Cbt and ptsd

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Treatment of PTSD

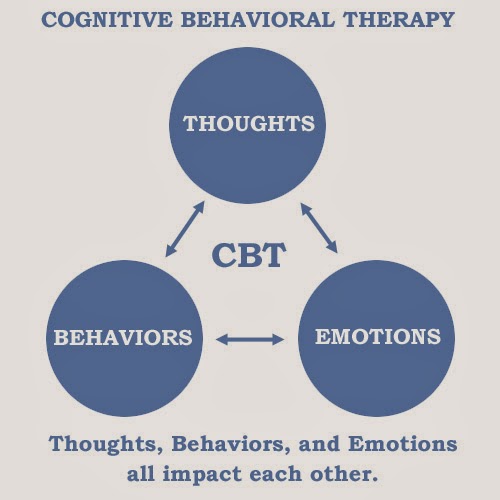

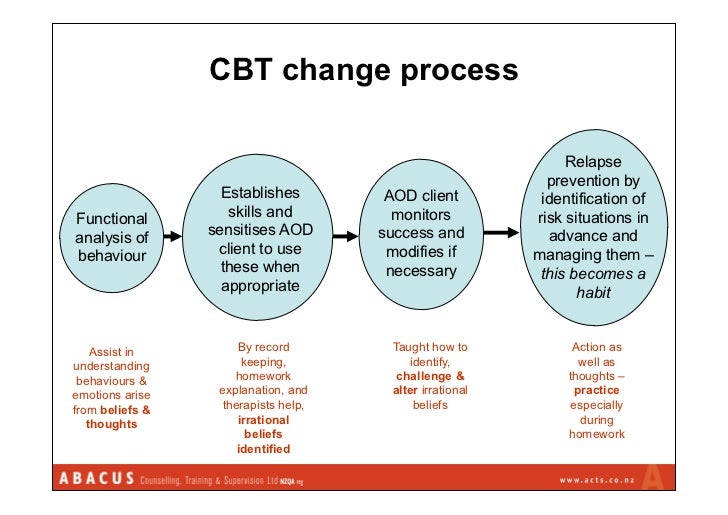

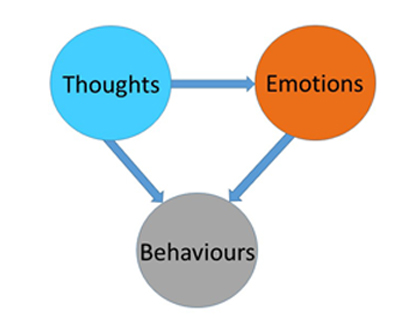

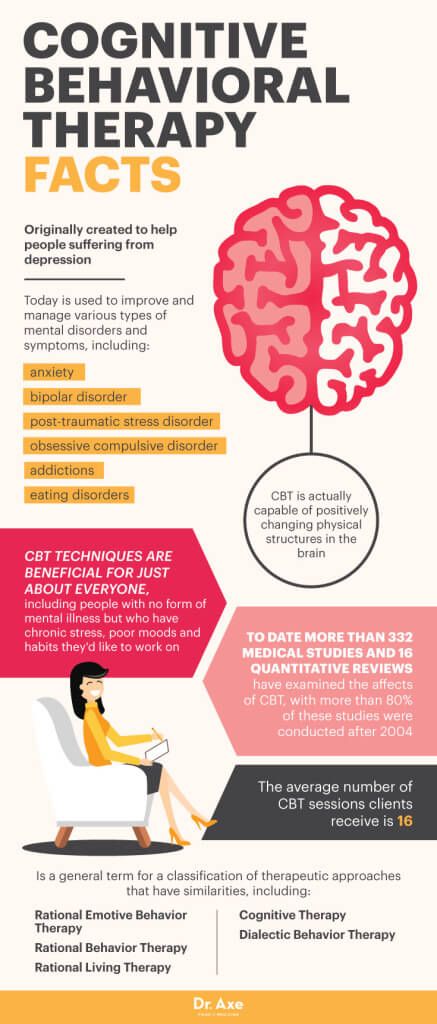

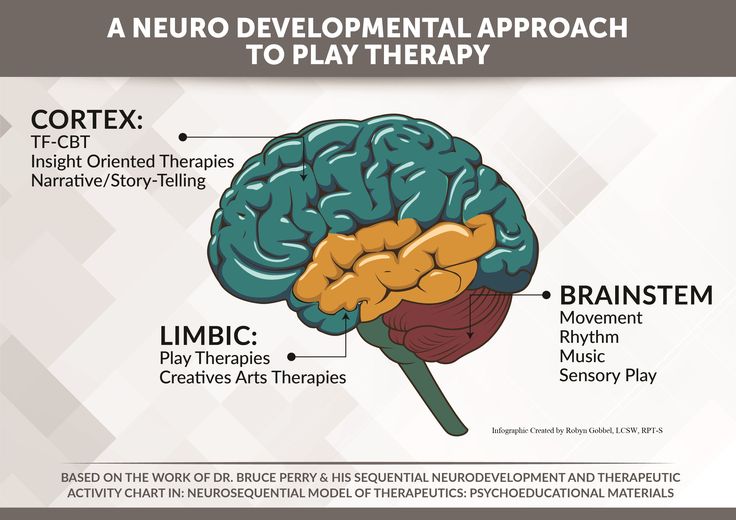

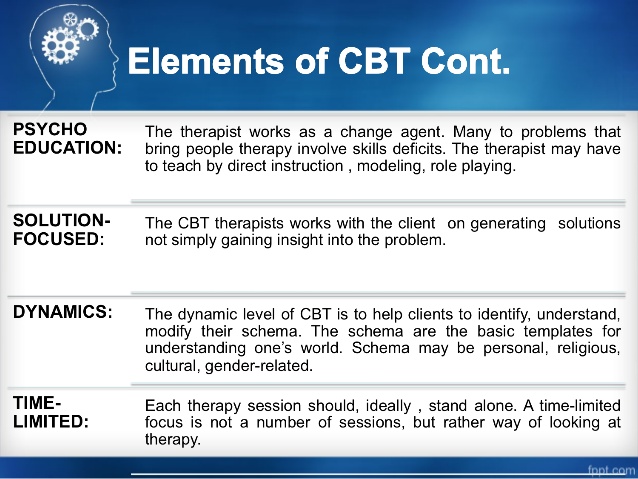

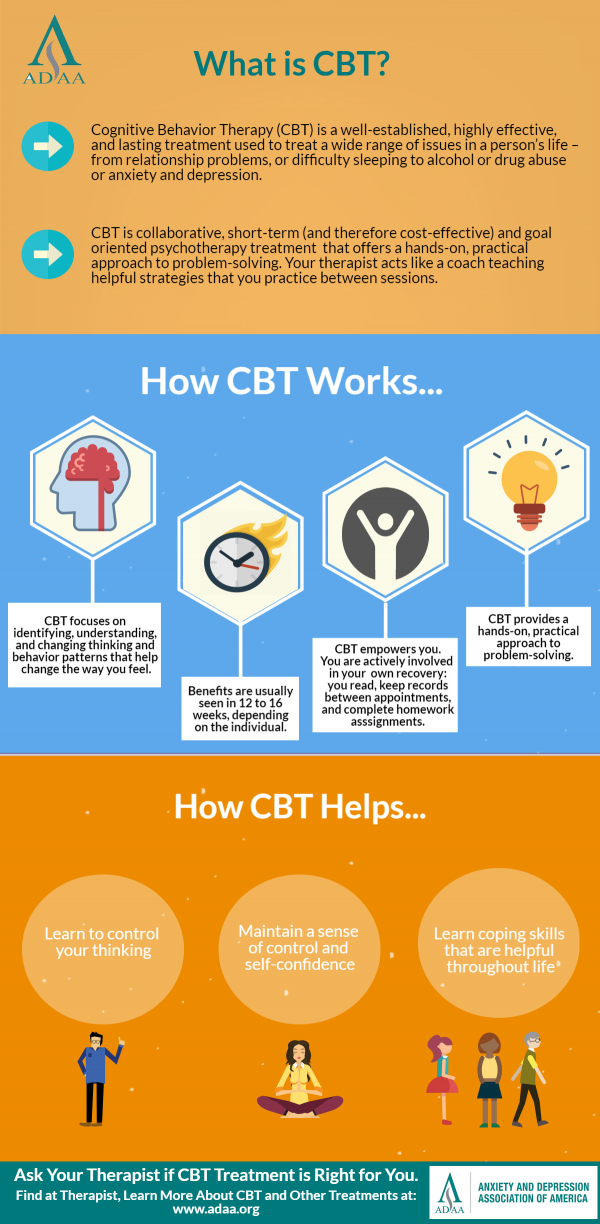

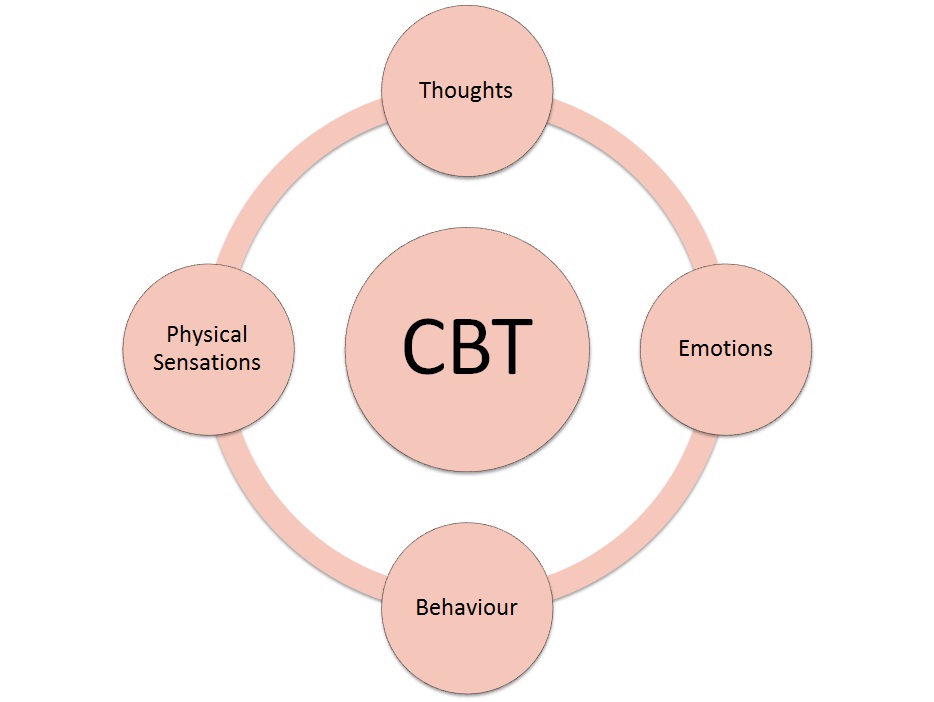

Cognitive behavioral therapy focuses on the relationship among thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; targets current problems and symptoms; and focuses on changing patterns of behaviors, thoughts and feelings that lead to difficulties in functioning.

Introduction to CBT

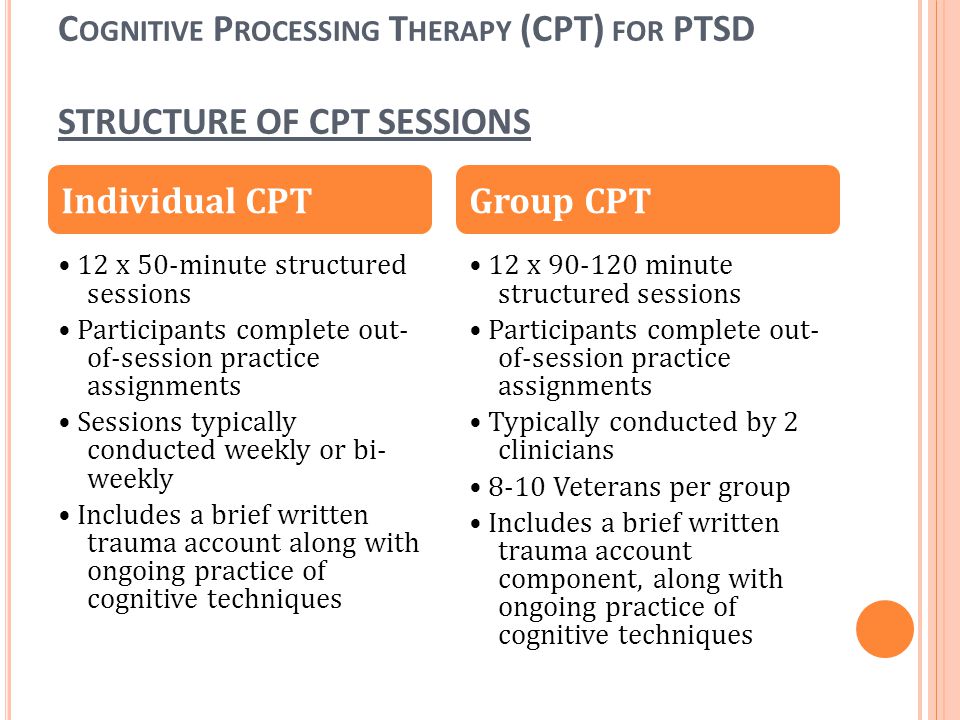

Cognitive behavioral therapy focuses on the relationship among thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and notes how changes in any one domain can improve functioning in the other domains. For example, altering a person’s unhelpful thinking can lead to healthier behaviors and improved emotion regulation. CBT targets current problems and symptoms and is typically delivered over 12-16 sessions in either individual or group format.

This treatment is strongly recommended for the treatment of PTSD.

How CBT Can Help with PTSD

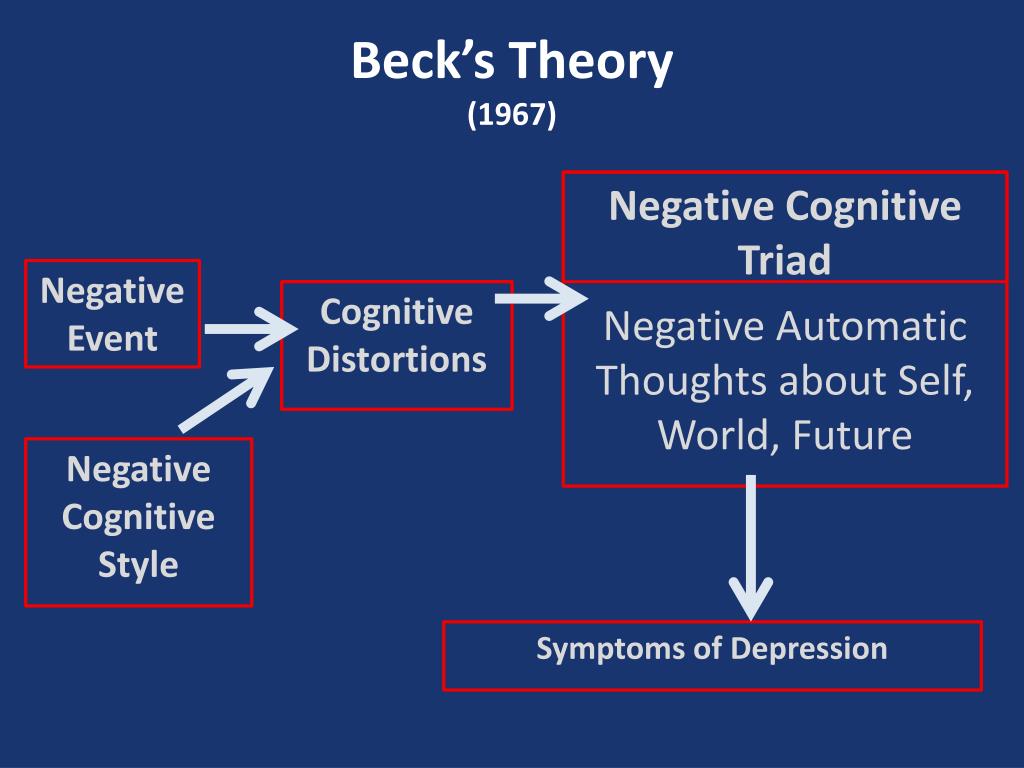

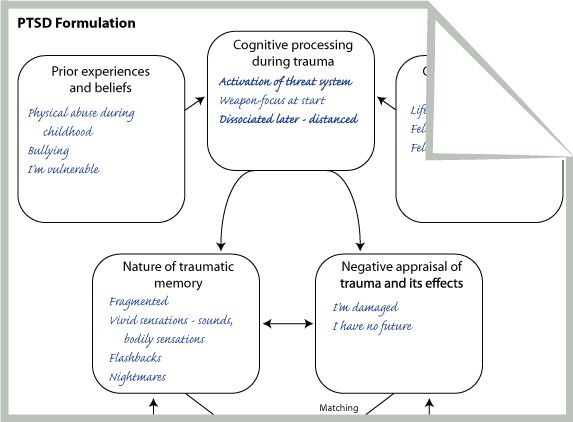

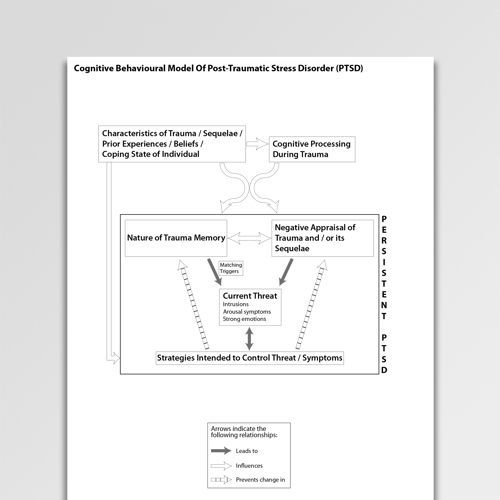

Several theories specific to trauma explain how CBT can be helpful in reducing the symptoms of PTSD.

For example, emotional processing theory (Rauch & Foa, 2006) suggests that those who have experienced a traumatic event can develop associations among objectively safe reminders of the event (e.g., news stories, situations, people), meaning (e.g., the world is dangerous) and responses (e.g., fear, numbing of feelings). Changing these associations that lead to unhealthy functioning is the core of emotional processing.

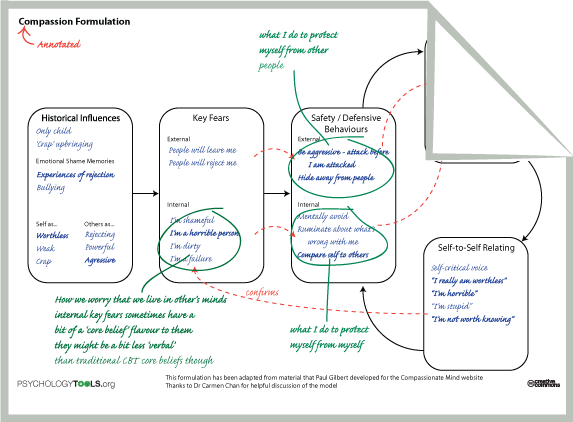

Social cognitive theory (Benight & Bandura, 2004) suggests that those who try to incorporate the experience of trauma into existing beliefs about oneself, others, and the world often wind up with unhelpful understandings of their experience and perceptions of control of self or the environment (i.e., coping self-efficacy). For instance, if someone believes that bad things happen to bad people, being raped confirms that one is bad, not that one was unjustly violated.

Understanding these theories helps the therapist more effectively use cognitive behavioral treatment strategies.

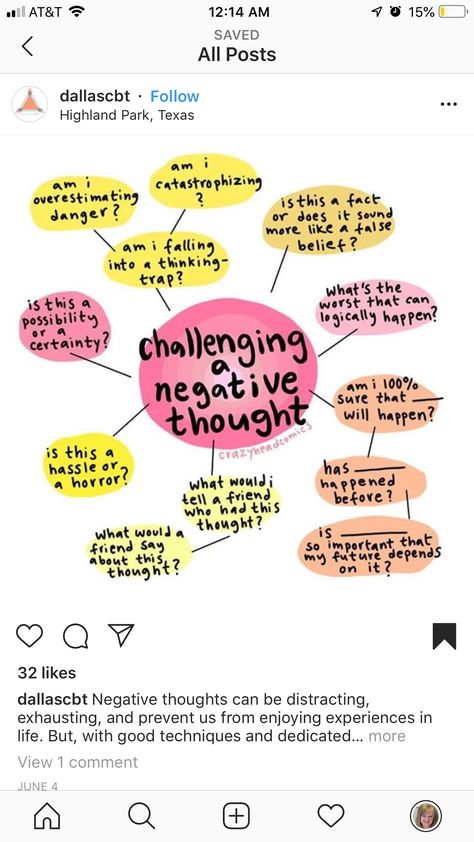

Using CBT to Treat PTSD

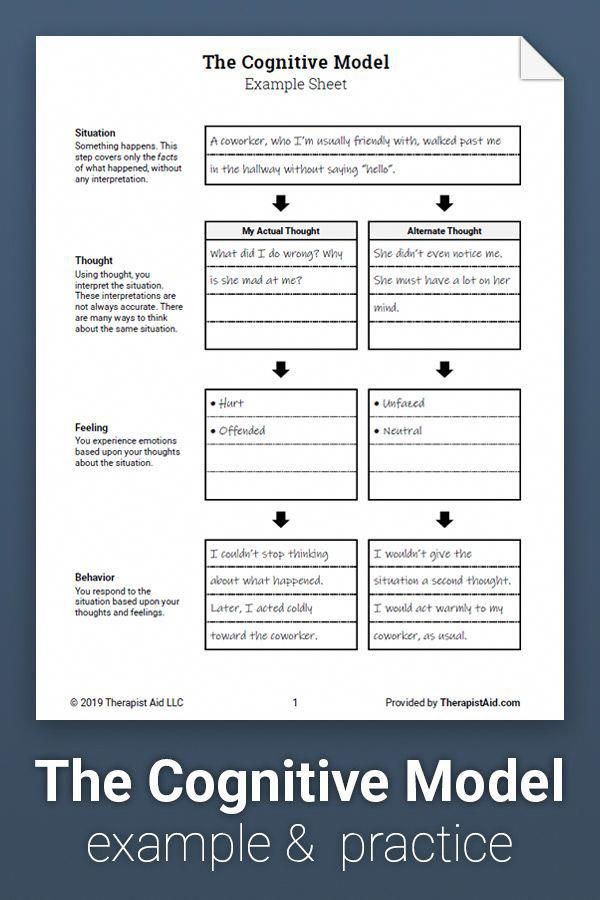

Therapists use a variety of techniques to aid patients in reducing symptoms and improving functioning. Therapists employing CBT may encourage patients to re-evaluate their thinking patterns and assumptions in order to identify unhelpful patterns (often termed “distortions”) in thoughts, such as overgeneralizing bad outcomes, negative thinking that diminishes positive thinking, and always expecting catastrophic outcomes, to more balanced and effective thinking patterns. These are intended to help the person reconceptualize their understanding of traumatic experiences, as well as their understanding of themselves and their ability to cope.

Exposure to the trauma narrative, as well as reminders of the trauma or emotions associated with the trauma, are often used to help the patient reduce avoidance and maladaptive associations with the trauma. Note, this exposure is done in a controlled way, and planned collaboratively by the provider and patient so the patient chooses what they do. The goal is to return a sense of control, self-confidence, and predictability to the patient, and reduce escape and avoidance behaviors.

The goal is to return a sense of control, self-confidence, and predictability to the patient, and reduce escape and avoidance behaviors.

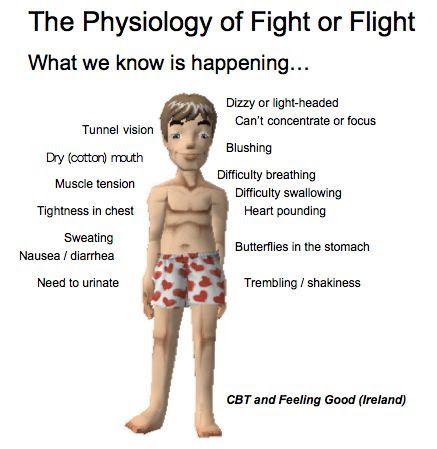

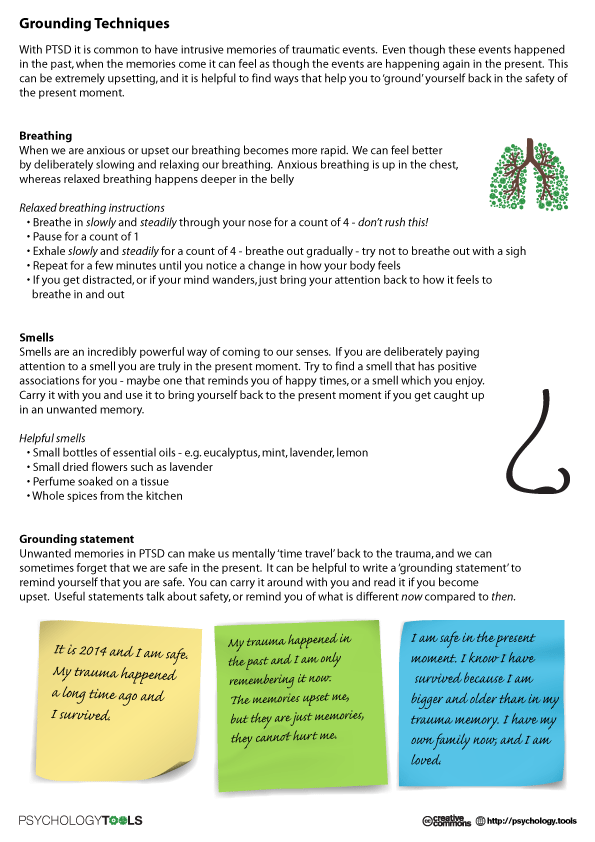

Education about how trauma can affect the person is quite common as is instruction in various methods to facilitate relaxation. Managing stress and planning for potential crises can also be important components of CBT treatment. The provider, with the patient, has some latitude in selecting which elements of cognitive behavioral therapy are likely to be most effective with any particular individual.

Case Example

Jill, a 32-year-old Afghanistan War veteran

Jill had been experiencing PTSD symptoms for more than five years. She consistently avoided thoughts and images related to witnessing her fellow service members being hit by an improvised explosive device (IED). This case example explains how Jill's therapist used a cognitive worksheet as a starting point for engaging in Socratic dialogue.

For Patients & Families

What is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?

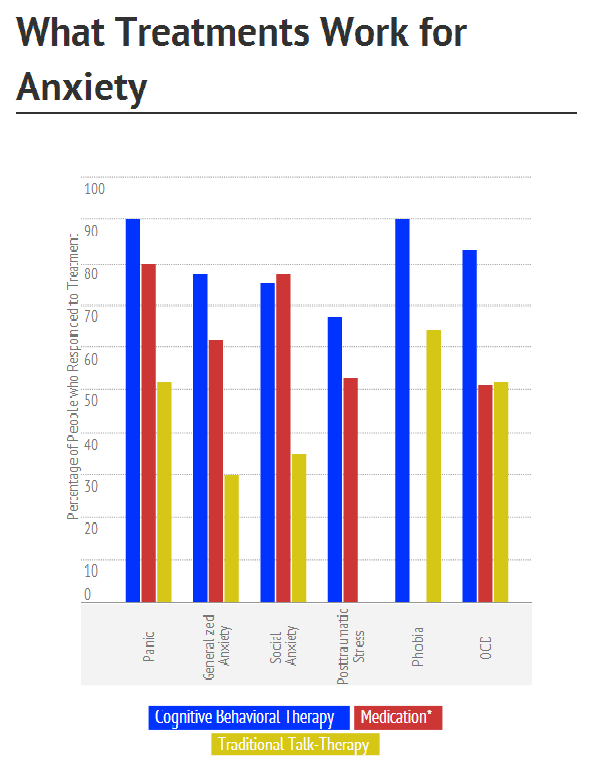

CBT has been demonstrated to be effective for a range of problems including depression, anxiety disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder. In many studies, CBT has been demonstrated to be as effective as, or more effective than, other forms of psychological therapy or psychiatric medications.

References & Resources

Journal Article

Benight, C. C., & Bandura, A. (2004). Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(10), 1129–1148.

Book

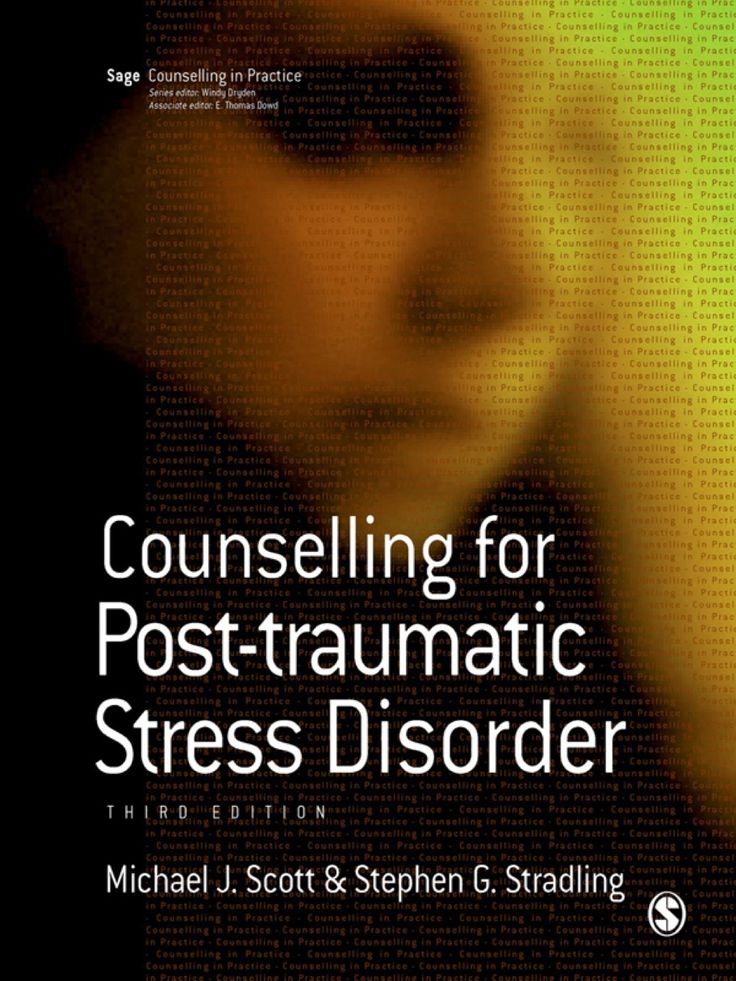

Monson, C. M. & Shnaider, P. (2014). Treating PTSD with cognitive-behavioral therapies: Interventions that work. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Book

Ehlers, A. (2013). Trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. In Simos, G., & Hofmann, S. G. (eds). CBT for anxiety disorders: A practitioner book

(pp. 161-190). New York, NY: Wiley.

(2013). Trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. In Simos, G., & Hofmann, S. G. (eds). CBT for anxiety disorders: A practitioner book

(pp. 161-190). New York, NY: Wiley.

Journal Article

Rauch, S., & Foa, E. (2006). Emotional processing theory (EPT) and exposure therapy for PTSD. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 36(2), 61-65. doi: 10.1007/s10879-006-9008-y

Book

Grey, N. (Ed.) (2009). A casebook of cognitive therapy for traumatic stress reactions. Hove, UK: Routledge.

Updated July 31, 2017

Date created: March 2017

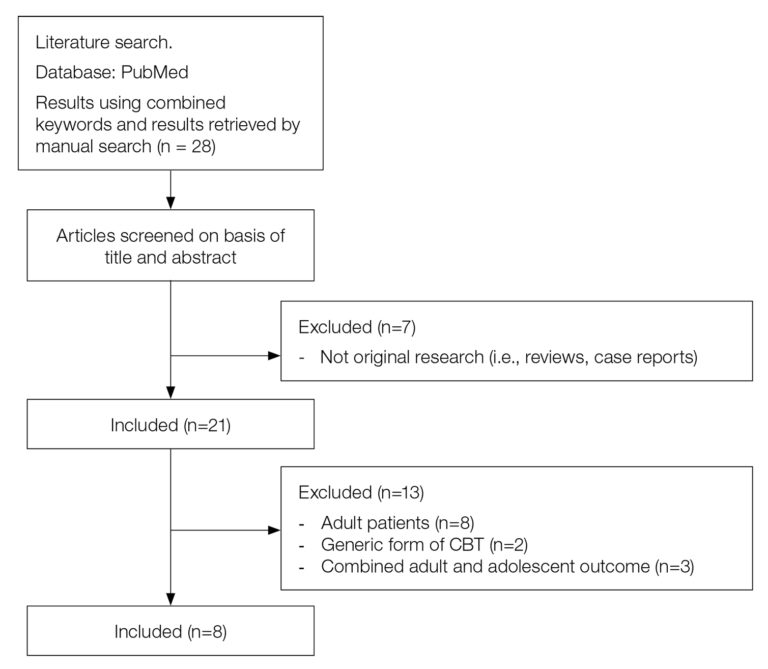

Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a review

1. Klein B, Mitchell J, Gilson K, et al. A therapist-assisted Internet-based CBT intervention for posttraumatic stress disorder: Preliminary results. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38(2):12–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38(2):12–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Bisson JI. Post-traumatic stress disorder. Clin Evid (Online) 2007;pii:1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Kolassa IT, Ertl V, Eckart C, et al. Association study of trauma load and SLC6A4 promoter polymorphism in posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence from survivors of the Rwandan genocide. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):543–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

5. Cahill SP, Foa EB, Hembree EA, Marshall RD, Nacash N. Dissemination of exposure therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19(5):597–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. National Institute for Clinical Excellence . London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2005. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): The management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. NICE Clinical Guideline No. 26. [Google Scholar]

NICE Clinical Guideline No. 26. [Google Scholar]

7. Garakani A, Hirschowitz J, Katz CL. General disaster psychiatry. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004;27(3):391–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Expert Consensus Panel The expert consensus guideline series. Treatment of Posttraumatic stress disorder. The Expert Consensus Panels for PTSD. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 16):3–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Forbes D, Creamer M, Phelps A, et al. Australian guidelines for the treatment of adults with acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41(8):637–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Bisson JI, Tavakoly B, Witteveen AB, et al. TENTS guidelines: Development of post-disaster psychosocial care guidelines through a Delphi process. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Sijbrandij M, Olff M, Reitsma JB, Carlier IV, de Vries MH, Gersons BP. Treatment of acute posttraumatic stress disorder with brief cognitive behavioral therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(1):82–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(1):82–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Cottraux J, Note I, Yao SN, et al. Randomized controlled comparison of cognitive behavior therapy with Rogerian supportive therapy in chronic post-traumatic stress disorder: A 2-year follow-up. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(2):101–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Van Emmerik AA, Kamphuis JH, Emmelkamp PM. Treating acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder with cognitive behavioral therapy or structured writing therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(2):93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Hien DA, Cohen LR, Miele GM, Litt LC, Capstick C. Promising treatments for women with comorbid PTSD and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1426–1432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Mueser KT, Rosenberg SD, Xie H, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol.![]() 2008;76(2):259–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2008;76(2):259–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Shemesh E, Annunziato RA, Weatherley BD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the safety and promise of cognitive-behavioral therapy using imaginal exposure in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder resulting from cardiovascular illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(2):168–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. DuHamel KN, Mosher CE, Winkel G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce post-traumatic stress disorder and distress symptoms after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(23):3754–3761. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Zoellner T, Rabe S, Karl A, Maercker A. Post-traumatic growth as outcome of a cognitive-behavioural therapy trial for motor vehicle accident survivors with PTSD. Psychol Psychother. 2010 Aug 10; [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Rabe S, Zoellner T, Beauducel A, Maercker A, Karl A. Changes in brain electrical activity after cognitive behavioral therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in patients injured in motor vehicle accidents. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(1):13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Changes in brain electrical activity after cognitive behavioral therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in patients injured in motor vehicle accidents. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(1):13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Rabe S, Dörfel D, Zöllner T, Maercker A, Karl A. Cardiovascular correlates of motor vehicle accident related posttraumatic stress disorder and its successful treatment. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2006;31(4):315–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Maercker A, Zöllner T, Menning H, Rabe S, Karl A. Dresden PTSD treatment study: Randomized controlled trial of motor vehicle accident survivors. BMC Psychiatry. 2006;6:29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Malta LS, et al. One- and two-year prospective follow-up of cognitive behavior therapy or supportive psychotherapy. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(7):745–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Beck JG, Coffey SF, Foy DW, Keane TM, Blanchard EB. Group cognitive behavior therapy for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: An initial randomized pilot study. Behav Ther. 2009;40(1):82–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Behav Ther. 2009;40(1):82–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Devineni T, et al. A controlled evaluation of cognitive behavioural therapy for posttraumatic stress in motor vehicle accident survivors. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(1):79–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Difede J, Malta LS, Best S, et al. A randomized controlled clinical treatment trial for World Trade Center attack-related PTSD in disaster workers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(10):861–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Litz BT, Engel CC, Bryant RA, Papa A. A randomized, controlled proof-of-concept trial of an Internet-based, therapist-assisted self-management treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1676–1683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Paunovic N, Ost LG. Cognitive-behavior therapy vs exposure therapy in the treatment of PTSD in refugees. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39(10):1183–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Hinton DE, Hofmann SG, Pollack MH, Otto MW. Mechanisms of efficacy of CBT for Cambodian refugees with PTSD: Improvement in emotion regulation and orthostatic blood pressure response. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2009;15(3):255–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mechanisms of efficacy of CBT for Cambodian refugees with PTSD: Improvement in emotion regulation and orthostatic blood pressure response. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2009;15(3):255–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Otto MW, Hinton D, Korbly NB, et al. Treatment of pharmacotherapy-refractory posttraumatic stress disorder among Cambodian refugees: A pilot study of combination treatment with cognitive-behavior therapy vs sertraline alone. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(11):1271–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pich V, Safren SA, Hofmann SG, Pollack MH. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavior therapy for Cambodian refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks: A cross-over design. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(6):617–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Iyengar S. Community treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder for children exposed to intimate partner violence: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(1):16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2011;165(1):16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Foa EB, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC. An evaluation of three brief programs for facilitating recovery after assault. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19(1):29–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. McDonagh A, Friedman M, McHugo G, et al. Randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(3):515–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Smith P, Yule W, Perrin S, Tranah T, Dalgleish T, Clark DM. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD in children and adolescents: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(8):1051–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Perel JM, Staron V. A pilot randomized controlled trial of combined trauma-focused CBT and sertraline for childhood PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(7):811–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Cohen JA, Steer RA. A follow-up study of a multisite, randomized, controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(12):1474–1484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Cohen JA, Steer RA. A follow-up study of a multisite, randomized, controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(12):1474–1484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Knudsen K. Treating sexually abused children: 1 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29(2):135–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Steer RA. A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(4):393–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Hollifield M, Sinclair-Lian N, Warner TD, Hammerschlag R. Acupuncture for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled pilot trial. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(6):504–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Knaevelsrud C, Maercker A. Internet-based treatment for PTSD reduces distress and facilitates the development of a strong therapeutic alliance: A randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Devilly GJ, Spence SH. The relative efficacy and treatment distress of EMDR and a cognitive-behavior trauma treatment protocol in the amelioration of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 1999;13(1–2):131–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Levitt JT, Malta LS, Martin A, Davis L, Cloitre M. The flexible application of a manualized treatment for PTSD symptoms and functional impairment related to the 9/11 World Trade Center attack. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(7):1419–1433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Brewin CR, Fuchkan N, Huntley Z, et al. Outreach and screening following the 2005 London bombings: Usage and outcomes. Psychol Med. 2010;40(12):2049–2057. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Gillespie K, Duffy M, Hackmann A, Clark DM. Community based cognitive therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder following the Omagh bomb. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(4):345–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Miyahira SD, Folen RA, Hoffman HG, Garcia-Palacios A, Schaper KM. Effectiveness of brief VR treatment for PTSD in war-fighters: A case study. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010;154:214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Beidel DC, Frueh BC, Uhde TW, Wong N, Mentrikoski JM. Multicomponent behavioral treatment for chronic combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(2):224–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Otis JD, Keane TM, Kerns RD, Monson C, Scioli E. The development of an integrated treatment for veterans with comorbid chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain Med. 2009;10(7):1300–1311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Jaycox LH, Zoellner L, Foa EB. Cognitive-behavior therapy for PTSD in rape survivors. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58(8):891–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Nishith P, Duntley SP, Domitrovich PP, Uhles ML, Cook BJ, Stein PK. Effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on heart rate variability during REM sleep in female rape victims with PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16(3):247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Trauma Stress. 2003;16(3):247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, et al. Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: Outcome at academic and community clinics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(5):953–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Ponniah K, Hollon SD. Empirically supported psychological treatments for adult acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: A review. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(12):1086–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Beck JG, Coffey SF. Group cognitive behavioral treatment for PTSD: Treatment of motor vehicle accident survivors. Cogn Behav Pract. 2005;12(3):267–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Taylor S, Fedoroff IC, Koch WJ, Thordarson DS, Fecteau G, Nicki RM. Posttraumatic stress disorder arising after road traffic collisions: Patterns of response to cognitive-behavior therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(3):541–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Palic S, Elklit A. Psychosocial treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in adult refugees: A systematic review of prospective treatment outcome studies and a critique. J Affect Disord. 2010 Aug 12; [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Hinton DE, Pham T, Tran M, Safren SA, Otto MW, Pollack MH. CBT for Vietnamese refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks: A pilot study. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17(5):429–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Basͅoğlu M, Ekblad S, Bäärnhielm S, Livanou M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of tortured asylum seekers: A case study. J Anxiety Disord. 2004;18(3):357–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Zayfert C, DeViva JC. Residual insomnia following cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17(1):69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. DeViva JC, Zayfert C, Pigeon WR, Mellman TA. Treatment of residual insomnia after CBT for PTSD: Case studies. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(2):155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(2):155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Shemesh E, Koren-Michowitz M, Yehuda R, et al. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in patients who have had a myocardial infarction. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(3):231–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Lennmarken C, Sydsjo G. Psychological consequences of awareness and their treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2007;21(3):357–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Ayers S, McKenzie-McHarg K, Eagle A. Cognitive behaviour therapy for postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder: Case studies. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;28(3):177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Lapp LK, Agbokou C, Peretti CS, Ferreri F. Management of post traumatic stress disorder after childbirth: A review. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;31(3):113–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Wagner AW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: Applications to injured trauma survivors. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2003;8(3):175–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2003;8(3):175–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Williams WH, Evans JJ, Wilson BA. Neurorehabilitation for two cases of post-traumatic stress disorder following traumatic brain injury. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2003;8(1):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Eksi A, Braun KL. Over-time changes in PTSD and depression among children surviving the 1999 Istanbul earthquake. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18(6):384–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Shooshtary MH, Panaghi L, Moghadam JA. Outcome of cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescents after natural disaster. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(5):466–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Hamblen JL, Norris FH, Gibson L, Lee L. Training community therapists to deliver cognitive behavioral therapy in the aftermath of disaster. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2010;12(1):33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Hamblen JL, Norris FH, Pietruszkiewicz S, Gibson LE, Naturale A, Louis C. Cognitive behavioral therapy for postdisaster distress: A community based treatment program for survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(3):206–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(3):206–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Harvey AG, Bryant RA, Tarrier N. Cognitive behaviour therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23(3):501–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Bisson J, Andrew M. Psychological treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD003388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Kar N, Mohapatra PK, Nayak KC, Pattnaik P, Swain SP, Kar HC. Post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents one year after a super-cyclone in Orissa, India: Exploring cross-cultural validity and vulnerability factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Kar N, Bastia BK. Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and generalised anxiety disorder in adolescents after a natural disaster: A study of comorbidity. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Silva RR, Cloitre M, Davis L, et al. Early intervention with traumatized children. Psychiatr Q. 2003;74(4):333–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Early intervention with traumatized children. Psychiatr Q. 2003;74(4):333–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Donnelly CL, Amaya-Jackson L. Post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment options. Paediatr Drugs. 2002;4(3):159–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Scheeringa MS, Salloum A, Arnberger RA, Weems CF, Amaya-Jackson L, Cohen JA. Feasibility and effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in preschool children: Two case reports. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(4):631–636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Adler-Nevo G, Manassis K. Psychosocial treatment of pediatric post-traumatic stress disorder: The neglected field of single-incident trauma. Depress Anxiety. 2005;22(4):177–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. March JS, Amaya-Jackson L, Murray MC, Schulte A. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder after a single-incident stressor. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(6):585–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(6):585–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Kar N. Psychological impact of disasters on children: Review of assessment and interventions. World J Pediatr. 2009;5(1):5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Giannopoulou I, Dikaiakou A, Yule W. Cognitive-behavioural group intervention for PTSD symptoms in children following the Athens 1999 earthquake: A pilot study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;11(4):543–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Cohen JA, Berliner L, Mannarino AP. Psychosocial and pharmacological interventions for child crime victims. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16(2):175–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Ehntholt KA, Yule W. Practitioner review: Assessment and treatment of refugee children and adolescents who have experienced war-related trauma. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(12):1197–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, et al. A school-based mental health program for traumatized Latino immigrant children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(3):311–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(3):311–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Khamis V. Post-traumatic stress and psychiatric disorders in Palestinian adolescents following intifada-related injuries. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(8):1199–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Cohen JA. Treating acute posttraumatic reactions in children and adolescents. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(9):827–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. King NJ, Heyne D, Tonge BJ, et al. Sexually abused children suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder: Assessment and treatment strategies. Cogn Behav Ther. 2003;32(1):2–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris C, Acquilano S, Xie H, Alterman AI, Weiss RD. A cognitive behavioral therapy for co-occurring substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders. Addict Behav. 2009;34(10):892–897. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Mendes DD, Mello MF, Ventura P, Passarela Cde M, Mari Jde J. A systematic review on the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2008;38(3):241–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Int J Psychiatry Med. 2008;38(3):241–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Bisson JI, Ehlers A, Matthews R, Pilling S, Richards D, Turner S. Psychological treatments for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Seidler GH, Wagner FE. Comparing the efficacy of EMDR and trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of PTSD: A meta-analytic study. Psychol Med. 2006;36(11):1515–1522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Olff M, Langeland W, Witteveen A, Denys D. A psychobiological rationale for oxytocin in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(8):522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Schottenbauer MA, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB, Tendick V, Gray SH. Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: Review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry. 2008;71(2):134–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Bryant RA, Felmingham K, Kemp A, et al. Amygdala and ventral anterior cingulate activation predicts treatment response to cognitive behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 2008;38(4):555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Amygdala and ventral anterior cingulate activation predicts treatment response to cognitive behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 2008;38(4):555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. Zayfert C, Deviva JC, Becker CB, Pike JL, Gillock KL, Hayes SA. Exposure utilization and completion of cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD in a “real world” clinical practice. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(6):637–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Bryant RA, Moulds ML, Nixon RD, Mastrodomenico J, Felmingham K, Hopwood S. Hypnotherapy and cognitive behaviour therapy of acute stress disorder: A 3-year follow-up. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(9):1331–1315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Bryant RA, Moulds ML, Nixon RV. Cognitive behaviour therapy of acute stress disorder: A four-year follow-up. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(4):489–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Durham RC, Chambers JA, Power KG, et al. Long-term outcome of cognitive behaviour therapy clinical trials in central Scotland. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9(42):1–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Health Technol Assess. 2005;9(42):1–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Rose S, Bisson J, Churchill R, Wessely S. Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD000560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Aulagnier M, Verger P, Rouillon F. [Efficiency of psychological debriefing in preventing post-traumatic stress disorders] Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2004;52(1):67–79. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Bryant RA, Harvey AG, Dang ST, Sackville T, Basten C. Treatment of acute stress disorder: A comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(5):862–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. Ehlers A, Clark D. Early psychological interventions for adult survivors of trauma: A review. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(9):817–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. Kornør H, Winje D, Ekeberg Ø, et al. Early trauma-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy to prevent chronic post-traumatic stress disorder and related symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Roberts NP, Kitchiner NJ, Kenardy J, Bisson JI. Systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple-session early interventions following traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(3):293–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. Whealin JM, Ruzek JI, Southwick S. Cognitive-behavioral theory and preparation for professionals at risk for trauma exposure. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2008;9(2):100–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Zatzick DF, Koepsell T, Rivara FP. Using target population specification, effect size, and reach to estimate and compare the population impact of two PTSD preventive interventions. Psychiatry. 2009;72(4):346–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Roberts NP, Kitchiner NJ, Kenardy J, Bisson J. Multiple session early psychological interventions for the prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD006869. 8; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Hetrick SE, Purcell R, Garner B, Parslow R. Combined pharmacotherapy and psychological therapies for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;7:CD007316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hetrick SE, Purcell R, Garner B, Parslow R. Combined pharmacotherapy and psychological therapies for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;7:CD007316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Garakani A, Mathew SJ, Charney DS. Neurobiology of anxiety disorders and implications for treatment. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73(7):941–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Rodrigues H, Figueira I, Gonçalves R, Mendlowicz M, Macedo T, Ventura P. CBT for pharmacotherapy non-remitters – a systematic review of a next-step strategy. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1–3):219–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Udomratn P. Mental health and the psychosocial consequences of natural disasters in Asia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20(5):441–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110. Kar N. Natural disasters in developing countries: Mental health issues. Indian J Med Sci. 2009;63(8):327–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111. Kindt M, Buck N, Arntz A, Soeter M. Perceptual and conceptual processing as predictors of treatment outcome in PTSD. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2007;38(4):491–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2007;38(4):491–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Ehlers A, Clark DM, Hackmann A, et al. Intensive cognitive therapy for PTSD: A feasibility study. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2010;38(4):383–398. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

113. Klein B, Mitchell J, Abbott J, et al. A therapist-assisted cognitive behavior therapy internet intervention for posttraumatic stress disorder: Pre-, post- and 3-month follow-up results from an open trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(6):635–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

114. Germain V, Marchand A, Bouchard S, Drouin MS, Guay S. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy administered by videoconference for posttraumatic stress disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38(1):42–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115. Cohen J, Mannarino AP. Disseminating and implementing trauma-focused CBT in community settings. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2008;9(4):214–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

116. Morsette A, Swaney G, Stolle D, Schuldberg D, van den Pol R, Young M. Cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools (CBITS): School-based treatment on a rural American Indian reservation. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2009;40(1):169–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools (CBITS): School-based treatment on a rural American Indian reservation. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2009;40(1):169–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

117. CATS Consortium Implementing CBT for traumatized children and adolescents after september 11: Lessons learned from the Child and Adolescent Trauma Treatments and Services (CATS) Project. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2007;36(4):581–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118. Friedman MJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder among military returnees from Afghanistan and Iraq. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):586–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119. Kar N. Psychosocial issues following a natural disaster in a developing country: A qualitative longitudinal observational study. Int J Disaster Med. 2006;4:169–176. [Google Scholar]

120. Kar N. Suicidality following a natural disaster. Am J Disaster Med. 2010;5(6):361–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

121. Christensen PN, Cohan SL, Stein MB. The relationship between interpersonal perception and post-traumatic stress disorder-related functional impairment: A social relations model analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2004;33(3):151–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The relationship between interpersonal perception and post-traumatic stress disorder-related functional impairment: A social relations model analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2004;33(3):151–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122. Scher CD, Resick PA. Hopelessness as a risk factor for post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among interpersonal violence survivors. Cogn Behav Ther. 2005;34(2):99–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

123. Kar N, Misra BN. Mental Health Care Following Disasters. Bhubaneswar: Quality of Life Research and Development Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

124. Hembree EA, Foa EB. Posttraumatic stress disorder: Psychological factors and psychosocial interventions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(Suppl 7):33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

125. Holmes EA, Arntz A, Smucker MR. Imagery rescripting in cognitive behaviour therapy: Images, treatment techniques and outcomes. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2007;38(4):297–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

126. Grunert BK, Weis JM, Smucker MR, Christianson HF. Imagery rescripting and reprocessing therapy after failed prolonged exposure for post-traumatic stress disorder following industrial injury. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2007;38(4):317–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grunert BK, Weis JM, Smucker MR, Christianson HF. Imagery rescripting and reprocessing therapy after failed prolonged exposure for post-traumatic stress disorder following industrial injury. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2007;38(4):317–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

127. Karl A, Malta LS, Alexander J, Blanchard EB. Startle responses in motor vehicle accident survivors: A pilot study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2004;29(3):223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

128. Wild J, Gur RC. Verbal memory and treatment response in post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(3):254–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Borderline Personality Disorder Symptom Test

Borderline Personality Disorder includes many different symptoms that in one way or another indicate the presence of this mental disorder. However, the severity of the disease and its symptoms can vary greatly.

This test incorporates the results of previous studies to ensure the validity and reliability of results for borderline personality disorder symptoms.

Do you have symptoms of borderline disorder? For each following statement, indicate how much you agree with it.

The Borderline Personality Disorder Test (IDR-BPDST) is owned by IDRlabs. It builds on the work of Dr. M. Zanarini and her colleagues who created the Mental Disorder Symptom Inventory (MSI-BPD). This test is not affiliated with any particular researcher or organization in the field of psychopathology.

The Borderline Personality Disorder test is based on material that has been published in the following sources: Zanarini, Mary & Vujanovic, A & Parachini, Elizabeth & Villatte, Jennifer & Frankenburg, Frances & Hennen, John. (2003). A screening measure for BPD: The McLean screening instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). Journal of personality disorders. 17.568-73. 10.1521/pedi.17.6.568.25355. Keng SL, Lee Y, Drabu S, Hong RY, Chee CYI, Ho CSH, Ho RCM. Construct Validity of the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder in Two Singaporean Samples. J Pers Discord. 2019Aug; 33(4): 450-469. Epub 2018 Jun 27 PMID: 29949444. Kröger C, Huget F, Roepke S. Diagnostische Effizienz des McLean Screening Instrument für Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung in einer Stichprobe, die eine stationäre, störungsspezifische Behandlung in Anspruch nehmen möchte [Diagnostic Instrument for Leagnostic accuracy of borderline personality disorder in an inpatient sample who seek a disorder-specific treatment]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. Nov 2011; 61(11):481-6. German. Epub 2011 Nov 11 PMID: 22081467.

J Pers Discord. 2019Aug; 33(4): 450-469. Epub 2018 Jun 27 PMID: 29949444. Kröger C, Huget F, Roepke S. Diagnostische Effizienz des McLean Screening Instrument für Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung in einer Stichprobe, die eine stationäre, störungsspezifische Behandlung in Anspruch nehmen möchte [Diagnostic Instrument for Leagnostic accuracy of borderline personality disorder in an inpatient sample who seek a disorder-specific treatment]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. Nov 2011; 61(11):481-6. German. Epub 2011 Nov 11 PMID: 22081467.

The work of Dr. Zanarini and her colleagues looks at the main symptoms that are characteristic of borderline personality disorder. This paper also describes certain diagnostic criteria that have been used in the studies. This test provides information for educational purposes only. IDRlabs and this test are in no way affiliated with the above researchers, organizations or institutions.

The borderline personality disorder symptom test relies on known research on the condition and other psychiatric disorders. However, all free online tests like this one are only introductory materials that will not be able to determine your inherent qualities with absolute accuracy and reliability. Therefore, our test provides information for educational purposes only. Detailed information about your mental state can only be provided by a certified specialist.

However, all free online tests like this one are only introductory materials that will not be able to determine your inherent qualities with absolute accuracy and reliability. Therefore, our test provides information for educational purposes only. Detailed information about your mental state can only be provided by a certified specialist.

As the authors of this free online borderline personality disorder symptom ratio test, we have made every effort to ensure that this test is reliable and valid through numerous tests and statistical data controls. However, free online tests like this provide information "as is" and should not be construed as providing professional or certified advice of any kind. For more information about our online tests, please see our Terms of Service.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

FAA | Views: 1237

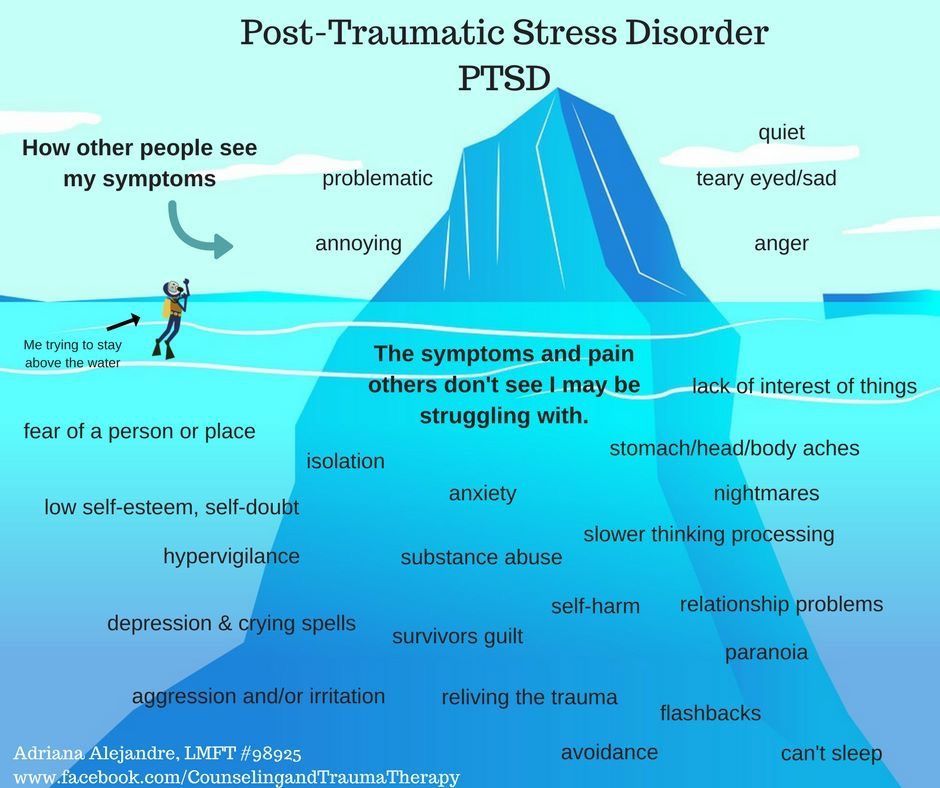

PTSD can be a debilitating condition, but professional advice can help.

November 11, we remember the Canadian soldiers who fought in battle and gave their lives. But many soldiers who have returned from the war face a new battle: post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). While the media tends to focus on combat veterans, many other Canadians are also struggling with unresolved trauma and PTSD.

But many soldiers who have returned from the war face a new battle: post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). While the media tends to focus on combat veterans, many other Canadians are also struggling with unresolved trauma and PTSD.

How common is it?

According to a 2008 study, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD in Canadians is 9.2 percent. Just over 76 percent of respondents reported that being exposed to trauma is severe enough to trigger PTSD. About one in 10 Canadians will experience this debilitating condition at some point in their lives.

What is this?

Simply put, PTSD is how your body and brain respond to stress or trauma. To receive a diagnosis of PTSD, patients must meet a list of criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), and these symptoms must last longer than a month.

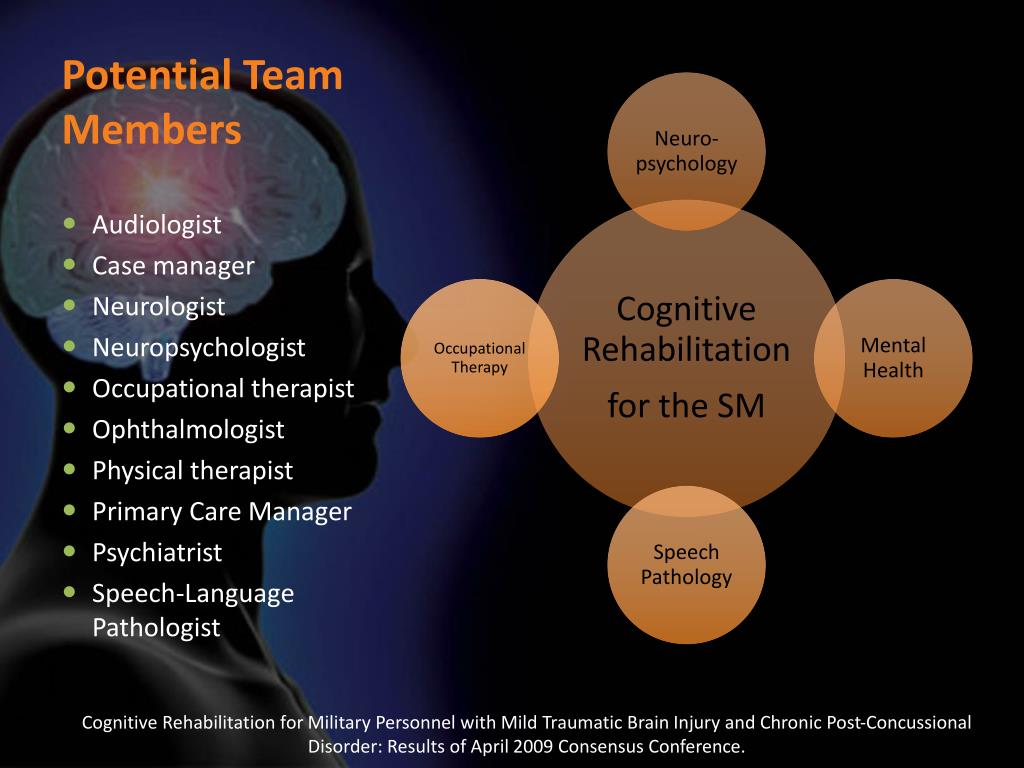

David Rabbi, MA (Counseling Psychology) and Registered Clinical Advisor, included trauma work in his practice about five years ago.

“Trauma affects people at a very deep level, not only physical symptoms but also psychological symptoms: impact on self-awareness and self-esteem. When a trauma work is successful, it has a big impact on people's lives,” says the rabbi.

When a trauma work is successful, it has a big impact on people's lives,” says the rabbi.

Various events can lead to trauma or PTSD, including

sexual and physical abuse in childhood

rape, assault or other violent crime

serious traffic accidents, including multiple traffic accidents

aggravated grief due to the death of a loved one

witness to a traumatic crime or death

survivors of natural disasters

war trauma as a soldier or civilian living in a war zone

“Trauma symptoms and life events from 40 or 50 years ago that still affect some people and they didn't know about it,” says the rabbi. “For example, clients who have suffered childhood abuse do not fully appreciate the impact these events have on their lives. "

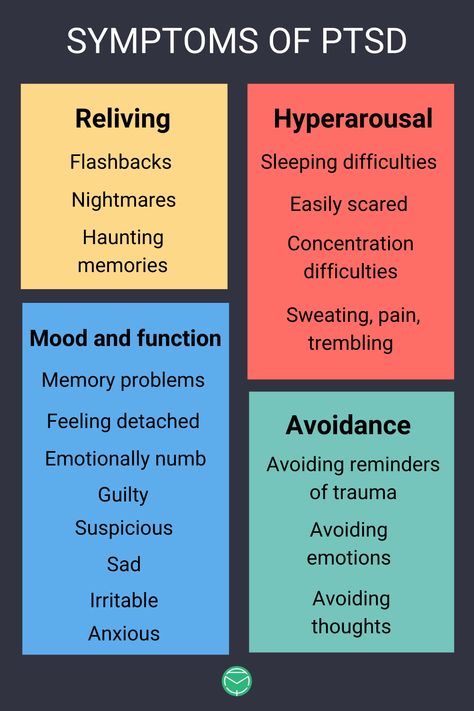

Symptoms

Some of the symptoms people with PTSD struggle with are:

low mood, often accompanied by depression and anxiety

negative thinking

repetitive thoughts about the event

nightmares

flashbacks

avoidance of stimuli associated with the event

forms of dissociation

addiction

"On the other hand, the symptoms of overexcitation, wakefulness, and the fear response are activated," says the rabbi. “Sometimes there is aggression associated with PTSD. There's a very wide range of symptoms that are similar to many other conditions, so it's not obvious that a person is suffering from trauma or PTSD. "

“Sometimes there is aggression associated with PTSD. There's a very wide range of symptoms that are similar to many other conditions, so it's not obvious that a person is suffering from trauma or PTSD. "

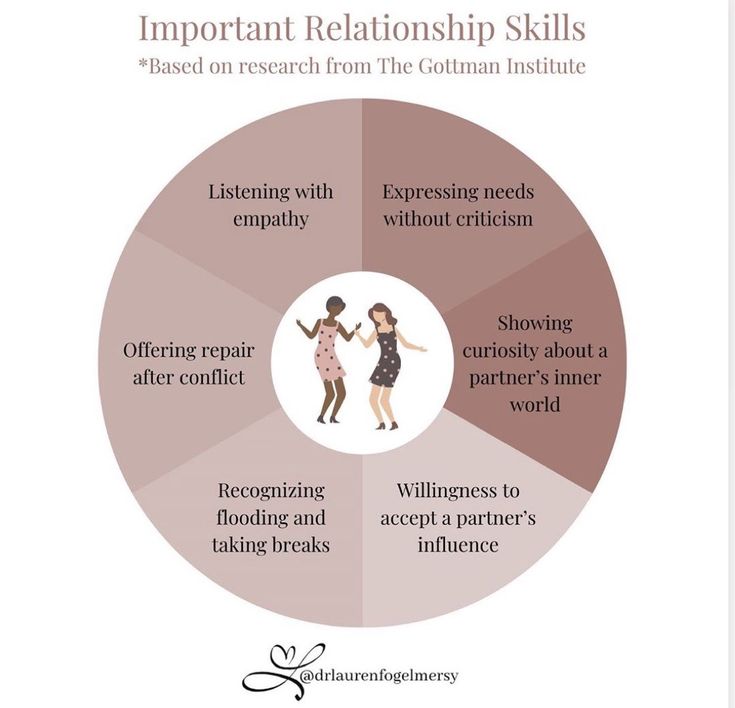

Relationships with spouses, families, colleagues and friends are negatively affected when a person suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Treatment

A counselor can use a variety of techniques to help people from all walks of life cope with—and in many cases overcome—PTSD.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

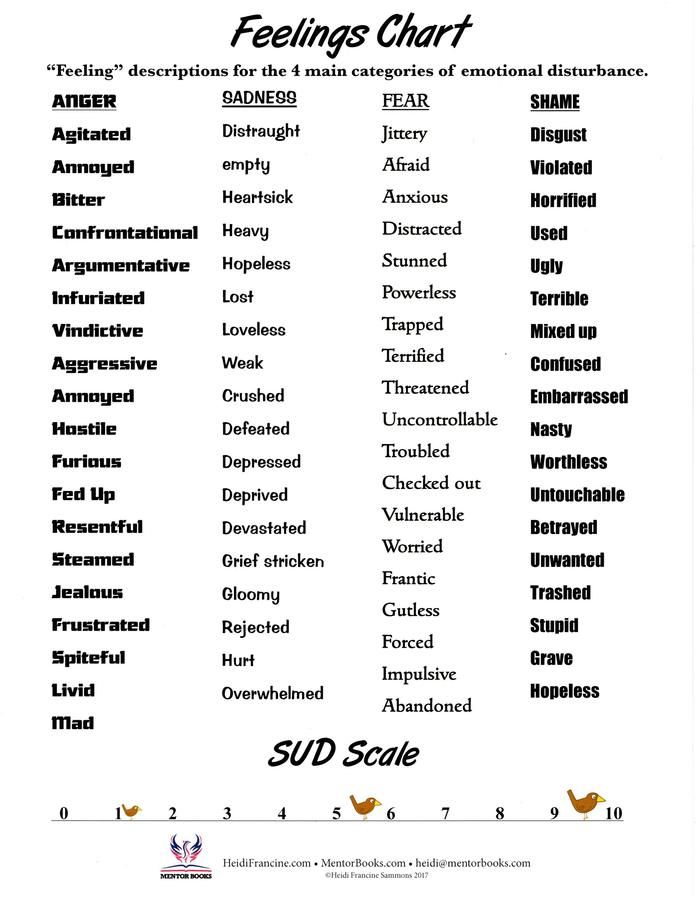

CBT focuses on people's thoughts and actions. How we think about a situation affects how we feel about it and how we act. Our feelings may not be realistic, and the actions we take in a given situation, such as avoidance, may not be healthy. Through CBT, the counselor helps patients learn new, healthy ways to replace useless thoughts, feelings, and behaviors so they can move forward in their lives.

A 2011 review of CBT found that it was effective in treating acute (sudden) and chronic (long-term) PTSD in adults and children. CBT has been found to be useful for treating PTSD resulting from sexual assault, natural disasters, war, trauma, and traffic accidents. Patient rates can be as high as 50 percent, according to some studies, but overall CBT has proven to be just as effective as other psychological therapies for treating PTSD.

CBT has been found to be useful for treating PTSD resulting from sexual assault, natural disasters, war, trauma, and traffic accidents. Patient rates can be as high as 50 percent, according to some studies, but overall CBT has proven to be just as effective as other psychological therapies for treating PTSD.

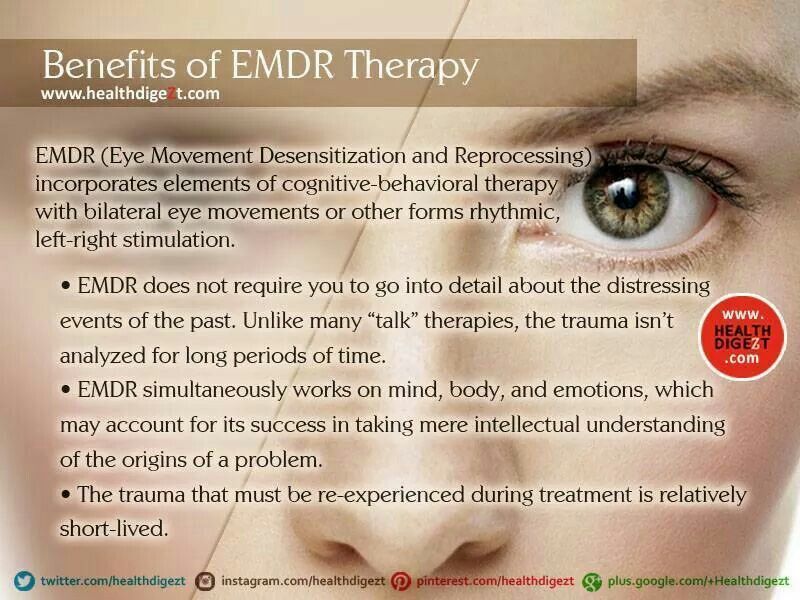

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

This therapy is the cornerstone of the Rabbi's work with trauma. In 1987, American psychologist Francine Shapiro discovered that certain eye movements appeared to reduce the power of anxious thoughts. It started with the help of the DPDH to treat the wounded.

In the words of the rabbi, “trauma is an event that was so overwhelming in the first place that it is not fully processed by the [brain] so that when there is a reminder of it—some kind of external or internal cue—the brain and body react so like it's happening again. "

The light bar is used in DFG. The client sits in front of him, recalls the event, and allows his eyes to follow the lights as they move back and forth into the light bar.

“While the researchers are not sure why it works, it seems to mimic the rapid eye movement, deep rejuvenating sleep that humans have, which allows them to process the events of the day,” says the rabbi. “Events pop up and disappear from the neural network associated with her. ”

The consultant asks the client “what are you doing?”, and then the client reports. Results vary from client to client. EMDR is not hypnosis, but re-experiencing an event.

“I like to think that the essence of the person is present during the session, watching the event and experiencing the event in such a way that part of the brain was not present at the time of the trauma,” says the rabbi. EMCG helps the client free and integrate events that have been locked in the brain.

Cbt and DPDH are approved by the World Health Organization as a treatment for PTSD.

Group therapy

Group therapy (a type of psychotherapy involving one or more therapists working with several people at the same time) can also be effective for people who have experienced various types of trauma, such as sexual abuse.

Introduction to Therapy

The rabbi uses this method to allow the client to rethink traumatic experiences such as sexual abuse, process it and "do" the things they wish they would have done at the time.

A history of trauma such as childhood abuse, neglect, or sexual abuse makes it more difficult for adults to recover from PTSD. But it's never too late to process and heal the effects of a painful traumatic event with professional counseling to help.

Mind-Body Therapy

Research into these alternative therapies and found them to be useful for treating PTSD.

Yoga

A 2013 study found that veterans who practiced yoga twice a week for six weeks had improved sleep quality and a significant improvement in symptoms of overarousal.

Mindfulness-based stretching and deep breathing

A group of nurses who participated in 60-minute sessions twice a week for eight weeks, normalized cortisol levels and reduced symptoms of PTSD.

Meditation

Loving-kindness meditation was taught by a group of veterans during a 12-week study in 2013. Three months later, reductions were seen in symptoms of depression and PTSD.

Three months later, reductions were seen in symptoms of depression and PTSD.

PTSD: Fighting on the Home Front

Timothy Black, PhD, Associate Professor of Counseling Psychology at the University of Victoria. He is also the co-founder and national clinical director for Veterans' Transition Network. This organization helps Canadian wrestling veterans successfully reintegrate into civilian life. With the help of caregivers and other veterans, many are discovering new formations or careers, and dealing with the demons of PTSD.

Number affected

Despite the extensive amount of research on PTSD, it is difficult to estimate how many veterans return with this condition.

“We heard anywhere from 10 percent to 50 percent of combat veterans. But it's really hard to find good numbers. Even the best stats we have in Canada still have a whole range,” says Black.

Black says the transition from active combat to civilian life creates a sort of culture shock. A soldier can leave the anti-Taliban service, and for a week I will walk the streets of my hometown.

Adjusting life

One of the most difficult things in adapting to life is to return home, leaving war-torn places where, for example, girls have acid thrown in their faces because they want to get an education, and return home to hear Canadians complain about petty Problems. “They're really angry and frustrated with the way people in Canada live because we're one of the best countries in the world and that really worries them. They fight it,” Black explains.

“Alcohol and drugs are also a huge problem for dealing with their symptoms and family relationships. The research I did at the University of Victoria found one of the biggest things they struggle with making friends,” says Black.

Black quit his private practice to focus on working in groups with veterans because it was so successful.

“We hear over and over that it's the band aspect of what we do that makes a big difference. Having a military person in the group [is effective] because they are trained to feel most comfortable and safe in the group.