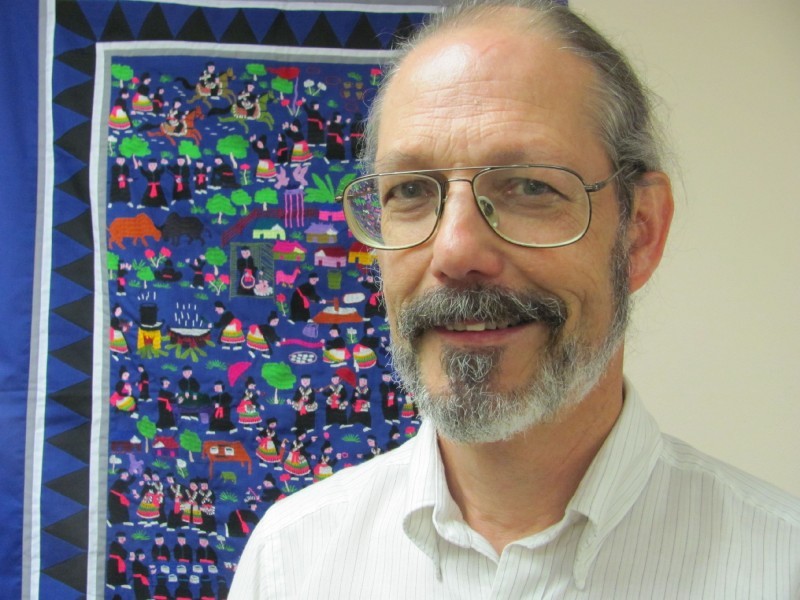

Dr fred goodwin

Frederick K. Goodwin, M.D. | Brain & Behavior Research Foundation

BBRF Awards & Recognition

Scientific Council Member Emeritus (Joined 1987)

Title & Institution

Clinical Professor of Psychiatry

Director, Center on Neuroscience, Medical Progress, and Society

George Washington University Medical Center

BBRF Awards & Recognition

Scientific Council Member Emeritus (Joined 1987)

Bio

Dr. Goodwin’s research focuses on bipolar disorder, major depression and suicide. As a Founding Partner of Best Practice, a consulting firm providing expertise to pharmaceutical and biotech companies and managed care organizations worldwide, Dr. Goodwin led a study showing that lithium was significantly more effective than other widely-used mood stabilizers protecting against suicide among 26,000 bipolar I patients.

He served from 1981 to 1988 as NIMH Scientific Director and Chief of Intramural Research, and prior to that held a Presidential appointment as head of the Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration.

Dr. Goodwin is a graduate of Georgetown University and received his M.D. from St. Louis University. He is the author of over 460 publications, and together with K.R. Jamison, Ph.D., wrote “Manic-Depressive Illness,” the first psychiatric text to win the Best Medical Book award from the Association of American Publishers.

Learn More About the Foundation

Who

We Are

The Brain & Behavior Research Foundation is a global nonprofit organization focused on improving the understanding, prevention and treatment of psychiatric and mental illnesses.

Read more

Our

Impact

Beginning in 1987, the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation was providing seed money to neuroscientists to invest in “out of the box” research that the government and other sources were unwilling to fund. Today, Brain & Behavior Research Foundation is still the leading, private philanthropy in the world in this space.

Today, Brain & Behavior Research Foundation is still the leading, private philanthropy in the world in this space.

Read more

Our

People

Meet the people who make up the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. Our staff of experts, passionate Board of Directors, and Scientific Council which includes Nobel prize winners and chairs of psychiatric departments around the world.

Read More

Annual Report

& Financials

We take our responsibility to our donors seriously and believe that our financial operations must be transparent. We're proud to say that 100% of your contribution for research is invested directly in research grants.

Read more

FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions about the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation.

Read more

Media

Center

The latest news on brain and behavior research and issues that matter most to you.

Read more

Donate Now

Donations are welcome

Amount

N/A

$35

$100

$250

$500

Enter your amount

In Memory of Frederick Goodwin

A few months ago, the prominent psychiatrist Frederick Goodwin died. The externals are known by many, and described in my formal memoriam: He was a former director of the National Institute of Mental Health, a well-known researcher in mood disorders, first author of the most prominent textbook in mood disorders (Manic-Depressive Illness), a prominent mentor at NIMH of generations of psychiatric leaders, and a leading psychiatrist in Washington, D.C., influential in government circles.

The externals are known by many, and described in my formal memoriam: He was a former director of the National Institute of Mental Health, a well-known researcher in mood disorders, first author of the most prominent textbook in mood disorders (Manic-Depressive Illness), a prominent mentor at NIMH of generations of psychiatric leaders, and a leading psychiatrist in Washington, D.C., influential in government circles.

I’d like to write about him here more personally, giving insights about who he was, and reflecting on some things we should learn from his life example.

There was no one closer to me as a mentor and teacher than Fred Goodwin. And there was no one more different than me. I was Iranian, Shiite, a Democrat, an immigrant. He was a Roman Catholic, conservative, Republican, whose ancestor was on that boat with George Washington crossing the Delaware.

And yet, he was so impressive. Not just for what he did, but for how he came back from setbacks to triumph again, over and over again. In one of our last dinners, sitting in a swank Washington restaurant, tears came to his eyes: “We’ve been through a lot together,” he said, looking over at me. He wasn’t one to tear. I remember when his longtime NIMH secretary Harriet wanted to tell him that she had to leave him at the university to return to NIMH; she described to me how Fred didn’t want to face it. Fred attracted wonderful support from others, like his longtime secretary Harriet and his beloved wife of many years, Rosemary. When Rosemary, died, Fred realized how much she had done for him for so long, paying bills, shielding him from everyday life, so he could go on focused laser-like on science and research. Marriage had been so good to him, he told me, he wanted to do it again.

In one of our last dinners, sitting in a swank Washington restaurant, tears came to his eyes: “We’ve been through a lot together,” he said, looking over at me. He wasn’t one to tear. I remember when his longtime NIMH secretary Harriet wanted to tell him that she had to leave him at the university to return to NIMH; she described to me how Fred didn’t want to face it. Fred attracted wonderful support from others, like his longtime secretary Harriet and his beloved wife of many years, Rosemary. When Rosemary, died, Fred realized how much she had done for him for so long, paying bills, shielding him from everyday life, so he could go on focused laser-like on science and research. Marriage had been so good to him, he told me, he wanted to do it again.

Fred was a father-substitute for me, an American father who could speak to the American part of me. He loved America instinctively; I had to learn to love it consciously and painfully, despite not loving much that it did. He stood for an Americanness that I could respect and admire. We were an odd couple: the tall, very white, American; the shorter, darker, Iranian. And yet he took me in and accepted me. We bonded on being Washington, D.C. area natives, on the Redskins football team, on politics, and on local restaurants.

We were an odd couple: the tall, very white, American; the shorter, darker, Iranian. And yet he took me in and accepted me. We bonded on being Washington, D.C. area natives, on the Redskins football team, on politics, and on local restaurants.

In my first visit to his office, back in the late 1990s, I was awed by the pictures with the Pope and the presidents; the classic Washington, D.C. power office. But there he was, taking me seriously, this serious man of science. Later he would thank me for bringing him back to the world of research and the psychiatric profession, after his departure from the NIMH under some controversy led some to write him off.

That was the first crisis, the controversy that led to his removal from a high position in government. He left the NIMH, where he had been director, and was given a faculty post at George Washington University. That’s when I visited him. I had good training and nothing else. He had a full career, now seemingly over. But it wasn’t over, and he helped me and I helped him, and together we got going.

I learned from that experience that the world often rejects a good man unjustly. But I also learned that the world’s rejection means much less than it may seem.

Two decades of work together followed, the first few years in person, and then after I moved, weekly by phone. We talked about everything, and anything, and eventually nothing.

Two decades passed, and he recovered his role as a psychiatric leader. He had long treated the powerful of Washington: senators, and news celebrities, and power brokers. I covered for him for a while clinically, when he traveled, and was too impressed by his patients to serve them well. But he served the important and the non-important equally well, and often warned me about the danger of providing poor clinical care to the famous by treating them differently. He could do it; I am not confident I ever learned that skill.

My first international paid speaking event was in his place, in Uruguay. Many more would follow, but he always had me as his back-up if needed, a role I took with gratitude when younger, with pride when older. I’d still back him up if I could.

I’d still back him up if I could.

Years later, we’d both be invited independently by some of our joint colleague-friends, such as the group in Italy that had yearly conferences in Rome. I got to see Fred feted all over the world, and I appreciated it like a proud child.

What I loved most about him is that he never rejected anything that was true. In our scientific work, if something seemed true, he accepted it; if it turned out false, he dropped it. He had an utter honesty of mind that I rarely have seen. I never feared challenging an idea he held, nor feared his challenge of mine. I trusted he only cared to know the truth.

With this truth-devotion came a social tact that served him well. Most people liked him, even if he would disagree with their ideas. He had a huge circle of friends, and a smaller circle of devoted friends, who he got to know well when he was down.

Two decades after the NIMH matter came another crisis: He had established a great PBS radio show, the Infinite Mind, and after a decade it was pulled on the claim of undisclosed pharmaceutical relationships, which everyone knew and which he disclosed in his many lectures and papers. How it was undisclosed is unapparent to me.

How it was undisclosed is unapparent to me.

He went on for another decade writing, and speaking, and seeing patients. He loved seeing patients, much more than me. He was a doctor who loved doctoring. But patients don’t always return the love. Some legal matters toward the end of his working life were troublesome to him, and he finally closed his clinic.

We traveled together at national conferences; in the last one in Toronto a few years ago, he was in a large audience when I spoke about the core clinical issue we always discussed: the inefficacy of antidepressants in bipolar depression. That was the best presentation I’ve ever heard you give, he told me; you had it just right, in content and style. Perfect. I had peaked. I know he sat there in the audience like a proud father. He had passed the torch. Whether I could carry it was another matter.

Then he remarried, stopped seeing patients, and moved into a few years of silence. Parkinson’s disease progressed, and limited his mobility and stability. His mind was clear mostly, but it was harder and harder to function.

His mind was clear mostly, but it was harder and harder to function.

The last time I saw him, about a year ago, he looked at my newly published textbook on clinical psychopharmacology, dedicated to him, paged through it as I sat there, and said: “This is very philosophical; it brings out concepts and ideas that most people will appreciate.” He smiled. He was happy. I was happy. Years ago, another of my mentors, Gary Sachs, was introducing Fred for a talk in Boston. I was in the audience. Gary was praising the immense impact of Fred's textbook, and said that if Kraepelin had written the Old Testament, Goodwin had written the New Testament. Then he looked at me in the audience and remarked, maybe someday Nassir will write the Koran! As Fred looked approvingly at my textbook, that event surged up in my memory. Maybe I had finished my Koran.

When his wife died, he wrote and delivered her eulogy. I wasn’t there, but he later gave the written text to me, entitled “A eulogy for my wife. ” He quoted the French Catholic Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, who said, in his eulogy for his brother: “I can never lose one whom I have loved unto the end; one to whom my soul cleaves so firmly that it can never be separated does not go away but only goes before.”

” He quoted the French Catholic Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, who said, in his eulogy for his brother: “I can never lose one whom I have loved unto the end; one to whom my soul cleaves so firmly that it can never be separated does not go away but only goes before.”

In Fred’s Catholic belief, he has joined Rosemary. And he has left behind a life full of activity, and service, and joy to his many children and grandchildren, and his nonbiological children and grandchildren. He always said to me: “Nassir, a scientific generation is a decade.” He was three decades older than me biologically, but he was my scientific father, given how closely we worked together. He loves you like a son, his secretary Harriet told me back in the 1990s; I was embarrassed, but I realized he loved easily, as we all should, and he engendered love in return: “We’ve been through a lot together.”

He got to know my father well. They attended a congress or two together in D.C. I would be up there speaking, and my father, a neurologist, and Fred would be in the front row of the audience. They would talk to each other; my father would ask Fred to keep an eye on me, to not let me be too radical or too difficult with colleagues. Fred would hasten to agree. Keep your focus, Nassir, he would say when he came across a piece of poetry I wrote. Tone it down, he’d say, if I got hot in a symposium: Make a point without making an enemy.

They would talk to each other; my father would ask Fred to keep an eye on me, to not let me be too radical or too difficult with colleagues. Fred would hasten to agree. Keep your focus, Nassir, he would say when he came across a piece of poetry I wrote. Tone it down, he’d say, if I got hot in a symposium: Make a point without making an enemy.

I know he regretted that I moved away and was not with him in person enough in his last two decades. I regretted it too. There were the weekly phone calls and the frequent visits; but it wasn’t the same. He called it the Boston-Washington axis, and we visited each other a lot. But in the last few years, the calls ended. I knew he was there, but I couldn’t get to him. I was there for his wedding to his second wife, and I was happy to see him happy. And there were the occasional calls and visits afterwards, just like old times.

He left us. And we were left feeling like he felt when his wife died; or like St Bernard, who had something else to say that feels right: “We find rest in those we love, and we provide a resting place in ourselves for those who love us. ”

”

He was a resting place for his patients, his family, his many close friends, and for me. We rested for a long time. And now he rests.

Fred Goodwin - frwiki.wiki

Frederick (Dick) Anderson Goodwin (born 17 August 1958) is a Scottish banker and former CEO at the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS).

biography

In 2002, Forbes named Fred Goodwin Businessman of the Year. In 2004 he was knighted by the British government for "services rendered to the bank".

In November 2008, the Royal Bank of Scotland, which he had just left as president, went bankrupt. According to the Financial Services Authority (FSA), Fred Goodwin was partly responsible for this bankruptcy, making the decision in October 2007 to buy ABN AMRO at a high price when the financial crisis had already begun.

When he left the bank in October 2008, he was awarded an annual pension of almost £700,000 (almost €800,000). He refuses to give up, despite the scandal and record losses for the bank. Newsweek describes him as "the worst banker in the world".

Newsweek describes him as "the worst banker in the world".

In June 2009 he announced that he agreed to reduce his pension by £212,500.

His home in Edinburgh was vandalized in 2009 by a group of Bank Criminal Bosses.

He then lived in the south of France and was hired by a Scottish architecture firm in 2010 before retiring.

In January 2012, the confiscation commission stripped him of his title Sir . This very rare decision, according to the British government, is due to Fred Goodwin's role in the autumn 2008 banking and financial crisis.

An elected official, protected by parliamentary immunity, announced in 2011 that he would have an affair with a colleague. According to the "Scotsman" quoted by Les Echos, his wife then asks him to leave their house.

Notes and links

- ↑ a b c d e https://www.lesechos.fr/entreprises-sectors/finance-marches/actu/0202954179754-fred-goodwin-le-reprouve-595934.

php

php - ↑ https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/banksandfinance/8720696/Former-RBS-chief-Sir-Fred-Goodwin-threatened-staff-with-disciplinary-action-over-biscuit.html

- ↑ (o) "In London, forfeit star banker", France Info , 1 - th February 2012.

- ↑ (en) "Officers, the regulator and the British state are all to blame for the fall of the Royal Bank of Scotland", Le Monde , 12 December 2011

- ↑ (en) "Newsweek: Worst banker in the world?" ", Nouvel Observateur , December 5, 2008

- ↑ (in) "Sir Fred Goodwin has reduced his pension by £200,000 - but will still receive £342 £500 per annum", The Guardian , 18 June 2009

- ↑ (en) "The former head of the RBS bank is stripped of his title of nobility", Le Figaro , 1 - th February 2012.

ABN Amro changed owner and management – Kommersant Ukraine newspaper – Kommersant

1K 2 minutes. ...

ABN Amro and the consortium that bought it, led by the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), announced yesterday a personnel reshuffle at the Dutch bank. Representatives of RBS, the Spanish bank Santander and the Belgian-Dutch Fortis will occupy several key positions in it. The joint announcement by ABN Amro and a consortium of banks is the de facto announcement of the largest merger in the history of the global banking industry.

Yesterday, the Dutch bank ABN Amro and a consortium of European banks led by the British Royal Bank of Scotland officially announced appointments to the Supervisory Board and Board of Directors of ABN Amro. According to a joint statement, Artur Martinez, a representative of the Dutch bank, will remain at the head of ABN Amro's supervisory board. The remaining seats on the Supervisory Board will be occupied by the CEO of another member of the consortium, the Belgian-Dutch bank Fortis, Jean-Paul Vautron, the CEO of RBS, Fred Goodwin, and the chief executive of the third member of the consortium, the Spanish bank Santander, Juan Insiarte. The current members of the Supervisory Board of ABN Amro will be dismissed at the next extraordinary meeting of its shareholders, the date of which will be announced in the near future. The leadership of the Dutch bank intends to recommend to its shareholders to approve new candidates.

The new appointments at ABN Amro come immediately after the announcement on October 10 that Rijkman Greninck was stepping down as chairman of its board of directors, to be replaced by Mark Fischer, chief operating officer and RBS Group board member. At the same time, according to ABN Amro, the remaining members of the board of directors will remain in their posts. Greninck, 58, who worked at the bank for 33 years and took over the board of ABN Amro in 2000, sees his resignation as inevitable. "The shareholders have chosen the proposal of the consortium. That is why I should give way to my successor, who will be able to implement the plans of the consortium," says Mr. Greninck.

At the same time, according to ABN Amro, the remaining members of the board of directors will remain in their posts. Greninck, 58, who worked at the bank for 33 years and took over the board of ABN Amro in 2000, sees his resignation as inevitable. "The shareholders have chosen the proposal of the consortium. That is why I should give way to my successor, who will be able to implement the plans of the consortium," says Mr. Greninck.

Rijkman Greninck supported another bidder for ABN Amro, the third largest British bank Barclays, which was ready to pay 62 billion euros for ABN Amro. However, ABN Amro shareholders opted for a more generous offer from a consortium led by RBS, which offered €9bn more for the Dutch bank. Barclays promised not to split ABN Amro, founded 183 years ago, while the consortium immediately announced its intention to split the bank's operations. Barclays withdrew its offer last week, setting the outcome of a months-long battle over ABN Amro. The takeover of the largest bank in the Netherlands was the largest in the history of the global banking industry.