Brene brown joy

Accessing Joy and Finding Connection in the Midst of Struggle

Brené Brown: Hi everyone, I’m Brené Brown and this is Unlocking Us.

[music]

BB: And if you can hear excitement in my voice, it’s because I’m sitting across from, in real life, my friend Karen Walrond today. And she’s helping me. She’s really helping me. You may remember, Karen, we’ve done a two-part podcast on The Lightmakers Manifesto, her new book, which is all about working for change without losing your joy, and I literally just called her and said, “Will you be on the podcast because I’m losing my mind? I’m in such deep struggle and I can’t access any joy, I feel guilty if I’m happy about something, because the world is such a shit show right now and people are in so much pain, and I know that that’s not good, and I write about that not being good, but I can’t pull myself out of it and I don’t know what’s going on.” And she sits down with me, and it was just healing.

That’s the word I have to use. It was healing. Her words are healing, her images are healing, it was healing. I’m so glad you’re here, if you’re struggling with how to be fully connected in your life and feel joy and acknowledge beauty, and also fight for the things that we need to fight for right now, this will be a great podcast for you. It’s a game changer for me. I’m so glad you’re here.

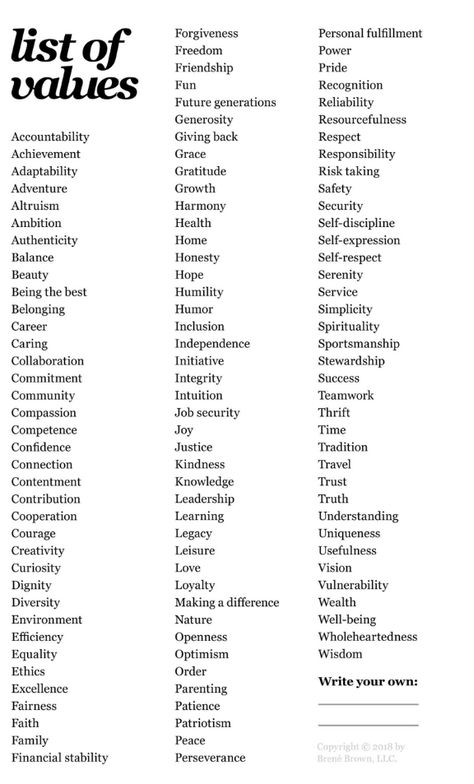

BB: Alright, before we jump into the conversation, let me tell you about my friend Karen Walrond. She’s a lawyer, leadership coach, photographer, and activist, who is wildly convinced that we are all uncommonly beautiful. Her first book, The Beauty of Different: Observations of a Confident Misfit, provides irrefutable evidence, the only kind of evidence Karen would ever provide, that the thing that makes us different is the source of our super power. Oh, it’s such a good book. Her current book, The Lightmaker’s Manifesto: How to Work for Change While Holding on to Your Joy, helps us name the skills, gifts, values, and actions that bring us joy, identify the causes that spark our empathy and concern, and then put it all together to change the world. Born in Trinidad and Tobago. Karen currently lives in Houston, lucky me, with her British husband, Marcus, who’s my favorite, their American daughter, Alexis, who’s also my favorite, and Soca, the super mutt. Let’s jump into the conversation. Hi everybody, I’m here with my friend. Writer, creative, photographer, podcast host, just person extraordinaire, Karen Walrond. Hi Karen.

Born in Trinidad and Tobago. Karen currently lives in Houston, lucky me, with her British husband, Marcus, who’s my favorite, their American daughter, Alexis, who’s also my favorite, and Soca, the super mutt. Let’s jump into the conversation. Hi everybody, I’m here with my friend. Writer, creative, photographer, podcast host, just person extraordinaire, Karen Walrond. Hi Karen.

Karen Walrond: Oh, hi friend. How you doin’?

[laughter]

BB: I’ve been better.

KW: Yeah, child.

[laughter]

BB: I’ve been better.

KW: Yeah.

BB: You want to just tell them what the first thing you said to me when you walked in here. It was so mean.

[laughter]

KW: Mean? I’m never mean to you. What did I say?

BB: No, what do you think you said? “I know what you need.”

KW: I did, I said, “You need a sabbatical. ”

”

BB: And I said, “Oh my God, I think I’ll take one.”

KW: And then you said, “No I won’t.”

[laughter]

BB: Yeah, “Because you said for how long?”

KW: Yeah, yeah. For how long?

BB: You said, “A year.”

KW: And I said, “A year.” I said, “You should take a year. You should get bored. I need you to get bored.”

BB: And then I fought her, and I said, “I get bored, I get bored after a week.”

KW: And I said, “No, you don’t, you get restless. There’s a difference. I need you to get bored. Bored. Bored. Bored.”

BB: Yeah. A year’s sabbatical. I think in all honesty, I’ll give y’all the set up for this conversation, I’m not falling apart, but I’m perpetually not okay. And every time I seem to get the earth under my feet a little bit, it starts moving again, which means there’s a problem, I’m trying to control the earth under my feet.

KW: And I suspect that that’s the feeling that a lot of us share.

BB: Yeah.

KW: Yeah.

BB: I don’t know. I do know, I actually don’t know, and I do know, but I think one of the things… There’s many things going on for sure. Really, really hard year last year. COVID, two years, super hard season for my marriage, COVID is hard, hard parenting, making all those decisions. I got hurt, of course, playing pickle ball and limped around for two or three months. I don’t understand why that happened because I did play tennis, a lot of tennis in my 20s, so I jumped back on that court and went crazy, competitive, then got hurt, of course. But I’ve since learned consistency over intensity. Little hard stuff with my parents. I’m at that age. You know this age.

KW: I know that age, yeah. Intimately.

BB: Yeah. And then so I took, for the first time in my whole career, four weeks off.

KW: How’d that feel?

BB: It felt good. I didn’t get bored.

KW: You need to get bored.

BB: I know, I’m thinking about what you’re saying right now, it’s hot in here. It’s hot. I’m hot.

[chuckle]

BB: But I came back and then the Spotify Joe Rogan stuff happened, and I think that was harder on me than I thought.

KW: Yeah, I bet. It was tough and then you handle it, right? Because that’s what Brené does, and that’s what we all do, we handle it. And then you start to think about it. And then it hits you, right?

BB: Yeah, because a lot of the things that people wrote where I just kind of roll my eyes and people block things on the team or I delete them, but then you think about them and they’re like, threats against my kids…

KW: Sure.

BB: Threats against me.

KW: Only so much you can take, right?

BB: Yes. So, this is this good set up because then what I asked you about… Was it Monday?

So, this is this good set up because then what I asked you about… Was it Monday?

KW: Yes.

BB: I think we’ve seen each other up and down and steady… Would you agree?

KW: Yeah, we’ve known each other a long time. Yeah.

BB: But I think with the invasion of Ukraine and then these incredibly cruel dehumanizing laws in Texas around trans kids. I’m finding it hard to move through the world right now, and one of the things that’s happened, and I always know this as a flag, is I was at my son’s game on Saturday, and he made this beautiful shot and scored a goal, and it was so… And I jumped up and I was like, “Yes.” And then I started crying. Had to go to the bathroom. I’m like, “How dare I be excited about this when there are kids his age fighting in Ukraine. When there’s kids his age probably contemplating whether life is worth living, because of what the adults in the state, not all of us, but the leaders, some of the leaders are saying. ” And then in that moment where I realized that I couldn’t get to joy, I knew I was in trouble. And I thought about you.

” And then in that moment where I realized that I couldn’t get to joy, I knew I was in trouble. And I thought about you.

KW: Yeah, because you’ve got to get to joy.

BB: You have this thing that you say… And I want to make sure I get it right. You say that you will never apologize for embracing joy and beauty, even when the world is falling apart, because joy and beauty are your fuel for activism.

KW: Amen. I absolutely say that. And I stand by that. Yeah.

BB: You know I believe that, right?

KW: I hope so.

BB: I do. I’m going to read this to y’all, this is from Braving the Wilderness, and this is on the chapter on strong back, soft front, wild heart. Would you… I feel like right now, like it’s questionable back, hard front, and under the covers is where… So, here’s what I write.

BB: “The mark of a wild heart is living out the paradox of love in our lives, it’s the ability to be tough and tender, excited and scared, brave and afraid, all in the same moment. It’s showing up in our vulnerability and our courage, being both fierce and kind.” Here’s the part that gets me because I wrote it. Pissing me off. “A wild heart can also straddle the tension of staying awake to the struggle in the world and fighting for justice and peace, while also cultivating its own moments of joy. I know a lot of people, myself included, who feel guilt and even shame about their own moments of joy.” Then I write, “How can I play on this gorgeous beach with my family while there are people who have no home or safety? Why am I working so hard to decorate my son’s birthday cupcakes like cute little minions, when there are so many Syrian children starving to death? What difference do these stupid cupcakes really make?” Then I write, “They matter because joy matters. Whether you’re a full-time activist or a volunteer at your mosque or a local soup kitchen, most of us are showing up to ensure that people’s basic needs are met and their civil rights are upheld, but we’re also working to make sure that everyone gets to experience what brings meaning to life: love, belonging, and joy.

It’s showing up in our vulnerability and our courage, being both fierce and kind.” Here’s the part that gets me because I wrote it. Pissing me off. “A wild heart can also straddle the tension of staying awake to the struggle in the world and fighting for justice and peace, while also cultivating its own moments of joy. I know a lot of people, myself included, who feel guilt and even shame about their own moments of joy.” Then I write, “How can I play on this gorgeous beach with my family while there are people who have no home or safety? Why am I working so hard to decorate my son’s birthday cupcakes like cute little minions, when there are so many Syrian children starving to death? What difference do these stupid cupcakes really make?” Then I write, “They matter because joy matters. Whether you’re a full-time activist or a volunteer at your mosque or a local soup kitchen, most of us are showing up to ensure that people’s basic needs are met and their civil rights are upheld, but we’re also working to make sure that everyone gets to experience what brings meaning to life: love, belonging, and joy. These are essential irreducible needs for all of us, and we can’t give people what we don’t have; we can’t fight for what’s not in our hearts.”

These are essential irreducible needs for all of us, and we can’t give people what we don’t have; we can’t fight for what’s not in our hearts.”

BB: I’m going to end this section, there’s a couple of more paragraphs, but I’ll just end, “A wild heart is awake to the pain in the world but does not diminish its own pain. A wild heart can beat with gratitude and lean into pure joy without denying the struggle in the world. We hold that tension with the spirit of the wilderness. It’s not always easy or comfortable, sometimes we struggle with the weight of the pull, but what makes it possible is a front made of love and a back built of courage.

KW: I love that.

BB: You think all that’s true, right?

KW: I do, I do. And. And. So when I wrote my book, The Lightmakers Manifesto, I interviewed a lot of people, and I interviewed a lot of people who make it their life’s work. Activism. It’s not something they just do on the weekend, it’s what they do. And the thing that became really apparent in what they said is that activism, in order to have longevity in the work, has to have a rhythm to it, that there’s an ebb and there’s a flow, and I will say that the older I get, I’m starting to believe that that is the natural order of things. Is ebbing and flowing. It’s reason we have ebbing and flowing tides, we have waxing and waning moons, we have seasons. I think you ebb and flow and so just like…

And the thing that became really apparent in what they said is that activism, in order to have longevity in the work, has to have a rhythm to it, that there’s an ebb and there’s a flow, and I will say that the older I get, I’m starting to believe that that is the natural order of things. Is ebbing and flowing. It’s reason we have ebbing and flowing tides, we have waxing and waning moons, we have seasons. I think you ebb and flow and so just like…

BB: Wow wait, I’ve got to stop you here. I have goosebumps. Okay, you said the older you get, the more you believe that this is the order of things and what were the examples?

KW: The tides coming in and out, right? The moon, the phases of the moon, the seasons of the year. I think it is our nature, it is nature, it is natural to have an ebb and a flow. And in order to have longevity in activism, for example, you have to be able to ebb and flow, sometimes you go in hard and you fight, sometimes you have to stop. We inhale and exhale. Everything has a rhythm. Everything has a rhythm. And so, what I would say is just like we used to say, “Can women have it all?” And the answer to that is, “Yes, but maybe not all at the same time, right?” You can have all of these things, but you also have to be able to stop. You have to be able to regenerate. And what I would say is, and I’m very, very mindful of this now, and if I were to write my book again, I might move the chapters on self-compassion and self-care to the front, because I think we often think of being able to tap into joy or in self-care or self-compassion is something you do when we’re spent.

We inhale and exhale. Everything has a rhythm. Everything has a rhythm. And so, what I would say is just like we used to say, “Can women have it all?” And the answer to that is, “Yes, but maybe not all at the same time, right?” You can have all of these things, but you also have to be able to stop. You have to be able to regenerate. And what I would say is, and I’m very, very mindful of this now, and if I were to write my book again, I might move the chapters on self-compassion and self-care to the front, because I think we often think of being able to tap into joy or in self-care or self-compassion is something you do when we’re spent.

KW: And I think, honestly, if we do that when we’re spent, it might be a little too late, that what we do is we front-load with it, and then we gather the energy to go in and change the world and do the good things. Stopping and accessing joy and accessing gratitude is what reminds us what we’re fighting for, it reminds us what we want for the rest of the world, so I think… Yes, for sure. It is possible to do it. I think it’s necessary to do it, I think we can’t do it unless we tap into joy and tap into gratitude, and tap into appreciation and laughter and beauty, you have to do that. You have to… Because then… What are we fighting for?

It is possible to do it. I think it’s necessary to do it, I think we can’t do it unless we tap into joy and tap into gratitude, and tap into appreciation and laughter and beauty, you have to do that. You have to… Because then… What are we fighting for?

BB: I’m going to ask you a really hard question for me personally. Everything you said right now, I literally, I’m so pissed that I just shaved my legs, because I got goosebumps from head to toe, and now I’ve got razor stubble. What do you think the mechanism is, that moves you from knowing that, and living that, to it feeling a million worlds away. I know you’ve been there.

KW: Sure. Sure. You know I’ve been there, I’ve called you when I’ve been there.

BB: Yeah. No, I’ve seen it, but how do you think I get from knowing that, we’ll just use me as an example because I’m in the shit show right now, but what is it about us that moves us from moving with the tide, moving through the seasons, going with the ebb and flow, to fighting? To fighting it? What happens? How do we get here?

KW: So I would say for me, I make it a practice to identify the good and the beauty, I mean, I do it religiously, religiously. If I don’t have a practice of doing that when times are good, when times get tough, I won’t do it. Unless it’s innate, like brushing my teeth. We hear so much about gratitude practices, and I am just dogged about it, dogged about it, so that even in the difficult times like… Let’s just take for right now, let’s take the Ukraine. I will say, I was just telling my partner this, that every time I feel like, “Okay, I’m ready to go.” Something happens in the world and I’m like, “Seriously, how do I deal with this right now?” And so, there’s a couple of things that I do when I can feel that. What is the way that you say… When you’re hooked?

If I don’t have a practice of doing that when times are good, when times get tough, I won’t do it. Unless it’s innate, like brushing my teeth. We hear so much about gratitude practices, and I am just dogged about it, dogged about it, so that even in the difficult times like… Let’s just take for right now, let’s take the Ukraine. I will say, I was just telling my partner this, that every time I feel like, “Okay, I’m ready to go.” Something happens in the world and I’m like, “Seriously, how do I deal with this right now?” And so, there’s a couple of things that I do when I can feel that. What is the way that you say… When you’re hooked?

BB: Right, yeah, yeah, yeah.

KW: Then the first thing I do is maybe I’ll take a media break for a day. Trust and believe the world is not going to change so much in one day that you’re going to miss the opportunity to help. Right, so I’m like, “I got to get my head right.” So, I may take a media break. I also, for example, I follow all kinds of media that talk about good news, talk about the helpers, talk about the things that people are doing that are helping. And figure out how can I help those helpers, because often those helpers know better than I do.

And figure out how can I help those helpers, because often those helpers know better than I do.

BB: Yeah, yeah, for sure. They’re on the ground.

KW: They’re on the ground, they know what’s up rather than me. So if I can support them, then I can feel a little bit better, and then I will also make sure that I’m staying connected to my family and sometimes staying connected to my family means celebrating something great that they’ve done, and making sure that they’re okay and that everything’s set. But I do it literally every single day, I journal about it when I start my day, I do a prayer of thanks when I close my eyes at night, and I do it as a practice, so when hurricanes take my house away like one did, or when really tough things happen, I have so much of a practice of “Okay, it’s time for me to go to bed.”

KW: “What’s a good thing? What’s something good that happened? What is something that I can hang on to? What is something that I can hang hope on to, so that I can go to sleep and wake up tomorrow and try again?” And I think it really, really is a practice, I don’t think it… If you’re not used to doing that, it’s like an atrophied muscle, it can feel a little awkward to try to do it, and you can feel guilty, like, “How dare I do that?,” because it’s not something that you’ve done all the time, and so I do it, I’ve been doing it for 20 something years, maybe even 30 years now, and it is just part of what I do every single day, I have to. It’s the only way I can make it through.

It’s the only way I can make it through.

BB: Wow. And I’ve never known you not to do it. Yeah. And you’ve taught me a lot. I don’t know if you know this, I was thinking about, while I was lying in bed last night because I knew I was going to get to talk to you today. I’m going to start crying. There’s a 99% chance. But the year that we met, I was taking up photography. Do you remember that?

KW: Yep. Uh huh.

BB: And you were this amazing photographer, and for Lent that year, I don’t ever give up anything for Lent, I always add something positive, and so I made myself take a picture with my big camera, which I barely knew how to use, although you taught me like F stops and stuff, I took a picture every day, of something I thought was beautiful during Lent. Fucking changed my life.

KW: Yeah. Yes.

BB: It changed my life.

KW: It’s so common at the end of the year, people to say, “Well, that was a crappy year. Don’t let the door hit you on the way out. I can’t wait for the new year.” I often tell people, “Go look in your cell phone camera at your archives, and you’re going to notice that the year wasn’t as bad as you thought.” Because we tend to pull out our cameras when something good has happened, we’ve run into a friend or we’re having dinner, we’ve got a great latte or whatever, we pull it out and I’m like, “I bet if you scroll through, you’re going to find moments that you forgot, were really great in your life.” And back to this feeling guilt about joy, there’s a part of me that really feels… I don’t know if it’s partially cultural, I don’t know what it is, but to me, if we feel guilt about the joy then the bad guys win.

Don’t let the door hit you on the way out. I can’t wait for the new year.” I often tell people, “Go look in your cell phone camera at your archives, and you’re going to notice that the year wasn’t as bad as you thought.” Because we tend to pull out our cameras when something good has happened, we’ve run into a friend or we’re having dinner, we’ve got a great latte or whatever, we pull it out and I’m like, “I bet if you scroll through, you’re going to find moments that you forgot, were really great in your life.” And back to this feeling guilt about joy, there’s a part of me that really feels… I don’t know if it’s partially cultural, I don’t know what it is, but to me, if we feel guilt about the joy then the bad guys win.

BB: God. Yes.

KW: Right.

BB: Yes, because I can’t get out of bed. And I get fearful about speaking out about things that are important to me and… Yeah, they win.

KW: They win. We can’t let them win, we can’t let them win, and joy is how we develop resiliency. I was talking to our friend Laura the other day, and I was saying “The idea… ” I’m a black woman, I’m from the Caribbean, I’m from Trinidad that has a huge Carnival, which would normally be going full bore this week, and I was thinking about how Carnival in Trinidad and probably in Brazil as well, and even in New Orleans, it comes from the enslaved… The enslaved are the people who started the carnival, it certainly is in Trinidad, and talk about oppression and sadness and horror and trauma and everything. And there’s this time when we’re going to dance and sing and play. It’s because of things like that, that we become resilient, is because of being able to tap into that or making… Not even the capability, but making the effort and the intention to tap into that, that we remind ourselves of our humanity. We remind ourselves of why we’re interconnected, why it matters, why our work and our tears matter, they matter because there’s good. And so for me…

I was talking to our friend Laura the other day, and I was saying “The idea… ” I’m a black woman, I’m from the Caribbean, I’m from Trinidad that has a huge Carnival, which would normally be going full bore this week, and I was thinking about how Carnival in Trinidad and probably in Brazil as well, and even in New Orleans, it comes from the enslaved… The enslaved are the people who started the carnival, it certainly is in Trinidad, and talk about oppression and sadness and horror and trauma and everything. And there’s this time when we’re going to dance and sing and play. It’s because of things like that, that we become resilient, is because of being able to tap into that or making… Not even the capability, but making the effort and the intention to tap into that, that we remind ourselves of our humanity. We remind ourselves of why we’re interconnected, why it matters, why our work and our tears matter, they matter because there’s good. And so for me…

BB: Wow that’s beautiful.

KW: I feel like joy is… You have to do it, otherwise, why are we here?

BB: What’s the point?

KW: What is the point? What is the point of helping people in Ukraine if we don’t know what that help could get for them? We don’t know the joy that could happen. That’s why we do it.

BB: It’s so crazy. You really answered the question, you really unlocked this… You gave us some keys. Because people listening are like, “Brené, you’ve been writing about a lot of this stuff for a long time, what’s wrong with you?” The thing is that it’s a practice, it’s not a knowledge base.

KW: Well, yes.

BB: And that’s what you said, it’s a practice, you’re dogged about your practice, and it reminds me of the James Clear podcast.

KW: On habits, yup.

BB: Yeah, we don’t rise to our most lofty goals, we fall to our worst systems. And the systems that I’ve had in place, small things like gratitude after grace, we’ve just been skipping. Writing things down for me that I’m grateful for. Taking pictures of things that I think are beautiful, to not share with anyone but for myself. I’ve let go of so many of those practices.

Writing things down for me that I’m grateful for. Taking pictures of things that I think are beautiful, to not share with anyone but for myself. I’ve let go of so many of those practices.

KW: And let’s be real, one word. In pain, often, those are the first ones that we want to let go. I know that for me.

BB: For sure.

KW: If I’m in crisis or…

BB: Yeah, they piss me off when I’m in crisis.

KW: Sure, I’m not going to go work out, I don’t have time to do that, or I’m not going to go do the things that I’m supposed to do to take care of myself, I don’t have time to do that. I mean, I’m 54, I’m about to be 55 years old, I’m just getting this. Like, I’m just getting how important the practice is. And I’m probably in the last four or five years, I’ve finally been like, “No, I have to do this.” If it is that the only thing I’m grateful for at the end of the day is I took care of myself, I stopped, I drank extra water, I hung out with my partner or my daughter, then that’s it, that’s fine. But I have to do this, because if I don’t do that, I know I’m going to feel worse at the end of the day. I’m going to feel worse. And the worse I feel, the more likely I am to give up, and I’m not giving up.

But I have to do this, because if I don’t do that, I know I’m going to feel worse at the end of the day. I’m going to feel worse. And the worse I feel, the more likely I am to give up, and I’m not giving up.

BB: So, can I share something personal about you?

KW: Okay, sure. Uh-oh. [laughter]

BB: We can take it out if you don’t like it.

KW: Alright, go ahead.

BB: I saw this practice in you, and this is probably one of the reasons I so selfishly was like, “Can you just talk to me on the podcast? Because I know I’m not feeling alone.” I saw this practice in you before Harvey. Harvey is the hurricane that…

KW: Took our house.

BB: That destroyed their house. Massive trauma.

KW: Yeah.

BB: Yeah. But I saw you not the day of Harvey, or the day after Harvey, or the buckets of water, but man, not too far after the actual hurricane, the water started to subside, I saw you pull yourself through that with this practice.

KW: Yes, 100%.

BB: Is that true?

KW: Yes. There’s no way I would have been able to handle it. And what was really interesting for Harvey, which is a bit different than the trauma that’s going on in the world, because this is a personal trauma, but what was very interesting is because I had been… What’s one good thing, practice for decades at that point. What shocked me was how easy it was to find the good thing. Even as we were wading out of our house, the day we waded or the night we waded out, it was midnight, a neighbor who hadn’t flooded took us in for the night, and it was a neighbor that we didn’t know very well, and that was my one good thing, that there were good people in the world.

KW: We were literally leaving everything behind. We collapsed in their guest room or their game room, we had left 10 minutes earlier, knew the house was filling up, and I could still go, “Okay, one good thing today, I’m safe and dry. And these people who I don’t really know that well who’ve taken us in, that’s a huge good thing.” And the only reason I could stop to do that is because I’ve been doing it for 20 years, I had made the practice of doing it in 20 years when things were great, so it was very easy for me to tap. Now, that’s a little bit different than watching injustice in the world, because the gratitude I felt in that moment was so profoundly personal, and every night of the two, three weeks of mucking houses and doing everything else, I could always come up with something really, really huge. A stranger showed up and knocks on our door and said, “Hey, do you guys need help? I’ll help you muck out your house.”

And these people who I don’t really know that well who’ve taken us in, that’s a huge good thing.” And the only reason I could stop to do that is because I’ve been doing it for 20 years, I had made the practice of doing it in 20 years when things were great, so it was very easy for me to tap. Now, that’s a little bit different than watching injustice in the world, because the gratitude I felt in that moment was so profoundly personal, and every night of the two, three weeks of mucking houses and doing everything else, I could always come up with something really, really huge. A stranger showed up and knocks on our door and said, “Hey, do you guys need help? I’ll help you muck out your house.”

KW: So that was something very, very personal, but as you have this practice, and you start to also look for… I do, look for things that, “Okay, this is a really crazy day, I need to have something to say was good about this day tonight when I go to bed.” So I’ll look for it, and like I said, I have social media accounts that I follow that are good news, what’s happening, and so I will go look for those things, or I will go find something, or I’ll go read a story, or something that I can do just to remind myself, even with the crazy, they’re still good. They’re still good. And because I have that practice when life is great… As a matter of fact, honestly, when life is really good, it’s harder to find something when things aren’t really bothering me that much, and it was a fine day, I’m like, Okay, well, what is… I had a good coffee this morning.

They’re still good. And because I have that practice when life is great… As a matter of fact, honestly, when life is really good, it’s harder to find something when things aren’t really bothering me that much, and it was a fine day, I’m like, Okay, well, what is… I had a good coffee this morning.

KW: But when things are bad, that’s when you really start to do it, and you have to have a practice and you have to have that practice. If you are a person who cares about other people, if you are a person who cares about the world, you have to have that practice so you can remind yourself and gather the energy to go back in and keep working for that. It’s not about healing the wounds, although it definitely helps, it’s about gathering the energy to go in. It’s a proactive thing, if that makes sense.

BB: Wow, I needed to hear this. You’re my one amazing thing today.

KW: Well, I’m glad to hear that. You’re mine.

BB: I know really, and I’m so glad to be honest with you, that I’m falling apart a little bit in front of all of y’all, because I think sometimes people believe if you know this, that’s your defense, but it doesn’t mean jack shit actually, if you’re not practicing it. I know this, and so let me just take it a step back a little bit.

I know this, and so let me just take it a step back a little bit.

KW: Sure.

BB: I’m trying to think about what gets in the way, what stopped my practice? And I think for me, it could be just exhaustion.

KW: Sure.

BB: It could be just too much.

KW: Yes. Yeah.

BB: Too much. Yeah, and not acknowledging when things are too much.

KW: Yeah.

BB: I don’t know. What do you think? Not just for me, but for everybody. What gets you off your practice?

KW: Well, there’s a couple of things, I think. One is, of course, when things are just hard and overwhelming and you’re full of feelings, that’s enough to get you off your practice. I think, honestly, not to be all rah-rah about it, but I think, frankly, capitalism and grind culture does it.

BB: God, yeah.

KW: I feel like we think, for some reason, the words “self-compassion,” “self-care,” even “privilege,” have gotten a bad wrap. Those are really ugly, horrible words. Self-compassion is considered selfish. I contend that the word privilege, it’s not a dirty word any more than being blonde or tall is. If you have privilege, you have privilege, it’s what you do with it. Privilege gives you the privilege of helping other people. And so, I feel like a lot of times we just think, to your question about what knocks us off our game, is we think that if we stop or if we even recognize that we’re in pain, that’s weakness, and that’s selfish, and that’s not a strong back.

Those are really ugly, horrible words. Self-compassion is considered selfish. I contend that the word privilege, it’s not a dirty word any more than being blonde or tall is. If you have privilege, you have privilege, it’s what you do with it. Privilege gives you the privilege of helping other people. And so, I feel like a lot of times we just think, to your question about what knocks us off our game, is we think that if we stop or if we even recognize that we’re in pain, that’s weakness, and that’s selfish, and that’s not a strong back.

[laughter]

BB: Sorry, we’re having technical difficulties. We’ll see you next time.

KW: I think that’s the culture we’re in, and everything tells us that. If you’re not producing, if you’re not moving, if you dare look away, then you’re part of the problem, because we need all hands on deck. And I don’t think that’s true. I think we need hands on deck, and sometimes it’s not going to be your hands, and sometimes it will be your hands and somebody else was going to be able to take the break.

BB: Someone else is in a different season.

KW: Yes, absolutely.

BB: Mm, man. You know what really pissed me off about what you just said?

[laughter]

KW: We do that.

BB: Yes.

KW: We do that to each other.

BB: We do do that.

KW: We do piss each other off.

BB: We do.

[laughter]

BB: Is the tough part, because I keep telling myself, even yesterday when I was, again, having a hard time, I was like, “Come on, Brené. Jesus, toughen up.”

KW: Yeah. Yes, we do that all the time. And so, what I would suggest, one is… You knew I love journaling.

BB: Y’all should just wait.

[laughter]

KW: So, I’m a big journaler. I’m not about to tell everybody to journal although, really, you should all journal. But one thing that helps me, especially when I’m struggling is I ask myself three questions. And this is a really good, easy thing to do, and you don’t even have to have a page. Literally, just jot it down. And the three questions are, “How can I feel connected today? How can I feel healthy today? And how can I feel purposeful today?” How can I feel connected, healthy, and purposeful? And you think about it in that moment. How can I feel connected? Okay, I don’t want to talk to anybody. You know what? I’m going to text Brené. I’m just going to be like, “Hey, having a hard time but thought of you.” So, I’m going to write that down on my to-do list. How can I feel healthy today? Well, I sure as hell am not in the mood to go to the gym, let’s say. I’m tired, I’m exhausted. You know what? I’m just going to drink a lot of extra water today. Or, I am going to take a disco nap, a 20-minute nap at some point today. And I put that on my to-do list.

But one thing that helps me, especially when I’m struggling is I ask myself three questions. And this is a really good, easy thing to do, and you don’t even have to have a page. Literally, just jot it down. And the three questions are, “How can I feel connected today? How can I feel healthy today? And how can I feel purposeful today?” How can I feel connected, healthy, and purposeful? And you think about it in that moment. How can I feel connected? Okay, I don’t want to talk to anybody. You know what? I’m going to text Brené. I’m just going to be like, “Hey, having a hard time but thought of you.” So, I’m going to write that down on my to-do list. How can I feel healthy today? Well, I sure as hell am not in the mood to go to the gym, let’s say. I’m tired, I’m exhausted. You know what? I’m just going to drink a lot of extra water today. Or, I am going to take a disco nap, a 20-minute nap at some point today. And I put that on my to-do list.

KW: How can I feel purposeful today? Well, what can I do? What can I do? Maybe I’m going to read the paper and find out more… I don’t even know where Ukraine is on a map, I’m going to do that. I don’t even understand what the phrase “defund the police” means, I’m going to look that up. Or donate something to a cause or whatever. But what’s something that taps into purpose? And put that on my to-do list. And that’s it. And start a practice of doing that. And a lot of times what I find answering those questions does, it tells me, “Oh, I’m in struggle.” Like, how can I feel healthy today? I don’t want to feel healthy today. Okay, what was that about? So, then you say, “You know what? I just need to be gentle with myself.” How can I feel purposeful? I don’t know. How can I feel purposeful? Okay, what’s one little thing I can do? A little tiny thing I could get educated on something. I can ask. And having that starts to make you feel like, “Okay. Well, I’m doing something.”

I don’t even understand what the phrase “defund the police” means, I’m going to look that up. Or donate something to a cause or whatever. But what’s something that taps into purpose? And put that on my to-do list. And that’s it. And start a practice of doing that. And a lot of times what I find answering those questions does, it tells me, “Oh, I’m in struggle.” Like, how can I feel healthy today? I don’t want to feel healthy today. Okay, what was that about? So, then you say, “You know what? I just need to be gentle with myself.” How can I feel purposeful? I don’t know. How can I feel purposeful? Okay, what’s one little thing I can do? A little tiny thing I could get educated on something. I can ask. And having that starts to make you feel like, “Okay. Well, I’m doing something.”

KW: Even if what the doing something is, is stepping back a bit and taking a break and gathering that energy, because now it feels thoughtful and intentional, and you’ll cut yourself some slack when you do that. And I think that’s just really important to be able to recognize and acknowledge where you are in that ebb and flow, where you are in the rhythm, because that identification of that is what’s going to help you get back in the rhythm again, and get back in that ebb and flow, and figure out what you can do.

And I think that’s just really important to be able to recognize and acknowledge where you are in that ebb and flow, where you are in the rhythm, because that identification of that is what’s going to help you get back in the rhythm again, and get back in that ebb and flow, and figure out what you can do.

BB: God, I love this conversation. I even started, before you even told me about waxing and waning and ebbing and flowing and seasons, I actually said, “I can’t get settled in the earth.”

KW: Mm-hmm.

BB: The earth is shifting underneath me. And then, I’m trying to move the earth to match my feet, instead of…

KW: Moving with the earth.

BB: Moving with the earth. Yeah, I’m going to work this metaphor to death now. But for me, what you’re talking about is getting grounded. Those three questions are grounding.

KW: Yes.

BB: Like, to get moved. And it’s so funny, the connection thing. Steve the other day was like, “God, what are you watching?” And I was like, “I’m watching my show.” He’s like, “Why are you watching all these mysteries in France, in French?” And I was like, “Because the U.S. mysteries are not far enough away.”

And it’s so funny, the connection thing. Steve the other day was like, “God, what are you watching?” And I was like, “I’m watching my show.” He’s like, “Why are you watching all these mysteries in France, in French?” And I was like, “Because the U.S. mysteries are not far enough away.”

[laughter]

BB: I need to disconnect from the continent, baby. I’m solving shit in France. Like, I have moved on.

KW: In 1843.

[laughter]

BB: I’m gone. Gone.

KW: Sure, absolutely. And I think you said that you’re going to work it to death, that metaphor. But I think that metaphor is really… I mean, just helpful. I think there’s a reason why when we want to calm down, like watching the ocean and watching the waves crash…

BB: Yes.

KW: Like that rhythm thing feels so good, because that’s what we’re all wired to do. We’re wired to do that, that sort of back and forth.

BB: I wish y’all could see her right now, she’s moving. Like, now I’m going to crawl in her lap, hold on.

KW: That’s why we like hammocks. There’s something about that, and just fall into that. Fall into that. Fall into that, because you’re going to get farther that way.

BB: Remind us of the three questions again.

KW: How can I feel healthy? How can I feel connected? How can I feel purposeful? Those are the three questions. Ask yourself that every day. Done it for a week, 10 days. And for me, I journal it. But, again, if all you want to do is just answer those questions. But the point is really just to stop and check in, and just check in. How am I doing? Is this the part of the rhythm where I go hard, and I help and I do stuff? Or is this the part of the rhythm where I need to stop and gather, and gather the energy again and just inhale? Like, when we work out, we inhale and then we put all the effort in when we exhale. But at some point we’ve got to inhale in order to be able to do that again. It’s that back and forth, that flow.

But at some point we’ve got to inhale in order to be able to do that again. It’s that back and forth, that flow.

BB: You’re my friend, Karen Walrond.

KW: You’re mine, Brené Brown.

[music]

BB: Wow, okay. You need to read Karen’s book. I’ll see you outside somewhere swaying. I’ll know if you’ve read it if we see each other, and instead of shaking hands or fist-bumping, we just sway together. It’s The Lightmaker’s Manifesto: How to Work for Change Without Losing Your Joy. I was looking, I was like, “Hey, my name is at the top of the book,” because I wrote an endorsement for it. And it says, “Karen Walrond shines her light so we can find our own.” Well, God bless America, truer words have never been spoken than today, right?

KW: Oh, thank you so much. I appreciate that.

BB: Yeah. I’ve lost my way a little bit, and just knowing is not enough. I’m not doing, I’m not practicing.

KW: Sabbatical.

BB: Goddamn. I’ll see y’all next year, I’m on a one year…

[laughter]

BB: I am going to take some time, and I don’t know what it’s going to look like, but I am going to take a sabbatical and I’m going to take long enough that I get bored.

KW: Yeah.

BB: I’m going to call your ass and be like, “I’m losing my mind.”

KW: I’m like, “You’re just restless. Get bored. Get bored.”

BB: Thank you for being here.

KW: Always a pleasure, always.

BB: Okay. Y’all can find everything about Karen. Oh, photos too. Will you send photos of the journal?

KW: I definitely will, I promise.

BB: Yeah. I mean, wait until you see them, right? It’s next level. It’s not bullet journaling, because she was doing this before that was even invented. It’s art and journaling and…

KW: Thank you. Making a mess.

Making a mess.

BB: But it’s beautiful.

KW: Thank you.

BB: Yeah. You can go to the episode page on brenebrown.com, and just look under Unlocking Us or just do a search for Karen Walrond. You’ll also find on Unlocking Us, we did a two-part podcast on just the book, where we talked about some really hard and good important things. Yeah. Y’all stay awkward, brave, and kind. And let’s end with the three questions.

KW: How can I feel connected? How can I feel healthy? How can I feel purposeful?

BB: Karen Walrond right here. Boom. Thank you.

KW: My pleasure.

[music]

BB: Unlocking Us is a Spotify original from Parcast, it’s hosted by me, Brené Brown. It’s produced by Max Cutler, Kristen Acevedo, Carleigh Madden, and Tristan McNeil, and by Weird Lucy Productions. Sound design by Tristan McNeil and music is by the amazing Carrie Rodriguez and the amazing Gina Chavez.

© 2022 Brené Brown Education and Research Group, LLC. All rights reserved.

4 Ways to Stop Foreboding Joy I Psych Central

Foreboding joy can be described as that moment when joy is interrupted by thoughts of “but what if something bad happens.”

Happiness is precious to us. For many people, it’s the epitome of life achievements. What more do you need if you’re happy?

Experiencing joy unfettered can be an amazing experience, but what happens when joy comes with strings attached?

Can that joy turn into a fear of happiness?

Foreboding joy is a phrase coined by author and researcher Dr. Brené Brown. She’s spoken about this term in her books and interviews.

While not necessarily the same as cherophobia, a fear of happiness, foreboding joy can have many of the same sensations.

It can be described as that feeling you get when joy is followed quickly by thoughts of worry and dread, an inner dialogue of “but what if this happens,” or a sense of impending doom that something bad will happen to counteract the happiness you feel.

You’re still experiencing joy, but you’re also worried, convinced, and fearful that joy will leave you.

You may even fabricate worst-case scenarios in your head about post-joy possibilities, diminishing the joy you’re experiencing.

In her book “Daring Greatly,” Brown indicates that foreboding joy is one way you subconsciously try to protect yourself from vulnerability.

Foreboding joy says: If I don’t feel extremely happy, I won’t feel extremely disappointed.

Foreboding joy vs. cherophobia

Cherophobia is a type of specific phobia. Specific phobias are diagnosable mental health conditions characterized by impairing, irrational fear and anxiety.

Foreboding joy doesn’t have to be impairing or immobilizing. It may be more like a habit — that thing you do every time something good happens.

If foreboding joy stops you from seeking happiness, attending social events, or impairs important areas of function, it may be a candidate for a cherophobia diagnosis.

Consider reaching out to a mental health professional for evaluation and treatment if needed.

You might see examples of foreboding joy in different areas of life, including at school, home, or work.

At home

Joyful action: You just moved the new living room set in, and it looks fantastic.

Foreboding thought: “My pet is immediately going to tear into it, and then it will look as bad as the old set.”

At work

Joyful action: You just received recognition for a job well done on a project.

Foreboding thought: “What if I can’t live up to those expectations now? I’ll probably lose my job.”

At school

Joyful action: You passed that test with flying colors.

Foreboding thought: “None of that information will likely be on the final. I’m still going to be unprepared.”

Joy is an emotion associated with positive affect in psychology.

Positive affect is an umbrella term that describes several emotions, such as:

- joy

- enthusiasm

- optimism

- contentment

The National Institute of Health (NIH) links positive affect emotions such as joy to mental and physical health benefits.

Experiencing joy is also one of the ultimate mood boosts. A 2020 study suggests that it can involve many of the chemicals in the brain associated with happiness, such as dopamine, oxytocin, and serotonin.

But when you’re experiencing foreboding joy, it can feel like a little storm cloud raining on your party. You might experience a sense of fear, anxiety, or both.

Joy is often fleeting. The fear and anxiety that something bad will happen can disrupt our joy and lead to catastrophizing — a cognitive distortion that often comes with asking “what if” questions.

What if my alarm doesn’t go off? What if I mess up that presentation? What if I fail this test and don’t graduate?

We ask the “what ifs” to protect ourselves from fully giving into joy just in case the worst happens.

Catastrophizing can remove attention from the present moment to a hypothetical or imagined future, putting a damper on the situation and negating the benefits you might receive from joy.

When you’re used to foreboding joy, allowing yourself to experience true joy might not be easy. Here are some strategies you can try.

Rejoicing in everyday gratitude

In Brown’s works, she indicates that one of the most powerful ways to combat foreboding joy is to practice gratitude.

It doesn’t have to be in grand, obvious ways, either. Each night, you can take a moment and write down things you’re grateful for as a first step.

Practicing gratitude can help you acknowledge the positive things in your life and find reasons to feel joy, even in small ways.

Cultivating self-awareness

Knowing when you’re experiencing foreboding joy may help you stop those negative thoughts in their tracks.

You can recognize when you’re about to go down that path and choose another way.

Research from 2012 suggests that self-awareness can be cultivated through mindfulness — a practice that teaches how to experience thoughts and feelings in the moment without judgment or rumination.

Embracing the opportunity to build resilience

In “Daring Greatly,” Brown recommends focusing on turning moments of joy into opportunities to build resilience.

She explains that it’s natural for this to feel uncomfortable and scary, but every time you use joy as a tool against despair — rather than for it — you can cultivate hope and resilience.

When those feelings of “but what if this happens” appear, try to challenge yourself to push those thoughts aside.

Honoring the good, not the bad

Another form of gratitude recommendation Brown makes is to avoid honoring negative outcomes by ignoring your blessings.

If a friend lost a child to tragedy, that doesn’t mean you stop celebrating your child or apologizing for your child’s success.

Honoring your good circumstances, writes Brown, can be more of a tribute to someone else’s loss than focusing on the negative.

Foreboding joy may be your natural way of protecting yourself from vulnerability.

It’s a reaction based on the thought that you can’t be extremely disappointed if you don’t feel extremely happy.

While foreboding joy may evolve into cherophobia, it might never occur on a level that causes clinical impairment.

You don’t have to let foreboding joy disrupt the happy moments in your life.

Practicing gratitude, self-awareness, and cultivating resilience are all ways you can allow yourself to embrace joy without any “what ifs” attached.

Bren Brown on Shame and Vulnerability - T&P

Shame is an epidemic in our culture, according to researcher Bren Brown, who has devoted the last 5 years to the Interpersonal Communications Research Project. She managed to find out that the main problem underlying social interaction is vulnerability and the inability to accept our own imperfection - the only thing that makes us unique.

I spent the first ten years of my work among social workers: getting a degree in social work, interacting with social workers, making a career in this field. One day a new professor came to us and said: "Remember: everything that cannot be measured does not exist." I was very surprised. We are more accustomed to the fact that life is chaos. And most of the people around me tried to just love her like that, but I always wanted to streamline her - take all this diversity and arrange it in beautiful boxes. I got used to it like this: hit discomfort on the head, push it away and get some fives. And I found my way, decided to understand the most confusing of the topics, understand the cipher and show the rest how it works. I chose relationships between people. Because after ten years as a social worker, you begin to understand very well that we are all here for the sake of relationships, they are the purpose and meaning of our life. The ability to feel affection, the connection between people at the level of neuroscience - that's what we live for. And I decided to explore relationships. nine0005

And I decided to explore relationships. nine0005

“I hate vulnerability. And I thought this was a great chance to attack her with all my tools. I was going to analyze it, understand how it works, and outsmart it. I was going to spend a year on this. As a result, it turned into six years: thousands of stories, hundreds of interviews, some people sent me pages of their diaries "

simply the best, and here is one more thing in which you have room to grow.” And all that remains in your head is this last thing. My work looked the same. When I asked people about love, they talked about grief. When asked about affection, they talked about the most painful breakups. When asked about intimacy, I received stories about losses. Very quickly, after six weeks of research, I stumbled upon a nameless obstacle that affected everything. Stopping to figure out what it is, I realized that it was shame. And shame is easy to understand, shame is the fear of losing a relationship. We all fear we’re not good enough for relationships—not thin enough, rich enough, kind enough. This global feeling is absent only in those people who, in principle, are not able to build relationships. At the heart of shame is the vulnerability that comes when we realize that in order for a relationship to work, we must open up to people and allow ourselves to be seen for who we really are. nine0005

We all fear we’re not good enough for relationships—not thin enough, rich enough, kind enough. This global feeling is absent only in those people who, in principle, are not able to build relationships. At the heart of shame is the vulnerability that comes when we realize that in order for a relationship to work, we must open up to people and allow ourselves to be seen for who we really are. nine0005

I hate vulnerability. And I thought this was a great chance to attack her with all my tools. I was going to analyze it, understand how it works, and outsmart it. I was going to spend a year on this. As a result, it turned into six years: thousands of stories, hundreds of interviews, some people sent me pages of their diaries. I wrote a book about my theory, but something was wrong. If I divide all the people I interviewed into people who really feel needed - and in the end it all comes down to precisely this feeling - and those who constantly fight for this feeling, there was only one difference between them. It was that those who have a high degree of love and acceptance believe that they are worthy of love and acceptance. And that's all. They just believe they deserve it. That is, what separates us from love and understanding is the fear of not being loved and understood. Deciding that this needed to be dealt with in more detail, I began to conduct a study of this first group of people. nine0005

It was that those who have a high degree of love and acceptance believe that they are worthy of love and acceptance. And that's all. They just believe they deserve it. That is, what separates us from love and understanding is the fear of not being loved and understood. Deciding that this needed to be dealt with in more detail, I began to conduct a study of this first group of people. nine0005

I took a beautiful folder, carefully filed all the files there, and thought about what to name it. And the first thing that came to my mind was "Sincere". They were sincere people living with a sense of their own need. It turned out that their main common quality was courage (courage). And it is important that I use this particular word: it was formed from the Latin cor, heart. Originally, it meant "telling who you are from the bottom of your heart." Simply put, these people had the courage to be imperfect. They were merciful enough for other people because they were merciful to themselves - this is a necessary condition. And they had a relationship because they had the courage to give up the idea of what they should be in order to be what they are. Relationships cannot take place without this. nine0005

And they had a relationship because they had the courage to give up the idea of what they should be in order to be what they are. Relationships cannot take place without this. nine0005

These people had something else in common. Vulnerability. They believed that what makes them vulnerable makes them beautiful, and they accepted it. They, unlike people in the other half of the study, did not talk about vulnerability as something that makes them feel comfortable or, conversely, causes great inconvenience - they talked about its necessity. They talked about how to be the first to say "I love you", how to act when there are no guarantees of success, how to sit quietly and wait for the doctor's call after a serious examination. They were ready to invest in relationships that might not work out, moreover, they considered it a necessary condition. It turned out that vulnerability was not a weakness. It's emotional risk, insecurity, unpredictability, and energizes our lives every day. After researching this topic for more than ten years, I came to the conclusion that vulnerability, the ability to show oneself weak and be honest, is the most accurate tool for measuring our courage. nine0005 The Gifts of Imperfection is based on research that Bren Brown did in the 2000s. She came to the conclusion that it is our shortcomings that make us unique and allow other people to find something to love in us.

I then took it as a betrayal, it seemed to me that my research outwitted me. After all, the essence of the research process is to control and predict, to study a phenomenon for a clear purpose. And here I come to the conclusion that the conclusion of my research says that you need to accept vulnerability in yourself and stop controlling and predicting. Here I had a crisis. My therapist, of course, called it a spiritual awakening, but I assure you it was a real crisis. nine0005

I found a psychotherapist - this was the kind of psychotherapist that other psychotherapists go to, we sometimes need to do this to check the readings of the devices. I brought my folder with the study of happy people to the first meeting. I said, “I have a vulnerability problem. I know that vulnerability is the source of our fears and complexes, but it turns out that love, joy, creativity and understanding are also born from it. I need to deal with this somehow." And she, in general, nodded and said to me: “This is not good and not bad. It's just what it is." And I went to deal with it further. You know, there are people who can accept vulnerability and tenderness and continue to live with them. I am not like that. I hardly communicate with such people, so for me it was another year long street fight. In the end, I lost the battle with vulnerability, but I may have regained my own life. nine0005

I went back to research and looked at what decisions these happy sincere people make, what they do with vulnerability. Why do we have to fight it so hard? I posted a question on Facebook about what makes people feel vulnerable, and got 150 responses in an hour. Asking your husband to take care of you when you're sick, being proactive about sex, firing an employee, hiring an employee, asking you out on a date, getting a diagnosis from a doctor—these situations were all on the list. We live in a vulnerable world. We deal with it by simply constantly suppressing our vulnerability. The problem is that feelings cannot be suppressed selectively. You can’t choose - here I have vulnerability, fear, pain, I don’t need all this, I won’t feel it. When we suppress all these feelings, with them we suppress gratitude, happiness and joy, nothing can be done about it. And then we feel miserable, and even more vulnerable, and we try to find meaning in life, and we go to a bar where we order two bottles of beer and cake. nine0005

“Shame is an epidemic in our culture, and in order to recover from it and find our way back to each other, we need to understand how it affects us and what makes us do. Shame needs three components to grow steadily and unhindered: secrecy, silence, and condemnation.”

Here are a few things I think we should think about. The first is that we make certain out of indeterminate things. Religion has gone from sacrament and faith to certainty. “I am right, you are not. Shut up". And there is. Unambiguity. The more frightened we are, the more vulnerable we are, and this only makes us more frightened. This is what current politics looks like. There are no more discussions, no discussions, only accusations. Blaming is a way to vent pain and discomfort. Second, we are constantly trying to improve our lives. But it doesn't work like that - basically we just transfer fat from our thighs to our cheeks. And I really hope that people in a hundred years will look at this and be very surprised. Third, we are fiercely protective of our children. Let's talk about how we treat our children. They come into this world programmed to fight. And our task is not to take them in our arms, dress them beautifully and make sure that in their ideal life they play tennis and go to all possible circles. No. We must look them in the eye and say, “You are not perfect. You came here imperfect and created to fight it all your life, but you are worthy of love and care.” Show me one generation of kids who have been raised this way, and I'm sure we'll be surprised how many of today's problems just disappear from the face of the earth.

nine0005

We pretend that our actions do not affect the people around us. We do this in our personal lives and at work. When we take out a loan, when a deal falls through, when oil spills into the sea, we pretend that we have nothing to do with it. But this is not so. When things like this happen, I want to say to corporations: “Guys, we are not living for the first time. We are used to a lot. We just want you to stop pretending and say, “Forgive us. We'll fix everything."

Shame is an epidemic in our culture, and in order to recover from it and find our way back to each other, we need to understand how it affects us and what makes us do. Shame needs three components to grow steadily and unhindered: secrecy, silence, and condemnation. The antidote to shame is empathy. When we suffer, the strongest people around us must have the courage to tell us: I am too. If we want to find a way to each other, then this way is vulnerability. And it's much easier to stay away from the arena all your life, thinking that you will go there when you become bulletproof and the best. The thing is, it will never happen. And even if you get as close as possible to the ideal, it will still turn out that when you enter this arena, people do not want to fight with you. They want to look into your eyes and see your sympathy. nine0005

strength of vulnerability, criticism, courage, gifts of imperfection

strength of vulnerability. This topic was raised to the world level by Brené Brown, her speech "The Power of Vulnerability" in the TOP TED for many years, more than 34 million views. Brené Brown explores vulnerability, courage, and human relationships—our ability to empathize, accept, love. A performance that you would like to recommend to others. Personally, I've watched it a dozen times already.

Force of vulnerability

Attitude towards criticism: it's not the critic that changes the world

After some googling, I found a wonderful translation of subtitles, thanks to Lenochka.

(you can turn on subtitles with the CC button, select the language with the settings button next to it)

And in this speech, Brené Brown quotes US President Theodore Roosevelt, part of his famous speech at the Sorbonne (1910), which is often called "the speech about the man in the arena" , for Brené Brown, this quote hit the bull's-eye. Read for yourself - insight awaits! nine0005

“It is not the critic who changes the world,

not the one who points out in time,

what a person in the arena is doing wrong

or what he could have done differently.We praise the one who is in the arena

in blood, sweat and dust. We admire those

who, at best, know the taste of luck,

, and at worst, know that they have put in all their strength and swung at the great.

To quote Brené Brown herself:

“After reading this piece, I closed my laptop and realized three things.

First : I've been researching a vulnerability for 12 years, and this quote contains everything that I managed to find out during this time. Vulnerability is not in victory or defeat. It is in the courage to do important things and be noticed.

Second : this is how I want to live! I want to create. I want to be an innovator. I am ready to be visible in life and at work. and if you decide to be noticeable, one thing is for sure: you will definitely fly. The audience will kick your ass! Without a doubt. This is the only thing you can be sure of. Entering the arena, deciding to spend time on it, and especially as a representative of the creative profession, get ready: you will get your ass kicked. Keep this in mind when making important decisions. If courage is among your values, these are logical consequences.

Third : it has become much easier for me to live with the following attitude towards criticism - if you have not entered the arena yourself, if you are not ready to live noticeably, your comments and advice are completely uninteresting to me. Alas. nine0005

I work at a university, debate is my everything. Advice from colleagues in the spirit: “You forgot to take into account this book”, “I should have studied this one”, “I would have formulated it differently” - this is useful.

But if you settled down in a gallery, you don't decide on anything yourself, but you tell me how and what should be improved, your words are simply worth nothing. »

* My side note

And if you look at perfectionism, we have another arena - inside - where our inner creator fights the inner critic. And the creator regularly "arrives". nine0047 And if you look at the history of the development of man and technology, it is quite easy to realize that people who change the world are not critics. So in the inner world, this is worth focusing on!

Continue to quote Brené Brown:

“I want to talk about the moment just before entering the arena. This is where we sweat, agree?

From here you can see the lights of the arena, here I am scared, I doubt myself, there is no certainty.

What should a man consumed by fear do? How to defend yourself before entering the arena, where merciless spectators are waiting? You can wear armor. The surest way! Knights and heavy metal armor immediately come to mind. nine0005

But armor is horribly heavy! You can't see white light from under the helmet. This, of course, is protection, but under strong armor it is easy to lose contact with yourself. With armor, you separate yourself from everything that you love, that supports you, that is important to you.

Vulnerability, of course, is accompanied by doubts, uncertainty, shame… But something else is born out of vulnerability.

Love, intimacy, joy, trust, empathy, creativity and novelty - you can't create without being vulnerable. If you're on the creative path, you'll need to walk through this hall every day, up the stairs, and out naked. defenseless. Yourself. nine0038

Then the audience will see you and what you are doing, not the armor.