Cognitive dissonance theory of communication

| Table of Contents Intrapersonal Communication (Persuasion) Interpersonal Communication Small Group Communication Organizational Communication Intercultural Communication Mass Communication Applied Contexts Health Communication Instructional Communication Honors Capstone Home Page Last updated Feburary 14, 2001 | SPRING 2001 THEORY WORKBOOK PERSUASION CONTEXT Click Here to Go Back to Persuasion Context Page Cognitive Dissonance Explanation of Theory: Theorist: Leon Festinger Date: 1962 Primary Article: Individual Interpretations: Critique: Ideas and Implications: Example: Location in Eight (8) Primary Communication Theory Textbooks: Anderson, R., & Ross, V. (1998). Questions of communication: A practical introduction to theory (2nd ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. pp.111. Cragan, J. F., & Shields, D.C. (1998). Understanding communication theory: The communicative forces for human action. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Griffin, E. (2000). A first look at communication theory (4th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. N/A Griffin, E. (1997). A first look at communication theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 206-215. Infante, D. A., Rancer, A. S., & Womack, D. F. (1997). Building communication theory (3rd ed.). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press. pp. 56-57, 161-164, 528. Littlejohn, S. W. (1999). Theories of human communication (6th ed). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. pp. 137-139. West, R., & Turner, L. H. (2000). Introducing communication theory: Analysis and application. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield. pp. 104-116. Wood, J. T. (1997). Communication theories in action: An introduction. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. N/A

|

Cognitive Dissonance Theory – Real Life Examples

Amy is well aware of the benefits of engaging in some form of physical activity. Yet, she wakes up feeling zero motivation to move her body an inch. So she chooses to stick to her daily routine of waking up, glugging down a mug of cold coffee and driving her way to the office. She feels guilty about it every single day and decides things will change tomorrow.

Yet, she wakes up feeling zero motivation to move her body an inch. So she chooses to stick to her daily routine of waking up, glugging down a mug of cold coffee and driving her way to the office. She feels guilty about it every single day and decides things will change tomorrow.

Source: llhedgehogll/Adobe Stock

Many a time we find ourselves stuck in between a belief and behavior; both of which seem convincing. We may experience the intense urge to do a certain thing, but that behavior might be contrary to our morals and values.

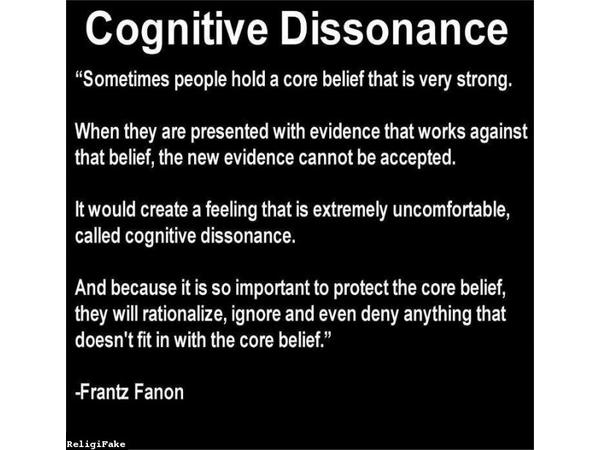

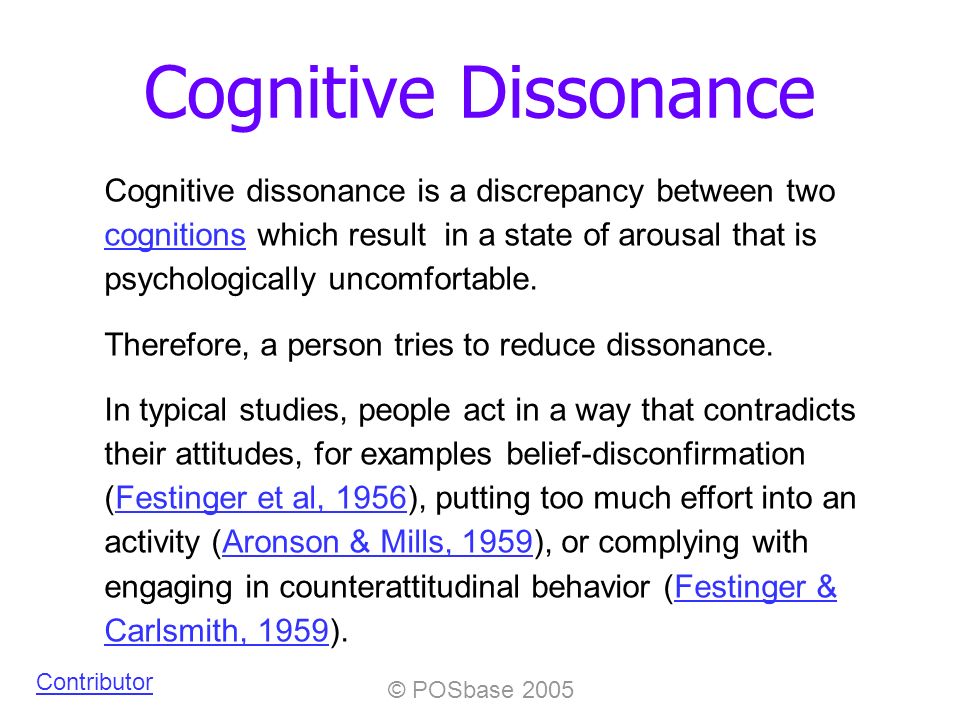

The mental clash or tension resulting from the processes of acquiring knowledge or understanding through the senses is called cognitive dissonance. In simple, the clash of minds when we must choose from the choices can be called as cognitive dissonance.

Many of us have been here yet do not know it is a well-known concept backed up by research.

What is Cognitive Dissonance?

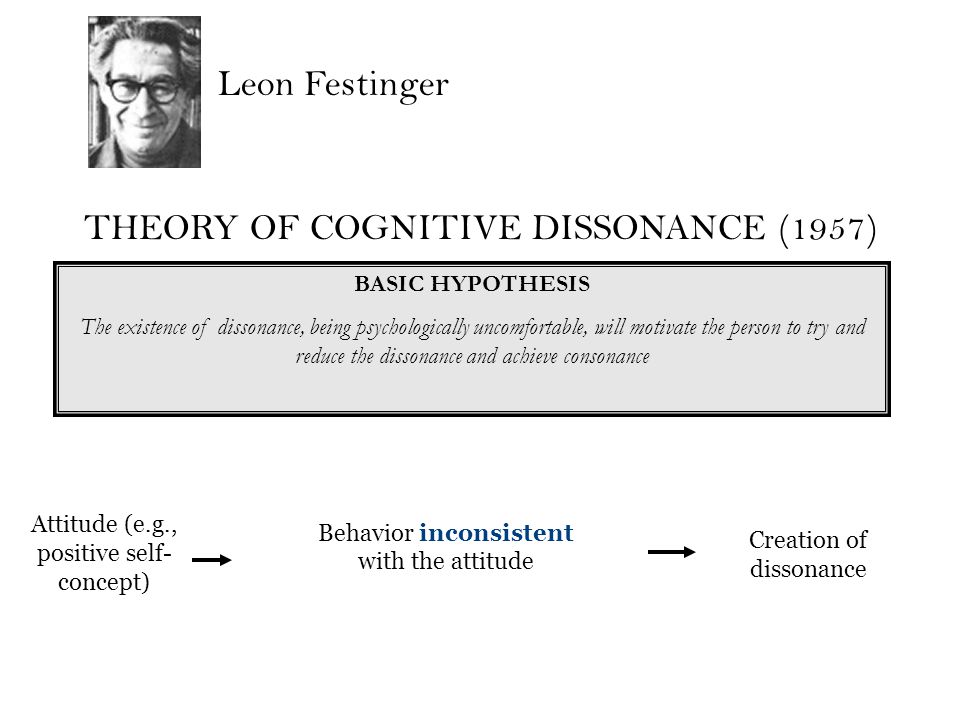

Cognitive dissonance is a theory proposed by Leon Festinger in the 1950s. He talks about this theory in detail in his book “A theory of cognitive dissonance”. He is well known for his theories of “Cognitive Dissonance and Social Comparison”. He is also responsible for the discovery of the relevance of propinquity (Close relationship) in the formation of social ties and bonds.

He talks about this theory in detail in his book “A theory of cognitive dissonance”. He is well known for his theories of “Cognitive Dissonance and Social Comparison”. He is also responsible for the discovery of the relevance of propinquity (Close relationship) in the formation of social ties and bonds.

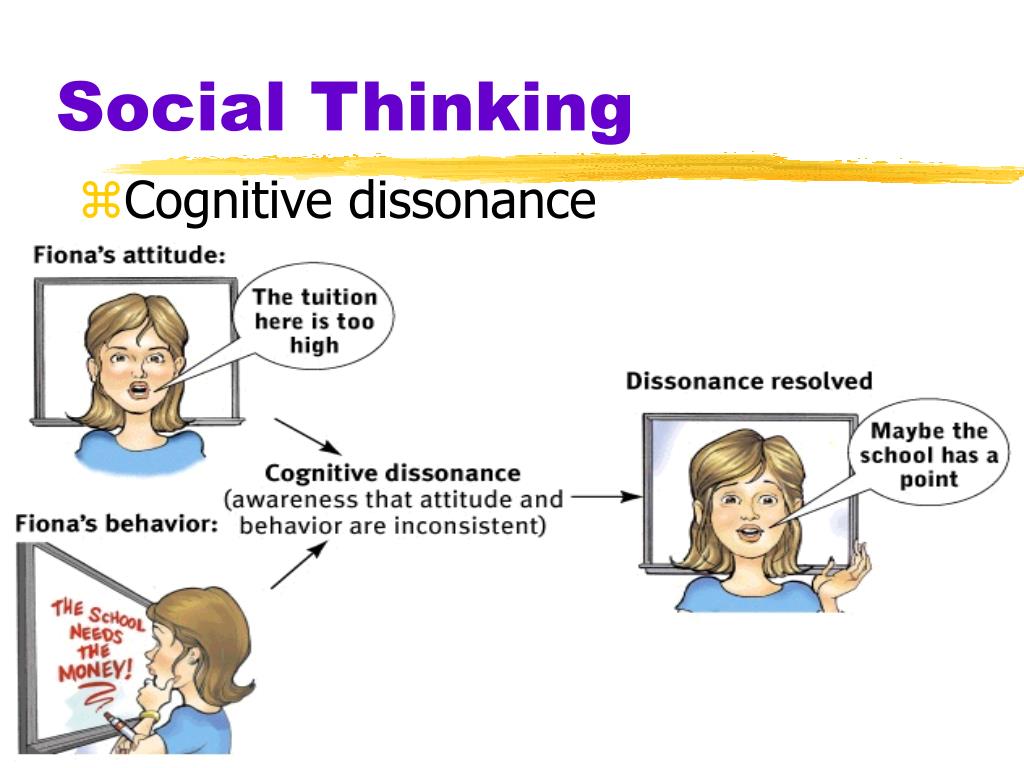

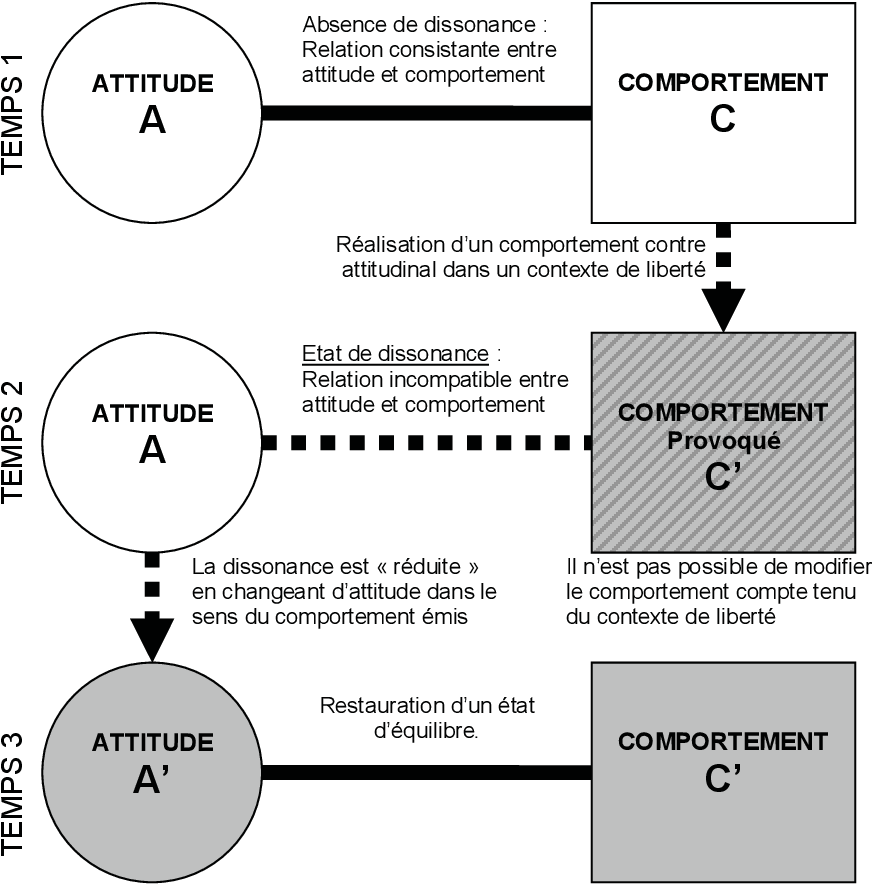

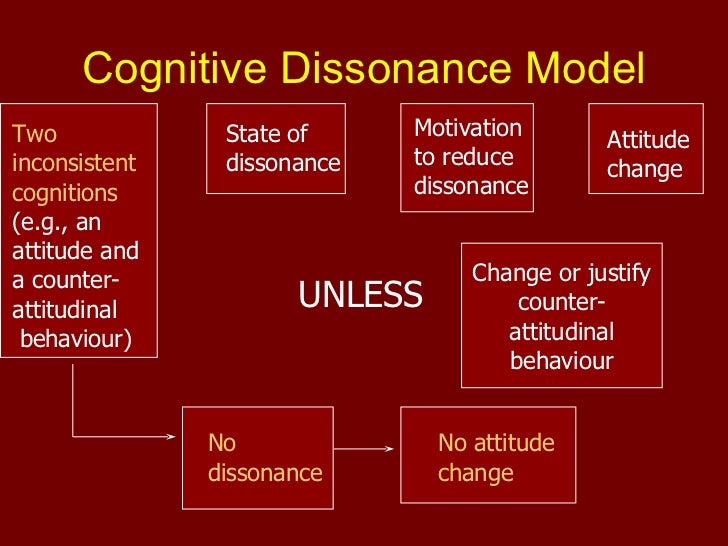

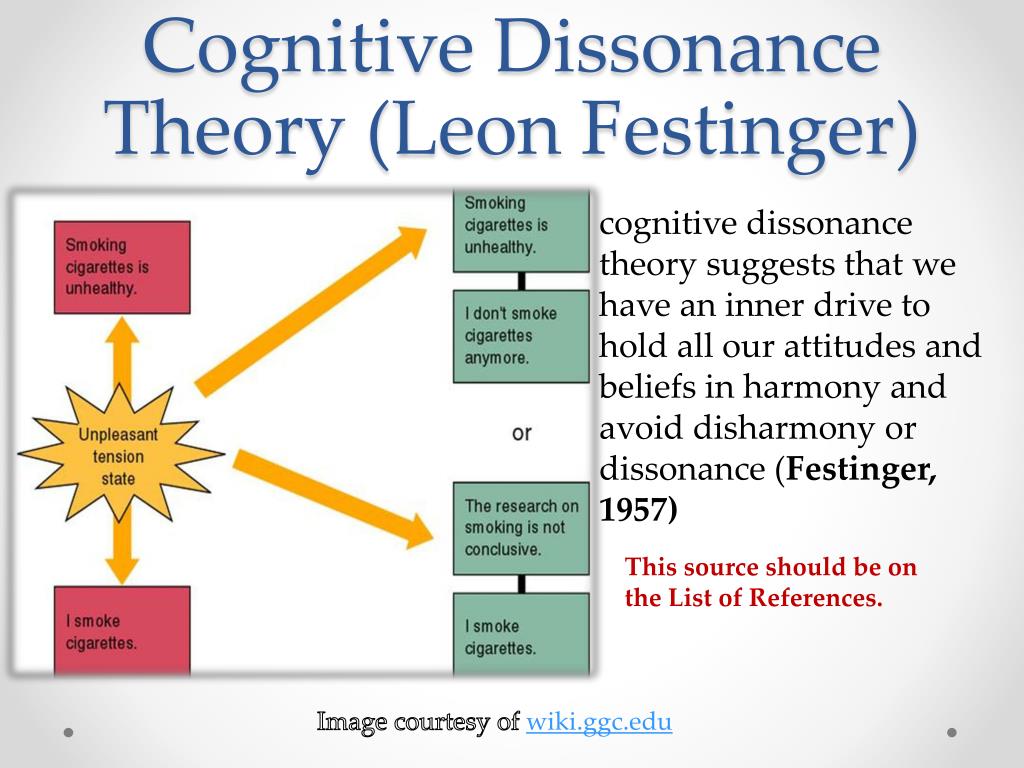

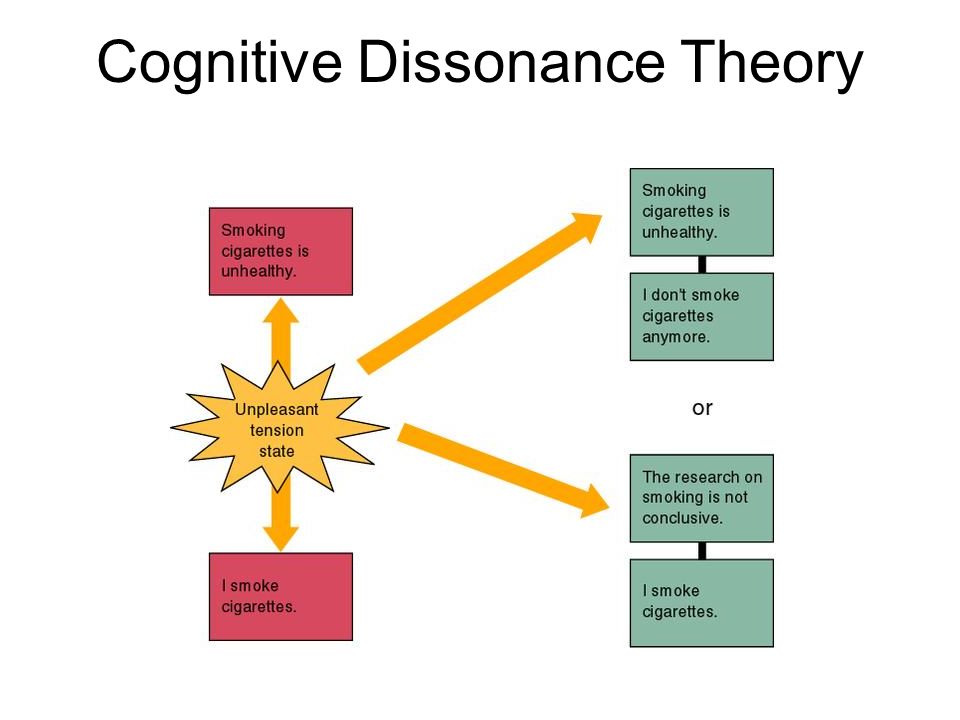

In this theory, he states that cognitive dissonance is a state of non-equilibrium where the behaviors and attitudes are inconsistent with one another. In simpler terms, when a person engages in a behavior that does not match their beliefs and moral values, they tend to experience a psychological discomfort which is termed cognitive dissonance.

This is the feeling of discomfort from two conflicting thoughts, it may increase or decrease according to the following factors

- The relevance of the subject to us.

- How solid the choices or thoughts are.

- The capability of our mind to choose, rationalize or explain our thoughts.

For example, Sara didn’t enjoy gossiping or making bad remarks about others as she believed in being kind and loving towards everyone. But when she was surrounded by her friends, she engaged in it anyway just so that she could fit in with them.

But when she was surrounded by her friends, she engaged in it anyway just so that she could fit in with them.

When people are confronted with dissonance, they fall into a state of psychological discomfort where their consistent state of equilibrium becomes precarious. As a result, they experience intense anxiety or a state of tension or other physiological symptoms which indicate that there is a change in the inner system. The dissonance will be at its highest on matters regarding self-image.

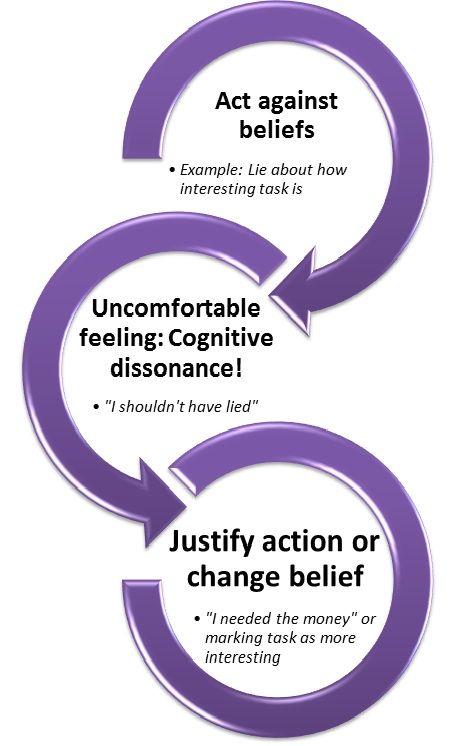

To bring themselves back to their perceived state of equilibrium, this person may either change their behavior or rationalize their decision by attempting to alter their belief system and moral values.

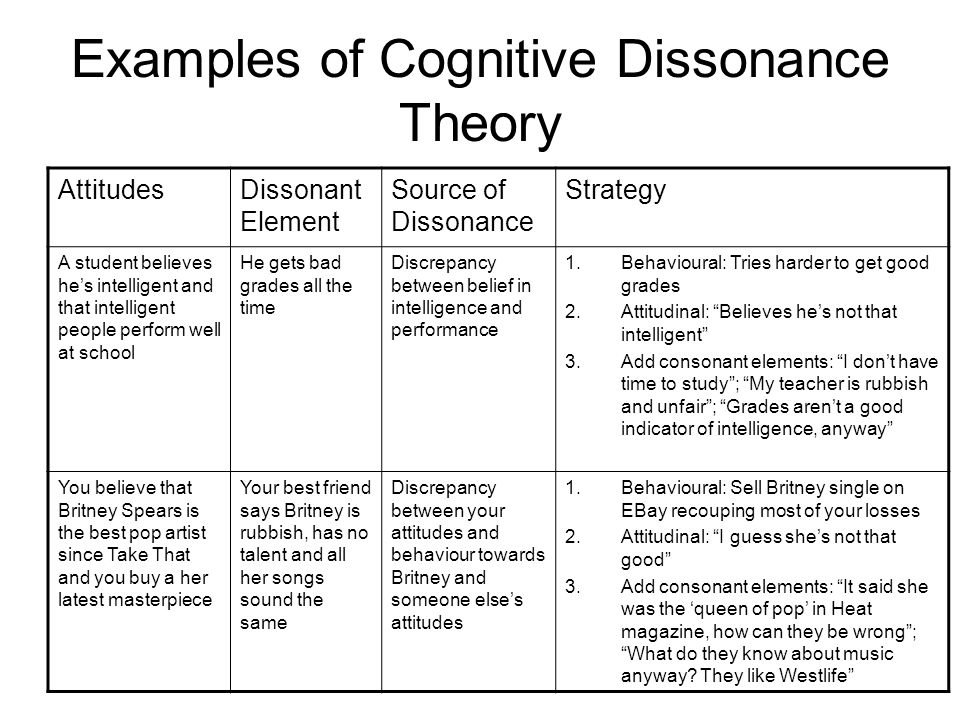

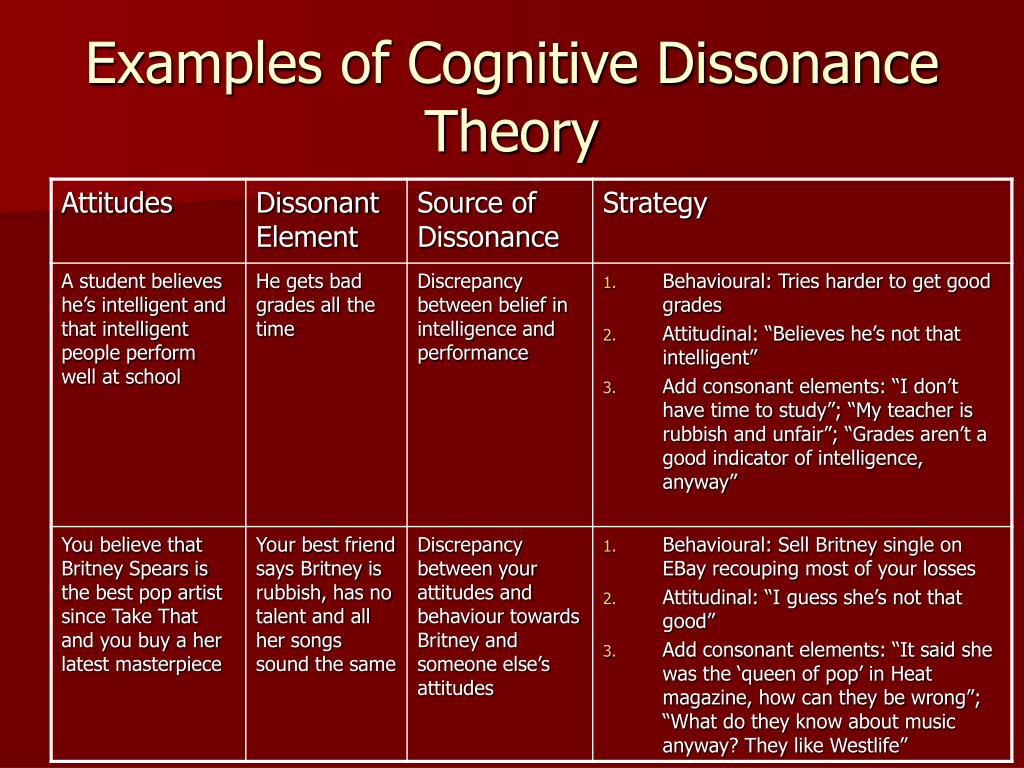

Strategies humans use to overcome cognitive dissonance

The theory states that we are possessed with a powerful drive to maintain cognitive steadiness and reliability which may sometimes become irrational. The mind will attain its harmony by the following steps.

- Change the conflicting behavior to make it consistent with their beliefs.

- Change the current cognition to defend the attitude-discrepant behavior.

- Form new cognitions to justify their attitude-discrepant behaviors.

For example, Bella is a strong-minded and highly opinionated person. Her behaviors directly reflected her beliefs, values and standards that she has set for herself. But her sudden need for a bulk amount of money put her morals to question.

She was well aware of the fact that her current job wouldn’t help her amass the amount that she’s currently in need of.

A friend gives her a choice to help hand over a few grams of an illegal drug to an anonymous person and that would pay more than she needs. But this transaction goes completely against the standards that Bella has set for herself.

In this situation, she can either choose to follow her morals and find an alternative that would align with her beliefs. Or she could choose to justify her behavior by emphasizing the criticality of her situation or she could choose to accommodate a new belief that engaging in such an attitude-discrepant behavior for a do or die the situation is not so wrong after all.

Research related to cognitive dissonance

Physiological arousal

Various studies have been undertaken to prove that cognitive dissonance leads to specific physiological responses in the form of arousal. Researchers studied the brain waves of those who engaged in unpleasant tasks that weren’t justified enough and found a lower level of alpha waves in their neural activity. Researchers also observed pupil dilation in some when performing an unpleasant task.

Cognitive dissonance and smoking

Research show that the level of factual knowledge in regards to the ill effects of smoking seems to be the same among smokers and non-smokers. However, it was found that smokers had more distorted thinking about smoking and attempted to rationalize their smoking behavior compared to non-smokers and ex-smokers.

Cognitive dissonance and consumer behavior

Cognitive dissonance has one of its vital implications in the field of consumer behaviorism. Consumers tend to assess and evaluate the various options available in the market and choose one that fits their idea of perfection. After deciding to purchase a product, however, they feel that they chose to purchase that product due to the pressure placed on them by the seller.

After deciding to purchase a product, however, they feel that they chose to purchase that product due to the pressure placed on them by the seller.

Hence, they are very likely to experience dissonance when there is a wide gap between their expectations and the real nature of the product. They regret their decision of having chosen a certain brand instead of an alternative brand which seems to offer more for the price paid.

Cognitive dissonance in romantic relationships

Cognitive dissonance is likely to happen even in day-to-day events regarding relationships and various other areas of life. Small examples from real-life situations can also put us in a state of dissonance where we are coerced to choose between two difficult choices.

As any relationship matures, we are made the face the reality of differences in the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of our close ones in comparison to what we believed they were.

For example, John and Maria were in a happy relationship and one day they decided to meet at a fancy restaurant to celebrate their six-month anniversary. John was present on time and he waited for Maria to join him soon. He waited for two hours straight and Maria wouldn’t pick up his calls either. Finally, as she came in, John enquired about what took her so long. Maria got heated and she called him names in front of the whole crowd and stomped out of the restaurant angrily.

John was present on time and he waited for Maria to join him soon. He waited for two hours straight and Maria wouldn’t pick up his calls either. Finally, as she came in, John enquired about what took her so long. Maria got heated and she called him names in front of the whole crowd and stomped out of the restaurant angrily.

In this situation, John is in a state of dissonance as he was visibly shocked by Maria’s behavior. He could either choose to rationalize the entire incident or choose to leave Maria.

When do people engage in attitude-discrepant behaviors?

People engage in attitude-discrepant behaviors when the behavior seems good or appealing to them and when the attitude isn’t strong enough to hinder them from engaging in certain behavior. Cognitive dissonance is experienced at a higher intensity when there are very few reasons to justify the behavior.

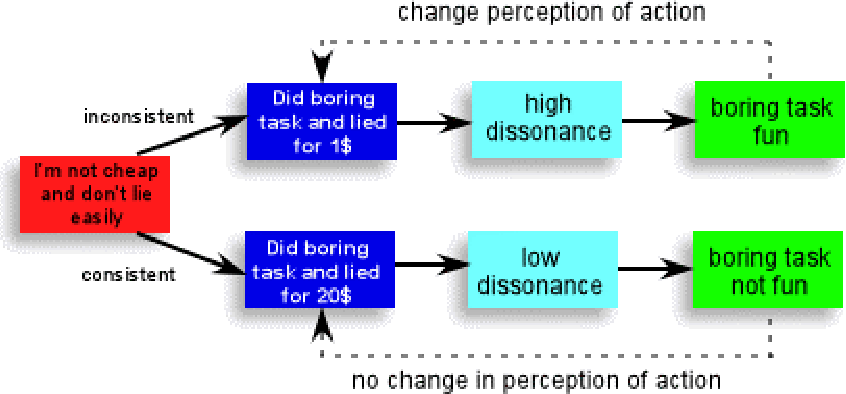

An interesting study conducted by Festinger and Carlsmith proves this assumption.

- Two groups of participants were asked to engage in a series of extremely boring tasks such as turning pegs in a board of holes.

- The researchers hence requested a favor from the participants since the research assistant was absent.

- They asked the participants to brief the experiment and claim that it was an interesting one for the upcoming participants.

- Researchers announced to one group of participants that they would be given $20 to make that pitch; whereas the other group would be paid $1 to do the same.

- Just as the researchers expected, the group which was paid $1 rated the task as more interesting and made a better pitch compared to the other group.

Such a result was observed because the group of people who were paid $1 had no valid justification to claim that the task was interesting. Hence they chose to alter their attitude toward the task to bring them back to a state of equilibrium and not feel that they were making a false claim. Researchers later came to call this phenomenon a “less-leads-to-more effect”.

What determines the intensity of the cognitive dissonance experienced?

This theory claims that the stronger the belief, the weaker the cognitive dissonance is and the weaker the attitude, the stronger is the cognitive dissonance.

For example, Joe strongly believed that being kind is one of the most essential aspects of being a good human. So, when he lashed out at his friend for calling him continuously, he felt extremely guilty for his impulsive behavior and wished he could’ve been calmer during that situation.

Can cognitive dissonance be used for positive behavioral outcomes?

Researchers wanted to investigate whether cognitive dissonance can be beneficial and can lead to positive changes in the community. Through their study, they concluded that cognitive dissonance can be employed in specific situations to elicit a feeling of “hypocrisy” in the participants which would, in turn, pave way for behavioral changes.

A study conducted by Stone, Wiegand, Cooper, and Aronson (1997)

Experiment

The participants were asked to make a videotape discussing the importance of using condoms to avoid contracting AIDS. Later, two groups of participants were asked about the reasons behind not using condoms in the past and also insisted to buy and use condoms in the future.

Interpretation

Researchers predicted that the participants who were made to give personal reasons would be more likely to purchase condoms in comparison to the group that was asked for a generalized reason.

Conclusion

when people were made to see their attitude-discrepant behavior face-to-face, they felt hypocritical about themselves and wanted to align their attitudes and behavior by choosing to reform their behaviors.

Criticism of Cognitive Dissonance Theory

This is the reason why we human beings tend to justify ourselves. This theory is subjective because we cannot physically observe cognitive dissonance so we cannot obtain any objective measurements. It has a sort of vagueness in its nature because every people will have their differences always.

Cognitive dissonance: what it is, examples, how to recognize it, how to overcome it

“I have cognitive dissonance,” we hear when describing any discrepancy between expectation and reality. This term has already become so widely used that not everyone thinks about its true meaning. Let's figure it out.

This term has already become so widely used that not everyone thinks about its true meaning. Let's figure it out.

The author of the article is Angelina Duka, Ph.D. Advertising on RBC www.adv.rbc.ru

What is cognitive dissonance

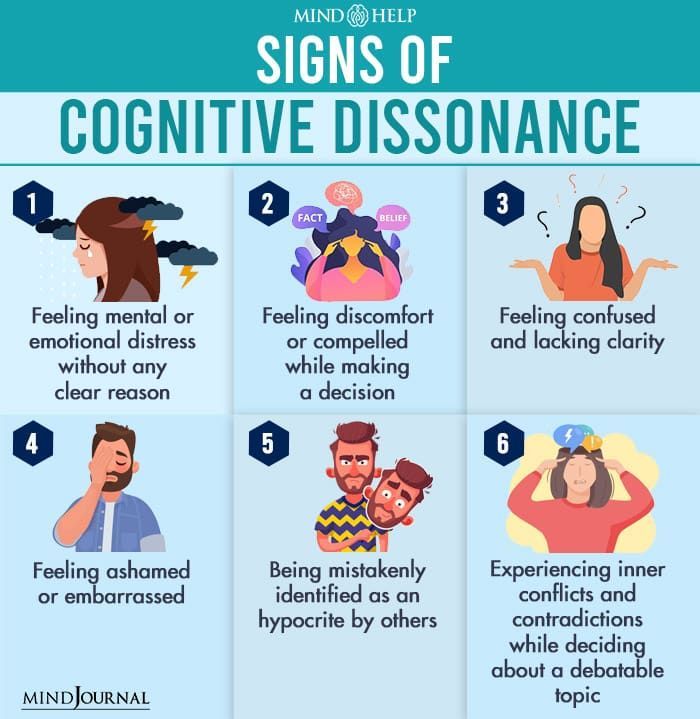

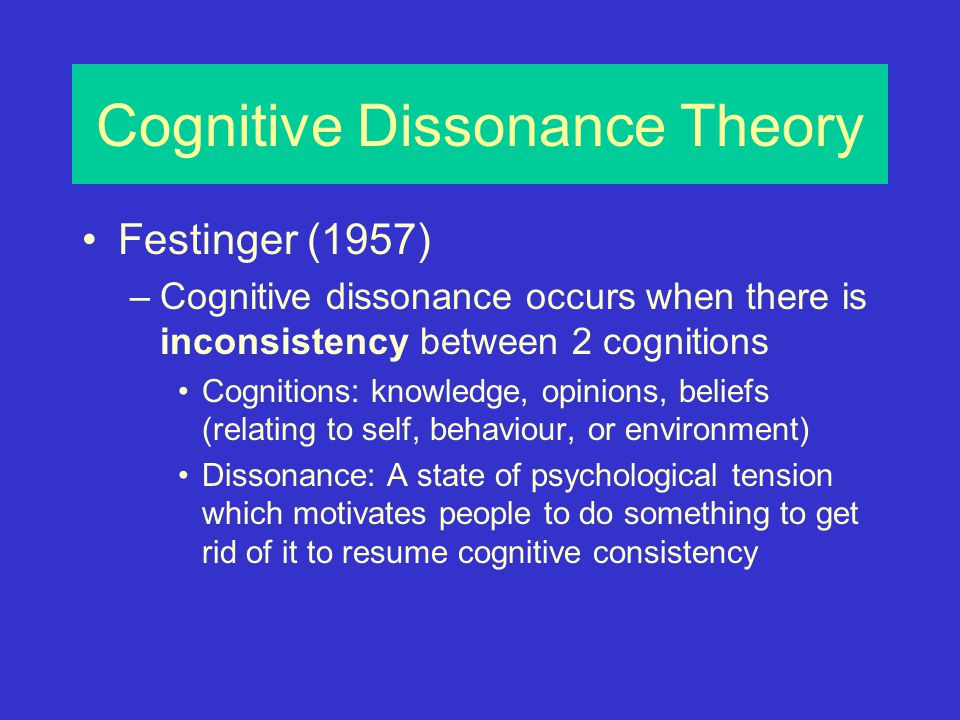

Cognitive dissonance is an internal conflict that occurs in a person when conflicting beliefs collide. This dissonance causes a feeling of tension; a person experiences unpleasant emotions: anxiety, anger, shame, guilt - and will strive to get rid of discomfort in various ways. The concept of "cognitive dissonance" came to us from social psychology.

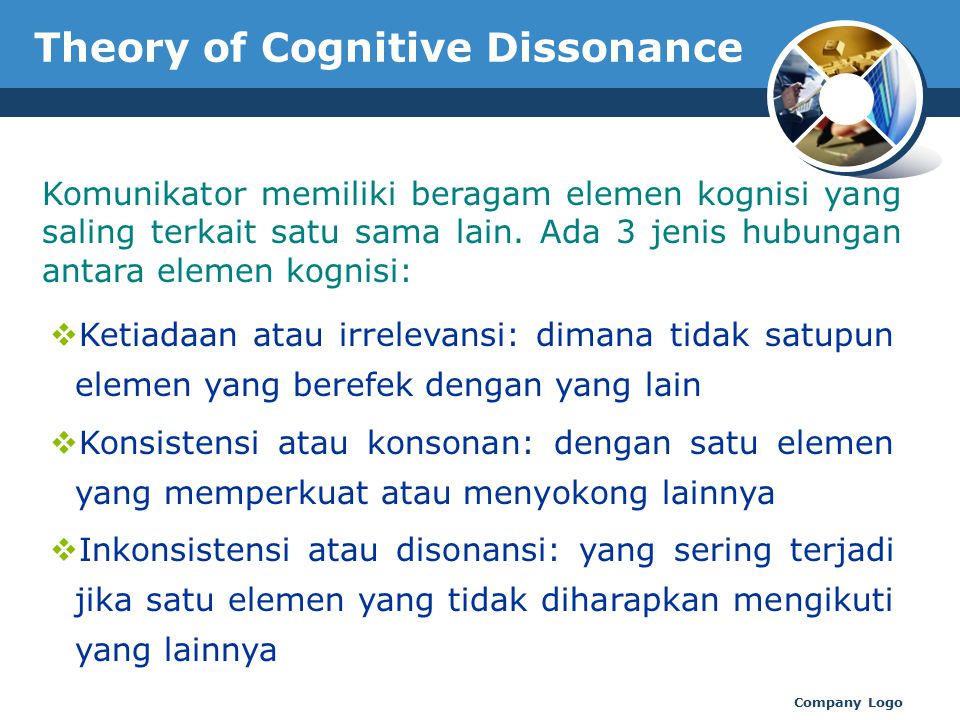

Theory of cognitive dissonance

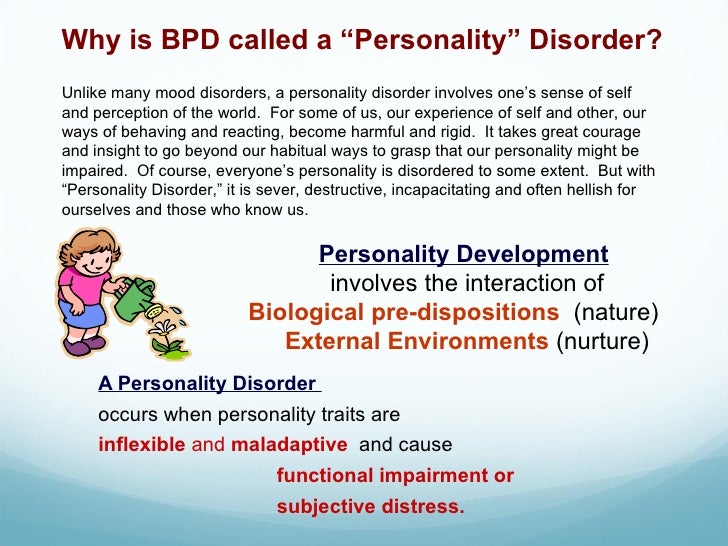

The concept of cognitive dissonance was first introduced by the social psychologist Leon Festinger. He suggested that in the presence of conflicting beliefs, people would experience emotional discomfort. In his study of rumor belief, Festinger concluded that people always strive for an internal balance between personal motives that determine their behavior and information received from outside. Festinger's theory describes how people try to rationalize their behavior. Dissonance occurs when a person simultaneously encounters two incompatible, but equally significant judgments - cognitions. What it is? Sometimes thoughts are meant by cognitions, but in fact this concept is much broader: thoughts, ideas, opinions, value judgments should be included here. In some situations, they provide mental stability, protecting us from intense experiences. However, sometimes this protection is achieved in a peculiar way - by self-deception.

Festinger's theory describes how people try to rationalize their behavior. Dissonance occurs when a person simultaneously encounters two incompatible, but equally significant judgments - cognitions. What it is? Sometimes thoughts are meant by cognitions, but in fact this concept is much broader: thoughts, ideas, opinions, value judgments should be included here. In some situations, they provide mental stability, protecting us from intense experiences. However, sometimes this protection is achieved in a peculiar way - by self-deception.

Does everyone experience cognitive dissonance the same way? No. Different people have different tolerances for uncertainty, so the degree of dissonance experienced will vary in intensity. The strength of dissonance is also affected by how strongly personal value beliefs are affected.

A still from the TV series The Queen's Move

© Kinopoisk

Why cognitive dissonance occurs

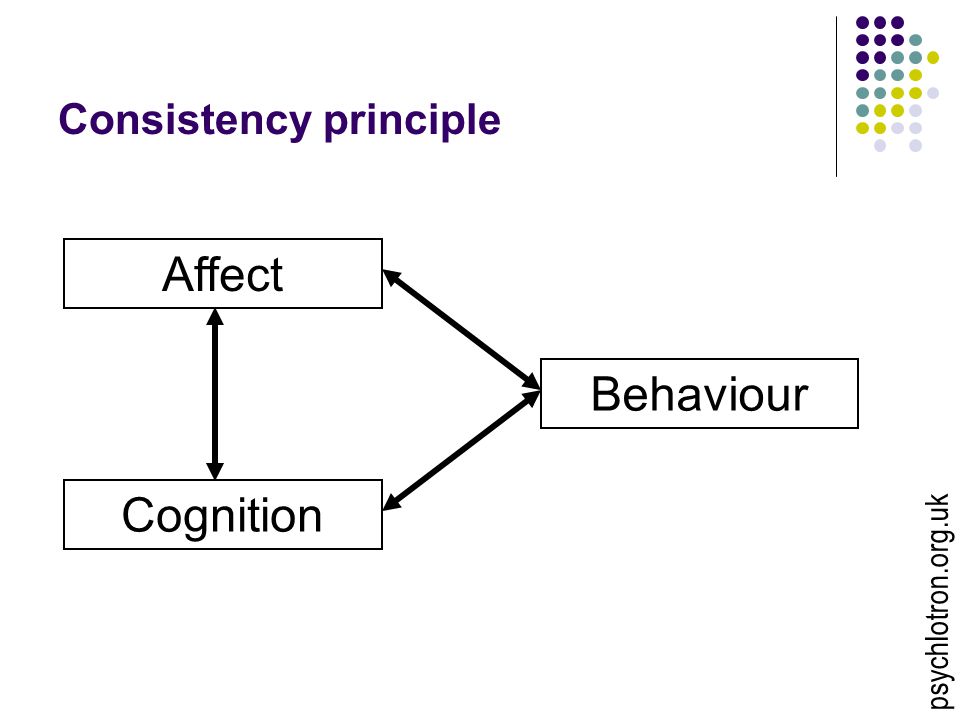

Social behavior researchers Anthony Pratkanis and Elliot Aronson suggested that the mental activity of any person is largely determined by two principles that explain the irrationality of some actions.

The principle of mental stereotypes

Our brain reduces costs where it is possible. We strive to preserve the so-called cognitive energy, reducing its consumption to a minimum and using mental stereotypes wherever possible. This principle has both positive and negative effects. On the one hand, we, for example, create algorithms for solving typical problems and thereby simplify our work. On the other hand, in order to simplify complex problems, we often choose not a justified conclusion, but one that does not require deep reflection. Figuratively speaking, we are looking for keys not where we lost them, but where it is brighter.

Critical thinking requires additional resources, just as breaking any formed habit requires effort. Ignoring a comprehensive assessment of the situation, some repeat past mistakes many times and bring themselves into a state of debilitating stress.

The principle of rationalization of one's behavior, or the principle of self-explanation

It is common for any of us to give our actions a reasonable justification so that they seem logical both to ourselves and to our environment. Self-explanation acts as a guideline, as an ideological basis: “I do this because ...” - the continuation of the phrase will be different for everyone. A person must perceive his own behavior as reasonable and understandable - otherwise there is a threat to the integrity of his "I". However, the way we explain our actions does not always correspond to reality: very often, trying to calm ourselves, we wishful thinking through self-deception and rationalization.

Self-explanation acts as a guideline, as an ideological basis: “I do this because ...” - the continuation of the phrase will be different for everyone. A person must perceive his own behavior as reasonable and understandable - otherwise there is a threat to the integrity of his "I". However, the way we explain our actions does not always correspond to reality: very often, trying to calm ourselves, we wishful thinking through self-deception and rationalization.

These principles illustrate how a person rationalizes their behavior to avoid discomfort.

Shot from the movie "1+1"

© Kinopoisk

Examples of cognitive dissonance

Let's look at a simple example of how you can encounter cognitive dissonance. Choosing, say, a car, we compare different models and make a choice in favor of one of them. We are happy with our purchase and believe we made the best choice possible. If, after buying a car, we come across information that calls into question the correctness of our decision, then we will ignore it, even if it is true. Or we will justify ourselves by saying, "My car is better anyway." Or, talking about other cars, we will recall examples of how bad they are in operation, look for confirmation on forums, among friends. Thus, we strive to save ourselves from discomfort and maintain a positive attitude towards ourselves. At the same time, finding information confirming the correctness of our choice, we will certainly notice it and experience positive emotions, since we will unconsciously perceive it as speaking in favor of our positive self-image.

Or we will justify ourselves by saying, "My car is better anyway." Or, talking about other cars, we will recall examples of how bad they are in operation, look for confirmation on forums, among friends. Thus, we strive to save ourselves from discomfort and maintain a positive attitude towards ourselves. At the same time, finding information confirming the correctness of our choice, we will certainly notice it and experience positive emotions, since we will unconsciously perceive it as speaking in favor of our positive self-image.

Russian classical literature is full of examples of cognitive dissonance when the hero makes a difficult choice. Thus, in The Quiet Don, Sholokhov, through the prism of the families of the Melekhovs, Korshunovs and other characters, shows how individuals make difficult decisions at critical moments and cope with cognitive dissonance.

How to Overcome Cognitive Dissonance

By looking at typical behaviors, you can understand how to deal with the discomfort of cognitive dissonance.

Avoiding or devaluing factual information

This strategy helps people continue to maintain behaviors with which they do not fully agree (for example, I know that smoking is bad, but I continue to do so). To reduce cognitive dissonance, a person can limit access to new information that does not correspond to his beliefs, devalue these facts, perceiving them as false, avoid studying additional sources and situations in which alternative points of view can be encountered.

Rationalization

Justifying oneself, trying to make sure that there is no internal conflict. People begin to seek support among those who share similar views, or try to convince the other that the new information is inaccurate; looking for ways to justify behavior that goes against their beliefs. Unfortunately, often behind explanations that seem rational to us, in fact, there are irrational beliefs containing logical errors that are not supported by facts, and this causes us suffering.

Changing one's behavior

Discomfort can push a person to change their behavior so that actions are consistent with their beliefs. As a result of cognitive dissonance, many people are faced with a conflict of values, resolving which they can bring positive changes to their lives, move closer to the ideal in accordance with which they want to live - this is the case when cognitive dissonance can have a positive impact. For example, a person eats a lot of sugary fatty foods every day, while he is at risk of diabetes and he is aware of the consequences. Feeling discomfort from cognitive dissonance, he eventually changes his behavior: he corrects his diet, thereby taking a step towards his value - health.

A still from the film Bridget Jones's Diary

© Kinopoisk

The development of critical thinking

It is possible to establish the truth by analyzing the arguments of each side of cognitive dissonance.

To do this, you need to answer the question of whether it is logical to think so, what is the logic of judgments.

Then, with the help of empirical facts, one should weigh the two points of view and ask oneself:

- what proves my point;

- that refutes it;

- what evidence (facts, arguments) can be given in favor of the opposite point of view;

- what do I get when I think so;

- Do my thoughts help me get what I want?

As you might guess, the first two strategies are not very productive - they may bring temporary relief, but they will not relieve discomfort. The third and fourth models are the most constructive: here the internal conflict is really resolved.

So, cognitive dissonance is a phenomenon that everyone encounters. It influences our decisions in many different areas. And although cognitive dissonance may seem like a negative effect of thinking, it can help develop and change for the better, pushing us to do things that are in line with our values.

Tags: psychology

What is cognitive dissonance, or why it's so hard to quit smoking - T&P

"Theory and Practice" continues to explain the meaning of commonly used expressions that are often used in colloquial speech in the wrong sense.

This issue explores why we so often fool ourselves, what the hungry fox has in common with Ash's experiment, and how cognitive dissonance helps Buddhists achieve awakening.

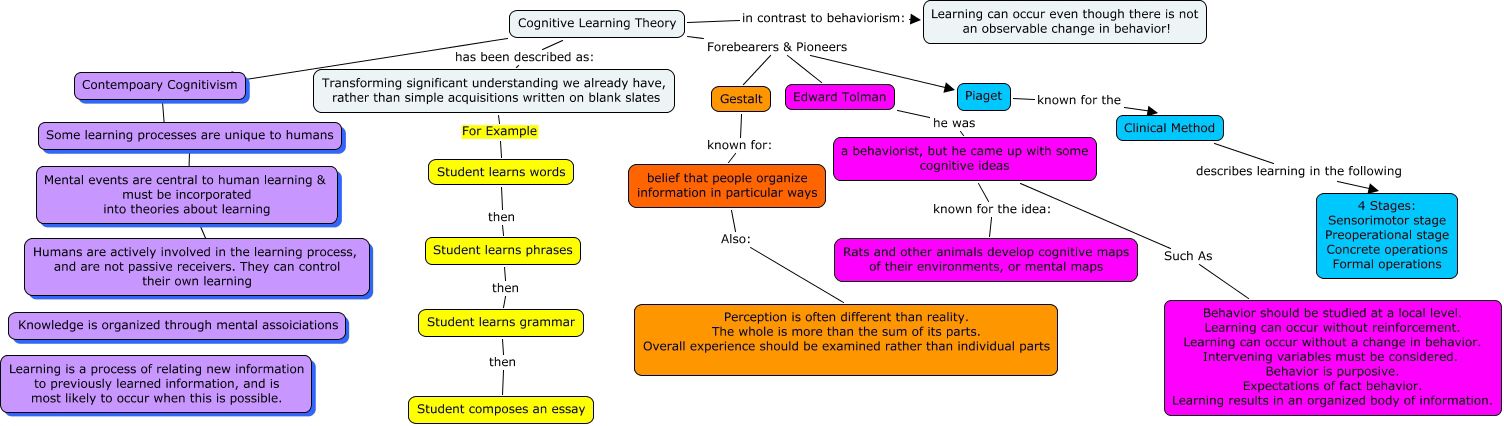

This issue explores why we so often fool ourselves, what the hungry fox has in common with Ash's experiment, and how cognitive dissonance helps Buddhists achieve awakening. The phrase, which became fashionable thanks to Viktor Pelevin, is now used for any discrepancy between expectations and reality - including where it would be quite possible to get by with the expressions “I am puzzled”, “I am in a stupor” or “I feel a contradiction”. But do not forget that behind the smart-sounding phrase “I have cognitive dissonance” there is a whole psychological theory that is useful for everyone to know. It was developed by the American psychologist Leon Festinger at 1957 based on Kurt Lewin's field theory and Fritz Hader's structural balance theory.

The reason for its creation was the study of rumors spread as a result of the earthquake in India in 1934. In the regions that were not affected by the earthquake, rumors spread that even stronger tremors would soon occur in new places and danger could threaten these areas as well. It was strange that such pessimistic (and completely unfounded) forecasts were so widespread. In the end, scientists who studied this phenomenon concluded that these rumors justified the concern rather than caused it. People distributed them to justify the irrational state of fear caused by the news of the earthquake.

It was strange that such pessimistic (and completely unfounded) forecasts were so widespread. In the end, scientists who studied this phenomenon concluded that these rumors justified the concern rather than caused it. People distributed them to justify the irrational state of fear caused by the news of the earthquake.

The problem is that when trying to resolve cognitive dissonance, a person is often busy not searching for truth, but formally reducing knowledge and motives to a common denominator - therefore, many people cope with internal contradictions using the first more or less suitable excuse

Similar situations have happened more than once in history. For example, during World War II, in one of the American camps for Japanese refugees, where there were quite normal living conditions, rumors arose that the friendliness of the Americans was deceptive, and the place for the camp was specially chosen so that people could not survive in it. This happened due to the discrepancy between reality and the ideas of the Japanese about the hostility of the United States to their country. Researching such stories, Festinger concluded that people strive for an internal balance between the information received and their own ideas and motives. The contradiction that arises when this balance is disturbed, he called cognitive dissonance.

Researching such stories, Festinger concluded that people strive for an internal balance between the information received and their own ideas and motives. The contradiction that arises when this balance is disturbed, he called cognitive dissonance.

This condition can occur for several reasons. For example, due to a logical contradiction, like "I don't care about the opinions of others, but I want to become famous." Or because of the inconsistency of the decisions and behavior of a person with the cultural customs adopted in his country, social group or family. Dissonance can also arise when an individual identifies with a certain group of people, but his own opinion begins to contradict the opinion of the group. For example, a person considers himself a liberal, but suddenly realizes that he would not want to live in close proximity to gays or people of a different race and religion. Or to the patriots, but he feels that "it's time to leave." And, finally, the simplest case is when new information contradicts the previous picture of the world. For example, if Gennady Onishchenko suddenly received the Nobel Prize for achievements in medicine, this would cause cognitive dissonance among the entire Russian population.

For example, if Gennady Onishchenko suddenly received the Nobel Prize for achievements in medicine, this would cause cognitive dissonance among the entire Russian population.

And then the most interesting thing begins - when a person has conflicting ideas, this brings him discomfort. And he seeks to smooth out the contradiction that has arisen. This can be done in two main ways - either to revise and reject one of the ideas, or to find new information that allows you to "join" incompatible positions.

Festinger himself gives this example: if a smoker learns about a new study that proves the connection between smoking and the occurrence of cancerous tumors, he, of course, with some probability can quit smoking. But with a greater probability, he will either classify himself as a moderate smoker (“I smoke so little that it cannot greatly affect my health”), or find positive aspects in smoking (“but while I smoke, I do not get better” or “ so what, I’ll die earlier — but life will be high”), or will look for information that refutes the opinion about the dangers of smoking (“my nicotine-addicted grandfather lived to be 100 years old”) and avoid information that confirms it.

Another way to resolve cognitive dissonance is to change the environment to a new one, where the combination of "mutually exclusive paragraphs" will no longer cause contradictions. If you have changed your political views, most likely you will want to communicate more with the circle of acquaintances who share your new opinion.

The problem is that when trying to resolve cognitive dissonance, a person is often engaged not in the search for truth, but in the formal reduction of knowledge and motives to a common denominator - therefore, many people cope with internal contradictions using the first more or less suitable justification. A classic example is the fable about the fox and the grapes. The fox wants to eat grapes, but cannot pick them from the vine - it is too high. To avoid the contradiction between desire and possibility, she convinces herself that the grapes are still green and tasteless. Cunning - but soothing.

Another catch of cognitive dissonance is that it can play into the hands of manipulators.

We often settle for something we had absolutely no intention of doing, as long as it fits our flattering self-image.

A number of studies are connected with a special case of cognitive dissonance - a situation of forced consent leading to actions that a person cannot satisfactorily justify for himself. For example, when he voluntarily makes a decision, which in the end does not bring him sufficient satisfaction. To reduce the dissonance that arises in this situation and justify your choice - which would otherwise seem stupid - you need to retroactively increase the value of the action or devalue its negative aspects.

In particular, in the experiment of Leon Festinger and Merrill Carlsmith, subjects had to perform extremely boring work. After that, they were asked to recommend this experiment to subsequent participants as very interesting. One group of subjects was paid $20 each, the other group only $1. In the end, it turned out that the participants who received less, themselves found the experiment more interesting than those who worked for $20. And this was not scientific enthusiasm at all, but just a manifestation of cognitive dissonance: in order to make it easier to lie to subsequent participants, the subjects retroactively changed their perception of the experiment. A completely innocent reaction in this case - but if we recall, for example, Ash's experiment, it becomes clear that an easy way to overcome contradictions can lead to frightening consequences.

And this was not scientific enthusiasm at all, but just a manifestation of cognitive dissonance: in order to make it easier to lie to subsequent participants, the subjects retroactively changed their perception of the experiment. A completely innocent reaction in this case - but if we recall, for example, Ash's experiment, it becomes clear that an easy way to overcome contradictions can lead to frightening consequences.

Another catch of cognitive dissonance is that it can play into the hands of manipulators. In particular, the principle of consistency, described by Robert Cialdini, in the book The Psychology of Influence, is based precisely on the fear of cognitive dissonance. We often settle for something we had absolutely no intention of doing, as long as it fits our flattering self-image. For example, in order to persuade a person to donate money to any social initiative, you must first encourage him to recognize himself as generous.

But if you do not try to drown out the contradiction with the first justifications that come across, but start unwinding the tangle to its very essence, this can become a powerful impetus in the development of a person.

The theory of cognitive dissonance could be proved false through testing and invites new research on specific aspects of the concept.

The theory of cognitive dissonance could be proved false through testing and invites new research on specific aspects of the concept.  The different commercials and print ads show homelessness and its effects. When trying to persuade an audience member to give, they must persuade them that their organization is a worthy one. If someone believes that the homeless are lazy and dont deserve donations, they will not donate until that belief is changed. If they were to consider donating they would experience dissonance in which either their belief or action would undergo a change. It is the Salvation Armys goal to change the belief that the homeless are lazy so the reduction of dissonance will result in a donation.

The different commercials and print ads show homelessness and its effects. When trying to persuade an audience member to give, they must persuade them that their organization is a worthy one. If someone believes that the homeless are lazy and dont deserve donations, they will not donate until that belief is changed. If they were to consider donating they would experience dissonance in which either their belief or action would undergo a change. It is the Salvation Armys goal to change the belief that the homeless are lazy so the reduction of dissonance will result in a donation.  pp. 178,332.

pp. 178,332.