Can depression cause schizophrenia

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

HomeWelcome to the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator, a confidential and anonymous source of information for persons seeking treatment facilities in the United States or U.S. Territories for substance use/addiction and/or mental health problems.

PLEASE NOTE: Your personal information and the search criteria you enter into the Locator is secure and anonymous. SAMHSA does not collect or maintain any information you provide.

Please enter a valid location.

please type your address

-

FindTreatment.

gov

gov Millions of Americans have a substance use disorder. Find a treatment facility near you.

-

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

Call or text 988

Free and confidential support for people in distress, 24/7.

-

National Helpline

1-800-662-HELP (4357)

Treatment referral and information, 24/7.

-

Disaster Distress Helpline

1-800-985-5990

Immediate crisis counseling related to disasters, 24/7.

- Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Finding Treatment

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Facility Directors

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Other Locator Functionalities

- Download Search ResultsDownload Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Print Search ResultsPrint Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). - Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). Find programs providing methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

The Locator is authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act (Public Law 114-255, Section 9006; 42 U.S.C. 290bb-36d). SAMHSA endeavors to keep the Locator current. All information in the Locator is updated annually from facility responses to SAMHSA’s National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N-SUMHSS). New facilities that have completed an abbreviated survey and met all the qualifications are added monthly. Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

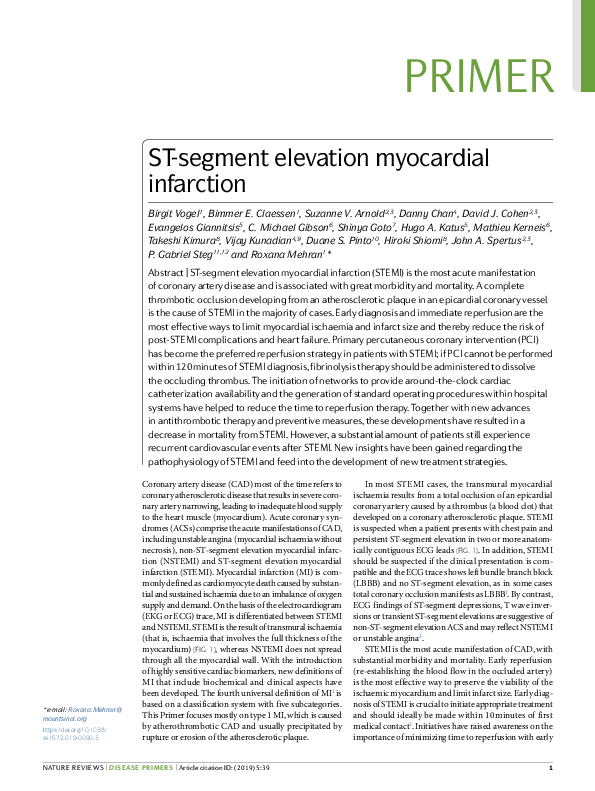

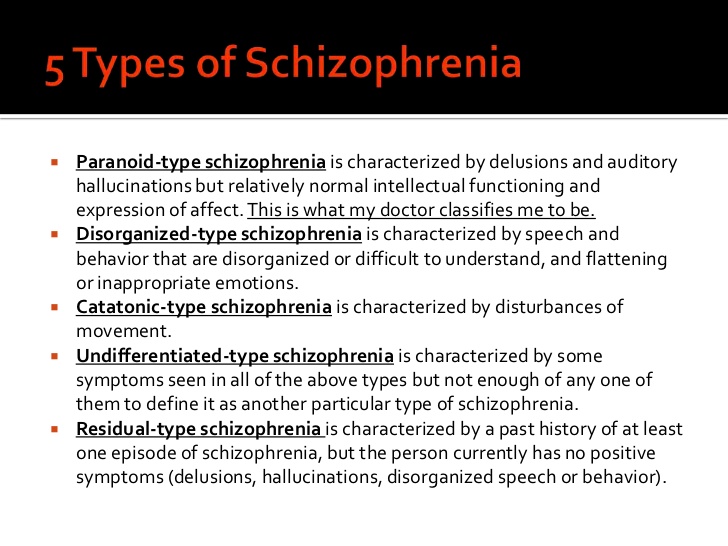

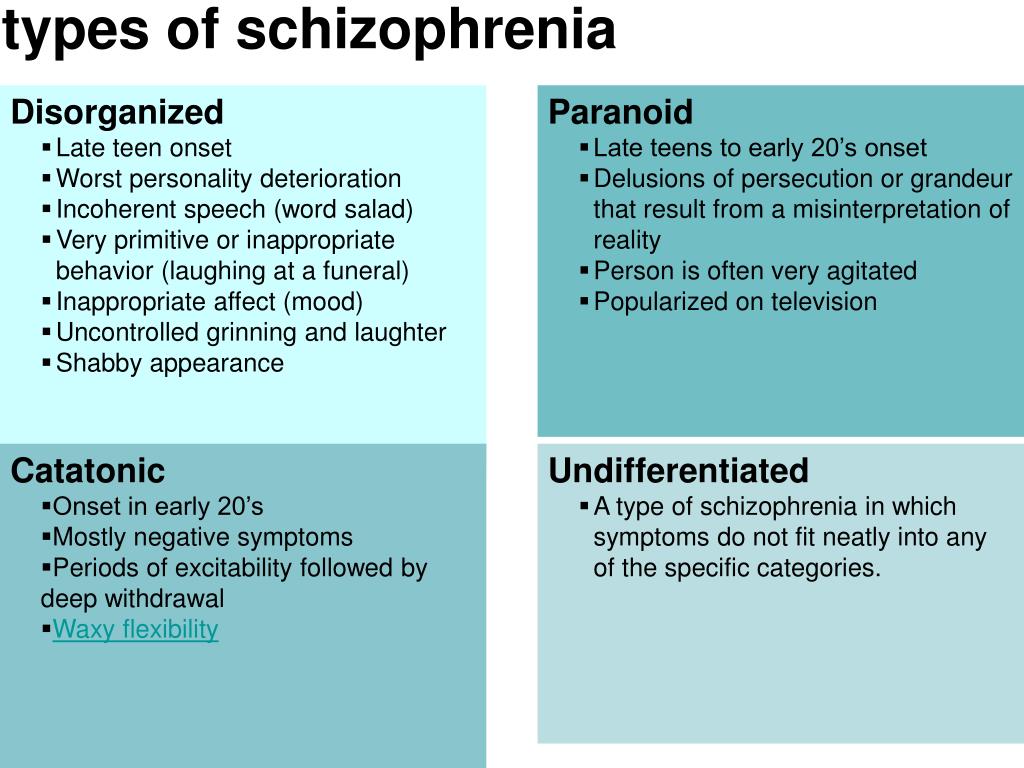

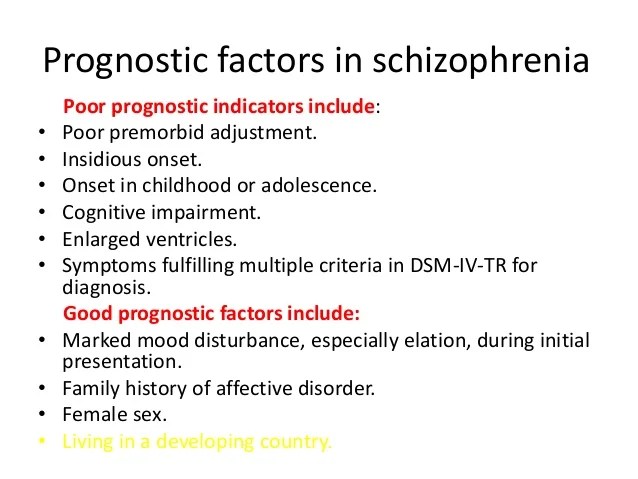

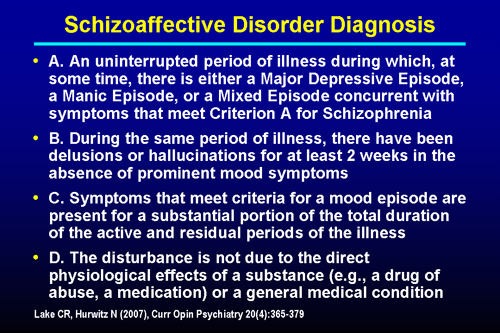

Depression in schizophrenia: diagnosis and therapy

Despite the large number of scientific publications on depression in schizophrenia, the main provisions concerning this problem remain debatable today. Perhaps the only issue on which a certain consensus has been reached is that depression is an integral part of schizophrenia and it can develop in any form and at any stage of the course of the disease [20]. Although there are indications of a “mitigating” effect of depression on the manifestations of schizophrenia [2, 26], most researchers consider the presence of depression as an unfavorable prognostic factor that reduces the quality of life of patients, aggravates their psychosocial functioning disorders and increases the risk of suicide [28].

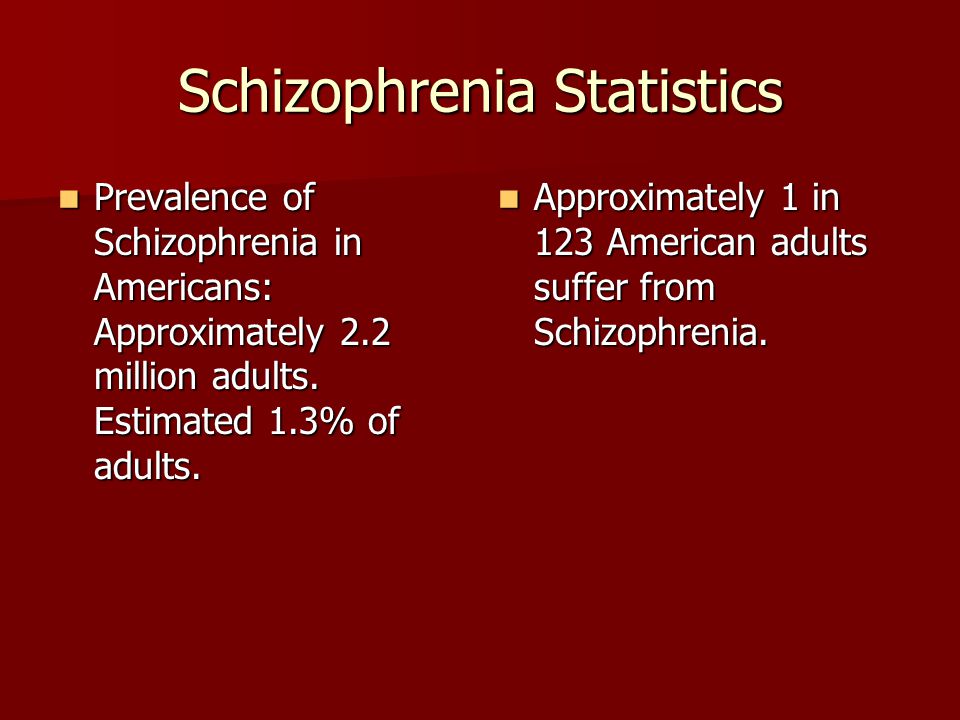

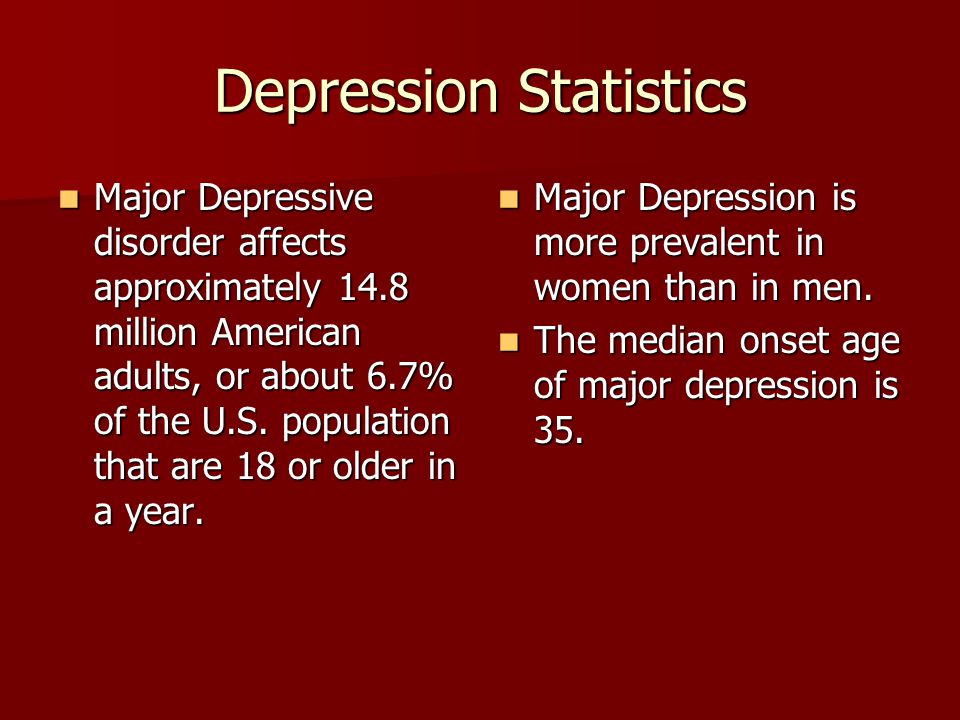

The incidence of depressive symptoms in schizophrenia ranges from 7 to 70% [31]. Such a wide range of indicators may be due to the examination of patients at different stages of the disease, as well as the lack of generally accepted methodological approaches not only to assessing individual depressive symptoms, but also the full-blown depressive syndrome. The results of a study by J. Sands and M. Harrow [29], who observed 70 patients with schizophrenia for 7.5 years, showed that in 24% of cases there were no depressive symptoms, 26% had individual depressive symptoms, and 14% had subsyndromal depression. and 36% had depression meeting clinical criteria for major depressive disorder [29].

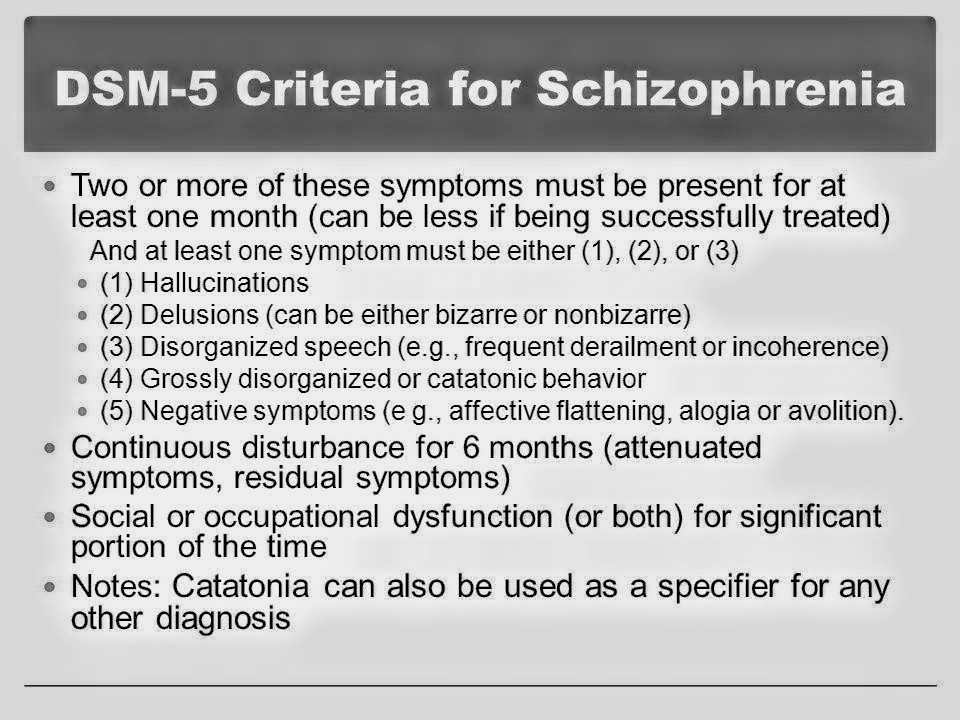

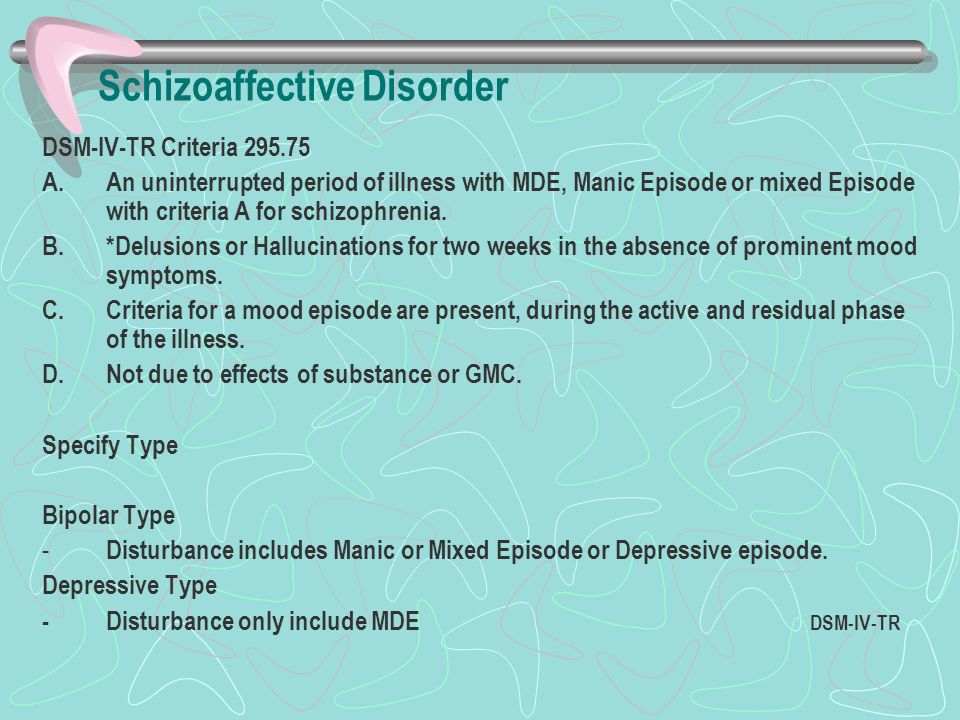

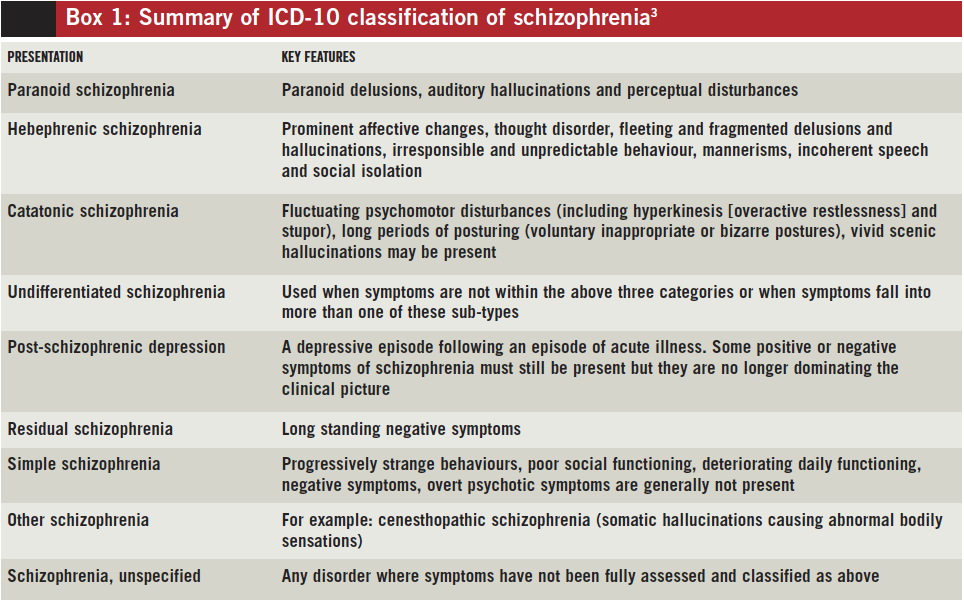

Modern classifications of ICD-10 and DSM-IV when registering depression in patients with schizophrenia (in particular, post-seizure depression) suggest using the same diagnostic landmarks as for a depressive episode within an affective disorder. This approach significantly reduces the detection of depressive disorders in patients with schizophrenia. Probably, it is necessary to develop guidelines that would reflect the phenomenological specificity of depression in schizophrenia to a greater extent.

Probably, it is necessary to develop guidelines that would reflect the phenomenological specificity of depression in schizophrenia to a greater extent.

There are different concepts in the literature regarding the development of depression in schizophrenia.

According to the personality-reactive hypotheses, the formation of depression is mainly associated with the psychological reaction of the individual to the fact of the existence of a mental disorder and the social maladaptation caused by it [18]. However, within the framework of these hypotheses, there is another view: it is the presence of depression in patients with schizophrenia that causes psychological discomfort and contributes to the growth of social decompensation [33].

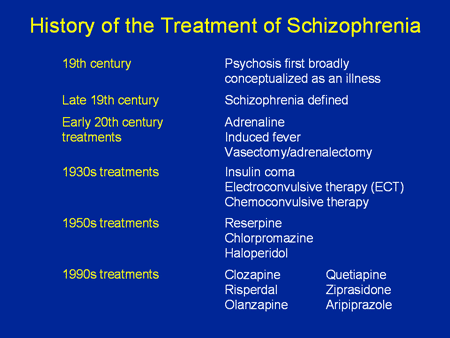

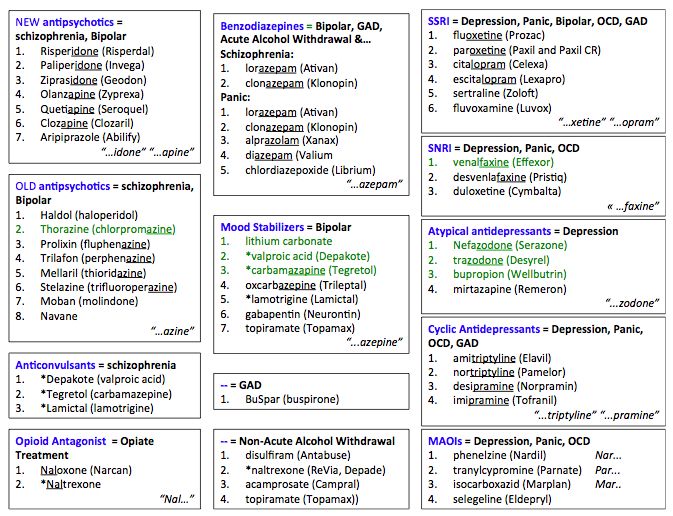

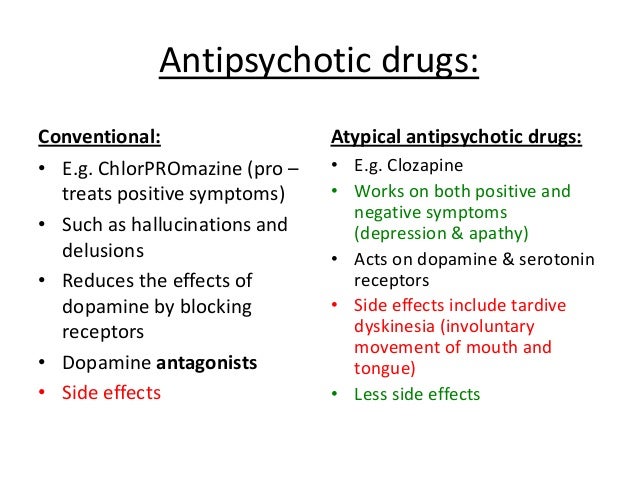

The pharmacogenic concept emphasizes the role of antipsychotic therapy in the formation of depression. In the literature [16, 36], the hypothesis of pseudoparkinsonian depression is widely discussed, suggesting its connection with extrapyramidal syndrome (EPS). At the same time, they do not exclude [19] the direct effect of antipsychotic drugs on dopamine transmission. The antidopamine activity of antipsychotics leads to the development of not only EPS, but also hyperprolactinemia. The latter attracts attention due to the fact that there are data in the literature [3, 8, 22, 34] on the development of affective disorders with elevated prolactin levels both in patients with endocrine disorders and in mentally ill patients. However, in our opinion, in this case, the fact that an increase in prolactin may be related to thyroid hormones, which play a significant role in the development of affective pathology, is also underestimated. It can be added to the above that when using atypical antipsychotics, which significantly less contribute to the development of neurological side effects, depressive symptoms develop during therapy in 10-13% of cases [4, 5]. Therefore, ideas about the relationship of depression with antipsychotic therapy require further development.

At the same time, they do not exclude [19] the direct effect of antipsychotic drugs on dopamine transmission. The antidopamine activity of antipsychotics leads to the development of not only EPS, but also hyperprolactinemia. The latter attracts attention due to the fact that there are data in the literature [3, 8, 22, 34] on the development of affective disorders with elevated prolactin levels both in patients with endocrine disorders and in mentally ill patients. However, in our opinion, in this case, the fact that an increase in prolactin may be related to thyroid hormones, which play a significant role in the development of affective pathology, is also underestimated. It can be added to the above that when using atypical antipsychotics, which significantly less contribute to the development of neurological side effects, depressive symptoms develop during therapy in 10-13% of cases [4, 5]. Therefore, ideas about the relationship of depression with antipsychotic therapy require further development.

There is also a hypothesis that depression is an integral, core component of schizophrenia (at least one of the variants of this disease), along with negative and positive symptom complexes [5, 20]. This point of view is supported by data on the existence of depressive vulnerability in a number of patients with schizophrenia [5].

Among other things, in patients with schizophrenia, depression can be caused by a somatic disease, taking certain drugs (β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, hypnotics, indomethacin, corticosteroids), drug and drug dependence, alcoholism.

Thus, one can speak of primary depression in schizophrenia and secondary, or symptomatic, depressive states. In clinical practice, there are, apparently, depressive states, in the formation of which several (more than one) factors take part. And if a number of secondary depressions can be diagnosed in a timely manner, then in some cases it is sometimes difficult to determine the role of one or another mechanism in the formation of primary depression1. It is all the more difficult to objectively assess the contribution to the formation of depression of reactive mechanisms, which are most often present in varying degrees in patients with a chronic disease.

It is all the more difficult to objectively assess the contribution to the formation of depression of reactive mechanisms, which are most often present in varying degrees in patients with a chronic disease.

Diagnostic uncertainty entails therapeutic uncertainty in relation to approaches to the treatment of patients with depression in the structure of a schizophrenic attack. The most controversial issue concerns the advisability of using antidepressants in this category of patients. The main concerns are related to the risk of exacerbation of psychotic symptoms when prescribing antidepressants, as well as the possible increase in side effects due to drug interactions. So, there is data [9], that with the simultaneous appointment of antipsychotics and antidepressants in ¼ of cases, the latter have to be canceled 1-2 weeks after the start of therapy due to an increase in psychotic symptoms. It should be noted, however, that recommendations for limiting the use of antidepressants in schizophrenia are based on only a few clinical studies that have studied the combined use of conventional antipsychotics and tricyclic antidepressants, i. e. their evidence base is insufficient.

e. their evidence base is insufficient.

These studies are analyzed most fully in one of the meta-reviews [23], which considers the results of 11 placebo-controlled studies. His results have been contradictory. Five studies provided evidence in favor of the combined use of antidepressants with antipsychotics compared with antipsychotics alone, in six others - the opposite results. Additionally, it was noted that in one study the combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic was less effective than monotherapy, and in another study, an exacerbation of psychotic symptoms with an increase in the severity of thinking disorders was noted during treatment with antidepressants. There is also a study [30], which indicates that the addition of imipramine to antipsychotic therapy reduces the severity of depressive symptoms without causing an exacerbation of psychosis and significant side effects.

In recent years, a number of publications have appeared that confirm that the introduction of antidepressants into antipsychotic therapy not only does not cause exacerbation of psychotic manifestations, but, on the contrary, has additional advantages. Thus, in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study [21], data were obtained on an increase in the antipsychotic effect of traditional antipsychotics when mirtazapine was added in cases where there was resistance to therapy. In the available literature, we did not find definite data on the effect of mirtazapine on depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia when combined with antipsychotics, but some studies [11, 32] indicate its effect on cognitive impairment that may be associated with depression.

Thus, in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study [21], data were obtained on an increase in the antipsychotic effect of traditional antipsychotics when mirtazapine was added in cases where there was resistance to therapy. In the available literature, we did not find definite data on the effect of mirtazapine on depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia when combined with antipsychotics, but some studies [11, 32] indicate its effect on cognitive impairment that may be associated with depression.

In accordance with the topic of this review, the effect on depression in schizophrenia of modern antidepressants - selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and norepinephrine, which are known to have a more favorable efficacy and safety profile compared to tricyclic antidepressants, requires special consideration.

Existing concerns about the use of SSRIs in combination with atypical antipsychotics due to pharmacokinetic interactions and the risk of increased side effects seem to us somewhat exaggerated. First, individual SSRIs differ in their ability to inhibit the cytochrome P450 system (fluoxetine, paroxetine are strong inhibitors, fluvoxamine has a less pronounced inhibitory ability, sertraline and citalopram have practically no effect on the microsomal enzyme system) [1]. Secondly, pharmacokinetic studies show that all SSRIs in therapeutic dosages do not cause clinically significant changes in plasma concentrations of antipsychotics and their combined use is acceptable [15, 27]. Moreover, from the standpoint of evidence-based medicine, this combination is one of the methods of choice in the treatment of psychotic and treatment-resistant depression. None of the studies with the combined use of antidepressants and antipsychotics showed a higher incidence of exacerbation of psychotic symptoms, and there is evidence of the effective use of antidepressants of the SSRI group in the treatment of an acute attack of schizophrenia.

First, individual SSRIs differ in their ability to inhibit the cytochrome P450 system (fluoxetine, paroxetine are strong inhibitors, fluvoxamine has a less pronounced inhibitory ability, sertraline and citalopram have practically no effect on the microsomal enzyme system) [1]. Secondly, pharmacokinetic studies show that all SSRIs in therapeutic dosages do not cause clinically significant changes in plasma concentrations of antipsychotics and their combined use is acceptable [15, 27]. Moreover, from the standpoint of evidence-based medicine, this combination is one of the methods of choice in the treatment of psychotic and treatment-resistant depression. None of the studies with the combined use of antidepressants and antipsychotics showed a higher incidence of exacerbation of psychotic symptoms, and there is evidence of the effective use of antidepressants of the SSRI group in the treatment of an acute attack of schizophrenia.

As an example of the above [17], a placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of the combined use of fluvoxamine and olanzapine in the treatment of an acute attack of schizophrenia can be given. The study included 20 patients, the duration of therapy was 6 weeks. It was found that in the group of patients treated with olanzapine and fluvoxamine, there was a more pronounced reduction in the total score on the BPRS scale compared with the group treated with olanzapine and placebo. There were no differences in the incidence of side effects between the groups. This suggests that the combined use of SSRI antidepressants and antipsychotics is acceptable in terms of efficacy and safety.

The study included 20 patients, the duration of therapy was 6 weeks. It was found that in the group of patients treated with olanzapine and fluvoxamine, there was a more pronounced reduction in the total score on the BPRS scale compared with the group treated with olanzapine and placebo. There were no differences in the incidence of side effects between the groups. This suggests that the combined use of SSRI antidepressants and antipsychotics is acceptable in terms of efficacy and safety.

However, most recommendations for the management of patients with schizophrenia, while allowing for the possibility of prescribing antidepressants in the development of depression, note that this approach cannot be considered as the first choice therapy, especially in cases of combination with productive symptoms [14, 25, 35 ], because there is currently no evidence base confirming the expediency of such tactics [24]. A review by The Cochrane Collaboration [37] emphasizes that although the combination of antipsychotics and antidepressants may be effective in the treatment of depressive and negative manifestations of schizophrenia, a small number of studies can neither reliably confirm nor refute this position. Moreover, the published results have significant limitations. First of all, this refers to the assessment of the depressive component. As already mentioned, the diagnostic criteria for depression offered by official classifications are very vague. Many studies use the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) to assess the level of depression, although it has been proven [7] that it has little specificity for detecting and assessing depression in patients with schizophrenia, since its indicators correlate with a negative symptom complex. In addition, attention is not always paid to at what stage of the disease an antidepressant is prescribed. And quite rarely, the psychopathological structure of depression is analyzed in detail, which can significantly affect both the course of the disease and the therapeutic prognosis [5, 10]. Thus, for a more informed decision on the advisability of using antidepressants in this aspect, additional studies, methodically clearly planned on the principles of evidence-based medicine, are needed.

Moreover, the published results have significant limitations. First of all, this refers to the assessment of the depressive component. As already mentioned, the diagnostic criteria for depression offered by official classifications are very vague. Many studies use the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) to assess the level of depression, although it has been proven [7] that it has little specificity for detecting and assessing depression in patients with schizophrenia, since its indicators correlate with a negative symptom complex. In addition, attention is not always paid to at what stage of the disease an antidepressant is prescribed. And quite rarely, the psychopathological structure of depression is analyzed in detail, which can significantly affect both the course of the disease and the therapeutic prognosis [5, 10]. Thus, for a more informed decision on the advisability of using antidepressants in this aspect, additional studies, methodically clearly planned on the principles of evidence-based medicine, are needed.

Of great interest is the point of view of practitioners on the problem under discussion, since the combination of antidepressants and antipsychotics is a fairly common variant of pharmacotherapy in psychiatric practice - in 41.5% of all courses of psychopharmacotherapy. It was found [1] that in paroxysmal schizophrenia, combined treatment with antidepressants and antipsychotics is prescribed in 50.6% of all courses of treatment, monotherapy with antipsychotics - in 41.4% and antidepressants - in 2.3%. It also turned out [9] that 70-80% of inpatients and 30-40% of outpatients with schizophrenia receive antidepressants, while antidepressants are widely prescribed for an acute attack of the disease. In this regard, the data of D. Addington et al. are also of interest. [12], who interviewed more than 3,000 psychiatrists from the US, Canada, Australia, and Europe. Their results showed that antidepressants in combination with antipsychotics are prescribed by 33% of inpatients and 36% of outpatients with schizophrenia. At the same time, the addition of antidepressants as the method of first choice is considered by 58% of doctors in the treatment of depression in the structure of an acute attack, 54% - postpsychotic depression and 73% - depression in patients with stable chronic schizophrenia. According to the majority of interviewed physicians, the main clinical symptoms that necessitate the prescription of antidepressants are suicidal thoughts, a sharply lowered mood, a feeling of hopelessness, anhedonia, sleep disturbances, especially early awakenings, and ideas of guilt. At the same time, 33% of respondents indicated that they rarely or never use antidepressants in patients with schizophrenia because of the risk of increased severity of productive symptoms. In 2009A similar survey was conducted by G.E. Mazo and S.E. Gorbachev [6]. According to a survey of 591 physicians, nearly half (47%) of all patients with schizophrenia are prescribed combination therapy with an antipsychotic and an antidepressant.

At the same time, the addition of antidepressants as the method of first choice is considered by 58% of doctors in the treatment of depression in the structure of an acute attack, 54% - postpsychotic depression and 73% - depression in patients with stable chronic schizophrenia. According to the majority of interviewed physicians, the main clinical symptoms that necessitate the prescription of antidepressants are suicidal thoughts, a sharply lowered mood, a feeling of hopelessness, anhedonia, sleep disturbances, especially early awakenings, and ideas of guilt. At the same time, 33% of respondents indicated that they rarely or never use antidepressants in patients with schizophrenia because of the risk of increased severity of productive symptoms. In 2009A similar survey was conducted by G.E. Mazo and S.E. Gorbachev [6]. According to a survey of 591 physicians, nearly half (47%) of all patients with schizophrenia are prescribed combination therapy with an antipsychotic and an antidepressant. The absolute majority (98%) of respondents indicated that the development of depressive disorders is an indication for changing therapy, and 73% of respondents consider it acceptable to use antidepressants in the acute period of an attack of schizophrenia. Suicidal ideation has been identified as the main indication for prescribing antidepressants (90%), depressed mood (86%), melancholy (83%), anxiety (70%), anhedonia to a lesser extent (50%), early awakenings (41%). The main factors limiting the use of antidepressants in patients with schizophrenia, 56% of respondents indicated the risk of pharmacokinetic interactions, 47% - the possibility of exacerbation of psychotic symptoms, 24% - the risk of suicidal tendencies. At the same time, 20% of respondents did not find significant restrictions on the use of antidepressants. A detailed assessment of the risk of exacerbation of acute psychotic symptoms as a result of the prescription of antidepressants was also carried out. Only 2% rate this risk as high, 34% as medium.

The absolute majority (98%) of respondents indicated that the development of depressive disorders is an indication for changing therapy, and 73% of respondents consider it acceptable to use antidepressants in the acute period of an attack of schizophrenia. Suicidal ideation has been identified as the main indication for prescribing antidepressants (90%), depressed mood (86%), melancholy (83%), anxiety (70%), anhedonia to a lesser extent (50%), early awakenings (41%). The main factors limiting the use of antidepressants in patients with schizophrenia, 56% of respondents indicated the risk of pharmacokinetic interactions, 47% - the possibility of exacerbation of psychotic symptoms, 24% - the risk of suicidal tendencies. At the same time, 20% of respondents did not find significant restrictions on the use of antidepressants. A detailed assessment of the risk of exacerbation of acute psychotic symptoms as a result of the prescription of antidepressants was also carried out. Only 2% rate this risk as high, 34% as medium. More than half (55%) consider the likelihood of such an exacerbation insignificant, and 9% - do not believe at all that the appointment of antidepressants can lead to an exacerbation of psychosis.

More than half (55%) consider the likelihood of such an exacerbation insignificant, and 9% - do not believe at all that the appointment of antidepressants can lead to an exacerbation of psychosis.

It can be seen from the data presented in the review that the discussion in the scientific community, the ambiguity and inconsistency of many provisions regarding depression in schizophrenia reflect the picture that has developed in practical public health. Despite the fact that much attention has been paid in the scientific literature to justify the limitations of the use of antidepressants in patients with schizophrenia, for practitioners, the addition of antidepressants to antipsychotics in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia with depression has become almost the main strategy of therapy. Moreover, this approach is used by most doctors, regardless of the standards of therapy existing in different countries. And although the choice of practitioners cannot be assessed from the standpoint of evidence-based medicine, it is confirmed by daily clinical observations. This dictates the need for special studies that would make it possible to realistically assess the role of antidepressants in the treatment of depression in schizophrenia.

This dictates the need for special studies that would make it possible to realistically assess the role of antidepressants in the treatment of depression in schizophrenia.

[1] In some cases, the use of a psychometric tool such as the Calgary depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS) [13], which allows differentiating depressive phenomena, negative symptom complexes and extrapyramidal disorders, can help in some cases, but it is not mandatory in everyday life. medical practice.

How to distinguish depression from schizophrenia? Symptoms of depression in schizophrenia — CMH "Alliance"

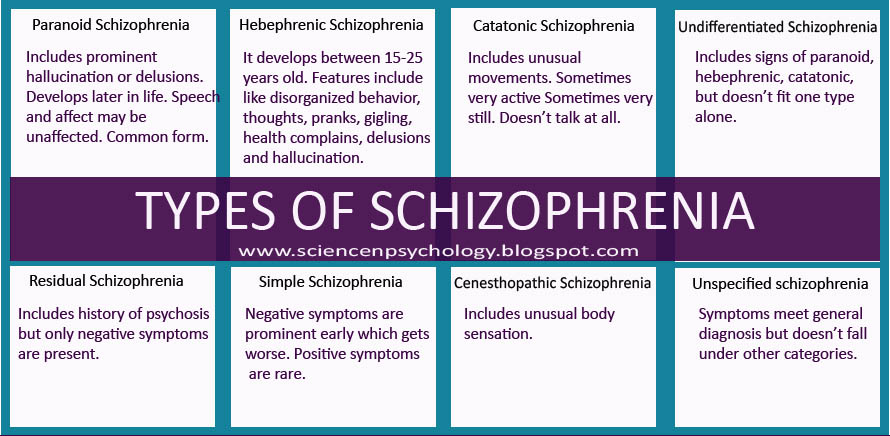

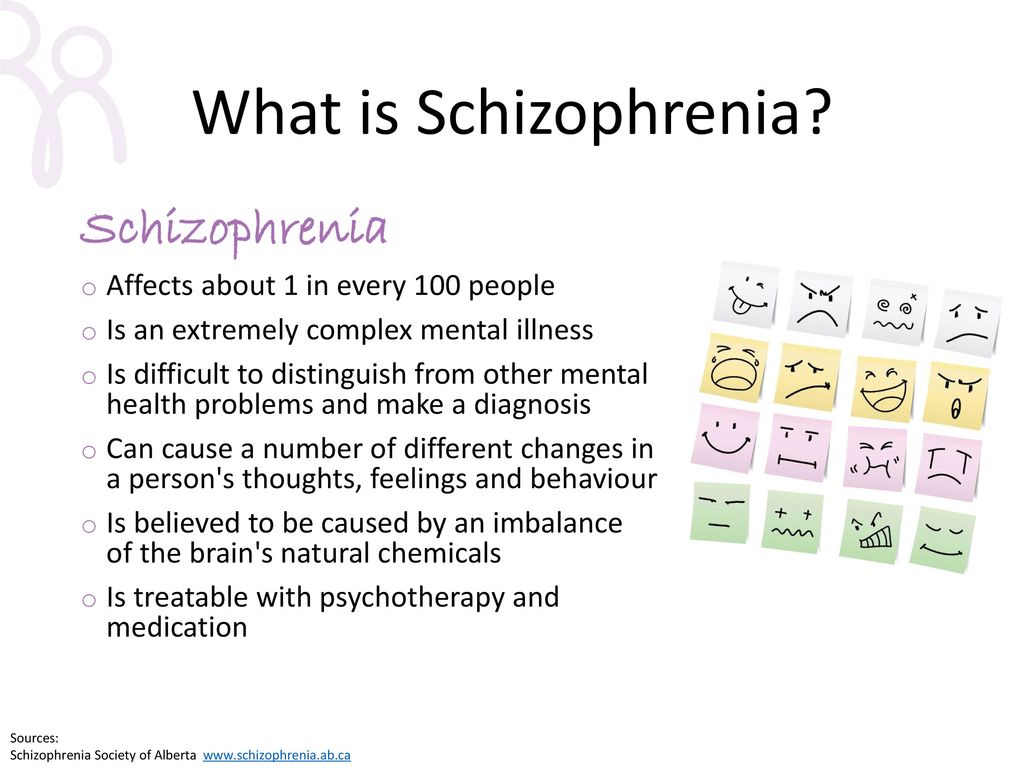

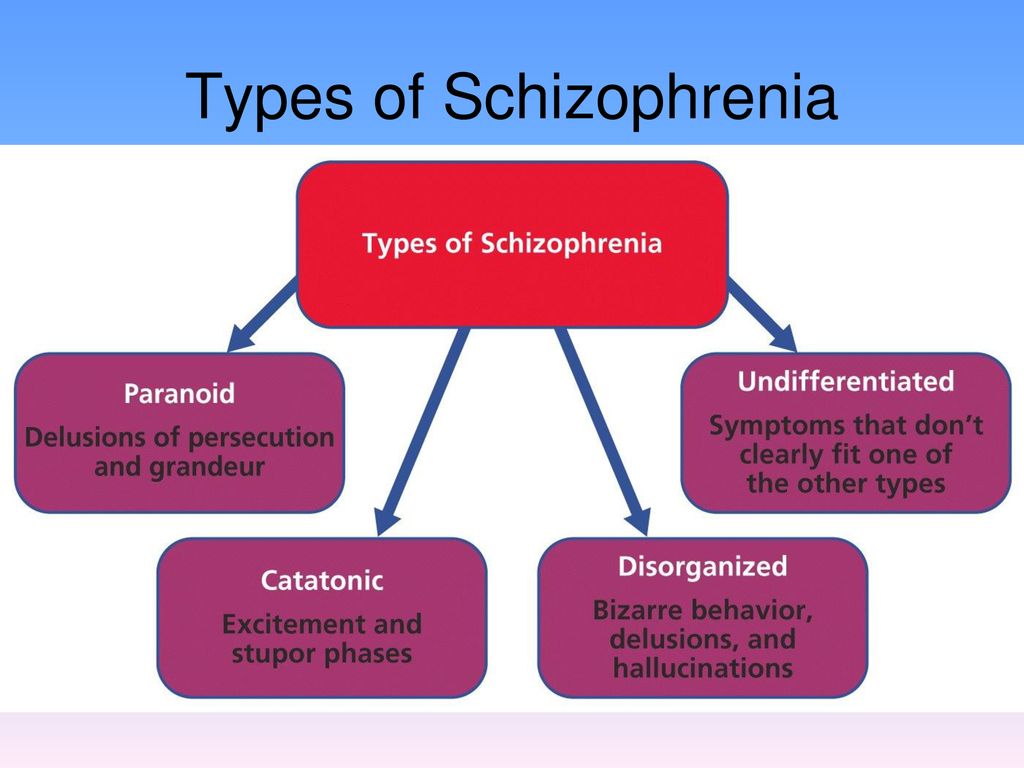

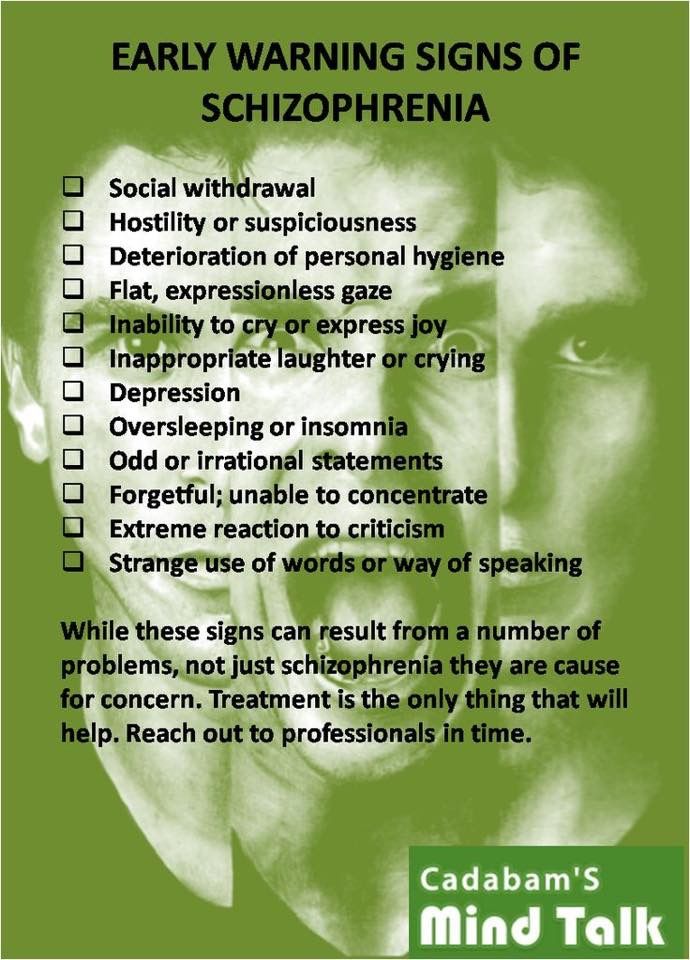

Depression and schizophrenia can have similar symptoms - depressed mood, guilt, "looping" a person on inadequate ideas (that he is seriously ill or has not succeeded in life). Both there and there, a person may not get out of bed for days or weeks, abandon his usual activities, stop communicating with loved ones and even try to commit suicide.

Important

Only a psychotherapist can distinguish between depression and schizophrenia. It is possible that a person suffers from both (depressive schizophrenia), so it is not worth postponing a visit to a specialist.

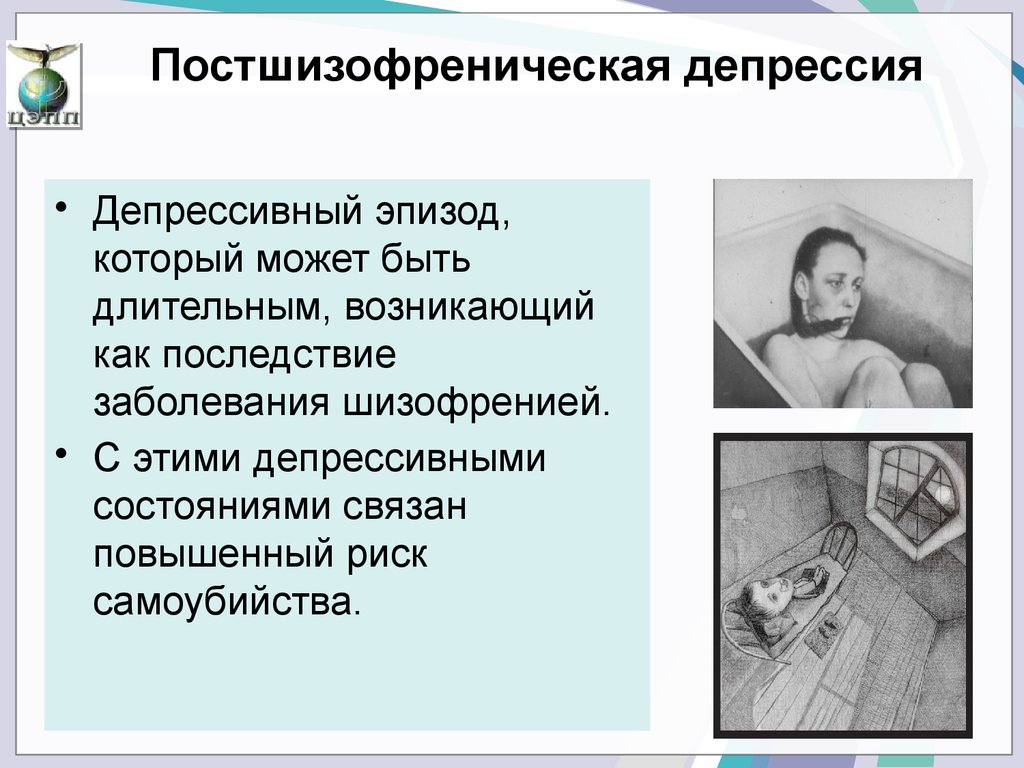

Depression can also occur after schizophrenia - due to exhaustion of the body and side effects of therapy. In case of post-schizophrenic depression (depression after schizophrenia), the attending physician must adjust the therapy - change the combination of drugs, select adequate dosages. You should not self-medicate and postpone going to the doctor, because in this state a person has a high risk of suicide.

Depression in schizophrenia

One in four people with schizophrenia experience depression. Manifestations of depression dominate, while signs of mental illness are slightly present, more often with negative symptoms (lack of will, emotional coldness) than with positive ones (delusions, hallucinations).

Symptoms of depression in schizophrenia are confirmed, which manifest themselves as follows:

- psychomotor retardation - a person does not get out of a state of inhibition, constantly stays in indifference (apathy) and does not want to do anything;

- gloominess, melancholy, indifference to everything around - a person has no reaction to what is happening, he equally indifferently perceives both joyful and sad events.

- sleep disturbance and anxiety.

Can depression turn into schizophrenia?

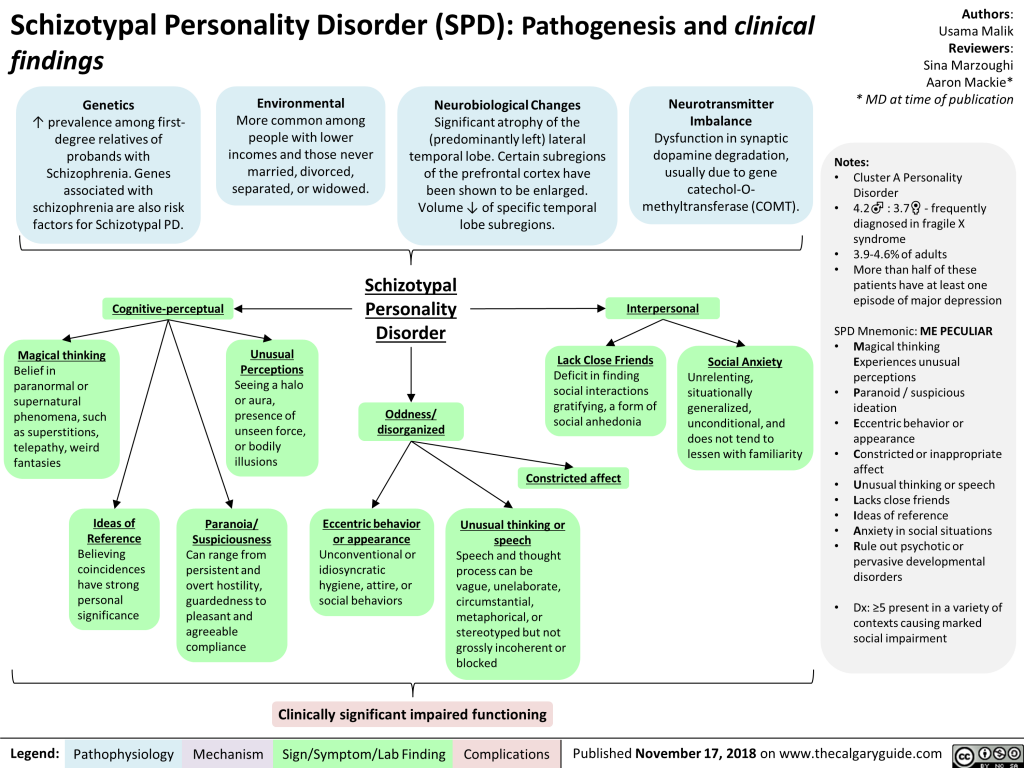

It happens that prolonged depression gradually turns into schizophrenia. An experienced specialist will see signs of schizophrenia even at the beginning - symptoms unusual for depression, changes in tests, insufficient effect of drugs.

Special methods help to diagnose the problem in time:

- Clinical and anamnestic examination - a psychiatrist questions a person and identifies symptoms (overt and latent).

- Pathopsychological study - a clinical psychologist reveals specific thinking disorders in a person.

- Modern laboratory and instrumental methods (Neurotest, Neurophysiological test system) - allow you to accurately, objectively confirm the diagnosis of "schizophrenia" and assess the severity of the disorder.

Clinical and anamnestic examination in psychiatry is considered the main diagnostic method. The psychiatrist talks with the patient, notes the features of the mental state, observes facial expressions, reactions to questions, intonation, notices what is not visible to the layman.