Er for mental breakdown

Can You Go to the ER for Mental Health Help? I Psych Central

If you’re having a mental health crisis, it’s important to get help right away — a trip to the emergency room might be your best option.

When you’re in the midst of a mental health emergency, it may feel like you’re entirely alone. This can seem especially true if you’re isolated or it’s in the middle of the night.

When something like this happens, you may ask yourself if you or your loved one should endure it — or if it’s serious enough to seek immediate help.

In mental health emergencies, you can go to the emergency room (ER) for immediate help.

Visits to the ER for mental health crises are rising. At least 6% of adult ER visits are due to mental health complaints, as well as 7% of pediatric visits.

This reflects an increase in mental health conditions, in general. According to a 2021 study, this was particularly true during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

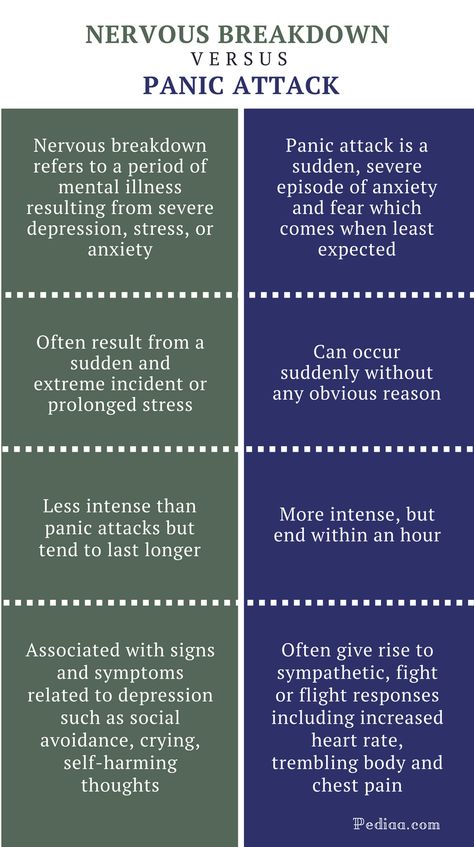

Some common mental health conditions that may be seen in the ER include:

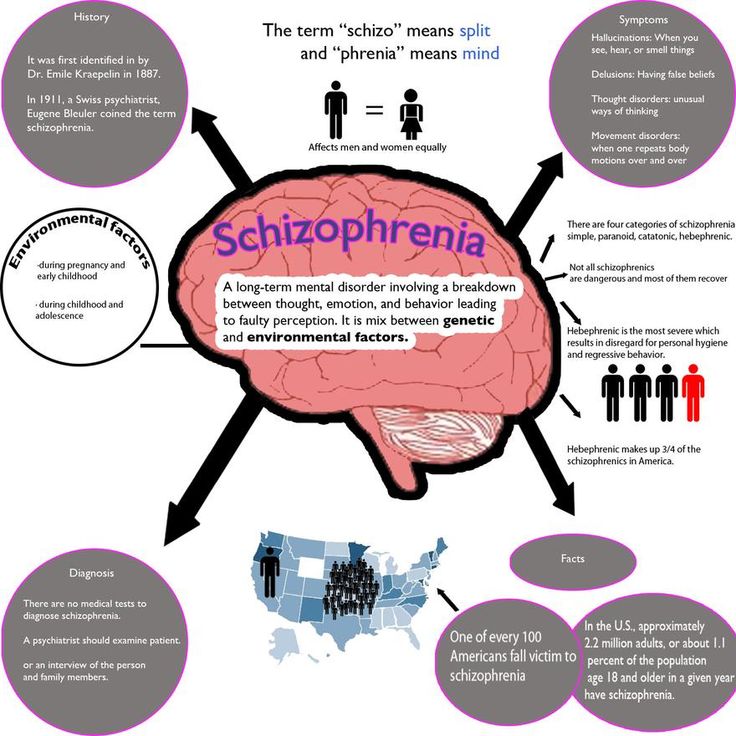

- schizophrenia

- bipolar disorder

- anxiety disorders

- panic attacks

- schizoaffective disorder

- depression

Keep in mind that this isn’t an exhaustive list. What matters most is that you should pursue care if you feel that your safety is at risk, if you’re having severe symptoms, or think you might be having an episode of psychosis.

“If you’re ever worried about safety, you should go to the ER,” says Isabelle Morley, PsyD, of Boston, Massachusetts, who specializes in helping individuals address mental health issues, as well as provides couples therapy and coaching.

“This means that if you think you or someone else might seriously hurt themselves or are having thoughts of suicide, seek immediate psychiatric help. The ER is the right place to go,” she adds.

If seeing a private doctor or going to a mental health center isn’t possible during a mental health crisis, heading to the ER may be your only option.

In addition to self-harm and thoughts of suicide, you should consider going to the ER if you’re experiencing the following:

- visual or auditory hallucinations

- delusions

- OCD symptoms that have become dangerous

- severe medication side effects

- severe insomnia

- aggression or assault

- paranoia

- confusion

- mania

Going to the ER may feel like an overwhelming experience. Emergency rooms, after all, are often loud, busy, and chaotic, sometimes with long wait times.

Emergency rooms, after all, are often loud, busy, and chaotic, sometimes with long wait times.

And yet, it may be comforting to know that crisis services are available to help anywhere, anytime — and to anyone.

What’s more, most emergency rooms will aim to make your stay as comfortable as possible. Warm blankets, food, and drinks are all often provided as a course of action is determined.

“At the ER, you will be seen by a team of nurses and doctors, likely including a psychiatrist,” Morley says. In some ERs, you might be seen by a psychologist or other psychotherapist in addition to the medical team.

They’ll ask you questions about the following:

- your current symptoms

- when your symptoms started

- your mental health history

- any relevant medical diagnoses

If you’ve gone to the ER because of thoughts of suicide, you’ll probably be assessed for risk. This will help your medical team determine the level of care you need.

For other conditions, an evaluation will probably be included to determine a “working diagnosis.” This will help in carving out a plan of action.

Morley says that you’ll probably be asked if you already have a treatment team. This way “they can get in touch with your therapist or prescriber.”

You’ll also be asked to complete paperwork and answer questions about insurance and your medical history. This might seem like a menial task when you’re going through an emergency, but it’s a necessary one. Be sure to take your time and be honest about your medical history and any medications you’re already taking.

You may also receive crisis counseling, medication, and a physical exam to rule out any medical problems.

If your ER team believes you’re a threat to yourself or others, they may keep you in the hospital. This may be followed by inpatient treatment, intensive outpatient treatment, or outpatient treatment.

If the hospital doesn’t have an inpatient unit, you might be referred to a different hospital that does have one.

If you’ve been taken to the ER involuntarily — and your medical team believes you may self-harm or harm others — you may have to stay in the hospital (or another facility) for 72 hours. Any additional time will require a court hearing.

Thomas Pederson, emergency room tech, says: “Many of our patients actually go home at the end of the day with a referral to a regular therapist they can see 2 times a week.”

“This is generally at the discretion of the caseworker for that patient, but many patients say things they don’t mean and pose no threat to others after they’ve been talked to,” he adds.

In other words, how long you stay in the ER depends completely on your situation — and the amount of care you need.

If possible, absolutely bring someone with you. A friend or family member can sit with you as you wait to be seen and assist you with paperwork. They can also help you answer questions.

At the same time, they can make arrangements that need to be done at home — from calling your employer to feeding your pets.

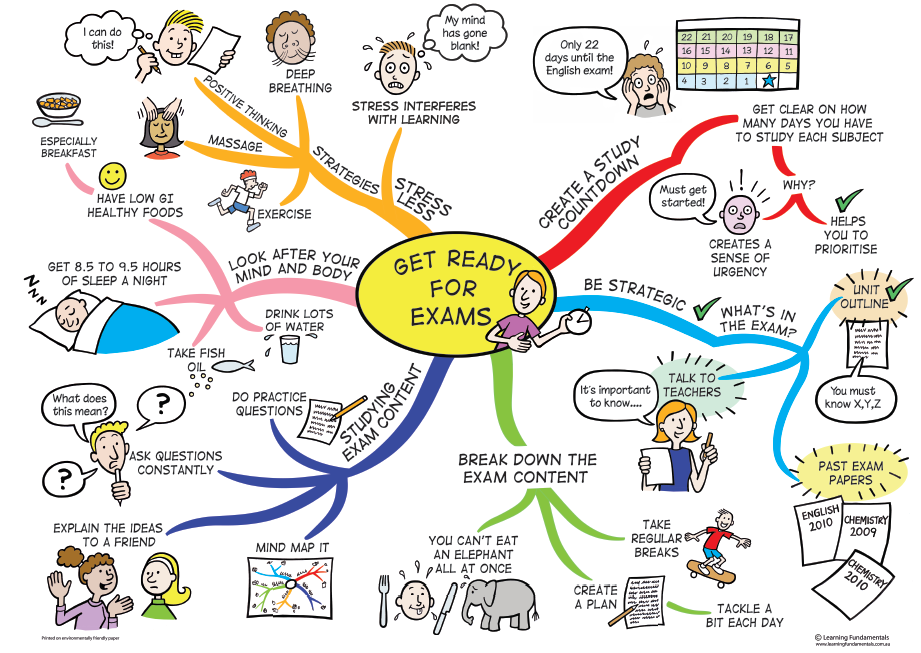

Morley is just one expert who believes a crisis plan is a good idea. These “guides” can help you and your loved ones keep an eye out for certain symptoms — and the appropriate steps to take if another mental health crisis occurs.

A crisis plan should include the following items:

- the phone number of your therapist or psychiatrist

- phone numbers of friends and family members who are helpful in crises

- your diagnosis and medications

- things that have helped in the past

As mentioned, going to the ER during a mental health crisis — when you’re already scared — can feel intimidating.

If the emergency room isn’t an option for you, there are other ways to seek help during a mental health emergency:

- Crisis lines. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, for example, is available to help 24/7. They can be reached at 800-273-8255.

- Mobile crisis teams. These teams can provide prescreening evaluations.

They can also assist with arrangements for inpatient care and community programs.

They can also assist with arrangements for inpatient care and community programs. - Walk-in services. These clinics and urgent care centers offer crisis counseling in a less overwhelming setting than a hospital. However, they may suggest hospitalization when necessary.

A mental health emergency may feel terrifying, but professionals are ready — and want to — help.

Going to the ER for a mental health crisis can depend on your symptoms. But, above all, it comes down to how you feel and if your safety is at risk.

If you or a loved one are experiencing any of the warning signs mentioned here, please reach out for support, whether that’s the ER, urgent care, or a crisis hotline. Be honest about how you’re feeling and where you’ve been. Doing so may be your first step toward treatment and recovery.

Can You Go to the ER for Mental Health Help? I Psych Central

If you’re having a mental health crisis, it’s important to get help right away — a trip to the emergency room might be your best option.

When you’re in the midst of a mental health emergency, it may feel like you’re entirely alone. This can seem especially true if you’re isolated or it’s in the middle of the night.

When something like this happens, you may ask yourself if you or your loved one should endure it — or if it’s serious enough to seek immediate help.

In mental health emergencies, you can go to the emergency room (ER) for immediate help.

Visits to the ER for mental health crises are rising. At least 6% of adult ER visits are due to mental health complaints, as well as 7% of pediatric visits.

This reflects an increase in mental health conditions, in general. According to a 2021 study, this was particularly true during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some common mental health conditions that may be seen in the ER include:

- schizophrenia

- bipolar disorder

- anxiety disorders

- panic attacks

- schizoaffective disorder

- depression

Keep in mind that this isn’t an exhaustive list. What matters most is that you should pursue care if you feel that your safety is at risk, if you’re having severe symptoms, or think you might be having an episode of psychosis.

What matters most is that you should pursue care if you feel that your safety is at risk, if you’re having severe symptoms, or think you might be having an episode of psychosis.

“If you’re ever worried about safety, you should go to the ER,” says Isabelle Morley, PsyD, of Boston, Massachusetts, who specializes in helping individuals address mental health issues, as well as provides couples therapy and coaching.

“This means that if you think you or someone else might seriously hurt themselves or are having thoughts of suicide, seek immediate psychiatric help. The ER is the right place to go,” she adds.

If seeing a private doctor or going to a mental health center isn’t possible during a mental health crisis, heading to the ER may be your only option.

In addition to self-harm and thoughts of suicide, you should consider going to the ER if you’re experiencing the following:

- visual or auditory hallucinations

- delusions

- OCD symptoms that have become dangerous

- severe medication side effects

- severe insomnia

- aggression or assault

- paranoia

- confusion

- mania

Going to the ER may feel like an overwhelming experience. Emergency rooms, after all, are often loud, busy, and chaotic, sometimes with long wait times.

Emergency rooms, after all, are often loud, busy, and chaotic, sometimes with long wait times.

And yet, it may be comforting to know that crisis services are available to help anywhere, anytime — and to anyone.

What’s more, most emergency rooms will aim to make your stay as comfortable as possible. Warm blankets, food, and drinks are all often provided as a course of action is determined.

“At the ER, you will be seen by a team of nurses and doctors, likely including a psychiatrist,” Morley says. In some ERs, you might be seen by a psychologist or other psychotherapist in addition to the medical team.

They’ll ask you questions about the following:

- your current symptoms

- when your symptoms started

- your mental health history

- any relevant medical diagnoses

If you’ve gone to the ER because of thoughts of suicide, you’ll probably be assessed for risk. This will help your medical team determine the level of care you need.

For other conditions, an evaluation will probably be included to determine a “working diagnosis.” This will help in carving out a plan of action.

Morley says that you’ll probably be asked if you already have a treatment team. This way “they can get in touch with your therapist or prescriber.”

You’ll also be asked to complete paperwork and answer questions about insurance and your medical history. This might seem like a menial task when you’re going through an emergency, but it’s a necessary one. Be sure to take your time and be honest about your medical history and any medications you’re already taking.

You may also receive crisis counseling, medication, and a physical exam to rule out any medical problems.

If your ER team believes you’re a threat to yourself or others, they may keep you in the hospital. This may be followed by inpatient treatment, intensive outpatient treatment, or outpatient treatment.

If the hospital doesn’t have an inpatient unit, you might be referred to a different hospital that does have one.

If you’ve been taken to the ER involuntarily — and your medical team believes you may self-harm or harm others — you may have to stay in the hospital (or another facility) for 72 hours. Any additional time will require a court hearing.

Thomas Pederson, emergency room tech, says: “Many of our patients actually go home at the end of the day with a referral to a regular therapist they can see 2 times a week.”

“This is generally at the discretion of the caseworker for that patient, but many patients say things they don’t mean and pose no threat to others after they’ve been talked to,” he adds.

In other words, how long you stay in the ER depends completely on your situation — and the amount of care you need.

If possible, absolutely bring someone with you. A friend or family member can sit with you as you wait to be seen and assist you with paperwork. They can also help you answer questions.

At the same time, they can make arrangements that need to be done at home — from calling your employer to feeding your pets.

Morley is just one expert who believes a crisis plan is a good idea. These “guides” can help you and your loved ones keep an eye out for certain symptoms — and the appropriate steps to take if another mental health crisis occurs.

A crisis plan should include the following items:

- the phone number of your therapist or psychiatrist

- phone numbers of friends and family members who are helpful in crises

- your diagnosis and medications

- things that have helped in the past

As mentioned, going to the ER during a mental health crisis — when you’re already scared — can feel intimidating.

If the emergency room isn’t an option for you, there are other ways to seek help during a mental health emergency:

- Crisis lines. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, for example, is available to help 24/7. They can be reached at 800-273-8255.

- Mobile crisis teams. These teams can provide prescreening evaluations.

They can also assist with arrangements for inpatient care and community programs.

They can also assist with arrangements for inpatient care and community programs. - Walk-in services. These clinics and urgent care centers offer crisis counseling in a less overwhelming setting than a hospital. However, they may suggest hospitalization when necessary.

A mental health emergency may feel terrifying, but professionals are ready — and want to — help.

Going to the ER for a mental health crisis can depend on your symptoms. But, above all, it comes down to how you feel and if your safety is at risk.

If you or a loved one are experiencing any of the warning signs mentioned here, please reach out for support, whether that’s the ER, urgent care, or a crisis hotline. Be honest about how you’re feeling and where you’ve been. Doing so may be your first step toward treatment and recovery.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia- Healthcare issues »

- A

- B

- B

- G

- D

- E

- and

- 9000 About

- P

- P

- With

- T

- in

- F

- x

- 9 h

- K.

- S

- B

- E

- S

- I

- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- Newsletter

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find country »

- A

- B

- C

- g

- D

- E

- and

- th

- K

- L

- 9000 N

- 9000

- in

- Ф

- x

- C hours

- Sh

- Sh.

- K

- E 9000 WHO in countries »

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A nine0005

- Developments

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Highlights " nine0005

- About WHO »

- General director

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Newsletters/

- Read more/ nine0004 Schizophrenia

Key Facts

- Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder that affects approximately 24 million people, or 1 in 300 people worldwide.

- Schizophrenia causes psychosis, is associated with severe disability, and can negatively affect all areas of life, including personal, family, social, academic and work life.

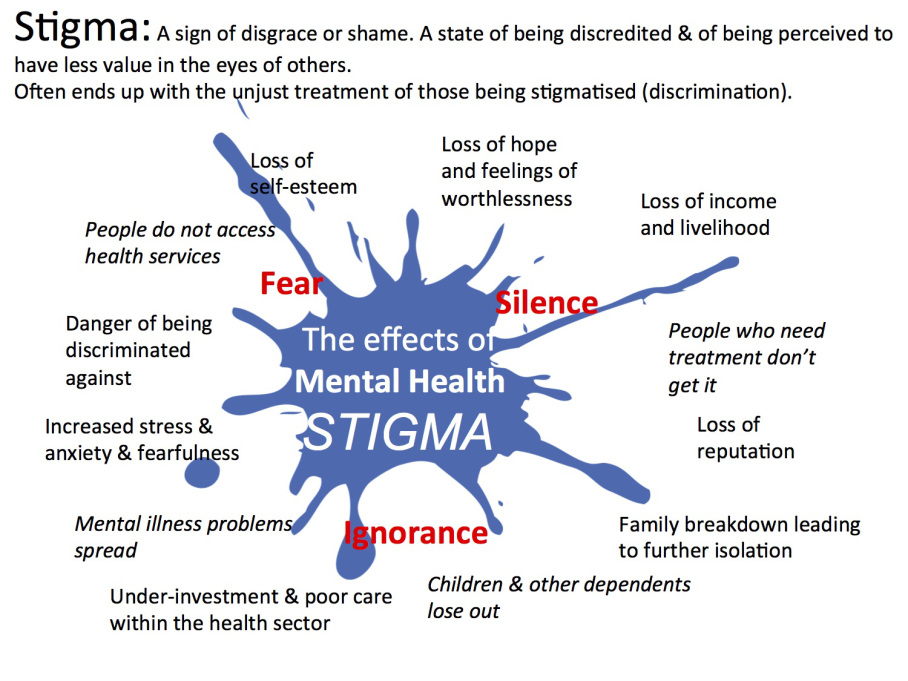

- People with schizophrenia are often subject to stigma, discrimination and human rights violations. nine0286

- Worldwide, more than two thirds of people with psychosis do not receive specialized mental health care.

- There are a number of effective care options for patients with schizophrenia that can lead to a complete recovery of at least one in three patients.

Symptoms

Schizophrenia is characterized by significant disturbances in perception of reality and behavioral changes such as:

- persistent delusions: the patient has a persistent belief in the truth of certain things, despite evidence to the contrary;

- persistent hallucinations: the patient hears, sees, touches non-existent things and smells non-existent smells;

- feeling of external influence, control or passivity: the presence in the patient of the feeling that his feelings, impulses, actions or thoughts are dictated from outside, put in or disappear from consciousness at the will of others, or that his thoughts are broadcast to others; nine0005

- disorganized thinking, often expressed in incoherent or pointless speech;

- Significant disorganization of behavior, which is manifested, for example, by the patient performing actions that may seem strange or meaningless, or in an unpredictable or inappropriate emotional reaction that does not give the patient the opportunity to organization of their behavior;

- "negative symptoms" such as extreme poverty of speech, smoothness of emotional reactions, inability to feel interest or pleasure, social autism; and/or

- Extreme agitation or, on the contrary, slowness of movements, freezing in unusual postures.

People with schizophrenia often also experience persistent cognitive or thinking problems that affect memory, attention, or problem-solving skills.

At least one third of patients with schizophrenia experience complete remission of symptoms (1). In some, periods of remission and exacerbation of symptoms follow each other throughout life, in others there is a gradual increase in symptoms. nine0322

Scope and impact

Schizophrenia affects approximately 24 million people, or 1 in 300 people (0.32%) worldwide. Among adults, the rate is 1 in 222 (0.45%) (2). Schizophrenia is less common than many other mental disorders. Onset is most common in late adolescence and between the ages of 20 and 30; while women tend to have a later onset of the disease. nine0322

Schizophrenia is often accompanied by significant stress and difficulties in personal relationships, family life, social contacts, studies, work or other important areas of life.

Individuals with schizophrenia are 2-3 times more likely to die early than the population average (2). It is often associated with physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, and infectious disease.

It is often associated with physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, and infectious disease.

Patients with schizophrenia often become the object of human rights violations both within the walls of psychiatric institutions and in everyday life. Significant stigmatization of people with this disease is a widespread phenomenon that leads to their social isolation and has a negative impact on their relationships with others, including family and friends. This creates grounds for discrimination, which in turn limits access to health services in general, education, housing and employment. nine0322

Humanitarian emergencies and health crises can cause intense stress and fear, disrupt social support mechanisms, lead to isolation and disruption of health services and supply of medicines. All these shocks can have a negative impact on the lives of people with schizophrenia, in particular by exacerbating existing symptoms of the disease. People with schizophrenia are more vulnerable during emergencies to various human rights violations and, in particular, face neglect, abandonment, homelessness, abuse and social exclusion. nine0322

nine0322

Causes of schizophrenia

Science has not established any one cause of the disease. It is believed that schizophrenia may be the result of the interaction of a number of genetic and environmental factors. Psychosocial factors may also influence the onset and course of schizophrenia. In particular, heavy marijuana abuse is associated with an increased risk of this mental disorder.

Assistance services

At present, the vast majority of people with schizophrenia do not receive mental health care worldwide. Approximately 50% of patients in psychiatric hospitals are diagnosed with schizophrenia (4). Only 31.3% of people with psychosis get specialized mental health care (5). Much of the resources allocated to mental health services are inefficiently spent on the care of patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals.

Available scientific evidence clearly indicates that hospitalization in psychiatric hospitals is not an effective treatment for mental disorders and is regularly associated with the violation of the basic rights of patients with schizophrenia. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure the expansion and acceleration of work on the transfer of functions in the field of mental health care from psychiatric institutions to the level of local communities. Such work should begin with the organization of the provision a wide range of quality community-based mental health services. Options for community-based mental health care include integrating this type of care into primary health care and hospital care. general care, setting up community mental health centres, outpatient care centres, social housing with nursing care and social home care services. Involvement in the care process is important the patient with schizophrenia, his family members and members of local communities. nine0322

Therefore, it is necessary to ensure the expansion and acceleration of work on the transfer of functions in the field of mental health care from psychiatric institutions to the level of local communities. Such work should begin with the organization of the provision a wide range of quality community-based mental health services. Options for community-based mental health care include integrating this type of care into primary health care and hospital care. general care, setting up community mental health centres, outpatient care centres, social housing with nursing care and social home care services. Involvement in the care process is important the patient with schizophrenia, his family members and members of local communities. nine0322

Schizophrenia management and care

There are a number of effective approaches to treating people with schizophrenia, including medication, psychoeducation, family therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and psychosocial rehabilitation (eg, life skills education). The most important interventions for helping people with schizophrenia are assisted living, special housing and employment assistance. It is extremely important for people with schizophrenia and their families and/or caregivers to a recovery-centered approach that empowers people to participate in decisions about their care. nine0322

The most important interventions for helping people with schizophrenia are assisted living, special housing and employment assistance. It is extremely important for people with schizophrenia and their families and/or caregivers to a recovery-centered approach that empowers people to participate in decisions about their care. nine0322

WHO action

steps are in place to ensure that appropriate services are provided to people with mental disorders, including schizophrenia. One of the key recommendations The action plan is to transfer the function of providing assistance from institutions to local communities. WHO Special Mental Health Initiative aims to further progress towards the goals of the Comprehensive Plan mental health action 2013–2030 by ensuring that 100 million more people have access to quality and affordable mental health care. nine0322

The WHO Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP) is working to develop evidence-based technical guidelines, tools and training packages to scale up services in countries, especially in low-resource settings. The program focuses on a priority list of mental health disorders, including psychosis, and aims to strengthen the capacity of non-specialized health workers in as part of an integrated approach to mental health care at all levels of care. To date, the mhGAP Program has been implemented in more than 100 WHO Member States. nine0322

The program focuses on a priority list of mental health disorders, including psychosis, and aims to strengthen the capacity of non-specialized health workers in as part of an integrated approach to mental health care at all levels of care. To date, the mhGAP Program has been implemented in more than 100 WHO Member States. nine0322

The WHO QualityRights project aims to improve the quality of care and better protect human rights in mental health and social care settings and to expand opportunities of various organizations and associations to defend the rights of persons with mental disorders and psychosocial disabilities.

The WHO guidelines on community mental health services and human rights-based approaches provide information for all stakeholders who intend to develop or transform mental health systems and services. health in accordance with international human rights standards, including the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. nine0322

Bibliography

(1) Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, Laska E, Siegel C, Wanderling J. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:506-17.

Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:506-17.

(2) Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/27a7644e8ad28e739382d31e77589dd7 (accessed 25 September 2021)

(3) LaursenTM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Excess early mortality in schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology , 2014;10, 425-438.

(4) WHO. Mental health systems in selected low- and middle-income countries: a WHO-AIMS cross-national analysis. WHO: Geneva, 2009

(5) Jaeschke K et al. Global estimates of service coverage for severe mental disorders: findings from the WHO Mental Health Atlas 2017 Glob Ment Health 2021;8:e27.

Autism

Autism- Healthcare issues »

- A

- B

- B

- G

- D

- E

- and

- 9000 O

- M

- R

- S

- T

- Y

- F

- X

- C

- W

- B

- S

- B

- E

- S

- I

4 SC

- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- Newsletter

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find a country »

- A

- B

- in

- g

- D

- E

- С

- and

- L

- m

- N

- P

- Since

- T

- in

- x

- hours

- Sh

- 9000 WHO in countries » nine0003

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A nine0005

- Developments

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Highlights " nine0005

- About WHO »

- General director

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Newsletters/

- Read more/ nine0004 Autism

Key Facts

- Autism, also called autism spectrum disorder, is a diverse group of pathological conditions caused by the development of the brain.

- Signs of autism can be detected in early childhood, but often it is not diagnosed until later in life.

- Approximately 1 in 100 children have autism.

- The abilities and needs of people with autism can vary and change over time. Some people with autism are able to lead independent and productive lives, while others become severely disabled and require lifelong care and support.

- Evidence-based psychosocial interventions can improve communication skills and social behavior that positively impact the well-being and quality of life of people with autism and their caregivers. nine0286

- Care for people with autism must be accompanied by local and community action to make physical and social environments and relationships more accessible, inclusive and supportive.

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) are a group of different conditions. All of them are characterized by certain difficulties with social interaction and communication. Other features include atypical patterns of action and behaviors, such as difficulty moving from one activity to another, focus on details, and unusual responses to external stimuli. nine0322

All of them are characterized by certain difficulties with social interaction and communication. Other features include atypical patterns of action and behaviors, such as difficulty moving from one activity to another, focus on details, and unusual responses to external stimuli. nine0322

The abilities and needs of people with autism can vary and change over time. Some people with autism are able to live independent and productive lives, while others become severely disabled and require lifelong care and support. Autism often negatively affects educational or employment opportunities. In addition, for family members of people with autism, care and support responsibilities can often be a source of significant stress. Community attitudes and the level of support from local and national governments are important determinants of the quality of life of people with autism. nine0322

Signs of autism can be identified in early childhood, but the condition is often diagnosed at much later stages.

People with autism often have comorbid conditions and illnesses, including epilepsy, depression, anxiety, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, as well as behavioral problems such as sleep disturbances or self-harm. The level of intellectual abilities of people with autism varies in a wide range from severe cognitive impairment to a high level of intelligence. nine0322

Epidemiology

Worldwide, autism is estimated to affect about 1 in 100 children (1). At the same time, we are talking about an average indicator, and the prevalence rates of autism recorded according to different studies vary widely. Nevertheless, according to some reputable controlled studies, the real numbers are much higher. The prevalence of autism in many low- and middle-income countries is unknown.

Causes

Available scientific evidence indicates many factors that may increase the likelihood of children developing autism, including environmental and genetic factors.

Available epidemiological data do not establish a causal relationship between autism and measles, mumps and rubella vaccination. Past studies suggesting such a causal relationship have been many methodological problems were found (2), (3). nine0322

Similarly, there is no evidence that any childhood vaccine can increase the risk of developing autism. Evidence reviews on a potential association between the preservative thiomersal and aluminum adjuvants contained in inactivated vaccines and the risk of developing autism strongly suggest that vaccines do not lead to an increase in this risk.

Needs Assessment and Care Management

A range of interventions, from early childhood and throughout life, can contribute to the optimal development, well-being and quality of life of people with autism. Timely evidence-based psychosocial interventions at an early age can improve the ability of children with autism to communicate and interact effectively with others. It is recommended to monitor the development of children as part of the planned provision of medical care to mothers and children. nine0322

It is recommended to monitor the development of children as part of the planned provision of medical care to mothers and children. nine0322

It is important that immediately after diagnosis, children, adolescents and adults diagnosed with autism and their caregivers have access to relevant information, referrals and practical support tailored to their individual needs. constantly changing needs and preferences.

The health care needs of people with autism are complex and therefore they require comprehensive services, including health promotion, care and rehabilitation services. Therefore, it is important to ensure cooperation with other sectors, in particular with the education system, employment and the social sector. nine0322

Interventions to help people with autism and other developmental disabilities should be planned and implemented with the participation of people with these conditions themselves. Caring for people with autism should be accompanied by local action. and at the level of society as a whole, in order to make the physical and social environment and relationships more accessible, inclusive and supportive.

and at the level of society as a whole, in order to make the physical and social environment and relationships more accessible, inclusive and supportive.

Human rights

All people, including those with autism, have the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. nine0322

Yet people with autism often face stigma and discrimination: their health care and education rights are unfairly denied, and their opportunities to participate in society are limited.

People with autism may experience the same health problems as the rest of the population. In addition, they may have special health care needs related to autism and other related conditions. They can be are more vulnerable to chronic noncommunicable diseases associated with behavioral risk factors such as physical inactivity and poor diet, and are at greater risk of violence, injury and abuse. nine0322

People with autism, like the rest of the population, need affordable health services to meet general health needs, including health promotion and prevention services, as well as acute and chronic care. However less than in the general population, the level of satisfaction of the medical needs of people with autism is at a lower level. These people are also more vulnerable in humanitarian emergencies. One of the common barriers is the insufficient level of knowledge and understanding of the specifics of autism by medical professionals. nine0322

However less than in the general population, the level of satisfaction of the medical needs of people with autism is at a lower level. These people are also more vulnerable in humanitarian emergencies. One of the common barriers is the insufficient level of knowledge and understanding of the specifics of autism by medical professionals. nine0322

WHO Resolution on Autism Spectrum Disorders

In May 2014, the Sixty-seventh World Health Assembly adopted a resolution on "Comprehensive and concerted efforts for the management of autism spectrum disorders", supported by over 60 countries.

The resolution calls on WHO to work with Member States and partner agencies to strengthen national capacity to address ASD and other developmental disabilities. nine0322

WHO activities

WHO and partners recognize the need to strengthen countries' capacity to promote the optimal health and well-being of all people with autism.

The main activities of WHO in this regard are:

- promoting the adoption of targeted measures by national governments to improve the quality of life of people with autism;

- develop recommendations for policies and action plans to address autism in the broader context of physical, mental, brain health and care for people with disabilities; nine0005

- help to empower healthcare professionals to provide appropriate and effective care for people with autism and achieve optimal health and well-being; and

- promote and support an inclusive and supportive environment for people with autism and other developmental disabilities.

WHO comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2030 and World Health Assembly Resolution WHA73.10 "Global action against epilepsy and other neurological disorders" contain calling on countries to address significant gaps in the early detection, care, treatment and rehabilitation of people with mental and neurodevelopmental disorders, including and autism. The resolution also calls on countries to take action to meet the social, economic, educational and other needs of people living with mental and neurological disorders and their families, and to develop surveillance and related research activities. nine0322

References

(1) Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Zeidan J et al. Autism Research 2022 March.

(2) Wakefield's affair: 12 years of uncertainty whereas no link between autism and MMR vaccine has been proven. Maisonneuve H, Floret D. Presse Med. 2012 Sep; French https://pubmed.