Adhd thought patterns

3 Defining Features of ADHD: Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria, Hyperfocus

The DSM-V – the bible of psychiatric diagnosis – lists 18 diagnostic criteria for ADHD. Clinicians use these to identify symptoms, insurance companies use it to determine coverage, and researchers use it to determine areas of worthwhile study.

The problem: These criteria only describe how ADHD affects children ages 6-12. The signs of ADHD in teens, adults, and the elderly, on the other hand, are not as well known. This has led to misdiagnosis, misunderstanding, and failed treatment for these groups.

Most people, clinicians included, have only a vague understanding of what ADHD means. They assume it equates to hyperactivity and poor focus, mostly in children. They are wrong.

When we step back and ask, “What does everyone with ADHD have in common, that people without ADHD don’t experience?” a different set of symptoms take shape.

From this perspective, three defining features of ADHD emerge that explain every aspect of the condition:

1. An interest-based nervous system

2. Emotional hyperarousal

3. Rejection sensitivity

[Self-Test: Could You Have Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria?]

1. Interest-Based ADHD Nervous System

What is an interest-based nervous system?

Despite its name, ADHD doesn’t actually cause a deficit of attention. It actually causes inconsistent attention that is only activated under certain circumstances.

People with ADHD often say they “get in the zone” or “hit a groove.” These are all ways of describing a state of hyperfocus – intense concentration on a particular task, during which the individual feels she can accomplish anything. In fact, she may become so intently focused that the adult with ADD may lose all sense of how much time has passed.

This state is not activated by a teacher’s assignment, or a boss’s request. It is only created by a momentary sense of interest, competition, novelty, or urgency created by a do-or-die deadline.

The ADHD nervous system is interest-based, rather than importance- or priority-based.

[Free Download: 3 Defining Features of ADHD That Everyone Overlooks]

How do I recognize an interest-based ADHD nervous system?

Clinicians often ask, “Can you pay attention?” And the answer is typically, “Sometimes.”

This is the wrong question. Parents, loved ones, and teachers answering it often express frustration because they have seen you hone in on something you enjoy – like video games – for hours, so your inability to conjure that same focus for other tasks and projects is interpreted as defiance or selfishness.

Instead, practitioners should ask, “Have you ever been able to get engaged and stay engaged?” Then, “Once you’re engaged, have you ever found something you couldn’t do?”

Anyone with ADHD will answer along these lines: “I have always been able to do anything I wanted so long as I could get engaged through interest, challenge, novelty, urgency, or passion.”

“I have never been able to make use of the three things that organize and motivate everyone else: importance, rewards, and consequences. ”

”

What can I do to manage an interest-based nervous system?

An effective ADHD management plan needs two parts:

- medication to level the neurological playing field

- a new set of rules that teach you how to get engaged on demand

Stimulant medications are very good at keeping the ADHD brain from getting distracted once they are engaged, but they do not help you get engaged in the first place.

Most systems for planning and organization are built for neurotypical brains that use importance and time to spark motivation. Instead, you must create your own “owner’s manual” for sparking interest by focusing on how and when you do well, and creating those circumstances at the outset.

This work is highly personal, and will change over time. It can involve strategies like “body-doubling,” or asking another person to sit with you while you do work. Or “injecting interest” by transforming an otherwise boring task through imagination. For example, an anatomy student who is bored with studying can imagine she is learning the anatomy to save her idol’s life.

2. ADHD Emotional Hyperarousal

What is emotional hyperarousal?

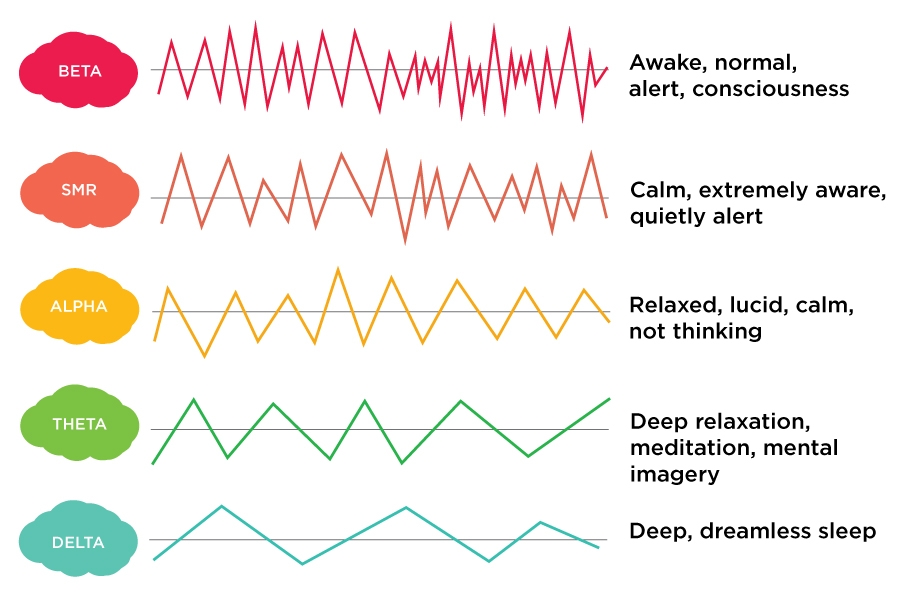

Most people expect ADHD to create visible hyperactivity. This only occurs in 25% of children and 5% of adults. The rest experience an internal feeling of hyperarousal. When I ask people with ADHD to elaborate on it, they say:

- “I’m always tense. I can never relax.”

- “I can’t just sit there and watch a TV program with the rest of the family.”

- “I can’t turn my brain and body off to go to sleep at night.”

People with ADHD have passionate thoughts and emotions that are more intense than those of the average person. Their highs are higher and their lows are lower. This means you may experience both happiness and criticism more powerfully than your peers and loved ones do.

Children with ADHD know they are “different,” which is rarely experienced as a good thing. They may develop low self-esteem because they realize they fail to get engaged and finish what they start, and because children make no distinction between what you do and who you are. Shame can become a dominant emotion into adulthood as harsh internal dialogues, or criticism from others, becomes ingrained.

Shame can become a dominant emotion into adulthood as harsh internal dialogues, or criticism from others, becomes ingrained.

How do I recognize emotional hyperarousal?

Clinicians are trained to recognize mood disorders, not the increased intensity of moods that comes with ADHD. Many people with ADHD are first misdiagnosed with a mood disorder. On average, an adult will see 2.3 clinicians and go through 6.6 antidepressant trials before being diagnosed with attention deficit disorder.

Mood disorders are characterized by moods that have taken on a life of their own, separate from the events of the person’s life, and often last for more than two weeks. Moods created by ADHD are almost always triggered by events and perceptions, and resolve very quickly. They are normal moods in every way except for their intensity.

Clinicians should ask, “When you are upset, do you often ‘get over it’ quickly?” “Do you feel like you can’t rid your brain of a certain thought or idea when you want to?”

What can I do to manage emotional hyperarousal?

To counteract feelings of shame and low self-esteem, people with ADHD need support from other individuals who believe they are a good or worthwhile person. This can be a parent, older sibling, teacher, coach, or even a kind neighbor. Anyone, as long as they think you are good, likeable, and capable – especially when things go wrong. This “cheerleader” must be sincere because people with ADHD are great lie detectors.

This can be a parent, older sibling, teacher, coach, or even a kind neighbor. Anyone, as long as they think you are good, likeable, and capable – especially when things go wrong. This “cheerleader” must be sincere because people with ADHD are great lie detectors.

A cheerleader’s main message is, “I know you, you’re a good person. If anybody could have overcome these problems by hard work and just sheer ability, it would have been you. So what that tells me is that there’s something we don’t see that’s getting in your way and I want you to know I will be there with you all the way until we figure out what it is and we master that problem.”

The true key to fighting low self-esteem and shame is helping a person with ADHD figure out how to succeed with their unique nervous system. Then, the person with ADHD is not left alone with feelings of shame or blamed for falling short.

3. Rejection Sensitivity

What is rejection sensitivity?

Rejection sensitive dysphoria (RSD) is an intense vulnerability to the perception – not necessarily the reality – of being rejected, teased, or criticized by important people in your life. RSD causes extreme emotional pain that may also be triggered by a sense of failure, or falling short – failing to meet either your own high standards or others’ expectations.

RSD causes extreme emotional pain that may also be triggered by a sense of failure, or falling short – failing to meet either your own high standards or others’ expectations.

It is a primitive reaction that people with ADHD often struggle to describe. They say, “I can’t find the words to tell you what it feels like, but I can hardly stand it.” Often, people experience RSD as physical pain, like they’ve been stabbed or struck right in the center of their chest.

Often, this intense emotional reaction is hidden from other people. People experiencing it don’t want to talk about it because of the shame they feel over their lack of control, or because they don’t want people to know about this intense vulnerability.

How do I recognize rejection sensitivity?

The question that can help identify RSD is, “For your entire life, have you always been much more sensitive than other people you know to rejection, teasing, criticism, or your own perception that you have failed?”

When a person internalizes the emotional response of RSD, it can look like sudden development of a mood disorder. He or she may be saddled with a reputation as a “head case” who needs to be “talked off the ledge.” When the emotional response of RSD is externalized, it can look like a flash of rage. Half of people who are mandated by courts to receive anger-management training had previously unrecognized ADHD.

He or she may be saddled with a reputation as a “head case” who needs to be “talked off the ledge.” When the emotional response of RSD is externalized, it can look like a flash of rage. Half of people who are mandated by courts to receive anger-management training had previously unrecognized ADHD.

Some people avoid rejection by becoming people pleasers. Others just opt out altogether, and choose not to try because making any effort is so anxiety-provoking.

What can I do to manage rejection sensitivity?

98-99% of adolescents and adults with ADHD acknowledge experiencing RSD. For 30%, RSD is the most impairing aspect of their ADHD, in part because it does not respond to therapy.

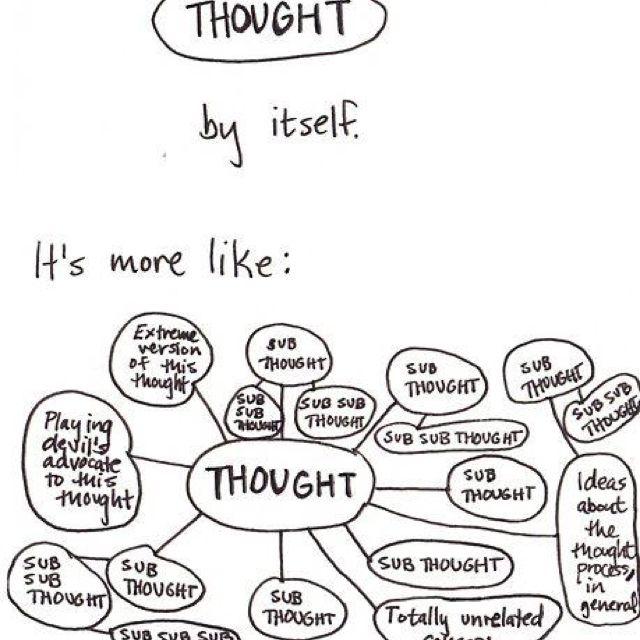

Alpha-agonist medications, like guanfacine and clonidine, can help treat it. Only about one in three people experience relief from either medication, but 60% experience robust benefits when both are tried. When successfully treated, people with RSD report feeling “at peace,” or like they have “emotional armor. ” They still see the same things happening that would have previously wounded them, but now it bounces off without injury. They also report that, rather than three or four simultaneous thoughts, they now have just one thought at a time.

” They still see the same things happening that would have previously wounded them, but now it bounces off without injury. They also report that, rather than three or four simultaneous thoughts, they now have just one thought at a time.

More Recommended Reading

- Self-Test: Could You Have Adult ADHD / ADD?

- Exaggerated Emotions: How and Why ADHD Triggers Intense Feelings

- Free Download: Inattentive ADHD — Explained

William Dodson, M.D., is a member of ADDitude’s ADHD Medical Review Panel.

Previous Article Next Article

Understanding the Neurology of ADD

Here is a truth that people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD or ADD) know from an early age: If you have an ADHD nervous system, you might as well have been born on a different planet.

Most adults with ADHD have always known that they think differently. They were told by parents, teachers, employers, spouses, and friends that they did not fit the common mold and that they had better shape up in a hurry if they wanted to make something of themselves.

They were told by parents, teachers, employers, spouses, and friends that they did not fit the common mold and that they had better shape up in a hurry if they wanted to make something of themselves.

As if they were immigrants, they were told to assimilate into the dominant culture and become like everyone else. Unfortunately, no one told them how to do this. No one revealed the bigger secret: It couldn’t be done, no matter how hard they tried. The only outcome would be failure, made worse by the accusation that they will never succeed because ADHD in adulthood means they didn’t try hard enough or long enough.

It seems odd to call a condition a disorder when the condition comes with so many positive features. People with an ADHD-style nervous system tend to be great problem-solvers. They wade into problems that have stumped everyone else and jump to the answer. They are affable, likable people with a sense of humor. They have what Paul Wender called “relentless determination. ” When they get hooked on a challenge, they tackle it with one approach after another until they master the problem — and they may lose interest entirely when it is no longer a challenge.

” When they get hooked on a challenge, they tackle it with one approach after another until they master the problem — and they may lose interest entirely when it is no longer a challenge.

If I could name the qualities that would assure a person’s success in life, I would say being bright, being creative with that intelligence, and being well-liked. I would also choose hardworking and diligent. I would want many of the traits that people with ADHD possess.

[Take This Test: Could You Have ADHD?]

The main obstacle to understanding and managing ADHD has been the unstated and incorrect assumption that individuals with ADHD could and should be like the rest of us. For neurotypicals and adults with ADHD alike, here is a detailed portrait of why people with ADHD do what they do.

Why People with ADHD Don’t Function Well in a Linear World

The ADHD world is curvilinear. Past, present, and future are never separate and distinct. Everything is now. People with ADHD live in a permanent present and have a hard time learning from the past or looking into the future to see the inescapable consequences of their actions. “Acting without thinking” is the definition of impulsivity, and one of the reasons that individuals with ADHD have trouble learning from experience.

“Acting without thinking” is the definition of impulsivity, and one of the reasons that individuals with ADHD have trouble learning from experience.

It also means that people with ADHD aren’t good at ordination — planning and doing parts of a task in order. Tasks in the neurotypical world have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Individuals with ADHD don’t know where and how to start, since they can’t find the beginning. They jump into the middle of a task and work in all directions at once. Organization becomes an unsustainable task because organizational systems work on linearity, importance, and time.

Why People with ADHD Are Overwhelmed

People in the ADHD world experience life more intensely, more passionately than neurotypicals. They have a low threshold for outside sensory experience because the day-to-day experience of their five senses and their thoughts is always on high volume. The ADHD nervous system is overwhelmed by life experiences because its intensity is so high.

[Get This Free Download: Secrets of the ADHD Brain]

The ADHD nervous system is rarely at rest. It wants to be engaged in something interesting and challenging. Attention is never “deficit.” It is always excessive, constantly occupied with internal reveries and engagements. When people with ADHD are not in The Zone, in hyperfocus, they have four or five things rattling around in their minds, all at once and for no obvious reason, like five people talking to you simultaneously. Nothing gets sustained, undivided attention. Nothing gets done well.

Many people with ADHD can’t screen out sensory input. Sometimes this is related to only one sensory realm, such as hearing. In fact, the phenomenon is called hyperacusis (amplified hearing), even when the disruption comes from another of the five senses. Here are some examples:

- The slightest sound in the house prevents falling asleep and overwhelms the ability to disregard it.

- Any movement, no matter how small, is distracting.

- Certain smells, which others barely notice, cause people with ADHD to leave the room.

Individuals with ADHD have their worlds constantly disrupted by experiences of which the neurotypical is unaware. This disruption enforces the perception of the ADHD person as being odd, prickly, demanding, and high-maintenance. But this is all that people with ADHD have ever known. It is their normal. The notion of being different, and that difference being perceived as unacceptable by others, is made a part of how they are regarded. It is a part of their identity.

Sometimes, a person with ADHD can hit the do-or-die deadline and produce lots of high-quality work in a short time. A whole semester of study is crammed into a single night of hyperfocused perfection. Some people with ADHD create crises to generate the adrenaline to get them engaged and functional. The “masters of disasters” handle high-intensity crises with ease, only to fall apart when things become routine again.

Lurching from crisis to crisis, however, is a tough way to live life. Occasionally, I run across people who use anger to get the adrenaline rush they need to get engaged and be productive. They resurrect resentments or slights, from years before, to motivate themselves. The price they pay for their productivity is so high that they may be seen as having personality disorders.

Why People with ADHD Don’t Always Get Things Done

People with ADHD are both mystified and frustrated by secrets of the ADHD brain, namely the intermittent ability to be super-focused when interested, and challenged and unable to start and sustain projects that are personally boring. It is not that they don’t want to accomplish things or are unable to do the task. They know they are bright and capable because they’ve proved it many times. The lifelong frustration is never to be certain that they will be able to engage when needed, when they are expected to, when others depend on them to. When people with ADHD see themselves as undependable, they begin to doubt their talents and feel the shame of being unreliable.

Mood and energy level also swing with variations of interest and challenge. When bored, unengaged, or trapped by a task, the person with ADHD is lethargic, quarrelsome, and filled with dissatisfaction.

Why Our ADHD Motors Always Run

By the time most people with ADHD are adolescents, their physical hyperactivity has been pushed inward and hidden. But it is there and it still impairs the ability to engage in the moment, listen to other people, to relax enough to fall asleep at night, and to have periods of peace.

So when the distractibility and impulsivity are brought back to normal levels by stimulant medication, a person with ADHD may not be able to make use of his becalmed state. He is still driven forward as if by a motor on the inside, hidden from the rest of the world. By adolescence, most people with ADHD-style nervous systems have acquired the social skills necessary to cover up that they are not present.

But they rarely get away with it entirely. When they tune back into what has gone on while they were lost in their thoughts, the world has moved on without them. Uh-oh. They are lost and do not know what is going on, what they missed, and what is now expected of them. Their reentry into the neurotypical world is unpleasant and disorienting. To individuals with ADHD, the external world is not as bright as the fantastic ideas they had while lost in their own thoughts.

Uh-oh. They are lost and do not know what is going on, what they missed, and what is now expected of them. Their reentry into the neurotypical world is unpleasant and disorienting. To individuals with ADHD, the external world is not as bright as the fantastic ideas they had while lost in their own thoughts.

Why Organization Eludes People with ADHD

The ADHD mind is a vast and unorganized library. It contains masses of information in snippets, but not whole books. The information exists in many forms — as articles, videos, audio clips, Internet pages — and also in forms and thoughts that no one has ever had before. But there is no card catalog, and the “books” are not organized by subject or even alphabetized.

Each person with ADHD has his or her own brain library and own way of storing that huge amount of material. No wonder the average person with ADHD cannot access the right piece of information at the moment it is needed — there is no reliable mechanism for locating it. Important items (God help us, important to someone else) have no fixed place, and might as well be invisible or missing entirely. For example:

Important items (God help us, important to someone else) have no fixed place, and might as well be invisible or missing entirely. For example:

The child with ADHD comes home and tells Mom that he has no homework to do. He watches TV or plays video games until his bedtime. Then he recalls that he has a major report due in the morning. Was the child consciously lying to the parent, or was he truly unaware of the important task?

For a person with ADHD, information and memories that are out of sight are out of mind. Her mind is a computer in RAM, with no reliable access to information on the hard drive.

Working memory is the ability to have data available in one’s mind, and to be able to manipulate that data to come up with an answer or a plan of action. The mind of a person with ADHD is full of the minutiae of life (“Where are my keys?” “Where did I park the car?”), so there is little room left for new thoughts and memories. Something has to be discarded or forgotten to make room for new information. Often the information individuals with ADHD need is in their memory…somewhere. It is just not available on demand.

Often the information individuals with ADHD need is in their memory…somewhere. It is just not available on demand.

Why We Don’t See Ourselves Clearly

People from the ADHD world have little self-awareness. While they can often read other people well, it is hard for the average person with ADHD to know, from moment to moment, how they themselves are doing, the effect they are having on others, and how they feel about it all. Neurotypicals misinterpret this as being callous, narcissistic, uncaring, or socially inept. Taken together, the vulnerability of a person with ADHD to the negative feedback of others, and the lack of ability to observe oneself in the moment, make a witch’s brew.

If a person cannot see what is going on in the moment, the feedback loop by which he learns is broken. If a person does not know what is wrong or in what particular way it is wrong, she doesn’t know how to fix it. If people with ADHD don’t know what they’re doing right, they don’t do more of it. They don’t learn from experience.

They don’t learn from experience.

The inability of the ADHD mind to discern how things are going has many implications:

- Many people with ADHD find that the feedback they get from other people is different from what they perceive. They find out, many times (and often too late), that the other people were right all along. It isn’t until something goes wrong that they are able to see and understand what was obvious to everybody else. Then, they come to believe that they can’t trust their own perceptions of what is going on. They lose self-confidence. Even if they argue it, many people with ADHD are never sure that they are right about anything.

- People with ADHD may not be able to recognize the benefits of medication, even when those benefits are obvious. If a patient sees neither the problems of ADHD nor the benefits of treatment, he finds no reason to continue treatment.

- Individuals with ADHD often see themselves as misunderstood, unappreciated, and attacked for no reason.

Alienation is a common theme. Many think that only another person with ADHD could possibly “get” them.

Alienation is a common theme. Many think that only another person with ADHD could possibly “get” them.

Why People with ADHD are Time Challenged

Because people with ADHD don’t have a reliable sense of time, everything happens right now or not at all. Along with the concept of ordination (what must be done first; what must come second) there must also be the concept of time. The thing at the top of the list must be done first, and there must be time left to do the entire task.

I made the observation that 85 percent of my ADHD patients do not wear or own a watch. More than half of those who wore a watch did not use it, but wore it as jewelry or to not hurt the feelings of the person who gave it to them. For individuals with ADHD, time is a meaningless abstraction. It seems important to other people, but people with ADHD have never gotten the hang of it.

[Read This Next: Why You Do What You Do and Feel How You Feel]

William Dodson, M.D., is a member of ADDitude’s ADHD Medical Review Panel.

Previous Article Next Article

Cognitive behavioral therapy for ADHD: how does it work?

This article is a translation of material from the group of authors CARL SHERMAN, PH.D., J. RUSSELL RAMSAY, PH.D., KAREN BARROW. Original here

ADHD, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is a chronic, persistent delay in self-regulation skills. It includes procrastination, disorganization, poor time management, emotional dysregulation, impulsivity. Although these problems are not included in the official diagnostic criteria for ADHD, they are common in adults with the condition, making it difficult for them to regulate their emotions and behaviors.

People who grow up with ADHD (especially if it has not been diagnosed) face more frequent and frustrating setbacks in life situations - at work, in social interactions and daily organization./s3/static.nrc.nl/bvhw/files/2016/12/data7688230.jpg) Because of these many failures, adults with ADHD become self-critical and pessimistic.

Because of these many failures, adults with ADHD become self-critical and pessimistic.

This, in turn, sometimes causes them to experience negative emotions, cognitive distortions and unhealthy self-beliefs. People living with ADHD often think they are to blame when things don't go well, although in many cases this is not the case. They can bring the same pessimism into the future, imagining that tomorrow will be just as bad as today.

Cognitive distortions

Demoralizing thoughts and beliefs that prevent people from doing what they want are actually not always logical and can be challenged. As CBT shows, these thought processes are distorted in certain characteristic ways:

All or nothing thinking. You see everything as completely good or completely bad: if you don't do something perfectly, you have failed.

Excessive generalization. You see one negative event as part of a pattern: for example, you always forget to pay your bills.

Mind reading. You think you know what people think about you or what you've done, and that's bad.

Divination. You predict that everything will turn out badly.

Exaggeration and minimization. You exaggerate the importance of minor problems, belittling your achievements.

Must statements. You focus on how things should be, leading to severe self-criticism as well as resentment towards others.

Personalization. You blame yourself for negative events and minimize the responsibility of others.

Negative orientation, negative filter . You only see the negative aspects of any experience.

Emotional reasoning. You assume that your negative feelings reflect reality: having a bad attitude towards your job means "I'm not doing well and will probably get fired."

Comparative thinking. You compare yourself to others and feel inferior, even though the comparison may not be realistic.

Learning to recognize these distorted thoughts will help you replace them with realistic thinking.

“Understanding how you think is an effective starting point for making changes in your life,” says J. Russell Ramsay, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. “Changing thoughts and changing behavior go hand in hand. Expanding your perspective on a situation allows you to expand the ways in which you can deal with it.”

Adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) suffer from dangerously low self-esteem and persistent negative thoughts.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a short-term, targeted form of psychotherapy that aims to change these negative thought patterns and change how the patient feels about themselves, their abilities, and their future. Think of it as brain training for ADHD.

Originally aimed at treating mood disorders, CBT is based on the recognition that cognitive abilities, or automatic thoughts lead to emotional difficulties. Automatic thoughts are spontaneous interpretations of events. These impressions are subject to distortions, such as unwarranted assumptions about the self (or others), the situation, or the future. Such unhealthy internal dialogues prevent a person from working towards an intended goal, developing new productive habits, or even taking calculated risks.

Automatic thoughts are spontaneous interpretations of events. These impressions are subject to distortions, such as unwarranted assumptions about the self (or others), the situation, or the future. Such unhealthy internal dialogues prevent a person from working towards an intended goal, developing new productive habits, or even taking calculated risks.

CBT seeks to change the irrational thought patterns that prevent people from staying on task. For the person with ADHD who thinks: " It has to be perfect, otherwise it's no good " or " I never do anything right ", CBT challenges the truth of these cognitive beliefs.

Changing distorted thoughts and, as a result, changing behavior patterns is effective in treating anxiety and other emotional problems.

How exactly does CBT improve ADHD in adults?

CBT helps patients cope with everyday problems.

CBT intervenes to help manage procrastination, time management, and other common difficulties—not to treat the underlying symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.

CBT sessions focus on identifying situations in which poor planning, disorganization, and poor time and task management create problems in the patient's daily life.

Sessions can help a person cope with responsibilities such as paying bills on time or completing work, and encourage efforts for personal fulfillment and well-being, such as sleep, exercise, or hobbies.

The study of ADHD is always a good starting point, as it reinforces the notion that ADHD is not a character flaw and shows the neurological basis of daily problems.

Most adults with ADHD say, " I know what I need to do, but I don't." Although they have plans for what they want or need to do, they do not carry them out. CBT focuses on adopting coping strategies, managing negative expectations and emotions, and creating behavioral patterns that interfere with strategies.

The goals and agenda for CBT sessions are created based on the scenarios and challenges the patient has encountered.

What does a typical CBT session look like?

CBT is administered in a variety of formats, and each therapist will tailor sessions to suit the individual needs of the patient. The agenda of each session serves as a guideline for determining when the discussion deviates from the intended course.

The first sessions usually include an introduction to CBT, the structure of the sessions, setting and clarifying goals for therapy (making them specific, realistic, and actionable), and developing action plans for what the patient will do outside of the office.

Subsequent sessions focus on identifying the most important life situations affecting the patient and developing skills to cope with these situations.

One of the myths about CBT is that it ignores childhood and the past. These early life experiences are the raw material from which people develop deep-seated, unconscious beliefs and rules about "how the world works" and what our role is in it.

The patient's understanding of his "rules of conduct in the world" is the most important goal of CBT . Understanding them helps adults with ADHD understand their patterns of self-criticism (or criticism of others), avoidance, and self-destructive behavior.

Ultimately, the main goals of CBT are to overcome violations and implement their coping strategies . CBT helps in processing new experiences and finding new ways to deal with setbacks. She adapts the old rules to modern life. And teaches a person to change life in accordance with their capabilities and desires.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Cognition

Nanda Rommels, PhD

Radboud University Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, The Netherlands

(English). Translation: November 2015

Translation: November 2015

Introduction

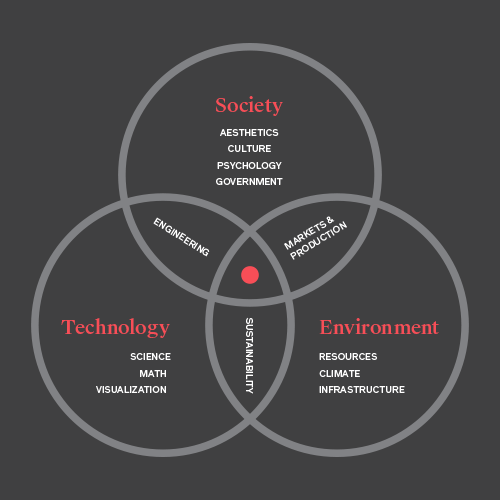

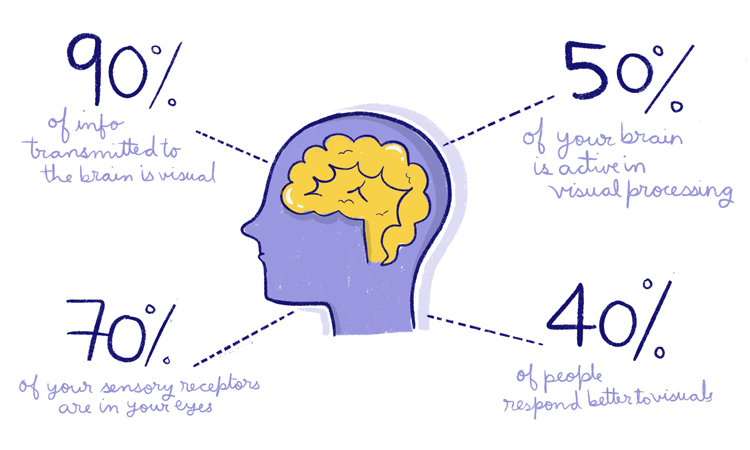

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is characterized by a triad of symptoms: inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. 1 This disorder is highly heritable and affects about 3-5% of school-age children. 2.3 In recent decades, the cognitive problems of ADHD have been widely studied. Cognition can be defined as the acquisition of knowledge and its comprehension, including thinking, knowing, remembering, judging, and problem solving.

Subject

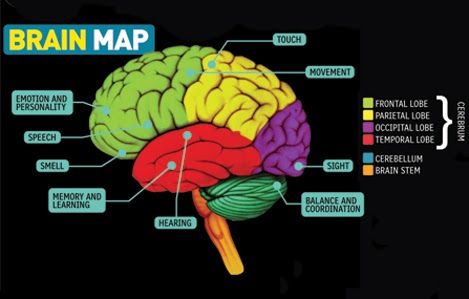

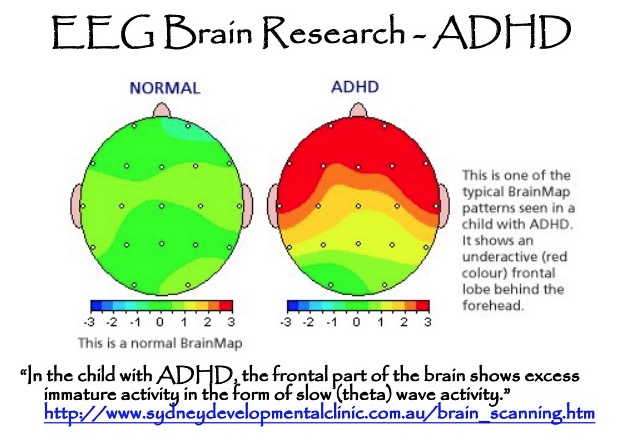

Several causal models have been proposed in an attempt to combine research findings on the biological and cognitive impairments common in ADHD. All proposed cognitive models agree that executive functioning (EF) impairments are one of the most significant characteristics of ADHD. EFs were defined as "those abilities that allow a person to successfully carry out independent and purposeful behavior, to act in their own interests. " 4 Many studies of ADHD patients have documented UF impairments, with inhibition and working memory problems being the most common. 5 EF abnormalities are closely associated with abnormalities in the prefrontal lobe and fronto-subcortical connections, which are often found in patients with ADHD. 6.7

" 4 Many studies of ADHD patients have documented UF impairments, with inhibition and working memory problems being the most common. 5 EF abnormalities are closely associated with abnormalities in the prefrontal lobe and fronto-subcortical connections, which are often found in patients with ADHD. 6.7

Problematic

Although most ADHD causal models include UV deficiency as an important factor, it is not really known whether ADHD is caused by UV deficiency, and to what extent. In other words, given that ADHD is a highly inherited disorder, is EF an inherited trait that increases the risk of developing ADHD, and for what percentage of patients would EF be a causative factor?

Key questions

Two questions are central to establishing a causal relationship between UV deficiency and ADHD:

- the same genes as ADHD?

- What percentage of children with ADHD actually suffer from UV problems?

Latest research results

Are UV problems hereditary, and are they related to the same genes as ADHD?

Twin studies are the first necessary step to determine if UV deficiency is hereditary. This approach makes it possible to distinguish between the influence of hereditary and environmental factors on UV. Problem solving on UV has been studied in several twin studies. 12-16 At ages 5 and 12, approximately 50% of success on multiple EF tasks was found to be related to genetic factors. 16 Other studies have found similar rates of 40 to 50%, 12,13,15 suggesting that success on EF tasks is moderately heritable. Moreover, genetic factors are an important mediator of UV resistance in childhood. 14

This approach makes it possible to distinguish between the influence of hereditary and environmental factors on UV. Problem solving on UV has been studied in several twin studies. 12-16 At ages 5 and 12, approximately 50% of success on multiple EF tasks was found to be related to genetic factors. 16 Other studies have found similar rates of 40 to 50%, 12,13,15 suggesting that success on EF tasks is moderately heritable. Moreover, genetic factors are an important mediator of UV resistance in childhood. 14

The second step to determine whether UV deficiency is inherited and related to the same genes as ADHD is to study the success of UV tasks in relatives of patients with ADHD. This sheds light on the familial nature of UV deficiency in ADHD. Siblings, for example, share up to 50% of the same genes on average. It is therefore possible that non-affected siblings of a child with ADHD carry risk genes without having the phenotypic manifestation of ADHD. If EF deficiency is indeed familial with ADHD, non-affected siblings will show the same EF deficiency, perhaps to a lesser extent than their ADHD siblings.

If EF deficiency is indeed familial with ADHD, non-affected siblings will show the same EF deficiency, perhaps to a lesser extent than their ADHD siblings.

Several studies have specifically examined UV in families with ADHD, and the results support the hypothesis that UV deficiency is familial and is also present (to a lesser extent) in non-affected relatives of ADHD patients. 5.17-21 Studies specifically targeting inhibition control or intervention as an executive function have also produced encouraging results, with relatives finding similar results in performance and non-affected relatives showing minor weaknesses in this area. 22-26 These results suggest that UV deficiency is familial. Although these data are insufficient to suggest that UV problems are hereditary; but at least they are consistent with this hypothesis.

The final step in investigating whether UV deficiency is associated with the same genes as ADHD is to investigate the performance of UV against ADHD candidate genes and/or use UV performance for linkage analysis in pedigrees with a history of ADHD. Both of these strategies are rarely implemented due to the large sample size required for the statistical power they require. Preliminary results indicate that polymorphisms in a gene (the dopamine D4 receptor gene) that has been most reliably replicated for ADHD are in fact also related to UV. 15.27-30 One linkage study identified a genome-wide linkage trait on chromosome 13q12. 11 using the Verbal Working Memory score in ADHD pedigrees, suggesting that the genes at this location may influence both ADHD and the level of EF task performance. 31 In addition, another linkage study found that a region on chromosome 3q13 was associated with both composite UF and ADHD inattention symptoms, indicating that this lack of UF may be associated with the same genes which is ADHD. 32

Both of these strategies are rarely implemented due to the large sample size required for the statistical power they require. Preliminary results indicate that polymorphisms in a gene (the dopamine D4 receptor gene) that has been most reliably replicated for ADHD are in fact also related to UV. 15.27-30 One linkage study identified a genome-wide linkage trait on chromosome 13q12. 11 using the Verbal Working Memory score in ADHD pedigrees, suggesting that the genes at this location may influence both ADHD and the level of EF task performance. 31 In addition, another linkage study found that a region on chromosome 3q13 was associated with both composite UF and ADHD inattention symptoms, indicating that this lack of UF may be associated with the same genes which is ADHD. 32

What percentage of children with ADHD have UV problems?

The percentage of children with ADHD who suffer from EF problems is highly dependent on the definition that there is an executive function deficit (DEF). 8 There is no agreement on what the DUV actually is, but most definitions imply performance below the 10th percentile level compared to a demographically matched control group on at least one, two, or three tasks per day. UV. At the group level, children with ADHD almost always perform worse on EF tasks than children in the control group. However, at the individual level, a certain proportion of children with ADHD outperform the corresponding proportion of children in the control group. 9 In other words, not every child with ADHD has DUV. Weaknesses in EF are not necessary or sufficient causes for all cases of ADHD. 9 Rather, other cognitive functions, motivational problems, or, in some cases, reactions to family distress or peer problems may lead to ADHD. 10.11 About one-third of children have moderately severe DUV, diagnosed when three or more UV measures are poor. 11

8 There is no agreement on what the DUV actually is, but most definitions imply performance below the 10th percentile level compared to a demographically matched control group on at least one, two, or three tasks per day. UV. At the group level, children with ADHD almost always perform worse on EF tasks than children in the control group. However, at the individual level, a certain proportion of children with ADHD outperform the corresponding proportion of children in the control group. 9 In other words, not every child with ADHD has DUV. Weaknesses in EF are not necessary or sufficient causes for all cases of ADHD. 9 Rather, other cognitive functions, motivational problems, or, in some cases, reactions to family distress or peer problems may lead to ADHD. 10.11 About one-third of children have moderately severe DUV, diagnosed when three or more UV measures are poor. 11

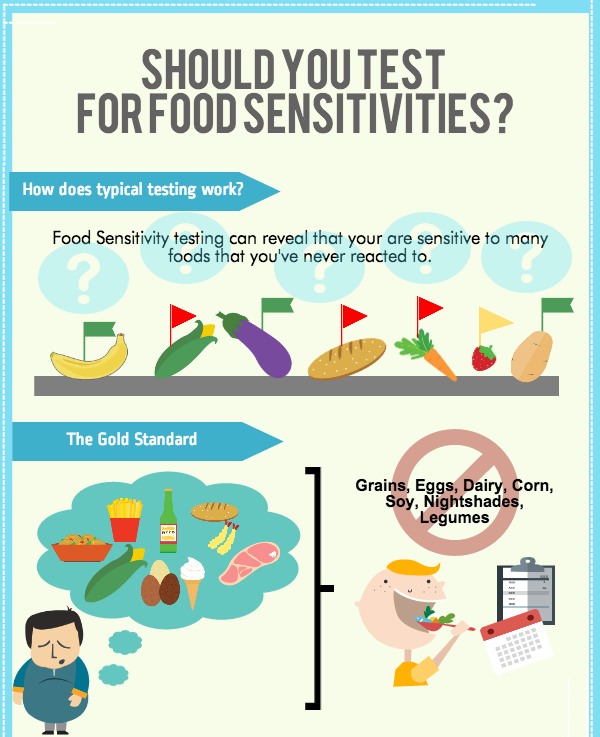

Unexplored areas

Determining whether the UV deficiency diagnosed in a proportion of ADHD patients is the real cause of ADHD in this group requires a more comprehensive approach than has been used to date. This means that only a few studies have examined EF in a familial context, and most of them lacked the statistical power for genetic analysis. An even more serious problem is that their results are difficult to compare with each other due to the use of different tasks and methods to measure the same control function. This becomes a particularly acute problem when attempting to combine corpora of cognitive data obtained from different institutions in order to increase the statistical power of genetic analysis. Thus, in order to determine whether the EF deficiency diagnosed in a proportion of patients with ADHD is the real cause of ADHD, it is necessary to offer EF tasks that have good norms and data on validity, reliability, and heritability. The use of the same tasks in the spirit of the "gold standard" would allow the combination of samples from different research sites. This would greatly increase the comparability of data and increase the power of genetic analysis, leading to more reliable results that can hopefully be applied in clinical practice.

This means that only a few studies have examined EF in a familial context, and most of them lacked the statistical power for genetic analysis. An even more serious problem is that their results are difficult to compare with each other due to the use of different tasks and methods to measure the same control function. This becomes a particularly acute problem when attempting to combine corpora of cognitive data obtained from different institutions in order to increase the statistical power of genetic analysis. Thus, in order to determine whether the EF deficiency diagnosed in a proportion of patients with ADHD is the real cause of ADHD, it is necessary to offer EF tasks that have good norms and data on validity, reliability, and heritability. The use of the same tasks in the spirit of the "gold standard" would allow the combination of samples from different research sites. This would greatly increase the comparability of data and increase the power of genetic analysis, leading to more reliable results that can hopefully be applied in clinical practice.

Conclusions

Success on EF tasks is moderately heritable, and genetic factors are an important mediator of EF resistance in childhood. UV deficiency is associated with ADHD within the family and may be related, among other things, to the dopamine D4 receptor gene, which is also related to ADHD. In other words, a (partly) genetic UV deficiency can cause ADHD. However, only a certain subset of patients with ADHD (about 30%) suffer from moderately severe EF problems, indicating that EF weaknesses are not necessary or sufficient causes responsible for all cases of ADHD.

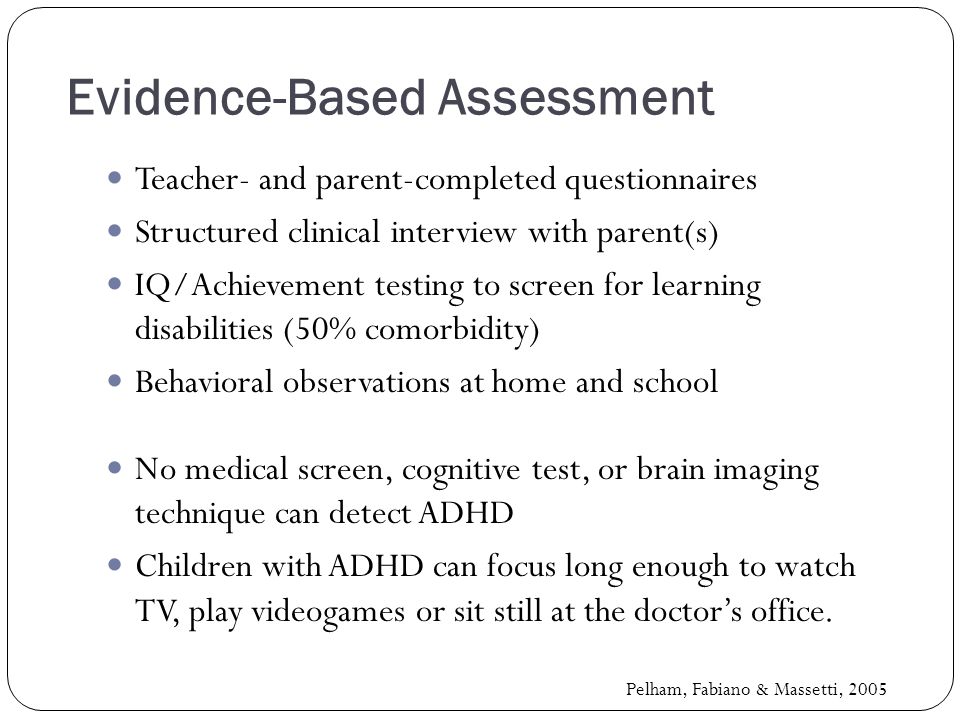

Recommendations for parents, services and administrative policies

Cognitive tests are not yet fine-tuned and narrow enough to be used in the daily practice of diagnosing ADHD. We still need to rely on parent and teacher reports (or self-reports of teenagers and adults with suspected ADHD) for diagnosis. However, recent data from longitudinal studies indicate that childhood EF is predictive of future academic achievement, social functioning, and general functioning in patients with ADHD. 33 As these results suggest, the diagnosis and treatment of EF disorders may be of benefit to clinical practice, especially in cases with a high risk of negative outcome, in order to prevent long-term problems in important areas of life functioning. 33 Strategies for corrective interventions for UV deficiency are still in the early stages of development, but positive results have already been obtained. 34.35 These interventions may be useful for the subgroup of children with ADHD who suffer from moderately severe UV deficiency (+/- 30%).

33 As these results suggest, the diagnosis and treatment of EF disorders may be of benefit to clinical practice, especially in cases with a high risk of negative outcome, in order to prevent long-term problems in important areas of life functioning. 33 Strategies for corrective interventions for UV deficiency are still in the early stages of development, but positive results have already been obtained. 34.35 These interventions may be useful for the subgroup of children with ADHD who suffer from moderately severe UV deficiency (+/- 30%).

Literature

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. 4 th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Faraone S, Biederman J, Mick E. The age dependent decline of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychological Medicine 2006;36(2):159-165.

- Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, Smoller JW, Goralnick JJ, Holmgren MA, Sklar P. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry 2005;57(11):1313-1323.

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW. Neuropsychological assessment . 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004.

- Rommelse NN, Altink ME, Oosterlaan J, Buschgens CJ, Buitelaar J, Sergeant JA. Support for an independent family segregation of executive and intelligence endophenotypes in ADHD families. Psychological Medicine 2008;38(11):1595-1606.

- Castellanos FX, Tannock R. Neuroscience of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the search for endophenotypes. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2002;3(2):617-628.

- Durston S. A review of the biological bases of ADHD: what have we learned from imaging studies? Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 2003;9(3):184-195.

- Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Doyle AE, Seidman LJ, Wilens TE, Ferrero F, Morgan CL, Faraone SV. Impact of executive function deficits and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on academic outcomes in children . Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2004;72(5):757-766.

- Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF. Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2009;37(11):551-564.

- Wåhlstedt C, Thorell LB, Bohlin G. Heterogeneity in ADHD: neuropsychological pathways, comorbidity and symptom domains. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2009;37(4):551-564.

- Nigg JT, Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Sonuga-Barke EJ. Causal heterogeneity in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: do we need neuropsychologically impaired subtypes? Biological Psychiatry 2005;57(11):1224-1230.

- Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Ralano A.

Genetic influences on frontal brain function: WCST performance in twins. Neuroreport 2003;14(15):1975-1978.

Genetic influences on frontal brain function: WCST performance in twins. Neuroreport 2003;14(15):1975-1978. - Taylor J. Heritability of Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) and Stroop Color-Word Test performance in normal individuals: implications for the search for endophenotypes. Twin Research and Human Genetics 2007;10(6):829-834.

- Polderman TJ, Posthuma D, De Sonneville LM, Stins JF, Verhulst FC, Boomsma DI. Genetic analyzes of the stability of executive functioning during childhood. Biological Psychology 2007;76(1-2):11-20.

- Doyle AE, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ, Willcutt EG, Nigg JT, Waldman ID, Pennington BF, Peart J, Biederman J. Are endophenotypes based on measures of executive functions useful for molecular genetic studies of ADHD? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2005;46(7):774-803.

- Polderman TJ, Gosso MF, Posthuma D, Van Beijsterveldt TC, Heutink P, Verhulst FC, Boomsma DI. A longitudinal twin study on IQ, executive functioning, and attention problems during childhood and early adolescence.

Acta Neurologica Belgica 2006;106(4):191-207.

Acta Neurologica Belgica 2006;106(4):191-207. - Seidman L, Biederman J, Monuteaux M, Weber W, Faraone SV. Neuropsychological functioning in nonreferred siblings of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2000;109(2):252-265.

- Nigg JT, Blaskey LG, Stawicki JA, Sachek J. Evaluating the endophenotype model of ADHD neuropsychological deficit: Results for parents and siblings of children with ADHD combined and inattentive subtypes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2004;113(4):614-625.

- Waldman ID, Nigg JT, Gizer IR, Park L, Rappley MD, Friderici K. The adrenergic receptor alpha-2A gene (ADRA2A) and neuropsychological executive functions as putative endophenotypes for childhood ADHD. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience 2006;6(1):18-30.

- Bidwell LC, Willcutt EG, DeFries JC, Pennington BF. Testing for neuropsychological endophenotypes in siblings discordant for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Biological Psychiatry 2007;62(9):991-998.

Biological Psychiatry 2007;62(9):991-998. - Uebel H, Albrecht B, Asherson P, Börger NA, Butler L, Chen W, Christiansen H, Heise A, Kuntsi J, Schäfer U, Andreou P, Manor I, Marco R, Miranda A, Mulligan A, Oades RD, van der Meere J, Faraone SV, Rothenberger A, Banaschewski T. Performance variability, impulsivity errors and the impact of incentives as gender-independent endophenotypes for ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2010;51(2):210-218.

- Slaats-Willemse D, Swaab-Barneveld H, De Sonneville L, Buitelaar J. Familial clustering of executive functioning in affected families sibling pair with ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2005;44(4):385-391.

- Slaats-Willemse D, Swaab-Barneveld H, De Sonneville L, Van der Meulen E, Buitelaar J. Deficient response inhibition as a cognitive endophenotype of ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2003;42(10):1242-1248.

- Crosbie J, Schachar R. Deficient inhibition as a marker for familial ADHD. American Journal of Psychiatry 2001;158(11):1884-1890.

- Schachar RJ, Crosbie J, Barr CL, Ornstein TJ, Kennedy J, Malone M, Roberts W, Ickowicz A, Tannock R, Chen S, Pathare T. Inhibition of motor responses in siblings concordant and discordant for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 2005;162(6):1076-1082.

- Goos LM, Crosbie J, Payne S, Schachar R. Validation and extension of the endophenotype model in ADHD patterns of inheritance in a family study of inhibitory control. American Journal of Psychiatry 2009;166(6):711-717.

- Boonstra AM, Kooij JJS, Buitelaar JK, Oosterlaan J, Sergeant JA, Heister JG, Franke B. An exploratory study of the relationship between four candidate genes and neurocognitive performance in adult ADHD. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 2008;147(3):397-402.

- Altink ME, Rommelse NNJ, Slaats-Willemse DIE, Arias Vasquez A, Franke B, Buschgens CJM, Fliers EA, Faraone SV, Sergeant JA, Oosterlaan J, Buitelaar JK. The dopamine receptor D4 7-repeat allele influences neurocognitive functioning, but this effect is moderated by age and ADHD status. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry . In press.

- Durston S, de Zeeuw P, Staal WG. Imaging genetics in ADHD: a focus on cognitive control. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 2009;33(5):674-689.

- Loo SK, Rich EC, Ishii J, McGough J, McCracken J, Nelson S, Smalley SL. Cognitive functioning in affected sibling pairs with ADHD: familial clustering and dopamine genes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2008;49(9):950-957.

- Rommelse NN, Arias-Vásquez A, Altink ME, Buschgens CJ, Fliers E, Asherson P, Faraone SV, Buitelaar JK, Sergeant JA, Oosterlaan J, Franke B. Neuropsychological endophenotype approach to genome-wide linkage analysis identifies susceptibility loci for ADHD on 2q21.

1 and 13q12.11. American Journal of Human Genetics 2008;83(1):99-105.

1 and 13q12.11. American Journal of Human Genetics 2008;83(1):99-105. - Doyle AE, Ferreira MA, Sklar PB, Lasky-Su J, Petty C, Fusillo SJ, Seidman LJ, Willcutt EG, Smoller JW, Purcell S, Biederman J, Faraone SV. Multivariate genomewide linkage scan of neurocognitive traits and ADHD symptoms: suggestive linkage to 3q13. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 2008;147B(8):1399-1411.

- Miller M, Hinshaw SP. Does childhood executive function predict adolescent functional outcomes in girls with ADHD? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology . In press.

- Papazian O, Alfonso I, Luzondo RJ, Araguez N. Training of executive function in preschool children with combined attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a prospective, controlled and randomized trial. Revista de Neurologia 2009;48(suppl 2):S119-S122.

- Klingberg T, Fernell E, Olesen PJ, Johnson M, Gustafsson P, Dahlström K, Gillberg CG, Forssberg H, Westerberg H.