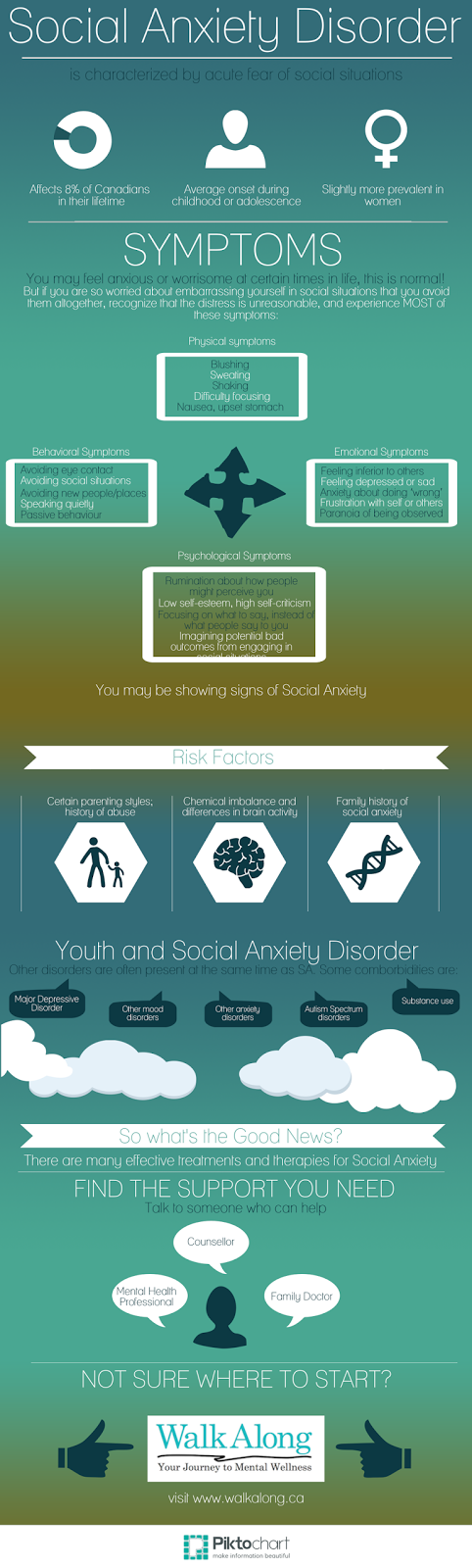

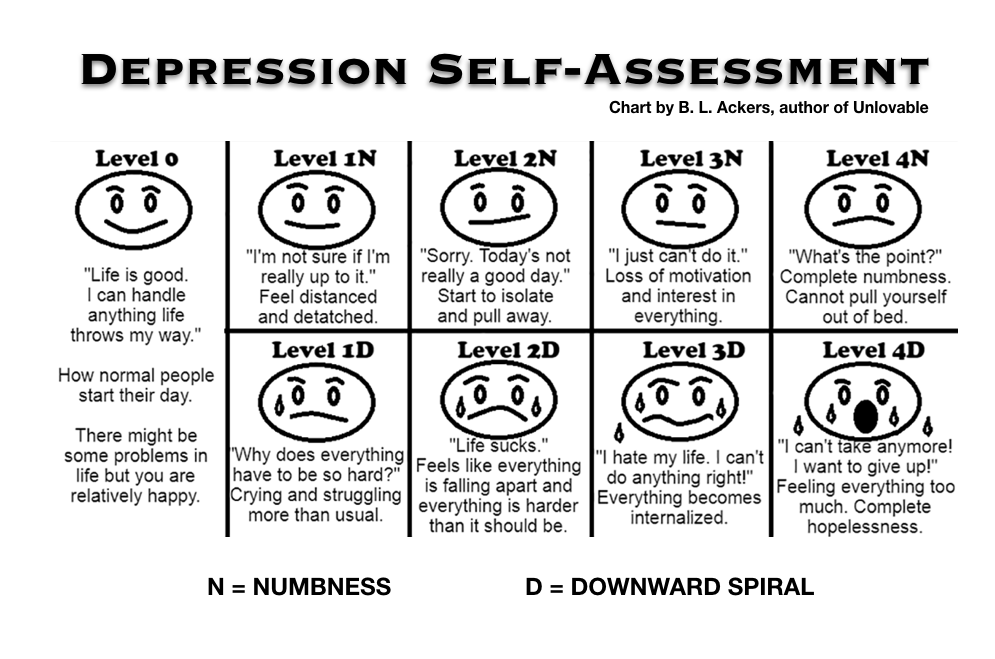

Depression negative self talk

Evidence-Based Resources About Opioid Overdose

SAMHSA’s Evidence-Based Practice Resource Center (EBPRC) contains a wide variety of downloadable resources available from SAMHSA and other federal partners about opioid overdose and other substance use and mental health topics to help communities, clinicians, policy-makers and others with the information and tools to incorporate evidence-based practices into their communities or clinical settings.

Fact Sheet:

Using Naloxone to Reverse Opioid Overdose in the Workplace: Information for Employers and Workers | CDC (PDF | 785 KB) - This fact sheet helps employers understand the risk of opioid overdose and provides guidance about establishing a workplace naloxone program.

Tips for Teens: The Truth About Opioids | SAMHSA - This fact sheet for teens provides facts about opioids. It describes short- and long-term effects and lists signs of opioid use. The fact sheet helps to dispel common myths about opioids.

Access sources cited in this fact sheet.

Toolkits:

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) for Opioid Use Disorder in Jails and Prisons: A Planning and Implementation Toolkit | National Council of Behavioral Health - Developed by the National Council of Behavioral Health, this guide provides correctional administrators and healthcare providers tools for implementing MAT in correctional settings.

Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit | SAMHSA -This toolkit offers strategies to health care providers, communities, and local governments for developing practices and policies to help prevent opioid-related overdoses and deaths. Access reports for community members, prescribers, patients and families, and those recovering from opioid overdose.

Evidence Reviews/Guidebooks:

Evidence-Based Strategies for Preventing Opioid Overdose: What’s Working in the United States | CDC (PDF | 11.5 MB) - This CDC document reviews evidence-based strategies to reduce overdose. It explains why these strategies work, the research behind them, and examples of organizations that have put these strategies into practice.

It explains why these strategies work, the research behind them, and examples of organizations that have put these strategies into practice.

Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment in Emergency Departments | SAMHSA - This guide examines emerging and best practices for initiating medication-assisted treatment (MAT) in emergency departments.

Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings | SAMHSA -This guide focuses on using medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder in jails and prisons and during the reentry process when justice-involved persons return to the community.

Telehealth for the Treatment of Serious Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders | SAMHSA - This guide reviews ways that telehealth modalities can be used to provide treatment for serious mental illness and substance use disorders including opioid overdose among adults.

Treatment Improvement Protocols/Manuals:

TIP 63: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder | SAMHSA - This Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) reviews the use of the three Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications used to treat OUD—methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine.

Advisory: Opioid Therapy in Patients With Chronic Noncancer Pain Who Are in Recovery From Substance Use Disorders | SAMHSA - This advisory addresses screening and assessment tools, nonpharmacologic and nonopioid treatment for chronic pain, and the role of opioid therapy in people with chronic noncancer pain and SUDs.

Overdose Prevention & Naloxone Manual | HRC - This Harm Reduction Coalition (HRC) manual outlines the process of developing an Overdose Prevention and Education Program that may involve a take-home naloxone component.

Websites:

SAMHSA

- Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)

- MAT Medications, Counseling, and Related Conditions

- Opioid Overdose

- Know the Risks of Using Drugs

Other federal websites

- HHS.gov/opioids

- Opioids | NIDA

- Drug Overdose | CDC

- Rx Awareness | CDC

Visit the EBPRC for additional information, including Treatment Improvement Protocols, toolkits, resource guides, clinical practice guidelines, and other science-based resources.

How To Stop Negative Self-Talk – Cleveland Clinic

Some days, we can be our own worst critics. It’s like there’s a constant commentator in your head nitpicking every single thing you do.

The truth is, negative self-talk happens to the best of us. But it becomes hard to shake off if you’re surrounding yourself with it consistently — and it can start to take a toll on your mental health and relationships.

Psychologist Lauren Alexander, PhD, explains what negative self-talk is and how to stop it in its tracks.

You may wonder how negative self-talk works. Is feeling down on yourself always harmful? Not necessarily.

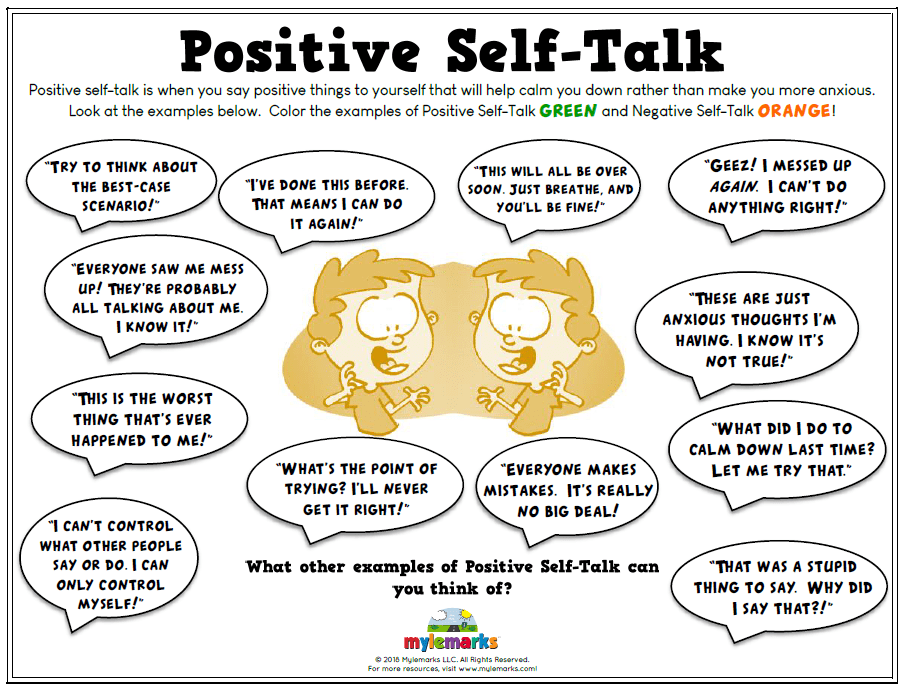

We’re all human. We all make mistakes. We all feel down or irritated with ourselves at times. The occasional “Oh, that was stupid of me” or “Why did I do that?!” in response to a mess-up isn’t uncommon.

“Everyone, at some point, has had some level of negative self-talk. Maybe they’ve called themselves a name or something like that,” says Dr. Alexander. “If that’s something you say to yourself occasionally, it’s not going to necessarily have a whole lot of impact on you. Harmful negative self-talk is when the dialogue in someone’s head is constantly negative, maybe more negative than it is positive.”

Alexander. “If that’s something you say to yourself occasionally, it’s not going to necessarily have a whole lot of impact on you. Harmful negative self-talk is when the dialogue in someone’s head is constantly negative, maybe more negative than it is positive.”

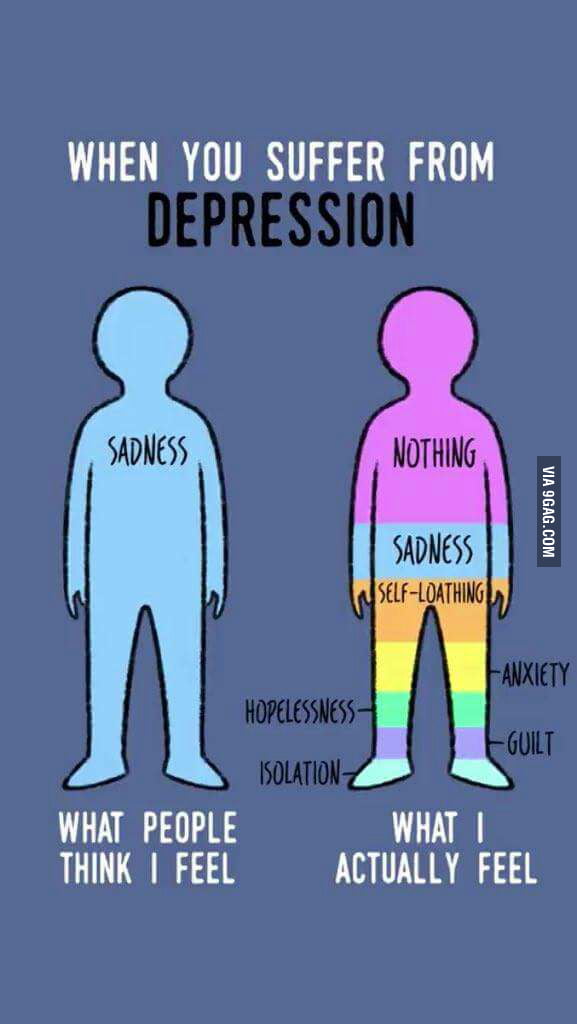

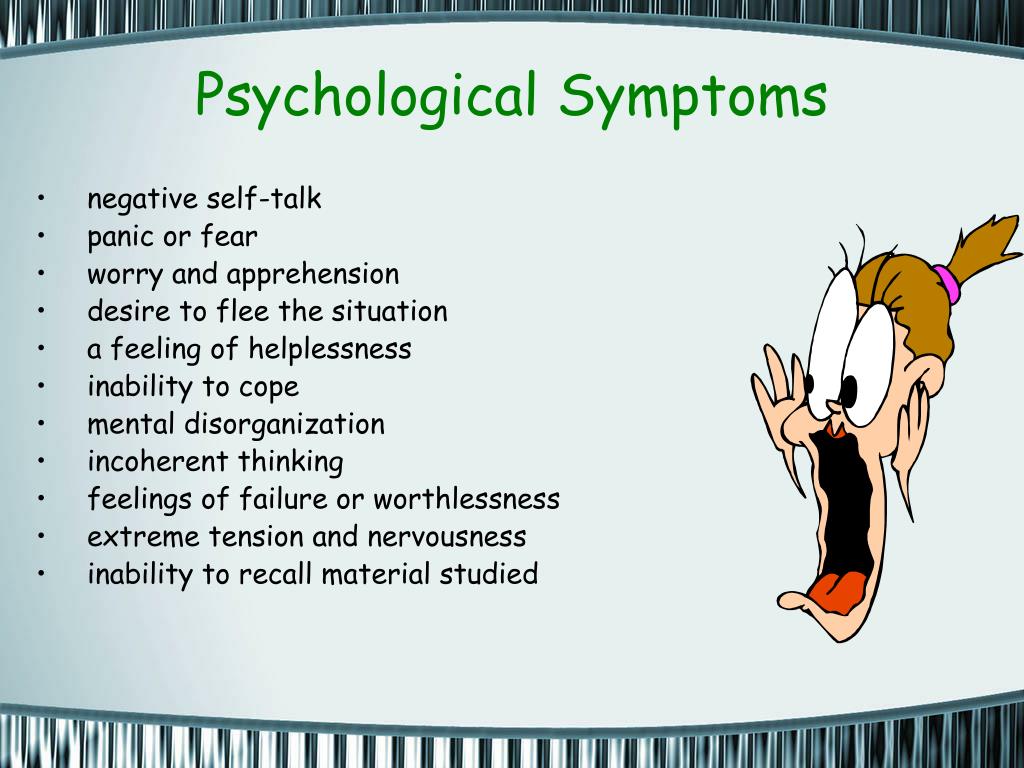

Negative self-talk is more than just feeling down on yourself. Sure, everyone feels a little defeated at times — it’s a natural part of life. Similarly, it’s also important to be self-aware and know when you make mistakes.

That’s why, Dr. Alexander points out, negative self-talk becomes harmful when it becomes the primary way you talk to yourself.

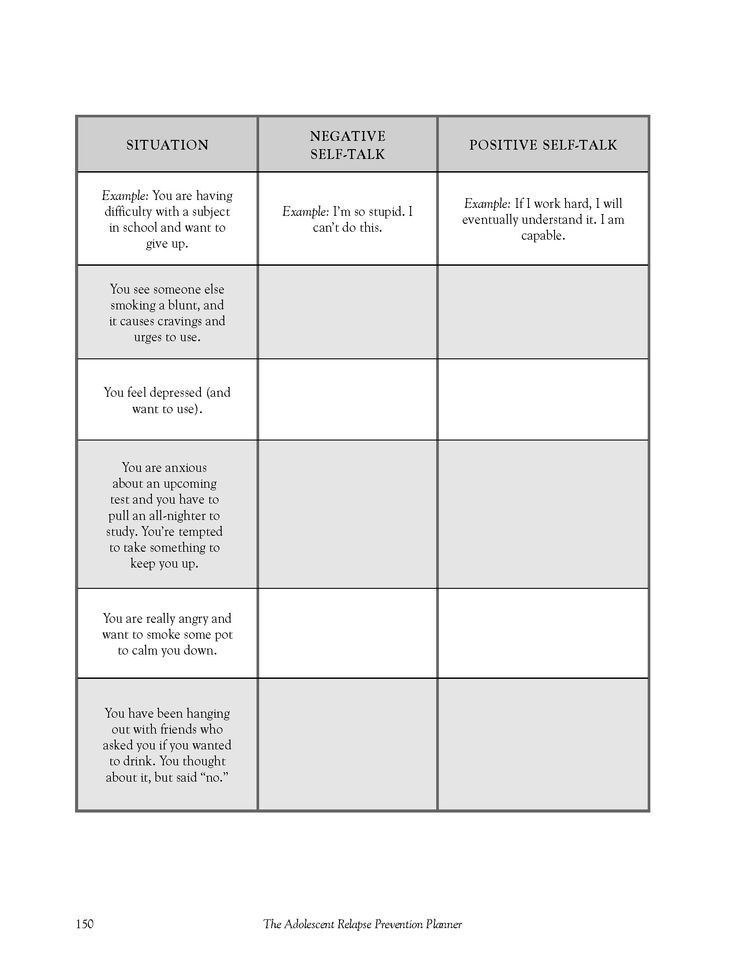

Some examples of negative self-talk include:

- “I can’t do anything right. I shouldn’t even try.”

- “Nobody likes me, I should stop trying to make friends.”

- “I don’t like anything about myself.”

- “I’m so dumb.”

If you find yourself engaging in this kind of inner conversation all of the time — whether that’s actually saying it out loud to the people around you or only in your mind — your negative self-talk may impact your mental well-being.

Advertising Policy

How negative self-talk can be harmfulThe way we speak to ourselves matters. It’s the story we tell ourselves about our lives, feelings and experiences. Pay attention if you’re bogging yourself down with negative thoughts and self-criticism and look for ways to change it (more on that in a bit).

Here are some very real ways that being stuck in a bad headspace can affect you:

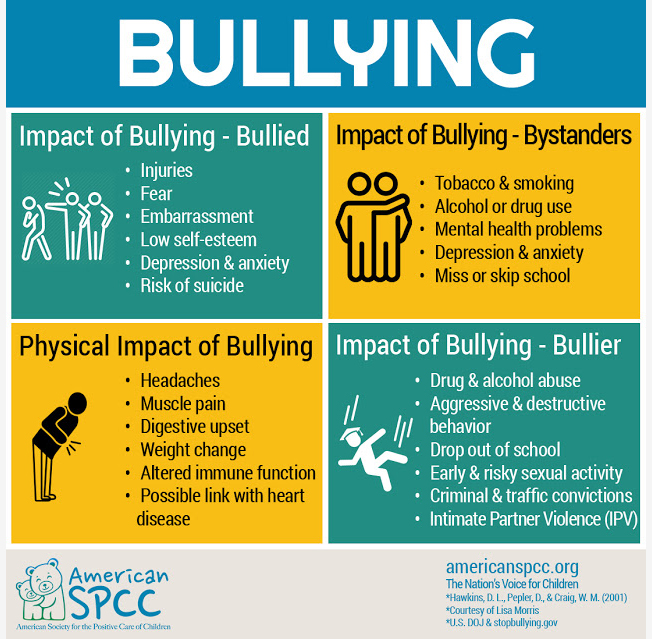

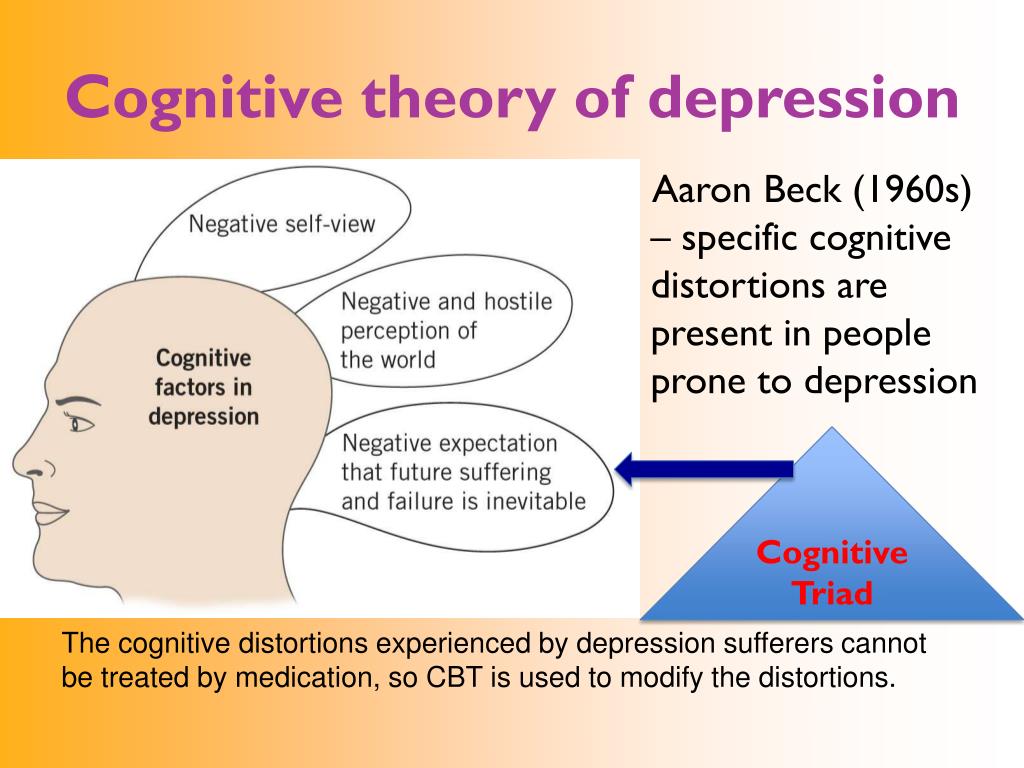

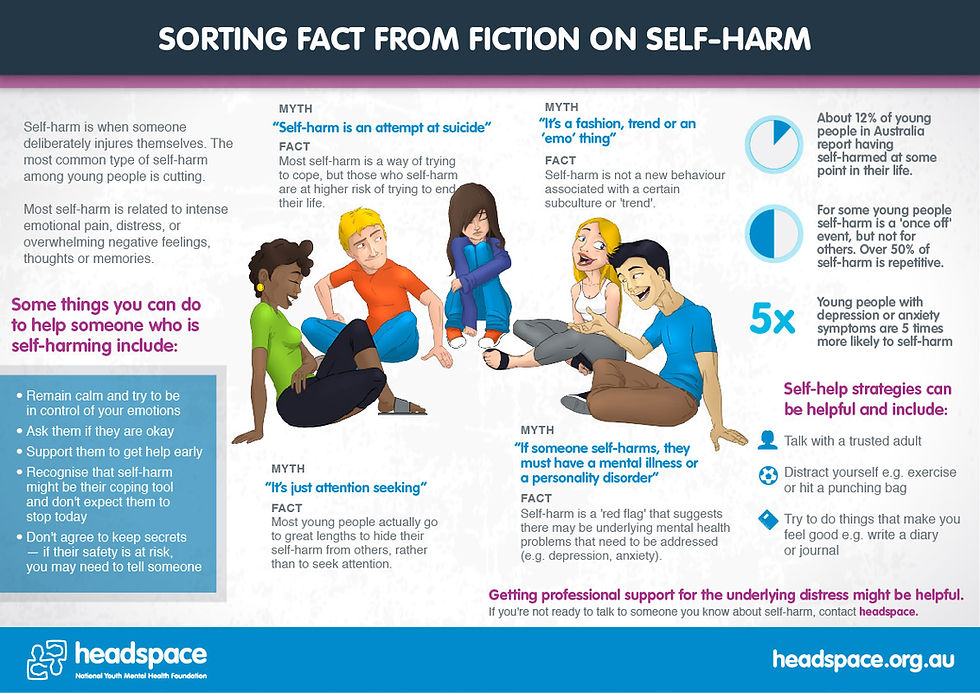

- It may worsen anxiety or depression. Negative self-talk can be the sneaky link that intensifies any depression or anxiety you’re having. If you’re going through certain mental hardships, the last thing your mind needs is constant criticism. Plus, it can cause you to shrink back from your support systems. “People engaging in harmful negative self-talk are much more likely to pull back and isolate themselves,” explains Dr. Alexander. This can become a big risk factor for depression and anxiety, even suicide.”

- It can harm your relationship with others.

While venting to your loved ones is important, negative self-talk can cause you to trauma dump on your friends and family. If the never-ending dialogue in your head and to others is negative, it can take a toll on your relationships. “It can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you share these thoughts with others, you may initially get reassurance. But after a certain point, people may push away from you,” notes Dr. Alexander.

While venting to your loved ones is important, negative self-talk can cause you to trauma dump on your friends and family. If the never-ending dialogue in your head and to others is negative, it can take a toll on your relationships. “It can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you share these thoughts with others, you may initially get reassurance. But after a certain point, people may push away from you,” notes Dr. Alexander. - It may hurt your self-esteem. You may develop low self-esteem from the overload of negative thoughts in your head. The more you beat yourself up over not doing things right, the less confidence you’ll have to try again. “You reap what you sow,” Dr. Alexander states. “If all that is in your mind is this negativity, of course it’s going to continue to affect your mood. So, you need to start practicing different ways of talking to yourself.”

Ask yourself: “Would I say these negative things about my closest friends?”

Probably not. So, you need to learn how to treat yourself with the same gentle care and respect as you do your loved ones.

So, you need to learn how to treat yourself with the same gentle care and respect as you do your loved ones.

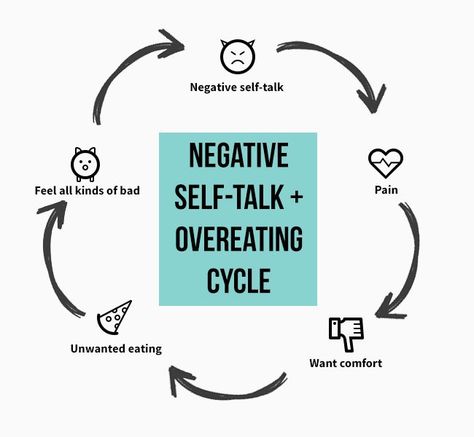

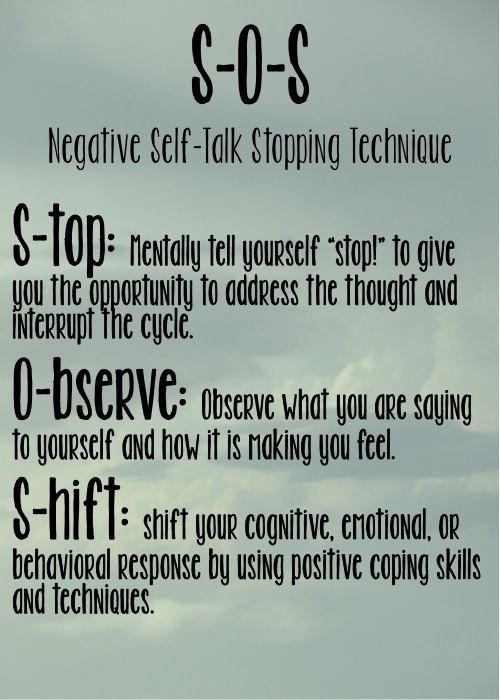

But how do you break the cycle of self-criticism? It can be a hard habit to break since the person you spend the most time with is yourself. But there are ways to break the cycle of negative thinking.

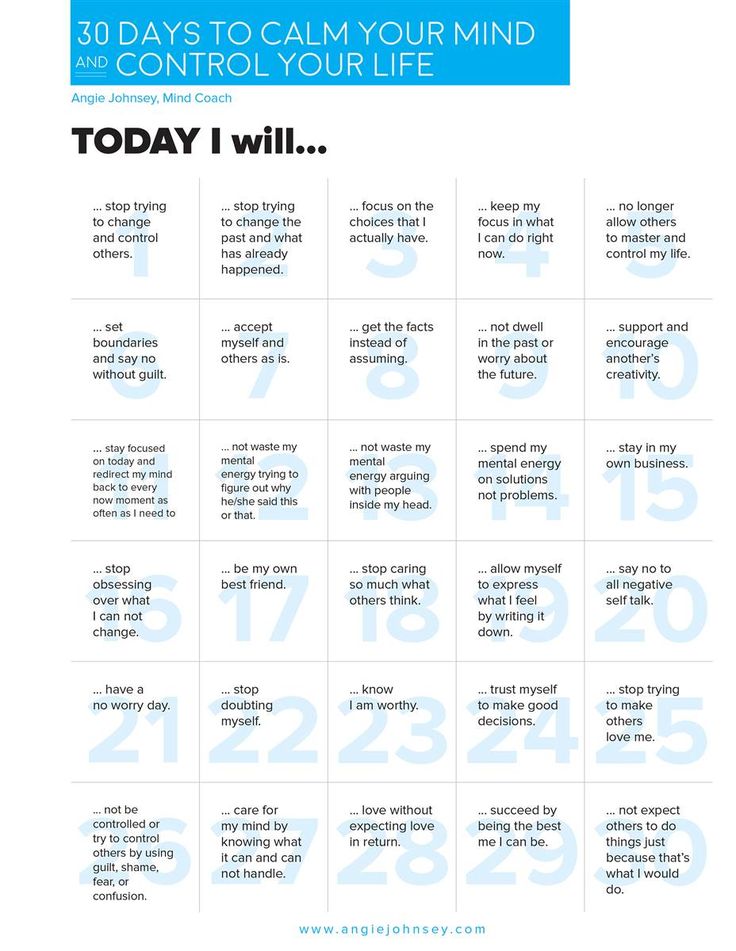

Here are some ways to cope with negative self-talk:

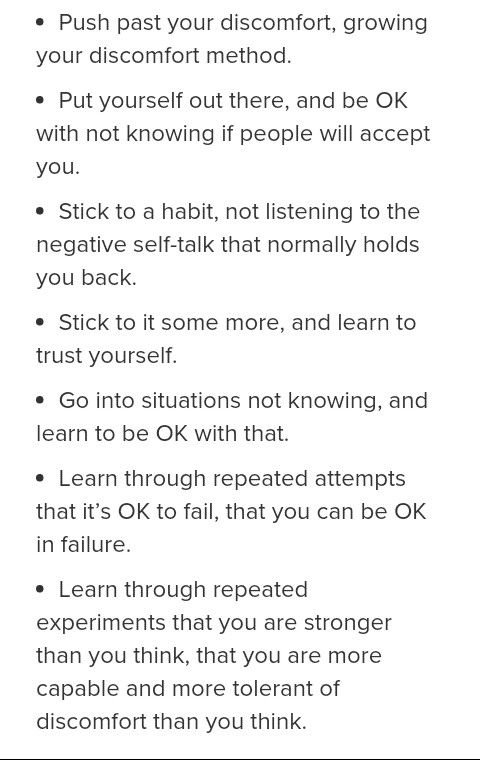

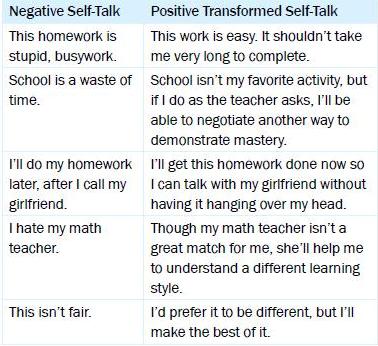

Try neutral thinkingYou may think that the perfect antidote to negative self-talk is positive self-talk. But that may be too big of a jump for some people. The truth is, the key to being kinder to yourself doesn’t necessarily need to be praising yourself — especially if it doesn’t feel sincere.

“It’s probably not going to feel very natural at first,” says Dr. Alexander. Instead, she recommends neutralizing your thoughts. Take them from being so extremely negative to a more realistic and balanced version of what you’re thinking.

She offers this example to show how our thoughts can be distorted:

Advertising Policy

| Negative emotional trigger | Negative thought | Realistic approach |

| Finding out you failed a test.  | “I failed this test. I can’t do anything right. I’m going to fail at everything. There’s no use in even trying.” | “It’s OK for me to be disappointed about failing the test. But I’m good at other things, and I can come up with some ways to prevent this in the future.” |

The key to doing this successfully? Dr. Alexander says it’s catching yourself in these thoughts and swatting them away like an annoying fly.

“Then, as you practice, you can start to transition into some more positive thinking. You can highlight some of your positive attributes, the things that you do right,” Dr. Alexander adds. “And then, starting to sow a different style of thinking, slowly but surely. It certainly takes time.”

Repeat, repeat, repeatThe best way to form healthy habits is through repetition. But habits won’t change overnight.

“That which is repeated over and over will eventually get ingrained in your mind,” reassures Dr. Alexander. “That’s how the negative thoughts got there in the first place. You’re repeating them over and over.” Instead, try repeating more balanced thoughts to replace the negative ones.

Alexander. “That’s how the negative thoughts got there in the first place. You’re repeating them over and over.” Instead, try repeating more balanced thoughts to replace the negative ones.

Writing down realistic or positive thoughts can also help them take hold. Anything that helps create a new narrative in your head can filter out the negative thoughts. Dr. Alexander recommends using thought cards — where you write the thoughts you want to have on a card and read them to yourself.

Don’t view negative self-talk as a motivatorWe all know the importance of self-discipline and staying humble. But you don’t have to be mean to yourself in the process. In fact, negative self-talk can be what holds you back from being more successful.

All of this to say, constant negative self-talk isn’t going to make you more self-aware or help you get things done faster or better. A comment to yourself here and there to “do better” or “get back on your feet” is one thing, but you can’t let it cross over into harmful territory.

“When we’re talking about someone who is just burdened, overloaded with negative self-talk, it does exactly the opposite,” explains Dr. Alexander. “It creates more negative emotions. They feel more uncomfortable.”

Being kind to yourself is sometimes easier said than done. Life can throw some punches at us that we may not expect, and we often go straight to blaming ourselves. While it’s normal to feel like this once in a while, a never-ending stream of negative thoughts towards yourself can become very toxic very fast. But the good news is, you can reword these thoughts through practice and self-assurance.

Why it's okay to talk to yourself and how this habit can make you more effective

Everyone does it: they do an internal monologue. It is part of the constant stream of consciousness that cannot be absent when we are awake. How to learn to talk to yourself correctly, our friends from the Reminder project tell.

“Okay, romantic moment, tell her something. Tell me how you crushed a pony. No, she likes ponies, I guess... Ask how long ago she had tests. What the hell is in my head? Lord, what a huge leg she has, tell her about it. No, don't talk, shut up! So, the pause dragged on, we must at least say something. Approximately such internal monologues were scrolled in the head by the protagonist of "Clinic", one of the most believable medical series.

Tell me how you crushed a pony. No, she likes ponies, I guess... Ask how long ago she had tests. What the hell is in my head? Lord, what a huge leg she has, tell her about it. No, don't talk, shut up! So, the pause dragged on, we must at least say something. Approximately such internal monologues were scrolled in the head by the protagonist of "Clinic", one of the most believable medical series.

Like him, many talk to themselves or hear an inner voice—when they are alone in a car, when they get bored in line, when they try to sleep, and so on. I sometimes talk to myself out loud - most often these are sarcastic comments if I did something ridiculous, or voicing what I should do, for example: "Now I'll do the dishes, and then I have to get dressed and go to the store." Sometimes all this makes you wonder: is it okay to talk to yourself if we invented speech to communicate with others?

It's embarrassing for many to admit it, but talking to yourself is completely normal and very common, says psychotherapist Laura Dabney. This is not something you “need to grow out of” and certainly not a sign of psychological problems. Moreover, psychiatrists call internal (or voiced) monologues a healthy practice. Firstly, they can be a way to get rid of negative emotions, such as fear, nervousness, anger or guilt. And secondly, they help organize thoughts, plan actions and consolidate memory.

This is not something you “need to grow out of” and certainly not a sign of psychological problems. Moreover, psychiatrists call internal (or voiced) monologues a healthy practice. Firstly, they can be a way to get rid of negative emotions, such as fear, nervousness, anger or guilt. And secondly, they help organize thoughts, plan actions and consolidate memory.

The “inner voice” has been studied since the beginning of psychology. The Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky made the observation that young children begin to talk to themselves at the same time that they learn to talk to others, and first they do it out loud and then to themselves. Such behavior - an internal monologue that sometimes breaks into speech - we retain for life.

Over the past few decades, we have learned that when talking to yourself, a person makes the smallest movements with the muscles of the larynx, and Broca's center is activated in the brain - the area responsible for the motor organization of speech. If the work of Broca's center is disturbed, the ability to conduct an internal monologue is also violated. That is, the same tools in the brain are used for internal conversation and articulated speech.

If the work of Broca's center is disturbed, the ability to conduct an internal monologue is also violated. That is, the same tools in the brain are used for internal conversation and articulated speech.

Another confirmation of this is the operation of the efferent copy mechanism. This is a signal that helps the body to distinguish the processes that we cause ourselves from external stimuli. A prime example is tickling: if we try to tickle ourselves, the brain “predicts” that the touch is due to our own movements, and the tickling sensation is extinguished.

The same signal operates when we talk to ourselves. Experiments have shown that the brain "mutes" the effect of other external sounds when we speak aloud.

Another interesting experiment found that the inner voice seems to help us to cope better with everyday tasks. Animals performing tasks to correlate two stimuli (the so-called matching tasks - tasks when the subject is shown an object and then asked to choose the same one from those in front of it) activate different parts of the brain depending on whether the stimulus was visual or auditory . We, humans, “turn on” several areas of the brain, regardless of the stimulus perception system.

We, humans, “turn on” several areas of the brain, regardless of the stimulus perception system.

But if a person is asked to mumble some meaningless word under his breath, for example, "blah blah blah" - and therefore deprive him of the opportunity to use his inner voice - he will behave (in a sense) as animal. That is, when performing tasks with visual or auditory stimuli, zones in his brain are activated that are responsible for either vision or hearing.

Interestingly, speaking thoughts out loud may have a different effect than speaking them silently. In one small experiment, psychologists at Bangor University in the UK asked one group of volunteers to read instructions for a task to themselves while another group read aloud. Those who read the instructions aloud performed better than the participants who sat in silence.

This is why it is not surprising that many people use self-talk to get things done. For example, this is what athletes do (very often tennis players), who, at critical moments, cheer themselves up with motivating (“Come on, you can!”) Or instructing phrases.

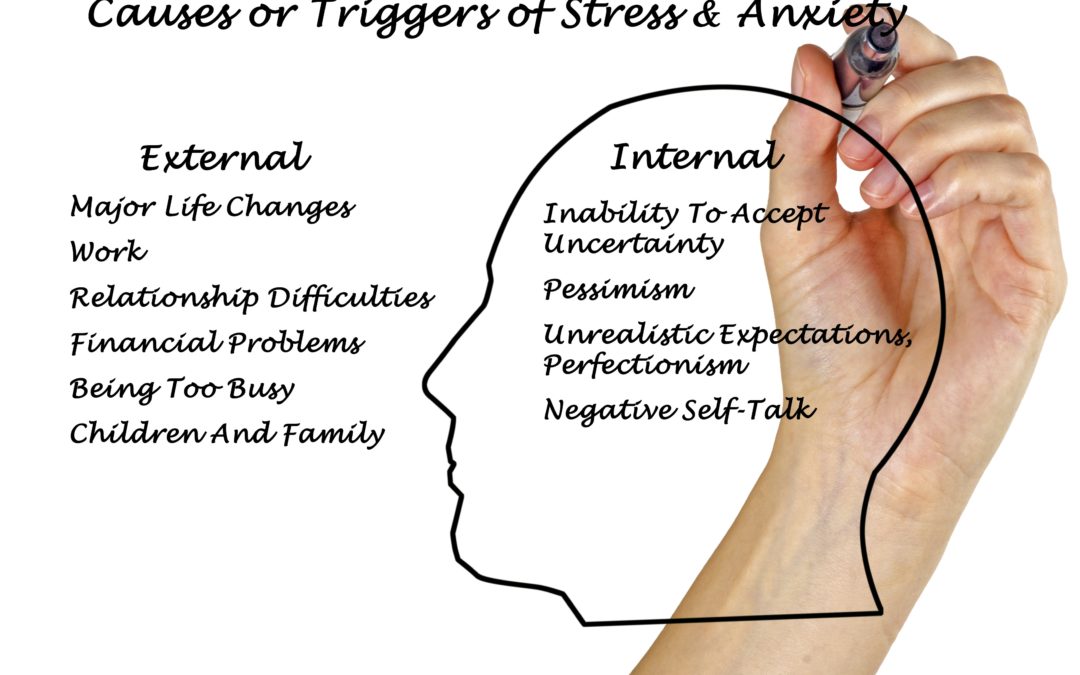

Unfortunately, although the inner voice can help us control our behavior and improve our results, it can be a problem. For example, it can interfere with sleep just when it is needed. And self-digging, rumination (constant scrolling in the head of the same thought) and negative words about oneself are associated with the development of depression. In addition, people suffering from depression cannot stop the flow of thoughts in their head, even when they need to focus on something else.

It turns out that, on the one hand, we need conversations with ourselves, and on the other hand, the ability to use them to our advantage is important here, that is, to get rid of useless thoughts and include those related to current tasks. It takes time to learn how to do this, but the goal is quite achievable. Here are some tips that psychologists give. More precisely, not even advice, but ideas that should be remembered.

- Talking to yourself is normal. The internal monologue is part of a constant stream of consciousness that cannot be absent when we are awake.

According to some estimates, the speed of internal speech is up to 4000 words per minute, 10 times faster than oral speech. If a person really has serious psychological disorders, for example, schizophrenia, he can also talk to himself, but there is a difference: he is talking with voices that he perceives as outsiders, while in a normal internal monologue we know for sure that the author is this is us.

According to some estimates, the speed of internal speech is up to 4000 words per minute, 10 times faster than oral speech. If a person really has serious psychological disorders, for example, schizophrenia, he can also talk to himself, but there is a difference: he is talking with voices that he perceives as outsiders, while in a normal internal monologue we know for sure that the author is this is us. - Negative self-talk is also normal, but up to certain limits. Usually psychologists call to get rid of negativity in conversations with oneself, to eradicate thoughts like “I can’t do it”, “I don’t deserve this”, and so on. But some experts point out that in principle there is nothing wrong with thoughts with a negative coloring, because evolution taught us to do so. “Two-thirds of our daily thoughts are negative,” says Sherry Benton, a former professor emeritus at the University of Florida. “They warn us of danger, help us analyze past actions, and help us understand who we are.

All this gave us a chance to survive when we were hunters and gatherers. If 1/3 of the internal dialogue can be called positive and self-affirming, then you are doing a great job.

All this gave us a chance to survive when we were hunters and gatherers. If 1/3 of the internal dialogue can be called positive and self-affirming, then you are doing a great job. - However, an excessive amount of self-criticism and reproaches in the internal monologue is an alarming sign. The internal narrative is connected with emotions, and if it is gloomy, it can lead to anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts.

- The internal monologue will be useful if it is neutral. If he relies on facts, if mistakes are perceived not as a disaster, but as something that can be avoided next time, if the feeling of guilt for small misconduct passes relatively quickly. This is not the same as positive thinking. It is better to replace negative phrases in a conversation with yourself not with positive statements, but with neutral and “applied” ones. For example, pronouncing immediate plans or instructions on how best to do this or that job.

- Self-talk should not be avoided; on the contrary, it can be made into a good habit.

They can become a kind of mindfulness technique if you chat with yourself after a stressful event or on the eve of an important day.

They can become a kind of mindfulness technique if you chat with yourself after a stressful event or on the eve of an important day.

In summary: if you learn to talk to yourself correctly, this process does not distract you from business, but, on the contrary, stimulates cognitive activity and efficiency in general. The one who mumbles something under his breath is not necessarily a mad scientist: he may be a genius, using all resources to optimize the functioning of the brain.

Did you like the material? Sign up for the weekly Reminder email newsletter!

why dialogue with oneself is dangerous — T&P

In psychology, internal dialogue is one of the forms of thinking, the process of communication between a person and himself. It becomes the result of the interaction of different ego states: "child", "adult" and "parent". The inner voice often criticizes us, gives advice, appeals to common sense. But is he right? T&P asked several people from different fields what their inner voices sound like and asked a psychologist to comment on this.

Internal dialogue has nothing to do with schizophrenia. Everyone has voices in their heads: it is we ourselves (our personality, character, experience) who speak to ourselves, because our Self consists of several parts, and the psyche is very complex. Thinking and reflection are impossible without an internal dialogue. Not always, however, it is framed as a conversation, and not always some of the remarks seem to be uttered by the voices of other people - as a rule, relatives. The “voice in the head” can also sound like one’s own, or it can “belong” to a completely stranger: a classic of literature, a favorite singer.

From the point of view of psychology, internal dialogue is a problem only if it develops so actively that it begins to interfere with a person in everyday life: it distracts him, confuses him. But more often this silent conversation "with oneself" becomes material for analysis, a field for finding sore spots and a testing ground for developing a rare and valuable ability to understand and support oneself.

Roman

sociologist, marketer

It is difficult for me to single out any characteristics of the inner voice: shades, timbre, intonations. I understand that this is my voice, but I hear it in a completely different way, not like the others: it is more booming, low, rough. Usually in the internal dialogue, I imagine the acting role model of some situation, hidden direct speech. For example, what would I say to this or that public (despite the fact that the public can be very different: from casual passers-by to clients of my company). I need to convince them, to convey my idea to them. Usually I also play intonations, emotions and expression.

At the same time, there is no discussion as such: there is an internal monologue with reflections like: “What if?”. Does it happen that I myself call myself an idiot? Happens. But this is not a condemnation, but rather something between annoyance and a statement of fact.

If I need an outside opinion, I change the prism: for example, I try to imagine what one of the classics of sociology would say. In terms of sound, the voices of the classics are no different from mine: I remember exactly logic and "optics". I can clearly distinguish alien voices only in a dream, and they are accurately modeled by real counterparts.

In terms of sound, the voices of the classics are no different from mine: I remember exactly logic and "optics". I can clearly distinguish alien voices only in a dream, and they are accurately modeled by real counterparts.

Anastasia

prepress specialist

In my case, the inner voice sounds like my own. Basically, he says: "Nastya, stop it", "Nastya, don't be stupid" and "Nastya, you're a fool!". This voice appears infrequently: when I feel uncollected, when my own actions make me dissatisfied. The voice is not angry - rather irritated.

I have never heard in my thoughts either my mother's, or my grandmother's, or anyone else's voice: only my own. He can scold me, but within certain limits: without humiliation. This voice is more like my coach: it presses the buttons that encourage me to take action.

Ivan

screenwriter

What I hear in my mind is not formed as a voice, but I recognize this person by the structure of my thoughts: she looks like my mother. And even more precisely: it is an "internal editor" that explains how to make the mother like it. For me, as a hereditary filmmaker, this is an unflattering name, because in the Soviet years for a creative person (director, writer, playwright) an editor is a stupid protege of the regime, a not very educated censor who revels in his own power. It is unpleasant to realize that this type in you censors thoughts and clips the wings of creativity in all areas.

And even more precisely: it is an "internal editor" that explains how to make the mother like it. For me, as a hereditary filmmaker, this is an unflattering name, because in the Soviet years for a creative person (director, writer, playwright) an editor is a stupid protege of the regime, a not very educated censor who revels in his own power. It is unpleasant to realize that this type in you censors thoughts and clips the wings of creativity in all areas.

The “internal editor” gives many of his comments on the case. However, the question lies in the purpose of this "case". To summarize, he says: "Be like everyone else and don't stick your head out." He feeds the inner coward. “You need to be an excellent student,” because it eliminates problems. Everyone likes it. He makes it difficult to understand what I myself want, whispers that comfort is good, and the rest later. This editor doesn't really let me be an adult in the good sense of the word. Not in the sense of dullness and lack of play space, but in the sense of the maturity of the individual.

I hear my inner voice mostly in situations that remind me of my childhood, or when a direct display of creativity and fantasy is needed. Sometimes I succumb to the "editor" and sometimes I don't. The most important thing is to recognize his intervention in time. Because he disguises himself well, hiding behind pseudological conclusions that do not really make sense. If I recognized him, then I try to understand what the problem is, what I myself want and where the truth really is. When this voice, for example, interferes with my creativity, I try to stop and go into the space of "complete emptiness", starting all over again. The difficulty lies in the fact that the "editor" can be difficult to distinguish from simple common sense. To do this, you need to listen to your intuition, move away from the meaning of words and concepts. Often this helps.

Irina

translator

My internal dialogue is designed as the voices of my grandmother and Masha's friend. These are people whom I considered close and important: I lived with my grandmother in my childhood, and Masha was there at a difficult time for me. Grandma's voice says that I have crooked hands and that I'm clumsy. And Masha's voice repeats different things: that I again got in touch with the wrong people, I lead the wrong lifestyle and do the wrong things. They both always judge me. At the same time, voices appear at different moments: when something doesn’t work out for me, my grandmother “says”, and when everything works out for me and I feel good, Masha.

Grandma's voice says that I have crooked hands and that I'm clumsy. And Masha's voice repeats different things: that I again got in touch with the wrong people, I lead the wrong lifestyle and do the wrong things. They both always judge me. At the same time, voices appear at different moments: when something doesn’t work out for me, my grandmother “says”, and when everything works out for me and I feel good, Masha.

I react aggressively to these voices: I try to silence them, I argue with them mentally. I tell them back that I know better what and how to do with my life. Most often, I manage to argue with my inner voice. But if not, I feel guilty and feel bad.

Kira

prose editor

In my mind I sometimes hear my mother's voice, which condemns me and devalues my achievements, doubts me. This voice is always dissatisfied with me and says: “What are you talking about! Are you out of your mind? Do better profitable business: you have to earn. Or: "You must live like everyone else. " Or: "You will not succeed: you are nobody." It appears if I have to take a bold step or take a risk. In such situations, the inner voice, as it were, tries to manipulate me (“mom is upset”) to persuade me to the safest and most unremarkable course of action. To make him happy, I must be inconspicuous, diligent, and everyone likes me.

" Or: "You will not succeed: you are nobody." It appears if I have to take a bold step or take a risk. In such situations, the inner voice, as it were, tries to manipulate me (“mom is upset”) to persuade me to the safest and most unremarkable course of action. To make him happy, I must be inconspicuous, diligent, and everyone likes me.

I also hear my own voice, not calling me by my first name, but by a nickname that my friends have come up with. He usually sounds a bit annoyed but friendly and says, “So. Stop”, “Well, what are you, baby” or “Everything, come on.” It encourages me to focus or take action.

Ilya Shabshin

counseling psychologist, leading specialist of the Psychological Center on Volkhonka

This whole selection speaks of what psychologists are well aware of: most of us have a very strong inner critic. We communicate with ourselves mainly in the language of negativity and rude words, using the whip method, and we have practically no self-support skills.

In Roman's commentary, I liked the technique, which I would even call psychotechnics: "If I need a third-party opinion, I try to imagine what one of the classics of sociology would say." This technique can be used by people of different professions. In Eastern practices, there is even the concept of an "inner teacher" - a deep wise inner knowledge that you can turn to when it's hard for you. A professional usually has one or another school or authoritative figures behind him. Imagine one of them and ask what he would say or do is a productive approach.

An illustrative illustration of the general theme is Anastasia's commentary. A voice that sounds like your own and says: “Nastya, you are a fool! Don't be dumb. Stop it,” is, of course, according to Eric Berne, the Critical Parent. It is especially bad that the voice appears when she feels "uncollected", if her own actions cause dissatisfaction - that is, when, in theory, the person just needs to be supported. And instead, the voice tramples into the ground. .. And although Anastasia writes that he acts without humiliation, this is a small consolation. Maybe, as a “coach”, he presses the wrong buttons, and it’s not worth kicking, not reproaching, not insulting him to encourage himself to action? But, I repeat, such interaction with oneself is, unfortunately, typical.

.. And although Anastasia writes that he acts without humiliation, this is a small consolation. Maybe, as a “coach”, he presses the wrong buttons, and it’s not worth kicking, not reproaching, not insulting him to encourage himself to action? But, I repeat, such interaction with oneself is, unfortunately, typical.

You can induce yourself to action by first removing your fears by saying to yourself: “Nastya, everything is fine. It's okay, we'll figure it out." Or: "Here, look: it turned out well." "Yes, well done, you can do it!". “Do you remember how you did everything great then?” This method is suitable for any person who tends to criticize himself.

The last paragraph in Ivan's text is important: it describes the psychological algorithm for dealing with the inner critic. Point one: "Recognize interference." This problem often arises: something negative is disguised under the guise of useful statements, penetrates a person’s soul and establishes its own rules there. Then the analyst turns on, trying to understand what the problem is. According to Eric Berne, this is the adult part of the psyche, the rational one. Ivan even has author's tricks: "go out into the space of complete emptiness", "listen to intuition", "depart from the meaning of words and understand everything". Great, that's how it's supposed to be! Based on general rules and a common understanding of what is happening, it is necessary to find your own approach to what is happening. As a psychologist, I applaud Ivan: he has learned to talk to himself well. Well, what he fights is a classic: the internal editor is still the same critic.

According to Eric Berne, this is the adult part of the psyche, the rational one. Ivan even has author's tricks: "go out into the space of complete emptiness", "listen to intuition", "depart from the meaning of words and understand everything". Great, that's how it's supposed to be! Based on general rules and a common understanding of what is happening, it is necessary to find your own approach to what is happening. As a psychologist, I applaud Ivan: he has learned to talk to himself well. Well, what he fights is a classic: the internal editor is still the same critic.

“At school we are taught to extract square roots and carry out chemical reactions, but they don’t teach us to communicate normally with ourselves anywhere”

Ivan has another interesting observation: “You need to keep a low profile and be an excellent student.” Kira notes the same. Her inner voice also says that she should be invisible and everyone should like her. But this voice introduces its own, alternative logic, because you can either be the best or keep a low profile. However, such statements are not taken from reality: these are all internal programs, psychological attitudes from various sources.

However, such statements are not taken from reality: these are all internal programs, psychological attitudes from various sources.

The “keep your head down” attitude (like most others) is taken from education: in childhood and adolescence, a person draws conclusions about how to live, gives himself instructions based on what he hears from parents, educators, teachers.

In this regard, the example of Irina looks sad. Close and important people - a grandmother and a friend - tell her: "You have crooked hands, and you are clumsy", "you live wrong." A vicious circle arises: her grandmother condemns her when something does not work out, and her friend when everything is fine. Total criticism! Neither when it is good, nor when it is bad, there is no support and consolation. Always a minus, always a negative: either you are clumsy, or something else is wrong with you.

But Irina is doing well, she behaves like a fighter: she silences voices or argues with them. This is how it should be done: the power of the critic, whoever he may be, must be weakened. Irina says that most often she gets votes over an argument - this phrase suggests that the opponent is strong. And in this regard, I would suggest that she try other ways: firstly (since she hears it as a voice), imagine that it comes from the radio, and she turns the volume knob towards the minimum, so that the voice fades, it gets worse heard. Then, probably, his power will weaken, and it will become easier to outguess him - or even just brush him off. After all, such an internal struggle creates quite a lot of tension. Moreover, Irina writes at the end that she feels guilty if she fails to argue.

Irina says that most often she gets votes over an argument - this phrase suggests that the opponent is strong. And in this regard, I would suggest that she try other ways: firstly (since she hears it as a voice), imagine that it comes from the radio, and she turns the volume knob towards the minimum, so that the voice fades, it gets worse heard. Then, probably, his power will weaken, and it will become easier to outguess him - or even just brush him off. After all, such an internal struggle creates quite a lot of tension. Moreover, Irina writes at the end that she feels guilty if she fails to argue.

Negative ideas penetrate deeply into our psyche in the early stages of its development, especially easily in childhood, when they come from big authority figures with whom, in fact, it is impossible to argue. The child is small, and around him are huge, important, strong masters of this world - adults on whom his life depends. You can't really argue here.

In adolescence, we also solve difficult problems: we want to show ourselves and others that you are already an adult, and not a small one, although in fact, deep down you understand that this is not entirely true. Many teenagers become vulnerable, although outwardly they look prickly. At this time, statements about yourself, about your appearance, about who you are and what you are, sink into the soul and later become dissatisfied with inner voices that scold and criticize. We talk to ourselves so badly, so nastily, as we would never talk to other people. You would never say anything like that to a friend - and in your head your voices towards you easily allow yourself to do this.

Many teenagers become vulnerable, although outwardly they look prickly. At this time, statements about yourself, about your appearance, about who you are and what you are, sink into the soul and later become dissatisfied with inner voices that scold and criticize. We talk to ourselves so badly, so nastily, as we would never talk to other people. You would never say anything like that to a friend - and in your head your voices towards you easily allow yourself to do this.

To correct them, first of all, you need to realize: “The things that sound in my head are not always good thoughts. There may be opinions and judgments that were simply learned once. They don’t help me, it’s not useful for me, and their advice doesn’t lead to anything good.” You need to learn to recognize them and deal with them: to refute, muffle or otherwise remove the inner critic from yourself, replacing it with an inner friend who provides support, especially when it’s bad or difficult.

At school, we are taught to extract square roots and carry out chemical reactions, but nowhere is it taught to communicate normally with oneself.