Fluoxetine dosage for ocd

[Value of fluoxetine in obsessive-compulsive disorder in the adult: review of the literature]

Review

. 2001 May-Jun;27(3):280-9.

[Article in French]

B Etain 1 , E Bonnet-Perrin

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 Service de psychiatrie, HIA Percy, 101, avenue Henri Barbusse, 92141 Clamart.

- PMID: 11488259

Review

[Article in French]

B Etain et al. Encephale. 2001 May-Jun.

. 2001 May-Jun;27(3):280-9.

Authors

B Etain 1 , E Bonnet-Perrin

Affiliation

-

1 Service de psychiatrie, HIA Percy, 101, avenue Henri Barbusse, 92141 Clamart.

- PMID: 11488259

Abstract

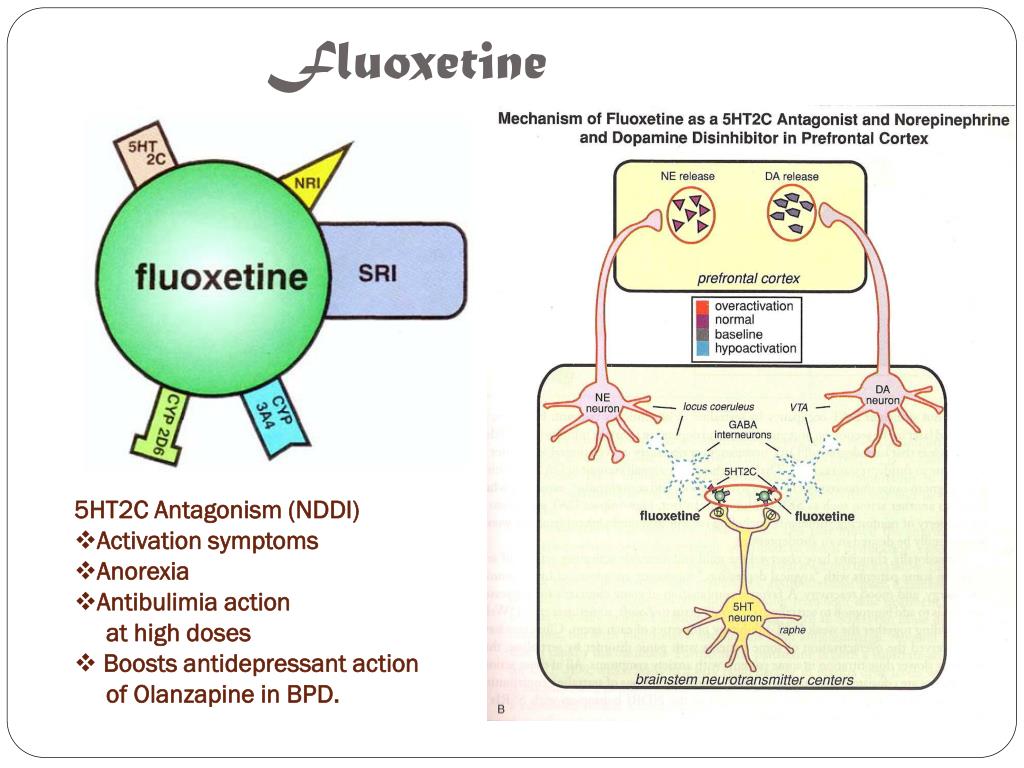

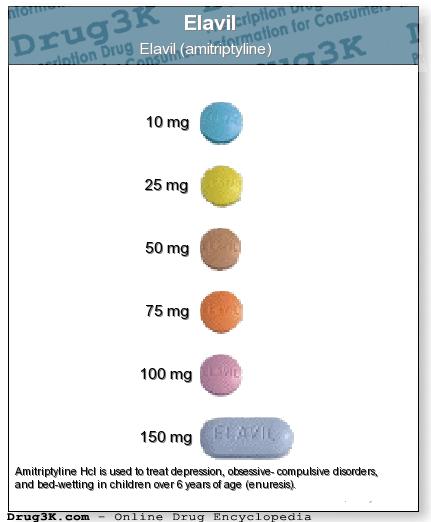

Fluoxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) with demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of major depressive episodes. Since 1985, it has been evaluated for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The orbitofrontal cortex and caudate nucleus are cerebral structures believed to be involved in the pathogenesis of OCD, since hyperactivation of these territories in the basal state is corrected upon remission of symptoms induced by therapy with an SSRI or by behavioral psychotherapy. Furthermore, several studies have found abnormalities in serotoninergic transmission in the orbitofrontal cortex and SSRIs can increase serotonin release by desensitizing 5HTID autoreceptors. OCD is a severe, chronic psychiatric disorder frequently complicated by depressive episodes. Here we review the clinical trials of fluoxetine listed in the Medline and Embase computerized databases. Fluoxetine was found to be effective in OCD in all the published open-label studies as well as in placebo-controlled trials with an effective dose range of 40 to 60 mg daily. Clinical evaluation was carried out by using specific scales such as the Y-BOCS or NIMH-OC and improvement was observed after several weeks of therapy. These studies comprising an extended phase showed that efficacy was maintained--for three years in the longest study--resulting in a higher percentage of responders relative to the treatment initiation phase. A comparison of fluoxetine and clomipramine showed comparable efficacy and a superior safety profile, both in terms of anticholinergic side effects and cardiotoxicity or overdosage. The relapse rate was similar with both drugs. In the four meta-analyses appearing in the databases, two studies found similar efficacy for clomipramine and fluoxetine. There are few studies which directly compare the different SSRIs, apart from a comparison of fluoxetine and sertraline showing that both drugs have similar efficacy.

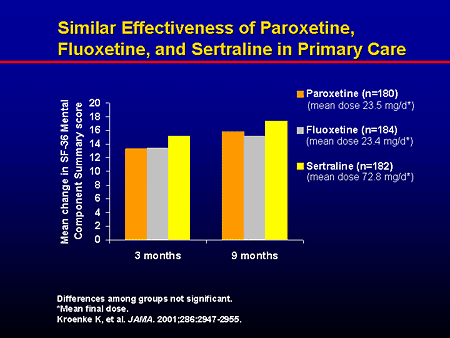

Here we review the clinical trials of fluoxetine listed in the Medline and Embase computerized databases. Fluoxetine was found to be effective in OCD in all the published open-label studies as well as in placebo-controlled trials with an effective dose range of 40 to 60 mg daily. Clinical evaluation was carried out by using specific scales such as the Y-BOCS or NIMH-OC and improvement was observed after several weeks of therapy. These studies comprising an extended phase showed that efficacy was maintained--for three years in the longest study--resulting in a higher percentage of responders relative to the treatment initiation phase. A comparison of fluoxetine and clomipramine showed comparable efficacy and a superior safety profile, both in terms of anticholinergic side effects and cardiotoxicity or overdosage. The relapse rate was similar with both drugs. In the four meta-analyses appearing in the databases, two studies found similar efficacy for clomipramine and fluoxetine. There are few studies which directly compare the different SSRIs, apart from a comparison of fluoxetine and sertraline showing that both drugs have similar efficacy. With clomipramine, the SSRIs represent the first-line treatment recommended by the experts, in association with behavioral therapy to improve and maintain the clinical response over the long term. The guidelines recommend an optimal fluoxetine dose of 40 to 60 mg daily with a minimum treatment duration of 1 to 2 years. Efficacy should not be evaluated before 8 weeks to allow for onset of the therapeutic effects. Fluoxetine was found to have a good safety profile in these studies and the adverse effects described (insomnia, headache, diminished libido) rarely led to discontinuation of the treatment. Adverse effects such as nervousness or insomnia at the start of therapy were predictors of a good response to fluoxetine, as were the presence of remissions, the absence of prior pharmacologic therapy and a high impulsiveness score. A long history of the disorder, severity of the symptoms, collection obsessions, washing compulsions, obsessional slowness and comorbidity with a schizotypic personality or vocal or motor tics were associated with a poorer response.

With clomipramine, the SSRIs represent the first-line treatment recommended by the experts, in association with behavioral therapy to improve and maintain the clinical response over the long term. The guidelines recommend an optimal fluoxetine dose of 40 to 60 mg daily with a minimum treatment duration of 1 to 2 years. Efficacy should not be evaluated before 8 weeks to allow for onset of the therapeutic effects. Fluoxetine was found to have a good safety profile in these studies and the adverse effects described (insomnia, headache, diminished libido) rarely led to discontinuation of the treatment. Adverse effects such as nervousness or insomnia at the start of therapy were predictors of a good response to fluoxetine, as were the presence of remissions, the absence of prior pharmacologic therapy and a high impulsiveness score. A long history of the disorder, severity of the symptoms, collection obsessions, washing compulsions, obsessional slowness and comorbidity with a schizotypic personality or vocal or motor tics were associated with a poorer response. Fluoxetine also alleviates collateral depressive symptoms by significantly reducing suicidal ideation and impulsiveness in OCD patients. Our study indicates that fluoxetine is effective and well tolerated in OCD, placing it among the first-line treatments recommended by consensus conference guidelines.

Fluoxetine also alleviates collateral depressive symptoms by significantly reducing suicidal ideation and impulsiveness in OCD patients. Our study indicates that fluoxetine is effective and well tolerated in OCD, placing it among the first-line treatments recommended by consensus conference guidelines.

Similar articles

-

Continuation treatment of OCD: double-blind and open-label experience with fluoxetine.

Tollefson GD, Birkett M, Koran L, Genduso L. Tollefson GD, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994 Oct;55 Suppl:69-76; discussion 77-8. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994. PMID: 7961535 Clinical Trial.

-

Predictors of drug treatment response in obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Ravizza L, Barzega G, Bellino S, Bogetto F, Maina G.

Ravizza L, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995 Aug;56(8):368-73. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995. PMID: 7635854 Clinical Trial.

Ravizza L, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995 Aug;56(8):368-73. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995. PMID: 7635854 Clinical Trial. -

[Prospective follow-up over a 12 month period of a cohort of 155 patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: phase III National DRT-TOC Study].

Hantouche EG, Bouhassira M, Lancrenon S. Hantouche EG, et al. Encephale. 2000 Nov-Dec;26(6):73-83. Encephale. 2000. PMID: 11217541 French.

-

[Efficacy and tolerability of escitalopram in anxiety disorders: a review].

Pelissolo A. Pelissolo A. Encephale. 2008 Sep;34(4):400-8. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2008.04.004. Epub 2008 Aug 15. Encephale. 2008. PMID: 18922243 Review. French.

-

Pharmacologic treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: comparative studies.

Flament MF, Bisserbe JC. Flament MF, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58 Suppl 12:18-22. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997. PMID: 9393392 Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Fluoxetine for the treatment of onychotillomania associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a case report.

Aljhani S. Aljhani S. J Med Case Rep. 2022 Nov 20;16(1):431. doi: 10.1186/s13256-022-03652-9. J Med Case Rep. 2022. PMID: 36403006 Free PMC article.

-

Developmental fluoxetine exposure in zebrafish reduces offspring basal cortisol concentration via life stage-dependent maternal transmission.

Martinez R, Vera-Chang MN, Haddad M, Zon J, Navarro-Martin L, Trudeau VL, Mennigen JA.

Martinez R, et al. PLoS One. 2019 Feb 21;14(2):e0212577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212577. eCollection 2019. PLoS One. 2019. PMID: 30789953 Free PMC article.

Martinez R, et al. PLoS One. 2019 Feb 21;14(2):e0212577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212577. eCollection 2019. PLoS One. 2019. PMID: 30789953 Free PMC article. -

Idiopathic basal ganglia calcification presenting as schizophrenia-like psychosis and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: A case report.

Pan B, Liu W, Chen Q, Zheng L, Bao Y, Li H, Yu R. Pan B, et al. Exp Ther Med. 2015 Aug;10(2):608-610. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2525. Epub 2015 May 27. Exp Ther Med. 2015. PMID: 26622362 Free PMC article.

-

Optimal dosages of fluoxetine in the treatment of hypoxic brain injury induced by 3-nitropropionic acid: implications for the adjunctive treatment of patients after acute ischemic stroke.

Zhu BG, Sun Y, Sun ZQ, Yang G, Zhou CH, Zhu RS.

Zhu BG, et al. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012 Jul;18(7):530-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00315.x. Epub 2012 Apr 19. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012. PMID: 22515819 Free PMC article.

Zhu BG, et al. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012 Jul;18(7):530-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00315.x. Epub 2012 Apr 19. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012. PMID: 22515819 Free PMC article.

Publication types

MeSH terms

Substances

Optimal Dose of Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Adults: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis

Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by obsessions (recurrent, intrusive thoughts, images, or impulses) and/or compulsions (behaviors or mental actions taken repeatedly to decrease anxiety) (1). OCD is one of the 10 most debilitating physical and mental disorders (2) with a lifelong prevalence of 2–3% in the general population (3–6). Researchers have made efforts for several decades to improve the identification of effective treatments, including psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and combined treatments. Based on the data of clinical trials, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) were recommended as mainstream treatments for OCD for both safety and effectiveness (7). In terms of pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive meta-analysis (8) indicated that SRIs, such as tricyclic antidepressants, clomipramine, and some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), were highly efficacious for OCD. Later, a Cochrane review (9) corroborated the efficacy of all SSRIs (including citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline), with no reliable differences. Clomipramine was consistently proven to be as effective or as even slightly better than SSRIs in the treatment of OCD, despite its less favorable side effects (10–13). Previous evidence revealed that clomipramine had anticholinergic side effects, such as dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, fatigue, tremor, hyperhidrosis, and an increased risk of arrhythmias and seizures with daily doses >200 mg, which were rarely seen in SSRI therapy (14).

Researchers have made efforts for several decades to improve the identification of effective treatments, including psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and combined treatments. Based on the data of clinical trials, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) were recommended as mainstream treatments for OCD for both safety and effectiveness (7). In terms of pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive meta-analysis (8) indicated that SRIs, such as tricyclic antidepressants, clomipramine, and some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), were highly efficacious for OCD. Later, a Cochrane review (9) corroborated the efficacy of all SSRIs (including citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline), with no reliable differences. Clomipramine was consistently proven to be as effective or as even slightly better than SSRIs in the treatment of OCD, despite its less favorable side effects (10–13). Previous evidence revealed that clomipramine had anticholinergic side effects, such as dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, fatigue, tremor, hyperhidrosis, and an increased risk of arrhythmias and seizures with daily doses >200 mg, which were rarely seen in SSRI therapy (14). Nevertheless, a recent review suggested that SSRIs (specifically fluoxetine) were the antidepressants most associated with manic/hypomanic episodes across the entire subjects, but no significant differences were found in clomipramine (15).

Nevertheless, a recent review suggested that SSRIs (specifically fluoxetine) were the antidepressants most associated with manic/hypomanic episodes across the entire subjects, but no significant differences were found in clomipramine (15).

However, there were still some controversies over the dose dependency and optimal target dose of SRIs. Higher and rapidly increased SRI doses were recommended by many OCD experts when treating OCD compared with other conditions, such as anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder (14, 16). Similarly, American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines recommended a higher target dose for OCD than depression (7). Moreover, patients who failed to respond positively to multiple SSRIs at the maximum tolerated dose for a sufficient duration (at least 2 months) were diagnosed with treatment-resistant refractory OCD (16). Therefore, compared with many other mental disorders, patients with OCD were treated with SSRIs at higher doses before receiving replacement or augmentation therapies (17). Nevertheless, controlled trials have not reached consistent conclusions as to whether higher doses of SSRIs can lead to beneficial therapeutic effects, since they may carry a higher burden of side effects for patients at the same time. Some fixed-dose studies showed that higher doses of SRIs could provide better treatment efficacy (18–21), while some did not (22, 23). Bloch et al. (17) reported that higher doses of SSRIs were more effective when treating adults with OCD and were associated with a significant increase in the proportion of people who dropped out due to side effects, but the dose of SSRI was independent of the total number of all-cause dropout. Studies on a fixed dose of clomipramine for OCD treatment were rare, and the dose–response relationship was unclear.

Nevertheless, controlled trials have not reached consistent conclusions as to whether higher doses of SSRIs can lead to beneficial therapeutic effects, since they may carry a higher burden of side effects for patients at the same time. Some fixed-dose studies showed that higher doses of SRIs could provide better treatment efficacy (18–21), while some did not (22, 23). Bloch et al. (17) reported that higher doses of SSRIs were more effective when treating adults with OCD and were associated with a significant increase in the proportion of people who dropped out due to side effects, but the dose of SSRI was independent of the total number of all-cause dropout. Studies on a fixed dose of clomipramine for OCD treatment were rare, and the dose–response relationship was unclear.

To sum up, available reviews about the dose dependency of SRIs were scarce and the evidence was inconsistent. Given this, we conducted a dose–response meta-analysis of fixed-dose studies of commonly used antidepressants, including clomipramine and all of the SSRIs for the treatment of adults diagnosed with OCD, to further define the dose–response relationship of SRIs and give more insights into the optimal dose of SRIs for OCD.

Methods

Search Strategy

The meta-analysis was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (24). The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (number CRD42020168344). MEDLINE, Embase, Biosis, PsycINFO, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Web of Science, and CINAHL were searched without restrictions of language from database inception to February 22, 2020. Search strategies of the study combined terms “obsessive compulsive disorder” and “citalopram or escitalopram or fluoxetine or fluvoxamine or paroxetine or sertraline or clomipramine” (Appendix 1). In addition, we also manually screened the relevant reviews in the reference list to find additional studies.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Single- or double-blind, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included to compare antidepressants among themselves or with placebo as oral monotherapy for the acute-phase treatment of adults (aged 18 years or older), with an initial diagnosis of OCD according to standard operationalized diagnostic criteria. We excluded trials of antidepressants for patients with OCD and severe concomitant physical conditions. Studies of patients with treatment resistance, concomitant serious medical illnesses, and relapse-prevention studies were also excluded. The study focused on the most commonly used antidepressants, mainly SRIs such as clomipramine, and SSRIs.

We excluded trials of antidepressants for patients with OCD and severe concomitant physical conditions. Studies of patients with treatment resistance, concomitant serious medical illnesses, and relapse-prevention studies were also excluded. The study focused on the most commonly used antidepressants, mainly SRIs such as clomipramine, and SSRIs.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers (JX and QH) screened the search results and retrieved full-text articles independently. In case of doubt, a third reviewer (QW) participated. Three reviewers (JX, QH, and MX) performed data extraction independently, using a standard data extraction form in Microsoft Excel 2010. This included verifying study eligibility, sample size, age (mean, SD, and range), average duration of OCD (mean and SD), gender, comorbidity, diagnostic criteria, treatment time, active agent and dose, outcomes (primary and secondary measures), reported statistics, length of follow-up, and number of participants lost and excluded at each stage of the trial. For conflicting data entries, reviewers performed algorithm checks. Differences were discussed, and if no consensus was reached, we turned to another examiner (QW). If the information was missing or unclear, the study authors were contacted.

For conflicting data entries, reviewers performed algorithm checks. Differences were discussed, and if no consensus was reached, we turned to another examiner (QW). If the information was missing or unclear, the study authors were contacted.

Risk of Bias Across Studies

We used Cochrane Collaboration's risk-of-bias tool to insert figures to independently assess the risk of bias in the main results of RCTs (25) and evaluated the risk of bias in allocation sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of researchers and participants, blinding of result evaluators, selective outcome reporting, and other bias. If none of these areas were rated as high risk of bias and no more than three areas were rated as unclear risk, then this study was classified as low risk of bias; if one area was rated as high risk of bias or no one was rated as high risk of bias but more than three areas were rated as unclear risk, then this study was rated as moderate risk of bias; and all other cases were considered to have high risk of bias (26, 27). We conducted funnel plots to supervise the reporting bias (Appendix 2). If the funnel plot was symmetric, there may be no bias (28).

We conducted funnel plots to supervise the reporting bias (Appendix 2). If the funnel plot was symmetric, there may be no bias (28).

Test of Heterogeneity

We performed statistical analysis by Review Manager Program Version 5.3 and STATA version 15, and statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p < 0.05. Heterogeneity was tested by Q test among studies and was evaluated by p-value and I2 value. When p > 0.1 and I2 ≤ 50%, it is considered that there is no obvious heterogeneity between the studies, and the fixed-effect model is selected; when p < 0.1 and I2 ≤ 50%, the heterogeneity is acceptable, and the fixed effect is the selected model; and p < 0.1 with I2 > 50% suggested that there is obvious heterogeneity between the studies. It is necessary to analyze the causes of the heterogeneity, carry out sensitivity analysis, and then select the random effects model. Publication bias was evaluated by means of the Egger's test (Appendix 2).

Publication bias was evaluated by means of the Egger's test (Appendix 2).

Outcomes

The following outcomes were included after 10 weeks of treatment (range 8–13 weeks): (1) the primary outcome is the mean difference measured by the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS). (2) The secondary outcomes are dropouts due to all causes, which was interpreted as an overall indicator of treatment acceptability, and discontinuations due to adverse effects, as an indicator of treatment tolerability.

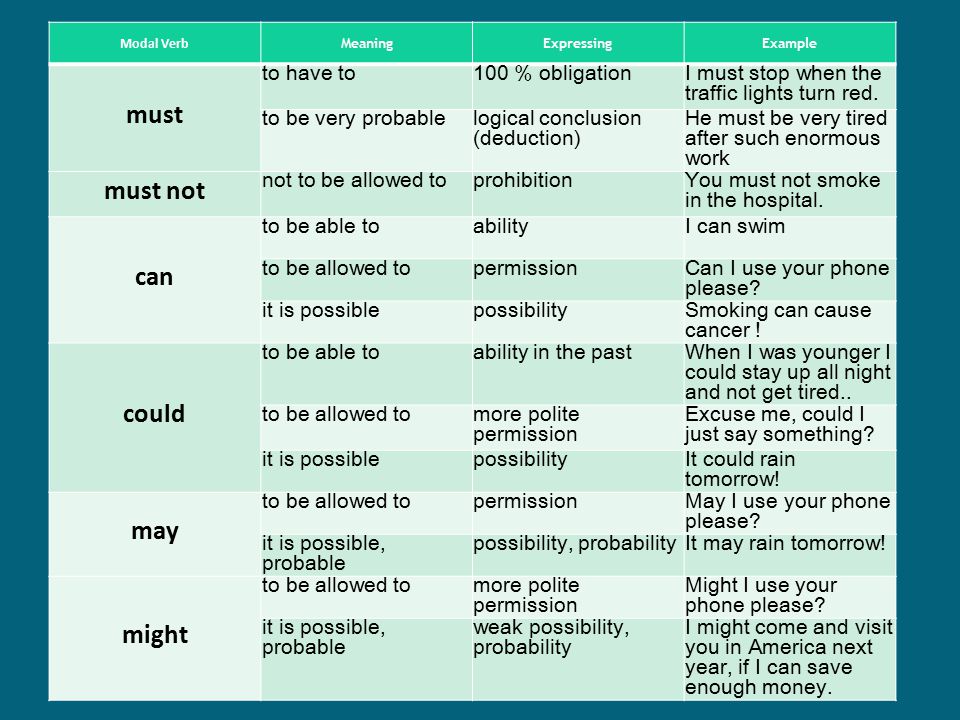

Dose Conversion Across Drugs

Dose equivalent can be calculated in different ways (29). One method using flexible doses in double-blind studies assumed the optimum doses to be equivalent (30). In this review, we adopted the method of Hayasaka and colleagues for the main analysis (31). Previous studies of SRIs' dose dependence used similar conversion algorithms (32, 33). In the absence of empirical data on dose conversion, we presumed that the daily defined dose (34) was equal. The dose conversion algorithms are shown in Table 1.

The dose conversion algorithms are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Antidepressant dose equivalence (mg) according to previous studies.

Data Analyses

Studies of all SRIs were synthesized to estimate the dose dependence of the three main outcomes. We used the method of Hayasaka and colleagues to convert the doses to fluoxetine equivalents (31), with the daily defined dose method (34) as supplementary. In this analysis, we utilized a one-stage, robust error meta-regression (REMR) model to handle the synthesis of relevant dose–response data from different studies (35). This was done by setting three fixed knots at the 5, 50, and 95 quartiles or setting three random knots on the quartiles of the dose distribution) (36). The one-stage REMR approach was executed in STATA software package (version 15.1). Such approach estimates the association between the dose and mean difference (MD) for the primary outcome, the dose and the risk ratio (RR) for the second outcomes, side-effect-related dropouts, and all-cause dropouts, considering that the heterogeneity, within and across studies, was applied simultaneously in a single model.

The following sensitivity analyses were performed to test the robustness of the major findings: (1) set different doses and numbers of knots and (2) apply the latest daily defined dose conversion algorithm (34) (Appendix 2).

Role of the Funding Source

The sponsor did not participate in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of this manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all data in this study and was ultimately responsible for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Study Selection

As described in Figure 1, we identified 10,130 published records through automatic search, manual search, and contact with authors and retrieved 77 full-text articles after excluding 6,655 reports based on titles and abstracts. We screened these articles and eventually included 11 studies with 2,322 participants. The inter-rater agreement was evaluated in the two stages of screening and full-text review, and Cohen's κ were 0. 84 and 0.95, respectively. There was no language restriction in the retrieval process. Among the 11 articles, there were one Japanese and 10 English articles. The heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis of the Japanese article showed no difference. The 11 studies included 35 treatment groups: eight for placebo, three for citalopram, two for escitalopram, seven for fluoxetine, four for paroxetine, six for sertraline, and two for clomipramine. Six of the studies had four treatment groups, one had three treatment groups, and four had two treatment groups. The median length of the trials was 10 weeks (ranging from 8 to 13 weeks). The characteristics of the sample were as follows: (1) the mean age was 37.13 years (SD 3.68), and (2) 1,142 (49.1%) of 2,322 participants were women. See Appendix 3 for the characteristics of the included studies.

84 and 0.95, respectively. There was no language restriction in the retrieval process. Among the 11 articles, there were one Japanese and 10 English articles. The heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis of the Japanese article showed no difference. The 11 studies included 35 treatment groups: eight for placebo, three for citalopram, two for escitalopram, seven for fluoxetine, four for paroxetine, six for sertraline, and two for clomipramine. Six of the studies had four treatment groups, one had three treatment groups, and four had two treatment groups. The median length of the trials was 10 weeks (ranging from 8 to 13 weeks). The characteristics of the sample were as follows: (1) the mean age was 37.13 years (SD 3.68), and (2) 1,142 (49.1%) of 2,322 participants were women. See Appendix 3 for the characteristics of the included studies.

Figure 1. The flowchart of study selection.

Risk of Bias Within Studies

The risk of bias of the 11 included studies are shown in Figure 2, and the risk-of-bias assessment for the individual domains is shown in Figure 3. We excluded studies with high risk of bias. Generally, the methods of random sequence generation and allocation concealment were not depicted in detail, so they were encoded as unclear. Some studies with very small sample sizes which were not sure about other biases were also coded as unclear. The percentages of the individual domains with high, unclear, and low risks of bias in the risk assessment were as follows: 0, 72.7, and 27.3% for randomization, 0, 54.5, and 45.5% for allocation concealment, 9.1, 0, and 90.9% for blinding toward patients and researchers, 0, 0, and 100% for masking of outcome assessment, 0, 0, and 100% for incomplete outcomes, 0, 0, and 100% for selective reporting, and 0, 27.3, and 72.7% for other biases. The results of the overall bias risk rating were as follows: 10 studies (91%) had low risks of bias, 1 study (9%) had a medium risk of bias, and no study had a high risk of bias.

We excluded studies with high risk of bias. Generally, the methods of random sequence generation and allocation concealment were not depicted in detail, so they were encoded as unclear. Some studies with very small sample sizes which were not sure about other biases were also coded as unclear. The percentages of the individual domains with high, unclear, and low risks of bias in the risk assessment were as follows: 0, 72.7, and 27.3% for randomization, 0, 54.5, and 45.5% for allocation concealment, 9.1, 0, and 90.9% for blinding toward patients and researchers, 0, 0, and 100% for masking of outcome assessment, 0, 0, and 100% for incomplete outcomes, 0, 0, and 100% for selective reporting, and 0, 27.3, and 72.7% for other biases. The results of the overall bias risk rating were as follows: 10 studies (91%) had low risks of bias, 1 study (9%) had a medium risk of bias, and no study had a high risk of bias.

Figure 2. Summary of risk bias in clinical controlled trials of SRIs in OCD adults. Green circles, low risk of bias; yellow circles, unclear risk of bias; red circles, high risk of bias.

Green circles, low risk of bias; yellow circles, unclear risk of bias; red circles, high risk of bias.

Figure 3. The risk of bias assessment for the individual domains.

Synthesis of Results

Due to lack of partial data, nine, seven, and six literatures were included into the dose efficacy and dose dropout due to adverse effects and the dose dropout for all-cause analyses, respectively. Thus, the dose range was slightly different in the analysis. Table 2 displays the suggested start dose, usual maximum doses, and maximum doses occasionally prescribed for each SRI in OCD according to the American Psychiatric Association (APA) dose recommendations (7). The dose–response relationships for SRIs after dose equivalent conversion are presented in Figure 4. Furthermore, we removed the studies of clomipramine and analyzed the dose–outcome relationships for SSRIs and the results are presented in Figure 5.

Table 2. Dosing of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in OCD.![]()

Figure 4. Dose–outcome relationships for serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) in two dose conversion algorithms. RR, risk ratio. The dotted lines represent 95% CIs. (A–C) were the dose–outcome plots using the conversion method of Hayasaka et al. (31). (D–F) were the dose–outcome plots using the conversion method of defined daily dose. (A) Dose–efficacy relationship for SRIs. (B) Dose dropout due to adverse effects relationships for SRIs. (C) Dose dropout from all causes of relationships for SRIs. (D) Dose–efficacy relationships for SRIs. (E) Dose dropout due to adverse effects relationships for SRIs. (F) Dose–dropout from all causes relationships for SRIs.

Figure 5. Dose–outcome relationships for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The studies for clomipramine were removed, and the rest were all for SSRIs. The dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals. (A) Dose–efficacy relationship for SRIs. (B) Dose dropout due to adverse effects relationships for SRIs. (C) Dose dropout from all causes relationships for SRIs.

The dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals. (A) Dose–efficacy relationship for SRIs. (B) Dose dropout due to adverse effects relationships for SRIs. (C) Dose dropout from all causes relationships for SRIs.

Efficacy

We used MD measured by the Y-BOCS as an index of efficacy. It can be seen from the dose–efficacy curves (Figures 4A,D) that the best efficacy was achieved when the equivalent dose of fluoxetine was about 40 mg. Thus, it can be concluded that within the dose range of 0–100 mg fluoxetine equivalent, about 40 mg was the optimal dose of SRIs for efficacy. Considering the efficacy result of SRIs vs. placebo, no significant heterogeneity was observed in the aggregated mean change of Y-BOCS. The pooled mean change in the SRI-treated group for the Y-BOCS was significantly greater than that in the placebo treatment group, with MD of −3.67 (95% CI, −4.67, −2.68; I2 = 21%) (Appendix 2). Due to limited evidence, we could not estimate the dose efficacy of individual SRI in the treatment of adult OCD.

Tolerability

We used dropouts due to adverse effects as an indicator of tolerability. The dose dropout due to adverse-effect curves (Figures 4B,E) showed that RR gradually increased in the dose range of 0–83.7 mg, from 0.95 (95% CI, 0.90, 1.01) for placebo, to 1.46 (95% CI, 1.12–1.80) for 20 mg, 1.81 (95% CI, 1.28–2.34) for 40 mg, 1.91 (95% CI, 1.38–2.43) for 60 mg, and 1.96 (95% CI, 1.22–2.70) for 83.7 mg of fluoxetine equivalent. The relationship between dose and discontinuations due to adverse effects indicates that tolerability decreased with increasing doses within the measured dose range. The point estimates and their 95% CIs of RRs for dropouts due to adverse effects at 0–83.7 mg of fluoxetine equivalents of SRIs are presented in Table 3. There were significant differences in SRI and placebo treatment for adverse events, with RR of 1.77 (95% CI, 1.38–2.28; I2 = 0%) (Appendix 2).

Table 3. RRs for tolerability and acceptability at various doses of SRIs.

Acceptability

The dose–outcome curves (Figures 4C,F) showed that in terms of proportion of dropouts due to any reason, there was no significant tendency. The RR for dropout due to all causes had no significant differences in SRI and placebo treatment. The RR was 1.04 (95% CI, 0.94, 1.14) for placebo, 1.18 (95% CI, 0.99–1·38) for 20 mg, 1.22 (95% CI, 1.00–1.44) for 40 mg, 1.09 (95% CI, 0.77–1.41) for 60 mg, and 0.89 (95% CI, 0.22–1.56) for 83.7 mg of fluoxetine equivalent. The point estimates and their 95% CIs of RRs for dropouts from all causes at 0–83.7 mg of fluoxetine equivalents of SRIs are presented in Table 3. The different SRI dose categories did not differ from placebo or any other in all-cause dropout rates, with a total RR of 1.04 (95% CI, 0.90–1.20; I2 = 32%) (Appendix 2).

Various knots were examined when we plotted splines for the dose–outcome curves of SRIs (Appendix 2), and all the curves overlapped with our primary analyses. When we examined different dose-equivalence calculations by the method of SRI-defined daily dose, all results were similar to the primary results (Figure 4). To explain the residual heterogeneity, we conducted sensitivity analysis by removing the studies on treatment of clomipramine to test the influence of clomipramine. The results were also consistent with the results of SRIs (Figure 5).

To explain the residual heterogeneity, we conducted sensitivity analysis by removing the studies on treatment of clomipramine to test the influence of clomipramine. The results were also consistent with the results of SRIs (Figure 5).

Discussion

Due to rare evidence of the optimal doses of SRIs for OCD, we conducted a systematic analysis to provide conclusive proof. This meta-analysis was the largest (11 RCTs with 2,322 patients) one to investigate the optimal doses of SRIs for OCD. For SRIs, the efficacy increased at the doses from 0 to 40 mg of fluoxetine equivalents, while it did not increase further or even decrease slightly at doses up to 100 mg. Dropouts due to adverse effects showed a gradual increase in the dose range of 0–83.7 mg. However, dropouts due to any reason were not significantly related to the doses of SRIs. These outcomes suggested that the increased burden of side effects and the stagnation of therapeutic efficacy increase limited the use of higher doses of SRIs in OCD.

Data from our study showed that the effectiveness of SRIs was optimal at the fluoxetine equivalent dose of about 40 mg, and the efficacy decreased as the dose increased higher than 40 mg. The result was partially inconsistent with a previous study on SRIs. Using the dose equivalent conversion method of Bollini et al. (32), Bloch et al. (17) divided the SSRI dose into low, medium, and high and observed that there was a stepwise increase in efficacy with dose and all-cause dropouts were not significantly related to SSRI dose. The possible reasons for the difference between decreased efficacy at higher doses (>40 mg) and other mainstream recommendations for higher initial doses of SRIs for OCD (14, 16) were as follows. First, our study used different dose conversion methods, which might lead to different results. Therefore, in order to improve the reliability of the experimental results, the most comprehensive and the latest dose equivalent conversion methods (31, 34) were used in this study. Second, compared with other studies, the dose classification method we used was different. In our study, the dose was treated as a continuous variable and the spline curve model was used for dose–response analysis, so that it is easier to find the turning point. Third, limited studies included in the study, especially those with a higher dose, may result in bias of results. Fourth, all the studies included in this study were fixed-dose studies, and participants with a large initial dose had increased side effects. This may affect the efficacy results, thereby resulting in bias of the dose-efficacy outcome. Last but not least, the short follow-up time (8–13 weeks) included in this study may also have some influence on the outcomes.

Second, compared with other studies, the dose classification method we used was different. In our study, the dose was treated as a continuous variable and the spline curve model was used for dose–response analysis, so that it is easier to find the turning point. Third, limited studies included in the study, especially those with a higher dose, may result in bias of results. Fourth, all the studies included in this study were fixed-dose studies, and participants with a large initial dose had increased side effects. This may affect the efficacy results, thereby resulting in bias of the dose-efficacy outcome. Last but not least, the short follow-up time (8–13 weeks) included in this study may also have some influence on the outcomes.

The result of dropouts due to side effects was consistent with other studies; that is, side effects increased with increasing licensed dose. Although the result of all-cause dropouts was consistent with that of a previous study, causes may differ, since the CI of all RR values for dose–all-cause dropout outcome contains 1, indicating that the dose and dropouts due to all causes had no obvious relationship. Bloch et al. (17) concluded that the efficacy and side effects canceled each other out, so there was no significant correlation between all-cause dropouts and dose.

Bloch et al. (17) concluded that the efficacy and side effects canceled each other out, so there was no significant correlation between all-cause dropouts and dose.

Although both clomipramine and SSRI belong to SRI, their mechanisms of action are different. Clomipramine is a tricyclic antidepressant, which works by inhibiting the reuptake of norepinephrine (NA) and serotonin in the presynaptic membrane. According to previous evidence, the treatment efficacy of clomipramine for OCD is related to its relatively high potency in affecting serotonergic neurotransmission (37). In order to exclude the influence of clomipramine on the research results, clomipramine was removed and analyzed again (Figure 5). The results were found to be completely consistent with the previous results, indicating that clomipramine had no influence on the outcomes. However, there are few studies on clomipramine, which also resulted in certain limitations. More studies are needed to make such conclusion more reliable. In addition, in order to verify the robustness of the results, we set different dose knots and adopted two different dose conversion methods for analysis, and the analysis results were in good agreement.

In addition, in order to verify the robustness of the results, we set different dose knots and adopted two different dose conversion methods for analysis, and the analysis results were in good agreement.

There were some limitations to this meta-analysis. First, the best method to calculate the dose equivalency among antidepressants was not clear. In our study, we adopted the most comprehensive and latest empirically derived conversion algorithms (31, 34) and examined results through sensitivity analyses, in which different conversion algorithms and multiple knots with different doses were applied. Still, it was difficult to avoid bias caused by the conversion pattern. Second, although we searched a lot of databases, there were too few eligible studies observed and available in our meta-analysis to address the dose–response differences between individual SRIs. Therefore, we meta-analyzed SRIs as a whole, because they were all efficacious and shared a key therapeutic mechanism. Third, all studies included in this meta-analysis shared a relatively similar treatment duration of 8–13 weeks, but there were too few trials to examine treatment duration, which influences SRI efficacy. Fourth, fixed-dose regimens may be considered to not reflect clinical practice, especially when rapid titration regimens are not used or used, and discontinuation may be overestimated due to side effects. However, only through a fixed-dose study can the dose dependence be strictly checked. Fifth, although we obtained a lot of literatures through searching, no fixed-dose RCTs conforming to this study have been conducted in the past 10 years, so all studies included in this paper were relatively old. In addition, findings related to the outcomes of SRIs were based on a small number of participants (n = 2,232). Finally, although the funnel plots showed no publication bias, we cannot exclude the possibility of reporting bias because we only included published studies, and the outcomes were not reported in all studies.

Fourth, fixed-dose regimens may be considered to not reflect clinical practice, especially when rapid titration regimens are not used or used, and discontinuation may be overestimated due to side effects. However, only through a fixed-dose study can the dose dependence be strictly checked. Fifth, although we obtained a lot of literatures through searching, no fixed-dose RCTs conforming to this study have been conducted in the past 10 years, so all studies included in this paper were relatively old. In addition, findings related to the outcomes of SRIs were based on a small number of participants (n = 2,232). Finally, although the funnel plots showed no publication bias, we cannot exclude the possibility of reporting bias because we only included published studies, and the outcomes were not reported in all studies.

There are also various highlights in our study. First of all, we included the most advanced dose–response meta-analysis and regarded dose as a continuous variable, so we could better resolve the point of change and avoid misleading dose classification. In addition, we checked not only the dose dependence of the efficacy but also the tolerability and acceptability. Furthermore, we conducted the study based on the largest and most comprehensive fixed-dose, single-blind, or double-blind RCTs of SRIs in the acute-phase treatment of OCD and took not only SSRIs but also a tricyclic antidepressant, clomipramine, into consideration.

In addition, we checked not only the dose dependence of the efficacy but also the tolerability and acceptability. Furthermore, we conducted the study based on the largest and most comprehensive fixed-dose, single-blind, or double-blind RCTs of SRIs in the acute-phase treatment of OCD and took not only SSRIs but also a tricyclic antidepressant, clomipramine, into consideration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our analyses showed that the optimal dose of efficacy was reached at about 40 mg fluoxetine equivalent and tolerability decreased with increased doses within the dose range reviewed, but the overall acceptability of treatments appears to be dose-independent. Therefore, we conclude that for most of the patients receiving an SRI for the acute-phase treatment of OCD, the optimal dose should be achieved based on a balance between efficacy and tolerability. Further large-scale prospective researches are needed to rigorously make clearer the utility of higher doses of SRIs in the treatment of OCD and examine the dose–response relationship in specific populations, such as old or pediatric patients. It is noteworthy that there are few specific fixed-dose studies published concerning children and adolescents with OCD, and it is hoped that researchers will pay attention to this issue and conduct related studies in the future.

It is noteworthy that there are few specific fixed-dose studies published concerning children and adolescents with OCD, and it is hoped that researchers will pay attention to this issue and conduct related studies in the future.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

MX and QW conceptualized and designed the study. JX, QH, and RQ conducted the literature search and summary evaluated the papers for inclusion and exclusion criteria. MX, JX, QH, and MD conducted all statistical analyses and hammered away at methodology. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the manuscript and have approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81771446), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2018YFC1314300). This study was also supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2016YFC1307003).

This study was also supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2016YFC1307003).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Chang Xu for his constructive feedback on the original draft of the manuscript and methodological guidance.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10. 3389/fpsyt.2021.717999/full#supplementary-material

3389/fpsyt.2021.717999/full#supplementary-material

References

1. APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. (2013).

Google Scholar

2. Murray CJ, Lopez AD, Organization WH. The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability From Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020: Summary. World Health Organization (1996).

Google Scholar

3. Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Gloster AT, Lieb R. Obsessive–compulsive disorder in the community: 12-month prevalence, comorbidity and impairment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2011) 47:339–49. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0337-5

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Kessler RC. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. (2008) 15:53–63. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.94

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2005) 62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2005) 62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Vaingankar JA, Chong SA. Obsessive–compulsive disorder: prevalence, correlates, help-seeking and quality of life in a multiracial Asian population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2012) 47:2035–43. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0507-8

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Koran LM, Hanna GL, Hollander E, Nestadt G, Simpson HBJAJP. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (2007) 164(7Suppl.):5–53.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

8. Eddy KT, Dutra L, Bradley R, Westen D. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. (2004) 24:1011–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.004

Clin Psychol Rev. (2004) 24:1011–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.004

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Soomro GM, Altman D, Rajagopal S, Oakley-Browne M. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) vs. placebo for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Cochrane Database Systemat Rev. (2008) 2008:Cd001765. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001765.pub3

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. DeVeaugh-Geiss JKR, Landau P. Clomipramine in the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1991) 48:730–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320054008

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Jenike MA, Baer L, Summergrad P, Weilburg JB, Holland A, Seymour R. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of clomipramine in 27 patients. Am J Psychiatry. (1989) 146:1328–30. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.10.1328

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, Davies S, Campeas R, Franklin ME, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (2005) 162:151–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.151

Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, Davies S, Campeas R, Franklin ME, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (2005) 162:151–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.151

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Zohar J, Judge R. Paroxetine versus clomipramine in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. OCD Paroxetine Study Investigators. Br J Psychiatry J Mental Sci. (1996) 169:468–74. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.4.468

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Hirschtritt ME, Bloch MH, Mathews CA. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: advances in diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Assoc. (2017) 317:1358–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2200

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Bertolín S, Alonso P, Segalàs C, Real E, Alemany-Navarro M, Soria V, et al. First manic/hypomanic episode in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients treated with antidepressants: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 137:319–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.02.060

J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 137:319–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.02.060

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Pallanti S, Hollander E, Bienstock C, Koran L, Leckman J, Marazziti D, et al. Treatment non-response in OCD: methodological issues and operational definitions. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. (2002) 5:181–91. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702002900

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Bloch MH, McGuire J, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Leckman JF, Pittenger C. Meta-analysis of the dose-response relationship of SSRI in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. (2010) 15:850–5. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.50

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Hollander E, Allen A, Steiner M, Wheadon DE, Oakes R, Burnham DB. Acute and long-term treatment and prevention of relapse of obsessive-compulsive disorder with paroxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. (2003) 64:1113–21. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v64n0919

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Montgomery SA, Kasper S, Stein D, Hedegaard K, Lemming O. Citalopram 20 mg, 40 mg and 60 mg are all effective and well tolerated compared with placebo in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (2001) 16:75–86. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200103000-00002

Montgomery SA, Kasper S, Stein D, Hedegaard K, Lemming O. Citalopram 20 mg, 40 mg and 60 mg are all effective and well tolerated compared with placebo in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (2001) 16:75–86. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200103000-00002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Nakajima T, Kudo Y, Yamashita I. Clinical usefulness of Fluvoxamine Maleate (SME3110), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a double blind, placebo-controlled study investigating the therapeutic dose range and the efficacy of SME3110. J Clin Therapeut Med. (1996) 12:409–37.

21. Tollefson GD, Rampey AH Jr, Potvin JH, Jenike MA, Rush AJ, kominguez RA, et al. A multicenter investigation of fixed-dose fluoxetine in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archiv Gen Psychiatry. (1994) 51:559–67. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070051010

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Greist J, Chouinard G, DuBoff E, Halaris A, Kim SW, Koran L, et al. Double-blind parallel comparison of three dosages of sertraline and placebo in outpatients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1995) 52:289–95. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950160039008

Greist J, Chouinard G, DuBoff E, Halaris A, Kim SW, Koran L, et al. Double-blind parallel comparison of three dosages of sertraline and placebo in outpatients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1995) 52:289–95. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950160039008

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Montgomery SA, McIntyre A, Osterheider M, Sarteschi P, Zitterl W, Zohar J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluoxetine in patients with DSM-III-R obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Lilly European OCD Study Group. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol J Eur Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. (1993) 3:143–52. doi: 10.1016/0924-977X(93)90266-O

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. med PGJP. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons (2019). doi: 10.1002/9781119536604

Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons (2019). doi: 10.1002/9781119536604

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Atkinson LZ, Leucht S, Ruhe HG, Turner EH, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of first-generation and second-generation antidepressants in the acute treatment of major depression: protocol for a network meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e010919. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010919

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Furukawa TA, Cipriani A, Cowen PJ, Leucht S, Egger M, Salanti G. Optimal dose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, venlafaxine, and mirtazapine in major depression: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:601–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30217-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D. Addressing reporting biases. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (2008). p. 297–333. doi: 10.1002/9780470712184.ch20

Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D. Addressing reporting biases. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (2008). p. 297–333. doi: 10.1002/9780470712184.ch20

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

29. Patel MX, Arista IA, Taylor M, Barnes TR. How to compare doses of different antipsychotics: a systematic review of methods. Schizophr Res. (2013) 149:141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.06.030

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Davis JM. Dose equivalence of the antipsychotic drugs. In: Matthysse SW, Kety SS, editors. Catecholamines and Schizophrenia. Pergamon (1975). p. 65–73. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-018242-1.50015-5

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Hayasaka Y, Purgato M, Magni LR, Ogawa Y, Takeshima N, Cipriani A, et al. Dose equivalents of antidepressants: evidence-based recommendations from randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. (2015) 180:179–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.021

(2015) 180:179–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.021

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Bollini P, Pampallona S, Tibaldi G, Kupelnick B, Munizza C. Effectiveness of antidepressants. Meta-analysis of dose-effect relationships in randomised clinical trials. Br J Psychiatry J Mental Sci. (1999) 174:297–303. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.297

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Jakubovski E, Varigonda AL, Freemantle N, Taylor MJ, Bloch MH. Systematic review and meta-analysis: dose-response relationship of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (2016) 173:174–83. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030331

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

34. WHO. WHO Collaborative Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD System. (2020). Available online at: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ (accessed December 24, 2020).

35. Xu C, Doi SAR. The robust error meta-regression method for dose-response meta-analysis. Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2018) 16:138–44. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000132

The robust error meta-regression method for dose-response meta-analysis. Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2018) 16:138–44. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000132

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Xu C, Liu Y, Jia PL, Li L, Liu TZ, Cheng LL, et al. The methodological quality of dose-response meta-analyses needed substantial improvement: a cross-sectional survey and proposed recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. (2019) 107:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.11.007

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Feinberg M. Clomipramine for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am Fam Physician. (1991) 43:1735–8.

Google Scholar

What they treat us with: Prozac. From depression to bulimia

Medicine

16:00, December 14, 2017

Analysis of one of the popular antidepressants how it is customary to treat them and whether the antidepressant Prozac works, read in the new material of the heading “How we are treated”.

Prozac is on the list of the most important, safest and most effective (including from an economic point of view) drugs according to the World Health Organization. However, as we remember after the article with the analysis of Tamiflu, this does not guarantee its effectiveness. nine0003

Prozac is prescribed for the treatment of depression, obsessive-compulsive disorders, bulimia nervosa. If you know very well what it is, you can immediately skip to the “from what, from what” part.

When life is not nice

Depression is called depression, loss of interest in what used to make the patient happy. According to the international classification of diseases ICD-10, the main criteria by which such a diagnosis can be made include depressed mood for more than two weeks, loss of strength and consistently high fatigue (more than a month) and anhedonia (the inability to enjoy what used to bring joy). Doctors consider additional criteria for depression to be pessimism, low self-esteem, thoughts of death and suicide, appetite disturbances (weight loss or overeating), sleep problems, constant fears and anxieties, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, inability to concentrate, and a constant sweet taste in the mouth. These symptoms are unlikely to occur simultaneously (for example, fatigue and apathy may predominate in some cases, while anxiety and guilt may prevail in others), therefore, in order to diagnose depression, the patient's condition must meet at least two main criteria and three additional ones. At the same time, according to the definition of the US National Institute of Mental Health, such a state should last quite a long time (more than two weeks). nine0003

These symptoms are unlikely to occur simultaneously (for example, fatigue and apathy may predominate in some cases, while anxiety and guilt may prevail in others), therefore, in order to diagnose depression, the patient's condition must meet at least two main criteria and three additional ones. At the same time, according to the definition of the US National Institute of Mental Health, such a state should last quite a long time (more than two weeks). nine0003

Severe depression (clinical) includes a complex set of symptoms called major depressive disorder and may sometimes not be accompanied by low mood at all. However, because of her, the patient is physically unable to live and work normally, and the comments of those around him in the spirit of “he just can’t pull himself together” or “enough to turn sour that he spread snot” sound like a mockery. Such phrases stigmatize depression, blaming a person for his condition, while he himself will not be able to cope and needs treatment. To diagnose major depressive disorder, there is a whole questionnaire of major depression compiled by the World Health Organization. Also, depressive disorders include other conditions accompanied by depression, such as dysthymia (daily low mood and mild symptoms of depression for two years or more). nine0003

To diagnose major depressive disorder, there is a whole questionnaire of major depression compiled by the World Health Organization. Also, depressive disorders include other conditions accompanied by depression, such as dysthymia (daily low mood and mild symptoms of depression for two years or more). nine0003

The causes of depression can be very different: somatic (due to diseases of the body), psychological (after strong dramatic experiences, such as the death of a relative) and iatrogenic (as a side effect of certain drugs). As strange as it would be to provide first aid to a victim of an electric shock without removing the wire from him, it is difficult to cure the symptoms of depression without eliminating its cause or changing the lifestyle that led the patient to such a state. If the patient lacks some essential substances (for example, tryptophan), it is important to make up for their lack, and not just fight the depressed mood with drugs. If he has some kind of psychological trauma, the help of a psychotherapist will be required. And for a person whose depression is provoked by hormonal disorders, neurological diseases, heart disease, diabetes, or even cancer (and this happens), it is more important to cure the disease itself, and symptomatic treatment of depression will be a secondary goal. nine0003

And for a person whose depression is provoked by hormonal disorders, neurological diseases, heart disease, diabetes, or even cancer (and this happens), it is more important to cure the disease itself, and symptomatic treatment of depression will be a secondary goal. nine0003

When you can't stop

Obsessive-compulsive disorder, or OCD (also called obsessive-compulsive disorder), consists of two mandatory components: obsessions (obsessive anxious or frightening thoughts) and compulsions (compulsive actions). A classic example is cleanliness-related OCD, where a person is afraid of contamination or contamination by microorganisms. Such thoughts and fears are called obsessions. In order to protect themselves from them, a person will worry too much about cleanliness, such as constantly washing their hands. Any contact with a non-sterile, according to the patient, object, plunges such a person into horror. And if you can’t wash your hands again, he will experience real suffering. nine0003

nine0003

You can learn how to deal with medications on your own in the author's online course "How we are treated" by the editor of Indicator.Ru Ekaterina Mishchenko: https://clck.ru/Pnmtk

Such "protective" behavior is called compulsion. The desire for cleanliness can be understood if a person is in conditions of complete unsanitary conditions or, on the contrary, wants to maintain sterile conditions somewhere in the operating room. But if the action loses its true meaning and becomes a mandatory ritual, it becomes a compulsion. nine0003

However, OCD can manifest itself not only as a fear of pollution, but also as excessive superstition, fear of losing a necessary object, sexual or religious obsessive thoughts and related actions. Their reasons may lie in several areas: biological and psychological. The first includes diseases and features of the nervous system, lack of neurotransmitters (biologically active substances that ensure the transmission of a nerve impulse from one neuron to another, for example, dopamine or serotonin), genetic predisposition (mutations in the hSERT gene encoding the serotonin carrier protein and located on 17 -th chromosome). nine0003

nine0003

There is also an infectious theory of the development of OCD, associated with the fact that in children it sometimes occurs after infection with streptococcus. This theory is called PANDAS - an abbreviation for the English Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infections, which translates as "Children's autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections." The cause of this syndrome may be an attack of its own antibodies produced against streptococcus on the patient's nerve cells. However, this theory has not yet been confirmed. nine0003

Another group of explanations for the development of OCD is psychological. They go back to the theories of the beginning of the last century (from Freud to Pavlov). Mayakovsky's father died of blood poisoning after being injected with a binder, so it is believed that the poet also showed a pathological love for cleanliness. But you don't have to be a futurist poet to experience the full benefits of OCD: even dogs and cats suffer from it. Only in them this is expressed in the endless licking of wool and attempts to catch their tail. nine0003

Only in them this is expressed in the endless licking of wool and attempts to catch their tail. nine0003

The Yale-Brown scale is used to diagnose obsessive-compulsive disorder. In the fight against OCD, the method of psychological persuasion can be useful: patients are patiently explained that if they skip the “ritual” once, nothing terrible will happen. But drugs are also used in treatment.

When you are how you eat

Bulimia nervosa (third indication for Prozac) is a binge eating disorder. The main signs of bulimia are uncontrolled eating in large quantities, obsession with excess weight (calorie counting, attempts to induce vomiting after eating, fasting, use of laxatives), low self-esteem, low blood pressure. Other symptoms are sudden changes in body weight, kidney problems and dehydration, enlarged salivary glands, heartburn after eating, and inflammation of the esophagus. Due to provoking vomiting, hydrochloric acid from the stomach constantly enters the oral cavity of patients, which can lead to grinding of tooth enamel and ulcers on the mucous membrane. According to the DSM-5 classification of diseases, uncontrolled consumption of large amounts of food and the simultaneous use of various drastic measures for weight loss is the main criterion for diagnosing bulimia nervosa. nine0003

According to the DSM-5 classification of diseases, uncontrolled consumption of large amounts of food and the simultaneous use of various drastic measures for weight loss is the main criterion for diagnosing bulimia nervosa. nine0003

Video about bulimia on the educational medical resource Open Osmosis (USA)

The causes of bulimia can be either biological (incorrect levels of hormones or neurotransmitters, including serotonin) or social. The importance of the latter is highlighted, for example, in a high-profile study among teenage girls in Fiji, which showed a sharp increase in cases of intentional bowel cleansing for weight loss in just three years (from 1995 to 1998) after television appeared in the province. Perhaps the desire to be like models from the screens and covers really pushes for such behavior. nine0003

Bulimia can often be associated with other psychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders). According to a study by the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University, 70% of people with bulimia have ever experienced depression, compared with just over 25% in the general population.

According to a study by the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University, 70% of people with bulimia have ever experienced depression, compared with just over 25% in the general population.

Bulimia itself is not very common, and it can be more difficult to diagnose than the same anorexia, because changes in body weight in bulimia are less sharp and noticeable. For diagnosis, the food attitude test, developed by the Clark Institute of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto, and other tests based on it, are used. But (as with the tests for OCD and depression above), its result only indicates the likelihood that the patient has developed a disorder, but does not allow for a definitive diagnosis, especially for oneself. nine0003

From what, from what

What is a medicine that is prescribed for three types of disorders at once? The active ingredient in Prozac is fluoxetine. The patent for Prozac expired back in 2001, so many generics are available in pharmacies - cheaper copies that use the same active ingredient, but are not as well studied and may differ slightly from the original. These drugs include Fluoxetine, Prodel, Profluzak, Fluval.

These drugs include Fluoxetine, Prodel, Profluzak, Fluval.

Fluoxetine, discovered and marketed by Eli Lilly and Company, belongs to a group of antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. This group is considered third-generation antidepressants, fairly well tolerated and without significant side effects. nine0003

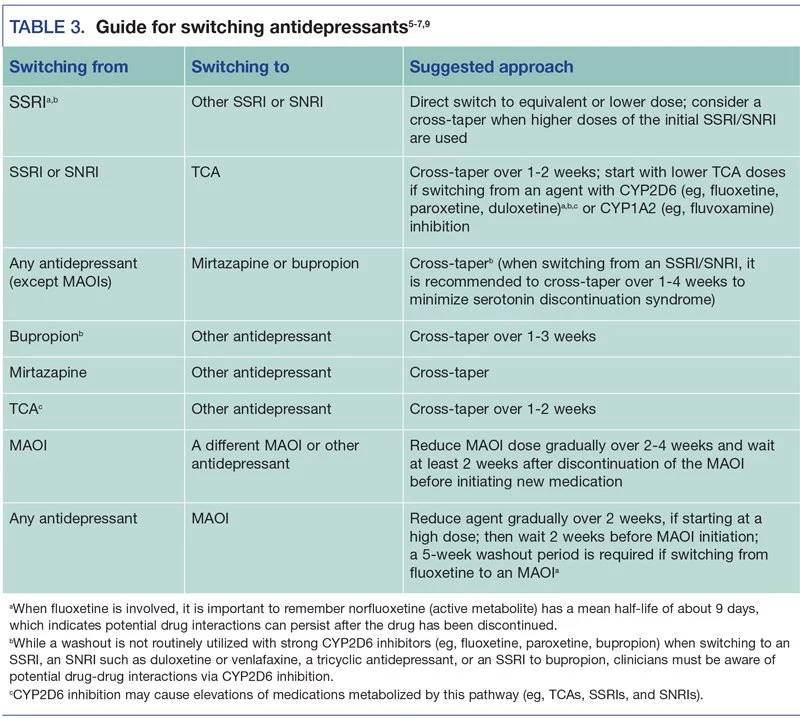

Fluoxetine is readily absorbed into the blood, can bind to plasma proteins and accumulate in body tissues. It also penetrates the blood-brain barrier, which protects the nervous system and brain from many substances circulating in the blood. There, in the nervous system, it works in the synaptic cleft we have already mentioned, preventing the excess serotonin ejected from the synapse from returning to the neurotransmitter. Because of this, serotonin is longer present in the synaptic cleft and can bind to receptors. How exactly fluoxetine achieves this effect is not clear even to manufacturers, but it is known that it has little effect on the work of other neurotransmitters. However, at high doses, fluoxetine increases adrenaline and dopamine levels, as studies in rat brain tissue show. nine0003

However, at high doses, fluoxetine increases adrenaline and dopamine levels, as studies in rat brain tissue show. nine0003

Fluoxetine and its metabolite, norfluoxetine, can interfere with each other's actions. Because of this, according to scientists from the Institute of Research Medicine in Barcelona, a constant concentration of fluoxetine in the blood is achieved only after four weeks of taking the drug. Similarly, the effects of taking the medicine do not disappear immediately. Associated with this is the difficulty in selecting the required dose for a particular patient.

Serotonin itself, which is absolutely incorrectly called the “happiness hormone” (hormones are produced in one organ of the body, but perform their function in another, serotonin in this context simply conducts nerve impulses in the brain regions responsible for good mood, and is produced there well), in fact, it performs much more functions. Yes, it affects mood, sleep, and appetite, so some cases of depression, bulimia nervosa, and OCD may be caused by insufficient production of this neurotransmitter and corrected with serotonin reuptake inhibitors. But in addition, platelets can actively capture it and affect blood clotting. Serotonin is also involved in the processes of memorization and learning. At the same time, not only vertebrate animals can produce it: according to a study by Chinese and American scientists, the pain from an insect bite is largely due to the presence of serotonin in the poison, and the dysentery amoeba, according to an article in Science, can cause diarrhea by releasing serotonin in our intestines. nine0003

But in addition, platelets can actively capture it and affect blood clotting. Serotonin is also involved in the processes of memorization and learning. At the same time, not only vertebrate animals can produce it: according to a study by Chinese and American scientists, the pain from an insect bite is largely due to the presence of serotonin in the poison, and the dysentery amoeba, according to an article in Science, can cause diarrhea by releasing serotonin in our intestines. nine0003

The lists (not) included

But all these are just mechanisms, and besides, they have not been studied to the smallest detail. To understand how this works in real people and how often it helps, let's turn to clinical trials. However, anyone who enters the combination “fluoxetine depression double blind randomized controlled” into the PubMed scientific article database and filters clinical trial (clinical trial) will see more than 558 articles, up to work comparing the effectiveness of Prozac and homeopathy. nine0003

nine0003

Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled method is a method of clinical drug research in which the subjects are not privy to important details of the study being conducted. “Double-blind” means that neither the subjects nor the experimenters know who is being treated with what, “randomized” means that the distribution into groups is random, and placebo is used to show that the effect of the drug is not based on autosuggestion and that this medicine helps better than a tablet without active substance. This method prevents subjective distortion of the results. Sometimes the control group is given another drug with already proven efficacy, rather than a placebo, to show that the drug not only treats better than nothing, but also outperforms analogues. nine0003

Indicator.Ru

Help

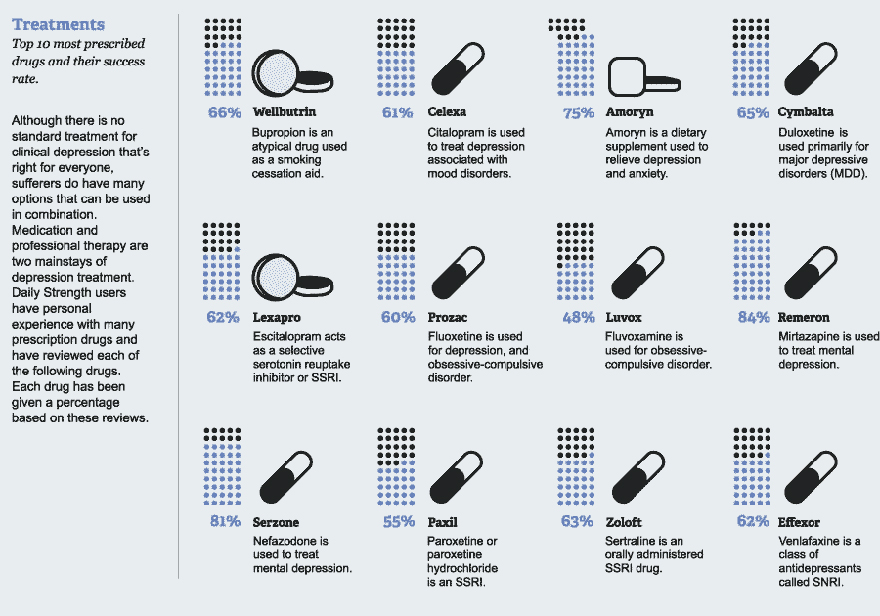

No living person can analyze them within an adequate period of time. And even Cochrane reviews can be found as many as 36 (that's really a lot), although not all of them consider the action of fluoxetine for its direct indications (depression, bulimia and obsessive-compulsive disorder).

The Cochrane Library is a database of the Cochrane Collaboration, an international non-profit organization involved in the development of World Health Organization guidelines. The name of the organization comes from the name of its founder, the 20th-century Scottish medical scientist Archibald Cochrane, who championed the need for evidence-based medicine and the conduct of competent clinical trials and wrote the book Efficiency and Efficiency: Random Reflections on Public Health. Medical scientists and pharmacists consider the Cochrane Database one of the most authoritative sources of such information: the publications included in it have been selected according to the standards of evidence-based medicine and report the results of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. nine0003

Indicator.Ru

Help

One of them is dedicated to antidepressants used against bulimia nervosa. Although in general the authors note that there is little data on this topic, fluoxetine (for which there were only five randomized double-blind controlled trials in 2003) is recognized as a leader in this direction. However, the authors refuse to recommend this medicine in the conclusion, arguing that not all clinical trial data have been published and are available for consideration. nine0003

However, the authors refuse to recommend this medicine in the conclusion, arguing that not all clinical trial data have been published and are available for consideration. nine0003

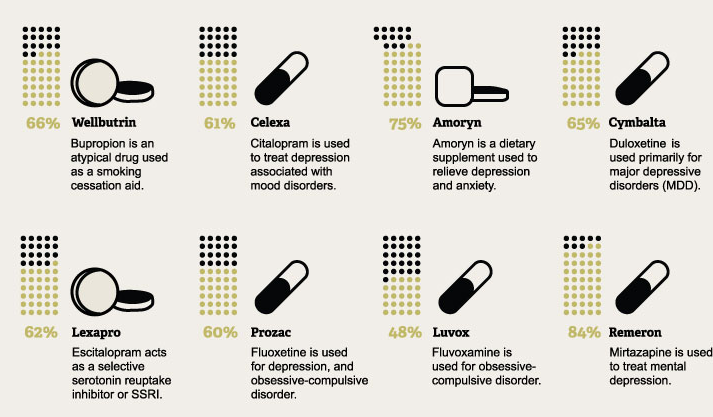

The authors of a 2008 review reviewed the benefits of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (including fluoxetine) in obsessive-compulsive disorder and concluded that they help better than placebo, and the associated side effects are much more significant, among which nausea is most common , insomnia and headache. According to a 2013 review, the usefulness of this same group of drugs in autism and related OCD is unclear, and the data are insufficient to conclude.

The most popular subject of fluoxetine reviews was the fight against depression. But the authors of most of them note the lack of data (for example, in this 2013 review). In a broad inclusion criteria review of 1177 randomized controlled trials of fluoxetine for depression in adults, the authors conclude that it is about as effective as other antidepressants but less toxic. However, they warn against hasty decisions, since most of the studies were conducted on small groups of people (100 or less) and were funded by the manufacturer, which is more profitable to publish only positive results, hiding information about failures. Data on postpartum depression are also found to be insufficient and inconsistent. The same issues are highlighted by a review of articles on the effectiveness of antidepressants against dementia-related senile depression. nine0003

However, they warn against hasty decisions, since most of the studies were conducted on small groups of people (100 or less) and were funded by the manufacturer, which is more profitable to publish only positive results, hiding information about failures. Data on postpartum depression are also found to be insufficient and inconsistent. The same issues are highlighted by a review of articles on the effectiveness of antidepressants against dementia-related senile depression. nine0003

Indicator.Ru concludes: one of the best stimulant antidepressants is still not perfect

A large number of studies confirm the effectiveness of fluoxetine, a key component of Prozac. But part of the reviews of the Cochrane Collaboration note that not all trial data have been published by manufacturers. And this accusation is not an empty phrase: according to Eli Lilly's internal documents, manufacturers during trials often attributed suicide cases to worsening depression or overdosing on the drug. nine0003

nine0003

As a result, following numerous reports of suicide by patients prescribed this drug, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a warning label to the drug's packaging.