Exposure therapy for panic disorder

What to Expect and Effectiveness

Exposure Therapy for Anxiety: What to Expect and Effectiveness- Health Conditions

- Featured

- Breast Cancer

- IBD

- Migraine

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Articles

- Acid Reflux

- ADHD

- Allergies

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Bipolar Disorder

- Cancer

- Crohn's Disease

- Chronic Pain

- Cold & Flu

- COPD

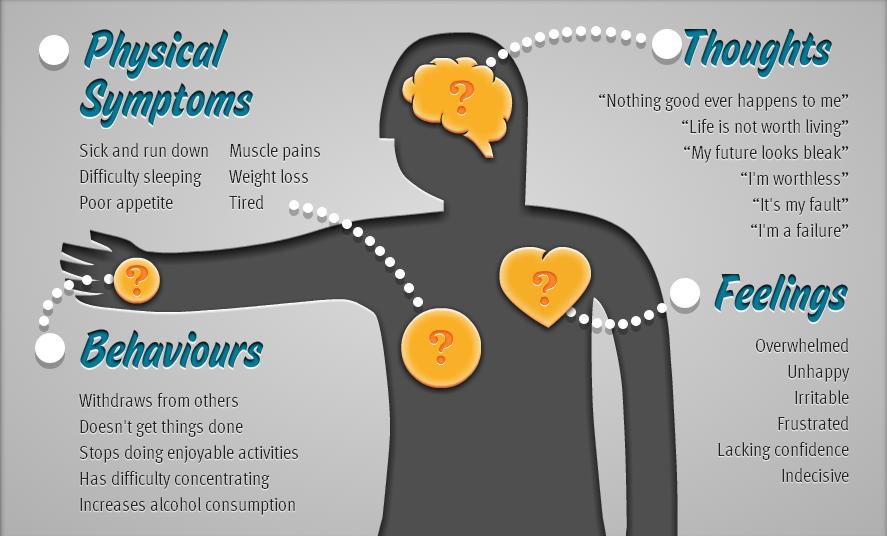

- Depression

- Fibromyalgia

- Heart Disease

- High Cholesterol

- HIV

- Hypertension

- IPF

- Osteoarthritis

- Psoriasis

- Skin Disorders and Care

- STDs

- Featured

- Discover

- Wellness Topics

- Nutrition

- Fitness

- Skin Care

- Sexual Health

- Women's Health

- Mental Well-Being

- Sleep

- Product Reviews

- Vitamins & Supplements

- Sleep

- Mental Health

- Nutrition

- At-Home Testing

- CBD

- Men’s Health

- Original Series

- Fresh Food Fast

- Diagnosis Diaries

- You’re Not Alone

- Present Tense

- Video Series

- Youth in Focus

- Healthy Harvest

- No More Silence

- Future of Health

- Wellness Topics

- Plan

- Health Challenges

- Mindful Eating

- Sugar Savvy

- Move Your Body

- Gut Health

- Mood Foods

- Align Your Spine

- Find Care

- Primary Care

- Mental Health

- OB-GYN

- Dermatologists

- Neurologists

- Cardiologists

- Orthopedists

- Lifestyle Quizzes

- Weight Management

- Am I Depressed? A Quiz for Teens

- Are You a Workaholic?

- How Well Do You Sleep?

- Tools & Resources

- Health News

- Find a Diet

- Find Healthy Snacks

- Drugs A-Z

- Health A-Z

- Health Challenges

- Connect

- Breast Cancer

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Migraine

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Psoriasis

Medically reviewed by Nicole Washington, DO, MPH — By Jaime Herndon, MS, MPH, MFA on June 10, 2021

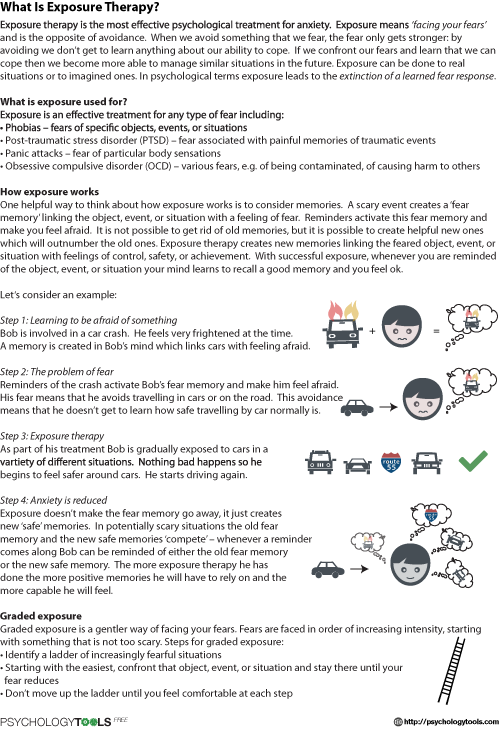

Exposure therapy is a kind of behavioral therapy that is typically used to help people living with phobias and anxiety disorders. It involves a person facing what they fear, either imagined or in real life, but under the guidance of a trained therapist in a safe environment. It can be used with people of all ages, and has been found to be effective.

Learning more about exposure therapy can help you make an informed decision about treatment and prepare you for what to expect.

In exposure therapy, a person is exposed to a situation, event, or object that triggers anxiety, fear, or panic for them. Over a period of time, controlled exposure to a trigger by a trusted person in a safe space can lessen the anxiety or panic.

There are different kinds of exposure therapies. They can include:

- In vivo exposure. This therapy involves directly facing the feared situation or activity in real life.

- Imaginal exposure. It involves vividly imagining the trigger situation in detail.

- Virtual reality exposure. This therapy can be used when in vivo exposure isn’t realistic, like if someone has a fear of flying.

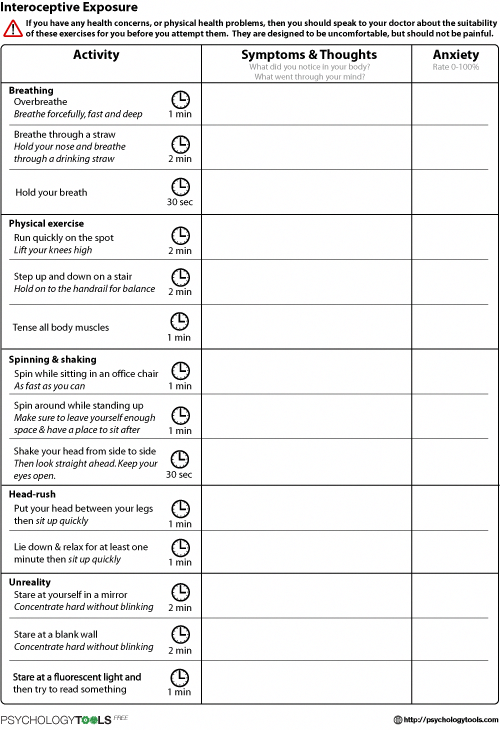

- Interoceptive exposure. This therapy involves purposefully triggering a physical sensation that is feared, but harmless.

A 2015 research review showed that within those kinds of exposure therapies there are different techniques like:

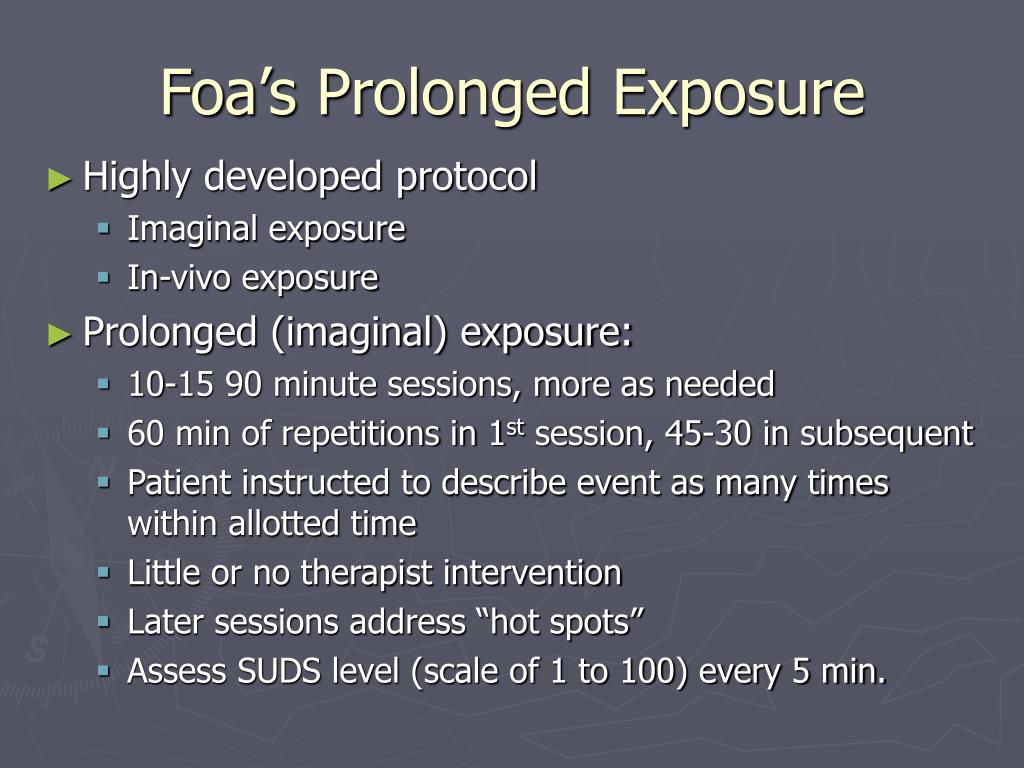

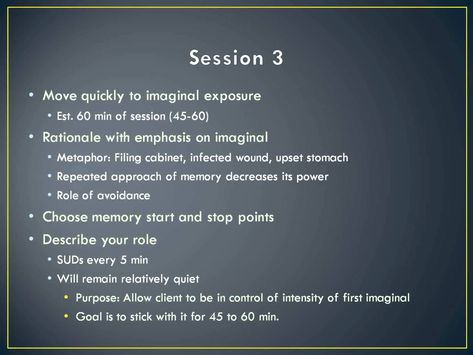

- Prolonged exposure (PE). This includes a combination of in vivo and imaginal exposure. For example, someone might repeatedly revisit a traumatic event by visualizing it, and talking about it with a therapist simultaneously, and then discussing it to gain a new perspective about the event.

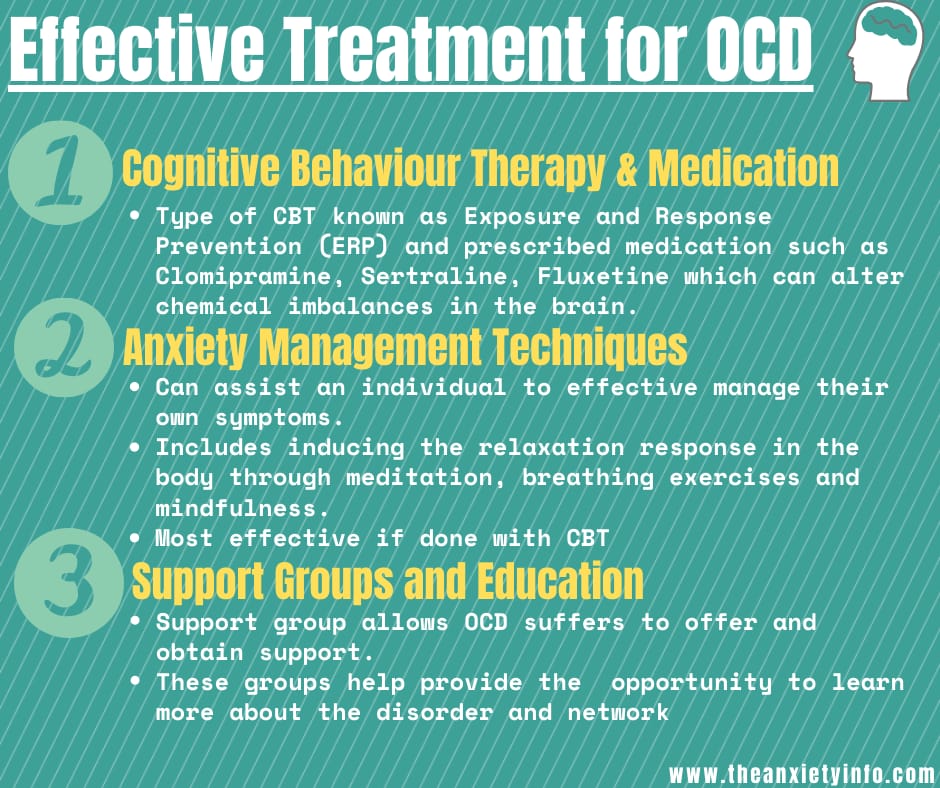

- Exposure and response prevention (EX/RP, or ERP). Typically used for people with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), this involves doing exposure homework, such as touching something considered “dirty,” and then refraining from performing the compulsive behavior that is triggered from the exposure.

Generalized anxiety

Treatment for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) can include imaginal exposure and in vivo, but in vivo exposure is not as common. The 2015 research review above showed that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and imaginal exposure improved general functioning in people with GAD compared to relaxation and nondirective therapy.

The 2015 research review above showed that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and imaginal exposure improved general functioning in people with GAD compared to relaxation and nondirective therapy.

There is not a lot of research with exposure therapy and GAD, and more is needed to further explore its effectiveness.

Social anxiety

In vivo exposure is typically used for people with social anxiety. This can include things like going to a social situation and not avoiding certain activities. The same 2015 research review above showed that exposure with or without cognitive therapy may be effective in reducing symptoms of social anxiety.

Driving anxiety

Virtual reality exposure therapy has been used to help people with a driving phobia. A small 2018 study found that it was effective in reducing driving anxiety, but more research still needs to be done with this specific phobia. Other therapies may need to be used alongside exposure therapy.

Public speaking

Virtual reality exposure therapy has been found to be effective and therapeutic to treat anxiety about public speaking for both adults and teens. One small 2020 study found that there was a significant decrease in self-rated anxiety about public speaking after a 3-hour session. These results were maintained 3 months later.

One small 2020 study found that there was a significant decrease in self-rated anxiety about public speaking after a 3-hour session. These results were maintained 3 months later.

Separation anxiety

Separation anxiety disorder is one of the most common anxiety disorders in children. Exposure therapy is considered the top treatment for it. This involves exposing the child to feared situations and, at the same time, encouraging adaptive behavior and thinking. Over time, the anxiety lessens.

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)

Exposure and response prevention (ERP) uses imaginal and in vivo exposure and is often used to help treat OCD. In vivo exposures are done in the therapy session as well as assigned for homework, and the response prevention (not engaging in compulsive behaviors) is part of that. An individual lets the anxiety decrease on its own instead of performing the behaviors that would get rid of the anxiety. When in vivo exposure is too hard or impractical, imaginal exposure is used.

While a 2015 research review showed that ERP was effective, ERP is comparable to cognitive restructuring alone and ERP with cognitive restructuring. Exposure therapy for OCD is most effective when guided by a therapist and not done independently. It’s also more effective when using both in vivo and imaginal exposure, as opposed to solely in vivo.

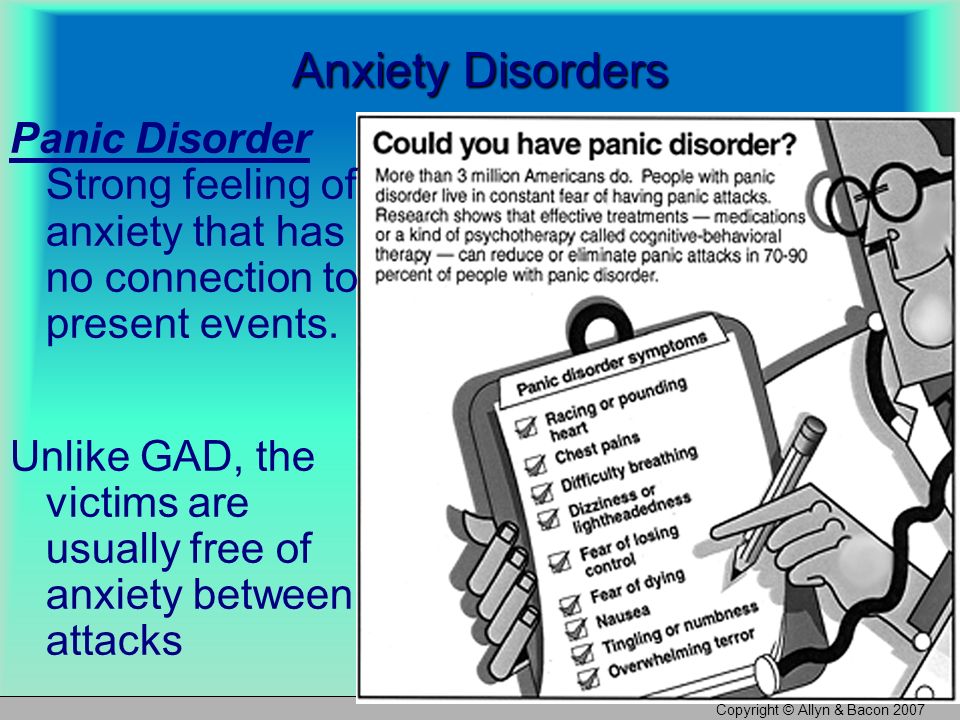

Panic disorder

Interoceptive exposure therapy is often used to treat panic disorder. According to a 2018 research review of 72 studies, interoceptive exposure and face-to-face settings, meaning working with a trained professional, were associated with better rates of effectiveness, and people were more accepting of the treatment.

Exposure therapy is effective for the treatment of anxiety disorders. According to EBBP.org, about 60 to 90 percent of people have either no symptoms or mild symptoms of their original disorder after completing their exposure therapy. Combining the exposure therapy with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), relaxation techniques, and other treatments may enhance the effectiveness as well.

As with other mental health conditions, exposure therapy may be used in conjunction with other treatments. This can depend on the severity of your anxiety disorder and your symptoms. Your therapist may suggest using exposure therapy with things like cognitive therapy or relaxation techniques.

Medication may also be helpful for some people. Talk with your therapist or doctor about what treatments may be beneficial for you along with exposure therapy.

Exposure therapy is done by psychiatrists, psychologists, and therapists with the proper training. Especially with certain kinds of exposure therapy, like prolonged exposure, it is important to work with a therapist with training in how to safely and properly use exposure therapy so that you are not caused undue distress or psychological harm.

To find a therapist who is qualified to offer exposure therapy, you can find a cognitive behavioral therapist who is part of reputable organizations like the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapists.

Ask them questions about their training and what techniques they use.

Exposure therapy is a safe and effective treatment for a variety of anxiety disorders. It can be used alone or in combination with other treatments. If you think it might help you, talk with your doctor about finding a therapist who is experienced in the technique.

Last medically reviewed on June 10, 2021

How we reviewed this article:

Healthline has strict sourcing guidelines and relies on peer-reviewed studies, academic research institutions, and medical associations. We avoid using tertiary references. You can learn more about how we ensure our content is accurate and current by reading our editorial policy.

Our experts continually monitor the health and wellness space, and we update our articles when new information becomes available.

Current Version

Jun 10, 2021

Written By

Jaime R. Herndon, MS, MPH, MFA

Edited By

Allison Tsai

Medically Reviewed By

Nicole Washington, DO, MPH

Copy Edited By

Sofia Santamarina

Share this article

Medically reviewed by Nicole Washington, DO, MPH — By Jaime Herndon, MS, MPH, MFA on June 10, 2021

Read this next

Everything You Need to Know About Anxiety

Medically reviewed by Timothy J.

Legg, PhD, PsyD

Legg, PhD, PsyDThough everyone has anxiety from time to time, for some people it’s a persistent problem. Learn about the signs of anxiety, its forms, and how to…

READ MORE

9 Useful Apps to Help with Anxiety for 2022

Anxiety comes in many forms, from manageable to very disruptive. Therapy helps, but these apps for anxiety can give extra support when you’re…

READ MORE

Everything You Need to Know About Stress and Anxiety

Medically reviewed by Kendra Kubala, PsyD

While stress and anxiety are very similar, they have a few key differences. Learn how each one shows up and how to manage symptoms.

READ MORE

Social Anxiety Disorder Treatment Options

Social anxiety can cause shaking, sweating, a rapid heart rate, and flushing.

But you can treat it, including talk therapy, medications, and…

But you can treat it, including talk therapy, medications, and…READ MORE

Using CBD Oil for Anxiety: Does It Work?

Medically reviewed by Alan Carter, Pharm.D.

Find out what the research says about CBD oil and anxiety. Also get the facts on how it affects other disorders and its legal status.

READ MORE

How to Ease Anxiety at Night

Anxiety at night when trying to sleep may cause racing thoughts and physical symptoms. Sleep deprivation can also trigger it. Here's how to calm it…

READ MORE

Will Prozac Work for Your Anxiety?

Prozac (fluoxetine) is a brand-name medication prescribed to treat depression, OCD, and anxiety. We explain how it works and why it may help treat…

READ MORE

The Best Anxiety Tools: An Expert’s Advice

Medically reviewed by Karin Gepp, PsyD

From essential oils to journals to meditation apps, you have plenty of options for tools to help ease anxiety symptoms.

Check out our top picks.

Check out our top picks.READ MORE

How to Recognize Selective Mutism and Tips to Get Support

Medically reviewed by Mia Armstrong, MD

The main sign of selective mutism is the inability to speak in certain situations. Get the details on this anxiety condition and how to treat it.

READ MORE

Yes, Adults Can Have Selective Mutism — Learn the Causes and How to Cope

Medically reviewed by Kendra Kubala, PsyD

Selective mutism is a type of anxiety where you can't speak in certain contexts. Though most common in children, it can also affect adults.

READ MORE

Exposure Therapy for Anxiety Disorders

Exposure-based therapies are highly effective for patients with anxiety disorders, to the extent that exposure should be considered a first-line, evidence-based treatment for such patients. In clinical practice, however, these treatments are underutilized, which highlights the need for additional dissemination and training.

In clinical practice, however, these treatments are underutilized, which highlights the need for additional dissemination and training.

Over a quarter of the people in the US population will have an anxiety disorder sometime during their lifetime.1 It is well established that exposure-based behavior therapies are effective treatments for these disorders; unfortunately, only a small percentage of patients are treated with exposure therapy.2,3 For example, in the Harvard/Brown Anxiety Research Project, only 23% of treated patients reported receiving even occasional imaginal exposure and only 19% had received even occasional in vivo exposure.4 In part, this may be a lack of well-trained professionals, because most mental health clinicians do not receive specialized training in exposure-based therapies.5,6

Another factor may be that many health care professionals do not understand the principles of exposure or may even hold (usually unfounded) negative beliefs about this form of treatment. Surveys of psychologists who treat patients with PTSD show that the majority do not use exposure therapy and most believe that exposure therapy is likely to exacerbate symptoms.7,8 However, individuals with trauma histories and PTSD express a preference for exposure therapy over other treatments.9 Furthermore, exposure therapy does not appear to lead to symptom exacerbation or treatment discontinuation.10 Indeed, a wealth of evidence indicates that exposure-based therapy is associated with improved symptomatic and functional outcomes for patients with PTSD.11

Surveys of psychologists who treat patients with PTSD show that the majority do not use exposure therapy and most believe that exposure therapy is likely to exacerbate symptoms.7,8 However, individuals with trauma histories and PTSD express a preference for exposure therapy over other treatments.9 Furthermore, exposure therapy does not appear to lead to symptom exacerbation or treatment discontinuation.10 Indeed, a wealth of evidence indicates that exposure-based therapy is associated with improved symptomatic and functional outcomes for patients with PTSD.11

The available research literature suggests that exposure-based therapy should be considered the first-line treatment for a variety of anxiety disorders. Here we review a handful of the most influential studies that demonstrate the efficacy of exposure therapy. We also discuss theoretical mechanisms, practical applications, and empirical support for this treatment and provide practical guidelines for clinicians who wish to use exposure therapy and empirical evidence to guide their decision making.

Exposure therapy is defined as any treatment that encourages the systematic confrontation of feared stimuli, which can be external (eg, feared objects, activities, situations) or internal (eg, feared thoughts, physical sensations). The aim of exposure therapy is to reduce the person’s fearful reaction to the stimulus.

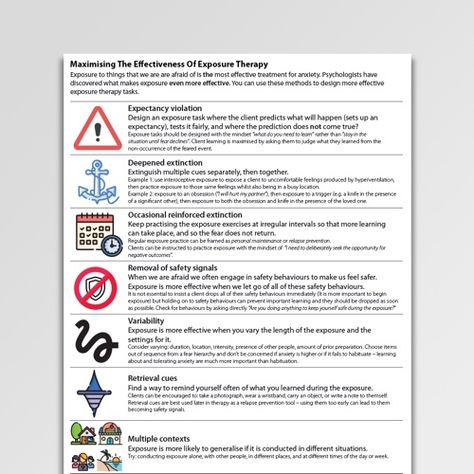

Graded exposure vs flooding

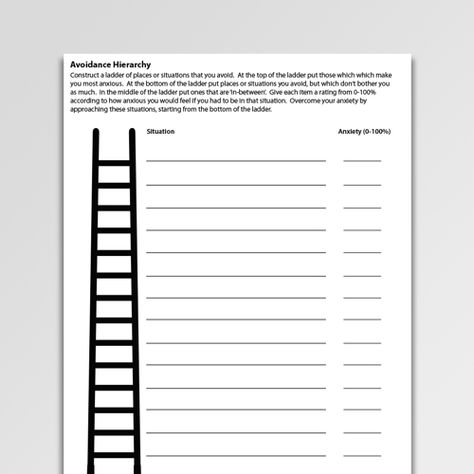

Most exposure therapists use a graded approach in which mildly feared stimuli are targeted first, followed by more strongly feared stimuli. This approach involves constructing an exposure hierarchy in which feared stimuli are ranked according to their anticipated fear reaction (Table 1). Traditionally, higher-level exposures are not attempted until the patient’s fear subsides for the lower-level exposure. By contrast, some therapists have used flooding, in which the most difficult stimuli are addressed from the beginning of treatment (an older variant, implosive therapy, is not discussed in this article). In clinical practice, these approaches appear equally effective; however, most patients and clinicians choose a graded approach because of the personal comfort level.12,13

In clinical practice, these approaches appear equally effective; however, most patients and clinicians choose a graded approach because of the personal comfort level.12,13

In vivo vs imaginal

In vivo exposure refers to real-world confrontation of feared stimuli. Sometimes, in vivo exposure is not feasible (eg, it would be both difficult and hazardous for someone with combat-related PTSD to experience the sights, sounds, and smells of combat in real life). In such cases, imaginal exposure can be a useful alternative. In imaginal exposure, the patient is asked to vividly imagine and describe the feared stimulus (in this case, a traumatic memory), usually using present-tense language and including details about external (eg, sights, sounds, smells) and internal (eg, thoughts, emotions) cues.

In recent years, virtual reality exposure therapy (patients are immersed in a virtual world that allows them to confront their fears) has been examined as an alternative means of imaginal exposure, and preliminary data suggest that it can be quite effective. 14,15 Imaginal exposures can also be useful for confronting fears of worst-case scenarios (eg, patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder [OCD] who imagine that they might contract a deadly illness, patients with social phobia who imagine that they are being ridiculed) to reduce the aversiveness of the thought.

14,15 Imaginal exposures can also be useful for confronting fears of worst-case scenarios (eg, patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder [OCD] who imagine that they might contract a deadly illness, patients with social phobia who imagine that they are being ridiculed) to reduce the aversiveness of the thought.

What is already known about exposure therapy for anxiety disorder?

? Exposure therapy is defined as any treatment that encourages the systematic confrontation of feared stimuli, with the aim of reducing a fearful reaction. Over a quarter of the people in the US population will have an anxiety disorder sometime during their lifetime, and available research literature suggests that exposure-based therapies should be considered the first-line treatment for these disorders. Although it is well established that exposure-based therapies are effective treatments for these disorders, however, only a small percentage of patients are actually treated with this approach.

What new information does this article provide?

? We review the results of a handful of the most influential studies that demonstrate the efficacy of exposure therapy and disseminate information about the theoretical mechanisms, practical applications, and empirical support for this treatment. In addition, we provide practical guidelines for clinicians who wish to use exposure-based therapies and empirical evidence to guide their decision making.

What are the implications for psychiatric practice?

? In clinical practice, exposure-based therapies for anxiety disorders are underutilized, which highlights the need for additional dissemination and training. We hope the dissemination of the theoretical mechanisms, practical applications, and empirical support for exposure-based therapies in this article will encourage mental health practitioners to embrace this modality as a viable and easily accessible option in the treatment of anxiety disorders.

Internal vs external

Exposures can target internal and/or external cues. Exposures to external cues include a spider-phobic patient handling a spider, or a height-phobic patient systematically approaching increasing heights in a skyscraper. Using exposure to internal cues, a patient with panic disorder can run in place to experience physiological sensations (eg, heart palpitations) that elicit anxious reactions, a patient with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) can purposefully induce worry thoughts, a patient with PTSD can revisit traumatic memories, and a patient with OCD can intention-ally evoke intrusive and aversive thoughts.

With or without relaxation

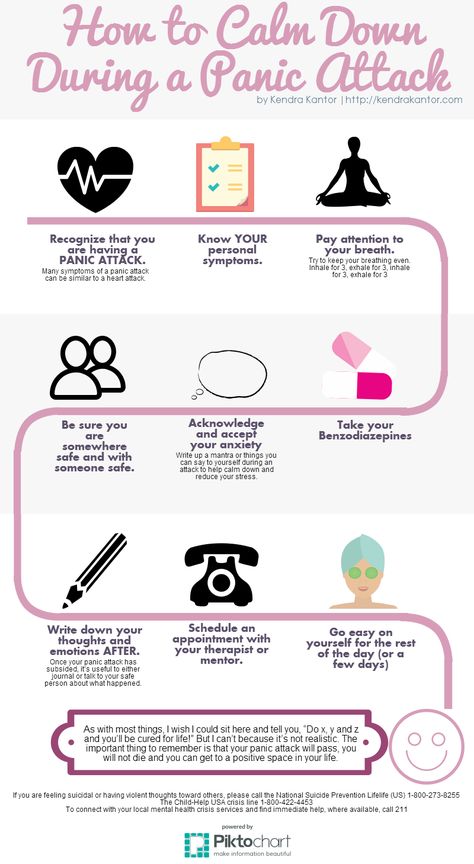

One of the earliest variations of exposure therapy was systematic desensitization, in which patients engage in imaginal exposure to feared stimuli while simultaneously undergoing progressive muscle relaxation.16 Subsequent dismantling studies have shown that exposure, rather than relaxation, is the active ingredient and that relaxation does not improve outcomes. 17 The addition of relaxation exercises has been counterproductive in some patients, such as those with panic disorder.18 Because of the apparent importance of interoceptive exposure (ie, learning to tolerate uncomfortable physical sensations), relaxation exercises aimed at decreasing these sensations may actually attenuate the outcome of therapy, in much the same way as does the use of as-needed short-acting benzodiazepines.19

17 The addition of relaxation exercises has been counterproductive in some patients, such as those with panic disorder.18 Because of the apparent importance of interoceptive exposure (ie, learning to tolerate uncomfortable physical sensations), relaxation exercises aimed at decreasing these sensations may actually attenuate the outcome of therapy, in much the same way as does the use of as-needed short-acting benzodiazepines.19

Efficacy of exposure therapy

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of exposure-based therapies for anxiety disorders, a finding that is summarized in several published meta-analyses.20,21 st22 examined the effects of single-session in vivo exposure (that lasts 1 to 3 hours) for patients with specific phobias. At posttreatment follow-up (after an average of 4 years), 90% of these patients still had significant reduction in fear, avoidance, and overall level of impairment and 65% no longer had a specific phobia.

Barlow and colleagues23 investigated the effects of interoceptive exposure with components of cognitive restructuring (cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]), imipramine, and a combination of the two in patients with panic disorder. At first, all treatments appeared equally efficacious; however, at 6 months’ follow-up, 32% of patients in the CBT group continued to maintain their treatment gains compared with 20% in the imipramine group and 24% in the combined-treatment group.

Foa and colleagues24 randomized patients with OCD to receive in vivo exposure and response prevention, clomipramine, or a combination of both. For patients who completed the study, 86% in the exposure group improved on a measure that examined the frequency and severity of obsessions and compulsions compared with 48% in the clomipramine group and 79% in the combined-treatment group.

Several others have also demonstrated the efficacy of exposure-based treatments or treatment components for patients with GAD, so-cial anxiety disorder, and PTSD. 25-27

25-27

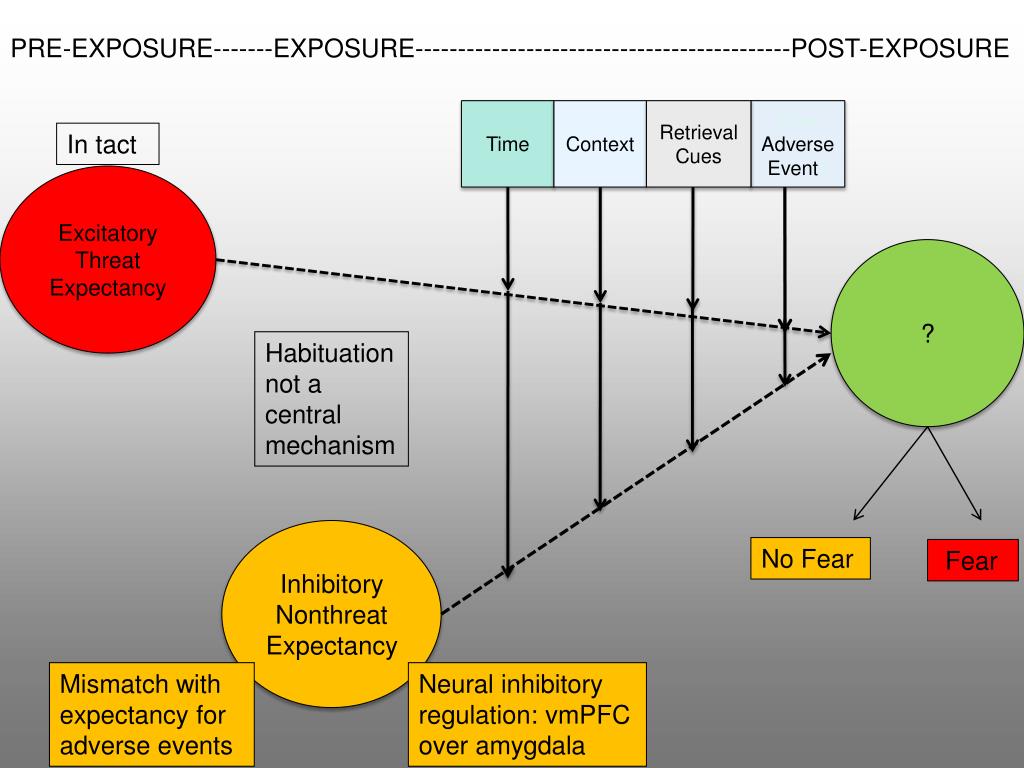

Theoretical mechanisms of exposure therapy

Biologically, the extinction of fear appears to be mediated by N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor activity in the basolateral amygdala, a finding that has led to the use of neuroplasticity compounds such as d-cycloserine to augment exposure.28,29 There are 4 major theories that attempt to explain the psychological mechanisms of exposure therapy: habituation, extinction, emotional processing, and self-efficacy (Table 2).

Habituation theory purports that after repeated presentations of a stimulus, the response to that stimulus will decrease.30 For example, initial exposure to ocean water can be cold. However, over time and with repeated exposures, the water feels less cold as the person acclimates. Similarly, when repeatedly facing a fear-provoking stimulus in exposure therapy, the patient experiences habituation, or a natural reduction in fear response. While many clinicians aim for habituation to occur within the session, researchers have found that optimal treatment effects occur during the period of learning consolidation between sessions.31,32

While many clinicians aim for habituation to occur within the session, researchers have found that optimal treatment effects occur during the period of learning consolidation between sessions.31,32

Extinction theory emerges from a classic conditioning model in which the unconditioned stimulus is a situation, place, or person that initially caused fear (the unconditioned response)-for example, a dog bite. Through the process of stimulus generalization, fear reactions become learned (conditioned response) and are elicited by other stimuli, such as dogs that are not dangerous (conditioned stimuli). Because of the aversiveness of the conditioned response, fearful individuals are motivated to avoid the conditioned stimuli, thus reinforcing avoidance behavior as well as the belief that relief from fear only comes from avoidance.33

Exposure therapy is thought to weaken the conditioned response through repeated exposure to the conditioned stimuli in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus. For example, exposure to dogs (conditioned stimuli) without being bitten (absence of unconditioned stimulus) weakens the relationship between the conditioned stimuli and the fear of conditioned response. One limitation of extinction theory is that most phobic patients do not identify an initial conditioning event.34

For example, exposure to dogs (conditioned stimuli) without being bitten (absence of unconditioned stimulus) weakens the relationship between the conditioned stimuli and the fear of conditioned response. One limitation of extinction theory is that most phobic patients do not identify an initial conditioning event.34

Emotional processing theory suggests that fear is stored in memory as a network of stimuli (eg, social gathering), response (eg, sweaty palms), and meaning (eg, “I’m not good at socializing, I’m a failure”) components.35 Fearful individuals are thought to ascribe faulty meanings to stimuli in a way that increases fear toward those stimuli. Exposure to fear-provoking stimuli is thought to result in a new way of processing information and to correct the faulty fear structure.36,37 For example, in patients with social anxiety disorder, social interactions can be perceived as rewarding, even if the patients have sweaty palms and feel some anxiety.

The self-efficacy theory focuses more on increasing skills and mastery over a situation or performance than on reducing a fear response directly.38 Persons with anxiety disorders tend to underestimate their capabilities to cope with fear. Therefore, persons able to face their fear and successfully tolerate it without avoiding it or withdrawing from it begin to realize they are more capable and resilient than they had imagined. Thus, they become more willing to face their fears in different contexts, thereby generalizing treatment effects.

These theoretical mechanisms of exposure are not mutually exclusive, and all might be correct for any given patient. With repeated exposures, patients experience reduced sensations of fear (habituation), learn a new set of associations (extinction), feel increasingly able to cope with fear (self-efficacy), and generate new interpretations of the meanings of previously feared stimuli (emotional processing).

Treatment guidelines

Treatment guidelines for clinicians who use exposure therapy are shown in Table 3. The first step in successful exposure therapy is the development of an exposure hierarchy. The patient and clinician brainstorm as many feared external and internal stimuli as possible and then rate them in order of difficulty. The most common ranking method is the Subjective Units of Discomfort (SUD) scale, which assigns a 0 to 100 numeric value to each item.39 (This scale can be found online in Wikipedia and at http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Joseph-Wolpe.)

The first step in successful exposure therapy is the development of an exposure hierarchy. The patient and clinician brainstorm as many feared external and internal stimuli as possible and then rate them in order of difficulty. The most common ranking method is the Subjective Units of Discomfort (SUD) scale, which assigns a 0 to 100 numeric value to each item.39 (This scale can be found online in Wikipedia and at http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Joseph-Wolpe.)

The next step is to conduct exposures in a gradual and systematic manner. Repeated use of the SUD scale will help track the patient’s fear level as it increases and decreases. Typically, a higher item is not attempted until the patient’s SUD level decreases significantly for a lower-ranked item.

During exposure therapy, safety behaviors should be eliminated to the extent possible. Safety behaviors refer to all unnecessary actions the patient takes to feel better or to prevent feared catastrophes. Left unchecked, safety behaviors can undermine the process of exposure therapy by teaching the patient a rule of conditional safety (eg, “The only way to be safe during a panic attack is to have my medication with me”) rather than a rule of unconditional safety (eg, “Panic attacks will not harm me, regardless of whether I am carrying my medications”).

Cognitive restructuring may also be used as an adjunct to exposure therapy. Cognitive restructuring refers to identifying and challenging irrational, unrealistic, or maladaptive beliefs. In patients with anxiety disorders, 2 of the more common faulty thinking patterns (ie, cognitive distortions) are probability overestimation and catastrophizing. Probability overestimation refers to the overprediction of unlikely outcomes, such as the belief that a commercial flight is highly likely to crash. Catastrophizing refers to the magnification of the consequences of aversive outcomes, such as the belief that making a mistake during a speech will lead to a lifetime of ridicule and ostracism. During the process of exposure exercises, the therapist helps the patient identify these cognitive distortions; examine the evidence for and against the beliefs; and rehearse new, more realistic ways of thinking.

Conclusion

Exposure-based therapies are highly effective for patients with anxiety disorders, to the extent that exposure should be considered a first-line, evidence-based treatment for such patients. In clinical practice, however, these treatments are underutilized, which highlights the need for additional dissemination and training. We hope this information will encourage clinicians to embrace exposure-based therapies for anxiety disorders as a viable and easily accessible treatment option.

In clinical practice, however, these treatments are underutilized, which highlights the need for additional dissemination and training. We hope this information will encourage clinicians to embrace exposure-based therapies for anxiety disorders as a viable and easily accessible treatment option.

References:

References

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication [published correction appears in Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:768]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593-602.

2. Torres AR, Prince MJ, Bebbington PE, et al. Treatment seeking by individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder from the British Psychiatric Morbidity Survey of 2000. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:977-982.

3. Mancebo MC, Eisen JL, Pinto A, et al. The brown longitudinal obsessive compulsive study: treatments received and patient impressions of improvement. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1713-1720.

J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1713-1720.

4. Goisman RM, Rogers MP, Steketee GS, et al. Utilization of behavioral methods in a multicenter anxiety disorders study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:213-218.

5. Davison GC. Being bolder with the Boulder model: the challenge of education and training in empirically supported treatments. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:163-167.

6. Crits-Christoph P, Frank E, Chambless DL, et al. Training in empirically validated treatments: what are clinical psychology students learning? Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1995;26:514-522.

7. Becker CB, Zayfert C, Anderson E. A survey of psychologists’ attitudes towards and utilization of exposure therapy for PTSD. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:277-292.

8. van Minnen A, Hendriks L, Olff M. When do trauma experts choose exposure therapy for PTSD patients? A controlled study of therapist and patient factors. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:312-320.

Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:312-320.

9. Becker CB, Darius E, Schaumberg K. An analog study of patient preferences for exposure versus alternative treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:2861-2873.

10. Foa EB, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC, et al. Does imaginal exposure exacerbate PTSD symptoms? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:1022-1028.

11. Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, et al. Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: outcome at academic and community clinics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:953-964.

12. Ost LG, Alm T, Brandberg M, Breitholtz E. One vs five sessions of exposure and five sessions of cognitive therapy in the treatment of claustrophobia. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:167-183.

13. Moulds ML, Nixon RD. In vivo flooding for anxiety disorders: proposing its utility in the treatment posttraumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20:498-509.

J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20:498-509.

14. Michaliszyn D, Marchand A, Bouchard S, et al. A randomized, controlled clinical trial of in virtuo and in vivo exposure for spider phobia. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13:689-695.

15. Meyerbröker K, Emmelkamp PM. Virtual reality exposure therapy in anxiety disorders: a systematic review of process-and-outcome studies. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:933-944.

16. Wolpe J. The systematic desensitization treatment of neuroses. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1961;132:189-203.

17. Telch MJ, Lucas JA, Schmidt NB, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behav Res Ther. 1993;31:279-287.

18. Schmidt NB, Woolaway-Bickel K, Trakowski J, et al. Dismantling cognitive-behavioral treatment for panic disorder: questioning the utility of breathing retraining. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:417-424.

19. Westra HA, Stewart SH, Conrad BE. Naturalistic manner of benzodiazepine use and cognitive behavioral therapy outcome in panic disorder with agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16:233-246.

Westra HA, Stewart SH, Conrad BE. Naturalistic manner of benzodiazepine use and cognitive behavioral therapy outcome in panic disorder with agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16:233-246.

20. Norton PJ, Price EC. A meta-analytic review of adult cognitive-behavioral treatment outcome across the anxiety disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:521-531.

21. Tolin DF. Is cognitive-behavioral therapy more effective than other therapies? A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:710-720.

22. Ãst LG. One-session treatment for specific phobias. Behav Res Ther. 1989;27:1-7.

23. Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, Woods SW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: a randomized controlled trial [published corrections appear in JAMA. 2000;284:2450; JAMA. 2000;284:2597]. JAMA. 2000;283:2529-2536.

24. Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:151-161.

Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:151-161.

25. Borkovec TD, Costello E. Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:611-619.

26. Gerardi M, Cukor J, Difede J, et al. Virtual reality exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder and other anxiety disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:298-305.

27. Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, et al. Cognitive behavioral group therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social phobia: 12-week outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:1133-1141.

28. Davis M. Role of NMDA receptors and MAP kinase in the amygdala in extinction of fear: clinical implications for exposure therapy. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:395-398.

Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:395-398.

29. Norberg MM, Krystal JH, Tolin DF. A meta-analysis of D-cycloserine and the facilitation of fear extinction and exposure therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:1118-1126.

30. Groves PM, Thompson RF. Habituation: a dual-process theory. Psychol Rev. 1970;77:419-450.

31. Lang AJ, Craske MG. Manipulations of exposure-based therapy to reduce return of fear: a replication. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:1-12.

32. Rowe MK, Craske MG. Effects of varied-stimulus exposure training on fear reduction and return of fear. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:719-734.

33. Mowrer OH. Learning Theory and Behavior. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1960.

34. Rachman S. The conditioning theory of fear-acquisition: a critical examination. Behav Res Ther. 1977;15:375-387.

35. Lang PJ. The application of psychophysiological methods to the study of psychotherapy and behavior modification. In: Bergin AE, Garfield SL, eds. Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. New York: Wiley; 1971:75-125.

In: Bergin AE, Garfield SL, eds. Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. New York: Wiley; 1971:75-125.

36. Foa EB, Kozak MJ. Emotional processing of fear: exposure to corrective information. Psychol Bull. 1986;99:20-35.

37. Craske MG, Kircanski K, Zelikowsky M, et al. Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:5-27.

38. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191-215.

39. Wolpe J. The Practice of Behavior Therapy. 4th ed. New York: Pergamon Press; 1990.

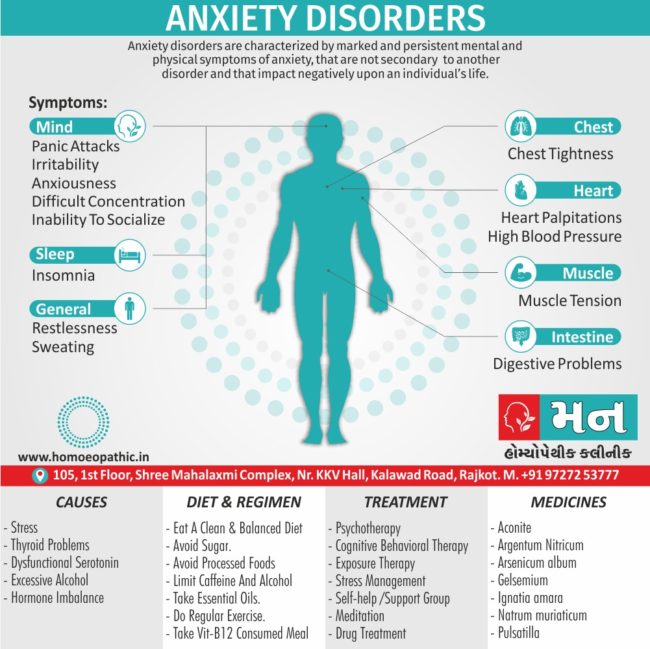

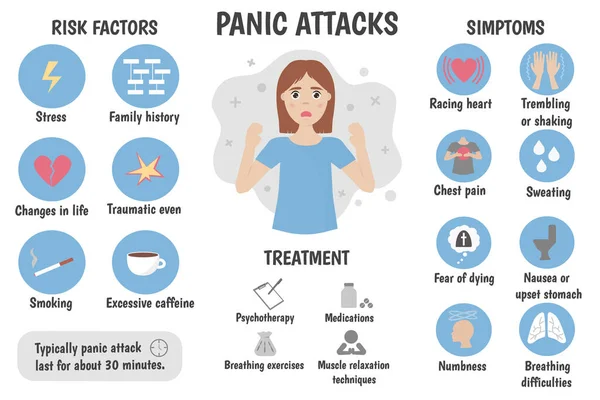

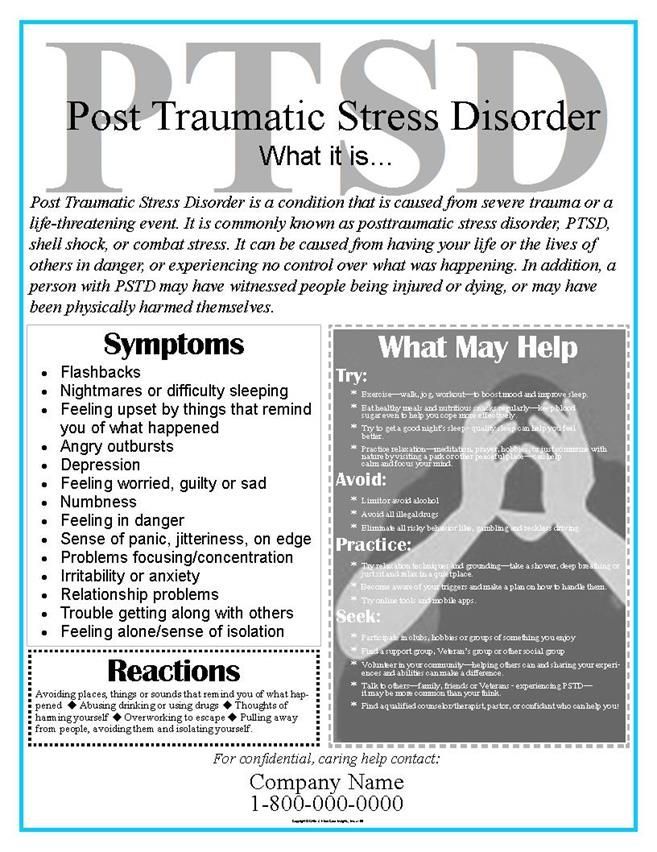

What is panic disorder? They lead to constant worrying and avoidance behavior in an attempt to prevent situations.

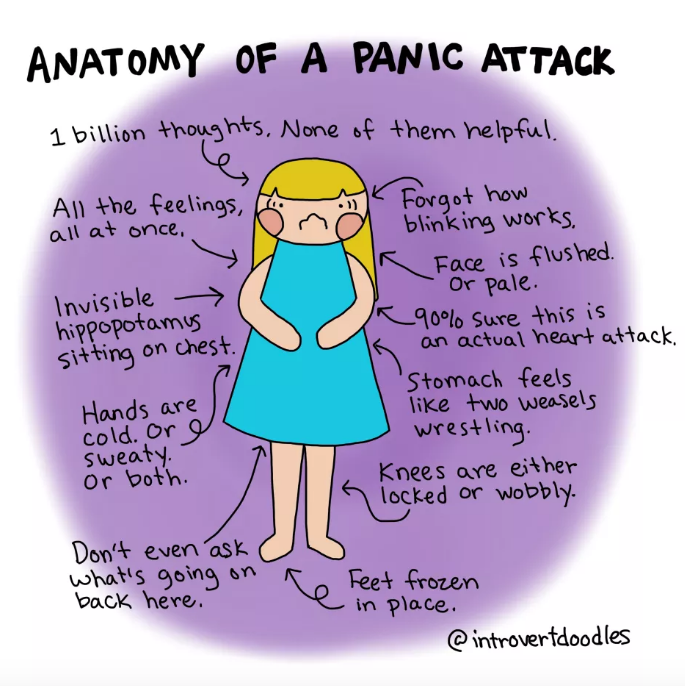

Panic attacks are characterized by the sudden, sudden onset of intense fear or terror and occur for no apparent reason. These attacks often occur in people with breathing problems such as asthma and in people experiencing bereavement or separation anxiety. While about 10% of people experience one panic attack in their lifetime, the recurring attacks that make up panic disorder are less common; the disorder occurs in about 1-3% of people in developed countries. Panic disorder usually occurs in adults, although it can also affect children. It is more common in women than men and tends to run in families.

While about 10% of people experience one panic attack in their lifetime, the recurring attacks that make up panic disorder are less common; the disorder occurs in about 1-3% of people in developed countries. Panic disorder usually occurs in adults, although it can also affect children. It is more common in women than men and tends to run in families.

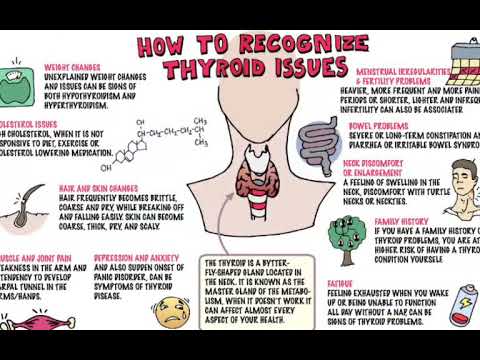

The main cause of panic disorder appears to be a combination of genetic and environmental factors. One of the most significant genetic variations that have been identified in connection with panic disorder is a mutation in a gene designated HTR2A (5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2A). This gene encodes a receptor protein in brain , which binds serotonin, a neurotransmitter that plays an important role in mood regulation. People with this genetic variant may be susceptible to irrational fears or thoughts that can trigger a panic attack.

Environmental and genetic factors also underlie the suffocation false alarm theory. People who suffer from panic disorder seem to have an increased sensitivity to these alarm signals, which cause an increased sense of anxiety. This heightened sensitivity leads to the misinterpretation of non-dangerous situations as terrifying events. nine0003

People who suffer from panic disorder seem to have an increased sensitivity to these alarm signals, which cause an increased sense of anxiety. This heightened sensitivity leads to the misinterpretation of non-dangerous situations as terrifying events. nine0003

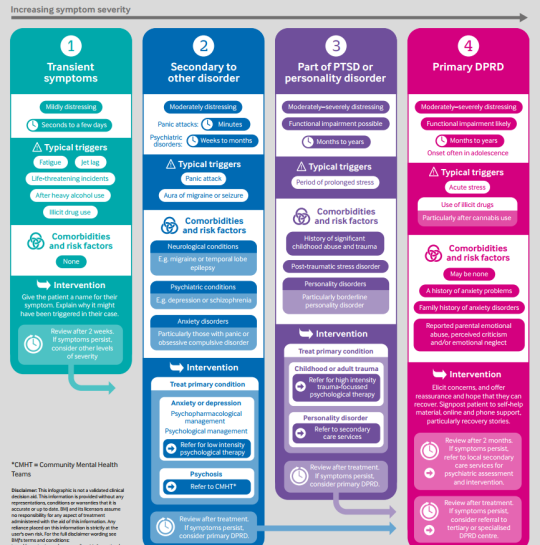

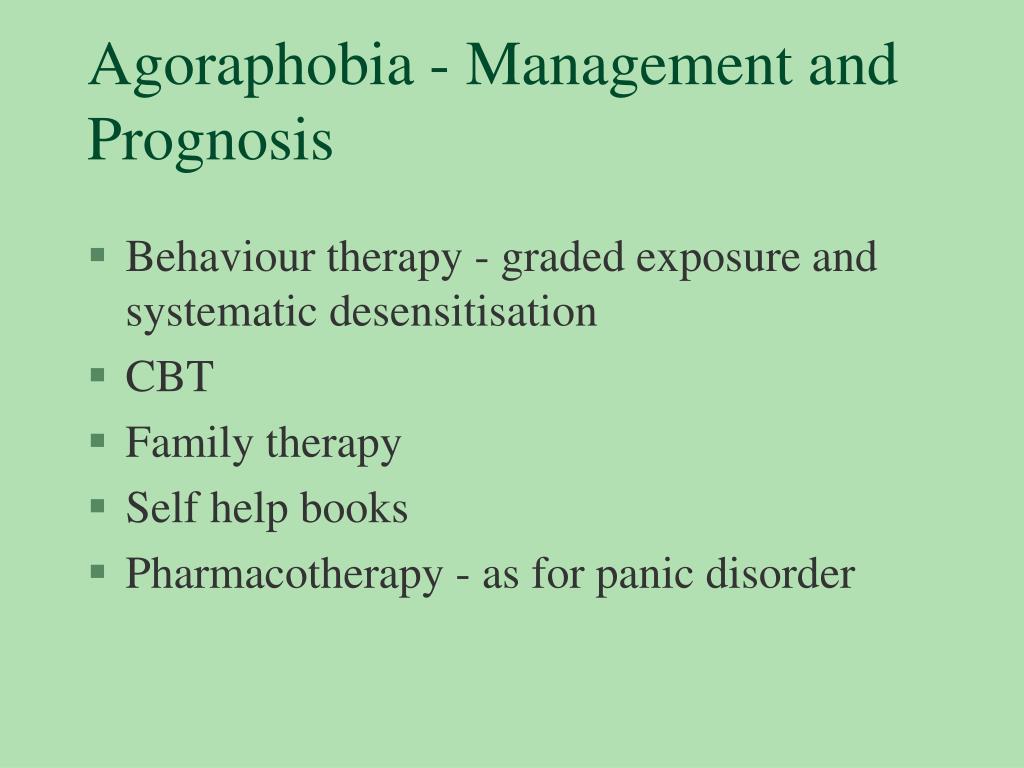

Altered activity of neurotransmitters such as serotonin can lead to depression . Thus, there is a strong association between panic disorder and depression and a large percentage of people with panic disorder continue to experience severe depression over the next few years. In addition, about 50% of people with panic disorder develop agoraphobia, an abnormal fear of open or public places associated with disturbing situations or events. nine0003 Since persistent anxiety and avoidance behavior are the main characteristics of panic disorder, many patients benefit from cognitive therapy . This form of therapy typically consists of developing skills and behaviors that enable the patient to cope with panic attacks and prevent them. These agents may also provide effective relief from associated depressive symptoms. Published in Psychotherapy Premium Clinic and Clinics of Psychiatry and Narcology Dr. SUN. nine0003 Panic disorder or episodic paroxysmal anxiety is a mental disorder characterized by the spontaneous onset of panic attacks from several times a year to several times a day and the expectation of their occurrence, which are accompanied by certain neurovegetative symptoms. A characteristic feature of the disorder is recurrent attacks of severe anxiety (panic), which are not limited to a particular situation or circumstances and, therefore, are unpredictable. nine0003 Create a therapeutic alliance Perform patient assessment EXAMINATION OF A PATIENT WITH PANIC DISORDER SOMATIC DISEASES THAT OCCUR IN PANIC DISORDER MORE MORE THAN IN THE GENERAL POPULATION Make a personalized treatment plan Assess patient safety SUICIDE RISK ASSESSMENT IN PATIENTS WITH PANIC DISORDER Assess the type and degree of functional impairment Define treatment goals Monitor the patient's mental status Educate the patient and, if appropriate, family members Coordinate with other doctors Manage patient adherence FACTORS WEAKENING TREATMENT ADHERENCE Work with the patient about possible relapse Decide where the treatment will take place. nine0068 Choose a treatment FACTORS TO CONSIDER IN THE CHOICE OF INITIAL TREATMENT General factors Factors in favor of psychosocial treatment Factors favoring pharmacotherapy Factors in favor of combined treatment Factors to consider when choosing pharmacotherapy FACTORS TO CONSIDER WHEN CHOOSING A DRUG FOR THE TREATMENT OF PANIC DISORDER Factors to consider when choosing psychotherapy FACTORS TO CONSIDER WHEN CHOOSING PSYCHOTHERAPY FOR THE TREATMENT OF PANIC DISORDER  Exposure therapy is a type of cognitive therapy in which patients repeatedly face their fears. It may be effective in patients with panic disorder who also suffer from agoraphobia. nine0003

Exposure therapy is a type of cognitive therapy in which patients repeatedly face their fears. It may be effective in patients with panic disorder who also suffer from agoraphobia. nine0003 Treatment of panic disorder (APA clinical guidelines)

g. caffeine) that may produce physiological effects and exacerbate panic symptoms

g. caffeine) that may produce physiological effects and exacerbate panic symptoms

nine0068

nine0068

Extensive and specialized testing for physical causes of panic attacks is not usually indicated, but may be done based on the individual patient. nine0068

Extensive and specialized testing for physical causes of panic attacks is not usually indicated, but may be done based on the individual patient. nine0068

908

g. mirtazapine, anticonvulsants such as gabapentin) may be considered as a monotherapy option or added to primary therapy in special cases or when several standard approaches have failed.

g. mirtazapine, anticonvulsants such as gabapentin) may be considered as a monotherapy option or added to primary therapy in special cases or when several standard approaches have failed.

Stabilize medication dose

- Patients with panic disorder may be sensitive to side effects, so SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs are recommended to be started at low doses (approximately half the initial dose given to patients with depression).

After a few days of administration, the initial dose should be gradually increased to a therapeutic dose if there are no problems with the tolerability of the drug. nine0068

After a few days of administration, the initial dose should be gradually increased to a therapeutic dose if there are no problems with the tolerability of the drug. nine0068 - Underdosing of an antidepressant (i.e. starting treatment at a low dose without subsequently increasing to a therapeutic dose) is a common occurrence in the treatment of panic disorder and often results in an incomplete response to treatment or no response.

- When benzodiazepines are prescribed, patients with panic disorder should be treated on a scheduled basis rather than on an on-demand basis. The goal is not to relieve symptoms once the panic attack has already begun, but to prevent the panic attack. nine0068

- After starting medication, patients are usually seen every 1-2 weeks, then every 2-4 weeks until the dose stabilizes. Once the dose has stabilized and symptoms have subsided, the occurrence may be less frequent.

ANTIDEPRESSANT AND BENZODIAZEPINE DOSES FOR PANIC DISORDER

| Starting dose and step up (mg/day) | Therapeutic dose a | |

| SSRI | ||

| Citalopram | 10 | 20-40 |

| Escitalopram | 5-10 | 10-20 |

| Fluoxetine | 5-10 | 20-40 |

| Fluvoxamine | 25-50 | 100-200 |

| Paroxetine | 10 | 20-40 |

| Controlled release paroxetine | 12. 5 5 | 25-50 |

| Sertraline | 25 | 100-200 |

| SNRI | ||

| Duloxetine | 20-30 | 60-120 |

| Venlafaxine extended release | 37.5 | 150-225 |

| TCA | ||

| Imipramine | 10 | 100-300 |

| Clomipramine | 10-25 | 50-150 |

| Desipramine | 25-50 | 100-200 |

| Nortriptyline | 25 | 50-150 |

| Benzodiazepines | ||

| Alprazolam | 0.75-1.0 b | 2-4 b |

| Clonazepam | 0.5-1.0 c | 1-2 c |

| Lorazepam | 1.5-2.0 b | 4-8 b |

a Higher doses are used when the patient does not respond to the usual therapeutic dose.

b Usually divided into 3-4 doses throughout the day.

c Often divided into 2 doses throughout the day.

SAFETY IN THE PHARMACOTHERAPY OF PANIC DISORDER

| Preparations | Hazards | Recommendations |

| SSRI | Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts | Watch for thoughts of self-harm or suicide, and for side effects (e.g. anxiety, agitation, insomnia, irritability) that may prompt such behavior. |

| Upper GI bleeding | Be aware of increased risk, especially when SSRIs are taken with NSAIDs or aspirin. nine0519 | |

| Falls and fractures | Use with caution in elderly patients. | |

| SNRI | Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts | See SSRIs. |

| Venlafaxine extended release | Stable hypertension in a small proportion of patients | Monitor pressure, especially when increasing dose. |

| TCA | Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts | See SSRIs. |

| Anticholinergic effects | Do not administer TCAs to patients with exacerbation of narrow-angle glaucoma or clinically significant prostatic hypertrophy. | |

| Falls and fractures | See SSRIs. | |

| Significant or fatal arrhythmia | In patients with cardiac conduction disorders, have an ECG performed before starting treatment. | |

| Significant cardiotoxicity and death by overdose | Use with caution in suicidal patients. | |

| Benzodiazepines | Sedation, fatigue, ataxia, slurred speech, memory impairment, weakness | |

| Falls and fractures | See SSRIs. | |

| Increased risk of car accidents | Warn the patient about the risks associated with driving a car and operating complex devices. | |

| nine0518 Additive effect when combined with alcohol | Inform the patient of these effects, in particular the combination of sedation and respiratory depression. | |

| Potential abuse or relapse of substance abuse disorders | Use caution in patients with a history of substance abuse disorders and watch carefully, e.g. give the drug in a limited amount, monitor intake, monitor adherence to treatment, increase the frequency of meetings. nine0002 | |

| Cognitive impairment | Monitor the development of cognitive impairment, which can become a problem at high doses and in patients performing complex information processing tasks at work. Use with caution in elderly patients and those who already have cognitive impairment. |

Ensure that psychosocial interventions are carried out by professionals with the appropriate training and experience

- CBT for panic disorder typically includes psychological self-management training, self-management, counteracting anxious attitudes, dealing with fear triggers, changing anxiety-holding behaviors, and relapse prevention.

The doctor may focus on specific points, depending on the patient's symptoms and response to various CBT techniques. For most patients, dealing with fear-provoking situations is the most challenging, but often the most powerful component of CBT. nine0068

The doctor may focus on specific points, depending on the patient's symptoms and response to various CBT techniques. For most patients, dealing with fear-provoking situations is the most challenging, but often the most powerful component of CBT. nine0068 - Exposure therapy focuses almost exclusively on systematic exposure to situations that provoke fear.

- Possible benefits of group CBT include: relief from shame and stigma; the ability to plan, use sources of inspiration and support; exposure therapy for those experiencing panic symptoms in a social situation.

- COPP uses the basic principles of psychodynamic psychotherapy with an emphasis on the transformation that occurs under the influence of a therapeutic agent that promotes change, encouraging patients to reduce the emotional significance of panic symptoms in order to gain greater autonomy, relieve symptoms and improve functionality. nine0068

- Other types of psychodynamic psychotherapy may focus on broader emotional and interpersonal issues.

Provide psychosocial support for the right time frame and in the right format

- CBT usually lasts 10-15 weeks.

- Self-guided CBT is suitable for patients who do not have access to a CBT specialist.

- COPC was administered twice weekly for 12 weeks during efficacy studies. nine0068

Assess if the chosen treatment plan is working

- The effect of treatment is to reduce the main symptoms: the frequency and severity of panic attacks, the level of anticipatory anxiety, the degree of agoraphobic avoidance, the discomfort caused by panic disorder.

- In some areas, success may be achieved more quickly (e.g. the frequency of panic attacks may decrease before the degree of agoraphobic avoidance decreases). The nature of the weakening of symptoms depends on the individual characteristics of the patient; for example, for some, relief comes quickly and immediately, for someone the condition improves gradually and slowly, over several weeks.

nine0068

nine0068

If response to initial treatment is unsatisfactory, reasons should be identified first with treatment benefits.

If response to initial treatment remains unsatisfactory, add another first line agent or change treatment

- drugs or augmentation is little studied.

- If the initial treatment has yielded visible results, it is reasonable to resort to augmentation. For example, you can add another drug (e.g. a benzodiazepine to an antidepressant) or combine pharmacotherapy with psychotherapy. nine0068

- If the initial treatment does not bring visible improvement, it is better to change the treatment plan.

- When treatments with the strongest evidence base have not been successful (due to lack of effect or severe side effects), treatments with less strong evidence (e.

g. MAOIs, COPP) should be considered.

g. MAOIs, COPP) should be considered. - Once first-line, second-line, and augmentation methods have been used, it is possible to move on to methods with the weakest evidence of effectiveness. These include monotherapy or augmentation with gabapentin, second-generation antipsychotics, or other types of psychotherapy (not CBT or POPP). nine0068

If severe symptoms are preserved, despite a long course of treatment, you need to draw up a new treatment plan and consult with another professional

Clinical factors responsible for the unsatisfactory response for treatment

- Unlucky somatic disease

- Impact of comorbid medical or psychiatric illness (including depression and substance abuse)

- Non adherence to treatment

- Problems with establishing a therapeutic alliance

- Psychosocial stressors

- Problems with motivation

- Drug intolerance

After response to treatment, provide maintenance therapy to further relieve symptoms and prevent relapse

- Pharmacotherapy should be continued for a year or more.

Studies show that the therapeutic effect of antidepressants lasts as long as they are taken. Clinical experience suggests that many patients can take benzodiazepines for many years without a return of symptoms. nine0068

Studies show that the therapeutic effect of antidepressants lasts as long as they are taken. Clinical experience suggests that many patients can take benzodiazepines for many years without a return of symptoms. nine0068 - For those undergoing psychotherapy, supportive psychotherapy may be helpful in maintaining success; however, further research is required on this issue.

- The decision to discontinue pharmacotherapy should be made jointly with the patient.

- The discussion should address the potential consequences of discontinuing pharmacotherapy, including symptom relapse and withdrawal.

Several factors must be considered before discontinuing pharmacotherapy:

- Patient motivation level

- Duration of achieved remission

- Concomitant diseases

- Current and upcoming psychosocial stressors

- Psychological support

- Availability of alternative treatments

When discontinuing drugs, gradually reduce the dose (i.

.jpg)