediated early behavioral inhibition and later anxiety disorders. 49 Thus, like the distortions of attention to threatening stimuli, the executive processes of inhibitory control and cognitive monitoring act as a mediator for a child's temperament prone to an increased risk of anxiety.

Unexplored areas

Age changes result from the interaction between the child's innate characteristics and environmental context, making the child both creator and product of the environment. 50 Behavioral inhibition may prompt the child to go in one of a number of directions, and the expected outcome may be the result of multiple provocative paths. 10 Research thus needs to explain the operation of a number of mediating factors that may come into play at various points during development. So far, there are very few studies analyzing the discontinuous nature of behavioral retardation and possible confounding protective factors that may contribute to the discontinuity of the behavioral retardation trajectory and further prevention of psychopathology. The discontinuity of these behaviors provides a good opportunity to identify factors that could potentially be used in prevention efforts.

50 Behavioral inhibition may prompt the child to go in one of a number of directions, and the expected outcome may be the result of multiple provocative paths. 10 Research thus needs to explain the operation of a number of mediating factors that may come into play at various points during development. So far, there are very few studies analyzing the discontinuous nature of behavioral retardation and possible confounding protective factors that may contribute to the discontinuity of the behavioral retardation trajectory and further prevention of psychopathology. The discontinuity of these behaviors provides a good opportunity to identify factors that could potentially be used in prevention efforts.

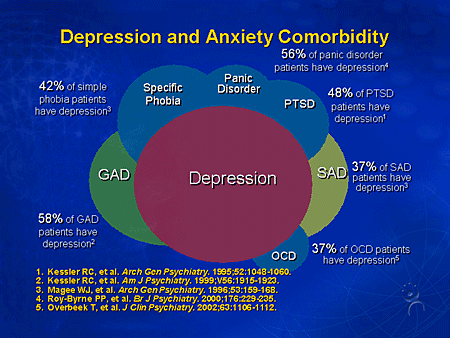

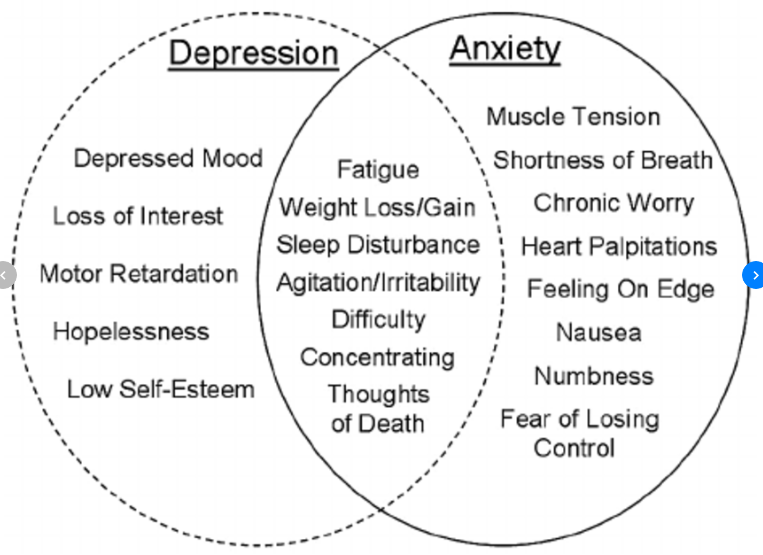

In addition, the relationship between behavioral retardation and depression is much less understood. Given the relationship between behavioral retardation and depression, it is important to note that people with anxiety disorders have an increased risk of developing depression compared to non-anxious people, 51 and data show that in many cases, the presence of one or another anxiety disorder precedes the development of depression. deep depression. 52 Given this temporal relationship between anxiety and depression, it is important to understand that the relationship between behavioral inhibition and depression can be highly dependent on the presence of anxiety. One study is known to have found that social anxiety was a necessary intermediate between behavioral retardation and depression. 53 Similarly, other studies 54 that have found relationships between behavioral retardation, anxiety, and depression have used structural equation modeling, which showed that the pathway by which behavioral retardation leads to anxiety, which in turn leads to depression, provided the most accurate match to the data.

deep depression. 52 Given this temporal relationship between anxiety and depression, it is important to understand that the relationship between behavioral inhibition and depression can be highly dependent on the presence of anxiety. One study is known to have found that social anxiety was a necessary intermediate between behavioral retardation and depression. 53 Similarly, other studies 54 that have found relationships between behavioral retardation, anxiety, and depression have used structural equation modeling, which showed that the pathway by which behavioral retardation leads to anxiety, which in turn leads to depression, provided the most accurate match to the data.

The specificity of the social and non-social components of behavioral inhibition in childhood and their relationship to symptoms of anhedonic depression, social anxiety, and agitation in young adults have now been studied by self-reporting in additional studies. The results were compared with studies showing that non-social behavioral retardation (“fearfulness”), but not social behavioral retardation, increased the risk of future depression; 55 and with other studies showing that depressive symptoms were more strongly associated with social than with non-social behavioral disorder in childhood. 56

56

Interestingly, Sportel 57 et al. investigated the direct (additive) and indirect (interactive) effects of behavioral retardation and attention control on different dimensions of internalization in a sample of normal adolescents. The results showed a stronger association of behavioral retardation, compared with attention control, with symptoms of anxiety, and a stronger association of attention control, compared with behavioral retardation, with symptoms of depression. Moreover, while behavioral retardation was associated with both anxiety and depression, attentional control mediated this relationship, thus reducing the impact of severe behavioral retardation on both dimensions of internalization.

Finally, in considering temperament as a vulnerability factor for depression, it is important to note that, in addition to behavioral inhibition, some theorists have developed temperament models that associate additional temperament styles, namely Positive Emotion (PE) and Negative Emotion (NE), with depression. 58 Many cross-sectional studies have provided evidence that youth and adults with diagnosed symptoms of depression exhibit reduced levels of PE and increased levels of NE, 59,60,61 and their combination was associated with coinciding depressive symptoms in samples of clinical groups 62,63 and groups of people examined en masse at the place of residence. 61,64,65 Moreover, longitudinal studies have shown that lower levels of PE 60,66,67 and higher levels of NE in childhood 68-70 predict the development of depressive symptoms and disorders. For example, low levels of PE in preschoolers predicted high levels of depressogenic-type cognitive style at age 7 and depressive symptoms at age 10. 71.72

58 Many cross-sectional studies have provided evidence that youth and adults with diagnosed symptoms of depression exhibit reduced levels of PE and increased levels of NE, 59,60,61 and their combination was associated with coinciding depressive symptoms in samples of clinical groups 62,63 and groups of people examined en masse at the place of residence. 61,64,65 Moreover, longitudinal studies have shown that lower levels of PE 60,66,67 and higher levels of NE in childhood 68-70 predict the development of depressive symptoms and disorders. For example, low levels of PE in preschoolers predicted high levels of depressogenic-type cognitive style at age 7 and depressive symptoms at age 10. 71.72

Conclusions

Behavioral inhibition is a risk factor for the development of internalizing disorders, although research suggests that not all children with this temperament develop the disorder. Current research is focused on describing the complex interplay of temperament with potential mediating factors that can alter temperament trajectories. Studies focusing on endogenous factors suggest that both attention and executive processes are important regulators of the development of behavioral inhibition towards anxiety or psychological resistance to such disorders. Although it is not mentioned in this review, there is a large body of work on the role of exogenous factors in regulating the temperament of behavioral inhibition. 16.73

Current research is focused on describing the complex interplay of temperament with potential mediating factors that can alter temperament trajectories. Studies focusing on endogenous factors suggest that both attention and executive processes are important regulators of the development of behavioral inhibition towards anxiety or psychological resistance to such disorders. Although it is not mentioned in this review, there is a large body of work on the role of exogenous factors in regulating the temperament of behavioral inhibition. 16.73

Recommendations for parents, services and policy

Identifying young children who are at risk of developing anxiety disorders and implementing preventive (prophylactic) interventions to reduce risk are important outcomes of behavioral inhibition research. Due to the obedient and "comfortable" nature of behaviorally retarded children, teachers and parents may not always recognize such children in early childhood and primary school. Since only a few children with inhibited behavior develop anxiety disorders later on, it is important to identify both endogenous and exogenous factors that mediate the relationship of temperament and psychopathology. Preliminary research contributes to an optimistic view of prevention strategies and easily accessible educational programs for parents and caregivers of adult behaviorally inhibited preschoolers. 74 These programs aim to teach adults about the nature of temperament and withdrawal and how to apply techniques by which they can help behaviorally retarded children develop the ability to manage reactions to new situations, thus promoting the development of social skills and reducing inhibited and anxious behavior over time. Finally, innovative approaches that include training in attention and executive processes can significantly reduce anxiety-induced withdrawal in temperamentally at-risk individuals.

Since only a few children with inhibited behavior develop anxiety disorders later on, it is important to identify both endogenous and exogenous factors that mediate the relationship of temperament and psychopathology. Preliminary research contributes to an optimistic view of prevention strategies and easily accessible educational programs for parents and caregivers of adult behaviorally inhibited preschoolers. 74 These programs aim to teach adults about the nature of temperament and withdrawal and how to apply techniques by which they can help behaviorally retarded children develop the ability to manage reactions to new situations, thus promoting the development of social skills and reducing inhibited and anxious behavior over time. Finally, innovative approaches that include training in attention and executive processes can significantly reduce anxiety-induced withdrawal in temperamentally at-risk individuals.

Literature

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y.

The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry . Jan 1998;55(1):56-64.

The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry . Jan 1998;55(1):56-64. - Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Frequency and comorbidity of social phobia and social fears in adolescents. Behavior Research and Therapy . Sep 1999;37(9):831-843.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Prevalence and comorbidity of DSM-III-R diagnoses in a birth cohort of 15 year olds. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Nov 1993;32(6):1127-1134.

- McGee R, Feehan M, Williams S, Partridge F, Silva PA, Kelly J. DSM-III disorders in a large sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Jul 1990;29(4):611-619.

- Hayward C, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB. Linking self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition to adolescent social phobia. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry .

Dec 1998;37(12):1308-1316.

Dec 1998;37(12):1308-1316. - Schwartz CE, Snidman N, Kagan J. Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Aug 1999;38(8):1008-1015.

- Schofield CA, Coles ME, Gibb BE. Retrospective reports of behavioral inhibition and young adults' current symptoms of social anxiety, depression, and anxious arousal. Journal of Anxiety Disorders . Oct 2009;23(7):884-890.

- Kagan J. Temperamental contributions to affective and behavioral profiles in childhood. In: Hoffman S.G., Dibartolo, P.M., ed. From social anxiety to social phobia: Multiple perspectives. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001:216-234.

- Prior M, Smart D, Sanson A, Oberklaid F. Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Apr 2000;39(4):461-468.

- Perez-Edgar K, Fox NA. Temperament and anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America . Oct 2005;14(4):681-706, viii.

- Garcia C, Kagan J, Resnick JS. Behavioral inhibition in young children. Child Development. 1984;55(3):1005-1019.

- Wichmann C, Coplan R, Daniels T. The social cognitions of socially withdrawn children. Social Development . 2004(13):377-392.

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, et al. Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of Psychiatry . Oct 2001;158(10):1673-1679.

- Hirshfeld DR, Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, et al. Stable behavioral inhibition and its association with anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Jan 1992;31(1):103-111.

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, et al. Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence.

Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Sep 2009;48(9):928-935.

Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Sep 2009;48(9):928-935. - Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, Ghera MM. Behavioral inhibition: linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology . 2005;56:235-262.

- Lonigan CJ, Vasey MW, Phillips BM, Hazen RA. Temperament, anxiety, and the processing of threat-relevant stimuli. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology . Mar 2004;33(1):8-20.

- Perez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, McDermott JM, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA. Attention biases to threat and behavioral inhibition in early childhood shape adolescent social withdrawal. Emotion . Jun 2010;10(3):349-357.

- Rapee RM, Coplan RJ. Conceptual Relations Between Anxiety Disorder and Fearful Temperament. Social Anxiety in Childhood: Bridging Developmental and Clinical Perspectives . 2010;127:17-31.

- Degnan KA, Fox NA.

Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: multiple levels of a resilience process. Developmental Psychopathology . Summer 2007;19(3):729-746.

Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: multiple levels of a resilience process. Developmental Psychopathology . Summer 2007;19(3):729-746. - Lahey BB. Commentary: role of temperament in developmental models of psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology . Mar 2004;33(1):88-93.

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van-IJzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin . Jan 2007;133(1):1-24.

- Roy AK, Vasa RA, Bruck M, et al. Attention bias towards threat in pediatric anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Oct 2008;47(10):1189-1196.

- Waters AM, Henry J, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS. Attentional bias towards angry faces in childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry . Jun 2010;41(2):158-164.

- Waters AM, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS. Attentional bias for emotional faces in children with generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Apr 2008;47(4):435-442.

- Mathews A, MacLeod C. Selective processing of threat cues in anxiety states. Behavior Research and Therapy . 1985;23(5):563-569.

- Wilson E, MacLeod C. Contrasting two accounts of anxiety-linked attentional bias: selective attention to varying levels of stimulus threat intensity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology . May 2003;112(2):212-218.

- Monk CS, Nelson EE, McClure EB, et al. Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation and attentional bias in response to angry faces in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry . Jun 2006;163(6):1091-1097.

- Monk CS, Telzer EH, Mogg K, et al. Amygdala and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation to masked angry faces in children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder.

Archives of General Psychiatry . May 2008;65(5):568-576.

Archives of General Psychiatry . May 2008;65(5):568-576. - Ridderinkhof KR, van den Wildenberg WP, Segalowitz SJ, Carter CS. Neurocognitive mechanisms of cognitive control: the role of prefrontal cortex in action selection, response inhibition, performance monitoring, and reward-based learning. Brain and Cognition . Nov 2004;56(2):129-140.

- Botvinick MM, Braver TS, Barch DM, Carter CS, Cohen JD. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review . Jul 2001;108(3):624-652.

- Eysenck MW, Derakshan N, Santos R, Calvo MG. Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory. Emotion . May 2007;7(2):336-353.

- Ladouceur CD, Dahl RE, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Ryan ND. Increased error-related negativity (ERN) in childhood disorders: ERP and source localization. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry . Oct 2006;47(10):1073-1082.

- Hajcak G, McDonald N, Simons RF. Anxiety and error-related brain activity.

Biological Psychology . Oct 2003;64(1-2):77-90.

Biological Psychology . Oct 2003;64(1-2):77-90. - Ursu S, Stenger VA, Shear MK, Jones MR, Carter CS. Overactive action monitoring in obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging. Psychological Science . Jul 2003;14(4):347-353.

- Fox NA, Hane AA, Pine DS. Plasticity for affective neurocircuitry - How the environment affects gene expression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. Feb 2007;16(1):1-5.

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Perez-Edgar K, White L. The Biology of temperament: An integrative approach. In: Nelson C, Luciana M, eds. The handbool of developmental cognitive neuroscience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2008:839-854.

- Perez-Edgar K, Reeb-Sutherland BC, McDermott JM, et al. Attention biases to threat link behavioral inhibition to social withdrawal over time in very young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology . Aug 2011;39(6):885-895.

- Rothbart MK, Ellis LK, Rueda MR, Posner MI.

Developing mechanisms of temperamental effortful control. J Pers . Dec 2003;71(6):1113-1143.

Developing mechanisms of temperamental effortful control. J Pers . Dec 2003;71(6):1113-1143. - Derryberry D, Rothbart MK. Reactive and effortful processes in the organization of temperament. Development and Psychopathology . Fall 1997;9(4):633-652.

- Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM. Temperamental basis of anxiety dosorders in children. In: Vasey MW, Dadds M, eds. The Developmental Psychopathology of anxiety . New York: Oxford University Press; ; 2001:60-91.

- Waters AM, Valvoi JS. Attentional bias for emotional faces in pediatric anxiety disorders: an investigation using the emotional Go/No Go task. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry . Jun 2009;40(2):306-316.

- Thorell L, Bohlin G, Rydell A. Two types of inhibitory control: predictive relations to social functioning. International Journal of Behavioral Development . 2004; 28:193-203.

- Fox NA, Henderson HA. Temperament, emotion, and executive function: Influences on the development of self-regulation.

Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society. San Francisco, 2000, April.

Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society. San Francisco, 2000, April. - White LK, McDermott JM, Degnan KA, Henderson HA, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and anxiety: the moderating roles of inhibitory control and attention shifting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology . Jul 2011;39(5):735-747.

- Righi S, Mecacci L, Viggiano MP. Anxiety, cognitive self-evaluation and performance: ERP correlates. Journal of Anxiety Disorders . Dec 2009;23(8):1132-1138.

- Sehlmeyer C, Konrad C, Zwitserlood P, Arolt V, Falkenstein M, Beste C. ERP indices for response inhibition are related to anxiety-related personality traits. Neuropsychologia . Jul 2010;48(9):2488-2495.

- Hum KM, Manassis K, Lewis MD. Neural mechanisms of emotion regulation in childhood anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry . In Press. 2012.

- McDermott JM, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA.

A history of childhood behavioral inhibition and enhanced response monitoring in adolescence are linked to clinical anxiety. Biological Psychiatry . Mar 1 2009;65(5):445-448.

A history of childhood behavioral inhibition and enhanced response monitoring in adolescence are linked to clinical anxiety. Biological Psychiatry . Mar 1 2009;65(5):445-448. - Lerner RM, Hess LE, Nitz KA. Developmental perspective on psychopathology. In: Herson M, Last CG, eds. Handbook of child and adult psychopathology: a longitudinal perspective . Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press; 1991:9-32.

- Stein MB, Fuetsch M, Muller N, Hofler M, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. Social anxiety disorder and the risk of depression: a prospective community study of adolescents and young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry . Mar 2001;58(3):251-256.

- Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology . Nov 2001;110(4):585-599.

- Gladstone GL, Parker GB. Is behavioral inhibition a risk factor for depression? Journal of Affective Disorders .

Oct 2006;95(1-3):85-94.

Oct 2006;95(1-3):85-94. - Muris P, Merckelbach H, Schmidt H, Gadet B, Bogie N. Anxiety and depression as correlates of self-reported behavioral inhibition in normal adolescents. Behavior Research and Therapy . 2001;39(9):1051-1061.

- Hayward C, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB. Linking self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition to adolescent social phobia. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Dec 1998;37(12):1308-1316.

- Neal JA, Edelmann RJ, Glachan M. Behavioral inhibition and symptoms of anxiety and depression: is there a specific relationship with social phobia? British Journal of Clinical Psychology . Nov 2002;41(Pt 4):361-374.

- Sportel BE, Nauta MH, de Hullu E, de Jong PJ, Hartman CA. Behavioral Inhibition and Attentional Control in Adolescents: Robust Relationships with Anxiety and Depression. Journal of Child and Family Studies . Apr 2011;20(2):149-156.

- Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S.

Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Feb 1994;103(1):103-116.

Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Feb 1994;103(1):103-116. - Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology . May 1998;107(2):179-192.

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry . Nov 1996;53(11):1033-1039.

- Lonigan CJ, Hooe ES, David CF, Kistner JA. Positive and negative affectivity in children: confirmatory factor analysis of a two-factor model and its relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology . Jun 1999;67(3):374-386.

- Joiner TE, Jr., Catanzaro SJ, Laurent J. Tripartite structure of positive and negative affect, depression, and anxiety in child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology . Aug 1996;105(3):401-409.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology . Aug 1996;105(3):401-409. - Lonigan CJ, Carey MP, Finch AJ, Jr. Anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: negative affectivity and the utility of self-reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology . Oct 1994;62(5):1000-1008.

- Anthony JL, Lonigan CJ, Hooe ES, Phillips BM. An affect-based, hierarchical model of temperament and its relations with internalizing symptomatology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology . Dec 2002;31(4):480-490.

- Chorpita BF. The tripartite model and dimensions of anxiety and depression: an examination of structure in a large school sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology . Apr 2002;30(2):177-190.

- Block JH, Gjerde PF. Personality antecedents of depressive tendencies in 18-year-olds: a prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology . May 1991;60(5):726-738.

- van Os J, Jones P, Lewis G, Wadsworth M, Murray R.

Developmental precursors of affective illness in a general population birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry . Jul 1997;54(7):625-631.

Developmental precursors of affective illness in a general population birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry . Jul 1997;54(7):625-631. - Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S. Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Psychol . Feb 1994;103(1):103-116.

- Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM, Hooe ES. Relations of positive and negative affectivity to anxiety and depression in children: evidence from a latent variable longitudinal study. Journal of Consultunf and Clinical Psychology . Jun 2003;71(3):465-481.

- Rende RD. Longitudinal relations between temperament traits and behavioral syndromes in middle childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry . Mar 1993;32(2):287-290.

- Dougherty LR, Klein DN, Durbin CE, Hayden EP, Olino TM. Temperamental Positive and Negative Emotionality and Children's Depressive Symptoms: A longitudinal prospective study from age three to age ten.

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29(4):462-488.

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29(4):462-488. - Hayden EP, Klein DN, Durbin CE, Olino TM. Positive emotionality at age 3 predicts cognitive styles in 7-year-old children. Development and Psychopathology . Spring 2006;18(2):409-423.

- Lahat A, Hong M, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition: is it a risk factor for anxiety? International Review of Psychiatry . Jun 2011;23(3):248-257.

- Rapee RM. The development and modification of temperamental risk for anxiety disorders: prevention of a lifetime of anxiety? Biological Psychiatry . Nov 15 2002;52(10):947-957.

Notes

- “Upward” and “downward” information processing strategies are two complementary cognitive processes. The "bottom-up" strategy refers to processes that involve sensory stimulation leading to perceptual processing and subsequent cortical interpretation. In general, the structures involved are, firstly, the subcortical, limbic, then the cortical areas of the brain.

"Downstream" processing refers to the control or modulation of subcortical or limbic processing by cortical regions. – (approx. per.)

"Downstream" processing refers to the control or modulation of subcortical or limbic processing by cortical regions. – (approx. per.) - A brain structure believed to be involved in the detection of a threat or novelty and the production of a conditioned response in connection with the experience of fear.

- The most initial part of the anterior cerebral cortex, located behind the frontal bone. This region of the brain is involved in higher-level executive functions such as attention control, emotion regulation, conflict resolution, complex goal-directed behavior planning, and decision-making processes.

- A subdivision of the anterior cingulate cortex responsible for error detection, response and conflict monitoring, anticipation, attention, motivation, and regulation/impairment of emotional response.

For citation:

Fox NA, Frenkel TI. Temperament in early childhood and the development of anxiety and depression.