Dsm mental health diagnosis

What It Is & What It Diagnoses

What is the DSM-5?

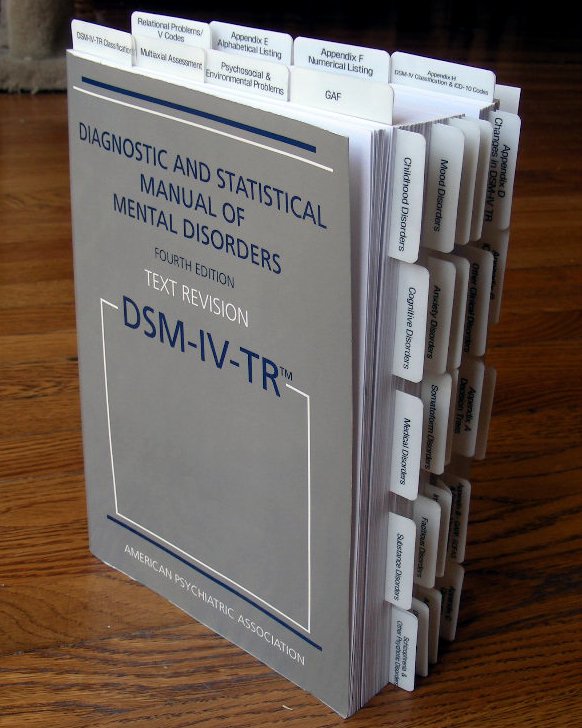

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, often known as the “DSM,” is a reference book on mental health and brain-related conditions and disorders. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is responsible for the writing, editing, reviewing and publishing of this book.

The number “5” attached to the name of the DSM refers to the fifth — and most recent — edition of this book. The DSM-5®’s original release date was in May 2013. The APA released a revised version of the fifth edition in March 2022. That version is known as the DSM-5-TR™, with TR meaning “text revision.”

IMPORTANT: The DSM-5 and DSM-5-TR are medical reference books intended for experts and professionals. The content in these books is very technical, though people who aren’t medical professionals may still find it interesting or educational. However, you shouldn’t use either of these books as a substitute for seeing a trained, qualified mental health or medical provider.

Additionally, the APA also publishes books that supplement the content in the DSM-5-TR. Examples of these supplement publications include the DSM-5 Handbook of Differential Diagnosis and DSM-5 Clinical Cases.

What is the purpose of the DSM-5?

The first step in treating any health condition — physical or mental — is accurately diagnosing the condition. That’s where the DSM-5 comes in. It provides clear, highly detailed definitions of mental health and brain-related conditions. It also provides details and examples of the signs and symptoms of those conditions.

In addition to defining and explaining conditions, the DSM-5 organizes those conditions into groups. That makes it easier for healthcare providers to accurately diagnose conditions and tell them apart from conditions with similar signs and symptoms.

How was the DSM-5 content created?

To create the DSM-5, the APA gathered more than 160 mental healthcare professionals from around the world, including psychiatrists, psychologists and experts from many other professional fields. Hundreds of other professionals contributed and assisted as advisers on specific topics. The creation of the DSM-5 also involved field trials and tests.

Hundreds of other professionals contributed and assisted as advisers on specific topics. The creation of the DSM-5 also involved field trials and tests.

For the DSM-5-TR, the APA called on many of those involved in the initial DSM-5 release. In all, more than 200 professionals directly contributed to the DSM-5-TR.

What topics does the DSM-5 cover?

The DSM-5 mainly focuses on mental health conditions. However, because mental health and brain function are inseparable, the DSM-5 also covers conditions and concerns related to how the brain works. The book also contains diagnostic codes, which make it easier for healthcare providers to cross-reference conditions against the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Edition (ICD-10).

The DSM-5 has three sections:

- Section I: DSM-5 Basics. This section covers how medical professionals should use the book in their work.

It also includes guidance on using the DSM-5 when mental health concerns involve legal professionals, court cases, etc.

It also includes guidance on using the DSM-5 when mental health concerns involve legal professionals, court cases, etc. - Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes. This section is the largest in the book. Each chapter covers a type of condition, with the specific conditions defined and explained within (see the table below for more about this section).

- Section III: Emerging Measures and Models. This section contains information about specific assessment tools, which providers use as guidelines for diagnosing some conditions. It also has information about how cultural differences may affect a diagnosis, and a chapter about conditions that may eventually go into a later edition of the DSM but need further study before that happens.

More about Section II and the types of conditions it covers

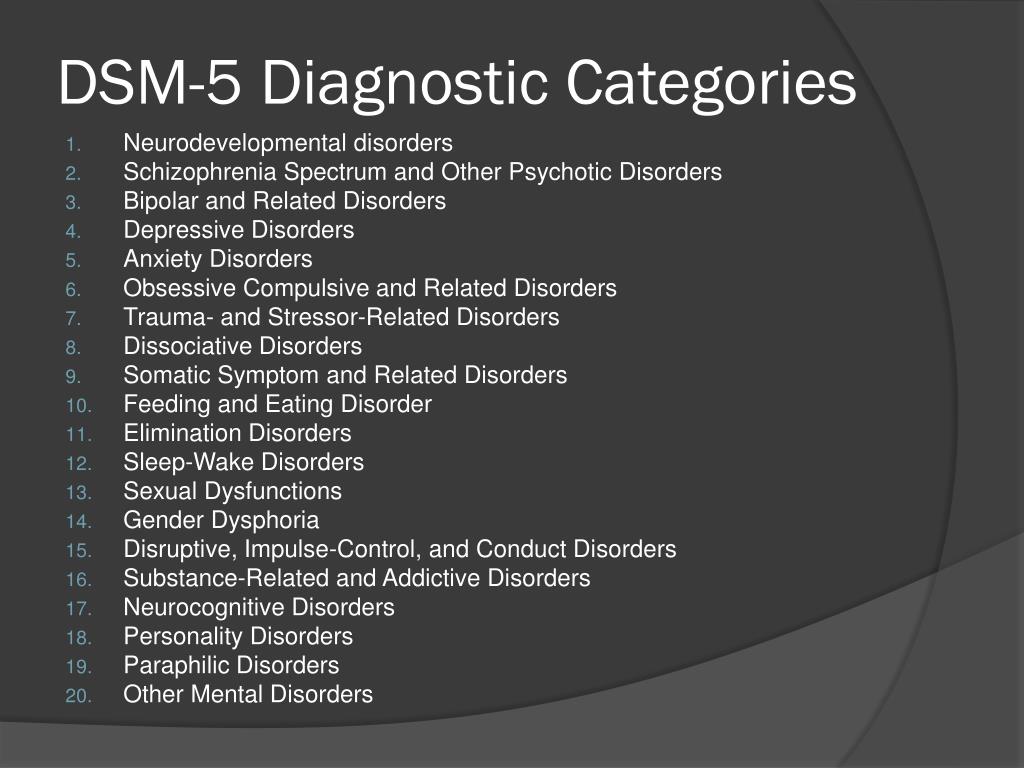

The types of conditions that can be found in the DSM-5 include:

| Section title | Examples of disorders in that section |

|---|---|

| Neurodevelopmental Disorders | Autism spectrum disorder. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Learning disorders (which covers dyslexia, dyscalculia, etc.). |

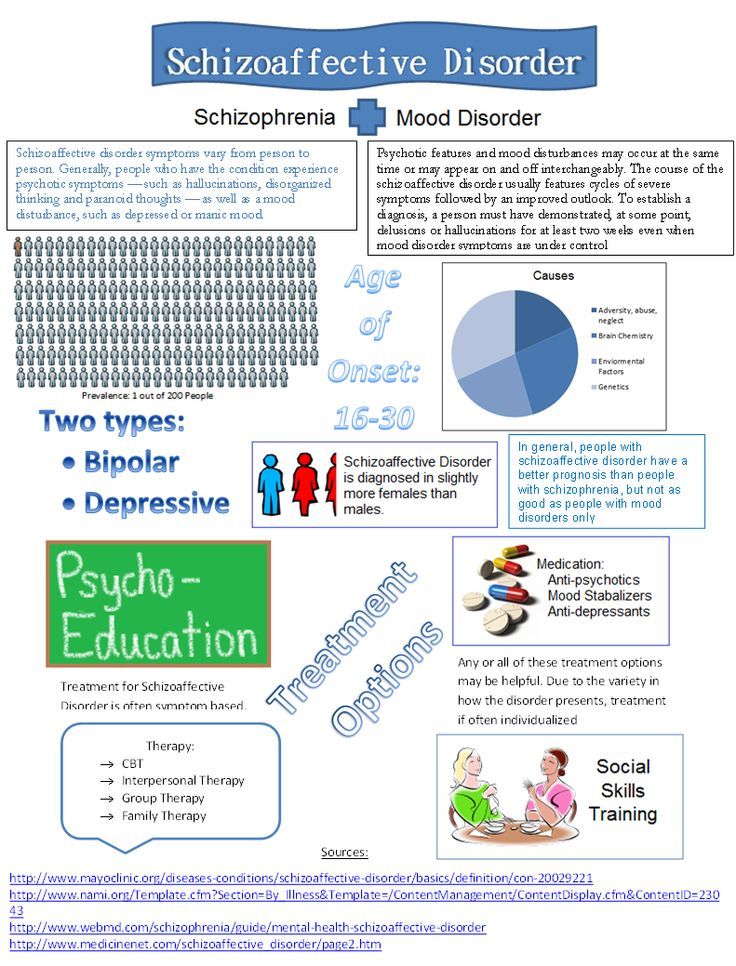

| Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders | Schizophrenia. Schizoaffective disorder. Delusional disorder. |

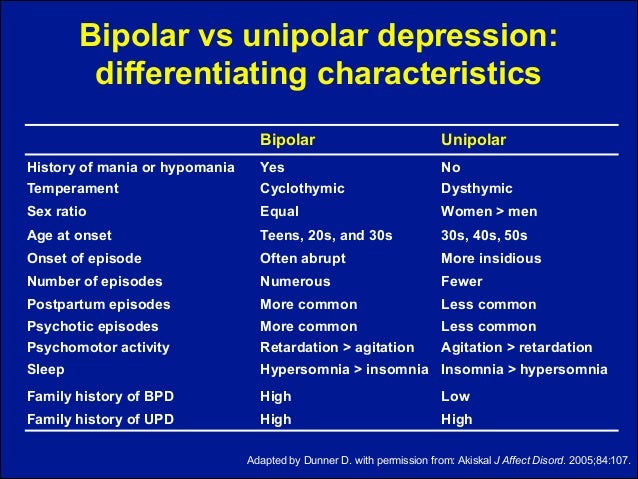

| Bipolar and Related Disorders | Bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Cyclothymic disorder. |

| Depressive Disorders | Major depressive disorder. Persistent depressive disorder. |

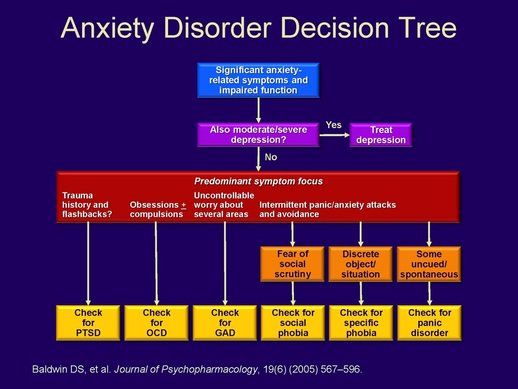

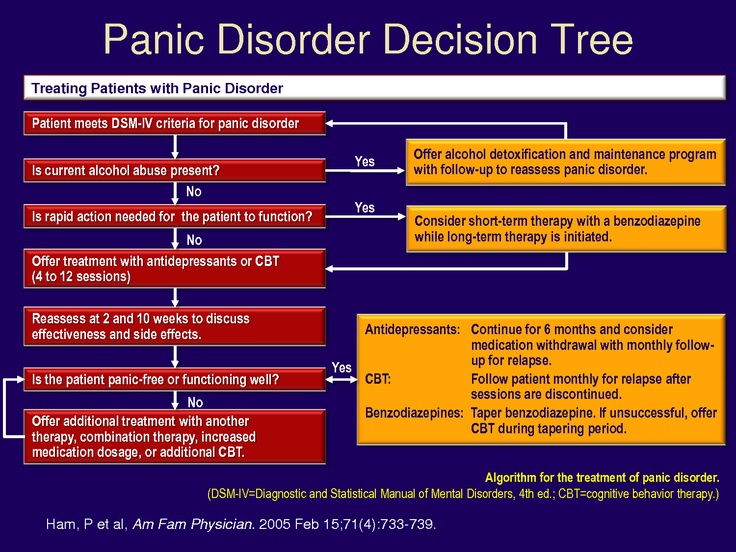

| Anxiety Disorders | Generalized anxiety disorder. Social anxiety disorder. Separation anxiety disorder. Panic disorder. Phobias. |

| Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders | Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Hoarding disorder. Body dysmorphic disorder. Skin-picking disorder and hair-pulling disorder. |

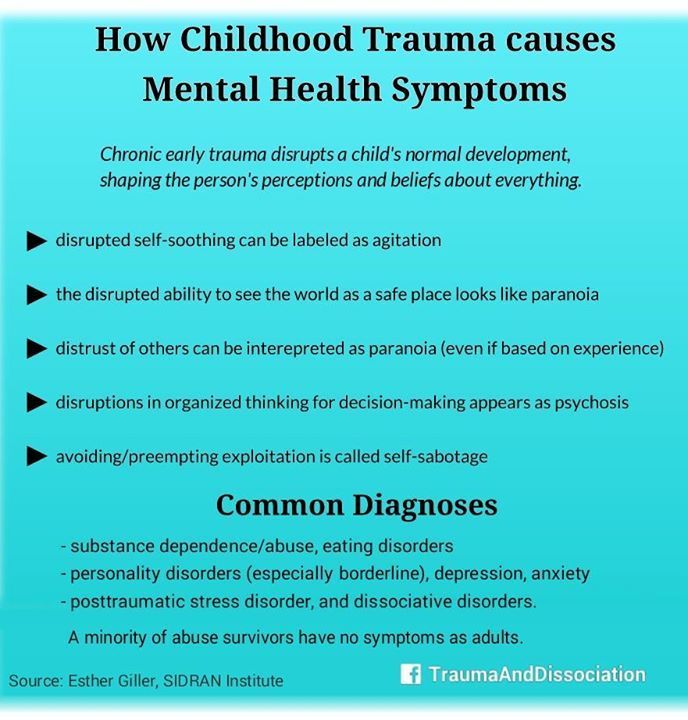

| Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders | Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Acute stress disorder.

Adjustment disorder. |

| Dissociative Disorders | Dissociative identity disorder. Dissociative amnesia. Depersonalization/derealization disorder. |

| Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders | Somatic symptom disorder. Illness anxiety disorder. Functional neurological symptom disorder (conversion disorder). |

| Feeding and Eating Disorders | Anorexia nervosa. Bulimia nervosa. Binge-eating disorder. Pica. |

| Elimination Disorders | Enuresis (a group of disorders that includes bedwetting). |

| Sleep-Wake Disorders | Insomnia disorder. Narcolepsy. Sleep apnea disorders. Nightmare disorder. Restless legs syndrome. |

| Sexual Dysfunctions | Sexual dysfunctions. |

| Gender Dysphoria | Gender dysphoria-related disorders. |

| Disruptive, Impulse-Control and Conduct Disorders | Oppositional defiant disorder. Antisocial personality disorder. Kleptomania. Pyromania. |

| Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders | Alcohol use disorder. Inhalant use disorder. Opioid use disorder. Withdrawal-related symptoms. |

| Neurocognitive Disorders | Delirium. Alzheimer’s disease. Parkinson’s disease. Huntington’s disease. Traumatic brain injury. |

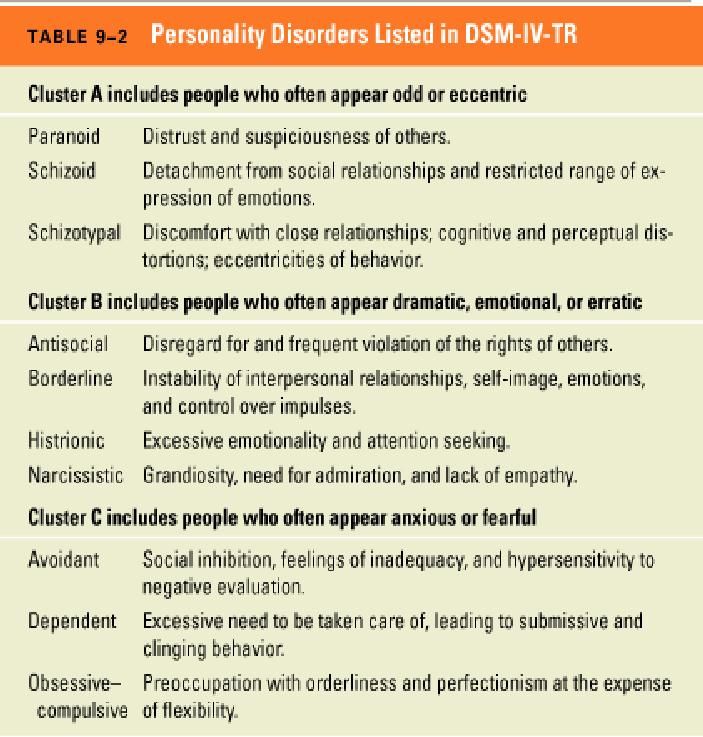

| Personality Disorders | Borderline personality disorder (BPD). Narcissistic personality disorder. |

| Paraphilic Disorders | Sexual behavior disorders. |

| Other Mental Disorders and Additional Codes | Conditions that don’t match the definition of another condition, but that still significantly affect someone’s life. |

| Medication-Induced Movement Disorders and Other Adverse Effects of Medication | Tardive dyskinesia. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. |

| Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention | These include circumstances or behaviors that aren’t conditions, but that may affect or happen in relation to diagnosable conditions. Examples include self-harm and suicidal behaviors, a history of any type of abuse, unemployment, etc. Examples include self-harm and suicidal behaviors, a history of any type of abuse, unemployment, etc. |

When will the APA publish the next edition of the DSM?

The APA doesn’t publish editions of the DSM on a regular schedule. Instead, they update the DSM as necessary. The APA published past editions of the DSM (which used Roman numerals before the fifth edition) in the following years:

- DSM-I®: 1952.

- DSM-II®: 1968.

- DSM-III®: 1980. The APA published a revised version, the DSM-III-R®, in 1987.

- DSM-IV®: 1994. The APA published a text revision version, the DSM-IV-TR®, in 2000.

- DSM-5: 2013. The APA published a text revision version, the DSM-5-TR, in 2022.

Is DSM-5 available to the public?

Yes. The DSM-5 is available for purchase in many bookstores and online stores. Many public libraries also have a copy (your local library may restrict this book to in-library use only, meaning you can’t check it out).

While the DSM-5 and DSM-5-TR are available to the public in multiple ways, it’s important to remember that the intended users of this book are medical professionals. As a result, the content in this book is extremely technical. That means the average person will probably find this book difficult to understand.

You shouldn’t use the DSM-5 or DSM-5-TR as a substitute for seeing a medical or mental health professional. It’s best to look at the DSM-5 and DSM-5-TR like you’d look at a book about how to fly a plane. You might find it interesting to read that book, but that’s no substitute for the formal education and training required to become a pilot.

Is DSM-5 still used?

Yes, but there are two variants of this book. The APA published the DSM-5 in 2013. In 2022, the APA published a text revision version, the DSM-5-TR. This text revision version includes updates and changes to the DSM-5 that reflect changes and updates in mental health practice since 2013. That makes the DSM-5-TR the preferred version, as it’s the most current and accurate version of this resource.

Among mental health providers, especially psychiatrists and psychologists, the DSM-5-TR is the most important resource for diagnosing mental health- and brain-related conditions. While it’s a publication of a United States-based organization, the DSM-5 is also an essential resource for providers worldwide, with translations into more than 18 languages available.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

The DSM-5 and its revised version, the DSM-5-TR, are key resource books for mental health professionals. This book is widely available for purchase, and many libraries may also make it available to their patrons. This book is intended for medical and mental health professionals, which is why it’s extremely detailed and very technical.

While the average person might find it interesting or informative, it’s not meant for casual use or self-diagnosis. If you think you or a loved one might have a condition defined in the DSM-5 or DSM-5-TR, you or your loved one should see a healthcare or mental health provider. Just like you wouldn’t perform surgery on yourself, it’s best to seek care from a trained, qualified mental health provider.

Just like you wouldn’t perform surgery on yourself, it’s best to seek care from a trained, qualified mental health provider.

DSM | Psychology Today

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a guidebook widely used by mental health professionals—especially those in the United States—in the diagnosis of many mental health conditions. The DSM is published by the American Psychiatric Association and has been revised multiple times since it was first introduced in 1952. The most recent edition is the fifth, or the DSM-5. It was published in 2013.

The DSM coexists with various alternative diagnostic tools, although these other guides are generally less commonly used in the U.S. The most widely consulted counterpart of the DSM, the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD), covers mental health disorders along with a vast number of other health conditions. The ICD is the primary diagnostic tool for mental health professionals outside the U.S.

The ICD is the primary diagnostic tool for mental health professionals outside the U.S.

Contents

- How the DSM Is Used

- How the DSM Has Changed Over Time

How the DSM Is Used

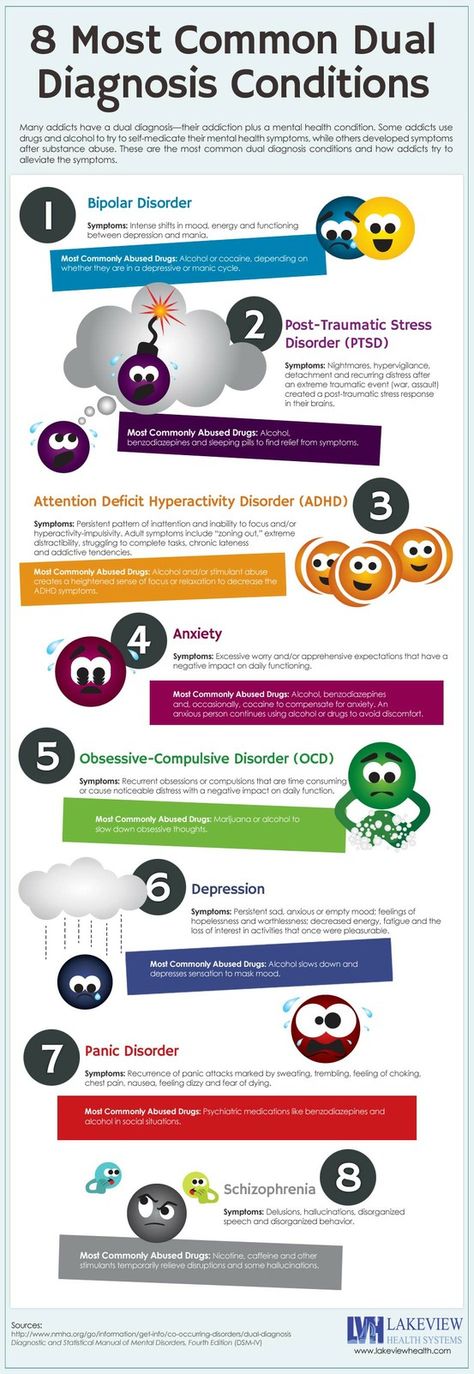

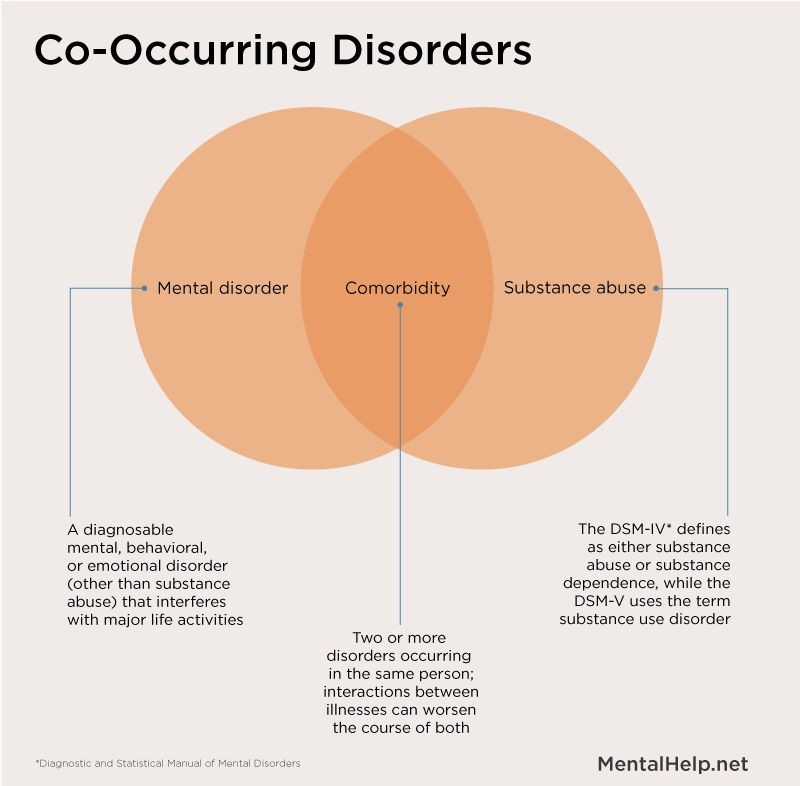

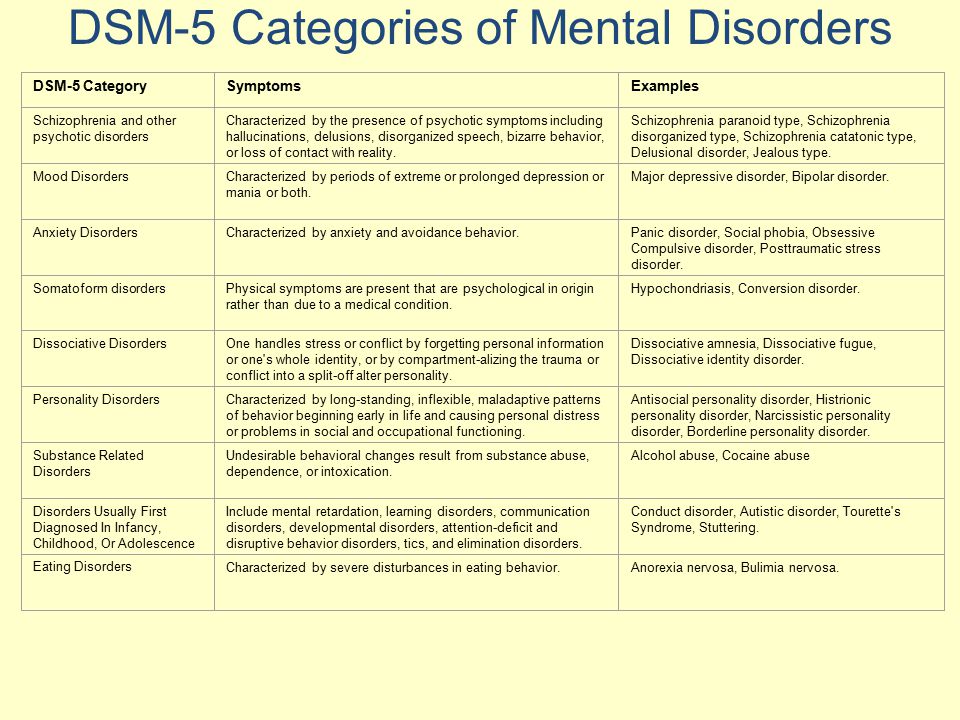

The DSM features descriptions of mental health conditions ranging from anxiety and mood disorders to substance-related and personality disorders, dividing them into categories such as major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder. These disorders are grouped into chapters based on shared features, e.g., Feeding and Eating Disorders; Depressive Disorders; Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders.

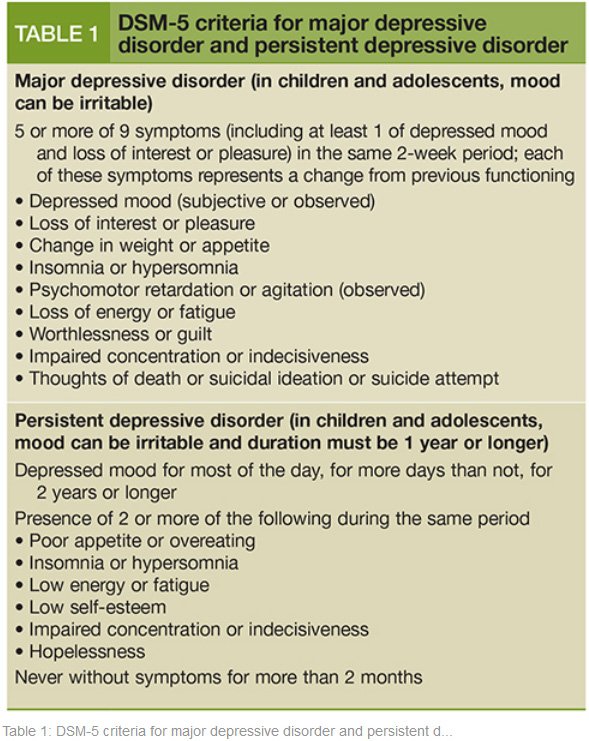

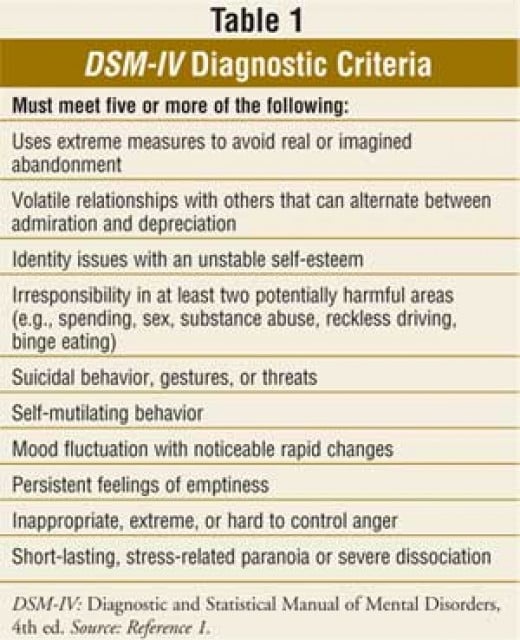

For each disorder category, the manual includes a set of diagnostic criteria—lists of symptoms and guidelines that psychiatrists, psychotherapists, and other health professionals use to determine whether a patient or client meets the criteria for one or more diagnostic categories. For diagnosis of major depressive disorder, for example, the current DSM states that a person shows at least five of a list of nine symptoms (including depressed mood, diminished pleasure, and others) within the same two-week period. It also requires that the symptoms cause “clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning,” along with other stipulations.

For diagnosis of major depressive disorder, for example, the current DSM states that a person shows at least five of a list of nine symptoms (including depressed mood, diminished pleasure, and others) within the same two-week period. It also requires that the symptoms cause “clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning,” along with other stipulations.

Updates to these diagnostic categories and criteria are made through a years-long research and revision process that involves groups of experts focusing on distinct areas of the manual.

What are the benefits of DSM?

The DSM is important for several reasons. First, it creates a common language to describe mental disorders; developing consistency is key because diagnoses are primarily based on symptoms and family history rather than more objective measures like blood tests or brain scans.

Second, diagnosis makes it possible to study treatments for mental illnesses. When people present to mental health services, professionals need to have some guide as to which treatments will best address particular collections of symptoms. Third, diagnosis facilitates research into the causes of mental disorders. If research in Peru links depression with poverty, a common concept of depression is necessary to investigate similar links in Canada.

When people present to mental health services, professionals need to have some guide as to which treatments will best address particular collections of symptoms. Third, diagnosis facilitates research into the causes of mental disorders. If research in Peru links depression with poverty, a common concept of depression is necessary to investigate similar links in Canada.

Is the DSM helpful for clinicians?

Diagnostic criteria help students and early-career professionals build templates of mental disorders that go beyond a layperson’s impressions—for instance that bipolar disorder describes abnormal moods sustained over weeks or months, not moods that shift over an hour or a day. The DSM establishes a common language for professional communication and research, not to mention insurance codes.

However, there are also ways in which mental health professionals don’t view the DSM as clinically useful. After seeing many patients, clinicians gradually form their own mental models of common diagnoses that might differ from the DSM, for example that the published criteria for a particular diagnosis is a little too wide or too narrow. In the end, clinicians may privilege the nosology of their own experience over the official manual that approximates it.

In the end, clinicians may privilege the nosology of their own experience over the official manual that approximates it.

Is the DSM helpful for researchers?

The criterion-based diagnoses listed in the DSM have improved consistency and reliability in classifying mental health conditions over time; clinicians around the world can now largely agree whether a particular patient “meets DSM criteria.” This shift in the DSM has been useful for research, in which the homogeneity of study groups is crucial.

What are some criticisms of the DSM?

Some believe that the failure to develop effective treatments for mental health disorders can in part be traced to a failure of classification, embodied by the long-standing reliance on the DSM. The DSM labels clusters of co-occurring symptoms and sorts them into disorder categories, but there is little evidence that these categories correspond to distinct biological realities. DSM categories may thereby hamper rather than facilitate psychology’s understanding of mental disorders.

DSM categories may thereby hamper rather than facilitate psychology’s understanding of mental disorders.

How the DSM Has Changed Over Time

The DSM has always been a lightning rod for debate about psychiatric diagnosis and classification. Since the 1950s, various categories of disorders have been added to the manual, altered, or removed altogether based on evolving clinical expertise and research and changes in the field of psychiatry, including a pivot away from psychoanalysis.

As the DSM is the dominant text for making mental health diagnoses in America, many of these changes are considered historically significant, such as when the DSM ceased to classify homosexuality as a form of mental illness in 1973. Other shifts have been controversial, including the omission of Asperger’s disorder from the DSM-5 in favor of a broader autism spectrum disorder category.

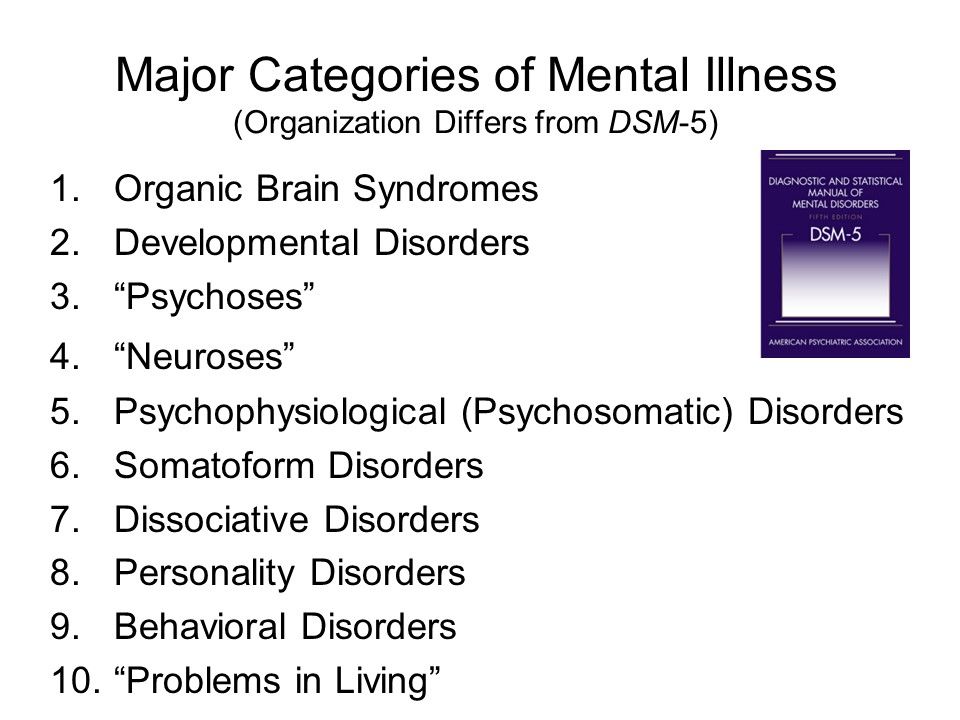

What are the current disorder categories in the DSM-5?

The DSM-5 organizes mental disorders into the following chapters: Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders, Bipolar and Related Disorders, Depressive Disorders, Anxiety Disorders, Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders, Dissociative Disorders, Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders, Feeding and Eating Disorders, Elimination Disorders, Sleep-Wake Disorders, Sexual Dysfunctions, Gender Dysphoria, Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders, Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders, Neurocognitive Disorders, Personality Disorders, Paraphilic Disorders, Other Mental Disorders, Medication-Induced Movement Disorders and Other Adverse Effects of Medication, and Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention.

What changes were incorporated into the DSM-5?

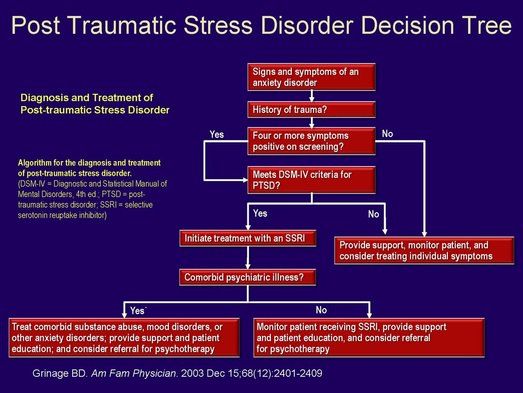

The DSM-5 departed from the previous version in several ways. A few of the key changes include:

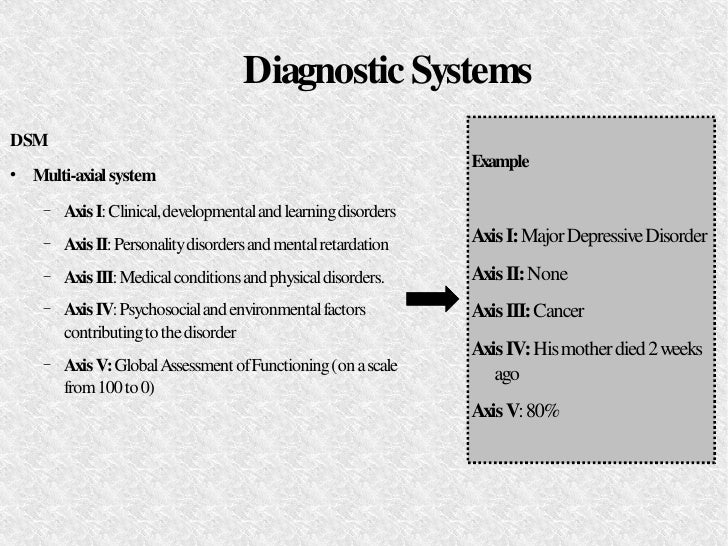

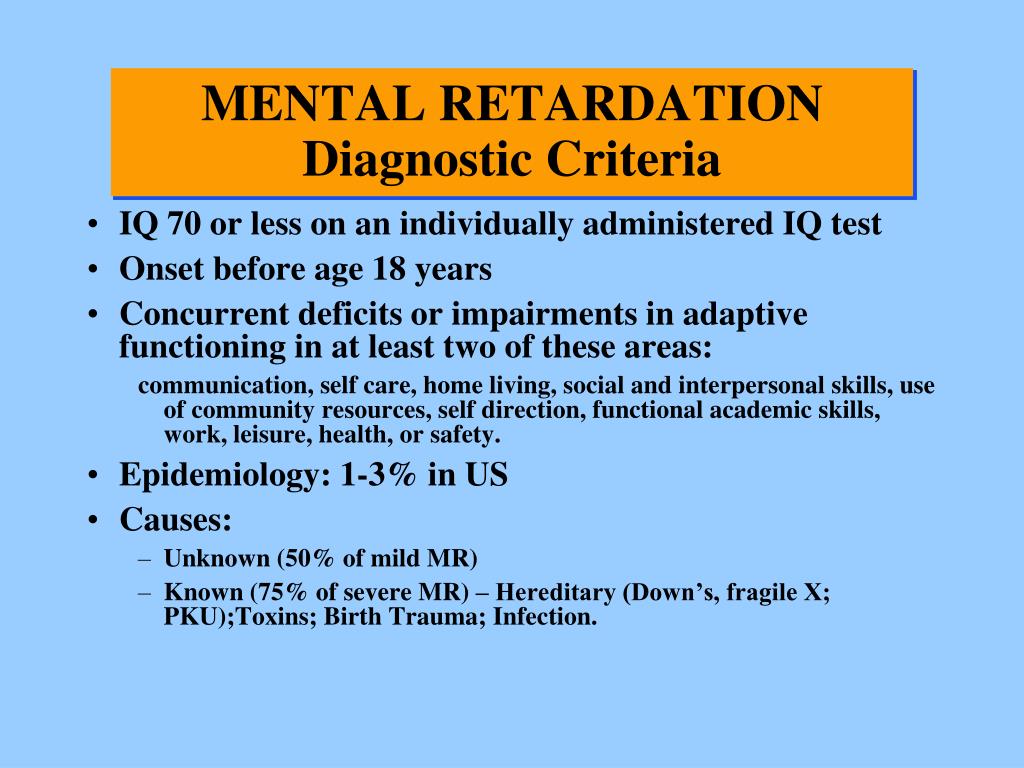

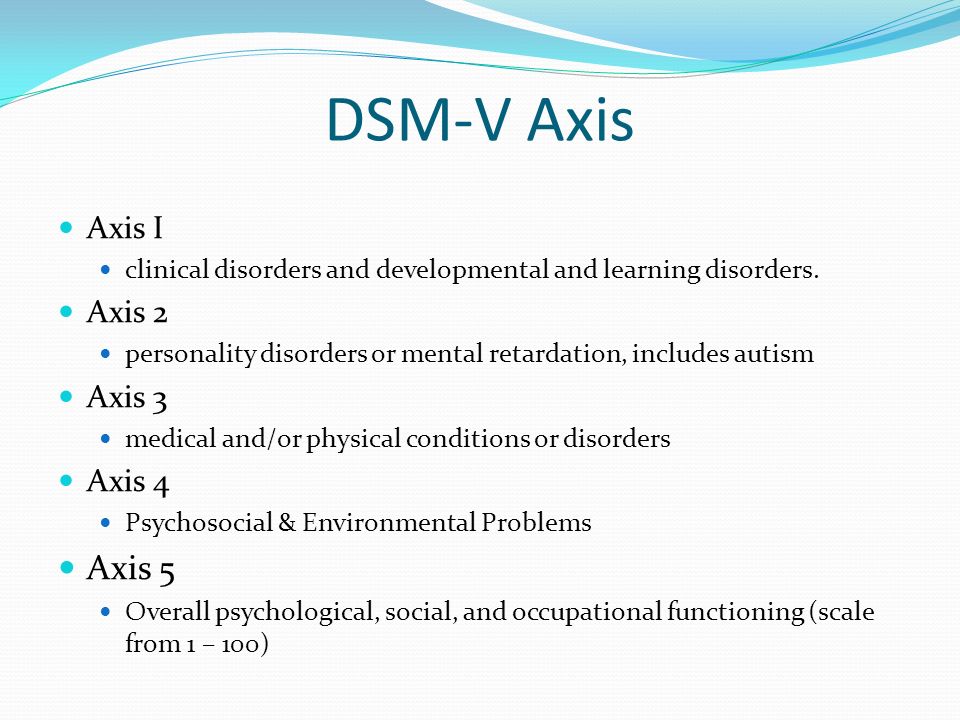

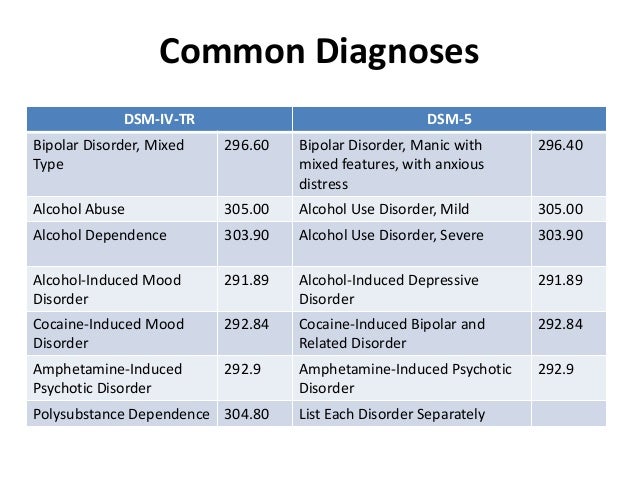

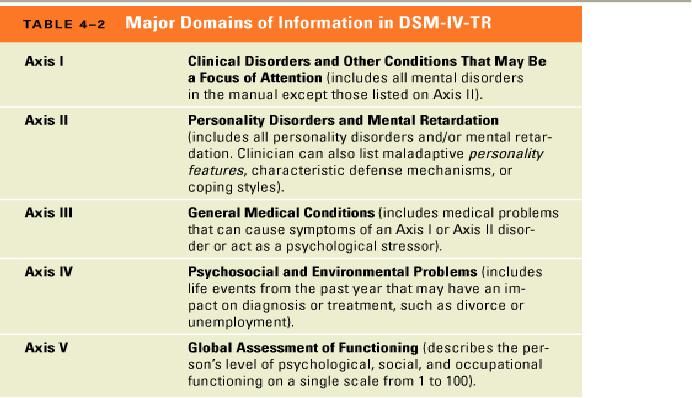

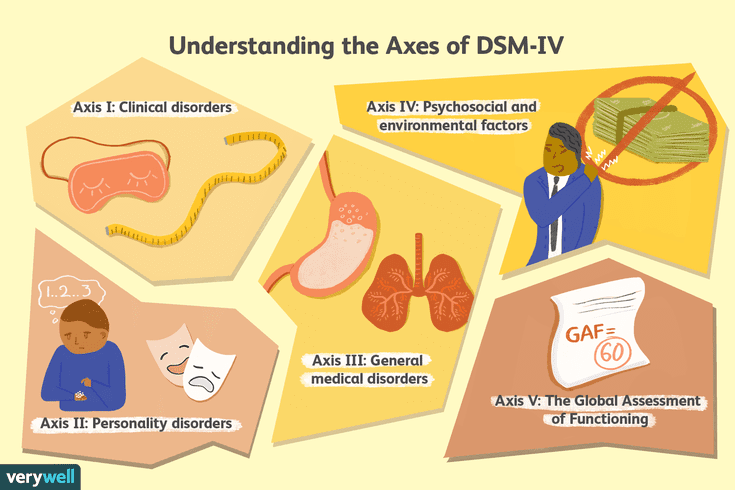

• Eliminating the multi-axial diagnostic system that required clinicians to rate each client according to criteria other than their main psychological disorder.

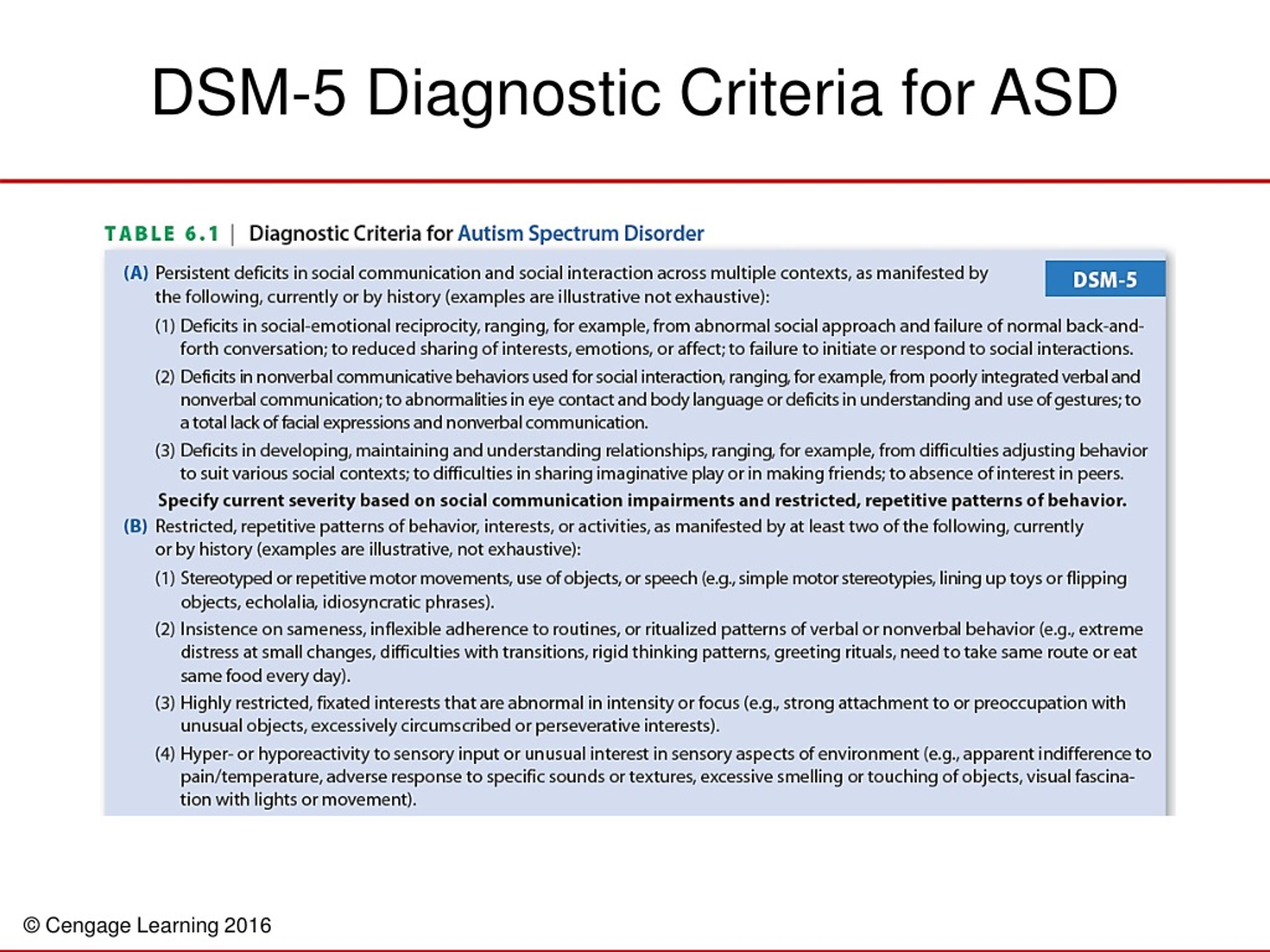

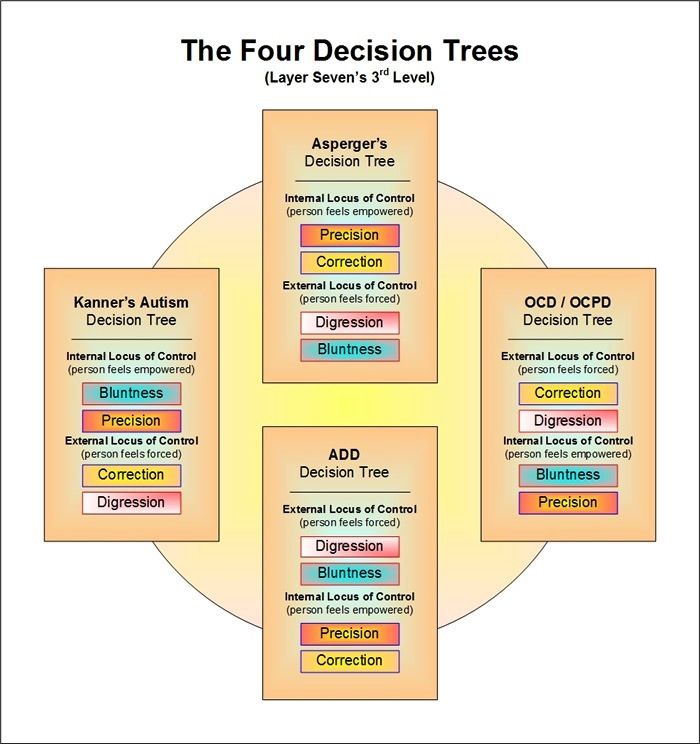

• Replacing the diagnoses “Autistic Disorder” and “Asperger’s Disorder” with the overarching label “Autism Spectrum Disorder.”

• Establishing “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders” as its own group of disorders rather than an anxiety disorder.

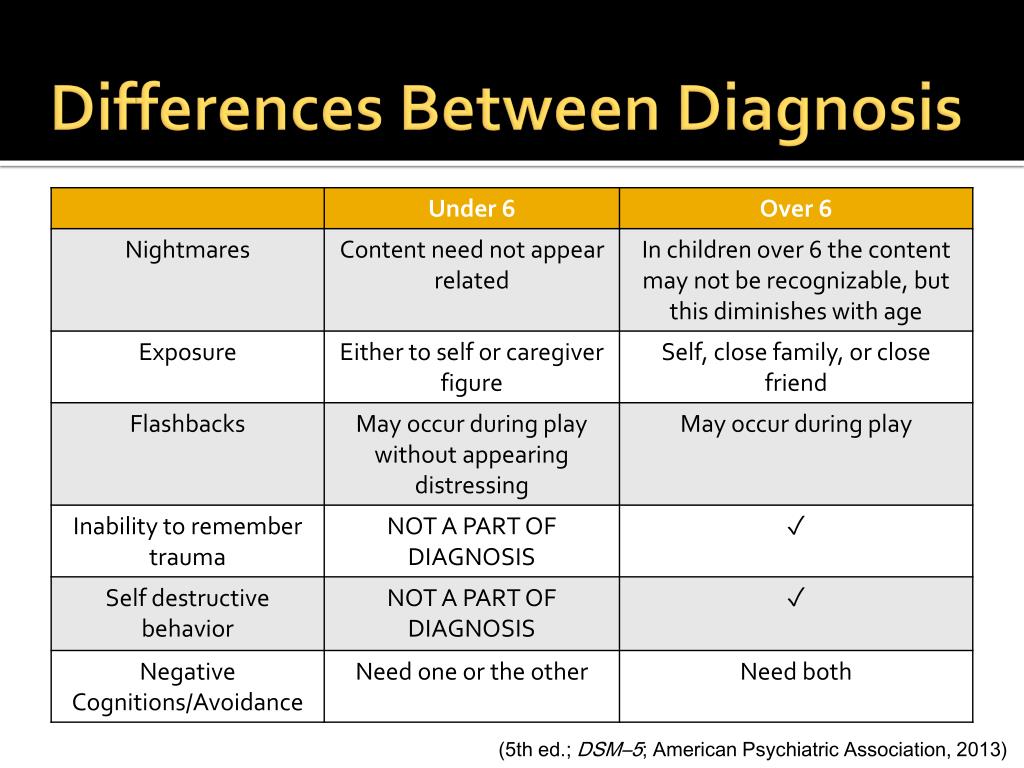

• Establishing PTSD as a “Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorder” rather than an anxiety disorder.

• Replacing the diagnoses "Alcohol Abuse" and "Alcohol Dependence" with the overarching label "Alcohol Use Disorder," characterized as mild, moderate, or severe based on the number of symptoms present. The same goes for other diagnoses related to addiction.

• Changing diagnoses with stigmatizing terminology, such as replacing the diagnosis “Mental Retardation” with “Intellectual Disability. ”

”

• Removing the exception of bereavement for the diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder.

• Adding the diagnosis “Mild Neurocognitive Impairment” to categorize cognition problems in old age.

• Reclassifying childhood disorders such as ADHD as neurodevelopmental disorders.

• Adding the diagnosis of “Binge-Eating Disorder.”

What are some criticisms of the changes made to the DSM-5?

Some psychiatrists believe that elements of the DSM-5 are deeply flawed. “Excessive ambition combined with disorganized execution led inevitably to many ill-conceived and risky proposals,” writes Allen Frances, chair of the DSM-IV Task Force and a professor emeritus at Duke, which could lead to misdiagnosis and overprescribing, especially for children.

The most concerning changes of the DSM-5, Frances believed, include incorporating grief into major depressive disorder, diagnosing typical forgetting in old age as Minor Neurocognitive Disorder, and introducing the concept of behavioral addictions.

Are there alternative diagnostic manuals to the DSM?

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD), published by the World Health Organization, is the best known and most popular alternative to the DSM. It contains diagnostic codes used for tracking incidence and prevalence rates, as well as for health insurance reimbursement, for mental and physical disease diagnoses.

Other alternatives to the DSM include the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual (PDM), Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP), Research Domain Criteria (RDoC), and Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF).

What is HiTOP?

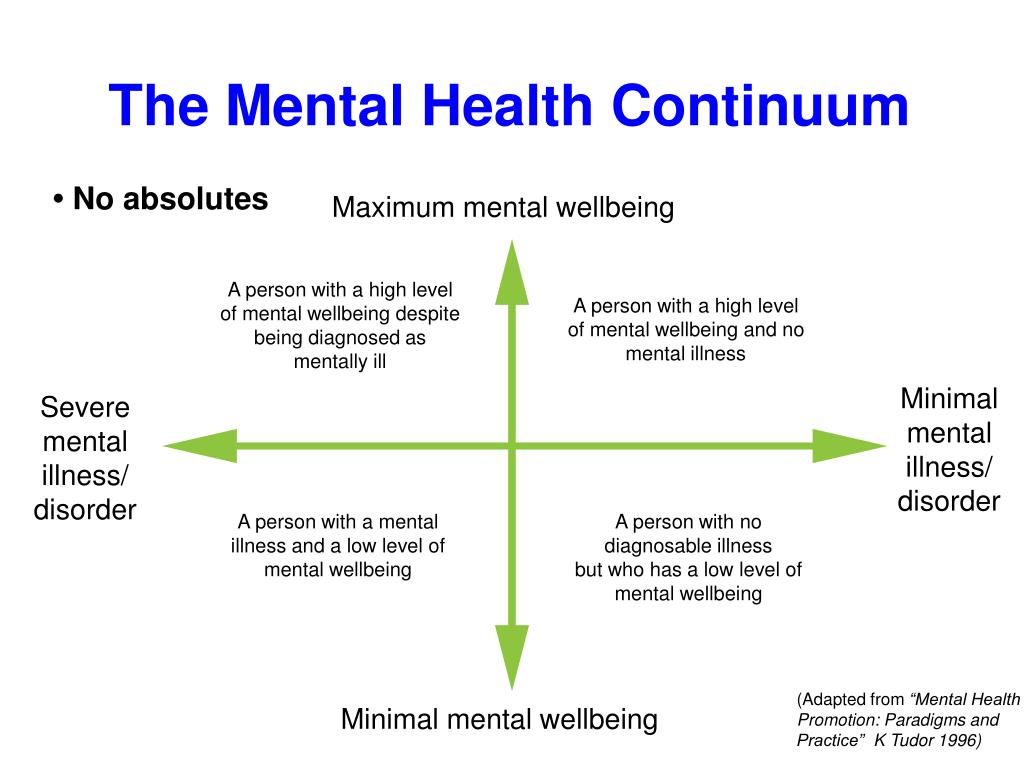

The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP)—accounts for mental illness at multiple conceptual levels. It covers specific symptoms (such as avoidance, social anxiety, and suicidality) and traits (callousness, distractibility), but also more general factors with names such as Distress and Fear. The DSM, by contrast, tends to be categorical and binary.

The DSM, by contrast, tends to be categorical and binary.

The HiTOP model is dimensional: A person can score low, high, or somewhere in between on various measures. These severity scores can apply to the more general factors of psychopathology as well as to the narrower ones. As proponents of the model note, evidence suggests that most kinds of psychopathology lie on a continuum with normality.

Essential Reads

Recent Posts

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

BASICS72

Share:Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a manual widely used by mental health professionals, especially in the United States, in diagnosing many mental health conditions .

The DSM is published by the American Psychiatric Association and has been revised many times since its first introduction in 1952 year. The most recent edition is the fifth, or DSM-5. It was published in 2013.

The DSM coexists with various alternative diagnostic tools, although these other manuals tend to be less commonly used in the US. The most commonly consulted counterpart to the DSM is the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD), which covers mental disorders along with a wide range of other diseases. The ICD is the primary diagnostic tool for mental health professionals outside the US.

How the DSM is used

The DSM provides descriptions of mental health conditions ranging from anxiety and mood disorders to substance-related disorders and personality disorders, categorized as major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and narcissistic disorder. personality disorder.

These disorders are grouped into chapters based on common features, eg feeding and eating disorders; depressive disorders; Spectrum of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

For each category of disorder, the manual includes a set of diagnostic criteria—lists of symptoms and guidelines that psychiatrists, psychotherapists, and other health professionals use to determine whether a patient or client meets the criteria for one or more of the diagnostic categories.

For example, for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, the current DSM states that a person has at least five of a list of nine symptoms (including depressed mood, decreased pleasure, and others) during the same two-week period.

It also requires the symptoms to cause "clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning", among other conditions.

Updates to these diagnostic categories and criteria are made through a multi-year study and revision process that involves expert groups focusing on specific areas of governance.

What are the benefits of DSM?

DSM is important for several reasons. First, it creates a common language for describing mental disorders; sequencing is key, as diagnoses are primarily based on symptoms and family history rather than more objective measures such as blood tests or brain scans.

Secondly, the diagnosis allows you to study the methods of treatment of mental illness.

When people come to mental health services, professionals should have some guidance on what treatments are best for specific sets of symptoms.

Thirdly, diagnosis makes it easier to investigate the causes of mental disorders. If studies in Russia link depression with poverty, then a general concept of depression is needed to study such links in Canada.

Is DSM useful for clinicians?

Diagnostic criteria help students and aspiring professionals create patterns of mental disorders that go beyond the layman's impression—for example, bipolar disorder describes an abnormal mood that lasts for weeks or months rather than a mood that changes over the course of an hour or a day.

DSM establishes a common language for professional communication and research, not to mention insurance codes.

However, there are also reasons why mental health professionals do not find DSM clinically useful. By observing many patients, clinicians gradually form their own mental models of common diagnoses, which may differ from the DSM, such as that published criteria for a particular diagnosis are too broad or too narrow.

Ultimately, clinicians may prefer the nosology of their own experience to official guidance that approximates it.

Is DSM useful for researchers?

Diagnoses based on criteria listed in the DSM have improved the consistency and reliability of the classification of mental health conditions over time; clinicians around the world can now basically agree on "whether a particular patient meets DSM criteria".

This shift in DSM has been useful for studies in which study group homogeneity is critical.

What are the criticisms of the DSM?

Some believe that the failure to develop effective treatments for mental disorders may be due in part to a misclassification embodied in long-standing dependence on the DSM.

The DSM labels clusters of associated symptoms and sorts them into disorder categories, but there is little evidence that these categories correspond to different biological realities. Thus, the categories of the DSM may hinder rather than facilitate psychology's understanding of mental disorders.

How the DSM has changed over time

The DSM has always been a lightning rod for debates about psychiatric diagnosis and classification. Since the 1950s, various categories of disorders have been added to the manual, changed, or removed entirely, depending on developments in clinical expertise and research, and developments in the field of psychiatry, including a move away from psychoanalysis.

Because the DSM is the primary text for mental health diagnoses in America, many of these changes are considered historically significant, such as when the DSM stopped classifying homosexuality as a form of mental illness in 1973 year.

Other changes have been controversial, including the removal of Asperger's syndrome from the DSM-5 in favor of a broader category of autism spectrum disorders.

What are the current DSM-5 disorder categories?

The DSM-5 classifies mental disorders into the following chapters:

- neurodevelopmental disorders,

- schizophrenia spectrum disorders and other psychotic disorders,

- bipolar and related disorders,

- Depressive disorders,

- Alarm Disorders,

- obsessive-compulsive and related disorders,

- Disorders associated with injury and stress,

- Dislocations

- Somatic symptoms and related disorders,

- extension.

eating disorders,

eating disorders, - Elimination disorders,

- Sleep and wake disorders,

- Sexual dysfunctions,

- Gender Diphoria,

- Destructive Disorders,

- Impulsion and behavior control disorders,

- Disorders related to the use of psychoactive substances and dependence,

- Neurocognitive disorders,

- of personality disorders,

- other mental disorders

- others

- Drug-induced movement disorders and other side effects of drugs, as well as other conditions that may be the focus of clinical attention.

Sergio Sergeiro / author of the article

I am a human relations researcher and have a lot of experience in this field. I hope my advice will help you cope with life and love difficulties.

Share:new tasks for clinical psychologists //Psychological newspaper

From January 1, 2022, the implementation of the 11th version of the International Classification of Diseases begins in WHO member countries, the transition to which in Russia will occur no earlier than 2025.

Pathopsychological diagnostics, closely associated with the names B.V. Zeigarnik and S.Ya. Rubinshtein , since the middle of the last century, has traditionally been included in the set of necessary examination methods in domestic psychiatric practice for solving, mainly, differential diagnostic and expert tasks [1; 2]. However, in recent years, unfortunately, more and more cues from practical specialists have begun to sound that the conclusions of clinical psychologists are of little demand for diagnostic purposes. This is due to the insufficient understanding of the conceptual apparatus of pathopsychology by doctors, and the lack of translational recommendations, i.e. indications of how exactly psychiatrists can use information from the conclusions based on the results of an experimental psychological examination.

In order to overcome the growing discrepancy in the qualifications of psychopathology and increase the clinical usefulness of pathopsychological diagnostics, it is advisable to help formulate the requests of clinicians and more clearly identify areas of intersection of the diagnostic approaches of doctors and psychologists. We can say that at this stage the task is to bring together the diagnostic positions of a doctor and a psychologist while maintaining the professional specificity of the approach to the analysis of mental disorders. To solve this problem, it is important for clinical psychologists to understand what modern psychiatric diagnostics is based on, how it can be correlated with the possibilities of experimental psychological research, and the very concepts of medical and psychological diagnosis, what psychological tools should be necessary and adequate in clinical practice.

We can say that at this stage the task is to bring together the diagnostic positions of a doctor and a psychologist while maintaining the professional specificity of the approach to the analysis of mental disorders. To solve this problem, it is important for clinical psychologists to understand what modern psychiatric diagnostics is based on, how it can be correlated with the possibilities of experimental psychological research, and the very concepts of medical and psychological diagnosis, what psychological tools should be necessary and adequate in clinical practice.

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is a statistical tool of the World Health Organization (WHO), which has been used for decades in the health care system around the world, providing unity of methodological approaches and comparability of data on morbidity and mortality. There is a strong tradition of revising the ICD to reflect the renewal of medical knowledge and scientific concepts. The 11th version of the ICD (ICD-11) was adopted at the WHO World Assembly on May 25, 2019with instructions to begin the gradual implementation of the new classification in WHO member countries from January 1, 2022. It is expected that this process may be delayed, because additional time will be required not only to restructure the system of coding of disease states and phenomena, but also to comprehend new approaches and put them into practice.

It is expected that this process may be delayed, because additional time will be required not only to restructure the system of coding of disease states and phenomena, but also to comprehend new approaches and put them into practice.

The chapter on mental and behavioral disorders has undergone significant changes, which is of paramount importance for the identification and qualification of mental health disorders. It should be noted that, unlike the American DSM classification, which is intended mainly for specialists in the field of psychiatry, the ICD, created for the needs of world health, focuses on interdisciplinarity and multiculturalism [4]. Therefore, the classification of mental disorders in the ICD can be used more widely and should be understood by representatives of other medical specialties, general practitioners, and even lay people, in particular, representatives of patient communities. In addition, it should take into account the specifics of manifestations depending on the cultural context, local customs and traditions. It was these conditions that we tried to take into account as much as possible when developing a new version.

It was these conditions that we tried to take into account as much as possible when developing a new version.

The review process, which began under the auspices of the WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse back in 2007, involved experts from around the world, including also clinical psychologists. Numerous opinion polls were conducted, discussions in working thematic groups, the latest data from evidence-based medicine and the results of field tests of diagnostic guidelines were taken into account, which took place on the Internet and at the clinical bases of several large psychiatric centers in different countries, including Russia [3]. The main task that was set in the development of the ICD-11 was to make it more clinically useful, as convenient and applicable as possible in practice, reflecting the current level of understanding of mental pathology. It was assumed that the changes introduced would contribute to greater detection of mental disorders, earlier recognition and more timely provision of the necessary assistance.

The changes affected the title and structure of the chapter, the expansion of diagnostic principles and the emergence of a number of new diagnostic categories [4]. In addition to mental and behavioral disorders, the title of the chapter now includes disorders of neuropsychic development. And this traces the through ontogenetic principle of diagnostics, implying the significance of the processes of individual development. Moreover, all disorders are considered at different age stages and it is assumed that they have their own specifics in childhood and adolescence, and this does not require them to be combined into a separate section, as was the case in ICD-10.

In addition to the categorical principle, traditional for psychiatric assessment, of assigning individual manifestations of psychopathology to one category or another, the dimensional principle is being actively introduced, i.e. measuring, principle , which allows to distinguish different variants of the disorder, taking into account the severity of violations. Basically, a three-stage gradation is used, distinguishing between mild, moderate and severe degrees of impairment in psychotic, affective, personality disorders, bodily distress, as well as intellectual development disorders that allow an even more pronounced degree - deep. The diagnostic guidelines contain descriptions of the clinical manifestations corresponding to each of the severity levels. However, they look quite general (with the use of the comparative words "rarely", "often", "less", "more") and largely depend on the subjective opinion of the evaluating physician. Perhaps clinical psychology could offer more rigorous, formalized criteria for assessing the severity of impairments.

Basically, a three-stage gradation is used, distinguishing between mild, moderate and severe degrees of impairment in psychotic, affective, personality disorders, bodily distress, as well as intellectual development disorders that allow an even more pronounced degree - deep. The diagnostic guidelines contain descriptions of the clinical manifestations corresponding to each of the severity levels. However, they look quite general (with the use of the comparative words "rarely", "often", "less", "more") and largely depend on the subjective opinion of the evaluating physician. Perhaps clinical psychology could offer more rigorous, formalized criteria for assessing the severity of impairments.

Festival

Maya Aleksandrovna Kulygina

February 2022

Lecture

Transition to ICD-11: main changes and implications for practical psychology

One of the key concepts for distinguishing between norm and pathology in the ICD-11 are distress and dysfunction due to this or that deviation [5]. Accordingly, one of the central tasks of pathopsychological diagnostics is to assess the level of subjective psychological well-being and functioning of the patient in various areas of life (family, study, work, socialization, hobbies, self-sufficiency and self-realization). In this regard, it will be necessary to actively introduce existing diagnostic tools and develop additional questionnaires and scales. Perhaps, the statement of a functional diagnosis, indicating not only the broken, but also the intact links, will also deserve more attention.

Accordingly, one of the central tasks of pathopsychological diagnostics is to assess the level of subjective psychological well-being and functioning of the patient in various areas of life (family, study, work, socialization, hobbies, self-sufficiency and self-realization). In this regard, it will be necessary to actively introduce existing diagnostic tools and develop additional questionnaires and scales. Perhaps, the statement of a functional diagnosis, indicating not only the broken, but also the intact links, will also deserve more attention.

Some obsolete terms and concepts were abandoned, such as neurosis, conversions, the concept of endogeneity-exogeneity, or the division into organic and inorganic disorders as not corresponding to ideas about the involvement of brain structures in all mental processes. The diagnosis of “mental retardation” has been replaced by “impaired intellectual development”, and this is not only for the purpose of destigmatization, but to indicate the psychological essence of the disorder.

The format and, accordingly, the content of clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines (CODEs), the diagnostic manual that is an appendix to the chapter on mental disorders, is also changing. Compared to a similar manual in the ICD-10, it becomes more structured, detailed, with the designation of the features of the course of the disorder, the boundaries with the norm, the detailed prescribing of the boundaries with other disorders with similar manifestations. Additionally, specific clinical features are highlighted for each disorder, taking into account age, cultural and gender differences.

Attention to cultural aspects sets the contextual approach and the assumption of the relativity of deviations , in connection with which it becomes necessary to qualify the disorder in the context of generally accepted cultural norms that exist in a particular community. For example, what in cultures with collectivist values will be perceived as a normal behavioral manifestation, in a Western culture with a predominance of individualistic values, can be interpreted in the opposite way, as a deviation from the norm, and vice versa. This concerns, in particular, such constructs as attachment-dependence or narcissism-self-actualization, and also has to do with the timing and severity of grief experiences. In addition, in a number of cultures, more often in Southeast Asia or South America, painful experiences can be designated in a completely different way as sensations of cold, heat, wind in different parts of the body. This requires more careful consideration of the patient's ethnicity and culture in the collection of anamnestic information and assessment of status.

This concerns, in particular, such constructs as attachment-dependence or narcissism-self-actualization, and also has to do with the timing and severity of grief experiences. In addition, in a number of cultures, more often in Southeast Asia or South America, painful experiences can be designated in a completely different way as sensations of cold, heat, wind in different parts of the body. This requires more careful consideration of the patient's ethnicity and culture in the collection of anamnestic information and assessment of status.

Even at the stage of development of the ICD-11, Russian psychiatrists had an ambiguous attitude towards the introduced changes [6]. Perhaps this is due to lack of awareness, because. the first Russian translation of the statistical classification, which contains codes and brief definitions, appeared only in the spring of 2021 [5], while the diagnostic instructions, which contain the main criteria for mental disorders and detailed explanations, are still in the final stage and are not yet available for general use. It is also impossible to exclude the influence of the general crisis in psychiatry associated with a gradual retreat from the phenomenological approaches of classical German psychopathology inherited by the Russian psychiatric school, which causes understandable dissatisfaction among adherents of the “old school” [6].

It is also impossible to exclude the influence of the general crisis in psychiatry associated with a gradual retreat from the phenomenological approaches of classical German psychopathology inherited by the Russian psychiatric school, which causes understandable dissatisfaction among adherents of the “old school” [6].

On the part of many domestic clinicians, reproaches are repeatedly heard for the psychologization of the new classification. However, this can rather be attributed to its merits, because. the potential of psychological interpretation of disorders of mental processes opens up more opportunities for understanding the essence of psychopathological phenomena and fully corresponds to the provisions of the biopsychosocial concept, about which psychiatrists themselves talk so much. Indeed, the logic of psychological reasoning can be traced, for example, in a consistent approach to assessing disorders and their representation in the cognitive, emotional and behavioral spheres, or in the principle of grouping disorders into separate monothematic groups, compiled on the basis of an essential clinical symptom that reflects the psychological mechanisms of emerging disorders. So, common to all anxiety and fear-related disorders is the focus of fear, i.e. those trigger experiences that cause anxiety, worry, and avoidance of frightening stimuli and situations. Such a focus of fear may be the fear of being judged by others in social anxiety disorder or the fear of separation from the object of attachment in separation anxiety disorder. Obsessive-compulsive disorders are combined on the basis of a pronounced cognitive component in the form of unwanted thoughts and persistent preoccupation, together with repetitive actions as a manifestation of the motor component. At the same time, the “degree of criticality” indicator is introduced as a clarifying feature, on the basis of which states of different severity are distinguished, depending on whether the criticism is satisfactory and preserved or reduced and absent.

So, common to all anxiety and fear-related disorders is the focus of fear, i.e. those trigger experiences that cause anxiety, worry, and avoidance of frightening stimuli and situations. Such a focus of fear may be the fear of being judged by others in social anxiety disorder or the fear of separation from the object of attachment in separation anxiety disorder. Obsessive-compulsive disorders are combined on the basis of a pronounced cognitive component in the form of unwanted thoughts and persistent preoccupation, together with repetitive actions as a manifestation of the motor component. At the same time, the “degree of criticality” indicator is introduced as a clarifying feature, on the basis of which states of different severity are distinguished, depending on whether the criticism is satisfactory and preserved or reduced and absent.

diagnosis of personality disorders in ICD-11 deserves special attention. The very understanding of personality pathology is changing dramatically. There is a departure from the identification of characterological typology as a predominant interpretation of personality disorders. Now, for the initial diagnosis, it is enough to establish the fact of the disorder and its severity, while the disorder itself is defined as a total and relatively stable pattern, on the one hand, of violations of self-functioning, essentially representing a triad of aspects of self-consciousness: the processes of self-perception, self-attitude and self-regulation, and on the other , — violations of social functioning. One can trace a recognizable similarity of these ideas with personality theory V.N. Myasishchev , in which a person is understood as a system of relations to oneself, the world and others [7]. At the same time, the specificity of personality manifestations can also be taken into account at the secondary optional stage, which includes the diagnosis of personality traits presented in the five leading domains: negative emotionality, detachment, dissociality, disinhibition, anancaste.

There is a departure from the identification of characterological typology as a predominant interpretation of personality disorders. Now, for the initial diagnosis, it is enough to establish the fact of the disorder and its severity, while the disorder itself is defined as a total and relatively stable pattern, on the one hand, of violations of self-functioning, essentially representing a triad of aspects of self-consciousness: the processes of self-perception, self-attitude and self-regulation, and on the other , — violations of social functioning. One can trace a recognizable similarity of these ideas with personality theory V.N. Myasishchev , in which a person is understood as a system of relations to oneself, the world and others [7]. At the same time, the specificity of personality manifestations can also be taken into account at the secondary optional stage, which includes the diagnosis of personality traits presented in the five leading domains: negative emotionality, detachment, dissociality, disinhibition, anancaste. At the same time, each individual may have different combinations and the severity of the listed features, which determines the personal identity in each individual case, while in the presence of a personality disorder, we are talking, in essence, about decompensation, which leads to a violation of social adaptation, but may be and transient, i.e. not necessarily lifelong, as was previously believed when making a diagnosis of a personality disorder.

At the same time, each individual may have different combinations and the severity of the listed features, which determines the personal identity in each individual case, while in the presence of a personality disorder, we are talking, in essence, about decompensation, which leads to a violation of social adaptation, but may be and transient, i.e. not necessarily lifelong, as was previously believed when making a diagnosis of a personality disorder.

Against the background of the innovations of ICD-11, the classification of pathopsychological syndromes adopted in domestic practice with the allocation of separate registers (schizophrenic, affective-endogenous, oligophrenic, exogenous-organic, endogenous-organic, personality-abnormal, psychogenic-psychotic, psychogenic-neurotic) [8] looks outdated and not corresponding to modern ideas about the systematics of mental disorders. In this connection, the task is to revise the concept of "pathopsychological syndrome" and its varieties with the identification of predominant disorders in the cognitive, emotional, motivational and behavioral clusters in accordance with the key clinical signs of mental disorders. Among other disorders, one can single out the increased interest of psychiatrists in assessing the safety of executive cognitive functions, social intelligence, and emotional regulation disorders.

Among other disorders, one can single out the increased interest of psychiatrists in assessing the safety of executive cognitive functions, social intelligence, and emotional regulation disorders.

Obviously, against the background of ongoing changes in the concept and interpretation of mental disorders, a pathopsychological diagnosis should be associated with a psychiatric one, understandable for the doctor, be a rationale for verifying the patient's condition and an addition to understanding the mechanisms of psychopathology. This also applies to the list of questions that can be answered by an experimental psychological examination and the selection of the necessary and sufficient tools and the very structure of the pathopsychological conclusion. Consequently, one of the urgent tasks for clinical psychologists is the most careful appeal to the explanatory and experimental potential of domestic pathopsychology in order to increase its clinical usefulness and applicability in psychiatric practice.

- Zeigarnik B.V. Pathopsychology. Ed. 2nd, revised and expanded. Moscow: Moscow University Press, 1986. 287 p.

- Rubinshtein S.Ya. Experimental methods of pathopsychology. M.: EKSMO-Press, 1999. 448 p.

- Kulygina M.A., Krasnov V.N. On conducting field trials of a new version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health-Related Problems // Russian Psychiatric Journal. 2018. №3. pp. 4-9.

- Reed G. M., First M. B., Kogan C. S., Hyman S. E., Gureje O., et al. Innovations and changes in the ICD-11 classification of mental, behavioral and neurodevelopmental disorders // World Psychiatry. 2019. 18(1), 3-19.

- ICD-11. Chapter 06. Mental and behavioral disorders and disorders of neuropsychic development. Statistical classification. M.: KDU, Universitetskaya kniga, 2021. 432 p.

- Kulygina M.A., Syunyakov T.S., Fedotov I.A., Kostyuk G.P. Toward ICD-11 Implementation: Attitudes and Expectations of the Russian Psychiatric Community // Consortium Psychiatricum.