Crisis intervention plan mental health

Do You Need One? I Psych Central

Preparing for a mental health emergency can make a world of difference when you’re facing a crisis.

The day after I had a mental health crisis, I found all the sharp objects removed from the house. I felt hungover, wrecked — and very much eager to never go through that again.

I didn’t go to an emergency room, but not because I shouldn’t have. It was because I didn’t know what to do.

The next day, I met with my therapist and my partner. My therapist listed numbers to call and resources I could use for next time. Next time? I almost panicked at the very idea.

But the truth is — like millions of people worldwide — I live with mental health conditions. And without a crisis plan, I wouldn’t feel as safe or confident that I would know what to do if there is a next time.

Are you currently in crisis?

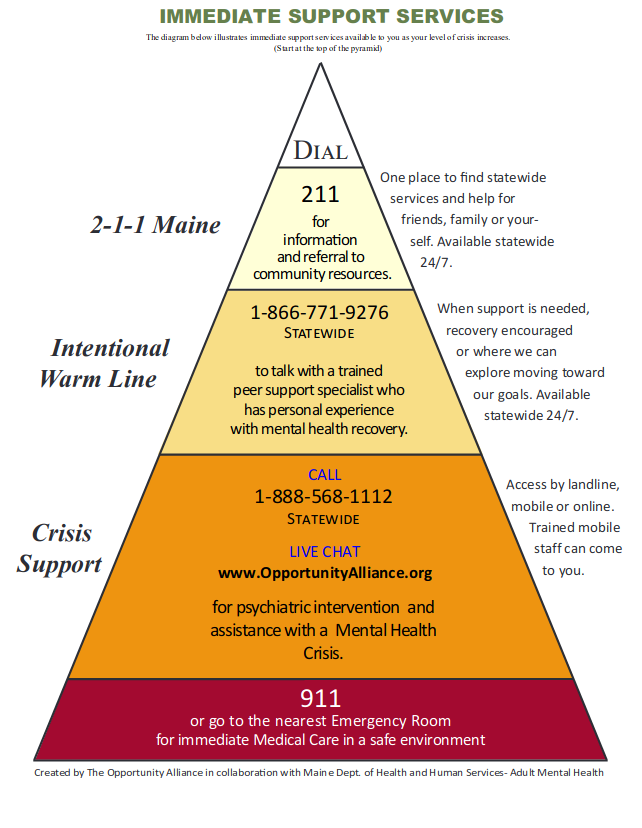

If you feel you’re having a mental health emergency, now isn’t the time to create a plan. If you need to speak with someone immediately, you can:

- Call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988

- Text “HOME” to the Crisis Text Line at 741741

- Check out Befrienders Worldwide or Suicide Stop, if you’re not in the United States and need to find your country’s crisis hotline

If you decide to call an emergency number like 911, ask the operator to send someone trained in mental health, like Crisis Intervention Training (CIT) officers.

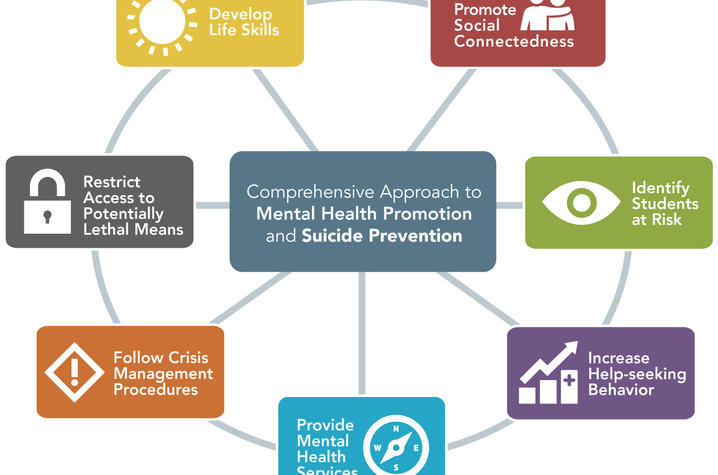

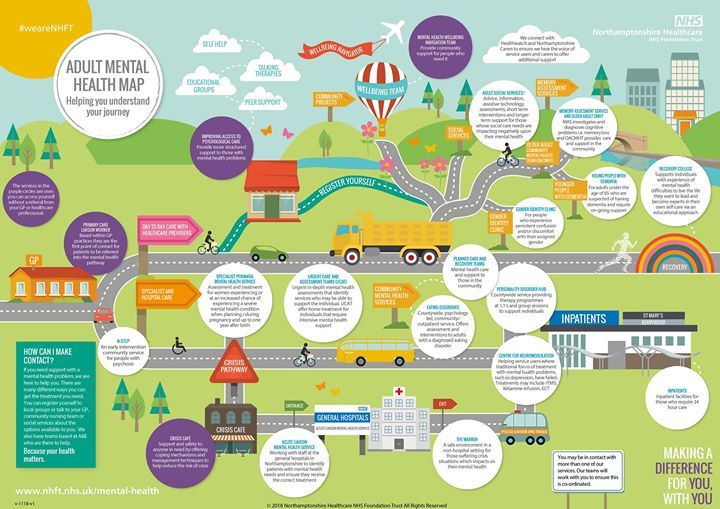

A mental health crisis plan is a plan of action that’s made before a crisis occurs, so you and people in your support system know what to do when an emergency comes up.

Anyone can create a crisis plan by putting together a list of resources, information, and directions. This can make a big difference since decision making and logical thinking can go out the window when you’re under extreme stress.

The point of a crisis plan is to prepare for a mental health emergency.

You can create your crisis plan on your own, but you can also reach out to a mental health professional or any loved ones who might be involved in your support to help.

Your crisis plan can be for only you, or you can share it with your treatment team and loved ones. There are also legal documents you may find necessary for severe conditions.

Types of crisis plans:

Joint crisis plan

According to research in 2021, a joint crisis plan (JCP) is a “psychiatric advance statement that describes how to recognize early signs of crisis and how to manage crises.”

The three important things to include in a joint crisis plan are:

- crisis triggers — what might cause a crisis

- crisis manifestations — what your symptoms and behaviors are during a mental health crisis

- strategies to deal with the crisis

Psychiatric advance directives (PADs)

PADs are legal documents that allow someone to act on your behalf. Typically, you’ll write a PAD when you’re not in crisis, detailing everything you want for your treatment if you become unable to make these choices.

If you have a severe mental health condition or symptoms (like psychosis), you may want to create a PAD.

Want to learn more?

- The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) explains more details about PADs and has a webinar.

- The National Resource Center on Psychiatric Advance Directions has state-by-state information and links to forms.

Wellness recovery action plan

This plan helps you and your support team create a plan for your overall mental healthcare — in and out of crisis — and how to avoid future emergencies.

This plan may involve:

- a list of wellness tools

- a daily routine

- your stressors

- early warning signs of a crisis or your symptoms worsening

- a crisis plan

- a post-crisis plan

If you want a full outline, you can learn more here.

When drafting a crisis plan, you may want to take past emergencies into consideration. What happened? What support do you wish you had? What do you wish you knew then?

Your crisis plan — and whom you share it with — will be unique to you and your condition.

I’ve learned from my past crises that:

- I need to have numbers programmed in my phone at my fingertips

- my partner needs to know the plan

- if I show any signs of serious self-harm, a trip to the emergency room can provide immediate help

To create your crisis plan, we broke it into two pieces: medical information and the actual plan during a crisis.

Medical information

While you may not need this information in a crisis, having this information can help anyone (like an ER doctor) who isn’t familiar with your health history.

Consider the outline below:

- Basic medical information

- emergency contacts

- names of your primary care doctor and mental health pros like a therapist and psychiatrist

- anything else that might be helpful, like insurance information

- Medical history

- any allergies or reactions to medications

- any history of severe side effects to psychiatric medications

- past conditions, illnesses, or medical procedures

- past psychiatric hospitalizations

- Current medical information

- current diagnoses

- current medications including the date prescribed, your prescriber, and the dosage

- to prevent interactions, anything else you’re taking (supplements or recreational drugs)

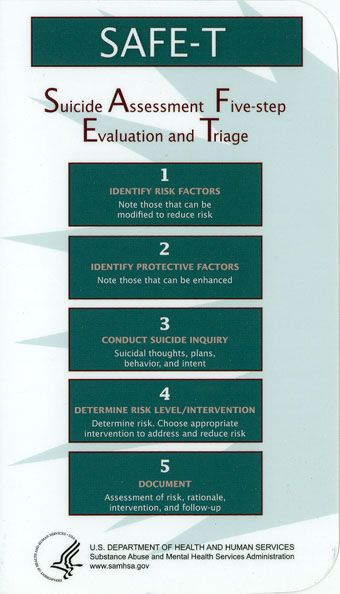

Crisis plan

For your crisis plan, consider including:

- emergency resources (hotline numbers, your local mental health department or psychiatric care center, etc.

)

) - steps to follow if you need to seek help from professionals

- behaviors that mean you’ll go to a hospital

- behaviors that mean you’ll call 911

When creating your crisis plan, you don’t need to do it alone. A mental health professional may be able to help you find the best emergency resource numbers and figure out which behaviors to add to your list.

Pro tip:For my emergency resource, I put the main number as *Crisis*, so it’s the first contact in my phone book.

Be sure to have a few copies of your plan (and share them with your support team!), and update the medical information whenever your meds change.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness provides helpful printouts in their resource guide — Navigating a Mental Health Crisis — that can be added to a mental health crisis plan.

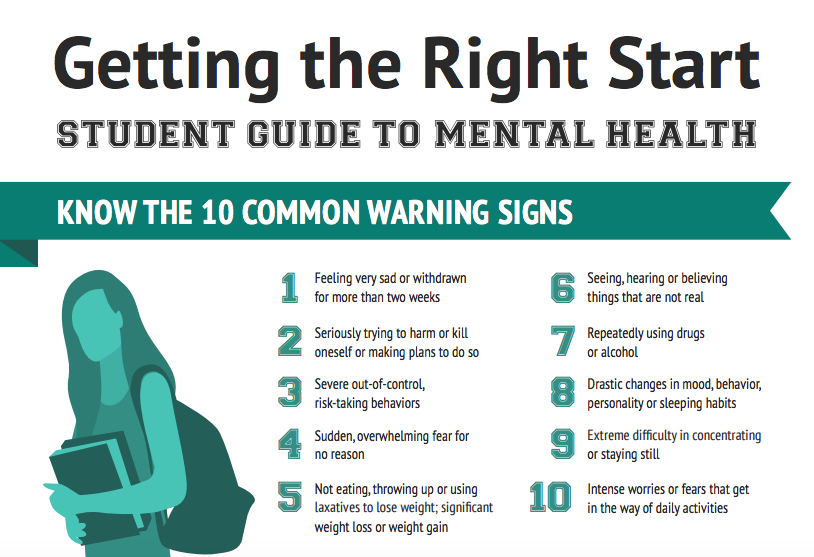

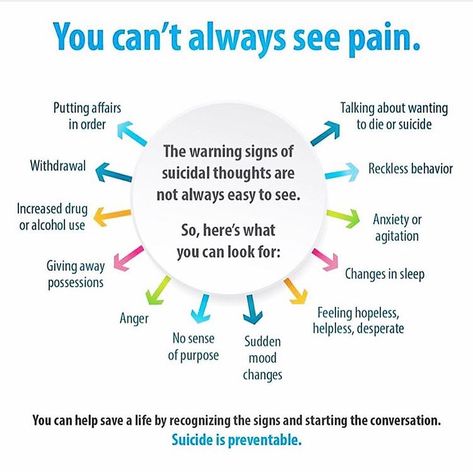

Mental health crisis warning signs

While your crisis and symptoms will vary, here are some common behaviors and symptoms that could indicate a crisis:

- rapid, sudden, and intense changes in mood

- an inability to function in most daily tasks

- signs of psychosis such as hallucinations or delusions

- paranoia

- an increase in agitation, anger, or any violence

- increased use of alcohol or drugs

- suicidal ideation such as thoughts or feelings about suicide

- signs of self-injury

Crisis resources

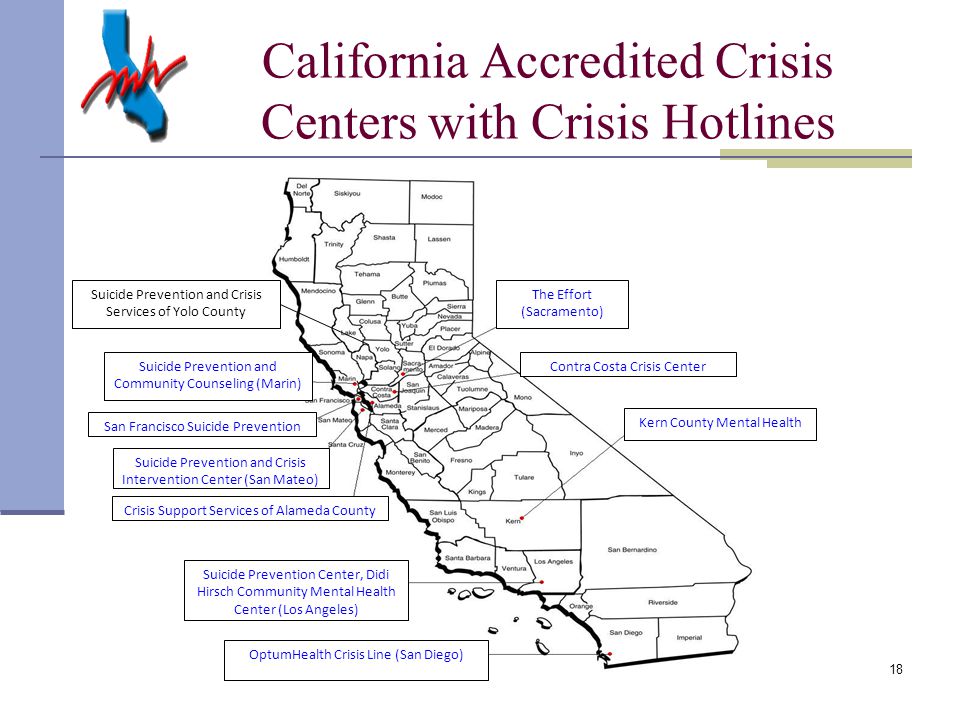

Having a local resource for your crisis plan is helpful, but there are also several national resources for support:

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

- Crisis Text Line

- Trans Lifeline

- The Trevor Project

- Veterans Crisis Line

If you’re outside the United States, you can find a crisis hotline through Befrienders Worldwide or Suicide Stop: International Help Center.

A note on calling 911

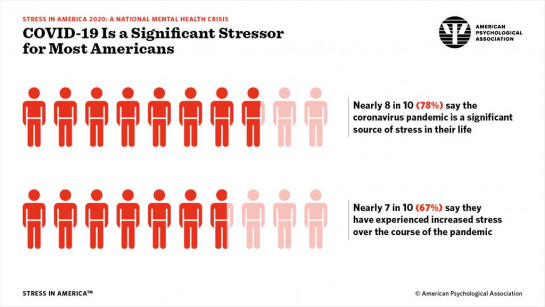

It’s completely OK if you don’t feel safe or comfortable calling 911 or an emergency number for a mental health emergency. According to the Treatment Advocacy Center, people with untreated mental health conditions are 16 times more likely to be fatally harmed by law enforcement.

Because of this, you may want to consider calling 911 only if there’s an immediate danger to you or someone else or if you know your county has a crisis intervention team.

Depending on where you live, there may not be professionals trained in handling mental health concerns. But if you do call, be sure to tell the operator that it’s a mental health crisis, so officers can know to come with de-escalation in mind.

Crisis plans are there as an act of prevention — it’s a lot easier to have information and directions written out before you need it, rather than relying on reacting at the moment.

I like to think about it like any other type of emergency preparedness plan. People have emergency packs for earthquakes, fires, and tornados so they don’t have to rush around, can act fast, and be safe as soon as possible.

People have emergency packs for earthquakes, fires, and tornados so they don’t have to rush around, can act fast, and be safe as soon as possible.

Your mental health emergency deserves the same kind of prep. You deserve safety and peace of mind.

Crisis plans can also be helpful for:

- reducing forced or involuntary hospital admissions

- preparing your loved ones and support team to know how to best help you

- learning what works and what doesn’t

- making recovery more streamlined

- comfort in the knowledge that you’ll be ready in a mental health emergency

I wish I’d been given the resources to create a crisis plan before I knew what a crisis looked like.

A mental health crisis plan is my safety net. It’s the difference between an unknown, out-of-control situation and knowing that I’ve done what I can to prevent worse outcomes and get to safety.

You can’t always control or prevent a crisis entirely — mental health emergencies can occur even when you’re following your treatment plans and doing your best. But you can still be prepared.

But you can still be prepared.

With the right tools, we can seek help sooner and take care of ourselves now for moments when we may not be able to. Remember, you’re not alone. You deserve support.

If you’re not in a crisis but don’t currently have a mental health team, Psych Central has some resources that can get you started:

- What to do if you can’t afford therapy

- 10 tips to find the right therapist

- The best online therapy programs

- The best free online therapy and support services

- The best online psychiatry services

Being Prepared for a Crisis

No one wants to worry about the possibility of a crisis, but they do happen. That doesn't mean you have to feel powerless. Many healthcare providers require patients to create a crisis plan, and may suggest that it be shared with friends and family. Ask your loved one if he has developed a plan.

Ask your loved one if he has developed a plan.

A Wellness Recovery Action Plan can also be very helpful for your loved one to plan his overall care, and how to avoid a crisis. If he will not work with you on a plan, you can make one on your own. Be sure to include the following information:

- Phone numbers for your loved one’s therapist, psychiatrist and other healthcare providers

- Family members and friends who would be helpful, and local crisis line number

- Phone numbers of family members or friends who would be helpful in a crisis

- Local crisis line number (you can usually find this by contacting your NAMI Affiliate, or by doing an internet search for “mental health crisis services” and the name of your county)

- Addresses of walk-in crisis centers or emergency rooms

- The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

- Your address and phone number(s)

- Your loved one’s diagnosis and medications

- Previous psychosis or suicide attempts

- History of drug use

- Triggers

- Things that have helped in the past

- Mobile Crisis Unit phone number in the area (if there is one)

- Determine if police officers in the community have Crisis Intervention Training (CIT)

Go over the plan with your loved one, and if he is comfortable doing so, with his doctor. Keep copies in several places. Store a copy in a drawer in your kitchen, your glove compartment, on your smartphone, your bedside table, or in your wallet. Also, keep a copy in a room in your home that has a lock and a phone.

Keep copies in several places. Store a copy in a drawer in your kitchen, your glove compartment, on your smartphone, your bedside table, or in your wallet. Also, keep a copy in a room in your home that has a lock and a phone.

Psychiatric Advance Directives

You may also want to ask about a Psychiatric Advance Directive (PAD), which is a legal document that allows a second party to act on your loved one's behalf if he becomes acutely ill and unable to make decisions about treatment. The PAD is written by your loved one when they are currently ‘competent.’ It details the individual’s preferences for treatment should they become unable to make such decisions due to their mental health condition. Planning ahead can make a huge difference in your loved one’s treatment experience in the future.

Conservatorship

In some cases, a person who is suicidal refuses to seek or accept treatment. They may engage in self-harm, risky behaviors and multiple suicide attempts. Oftentimes a person in this condition has a serious underlying mental illness that they refuse treatment for. Unfortunately, because they present such a significant danger to themselves, they may need someone else to make these decisions for them.

Unfortunately, because they present such a significant danger to themselves, they may need someone else to make these decisions for them.

A conservatorship is a legal relationship granted by a court that allows one person (the conservator) to make personal decisions for another (the ward), who has shown themselves to be unable to fulfill the basic requirements needed to protect their own health and safety. Unless otherwise specified, the conservator has all of the powers that a parent has over a minor, which would allow the conservator to direct the ward’s mental health treatment and suicide prevention measures.

Download Our Crisis Guide

Crisis intervention after major disasters

Year of publication and journal number:

2010, No. 3

interventions when working with traumatized adults and children in the immediate aftermath of major disasters. The article was written in the aftermath of the 1999 floods that devastated much of Venezuela, killing 50,000 people and leaving 500,000 people homeless and psychologically traumatized. The content of the article was originally presented as a lecture for professionals and non-professionals working with shelter survivors. The text was then written down in English, translated into Spanish, distributed to counselors working in shelters in Caracas, and sent via the Internet to mental health professionals throughout the country. Although the article was written for professionals who have worked with victims of the floods in Venezuela, the author hopes that it will be useful to other mental health professionals who will be working with survivors of various types of disasters. nine0003

The article was written in the aftermath of the 1999 floods that devastated much of Venezuela, killing 50,000 people and leaving 500,000 people homeless and psychologically traumatized. The content of the article was originally presented as a lecture for professionals and non-professionals working with shelter survivors. The text was then written down in English, translated into Spanish, distributed to counselors working in shelters in Caracas, and sent via the Internet to mental health professionals throughout the country. Although the article was written for professionals who have worked with victims of the floods in Venezuela, the author hopes that it will be useful to other mental health professionals who will be working with survivors of various types of disasters. nine0003

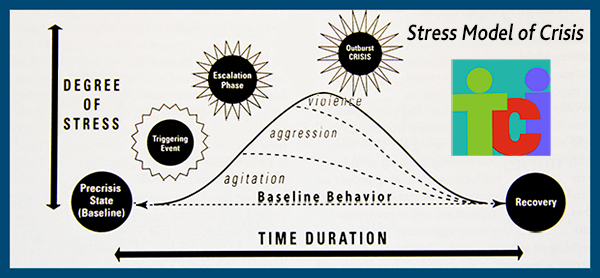

WHAT IS A PSYCHOLOGICAL CRISIS?

A psychological crisis occurs when a traumatic event overwhelms a person's ability to cope with the trauma in their own way. Psychological crises cannot be reliably predicted from the events that precede them. An event that plunges one person into a psychological crisis will not necessarily cause a crisis in another. However, some things usually cause crisis psychological reactions. These include physical attacks, torture, rape, car accidents, severe personal loss, and natural disasters such as earthquakes, fires and floods. Such incidents often cause a psychiatric disorder, which we call ACUTE STRESS DISORDER. Acute stress disorder is characterized by feelings of intense fear, helplessness, and terror. There may also be emotional numbness, lack of emotional sensitivity, a state of detachment, poor awareness of what is happening, a feeling of unreality of what is happening, or amnesia. People experiencing acute stress disorder may experience anxiety, pain, despair or hopelessness, become easily excitable, irritable, restless. They may relive the event in recurring dreams, flashbacks, or persistent memories of the trauma. The person may avoid people, places, and objects that may evoke memories of the traumatic event.

An event that plunges one person into a psychological crisis will not necessarily cause a crisis in another. However, some things usually cause crisis psychological reactions. These include physical attacks, torture, rape, car accidents, severe personal loss, and natural disasters such as earthquakes, fires and floods. Such incidents often cause a psychiatric disorder, which we call ACUTE STRESS DISORDER. Acute stress disorder is characterized by feelings of intense fear, helplessness, and terror. There may also be emotional numbness, lack of emotional sensitivity, a state of detachment, poor awareness of what is happening, a feeling of unreality of what is happening, or amnesia. People experiencing acute stress disorder may experience anxiety, pain, despair or hopelessness, become easily excitable, irritable, restless. They may relive the event in recurring dreams, flashbacks, or persistent memories of the trauma. The person may avoid people, places, and objects that may evoke memories of the traumatic event. It may be difficult for him to concentrate and function in his usual way at home and at work. The person may also experience survivor guilt or guilt for not providing enough help to others. Some people may become aggressive or self-destructive, neglect self-care, be confused, or behave strangely. nine0003

It may be difficult for him to concentrate and function in his usual way at home and at work. The person may also experience survivor guilt or guilt for not providing enough help to others. Some people may become aggressive or self-destructive, neglect self-care, be confused, or behave strangely. nine0003

If prompt action is taken, symptoms of acute stress disorder usually improve or disappear completely within 30 days. In some cases, especially if no treatment is given, acute stress disorder may persist. If it lasts from one to three months, we can call it ACUTE POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER. If symptoms persist for more than three months, we call it CHRONIC PTSD. (This diagnostic information is taken from DSM-IV, 1994). Untreated symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder often persist for many years and become a serious obstacle to normal life. It is also important to remember that when a person is struggling with a severe stress response, the family or any other people in the patient's environment are also likely to be affected by the symptoms of the patient's post-traumatic stress disorder.

WORKING WITH PATIENTS WITH ACUTE AND POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

Counselors who work with patients with acute and post-traumatic stress disorder help them cope with the tasks they face after a traumatic event (reporting an incident, making phone calls, making changes to daily routine) and provide a safe space to talk or about about the event itself, about the symptoms, or about everything that worries the patient in the first place. Although it can be painful at first to talk about the traumatic event, people often report feeling relieved and relieved of symptoms after talking about it. After they have presented the various sides of the problem and looked at them together with the consultant, their vision of the situation becomes clearer. While adults may converse with a therapist, a child experiencing acute stress reactions is likely to communicate in children's non-verbal language of play as well as verbal metaphors in the form of stories that they can make up. Therefore, with children, we would rather conduct a session of play therapy (we will talk about this a little later). As mentioned above, in many cases a sudden change in behavior in an injured person affects the entire family. In such cases, it is often helpful for the whole family to meet with a therapist who can help deal with these difficult moments and improve communication between family members. A traumatic event is one in which the person's coping mechanisms are overwhelmed by the intensity of the situation. In the treatment of acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder, we need to reconstruct the event, break it down into smaller pieces, make sense of it, deal with it, digest it, and make it more understandable. However, there may be times when a person is uninterested or unable to talk about a particular traumatic event. In such cases, he is encouraged to talk about everything that worries him in the first place, and sometimes the symptoms, however, subside. nine0003

Therefore, with children, we would rather conduct a session of play therapy (we will talk about this a little later). As mentioned above, in many cases a sudden change in behavior in an injured person affects the entire family. In such cases, it is often helpful for the whole family to meet with a therapist who can help deal with these difficult moments and improve communication between family members. A traumatic event is one in which the person's coping mechanisms are overwhelmed by the intensity of the situation. In the treatment of acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder, we need to reconstruct the event, break it down into smaller pieces, make sense of it, deal with it, digest it, and make it more understandable. However, there may be times when a person is uninterested or unable to talk about a particular traumatic event. In such cases, he is encouraged to talk about everything that worries him in the first place, and sometimes the symptoms, however, subside. nine0003

CONSULTANTS WORKING WITH VICTIMS OF NATURAL DISASTERS

In cases of natural disasters, such as earthquakes, catastrophic fires and floods, it is important for consultants to remember that the crisis affects everyone, including the consultants themselves. There are a few ground rules to keep in mind:

There are a few ground rules to keep in mind:

1. CONSULTANTS SHOULD TAKE CARE OF THEMSELVES AND EACH OTHER - PHYSICALLY AND EMOTIONALLY

Such work easily overwhelms and drains counselors emotionally. They need to take breaks, eat properly, and rest when tired. A traumatized and depressed therapist cannot be of service to the people who need him. Experienced psychologists and psychiatrists who have never worked with crisis situations are often surprised to find how exhausting just three or four hours of crisis counseling can be for them. nine0003

2. ADVISERS SHOULD REMEMBER TO THINK CLEARLY

In a crisis it is easy to lose sight of things and become confused. The consultant should try to slow down, develop a list of priorities that he will refer to in each case, and discuss his clinical decisions with colleagues.

3. ADVISERS NEED TO SET PRIORITIES

In a crisis, people often lose the ability to distinguish the important from the unimportant. In each case, it will be useful for the consultant to have a list by which he will navigate in the course of work. This list may include the following information: patient's name, age, address, family members, physical illness or injury, time of last meal, etc. Before starting any psychological treatment, it is imperative to pay attention to issues such as safety, health problems, sleep, nutrition, and having a roof over your head. People are not able to overcome their fear until the real danger is eliminated. Many are delusional, anxious or depressed due to health problems. Others are agitated due to lack of sleep. If a person has not eaten for a while, they may be depressed, agitated, or have trouble thinking. It is dangerous to treat such problems as purely psychological. Sometimes the patient needs first of all food, rest, some first aid or treatment. nine0003

This list may include the following information: patient's name, age, address, family members, physical illness or injury, time of last meal, etc. Before starting any psychological treatment, it is imperative to pay attention to issues such as safety, health problems, sleep, nutrition, and having a roof over your head. People are not able to overcome their fear until the real danger is eliminated. Many are delusional, anxious or depressed due to health problems. Others are agitated due to lack of sleep. If a person has not eaten for a while, they may be depressed, agitated, or have trouble thinking. It is dangerous to treat such problems as purely psychological. Sometimes the patient needs first of all food, rest, some first aid or treatment. nine0003

4. CONSULTANTS SHOULD COOPERATE WITH EACH OTHER AND SUPERVIS EACH OTHER

Crisis work is best done where there is intense interdisciplinary interaction between colleagues. This environment gives counselors the opportunity to supervise each other and consult with doctors, nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers and others involved in the process. The severity of the problems can easily overwhelm the counselor and cloud their thinking. Counseling becomes an essential ingredient for conscientious crisis intervention. nine0003

The severity of the problems can easily overwhelm the counselor and cloud their thinking. Counseling becomes an essential ingredient for conscientious crisis intervention. nine0003

5. WORKING WITH PATIENTS IN A CRISIS IS NOT THE SAME LIKE MEETINGS WITH A PATIENT IN PRIVATE PRACTICE OR IN A CLINICAL SETTING

Your “office” for conducting a crisis intervention can be a large room with many other people doing all sorts of other things , or it could be outside altogether. The emergency nature of the situation and the need for support from others can pose a serious threat to privacy. Reception hours in crisis work have nothing to do with the dial. The consultant takes people when they need it. Sessions last as long as needs and resources allow. nine0003

6. CRISIS CONSULTANTS SHOULD BE GOOD

They need to put aside the private practice model and even abandon the clinical model. They need to look at the situation as it is and approach the work as creatively and innovatively as possible. They need to improvise with space, time, materials and resources. They need to work closely with others. They need to evaluate their task and choose goals appropriate to the circumstances and situation. They need to be able to forgive others and themselves when they lose their temper. And, if at all possible, they need to keep their sense of humor. nine0003

They need to improvise with space, time, materials and resources. They need to work closely with others. They need to evaluate their task and choose goals appropriate to the circumstances and situation. They need to be able to forgive others and themselves when they lose their temper. And, if at all possible, they need to keep their sense of humor. nine0003

CRISIS INTERVENTION

The setting of a crisis intervention is different from a clinical setting. The consultation may take place in a school or church, in a field or under a tree. And just as the setting of a crisis intervention differs from that of a clinical setting, so do the problems that a crisis counselor deals with. Problems include the symptoms described above in the Acute Stress Disorder section. In a crisis situation, the goal of treatment is not characterological change or insight into the childhood origin of the patient's problems. The goal of crisis intervention is to help the patient COOPE with the trauma. The goal is to help the patient ADJUST to the new situation. The goal is to RETURN THE PATIENT TO THE PREVIOUS LEVEL OF FUNCTIONING. To achieve these goals, the patient is encouraged to talk about his experiences, develop a view of the event, sort out the feelings associated with it, and decide how to deal with his problems. nine0003

The goal is to help the patient ADJUST to the new situation. The goal is to RETURN THE PATIENT TO THE PREVIOUS LEVEL OF FUNCTIONING. To achieve these goals, the patient is encouraged to talk about his experiences, develop a view of the event, sort out the feelings associated with it, and decide how to deal with his problems. nine0003

FIRST CONTACT

During the first contact, it will be useful to obtain some information such as the patient's name, health status, available social support system, etc., but a crisis patient should not be subjected to a lengthy pre-treatment assessment process. The counselor should try to calm the patient, clarify the issue, and invite the patient to talk. A good crisis therapist is a good listener, but the crisis therapist is often more active than a psychotherapist who meets with the patient on an ongoing basis. The crisis therapist clarifies, persuades, enlightens, advises on practical issues that the patient needs to deal with, and refers patients to the appropriate agencies and programs. The counselor should be constantly aware of the patient's health status, consult physicians for any problems that arise, and refer patients for medical treatment whenever anxiety, depression, agitation, or insomnia reaches a level that severely impairs functioning or makes crisis intervention impossible. nine0003

The counselor should be constantly aware of the patient's health status, consult physicians for any problems that arise, and refer patients for medical treatment whenever anxiety, depression, agitation, or insomnia reaches a level that severely impairs functioning or makes crisis intervention impossible. nine0003

LONG AND SHORT TERM GOALS

In the midst of a crisis, people lose their clear view of things. They are filled with thoughts and feelings. They find it difficult to prioritize and, as a result, they are very concerned about what is beyond their control, but they tend to avoid or ignore more pressing concerns that they can handle. Therefore, it is often helpful to help the patient organize his thoughts according to two kinds of goals - short-term and long-term. SHORT-TERM GOALS - to calm down, try to somehow deal with your strong fear, discuss what just happened, find shelter for the night, find something to eat, etc. LONG-TERM GOALS include long-term therapy, finding a job, finding permanent housing, etc. Crisis counselors need to be very ACTIVE and DIRECTIVE in helping patients sort out these two types of goals, and then giving very hands-on attention to achieving short-term goals and making a plan to achieve long-term goals. nine0003

Crisis counselors need to be very ACTIVE and DIRECTIVE in helping patients sort out these two types of goals, and then giving very hands-on attention to achieving short-term goals and making a plan to achieve long-term goals. nine0003

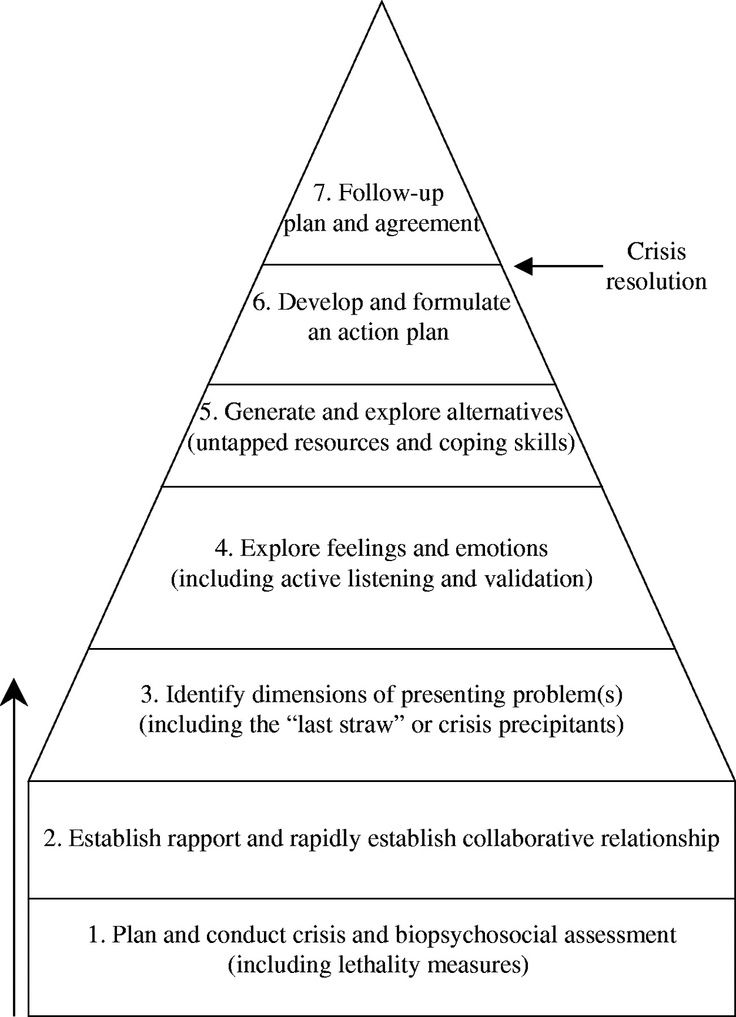

MAKING A PLAN

In a crisis, it is very difficult for a person to concentrate, think clearly, judge sanely and prioritize. It is often helpful to take notes during a conversation with a patient so that no information is missed, and to have a list to remind the counselor of what topics to cover during the interview. At the end of a session, it is often very helpful to actually WRITE A PLAN for the patient to follow, and let the patient go with that plan in hand. It is best to prepare such a plan with the patient, write it in legible handwriting, number all the points, and arrange it so that it is easy to read. It might sound like this:

1) If I am upset, I will talk to a counselor.

2) I will call my uncle to see if he can help me out within the next two weeks.

3) I will talk to my doctor about other asthma medications.

4) I will put myself on the list of people looking for affordable housing.

5) I will go to a recruiting agency.

STORY

A person develops symptoms of acute stress disorder if they are exposed to a traumatic situation that exceeds their ability to deal with the situation in their usual way. Accordingly, the symptoms serve to cover or conceal overwhelming undigested experiences. Crisis intervention is designed to: 1) help the patient tell their story, 2) help the patient distance themselves somewhat from the event in order to understand what happened, 3) put the experience into words, and 4) return the patient to their previous level of functioning. When telling the story of a traumatic experience, the patient may cry, laugh, yell, whisper, be silent for a while, think of other apparently unrelated losses, or be preoccupied with some part of the story that seems insignificant. The therapist should listen patiently and bring the patient back to his story. nine0003

nine0003

COMMON THEMES IN TRAUMA STORIES

In the process of putting traumatic experiences into words, we find several recurring clinical patterns (this list is by no means exhaustive).

1) People who are caught up in emotions and have difficulty speaking

2) People who, when talking about horrific events, do not express any emotion at all.

3) People who feel guilty because they survived this disaster when others died or suffered. nine0003

4) People who feel they somehow caused the disaster, or that they should have done something differently to save someone.

- When a person is overwhelmed with emotions, the counselor should help him calm down by taking him to a quiet place, offering him a glass of water, letting him "get over it" for a while, and then try to help him talk about what he is going through. Sitting quietly with the patient or letting him cry for a while is very helpful, but ultimately it will be important to help him try to express the inexpressible.

nine0098

nine0098 - For patients who are in a state of emotional numbness, the counselor can point out common feelings that most people might experience under similar circumstances and think with the patient about what feelings might be hidden from view. BUT it is also important to remember that emotional numbness serves to ward off overwhelming affect. It is important that the counselor respect the patient's defenses and allow time for the patient to allow the feelings associated with the experience to rise to the surface. Crisis counselors have learned over the years that some trauma survivors may appear well in the first days after a crisis, and then fall apart completely safe a couple of weeks later. nine0098

- Though counterintuitive, it is also very common for people to feel guilty about surviving a tragedy that others did not. The crisis counselor should watch for suicidality in these patients and help them mourn their loss by encouraging them to talk about the people and things they have lost.

Sometimes it can be helpful to ask a person if their loved ones who have died would like them to suffer or be happy in their later life. This usually shifts the focus from the survivor's guilt to the underlying grief. nine0098

Sometimes it can be helpful to ask a person if their loved ones who have died would like them to suffer or be happy in their later life. This usually shifts the focus from the survivor's guilt to the underlying grief. nine0098 - For those who feel that they may have caused a flood or earthquake in some way, or may have done something to save their family, it is important to be helped to realize how powerful the enemy they had to face was, to recognize the fear and confusion that moment, and again, to help them mourn their losses. After a person has told their story, it is often beneficial for them to tell it again and again and again and again. There is no need to tell patients this, but it is necessary to make them feel that they can freely tell their story again without feeling that they are boring people with the same story. The counselor can expect that with each presentation the story will grow in new detail and the pent-up affect will be further released. nine0098

END

Crisis counseling is by its nature very short term. Many interventions are completed in one session. It is important to run this session as a one-session treatment. If the consultant meets with the patient one more time, this is good, but it is useful to consider each session as an intervention in itself. Crisis intervention must end with a specific plan that the patient will follow. The plan must be written down and given to the patient. If the patient is a child, the plan should be given to an adult who cares for him or pasted on the child's card. The counselor should give the patient all the referrals that may be needed, and then the patient and therapist should say goodbye to each other. The therapist need not worry about being too neutral. It is normal for crisis counseling if the therapist expresses sadness and anger at the tragedy the patient has experienced, gives advice, and wishes the patient good luck. Although physical contact is avoided in psychotherapy, hugs are not uncommon in the midst of catastrophic events. Sometimes a comforting touch or hug can make a huge difference.

Many interventions are completed in one session. It is important to run this session as a one-session treatment. If the consultant meets with the patient one more time, this is good, but it is useful to consider each session as an intervention in itself. Crisis intervention must end with a specific plan that the patient will follow. The plan must be written down and given to the patient. If the patient is a child, the plan should be given to an adult who cares for him or pasted on the child's card. The counselor should give the patient all the referrals that may be needed, and then the patient and therapist should say goodbye to each other. The therapist need not worry about being too neutral. It is normal for crisis counseling if the therapist expresses sadness and anger at the tragedy the patient has experienced, gives advice, and wishes the patient good luck. Although physical contact is avoided in psychotherapy, hugs are not uncommon in the midst of catastrophic events. Sometimes a comforting touch or hug can make a huge difference. Although counselors need not be afraid to touch the patient, it is important to remember that the nerves of crisis patients are often exposed and too much physical positioning can be confusing. nine0003

Although counselors need not be afraid to touch the patient, it is important to remember that the nerves of crisis patients are often exposed and too much physical positioning can be confusing. nine0003

CHILDREN

B o Most of the above applies to children. The significant difference, however, is that when children tell their story, they are more likely to speak in the language of play and metaphors created by their imagination. Therefore, when meeting with a child who has had a traumatic experience, it is helpful to have a box of pencils and a pad of paper and/or more toys or dolls with you. With the help of paper and pencils, the child can DRAW A PICTURE and TELL A STORY, which will become a metaphorical reflection of his experiences. You should ask the child to draw whatever he wants and tell a story about it. To make it easier for the counselor to understand the metaphor, you can ask the child to talk about the picture. The counselor should not ask, “What is this?” Rather, ask, “What can you tell me about this?” “What happened before this scene that we see in the picture?” "What happens next?" It is often helpful to write down a story from a child's dictation. The counselor can then read the story to the child and the story can be worked through. In this way, the counselor and the child have the opportunity to start a dialogue about a monster, or a war, or a big beast, or any other metaphor that can be used to talk about the child's experiences related to his traumatic experience. If a child has flashbacks, or if a child wakes up from trauma-related nightmares, drawing pictures and telling a story can also be helpful techniques. When a child is given the opportunity to draw his dream and tell a story about it, this often makes him able to distance himself from this nightmare to some extent and cope with it a little better. If a child wakes up at night, awakened by a terrible dream, it would be useless to deny the existence of the monster he just saw! Instead, ask him to show you what he saw by describing it, acting it out, drawing a picture, or telling a story. The material often does not require interpretation. The counselor should simply allow the child to express what is on their mind and tell their story in detail, while the counselor continues to show interest and empathize with the affect.

The counselor can then read the story to the child and the story can be worked through. In this way, the counselor and the child have the opportunity to start a dialogue about a monster, or a war, or a big beast, or any other metaphor that can be used to talk about the child's experiences related to his traumatic experience. If a child has flashbacks, or if a child wakes up from trauma-related nightmares, drawing pictures and telling a story can also be helpful techniques. When a child is given the opportunity to draw his dream and tell a story about it, this often makes him able to distance himself from this nightmare to some extent and cope with it a little better. If a child wakes up at night, awakened by a terrible dream, it would be useless to deny the existence of the monster he just saw! Instead, ask him to show you what he saw by describing it, acting it out, drawing a picture, or telling a story. The material often does not require interpretation. The counselor should simply allow the child to express what is on their mind and tell their story in detail, while the counselor continues to show interest and empathize with the affect. If the child is having some difficulty getting started, the counselor may have the child draw a picture of the traumatic event, a house before and after a flood, trees before and after a fire, a house during an earthquake, and so on. TOYS AND DOLLS give the child the same opportunity to express his deepest feelings in metaphorical play. nine0003

If the child is having some difficulty getting started, the counselor may have the child draw a picture of the traumatic event, a house before and after a flood, trees before and after a fire, a house during an earthquake, and so on. TOYS AND DOLLS give the child the same opportunity to express his deepest feelings in metaphorical play. nine0003

CONNECTIONS, THEIR LOSS AND FINDING

We all know ourselves and enjoy this world through connections with people, places and things present in our lives. When these bonds are severed by fire, flood, or earthquake, children and adults are terrified not only by the events they have just experienced, but also by the disconnection from everything that once made up their world. In such a case, it is important to try to restore this world by grabbing onto whatever survived, including objects and memories. When working with children, it is often helpful to ask them to draw a picture and tell their story while the counselor takes notes. Later, the child can draw his house before and after the disaster, draw the people he lost, draw what he felt and how he feels now. The stories he tells can be held together by making a BOOK, which for the rest of his life may be the only thing a person has left of all that he has lost. nine0003

The stories he tells can be held together by making a BOOK, which for the rest of his life may be the only thing a person has left of all that he has lost. nine0003

Children need to feel at home where they are. If possible, designate a bed for your child, put his personal belongings in a bag, and provide him with a sense of consistency and consistency. Reassure him that you are doing your best to help him, but don't make promises you can't keep. Be honest. Help your child feel at home in his temporary shelter. The child will often be happy to have a toy of some kind that he can "hold on to" and that will help him maintain some sense of security during this otherwise chaotic time. If possible, it would be good to build some schedule into the daily routine in the shelter, this would act calmly. It may be helpful to invite the children to sit together and read stories to them. It can also be comforting for children to take turns talking to the group about their experiences of trauma - but be very careful here, as for some children this can further aggravate the condition. nine0003

nine0003

If possible, it would be good if the children had paper, crayons, pencils, toys, dolls, children's books and a safe place to play. Crisis counselors must be prepared for the fact that children will lose their mental balance as if for no reason at all. This is because when a child feels safe, he starts to let the memories and feelings come to the surface, and all of a sudden he may just burst into tears. Sometimes a word or action or some person can serve as a trigger, and memories and feelings suddenly burst into the soul. Children may experience insomnia, eating problems, aggressiveness, aloofness, eccentric behavior, and so on. In the beginning it is best to think of this as an expression of trauma, but in reality some of it may be a characteristic of the child resurfacing in the emergency setting of the shelter. nine0003

It is also important to remember here that among adults and children affected by a crisis, there are people with a wide variety of diagnoses - depressive, obsessive-compulsive, psychotic, drug addicts, mentally retarded, borderline patients, and so on. And in crisis situations, counselors will meet with them all. In a crisis, people often lose their heads and make a much worse impression than they usually do, but after a successful crisis intervention, they will be able to cope with the situation, adjust to the new reality and return to their previous level of functioning. nine0003

And in crisis situations, counselors will meet with them all. In a crisis, people often lose their heads and make a much worse impression than they usually do, but after a successful crisis intervention, they will be able to cope with the situation, adjust to the new reality and return to their previous level of functioning. nine0003

Finally, and this needs to be reiterated, crisis counselors should manage their workload and pace wisely so as not to be overwhelmed. If the counselor feels overwhelmed, he will need crisis intervention himself. I'm not kidding. In fact, crisis counseling for emergency professionals is becoming more and more common. While there is no shame in a crisis counselor needing crisis intervention, whenever possible we should try to avoid such overload. The crisis counselor must dose the workload, eat properly, rest properly, consult with colleagues, and discuss (with a colleague or supervisor) particularly stressful or disturbing cases. nine0003

Clinical Psychology - St.

Petersburg State University

Petersburg State University

This site uses cookies to collect statistics and analyze site performance. We are trying to improve our work, for this we have connected analytical tools. Please agree to the collection and processing of your metadata or disable cookies in your browser settings.

Level of study Specialist

Form of study Full-time

Duration of study 6 years

Description of the program

- The main educational program of the specialty "Clinical Psychology" is aimed at preparing a specialist for the future professional activity of a clinical psychologist, who is able to successfully solve psychological problems in various areas of healthcare, social, penitentiary and preventive practice, medicine and psychological science

- The purpose of mastering the specialty is to form knowledge in the field of theory, methodology and practice of clinical psychology, about the applied and interdisciplinary nature of clinical psychology, its contribution to the development of theoretical problems of general psychology, the theory and practice of medicine and health care.

The program includes the formation of skills and abilities of professional activity in the main areas of clinical psychology (pathopsychology, neuropsychology, psychology of somatically ill patients, prevention of conditions of neuropsychic maladaptation and socially significant diseases, prevention, mental hygiene and the formation of a healthy lifestyle, psychological counseling, psychotherapy and rehabilitation of patients ), mastering the methods of clinical and psychological research, as well as the theory and practice of psychological intervention when working with various contingents of patients (children and adults), people with borderline mental disorders, as well as with the healthy population

The program includes the formation of skills and abilities of professional activity in the main areas of clinical psychology (pathopsychology, neuropsychology, psychology of somatically ill patients, prevention of conditions of neuropsychic maladaptation and socially significant diseases, prevention, mental hygiene and the formation of a healthy lifestyle, psychological counseling, psychotherapy and rehabilitation of patients ), mastering the methods of clinical and psychological research, as well as the theory and practice of psychological intervention when working with various contingents of patients (children and adults), people with borderline mental disorders, as well as with the healthy population - The educational program was developed taking into account professional standards and the opinion of employers (professional communities) on the correlation between the competencies of graduates and labor functions in the field of professional activity

Basic training courses

- Clinical psychology: an introduction to the profession

- Clinical Psychodiagnostics

- Clinical psychology in expert practice

- Neurotic and personality disorders

- Neuropsychology

- General psychology

- General Psychological Workshop

- Pathopsychology

- Psychological assistance in crisis situations

- Psychological counseling

- Psychology of addictive behavior

- Psychology of impaired development

- Developmental psychology

- Family Psychology and Family Psychotherapy

- Psychosomatics

The program includes a wide range of elective disciplines that contribute to the student's self-determination in psychology in the following areas:

- Psychological diagnostics and psychological intervention in clinic

- Mental health and early support for children and parents

- Health psychology

- Psychology of crises and extreme conditions

- Forensic and criminal psychology

Benefits of training

- Continuous six-year education, including one year of practical training with individual and group supervision, meeting international requirements for entry into individual psychological practice

- A unique program that combines the traditions of training clinical psychologists, laid down by the classic of Russian and Soviet medical psychology V.

N. Myasishchev, and the developments of modern scientists and practitioners

N. Myasishchev, and the developments of modern scientists and practitioners - The program combines deep theoretical training and development of practical skills (including at various clinical sites of St. Petersburg State University, medical and social institutions of St. Petersburg) in the main areas and directions of modern clinical psychology - pathopsychology, neuropsychology, health psychology, psychology of the somatically ill , psychotherapy, psychological counseling, social rehabilitation, prevention of behavioral disorders and socially significant diseases, as well as in the field of psychological expertise, early intervention and psychological support for children and parents

- Significant attention in the training program is paid to the issues of methodology and the development of specific methods of psychological diagnostics and psychological intervention, both in the clinic and in counseling practice, which are taught under the supervision of experienced teachers and qualified psychologists-practitioners

- Graduates are eligible for EuroPsy certifications, the European professional qualification standard adopted by the European Federation of Psychological Associations (EFPA), to practice independently

- Opportunity to participate in unique international events for students and young scientists — Winter School of Psychology, conferences "Ananiev Readings", "Psychology of the 21st Century"

Famous teachers

- O.

Yu. Shchelkova — Head of the Clinical Psychology Program, Doctor of Psychology, Professor, expert of the Russian Science Foundation (RSF), coordinator of the working group on Clinical Psychology of the Federal Educational and Methodological Association for Psychological Sciences under the Ministry science and higher education of the Russian Federation, expert of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS), author of more than 250 papers in the field of clinical psychodiagnostics

Yu. Shchelkova — Head of the Clinical Psychology Program, Doctor of Psychology, Professor, expert of the Russian Science Foundation (RSF), coordinator of the working group on Clinical Psychology of the Federal Educational and Methodological Association for Psychological Sciences under the Ministry science and higher education of the Russian Federation, expert of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS), author of more than 250 papers in the field of clinical psychodiagnostics - V. A. Ababkov - Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, author of more than 150 in the field of neurotic disorders and psychotherapy, awarded the badge of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation "Excellent Health Care"

- E.D. Balin – Doctor of Psychology, professor, one of the founders of the electrophysiological complex and the laboratory of psychophysiology at the Faculty of Psychology of St. Petersburg State University, the author of more than 200 works in the field of psychophysiology and theoretical psychology, was awarded the St.

Petersburg University commemorative medal

Petersburg University commemorative medal - N. L. Vasilyeva — Doctor of Psychology, professor, full member of the International Psychoanalytic Association (IPA), training analyst at PIEE (Psychoanalytic Institute for Eastern Europe), honorary president of the St. Petersburg Society for Child Psychoanalysis, member of the editorial board of the international journal Journal of Child Psychotherapy

- G. L. Isurina — Candidate of Psychological Sciences, Associate Professor, one of the creators of personality-oriented (reconstructive) psychotherapy, author of more than 180 works in the field of theory, methodology and practice of psychotherapy, member of the coordinating council of the Russian Psychotherapeutic Association, has the title of “Honorary Worker of the Higher vocational education of the Russian Federation"

- E. B. Karpova — Candidate of Psychological Sciences, Associate Professor, author of more than 120 works in the field of theory (psychology of relationships) and practice of clinical psychology, including articles in the "Psychotherapeutic Encyclopedia", textbooks and manuals on psychodiagnostics, psychosomatics, psychology of extreme states and mental trauma

- I.

I. Mamaichuk - Doctor of Psychology, Professor, author of more than 200 works, including textbooks and manuals on child clinical psychology, psychological assistance to children and adolescents with developmental problems, as well as psychological expertise, has the title of "Honorary Worker of Higher Professional Education RF"

I. Mamaichuk - Doctor of Psychology, Professor, author of more than 200 works, including textbooks and manuals on child clinical psychology, psychological assistance to children and adolescents with developmental problems, as well as psychological expertise, has the title of "Honorary Worker of Higher Professional Education RF" - R. Zh. Mukhamedrakhimov — Doctor of Psychology, professor, member of the Interdepartmental Working Group on the organization of the system of early assistance and support for children and adults with disabilities, as well as their families under the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection of the Russian Federation, member of the Council for Prevention and Intervention of the European Federation of Psychological Associations (European Federation of Psychologists Associations Board of Prevention and Intervention), a member of the World Association for Infant Mental Health (World Association for Infant Mental Health), the author of about 200 works in the field of developmental psychology and clinical psychology, has the title of "Honorary employee of higher professional education of the Russian Federation"

- E.

V. Pestereva — Candidate of Psychological Sciences, Associate Professor, Leading Specialist in Oncopsychology, Member of the Association of Oncopsychologists of the North-West, Winner of the XXI National Competition "Golden Psyche" in the nomination "Psychological Instruments of the Year": project "Children in a Situation with Cancer: Life Goes On" (2020 ), author of more than 70 scientific publications

V. Pestereva — Candidate of Psychological Sciences, Associate Professor, Leading Specialist in Oncopsychology, Member of the Association of Oncopsychologists of the North-West, Winner of the XXI National Competition "Golden Psyche" in the nomination "Psychological Instruments of the Year": project "Children in a Situation with Cancer: Life Goes On" (2020 ), author of more than 70 scientific publications - N. S. Khrustaleva - Doctor of Psychology, Professor, Leading Specialist in the field of psychology of migration, Head of the Center for International Projects and Programs of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, has the title of Honorary Worker of Higher Professional Education of the Russian Federation and Honorary Professor of the Faculty of Psychology of Moscow State University them. M.V. Lomonosov

- A. V. Shaboltas — Doctor of Psychology, Professor, Dean of the Faculty of Psychology, a leading specialist in the field of health psychology, including the development and longitudinal evaluation of preventive interventions in the field of HIV / AIDS prevention and risk behavior, expert of the World Health Organization (WHO ) on the ethics of research in vulnerable groups, member of the presidium and chairman of the Ethics Committee of the Russian Psychological Society, member of the Ethics Council of the European Federation of Psychological Associations from Russia, member of the European Association for Health Psychology, member of the coordinating council of the Russian Psychotherapeutic Association and the St.

Petersburg Psychological Society, expert of the Russian Academy of Sciences

Petersburg Psychological Society, expert of the Russian Academy of Sciences

International Relations

- Vilnius University, Lithuania

- Yale University, USA

- Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway

- Aarhus University, Denmark

- Plovdiv University named after Paisiy Hilendarsky, Bulgaria

- University of Zaragoza, Spain

- Sofia University named after St. Kliment Ohridski, Bulgaria

- University of Beira Interior, Portugal

- Vytautas the Great University, Lithuania

- University of Delaware, USA

- University of Minho, Portugal

- University of Portsmouth, UK

- University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain

- Tohoku University, Japan

- University of Houston, USA

- University of Edinburgh, UK

- Jagiellonian University, Poland

Internship and future career

Places of internship

- St.

Petersburg Research Institute of Emergency Medicine named after I.I. Janelidze

Petersburg Research Institute of Emergency Medicine named after I.I. Janelidze - city psychiatric hospitals

- Children's City Hospital No. 2 of St. Mary Magdalene

- children's home

- crisis and rehabilitation centers

- public organizations and foundations that help people with various difficulties in the field of health and social adaptation

- Research Institute of Pediatric Oncology, Hematology and Transplantation named after Gorbacheva First St. Petersburg State Medical University named after Academician I.P. Pavlova

- neuropsychiatric dispensaries

- St. Petersburg State Budgetary Institution of Health Care "City Narcological Hospital"

- North-Western Branch of the Federal State Institution "Center for Emergency Psychological Assistance of the Ministry of the Russian Federation for Civil Defense, Emergency Situations and Elimination of Consequences of Natural Disasters"

- Psychological Clinic of St.

Petersburg State University

Petersburg State University - special institutions of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation, Main Directorate of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation

- helplines and online counseling services

- institutions of the Federal Penitentiary Service for St. Petersburg and the Leningrad Region

- Federal State Budgetary Institution "National Medical Research Center named after V.A. Almazov" of the Ministry of Health of Russia

- V. M. Bekhterev National Research Medical Center for Psychiatry and Neurology

- Federal Center for the Prevention and Control of AIDS and Other Infectious Diseases

- specialized institutions and correctional centers of the Federal Penitentiary Service of the Russian Federation

- health and fitness clubs, rehabilitation treatment center

- centers for psychological diagnostics and medical and psychological rehabilitation of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation

- centers of social and psychological assistance to the population

List of key professions

Training of professionally competent specialists ensures the competitiveness of graduates in the field of psychological diagnostics, examination and psychological assistance to citizens in healthcare, education, social protection institutions, public and economic organizations, administrative and law enforcement agencies

- Clinical psychologist

- Medical psychologist

- Psychologist

- Educational psychologist

- Consultant Psychologist

- Psychologist of emergency psychological services

- Psychologist in the field of social assistance

Organizations where graduates work

- Medical institutions of various profiles

- Psychological services of law enforcement agencies (Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia for St.