Eating disorders affect brain

Eating disorder behaviors alter reward response in the brain

You are here

Home » News & Events » News Releases

News Release

Wednesday, June 30, 2021

NIH-funded study finds changes can affect food intake control circuitry and cause disorders to progress.

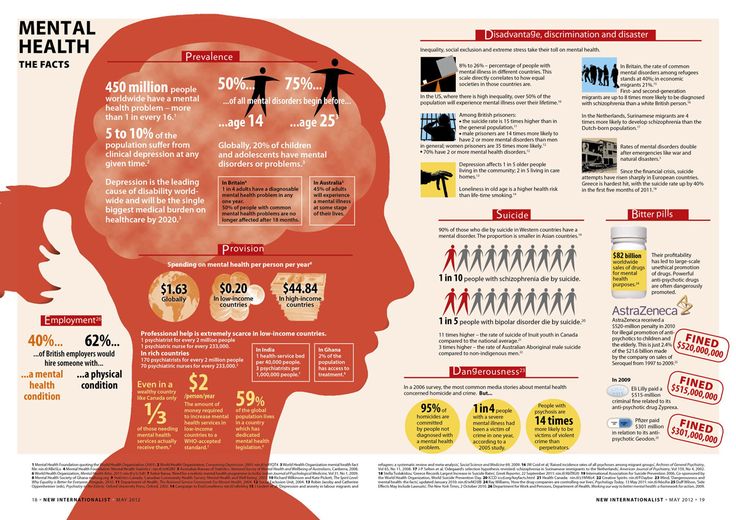

Researchers have found that eating disorder behaviors, such as binge-eating, alter the brain’s reward response process and food intake control circuitry, which can reinforce these behaviors. Understanding how eating disorder behaviors and neurobiology interact can shed light on why these disorders often become chronic and could aid in the future development of treatments. The study, published in JAMA Psychiatry, was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

“This work is significant because it links biological and behavioral factors that interact to adversely impact eating behaviors,” said Janani Prabhakar, Ph.D., of the Division of Translational Research at the National Institute of Mental Health, part of NIH. “It deepens our knowledge about the underlying biological causes of behavioral symptom presentation related to eating disorders and will give researchers and clinicians better information about how, when, and with whom to intervene.”

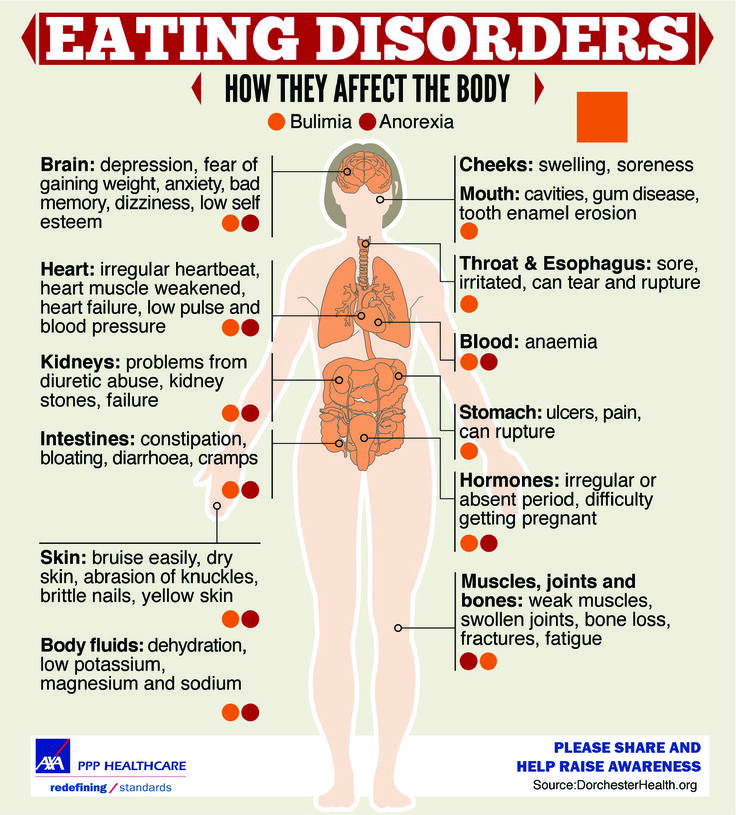

Eating disorders are serious mental illnesses that can lead to severe complications, including death. Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. Behaviors associated with eating disorders can vary in type and severity and include actions such as binge-eating, purging, and restricting food intake.

In this study, Guido Frank, M.D., at the University of California San Diego, and colleagues wanted to see how behaviors across the eating disorder spectrum affect reward response in the brain, how changes in reward response alter food intake control circuitry, and if these changes reinforce eating disorder behaviors. The study enrolled 197 women with different eating disorders (including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, and other specified feeding and eating disorders) and different body mass indexes (BMIs) associated with eating disorder behaviors, as well as 120 women without eating disorders.

The researchers used cross-sectional functional brain imaging to study brain responses during a taste reward task. During this task, participants received or were denied an unexpected, salient sweet stimulus (a taste of a sugar solution). The researchers analyzed a brain reward response known as “prediction error,” a dopamine-related signaling process that measures the degree of deviation from the expectation, or how surprised a person was receiving the unexpected stimulus. A higher prediction error indicates that the person was more surprised, while a lower prediction error indicates they were less surprised. They also investigated whether this brain response was associated with ventral-striatal-hypothalamic circuitry, a neural system associated with food intake control.

The researchers found that there was no significant correlation between BMI, eating disorder behavior, and brain reward response in the group of women without eating disorders. In the group of women with eating disorders, higher BMI and binge-eating behaviors were associated with lower prediction error response. Further, for the women with eating disorders, the direction of ventral striatal-hypothalamic connectivity was the reverse of those without eating disorders, with connectivity directed from the ventral striatum to the hypothalamus. This connectivity was positively related to the prediction error response and negatively related to feeling out of control after eating.

Further, for the women with eating disorders, the direction of ventral striatal-hypothalamic connectivity was the reverse of those without eating disorders, with connectivity directed from the ventral striatum to the hypothalamus. This connectivity was positively related to the prediction error response and negatively related to feeling out of control after eating.

These results suggest that for the women with eating disorders, eating disorder behaviors and excessive weight loss or weight gain modulated the brain’s dopamine-related reward circuit response, altering brain circuitry associated with food intake control, and potentially reinforcing eating disorder behaviors. For example, women with anorexia nervosa, restrictive food intake, and low BMIs had a high prediction error response. This response may strengthen their food intake-control circuitry, leading these women to be able to override hunger cues. In contrast, the opposite seems to be the case for women with binge-eating episodes and higher BMIs.

“The study provides a model for how behavioral traits promote eating problems and changes in BMI, and how eating disorder behaviors, anxiety, mood, and brain neurobiology interact to reinforce the vicious cycle of eating disorders, making recovery very difficult,” said Dr. Frank.

Overall, this study suggests that behavioral traits, including food intake behavior, contribute to eating disorder maintenance and progression by modulating one’s internal reward response and altering food intake control circuitry. However, further research is needed to investigate treatments that could target and change behaviors for individuals with eating disorders to achieve lasting recovery.

Grants: MH096777, Mh203436

About the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): The mission of the NIMH is to transform the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses through basic and clinical research, paving the way for prevention, recovery, and cure. For more information, visit the NIMH website.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.

NIH…Turning Discovery Into Health®

References

Frank, G. K. W., Shott, M. E., Stoddard, J., Swindle, S., & Pryor, T. (2021) Reward processing across the eating disorders spectrum implicates body mass index and ventral striatal-hypothalamic circuitry. JAMA Psychiatry. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1580

###

Connect with Us

- Contact Us

- YouTube

- Flickr

Groundbreaking study shows substantial differences in brain structure in people with anorexia

New findings from the largest study to date by an international group of neuroscience experts show significant reductions in grey matter in people with anorexia nervosa.

By Sidney Taiko Sheehan

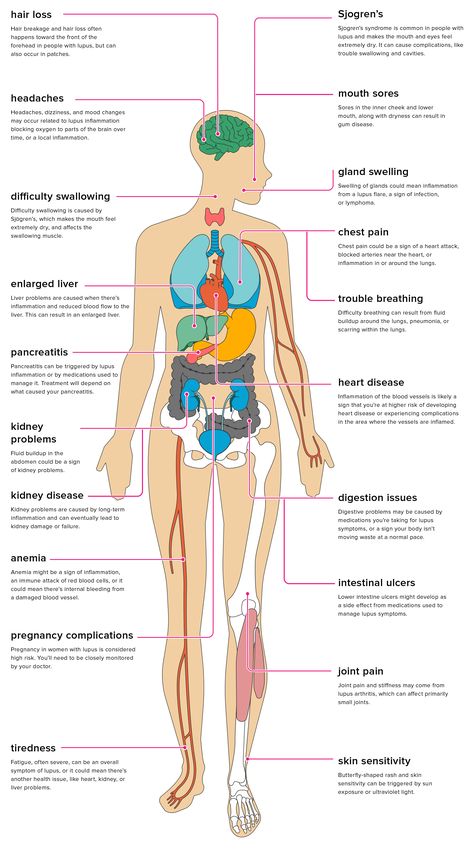

Brain Shrinkage in Anorexia: Compiled from worldwide brain scans in the largest study to date, these brain maps show (in warmer colors) brain regions with gray matter deficits—abnormal tissue reductions—in anorexia. Deficits are less strong in partially-weight restored individuals (upper images) than those in the acute phase (lower images) suggesting the importance and benefits of early interventions. (Photo credit: ENIGMA Anorexia Working Group)

Eating disorders are often misunderstood as lifestyle choices gone awry or oversimplified as the unfortunate result of societal pressures. These misconceptions obscure the fact that eating disorders are serious and potentially fatal mental illnesses that can be treated effectively with early intervention. Mortality rates for people with eating disorders are high compared to other mental illnesses, particularly for those with anorexia nervosa, a condition characterized by a severe restriction of food intake and an abnormally low body weight. People with anorexia can literally starve themselves, causing severe and potentially fatal medical complications. The second leading cause of death for people with anorexia is suicide.

People with anorexia can literally starve themselves, causing severe and potentially fatal medical complications. The second leading cause of death for people with anorexia is suicide.

Now, a groundbreaking new study by a global team of researchers led by the Keck School of Medicine of USC’s Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute (Stevens INI) has revealed that individuals with anorexia demonstrate notable reductions in three critical measures of the brain: cortical thickness, subcortical volumes, and cortical surface area. These reductions are between two and four times larger than the abnormalities in brain size and shape of individuals with other mental illnesses. Reductions in brain size are particularly concerning, as they may imply the destruction of brain cells or the connections between them.

Equipped with these results, the research team is calling attention to the pressing need for prompt treatment to help people with anorexia avoid long-term, structural brain changes, which could lead to a variety of additional medical issues. Anorexia can be successfully treated with healthy weight gain and cognitive behavioral therapy. Ongoing work by the same group shows that successful treatment can have a positive impact on brain structure.

Anorexia can be successfully treated with healthy weight gain and cognitive behavioral therapy. Ongoing work by the same group shows that successful treatment can have a positive impact on brain structure.

“By comparing nearly 2,000 pre-existing brain scans for people with anorexia, people in recovery and healthy controls, we found that for people in recovery from anorexia, reductions in brain structure were less severe,” says Paul M. Thompson, PhD, associate director of the Stevens INI. “This implies that early treatment and support can help the brain to repair itself.”

Paul M. Thompson, PhD, Associate Director, Stevens INI; Director, Imaging Genetics Center (Photo INI)

In addition to researchers from the Stevens INI, the research team includes neuroscientists from the Technical University in Dresden, Germany; the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York; University of Bath, UK; and King’s College London. The researchers came together under the ENIGMA Eating Disorders working group (ENIGMA-ED), a part of the ENIGMA Consortium, co-founded and led by Thompson. ENIGMA is an international effort to bring together researchers in imaging genomics, neurology, and psychiatry, to understand the link between brain structure, function and mental health.

ENIGMA is an international effort to bring together researchers in imaging genomics, neurology, and psychiatry, to understand the link between brain structure, function and mental health.

Through advances in neuroimaging, researchers are gaining a better understanding of the link between serious mental health disorders and brain abnormalities. By demonstrating the effects of anorexia on brain structure, ENIGMA-ED has underscored the severity of the condition and the need for early intervention, while paving the way for the development of more effective treatments.

“The international scale of this work is extraordinary. Because scientists from twenty-two centers worldwide pooled their brain scans together, we were able to create the most detailed picture to date of how anorexia affects the brain, “says Thompson, professor of ophthalmology, neurology, psychiatry and the behavioral sciences, radiology, pediatrics and engineering. “The brain changes in anorexia were more severe than in any other psychiatric condition we have studied. Effects of treatments and interventions can now be evaluated, using these new brain maps as a reference.”

Effects of treatments and interventions can now be evaluated, using these new brain maps as a reference.”

“This study exemplifies why the work at the Stevens INI is so essential,” says INI Director and longtime colleague of Thompson, Arthur W. Toga, PhD. “The goal of the ENIGMA Consortium is to bring researchers together from around the world so that we can combine existing data samples and really improve our power to examine the brain and detect the subtle brain alterations associated with a given illness. At the Stevens INI we apply this goal to all our large-scale studies. We are committed to participating in large studies with diverse research cohorts and sharing data to advance the entire scientific community.”

About ENIGMA ED

ENIGMA-ED is dedicated to improving our understanding of structural brain changes in patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa and how those changes normalize during or after recovery. This group aims to conduct a meta-analysis of existing MRI data with adolescents and adults who have or had an eating disorder in the past. ENIGMA-ED welcomes new cohorts. For more information on how to join and contribute anorexia nervosa data, contact Dr. Stefan Ehrlich ([email protected]). To join and contribute bulimia nervosa data, contact Dr. Laura Berner ([email protected]).

ENIGMA-ED welcomes new cohorts. For more information on how to join and contribute anorexia nervosa data, contact Dr. Stefan Ehrlich ([email protected]). To join and contribute bulimia nervosa data, contact Dr. Laura Berner ([email protected]).

Several researchers at the Stevens INI have also partnered with Stuart Murray, director of the Eating Disorders Program at the Keck School of Medicine of USC to study binge eating disorder in young children. See their most recent findings here and here.

Access the full study ‘Brain Structure in Acutely Underweight and Partially Weight-Restored Individuals with Anorexia Nervosa – A Coordinated Analysis by the ENIGMA Eating Disorders Working Group’ published in the Journal Biological Psychiatry. Other USC co-authors contributing to the study include Neda Jahanshad, PhD, associate professor of neurology and biomedical engineering, and Sophia Thomopoulos, BS, consortium manager for the ENIGMA study.

Reward response in the brain in eating disorders

Image by Tumi from Pixabay

08/13/2021

Researchers have found that eating disorders, such as overeating, alter how the brain responds to rewards and control food intake, which can lead to increased reward behaviors. Understanding how eating disorders and neuroscience interact could shed light on why these disorders often become chronic and could help develop future treatments. The study, published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry, was supported by the National Institutes of Health. nine0003

“This work is important because it links biological and behavioral factors that interact to negatively influence eating behavior,” says researcher Janani Prabhakar from the Division of Translational Research at the National Institute of Mental Health.

“This deepens our knowledge of the underlying biological causes of behavioral symptoms associated with eating disorders and will provide researchers and clinicians with better information on how, when, and how to intervene.

” nine0003

Eating disorders are serious mental disorders that can lead to serious complications, including death. The most common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating. Behaviors associated with eating disorders (EDD) can vary in type and severity and include activities such as binge eating, purging, and restricting food intake.

In this study, Guido Frank, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues wanted to understand how behaviors across the spectrum of eating disorders affect the reward response in the brain, and how changes in reward response affect the control circuitry. food intake and whether these changes exacerbate eating disorders. nine0003

The study included 197 women with various eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating and other specific eating and eating disorders) and various body mass indexes (BMI) associated with eating disorders, as well as 120 women without eating disorders.

Researchers used one-time functional brain imaging to study how the brain responds to a taste reward task. During this task, participants received an unexpected, palpable sweet stimulus (the taste of a sugar solution), or were deprived of it. nine0003

Researchers analyzed the brain's response to reward, known as "prediction error," a dopamine-related signaling process that measures the extent to which a person deviates from expectation or surprise when given an unexpected stimulus. A higher prediction error indicates that the person was more surprised, while a lower prediction error indicates that they were less surprised. They also examined whether this brain response was related to the ventral striatal hypothalamic circuitry in the brain responsible for controlling food intake. nine0003

The researchers found that in the group of women without eating disorders, there was no significant correlation between body mass index, eating disorders, and reward response in the brain.

In the group of women with eating disorders, higher body mass index and overeating were associated with lower response to prediction error.

In addition, in women with eating disorders, the direction of the ventral striatal-hypothalamic connection was reversed compared to women without eating disorders, with the connection being directed from the ventral striatum (striatum) to the hypothalamus. This association was positively associated with response to prediction error and negatively associated with feeling out of control after eating. nine0003

These results suggest that in women with eating disorders, the disorder itself and excessive weight loss or gain modulate the brain's dopamine reward circuitry response, altering brain circuits associated with food control, potentially reinforcing behaviors associated with eating disorders .

For example, women with anorexia nervosa, food restriction, and low body mass index had a high response to prediction error. nine0003

nine0003

This response may increase their food control circuitry, allowing these women to suppress their hunger signals. In contrast, women with binge eating episodes and higher body mass index show the opposite.

“The study provides a model of how behavioral traits contribute to eating problems and changes in body mass index, as well as how eating disorders, anxiety, mood and brain neuroscience interact to reinforce the vicious cycle of eating disorders that makes it very difficult recovery,” says Dr. Frank. nine0003

Overall, this study suggests that behavioral traits, including eating behavior, contribute to the maintenance and progression of eating disorders by modulating intrinsic reward responses and altering the food management pattern. However, further research is needed to explore treatments that could target and change the behavior of people with eating disorders to achieve long-term recovery.

Share link

Labelanorexia bulimia dopamine brain obesity EDD

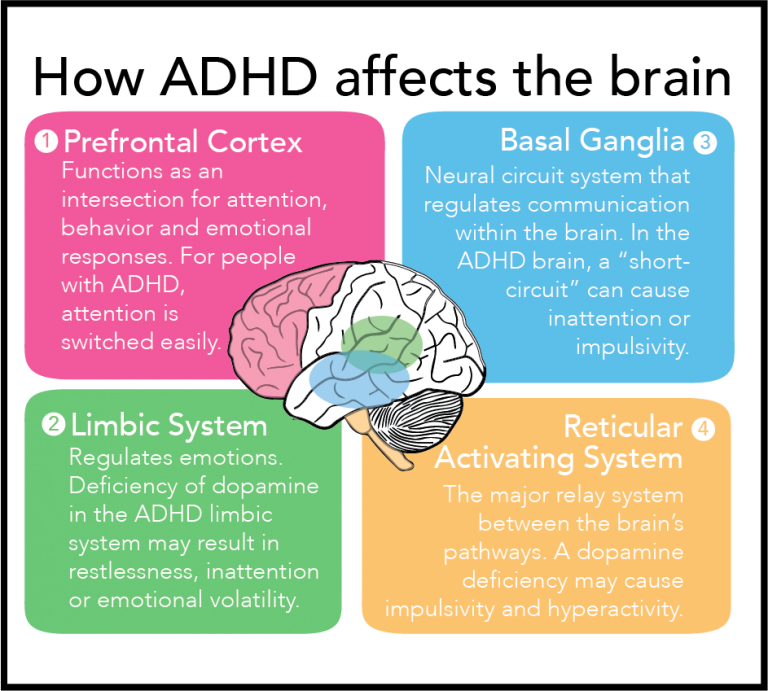

Previous ADHD symptoms and hypersexuality

Next New drug treatment for PTSD

Don't miss

Eating disorders affect many adolescents and young people with different identities. However, …

However, …

From childhood, Hal Blumenfeld wondered about the nature of human consciousness. “This is what makes us…

Anorexia can lead to serious changes in the structure of the brain It is also dangerous for the brain, a new study has shown. The thinking organ does not receive sufficient nutrition, which causes its structure to change seriously and critical indicators to decrease.

Based on 1648 brain scans of women (685 with anorexia nervosa) collected from 22 different locations, the researchers found a decrease in cortical thickness, subcortical volumes and cortical surface area in people with anorexia. In fact, the brain seems to shrink. nine0003

In terms of sample size, this is the largest study to date examining the relationship between eating disorder and gray matter, and it shows how important it is to treat the condition as early as possible in its development.

“For this study, we worked intensively for several years with research groups around the world,” says psychologist Esther Walton from the University of Bath in the UK.

"Being able to combine thousands of brain scans of people with anorexia has allowed us to study in much greater detail the brain changes that can characterize this disorder." nine0003

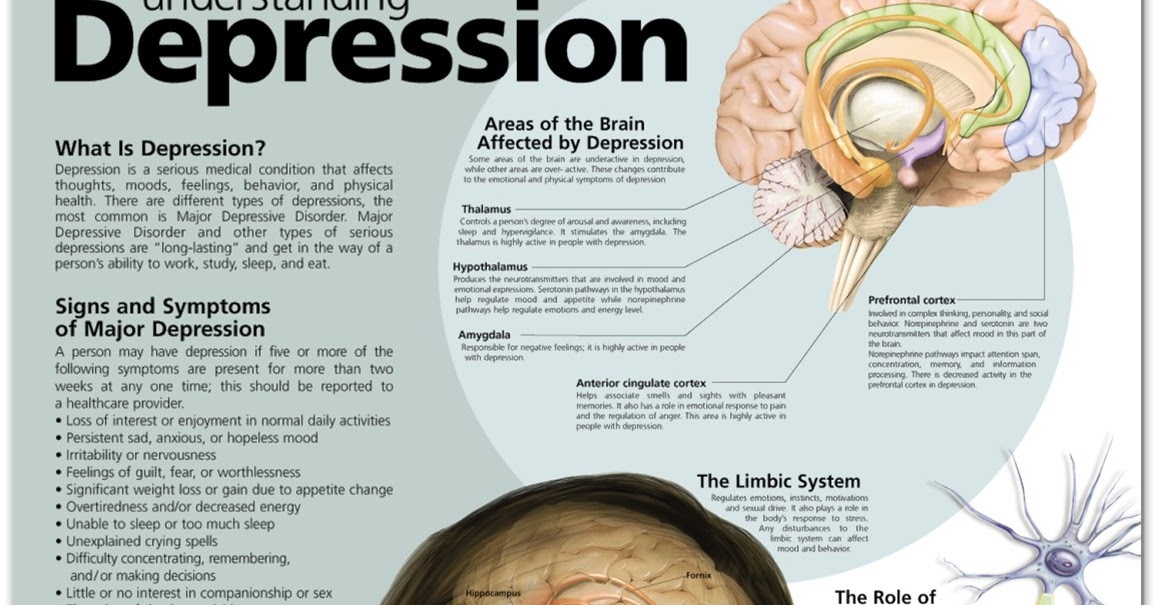

Researchers say the reduction in brain size and shape shown in this study is two to four times greater than the reduction caused by other psychological conditions such as depression, ADHD, and OCD.

What causes these reductions is not explored in this study, but the team behind it suggests that the decline in body mass index (BMI) and available nutrients is likely something to do with it.

However, there are also signs of hope in research: Brain scans have shown that treatment for anorexia, which usually includes cognitive behavioral therapy, may possibly reverse some of these changes in the brain. nine0003

“We found that the big changes in brain structure that we saw in patients were less noticeable in patients already on the road to recovery,” says Walton.

“That’s a good sign because it indicates that these changes may not be permanent. With the right treatment, the brain can return to normal.”

Although scientists are not sure what causes anorexia, we know much more about its effects. It affects millions of people around the world and is one of the leading causes of death associated with mental health problems. nine0003

As more data becomes available in future studies, scientists will be able to better understand what exactly causes this decrease in brain volume in people with anorexia, as well as some of the neurological mechanisms behind it.

At the moment it is clear that the sooner a treatment is found and prescribed, the better. The same methods as here can be used to measure the effectiveness of treating brain damage.

“The effects of treatments and interventions can now be assessed using these new brain maps as a benchmark,” says neurologist Paul Thompson of the University of Southern California.