Crazy bipolar stories

'Certified Crazy': My Sister's Struggle Living With Bipolar Disorder

I remember the hot and extremely humid Saturday afternoon in Puerto Rico when my mom and I found my sister lying on the floor of her room in fetal position, her head tilted slightly upward, staring at one of the perfectly hand-painted shocking pink walls of her room. Bubbles of drool were coming out of her mouth, and her gaze was lost and downright frightening. We’d heard her weeping like a 2-year-old whose sabanita (blankie) was lost forever, which prompted my mom to run to her rescue — a scene that had become far too familiar for our family.

But this time was different: My sister was inconsolable. She wouldn’t move, blink, or speak. We sat next to her for a few minutes … or was it hours? I’m not exactly sure, as time felt meaningless at that moment.

She was only 17.

As a writer used to editing while typing, I think and process my emotions in words. Often, I choose one word to summarize the feeling, the experience. Bizarre is the word for this day; it was — without a doubt — the most bizarre day yet of my then 15-year-old life. My big sister was acting weird, and we couldn’t do anything to help her.

The days that followed this “episode” were somber, sad, and full of silence and tears. The morning following the episode, we drove my sister to the hospital, where she remained under observation for two weeks. I remember my mom calling pretty much every psychiatrist in San Juan during that time, as well as my father, her sister, and, lastly, my grandmother, with whom she shared what she thought was going on with my sister. “She is sick. She wants to quit architecture school. I’m scared,” I overheard her say while eavesdropping.

This time was different: My sister was inconsolable. She wouldn’t move, blink, or speak.

My sister was only 16 when she was accepted to the University of Puerto Rico School of Architecture, which admitted just 30 students per year after a rigorous application process that included artwork, endless interviews, and three or four tedious exams. Of course, my always-brilliant big sister passed them all with A-pluses.

Of course, my always-brilliant big sister passed them all with A-pluses.

When she started at the university, she was the youngest person in the class once again. My mom — and especially my dad — always bragged about how she spoke her first words at 11 months, started at a Montessori preschool at age 2, and by first grade could read a book from cover to cover and knew all her multiplication tables by heart. When the time came for her to enroll in second grade, the teachers highly recommended that she be “jumped” to third grade right away. She was way too smart for second grade.

Here Comes the Diagnosis

We were allowed to visit my sister at the hospital only after a full week had passed. As soon as we got out of my mom’s car the day of that first visit, I felt this unbearable pressure on my chest. The sign read “Hospital San Juan Capestrano,” and it was surrounded by beautiful tropical landscaping and a few flame trees with fire-red flowers. Inside, the waiting area had soft pink and beige walls, and the staff was friendly — almost compassionate.

It was obvious that my mom hadn’t slept in 10 days. My dad was making stupid jokes to calm his nerves. This was the first time both of my parents had been in the same room since their divorce 10 years prior. My sister was waiting for us behind a glass window. We went in one by one, as requested by her on her visitor’s list. We only had two hours total, so we had to be quick and clever. Saying the wrong thing at the wrong time could be extremely detrimental to her recovery.

A team of doctors, two of them female, came to the visitors’ room after my sister was sent back to her “cocoon,” as she referred to the psychiatric ward she was in. They confirmed our suspicion: She had type 1 bipolar disorder.

My big sister, as she later jokingly referred to herself, was “certified crazy.”

More About Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar Disorder Symptoms and Diagnosis

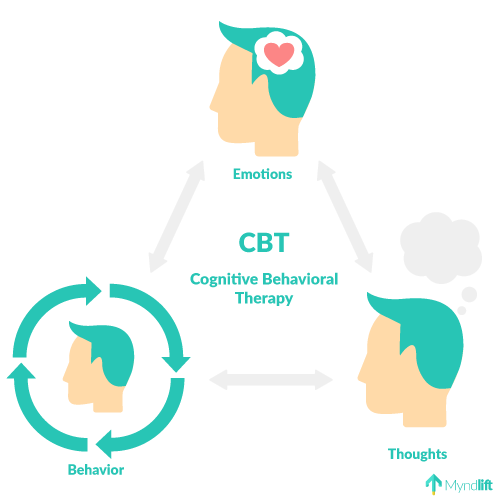

Speculation immediately followed our visit, as we tried to figure out how to process this diagnosis and figure out what the best treatment for her would be. Lithium, the doctors all recommended. But my sister couldn’t bare the side effects of this strong medicine, despite all the studies that prove it to be the most effective in helping patients balance their mood swings.

Lithium, the doctors all recommended. But my sister couldn’t bare the side effects of this strong medicine, despite all the studies that prove it to be the most effective in helping patients balance their mood swings.

Genetics quickly came to mind as one of the possible causes — one more unfortunate piece of my sister’s “misery team,” as we liked to call it. “Your grandfather was schizophrenic,” my mom reminded us. And my father’s dad, a veteran, was brilliant and had an impeccable sense of humor — just like my sister. One of the most discussed family stories was that he came back from Korea “crazy.”

His family had certified him as crazy.

My poor abuelo hated being exposed to electric shock therapy back in the day. A safer form of the practice, now called electroconvulsive therapy, is still being used to counteract severe depression, treatment-resistant depression, severe mania, catatonia, and in some rare cases, severe and difficult-to-treat agitation and aggression in people with dementia.

Life After the Diagnosis

The next two decades were full of ups and downs; crises; two more hospitalizations; a few suicidal moments that luckily resulted in aborted missions, thanks to the vigilant efforts of my younger sister, my mother, and me; insomnia; stress; and more than 40 different psychiatrists.

Related Conditions

Why Can’t I Sleep? Insomnia Explained

My sister didn’t like therapy at all. She’d always say that she ended up telling the doctors more about her condition rather than the other way around. The level of misunderstanding and stigma combined with the lack of both answers and treatment options — options that would make those ghosts in her head go away for even just a bit — kept the whole family in a perpetual state of frustration. Not to mention our fear of genetics. Research shows that as a sibling, I am 10 times more prone to develop bipolar disorder than someone without an affected sibling.

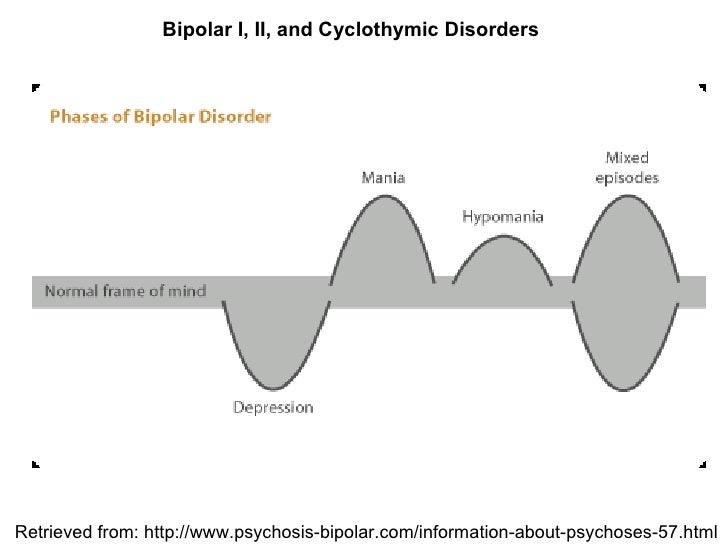

But even at my craziest and darkest times, I can say I have never experienced depression or mania, the two main components of bipolar disorder, in my life — at least not in the way my sister did. I consider myself blessed but don’t take my own mental health for granted for a second.

I consider myself blessed but don’t take my own mental health for granted for a second.

As I was writing this story, I called my mom to help me relive some of the most somber moments with my sister. I wanted to document them as they'd felt at the time. Her response was: “Please make sure whoever reads this article understands that your sister’s breast cancer diagnosis was nothing compared to her bipolar disorder diagnosis. Bipolar disorder really shaped her destiny.”

In 2007, at age 30 — right after she’d bought her first apartment by herself, finished remodeling it with the help of our father, and had been with a steady boyfriend for three years — her body joined the “misery team” her mind had successfully founded 13 years earlier.

My “certified crazy” big sister ALSO had breast cancer.

Another genetic disorder was confirmed to all of us when my sister learned that she was BRCA2 positive. (Two of our aunts have had different forms of breast cancer, which puts us at increased risk. ) I have chosen to never be tested for the BRCA2 gene mutation, though, mostly because my mom couldn’t bear having another diagnosis in the family. My sister's battle — actually, to be precise, OUR battle — with cancer lasted seven long and incredibly fulfilling years.

) I have chosen to never be tested for the BRCA2 gene mutation, though, mostly because my mom couldn’t bear having another diagnosis in the family. My sister's battle — actually, to be precise, OUR battle — with cancer lasted seven long and incredibly fulfilling years.

I had moved to New York City by this point, so I flew down to Puerto Rico at least every other month to be with her and my mom, to take her to her endless chemotherapy appointments, and to be there when she woke up from each of her five invasive surgeries. We tried it all! We did what every loving family facing this tragedy does: We had her back.

Related Conditions

Signs and Symptoms of Depression

What happened to her mind while her body was weakening over the course of those seven years is still beyond our belief. She experienced no major mental crises during this time (other than a bunch of tears and fear associated with the cancer treatment, of course), took no depression meds, and had zero visits to the psychiatrist; she didn’t need the treatments. It was almost as if her body and her mind signed an agreement to let her lead as ordinary a life as possible despite her illnesses, and the disclaimer stated: “Valid for at least seven years.”

It was almost as if her body and her mind signed an agreement to let her lead as ordinary a life as possible despite her illnesses, and the disclaimer stated: “Valid for at least seven years.”

Her mind gave her a break for the very first time.

While she was never truly in remission from her cancer, her mental state was okay. Her mood swings were under control, and she was determined to win the cancer battle — and smiled more than I could remember since her bipolar disorder diagnosis. I call this period our beauty within the tragedy.

Then May 16, 2014, happened.

My sister’s cancer had spread to her lungs, and on this day, her body succumbed to the disease. As her body shut down, her last words to me were loud and clear. So was her mind. “Take care of our baby nephew. Buy him a bunch of candy, and let him do whatever he wants. And you always be yourself and never let anyone put you in a box like they did to me. I am proud to be certified crazy, but you are not crazy. ”

”

Her name is Ana. She lived a functional life even after cancer joined her “misery team.” She had a steady job, friends who loved her and understood where she was coming from when she acted weird, a new boyfriend basically every other year, and a loving family. She was pretty and funny as hell. She collected records and movies and was capable of dismantling and remaking a computer from scratch. She was the most brilliant person I have ever met. She died at age 37. Way too young! And I choose to remember her — every day of my life — simply as my big sister. The best one I could have ever asked for.

Our favorite movie was The Intouchables. On the day that we watched it for the seventh time, Ana confessed that she loved it because the relationship between the main characters (a paraplegic and his unexpectedly nice caretaker) reminded her of ours. The caretaker never looked at his patient as a sick person but simply as a guy who needed to have fun and feel normal for a bit. That was a great day. But I wasn’t always compassionate and caring with her. It took me years to accept that my big sister was sick. To be honest, I will never fully understand why she had to suffer so much.

That was a great day. But I wasn’t always compassionate and caring with her. It took me years to accept that my big sister was sick. To be honest, I will never fully understand why she had to suffer so much.

My hope is that with the research experts are conducting, they will be able to more precisely decipher what bipolar disorder is all about and figure out how to make patients’ lives less secluded and lonely. As more brave souls like Catherine Zeta-Jones, and more recently, Mariah Carey

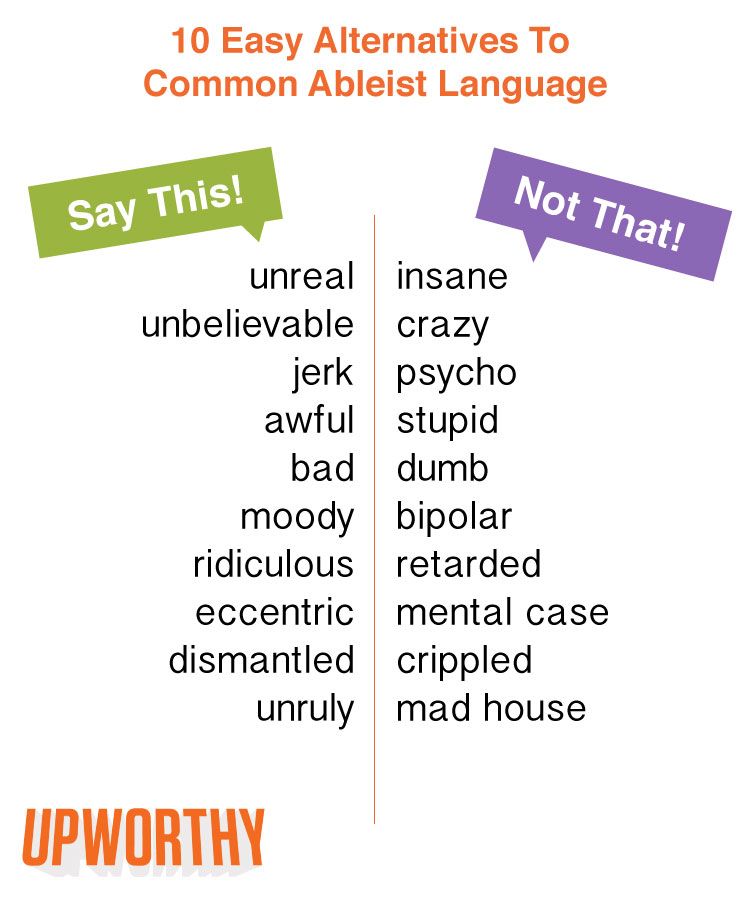

come forward and tell their stories of living with this disease, bipolar disorder will hopefully shed some of its stereotypes as a crazy person’s disease.

Meanwhile, I have not only bought our nephew all the candy he wants, but my younger sister and I make sure he knows his Auntie Ana is watching him from heaven and protecting his every step.

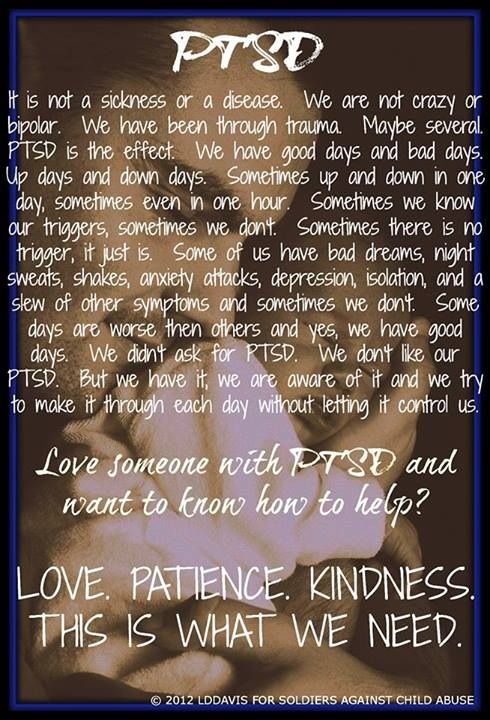

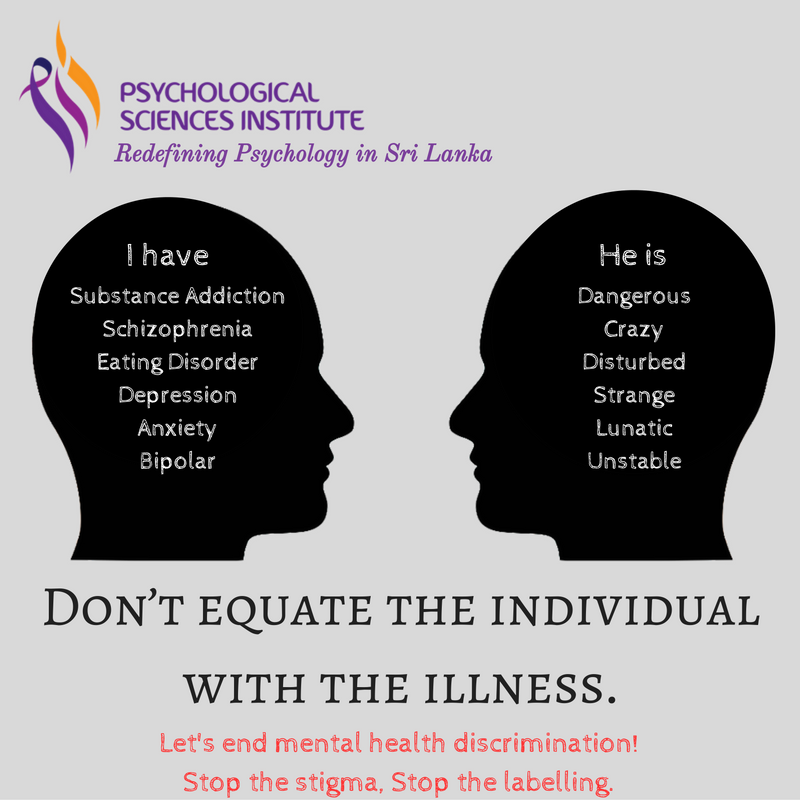

Bipolar disorder is not the enemy. The worst part of this terrible condition is the stigma it carries, as do all mental disorders. There needs to be more compassion and understanding. I strongly believe that putting a face to bipolar disorder helps humanize our “certified crazy” in the eyes of our “not certified crazy” world. Like Ana would always tell me: “I’m not the crazy one. I see what others can’t. We are just humans fighting to fit in this crazy world.”

There needs to be more compassion and understanding. I strongly believe that putting a face to bipolar disorder helps humanize our “certified crazy” in the eyes of our “not certified crazy” world. Like Ana would always tell me: “I’m not the crazy one. I see what others can’t. We are just humans fighting to fit in this crazy world.”

That’s my sister.

Resource We LoveDepression and Bipolar Support Alliance

This organization aims to promote wellness among people who have mood disorders, especially depression and bipolar disorder. Check out its Wellness Toolbox and listen to its podcasts.

International Bipolar Foundation

Founded by four parents with children impacted by bipolar disorder, the International Bipolar Foundation seeks to increase awareness of mental health conditions and supportive connections for people touched by bipolar disorder. Learn more about its support resources.

BPHope

BPHope, the award-winning online community of BP Magazine, works to increase public knowledge about bipolar disorder and empower members of the bipolar community.![]() Take a look at its resources for caregivers, and subscribe to its print or digital magazine.

Take a look at its resources for caregivers, and subscribe to its print or digital magazine.

Our stories - Bipolar Life Victoria

“I freaked out and told Dad I wasn’t feeling that good. We eventually drove to the hospital and I was admitted to the psych ward for another week.”

read more

“Although the documentation was limited, it did confirm an interesting entry notated by the R.C.H Psychiatrist. It said “I predict manic depressive disorder in adulthood” (manic depressive disorder is what Bipolar used to be called several years ago). This observation was made when I was 12 years old.”

read more

“Initially I was diagnosed with Post Natal Depression 19 years ago, shortly after I had my first daughter. The diagnosis changed later to Clinical Depression and about 6 years ago my psychiatrist of 15 years diagnosed me with Bipolar 2. ”

”

read more

“So when my brain fell into full blown psychosis – with delusions and grandiose thoughts, fearful thoughts about loved ones and being in danger and a complete change in rational perception – it ripped apart the fabric of my life and all I knew. I am writing this to explain what psychosis is really like.”

read more

“A year later, a series of events led me to become manic and psychotic: my relationship ended, I moved house, I experienced bullying at work for four years, was promoted and I needed to have my nose reconstructed following a sporting injury.”

read more

“It really, really hurts to be ‘in sane’. Even for a second. It hurts more than anything has ever, ever, ever hurt before or ever, ever will. It is the most confusing utterly terrifying thing in the whole wide world. ”

”

read more

“At times, living with depression and anxiety feels overwhelming and life feels hopeless. I have tried 13 different psychiatric medications and currently take four. I’m on my fourth long-term individual therapist.”

read more

“The breakthrough came in early 2018. Chris was put under the professional care at the Melbourne Clinic and he was given TMS. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation(TMS) is a noninvasive procedure that uses magnetic fields to stimulate nerve cells in the brain.”

read more

“I now realize that the terror was masking anger, an anger so deep and so corrosive I couldn’t even acknowledge it. It was at this point that I stopped sleeping altogether – or so it seemed to me.”

read more

“Find a group, even if it’s online, go as often as you can because I reckon this is as important as taking the drugs or getting enough sleep. ”

”

read more

“NO! Just flat out no, we do not suddenly lose our identity at the diagnosis of a mental health problem.”

read more

“I’ve had E.C.T. twice. In those instances, it was the only thing that worked on the psychosis (medication was not enough). I would recommend E.C.T. if you get offered it. I originally fought it but I realize now that it was the best thing for me.”

read more

5 books about bipolar disorder

21,194

This collection is addressed not only to those who have been diagnosed with this affective disorder, and there are many such people - there are more than 2 million of them in Russia alone, but also to everyone who wants to better understand their “ bipolar” friends and acquaintances, people who live as if on a rollercoaster – now experiencing ecstasy and “flights of the mind”, now plunging into darkness and impotence.

These books will help you to know yourself better, because each of us is different in some ways.

1. “A restless mind. My Victory Over Bipolar Disorder Kay Jamison

Kay Jamison is a psychiatrist and professor at Johns Hopkins University who has written several books on affective disorders, but this book is unique in that Kay talks about his personal experience. At the height of her scientific career, she realized that she herself suffered from a severe form of bipolar disorder. Nevertheless, she managed to create a clinic for the study of affective disorders and become a well-known specialist in this field. The reader will learn a lot about the causes of bipolar disorder, the history of the study of the problem and the methods of treatment. But first of all, about how you can live without giving up. Overcoming bouts of mania and then debilitating depression, Kay Jamison was able to make a serious contribution to the development of psychiatry and set an inspiring example for her patients. (Alpina Publisher, 2017)

(Alpina Publisher, 2017)

2. “Confessions of a Normal Mad Woman” Olga Marinicheva

Turning a case history into a life story, Olga Marinicheva (who took the pseudonym Marina Zarechnaya) tells about unprecedented and unbearable love, visions and hallucinations, psychiatric hospitals and the fate of an entire generation. “Sometimes, in order to save the soul, she is forced to go into psychosis,” she writes in her poignant book. A diary, an autobiography, a human document (“human – and thanks for that,” the author comments on this characteristic) – it is impossible to determine the genre of this book. The text, like the life of the heroine herself, crumbles into fragments, but each page is filled with the talent of the author - a well-known journalist, writer and teacher. She knows very well why this book was written: “Now I just have nowhere but words,” and gives the reader a unique opportunity to see the experience of bipolar disorder described “from the other side”, from the inside. (Inapress, Novaya Gazeta, 2006)

(Inapress, Novaya Gazeta, 2006)

3. “Go crazy! A Guide to Mental Disorders for a City Resident Daria Varlamova, Anton Zainiev

Graduates of the Higher School of Economics, journalists Daria Varlamova and Anton Zainiev talk in a fascinating and accessible way about the most common mental disorders: depression, anxiety and bipolar disorders, schizophrenia and others. They also describe the methods of treatment, never getting tired of repeating: it is dangerous to use them on your own, without a visit to the doctor, and it is unlikely that it will work: you will need a psychiatrist's prescription to buy drugs. Most diseases do not impose special restrictions on life - no need to go on a diet, leave work, take toxic drugs and give up extreme entertainment. And at the same time, learning about your diagnosis is a great relief. “I perceived my problems with depression as personal shortcomings,” says Daria Varlamova. – I considered myself lazy, useless, useless. Knowing that you are sick and can be cured means that you can stop the destructive self-flagellation and start taking action. ” (Alpina Publisher, 2016).

” (Alpina Publisher, 2016).

4. “Bipolar People: How People with Bipolar Disorder Live and Dream” Masha Pushkina

Journalist, editor of the bipolar.su portal Maria Pushkina has collected several personal stories – frank confessions of people with bipolar disorder. Among her heroes are the mathematical engineer Mikhail, who suffered his first attack of illness at the age of 25, and 35-year-old Asya, a graphic designer. Nastya, who fell in love with a man with the same diagnosis... They talk about how they first realized that they were sick, at what point they decided to seek help, and how they eventually learned to live with the disease. The characters' monologues are commented on by experts, psychiatrist and psychologists. They explain how to recognize the disease and what rules to follow in order to remain prosperous and productive. (Publishing Solutions, Ridero, 2017)

5. “Bipolar Toolkit”

Australian journalist and lawyer Sarah Freeman was diagnosed with bipolar disorder at the age of 40, but she managed to stabilize her condition, firstly, with the help of a diet, about which she wrote the book “The Bipolar Diet” (“ The Bipolar Diet, 2009), and secondly, using behavioral strategies aimed at developing awareness. Sarah Freeman details these strategies in a practical guide. There are only three of them: maintaining a mood chart, drawing up a recovery plan, and preparing a treatment agreement. The brochure is addressed to those who understand that therapy is the responsibility of not only the doctor, but also the patient. You can download the book for free here: http://bipolar.su/2016/06/instrumentarij-bipolyarnika-polezn/

Sarah Freeman details these strategies in a practical guide. There are only three of them: maintaining a mood chart, drawing up a recovery plan, and preparing a treatment agreement. The brochure is addressed to those who understand that therapy is the responsibility of not only the doctor, but also the patient. You can download the book for free here: http://bipolar.su/2016/06/instrumentarij-bipolyarnika-polezn/

Text: Alla Anufrieva Photo source: Getty Images

New on the site

How to live longer: scientists have discovered a new psychological factor underwear, if only I see it? ”: how to live with a stingy man

How to save yourself and help a loved one who returns with SVO

Test: Barratt Impulsivity Scale - what is your specialty?

“A DNA test led to an unexpected reunion”: how Natalia Vodianova found her younger sister 22 years later

“I always worry that my 15-year-old daughter will not be able to cross the road near the school” and learn to be in trend with him

Genius and mental disorder - is there a connection?

- Claudia Hammond

- BBC Future

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter to help you understand what's going on.

Image Credit, iStock

Everyone can name a lot of famous people who had enormous creative potential and also suffered from mental illness - take Vincent van Gogh, Virginia Woolf, Tony Hancock or Robin Williams. There are so many examples that the existence of a certain connection between an unhealthy psyche and creative abilities seems obvious.

But the question is: is this seemingly generally accepted opinion supported by research data? It turns out it's not so simple, the browser found BBC Future.

In fact, there is surprisingly little reliable data on this subject. Of the 29 studies conducted up to 1998, 15 found no relationship between these phenomena, while in another nine cases such a relationship was found, and in the remaining five it was considered indeterminate.

This can hardly be considered a confirmation of the direct relationship between mental illness and creative abilities.

- Other BBC Future articles in Russian

Moreover, some of the studies were based on simple comparison of cases encountered in practice, rather than on serious attempts to determine the presence of a causal relationship.

One of the difficulties is that it is not so easy to define or measure creativity, so scientists often use alternative indicators.

For example, in a study conducted in 2011, participants were classified simply by occupation, based on the fact that every artist, photographer, designer or scientist necessarily has creative potential, regardless of what exactly their work consists of .

Using data from the official Swedish census, researchers have found that people in these creative professions are 1.35 times more likely to have bipolar disorder (formerly known as manic-depressive illness), but have symptoms of anxiety, depression, or schizophrenia to the same extent as those of specialists from other fields.

Image copyright iStock

Image captionIs there a link between mental illness and creativity, or is it a myth?

Because of this simplistic division, it is difficult to say whether these data mean that creative professionals are more at risk of bipolar disorder than others, or that the disease is unusually rare in, say, accountants.

In favor of the presence of interdependence between these phenomena, the results of a study published in 1987 by the American psychiatrist Nancy Andreasen are most often cited.

This study compared 30 writers and the same number of people from other professions. There were more people with bipolar disorder among writers.

Skip Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it is important and what will happen next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

However, the sample was very small - only 30 writers were interviewed over 15 years - and although this study is often cited, it has been criticized due to the fact that the diagnosis of mental disorders was carried out simply on based on conversation and in the absence of clear criteria (see a comprehensive discussion of this and other frequently cited studies in the work of the American psychologist Judith Schlesinger).

In addition, the conversation was conducted by people who knew which of the participants was a writer, which could affect the results.

Moreover, the authors decided to visit a sanatorium for writers seeking solitude, so it is possible that there were precisely those participants in the study who were known to experience anxiety.

Even if we take the results for granted, they say little about the causal relationship between these phenomena.

Whether the research data means that the alleged increase in creativity as a result of bipolar disorder encouraged writers to choose this profession, or that the symptoms of the disease prevented them from finding regular work is difficult to judge.

In support of the thesis about the existence of a connection between mental disorder and creativity, the results of two more studies are often cited.

The first of these was carried out by the American psychologist Kay Redfield Jamison, who gained fame as the author of the fascinating book "The Restless Mind". Image credit: iStock artists. It was attended by 47 people, but there was no control group, so you can only compare its results with the average among the population.

Jamison found an unusually high rate of psychiatric disorders among the participants. For example, half of the poets at least once sought treatment.

Sounds impressive, but, as critics have noted, we are talking about only nine respondents.

Another study involving a much larger number of people was conducted by the American psychiatrist Arnold Ludwig.

He studied the biographies of more than a thousand celebrities in search of references to mental disorders and found that the symptoms of disorders differ depending on the profession.

The problem here was that while famous people (eg Winston Churchill and Amelia Earhart) are undeniably exceptional, strictly speaking they are not necessarily exceptionally creative.

Although this extensive study is often cited as an example of such a relationship, Ludwig himself admits in his work that he did not establish that mental illness is more common among outstanding personalities, nor that they are a necessary condition for exceptionalism.

Apparently, the phenomenon of outstanding personalities is of keen interest to scientists, but studies on this topic do not always give the same results.

In 1904, the English physician Havelock Ellis studied more than a thousand people and found no relationship between mental illness and genius.

A similar conclusion was drawn from a study of 19,000 German artists and scientists over a three-century period.

It should be noted, however, that these studies have an important drawback: they are based on the assumption that biographers knew about the presence of mental disorders in the heroes of their books and mentioned this fact.

But if there is little or no evidence at best, why then has this belief taken hold?

One reason is that it seems intuitively that the out-of-the-box thinking or the surge of energy and determination that can be characteristic of a manic state can create a creative mood.

Some argue that the relationship between mental illness and creativity is more complex, that mental disorders allow people to think more creatively, but when the disease flares up, creativity drops to an average level or below.

Of course, sometimes mental health problems can prevent a person from realizing his plan at all. During periods of depression, motivation quickly declines.

During periods of depression, motivation quickly declines.

Image copyright, iStock

Image caption,Even if there is a relationship between mental illness and creative energy, the cause and effect relationship between the two is unclear

in themselves, these characteristics usually attract attention.Lebanese psychologist Arne Dietrich offers an interesting explanation for this phenomenon, based on the "availability heuristic" theory formulated by Nobel Prize-winning Israeli-American psychologist Daniel Kahneman.

The theory says that people tend to focus on what is directly in front of them.

Stories about how Van Gogh cut off his ear in a fit of madness, and decades of debate about what was or was not then, make us vividly imagine this story.

However, in our imagination there are no similar stories about artists who lived happily ever after.

We tend to estimate the probability of an event occurring based on how easily we can imagine it.

And if you ask any person about whether there is a connection between genius and mental disorder, he will immediately come up with many examples in favor of this thesis.

It is possible that the belief in the existence of such a relationship may have certain negative consequences.

Some people feel that the disease really promotes creativity, and for this reason they even refuse to take medicine, fearing, for example, that they will lose their special abilities.

But isn't there a risk of mistakenly attributing one's creative successes to the disease, and not to one's own talents?

And what about those who suffer from a mental disorder, but do not notice any special talents in themselves? Will they not, after hearing such statements, believe that they simply have to do something exceptional, and worry if they fail to do so?

I think that ultimately the popularity of this belief is due to the fact that it brings comfort.