Can you die from ptsd

Warning Signs of Early Death Found in Veterans with Severe Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | The Brink

But the risk can be reversed with lifestyle changes

Photo by Viktoriia Miroshnikova/iStock

PTSD

But the risk can be reversed with lifestyle changes

November 9, 2022

Twitter Facebook

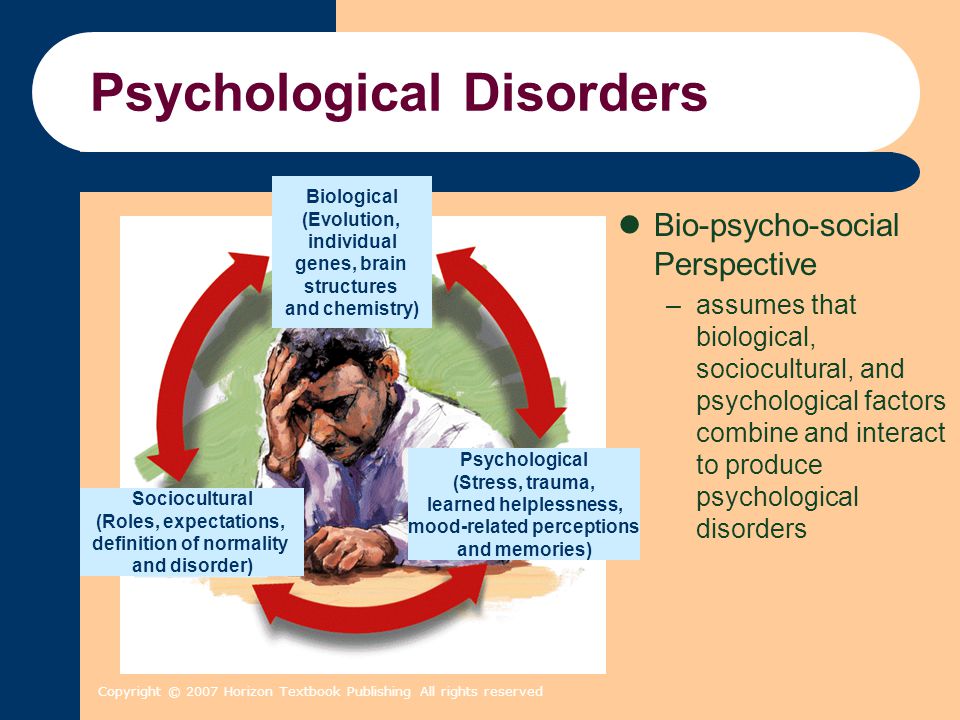

From the time we’re born to the time we die, a lot may change, but our DNA—the long, double-helix molecule that contains all of a person’s genetic code—stays the same. The instructions for reading that code can shift, however, as the chemical tags on and around a DNA sequence change throughout our lives, depending on our age, environment, and behavior. This outside influence on how our genes are read and expressed by cells is called epigenetics—and researchers studying it have discovered clues that may show why some veterans live longer than others.

Scientists can interpret epigenetic changes and patterns by looking at DNA methylation (DNAm), a process that turns a gene “on” or “off. ” (For example, smokers tend to have reduced DNAm in a gene shown to have a role in suppressing tumors, making them more susceptible to disease.) DNAm can also indicate a person’s cellular age, which can be different from their numerical age, and point to risk factors associated with early death.

In a new study of military veterans published in Translational Psychiatry, researchers discovered a connection between DNAm signals of accelerated cellular aging and mental health conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—findings that suggest former service personnel with PTSD are at greater risk of early death.

“Our study found that PTSD and comorbid conditions, like substance misuse, are associated with a cellular marker of early death found in DNA methylation patterns,” says Erika Wolf, a Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine professor of psychiatry and senior author on the study. An early death is one that occurs before the average age of death, which in the United States is about 75 years, but differs slightly between men and women.

The study included two samples of veterans that had representative levels of trauma and other psychiatric conditions, like substance use and personality disorders. One group included 434 veterans in their early 30s, who had served in post-9/11 conflicts; the other group included 647 middle-age veterans and their trauma-exposed spouses. Both groups were assessed for a range of psychological conditions, and had blood drawn to obtain genetic information and to test for levels of a variety of inflammatory molecules.

The data was then put into an existing algorithm called GrimAge—which is designed to predict time to death based on methylation data in a person’s blood and other types of biomarkers—and correlated with a range of psychiatric diagnoses, biomarkers, cognitive tests, and brain morphology. The researchers also accounted for the influence of age.

According to the paper, the veterans’ DNAm index of time to death was associated with a number of adverse clinical outcomes, including high inflammation levels, oxidative stress, alterations in immune and metabolic molecules, and cognitive decline. The results indicated PTSD symptoms were a factor in faster cellular aging—.36 of a year faster, according to Wolf. So, for every year that the cells of someone without PTSD age, the cells of someone with more severe PTSD symptoms age a year and a third.

The results indicated PTSD symptoms were a factor in faster cellular aging—.36 of a year faster, according to Wolf. So, for every year that the cells of someone without PTSD age, the cells of someone with more severe PTSD symptoms age a year and a third.

The study is the first to detect associations between a broad range of trauma-related psychiatric symptoms and some of the earliest warning signs of mortality risk via DNAm patterns. But Wolf, a clinical research psychologist for the National Center for PTSD at the VA Boston Healthcare System, says that a person’s fate is not set in stone and there are ways to avoid the risk of early death. She says the research has important clinical implications, since lifestyle interventions may reverse metrics of biological aging and mitigate premature death.

“Collectively, our findings suggest that a number of psychiatric disorders may increase risk for early death and underscore the importance of identification of those at greatest risk,” Wolf says.

The algorithm isn’t designed to predict a single person’s time of death—if people are worried about their biological health, they’re much better off getting a metabolic panel, says Wolf—but can help identify biological pathways associated with accelerated aging in broader groups. For example, if we know about a particular inflammatory process that is problematic among those with accelerated cellular aging, then scientists can work to develop something to correct that.

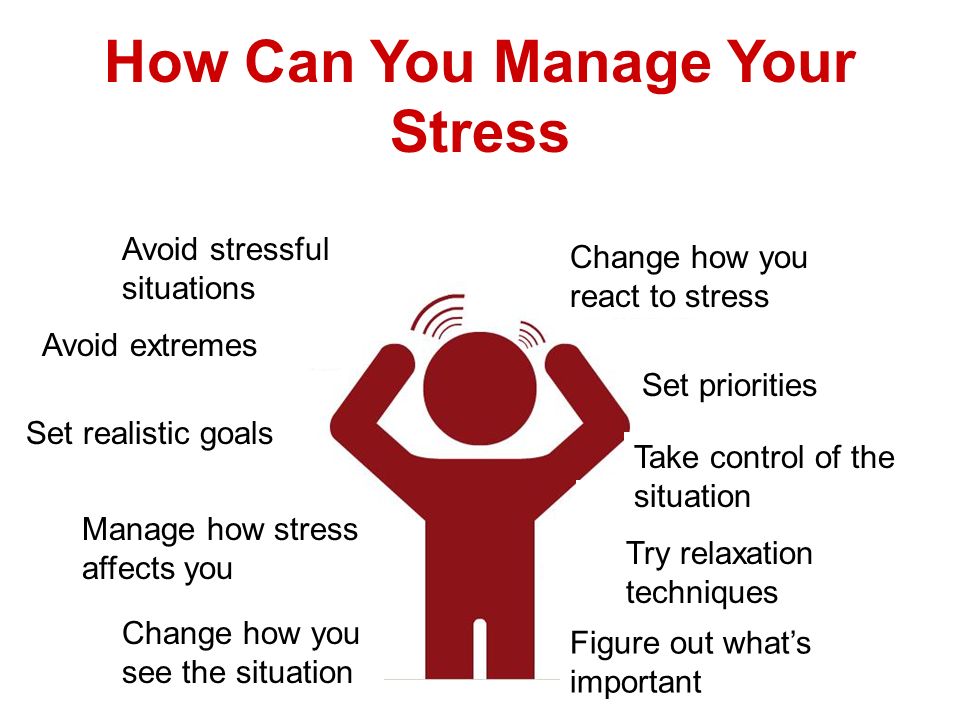

“We know of some health behaviors that reduce inflammation, like exercise and stress reduction, good nutrition,” Wolf says. “The ability to detect low levels of these molecules years before they may become clinically significant, and hopefully be able to intervene early on in disease trajectories, is critical for efforts to ultimately slow or reverse the adverse health consequences of traumatic stress.”

Funding for this study was provided by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute of Mental Health.

Explore Related Topics:

- Aging

- Disease

- Health

- Inflammatory Diseases

- Microbiology & Molecular Biology

- Molecular Biology & Genetics

- Stress

- Veterans

- Wellness

-

Jessica Colarossi

Science Writer Twitter Profile

Jessica Colarossi is a science writer for The Brink. She graduated with a BS in journalism from Emerson College in 2016, with focuses on environmental studies and publishing. While a student, she interned at ThinkProgress in Washington, D.

C., where she wrote over 30 stories, most of them relating to climate change, coral reefs, and women’s health. Profile

C., where she wrote over 30 stories, most of them relating to climate change, coral reefs, and women’s health. Profile -

Gina DiGravio

Gina DiGravio Profile

PTSD with depression may significantly increase risk of early death in women | News

For immediate release: December 4, 2020

Boston, MA – Women with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression have an almost fourfold greater risk of early death from cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, type 2 diabetes, accidents, suicide, and other causes than women without trauma exposure or depression, according to a large long-term study conducted by researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“The study examines longevity—in a way, the ultimate health outcome—and the findings strengthen our understanding that mental and physical health are tightly interconnected,” said Andrea Roberts, lead author of the study and a senior research scientist in the Department of Environmental Health. “This is particularly salient during the pandemic, which is exposing many Americans and others across the world to unusual stress while at the same time reducing social connections, which can be powerfully protective for our mental health.”

“This is particularly salient during the pandemic, which is exposing many Americans and others across the world to unusual stress while at the same time reducing social connections, which can be powerfully protective for our mental health.”

The study, which is the first study of co-occurring PTSD and depression in a large population of civilian women, was published online December 4, 2020 in JAMA Network Open. Previous research on PTSD and depression has primarily focused on men in the military.

Roberts and her colleagues studied more than 50,000 women at midlife (ages 43 to 64 years) and found that women with both high levels of PTSD and depression symptoms were nearly four times more likely to die from nearly every major cause of death over the following nine years than women who did not have depression and had not experienced a traumatic event.

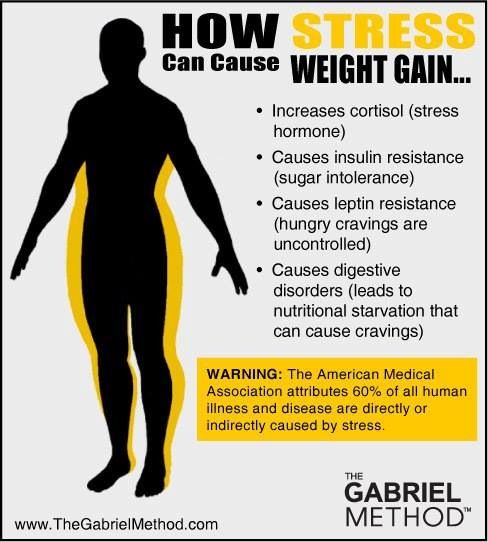

The researchers examined whether health risk factors such as smoking, exercise, and obesity might explain the association between PTSD and depression and premature death, but these factors only explained a relatively small part. This finding suggests that other factors, such as the effect of stress hormones on the body, may account for the higher risk of early death in women with the disorders.

This finding suggests that other factors, such as the effect of stress hormones on the body, may account for the higher risk of early death in women with the disorders.

Treatment of PTSD and depression in women with symptoms of both disorders may reduce their substantial increased risk of mortality, the researchers said.

“These findings provide further evidence that mental health is fundamental to physical health—and to our very survival. We ignore our emotional well-being at our peril,” said Karestan Koenen, senior author of the study and professor of psychiatric epidemiology in the Department of Epidemiology and Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences.

Other Harvard Chan School authors included Laura Kubzansky, Lori Chibnik, and Eric Rimm.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01Mh201269-07 and U01 CA176726).

“Association of posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms with mortality in women: A 9-year prospective cohort study,” Andrea L. Roberts, Laura D. Kubzansky, Lori Chibnik, Eric B. Rimm, Karestan C. Koenen, JAMA Network Open, online December 4, 2020, DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27935

Roberts, Laura D. Kubzansky, Lori Chibnik, Eric B. Rimm, Karestan C. Koenen, JAMA Network Open, online December 4, 2020, DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27935

Photo: Shutterstock/Photo duets

Visit the Harvard Chan School website for the latest news, press releases, and multimedia offerings.

Nicole Rura

617.221.4241

[email protected]

###

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health brings together dedicated experts from many disciplines to educate new generations of global health leaders and produce powerful ideas that improve the lives and health of people everywhere. As a community of leading scientists, educators, and students, we work together to take innovative ideas from the laboratory to people’s lives—not only making scientific breakthroughs, but also working to change individual behaviors, public policies, and health care practices. Each year, more than 400 faculty members at Harvard Chan School teach 1,000-plus full-time students from around the world and train thousands more through online and executive education courses. Founded in 1913 as the Harvard-MIT School of Health Officers, the School is recognized as America’s oldest professional training program in public health.

Founded in 1913 as the Harvard-MIT School of Health Officers, the School is recognized as America’s oldest professional training program in public health.

Share this:FacebookTwitterLinkedInReddit

PTSD

") end if %>

Variant of Acrobat Samana Gaze | Acrobat Reader Samana Download

PTSD is a normal response

for severe traumatic events.

This booklet deals with signs,

symptoms and treatments for PTSD.

New York State

Department of Mental Health

Have you experienced a terrible and dangerous event? Note please, those cases in which you recognize yourself.

- Sometimes, out of the blue, everything that happened to me is happening again. I never know when to expect it again.

- I have nightmares and memories of the terrible incident which I have experienced.

- I avoid places that remind me of that incident.

- I jump on the spot and feel uneasy at any sudden movement or surprise. I feel alert all the time.

- It's hard for me to trust someone and get close to someone.

- Sometimes I just feel emotionally drained and deaf.

- I get angry very easily.

- I am tormented by guilt that others died, but I survived.

- I sleep poorly and experience muscle tension.

PTSD is a very serious condition that needs to be treated.

Many people who have experienced terrible events suffer from this disease.

It is not your fault that you fell ill, and you should not suffer from it.

Read this booklet to find out how you can be helped.

You can get well and enjoy life again!

What is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD/PTSD)?

PTSD is a very serious condition. PTSD symptoms may occur in a person who has experienced a terrible traumatic event. This disease is susceptible medical and therapeutic treatment.

PTSD symptoms may occur in a person who has experienced a terrible traumatic event. This disease is susceptible medical and therapeutic treatment.

PTSD can occur after you:

- Have been a victim of sexual abuse

- Have been a victim of physical or emotional domestic violence

- Victim of a violent crime

- Been in a car accident or plane crash

- Survived a hurricane, tornado, or fire

- Were at war

- Survived a life-threatening event

- Witnessed any of the above events

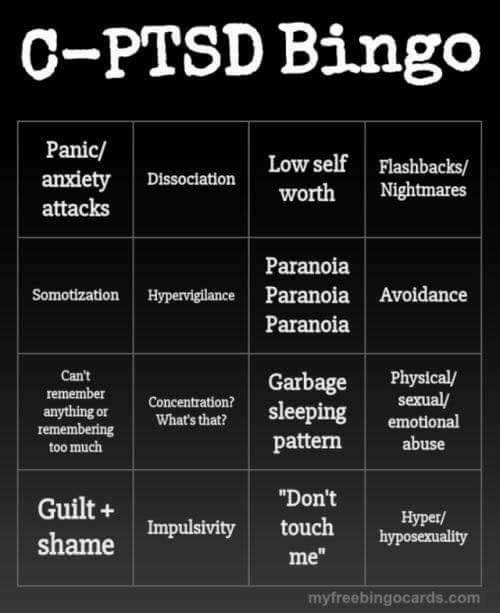

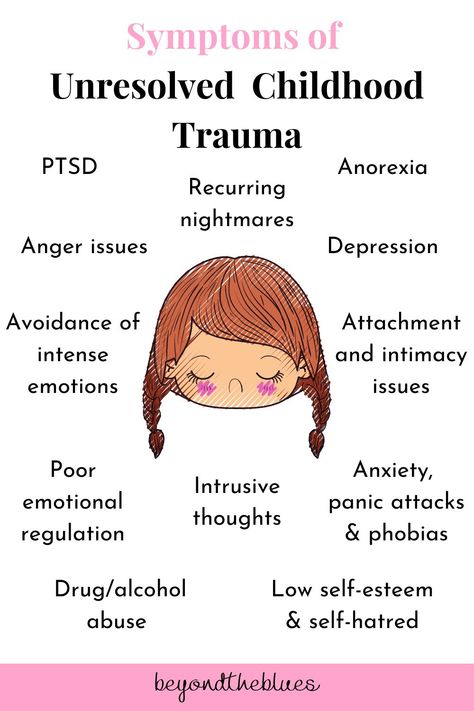

If you have post-traumatic stress disorder, you often have nightmares or memories associated with the event. you try to hold on away from anything that might remind you of the experience.

You are bitter and unable to trust or care for others. You are always on your guard and see a hidden threat in everything. You become not by itself, when something happens suddenly and without warning.

When does PTSD start and how long does it last?

In most cases, post-traumatic stress manifests itself approximately three months after the traumatic event. In some cases, signs Post-traumatic stress symptoms only show up years later. Post-traumatic Stress affects people of all ages. Even children are not immune from it.

In some cases, signs Post-traumatic stress symptoms only show up years later. Post-traumatic Stress affects people of all ages. Even children are not immune from it.

Some get better after six months, others may suffer from it illness for much longer.

Am I the only one with this condition?

No, you are not alone. Every year, 5.2 million Americans suffer from PTSD.

Women suffer from this disease two and a half times more often than men. The most common traumatic events that cause PTSD in men are: rape, participation in hostilities, abandonment and abuse in childhood. The most traumatic events in women are rape, sexual molestation, physical assault, threat weapons and childhood abuse.

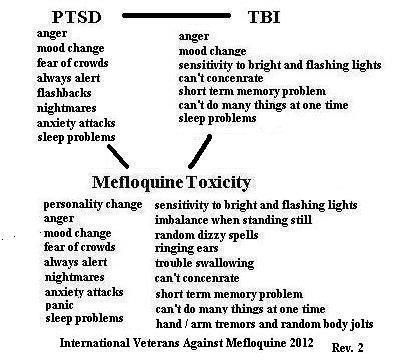

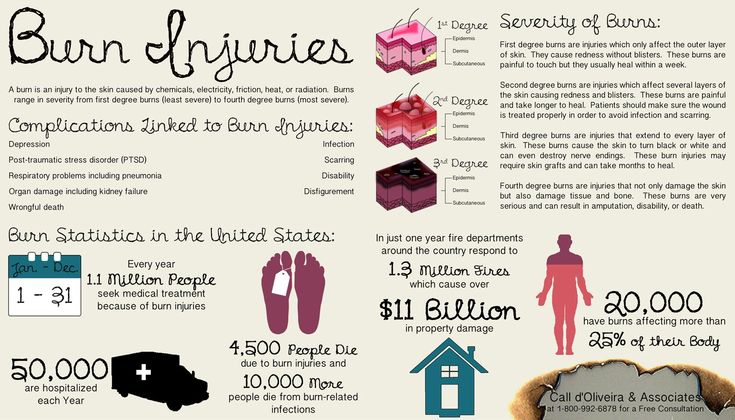

What other conditions can accompany PTSD?

Common depression, alcoholism and drug addiction, or other anxiety disorders. The likelihood of successful treatment increases if these comorbidities to identify and treat in time.

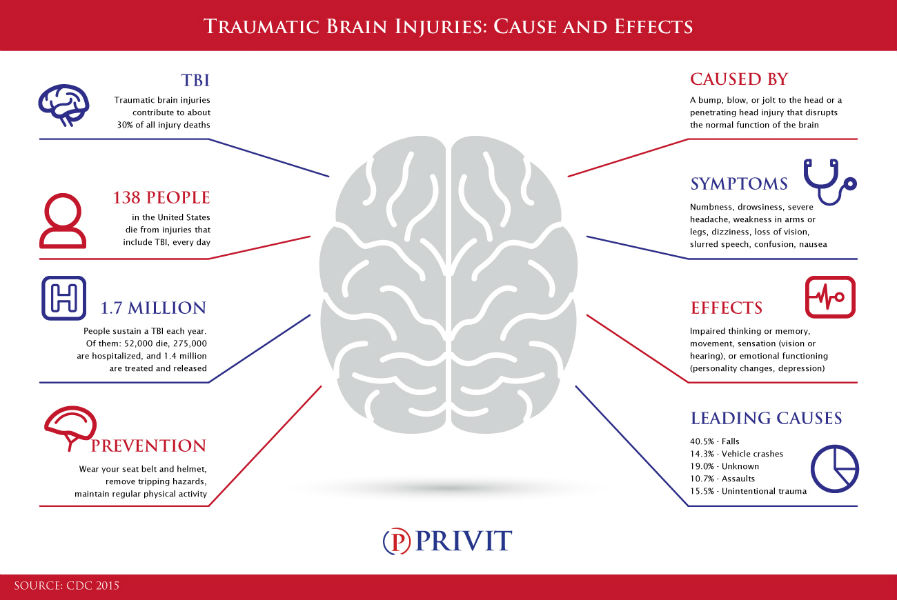

Frequent headaches, gastroenterological problems, problems with the immune system, dizziness, chest pain or discomfort in other parts of the body. It often happens that a doctor treats physical symptoms, unaware that their cause lies in PTSD.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) recommends therapists to learn from patients about experiences of violence, recent losses and traumatic events, especially when symptoms persist are returning. After diagnosing PTSD, it is recommended to refer patient to a mental health specialist who has experience in the treatment of patients with PTSD.

What should I do to help myself in this situation?

Talk to your doctor and tell him about your experience, and how you feel. If you are visited by terrible memories, overcomes depression and sadness if you have trouble sleeping and constantly embittered - you should tell your doctor about all this. Tell him Are any of these conditions preventing you from doing your daily activities? lead a normal life. You may want to show this booklet to your doctor. This may help explain to him how you feel. Ask your doctor examine you to make sure there are no physical illnesses.

You may want to show this booklet to your doctor. This may help explain to him how you feel. Ask your doctor examine you to make sure there are no physical illnesses.

Ask your doctor if he has had patients with post-traumatic stress. If your doctor does not have a special preparation, ask him for directions to doctor with relevant experience.

How can a doctor or psychotherapist help me?

Your doctor may prescribe medicine to help reduce your fear or tension. However, it should be borne in mind that usually several weeks before the medicine starts to work.

Many PTSD sufferers benefit from talking with a professional or other people who have experienced traumatic events. This is called "therapy". Therapy will help you get over your nightmare.

One man's story:

"After I was attacked, I He constantly felt fear and depression, became irritable. I couldn't sleep well and lost my appetite. Even when I tried not think about what happened, I was still tormented nightmares and terrible memories.

Even when I tried not think about what happened, I was still tormented nightmares and terrible memories.

“I was completely at a loss and didn't know what to do. one buddy advised to see a doctor. My doctor helped me find a specialist in post-traumatic stress."

“I needed a lot of strength, but after medication and a course of therapy, I gradually come to my senses. It’s good that I called my doctor then.”

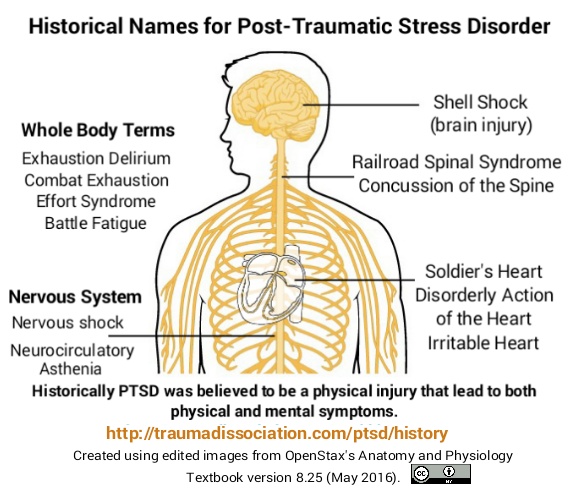

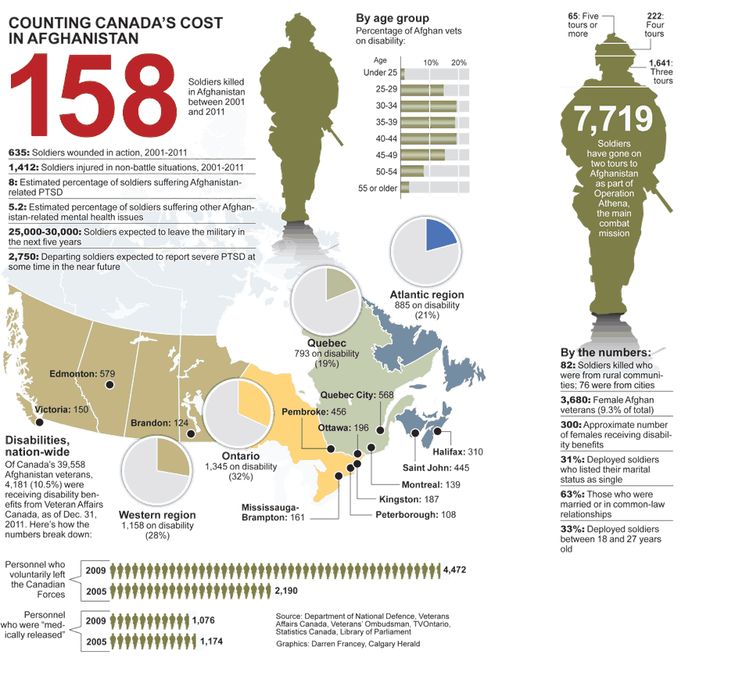

PTSD and the military

If you are in the military, you have probably been in combat. You, probably got into terrible and life-threatening situations. They shot at you you have seen your friend shot, you have seen death. experienced you events can cause PTSD.

Experts say that PTSD occurs:

- Nearly 30% of Vietnam War veterans

- Nearly 10% of Gulf War veterans (Operation Desert Storm)

- Almost 25% of veterans of the war in Afghanistan (operations "Introducing freedom") and veterans of the war in Iraq (operations "Iraqi Freedom")

Other factors of the military situation can serve as an additional stress to and so stressful situation and can contribute to the development of PTSD and other mental problems. Among these factors are the following: your military specialty, the political aspects of the war, where the battle takes place and who your enemy is.

Among these factors are the following: your military specialty, the political aspects of the war, where the battle takes place and who your enemy is.

Another reason that contributes to PTSD in military personnel can be Military Sexual Assault (MST) – any form of sexual harassment or sexual abuse while serving in the military. MST can happen with men and women, and can occur in peacetime, during war training or during the war.

Veterans Affairs (VA) health care approximately:

- 23 out of 100 women (23%) report sexual violence during military service

- 55 out of 100 women (55%) and 38 out of 100 men (38%) were exposed to sexual harassment while serving in the army

Although the trauma of sexual assault is more common in the military among women, more than half of veterans who have experienced sexual trauma violence in the army - it's men.

Remember, you can get the help you need right now:

Tell your doctor about your experience and how you feel. If your doctor does not have special training in the treatment of PTSD, ask him for a referral to a doctor who has relevant experience.

If your doctor does not have special training in the treatment of PTSD, ask him for a referral to a doctor who has relevant experience.

PTSD research

To help those suffering from PTSD, the National Institute of Conservation Mental Health (NIMH) supports research into the study of PTSD, as well as other thematically related to PTSD research on problems anxiety and fear. The challenge for research is to find new ways to help people cope with trauma, as well as find new treatment options and, The main thing is to prevent disease.

Research on possible risk factors for PTSD

Today, the attention of many scientists is focused on genes that play a role in having terrible memories. Understanding the mechanism of "creation" of scary memories can help improve or find new ways to alleviate symptoms of PTSD. For example, PTSD researchers have identified genes that are responsible for:

Statmin is a protein involved in the formation of terrible memories. During one experiment, mice were placed in environment designed to instill fear in them. In this situation mice lacking the statmin gene, in contrast to normal mice were less likely to "freeze" - i.e. exercise natural defensive response to danger. Also in the environment designed to evoke innate fear in them, they demonstrated it to a lesser extent than normal mice, more willingly mastering the open "dangerous" space. 1

During one experiment, mice were placed in environment designed to instill fear in them. In this situation mice lacking the statmin gene, in contrast to normal mice were less likely to "freeze" - i.e. exercise natural defensive response to danger. Also in the environment designed to evoke innate fear in them, they demonstrated it to a lesser extent than normal mice, more willingly mastering the open "dangerous" space. 1

GRP (gastrin-releasing peptide/GRP) - signal substance brain released during emotional events. At in mice, GWP helps control the fear response, and lack of GWP can lead to a longer memory of fear. 2

Scientists have also discovered a variant of the 5-HTTLPR gene that controls serotonin (a brain substance associated with mood), which, as it turns out, feeds the fear response. 3 It seems that, like in the case of other mental disorders, in the development of PTSD different genes are involved, each of which contributes to the formation of the disease.

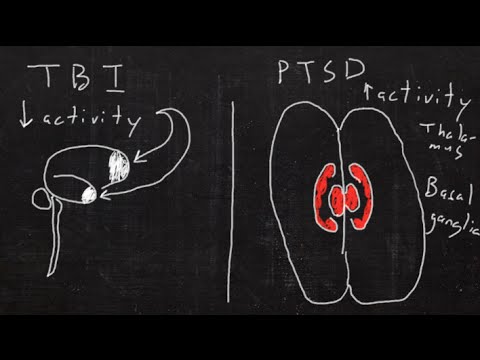

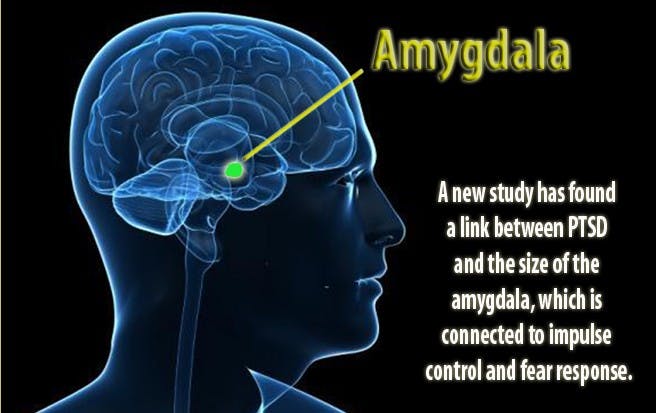

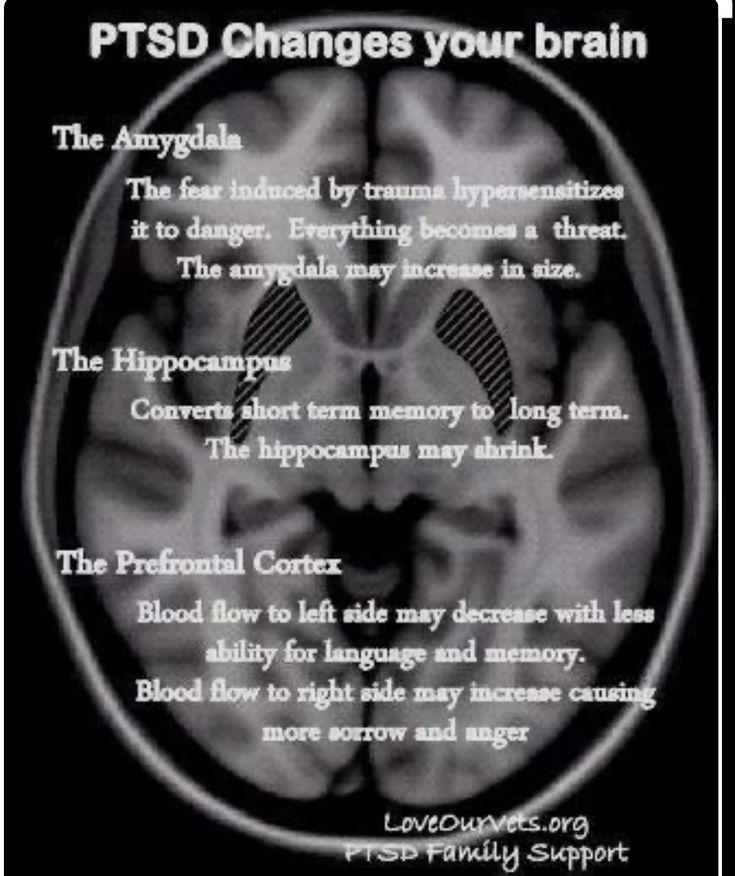

Understanding the causes of PTSD can also be helped by studying different areas brain responsible for fear and stress. One of these areas is cerebellar amygdala, responsible for emotions, learning and memory. It turned out that she plays an active role in the emergence of fear (or other words, "teaches" to be afraid of something, for example, to touch a hot stove), as well as in the early phases of fear repayment (or in other words, "teaches" Do not be scared). 4

The retention of faded memories and the weakening of the initial fear reaction are associated with the prefrontal cortex (PFC / PFC) of the brain, 4 responsible for decision making, problem solving and situation assessment. Each zone PFC has its own role. For example, when the PFC believes that a stressor is amenable to control, the medial prefrontal zone of the PFC suppresses the anxiety center deeply in the brainstem and controls the response to stress. 5 Ventromedial PFC helps maintain long-term fading of fearful memories, and her ability to perform this feature can be affected by its size. 6

5 Ventromedial PFC helps maintain long-term fading of fearful memories, and her ability to perform this feature can be affected by its size. 6

Individual differences in genes or characteristics of regions of the brain brain can only set the stage for PTSD, but by themselves do not cause no symptoms. environmental factors such as childhood trauma, head trauma or mental illness in family, favor the development of the disease and increase the risk of disease, affecting the brain in the early stages of its growth. 7 Except In addition, how people adapt to trauma is likely to be influenced by and characteristics of character and behavior, such as optimism and a tendency to consider problems in a positive or negative way, as well as social factors such as availability and use of social support. 8 Further research may show what combination of these factors or what other factors will allow ever predict who has a traumatic event cause PTSD, and who doesn't.

PTSD research

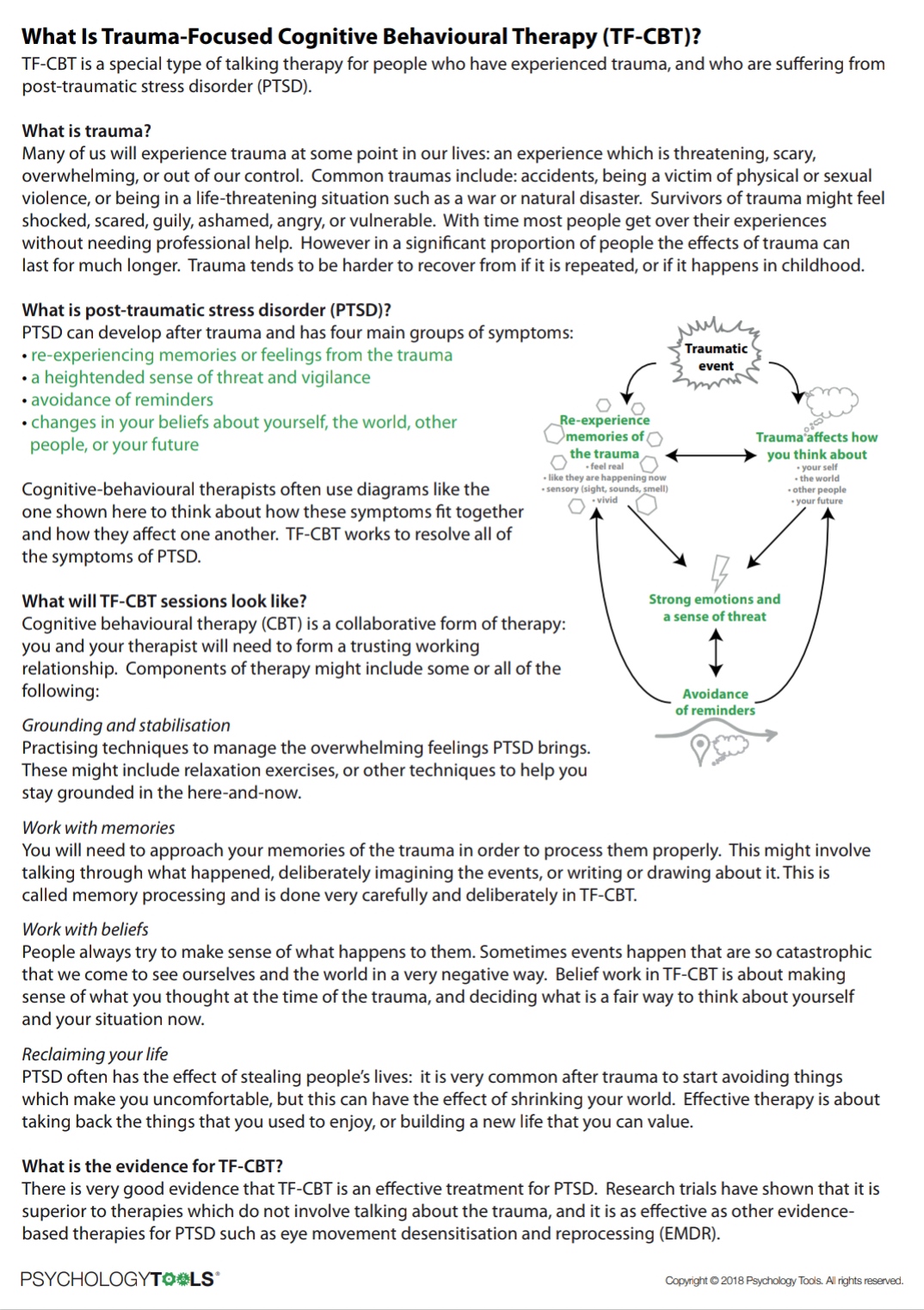

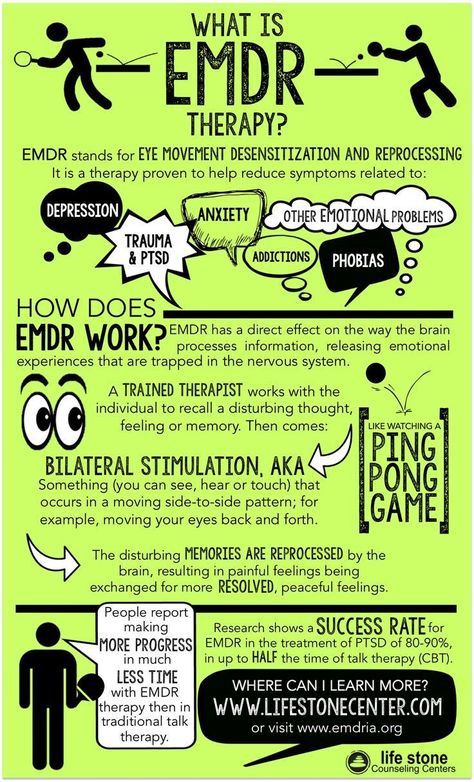

Currently, psychotherapy is used in the treatment of PTSD ("talk" therapy), drugs or drug-therapeutic combination.

Psychotherapy

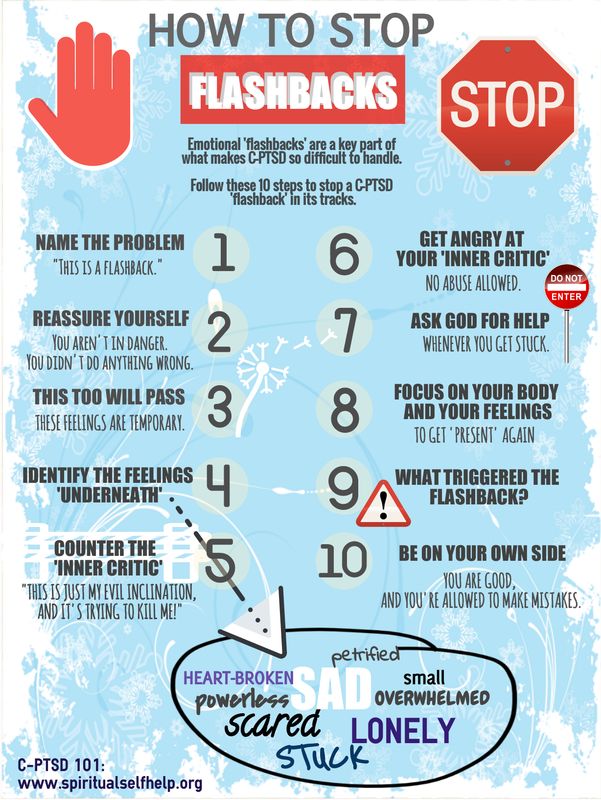

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) helps you learn differently think and react to frightening events that are the impetus for development PTSD, and can help bring the symptoms of the disease under control. There are several types cognitive behavioral therapy, including:

"Push" method - uses mental images, notes or visiting a place experienced trauma to help those affected face the overwhelming their fear and take control of it.

Behavior restructuring (cognitive restructuring) - encourages survivors of a traumatic event express depressing (often erroneous) thoughts about experienced trauma, challenge these thoughts and replace them with more balanced and appropriate.

Implementation in a stressful situation - teaches ways to reduce anxiety and the ability to cope with it, helping to reduce the symptoms of PTSD, and helps to correct the erroneous train of thought associated with the trauma experienced. NIMH is currently conducting research to study the reaction brain response to cognitive behavioral therapy versus response sertraline (Zoloft) - one of two drugs recommended and approved US Food and Drug Administration funds (FDA) for the treatment of post-traumatic stress. This research may help find out why some people respond better to medications, and others for psychotherapy

NIMH is currently conducting research to study the reaction brain response to cognitive behavioral therapy versus response sertraline (Zoloft) - one of two drugs recommended and approved US Food and Drug Administration funds (FDA) for the treatment of post-traumatic stress. This research may help find out why some people respond better to medications, and others for psychotherapy

Drugs

Recently, in a small study, NIMH scientists found that if patients who are already taking a dose of prazosin (Minipress) at bedtime, add a daily dose, then this weakens the general symptoms of PTSD and stress reaction to reminders of the trauma experienced. 9

Another drug of interest is D-cycloserine (Seromycin), which increases the activity of a brain substance called N-methyl-D-aspartate, needed to pay off fear. During the study, which was attended by 28 people suffering from a fear of heights, scientists found that patients who received "push" therapy before a session D-cycloserine, showed lower levels of fear during the session compared to those who did not receive the drug. 10 Currently scientists study the effectiveness of the combined use of D-cycloserine and therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress.

10 Currently scientists study the effectiveness of the combined use of D-cycloserine and therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress.

Propranolol (Inderal), a beta-blocker drug, also under study whether it can be used to reduce post-traumatic stress and break the chain of scary memories. First experiments gave consoling results: it was possible to successfully weaken and, it seems, prevent PTSD in a small number of victims of traumatic events. 11

For example, in one preliminary study, scientists created a website self-help, based on the use of a psychotherapeutic method implementation in a stressful situation. First, patients with PTSD meet in person with doctor. After this meeting, participants can go to the site to find more information about PTSD and how to deal with the problem; their doctors may also visit the site to give advice or briefing. In general, scientists believe that therapy in this form - promising treatment for a large number of people suffering from PTSD. 12

12

Scientists are also working to improve methods for testing early treatment and monitoring of survivors of massive trauma, on developing ways to teach them self-assessment skills and introspection and referral mechanism to psychiatrists (if necessary).

Prospects for PTSD research

In the last decade, rapid progress in the study of mental and biological PTSD has led scientists to conclude that there is a need to focus on prevention, as the most realistic and important goal.

For example, in order to find ways to prevent PTSD, with funding NIMH conducts research to develop new and orphan drugs, aimed at combating the underlying causes of the disease. During another research scientists are looking for ways to enhance behavioral, personality and social protective factors and minimizing risk factors for prevent the development of PTSD after trauma. Another study is studying the question of what factors influence the difference in response to one or another method of treatment, which will help in the development of more individual, effective and productive methods of treatment.

Where can I find more information?

MedlinePlus - resource from the American National Library of Medicine (U.S. National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health) - offers the latest information on many health issues. Information about You can find PTSD at: www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/posttraumaticstressdisorder.html.

National Institute of Mental Health

Office of Science Policy, Planning, and Communications

[National Institute of Mental Health

Science Policy Division research, planning and communications]

6001 Executive Boulevard

Room 8184, MSC 9663

Bethesda, MD 20892-9663

Phone: 301-443-4513; Fax: 301-443-4279

fax answering system Free answering machine: 1-866-615-NIMH (6464)

Text phone: 1-866-415-8051 toll-free

Email: [email protected]

National Center for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

[National PTSD Center]

VA Medical Center (116D)

215 North Main Street

White River Junction, VT 05009

802-296-6300

www. ncptsd.va.gov

ncptsd.va.gov

NOTES

- Shumyatsky GP, Malleret G, Shin RM, et al. Stathmin, a Gene Enriched in the Amygdala, Controls Both Learned and Innate Fear. cell. Nov 18 2005;123(4):697-709.

- Shumyatsky GP, Tsvetkov E, Malleret G, et al. Identification of a signal network in lateral nucleus of amygdala important for inhibiting memory specifically related to learned fear. cell. Dec 13 2002;111(6):905-918.

- Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, et al. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala.Science. Jul 192002;297(5580):400-403.

- Milad MR, Quirk GJ. Neurons in medial prefrontal cortex signal memory for fear extinction. Nature. Nov 7 2002;420(6911):70-74.

- 5 Amat J, Baratta MV, Paul E, Bland ST, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Medial prefrontal cortex determines how stressor controllability affects behavior and dorsal raphe nucleus.

Nat Neurosci. Mar 2005;8(3):365-371.

Nat Neurosci. Mar 2005;8(3):365-371. - Milad MR, Quinn BT, Pitman RK, Orr SP, Fischl B, Rauch SL. Thickness of ventromedial prefrontal cortex in humans is correlated with extinction memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. Jul 26 2005;102(30):10706-10711.

- Gurvits TV, Gilbertson MW, Lasko NB, et al. Neurological soft signs in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder.Arch Gen Psychiatry. Feb 2000;57(2):181-186.

- Brewin CR. Risk factor effect sizes in PTSD: what this means for intervention. J Trauma Dissociation. 2005;6(2):123-130.

- Taylor FB, Lowe K, Thompson C, et al. Daytime Prazosin Reduces Psychological Distress toTrauma Specific Cues in Civilian Trauma Posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. Feb 3 2006.

- Ressler KJ, Rothbaum BO, Tannenbaum L, et al. Cognitive enhancers as adjuncts to psychotherapy: use of D-cycloserine in phobic individuals to facilitate extinction of fear.

Arch Gen Psychiatry. Nov 2004;61(11):1136-1144.

Arch Gen Psychiatry. Nov 2004;61(11):1136-1144. - Pitman RK, Sanders KM, Zusman RM, et al. Pilot study of secondary prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder with propranolol.Biol Psychiatry. Jan 15 2002;51(2):189-192.

- Litz BTWL, Wang J, Bryant R, Engel CC.A therapist-assisted Internet self-help program for traumatic stress. Prof Psychol Res Pr. December 2004;35(6):628-634.

New York State Department of Mental Health expresses thanks to the National Institute of Mental Health for the information, used in this booklet.

Published by the State Department of Mental Health New York, June 2008.

New York State

Andrew M. Cuomo Governor

Mental Health

Head of Department Michael F. Hogan, PhD

For more information about this edition contact:

New York State Office of Mental Health

Community Outreach and Public Education Office

[New York State Division of Mental Health

Public Relations and Community Education Department]

44 Holland Avenue

Albany, NY 12229

866-270-9857 (toll free)

www. omh.ny.gov

omh.ny.gov

For questions and complaints about mental health services Health in New York contact:

New York State Office of Mental Health

Customer Relations

[New York State Division of Mental Health

Customer Service ]

44 Holland Avenue

Albany, NY 12229

800-597-8481 (toll-free)

For information about mental health services in your neighborhood, contact

nearest New York State Department of Mental Health (NYSOMH) regional office:

Western New York Field Office

[Western New York Regional Office]

737 Delaware Avenue, Suite 200

Buffalo, NY 14209

(716) 885-4219

Central New York Field Office

[Central New York Regional Office]

545 Cedar Street, 2nd Floor

Syracuse, NY 13210-2319

(315) 426-3930

Hudson River Field Office

[Hudson River Regional Office]

4 Jefferson Plaza, 3rd Floor

Poughkeepsie, NY 12601

(845) 454-8229

Long Island Field Office

[Long Island Regional Office]

998 Crooked Hill Road, Building #45-3

West Brentwood, NY 11717-1087

(631) 761-2508

New York City Field Office

[NYC Regional Office]

330 Fifth Avenue, 9th Floor

New York, NY 10001-3101

(212) 330-1671

PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a disease that develops in a person after a traumatic event.

The most common cause of PTSD is the unforeseen death of a loved one,1 but other causes may include sexual abuse, war, physical assault, natural disasters, or car accidents. 2 PTSD can develop as a result of a traumatic event experienced by the patient himself, or an event that he witnessed, or an event that happened to a close friend or relative. 2

PTSD is a serious and often untreated condition that can develop at any age and negatively impact many social and economic aspects of life. 2-4

Facts about PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops when a person has been exposed to, witnessed a traumatic event, or learned of the involvement of a loved one. Traumatic events can be the death of a loved one, sexual abuse, war, physical assault, natural disaster, or car accident .1

Patients with PTSD may suffer from haunting memories and flashbacks, self-blame, inability to experience happiness, negative emotions (irritability, recklessness) and

may actively avoid memories of the traumatic event . 1

1

: 5

Re-experiencing trauma - recurring memories, nightmares, flashbacks.

Avoidance symptoms avoidance of thoughts, feelings, objects, people and places associated with the traumatic event.

Negative thoughts and emotions Exaggerated negative beliefs about being alone in the world, shame or guilt, reduced emotional background, feelings of alienation and difficulty

reproducing the details of the traumatic event.

Changes in emotional response - irritability, being in a state of "alertness", unsafe behavior, sleep disturbances and difficulty concentrating.

Symptoms of PTSD vary from patient to patient. Some experience predominantly one of the four types of symptoms, while others show a combination of symptoms. 2 The timing of symptom development also varies - in most patients symptoms develop immediately after the traumatic event, 3 in others the onset of symptoms may be delayed by months or even years. 2

2

70%

·

people in the world go through the experience of a traumatic event during their lifetime, but most recover normally. 4.5

~ 3.9%

of the world's population suffer from PTSD; among those who have experienced a traumatic event, the frequency is 5.6% .5

Most people in the world (70%) go through traumatic events throughout their lives. 6 While most trauma survivors recover normally, 5.6% develop PTSD. 3 In other words, 3.9% of the population suffers from PTSD .3 The disorder occurs more than twice as often in women as in men, and more frequently in high-income countries than in low-income countries. 3

The incidence of PTSD is higher in veterans and those in high-risk jobs (eg, police, firefighters, and emergency medical personnel). 2

2

Some patients with PTSD recover quickly, while others have symptoms for years. 2

PTSD can have a negative impact on many aspects of life, including intimate relationships, friendships, social life, parenting, finances, work and school. 4

A global study by the World Health Organization (WHO) found that patients with PTSD missed an average of 15 more work days per year compared to people without

PTSD .7 which can lead to significant costs. In older patients, PTSD symptoms can lead to poor health, cognitive decline, and social isolation, all of which create an additional burden of disease. 2

Facts about Post-traumatic stress disorder

PTSD can occur at any age, even in very young children. 1

PTSD can have a negative effect on intimate relationships, friendships and socializing, parenting, work and academic performance, and finances. 2

2

People who are concerned that they – or their loved ones – are experiencing symptoms of PTSD should see their doctor for help and advice.

People who suspect symptoms of PTSD in themselves or a loved one should seek medical advice and assistance. The diagnosis of PTSD is made on the basis of

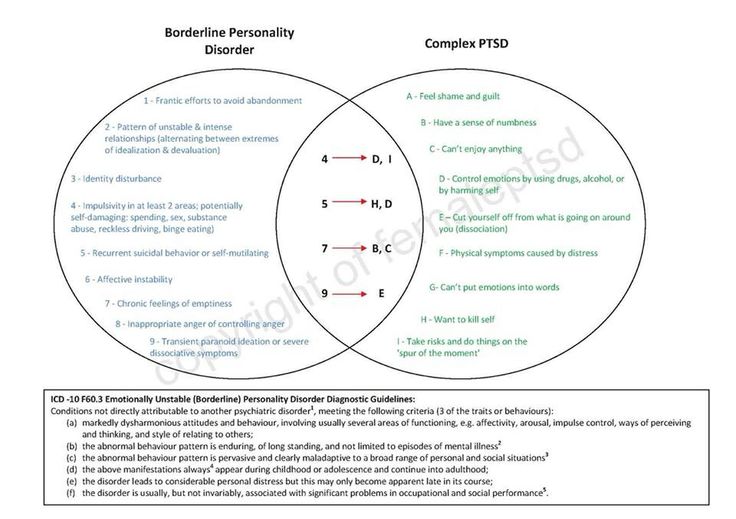

conversations with the patient or with parents if the patient is a small child. 2 Often the symptoms of PTSD are similar to those of other diseases (eg depression), which can lead to misdiagnosis. 8 The main difference between PTSD and depression is the association with the traumatic event.

Treatment for PTSD typically includes psychotherapy—professional emotional and behavioral support—and medication. 9 Despite this, data from a global study suggests that less than 50% of PTSD sufferers seek medical attention. 3 However, late initiation of treatment may lead to worse prognosis. 10 Early diagnosis and treatment are essential

10 Early diagnosis and treatment are essential

for PTSD patients.

- Kessler RC, Rose S, Koenen KC, Karam EG, Stang PE, Stein DJ, et al. How well can post-traumatic stress disorder be predicted from pre-trauma risk factors? An exploratory study in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):265–274.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5 th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Koenen KC, Ratanatharathorn A, Ng L, McLaughlin KA, Bromet EJ, Stein DJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol Med. 2017;47(13):2260–2274.

- Rodriguez P, Holowka DW, Marx BP. Assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder-related functional impairment: a review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(5):649–665.

- Lancaster CL, Teeters JB, Gros DF, Back SE. Posttraumatic stress disorder: an overview of evidence-based assessment and treatment.

J Clinic Med. 2016;5(11).pii:E105.

J Clinic Med. 2016;5(11).pii:E105. - Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam EG, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Ruscio AM, et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychol Med. 2016;46(2):327–343.

- Alonso J, Petukhova M, Vilagut G, Chatterji S, Heeringa S, Üstün TB, et al. Days out of role due to common physical and mental conditions: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(12):1234–1246.

- Brady KT, Killeen TK, Brewerton T, Lucerini S. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(Suppl 7):22–32.

- American Psychological Association. Guideline Development Panel for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in adults. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of PTSD. American Psychological Association; 2017.

- Maguen S, Madden E, Neylan TC, Cohen BE, Bertenthal D, Seal KH. Timing of mental health treatment and PTSD symptom improvement among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.

Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(12):1414–1419.

Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(12):1414–1419.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5 th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Rodriguez P, Holowka DW, Marx BP. Assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder-related functional impairment: a review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(5):649–665.

- Alonso J, Petukhova M, Vilagut G, Chatterji S, Heeringa S, Üstün TB, et al. Days out of role due to common physical and mental conditions: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(12):1234–1246.

- Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam EG, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Ruscio AM, et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychol Med. 2016;46(2):327–343.

- Koenen KC, Ratanatharathorn A, Ng L, McLaughlin KA, Bromet EJ, Stein DJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys.