Avoidant attachment in infants

Avoidant Attachment: Definition, Causes, Prevention

It’s well known that the relationships a baby forms in the first years of their life have a deep impact on their long-term well-being.

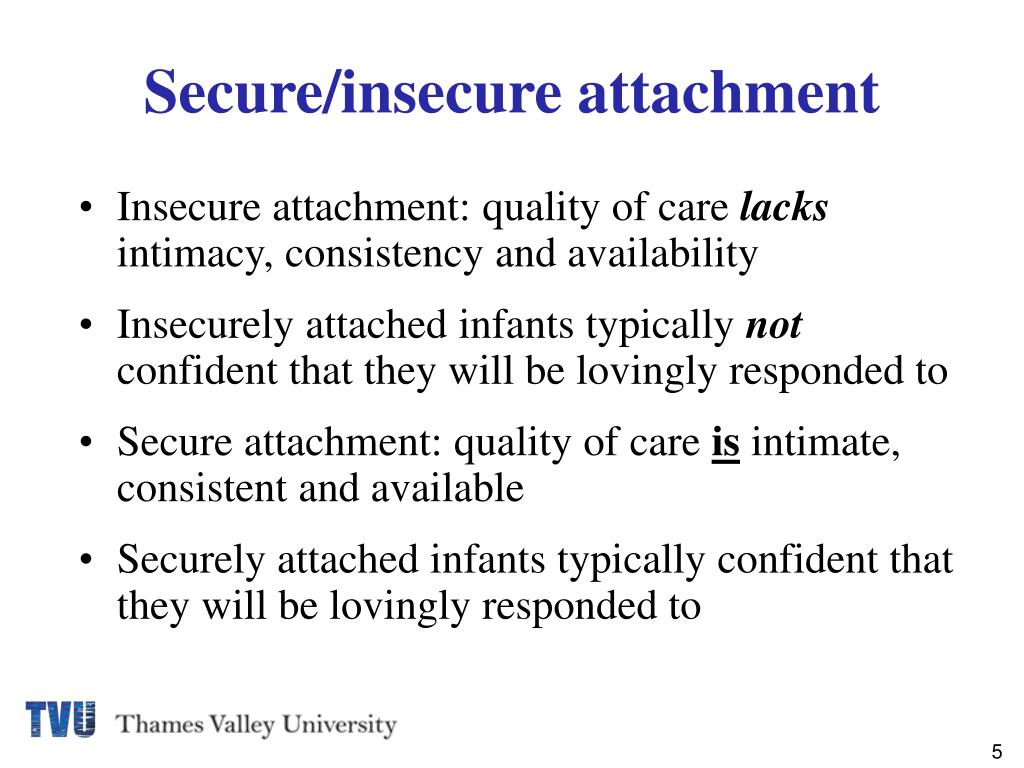

When babies have access to warm, responsive caregivers, they’re likely to grow up with a strong, healthy attachment to those caregivers.

On the other hand, when babies don’t have that access, they’re likely to develop an unhealthy attachment to these caregivers. This can affect the relationships they form over the course of their lifetime.

A child who’s securely attached to their caregiver develops a range of benefits, from better emotional regulation and higher levels of confidence to a greater ability to show caring and empathy toward others.

When a child is insecurely attached to their caregiver, though, they may face a range of lifelong relationship challenges.

One way a child can be insecurely attached to their parent or caregiver is through an avoidant attachment.

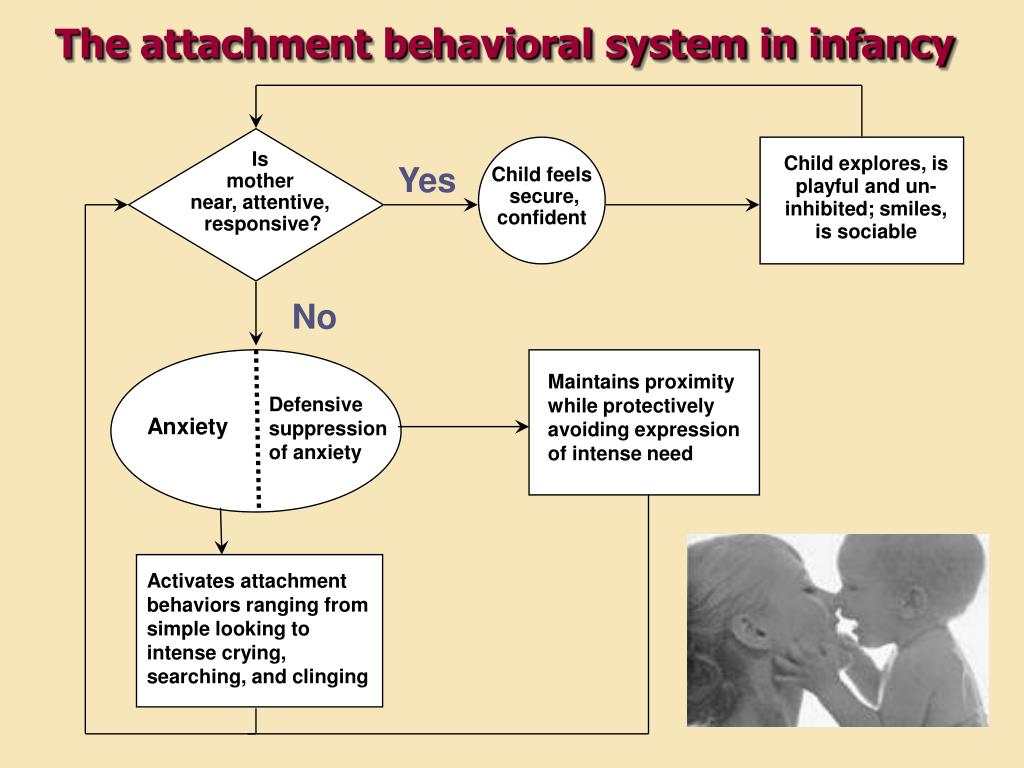

An avoidant attachment is formed in babies and children when parents or caregivers are largely emotionally unavailable or unresponsive most of the time.

Babies and children have a deep inner need to be close to their caregivers. Yet they can quickly learn to stop or suppress their outward displays of emotion. If children become aware that they’ll be rejected from the parent or caregiver if they express themselves, they adapt.

When their inner needs for connection and physical closeness aren’t met, children with avoidant attachment stop seeking closeness or expressing emotion.

Sometimes, parents may feel overwhelmed or anxious when confronted with a child’s emotional needs, and close themselves off emotionally.

They might completely ignore their child’s emotional needs or needs for connection. They may distance themselves from the child when they seek affection or comfort.

These parents may be especially harsh or neglectful when their child is experiencing a period of greater need, such as when they’re scared, sick, or hurt.

Parents who foster an avoidant attachment with their children often openly discourage outward displays of emotion, such as crying when sad or noisy cheer when happy.

They also have unrealistic expectations of emotional and practical independence for even very young children.

Some behaviors that may foster an avoidant attachment in babies and children include a parent or caregiver who:

- routinely refuses to acknowledge their child’s cries or other shows of distress or fear

- actively suppresses their child’s displays of emotion by telling them to stop crying, grow up, or toughen up

- becomes angry or physically separates from a child when they show signs of fear or distress

- shames a child for displays of emotion

- has unrealistic expectations of emotional and practical independence for their child

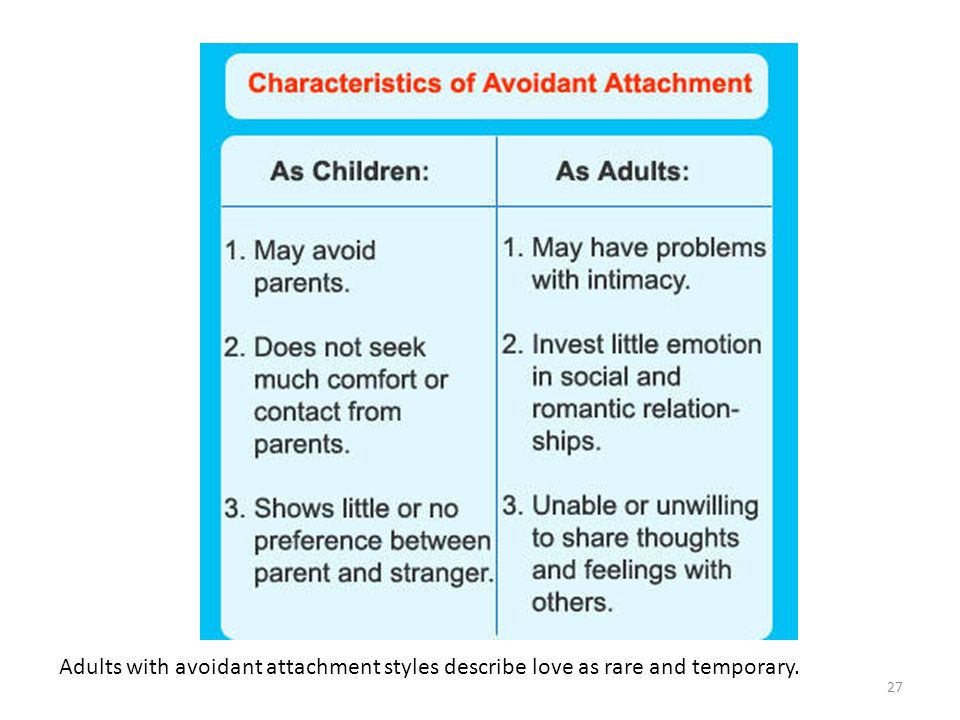

Avoidant attachment can develop and be recognized as early as infancy.

In one older experiment, researchers had parents briefly leave the room while their infants played to evaluate attachment styles.

Infants with a secure attachment cried when their parents left, but went to them and were quickly soothed when they returned.

Infants with an avoidant attachment appeared outwardly calm when the parents left, but avoided or resisted having contact with their parents when they returned.

Despite the appearance that they didn’t need their parent or caregiver, tests showed these infants were just as distressed during the separation as the securely attached infants. They simply didn’t show it.

As children with an avoidant attachment style grow and develop, they often appear outwardly independent.

They tend to rely heavily on self-soothing techniques so they can continue to suppress their emotions and avoid seeking out attachment or support from others outside of themselves.

Children and adults who have an avoidant attachment style might also struggle to connect with others who attempt to connect or form a bond with them.

They might enjoy the company of others but actively work to avoid closeness due to a feeling that they don’t — or shouldn’t — need others in their life.

Adults with avoidant attachment might also struggle to verbalize when they do have emotional needs. They may be quick to find fault in others.

To ensure you and your child develop a secure attachment, it’s important to be aware of how you’re meeting their needs. Be mindful of what messages you’re sending them about showing their emotions.

You can start by ensuring that you’re meeting all of their basic needs, like shelter, food, and closeness, with warmth and love.

Sing to them as you rock them to sleep. Talk warmly with them as you change their diaper.

Pick them up to soothe them when they’re crying. Don’t shame them for normal fears or mistakes, like spills or broken dishes.

If you’re concerned about your ability to foster this sort of secure attachment, a therapist can help you develop positive parenting patterns.

Experts recognize that most parents who pass an avoidant attachment to their child do so after forming one with their own parents or caretakers when they were children.

These sorts of intergenerational patterns can be a challenge to break, but it’s possible with support and hard work.

Therapists focusing on attachment issues will often work one-on-one with the parent. They can help them:

- make sense of their own childhood

- begin to verbalize their own emotional needs

- begin to develop closer, more authentic bonds with others

Therapists focusing on attachment will also often work with the parent and child together.

A therapist can help make a plan to meet your child’s needs with warmth. They can offer support and guidance through the challenges — and joys! — that come with developing a new parenting style.

The gift of secure attachment is a beautiful thing for parents to be able to give their children.

Parents can prevent children from developing an avoidant attachment and support their development of a secure attachment with diligence, hard work, and warmth.

It’s also important to remember that no single interaction will shape a child’s entire attachment style.

For example, if you usually meet your child’s needs with warmth and love but let them cry in their crib for a few minutes while you tend to another child, step away for a breather, or take care of yourself in some other way, that’s OK.

A moment here or there doesn’t take away from the solid foundation you’re building every day.

Julia Pelly has a master’s degree in public health and works full time in the field of positive youth development. Julia loves hiking after work, swimming during the summer, and taking long, cuddly afternoon naps with her sons on the weekends. Julia lives in North Carolina with her husband and two young boys. You can find more of her work at JuliaPelly.com.

Avoidant Attachment: Definition, Causes, Prevention

It’s well known that the relationships a baby forms in the first years of their life have a deep impact on their long-term well-being.

When babies have access to warm, responsive caregivers, they’re likely to grow up with a strong, healthy attachment to those caregivers.

On the other hand, when babies don’t have that access, they’re likely to develop an unhealthy attachment to these caregivers. This can affect the relationships they form over the course of their lifetime.

A child who’s securely attached to their caregiver develops a range of benefits, from better emotional regulation and higher levels of confidence to a greater ability to show caring and empathy toward others.

When a child is insecurely attached to their caregiver, though, they may face a range of lifelong relationship challenges.

One way a child can be insecurely attached to their parent or caregiver is through an avoidant attachment.

An avoidant attachment is formed in babies and children when parents or caregivers are largely emotionally unavailable or unresponsive most of the time.

Babies and children have a deep inner need to be close to their caregivers. Yet they can quickly learn to stop or suppress their outward displays of emotion. If children become aware that they’ll be rejected from the parent or caregiver if they express themselves, they adapt.

When their inner needs for connection and physical closeness aren’t met, children with avoidant attachment stop seeking closeness or expressing emotion.

Sometimes, parents may feel overwhelmed or anxious when confronted with a child’s emotional needs, and close themselves off emotionally.

They might completely ignore their child’s emotional needs or needs for connection. They may distance themselves from the child when they seek affection or comfort.

These parents may be especially harsh or neglectful when their child is experiencing a period of greater need, such as when they’re scared, sick, or hurt.

Parents who foster an avoidant attachment with their children often openly discourage outward displays of emotion, such as crying when sad or noisy cheer when happy.

They also have unrealistic expectations of emotional and practical independence for even very young children.

Some behaviors that may foster an avoidant attachment in babies and children include a parent or caregiver who:

- routinely refuses to acknowledge their child’s cries or other shows of distress or fear

- actively suppresses their child’s displays of emotion by telling them to stop crying, grow up, or toughen up

- becomes angry or physically separates from a child when they show signs of fear or distress

- shames a child for displays of emotion

- has unrealistic expectations of emotional and practical independence for their child

Avoidant attachment can develop and be recognized as early as infancy.

In one older experiment, researchers had parents briefly leave the room while their infants played to evaluate attachment styles.

Infants with a secure attachment cried when their parents left, but went to them and were quickly soothed when they returned.

Infants with an avoidant attachment appeared outwardly calm when the parents left, but avoided or resisted having contact with their parents when they returned.

Despite the appearance that they didn’t need their parent or caregiver, tests showed these infants were just as distressed during the separation as the securely attached infants. They simply didn’t show it.

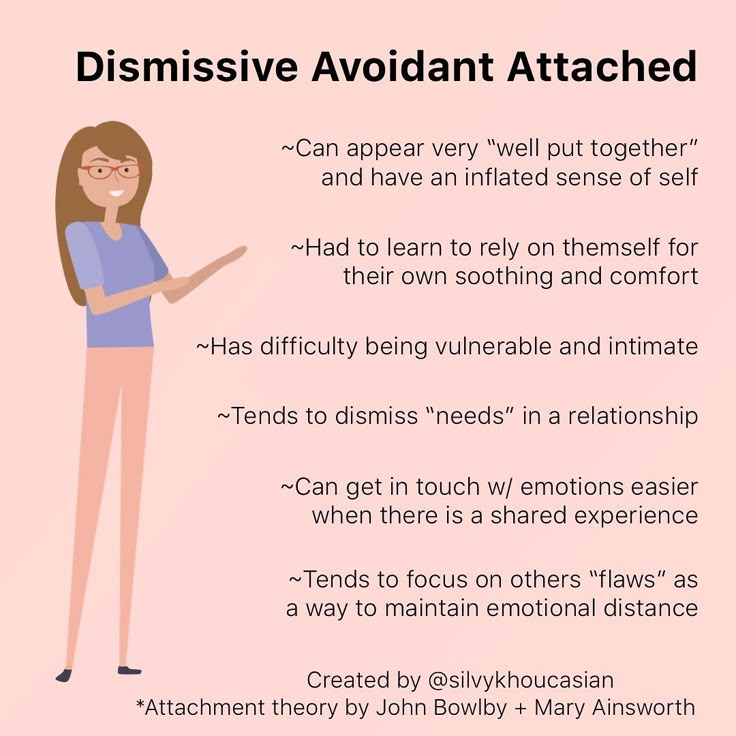

As children with an avoidant attachment style grow and develop, they often appear outwardly independent.

They tend to rely heavily on self-soothing techniques so they can continue to suppress their emotions and avoid seeking out attachment or support from others outside of themselves.

Children and adults who have an avoidant attachment style might also struggle to connect with others who attempt to connect or form a bond with them.

They might enjoy the company of others but actively work to avoid closeness due to a feeling that they don’t — or shouldn’t — need others in their life.

Adults with avoidant attachment might also struggle to verbalize when they do have emotional needs. They may be quick to find fault in others.

To ensure you and your child develop a secure attachment, it’s important to be aware of how you’re meeting their needs. Be mindful of what messages you’re sending them about showing their emotions.

You can start by ensuring that you’re meeting all of their basic needs, like shelter, food, and closeness, with warmth and love.

Sing to them as you rock them to sleep. Talk warmly with them as you change their diaper.

Pick them up to soothe them when they’re crying. Don’t shame them for normal fears or mistakes, like spills or broken dishes.

If you’re concerned about your ability to foster this sort of secure attachment, a therapist can help you develop positive parenting patterns.

Experts recognize that most parents who pass an avoidant attachment to their child do so after forming one with their own parents or caretakers when they were children.

These sorts of intergenerational patterns can be a challenge to break, but it’s possible with support and hard work.

Therapists focusing on attachment issues will often work one-on-one with the parent. They can help them:

- make sense of their own childhood

- begin to verbalize their own emotional needs

- begin to develop closer, more authentic bonds with others

Therapists focusing on attachment will also often work with the parent and child together.

A therapist can help make a plan to meet your child’s needs with warmth. They can offer support and guidance through the challenges — and joys! — that come with developing a new parenting style.

The gift of secure attachment is a beautiful thing for parents to be able to give their children.

Parents can prevent children from developing an avoidant attachment and support their development of a secure attachment with diligence, hard work, and warmth.

It’s also important to remember that no single interaction will shape a child’s entire attachment style.

For example, if you usually meet your child’s needs with warmth and love but let them cry in their crib for a few minutes while you tend to another child, step away for a breather, or take care of yourself in some other way, that’s OK.

A moment here or there doesn’t take away from the solid foundation you’re building every day.

Julia Pelly has a master’s degree in public health and works full time in the field of positive youth development. Julia loves hiking after work, swimming during the summer, and taking long, cuddly afternoon naps with her sons on the weekends. Julia lives in North Carolina with her husband and two young boys. You can find more of her work at JuliaPelly.com.

4 Styles of Attachment - Institute for Family Development

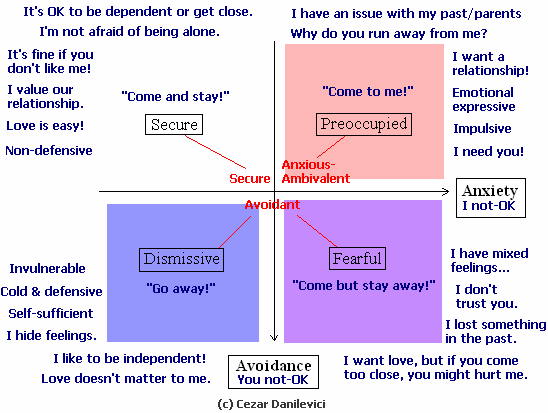

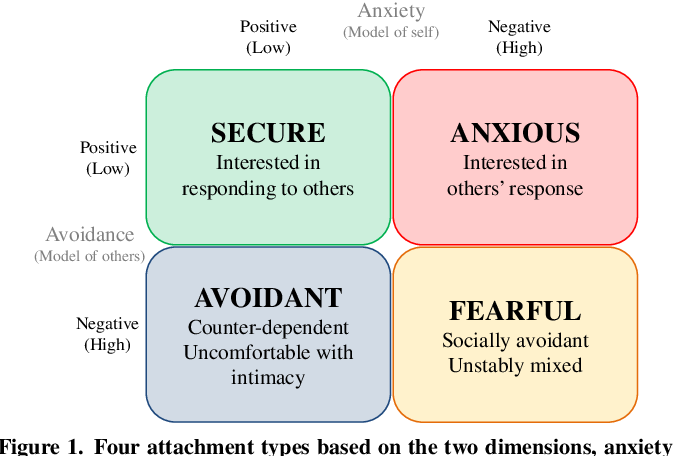

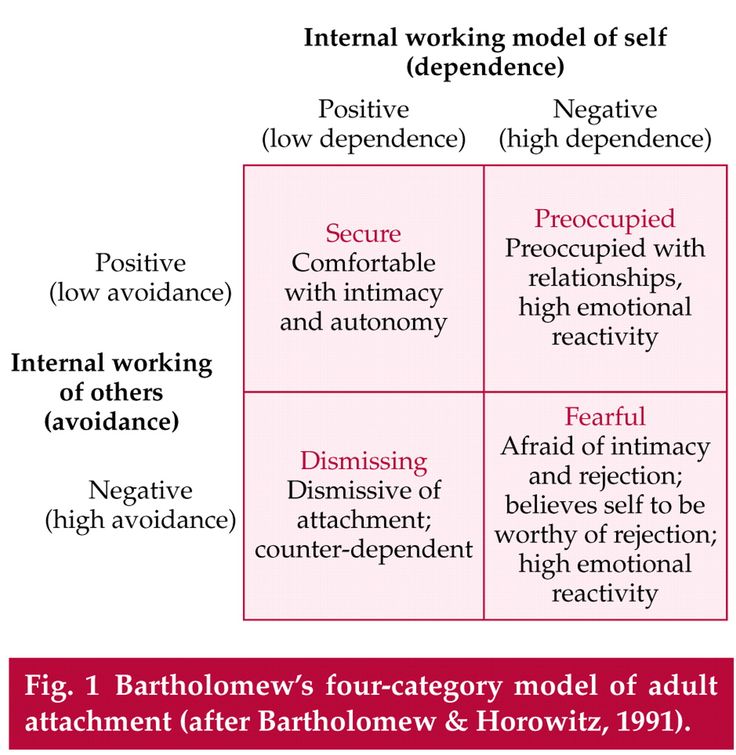

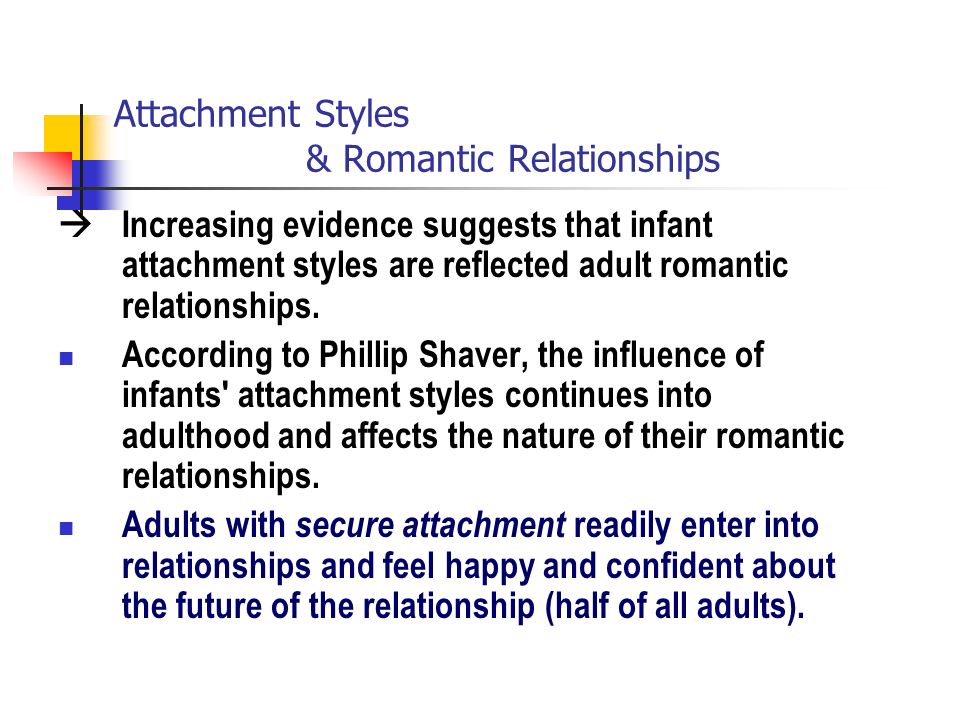

Does your partner avoid intimacy? On the contrary, obsessive? Or perhaps inconsistent and unpredictable? Or is he reliable, gentle, and relationships with him bring peace and satisfaction? One approach to explaining the reasons for such behavior is to determine the attachment style that a person developed in childhood.

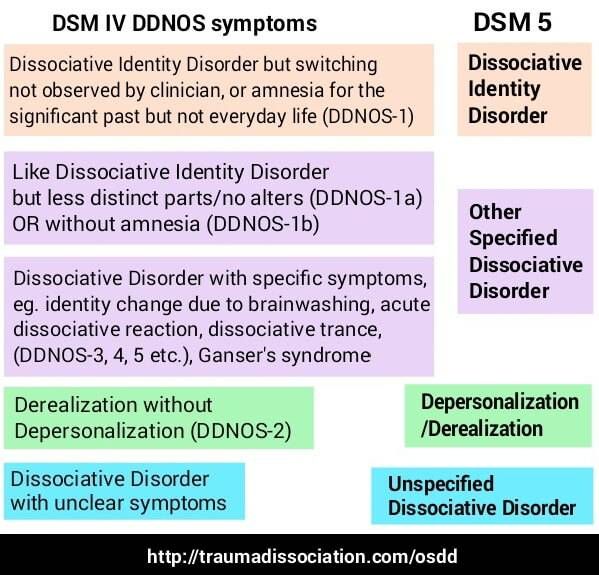

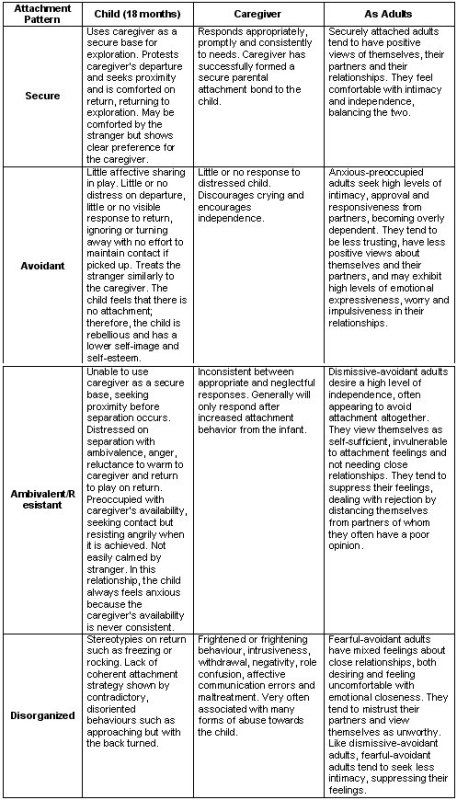

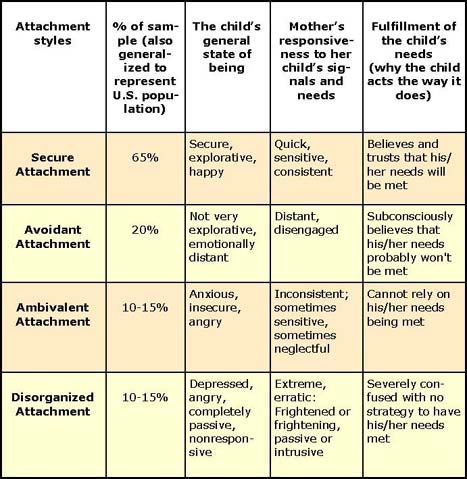

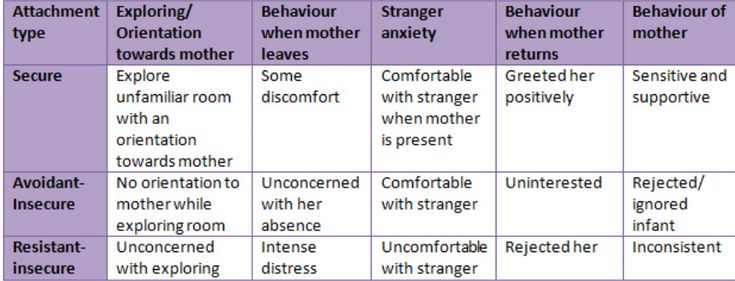

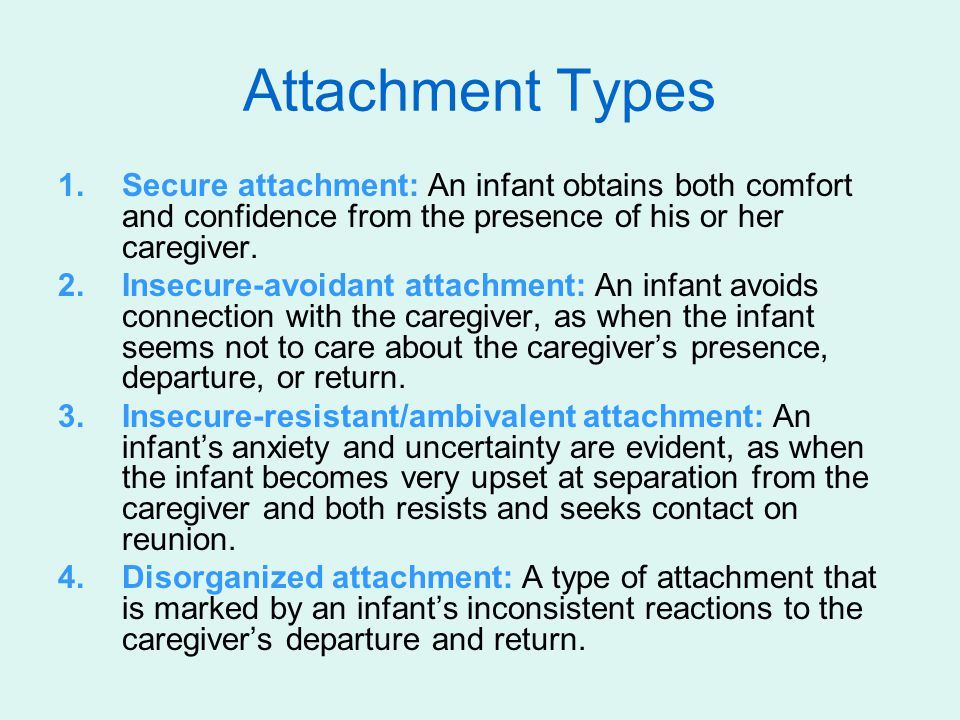

We continue to introduce you to psychologists who have studied attachment. It's about Mary Ainsworth. It was she who described 4 styles of attachment.

Born in the USA in 1913, Mary Ainsworth is one of the 100 most influential psychologists of the 20th century. Ainsworth is an American-Canadian scientist who worked, among other things, with John Bowlby. Ainsworth expanded his attachment theory substantially in the 1970s. Her innovation is especially evident in the development of a method for assessing attachment in infants aged one to one and a half years to a significant adult - the so-called "Strange Situation" procedure

During the procedure, the mother and child are placed in an unfamiliar playroom with toys. At the same time, the researcher observes them through a one-way mirror. The procedure consists of eight successive stages in which the child experiences a short-term separation from and reunion with the mother, as well as the presence of an unfamiliar adult. (here is an example on the video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QTsewNrHUHU)

(here is an example on the video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QTsewNrHUHU)

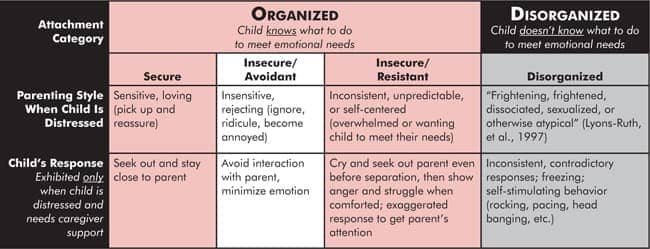

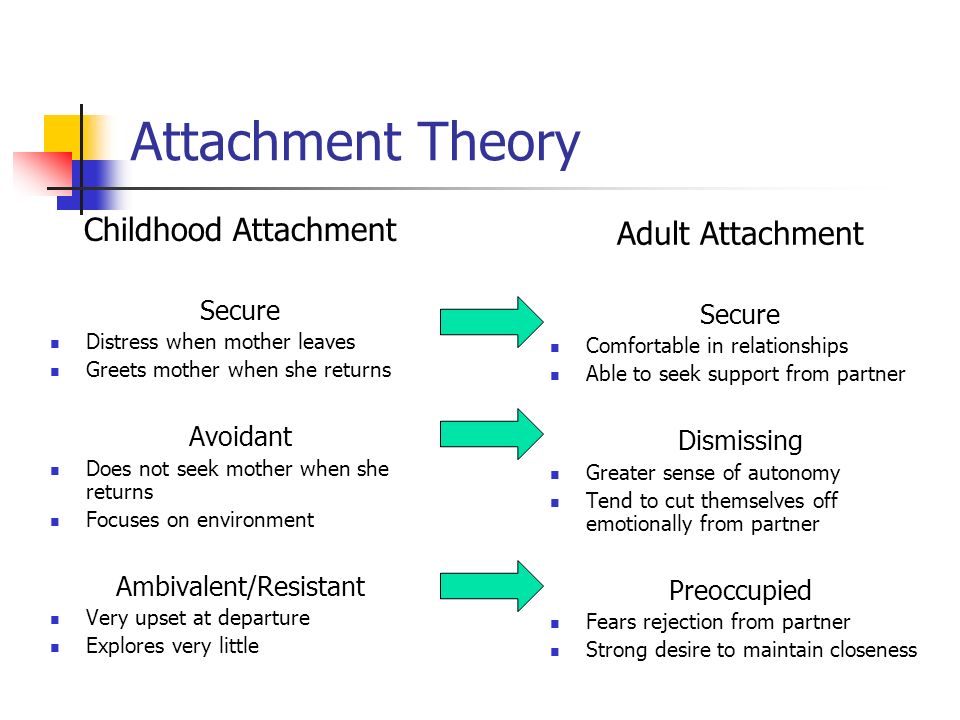

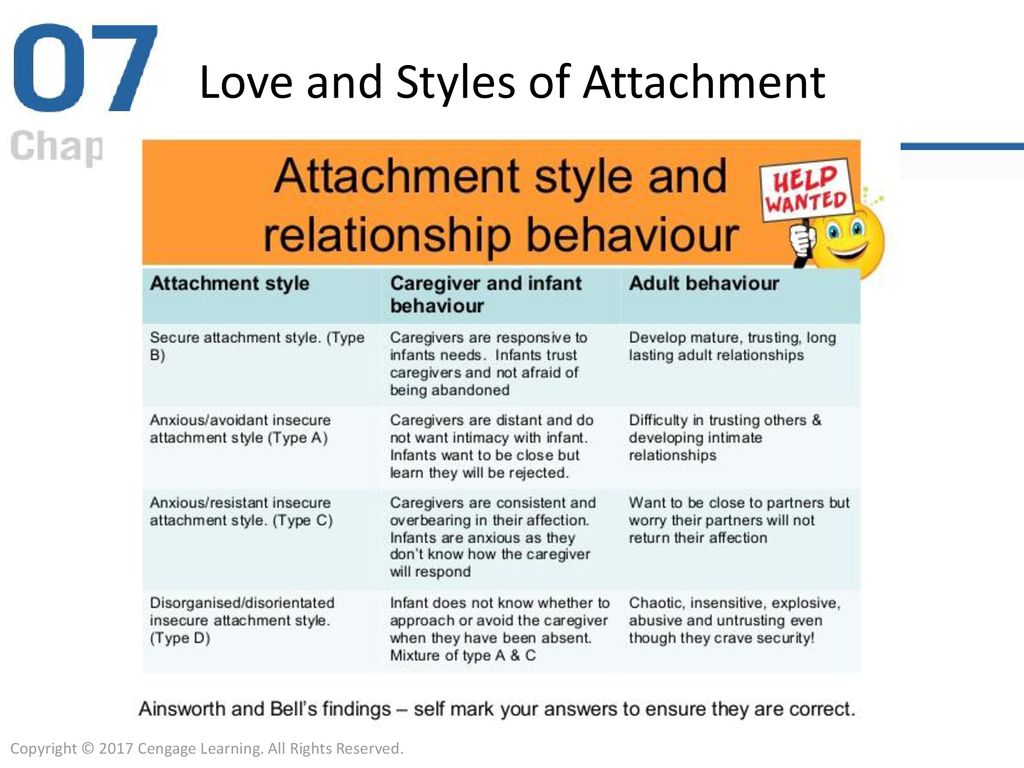

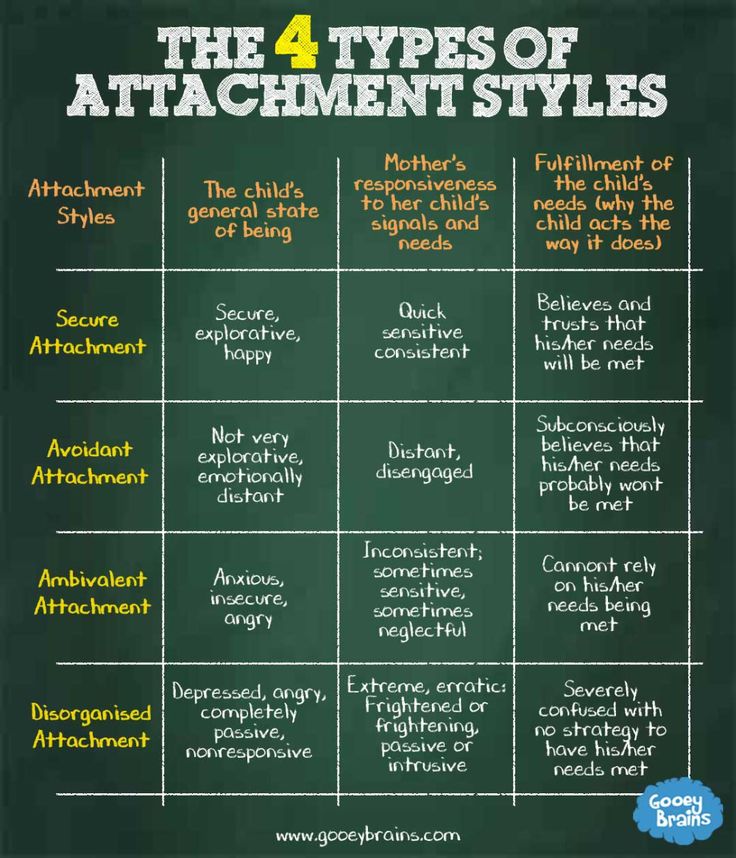

Based on the children's reactions during the experiment, Ainsworth described three main attachment styles: secure, anxious, and avoidant. Ainsworth's colleague, Mary Maine, later described a fourth as disorganized.

RELIABLE. In the experiment, after the departure of the mother, the child is upset, but quickly calms down when she appears, calmly interacts with strangers in the presence of the mother, looks at the mother during the game and smiles, is proactive and inquisitive.

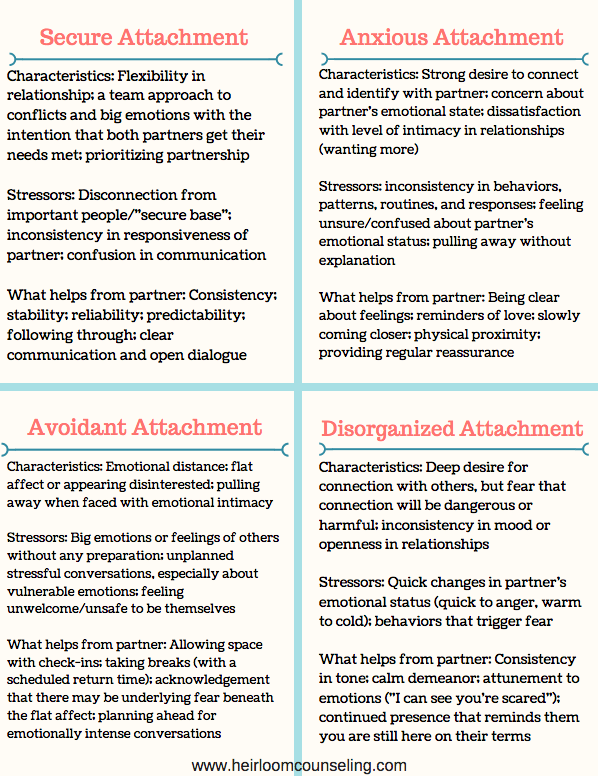

Secure attachment is formed in children who grow up in close-knit families, where parents constantly maintain emotional contact with their children. The parent is available and able to meet the needs of the child in an appropriate way. Securely attached children feel secure and are more likely to explore their environment.

In adulthood, securely attached people do not alienate their loved ones and become dependent on them. They trust loved ones, feel worthy of love, respect a partner and are ready to seek a compromise. Of course, such people also have problems in relationships, but their cause should not be sought in childhood. The secure type is considered the most adaptive attachment style.

They trust loved ones, feel worthy of love, respect a partner and are ready to seek a compromise. Of course, such people also have problems in relationships, but their cause should not be sought in childhood. The secure type is considered the most adaptive attachment style.

ANXIETY attachment is manifested in the strong grief of the child after the departure of the mother, crying, hysterics, which do not stop even after her return. Sometimes aggression towards the mother is manifested, refusal to communicate with strangers. The child explores little, is wary of strangers, even in the presence of a parent.

Anxious attachment is a consequence of the adult's inconsistent behavior, his anxiety about initiatives or the child's health. This type of attachment is formed when parents are unpredictable. They either allow or forbid. Either nearby or not. And the child begins to cling to them, so as not to lose.

People with this type of attachment have low self-esteem. They are dependent, react painfully to changes in relationships, are afraid to be alone and therefore constantly require confirmation of love.

AVOIDING attachment manifests itself in the child's indifference to the care of the mother, the absence of fear of strangers, a low level of initiative and response behavior. Ainsworth suggested that the deadpan behavior of infants is a disguise for grief. This happens when the child's needs have not been taken into account, and he comes to the conclusion that the satisfaction of his needs does not matter to the significant adult.

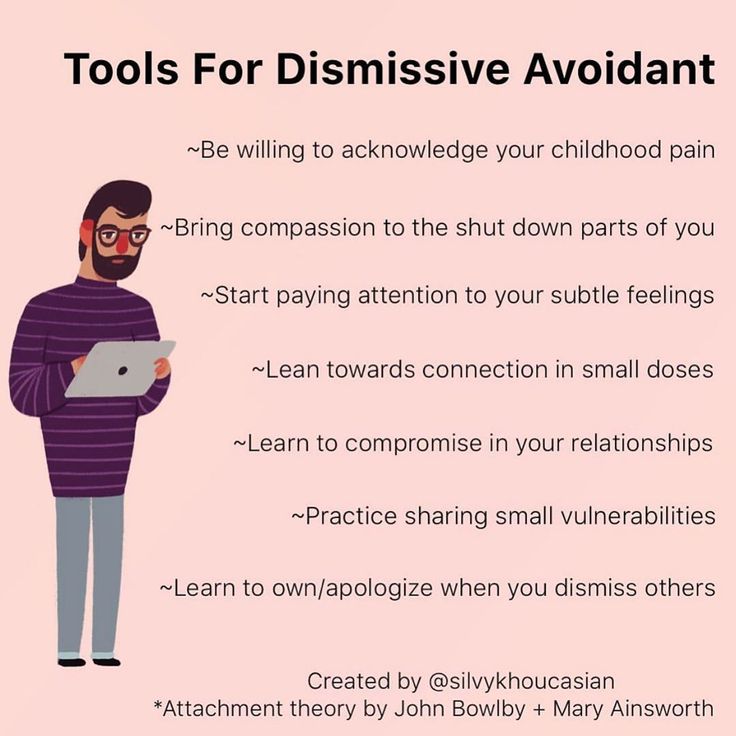

Avoidant attachment is formed when a child has experienced attachment denial, when parents reject the child, do not respond to his needs, do not support him emotionally, or when prohibitive forms of upbringing prevail.

Then a person in adult life usually avoids close relationships, keeps a partner at a distance, and also, as a rule, hides his feelings. Moreover, despite the closed behavior, such a person really needs relationships and support. Without them, he feels lonely.

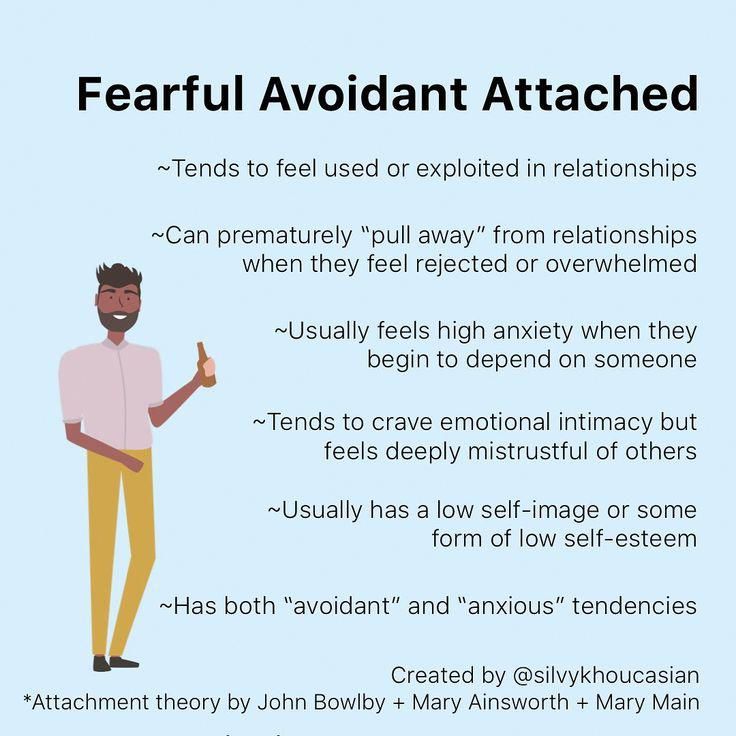

DISORIENTED attachment is expressed in the absence of connection of behavior with the stages of achieving intimacy. Such attachment includes overt manifestations of fear; conflicting behaviour. Children may run to hide when they see a significant adult, or exhibit avoidant or ambivalent strategies when reunited with a parent. This is an indication that the attachment system has been disturbed (for example, by fear or anger)

Such attachment includes overt manifestations of fear; conflicting behaviour. Children may run to hide when they see a significant adult, or exhibit avoidant or ambivalent strategies when reunited with a parent. This is an indication that the attachment system has been disturbed (for example, by fear or anger)

Disoriented attachment is often formed in families where the child is exposed to violence. These children break the rules of human relations by forgoing attachment in favor of power: they don't need to be loved, they prefer to be feared. Their behavior is inconsistent and often change. A person with a disoriented sense of attachment can seek a relationship for a long time, and having achieved it, immediately drop everything and break it off.

***

According to Ainsworth, attachment style is not so much a part of a child's thinking as a characteristic feature of relationships. A child may have a different type of attachment to each of the parents, as well as to any significant adult. However, after about five years of age, children tend to show one consistent pattern of attachment in a relationship.

However, after about five years of age, children tend to show one consistent pattern of attachment in a relationship.

Although attachment style in infancy will not necessarily become the leading attachment style in adulthood, it does have an impact on later intimacy. Insecure attachment styles negatively impact behavior both in childhood and later in life. People with secure attachments are more likely to have adequate self-esteem, independence, strong romantic relationships and self-presentation confidence, and experience less depression and anxiety.

4 types of attachment in children and their impact on us in adulthood

Psychologists distinguish four main types of attachment. They arise in childhood, and in adulthood determine the style of human behavior in relationships. This concept originated in the course of psychological research in the 1960s and 1970s

The guys from the Trends team discussed this material in the episode of the Flying Podcast. You can listen on any convenient platform: in the player above, in Apple Podcasts, CastBox, Yandex. Music, Google Podcasts and wherever there are podcasts.

Music, Google Podcasts and wherever there are podcasts.

What is attachment

Attachment is a type of emotional relationship that involves sharing comfort, care, and joy. The foundations of research into this phenomenon lie in the theories of Sigmund Freud, and they received a special development thanks to the work of the British psychiatrist John Bowlby. He defined attachment as "a long-lasting psychological relationship between people" and concluded that her style in childhood directly affects romantic relationships in adulthood. There are four types of attachment in total.

Securely Attached

Securely Attached Children are very upset when their parents leave, even for a short time, and are happy when they return. When they are afraid, they seek protection in a close adult. They also play with their parents or nannies more often, and in the later stages of childhood show high levels of empathy and less irritability compared to other types. As adults, they have high, healthy self-esteem, love to share their experiences with others, often find themselves in the spotlight, and form healthy and lasting relationships.

How this type of attachment is formed: a significant adult (the parent who spends the most time with the child, or a specially hired person) is responsible for raising the child, taking into account his needs, desires and emotions.

Ambivalent (anxious) type of attachment

Children with an ambivalent type of attachment are suspicious of people. When parents leave, they are upset, but they also do not experience positive emotions from returning. In adulthood, they have low self-esteem, constantly worry that partners do not feel anything for them, and the end of a relationship plunges them into depression.

How this type of attachment is formed : a significant adult is inconsistent, unpredictable - sometimes overprotective, sometimes as cold and detached as possible.

Avoidant

Children with avoidant attachment do not like to spend much time with parents or nannies. They do not reject them, but do not experience positive emotions in case of contact.