Emergency psych evaluation

What will happen if I go to the ER for emergency mental health treatment during COVID?

If you’re having a mental health crisis and need immediate support, you may decide to go to the emergency room (ER). Making the decision to seek emergency help can be overwhelming, and it may feel even more stressful during the COVID-19 pandemic. While there may be a few extra steps you have to take due to new regulations, knowing what to expect can ease some of your concerns.

Early on in the pandemic, many emergency departments saw a sharp decrease in visits, likely due to fear of COVID’s high contagiousness[i]. It’s an understandable worry, but hospitals across the country are taking extreme measures to prevent the spread of COVID and ensure everyone’s safety. These new practices are important, but they also mean that your experience will probably be different from any ER visits you’ve had in the past. People who have tested positive for COVID-19 or have symptoms will probably be in an isolated unit, so you won’t share any common spaces with them.

Most hospitals are requiring everyone to wear a mask, and some are even requesting that people put on a clean hospital mask upon entering the building. Many have rearranged their waiting rooms to allow for proper distancing between patients and boosted their cleaning routines.

Aside from increased cleaning and masks, here’s what you can expect when visiting the ER for a mental health concern during this time:

- Most hospitals are restricting visitors to reduce the risk of spread. It will depend on the hospital you visit and their regulations, but you should be prepared to go into the ER alone, even if you arrive with a friend or family member. If you want their support, you can video call them once you’re in the hospital.

- Emergency rooms are notoriously busy, so you might be waiting for a few hours. And depending on the medical staff’s assessment, you could be in the hospital for a few days. Wear comfortable clothes and bring your phone, and a book or tablet (and charger) to help you pass the time.

- Due to COVID precautions, you will likely get a brief screen for COVID as soon as you walk into the building or even before – some places have stationed health care workers outside to conduct these evaluations. Everyone is screened this way, even if they come to the hospital for something other than COVID. They will ask if you’ve had any COVID symptoms and take your temperature. People with COVID symptoms or a fever will enter a different part of the hospital than non-COVID patients.

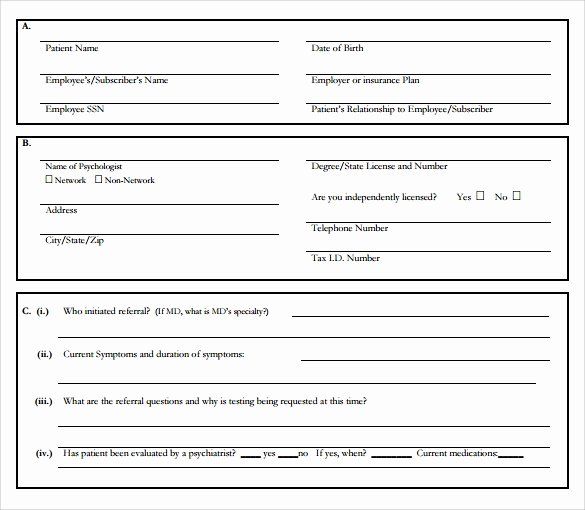

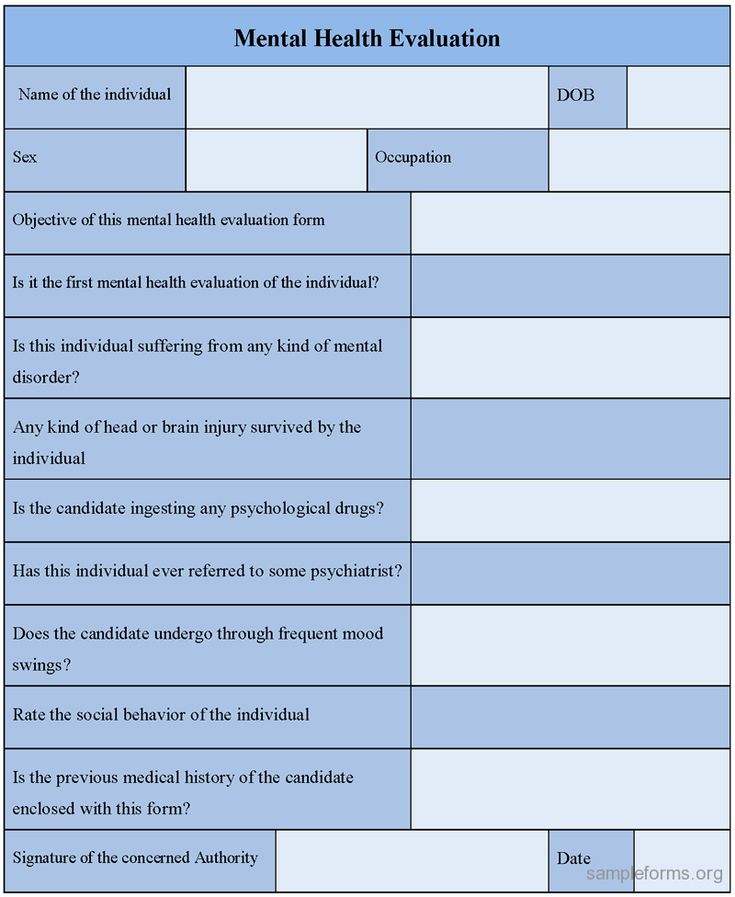

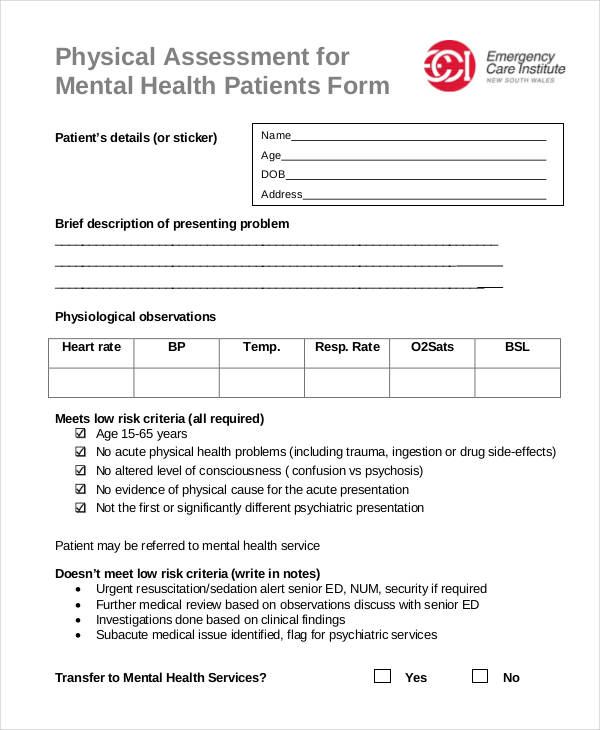

- At the registration desk, you will fill out some paperwork and answer questions about insurance, your medical history, and other background information.

- Shortly after checking in, medical staff will conduct a brief assessment to determine how urgent your situation is. They should be able to give you an estimate of how long you’ll be waiting.

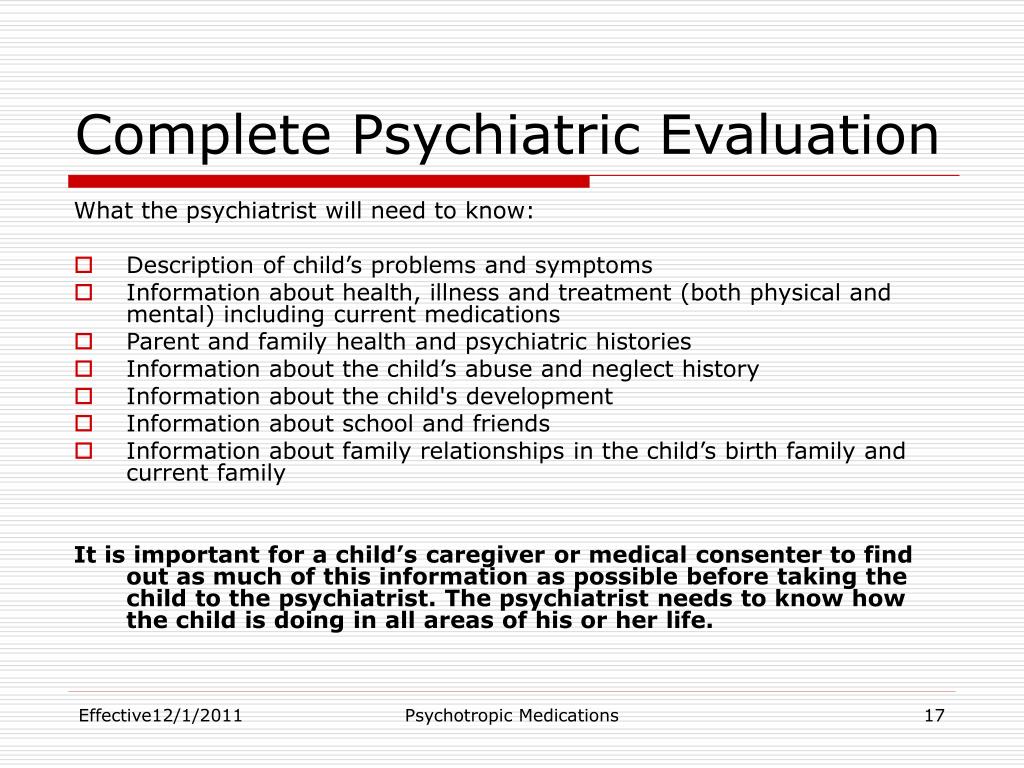

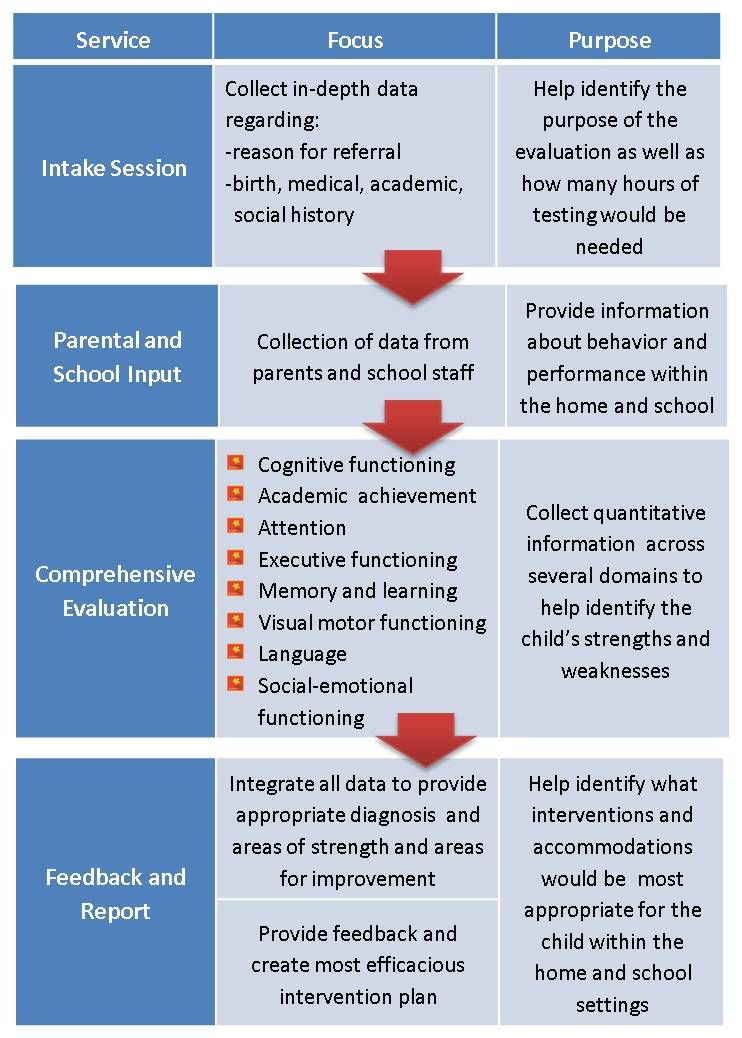

- The main event of your ER visit will likely be a psychiatric evaluation. Your team of mental health professionals will determine a working diagnosis and plan of action for treatment.

- Depending on your evaluation, you may be given medication, provided crisis counseling, or receive a referral for treatment after leaving the hospital. If your doctors are concerned for your safety, they may decide to admit you to the hospital for a few days or transfer you to a different hospital that specializes in treating people with mental health concerns. In those cases, they may administer a rapid COVID test before relocating you. A healthcare professional will swab the back of your nose or throat and have results in under 30 minutes.

If you think you might need to go to the ER for mental health support in the coming months, it may help to have a plan in place before you reach crisis. You can use MHA’s Think Ahead worksheet to help you prepare.

[i] Jeffery, M.M., D’Onofrio, G., Paek, H., et al. (2020). Trends in emergency department visits and hospital admissions in health care systems in 5 states in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Internal Medicine. Published online August 03, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3288

JAMA Internal Medicine. Published online August 03, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3288

Treating Mental Health Patients in the ER

- Copy Link

- More

If you or a loved one is in distress, confused, or a risk to themselves or others, it’s not always clear what to do or where to go for help. The person in crisis may not be in physical pain, but sometimes the lack thereof can make the event more frightening. In many instances, the emergency room is where patients are brought for a mental health crisis — in fact, psychiatric admissions are at an all-time high.

The person in crisis may not be in physical pain, but sometimes the lack thereof can make the event more frightening. In many instances, the emergency room is where patients are brought for a mental health crisis — in fact, psychiatric admissions are at an all-time high.

Can you go to the ER for mental health treatment?

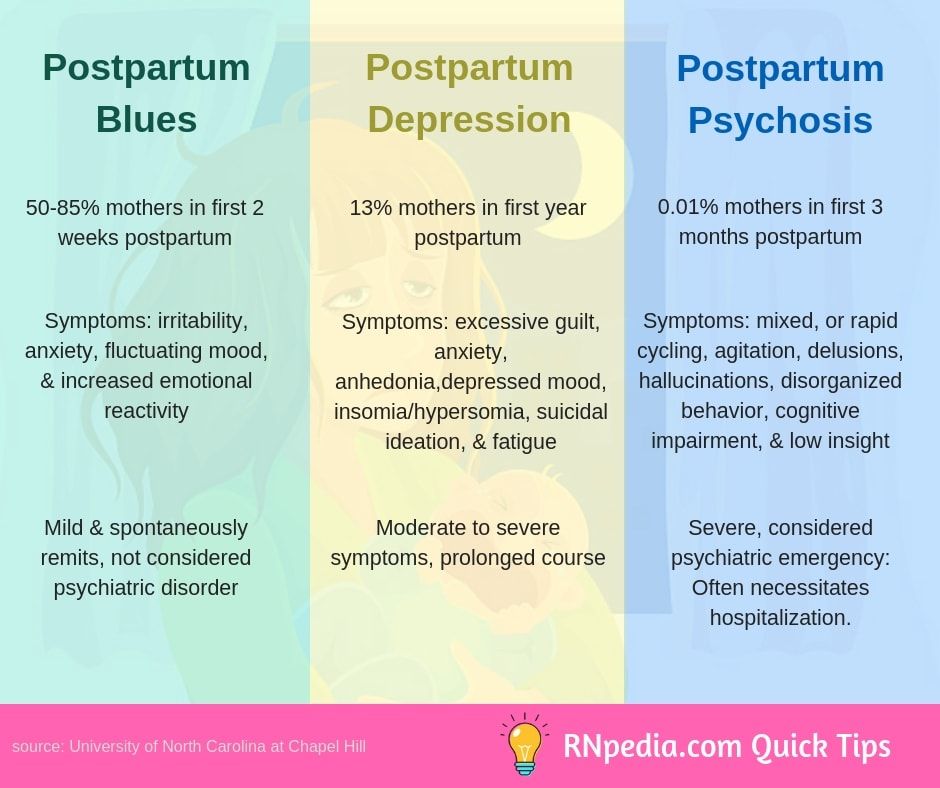

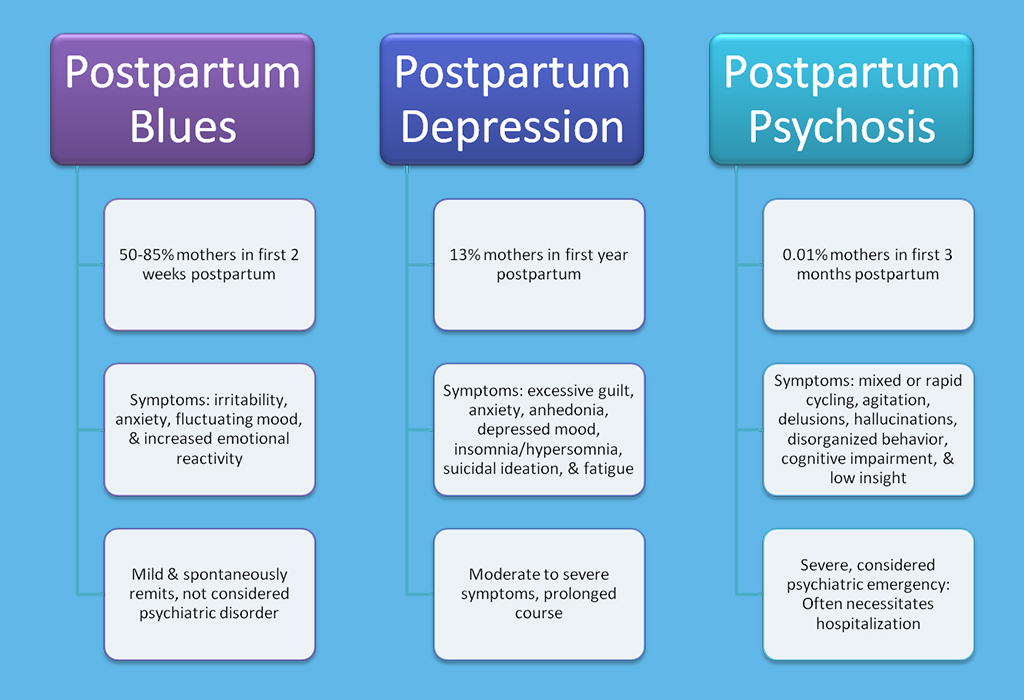

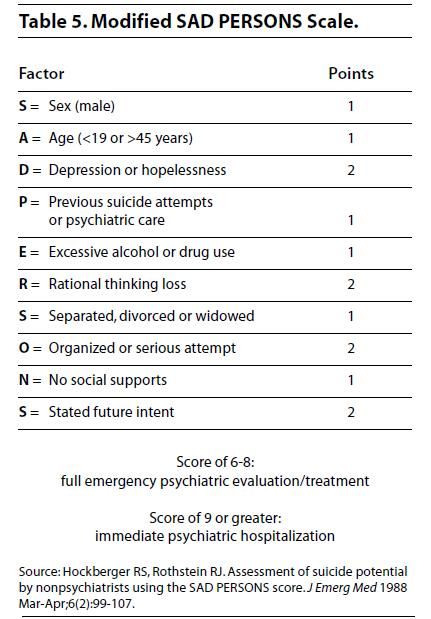

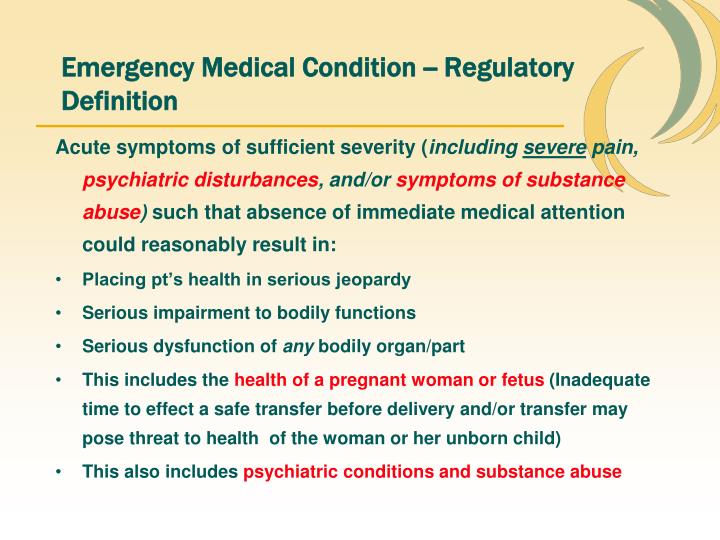

The general rule of thumb for taking a trip to the emergency room is to go when you are facing life- or limb-threatening situations. In the case of mental health, situations of suicidal ideation, homicidal thoughts, self-harm, signs of psychosis, confusion, uncontrolled mania, and hallucinations or delusions also warrant a trip to the ER.

More patients are increasingly visiting the emergency room for mental health needs.

Did you know that 6% of all adult ED visits and 7% of pediatric ED visits are for mental health issues?

While there are numerous reasons to go to the ER for mental health treatment, there are certain limitations of mental health-specific care in these settings. First, emergency rooms can be overwhelming and overstimulating. With bustling activity, bright lights, and lots of noise, the ER can be a chaotic environment that’s not ideal for mental health patients. Additionally, there are often long wait times and hold times, and there may not be instant access to a psychiatrist available.

First, emergency rooms can be overwhelming and overstimulating. With bustling activity, bright lights, and lots of noise, the ER can be a chaotic environment that’s not ideal for mental health patients. Additionally, there are often long wait times and hold times, and there may not be instant access to a psychiatrist available.

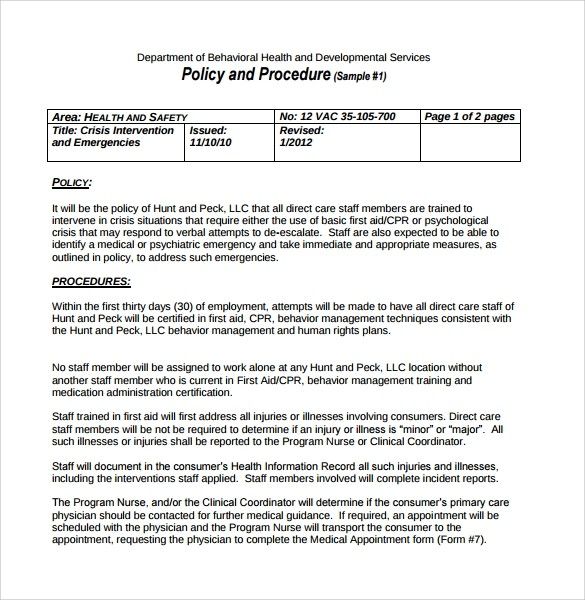

Most importantly, an ER visit for mental health could pose potential safety risks to the patient, staff, and other patients, depending on the cause of the emergency visit. There are many items in the emergency department that can pose self-harm or hanging risk, such as call cords and lanyards, among others. Unlike in-patient facilities that are designed specifically for mental health patients and those at high risk of self-harm or elopement, the ED may not be armed with the same level of safety precautions.

What to expect in an emergency room mental health assessment

If a patient is heading to the ED for a mental health emergency, the process may look a lot like the following:

- Check in and fill out paperwork.

- Be prepared for Covid-19 precautions, including mask-wearing requirements and visitor restrictions.

- Expect a brief initial assessment on the acute condition and level of urgency, with an estimate on how long of a wait is to be expected.

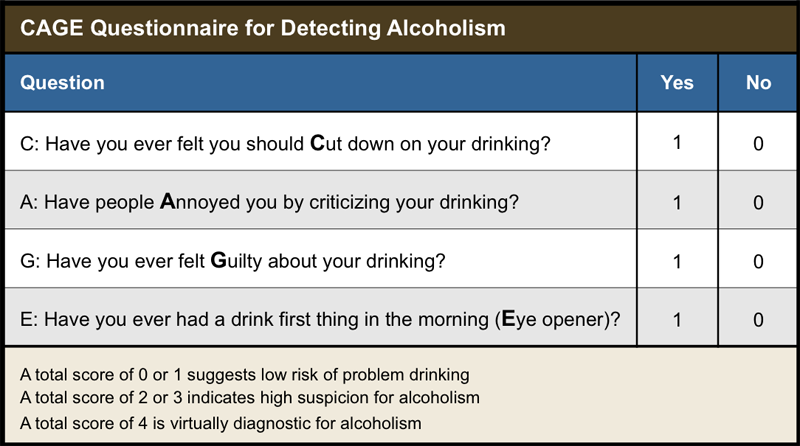

- There may be a drug screen or toxicology report, as acute intoxication is the primary reason for increased agitation and violence, according to The Psychiatric Times.

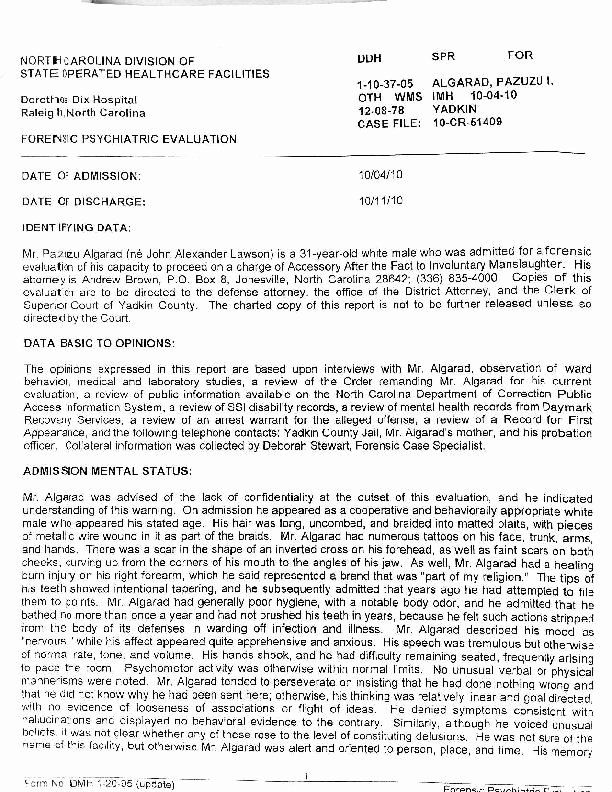

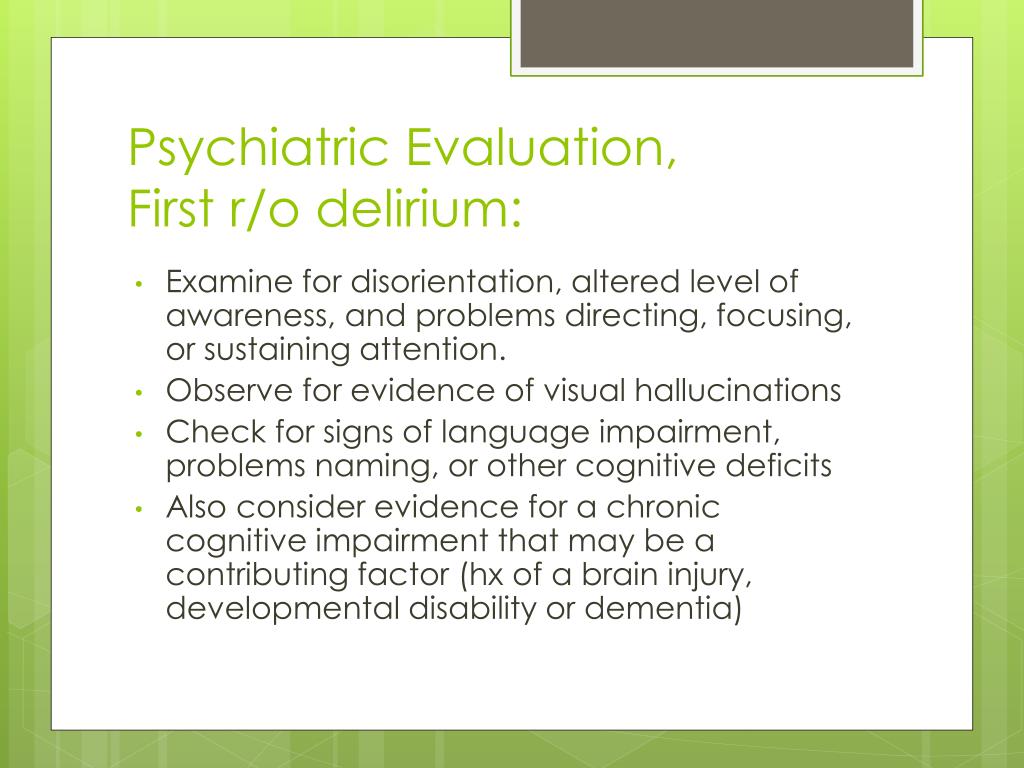

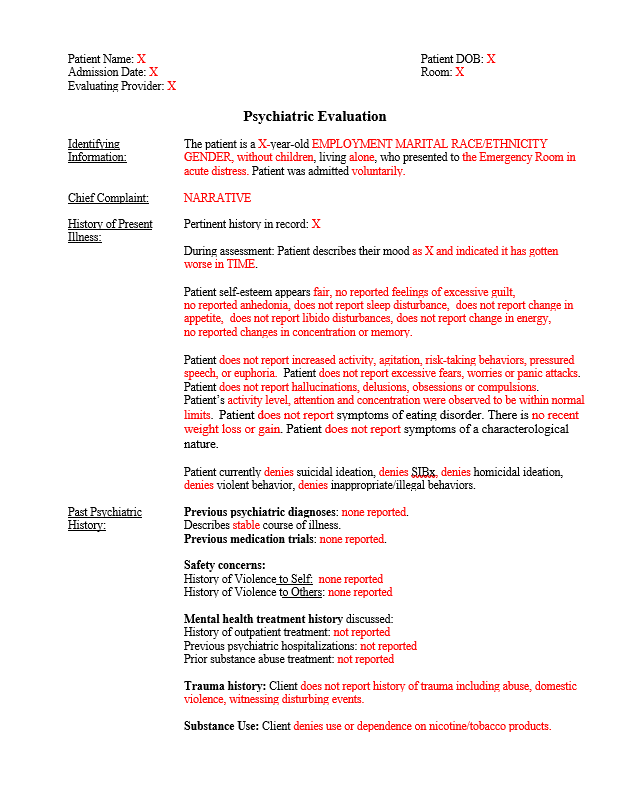

- The psychiatric evaluation is the primary part of a mental health ER visit. This mental health assessment will likely cover a face-to-face interview, first assessing why the patient is there and the medical issues of immediate concern.

- Collateral contact will likely be made with family members and friends, and other professionals like ED staff, outpatient therapists or care coordinators will be consulted.

- After the evaluation is complete, medical staff will determine an appropriate treatment plan.

Treatment could include medication, crisis counseling, a referral for inpatient treatment, hospital admission, or another recommendation.

Treatment could include medication, crisis counseling, a referral for inpatient treatment, hospital admission, or another recommendation.

Why are mental health visits to the ER increasing?

Over the last several years, mental health ER visits have steadily increased. While the pandemic has accelerated that trend, there are several factors that have led to more ER visits for mental health issues, such as the following:

- Patients not receiving proactive treatment due to lack of insurance

- Difficulty to find behavioral healthcare in-network

- Psychiatrist shortage

- More people seeking treatment since awareness of mental health problems has increased

- Lack of inpatient beds

What to do when you or a loved one is having a mental health emergency

If you or a loved one is having a mental health emergency, the first thing to do is to assess the severity of the crisis to determine if the ER is the right place to go. If the emergency is life-threatening, and the patient is experiencing psychosis or is a danger to themself or others, the ER is likely the best place to go.

If the emergency is life-threatening, and the patient is experiencing psychosis or is a danger to themself or others, the ER is likely the best place to go.

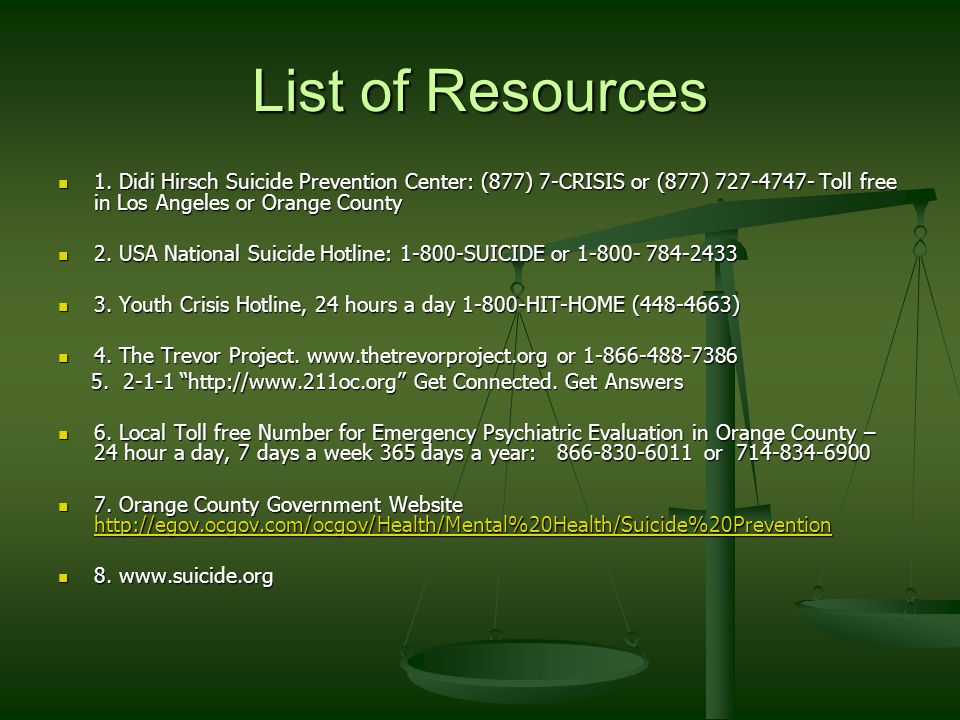

There are other types of crisis programs and mental health resources to turn to, as well, including:

- Hotlines like the National Suicide Prevention Hotline

- Walk-in clinics or psychiatric urgent care centers

- Crisis stabilization units

- Psychiatric hospitals

Patient safety is of the utmost importance during a mental health emergency — patients in crisis need proper environments with regular observations in order to ensure their wellbeing. ObservSMART is a proximity-based compliance technology that prioritizes patient checks and validates they are being completed. It was designed to ensure mental health ER patients are properly monitored and protected. After all, accurate observations can make a life-changing difference for patients at risk of self-harm or suicide.

Learn more about patient safety checks, and the difference ObservSMART can make in treating those who are experiencing psychiatric emergencies.

- Copy Link

- More

Emergency psychological assistance for acute reaction to stress

Based on the materials of the textbook "Psychology of extreme situations

for rescuers and firefighters" under the general editorship. k. psychol. n. Yu.S. Shoigu

k. psychol. n. Yu.S. Shoigu

Extreme situation

Well-known wisdom says: "Life is 10% of what happens to us, and 90% of what we think about it."

Extreme refers to situations that go beyond the usual, "normal" human experience. In other words, the extremeness of the situation is determined by factors to which a person is not yet adapted and is not ready to act in their conditions. The degree of extremeness of the situation is determined by the strength, duration, novelty, unusual manifestation of these factors.

However, it is not only the real, objectively existing threat to life for oneself or significant relatives that makes the situation extreme, but also our attitude to what is happening. The perception of the same situation by each specific person is individual, in connection with which the criterion of "extremeness" is, rather, in the internal, psychological plan of the individual.

The following can be considered as factors determining extremeness:

- Various emotional influences in connection with the danger, difficulty, novelty, responsibility of the situation.

- Lack of necessary information or a clear excess of conflicting information.

- Excessive mental, physical, emotional stress.

- Exposure to adverse climatic conditions: heat, cold, lack of oxygen, etc.

- Presence of hunger, thirst.

Extreme situations (threat of loss of health or life) significantly violate a person's basic sense of security, belief that life is organized in accordance with a certain order and can be controlled, and can lead to the development of painful conditions - traumatic and post-traumatic stress, other neurotic and mental disorders.

Each situation has its own specifics and features, its own mental consequences for participants and witnesses, and is experienced by each person individually. In many ways, the depth of this experience depends on the personality of the person himself, his internal resources, coping mechanisms.

Emergency psychological assistance for acute reaction to stress

Emergency psychological assistance is a system of short-term measures aimed at helping one person, a group of people or a large number of victims after a crisis or emergency event in order to regulate the current psychological, psychophysiological state and negative emotional experiences related to a crisis or emergency event, using professional methods that are appropriate to the requirements of the situation.

Emergency psychological assistance can be provided to one person after a critical event, a group of people (family, professional team, a group of previously unfamiliar people), as well as a large number of victims of a major accident, catastrophe, natural disaster.

The provision of emergency psychological assistance is aimed at maintaining mental and psychophysiological well-being and working with newly emerged (arising as a result of a crisis situation) negative emotional experiences (for example, fear, guilt, anger, helplessness, etc.). Achieving this goal determines a significant reduction in the likelihood of various delayed consequences in victims (psychosomatic problems, etc.)

When providing psychological assistance, it is important to follow the following rules:

- Make sure that the person has no physical injuries, heart problems. Call a doctor if necessary. In a situation where, for some reason, medical assistance cannot be provided immediately, your actions should be as follows:

- tell the victim that help is on the way;

- tell him how to behave: save energy as much as possible; breathe shallowly, slowly, through the nose;

- prohibit the victim from doing anything for self-evacuation, self-liberation.

- When you are near a person who has been psychologically traumatized as a result of extreme factors (accident, loss of loved ones, tragic news, physical or sexual violence, etc.), do not lose your temper. The behavior of the victim should not frighten, annoy or surprise you. His state, actions, emotions are a normal reaction to abnormal circumstances.

- If you feel that you are not ready to help a person, you are afraid, unpleasant to talk to a person, do not do it. Know that this is a normal reaction and you are entitled to it. A person always feels insincerity by posture, gestures, intonations, and an attempt to help through force will still be ineffective. Find someone who can do it.

- The basic principle of helping in psychology is the same as in medicine: "Do no harm." It is better to abandon unreasonable, thoughtless actions than to harm a person. Therefore, if you are not sure about the correctness of what you are going to do, it is better to refrain.

Methods of emergency psychological assistance to others in various psycho-emotional states

HELP WITH FEAR

- Do not leave a person alone. Fear is hard to bear alone.

- Talk about what the person is afraid of. When a person speaks out his fear, it becomes not so strong. If the child is afraid, talk to him about his fears, after that you can play, draw, slap. These activities will help your child express their feelings.

- Do not try to distract the person with phrases such as "Don't think about it", "This is nonsense", "This is nonsense", etc.

- Have the person do some breathing exercises, such as:

- Place your hand on your stomach; inhale slowly, feel how the chest fills with air first, then the stomach. Hold your breath for 1-2 seconds. Exhale. First the belly goes down, then the chest. Slowly repeat this exercise 3-4 times;

- Inhale deeply. Hold your breath for 1-2 seconds.

Start breathing out. Exhale slowly, and about half way through, pause for 1-2 seconds. Try to exhale as much as possible. Slowly repeat this exercise 3-4 times. If the person finds it difficult to breathe in this rhythm, join him - breathe together. This will help him calm down, feel that you are near.

Start breathing out. Exhale slowly, and about half way through, pause for 1-2 seconds. Try to exhale as much as possible. Slowly repeat this exercise 3-4 times. If the person finds it difficult to breathe in this rhythm, join him - breathe together. This will help him calm down, feel that you are near.

ANXIETY HELP

- It is very important to try to get the person to talk and understand what exactly is bothering them. In this case, perhaps the person is aware of the source of anxiety and can calm down.

- Often a person is anxious when he does not have enough information about ongoing events. In this case, you can try to make a plan for when, where and what information can be obtained.

- Try to engage the person in mental (reading, writing) or physical labor (exercises, jogging). If he is carried away by this, then the anxiety will recede.

HELP WITH CRYING

Tears are a way to express your feelings, and you should not immediately begin to calm a person if he is crying. On the other hand, being close to a crying person and not trying to help him is also wrong. It is good if you can express your support and sympathy to a person. It doesn't have to be done in words. You can just sit next to him, hug a person, stroking his head and back, let him feel that you are next to him, that you sympathize and empathize with him. Remember the expressions “cry on your shoulder”, “cry in your vest” - this is exactly what it is about. You can hold a person's hand. Sometimes a helping hand means much more than hundreds of spoken words.

On the other hand, being close to a crying person and not trying to help him is also wrong. It is good if you can express your support and sympathy to a person. It doesn't have to be done in words. You can just sit next to him, hug a person, stroking his head and back, let him feel that you are next to him, that you sympathize and empathize with him. Remember the expressions “cry on your shoulder”, “cry in your vest” - this is exactly what it is about. You can hold a person's hand. Sometimes a helping hand means much more than hundreds of spoken words.

HELP FOR HYSTERIC

Unlike tears, hysteria is a condition that you must try to stop. In this state, a person loses a lot of physical and psychological strength. You can help a person by doing the following:

- Remove the audience, create a calm environment. Stay alone with the person if it is not dangerous for you.

- Unexpectedly perform an action that can be very surprising (for example, you can slap, pour water on the face, drop an object with a roar, shout sharply at the victim).

If such an action cannot be performed, then sit next to the person, hold his hand, stroke his back, but do not enter into a conversation with him or, even more so, into an argument. Any of your words in this situation will only add fuel to the fire.

If such an action cannot be performed, then sit next to the person, hold his hand, stroke his back, but do not enter into a conversation with him or, even more so, into an argument. Any of your words in this situation will only add fuel to the fire. - After the tantrum has subsided, speak to the victim in short phrases, in a confident but friendly tone (“drink some water”, “wash yourself”).

- After the tantrum comes a breakdown. Give the person a chance to rest.

HELP WITH APATHY

In a state of apathy, in addition to a breakdown, indifference piles up, a feeling of emptiness appears. If a person is left without support and attention, then apathy can develop into depression. In this case, you can do the following:

- Talk to the person. Ask him some simple questions based on whether he is familiar to you or not: “What is your name?”, “How do you feel?”, “Do you want to eat?”.

- Escort the victim to a place of rest, help to get comfortable (you must take off your shoes).

- Hold the person's hand or place your hand on their forehead.

- Let him sleep or just lie down.

- If it is not possible, then talk more with the victim, involve him in any joint activity (you can take a walk, go for tea or coffee, help others who need help).

HELP FOR GUILTY OR SHAME

Talk to the person, listen to them. Make it clear that you are listening and understanding (nod, agree, say “uh-huh,” “yeah”). Do not judge a person, do not try to evaluate his actions, even if it seems to you that the person did wrong. Let them know that you accept the person for who they are. Do not try to convince a person (“You are not to blame”, “This can happen to anyone”). At this stage, it is important to let the person speak out, to talk about their feelings. Don't give advice, don't talk about your experience, don't ask questions - just listen.

ASSISTANCE WITH MOTOR EXCITATION

An acute reaction to stress can manifest itself in motor excitement, which can become dangerous for the victim and others. In this case, try to find a way to physically stop the person. Before you try to help him, make sure it's not dangerous for you. Remember, psychological help is possible only if the victim is aware of his actions.

In this case, try to find a way to physically stop the person. Before you try to help him, make sure it's not dangerous for you. Remember, psychological help is possible only if the victim is aware of his actions.

- Ask the person questions that will get their attention, or assign a task that will make them think. Any intellectual activity will reduce the level of physical activity.

- Offer to take a walk, do some physical exercises, do some physical work (bring something, rearrange, etc.), so that he feels physically tired.

- Offer to do breathing exercises together. For example, this one:

- Get up. Take a slow breath, feel how the air fills first the chest, then the stomach. Exhale in the reverse order - first the lower sections of the lungs, then the upper ones. Pause for 1-2 seconds. Repeat the exercise 1 more time. It is important to breathe slowly, otherwise you may feel dizzy from an excess of oxygen.

- Continue breathing deeply and slowly.

At the same time, on each exhalation, try to feel relaxation. Relax your arms, shoulders, back. Feel their heaviness. Concentrate on your breath, imagine that you are exhaling your tension. Take 3-4 breaths. Breathe normally for a while (about 1-2 minutes).

At the same time, on each exhalation, try to feel relaxation. Relax your arms, shoulders, back. Feel their heaviness. Concentrate on your breath, imagine that you are exhaling your tension. Take 3-4 breaths. Breathe normally for a while (about 1-2 minutes). - Breathe slowly again. Now inhale through your nose, and exhale through your mouth, pursing your lips. As you exhale, imagine that you are gently blowing on the candle, being careful not to extinguish the flame. Try to stay relaxed. Repeat the exercise 3-4 times.

NERVOUS RELIEF

- Need to increase trembling. Grab the person by the shoulders and shake them hard, sharply for 10-15 seconds. Keep talking to him, otherwise he may perceive your actions as an attack.

- After the reaction has ended, the victim should be allowed to rest. It is advisable to put him to sleep.

Absolutely not:

- Embrace or hold the casualty close to you.

- Cover the victim with something warm.

- Reassure the victim, tell him to pull himself together.

HELP FOR ANGER, ANGER, AGGRESSION

- Minimize the number of people around you.

- Give the victim an opportunity to "blow off steam" (eg, talk or beat a pillow).

- Assign work that involves high physical activity.

- Show benevolence. Even if you do not agree with the victim, do not blame him, but speak out about his actions. Otherwise, aggressive behavior will be directed at you. You can’t say: “What kind of person are you!”. We must say: “You are terribly angry, you want to smash everything to smithereens. Let's try to find a way out of this situation together."

- Try to defuse the situation with funny comments or actions, but only if it is appropriate. Aggression can be extinguished by fear of punishment if:

- no purpose to gain from aggressive behavior;

- The punishment is severe and the likelihood of its implementation is high.

In conclusion of this chapter, I would like to say that often the help and support of others during and immediately after tragic events help a person to cope with grief, not to fall into a vicious circle of fear, guilt and despair in the future.

A woman whose husband was in a serious car accident and was on the verge of life and death, said that a nurse helped her to gather strength and survive this incredibly difficult period in her life, who allowed her to cry on her shoulder, and then said one short phrase: "You can do it." This phrase became the motto for many months. And now, many years later, the heroine of this story is sure that it was the participation of an almost unknown woman that helped her survive in that situation.

SELF-HELP FOR ACUTE STRESS REACTIONS

So, you find yourself in a situation where you are overcome by strong feelings - mental pain, anger, anger, guilt, fear, anxiety. In this case, it is very important to create conditions for yourself in order to quickly “let off steam”. This will help to slightly reduce stress and preserve the mental strength that is so needed in an emergency. You can try one of the universal ways:

This will help to slightly reduce stress and preserve the mental strength that is so needed in an emergency. You can try one of the universal ways:

- Do physical labor: rearrange furniture, clean, work in the garden.

- Work out, go for a run, or just walk at a moderate pace.

- Take a contrast shower.

- Shout, stamp your feet, break unnecessary dishes, etc.

- Let your tears flow, share your feelings with people you can trust.

Do not drink large amounts of alcohol, as this usually only aggravates the situation.

As you can see, these methods are not psychological techniques, many people intuitively use them in life. For example, often women, when they are angry with their husband or children, start cleaning to avoid a quarrel; men, feeling angry, go to the gym and furiously hit the pear; when we are offended by injustice at work, we complain to our friends.

In addition to universal methods, methods can be proposed that help to cope with each specific reaction.

Fear is a feeling that, on the one hand, protects us from risky, dangerous actions. On the other hand, everyone is familiar with the painful state when fear deprives us of the ability to think and act. You can try to cope with such an attack of fear yourself with the help of the following simple tricks:

- Try to formulate to yourself, and then say out loud what causes fear. If possible, share your experiences with people around you. Expressed fear becomes less.

- When an attack of fear approaches, you need to breathe shallowly and slowly - inhale through your mouth and exhale through your nose. You can try this exercise: take a deep breath, hold your breath for 1-2 seconds, exhale. Repeat the exercise 2 times. Then take 2 normal (shallow) slow breaths. Alternate between deep and normal breathing until you feel better.

Alarm. It is often said that when experiencing fear, a person is afraid of something specific (subway trips, a child's illness, accidents, etc. ), and when experiencing anxiety, a person does not know what he is afraid of. Therefore, the state of anxiety is more severe than the state of fear.

), and when experiencing anxiety, a person does not know what he is afraid of. Therefore, the state of anxiety is more severe than the state of fear. - The first step is to turn anxiety into fear. You need to try to understand what exactly worries. Sometimes this is enough to reduce the tension, and the experience becomes less painful.

- The most painful experience of anxiety is the inability to relax. Muscles are tense, the same thoughts are spinning in the head: therefore, it is useful to make several active movements, physical exercises to relieve tension. Muscle stretching exercises are especially useful.

- Complex mental operations also help reduce anxiety. Try counting. For example: alternately subtract 6 or 7 from 100 in your mind, multiply two-digit numbers, calculate what date the second Monday of the last month fell on. You can remember or compose poetry, invent rhymes, etc.

Cry. Everyone has cried at least once in their life and knows that tears, as a rule, bring significant relief. Crying allows you to express overwhelming emotions. Therefore, this reaction can and should be allowed to take place. Often, seeing a crying person, others rush to calm him down. It is believed that if a person cries, then he feels bad, and if not, then he calmed down or he “holds on”. It has long been known that tears have a healing function: doctors say that tears contain a large amount of the stress hormone, and by crying, a person gets rid of it, it becomes easier for him. This effect is also reflected in the language - they say: “Tears heal”, “Cry, and feel better!”. We cannot assume that tears are a sign of weakness. If you cry, then this does not indicate that you are a "whiner"; you should not be ashamed of your tears. When a person holds back tears, emotional discharge does not occur. If the situation drags on, then the mental and physical health of a person may be damaged. No wonder they say: "I went crazy with grief." Therefore, you do not need to immediately try to calm down, "pull yourself together.

Crying allows you to express overwhelming emotions. Therefore, this reaction can and should be allowed to take place. Often, seeing a crying person, others rush to calm him down. It is believed that if a person cries, then he feels bad, and if not, then he calmed down or he “holds on”. It has long been known that tears have a healing function: doctors say that tears contain a large amount of the stress hormone, and by crying, a person gets rid of it, it becomes easier for him. This effect is also reflected in the language - they say: “Tears heal”, “Cry, and feel better!”. We cannot assume that tears are a sign of weakness. If you cry, then this does not indicate that you are a "whiner"; you should not be ashamed of your tears. When a person holds back tears, emotional discharge does not occur. If the situation drags on, then the mental and physical health of a person may be damaged. No wonder they say: "I went crazy with grief." Therefore, you do not need to immediately try to calm down, "pull yourself together. " Give yourself time and opportunity to cry.

" Give yourself time and opportunity to cry.

However, if you feel that tears no longer bring relief and you need to calm down, the following methods will help:

- Drink a glass of water. This is a well-known and widely used remedy.

- Breathe slowly, but not deeply, but normally, concentrating on the exhalation.

Hysteria is a state when it is very difficult to help oneself with something, because at this moment a person is in an extremely excited emotional state and does not understand well what is happening with him and around him. If a person has the idea that a tantrum should be stopped, this is already the first step towards its end. In this case, you can take the following actions:

- Get away from the "spectators", the witnesses of what is happening, stay alone.

- Wash yourself with ice water - this will help you to come to your senses.

- Do breathing exercises: inhale, hold your breath for 1-2 seconds, slowly exhale through the nose, hold your breath for 1-2 seconds, slowly inhale, etc.

Until you can calm down.

Until you can calm down.

Apathy is a reaction that is aimed at protecting the human psyche. As a rule, it occurs after strong physical or emotional stress. Therefore, if you feel low on energy, if you find it difficult to get yourself together and start doing something, and especially if you realize that you are not able to experience emotions, give yourself the opportunity to rest. Take off your shoes, take a comfortable position, try to relax. Do not abuse drinks containing caffeine (coffee, strong tea), this can only aggravate your condition.

Keep your feet warm, making sure that the body is not tense. Rest for as long as you need.

- If the situation requires you to act, give yourself a short rest, relax, at least for 15-20 minutes.

- Massage your earlobes and fingers - these are places where there are a huge number of biologically active points. This procedure will help you to cheer up a little.

- Have a cup of weak sweet tea.

- Do some physical exercise, but not at a fast pace.

- After that, proceed with the tasks that need to be done. Do the work at an average pace, try to save strength. For example, if you need to get to a certain place, don't run - walk.

- Do not take on several things at once, in such a state attention is scattered and it is difficult to concentrate, especially on several things.

- Try to give yourself a good rest as soon as possible.

Feelings of guilt or shame. Many survivors of violence or loss of loved ones experience feelings of guilt or shame. Dealing with these feelings on your own or without outside help is very difficult. Therefore, consider seeking help from a specialist, this will help you cope with the situation.

When talking about your feelings, use "I'm sorry" or "I'm sorry" instead of "I'm ashamed" or "I'm sorry". Words matter a lot, and phrasing this way can help you evaluate and deal with your experiences.

Write a letter about your feelings. It can be a letter to yourself or to the person you have lost. It often helps to express your feelings.

Motor excitation. A state, in a sense, the opposite of apathy, a person experiences an “overabundance” of energy. There is a need to act actively, but the situation does not require it. If the motor excitation is weakly expressed, then most often the person nervously walks in circles around the room, the hospital corridor. In extreme manifestations of this state, a person can take active actions without being aware of them. For example, after a strong fright, a person runs somewhere, can injure himself and others, and then cannot remember his actions. Motor excitation occurs most often immediately after receiving news of a tragic event (for example, if a person receives news of the death of a close relative) or if a person needs to wait (for example, as they wait for the outcome of a difficult operation in a hospital).

If motor excitation occurs, then:

- try to direct the activity to some business.

You can do exercises, run, walk in the fresh air. Any active actions will help you;

You can do exercises, run, walk in the fresh air. Any active actions will help you; - try to relieve excess voltage. To do this, breathe evenly and slowly. Focus on your breathing. Imagine how you exhale tension with the air. Place your feet and hands in heat, you can actively rub them until a feeling of warmth appears. Put your hand on your wrist, feel your pulse, try to focus on the work of your heart, imagine how it beats measuredly. Modern medicine claims that the sound of a heartbeat makes you feel calm and secure, as this is the sound that everyone hears in a safe and comfortable place - in the womb. If possible, put on some soothing music that you enjoy.

Trembling. Sometimes after a stressful event, a person begins to tremble, often only the hands tremble, and sometimes the whole body trembles. Often this condition is considered harmful and they try to stop it as soon as possible, while with the help of such a reaction we can relieve the excess tension that has appeared in our body due to stress. So, if you are trembling (hands trembling) and you cannot calm down, cannot control this process, try:

So, if you are trembling (hands trembling) and you cannot calm down, cannot control this process, try:

- increase the trembling. The body relieves excess tension - help it;

- do not try to stop this state, do not try to forcefully hold the shaking muscles - in this way you will achieve the opposite result;

- try not to pay attention to the trembling, after a while it will stop by itself.

Anger, anger, aggression. Anger and anger are feelings often experienced by people experiencing adversity. These are natural feelings. Therefore, if you experience anger, it is necessary to release it in such a way that it does not harm you and others. It has been proven that people who hide and suppress aggression experience more health problems than those who know how to express their anger. Try expressing your anger in one of the following ways:

Stamp your foot loudly (hit your hand) and repeat with feeling: “I am angry”, “I am furious”, etc. You can repeat several times until you feel relief.

You can repeat several times until you feel relief.

- Try to express your feelings to the other person.

- Give yourself physical exercise, feel how much physical energy you expend when you get angry.

EMERGENCY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSISTANCE IN EXTREME SITUATIONS / Propaganda / Department of Public Security / Administration structure / Power / Administration of the city district of Togliatti

Emergency psychological care is available for people with acute stress (or OCP - Acute Stress Disorder). This state is an experience of emotional and mental disorganization.

Psychodiagnostics, psychotechniques of influence and the procedure for providing psychological assistance in extreme situations have their own specifics (Sukhov, Derkach 1998).

In particular, psychodiagnostics in extreme situations has its own distinctive features. Under these conditions, due to lack of time, it is not possible to use standard diagnostic procedures. Actions, including those of a practical psychologist, are determined by the contingency plan.

Actions, including those of a practical psychologist, are determined by the contingency plan.

Not applicable in many extreme situations and the usual methods of psychological influence. It all depends on the goals of psychological impact in extreme situations: in one case, you need to support, help; in another, one should stop, for example, rumors, panic; third, negotiate.

The main principles of providing assistance to those who have suffered psychological trauma as a result of extreme situations are:

• urgency;

• proximity to the scene;

• waiting for the normal state to be restored;

• unity and simplicity of psychological influence.

Urgency means that help must be provided as soon as possible: the more time passes since the injury, the greater the likelihood of chronic disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder.

The meaning of the principle of proximity is to provide assistance in the familiar environment and social environment, as well as to minimize the negative consequences of "hospitalism".

Expectation to return to normal: A stressful person should not be treated as a patient but as a normal person. It is necessary to maintain confidence in the imminent return of a normal state.

The unity of psychological impact implies that either one person should act as its source, or the procedure for providing psychological assistance should be unified.

Simplicity of psychological influence - it is necessary to take the victim away from the source of injury, provide food, rest, a safe environment and the opportunity to be heard.

In general, the psychological emergency service performs the following basic functions:

– practical: direct provision of emergency psychological and (if necessary) first aid to the population;

- coordinating: ensuring communication and interaction with specialized psychological services.

The situation of a psychologist working in extreme conditions differs from the usual therapeutic situation in at least the following ways (Lovelle, Mashmonova, 2003):

• Working with groups. Often one has to work with groups of victims, and these groups are not artificially created by a psychologist (psychotherapist), based on the needs of the psychotherapeutic process, they were created by life itself due to the dramatic situation of a catastrophe.

Often one has to work with groups of victims, and these groups are not artificially created by a psychologist (psychotherapist), based on the needs of the psychotherapeutic process, they were created by life itself due to the dramatic situation of a catastrophe.

• Patients are often in an acute affective state. Sometimes it is necessary to work when the victims are still under the effect of the traumatic situation, which is not quite usual for normal psychotherapeutic work.

• The often low social and educational status of many of the victims. Among the victims, one can meet a large number of people who, due to their social and educational status, would never have ended up in a psychotherapist's office in their lives.

• Diversity of psychopathology in victims. Victims of violence often suffer, in addition to traumatic stress, neurosis, psychosis, character disorders and, most importantly for professionals working with victims, a whole range of problems caused by the disaster itself or other traumatic situation. This means, for example, lack of means of subsistence, lack of work, etc.

This means, for example, lack of means of subsistence, lack of work, etc.

• Presence of a feeling of loss in almost all patients, because often the victims lose loved ones, friends, favorite places of residence and work, etc., which contributes to the nosological picture of traumatic stress, especially to the depressive component of this syndrome.

• The difference between post-traumatic psychopathology and neurotic pathology. It can be argued that the psychopathological mechanism of traumatic stress is fundamentally different from the pathological mechanisms of neurosis. Thus, it is necessary to develop strategies for working with victims, which would cover both cases where there is a "pure" traumatic stress, and those cases where there is a complex interweaving of traumatic stress with other pathogenic factors of internal or external origin.

The purpose and objectives of emergency psychological care include the prevention of acute panic reactions, psychogenic neuropsychiatric disorders; increasing the adaptive capacity of the individual; psychotherapy of emerging borderline neuropsychiatric disorders. Emergency psychological assistance to the population should be based on the principle of intervention in the surface layers of consciousness, that is, on working with symptoms, and not with syndromes (Psychotherapy in the center of an emergency, 1998).

Emergency psychological assistance to the population should be based on the principle of intervention in the surface layers of consciousness, that is, on working with symptoms, and not with syndromes (Psychotherapy in the center of an emergency, 1998).

Psychotherapy and psychoprophylaxis are carried out in two directions. The first with the healthy part of the population - in the form of prevention:

a) acute panic reactions;

b) delayed, "delayed" neuropsychiatric disorders.

The second direction is psychotherapy and psychoprophylaxis of persons with developed neuropsychiatric disorders. The technical difficulties of conducting rescue work in areas of catastrophes, natural disasters can lead to the fact that the victims for a sufficiently long time will find themselves in conditions of complete isolation from the outside world. In this case, psychotherapeutic assistance is recommended in the form of emergency "information therapy", the purpose of which is the psychological support / maintenance of the viability of those who are alive, but are in complete isolation from the outside world (earthquakes, destruction of homes as a result of accidents, explosions, etc. ). ). "Information therapy" is implemented through a system of sound amplifiers and consists of broadcasting the following recommendations that victims should hear:

). ). "Information therapy" is implemented through a system of sound amplifiers and consists of broadcasting the following recommendations that victims should hear:

1) information that the outside world is coming to their aid and everything is being done to help them come to them as soon as possible;

2) those in isolation must remain completely calm, as this is one of the main means of their salvation;

3) it is necessary to provide self-help;

4) in case of blockages, the victims should not make any physical efforts to self-evacuate, which may lead to a dangerous displacement of debris;

5) you should save your strength as much as possible;

6) be with your eyes closed, which will bring you closer to a state of light drowsiness and greater economy of physical strength;

7) breathe slowly, shallowly and through the nose, which will save moisture and oxygen in the body and oxygen in the surrounding air;

8) mentally repeat the phrase: “I am completely calm” 5–6 times, alternating these self-suggestions with counting periods up to 15–20, which will relieve internal tension and achieve normalization of the pulse and blood pressure, as well as self-discipline;

9) release from "captivity" may take longer than the victims want. “Be courageous and patient. Help is coming to you."

“Be courageous and patient. Help is coming to you."

The purpose of "information therapy" is also to reduce the feeling of fear in victims, because it is known that in crisis situations more people die from fear than from the impact of a real destructive factor. After the release of the victims from under the rubble of buildings, it is necessary to continue psychotherapy (and, above all, amnestic therapy) in stationary conditions.

Another group of people to whom psychotherapy is applied in emergency situations are relatives of people who are under the rubble, alive and dead. For them, the whole range of psychotherapeutic measures is applicable:

• behavioral techniques and methods aimed at removing psycho-emotional arousal, anxiety, panic reactions;

• existential techniques and methods aimed at accepting the situation of loss, at eliminating mental pain and searching for psychological resource opportunities.

Another group of people who receive psychotherapy in the emergency zone are the rescuers. The main problem in such situations is psychological stress. It is this circumstance that significantly affects the requirements for specialists in emergency services. A specialist needs to have the ability to timely identify the symptoms of psychological problems in himself and his comrades, to possess empathic abilities, the ability to organize and conduct classes on psychological relief, stress relief, emotional tension. Possession of the skills of psychological self-help and mutual assistance in crisis and extreme situations is of great importance not only for preventing mental trauma, but also for increasing resistance to stress and readiness for quick response in emergency situations.

The main problem in such situations is psychological stress. It is this circumstance that significantly affects the requirements for specialists in emergency services. A specialist needs to have the ability to timely identify the symptoms of psychological problems in himself and his comrades, to possess empathic abilities, the ability to organize and conduct classes on psychological relief, stress relief, emotional tension. Possession of the skills of psychological self-help and mutual assistance in crisis and extreme situations is of great importance not only for preventing mental trauma, but also for increasing resistance to stress and readiness for quick response in emergency situations.

As a result of an extensive research program, the German psychologists B. Gash and F. Lasogga (Lasogga, Gash 1997) developed a set of recommendations for a psychologist, other specialist or volunteer working in an emergency situation. These recommendations are useful both for psychologists in their direct work in places of mass disasters, and for the training of rescuers and special services (Romek et al. , 2004).

, 2004).

Rules for rescue workers:

1. Let the victim know that you are nearby and that rescue measures are already underway.

The victim must feel that he is not alone in this situation. Approach the victim and say, for example: “I will stay with you until the ambulance arrives. The victim must also be informed of what is happening now: the ambulance is on its way.”

2. Try to keep the victim away from prying eyes.

Curious looks are very unpleasant for a person in a crisis situation. If onlookers do not leave, give them some task, for example, to drive the curious away from the scene.

3. Establish body contact carefully.

Light body contact usually calms victims. Therefore, take the victim by the hand or pat on the shoulder. Touching the head or other parts of the body is not recommended. Take a position at the same level as the victim. Even when providing medical assistance, try to be on the same level with the victim.

4. Speak and listen.

Speak and listen.

Listen carefully, do not interrupt, be patient as you carry out your duties. Speak yourself, preferably in a calm tone, even if the victim is losing consciousness. Don't be nervous. Avoid reproaches. Ask the victim, "Is there anything I can do for you?" If you feel compassion, feel free to say so.

First aid rules for psychologists:

1. In a crisis situation, the victim is always in a state of mental excitement. This is fine. Optimal is the average level of excitation. Tell the patient right away what you expect from the therapy and how long it will take to work on the problem. The hope of success is better than the fear of failure.

2. Don't take action right away. Look around and decide what kind of help (besides psychological) is required, which of the victims is most in need of help. Give it about 30 seconds with one victim, about five minutes with several victims.

3. Be specific about who you are and what functions you perform. Find out the names of those in need of help. Tell the victims that help will arrive soon, that you took care of it.

Find out the names of those in need of help. Tell the victims that help will arrive soon, that you took care of it.

4. Gently establish body contact with the casualty. Take the victim by the hand or pat on the shoulder. Touching the head or other parts of the body is not recommended. Take a position at the same level as the victim. Do not turn your back on the victim.

5. Never blame the victim. Tell us what steps need to be taken to help in his case.

6. Professional competence is reassuring. Tell us about your qualifications and experience.

7. Let the victim believe in his own competence. Give him a task that he can handle. Use this to convince him of his own abilities, so that the victim has a sense of self-control.

8. Let the victim talk. Listen actively to him, be attentive to his feelings and thoughts. Retell the positive.

9. Tell the victim that you will stay with him. When parting, find substitutes for yourself and instruct him on what to do with the victim.

10. Recruit people from the victim's immediate environment to provide assistance. Instruct them and give them simple tasks. Avoid any words that may make someone feel guilty.

11. Try to protect the victim from excessive attention and questions. Give curious specific tasks.

12. Stress can also have a negative impact on a psychologist. It makes sense to remove the tension that arises during such work with the help of relaxation exercises and professional supervision. Supervision groups should be led by a professionally trained moderator.

When providing emergency psychological assistance, it must be remembered that victims of natural disasters and catastrophes suffer from the following factors caused by an extreme situation (Everstine, Eversline, 1993):

1. Surprise. Few disasters wait for potential victims to be warned - for example, gradually reaching a critical phase of flooding or an impending hurricane, storm. The more sudden the event, the more devastating it is for the victims.

2. Lack of similar experience. Because disasters and catastrophes are fortunately rare, people often learn to deal with them when they are stressed.

3. Duration. This factor varies from case to case. For example, a gradually developing flood can subside just as slowly, while an earthquake lasts a few seconds and brings much more destruction. However, in victims of some long-term extreme situations (for example, in cases of hijacking), traumatic effects can multiply with each subsequent day.

4. Lack of control. No one is able to control events during disasters: it can take a long time before a person can control the most ordinary events of everyday life. If this loss of control persists for a long time, even competent and independent people may show signs of "learned helplessness."

5. Grief and loss. Disaster victims may be separated from loved ones or lose someone close to them; the worst thing is to wait for news of all possible losses. In addition, the victim may lose his social role and position due to the disaster. In the case of prolonged traumatic events, a person may lose all hope of restoring what has been lost.

In the case of prolonged traumatic events, a person may lose all hope of restoring what has been lost.

6. Constant change. The destruction caused by a disaster may be irreversible: the victim may find himself in completely new and hostile conditions.

7. Exposition of death. Even short life-threatening situations can change a person's personality structure and his "cognitive map". Repeated encounters with death can lead to profound changes at the regulatory level. In a close encounter with death, a severe existential crisis is very likely.

8. Moral uncertainty. The victim of a disaster may be faced with having to make life-changing value-based decisions, such as who to save, how much to risk, who to blame.

9. Behavior during the event. Everyone would like to look their best in a difficult situation, but few succeed. What a person did or didn't do during a disaster can haunt him long after other wounds have healed.

10. Scale of destruction. After the disaster, the survivor will most likely be amazed at what she has done to his environment and social structure.+IN+SF.jpg) Changes in cultural norms force a person to adapt to them or remain a stranger: in the latter case, emotional damage is combined with social maladaptation.

Changes in cultural norms force a person to adapt to them or remain a stranger: in the latter case, emotional damage is combined with social maladaptation.

An important place is occupied by the question of the dynamics of psychogenic disorders that have developed in dangerous situations. A lot of special researches are devoted to it. In accordance with the work of the National Institute of Mental Health (USA), mental reactions during disasters are divided into four phases: heroism, "honeymoon", disappointment and recovery.

1. The heroic phase begins immediately at the moment of the catastrophe and lasts several hours, it is characterized by altruism, heroic behavior caused by the desire to help people, save themselves and survive. False assumptions about the possibility of overcoming what happened occur precisely in this phase.

2. The "honeymoon" phase begins after the disaster and lasts from a week to 3-6 months. Those who survive have a strong sense of pride for overcoming all the dangers and staying alive. In this phase of the disaster, the victims hope and believe that soon all problems and difficulties will be resolved.

In this phase of the disaster, the victims hope and believe that soon all problems and difficulties will be resolved.

3. The disappointment phase usually lasts from 2 months to 1-2 years. Strong feelings of disappointment, anger, resentment and bitterness arise from the collapse of hopes.

4. The recovery phase begins when survivors realize that they themselves need to improve their lives and solve problems that arise, and take responsibility for the implementation of these tasks.

Another classification of successive phases or stages in the dynamics of the state of people after traumatic situations is proposed in the work of Reshetnikova et al. (1989):

1. “Acute emotional shock”. It develops after the state of torpor and lasts from 3 to 5 hours; characterized by general mental stress, extreme mobilization of psychophysiological reserves, sharpening of perception and an increase in the speed of thought processes, manifestations of reckless courage (especially when saving loved ones) while reducing the critical assessment of the situation, but maintaining the ability to expedient activity. The emotional state during this period is dominated by a feeling of despair, accompanied by sensations of dizziness and headache, palpitations, dry mouth, thirst and shortness of breath. Up to 30% of those surveyed, with a subjective assessment of deterioration, simultaneously note an increase in working capacity by 1.5–2 times or more.

The emotional state during this period is dominated by a feeling of despair, accompanied by sensations of dizziness and headache, palpitations, dry mouth, thirst and shortness of breath. Up to 30% of those surveyed, with a subjective assessment of deterioration, simultaneously note an increase in working capacity by 1.5–2 times or more.

2. Psychophysiological demobilization. Duration up to three days. For the vast majority of those surveyed, the onset of this stage is associated with the first contacts with those who were injured and with the bodies of the dead, with an understanding of the scale of the tragedy (“stress of awareness”). It is characterized by a sharp deterioration in well-being and psycho-emotional state with a predominance of a feeling of confusion, panic reactions (often irrational), a decrease in the moral normative behavior, a decrease in the level of activity efficiency and motivation for it, depressive tendencies, some changes in the functions of attention and memory (as a rule, those examined are not can clearly remember what they did during those days). Most of the respondents complain in this phase of nausea, “heaviness” in the head, discomfort in the gastrointestinal tract, and a decrease (even lack) of appetite. The same period includes the first refusals to perform rescue and "clearing" works (especially those related to the extraction of the bodies of the dead), a significant increase in the number of erroneous actions when driving vehicles and special equipment, up to the creation of emergency situations.

Most of the respondents complain in this phase of nausea, “heaviness” in the head, discomfort in the gastrointestinal tract, and a decrease (even lack) of appetite. The same period includes the first refusals to perform rescue and "clearing" works (especially those related to the extraction of the bodies of the dead), a significant increase in the number of erroneous actions when driving vehicles and special equipment, up to the creation of emergency situations.

3. "Permission stage" - 3-12 days after the disaster. According to the subjective assessment, the mood and well-being are gradually stabilizing. However, according to the results of observations, the vast majority of the surveyed retain a reduced emotional background, limited contacts with others, hypomia (masque face), a decrease in the intonation coloring of speech, and slowness of movements. By the end of this period, there is a desire to "speak out", implemented selectively, directed mainly at persons who were not eyewitnesses of the natural disaster, and accompanied by some agitation.

At the same time, dreams appear that were absent in the two previous phases, including disturbing and nightmarish dreams, in various ways reflecting the impressions of tragic events.

Against the background of subjective signs of some improvement in the condition, a further decrease in physiological reserves (by type of hyperactivation) is objectively noted. Overwork phenomena are progressively increasing. The average indicators of physical strength and performance (in comparison with the normative data for the studied age group) are reduced by 30%, and by 50% in terms of hand dynamometry (in some cases up to 10-20 kg). On average, mental performance decreases by 30%, signs of pyramidal interhemispheric asymmetry syndrome appear.

4. “Recovery stage”. It begins approximately from the 12th day after the catastrophe and is most clearly manifested in behavioral reactions: interpersonal communication is activated, the emotional coloring of speech and facial reactions begins to normalize, for the first time after the catastrophe, jokes that evoke an emotional response from others can be noted, normal dreams are restored.