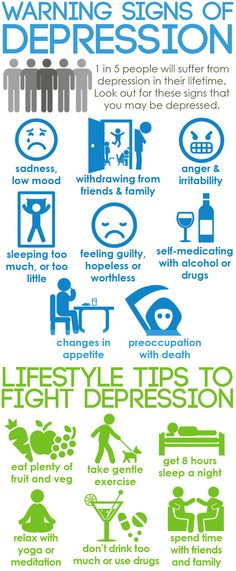

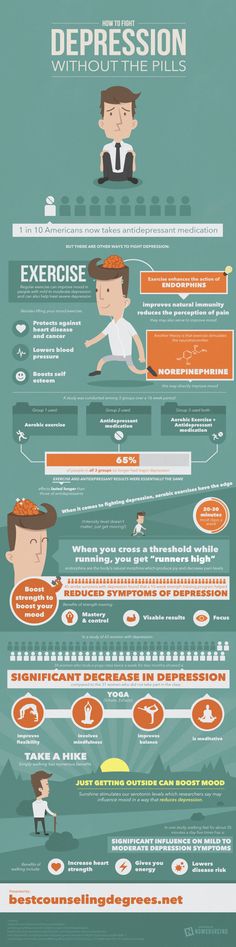

Fighting depression with exercise

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

HomeWelcome to the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator, a confidential and anonymous source of information for persons seeking treatment facilities in the United States or U.S. Territories for substance use/addiction and/or mental health problems.

PLEASE NOTE: Your personal information and the search criteria you enter into the Locator is secure and anonymous. SAMHSA does not collect or maintain any information you provide.

Please enter a valid location.

please type your address

-

FindTreatment.

gov

gov Millions of Americans have a substance use disorder. Find a treatment facility near you.

-

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

Call or text 988

Free and confidential support for people in distress, 24/7.

-

National Helpline

1-800-662-HELP (4357)

Treatment referral and information, 24/7.

-

Disaster Distress Helpline

1-800-985-5990

Immediate crisis counseling related to disasters, 24/7.

- Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Finding Treatment

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Facility Directors

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Other Locator Functionalities

- Download Search ResultsDownload Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Print Search ResultsPrint Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). - Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). Find programs providing methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

The Locator is authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act (Public Law 114-255, Section 9006; 42 U.S.C. 290bb-36d). SAMHSA endeavors to keep the Locator current. All information in the Locator is updated annually from facility responses to SAMHSA’s National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N-SUMHSS). New facilities that have completed an abbreviated survey and met all the qualifications are added monthly. Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Exercise for depression | Cochrane

Why is this review important?

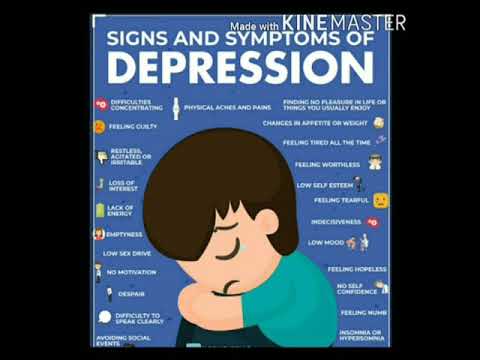

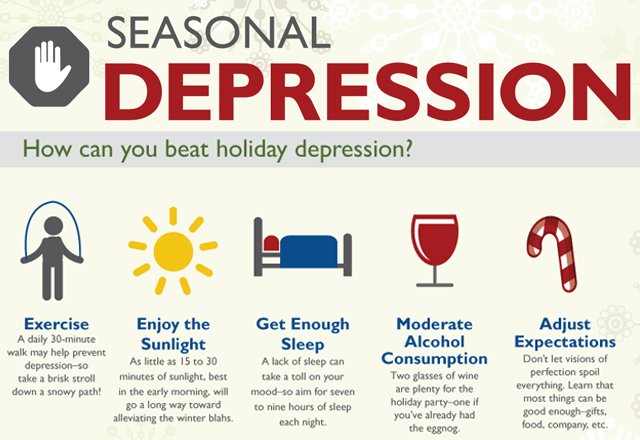

Depression is a common and disabling (disabling) disease that affects more than 100 million people worldwide. Depression can have a significant impact on people's physical health, as well as reduce their quality of life. Studies have shown that both methods - pharmacological and psychological treatments may be effective in treating depression. However, many people choose to try alternative treatments. Some NHS guidelines suggest using exercise as a method of choosing another treatment. However, it is not clear whether Studies have found that exercise is an effective treatment for depression.

However, it is not clear whether Studies have found that exercise is an effective treatment for depression.

Who might be interested in this review?

Patients and their families suffering from depression.

General practitioners.

Mental health policy makers.

Psychiatric professionals.

What questions does this review seek to answer?

This review is an update of a previous Cochrane review from 2010 which suggested that exercise may reduce depressive symptoms, but the effect was small and did not appear to last after participants stopped exercising.

We wanted to find out if there have been more clinical trials on the effect of exercise as a treatment for depression since our last review that would allow us to answer the following questions:

Is exercise really more effective than no therapy in reducing symptoms of depression ?

Is exercise more effective than antidepressants in reducing symptoms of depression?

Is exercise more effective than psychological therapy or other non-medical treatments for depression?

How acceptable is exercise to patients as a treatment for depression?

What studies were included in the review?

We searched databases to find all high quality randomized controlled trials that assessed the effectiveness of exercise in treating depression in adults over 18 years of age. We searched for studies published up to March 2013. We also searched for current studies up to March 2013. All studies had to include adults diagnosed with depression, and physical activity undertaken had to meet criteria to ensure that it [physical activity] fit the definition of "exercise."

We searched for studies published up to March 2013. We also searched for current studies up to March 2013. All studies had to include adults diagnosed with depression, and physical activity undertaken had to meet criteria to ensure that it [physical activity] fit the definition of "exercise."

We included 39 studies with a total of 2326 participants in the review. The review authors noted that the quality of some of the studies was low, limiting confidence in the conclusions. When only high-quality trials were included, exercise only had a small effect on mood that was not statistically significant.

What does the evidence from this survey tell us?

Exercise is somewhat more effective in reducing symptoms of depression than no treatment.

Exercise is no more effective than antidepressants in reducing symptoms of depression, although this conclusion is based on a small number of studies.

Exercise is no more effective than psychological therapy for reducing symptoms of depression, although this conclusion is based on a small number of studies.

The review authors also noted that when only high-quality studies were included, the difference between exercise and no treatment was less conclusive.

Attendance for exercise [training] ranged from 50% to 100%.

Evidence on whether exercise improves quality of life in depression is inconclusive.

What should happen next?

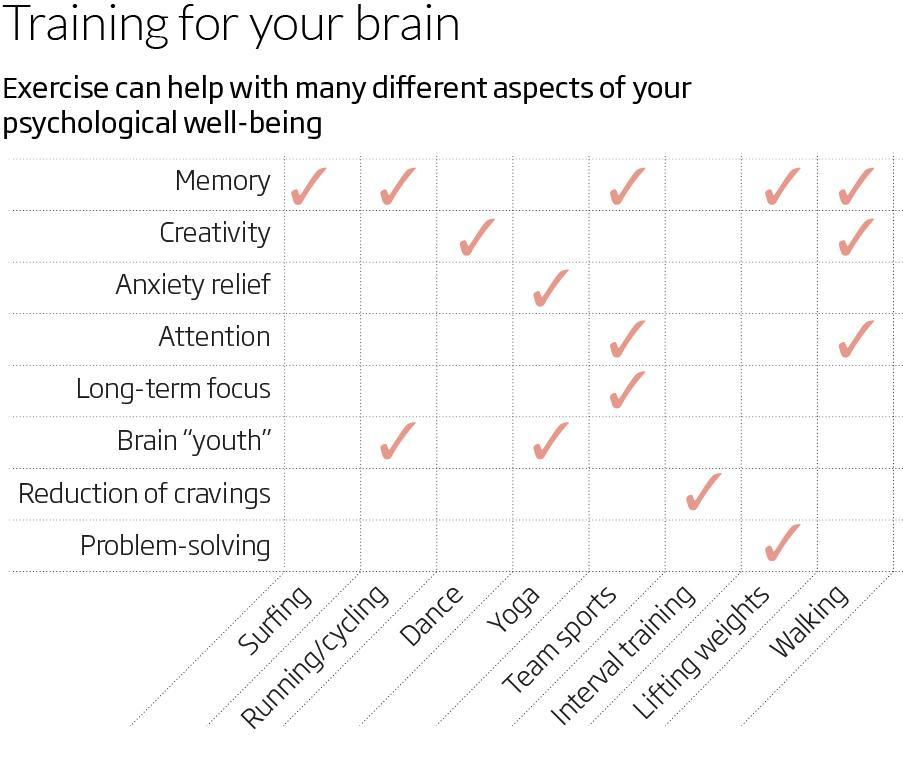

The review authors recommend that future research consider in more detail what types of exercise might be most beneficial for people with depression, and the number and duration of those activities that are most beneficial. Further large clinical trials are needed to see if exercise is as effective as antidepressants or psychological treatments.

Translation notes:

Translation: Ziganshina Lilia Evgenievna. Editing: Abakumova Tatyana Rudolfovna. Russian translation project coordination: Kazan Federal University. For questions related to this transfer, please contact us at: [email protected]

Physical exercise in the treatment of depression.

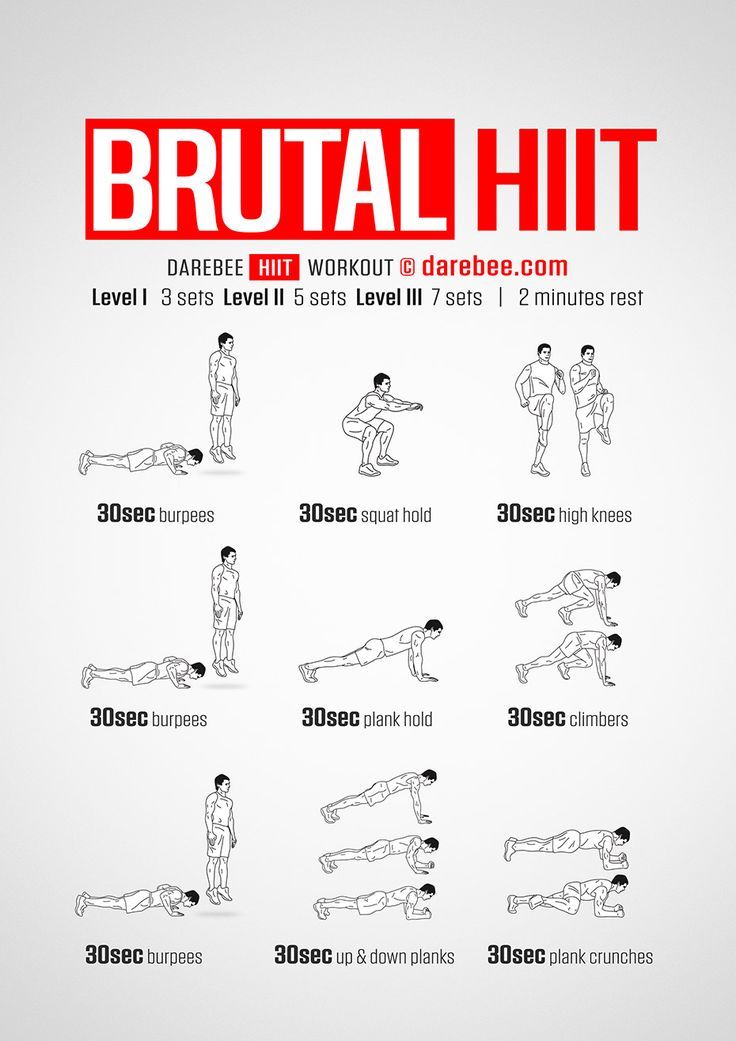

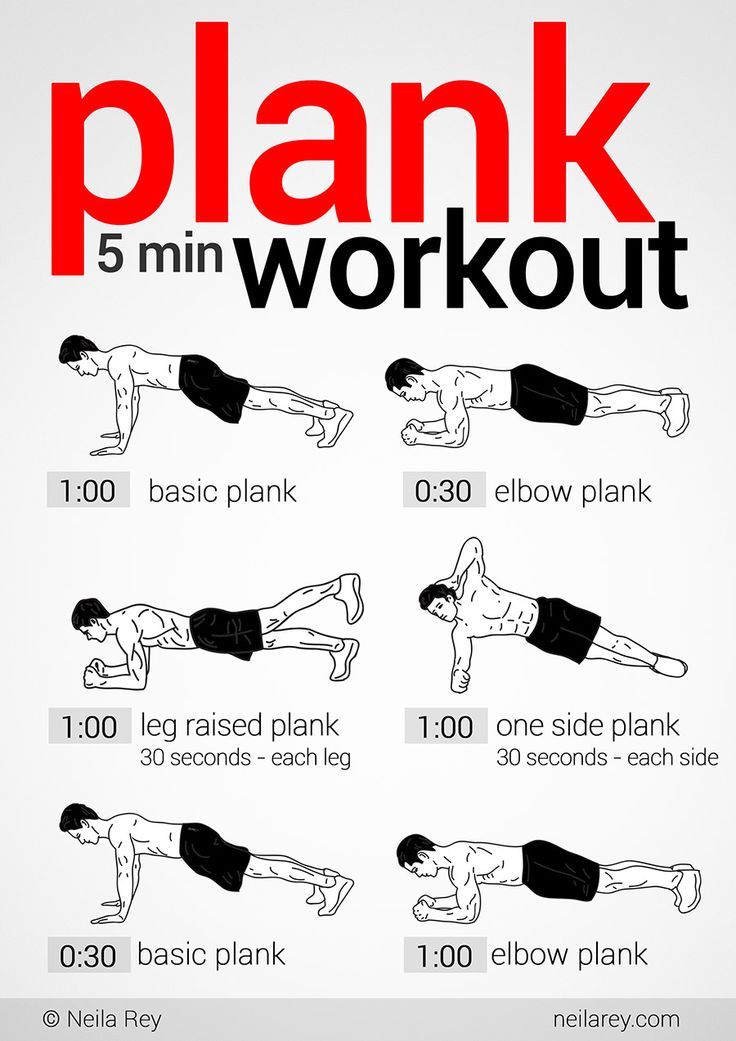

Modes and types of load

Modes and types of load

Introduction

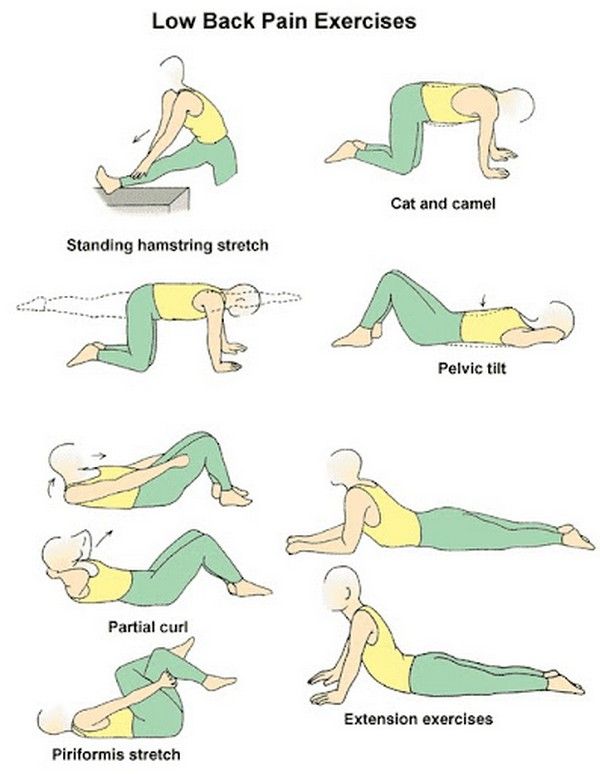

Depression is a major problem for the individual, family and society and is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide. Currently, according to WHO estimates, it affects more than 300 million people of different age groups [1]. Its clinical manifestations include a complex of emotional, cognitive and somatic symptoms that cause a significant deterioration in social and professional functioning. In almost half of patients, depression occurs with relapses [2], and in every fifth patient it becomes chronic [3], requiring an increase in healthcare resources [4]. The situation is aggravated by the fact that depression increases the risk of metabolic disorders, including type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases [5–8], and there is a decrease in life expectancy by 8–10 years [9].

Pharmacotherapy is the first line treatment for depression [10, 11]. However, the side effects associated with the use of pharmaceuticals, as well as the resistance to drug therapy that occurs in some cases, create difficulties in treatment [12–16]. In this regard, the search for new non-pharmacological approaches to the treatment of depression is relevant.

In this regard, the search for new non-pharmacological approaches to the treatment of depression is relevant.

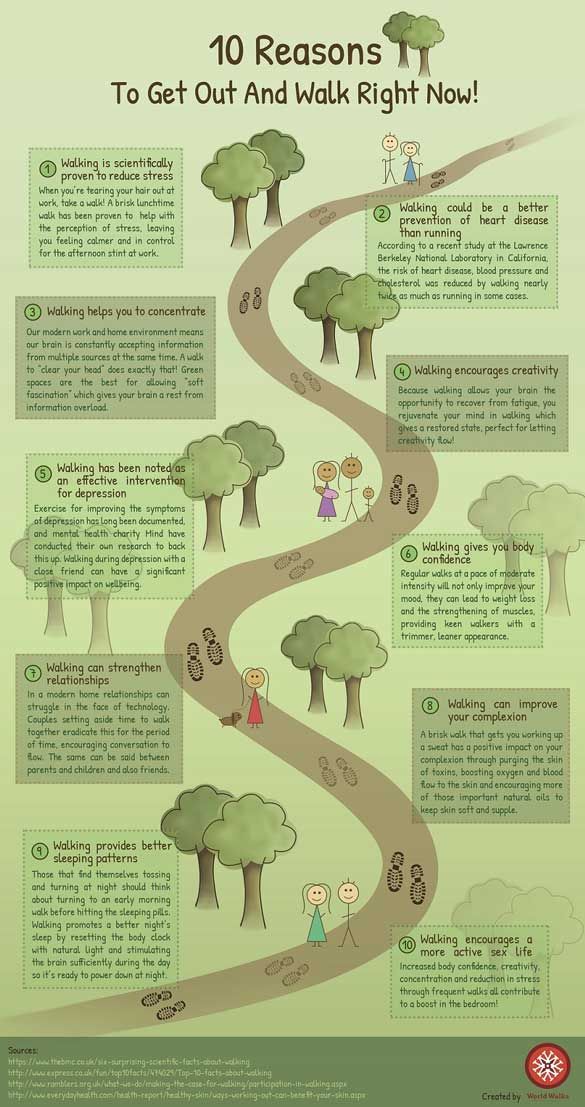

Recently, the use of physical activity (PE) has been increasingly used for the treatment and rehabilitation of patients with depression and many other diseases [17]. Physical activity not only relieves symptoms of depression [18] by increasing aerobic processes in the body and muscle strength [19, 20], but also has a positive effect on comorbid diseases with depression [21]. Cohort studies [22–26] revealed an inverse relationship between regular physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness (fitness), on the one hand, and the severity of depressive symptoms, on the other.

There are a number of meta-analyses of relevant studies in the literature on this subject. Thus, according to a meta-analysis [27] of prospective cohort studies, it was found that physical activity can provide protection against the onset of depression, regardless of age and geographical region of residence. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of the last 10 years, in which several dozen clinical trials with FN were analyzed, showed that FN has an antidepressant effect of moderate severity, comparable to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy [28–32]. The authors of one of them [33] concluded that the positive effect of FN was underestimated and considered that the magnitude of the FN effect can be classified as large. At the same time, it was emphasized that FN is financially inexpensive, has no negative side effects and improves overall health.

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of the last 10 years, in which several dozen clinical trials with FN were analyzed, showed that FN has an antidepressant effect of moderate severity, comparable to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy [28–32]. The authors of one of them [33] concluded that the positive effect of FN was underestimated and considered that the magnitude of the FN effect can be classified as large. At the same time, it was emphasized that FN is financially inexpensive, has no negative side effects and improves overall health.

FN makes it possible to reduce the dose of pharmacological preparations when it is used simultaneously with antidepressant therapy [19]. It was also found [34] that an 8-week exercise therapy in addition to pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavioral group therapy (CGT) for major depressive disorder (MDD) provided a better clinical effect than these interventions without FN. In addition, FN improved the quality of sleep and cognitive function of the patient, while there was an increase in the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [34].

Since there are no recommendations yet for the use of exercise therapy for the treatment of depression, psychiatrists most often use recommendations for the prevention of cardiovascular disease [35], although their adequacy for such cases has not been studied.

In the practical application of physical activity for depression, the following questions naturally arise: do different types and modes of physical activity differ in their antidepressant effect? If so, what is the most efficient load? And on what parameters of FN does efficiency depend?

Studies that have attempted to answer these questions have been conflicting. This is due, in particular, to the fact that the existing studies were heterogeneous in terms of the conditions for conducting, the type and mode of physical activity, the composition and size of the control and experimental groups, and the duration of observation. In addition, physical activity is understood as a purposeful structured training, as well as non-specialized physical activity used in daily activities. Physical targeted training is aimed at developing certain qualities of the body (aerobic or strength endurance, muscle mass in bodybuilders, etc.) or at developing certain skills (shooting accuracy, getting into the ring, accuracy of movements during the fight). These differences in approach can, of course, affect the evaluation of the results of various studies. But there is something in common that unites different approaches to the use of FN - this is its physiological effect, which is associated with an increase in the energy expenditure of the body and stimulation of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, activation of skeletal muscles and the release of many biologically active substances - myokines involved in regulation of all body systems [36, 37].

Physical targeted training is aimed at developing certain qualities of the body (aerobic or strength endurance, muscle mass in bodybuilders, etc.) or at developing certain skills (shooting accuracy, getting into the ring, accuracy of movements during the fight). These differences in approach can, of course, affect the evaluation of the results of various studies. But there is something in common that unites different approaches to the use of FN - this is its physiological effect, which is associated with an increase in the energy expenditure of the body and stimulation of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, activation of skeletal muscles and the release of many biologically active substances - myokines involved in regulation of all body systems [36, 37].

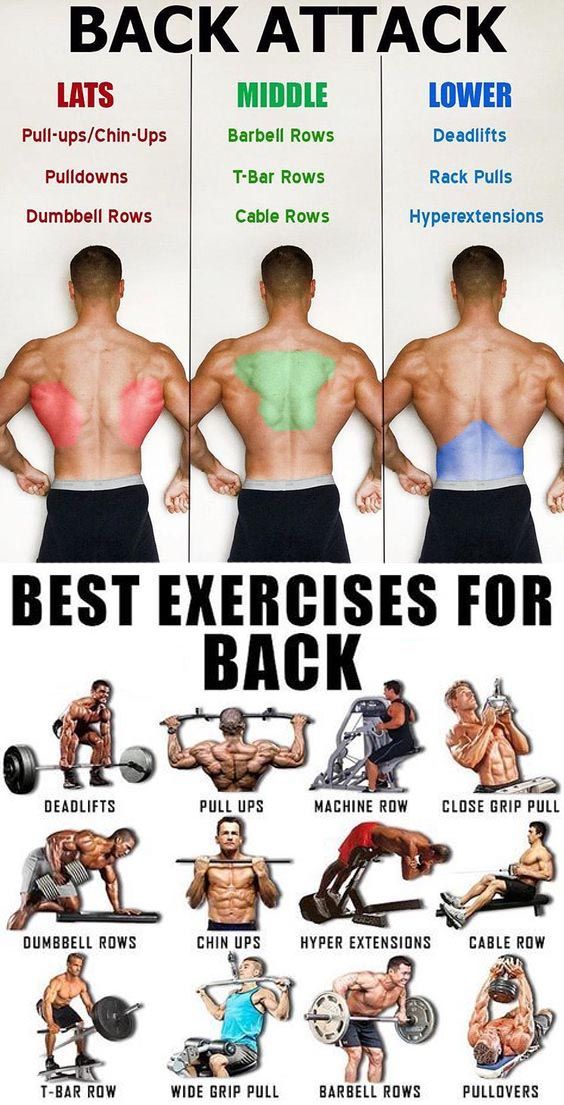

There are many types of purposeful physical training (aerobic-anaerobic endurance training, resistance training, mixed physical training). Separately, there are those requiring deep concentration on one's feelings or, in the case of paired techniques, on a partner, oriental practices and martial arts: yoga, tai chi tsuan, various dances, etc.

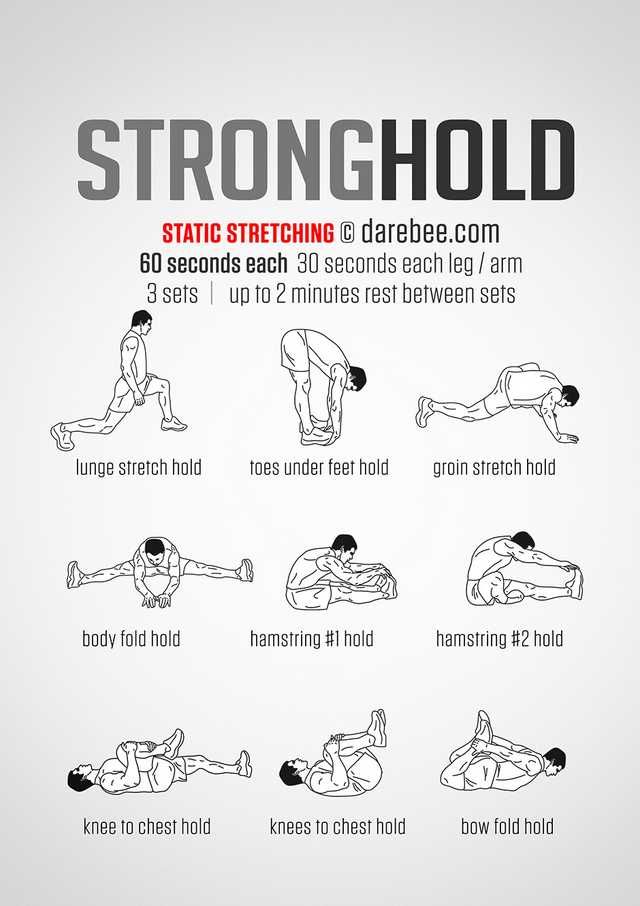

Aerobic or cardiorespiratory FN is the most commonly used in studies focusing on depression. It is easy to normalize and calibrate in intensity. Aerobic exercises, unlike strength (resistive) ones, do not require special skills and gyms equipped with simulators. It has been shown that cardiorespiratory training has a more beneficial effect on the cardiovascular system than resistance training [38]. Aerobic activities include running, cycling, and brisk walking. Physical activity is classified according to such criteria as intensity, frequency, duration, training regimens [39]. The impact of these types of stress on the body manifests itself in different ways. With aerobic exercise, the load on the oxygen-transport function increases (oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide release and heart rate - HR increase significantly), but the level of blood pressure (BP) changes insignificantly due to vasodilation. Under static resistive loading, on the contrary, the level of blood pressure rises sharply with a slight increase in heart rate [40], and the change in gas exchange is due to the size of the involved skeletal muscles. Therefore, the intensity of the first type is determined depending on the percentage of maximum oxygen consumption (MOC) or maximum heart rate, and the second - the percentage of maximum effort [39]. In addition, both types of physical activity can be assessed by subjectively perceived effort (modified Borg scale) [41–44].

Therefore, the intensity of the first type is determined depending on the percentage of maximum oxygen consumption (MOC) or maximum heart rate, and the second - the percentage of maximum effort [39]. In addition, both types of physical activity can be assessed by subjectively perceived effort (modified Borg scale) [41–44].

Influence of intensity and frequency of physical activity

It has been shown that with the direct (“acute”) effect of aerobic exercise on depressive mood in patients, the effect does not depend on the intensity of exercise (no dose-dependent effect was found) [45]. In a study by J Meyer et al. [45], 24 women aged 20–60 years with major depressive disorder (MDD) performed loads of varying intensity with an interval of 1 week in a random order. The intensity of the load was based on the subjectively felt effort on the Borg scale of 11, 13 and 15 points, respectively. The placebo was being on a bicycle ergometer without exercise. Changes in gas exchange, ventilation and heart rate confirmed subjective differences in the intensity of FN. Interestingly, even after 30 minutes of rest on a bicycle ergometer (placebo), the symptoms of depression on the POMS scale (Profile of Mood States - mood profile) were reduced. Real F.N. of varying intensity reduced depressive mood significantly more than placebo, but regardless of the intensity of physical activity.

Changes in gas exchange, ventilation and heart rate confirmed subjective differences in the intensity of FN. Interestingly, even after 30 minutes of rest on a bicycle ergometer (placebo), the symptoms of depression on the POMS scale (Profile of Mood States - mood profile) were reduced. Real F.N. of varying intensity reduced depressive mood significantly more than placebo, but regardless of the intensity of physical activity.

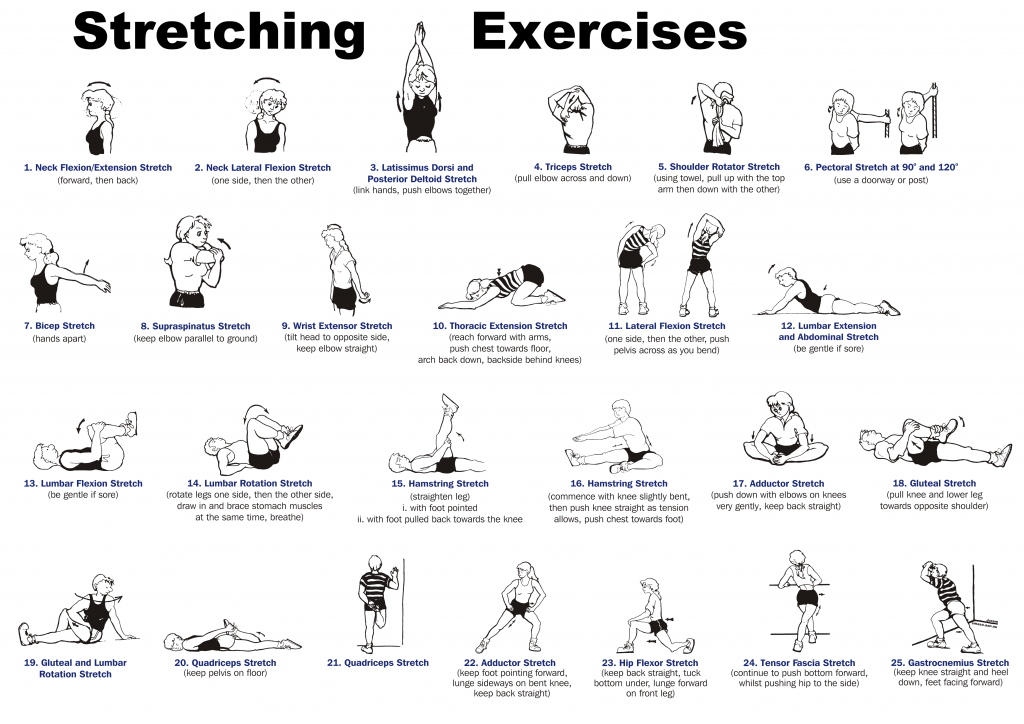

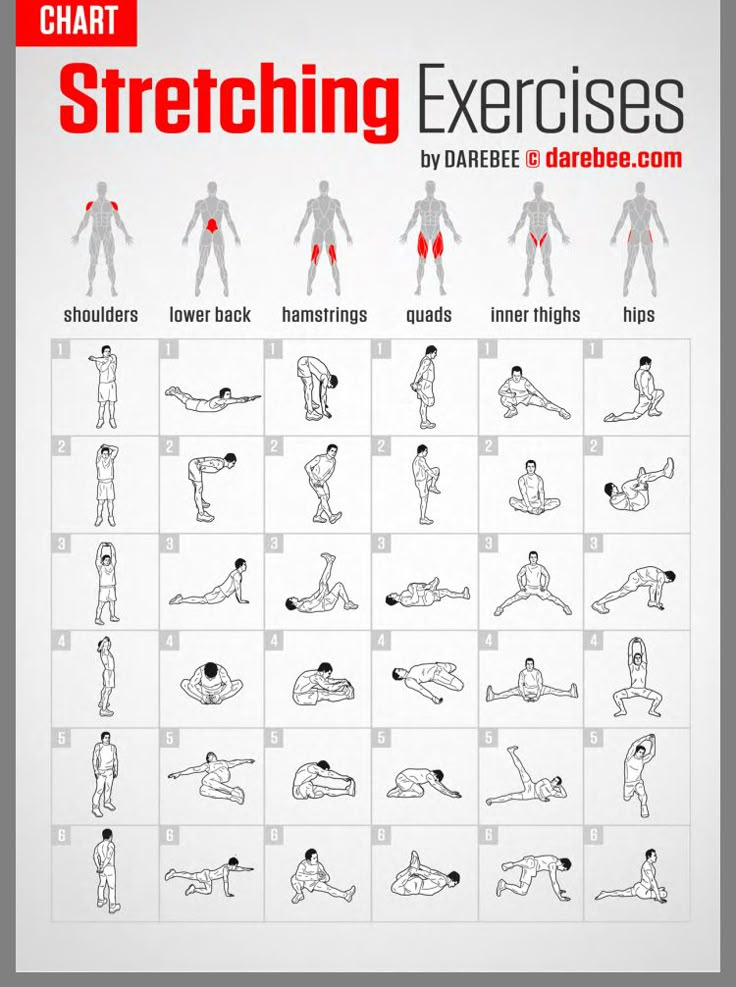

With prolonged exposure to physical activity, the results of studies regarding the dose-dependent effect of exercise and its intensity were contradictory. In particular, in patients with mild to moderate depression, the effect of a dose expressed in terms of energy expenditure per week was significant [46]. After 12 weeks of exposure to aerobic exercise in a group of 80 patients with MDD 20-45 years old, exercising with energy expenditure of 17.5 kcal/kg per 1 week (the so-called health dose), the reduction in depression symptoms, assessed by the Hamilton scale, was significantly greater than than in the group with lower energy expenditure (7 kcal/kg in 1 week) or in the control group, whose participants were engaged in stretching for 15-20 minutes 3 times a week. The average Hamilton score decreased after 12 weeks by 47, 30 and 29% respectively. At the same time, the decrease in symptoms of depression did not depend on the frequency of the sessions (3 or 5 times a week).

The average Hamilton score decreased after 12 weeks by 47, 30 and 29% respectively. At the same time, the decrease in symptoms of depression did not depend on the frequency of the sessions (3 or 5 times a week).

The effect of intensity during prolonged exposure to FN was also studied in patients with MDD by R. Balchin et al. [47]. In this study, 30 patients with moderate MDD (age 18-42 years) were divided into 3 groups: control (very low intensity exercise - walking or light cycling), moderate exercise (40-45% of the heart rate reserve) and high intensity (70-75% of the heart rate reserve). After 6 weeks of exercise 3 times a week for 1 hour, the moderate and high intensity groups showed an improvement in the severity of symptoms of depression on the Hamilton scale, but the low intensity group did not.

However, in another 12-week randomized controlled trial [48] comparing the efficacy of conventional therapy (pharmacotherapy + psychotherapy) for mild to moderate MDD with exercise therapy at three levels of intensity (intense, moderate and mild), an effect of intensity was not proven. Although this study included a large number of patients: 310 people in the control group and 310 people in all three groups with F.N. At the same time, moderate and intense exercise consisted of moderate and intensive aerobics, respectively, and light exercise consisted of yoga-based stretching. Patients were engaged in physical activity for 12 weeks, 3 times a week for 55 minutes. The reduction in symptoms with FN at all three levels of intensity was significantly more pronounced than with conventional therapy, but there was no significant difference between groups with FN of varying intensity in the magnitude of the decrease in the severity of depression according to the Montgomery-Asberg scale (MADRS). A year later, the long-term effects of physical activity of varying intensity on depression were assessed [49]. In those who practiced yoga stretching exercises and intense aerobic exercise, the symptoms of depression on the MADRS scale became significantly less pronounced compared to the moderate aerobic exercise group.

Although this study included a large number of patients: 310 people in the control group and 310 people in all three groups with F.N. At the same time, moderate and intense exercise consisted of moderate and intensive aerobics, respectively, and light exercise consisted of yoga-based stretching. Patients were engaged in physical activity for 12 weeks, 3 times a week for 55 minutes. The reduction in symptoms with FN at all three levels of intensity was significantly more pronounced than with conventional therapy, but there was no significant difference between groups with FN of varying intensity in the magnitude of the decrease in the severity of depression according to the Montgomery-Asberg scale (MADRS). A year later, the long-term effects of physical activity of varying intensity on depression were assessed [49]. In those who practiced yoga stretching exercises and intense aerobic exercise, the symptoms of depression on the MADRS scale became significantly less pronounced compared to the moderate aerobic exercise group.

It should be noted that in the above studies, different types of FN were performed. Yoga-based stretching is likely a separate class of exercise and is poorly comparable to aerobic exercise of varying intensity due to the additional effects of exercise on coordination.

In a study by H. Hanssen et al. [50] compared 2 regimens of aerobic training in patients with unipolar depression (34 patients, mean age 37.8 years, mean Beck II score (BDI-II) of 31): high-intensity interval training and long-term continuous moderate intensity. Patients practiced for 4 weeks, 3 times a week. Both exercise regimens were highly effective in reducing depressive symptoms. At the same time, the high-intensity regimen was more effective in reducing the severity of depression, and the long-term moderate intensity regimen was more effective in reducing peripheral arterial stiffness.

Comparison of the effect of PE, Internet Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (ICBT) and conventional therapy was carried out by M. Hallgren et al. [51]. They randomized 946 depressed patients to one of three 12-week exposure groups. At the same time, the majority of patients from the FN group attended only one lesson per week out of three recommended. FN and CPTI showed the same efficacy, which exceeded conventional therapy. Moreover, the antidepressant effect of FN persisted for 12 months from the start of exposure, despite only 30% adherence to the FN regimen [52].

Hallgren et al. [51]. They randomized 946 depressed patients to one of three 12-week exposure groups. At the same time, the majority of patients from the FN group attended only one lesson per week out of three recommended. FN and CPTI showed the same efficacy, which exceeded conventional therapy. Moreover, the antidepressant effect of FN persisted for 12 months from the start of exposure, despite only 30% adherence to the FN regimen [52].

In accordance with the results of a meta-analysis by F. Schuch et al. [33], high- and medium-intensity exercise shows a greater effect in the treatment of MDD than low-intensity exercise. However, the authors conclude that further studies of this issue are necessary due to the small number of observations.

In 2017, a randomized controlled trial was launched to investigate the effect of enhancing cognitive behavioral therapy with endurance training of varying intensity in depression [53]. It was supposed to compare the effect of high- and low-intensity 12-week physical activity on the condition of individuals diagnosed with a depressive episode of mild or moderate severity. For the high-intensity group, physical activity was prescribed at the level of 55-85% of the individual maximum heart rate reserve: 20 minutes - bicycle ergometer, 20 minutes - running or Nordic walking, 20 minutes - aerobic training for the body. For the low-intensity group, exercise was 20–30% of the maximum heart rate reserve: 20 min – bicycle ergometer, 20 min – walking, 20 min – stretching or relaxation. However, the results of this work have not yet been published.

For the high-intensity group, physical activity was prescribed at the level of 55-85% of the individual maximum heart rate reserve: 20 minutes - bicycle ergometer, 20 minutes - running or Nordic walking, 20 minutes - aerobic training for the body. For the low-intensity group, exercise was 20–30% of the maximum heart rate reserve: 20 min – bicycle ergometer, 20 min – walking, 20 min – stretching or relaxation. However, the results of this work have not yet been published.

An attempt to analyze the effect of variable parameters of FN on the antidepressant effect was made in several reviews of the last decade. In a review by L. Perraton et al. [54] concluded that an effective antidepressant program of cardiorespiratory (aerobic) physical activity should last at least 8 weeks, classes at least 3 times a week lasting from 30 minutes. At the same time, both individual and group training are effective [54]. The authors of a later review [55] conclude that further research is needed with the manipulation of FN variables (intensity, modes, etc. ). The analysis of randomized controlled trials only allowed us to conclude that both group and individual controlled aerobic exercise 3 times a week of moderate intensity for at least 9weeks are effective in the treatment of depression.

Influence of type FN

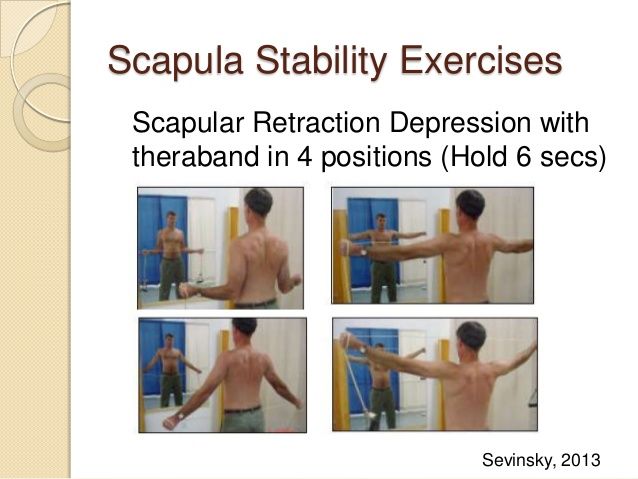

An analysis of the influence of the type of physical activity on symptoms of depression was reflected in two Cochrane reviews [56, 57]. They show that resistive or mixed aerobic-resistive exercise has a greater positive effect in the treatment of depression than purely aerobic exercise. However, in a later review by R. Stanton et al. [58] showed that from the available research results it is impossible to draw unambiguous conclusions regarding the type of exercise therapy that is most effective in the treatment of depression. A number of other studies have drawn different conclusions.

In one of their studies [59], when comparing aerobic exercise (cycling 3 times a week for 45 minutes at the level of 60-75% of the BMD), electroconvulsive therapy and their combination after 1 month, the greatest effect on the Hamilton scale was observed with a combination of aerobic exercise and electroconvulsive therapy.

In a study by J. Krogh et al. [20] compared the results of aerobic, strength exercise and various mild exercise as a control, carried out for 4 months in 165 patients with unipolar depression. As a result, after 4 months, in patients performing strength training, the strength of the chest press increased, with aerobic exercise - MPC. In the strength group at the end of the year, the number of days of absence from work due to illness was less than in the stretching group, but the severity of depression on the Hamilton scale in these groups did not significantly differ from the control. It is possible that in this case, the group involved in light exercise, called the "stretching group" by the authors, is not the most successful control. Patients in this group performed a variety of exercises: cycling, stretching exercises and various light-intensity exercises, including throwing and catching a ball, i.e. coordination exercises. In addition, patients exercised only 2 times a week, which is probably below the effective threshold of 3 times a week [54].

We also studied the effect of acute effects of different in modality, but comparable in duration and intensity types of physical activity on mood. For example, J. Meyer et al. [60] compared the effect of bicycle ergometric load intensity chosen by patients with MDD (24 women aged 20–60 years) and prescribed load of different intensity. It turned out that the chosen intensity of bicycle ergometry leads to a smaller decrease in symptoms of depression and an increase in BDNF production after a 30-minute exercise than a bicycle ergometry prescribed by a doctor with a similar intensity. This leads to the conclusion that it is better for a patient with MDD to prescribe exercise therapy than to provide an independent choice of intensity.

Based on the hypothesis that an increase in BDNF mediates improvement in cognitive and affective areas, the effect on this indicator suggests an antidepressant effect that will be observed after long-term exposure to FN. In 2016, a meta-analysis was published [61], which compared the effects of aerobic and resistive exercise on BDNF levels in serum and plasma. The results showed that the resting peripheral blood concentration of BDNF increased after exposure to FN for at least 2 weeks. Subgroup analyzes showed a significant effect with aerobic but not resistance training. There was no significant difference in the effect in men and women, as well as differences in the content of BDNF in serum and plasma.

A comparison of the long-term effect of physical activity (without coordination exercises) with dancing, carried out in one of the works [62], showed that after 6 months of dancing in elderly people (63–80 years old), the level of BDNF increased significantly more than in the sports group, who did 20 minutes of strength, endurance and stretching exercises. Both groups worked out twice a week for 90 minutes. When studying cognitive functions, it was found that attention (after 6 months) and verbal memory (after 18 months) significantly improved in patients of both groups. When dancing, after 18 months, the volume of the parahippocampal region of the brain increased, and after 6 months, the volume of gray matter in the left precentral gyrus increased.

Regarding Eastern practices, we can mention reviews on the effects of qigong and studies on the effects of yoga on depression. Thus, a systematic review by C. Wang et al. [63] showed that qigong training reduced stress and anxiety levels in healthy adults compared to simply structured movements. Review by L. Zou et al. [64] indicates that the use of one of the types of qigong (baduanjing) in patients reduces symptoms of depression and anxiety. In addition, it was found [65] that in adults with mild to moderate depression, hatha yoga for 8 weeks led to a statistically and clinically significant decrease in the severity of depression. In another study [66], as a result of 12 weeks of Iyengar yoga combined with coherent breathing, depressive symptoms were significantly reduced in patients with MDD in groups that practiced both 2 and 3 times a week for 90 min. In the group of patients exercising 3 times a week, by the end of the study, the number of individuals who scored no more than 10 points on the BDI-II scale became more than in the group of patients exercising 2 times a week. We did not find any studies comparing the effectiveness of these types of physical activity with each other or with aerobic-resistive exercises of a similar intensity.

We did not find any studies comparing the effectiveness of these types of physical activity with each other or with aerobic-resistive exercises of a similar intensity.

When studying the effect of outdoor activities (Nordic walking) and indoor activities (gymnastics and ball games) of approximately the same intensity and duration in patients with mental illness, mainly MDD, no differences were found. In both groups, there was an improvement in mood, social interaction, and a decrease in rumination after the sessions [67].

Duration and duration of training sessions

The antidepressant effect of FN has been noted for durations of exposure ranging from 4 [19, 50] to 12 weeks [48, 51]. An improvement in mood is observed immediately after exposure to FN [68]. Speaking about the immediate (“acute”) effects of physical activity, despite some differences in load protocols, most researchers note a decrease in negative and an increase in positive affect, as well as a decrease in the physiological and psychological response to acute stress. These effects last up to 24 hours after exercise is stopped [69].

These effects last up to 24 hours after exercise is stopped [69].

Based on the results of a meta-analysis presented by A. Dinoff et al. [70], the concentration of BDNF in the peripheral blood increases after direct exposure to F.N. In this case, a longer duration of exercise is associated with a greater increase in BDNF. Subgroup analyzes showed this effect only in men, and a greater increase in plasma BDNF than in serum. The authors concluded that acute exercise increased the concentration of BDNF in the peripheral blood of healthy adults. This effect is affected by the duration of PE and may differ by gender.

In the already mentioned work of I. Zou et al. [64] showed that when applying baduanjing qigong, the effect is proportional to the number of hours of practice.

No studies were found regarding the effect of the duration of each session on depressive symptoms in patients with depression. Studies in healthy people suggest that the duration of the sessions is a positive parameter for relieving tension and anxiety. For example, a randomized controlled 2-month study [71] compared long and short episodes of walking on mood and BMD. The study involved 21 men and 19women leading a sedentary lifestyle. Walking was performed either in long (30 min) or short (10 min) episodes 3 times a day. Long walking was more effective in reducing tension and anxiety.

For example, a randomized controlled 2-month study [71] compared long and short episodes of walking on mood and BMD. The study involved 21 men and 19women leading a sedentary lifestyle. Walking was performed either in long (30 min) or short (10 min) episodes 3 times a day. Long walking was more effective in reducing tension and anxiety.

Conclusion

Thus, FN is a promising non-pharmacological treatment for depression. With its use, effects have been noted that are comparable to or even exceed other treatments for depression. At the same time, FN improves overall health. Modes and intensity of physical activity are significant factors, as they affect the improvement of mental and physical health. In addition to the antidepressant effect, cardiorespiratory training improves the state of the oxygen transport system (relevant for patients with cardiovascular and respiratory diseases), and resistance training improves muscle strength (important for sarcopenia). However, due to conflicting research results, specific recommendations regarding the type of exercise cannot yet be made. In the treatment of depression, moderate-to-intense aerobic exercise, with elements of strength training and a variety of coordination exercises, is likely to be more effective than monotonous, long-term, low-intensity exercise. It is possible that patient compliance with the prescribed exercise regimen is more important than the specific type of exercise [72].

However, due to conflicting research results, specific recommendations regarding the type of exercise cannot yet be made. In the treatment of depression, moderate-to-intense aerobic exercise, with elements of strength training and a variety of coordination exercises, is likely to be more effective than monotonous, long-term, low-intensity exercise. It is possible that patient compliance with the prescribed exercise regimen is more important than the specific type of exercise [72].

We agree with the opinion of M. Hallgren et al. [73], that there is a need to include physical activity in practical recommendations for doctors on the treatment of depression, as well as with the opinion of M. Gerber et al. [72] that physical activity assessment should be part of the routine practice of psychiatry. At the same time, in patients with depression, behavioral skills training should be used to overcome psychological barriers to the onset and regular maintenance of FN. In addition, it is important for patients with depression to create and systematically maintain favorable conditions for regular physical activity.