Autistic voice tone

Autism And Tone Of Voice | A Moment of Science

By Rory Boothe

Posted February 27, 2020

Tweet

Loading...

Media Player Error

Update your browser or Flash plugin

Read Transcript

Hide Transcript

Transcript

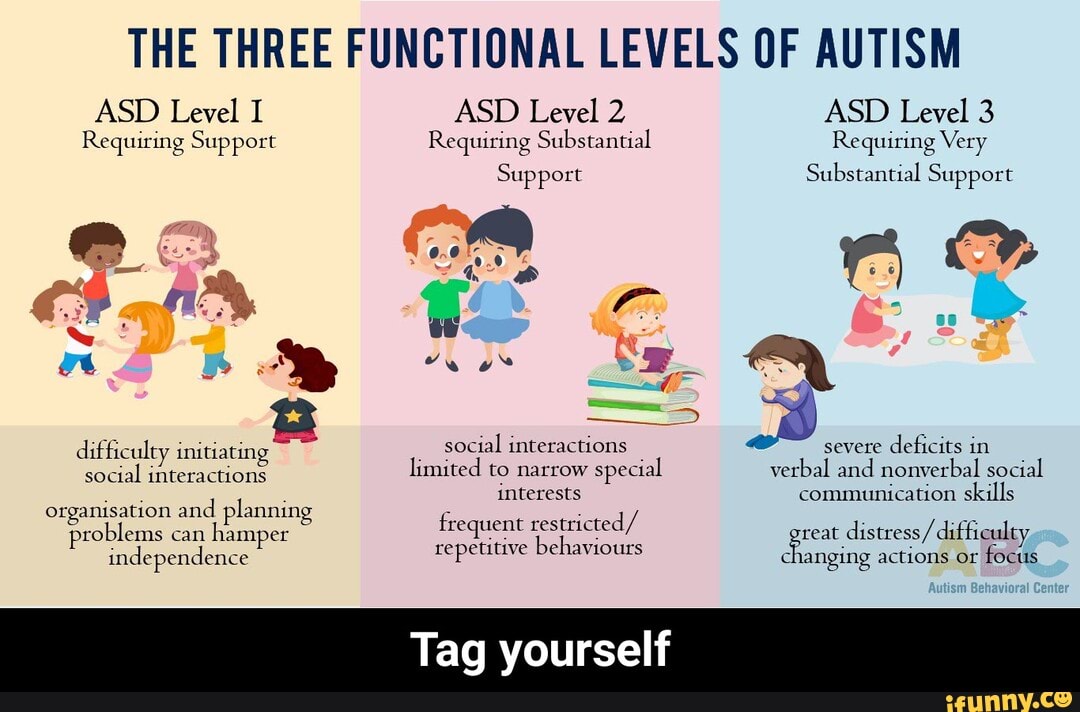

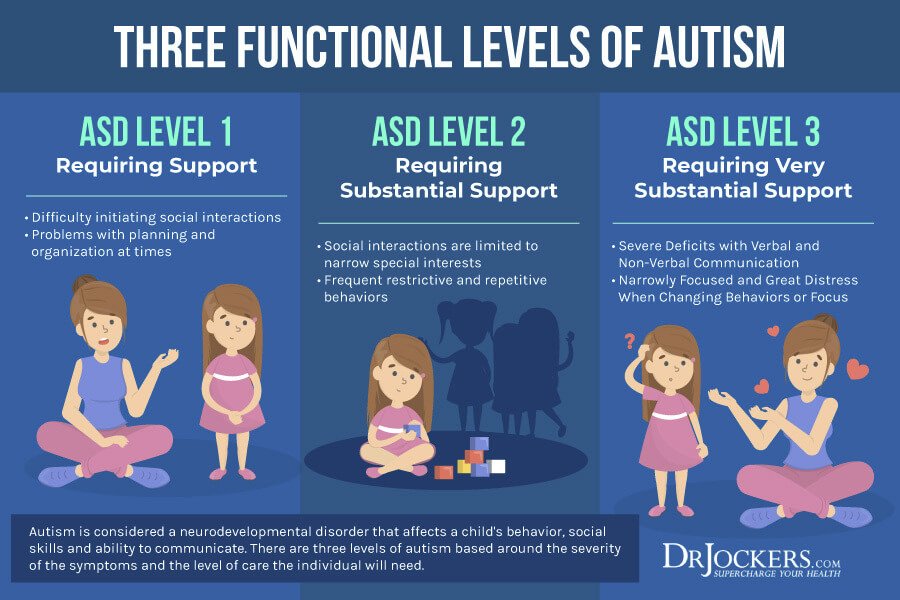

A variety of characteristics are used to diagnose autism in children. Often, it's poor social and communication skills which others observe in children that compel parents to get a child tested. There are currently no unique biological indicators of autism.

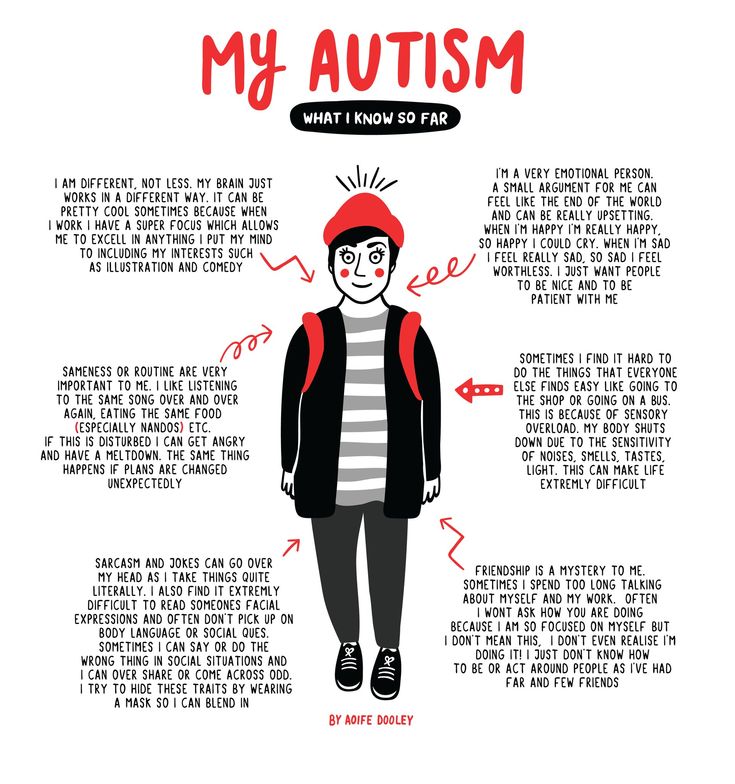

One particularly rich indicator of social differences in autism is the voice. Children with autism often sound different from other people. Some may speak in a flat, monotone voice; others may use unusual modulation or stress different words or parts of words in their speech; and some may speak at an increased volume.

Children with autism also may understand an emotion’s meaning differently when it’s conveyed through tone of voice. But that’s not because they always have trouble producing emotion in speech; the difficulty is that people with autism have problems understanding how tone is used to modify the meaning of words.

So, for example a child with autism may have difficulty parsing the difference between the sentences: “I can’t believe this” and “I can’t believe this.”

Their difficulties in understanding tone and their differences in vocal and facial expression may affect how others form impressions of people with autism. In studies, so-called neurotypical people have reported being less inclined to interact with people with autism after hearing them speak.

As it happens, people with autism are just as likely to judge vocal expressions of people with autism as less natural. That means that both are sensitive to the fact that tone of voice can bring on judgement from other people. But more familiarity with the people on the spectrum helps to minimize negative bias and helps make richer social interactions possible.

Children with autism may understand an emotion’s meaning differently when it’s conveyed through tone of voice. (Scott Vaughan, Wikimedia Commons)

A variety of characteristics are used to diagnose autism in children. Often, it's poor social and communication skills which others observe in children that compel parents to get a child tested. There are currently no unique biological indicators of autism.

One particularly rich indicator of social differences in autism is the voice. Children with autism often sound different from other people. Some may speak in a flat, monotone voice; others may use unusual modulation or stress different words or parts of words in their speech; and some may speak at an increased volume.

Children with autism also may understand an emotion’s meaning differently when it’s conveyed through tone of voice. But that’s not because they always have trouble producing emotion in speech; the difficulty is that people with autism have problems understanding how tone is used to modify the meaning of words.

So, for example a child with autism may have difficulty parsing the difference between the sentences: “I can’t believe this” and “I can’t believe this.”

Their difficulties in understanding tone and their differences in vocal and facial expression may affect how others form impressions of people with autism. In studies, so-called neurotypical people have reported being less inclined to interact with people with autism after hearing them speak.

As it happens, people with autism are just as likely to judge vocal expressions of people with autism as less natural. That means that both are sensitive to the fact that tone of voice can bring on judgement from other people. But more familiarity with the people on the spectrum helps to minimize negative bias and helps make richer social interactions possible.

Read More

fMRIs Could Help Diagnose Autism More Accurately

Could A Brain Scan Help Diagnose Autism?

Support For Indiana Public Media Comes From

Listen to Our Words, Not Our Tone – Autistic Science Person

In one form or another, I see this question from parents a lot:

“Why does my child have to be so rude all the time?”

The assumptions about autistic adults when it comes to tone of voice doesn’t get any better either. In extreme cases, it can even result in the loss of a job.

In extreme cases, it can even result in the loss of a job.

There are a few assumptions neurotypical people have when it comes to tone of voice when anyone talks:

- Everyone who speaks or vocalizes is trying to “send a message” based on how their voice sounds. This includes timbre, pitch, loudness etc.

- Everyone who speaks or vocalizes can control their voice with ease – i.e., can change their timbre/pitch/loudness very easily.

- Everyone who speaks or vocalizes knows exactly what their voice is actually doing while they’re speaking (whether it “sounds defensive” or sounds loud or quiet, etc.).

I literally do not know what my “tone of voice” is doing when other people say I’m being defensive/argumentative/rude/etc.

Let me say that again:

I do not know what my “tone of voice” is doing when I talk.

I do not know how quiet I am talking (for other autistic people, how loud).

I do not know what signal I am sending with my “tone. ”

”

I do not know what my “tone of voice” represents to neurotypical people.

I do not know what emotion or intention neurotypical people think I am sending to them.

I literally didn’t know what “tone of voice” meant until I was 17 years old. And I didn’t truly understand it until I found out I was autistic. I thought it meant “how loud you talk” and “how you structure sentences when you talk.” That’s it.

A Short Story

I once tried to mock a family member because I was so mad that they were telling me “If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all.” I wasn’t trying to say anything mean, I was simply stating factual information. I knew when they said that phrase, it meant I couldn’t say anything because I would be interpreted as “rude.”

I tried to mock them by, from my standards, lilting my voice ridiculously, as if my vocal cords were on a roller coaster going really high to really low to really high again in pitch. I was trying to be condescendingly nice and therefore patronizing.

I was trying to be condescendingly nice and therefore patronizing.

To my shock, their response was to be polite to me!!! Are you serious?! I felt like a clown with that much pitch change in my voice, but apparently it’s how I should be talking all the time! I can’t make sense of this, and it makes me wonder if I actually notice smaller changes in pitch in people’s voices compared to neurotypical people, which could be one explanation as to why our vocal range “sounds monotone” or less expressive to neurotypical people.

Societal Pressure and High Expectations

It doesn’t help that society puts on the layers of constraint if you’re an autistic person who’s raised as a girl and/or a person of color. The gendered notion that kids raised as girls must be polite at all times is absolutely infuriating, and I witnessed this double standard growing up with two older brothers. I’m sure it’s even more constricting for people of color raised as girls and women of color.

Knowing what my “tone of voice” sounds like to NTs emotionally is literally something I don’t have the ability to do. I’ve tried my whole life to figure out this “tone of voice” thing, and while I can somewhat figure out other people’s tone of voice and what they mean, I do not know what my tone of voice is doing at any moment in time.

I’ve tried my whole life to figure out this “tone of voice” thing, and while I can somewhat figure out other people’s tone of voice and what they mean, I do not know what my tone of voice is doing at any moment in time.

Just today my husband had to warn me that I was speaking “defensively” to someone else and so I stopped talking for a few minutes. He wasn’t telling me to stop talking, he was just letting me know because I literally did not know how my voice sounded to that person. It sucks when you know you may be making someone feel a certain way without intending to, and not knowing how to fix it. Depending on the context, sometimes I will stop talking to kind of “reset” my voice, though honestly sometimes this doesn’t work and that’s just how my voice will sound for the rest of the night and I can’t do a thing about it. And I never really know which one will happen unless someone else tells me, because to me it all sounds the same.

Similarly, many of us autistic people may laugh nervously in stressful moments and will be seen as rude, when the laughter has nothing to do with the situation. Instead, it’s due to our own anxiety and stress of not knowing what to say or do. This makes neurotypical people think we are intentionally making fun of a sad or stressful event, or not taking them seriously, when the reason behind our laughter is the opposite of that assumption. We are trying to think of the “correct” neurotypical response to say, have a difficult time thinking of something, and so may laugh in the interim due to stress or confusion.

Instead, it’s due to our own anxiety and stress of not knowing what to say or do. This makes neurotypical people think we are intentionally making fun of a sad or stressful event, or not taking them seriously, when the reason behind our laughter is the opposite of that assumption. We are trying to think of the “correct” neurotypical response to say, have a difficult time thinking of something, and so may laugh in the interim due to stress or confusion.

Neurotypicals Need to Learn to Empathize

Imagine being expected to figure out how a brick wall “feels.” That’s impossible, right? Well it’s the same way when NTs just assume that I am emitting some hidden message with how my voice sounds. I’m not! Listen to the words! I don’t have any “intention” or “emotion” behind my actual voice. I just want you to hear the words.

It is so hard to explain this to neurotypicals because this subconscious social processing is so automatic for them. They don’t even realize how they’re interpreting my tone. I could say the same exact thing as a neurotypical person does (in fact I have) and get chided for it for “arguing” when I was simply stating a fact.

I could say the same exact thing as a neurotypical person does (in fact I have) and get chided for it for “arguing” when I was simply stating a fact.

Interpreting our “tone of voice” like a neurotypical person just doesn’t make sense. It’s like yelling at someone to stand up who literally can’t stand (which actually does happen unfortunately when it really shouldn’t, because ableism is everywhere). I really wish I didn’t have to use an analogy to a physical disability, but so many people do not see anything wrong with “disciplining” their autistic kid over “sounding rude,” when it’s literally punishing them for being disabled.

I’ve learned that I have to be very heavy-handed to get this message across to neurotypical people. It seems like a very hard concept to understand if you have the ability to modulate your tone of voice in the way you want. I guess it’s hard to imagine not having this extra layer of automatic processing occurring constantly in the background.

Please Learn This for Us

We’re not trying to sound X way or have Y intentions. We are just using our words. Focus on the words!

We don’t understand your neurotypical tone of voice rules and literally do not know what we sound like to you.

We don’t know.

Please sit with that. Think about not understanding tone of voice. Try to empathize with that.

Remember that neurotypical people make judgments and assumptions based on autistic people’s tone of voice. So basically, we’re constantly getting judged and told off for something we don’t/didn’t know about.

Imagine getting told off your whole life for doing nothing wrong.

Neurotypical people: When you feel yourself getting defensive about someone’s tone of voice, try to focus on the words if you can. When you know someone is autistic and you’re interacting with them, remember that many of us cannot modulate our tone of voice and are not trying to send you any social signals with our timbre or pitch.![]() And remember, not everyone you interact with will be openly autistic or know they are autistic. Please, please learn this. Don’t rush to judgment and make assumptions – try to ask for clarification. Try to give them the benefit of the doubt. And try to recognize that some people you meet may not be sending any kind of signal with the tone of their voice.

And remember, not everyone you interact with will be openly autistic or know they are autistic. Please, please learn this. Don’t rush to judgment and make assumptions – try to ask for clarification. Try to give them the benefit of the doubt. And try to recognize that some people you meet may not be sending any kind of signal with the tone of their voice.

Thank you for reading.

Like this:

Like Loading...

9000 Autism and hearing problems: confused intersections08/13/08

In many children and adults with autism have various hearing disorders, which enhances autism and complicates the diagnosis of

Source: Spectrum News

9000

At the age of 3, Tyler spoke no more than five words, often with a stutter. Doctors initially thought it was deafness, and experts diagnosed him with auditory desynchronization, a disorder that makes it difficult for the brain to process sounds. However, subsequent examinations showed that Tyler's hearing was normal. nine0003

nine0003

As Tyler grew, his speech problems, as well as other atypical features, led to a flurry of diagnoses, including apraxia of speech, dyslexia, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. His father, Tim, always felt that there was one explanation for his son's many problems. (Family name not included for confidentiality). Tyler had a delay in some motor skills, such as the ability to walk in a straight line, and he also had unusual sensory features, such as a constant need to feel and smell objects. “We went through a lot of mazes trying to figure out how it all could be connected,” says Tim. nine0003

Last year, when Tyler was 11 years old, his parents enrolled him in a speech disorder study. Scientists from the University of California San Francisco confirmed that Tyler's ears are working normally, but his brain has a hard time distinguishing words from extraneous noise. He also had difficulty identifying rapid sequences of sounds, which likely explained his slow and stuttered speech. Given the sensory and motor skills delay, the researchers suspected that he might be on the autism spectrum. A separate autism screening confirmed these suspicions. nine0003

Given the sensory and motor skills delay, the researchers suspected that he might be on the autism spectrum. A separate autism screening confirmed these suspicions. nine0003

This came as a surprise to the family. Tyler has always been outgoing and has never had problems with eye contact, a classic sign of autism. “He’s been given all sorts of diagnoses,” says Tim. “But until recently, autism was not even considered.”

Tyler's late diagnosis is one example of the confusion that can arise when hearing problems and autism overlap. Many people know that children with autism can be overly sensitive to certain sounds, such as the sound of a vacuum cleaner or noise in a busy supermarket. It is much less commonly reported that many people on the autism spectrum have difficulty hearing. Including, they may have disorders that prevent the brain from processing sounds correctly. nine0003

It is still unknown how common these disorders are in autism. However, research suggests that hearing problems are three times more common in autistic people compared to people with typical development. Among deaf and hard of hearing children, the prevalence of autism ranges from 4% to 9%, while among children in general, autism occurs in only 1%, according to some studies.

Some hearing problems and autism may have common biological causes, says psychologist Gene Mankowski of the University of North Carolina, USA. For example, preterm birth and rubella or cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of both hearing problems and autism. Prematurity, intrauterine infections, and other factors can also affect the development of neural connections in the brain, which can affect both hearing and behavior. nine0003

No matter how the overlap between hearing and autism is explained, doctors often confuse the two conditions, resulting in one of the diagnoses not being made or the child being misdiagnosed. Experts may believe that the child has difficulty understanding speech and speaking because of a hearing impairment, and do not attribute this to social and communication difficulties in autism. “I often hear from colleagues: ‘Here is a deaf child, he seems to have symptoms of autism, but no one has tested it,’” says Jackson Rush, an audiologist at the University of North Carolina. “And sometimes it’s the other way around: “This child seems to be autistic, but we think that this may be due to hearing loss.” nine0003

“I often hear from colleagues: ‘Here is a deaf child, he seems to have symptoms of autism, but no one has tested it,’” says Jackson Rush, an audiologist at the University of North Carolina. “And sometimes it’s the other way around: “This child seems to be autistic, but we think that this may be due to hearing loss.” nine0003

The presence of both conditions often results in both diagnoses being made many years later. And the lack of a correct diagnosis leads to missed opportunities to help the child with his current problems. Deaf and hard of hearing children are already at risk of language deprivation during critical periods of brain development. If you add autism to that, the risk is even higher, says Aaron Shield, an early childhood speech development expert at the University of Miami, USA.

To ensure that children with both conditions are not left without the care they need, researchers are conducting research on these intersections to understand how even subtle hearing problems without hearing loss can affect communication skills. In addition, some researchers are working to optimize diagnostic tools and interventions for deaf and hard of hearing children with autism. “Early diagnosis of autism can help parents and teachers understand that a deaf child with autism needs extra support to develop language,” Shield says. nine0003

In addition, some researchers are working to optimize diagnostic tools and interventions for deaf and hard of hearing children with autism. “Early diagnosis of autism can help parents and teachers understand that a deaf child with autism needs extra support to develop language,” Shield says. nine0003

Hearing effects

In a typical situation, sound waves vibrate the tympanic membrane in the middle ear, these vibrations are transmitted to nearby membranes and bones. Vibrations are transferred to the inner ear, causing vibrations in the fluid of the spiral organ - the cochlea. In it, cells covered with tiny hairs pick up these vibrations and turn them into nerve impulses. Electrical signals are carried to the part of the brain responsible for processing auditory information, where they are identified as the chirping of a bird, laughter, or other sounds. nine0003

Interruptions in the perception of sounds can occur due to problems in any part of this path. The peripheral part of the hearing system - the tympanic membrane, bones or cochlear fluid - may not respond to sounds in the right way. Or the auditory perception area of the brain cannot make sense of the incoming information. But the problems may not be as obvious, for example, it is difficult for the brain to distinguish one sound from another due to errors in the neural networks responsible for processing sounds.

Or the auditory perception area of the brain cannot make sense of the incoming information. But the problems may not be as obvious, for example, it is difficult for the brain to distinguish one sound from another due to errors in the neural networks responsible for processing sounds.

One of the first studies on hearing loss in people with autism refers to 1977, it was conducted by the Medical Research Council of London, UK. Experts tested middle ear function and the ability to hear clear tones in 16 children with autism aged 8 to 15 years. Several children were found to have partial hearing loss, and most of the children had abnormal reactions in the ear.

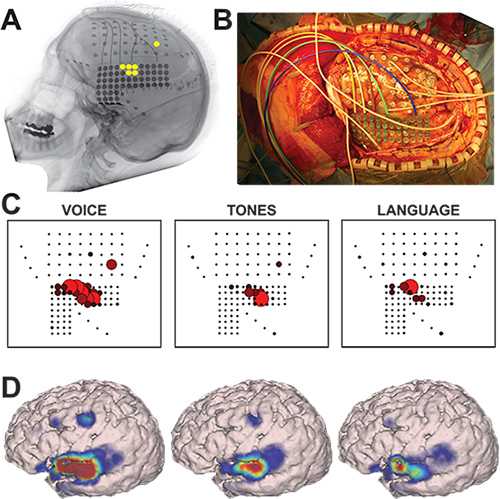

Later advances in technology paved the way for new discoveries regarding autism and hearing loss. Today, researchers can decode the ability to hear sounds at different frequencies and determine how well the middle ear membrane responds to changes in air pressure. They can use electroencephalography (EEG) to monitor how the brain processes sounds and identify auditory deficits in a person whose ears are functioning normally. nine0003

nine0003

With all these new tools, researchers can study the nuances of how hearing problems affect autism traits, in particular how they affect language delay and development, and problems with recognizing other people's emotions. A third of all people with autism do not speak at all or speak only a few words, and it is not known how many of them have auditory difficulties.

One of the key 2016 studies found that almost half of autistic children have at least one problem with their peripheral hearing system, compared to 15% of children with typical development. And these problems often don't show up in obvious ways, such as having unusual hearing sensitivity in one ear and involuntary muscle contractions in the middle ear that distort sounds. In some autistic children, the snail amplifies and transmits sounds in a different way. nine0003

The study showed other unexpected results. Some autistic children have experienced hearing difficulties at frequencies around 2,000 hertz, the average range of human speech, and these children themselves had speech distortions. "I didn't expect to find such a strong relationship between hearing and communication skills," said study lead author Carly Demopoulos, a neuropsychologist at the University of California San Francisco. For some children, the speech sounds they hear are distorted in one way or another, making it harder for them to understand and reproduce those sounds, she explains. Any distortion or inability to properly hear the sound of one's own voice also makes it difficult to speak clearly. nine0003

"I didn't expect to find such a strong relationship between hearing and communication skills," said study lead author Carly Demopoulos, a neuropsychologist at the University of California San Francisco. For some children, the speech sounds they hear are distorted in one way or another, making it harder for them to understand and reproduce those sounds, she explains. Any distortion or inability to properly hear the sound of one's own voice also makes it difficult to speak clearly. nine0003

Auditory processing difficulties in autism may manifest as heightened sensitivity to noise and as an inability to distinguish sounds from one another, other studies suggest. For example, even in a crowded place, people with no hearing problems can usually follow a single conversation and still ignore laughter or the sound of dishes in the background. "Usually the brain is able to focus attention on important sound streams that need to be interpreted," says neuropsychologist Helen Tager-Flushberg from Boston University. However, "some autistic children have great difficulty with this." nine0003

However, "some autistic children have great difficulty with this." nine0003

These difficulties may contribute to speech problems. In 2015, Tager-Flushberg and her colleagues used electrodes to track the activity of autistic and neurotypical teenagers when they heard unexpected loud or soft sounds amid background noise simulating a party. Adolescent brain activity varied greatly, but the researchers found that only minimally verbal adolescents had neural responses to sounds consistent with how they responded to sounds in everyday life, according to questionnaires their parents filled out. nine0003

A follow-up study, due to be published this month in Autism Research, also supports a link between sound perception and language ability. It showed that minimally verbal autistic adolescents and young adults do not hear their own name—their neural responses to the sound of their own name are radically different from those of verbal people with autism and neurotypical people. "It's not like their brains don't perceive sounds on their own, but it's like their brains can't figure out the importance of a sound," Tager-Flashberg says. Data like this could also explain why noise can cause such intense overload in some people with autism. nine0003

Data like this could also explain why noise can cause such intense overload in some people with autism. nine0003

Difficulties with hearing can also hide the emotions that are conveyed by the tone of the person's voice. In 2015, Demopoulos' team asked autistic and neurotypical people to identify the emotional tone of a person who said, "I'll leave the room now, but I'll be back later." The phrase was pronounced in a joyful, angry, frightened or sad voice. The researchers recorded magnetoencephalography data as the children heard different sounds. Autistic children who were slower in processing sounds, or who had a harder time picking up fast sequences of sounds, also had a harder time understanding a speaker's emotional tone. "It doesn't matter what the words were in that sentence," says Demopoulos. nine0003

Mixed features

On the other hand, autism can complicate the communication difficulties of deaf or hard of hearing children. Charlie Hughes, 25, lives in Nottingham, England, was diagnosed with autism at the age of two. Due to Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, he began to gradually lose his hearing, and at the moment he is considered deaf. His parents decided not to fit him hearing aids because "they didn't want to be teased because I look deaf," he recalls in a Skype chat. nine0003

Due to Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, he began to gradually lose his hearing, and at the moment he is considered deaf. His parents decided not to fit him hearing aids because "they didn't want to be teased because I look deaf," he recalls in a Skype chat. nine0003

Hughes did not speak orally until age 8, but in kindergarten he began learning British Sign Language and lip reading. Formal sign language training had an extremely beneficial effect on him, as did contact with social cues, however occasional. After spending several years interacting with people in the deaf community, his body language improved, he says, and it helped him overcome some of the social problems associated with autism. Three years ago, he graduated from the university and received a diploma in forensic science. nine0003

With early diagnosis of hearing problems and early intervention with a cochlear implant or sign language, a deaf or hard of hearing child can develop at the same pace as a hearing child. But if you add autism, it creates entirely new problems. “The goal is to get the child in contact with the language as much as possible, but in this case it is even more difficult to achieve,” Shield says. Eye contact can be uncomfortable for children with autism, and they may not have divided attention—the ability to focus on a subject that another person is focused on. They may find it difficult to perceive the meaning of facial expressions. “These skills are critical to learning sign language,” Shield says. “So the sooner a deaf or hard of hearing child is diagnosed with autism, the greater the chance of a successful intervention.” nine0003

“The goal is to get the child in contact with the language as much as possible, but in this case it is even more difficult to achieve,” Shield says. Eye contact can be uncomfortable for children with autism, and they may not have divided attention—the ability to focus on a subject that another person is focused on. They may find it difficult to perceive the meaning of facial expressions. “These skills are critical to learning sign language,” Shield says. “So the sooner a deaf or hard of hearing child is diagnosed with autism, the greater the chance of a successful intervention.” nine0003

Children with autism whose parents taught them sign language from birth often use inverted gestures that require a specific hand position (outward or inward). They may use their own name instead of sign language pronouns, which hearing autistic children often do, Shield notes. Deaf autistic children who use sign language often repeat the gestures of adults over and over again, just as hearing autistic children repeat randomly the words they hear, a phenomenon called echolalia. nine0003

nine0003

And if deaf children with autism weren't taught sign language from an early age, as Hughes was, then they need special programs to "catch up," says child and adolescent psychiatrist Barry Wright of the University of York in England. For example, a deaf neurotypical child may need support such as visual calendars or visual cues for daily activities to compensate for lack of language contact. An autistic deaf child may need similar language support, coupled with social and behavioral interventions, to reduce problems with eye contact or interpreting facial expressions. nine0003

Many children with autism and hearing problems are diagnosed with autism very late, experts say. Parents and clinicians tend to focus on the most obvious problem, such as stuttering, as in Tyler's case. “Sometimes families put so much effort into speech and language needs that they just don't notice the obvious signs,” says Mankowski. “Families are shocked when we say: “We see these traits, do you mind being tested for possible autism?”. nine0003

nine0003

The examination process is complicated by the lack of reliable clinical tests. Tools such as the ADOS test are not intended for the deaf or hard of hearing. These tests often include questions about whether the child responds to their own name, whether they speak in a monotonous or otherwise unusual voice. As a result, if a child has a hearing problem, then the test may indicate autism, even if the child is not autistic. On the other hand, a specialist may write off some problems as hearing impairment, and as a result, an autistic child will not meet diagnostic criteria. nine0003

Deaf children may be mistaken for autistic children for other reasons. Because of their inability to hear, they may pay increased attention to other sensory experiences. Wright recalls talking to teachers and parents who suspected a deaf child of autism simply because the child spent time on the school playground alone in the corner, tossing leaves into the air and watching them fall.

Because of these complexities, it can take years to understand all the features that a child has because of autism and hearing loss. For example, only last year Hughes learned that there were other aspects to his hearing problems. He wanted to work on his speech so he wouldn't have to depend on interpreters, and he went to an audiologist to get his hearing aids fitted. nine0003

For example, only last year Hughes learned that there were other aspects to his hearing problems. He wanted to work on his speech so he wouldn't have to depend on interpreters, and he went to an audiologist to get his hearing aids fitted. nine0003

“Hearing aids have proven to be quite useful for hearing alarms or cars approaching,” he says, “but not for speech, because it can’t be filtered at all.” The machines amplified human voices, but that didn't mean he could understand them. Further testing revealed for the first time that Hughes also has an auditory perception disorder, meaning his brain doesn't process sounds in the right way. He plans to have more tests to see if specialized hearing aids can help. nine0003

Clinicians develop diagnostic tools to reduce diagnostic delay and improve prognosis for autistic children with hearing loss. Wright and colleagues adapted the ADOS scale for the deaf and hard of hearing by creating equivalent questions for sign language instead of spoken words and phrases. They tested and validated an adapted version for deaf and hard of hearing children at 10 centers in the UK. Other researchers are evaluating tools such as Language Environment Analysis, which record children's expressive speech in natural settings to separate features associated with autism and those associated with hearing. nine0003

They tested and validated an adapted version for deaf and hard of hearing children at 10 centers in the UK. Other researchers are evaluating tools such as Language Environment Analysis, which record children's expressive speech in natural settings to separate features associated with autism and those associated with hearing. nine0003

Another approach is to focus on early detection of inner ear problems that can make it difficult for children, including children with autism, to understand speech. The researchers use a small device with microphones and speakers to measure the inner ear's responses to clicks and other sounds. This test could potentially be done from birth, like modern newborn hearing screening, the researchers say.

Rush, Mankowski and colleagues founded a clinic at the Carolina Institute for Developmental Disorders, USA, to help identify autism and related disorders in deaf and hard of hearing children. In the clinic, diagnostics are carried out by a team of specialists, which includes an audiologist, a psychologist, a speech therapist and an ergotherapist. "There's a lot going on in terms of behavioral differences that goes beyond what we see in kids with hearing loss alone," says Mankowski. nine0003

"There's a lot going on in terms of behavioral differences that goes beyond what we see in kids with hearing loss alone," says Mankowski. nine0003

This kind of clinical practice could save children like Tyler years of being bounced around from one specialist to another in search of answers. After learning that Tyler has autism, Tim and his wife were able to sort out the boy's needs. Initially, he attended a school that specialized in general education for deaf children, a poor choice for a child who was neither hard of hearing nor neurotypical. This year, Tyler is going to attend a private high school for neurotypical dyslexics, which Tyler also has. In retrospect, Tim says the family made decisions based on the assumption that he was a neurotypical child with a speech delay and learning disabilities. If they'd known that Tyler was autistic in the first place, Tim says, "that would have made a big difference." nine0003

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button

You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button

Communication and speech, Scientific research, Sensory and motor skills, Comorbidities

Asperger's Syndrome - Autism and Autism Spectrum Disorders - Development Center speeches in Moscow

We detect Asperger's syndrome in children, we carry out corrective therapy. We help the child develop communication skills with other people, adapt to the world around him, and establish relationships with parents. We conduct comprehensive classes in the center to stimulate physical and psychological development, give homework, and, if necessary, consult by phone. We try not to use or prescribe drugs. nine0098

Features of Asperger's Syndrome

Asperger's Syndrome is a type of autism spectrum disorder. Asperger's syndrome differs from other disorders in that children do not have problems with early speech development. Children quickly learn to speak, but at the same time it is difficult for them to apply their knowledge in practice and communicate with other people.

A child with Asperger's syndrome can be identified by the following problems:

- Often becomes withdrawn and aloof, from the outside it seems that the child is indifferent to other people; nine0108

- Does not understand the interlocutor's facial expressions, gestures and tone of voice;

- Does not understand the figurative meaning of a word or phrase, does not perceive jokes, irony, metaphors;

- Uses words and expressions in conversation, the meaning of which he does not understand;

- Cannot find a topic for conversation, even if he wants to talk;

- Does not understand how to properly start or end a conversation;

- Cannot make friends with other children;

- They do not feel acceptable boundaries in a conversation, they do not perceive social rules of behavior: they may start talking on an inappropriate, personal topic, behave incorrectly; nine0108

- Cannot predict the behavior of other people, imagine an alternative situation and the outcome of an event;

- Does not take someone else's point of view.

It is difficult for a child with Asperger's syndrome to be in society because of a lack of understanding of other people. The need to interact with other people sometimes leads to anxiety disorders, chronic stress. The child may begin to refuse to go to kindergarten and school, circles and sections, walk on the playground.

Usually children with Asperger's syndrome do not have problems with mental development: IQ in such children is average or above average. Many children even prefer games in which they need to apply logical thinking and knowledge about the world around them. In rare cases, children with Asperger's syndrome have disorders such as dyslexia and dyspraxia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, epilepsy.

Correction program at the Akme Center

Children with Asperger's syndrome differ little from ordinary children: they have the same rich imagination, they strive to communicate and learn about the world around them, but it is difficult for them to establish contact with other people. The task of our specialists is to overcome these difficulties, to explain to the child the peculiarities of children's thinking and the differences from his thinking, to help realize abilities and talents. nine0003

The task of our specialists is to overcome these difficulties, to explain to the child the peculiarities of children's thinking and the differences from his thinking, to help realize abilities and talents. nine0003

Diagnostics. First of all, we conduct a diagnostic consultation to identify the problem, to understand the characteristics of the character, thinking and physical development of the child. A neurologist talks to the child and parents, sometimes other specialists take part in the consultation: defectologist, speech therapist, psychotherapist, clinical psychologist, osteopath and kinesiologist.

Correction. After consultation, the neurologist will draw up an individual correction program. Classes at the center include play therapy, art therapy, sand therapy and fairy tale therapy. We also carry out exercise therapy, osteopathic and kinesiology correction, classes with a speech therapist and psychotherapist. The number and frequency of classes will be selected by the neurologist depending on the characteristics of the child.