Axis i mental disorders

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Signs Of Autism

- Special Learning

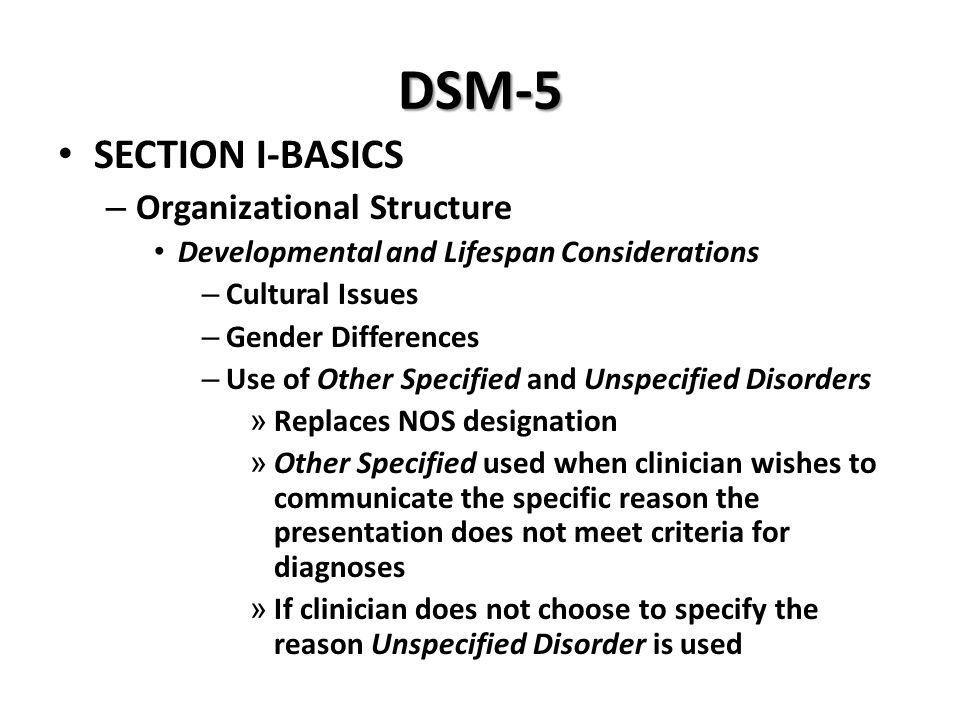

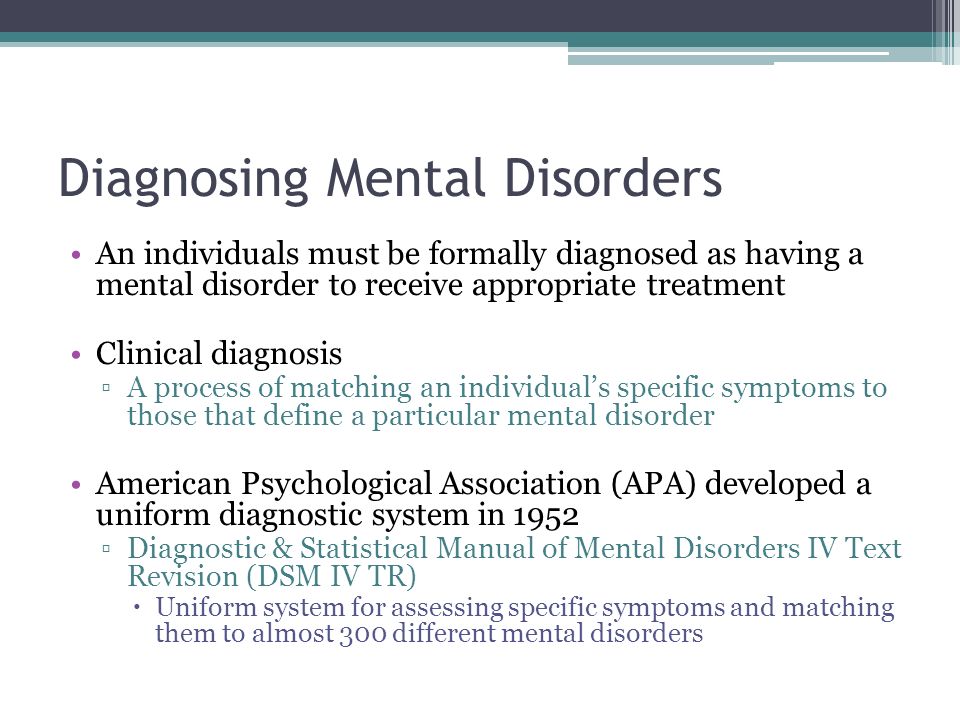

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is the standard classification of mental disorders used by mental health professionals in the United States, as stated by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). There have been several editions of the DSM, the latest of which is the fourth edition.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) was published by the APA in 1994. It is designed to be a guide for health practitioners in America regarding diagnosing and classifying mental disorders. It is also a systematic method of communicating by providing universally recognized medical terms, conditions, and definitions of mental disorders and acceptable interventions to these disorders.

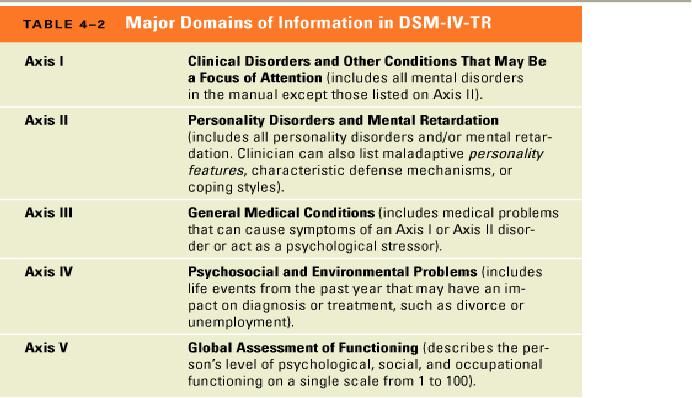

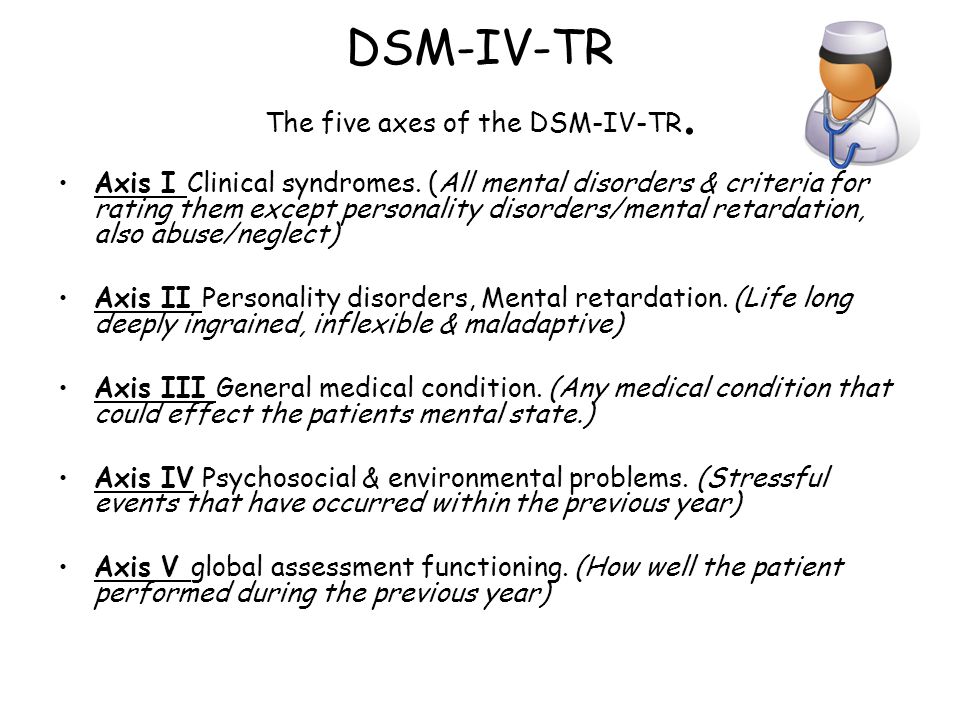

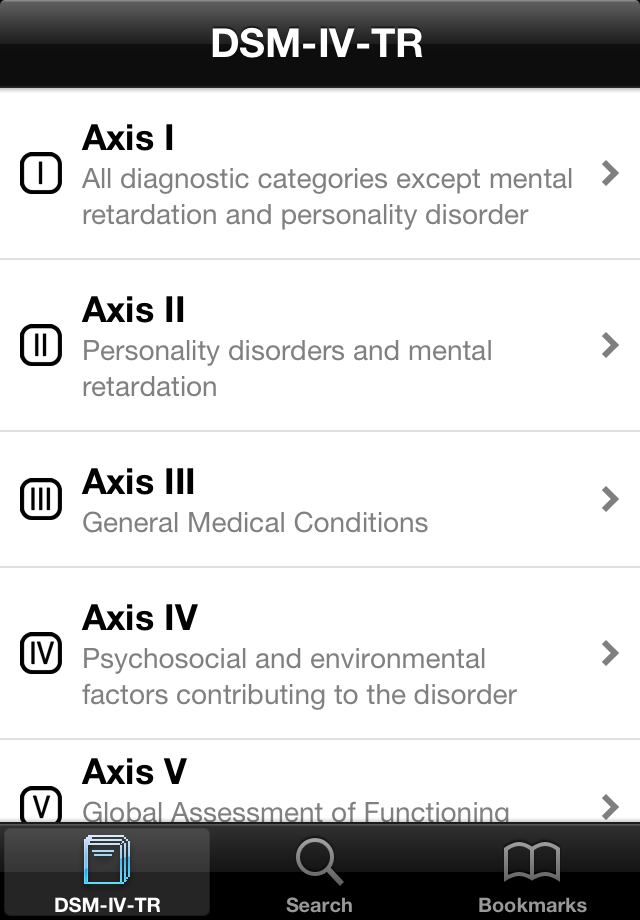

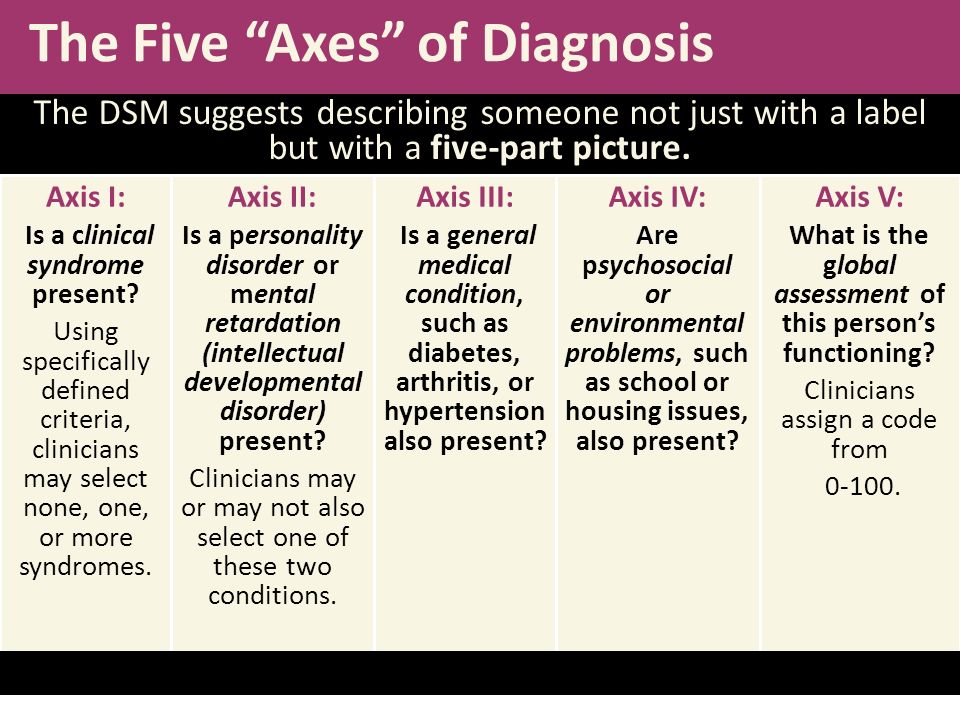

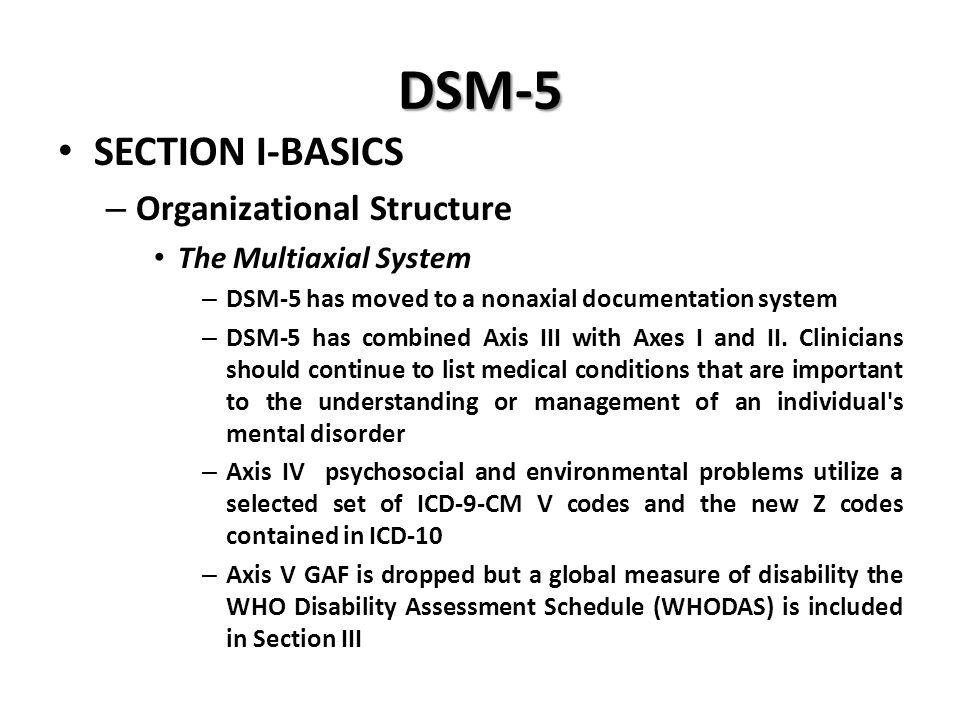

The DSM-IV uses an axial system that allows healthcare providers to better gauge how mental illness shapes a patient’s overall health. It uses 5 different axes:

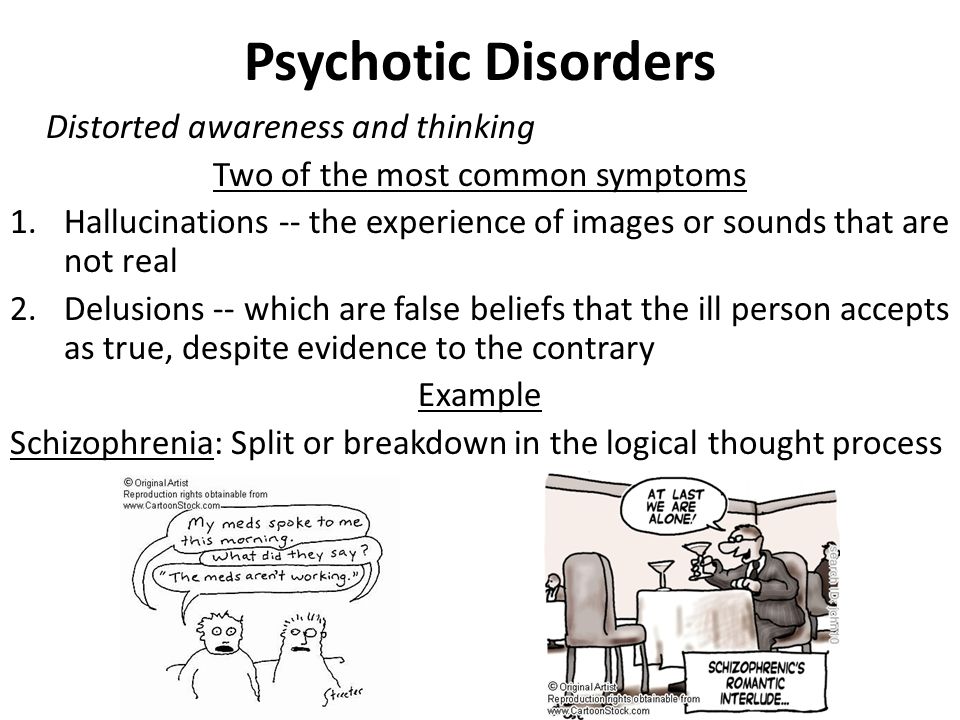

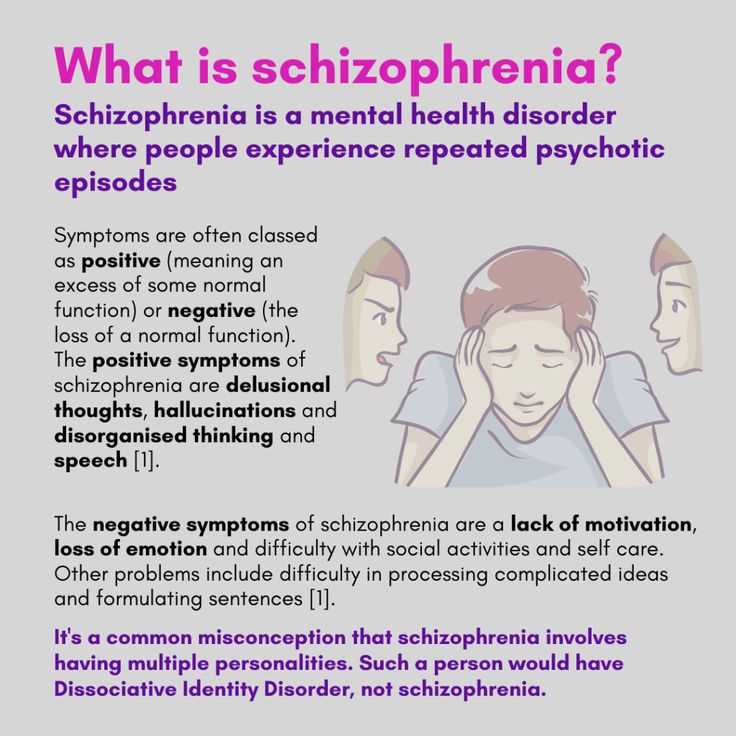

- Axis I – is comprised of disorders that currently exist like schizophrenia and mood/anxiety/eating/sleep disorders.

- Axis II – comprises personality disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults and developmental problems like mental retardation in children and adolescents.

- Axis III – is defined by the different medications that alleviate mental disorders.

- Axis IV – involves rating psycho-social stressors that may affect an individual.

- Axis V – includes a numerical scale that rates a person’s level of functioning.

To diagnose autism, it requires that at least six developmental and behavioral characteristics listed in the DSM-IV are present, evident before your child years 3 years of age and that there is assurance that no other health conditions that have similar characteristics are present.

A person is diagnosed with autism when the following are present, as stated by the APA:

- A total of 6 characteristics (or more) items from categories (A), (B), and (C),

- At least 2 from category (A)

- and one each from (B) and (C)

- Accordance categories II and III

Here is a copy of the characteristics listed in the DSM-IV criteria for autism diagnosis:

- A.

Qualitative impairment in social interaction, as manifested by at least two of the following:

Qualitative impairment in social interaction, as manifested by at least two of the following:

- Marked impairments in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviors such as eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression, body posture, and gestures to regulate social interaction

- Failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level

- A lack of spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or achievements with other people, (e.g., by a lack of showing, bringing, or pointing out objects of interest to other people)

- Lack of social or emotional reciprocity ( note: in the description, it gives the following as examples: not actively participating in simple social play or games, preferring solitary activities, or involving others in activities only as tools or “mechanical” aids )

- Qualitative impairments in communication as manifested by at least one of the following:

- Restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities, as manifested by at least two of the following:

- Encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus

- Apparently inflexible adherence to specific, nonfunctional routines or rituals

- Stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms (e.

g hand or finger flapping or twisting, or complex whole-body movements)

g hand or finger flapping or twisting, or complex whole-body movements) - Persistent preoccupation with parts of objects

- Delays or abnormal functioning in at least one of the following areas, with onset prior to age 3 years:

- social interaction

- language as used in social communication

- symbolic or imaginative play

III. The disturbance is not better accounted for by Rett’s Disorder or Childhood Disintegrative Disorder.

References:

Autism Watch. Autism-watch.org: The Medical/Psychiatric Diagnosis of Autism: The DSM-IV Criteria. Retrieved March 21, 2011, from autism-watch.org/general/dsm.shtml

American Psychiatric Association. psych.org: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. Retrieved March 21, 2011, from psych.org/mainmenu/research/dsmiv.aspx

Copyright © by Special Learning Inc. All right reserved.

No part of this article may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, contact Special Learning Inc., at: [email protected]

For information, contact Special Learning Inc., at: [email protected]

Share:

Psychiatric Skills for Non-Psych Nurses

Since 1952 with the appearance of the first American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, clinicians have had access to an official manual containing symptomatic descriptions of psychiatric diagnostic categories. Prior to this original edition, there was little in the way of organized or uniform diagnosis of psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry may be one of the more subjective areas of medical science. Both patient presentation and interpretation of presenting symptoms through the individual clinicians’ theoretical orientation have been factors which may account for variation in diagnosis of similar symptom clusters. The DSM I may be seen as an effort by the Americana Psychiatric Association to assist clinicians to view psychiatric symptom clusters more congruently. Also, psychiatry is a field where clinicians other than MD’s apply diagnostic labels, Using a nationally approved and disseminated glossary of diagnostic categories allow allied mental health professionals such as psychologists, social workers, nurses and MFCC’s the same access to psychiatric descriptions and diagnostic nomenclature.

Also, psychiatry is a field where clinicians other than MD’s apply diagnostic labels, Using a nationally approved and disseminated glossary of diagnostic categories allow allied mental health professionals such as psychologists, social workers, nurses and MFCC’s the same access to psychiatric descriptions and diagnostic nomenclature.

In 1968 the second edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-II) appeared followed by the DSM-III in 1974. Continual review and updating of the SAM reflects the dynamic nature of psychiatry and the evolving knowledge base revealed through on-going research.

Currently in use since 1987 is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised (DSM-IIIR). The large, multidisciplinary work group who gathered to revise the DSM-III was charged with the task of increasing the sensitivity in certain diagnostic categories including sleep disorders, anxiety disorders, childhood psychiatric disorders and psychosis. Need for revision of diagnostic categories was based on research when well-conducted scientific studies were available; clinical experience, however, was a significant factor in diagnostic revisions. The APA recognizes that the DSM must support validity and reliability of diagnosis and that diagnosis is the foundation on which treatment and management decisions are made. Additionally, the DSM is used for educating a variety of health professionals and as a reference in many aspects of research; it must be accepted across a wide range of theoretical viewpoints and maintain compatibility with ICD-9-CM codes.

Need for revision of diagnostic categories was based on research when well-conducted scientific studies were available; clinical experience, however, was a significant factor in diagnostic revisions. The APA recognizes that the DSM must support validity and reliability of diagnosis and that diagnosis is the foundation on which treatment and management decisions are made. Additionally, the DSM is used for educating a variety of health professionals and as a reference in many aspects of research; it must be accepted across a wide range of theoretical viewpoints and maintain compatibility with ICD-9-CM codes.

THE AXIS SYSTEM

The most current edition, the DSM-IIIR emphasizes that the text classifies mental disorders not people. A mental disorder is described as a “clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndrome or pattern that occurs in a person and that is associated with present distress or disability or with a significantly increased risk of suffering death, pain, disability, or an important loss of freedom” (DSM-IIIR p. XXII). The DSM-IIIR focuses on describing the clinical features of psychiatric disorders and provides guidelines including specific criteria for establishing diagnosis. A multiaxial system is utilized in DSM-IIIR which incorporates mental disorders, physical illnesses or conditions, psychosocial stressors and global level of overall functioning. This system reflects a biopsychosocial assessment focus. The 5 axis of the system are:

XXII). The DSM-IIIR focuses on describing the clinical features of psychiatric disorders and provides guidelines including specific criteria for establishing diagnosis. A multiaxial system is utilized in DSM-IIIR which incorporates mental disorders, physical illnesses or conditions, psychosocial stressors and global level of overall functioning. This system reflects a biopsychosocial assessment focus. The 5 axis of the system are:

Axis I Clinical Psychiatric Syndromes

Axis II Developmental Disorders

Axis III Physical Disorders and Conditions

Axis IV Severity of Psychosocial Stressors

Axis V Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)

Multiple diagnoses are acceptable on Axis I and II when this accurately reflects an individual’s conditions. Just as a person may have several medical diagnoses, it is possible to have co-existing mental disorders.

Just as a person may have several medical diagnoses, it is possible to have co-existing mental disorders.

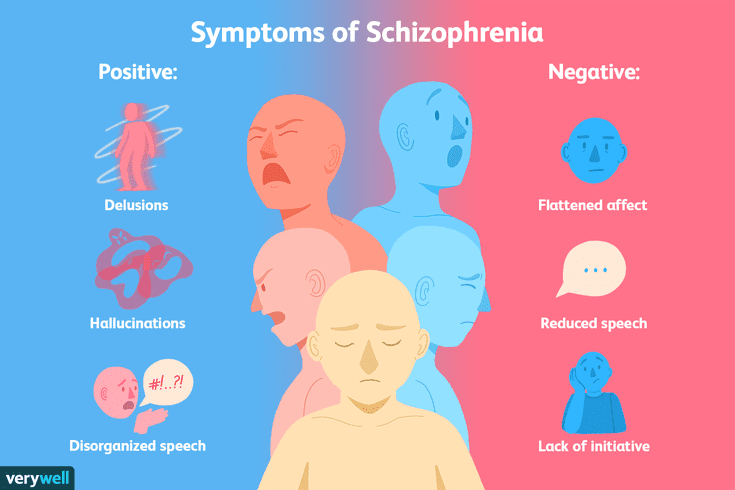

Axis I disorders are clinical syndromes. Some examples of these include Major Depression, Adjustment Disorder, Schizophrenia or Alcohol Dependence. Obviously an individual could conceivably have two or even more of these diagnoses concurrently on Axis I.

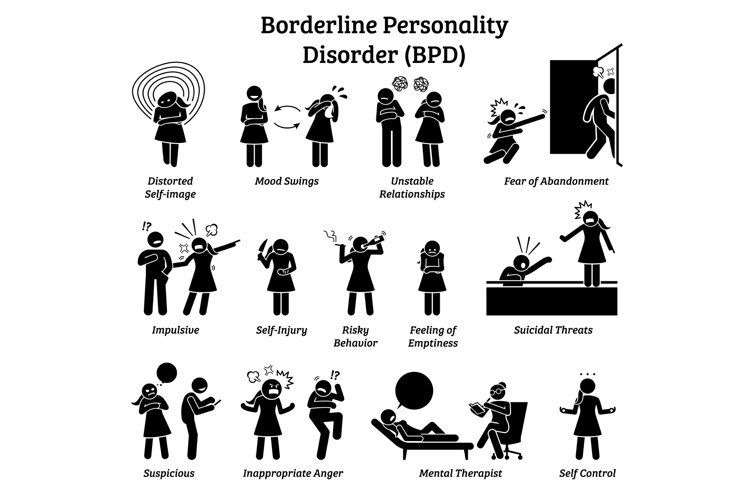

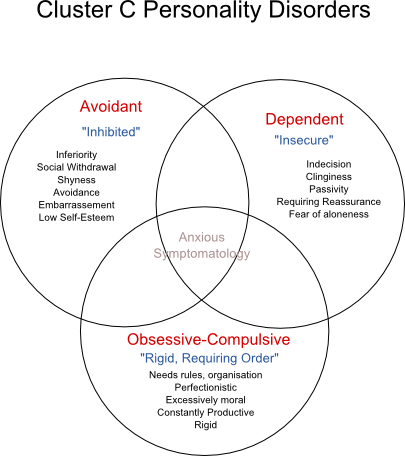

Axis II is used to list Developmental Disorders and Personality Disorders. Both of these are generally disorders which begin in early life and continue through adulthood. Developmental disorders involve a delay or a failure to progress in skill acquisition of a motor, social, cognitive or language nature. The term personality disorder is used to describe a constellation of rigid, maladaptive personality traits which cause the individual significant distress, relationship difficulties and functional impairment. Personality disorders are often recognized during adolescence and persist through adulthood.

Examples of Developmental Disorders which would appear on Axis II include:

Autistic Disorder, Developmental Expressive Writing Disorders, or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

Personality Disorders which would also be listed on Axis II are Antisocial Personality Disorder, Histrionic Personality Disorder or Narcissistic Personality Disorder, to name a few.

On Axis III the clinician lists any physical disorders which are known to be current or, if pertinent, by history.

Axis IV is the severity of psychosocial stressors scale. Here the clinician codes the life stressors of the past year which may have contributed to the clients current diagnosis on a 1 – 6 scale – one being none through 6 being catastrophic. Clinical judgment is exercised in rating the stress an “average” individual in similar circumstances would experience from the psychosocial stressors in the clients’ life over the preceding year.

The Global Assessment of Functioning scale allows the assessing clinician to indicate an overall impression of the client’s level of functioning currently and within the past year. The numerical value given from 90 – 1 reflects the range of optimal mental health ---- severe illness. Psychological, social and occupational function are all assessed and integrated into a numerical GAF expressed as:

Axis V: Current GAF Highest GAF, past year

The highest GAF, past year has prognostic value as it indicated the level of functioning available to the client prior to the onset of acute psychiatric illness and, for most individuals, indicates the level of function they can expect to resume after resolution of their current difficulty.

In summary, a complete multiaxial assessment based on the DSM-IIIR will result in a 5 axis diagnosis including:

DIAGNOSIS |

EXAMPLE |

Axis I Axis II

Axis III (Medical) Axis IV

Axis V |

Major Depression

Narcissistic Personality

Status Post CVA

Current GAF: 35 |

Most of the DSMIII-R is dedicated to describing psychiatric syndromes and developmental disorders. Consistent information is provided for each diagnostic label. Information includes essential features; associated features; typical age at onset; typical course of the illness; typical impairment; complications; predisposing factors; prevalence in the general population and sex ratio; familial pattern; and differential diagnosis.

Consistent information is provided for each diagnostic label. Information includes essential features; associated features; typical age at onset; typical course of the illness; typical impairment; complications; predisposing factors; prevalence in the general population and sex ratio; familial pattern; and differential diagnosis.

COMMON PSYCHIATRIC DIAGNOSIS

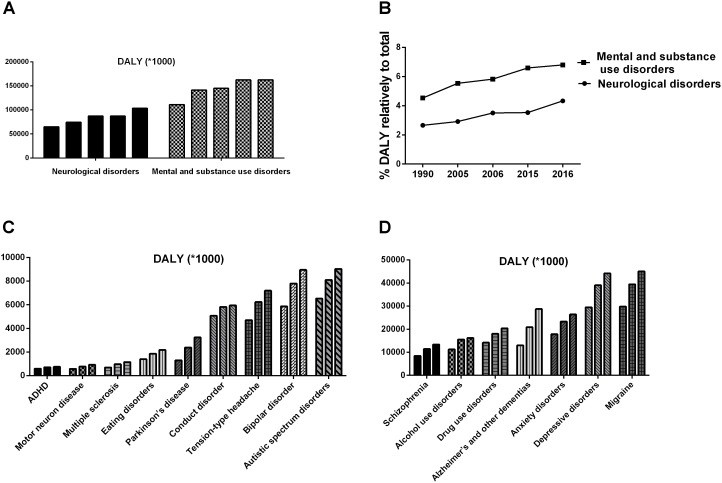

Certain psychiatric diagnoses occur more frequently in the general population than others. Diagnoses that are prevalent in our culture include:

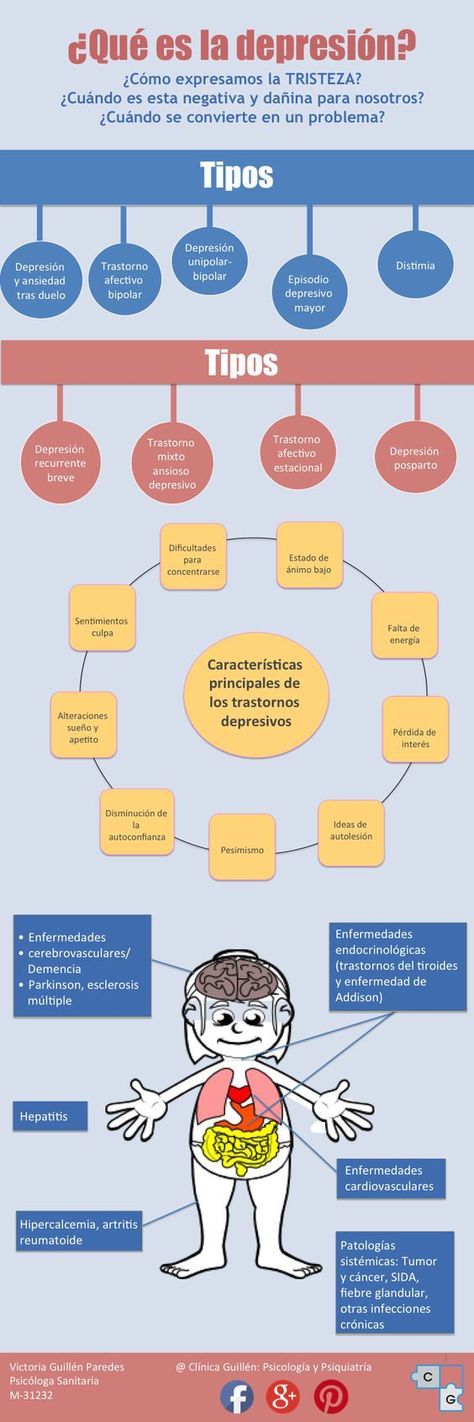

Axis I Depression Disorder 3 – 9%

(Major depression)

Schizophrenia .2 – 1%

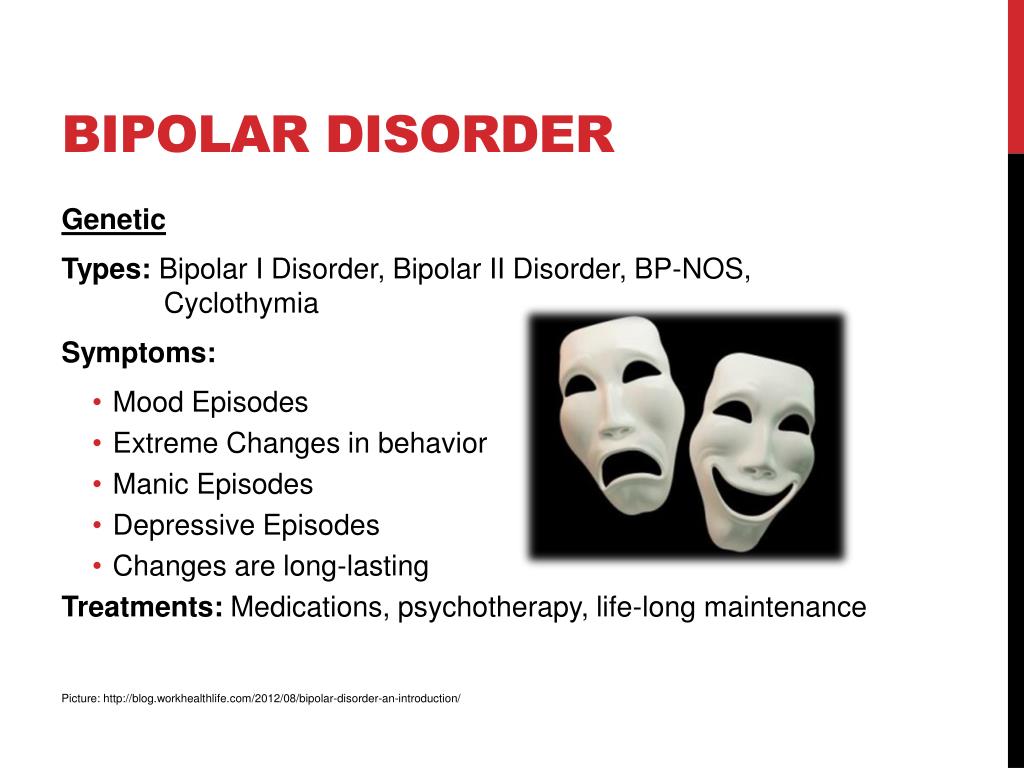

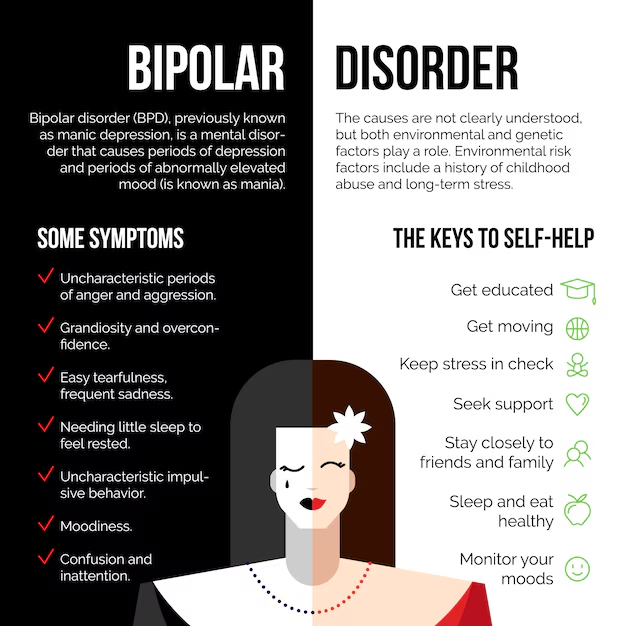

Bipolar Disorder .4 – 1.2%

Alcohol Abuse or

Dependence 13%

Adjustment Disorders

Axis II Personality Disorders of all types

As the stigma associated with mental illness diminishes and general understanding of psychiatric problems increases, patients with psychiatric diagnosis utilizing psychiatric medications will be seen more frequently in the medical hospital, the physician’s office, medical clinics and other health care settings. Nurses can frequently enhance patient care by assuring integration of care.

Nurses can frequently enhance patient care by assuring integration of care.

This section will conclude with two case examples of patients with current acute medical problems who also have secondary psychiatric diagnosis which require on-going attention.

CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS

EXAMPLE 1

Mrs. Drew is a 47 year old married woman who is admitted to 3 North post-op after orthopedic surgery. She was injured in a MVA and brought to surgery after assessment in the ERD. Her physical condition is stable – she is awake and alert but is quiet, rather withdrawn, has little variance in facial expression or tone of voice, and her eye contact with you is minimal. When you interact with her she answers questions rather abruptly and makes no attempt to converse or be social. You notice that you feel somewhat uncomfortable or anxious around her. Later in the shift, Mrs. Drew’s husband comes in to visit. You observe their interaction and

notice that the quality of Mrs. Drew’s interaction with her husband is quite similar to her interactional style with you. As Mr. Drew leaves, you ask if you can speak with him for a moment and question him about his wife’s interpersonal style and subdued affect. In attempting to thoroughly assess your patient’s emotional state you might ask: “Is this her usual personality style? Or “Is Mrs. Drew subdued as a consequence of the physical and emotional trauma associated with her accident?” or “Could her behavior be part of her reaction to pain medication?” These are some of the differentiating questions that occur to you. Mr. Drew is receptive to your inquiry and states, “My wife is schizophrenic. She was diagnosed many years ago. This information needs to be in her chart as she must be maintained on anti-psychotic medication. As a matter of fact, I plan to notify her psychiatrist of her hospitalization tomorrow and hope she can visit my wife soon.” You request the name and phone number of Mrs.

Drew’s interaction with her husband is quite similar to her interactional style with you. As Mr. Drew leaves, you ask if you can speak with him for a moment and question him about his wife’s interpersonal style and subdued affect. In attempting to thoroughly assess your patient’s emotional state you might ask: “Is this her usual personality style? Or “Is Mrs. Drew subdued as a consequence of the physical and emotional trauma associated with her accident?” or “Could her behavior be part of her reaction to pain medication?” These are some of the differentiating questions that occur to you. Mr. Drew is receptive to your inquiry and states, “My wife is schizophrenic. She was diagnosed many years ago. This information needs to be in her chart as she must be maintained on anti-psychotic medication. As a matter of fact, I plan to notify her psychiatrist of her hospitalization tomorrow and hope she can visit my wife soon.” You request the name and phone number of Mrs. Drew’s psychiatrist as well as the names and dosages of her psychiatric medication. You also ask Mr. Drew for any suggestions he has which could assist the nursing staff and Mrs. Drew cope with the stress of her hospitalization. Then you report the information you have gathered to the nurse manager and Mrs. Drew’s primary care physician. You may suggest that Mr.. Drew contact Mrs. Drew’s primary care physician with this information as well.

Drew’s psychiatrist as well as the names and dosages of her psychiatric medication. You also ask Mr. Drew for any suggestions he has which could assist the nursing staff and Mrs. Drew cope with the stress of her hospitalization. Then you report the information you have gathered to the nurse manager and Mrs. Drew’s primary care physician. You may suggest that Mr.. Drew contact Mrs. Drew’s primary care physician with this information as well.

EXAMPLE 2

Mr. Johns, a 52 year old male is admitted to your med-surg unit after several days in CCU. His cardiac condition is stable and in reporting his treatment, the CCU nurse notes that he is on 20 mg of Prozac each morning. You ask why he’s receiving Prozac and are told he’s been on it for 5 months since being hospitalized for major depression. In interviewing Mr. Johns you inquire about his depression. He relates he was hospitalized at age 35 for depression after losing a young son in an accident. At that time, he was in the hospital for 5 ½ weeks after a suicide attempt. He took 2 different anti-depressants as the first one was ineffective. More recently, Mr. Johns’ became depressed when he believed his job to be threatened by company downsizing and after the marriage of his youngest daughter who moved to Hawaii. Although Mr., Johns was not suicidal 5 months ago, he experienced early morning awakening; obsessive negative thoughts related to his fears of job loss; anorexia; lack of motivation and slowing of his speech. His wife insisted he seek psychiatric care after he refused to get out of bed for an entire weekend. He was hospitalized for 5 days. Prozac was begun immediately and he’s continued at 20 mgs every AM. He is willing to discuss how his current illness has affected his depression, denies any suicidal ideas and agrees when you suggest that his psychiatrist should be notified of his current health problems. Mr. Johns thanks you for your interest and understanding.

At that time, he was in the hospital for 5 ½ weeks after a suicide attempt. He took 2 different anti-depressants as the first one was ineffective. More recently, Mr. Johns’ became depressed when he believed his job to be threatened by company downsizing and after the marriage of his youngest daughter who moved to Hawaii. Although Mr., Johns was not suicidal 5 months ago, he experienced early morning awakening; obsessive negative thoughts related to his fears of job loss; anorexia; lack of motivation and slowing of his speech. His wife insisted he seek psychiatric care after he refused to get out of bed for an entire weekend. He was hospitalized for 5 days. Prozac was begun immediately and he’s continued at 20 mgs every AM. He is willing to discuss how his current illness has affected his depression, denies any suicidal ideas and agrees when you suggest that his psychiatrist should be notified of his current health problems. Mr. Johns thanks you for your interest and understanding. He feels somewhat embarrassed by his psychiatric illness but is relieved to have his “cards on the table”.

He feels somewhat embarrassed by his psychiatric illness but is relieved to have his “cards on the table”.

In both of these situations, adverse consequences could result from the discontinuation of psychiatric medications or the avoidance of the psychosocial component of the patients total health picture. Each patient’s medical condition, length of stay, and response to treatment could be negatively impacted if the psychiatric history were ignored or undiscovered.

Next: ASSESSMENT SKILLS IN A CRISIS SITUATION

Methodological issues of diagnosing mental disorders and modern programs for training specialists in psychiatry

Methodological issues of diagnosing mental disorders and modern programs for training specialists in psychiatry

A. E. Bobrov

Moscow Research Institute of Psychiatry

Published: Social and clinical psychiatry. 2014. - V.24. - No. 2. - P.50-54.

Bobrov Aleksey Evgenievich, Doctor of Medicine, professor, doctor of the highest category

The participation of Russian psychiatrists in the adaptation and implementation of new international classifications of mental disorders should be carried out taking into account the experience of implementing ICD-10 in our country. Many of the omissions, oversights and mistakes that were made in the 1990s still weigh heavily on Russian psychiatry and the mental health training system [2, 14, 20]. Understanding these problems will help us move more adequately and balanced to a new stage in the development of psychiatry, which will be directly or indirectly reflected in new classifications.

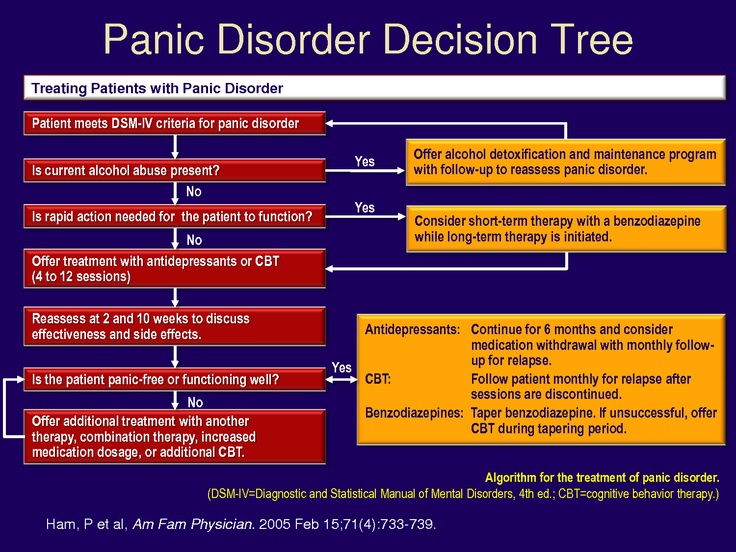

The difficulties that we encountered while working with the ICD-10 did not immediately become apparent. Initially, it seemed that they were associated with the emergence of new and unusual terminology, as well as with the difficulties of translation. Such terms, previously unused in our country, as mild cognitive disorder, schizotypal disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, adjustment disorder, somatoform disorders and a number of others have appeared. In essence, many key categories of psychopathology began to be designated in a new way. Among them are neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders, behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disorders and physical factors, disorders of mature personality and behavior in adults. All child psychiatry and mental retardation, not to mention mental and behavioral disorders due to substance use, have been fundamentally reformulated. Difficulties also arose in connection with the controversial translation of such terms as "Somatization disorder", "Histrionic personality disorder", "Pathological gambling" and others, when the rigor of the translation was sacrificed to "usual" clinical constructions [3, 12, 14, 16, 19, 21].

Such terms, previously unused in our country, as mild cognitive disorder, schizotypal disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, adjustment disorder, somatoform disorders and a number of others have appeared. In essence, many key categories of psychopathology began to be designated in a new way. Among them are neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders, behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disorders and physical factors, disorders of mature personality and behavior in adults. All child psychiatry and mental retardation, not to mention mental and behavioral disorders due to substance use, have been fundamentally reformulated. Difficulties also arose in connection with the controversial translation of such terms as "Somatization disorder", "Histrionic personality disorder", "Pathological gambling" and others, when the rigor of the translation was sacrificed to "usual" clinical constructions [3, 12, 14, 16, 19, 21].

Nevertheless, at the beginning it seemed that over time our specialists would get used to the new terminology, and everything would fall into place. However, the formal introduction of these terminological innovations turned out to be unproductive. Doctors were reluctant to switch to new concepts, because they did not understand them. It soon became obvious that behind the new terminology in a hidden, implicit form, there are clinical and theoretical concepts unfamiliar to Russian psychiatrists. This, first of all, was expressed in discussions about the understanding of schizophrenia and affective disorders. To an even greater extent, the field of borderline psychiatry, including neurosis, reactive states, and personality pathology, has undergone a radical conceptual revision [4, 5, 7, 15].

However, the formal introduction of these terminological innovations turned out to be unproductive. Doctors were reluctant to switch to new concepts, because they did not understand them. It soon became obvious that behind the new terminology in a hidden, implicit form, there are clinical and theoretical concepts unfamiliar to Russian psychiatrists. This, first of all, was expressed in discussions about the understanding of schizophrenia and affective disorders. To an even greater extent, the field of borderline psychiatry, including neurosis, reactive states, and personality pathology, has undergone a radical conceptual revision [4, 5, 7, 15].

All these conceptual shifts were not properly comprehended by our scientific and pedagogical community due to well-known objective and subjective reasons. As a result, many professionals have formed an ambivalent attitude towards the new classification. On the one hand, it was said that the ICD-10 is just a tool for collecting statistical information. However, on the other hand, under the influence of diagnostic practice focused on the ICD-10, the methodological foundations of domestic psychiatry began to undergo a significant revision. Naturally, this revision was significantly accelerated under the influence of the inclusion of domestic psychiatrists in international psychiatric associations and research (primarily pharmacological). All this contributed to the growth of internal contradictions, which, first of all, manifested themselves in the curricula on psychiatry of universities and postgraduate training. However, the same problems revealed themselves in the field of reforming the psychiatric service, and in the "disputes" about the effectiveness of psychotherapy, and in approaches to the use of new psychopharmacological agents, and in the fight against drugs and gambling.

However, on the other hand, under the influence of diagnostic practice focused on the ICD-10, the methodological foundations of domestic psychiatry began to undergo a significant revision. Naturally, this revision was significantly accelerated under the influence of the inclusion of domestic psychiatrists in international psychiatric associations and research (primarily pharmacological). All this contributed to the growth of internal contradictions, which, first of all, manifested themselves in the curricula on psychiatry of universities and postgraduate training. However, the same problems revealed themselves in the field of reforming the psychiatric service, and in the "disputes" about the effectiveness of psychotherapy, and in approaches to the use of new psychopharmacological agents, and in the fight against drugs and gambling.

This duality and uneven perception of the new scientific reality began to give rise to utopian demands to "return to the ICD-9" or create their own "national" classification of mental disorders. The need to "retrain" in a new way for a number of domestic teachers turned out to be unacceptable for psychological or status reasons. All this was exacerbated by the language "barrier", the low availability of modern scientific information, as well as the "leakage" of personnel and the underdevelopment of scientific technologies [10].

The need to "retrain" in a new way for a number of domestic teachers turned out to be unacceptable for psychological or status reasons. All this was exacerbated by the language "barrier", the low availability of modern scientific information, as well as the "leakage" of personnel and the underdevelopment of scientific technologies [10].

The rejection of the ICD-10 by a number of domestic psychiatrists was also associated with the internal inconsistency of the classification itself. Its text directly declares the “atheoretical” and purely applied nature of diagnostic categories, while, in fact, ICD-10 introduced a number of new theoretical principles into psychopathology [18, 13, 20]. This led to the emergence of a specific methodological "barrier" in the development of this classification.

The most important of the new principles of constructing a classification was the principle of operationality, according to which concepts can be defined only through a set of reproducible experimental and measuring operations. The consequence of this methodological turn was that the diagnosis of mental disorders began to be made not on the basis of the clinical experience of a doctor and intuitive prediction of the dynamics of the disease, but on the basis of registering a limited number of relatively independent standard signs. Moreover, these features should be described in a uniform way, and their application should be carried out in accordance with a predetermined algorithmic procedure.

The consequence of this methodological turn was that the diagnosis of mental disorders began to be made not on the basis of the clinical experience of a doctor and intuitive prediction of the dynamics of the disease, but on the basis of registering a limited number of relatively independent standard signs. Moreover, these features should be described in a uniform way, and their application should be carried out in accordance with a predetermined algorithmic procedure.

In addition, the denial of such categories traditional for domestic psychiatry as “neurosis”, “psychosis” and “psychopathy” led to a fundamentally new understanding of the relationship between psychopathological manifestations and social criteria of mental solvency and capacity. Instead of a direct dependence of the diagnosis on psychopathological characteristics and prognosis, the ICD-10 introduced the concept of impaired social functioning as the most important criterion for a mental disorder [9, eleven]. As a result, the transition from traditional biomedical views (and illusions) to the socio-psychological paradigm became more distinct [6]. The concept of nosology as "the unity of the clinic, dynamics and etiopathogenesis" was replaced by nosography as a predominantly taxonomic description of conditional psychopathological units, which began to be denoted by the term "disorder". Ideas about pathoplasty, pathomorphosis and registers of psychopathological disorders have been replaced by the concept of comorbidity. At the same time, clearer definitions of all terms appeared, dictating a more differentiated and formalized description of the phenomena observed in the clinic. As a result, clinicians had to abandon not only the concept of the disease, but also of the syndrome, and the concept of a symptom was largely replaced by the term "criterion".

The concept of nosology as "the unity of the clinic, dynamics and etiopathogenesis" was replaced by nosography as a predominantly taxonomic description of conditional psychopathological units, which began to be denoted by the term "disorder". Ideas about pathoplasty, pathomorphosis and registers of psychopathological disorders have been replaced by the concept of comorbidity. At the same time, clearer definitions of all terms appeared, dictating a more differentiated and formalized description of the phenomena observed in the clinic. As a result, clinicians had to abandon not only the concept of the disease, but also of the syndrome, and the concept of a symptom was largely replaced by the term "criterion".

It is clear that in the context of the socio-economic crisis, the domestic scientific and pedagogical community was not ready for this. Worthy conceptual alternatives were not proposed, but instead, attempts were made to create "translations" of some concepts into others, which were served by various kinds of "tables" for comparing concepts that were different in essence. All this could not but affect the system of vocational education, as a result of which the real advantages of the new classification were seriously obscured.

All this could not but affect the system of vocational education, as a result of which the real advantages of the new classification were seriously obscured.

Meanwhile, the ICD-10 not only opened the way for the integration of domestic psychiatry with psychiatric schools in other countries [1, 13, 14]. It has brought such positive aspects to our clinical theory and practice as the uniformity and clarity of the diagnosis, its multidimensionality and structure, and also opened up opportunities for greater differentiation of psychopathological conditions. ICD-10 made it possible to present the entire set of psychopathological conditions in the form of a single system of categories. It significantly expanded and complicated the picture of nosographic concepts, especially in the field of borderline mental disorders. All this turned out to be possible by increasing the reliability and reproducibility of diagnostic conclusions, reducing the proportion of subjectivity, theoretical predilections and socio-ideological pressure in them. This circumstance, in turn, for the first time in the history of Russian psychiatry, raised the issue of developing uniform standards for treatment, rehabilitation and prevention based on the diagnosis.

This circumstance, in turn, for the first time in the history of Russian psychiatry, raised the issue of developing uniform standards for treatment, rehabilitation and prevention based on the diagnosis.

In view of the foregoing, the most important condition for the implementation of new educational programs that will be offered by the world psychiatric community is the disclosure of their methodological foundations [6]. Attempts to "mix" or ignore the conceptual origins of the introduced diagnostic procedures and categories will lead to the emergence of natural contradictions between old and new approaches, create unnecessary resistance and protest on the part of practitioners.

Understanding the importance of this, I would like to point out some essential elements of the modern methodological state of psychiatry.

The key in this area is the concept of the specificity of the method of cognition that science uses. Since ancient times, the answer to this question has been the repeatedly replicated position that the main method of psychiatry is the clinical and psychopathological method. However, this statement is only partly true. The methodology of psychiatry has become much more complex in recent years. First of all, it is advisable to single out some varieties of the clinical and psychopathological method. These should, first of all, include the classical phenomenological method. However, he is not the only one. Today, it is possible to single out the clinical-descriptive approach as independent methods, as well as talk about the interpretive (hermeneutic in the broad sense) method. In addition, it is necessary to highlight the categorical and dimensional principles for assessing psychopathological phenomena. The latter gave rise to a psychometric approach, which, in turn, deals with psychopathological characteristics of different nature - an integrative clinical assessment of the patient's condition, an introspective assessment of one's well-being by the patient, as well as a descriptive analysis of behavior and interactions.

However, this statement is only partly true. The methodology of psychiatry has become much more complex in recent years. First of all, it is advisable to single out some varieties of the clinical and psychopathological method. These should, first of all, include the classical phenomenological method. However, he is not the only one. Today, it is possible to single out the clinical-descriptive approach as independent methods, as well as talk about the interpretive (hermeneutic in the broad sense) method. In addition, it is necessary to highlight the categorical and dimensional principles for assessing psychopathological phenomena. The latter gave rise to a psychometric approach, which, in turn, deals with psychopathological characteristics of different nature - an integrative clinical assessment of the patient's condition, an introspective assessment of one's well-being by the patient, as well as a descriptive analysis of behavior and interactions.

In short, the phenomenological method is based on the fact that psychopathological phenomena and the connections between them are intuitively (more precisely, empathically) “grasped” and mediated by the subjective perception of the clinician, and then repeatedly reproduced in his clinical experience [17, 22, 27] . Such reproduction and comparison with the experience of other clinicians is the basis for the objectification and clinical qualification of psychopathological phenomena, which manifests itself in the so-called "agreement" of professionals. This method is characterized by integrity and at the same time insufficient differentiation, it is intuitive, and therefore subject to the influence of arbitrary preferences and subjectivism. At the same time, this approach is universal, empirical and based on expert assessments. In addition, by virtue of these properties, it is aimed at identifying the "leading" syndrome and is internally related to ideas about the nosological classification of mental disorders.

Such reproduction and comparison with the experience of other clinicians is the basis for the objectification and clinical qualification of psychopathological phenomena, which manifests itself in the so-called "agreement" of professionals. This method is characterized by integrity and at the same time insufficient differentiation, it is intuitive, and therefore subject to the influence of arbitrary preferences and subjectivism. At the same time, this approach is universal, empirical and based on expert assessments. In addition, by virtue of these properties, it is aimed at identifying the "leading" syndrome and is internally related to ideas about the nosological classification of mental disorders.

The second type of clinical and psychopathological method is associated with clinical and descriptive methodology, which is largely implemented in the ICD-10 [1, 14]. It aims at objectified observation and a standardized description of the reproducible psychopathological, physiological and social manifestations of a mental disorder. This method allows you to select diagnostic criteria with the greatest differentiating ability, i.e. it is criterion in nature. The clinical-descriptive method is based on clearly described rules for making a diagnosis, which makes it operational. Finally, he suggests the need to correlate the selected parameters with other signs of mental disorders that the patient has. Such a comparison is made additively, which leads to the concept of comorbidity of mental disorders. At the same time, these disorders are considered as independent and relatively independent conditions. The method under consideration makes it possible to validate the classified categories based on their reproducibility and consistency of expert assessments, and also takes into account their clinical interpretation and social significance when identifying diagnostic categories.

This method allows you to select diagnostic criteria with the greatest differentiating ability, i.e. it is criterion in nature. The clinical-descriptive method is based on clearly described rules for making a diagnosis, which makes it operational. Finally, he suggests the need to correlate the selected parameters with other signs of mental disorders that the patient has. Such a comparison is made additively, which leads to the concept of comorbidity of mental disorders. At the same time, these disorders are considered as independent and relatively independent conditions. The method under consideration makes it possible to validate the classified categories based on their reproducibility and consistency of expert assessments, and also takes into account their clinical interpretation and social significance when identifying diagnostic categories.

The clinical descriptive method strives for the unambiguity of diagnostic conclusions, which can be expressed in excessive rigidity and mechanism of diagnostic procedures. It is distinguished by the complexity of rules and procedures, which leads to excessive formalization of diagnostics. At the same time, the clinical-descriptive method allows for a detailed categorization of mental disorders and their quantitative assessment. The independence of assessments and comorbidity within the framework of this methodological approach generate a multidimensional dimensional assessment of the mental state. However, within the framework of this method, it is not possible to adequately take into account the dynamics of mental disorders and implement the dialectical provisions of the “psychiatry of the current”.

It is distinguished by the complexity of rules and procedures, which leads to excessive formalization of diagnostics. At the same time, the clinical-descriptive method allows for a detailed categorization of mental disorders and their quantitative assessment. The independence of assessments and comorbidity within the framework of this methodological approach generate a multidimensional dimensional assessment of the mental state. However, within the framework of this method, it is not possible to adequately take into account the dynamics of mental disorders and implement the dialectical provisions of the “psychiatry of the current”.

The third method is interpretative. Its essence can be reduced to the desire to describe, understand and conceptually explain the meaning of various psychopathological phenomena, based on ideas about their systemic organization, dynamic relationships and hierarchical structure. With this approach, clinical phenomena are only a reflection of intrapsychic and interpersonal processes (motives, experiences, forms of communication, structural and dynamic rearrangements of the psyche), and psychopathology itself turns out to be a refraction of psychological processes that occur normally. The essential task of the interpretive approach is to identify the process of changes in the intrapsychic structure, while its external expression in the form of symptoms, syndromes or disorders is insignificant and secondary. At the same time, “understanding” of mental disorders without their conceptual explanation is impossible [23, 26].

The essential task of the interpretive approach is to identify the process of changes in the intrapsychic structure, while its external expression in the form of symptoms, syndromes or disorders is insignificant and secondary. At the same time, “understanding” of mental disorders without their conceptual explanation is impossible [23, 26].

This method is especially often used in psychotherapy. At the same time, he sins with theoretical relativity, as a result of which conclusions can acquire a speculative or dogmatic character. At the same time, this does not exclude the equivalence of different interpretations. Describing the interpretive method, it should also be emphasized that in its extreme expression it is anosological, since it does not make fundamental differences between the norm and pathology. At the same time, this methodology provides rich opportunities for assessing the patterns of transformation of psychopathological states that cannot be reduced to a progredient “processuality”. It also potentially opens up rich opportunities for psychophysiological comparisons.

It also potentially opens up rich opportunities for psychophysiological comparisons.

Another important point, which is increasingly being addressed in modern classifications of mental disorders, is the principle of dimension. It is based on the assumption that psychopathological phenomena can be measured, and since the measurements of individual characteristics are independent and independent, this theoretically gives rise to the potential multidimensionality of psychopathological assessments. This circumstance is widely used in clinical scales, which have become extremely widespread in recent years.

However, there are serious methodological nuances in this approach. The point is that the clinician must be very clear about what he is measuring when using psychometric instruments. Without this, all measuring procedures lose their meaning. Experience in this area shows that today there are three different approaches to collecting information for the implementation of measurement procedures in psychiatry [25]. The first has to do with the use of clinical rating scales such as the Hamilton scale for depression. When using them, the clinician relies on his own, gleaned from experience, measure of the severity of a psychopathological phenomenon, such as depression. In other words, fixing low mood or anhedonia, the psychiatrist, in addition to external signs and statements of the patient, also takes into account the degree of his own empathic perception of disorders in the patient's affective sphere.

The first has to do with the use of clinical rating scales such as the Hamilton scale for depression. When using them, the clinician relies on his own, gleaned from experience, measure of the severity of a psychopathological phenomenon, such as depression. In other words, fixing low mood or anhedonia, the psychiatrist, in addition to external signs and statements of the patient, also takes into account the degree of his own empathic perception of disorders in the patient's affective sphere.

The second psychometric approach is aimed at recording the patient's introspective assessments and is based on his self-report. An example of this approach is the Beck Depression Inventory. A quantitative assessment of the severity of depression is made on the basis of subjective signs of a mental disorder recorded by the patient himself. It is clear that such a principle may have significant differences from the integrative clinical assessment, since the internal picture of the disease always has its own specific features.

Finally, the third approach implemented in psychometric procedures consists in recording the patient's objective reactions to standard stimuli. So, in the case of using the MMIL psychodiagnostic technique for the purpose of diagnosing depression, the choices that the patient makes in answering the test items are determined by his dominant attitudes and attitudes. A similar situation develops when conducting neurocognitive tests. In other words, such psychometric tests make it possible to objectively record the response styles of patients and, by their nature, can be considered as methods for descriptive analysis of behavior.

All these considerations are important to take into account when constructing a classification and constructing a typology of psychopathological states, since the general methodological drift in this area is directed towards the development of dimensional and multidimensional models.

However, there are questions here as well. Central among them is the definition of the leading axes of psychopathological assessment. In previous classifications, in particular, in DSM-IV, the axis of categorical psychopathological diagnostics, the axis of personality disorders and intellectual disorders, the axis of somatic burden, the axis of the severity of psychosocial stress, and the axis characterizing the level of social functioning were singled out as independent axes [24]. How will these planes of psychiatric assessment be reflected in future classifications of mental disorders, on the basis of what theoretical and practical considerations will they be distinguished?

In previous classifications, in particular, in DSM-IV, the axis of categorical psychopathological diagnostics, the axis of personality disorders and intellectual disorders, the axis of somatic burden, the axis of the severity of psychosocial stress, and the axis characterizing the level of social functioning were singled out as independent axes [24]. How will these planes of psychiatric assessment be reflected in future classifications of mental disorders, on the basis of what theoretical and practical considerations will they be distinguished?

It seems that, in any case, it is fundamental in the methodological plan to take into account the social conditionality of diagnostics. This implies the need to use the classification in different and sometimes little overlapping areas of mental health, which are driven by societal needs. These areas include functions related to the determination of an individual prognosis, the development of differentiated treatment and rehabilitation plans, expertise, the definition of organizational priorities for psychiatric services and their relationship with general medicine and the social sphere. Particularly relevant for our country is the creation of a classification of mental disorders for primary health care professionals. Finally, the new classification should open up possibilities for studying the pathogenesis and sociogenesis of mental disorders.

Particularly relevant for our country is the creation of a classification of mental disorders for primary health care professionals. Finally, the new classification should open up possibilities for studying the pathogenesis and sociogenesis of mental disorders.

In the final section, I would like to emphasize that each new version of the international classification of mental disorders not only records the changes that have occurred in psychiatry over a certain period of time, but also outlines new prospects for its development. If we try to look into the near future, then the progress of our science will be largely associated with the development of social and preventive programs, as well as the formation and development of the so-called "electronic psychiatry". These areas are far from being reduced to organizational measures aimed at activating socio-psychological resources, introducing systems for determining individual “risks” of mental disorders, as well as the emergence of psychiatric patient support services via the Internet. Methodologically, it is important that these areas of mental health development will be implemented on the basis of new concepts and concepts that define psychopathological problems not only, as P.B. Gannushkin [8], from "pathology to normal", but also in the opposite direction - from "normal to pathology". This will naturally lead to a reformulation of the "old" categories and the creation of conditions for expanding the social base of psychoprophylaxis.

Methodologically, it is important that these areas of mental health development will be implemented on the basis of new concepts and concepts that define psychopathological problems not only, as P.B. Gannushkin [8], from "pathology to normal", but also in the opposite direction - from "normal to pathology". This will naturally lead to a reformulation of the "old" categories and the creation of conditions for expanding the social base of psychoprophylaxis.

If we summarize everything that has been said and try to express it in practical recommendations for the implementation of educational programs for doctors, we can propose the following.

• Accompany the introduction of new international classifications with an appropriate theoretical (methodological) justification that would allow for an adequate translation of terms and conceptual “harmonization” of old and new classification paradigms. This is especially true for psychometric sections.

• Determine the levels of competence for making diagnostic conclusions by specialists of different qualifications and various professional groups, including psychiatrists, general practitioners, psychologists, law enforcement officials, etc. Accordingly, develop several versions applicable to various tasks and conditions of psychiatric diagnostics (therapy and rehabilitation, prevention, economic and organizational measures, expertise, etc.).

Accordingly, develop several versions applicable to various tasks and conditions of psychiatric diagnostics (therapy and rehabilitation, prevention, economic and organizational measures, expertise, etc.).

• Create conditions for the gradual mastering of new material by specialists (discussion, training, verification, correction, testing of skills), determine the main stages and forms of training. Provide methodological and computer support for new classifications. For this purpose, it is advisable to strengthen the role of professional associations in the work on adapting new classifications.

Literature list

1. Abramov V.A. ICD-10 — Methodological and clinical basis for reforms in psychiatry // Journal of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology. 1999. V. 5. No. 1. S. 3-12.

2. Bobrov A.E. Actual problems of postgraduate education in psychiatry// Social and clinical psychiatry. 2008. Vol. 19. Issue. 4. pp. 77-81.

4. pp. 77-81.

3. Bobrov A.E. Gambling disorder (pathological gambling): clinical, therapeutic and psychosocial aspects. Moscow: Medpraktika-M publishing house. 2008. 268 p.

4. Bobrov A.E. On improving the classification of personality disorders// Proceedings of the all-Russian conference Implementation of the subprogram "Mental disorders" of the Federal target program "Prevention and control of socially significant diseases (2007--2011)". Moscow: Russian Society of Psychiatrists. 2008. P.35-36.

5. Bobrov A.E. Anxiety disorders: their systematics, diagnosis and pharmacotherapy// Russian medical journal. 2006. V. 14. No. 4. S. 328 - 332.

6. Bobrov A.E., Dovzhenko T.V., Kulygina M.A. Medical psychology in psychiatry. Methodological and clinical aspects// Social and clinical psychiatry. 2014. T. 24. Issue. 1. P.70-75.

7. Veltishchev D.Yu. Affective model of stress disorders: psychic trauma, nuclear affect and depressive spectrum// Social and Clinical Psychiatry. 2006. Issue. 3. S. 104-108.

2006. Issue. 3. S. 104-108.

8. Gannushkin P. B. Psychiatry, its tasks, scope, teaching// Selected Works on Psychiatry/ Ed. . O. V. Kerbikova. Phoenix. 1998. P. 37-38.

9. Gurovich I.Ya., Shmukler A.B., Storozhakova Ya.A. Remissions and personal-social recovery (recovery) in schizophrenia: proposals for the 11th revision of the ICD // Social and clinical psychiatry. 2008. Issue. 4. S. 34-39.

10. Davtyan E.N. Psychiatry today: consequences of globalization// Review of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology. 2012. No. 4. S. 3-6.

11. Kiryanova, E., & Salnikova, L. Social functioning and quality of life of mental patients - the most important indicator of the effectiveness of psychiatric care// Social and clinical psychiatry. 2010. Issue. 3. S. 73-75.

12. Koren E.V., Tatarova I.M., Marchenko A.M., Drobinskaya A.O., Subbotina V.V. The experience of using the ICD-10 in Russian child psychiatry in the perspective of revising the international classification // Social and clinical psychiatry . 2009. Issue 4. pp. 34-41.

2009. Issue 4. pp. 34-41.

13. Kornetov N.A. ICD-10 without adaptation - the cornerstone of the reform of domestic psychiatry// Visnik of the Association of Psychiatrists of Ukraine. 1998. No. 3. S. 39-54.

14. Krasnov V.N. Diagnosis and classification of mental disorders in Russian-speaking psychiatry: section of affective spectrum disorders// Social and clinical psychiatry. 2010. Issue. 4. S. 58-63.

15. Krasnov V.N. Anxiety disorders: their place in modern systematics and approaches to therapy// Social and clinical psychiatry. 2008. Issue 3. S. 33-38.

16. Mikhailov B.V. Clinic and principles of therapy of somatoform disorders// International Medical Journal. 2003. V.9. No. 1. P.45-49.

17. Savenko Yu. S. Introduction to psychiatry. Critical psychopathology. M.: Logos. 2013. 448 p.

18. Savenko Yu.S. Get sick from Foucault// New Literary Review. 2001. No. 49.

19. Tiganov A. S., Panteleeva G.P., Tsutsulkovskaya M.Ya. Endogenous mental illnesses in the version of the international classification of diseases of the tenth revision adapted for use in the Russian Federation (ICD-10)// Psychiatry. 2003. V.2. No. 2. S. 17-25.

S., Panteleeva G.P., Tsutsulkovskaya M.Ya. Endogenous mental illnesses in the version of the international classification of diseases of the tenth revision adapted for use in the Russian Federation (ICD-10)// Psychiatry. 2003. V.2. No. 2. S. 17-25.

20. Tochilov V.A. ICD-10 in Russia - the end of classical psychiatry? / / С social and clinical psychiatry. 2010. Issue 4. S. 64-68.

21. Shevchenko Yu.S., Severny A.A. Clinical assessment of child mental pathology in modern classifications// Social and clinical psychiatry. 2009. No. 4. P.29-33.

22. Jaspers K. Collected works on psychopathology in 2 T. T.2. M.: Publishing Center "Academy". 1996.

23. Arminjon M. Is psychoanalysis a Folk-psychology?// Frontiers in Psychoanalysis and Neuropsychoanalysis. 2013. V. 135. N 4. P. 4-9.

24. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders DSM-IV-TR Fourth Edition (Text Revision). Amer Psychiatric Pub. 2000. 943 p.

Amer Psychiatric Pub. 2000. 943 p.

25. Kursakov A.A., Bobrov A.E. Depression from different perspectives: does the approach to symptoms evaluation determine core components of the disorder? // Abstracts of EPA, 2014. P. 1249.

26. Malan D. Individual psychotherapy and the science of psychodynamics. London etc.: Butterworth & Co. 1979. 275 p.

27. Wiggins O.P., Schwartz M.A. Karl Jaspers// Encyclopedia of Phenomenology/ In L. Embree (ed.) Springer. 1997. P.371-376.

Summary:

Bobrov A. E.

METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF MENTAL DISORDERS AND MODERN TRAINING PROGRAMS FOR PSYCHIATRY

The experience of implementing ICD-10 in our country is considered. The difficulties associated with this were due to the emergence of new and unusual terminology, as well as the difficulties of translation. It also turned out that clinical and theoretical concepts unfamiliar to domestic psychiatrists are hidden behind the new terminology. Under the influence of diagnostic practice focused on the ICD-10, the methodological foundations of Russian psychiatry began to undergo a painful revision.

Under the influence of diagnostic practice focused on the ICD-10, the methodological foundations of Russian psychiatry began to undergo a painful revision.

At the same time, the ICD-10 made it possible to open the way for the integration of domestic psychiatry with psychiatric schools in other countries. It has brought to our clinical theory and practice the uniformity and clarity of the diagnosis, its multidimensionality and structure, and also contributed to the increase of its reliability and reproducibility. ICD-10 has significantly expanded and complicated the picture of nosographic concepts, especially in the field of borderline mental disorders.

The paper subjected to methodological analysis of the clinical-psychopathological approach, which is dominant in our country, identified its varieties (phenomenological, clinical-descriptive and interpretive), as well as categorical and dimensional principles for assessing psychopathological phenomena. Variants of the psychometric approach are analyzed.

Adaptation and implementation of the ICD-11 should be accompanied by the initial methodological rationale for the classification, the definition of differentiated levels of diagnostic competence for specialists with different qualifications. It is also important to create conditions for the gradual mastering of new material by specialists.

Mental disorders in the clinic of endocrine diseases | Antonova K.V.

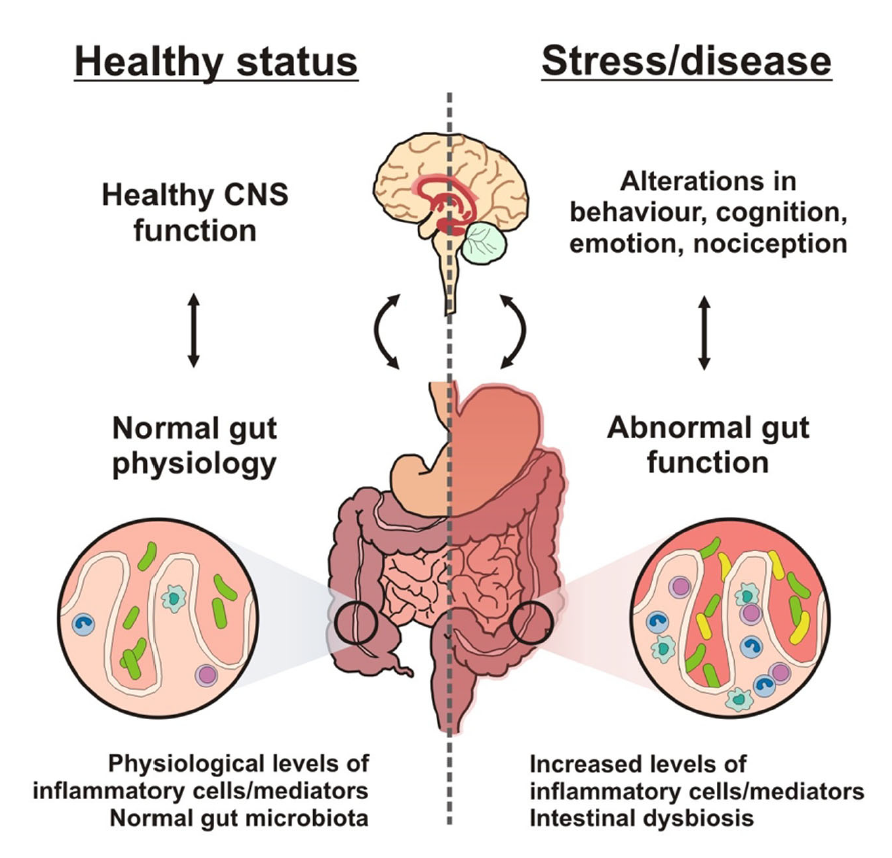

Mental changes are characteristic of the clinical picture of many endocrine diseases. Mental changes in endocrine diseases are diverse, but there are certain patterns of their course. In the early stages and with a mild course of the disease, an endocrine psychosyndrome develops (according to M. Bleuler), and as the disease progresses, this syndrome gradually turns into a psychoorganic one. Against the background of these syndromes, usually due to an increase in the severity of endocrine suffering (but not always), acute or prolonged psychoses can develop. The peculiarity of mental disorders in individual diseases is determined mainly by the predominance of certain disorders in the structure of the syndrome [1]. Endocrine diseases are often accompanied by the development of non-specific psycho-emotional disorders and asthenia.

The peculiarity of mental disorders in individual diseases is determined mainly by the predominance of certain disorders in the structure of the syndrome [1]. Endocrine diseases are often accompanied by the development of non-specific psycho-emotional disorders and asthenia.

The endocrine psychosyndrome is characterized by a decrease in mental activity, a change in drives, instincts, and moods. These changes can be expressed to varying degrees.

Mood disorders are diverse, affective disorders in endocrine diseases are often mixed: depressive-dysphoric, depressive-apathetic, etc. There are states of anxiety and fear. Reactive depression may also develop. With a long and severe course of an endocrine disease, a psycho-organic syndrome develops, as already noted, which is characterized by a global violation of mental functions, which affects all aspects of the personality. In the most severe cases, dementia develops.

Of interest is the relationship between mental changes and pathology of the endocrine glands, the role of hormones in the pathogenesis of mental disorders. In the second half of the twentieth century, the term "psychoendocrinology" appeared. However, the study of mental changes in endocrine pathology began much earlier. Advances in the study of hormone biochemistry and the physiology of the endocrine system led to the development of modern psychoendocrinology.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the term "psychoendocrinology" appeared. However, the study of mental changes in endocrine pathology began much earlier. Advances in the study of hormone biochemistry and the physiology of the endocrine system led to the development of modern psychoendocrinology.

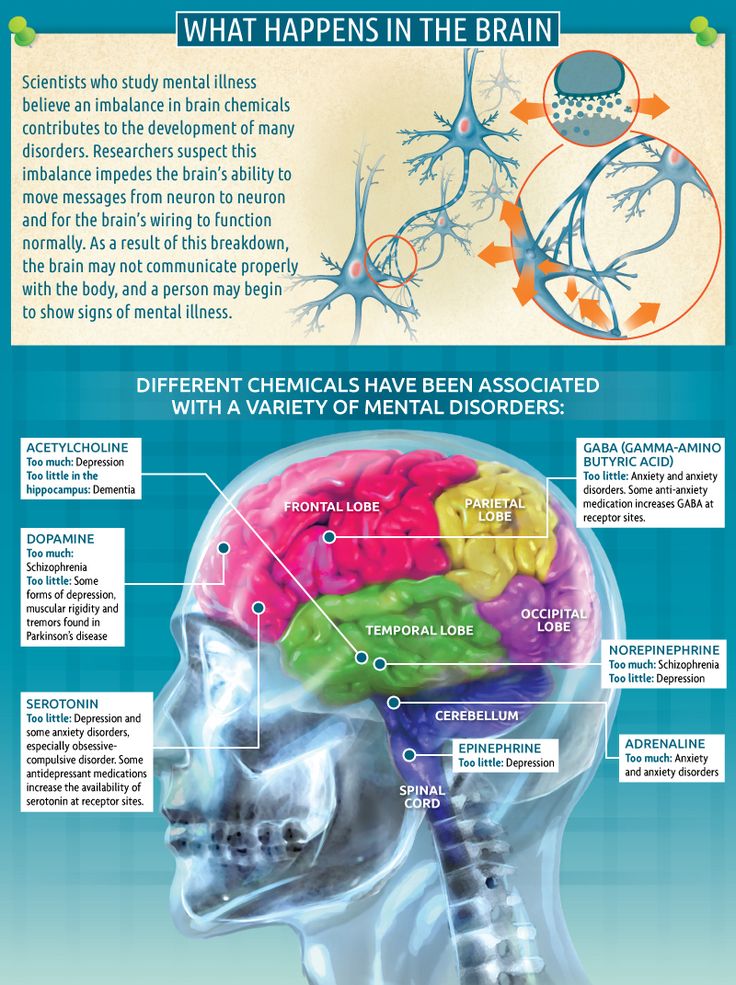

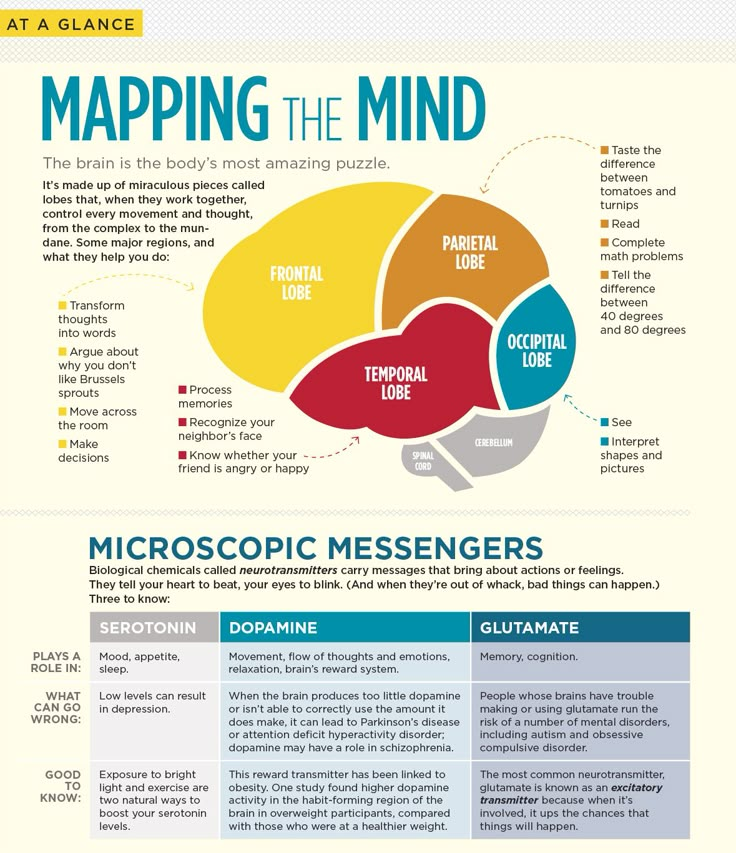

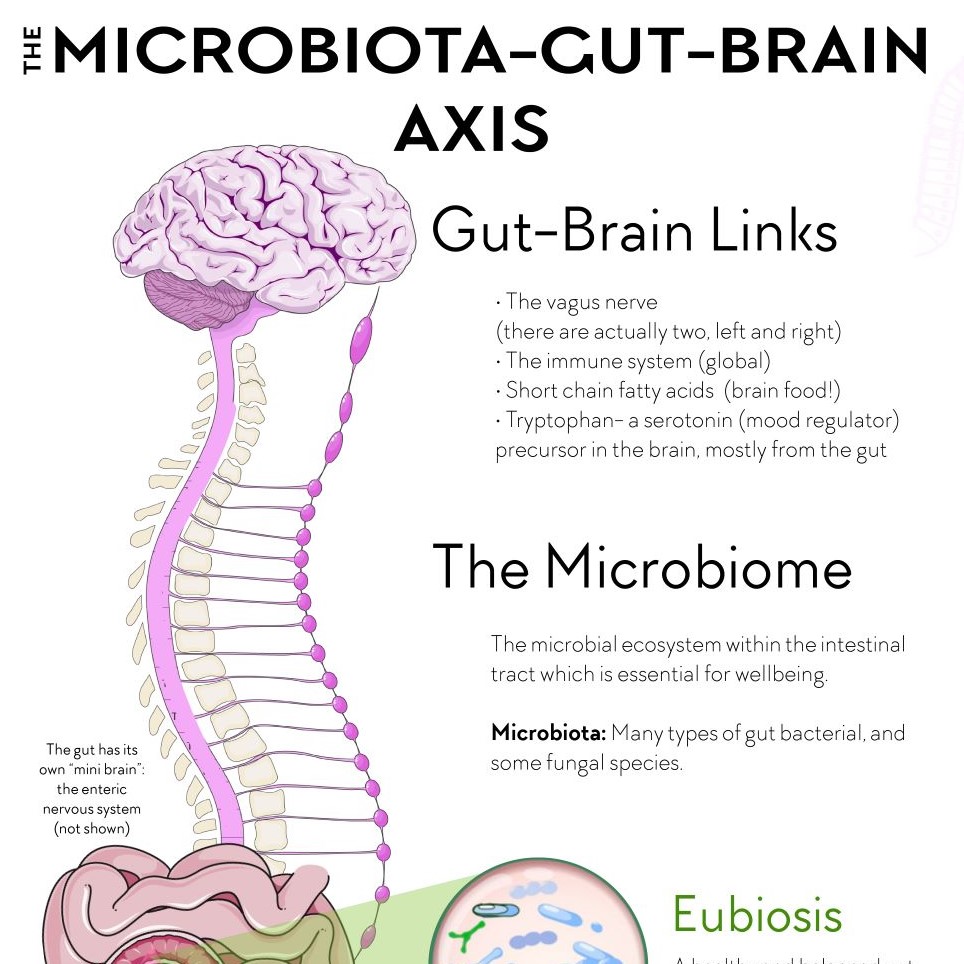

As you know, the hypothalamus regulates the endocrine system and vegetative functions and, being connected with other nuclei of the limbic system, it also participates in the formation of emotions. The mediators serotonin and norepinephrine, which are involved in the regulation of the production of releasing factors by the hypothalamus, are attributed an important role in the development of affective pathology [2]. With depression, there is a change in neuronal plasticity, which is associated with stress-induced hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and an increase in the production of corticotropin-releasing factor, adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol, which leads to a decrease in the activity of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, impaired metabolism of phospholipids, P-substance and neurokines, impaired activity of NMDA receptors with increased toxic effect of glutamate on neurons and impaired interaction of glutamatergic and monoaminergic pathways [3].

In everyday practice, clinicians-endocrinologists have to deal with patients whose psyche is often changed in accordance with the course of a particular endocrine disease.

In various endocrine diseases, general disorders are expressed to varying degrees and in various combinations.

In the syndrome of hypercortisolism, in 80–85% of cases due to an increase in ACTH secretion by the pituitary gland, most often a microadenoma, and in 14–18% of cases due to a primary lesion of the adrenal cortex, in some patients the disease occurs with impaired mental activity.

Itsenko-Cushing's disease is a disease that develops as a result of increased production of ACTH by the pituitary gland, in most cases due to the presence of corticotropinoma of the anterior pituitary gland. Chronic elevated blood levels of ACTH lead to increased secretion of corticosteroids, mainly glucocorticoids. With Itsenko-Cushing's disease, there is a violation of the secretion of all tropic hormones of the pituitary gland. N.M. Itsenko described changes in the psyche in this disease at the beginning of the 20th century.

N.M. Itsenko described changes in the psyche in this disease at the beginning of the 20th century.

According to various sources, the frequency of mental disorders in this pathology is from 45 to 90% [4.5]. The pathophysiological mechanism of mental disorders is still not completely clear. It is believed that an excess of glucocorticoids enhances those states of CNS activity that occurred at the time of the development of hypercorticism. Violation of mental activity is associated with a violation of the formation of b-endorphins and, probably, other peptides. Glucocorticoids affect a number of enzymes localized in CNS cells (glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase, tryptophan hydroxylase, mitochondrial NADP oxidase).

The frequency and severity of mental changes does not correlate with the degree of hypercortisolism. There are cases when patients are first hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital in connection with suicidal attempts. Depression, irritability, loss of libido may be the earliest symptoms, occurring before other clinical manifestations and changes in body weight.

With Itsenko-Kushig disease, euphoria, sleep disorders, depressive states, emotional instability and sometimes psychosis are observed, as well as mental and physical asthenia, more pronounced in the morning. Patients are lethargic, the ability to concentrate is reduced, patients are indifferent to surrounding events. Sleep disorders are often characterized by difficulty falling asleep, rhythm disturbance. Sleep is usually superficial, disturbing.

Mood disorders are possible. Typical depressive states are rare. Depressive states have a pronounced dysphoric coloring, outbursts of rage, anger or fear are possible. Depression is often associated with senestopathic and hypochondriacal disorders. Against the background of asthenia and depression, fixation of patients on special sensations can be observed. There is also an increase in the level of reactive anxiety.

Due to changes in the appearance of patients, overvalued dysmorphomania may occur [6]. Patients are prone to suicidal attempts, especially in the initial period of the disease. Also, patients may develop psychotic states, accompanied by motor excitation, delirious phenomena. The development of the disease leads to an increase in personality changes. With the progression of the disease, Itsenko-Cushing's disease can lead to the development of a psycho-organic (encephalopathic) syndrome. To achieve stable clinical remission of the disease, it is necessary to correct psychoemotional disorders, including adequate psychotropic therapy, at all stages of treatment.

Nelson's syndrome develops after a bilateral adrenalectomy in patients with a severe form of Itsenko-Cushing's disease. Psychoneurological disorders observed in Nelson's syndrome are associated both with the adequacy of compensation for adrenal insufficiency and with increased production of ACTH by the pituitary tumor, its size and localization [5]. In patients with this syndrome developed after bilateral adrenalectomy, in comparison with patients without it, there is an increase in asthenophobic and asthenodepressive syndrome, the appearance of a neurotic syndrome, emotional instability, anxiety, suspiciousness [7].

With hypercortisolism of iatrogenic origin or caused by adenoma of the adrenal cortex, mental disorders are similar to those in Itsenko-Cushing's disease, but are less pronounced.

In the clinical picture of diseases caused by prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas, depression (in 27.8% of cases), sleep disturbances (11.1% of cases), emotional lability (8.3% of cases), memory loss (6.9 cases) are noted [ 5].

Acromegaly is a severe endocrine disease caused by chronic hyperproduction of growth hormone. With acromegaly, all three elements of the endocrine psychosyndrome are expressed: a decrease in mental activity, mood and craving disorders. Patients are apathetic, hardly force themselves to be involved in daily activities. There is a complacent-euphoric mood, a feeling of passive self-satisfaction. Often there are depressive states with anxiety, malice, tension, tearfulness. For patients with acromegaly, dysphoria is also characteristic. As the disease progresses, patients become more and more gloomy, angry, dissatisfied with others, they have a feeling of hopelessness.

As the disease progresses, asthenic symptoms increase, patients are bothered by headaches, often very severe, sleep disorders develop: drowsiness is replaced by insomnia, the sleep rhythm is disturbed. There are also periods of increased physical activity. At the stage of the psychoendocrine syndrome, there is no significant intellectual decline; criticism is sufficiently preserved. If a psychoorganic syndrome develops, memory disorders appear in patients, criticism decreases. In far-reaching cases, states of a kind of autism with sullen grouchiness are described.

The localization and direction of tumor growth also determine some other psychopathological phenomena. With the growth of the tumor towards the temporal lobe, epileptiform seizures, gustatory and olfactory hallucinations are noted. Rarely, symptomatic psychosis may develop.

Craniopharyngioma is a tumor of the pituitary gland. In the clinic, in addition to the endocrine syndrome, hypertensive-hydrocephalic, psychopathological and chiasmatic are distinguished. Psychopathological disorders are characterized by various disorders of consciousness, activity level, memory. The frequency of occurrence of such disorders depends on the localization of the tumor and averages 15%, and after surgical treatment, the frequency of psychoemotional disorders decreases [5].

The clinical picture of the hypothalamic syndrome of puberty, characterized mainly by an increase in the secretion of ACTH and hormones of the adrenal cortex, as well as a violation of the secretion of gonadotropins, in most patients is complemented by neuropsychiatric disorders. These patients have irritability, tearfulness, increased fatigue, depressed mood, and depressive states [4].

Hypopituitarism is a symptom complex, the development of which is associated with a decrease or loss of the function of the anterior pituitary gland. Hypopituitarism develops as a result of destruction of the anterior pituitary gland or hypothalamus. Along with signs of insufficiency of pituitary hormones, symptoms of CNS damage are noted: headaches, drowsiness, loss of interest in the environment, personality changes, psychosis [4]. Mental changes are characterized by a particularly pronounced asthenodynamic syndrome with a deep suppression of drives and vital needs (appetite, etc.). At the beginning of the disease, the psychoendocrine syndrome manifests itself in the form of astheno-depressive conditions, with the course of the disease, changes characteristic of the psychoorganic syndrome may appear.

The variety of processes leading to the development of hypopituitarism, the severity of changes in metabolic processes determine the possibility of developing disorders of consciousness (confusion, delirious states, coma). There are hallucinatory and paranoid episodes.

In Sheehan's syndrome, the degree of pituitary necrosis and subsequent hypopituitarism depends on the severity of blood loss. Mental disorders are also an integral part of the disease picture [1]. A typical picture of mental changes in this disease is characterized by the development of asthenic-dynamic disorders of varying severity in combination with changes in mood (apathy and depression) and drives. The decrease in mental and physical activity gradually increases, patients are lethargic, without initiative. Psychoses are rare.

With a deficiency of growth hormone in adults, there is increased emotional lability, increased fatigue, memory impairment, a decrease in the ability to concentrate and, as a result, a state of emotional depression, social isolation, and problems in the sexual sphere [8].

Hypothalamic diabetes insipidus is a disease caused by a violation of the synthesis, transport and release of vasopressin, manifested by thirst and excretion of large amounts of urine with a low relative density. The main clinical symptoms are thirst and increased fluid intake, polyuria, nocturia, polydipsia and associated sleep disturbance. Some patients experience headache, insomnia, emotional imbalance, sometimes psychosis, decreased mental and mental activity.

Hypercalcemia, which develops as a result of excessive secretion of parathyroid hormone, leads to the development of various clinical manifestations. Marked changes in bone tissue, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, cardiovascular system. In the literature, mental changes in hyperparathyroidism are described little; depression, memory impairment, convulsions or even coma are noted. There were pronounced personality changes from psychasthenic to emotional-volitional shifts with corresponding behavioral disorders such as spontaneity, lack of initiative, gloom, explosiveness. Against this background, memory disorders and inability to concentrate gradually developed, and in some cases psychotic disorders, depressive reactions (sometimes with suicidal thoughts), hallucinatory and paranoid states, and confusion [1].

Timely detection and adequate treatment of hypoparathyroidism contributes to the fact that mental disorders in hypoparathyroidism are rare. Parathyroid hormone deficiency is often the cause of hypocalcemia, and a decrease in the level of ionized calcium causes an increase in nervous and muscle excitability, which causes the appearance of convulsive contractions of skeletal and smooth muscles. Sometimes such paroxysms occur under the guise of epilepsy. It is possible to develop neurosis-like symptoms, mainly in the form of a hysteroform or neurasthenic-like variant. It should be noted that the layering of hysterical reactions can aggravate the course of the main component of the clinical picture - tetany. Patients are quickly tired, lethargic, scattered, there is a decrease in the ability to concentrate, their mood is unstable. Over time, the development of hypoparathyroid encephalopathy with severe memory impairment and a decrease in intelligence is possible.

In syndromes caused by a violation of the secretion of certain gastrointestinal hormones, changes in the psyche are also described. In patients with glucagonoma, in addition to the main clinical signs of the disease (diabetes, changes in the skin and mucous membranes, weight loss, anemia, etc.), some patients have symptoms of CNS dysfunction (ataxia, dysarthria, dementia, optic nerve atrophy, tendon hyperreflexia). reflexes, bilateral Babinski symptoms). Mental disorders are noted, more often depressive states [4].

Carcinoid tumors secrete amines and other biologically active peptides. The clinical picture of the disease is due to the effects of biologically active substances, mainly serotonin. Changes in the psyche observed in patients (depression) are associated with the influence of serotonin precursors on the serotonergic structures of the central nervous system.

An insulinoma is a tumor that secretes insulin and other bioactive substances. In the clinical picture of insulinoma, episodes of hypoglycemic conditions, which are caused by a violation of the regulation of insulin release, come to the fore. In conditions of insufficient supply of the brain with glucose, symptoms of neuroglycopenia develop: mental agitation, inability to concentrate, aggressiveness, negativism, intolerance, anxiety, disorientation, behavioral changes, impaired consciousness, retrograde amnesia or delirium. Along with the listed symptoms, diplopia and other eye symptoms, headache, dysarthria, aphasia, numbness of the lips and tip of the tongue appear. Then comes the loss of consciousness, there are tonic and clonic convulsions. In the future, a coma may develop. Impaired cognitive function of the brain appears at a glycemic level of about 2.49mmol/l.

Frequently recurring hypoglycemic states are accompanied by personality changes. This leads to the fact that patients are diagnosed incorrectly and they are hospitalized in psychiatric hospitals. Attacks of hypoglycemia, accompanied by convulsions, can be regarded as epilepsy. Patients may stay in non-core hospitals for several years until the correct diagnosis is established.