High functioning ocd

High Functioning OCD: Signs and Symptoms

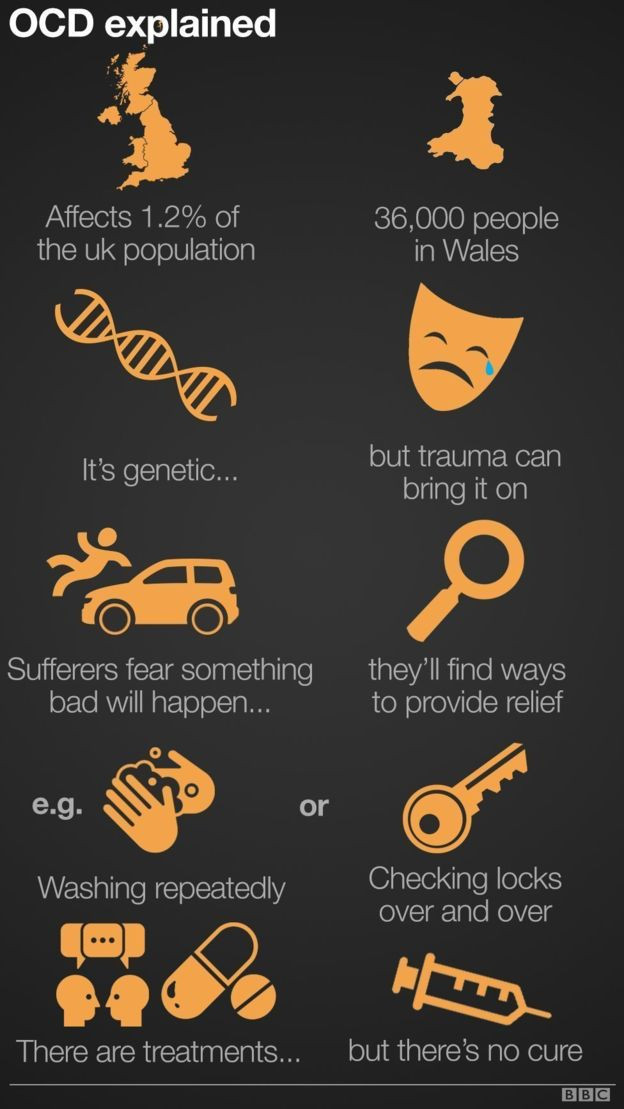

People with high functioning OCD can do well, despite significant distress. Treatment can help with symptom management and improve quality of life.

People who don’t have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) may negatively perceive the condition. They may assume someone with OCD can’t work or have relationships.

While many people with OCD experience barriers to job success and healthy relationships, others may achieve great professional and personal success.

Nonetheless, they still live with the daily reality of OCD. The mental health advocacy group Made of Millions calls this “high functioning OCD.”

Many people with high functioning OCD don’t seek treatment or may not even recognize they live with a treatable condition. But treatment options, such as talk therapy and medication, can help people with OCD cope with their symptoms.

OCD can be a debilitating condition, but if you experience symptoms, help is available. You’re not alone.

According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA), about 2.2 million people in the United States live with OCD. Some are “high functioning.”

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) doesn’t use the term “high functioning OCD” in its diagnostic criteria. Nevertheless, some scales help define the severity of OCD, such as the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS).

High functioning OCD isn’t the same as mild or moderate OCD. But the Y-BOCS scale can give a picture of how the experience of OCD is different from person to person.

The advocacy group OCD Action notes that it’s very common for people with OCD to hide their symptoms. They may engage in invisible compulsions when around others but feel overwhelmed by the need for outward compulsions while alone.

People with high functioning OCD may regularly experience intrusive thoughts. Because they can maintain the outward appearance that everything is OK, they may not seek help for OCD. Their friends and family may also have no idea there’s anything wrong.

Their friends and family may also have no idea there’s anything wrong.

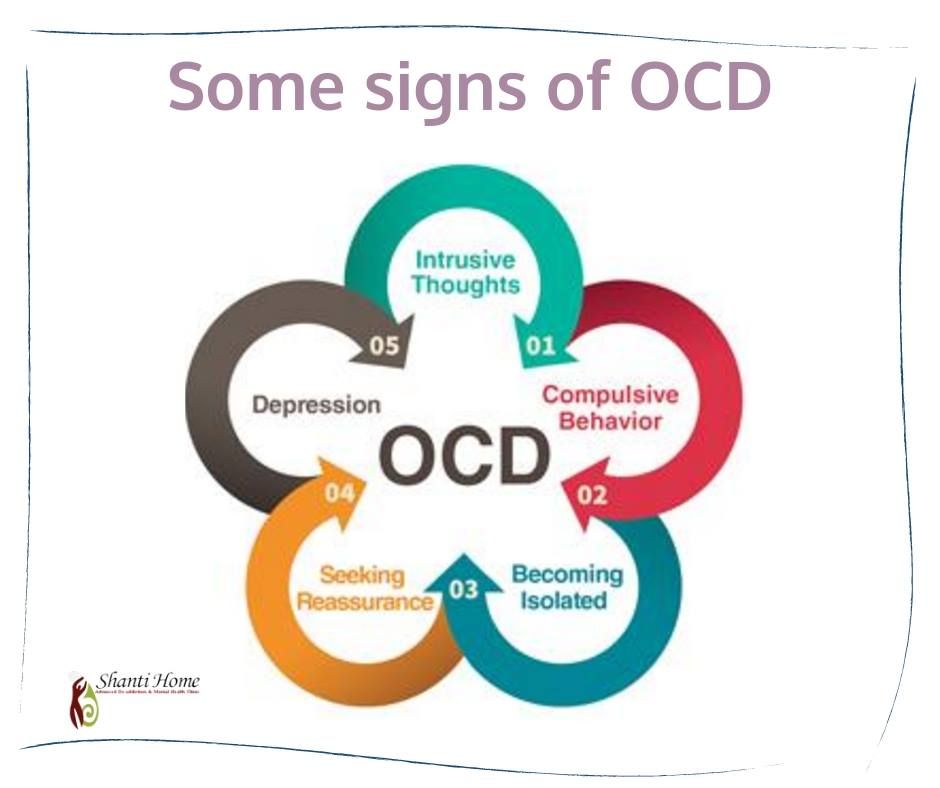

Even though OCD is different for everyone, there are some common signs and symptoms. If you think you have high functioning OCD, a doctor may first assess whether you meet the general diagnosis.

These are the criteria for an OCD diagnosis:

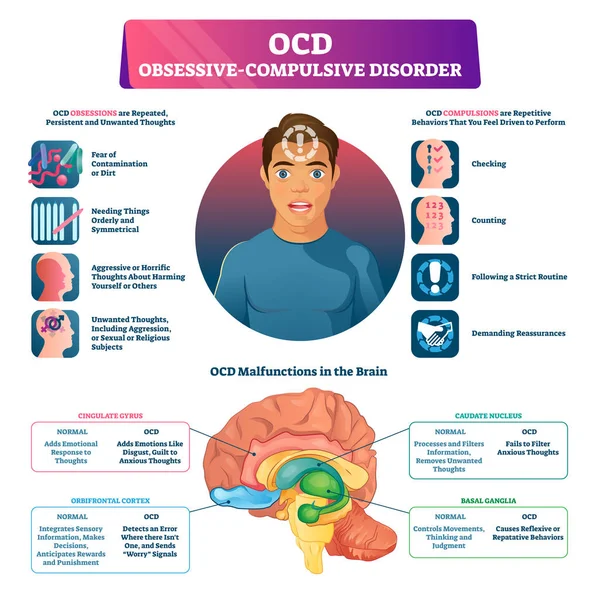

- Having obsessions, compulsions, or both. Obsessions are distressing thoughts that regularly come back. The person tries to suppress the thoughts, for example, by engaging in a compulsion.

- Compulsions are repetitive mental or physical behaviors in response to an obsession. They’re meant to resolve anxiety but are excessive or unrelated to the harm one wants to prevent.

- Obsessions are time-consuming or cause significant distress. Alternatively, the obsessions may cause impairment in social, occupational, or other functioning.

Therefore, someone with high functioning OCD may have compulsions that cause distress but don’t impair functioning.

Indeed, compulsions aren’t necessary to get an OCD diagnosis. Some people may experience obsessions and take action to suppress them that doesn’t involve compulsions.

There are many ways to experience OCD. Common obsessions and compulsions often define types of OCD. The International OCD Foundation offers these examples, but you may have others:

Obsessions

- Contamination: such as from germs, disease, or dirt

- Losing control: such as acting on impulse to cause harm, stealing, or violent images

- Unwanted sexual thoughts: such as forbidden or perverse sexual thoughts

- Religious obsessions: such as concern about morality or offending God

- Harm: such as fear of being responsible for harm to others

- Perfectionism: such as concern with being exact, or fear of losing things

According to Made of Millions, someone with high functioning OCD may avoid conference rooms or work restrooms because of contamination fears or worry constantly about co-workers’ perception of them.

Compulsions

- Washing and cleaning: such as excessive handwashing

- Mental compulsions: such as counting during a task to end on a “good” number

- Checking: making sure not to make a mistake or cause harm

- Repeating: such as repeating body movements like tapping or repeating activities in multiple

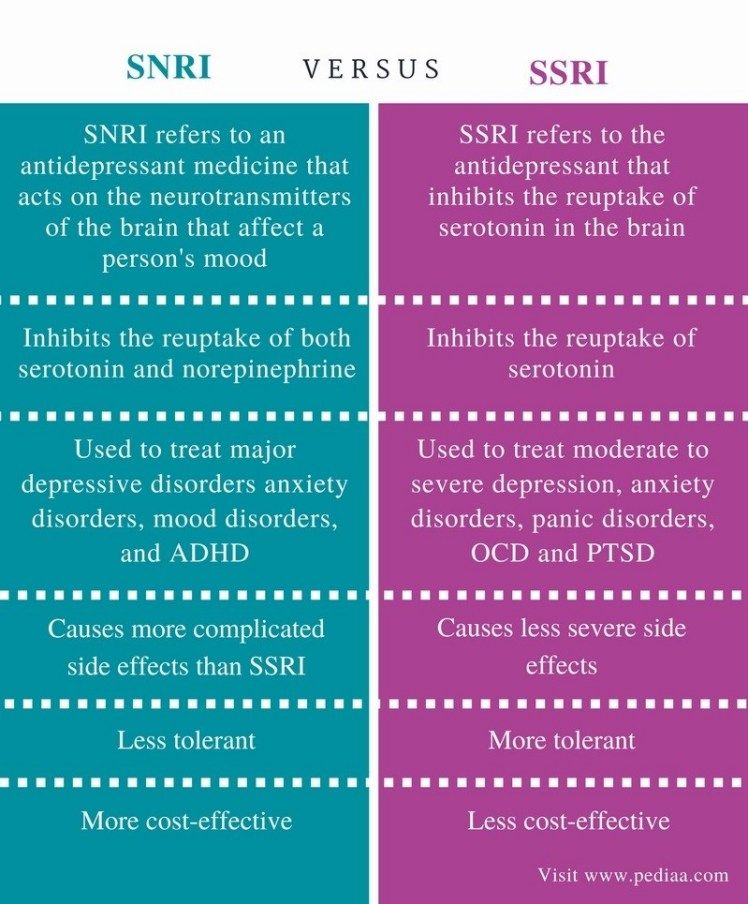

Many people with OCD can benefit from treatment, which may involve:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Exposure and response prevention is a form of CBT for OCD. People are exposed to the object of their obsessions but don’t engage in compulsions. They gradually gain the skills to cope with obsessions, and anxiety goes down over time.

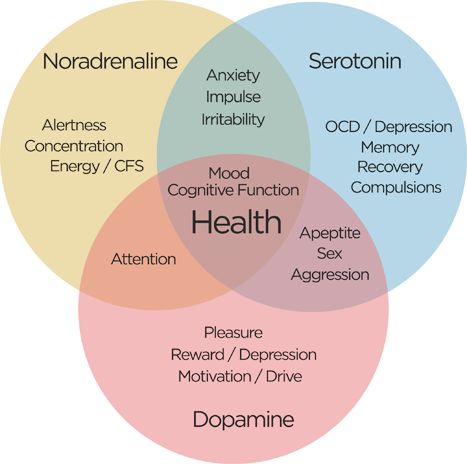

- Medication. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), commonly used for depression, can be an effective OCD treatment.

Each treatment plan is tailored to a particular person. Therefore, someone with high functioning OCD will develop a plan with a therapist that works for their symptoms.

Therefore, someone with high functioning OCD will develop a plan with a therapist that works for their symptoms.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder involves intrusive thoughts that result in distress. Many people with OCD also use compulsions to cope with these obsessions.

Someone has “high functioning” OCD if they’re able to carry on with their work and home life despite the symptoms of OCD.

People with high functioning OCD can benefit from treatment, including CBT and medication. Through treatment, people begin to manage their obsessions, resulting in less anxiety.

You can get started by visiting the American Psychiatric Association’s Help with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder page.

You can also visit Psych Central’s Find Help page for more ways to connect for support, both online and in your community.

How Can I Tell If I Have High-Functioning OCD?

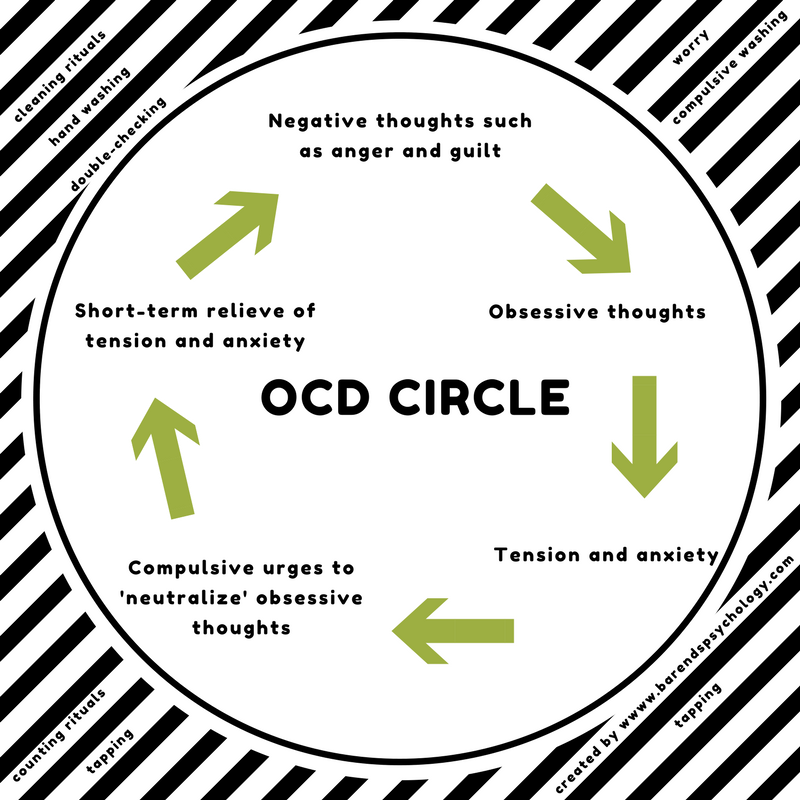

Overall, the main symptom(s) of OCD is intrusive thoughts and/or compulsive behaviors (in response to the intrusive thoughts or obsession). The goal of compulsions is to ease the stress and anxiety causing the intrusive thoughts (so the obsession goes away).

The goal of compulsions is to ease the stress and anxiety causing the intrusive thoughts (so the obsession goes away).

Ruminating Thoughts

For a person with mild-, moderate-, or low-functioning OCD, intrusive thoughts, along with ruminations, ritualistic behaviors, and crippling stress and anxiety are almost continuous. While a person with high-functioning OCD may have similar symptoms (i.e., ruminating thoughts) to other “levels” of OCD, these symptoms are not as evident.

Work or School Sucess

People with high-functioning OCD may have distressing symptoms, but still, be able to complete school or work tasks, pay bills, cook, clean, get to work or school on time, take care of bills, spend time with friends, and family, etc. In other words, these individuals can still be productive and successful.

Surprisingly, high-functioning OCD and anxiety can be a benefit in some occupations, like detail-oriented accounting jobs, but in jobs that require highly stressful or fast-paced jobs, it could be a disadvantage. So, even high-functioning OCD sufferers can experience high levels of anxiety that could impede the completion of school or work tasks, especially if they start to obsess over aspects of the job.

So, even high-functioning OCD sufferers can experience high levels of anxiety that could impede the completion of school or work tasks, especially if they start to obsess over aspects of the job.

Excessive Worrying

OCD thought processes are “distinctive.” People with OCD, even high-functioning OCD, are inundated with intrusive thoughts, urges, fears, emotions, images, doubts, etc., that they are unable to get out of their minds. For instance, you see a car crash. Because it is so disturbing, you are unable to “unsee it” or get it out of your mind.

You keep thinking about it and worrying about the occupants inside of the smashed-up cars. These thoughts and fears trigger your anxiety to the point that you feel compelled to do something to “turn off” those thoughts and fears. If you have high-functioning OCD, you still experience the stress and angst but can cope with it in a way that does not disrupt your life.

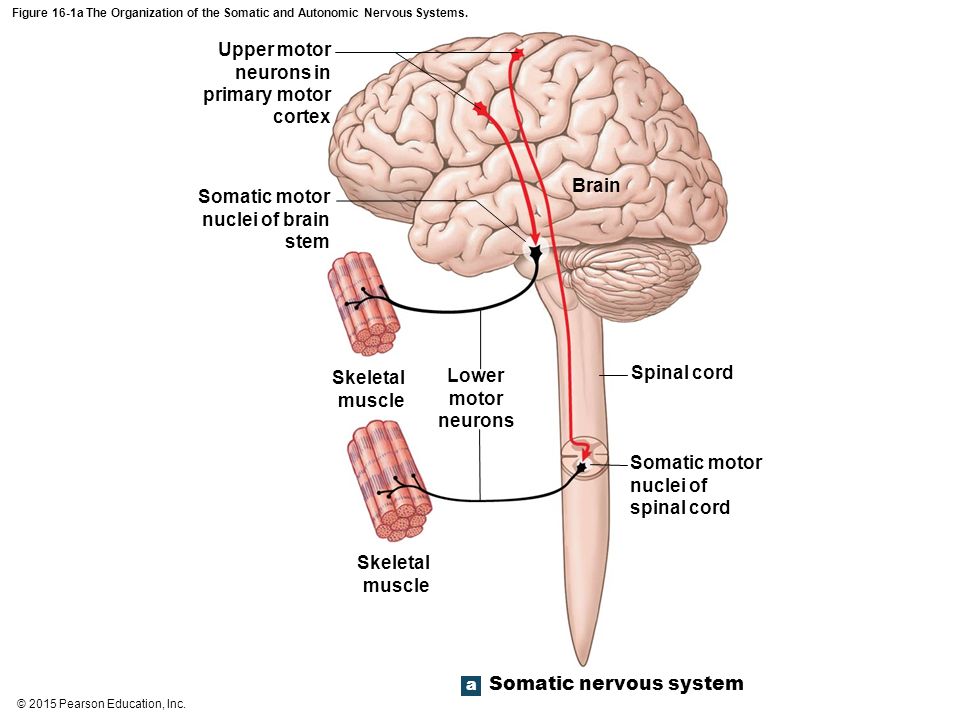

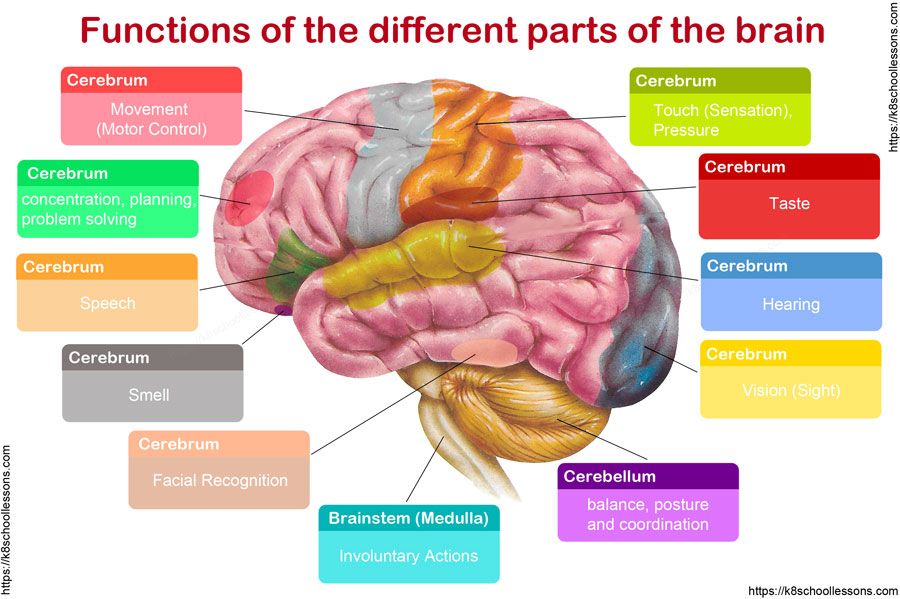

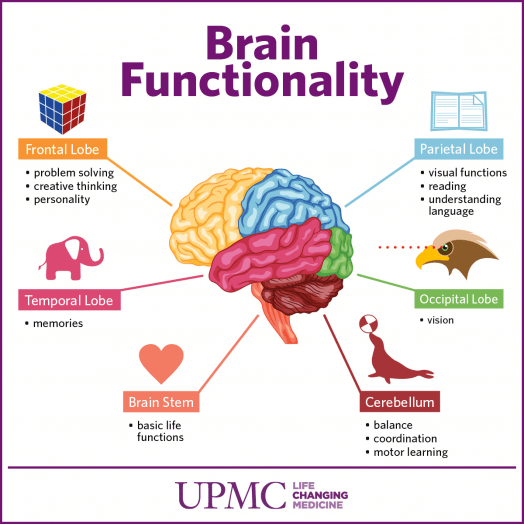

Background Lurking

OCD, even high-functioning OCD, can begin in early childhood (between 8-12 years old), but it can also begin in early adulthood (the 20s). It can also arise after a bout of strep (PANDAS) or following a traumatic brain injury. More research is needed to determine what triggers high-functioning OCD, and how it functions in the brain.

It can also arise after a bout of strep (PANDAS) or following a traumatic brain injury. More research is needed to determine what triggers high-functioning OCD, and how it functions in the brain.

Clandestine Coping Mechanisms

The big difference between the various types of OCD is the behaviors. In high-functioning OCD, obsessions are pronounced and upsetting, however, the behaviors are less time-consuming, life-altering, and visible. For instance, high-functioning OCD sufferers tend to have a habit of constantly monitoring things – i.e., these individuals tend to be “micro-manager” bosses at work.

Runs in Families

People with OCD, in general, have brains that function “differently” the most of the general population. These individuals have neurodivergent thought processes, which means their brains develop and function “differently” than most people. High-functioning OCD sufferers are no exception. Researchers have discovered that OCD, even high-functioning OCD, runs in families. So, if you have noticed that other family members have similar thought processes and/or behaviors, it is not a coincidence. You and your relatives may have high-functioning OCD.

So, if you have noticed that other family members have similar thought processes and/or behaviors, it is not a coincidence. You and your relatives may have high-functioning OCD.

A Feeling of Being “Different” Than Other OCD Sufferers

Many high-functioning OCD sufferers feel like they are different than other lower-functioning OCD sufferers. Because there is no official OCD blood test, it is hard to determine if a person has high-functioning OCD or if he or she has a lower functioning level of OCD. Thus, OCD and the functioning level of OCD are typically diagnosed through assessments and interviews by an OCD therapist.

There are also OCD screening tests, like the one found on the Impulse Therapy website. But keep in mind that scoring how on an OCD screening test does not automatically mean that you have OCD. Nowadays, people like to go online and google OCD symptoms. Then, they rule out OCD, even though they may have it. So, to be properly diagnosed with the condition, a person must be assessed by a trained and licensed OCD therapist.

Note: Understand that just because someone says, “You don’t look like you have OCD,” does not mean that you do not have it. High-functioning OCD sufferers may not present like the traditional OCD sufferer but still have it. Remember, no two OCD sufferers are the exact same, so everyone’s experience is different – and valid. Thus, it is important to create more awareness about the different “types” and function levels of OCD to ensure that everyone receives the OCD support and help they need to get a grip on their symptoms.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and autism

03/05/19

Autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) often coexist, scientists are trying to study both disorders in order to better differentiate them and determine more effective treatment

Author Daisy Yuhas

Source: Spectrum News

Steve Slavin was 48 years old when a visit to a psychologist forced him to dramatically change his ideas about his own life. He had a very difficult year. Slavin began to suffer from anxiety, which manifested itself in negative thoughts and repetitive actions, and this was not the first time he suffered from them. nine0003

He had a very difficult year. Slavin began to suffer from anxiety, which manifested itself in negative thoughts and repetitive actions, and this was not the first time he suffered from them. nine0003

As a child, he could not enter a room unless he had swallowed an even number of times beforehand, and he had to swallow and count to four, six, or eight with one foot up before stepping on a stone in the pavement. As an adult, he often experienced a lot of stress around other people, and he washed his hands again and again because he was terrified of catching something from other people. He also often suffered from depression, due to which he began to avoid acquaintances and friends.

This time his depression and anxiety got worse and his doctor referred him to a psychologist. “I spent weeks, if not months, trying to get an appointment with him,” he recalls. However, within the first 10 minutes of the meeting, the psychologist suddenly stopped asking him about his childhood and current mental health issues, and instead asked him what he knew about autism. nine0003

nine0003

Coincidentally, a relative had spoken to Slavin about autism just two days earlier, suggesting that this might explain his dislike of social situations. Slavin knew almost nothing about autism, but suggested that it was possible. By the end of the consultation, the psychologist was practically certain that “I either have high-functioning autism or some kind of brain damage,” Slavin recalls, chuckling. Only a few years later, the doctor gave him an official diagnosis - obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). He was also confirmed to have autism. nine0003

At first glance, autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder seem to have nothing in common. However, doctors and researchers talk about the intersection of these two disorders. Research data indicate that up to 84% of autistic people suffer from some type of anxiety disorder, and up to 17% of people with autism have OCD. And according to one 2017 study, even more people with OCD have undiagnosed autism.

Part of this overlap may be due to misdiagnosis: OCD-induced rituals may resemble repetitive behaviors in autism, and vice versa. However, there is growing evidence that many people, like Slavin, have both disorders. A 2015 study that analyzed the health records of 3.4 million Danish people over 18 years found that as adults, people with autism are twice as likely to be diagnosed with OCD than people without autism. Similarly, the same study found that people with OCD were four times more likely to be diagnosed with autism as adults than people without OCD. nine0003

However, there is growing evidence that many people, like Slavin, have both disorders. A 2015 study that analyzed the health records of 3.4 million Danish people over 18 years found that as adults, people with autism are twice as likely to be diagnosed with OCD than people without autism. Similarly, the same study found that people with OCD were four times more likely to be diagnosed with autism as adults than people without OCD. nine0003

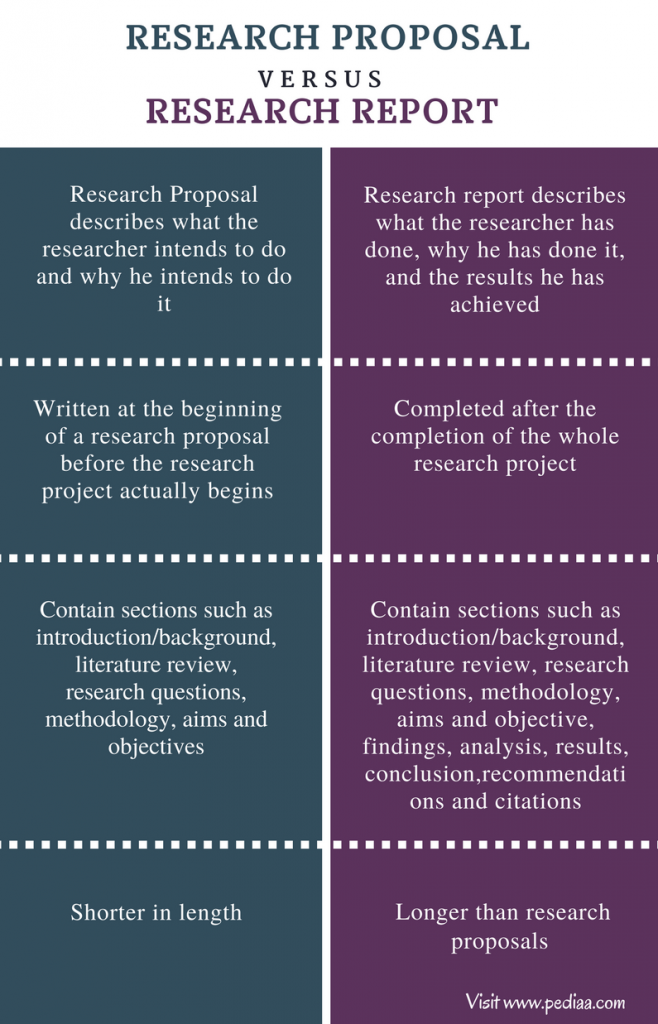

Over the past ten years, researchers have begun to study the combination, interaction, and differences between these two disorders. Understanding these differences is important not only for making a correct diagnosis, but also for choosing an effective treatment. It appears that the experience of people with OCD and autism is unique, different from that of people with one of these disorders. And for these people, standard OCD treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), may not be effective.

Missed diagnoses

Anyone can develop obsessive thoughts (obsessions) or obsessive actions (compulsions). Many people start worrying about not turning off the stove at home, or checking again that they took their keys with them. "It's part of a normal life experience," says Ailsa Russell, a clinical psychologist at the University of Bath in the UK.

Many people start worrying about not turning off the stove at home, or checking again that they took their keys with them. "It's part of a normal life experience," says Ailsa Russell, a clinical psychologist at the University of Bath in the UK.

Most people can get over these unpleasant obsessions and go on with their normal lives. However, with obsessive-compulsive disorder, such anxiety becomes stronger and begins to interfere with normal daily functioning. nine0003

Some people with OCD, like Slavin, count steps or breaths or perform other meaningless actions because they feel that without these actions, something terrible is bound to happen. Other people call themselves "inspectors" - they check again and again that they have done a task correctly, and this prevents them from doing other things. Other people with OCD are constantly bathing or scrubbing because they are afraid of dirt or contamination.

"Typically, people with OCD are aware that their fears and behavior are irrational," says Russell, despite this OCD sufferer is trapped in intense anxiety and compulsive rituals. nine0003

nine0003

The intersection between OCD and autism is still poorly understood. According to a 2015 analysis, people with both disorders are characterized by non-standard sensory responses. For some autistic people, sensory overload is the main source of stress and anxiety. For example, Slavin is terrified of police sirens and doorbells, he says that for his nervous system they are like bomb explosions.

Some researchers say that the social problems of people with autism can increase their anxiety, which in turn can lead to OCD. Failure to interpret social cues can lead to social isolation or bullying by others, which increases anxiety. “Separating anxiety from autism is extremely difficult,” says Roma Vasa, director of mental health services at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, USA. nine0003

These commonalities can make it difficult to distinguish between symptoms of autism and OCD. Even for an experienced clinician, OCD compulsions can resemble the “sameness seeking” or repetitive behaviors of autistic people, which may include tapping, lining up objects, or striving to always walk in the same path. Separating the two states can be a daunting task.

Separating the two states can be a daunting task.

As the 2015 analysis showed, the key difference is that obsessive thoughts (obsessions) lead to obsessive actions (compulsions), but not to autistic symptoms. Another feature is that people with OCD cannot, in principle, replace their rituals with other actions. In Vasa's words: "They need to do everything in a certain way, otherwise they experience anxiety and discomfort." nine0003

At the same time, autistic people tend to have a repertoire of different repetitive behaviors that serve a similar function and from which to choose. “They just go for any behavior that helps them calm down, it doesn’t really matter to them any particular action,” says Jeremy Winstra-Vanderviel, professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, USA.

Thus, doctors need to determine why a person performs a particular action. But this task becomes difficult if it is difficult for the patient to describe his experience in words. Autistic people may have speech, communication, or intellectual impairments and often have significant difficulty identifying and understanding their inner experiences. This can lead to misdiagnosis, as happened in the case of Slavin. nine0003

This can lead to misdiagnosis, as happened in the case of Slavin. nine0003

As a child, Slavin often visited a psychologist's office in the suburbs of London. However, the experts who examined him missed both OCD and autism. Slavin did not speak until the age of 6. According to him, his first childhood memories are classes with a speech therapist and a child psychologist. Even after he started talking, he avoided other people and didn't like making eye contact. He suffered from severe anxiety and abdominal pain.

At about 11 years of age, he was diagnosed with "childhood schizophrenia" and was prescribed Valium and lithium. Doctors warned his parents that he might need a lifelong stay in a medical facility. Instead, he was able to attend a prestigious high school, get a degree and become, in his words, a "slightly more functional" person, and thanks to his passion for music, he was able to launch a career as a professional composer. nine0003

Being diagnosed with autism many years later brought him great relief, but it was also associated with new problems. During conversations with specialists, for example, they began to attribute any of his complexities to autism, including problems with the perception of auditory information. “Once you get this diagnosis, the doctors start saying, ‘Well, it’s because of autism,’ they don’t pay attention to the nuances,” he says. Slavin found that no one can say for sure whether a particular behavior is the result of OCD or autism, or what exactly can be done about it. nine0003

During conversations with specialists, for example, they began to attribute any of his complexities to autism, including problems with the perception of auditory information. “Once you get this diagnosis, the doctors start saying, ‘Well, it’s because of autism,’ they don’t pay attention to the nuances,” he says. Slavin found that no one can say for sure whether a particular behavior is the result of OCD or autism, or what exactly can be done about it. nine0003

General Biology

Slavin's questions may be answered soon as more researchers look at the combination of autism and OCD. Until 10 years ago, research on this topic was practically non-existent, says Suma Jacob, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota, USA. When she said she was interested in studying the two disorders, "the main experts in the field said to pick one disorder," she says. This situation is starting to change, in part because researchers have begun to realize how common it is to combine autism and OCD. nine0003

nine0003

Jacob and colleagues have been tracking repetitive behaviors (which may be associated with autism or OCD) in thousands of children as young as 3 years old. “From a brain perspective, all these disorders are connected,” she says.

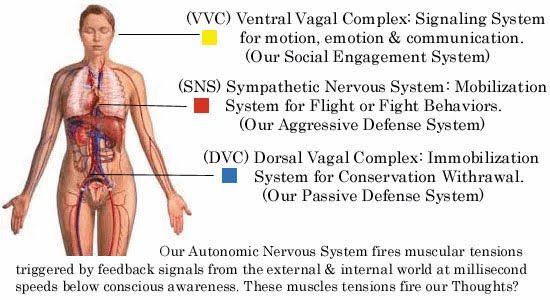

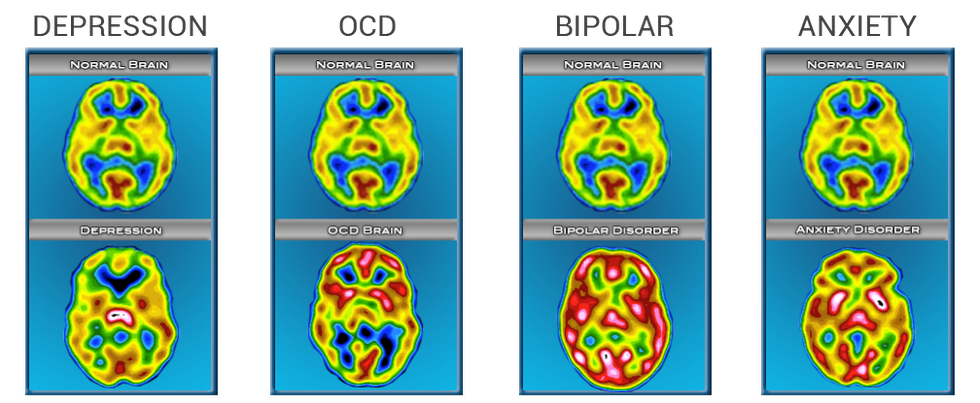

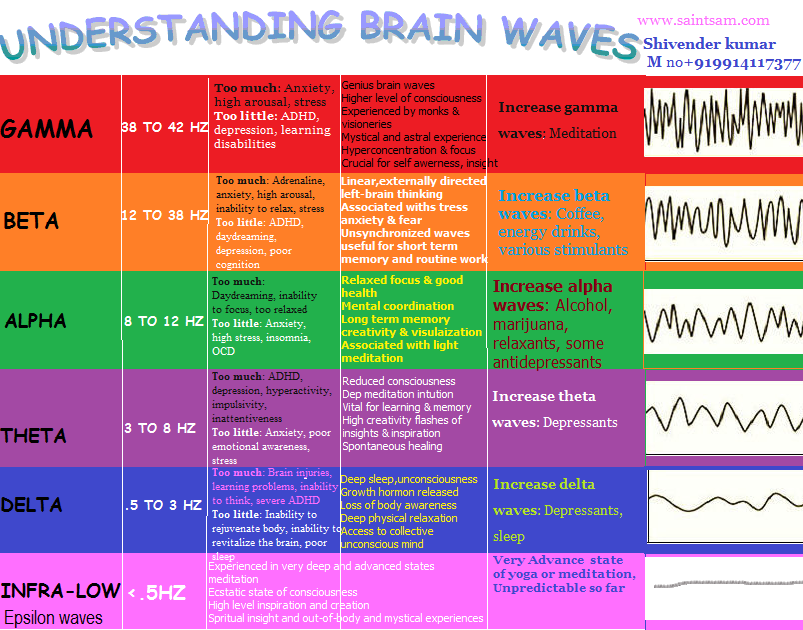

In fact, scientists have found that the same brain regions and neural pathways play an important role in both autism and OCD. Brain scans point to a special role for the striatum, an area of the brain that is associated with motor functions and rewards. Some research suggests that in people with autism and people with OCD, one structure within the striatum, the caudate nucleus, is larger than normal. nine0003

Animal models also suggest a role for the striatum. Winstra-Vanderwil studies autism and OCD with repetitive behavior rodents. He and other scientists found that in both disorders, the animals show abnormalities in the neural circuitry that runs through the striatum and plays a key role in how we start and stop behavior, as well as influencing habit formation.

Another area of research is related to interneurons, which often suppress impulses between cells. If the interneurons in the striatum of mice are disrupted, this leads to twitching, anxiety, and repetitive behavior that resembles OCD and Tourette's syndrome. nine0003

In male mice, the impact on the functioning of interneurons also leads to a sharp decrease in sociability, which, to some extent, may resemble autism. "Unexpectedly, mice also developed social deficits identical to those we see in animal models of autism," says Christopher Pittenger, director of the OCD Research Clinic at Yale University, who led the work. For this reason, he says, interneurons could be a target for both OCD and autism treatments. nine0003

This connection at the level of neural pathways may reflect common genetic causes. A 2015 Danish study found that people with autism were more likely to have relatives with OCD than people in a control group. However, genetic comparisons of the two disorders have shown conflicting results at this stage, which may be due to the fact that very little is known about genetic factors in OCD. “As embarrassing as it is to admit, we know a lot more about the genetics of autism than we do about the genetics of OCD,” says Pittenger. A similar gap may explain why a 2018 meta-analysis of genome studies of more than 200,000 people with 25 disorders, including autism and OCD, found no common gene variants for OCD and autism. nine0003

“As embarrassing as it is to admit, we know a lot more about the genetics of autism than we do about the genetics of OCD,” says Pittenger. A similar gap may explain why a 2018 meta-analysis of genome studies of more than 200,000 people with 25 disorders, including autism and OCD, found no common gene variants for OCD and autism. nine0003

Unpublished work by another research group suggests that rare “de novo mutations,” that is, spontaneous mutations that neither parent has, significantly increase the risk of autism and OCD. Some of the genes that researchers have linked to both diagnoses are related to the immune system. This suggests that interactions between environmental factors and the immune system may play a role. Another gene from the general list, CHD8, regulates gene expression. nine0003

Treatment adaptation

Until scientists can combine all the data from the preliminary studies, no new drugs can be expected. But there are other methods that can help people with both disorders.

On a chilly December evening, people from all over the UK join the OCD & Autism Support Group, a monthly online conference organized by OCD Action, a British charity that helps people with OCD. The number of group members varies greatly during each meeting, but this evening, a few days before Christmas, only four people called. nine0003

During the meeting, a woman named Michelle (only given names in the group) explains that she cannot leave the house unless she makes sure all the lights and appliances are turned off. Thomas spends several hours a day showering. Both of them talk about social difficulties and how they make them anxious. They often worry about what other people think of them, and whether others find their behavior related to OCD or autism strange.

Like most support groups, calling together helps participants feel they are not alone. They also share new information and tips, such as how to use a timer to reduce the time spent washing your hands. Three of the participants mention cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which can help people better understand and manage their obsessive thoughts and actions. As with other forms of psychotherapy that rely on dialogue, it may not be effective for people with autism. For example, such psychotherapy did not help Slavin. nine0003

As with other forms of psychotherapy that rely on dialogue, it may not be effective for people with autism. For example, such psychotherapy did not help Slavin. nine0003

He suspects that he was unable to follow the therapist's methods because of his difficulty with listening to speech and lack of mental flexibility, which he attributes to autism. “Many people on the autism spectrum find it difficult to imagine the situation and how it could lead to a different outcome, so traditional CBT doesn't always work,” he says. Instead, Slavin controls OCD with varying degrees of success with antidepressants.

Some researchers are trying to adapt CBT for people with autism, such as "making sure everyone can see and appreciate their own emotional state," says Russell. Together with her colleagues at King's College London, Russell found in a preliminary study that modified methods may help some adults with autism and OCD manage their anxiety. In January of this year, she and her colleagues, building on the success of the subsequent larger study, developed a clinical guideline. nine0003

People with autism and OCD can also benefit from a more personalized approach to cognitive behavioral therapy. For example, possible schemes might include parent participation in counseling, language facilitation according to the person's language ability, use of visual support and rewards. One clinical trial compared this adapted therapy with standard CBT in more than 160 children with autism and OCD. As yet unpublished results suggest that standard CBT may be beneficial, but an individualized approach works best. nine0003

It seems to Slavin that a more individual approach to treatment can be successful, but he himself has not tried such approaches. Working with organizations that help people with OCD and people with autism, he began to appreciate the diversity of people with both disorders. “It feels like every single person needs their own diagnosis, their own category, because everyone is so different,” he says.

Ten years after being diagnosed with autism, Slavin wants to share his experience, also in order to combat the lack of resources he has faced. In 2010, he opened a website and started a YouTube channel where he talks about what he has learned about living with autism. nine0003

In 2010, he opened a website and started a YouTube channel where he talks about what he has learned about living with autism. nine0003

“I just think of autism as a certain set of circumstances that you can use to your advantage and say, 'OK, I'm going to forgive myself if I don't quite understand how other people act,'” says Slavin. “You can even find joy in your oddities and differences from others ... But OCD, there is nothing good about it at all.”

In October he published a book on his progress. So far, the title of the book sounds like "The search for the norm."

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button. nine0003

Research, Psychiatry, Comorbidities

Obsessive-compulsive disorder - what is it. Symptoms and basic principles of treatment for OCD

Doctors Reviews

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a condition characterized by obsessions and compulsions (recurring behaviors or rituals).

Obsessions are repetitive thoughts, images or urges that a person at the initial stage of the disease himself evaluates as obsessive or unfounded; later they cause him anxiety or guilt. The most common obsession concerns infections (the threat of infection) and tends to wash hands unnecessarily frequently. nine0003

Obsessions can also come from the fear of causing misfortune, injury, or accident, such as leaving the house unlocked or forgetting to turn off the gas. People with OCD feel compelled to reexamine themselves repeatedly. Intrusive thoughts related to violence, murder, blasphemy, or sex are also driven by the fear of harm.

Obsessive actions or rituals (compulsions) are actions that people are forced to purposefully repeat in order to try to reduce their psychological discomfort or avoid it. Most common compulsions: nine0003

- frequent checks to prevent potential hazards;

- excessive brushing or washing of hands;

- re-search for confirmation;

- re-counting or touching to reduce the risk of disaster;

- organizing or ordering objects or activities;

- repeatedly asking questions or talking about one's actions;

- storage of useless or worn-out property.

nine0121

nine0121

Leave a request for a consultation

and our specialist will contact you at any time convenient for you

Our doctors

Abdulova Laysan Rustamovna

Psychiatrist

Specialist experience over

2 years

Arbuzov Igor Evgenievich

Psychiatrist

Specialist experience over

8 years

Bazanova Irina Sergeevna

Psychiatrist

Specialist experience over

2 years

Bykovskaya Anna Vladimirovna

Psychiatrist

Specialist experience over

1 year

Zuikova Nadezhda Leonidovna

Psychotherapist

Specialist experience over

34 years

Kakadzhikova Jamal Guychgeldiyevna

Psychiatrist

Komova Alexandra Vladimirovna

Psychiatrist

Specialist experience over

1 year

Korobkova Irina Grigorievna

Psychiatrist

Specialist experience over

9 years

Korobushkina Natalya Valerievna

Psychiatrist

Specialist experience over

3 years

Mikhailova Zoya Igorevna

Psychiatrist

Specialist experience over

5 years

Parshakova Ekaterina Sergeevna

Psychiatrist

Salamanov Pavel Aleksandrovich

Neurologist

Specialist experience over

2 years

Sarycheva Anna Aleksandrovna

Psychiatrist

Tsyganova Anna Sergeevna

Psychiatrist

Comprehensive diagnostics

in 3 days

Diagnostic and treatment programs for anxiety, depression

and sleep disorders in our hospital

Read more>>>

Reviews

Read all reviews

Nadezhda Leonidovna thank you for being you! thanks to you, life is changing for the better, I admire in . ..

..

December 2, 2021

Before meeting with Nadezhda Leonidovna, I did not believe that psychotherapy could help to sort out my problem...

December 2, 2021

I came to the psychotherapist Nadezhda Leonidovna Zuykova when it seemed that no one could help me..

December 2, 2021

I regularly receive help from a psychotherapist Nadezhda Leonidovna Zuykova regarding the treatment of depression. U...

December 2, 2021

I recognized Nadezhda Leonidovna as a wonderful specialist who is in love with her job. Excellent orientation...

December 2, 2021

I thank Irina Grigoryevna for her sensitivity, attention, professionalism and kindness.

December 2, 2021

Good doctor

December 2, 2021

- Mon-Fri 8:00-21:00

- Sat8:30-21:00

- Sun 9:00-21:00

Open today

until 21:00

Moscow, Generala Karbysheva boulevard, 13, bldg.