Anxiety depression and ocd

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drugs

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Misusing alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs can have both immediate and long-term health effects.The misuse and abuse of alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs, and prescription medications affect the health and well-being of millions of Americans. SAMHSA’s 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health reports that approximately 19.3 million people aged 18 or older had a substance use disorder in the past year.

Alcohol

Data:

- In 2020, 50.0% of people aged 12 or older (or 138.5 million people) used alcohol in the past month (i.e., current alcohol users) (2020 NSDUH)

- Among the 138.5 million people who were current alcohol users, 61.

6 million people (or 44.4%) were classified as binge drinkers and 17.7 million people (28.8% of current binge drinkers and 12.8% of current alcohol users) were classified as heavy drinkers (2020 NSDUH)

6 million people (or 44.4%) were classified as binge drinkers and 17.7 million people (28.8% of current binge drinkers and 12.8% of current alcohol users) were classified as heavy drinkers (2020 NSDUH) - The percentage of people who were past month binge alcohol users was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (31.4%) compared with 22.9% of adults aged 26 or older and 4.1% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 (2020 NSDUH)

- The 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health reports that 139.7 million Americans age 12 or older were past month alcohol users, 65.8 million people were binge drinkers in the past month, and 16 million were heavy drinkers in the past month

- About 2.3 million adolescents aged 12 to 17 in 2019 drank alcohol in the past month, and 1.2 million of these adolescents binge drank in that period (2019 NSDUH)

- Approximately 14.5 million people age 12 or older had an alcohol use disorder (2019 NSDUH)

- Excessive alcohol use can increase a person’s risk of stroke, liver cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis, cancer, and other serious health conditions

- Excessive alcohol use can also lead to risk-taking behavior, including driving while impaired.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that 29 people in the United States die in motor vehicle crashes that involve an alcohol-impaired driver daily

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that 29 people in the United States die in motor vehicle crashes that involve an alcohol-impaired driver daily

Programs/Initiatives:

- STOP Underage Drinking interagency portal - Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Prevention of Underage Drinking

- Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Prevention of Underage Drinking

- Talk. They Hear You.

- Underage Drinking: Myths vs. Facts

- Talking with your College-Bound Young Adult About Alcohol

Relevant links:

- National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors

- Department of Transportation Office of Drug & Alcohol Policy & Compliance

- Alcohol Policy Information Systems Database (APIS)

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Tobacco

Data:

- In 2020, 20.7% of people aged 12 or older (or 57.

3 million people) used nicotine products (i.e., used tobacco products or vaped nicotine) in the past month (2020 NSDUH)

3 million people) used nicotine products (i.e., used tobacco products or vaped nicotine) in the past month (2020 NSDUH) - Among past month users of nicotine products, nearly two thirds of adolescents aged 12 to 17 (63.1%) vaped nicotine but did not use tobacco products. In contrast, 88.9% of past month nicotine product users aged 26 or older used only tobacco products (2020 NSDUH)

- Data from the 2019 NSDUH reports that 58.1 million people were current (i.e., past month) tobacco users. Specifically, 45.9 million people aged 12 or older in 2019 were past month cigarette smokers (2019 NSDUH)

- Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death, often leading to lung cancer, respiratory disorders, heart disease, stroke, and other serious illnesses. The CDC reports that cigarette smoking causes more than 480,000 deaths each year in the United States

- The CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health reports that more than 16 million Americans are living with a disease caused by smoking cigarettes

Electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use data:

- Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2020 National Youth Tobacco Survey.

Among both middle and high school students, current use of e-cigarettes declined from 2019 to 2020, reversing previous trends and returning current e-cigarette use to levels similar to those observed in 2018

Among both middle and high school students, current use of e-cigarettes declined from 2019 to 2020, reversing previous trends and returning current e-cigarette use to levels similar to those observed in 2018 - E-cigarettes are not safe for youth, young adults, or pregnant women, especially because they contain nicotine and other chemicals

Resources:

- Tips for Teens: Tobacco

- Tips for Teens: E-cigarettes

- Implementing Tobacco Cessation Programs in Substance Use Disorder Treatment Settings

- Synar Amendment Program

Links:

- Truth Initiative

- FDA Center for Tobacco Products

- CDC Office on Smoking and Health

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Tobacco, Nicotine, and E-Cigarettes

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: E-Cigarettes

Opioids

Data:

- Among people aged 12 or older in 2020, 3.4% (or 9.5 million people) misused opioids in the past year.

Among the 9.5 million people who misused opioids in the past year, 9.3 million people misused prescription pain relievers and 902,000 people used heroin (2020 NSDUH)

Among the 9.5 million people who misused opioids in the past year, 9.3 million people misused prescription pain relievers and 902,000 people used heroin (2020 NSDUH) - An estimated 745,000 people had used heroin in the past year, based on 2019 NSDUH data

- In 2019, there were 10.1 million people age 12 or older who misused opioids in the past year. The vast majority of people misused prescription pain relievers (2019 NSDUH)

- An estimated 1.6 million people aged 12 or older had an opioid use disorder based on 2019 NSDUH data

- Opioid use, specifically injection drug use, is a risk factor for contracting HIV, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C. The CDC reports that people who inject drugs accounted for 9 percent of HIV diagnoses in the United States in 2016

- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Understanding the Epidemic, an average of 128 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose

Resources:

- Medication-Assisted Treatment

- Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit

- TIP 63: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder

- Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings

- Opioid Use Disorder and Pregnancy

- Clinical Guidance for Treating Pregnant and Parenting Women With Opioid Use Disorder and Their Infants

- The Facts about Buprenorphine for Treatment of Opioid Addiction

- Pregnancy Planning for Women Being Treated for Opioid Use Disorder

- Tips for Teens: Opioids

- Rural Opioid Technical Assistance Grants

- Tribal Opioid Response Grants

- Provider’s Clinical Support System - Medication Assisted Treatment Grant Program

Links:

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Opioids

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Heroin

- HHS Prevent Opioid Abuse

- Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America

- Addiction Technology Transfer Center (ATTC) Network

- Prevention Technology Transfer Center (PTTC) Network

Marijuana

Data:

- The percentage of people who used marijuana in the past year was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (34.

5%) compared with 16.3% of adults aged 26 or older and 10.1% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 (2020 NSDUH)

5%) compared with 16.3% of adults aged 26 or older and 10.1% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 (2020 NSDUH) - 2019 NSDUH data indicates that 48.2 million Americans aged 12 or older, 17.5 percent of the population, used marijuana in the past year

- Approximately 4.8 million people aged 12 or older in 2019 had a marijuana use disorder in the past year (2019 NSDUH)

- Marijuana can impair judgment and distort perception in the short term and can lead to memory impairment in the long term

- Marijuana can have significant health effects on youth and pregnant women.

Resources:

- Know the Risks of Marijuana

- Marijuana and Pregnancy

- Tips for Teens: Marijuana

Relevant links:

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Marijuana

- Addiction Technology Transfer Centers on Marijuana

- CDC Marijuana and Public Health

Emerging Trends in Substance Misuse:

- Methamphetamine—In 2019, NSDUH data show that approximately 2 million people used methamphetamine in the past year.

Approximately 1 million people had a methamphetamine use disorder, which was higher than the percentage in 2016, but similar to the percentages in 2015 and 2018. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Data shows that overdose death rates involving methamphetamine have quadrupled from 2011 to 2017. Frequent meth use is associated with mood disturbances, hallucinations, and paranoia.

Approximately 1 million people had a methamphetamine use disorder, which was higher than the percentage in 2016, but similar to the percentages in 2015 and 2018. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Data shows that overdose death rates involving methamphetamine have quadrupled from 2011 to 2017. Frequent meth use is associated with mood disturbances, hallucinations, and paranoia. - Cocaine—In 2019, NSDUH data show an estimated 5.5 million people aged 12 or older were past users of cocaine, including about 778,000 users of crack. The CDC reports that overdose deaths involving have increased by one-third from 2016 to 2017. In the short term, cocaine use can result in increased blood pressure, restlessness, and irritability. In the long term, severe medical complications of cocaine use include heart attacks, seizures, and abdominal pain.

- Kratom—In 2019, NSDUH data show that about 825,000 people had used Kratom in the past month. Kratom is a tropical plant that grows naturally in Southeast Asia with leaves that can have psychotropic effects by affecting opioid brain receptors.

It is currently unregulated and has risk of abuse and dependence. The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that health effects of Kratom can include nausea, itching, seizures, and hallucinations.

It is currently unregulated and has risk of abuse and dependence. The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that health effects of Kratom can include nausea, itching, seizures, and hallucinations.

Resources:

- Tips for Teens: Methamphetamine

- Tips for Teens: Cocaine

- National Institute on Drug Abuse

More SAMHSA publications on substance use prevention and treatment.

Last Updated: 04/27/2022

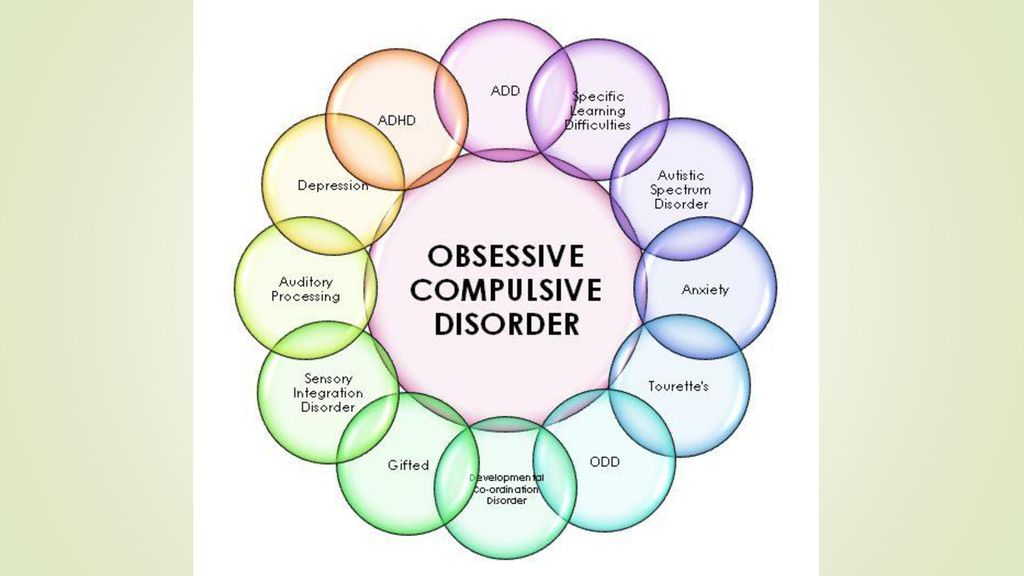

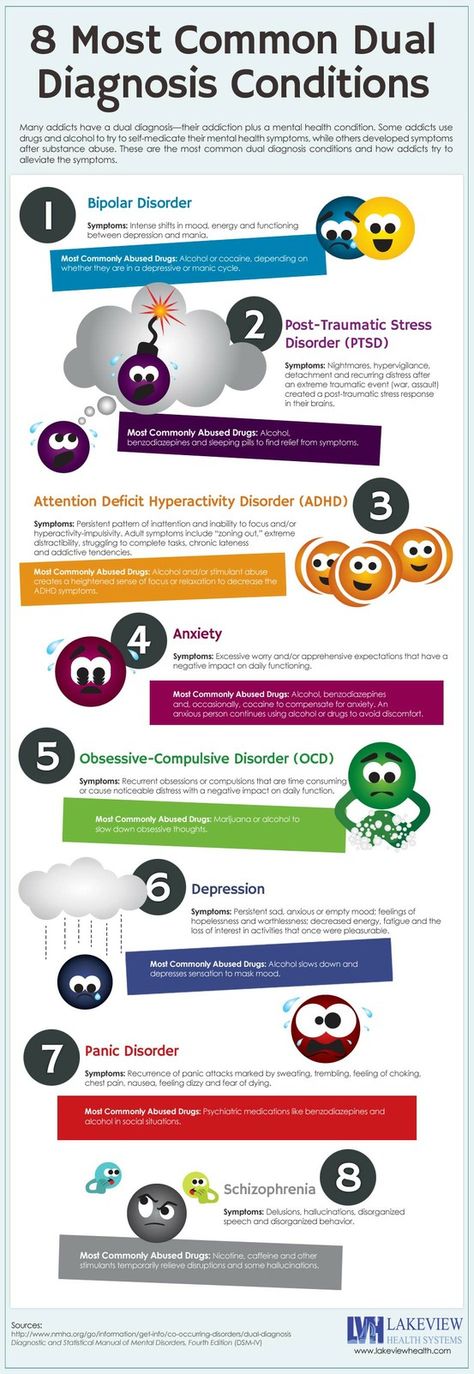

Depressive obsessive-compulsive disorder //Psychological newspaper

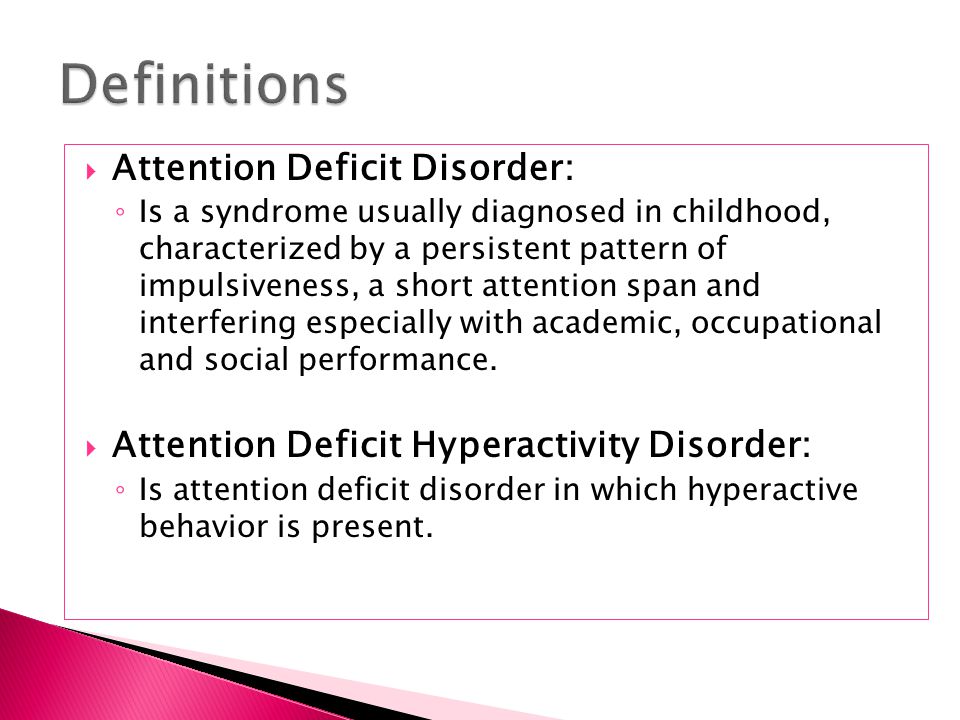

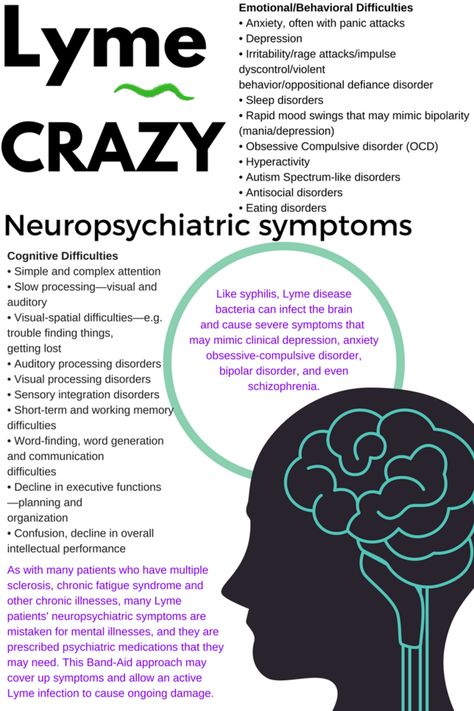

Obsessive-compulsive disorder presents a particular difficulty in diagnosis. This is because the main, root causes of this disease can be quite different. The main issue is associated with the so-called register-dependent obsessive symptoms (obsessive thoughts and actions), which qualitatively vary depending on the course of the main disease. That is, for example, if obsessions are caused by a personality disorder, then personality disorders will be paramount, and obsessions or compulsions will be secondary. If obsessive thoughts are caused by neurosis, then psychotrauma is considered as the main problem, and obsessive symptoms are only an “echo”, a secondary component. There is reason to believe that obsessions also appear during depression, and obsessions and compulsions in this case will acquire special qualitative colors.

If obsessive thoughts are caused by neurosis, then psychotrauma is considered as the main problem, and obsessive symptoms are only an “echo”, a secondary component. There is reason to believe that obsessions also appear during depression, and obsessions and compulsions in this case will acquire special qualitative colors.

The depressive register of OCD, or OCD depression, is relatively poorly understood from the point of view of the general theory of obsessive thoughts. As follows from the definition of mild depression, to diagnose it, it is enough to define the “Beck triad”: a negative image of oneself, a negative image of the world and a negative image of the future. With more serious degrees of depression, one has to take into account the diversity of the depressive syndrome. In this case, melancholic and suicidal thoughts, apathy, depressed mood, "powerlessness" with manifestations of asthenia, vegetative reactions with anxiety are often observed. The main question that arises when analyzing the mental state of such people is an attempt to understand why the depressive process is self-sufficient and stable. Particular attention is also drawn to the hypothesis that the course of thought processes in this disease becomes excessively cyclical. At the same time, previously normal thoughts begin to undergo various transformations, and also change a number of their qualities - they become obsessive.

Particular attention is also drawn to the hypothesis that the course of thought processes in this disease becomes excessively cyclical. At the same time, previously normal thoughts begin to undergo various transformations, and also change a number of their qualities - they become obsessive.

It is assumed that there are a number of still little-known mechanisms that can change the register of obsessions, and can also significantly complicate the course and treatment of obsessions and compulsions. This can be explained by the example of the “transition” of neurotic obsessive thoughts into depressive ones. For example, a person cannot overcome any difficult life situation, and this leads him to extreme stress. After some time, certain changes seem to occur, life is gradually getting better, but memories of the crisis form obsessive unpleasant memories that are distinguished by egodistonism (contrary to the ego). This is the neurotic register of obsessive thoughts. Let us assume that further various crisis situations are repeated in the above-mentioned person, there are more and more psychotraumas. And looped egodistonism (not accepting any failures in the past) begins to transform into a generalized negative image of the outside world. That is, the usual egodyston process evolved not only into non-acceptance of oneself, but also into an obsessive rejection of the whole picture of reality. One of the components of Beck's depressive triad appears. The subsequent attachment of ego-synthonicity in relation to one's own negative image gives rise to self-accusations (the second component of the triad is a negative image of oneself). Attempts to predict the future under such circumstances lead to obsessive thoughts that even after a long period of time nothing will change for the better. The result of this whole process is the transition of obsessions from the neurotic to the depressive register, with qualitative changes both in the repetition cycles and in the semantic plots themselves. In other words, the entire Beck triad listed above can be considered depressive intrusive thoughts in OCD depression.

And looped egodistonism (not accepting any failures in the past) begins to transform into a generalized negative image of the outside world. That is, the usual egodyston process evolved not only into non-acceptance of oneself, but also into an obsessive rejection of the whole picture of reality. One of the components of Beck's depressive triad appears. The subsequent attachment of ego-synthonicity in relation to one's own negative image gives rise to self-accusations (the second component of the triad is a negative image of oneself). Attempts to predict the future under such circumstances lead to obsessive thoughts that even after a long period of time nothing will change for the better. The result of this whole process is the transition of obsessions from the neurotic to the depressive register, with qualitative changes both in the repetition cycles and in the semantic plots themselves. In other words, the entire Beck triad listed above can be considered depressive intrusive thoughts in OCD depression..jpg)

Thus, the understanding of the phenomena of melancholia, depression, self-accusation and suicidality itself becomes systemic, and, therefore, several methodological levels can already be distinguished (Beck's theory and the general theory of obsessive thoughts) at which these processes can be analyzed, slowed down or stopped. It is important to understand obsessions as unique mechanisms inherent in all mental disorders or illnesses, the main purpose of which is seen as ensuring the stability of unbalanced pathological processes .

That is, for the psyche and streams of consciousness (thoughts), the primary task will not be to ensure complete recovery, but fixation (looping) on a more or less stable functional state. All this happens to prevent further complications of various mental illnesses.

Depressive OCD or OCD depression is characterized by a number of specific features. In particular, the characteristics of the course of different syndromes may indicate several registries of mental illness. For example, an anxious and depressive background will most likely indicate disturbances in the work of the autonomic nervous system, as well as depression itself (“two registers work” - vegetative and depressive). In this case, in addition to the obsessive Beck triad, panic attacks can also occur. But the most common combination can be considered a neurosis and a depressive episode (two registers - neurotic and depressive). In this situation, intrusive memories will reinforce the obsessions of self-accusation, self-abasement and other melancholic obsessions. What is especially interesting, in the framework of the register analysis of obsessions and compulsions, we can assume that the neurotic register of obsessive thoughts can turn into a depressive one, or two registers will be observed in the clinical picture at once (respectively, we will observe signs of a depressive-neurotic syndrome).

For example, an anxious and depressive background will most likely indicate disturbances in the work of the autonomic nervous system, as well as depression itself (“two registers work” - vegetative and depressive). In this case, in addition to the obsessive Beck triad, panic attacks can also occur. But the most common combination can be considered a neurosis and a depressive episode (two registers - neurotic and depressive). In this situation, intrusive memories will reinforce the obsessions of self-accusation, self-abasement and other melancholic obsessions. What is especially interesting, in the framework of the register analysis of obsessions and compulsions, we can assume that the neurotic register of obsessive thoughts can turn into a depressive one, or two registers will be observed in the clinical picture at once (respectively, we will observe signs of a depressive-neurotic syndrome).

As mentioned above, depressive obsessions can be recognized not only by syndromatic signs. Depression transforms the neurotic obsession into egodystonic and egosynthonic elements. In particular, selfishness is associated with self-accusations (a person does not even have reasonable self-criticism that he is not really to blame for all his troubles and troubles in the world - the disease itself forms a strong sense of guilt), and selfishness manifests itself in a negative image of the outside world (not accepting and not understanding a number of his instincts, drives, needs and motives, a person begins to consider the external environment as something alien, hostile, strange). The above reflections and conclusions speak in favor of the fact that the obsessions of any register, including the depressive one, quite strongly affect the "ego", "id" and "superego" of the individual.

Depression transforms the neurotic obsession into egodystonic and egosynthonic elements. In particular, selfishness is associated with self-accusations (a person does not even have reasonable self-criticism that he is not really to blame for all his troubles and troubles in the world - the disease itself forms a strong sense of guilt), and selfishness manifests itself in a negative image of the outside world (not accepting and not understanding a number of his instincts, drives, needs and motives, a person begins to consider the external environment as something alien, hostile, strange). The above reflections and conclusions speak in favor of the fact that the obsessions of any register, including the depressive one, quite strongly affect the "ego", "id" and "superego" of the individual.

Quite relevant is the question of how good the level of awareness of depressive obsessions and compulsions will be in comparison with their other varieties. Here we should pay attention to the fact that neurotic obsessions are reflected much better, since in this case the personality, as it were, is fighting against itself. In depressive OCD, the situation is aggravated by the fact that adequate self-criticism is suppressed here by various cognitive distortions, in particular, catastrophization, as well as strong emotions of guilt. Sometimes the individual himself defends his own irrational conclusions about his own worthlessness, the absolute negativity of the world around him and the supposedly “gloomy future”. Beck's triad as a special obsessive formation makes a person return to melancholic thoughts again and again and does not allow switching to more constructive strategies. Moreover, the presence of a vegetative register of obsessions in addition to the depressive one can contribute to more serious risks of developing suicides.

In depressive OCD, the situation is aggravated by the fact that adequate self-criticism is suppressed here by various cognitive distortions, in particular, catastrophization, as well as strong emotions of guilt. Sometimes the individual himself defends his own irrational conclusions about his own worthlessness, the absolute negativity of the world around him and the supposedly “gloomy future”. Beck's triad as a special obsessive formation makes a person return to melancholic thoughts again and again and does not allow switching to more constructive strategies. Moreover, the presence of a vegetative register of obsessions in addition to the depressive one can contribute to more serious risks of developing suicides.

Like neurotic intrusive memories, depressive obsessions organize themselves into steady and stable recurring cycles. Therefore, the chronicity of OCD neurosis and OCD depression is quite high. However, the pace of the stream of consciousness is different here. With obsessive psychotraumatic experiences, thoughts can arise quickly, their very appearance is often illogical and non-associative. At the same time, obsessions of the depressive register may not be of high intensity, but they slowly fetter consciousness, reduce attention and memory. Slow "mental stirrers" and "mental chewing gums" - ruminations - can become commonplace here.

At the same time, obsessions of the depressive register may not be of high intensity, but they slowly fetter consciousness, reduce attention and memory. Slow "mental stirrers" and "mental chewing gums" - ruminations - can become commonplace here.

You can also notice certain differences at the level of psychosomatics. Disturbing neurotic memories can cause various autonomic disorders (excessive sweating, tachycardia, frequent urination, nervous functional gastritis, cholecystitis, etc.). In turn, depressive obsessions can often be accompanied by asthenia, “powerlessness”, increased fatigue, etc. Quite complex and specially structured psychosomatics can be observed with the simultaneous presence of both neurotic and depressive obsessions. Among the sensory phenomena characteristic of OCD-depressions, it is possible to single out absent-mindedness, a decrease in attention with intensified attempts to stabilize it, and consciousness, as it were, loses its “focus”. It should also be taken into account that a neurotic obsession is a traumatic emotional experience or memory invading consciousness. In turn, depressive obsession is a cyclical repetition of destructive attitudes, which are based on the Beck triad. In both cases, getting rid of this kind of thoughts on your own can be quite difficult.

In turn, depressive obsession is a cyclical repetition of destructive attitudes, which are based on the Beck triad. In both cases, getting rid of this kind of thoughts on your own can be quite difficult.

The above features of depressive obsessions help to better understand the phenomenon of depression. At this stage, we can not only study melancholia and depression at the level of Beck's cognitive-behavioral theories, but also connect both syndromatic (psychiatric) and register theoretical developments of the general theory of obsessive thoughts (medical psychology). Combining all of the above approaches into a single analytical framework can contribute to a better understanding of the nature of depression.

It should also point out the potential for a new look at psychotherapeutic interventions for depressive episodes and OCDs. The most interesting and relevant direction may be the rethinking of cognitive behavioral therapy, taking into account the fact that obsessive thoughts in several registers require special, innovative approaches for correction. In itself, the interaction of several diseases - neurosis and depression, as well as neurotic disorders with vegetative ones - these are systemic aspects that have not yet been studied enough in psychology and psychiatry. Therefore, the ability to distinguish between different obsessions can be a serious help for the study of new preventive and therapeutic methodologies, methods and techniques.

In itself, the interaction of several diseases - neurosis and depression, as well as neurotic disorders with vegetative ones - these are systemic aspects that have not yet been studied enough in psychology and psychiatry. Therefore, the ability to distinguish between different obsessions can be a serious help for the study of new preventive and therapeutic methodologies, methods and techniques.

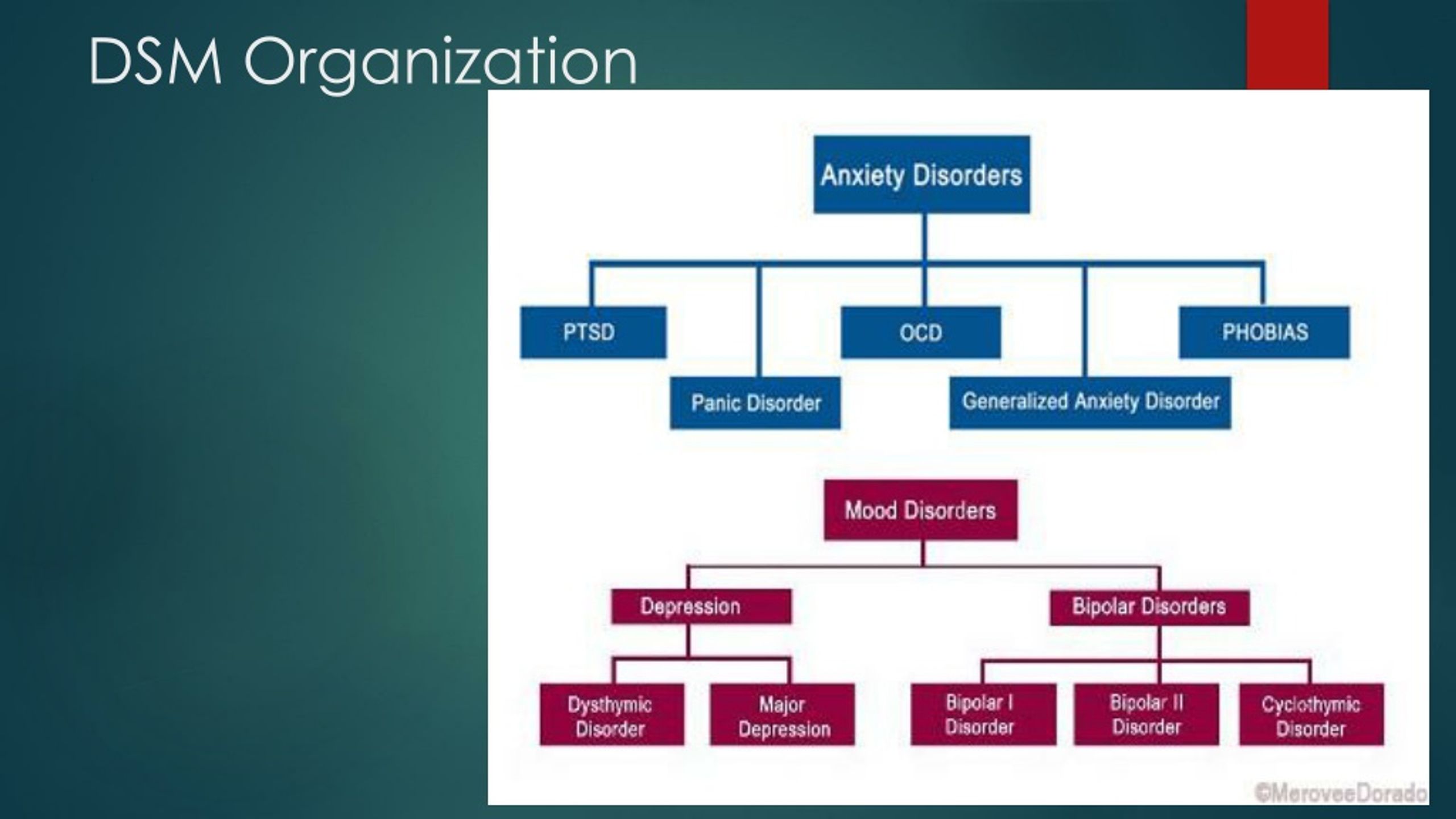

- International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. In 3 vols. T. 1. - Tenth revision. - Geneva: World Health Organization, 1995. - 697 p.

- Diagnostic and manual statistical of mental disorders (DSM-IV). — Forth Edition. - Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 1994. - 915 p.

- Diagnostic and manual statistical of mental disorders. Text revision (DSM-IV-TR). — Forth Edition. - Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 2000. - 943 p.

- Diagnostic and manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. — Fifth edition. - Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

- 970 p.

- 970 p.

the problem of typology and constitutional predisposition

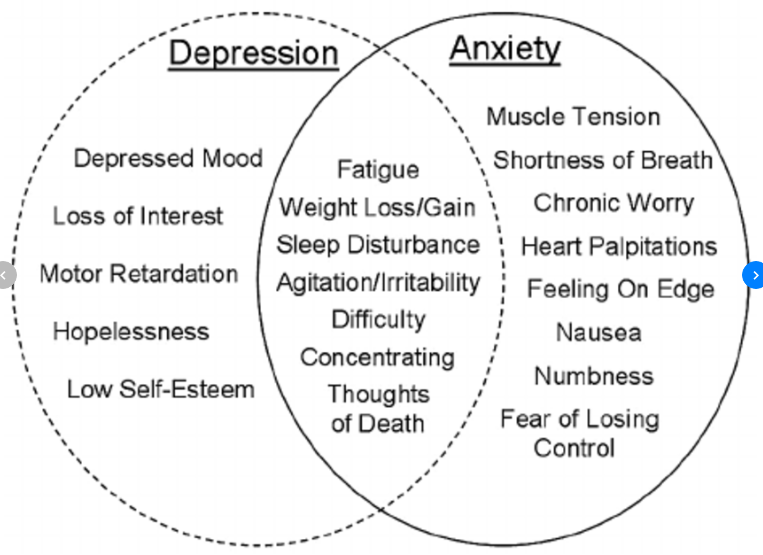

Anxious depression is one of the key problems of modern clinical psychiatry in pathogenetic and methodological aspects. Its scale and relevance is evidenced by the fact that the very phenomenon of anxious depression goes beyond the status of a medical problem, affecting the deepest aspects of human existence associated with the saturation of modern life with stressful events and other negative social trends, which leads to an exponential increase in the frequency of depressions (including anxiety disorders). ).

Clinical observations are of particular importance in modern conditions, indicating a modification of the psychopathological manifestations of depression: typical phenomena can be relegated to the background or completely replaced by anxious equivalents [17, 21, 25, 29, 59, 136].

The multiplicity of links between anxiety and depression raises a number of questions about the nature, boundaries and clinical unity of anxious depression as an independent psychopathological entity (cohesive entity), the legitimacy of including both autochthonous conditions and reactions to stressful influences in this group. In this series, the questions of assessing the relationship between anxiety-depressive disorder and the personality of the patient in whom this disorder is formed remain the least studied (the ratio of anxiety depression - personality disorders is covered in the second part of this review).

In this series, the questions of assessing the relationship between anxiety-depressive disorder and the personality of the patient in whom this disorder is formed remain the least studied (the ratio of anxiety depression - personality disorders is covered in the second part of this review).

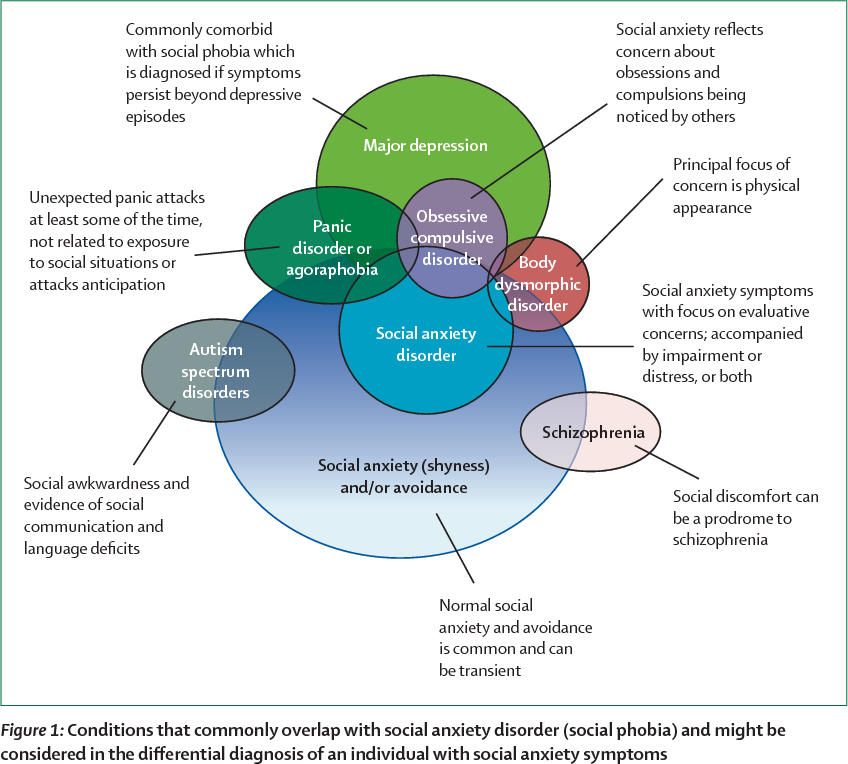

In existing classifications (ICD-10, DSM-IV-TR), depressive disorders are separated from anxiety disorders as independent categories. Within the latter, coexisting depressive and anxiety disorders can be presented not only in the form of developed psychopathologically completed syndromes, but also in subthreshold, subsyndromal, masked forms.

A significant contribution of anxiety to the structure of depression, judging by the data of Russian [15, 19] and foreign [164, 196, 213] authors, seems indisputable, but the existence of anxious depression as an independent clinical (and taxonomic) unit is the subject of discussion. This problem is considered in this review in two sections, the first of which is devoted to the question of the unity/heterogeneity of anxious depression, and the second - to its relationship with personality disorders.

Anxious depression - etiopathogenetic and clinical unity or a heterogeneous disorder?

The development of the problem in the title of this section is carried out in different research traditions, which can be reduced to two main directions: one of them is based on the concept of psychogenesis (psychoanalysis, psychodynamic psychiatry, behavioral, cognitive psychology), the other - on the natural science paradigm of depression (epidemiology, genetics, neurobiology, clinic).

In the studies of the first direction, the authors [54, 71, 80, 114], who adhere to the psychoanalytic [90], behavioral [185], and psychological [58] interpretations of mental disorders, qualify anxiety and depression as closely related phenomena. The latter are determined by universal mechanisms existing initially or acquired in the process of modeling learned behavioral patterns and/or cognitive schemes. This provides protection from suppressed unconscious impulses and / or stressful influences that pose a threat and reduce adaptive resources and the ability to control the situation. From here the consciousness of helplessness and hopelessness is derived (in these terms, researchers describe the picture of depression) [1] .

From here the consciousness of helplessness and hopelessness is derived (in these terms, researchers describe the picture of depression) [1] .

Let us now turn to the work based on the medical model of depression.

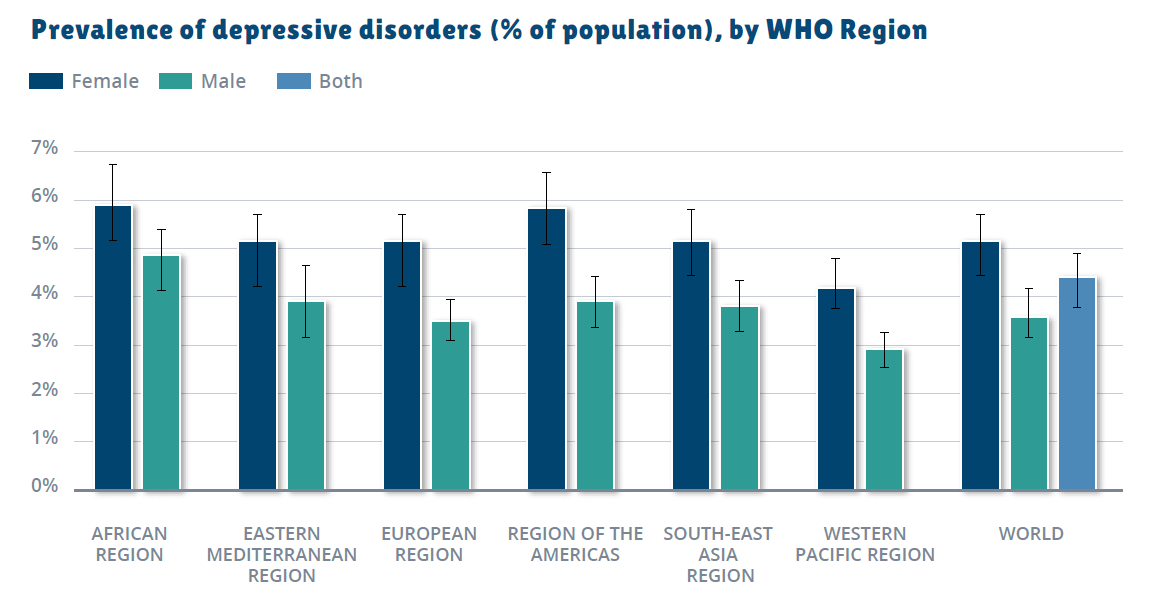

The results of epidemiological studies based on the principles of modern evidence-based medicine suggest that there are statistically significant positive correlations between the categories "depression" and "anxiety" [83].

Since the late 80s - early 90s of the last century, high rates of comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders have been established. The prevalence of conditions in the structure of which a combination of typical depressive (low mood, lethargy, pessimism) and anxiety (tension, insomnia, irritability) symptoms are detected exceeds the frequency of “pure” depressions in the ratio of 7:1 in the UK population [157]. According to L. Andrade et al. [50], the combination of major depression and panic disorder occurs 11 times more often than each of these forms of pathology, and the role of the comorbidity factor is manifested by the aggravation of both syndromes, and, in particular, by an increase (almost 3-fold [109, 126]) hospitalization rates, risk of relapse and suicide attempts, and reduced psychosocial functioning and quality of life [50, 202, 211]. At the same time, the values of comorbidity indicators vary widely - from 22 to 91% [73, 76, 153, 195].

At the same time, the values of comorbidity indicators vary widely - from 22 to 91% [73, 76, 153, 195].

In later works, the average value of the discussed indicator is 58% [109, 126]. The fact of a high comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders is confirmed by the results of a large-scale epidemiological study (7076 observations) performed by R. de Graaf et al. [81] in the framework of the national program for the study of mental health of the population of the Netherlands. Anxiety disorders are detected in 46% of men and 57% of women (aged 18 to 64 years) with an affective pathology diagnosed during their lifetime (lifetime prevalence). Similar results are reported in a US epidemiological series (NESARC, NCS-R) [2] , performed using the method of sequential analysis of time series (time-series analyzes) and allowing to estimate the prevalence of the studied comorbid disorders during life (lifetime prevalence) [97-99, 126-131] [3] .

As assessed by D. Hasin et al. [102] (NESARC program) the proportion of generalized anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder - GAD), comorbid major depression is 71%, and in the reverse assessment (from anxiety to depression) - 90% [97]. According to another longitudinal American project - NCS-R (9982 English-speaking respondents aged 18 years and older, examined using the WHO structured diagnostic interview - CIDI) [126, 130, 212], the comorbidity of depression with various subtypes of anxiety disorders - social phobias, simple phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, panic attacks are respectively 28, 25, 17, 16 and 10%. The comorbidity rate of generalized anxiety with major depression is estimated at 62%; in panic disorder, 35% of patients develop major depression, and another 10% develop dysthymia.

Hasin et al. [102] (NESARC program) the proportion of generalized anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder - GAD), comorbid major depression is 71%, and in the reverse assessment (from anxiety to depression) - 90% [97]. According to another longitudinal American project - NCS-R (9982 English-speaking respondents aged 18 years and older, examined using the WHO structured diagnostic interview - CIDI) [126, 130, 212], the comorbidity of depression with various subtypes of anxiety disorders - social phobias, simple phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, panic attacks are respectively 28, 25, 17, 16 and 10%. The comorbidity rate of generalized anxiety with major depression is estimated at 62%; in panic disorder, 35% of patients develop major depression, and another 10% develop dysthymia.

Analysis of data from the Zurich study from 1979-1999 allowed J. Angst et al. [52] state that GAD is statistically significantly associated (odds ratio - OR [4] - is 2. 6 - 7.4; mean 4.3) with bipolar affective disorder (BAD) [5] - GAD overlaps with BAD type II in 32.4% of cases. In a later work performed with the participation of J. Angst [158], this representation is extrapolated to the relationship of GAD with BAD type I: in these cases, the OR averages 9.4 with a spread of values of this indicator 6.2-14.2. A. Ruscio et al. [179, 180] (NCS-R project) specify the shares of BAD in patients with other subtypes of anxiety disorders: obsessive-compulsive - 23.4%, sociophobic - 13.8%.

6 - 7.4; mean 4.3) with bipolar affective disorder (BAD) [5] - GAD overlaps with BAD type II in 32.4% of cases. In a later work performed with the participation of J. Angst [158], this representation is extrapolated to the relationship of GAD with BAD type I: in these cases, the OR averages 9.4 with a spread of values of this indicator 6.2-14.2. A. Ruscio et al. [179, 180] (NCS-R project) specify the shares of BAD in patients with other subtypes of anxiety disorders: obsessive-compulsive - 23.4%, sociophobic - 13.8%.

The results of the epidemiological studies discussed above extend to empirical experience both in the psychiatric hospital and in primary care settings. According to a special study assessing the prevalence of depression with anxiety disorders in hospitalized patients (429observations) [209], this figure is estimated at 49%, which reflects the significant contribution of such forms to the structure of affective disorders. In general medicine, rates of comorbidity between depression and anxiety exceed those estimated for a specialized network: more than 75% of patients in this cohort diagnosed with major depression also have a current anxiety disorder [167, 182].

Analysis of depression and anxiety disorders in the context of chronological comorbidity [77, 82] has led to the concept that anxiety is considered as a predictive validator [6] major depression. In accordance with this concept, the formation of anxiety precedes and increases the risk of developing depression, acquiring special significance when exposed to stressful events [105, 107].

There is also a point of view about the existence of a common neurotic factor between depression and anxiety (“general distress factor” [200, 201]), the impact of which is provided by common mechanisms responsible for vulnerability to stress. This universal factor, represented in the dimensional model [75, 204] as a deficit of positive emotionality and anxiety with an increased readiness to respond to stress (hyperarousal), becomes the driving force that triggers negative affect. Under such conditions, the role of significant stressors (interpersonal conflict, some forms of loss, and other life shocks) is reduced to identifying anxiety that manifests itself at the clinical level [70, 79, 87, 174]. Anxiety itself, in turn, can act as an additional decompensating stressor that aggravates (especially in patients with a genetic/family predisposition) the manifestations of major depression.

Anxiety itself, in turn, can act as an additional decompensating stressor that aggravates (especially in patients with a genetic/family predisposition) the manifestations of major depression.

The results of etiopathogenetic studies on the analysis of hereditary biological relationships between anxiety and depression (genealogical, familial, twin, population, molecular genetic) allow us to put forward the concept of general genetic diathesis. This concept is supported by comparative data on a high aggregation of anxiety and depressive disorders among first-degree relatives (parents, non-twin siblings) in samples of probands diagnosed with depression or anxiety disorder [121, 193] [7] . Such a relationship is revealed within several generations. A unique series of clinical genetic studies was carried out by K. Kendler [117, 119, 120, 124] based on the Virginia population register. Its genealogical section included 5,877 probands and 10,331 parents, which made it possible to identify indicators of family aggregation of major depression and generalized anxiety and statistically significant correlations ( p <0. 001; OR=1.88) between the studied traits.

001; OR=1.88) between the studied traits.

The discussed genealogical concept is supported by the authors of works performed by the twin method [107, 155, 175]. In particular, in the twin section of the Virginia program by K. Kendler in [117, 118, 122, 123, 125], performed using modern statistical approaches (multivariate twin modeling, etc.), genetic correlations for such factors as participation of additive genes (the contribution of the latter is 2 times higher in monozygotic pairs), the role of environmental factors and conditions of individual development (their effect is equivalent). The position of the authors is to confirm the existence of an internal, environmentally independent genetic risk that determines the correlation of hereditary mechanisms of major depression and “anxious misery” [106, 107, 125], which makes it possible to assess anxious depression as a clinically significant phenotype. [155, 160] [8] .

The fact that the comorbidity of major depression with anxiety disorders is based on the existence of proven precursor/antecedent validators reflecting the hereditary affinity of anxiety and depression allows geneticists and authors of basic research in other areas of neuroscience [9] to join the proposal to distinguish anxiety depression in as a separate category [96, 107, 155], put forward in the preparation of the draft DSM -V [10] .

Turning to the discussion of the problem of the unity of anxiety and depression in the clinical aspect, it must be emphasized that the difficulties associated with the analysis of the problem in this aspect are largely due to the uncertainty in the definitions of anxiety as a psychophysiological mechanism of adaptive response to external stimuli, anxiety as a characterological feature and disorganizing the general emotional-sensory tone and behavior of pathological anxiety, considered as a psychopathological formation.

According to researchers [22, 31], this kind of difficulty is associated with differences in understanding the boundaries and relationships between anxiety and depression. The interpretation of the relationship between these categories allows the following two possibilities.

As heterogeneous disorders, anxiety and depression can only be considered at the level of the borderline psychopathological register. Under these conditions, the existence of anxiety disorders (panic attacks, generalized anxiety, social phobias, etc. ) as an independent psychopathological formation seems to be an indisputable fact, but such independence is realized exclusively within the reactive (adaptive) states and dynamics of personality disorders (PD). When it comes to disorders of a more severe - affective register (recurrent, bipolar depression, dysthymia), anxiety and depression act in clinical unity.

) as an independent psychopathological formation seems to be an indisputable fact, but such independence is realized exclusively within the reactive (adaptive) states and dynamics of personality disorders (PD). When it comes to disorders of a more severe - affective register (recurrent, bipolar depression, dysthymia), anxiety and depression act in clinical unity.

The idea of such unity, “when difficulties arise, and sometimes the impossibility of distinguishing pure melancholy from pure anxiety at the psychopathological level” [23], is put forward by both Russian [3, 5, 16, 17, 22] and foreign [101, 140 -143, 146, 213] authors [11] . Accordingly, clinicians (Russian and foreign), recognizing the artificiality of the boundaries separating depressive and anxiety disorders into discrete categories, postulate the coexistence of two hypothymic (“cotymic” in the terminology of P. Tyrer [200]) affects - anxiety and depression within the psychopathological unity - anxious depression .

The developers of the latest version of the DSM recommended the introduction of the diagnostic rubric D05 "Mixed anxiety/depression". The presence of 3 or 4 symptoms of major depression (mandatory signs of low mood and/or anhedonia), combined with symptoms of anxiety distress, is singled out as verification criteria. The latter is defined as having two or more of the following symptoms: irrational (unmotivated) anxiety, preoccupation with painful thoughts, inability to relax, motor tension, fear or anticipation of a terrible event. The duration of symptoms is at least 2 weeks. Additional criterion: "The disorder cannot be diagnosed by the DSM as anxiety or depression, since both symptom complexes are realized simultaneously in its structure."

An attempt to revise the systematics of affective disorders with the integration of anxiety and depression within a single disorder, “panic-depressive illness” in the formulation of H. Akiskal [46], presented in the DSM-V project, is primarily based on the results of clinical studies.

Turning to the clinical characteristics of anxious depression, it should be noted a series of works performed by Australian researchers [69, 168, 169], which present the qualification of this form within the framework of non-melancholic depression. Among domestic authors V.N. Krasnov [17], based on the clinical characteristics and patterns of the course of anxiety-depressive states, argues that most of them can be attributed to non-melancholic depressions.

It should be emphasized that the publication of the article by M. Shimoda [187] laid the foundations for the activities of the Japanese National Psychiatric School [108, 189]. In the works of its representatives, a special type of anxious non-melancholic depressions is distinguished. In the description of M. Shimoda, in patients with such depressions, the mediation of depression and anxious symptoms is impaired - they, despite the appearance of neurasthenic (fatigue, insomnia) and affective disorders proper, continue to work until the depression reaches a complete psychopathological end. According to H. Hirasawa [108], along with “idle” activity, signs of somatized anxiety (a vegetative symptom complex including a feeling of lightheadedness, sleep disturbances), a feeling of self-doubt, guilt and shame towards others due to the inability to work are formed.

According to H. Hirasawa [108], along with “idle” activity, signs of somatized anxiety (a vegetative symptom complex including a feeling of lightheadedness, sleep disturbances), a feeling of self-doubt, guilt and shame towards others due to the inability to work are formed.

In German psychiatry, similar conditions were designated by K. Leonhard [144] as “self-torturing”, “hunted” depression, the clinical picture of which is dominated by phenomena of unmotivated (floating) anxiety up to agitation, obsessive fears, ideas of guilt (patients constantly condemn themselves for all kinds of misdemeanors).

As markers of non-melancholic depressions, the state corresponds to the subpsychotic register in the absence of distinct signs of vitality (loss of appetite and body weight, late insomnia, circadian rhythm), as well as anergy, unreactivity, anhedonia and psychomotor disorders. Non-melancholic depressions are associated with symptoms of reactive lability, personality disorders, and proceed with anxious anxiety (generalized/phobic anxiety, panic attacks, and other anxious disorders). Such conditions show an insufficient response to therapy and a tendency to chronicity (transformation into dysthymia).

Such conditions show an insufficient response to therapy and a tendency to chronicity (transformation into dysthymia).

As significant psychopathological features of anxiety depression occurring with panic attacks, phobias, generalized anxiety [49], the characteristics of anxiotic manifestations proper are considered. P. Kielholz [133] considered the vitalization of anxiety in the structure of anxious depression as a differentiating clinical sign that allows one to distinguish anxious disorders of an affective nature from psychogenic anxiety (associated with an object, arising as a result of real shocks and threats; existential - associated with a feeling of threat to existence due to circumstances, inability to cope with the test and - more broadly - life's problems). The author, and after him other researchers, trace the modification of anxiety in the course of the dynamics of anxious depressions, when specific fears or reactions to objective stimuli turn into “free floating” / floating anxiety, where objects are already random and multiple, and then - objectless, generalized anxiety, akin to depressive melancholy due to the vitalization of a pathologically reduced affect.

In Russian psychiatry O.P. Vertogradova et al. [2, 4], who put forward the concept of “affective pathoplasty of depressive symptoms and their correspondence to the nature of the dominant affect”, also emphasize the dynamism and tendency to vitalization of the anxious affect.

However, the data of a number of publications by domestic and foreign authors show that in the space of anxious depression, along with non-melancholic (self-torturing) anxiety-melancholic syndromes can be distinguished [12] .

It is necessary to note the historically established tradition in which such conditions are considered in the context of the nosological paradigm.

If E. Kraepelin [134], defining anxiety as “the most common form of unpleasant mental movements”, notes that this disorder is most often observed during the depressive phases of circular psychosis [13] , then E. Bleuler [64] gives a detailed description anxious depression. He singles out in the structure of depression, understood in the light of the teachings of E. Kraepelin, a distinctive phenomenon - dreary fear (schwermütig Angst), which, when anxiotic symptoms deepen to the level of agitation, can transform into delusional ideas. At the same time, E. Bleuler, referring to S. Freud, brings his term "floating anxiety" closer to his own - "free melancholy" (free-floating anxiety) - and emphasizes that depression with dreary fear is a relatively milder form of melancholia and can manifest itself not only a psychosis, but also a "neurotic anxiety neurosis." Yu.V. Cannabih [13]. At the same time, the author, and after him modern researchers [1, 8, 26, 33, 36, 41, 42, 49, 137] emphasize the connection between anxiety and suicidal risk - "the affect of fear ... often contributes to a sudden weakening and even the disappearance of lethargy, giving the patient the opportunity to implement a long-cherished thought of suicide."

Kraepelin, a distinctive phenomenon - dreary fear (schwermütig Angst), which, when anxiotic symptoms deepen to the level of agitation, can transform into delusional ideas. At the same time, E. Bleuler, referring to S. Freud, brings his term "floating anxiety" closer to his own - "free melancholy" (free-floating anxiety) - and emphasizes that depression with dreary fear is a relatively milder form of melancholia and can manifest itself not only a psychosis, but also a "neurotic anxiety neurosis." Yu.V. Cannabih [13]. At the same time, the author, and after him modern researchers [1, 8, 26, 33, 36, 41, 42, 49, 137] emphasize the connection between anxiety and suicidal risk - "the affect of fear ... often contributes to a sudden weakening and even the disappearance of lethargy, giving the patient the opportunity to implement a long-cherished thought of suicide."

An increase in anxious symptoms with a tense expectation of all sorts of misfortunes is accompanied by agitation, ideomotor agitation. Motor agitation with anxious verbigerations, aggravated by any change in the situation (symptom of adaptation disorder), may be manifested by partial phenomena of ideational retardation (wringing of fingers, restless hand movements with general immobility) - a symptom of adaptation disorder (Charpentier's phenomenon), or "anxious numbness" (" anxious retardation”, “silent anxiety” [1, 20]).

Motor agitation with anxious verbigerations, aggravated by any change in the situation (symptom of adaptation disorder), may be manifested by partial phenomena of ideational retardation (wringing of fingers, restless hand movements with general immobility) - a symptom of adaptation disorder (Charpentier's phenomenon), or "anxious numbness" (" anxious retardation”, “silent anxiety” [1, 20]).

Thus, as evidenced by the literature data and the own clinical experience of the authors of this review [31, 32, 38], there are two main types of anxiety depressions - non-melancholic/self-torturing and anxiety-melancholic.

If we try to generalize the relevant clinical descriptions, then the structure of each type of anxious depression, including pathologically altered affect, meaningful symptom complex, and comorbid anxiety-phobic formations, can be represented schematically (table) :

An analysis of the above studies allows us to conclude that there is a psychopathological (typological) heterogeneity of anxious non-melancholic depressions. These data provide a basis for raising the question of the genesis of such clinical heterogeneity. The information given in the literature allows us to suggest that the heterogeneity of the constitutional "soil" predisposing to one or another modus of affective response can be considered as a significant factor. In search of an answer to this question, let us turn to the analysis of the literature data presented in the second section of this review. At the same time, it is necessary to take into account changes in the initial theoretical positions on the basis of which the construction of diagnostic systems is carried out (at least in modern Western psychiatry) [14] .

These data provide a basis for raising the question of the genesis of such clinical heterogeneity. The information given in the literature allows us to suggest that the heterogeneity of the constitutional "soil" predisposing to one or another modus of affective response can be considered as a significant factor. In search of an answer to this question, let us turn to the analysis of the literature data presented in the second section of this review. At the same time, it is necessary to take into account changes in the initial theoretical positions on the basis of which the construction of diagnostic systems is carried out (at least in modern Western psychiatry) [14] .

Anxious depression - personality disorders (PD). Judging by the information given in the literature, the assessment of the ratio of depression, including anxiety (axis I in the DSM), with PD is carried out mainly in terms of affinity for deviations of the circle of the same name (in the DSM, along axis II, they are combined into an anxious-fearful cluster - cluster C, including anancaste / obsessive-compulsive, anxious / avoidant and dependent PD, which are assigned codes F60. 5 - F60.7 in the ICD-10, respectively).

5 - F60.7 in the ICD-10, respectively).

The existence of such an affinity is confirmed by epidemiological data, according to which, for anomalies of the anxiety-fearful cluster, the indicator of comorbidity with depression [15] reaches maximum values [176, 181, 186]. This conclusion follows from a comparison of the data given in other studies carried out in the late 80s of the last century. When studying samples of outpatients suffering from depressive disorders, the proportion of PD was estimated (according to DSM-III criteria) [176]. It turned out that the PD of cluster C (or traits of such a warehouse) make up a total of 67% versus 16% for cluster A (schizotypal, paranoid, schizoid) and 24% for cluster B (dissocial, borderline, narcissistic, histrionic PD). Some researchers [181, 186] cite lower, but comparable figures, according to which the RL of cluster A and B together make up 13–16%, the RL of cluster C, 32–36%, respectively.

The fact that depression predominates among persons with PD allocated within cluster C is also confirmed by the results obtained in recent years [156, 183, 192]. So, according to A. Skodol et al. [192], in a sample of 668 patients with depression, the proportion of PD ranked by categories of cluster C was 54.5% versus 15% for cluster A and 30.5% for B.

So, according to A. Skodol et al. [192], in a sample of 668 patients with depression, the proportion of PD ranked by categories of cluster C was 54.5% versus 15% for cluster A and 30.5% for B.

High personal anxiety, low self-esteem with hypersensitivity to rejection and the need for approval, conservatism, limited lifestyle and social activity - social phobia associated with evasion from potential dangers are distinguished as general diagnostic criteria for PD in this cluster.

Most of the works (they are more often made in the psychodynamic tradition using psychometric techniques) provide descriptions that, according to P. Chodoff [74], outline the features of the obsessive, anxious and dependent features of an abnormal personality predisposing to depression. The complex of these properties is distinguished by similarity with the common for all PD cluster C prototype - "obsessional neurotics" [44] [16] . This commonality is reflected by the following properties: meticulousness, adherence to routine, combined with caution, tension, and also "neurasthenicity". Similar features in the psychological concept of P. Janet [112] are interpreted as the result of a decrease in the intention (tension) of mental activity with a feeling of incompleteness, incompleteness of most thought processes. According to A.B. Smulevich [30, 31], the consciousness of such a flaw that gives rise to doubts is compensated by excessive conscientiousness with the desire to flawlessly perform any business, scrupulousness, exactingness. P. Matussek et al. [154] add to these characteristics the desire to avoid open conflicts, as well as emotional narrowness. M. Metcalfe [159] indicates a combination of such contrasting features as anxiety and tension, on the one hand, and rigidity, lack of imagination, sense of humor, adherence to habits, patterns [17] - on the other.

Similar features in the psychological concept of P. Janet [112] are interpreted as the result of a decrease in the intention (tension) of mental activity with a feeling of incompleteness, incompleteness of most thought processes. According to A.B. Smulevich [30, 31], the consciousness of such a flaw that gives rise to doubts is compensated by excessive conscientiousness with the desire to flawlessly perform any business, scrupulousness, exactingness. P. Matussek et al. [154] add to these characteristics the desire to avoid open conflicts, as well as emotional narrowness. M. Metcalfe [159] indicates a combination of such contrasting features as anxiety and tension, on the one hand, and rigidity, lack of imagination, sense of humor, adherence to habits, patterns [17] - on the other.

It should be emphasized that although a number of studies [92, 93, 203] have shown that anankastic (anxiety) depression occurring with obsessive-phobic disorders is preferably formed “on the basis of a compulsive temperament” (terminology of H. Akiskal et al. [ 45]), the ratio of anxiety depression - constitutional warehouse is considered outside the typological differentiation presented above (in the first section of this review). Accordingly, the clinical argumentation of the position according to which the PD of cluster C is assessed as a predictor of anxiety-related depression that will form in the future, and a depressive episode as a direct continuation of the abnormal premorbid warehouse, is based on the general characteristics of all personality anomalies attributed to the anxious-fearful cluster. However, from our point of view, this approach does not provide the possibility of a comprehensive analysis of the relationship under discussion, since it does not take into account the dichotomous subdivision of anxious depressions into anxiety-melancholic and self-torturing types.

Akiskal et al. [ 45]), the ratio of anxiety depression - constitutional warehouse is considered outside the typological differentiation presented above (in the first section of this review). Accordingly, the clinical argumentation of the position according to which the PD of cluster C is assessed as a predictor of anxiety-related depression that will form in the future, and a depressive episode as a direct continuation of the abnormal premorbid warehouse, is based on the general characteristics of all personality anomalies attributed to the anxious-fearful cluster. However, from our point of view, this approach does not provide the possibility of a comprehensive analysis of the relationship under discussion, since it does not take into account the dichotomous subdivision of anxious depressions into anxiety-melancholic and self-torturing types.

If we proceed from the opposite position, then, in accordance with the typology of anxious depressions, it is possible to single out two corresponding variants of the constitutional predisposition to the development of each of them.

The first of these types corresponds to P. Janet [111, 112] variant of psychasthenia traditionally identified in Russian psychiatry [9, 10, 28, 39, 43] as polar to psychasthenics (anancasts) - an anxious and suspicious character, first presented in the classic description of S.A. Sukhanov [35].

Evaluating the selected type of PD as one of the variants of psychasthenia (ie, a separate disease not associated with cyclothymia - psychoneurosis), the author at the same time considers the possibility of forming cyclothymic - mainly melancholic - phases on this "soil". Moreover, S.A. Sukhanov, as Yu.V. Kannabih [13], emphasizes the affinity of an anxious and suspicious nature with affective spectrum disorders. Interpreting the fact of exacerbation during the period of cyclothymic/melancholic depression of the main features of the psychasthenic mental state, the author points to "the homogeneity of the emotional tone of psychasthenia with the main emotional tone characteristic of cyclothymic depression" [13].

According to a number of characteristics, this variant overlaps with other cluster C anomalies and is combined with anxious/avoidant RL in modern taxonomy.

However, such a combination, as evidenced by our own clinical experience [32], results in the leveling of the anxious and suspicious warehouse as a special variant of avoiding PD, predisposing to the manifestation of depression, comparable to the picture of circular melancholia.

Observations by V.V. Chitlova [38], which made it possible to confirm the working hypothesis, according to which the contribution of PD of a non-affective circle (and, in particular, of an anxious and suspicious nature) to susceptibility to depression is not limited to the formation of vulnerability to certain pathogenic factors triggering an affective disorder (endogenous, psychogenic, somatogenic) or pathoplastic influences, as the concepts of the same name postulate (spectrum [48, 51, 135, 138, 171, 210], vulnerability [60, 63, 90, 104, 116, 166]). Being a heterogeneous affective RL anomaly, this warehouse includes (like affective RL), albeit in an unexpanded form, dimensions - harbingers of a future depression. Accordingly, with an anxious and suspicious character, there is a hidden / latent stigmatization, reflecting the affinity of this constitutional warehouse with the RL of the affective cluster [18] .

Being a heterogeneous affective RL anomaly, this warehouse includes (like affective RL), albeit in an unexpanded form, dimensions - harbingers of a future depression. Accordingly, with an anxious and suspicious character, there is a hidden / latent stigmatization, reflecting the affinity of this constitutional warehouse with the RL of the affective cluster [18] .

The stigmatization of the affective type appears most clearly in the analysis of the trajectory of psychasthenic pathocharacterological properties.

In this regard, it is necessary to emphasize such features of the dynamics of the discussed variant of RL as reactive lability, associated with the instability of the affective and vegetative background and, according to P.B. Gannushkin [10], one of the important components of vulnerability to depression. Already from childhood or adolescence, there is a tendency to develop blurred hypothymic episodes occurring at the subclinical level (subthreshold affective disorders H. Helmchen and M. Linden [103]). The latter are considered as "nuclear" manifestations of affective (cyclothymic) diathesis [47, 172]. At the same time, like “affective” PD, in which E. Kretschmer [138] singles out the hypothymic radical as a “characterological link between the hyperthymic and melancholic halves of the cycloid warehouse”, this affective deposit also appears in the considered variant. The latter in the structure of an anxious and suspicious character is manifested (albeit in the form of latent, optional features) by responsiveness to someone else's grief, the ability to take everything “close to heart”, and easily respond to sad events.

Helmchen and M. Linden [103]). The latter are considered as "nuclear" manifestations of affective (cyclothymic) diathesis [47, 172]. At the same time, like “affective” PD, in which E. Kretschmer [138] singles out the hypothymic radical as a “characterological link between the hyperthymic and melancholic halves of the cycloid warehouse”, this affective deposit also appears in the considered variant. The latter in the structure of an anxious and suspicious character is manifested (albeit in the form of latent, optional features) by responsiveness to someone else's grief, the ability to take everything “close to heart”, and easily respond to sad events.

This constitutional deposit is realized during periods of exacerbation of pathocharacterological symptom complexes, inseparable from the tendency of "anxious-suspicious" personalities to dramatize key experiences. In critical situations (examinations, preparation for the wedding, "work rush" at work) there is a sharpening of their inherent anxiety properties (self-doubt, tendency to doubt, timidity) [19] , reaching the level of clinically outlined anxiety symptom complexes - panic attacks and /or vital (generalized) anxiety that determines the picture of the reaction. Accordingly, the clinical space of affective disorders, the main manifestations of which are combined with the anxious component, is narrowing. Hypothymia loses its vitality and acts at the level of optional elements of the syndrome. However, in this "narrowed" space, even before the formation of a manifest depressive episode, a constitutional affective radical is realized. Manifestations of such hypothymia masked by anxious phenomena (somatic anxiety, psychovegetative, organoneurotic symptoms) [148] include signs-predictors (outpost-symptoms) of future melancholic depression [20] . Among them, the most informative are erased anhedonia (“insipid life with sadness” in the self-description of patients), anticipating the formation of melancholy, a pessimistic attitude with a decrease in self-esteem - a harbinger of ideas of insolvency, weight loss / insomnia - a “lightning bolt” of somatic depression syndrome.

Accordingly, the clinical space of affective disorders, the main manifestations of which are combined with the anxious component, is narrowing. Hypothymia loses its vitality and acts at the level of optional elements of the syndrome. However, in this "narrowed" space, even before the formation of a manifest depressive episode, a constitutional affective radical is realized. Manifestations of such hypothymia masked by anxious phenomena (somatic anxiety, psychovegetative, organoneurotic symptoms) [148] include signs-predictors (outpost-symptoms) of future melancholic depression [20] . Among them, the most informative are erased anhedonia (“insipid life with sadness” in the self-description of patients), anticipating the formation of melancholy, a pessimistic attitude with a decrease in self-esteem - a harbinger of ideas of insolvency, weight loss / insomnia - a “lightning bolt” of somatic depression syndrome.

Even more obvious is the affective stigmatization of the anxious and suspicious warehouse in the formation of disorders of the hyperthymic circle. Hyperthymia in these observations takes on more distinct clinical forms and develops (compared to hypothymia) according to other clinical mechanisms. If the manifestation and reverse development of depressive disorders are closely related to exacerbation and the subsequent dynamics of anxiety-phobic symptom complexes, which are pushed to the level of facultative symptom complexes, then the manifestations of hyperthymia, previously latent, during periods of compensation inherent in the anxious-suspectoral nature of pathocharacterological manifestations, are accentuated to the level of obligate personality dimensions. The latter are correlated with the characteristics of “balanced” [184], “passive” [173] hyperthymics, which are characterized by a “flat line” of increased affect [85]. Being energetic, productive enough, patients do not commit reckless acts. Their restless activity (in a self-description - the ability to "turn like a top") is predictable and is realized within a narrow circle of official duties and everyday concerns.

Hyperthymia in these observations takes on more distinct clinical forms and develops (compared to hypothymia) according to other clinical mechanisms. If the manifestation and reverse development of depressive disorders are closely related to exacerbation and the subsequent dynamics of anxiety-phobic symptom complexes, which are pushed to the level of facultative symptom complexes, then the manifestations of hyperthymia, previously latent, during periods of compensation inherent in the anxious-suspectoral nature of pathocharacterological manifestations, are accentuated to the level of obligate personality dimensions. The latter are correlated with the characteristics of “balanced” [184], “passive” [173] hyperthymics, which are characterized by a “flat line” of increased affect [85]. Being energetic, productive enough, patients do not commit reckless acts. Their restless activity (in a self-description - the ability to "turn like a top") is predictable and is realized within a narrow circle of official duties and everyday concerns. Accordingly, we are talking about erased, masked hypomanias [65], in some cases situationally provoked (happy romance, childbirth, promotion).

Accordingly, we are talking about erased, masked hypomanias [65], in some cases situationally provoked (happy romance, childbirth, promotion).

As shown by our own clinical observations [38], the compensation of anxious and suspicious PD is accompanied by a transposition (re-accentuation) of pathocharacterological properties - psychasthenic features, although they persist, but constitutional characteristics related to the RL spectrum of the affective (hyperthymic) circle come to the fore. During this period, patients act in a different "hypostasis" - the opposite of hypothymia - as active, cheerful people who love pleasure, who do not shy away from parties, feasts, and cheerful companies.

Thus, an anxious and suspicious character, in the structure of which affective stigmatization was revealed, can be combined with affective PD on the basis of a single complex of abnormal personality traits that determines the predisposition to the manifestation of melancholic depression and be considered as a factor of comorbidity with affective spectrum disorders.