What is affect in psychology

Affect - IResearchNet

Psychology > Social Psychology > Emotions > Affect

Affect Definition

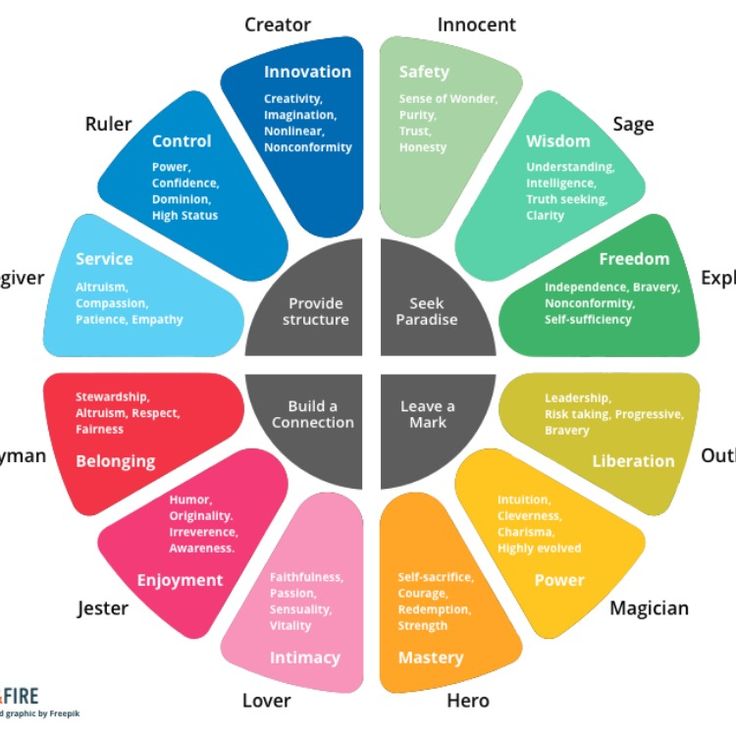

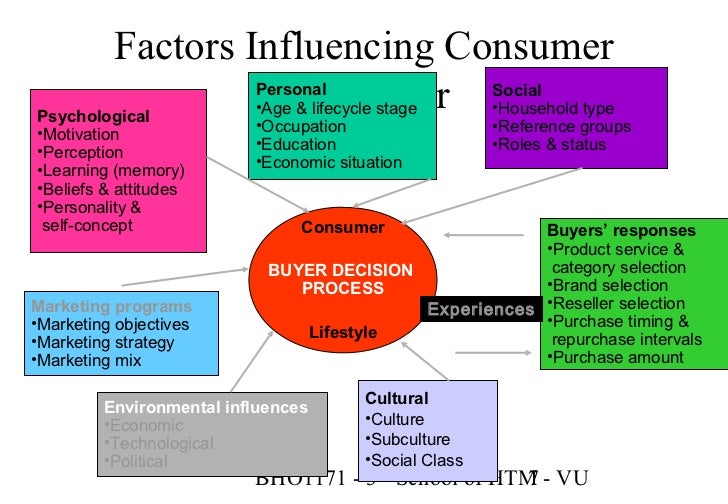

Affect refers to the positive or negative personal reactions or feelings that we experience. Affect is often used as an umbrella term to refer to evaluations, moods, and emotions. Affect colors the way we see the world and how we feel about people, objects, and events. It also has an important impact on our social interactions, behaviors, decision making, and information processing.

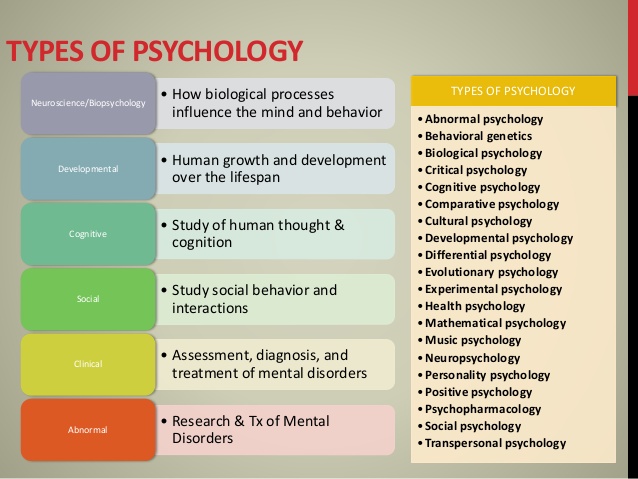

Distinctions among Types of Affect

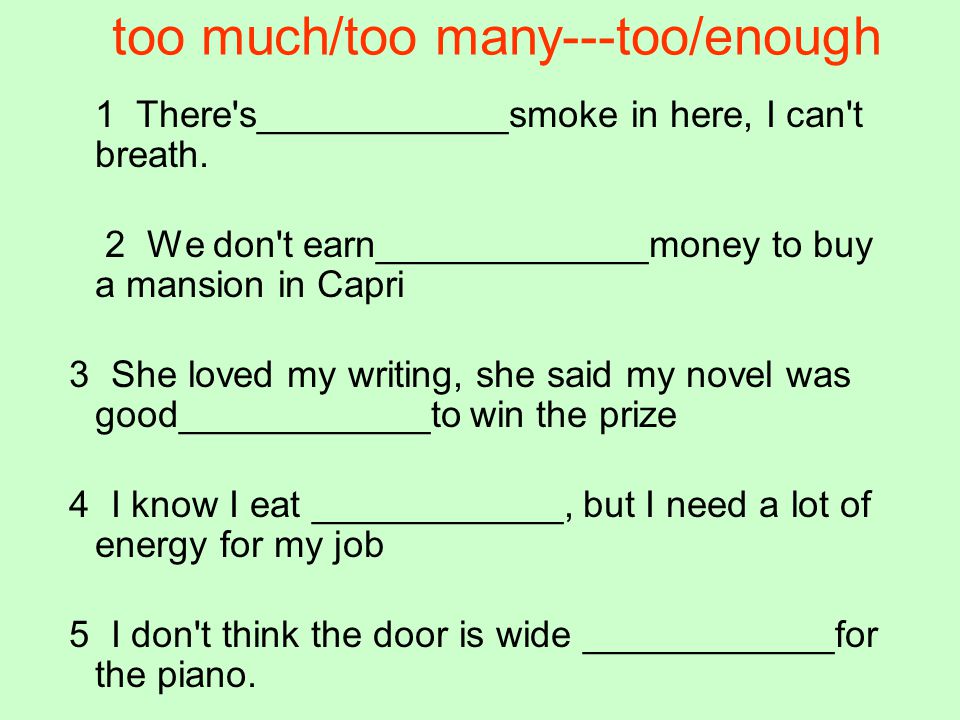

Evaluations are general positive or negative feelings in response to someone or something specific. For example, if you experience negative feelings in response to your new roommate, your evaluation of the person is based upon these feelings. Such evaluations are said to be affect based.

Moods, like evaluations, are also experienced as general positive or negative feelings; however, they are not elicited in response to anyone or anything specific. When you are in a bad mood, you are unable to identify the specific cause of your feelings. For this reason, people sometimes say that they are in a bad mood because they “woke up on the wrong side of the bed.” Moods are not directed toward a person or an object. Thus, for example, while you may have a negative reaction to your roommate, you would not have a negative mood toward your roommate. Moods are like evaluations in that they tend to be relatively long-lasting.

In contrast to both evaluations and moods, emotions are highly specific positive or negative reactions to a particular person, object, or event. Emotions tend to be experienced for relatively short periods of time and generally have shorter durations than moods or evaluations. Emotions tend to be more intense than moods and allow us to describe how feel more clearly than do moods or evaluations. That is, we can specify exactly what type of negative feelings we are experiencing. For example, if your roommate steals your book, you may say that you feel angry, rather than simply say that you feel negatively. Further, other negative emotions (e.g., sadness and fear) can be differentiated from anger by the different situations and circumstances that produced them and how they are experienced.

Further, other negative emotions (e.g., sadness and fear) can be differentiated from anger by the different situations and circumstances that produced them and how they are experienced.

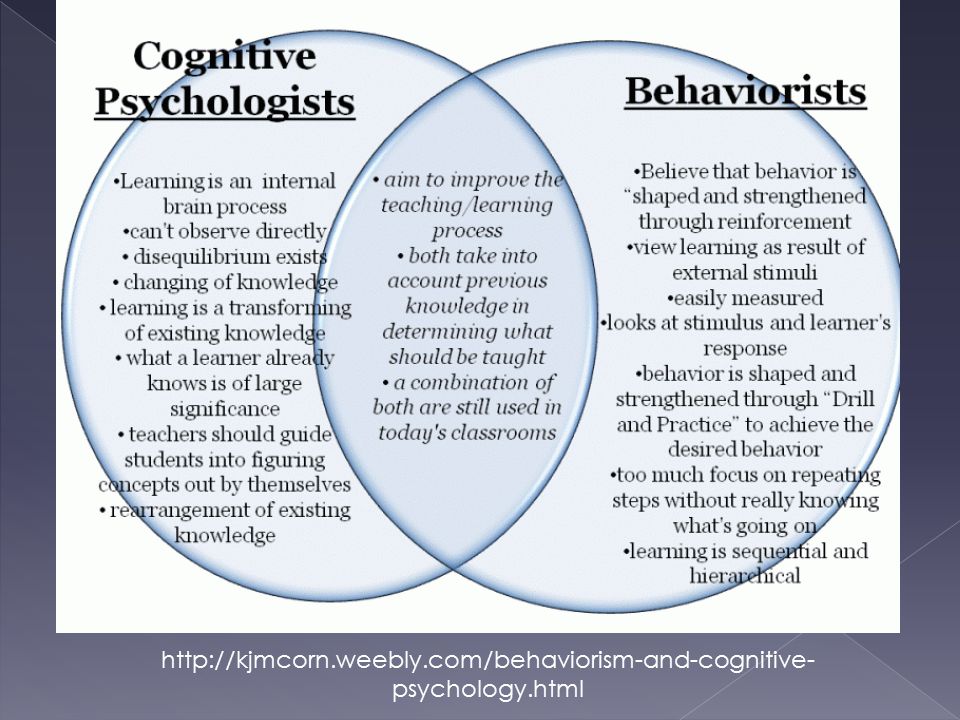

Relationship between Affect and Cognition

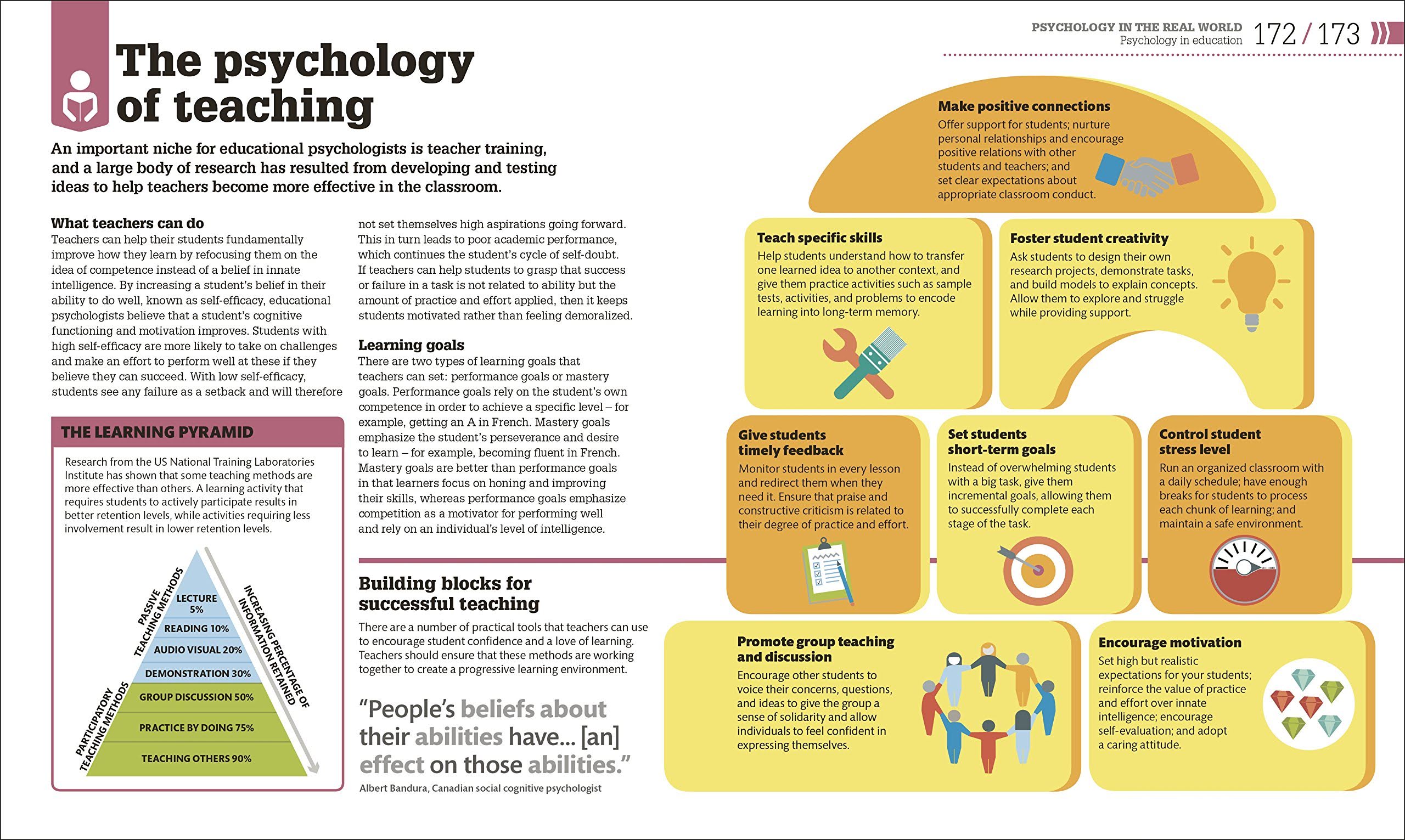

Affect is often contrasted with cognition (i.e., thoughts), but their relationship is not clear-cut. Some researchers believe that affect cannot occur without cognition preceding it, whereas others believe that affect occurs without a preceding cognitive component. Much of this debate has to do with the specific type of affect that individuals are referring to. Many scholars agree that cognition is necessary in order for emotions to be experienced, whereas cognition may not be necessary for individuals to express preferences or evaluations.

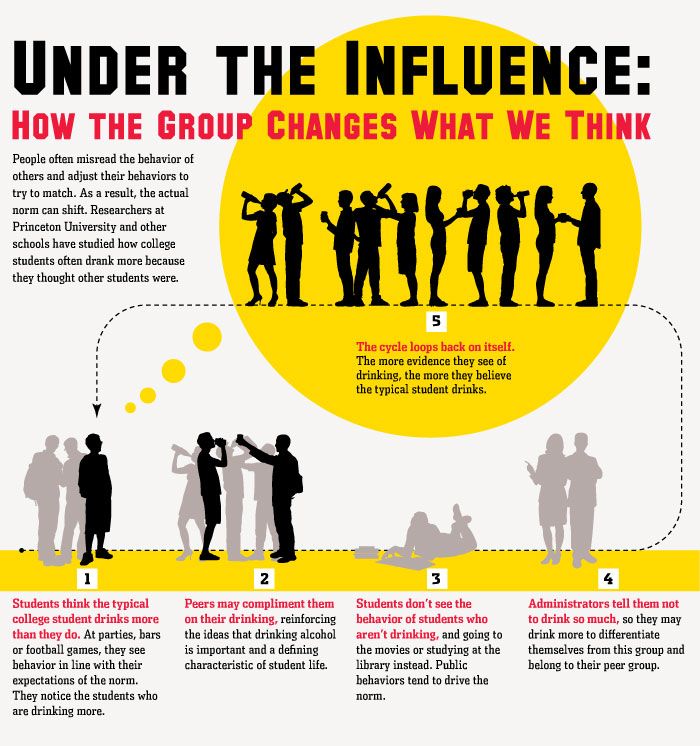

Affect can exert an influence on cognitive processes. For example, one’s affect can influence one’s tendency to use stereotypes. Individuals in happy moods are more likely to use stereotypes when forming impressions of others than are people in sad moods. Further, individuals in happy moods are less influenced by the strength of a persuasive argument than are those in sad moods. Happy moods also lead to increased helping behavior.

Further, individuals in happy moods are less influenced by the strength of a persuasive argument than are those in sad moods. Happy moods also lead to increased helping behavior.

References:

- Lazarus, R. S. (1982). Thoughts on the relations between emotion and cognition. American Psychologist, 37, 1019-1024.

- Wyer, R. S., Clore, G. L., & Isbell, L. M. (1999). Affect and information processing. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 31, pp. 1-77). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist, 35, 151-175.

Affect-as-Information →

Affect (psychology) - wikidoc

Affect, like the adjective affective, refers to the experience of feeling or emotion.[1] Affect is a key part of the process of an organism’s interaction with stimuli. The word also refers sometimes to affect display, which is "a facial, vocal, or gestural behavior that serves as an indicator of affect. " (APA 2006)

" (APA 2006)

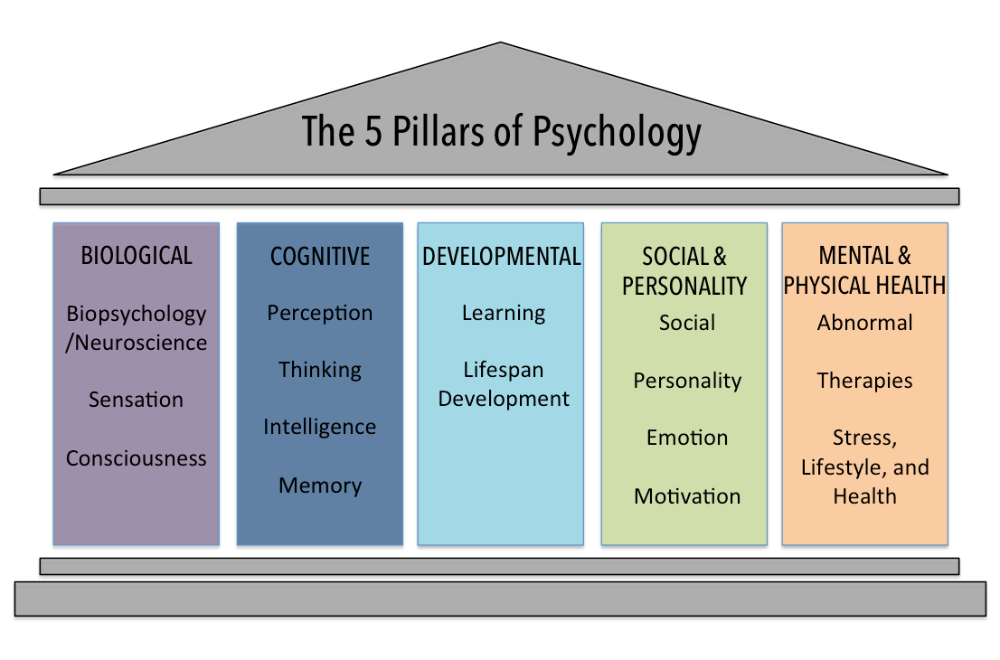

The affective domain represents one of the three classical divisions of psychology: the cognitive, the conative, and the affective. One current psychological theory, the lateralization of brain function, holds that one half of the brain deals mainly with the affective or emotional, while the other half deals mainly with the cognitive or rational. In certain views, the conative may be considered as a part of the affective,[2] or the affective as a part of the cognitive.[3].

This article discusses theoretical perspectives, history and psychological meanings of the term, as well as distinctions between mood and emotion.

Contents

- 1 Theoretical perspective

- 2 History

- 3 Non-conscious affect and perception

- 4 Arousal

- 5 Affect and mood

- 6 Affect and the present moment

- 7 Social interaction

- 8 Meanings in art

- 9 References

- 10 Footnotes

- 11 External Links

- 12 See also

Theoretical perspective

The term "affect" can be taken to indicate an instinctual reaction to stimulation occurring before the typical cognitive processes considered necessary for the formation of a more complex emotion. Robert B. Zajonc asserts this reaction to stimuli is primary for human beings, and that it is the dominant reaction for lower organisms. Zajonc suggests affective reactions can occur without extensive perceptual and cognitive encoding, and can be made sooner and with greater confidence than cognitive judgments (Zajonc, 1980).

Robert B. Zajonc asserts this reaction to stimuli is primary for human beings, and that it is the dominant reaction for lower organisms. Zajonc suggests affective reactions can occur without extensive perceptual and cognitive encoding, and can be made sooner and with greater confidence than cognitive judgments (Zajonc, 1980).

Many theorists (e.g., Lazarus, 1982) consider affect to be post-cognitive. That is, affect is thought to be elicited only after a certain amount of cognitive processing of information has been accomplished. In this view, an affective reaction, such as liking, disliking, evaluation, or the experience of pleasure or displeasure, is based on a prior cognitive process in which a variety of content discriminations are made and features are identified, examined for their value, and weighted for their contributions (Brewin, 1989).

A divergence from a narrow reinforcement model for emotion allows for other perspectives on how affect influences emotional development. Thus, temperament, cognitive development, socialization patterns, and the idiosyncrasies of one's family or subculture are mutually interactive in non-linear ways. As an example, the temperament of a highly reactive/low self-soothing infant may “disproportionately” affect the process of emotion regulation in the early months of life (Griffiths, 1997).

Thus, temperament, cognitive development, socialization patterns, and the idiosyncrasies of one's family or subculture are mutually interactive in non-linear ways. As an example, the temperament of a highly reactive/low self-soothing infant may “disproportionately” affect the process of emotion regulation in the early months of life (Griffiths, 1997).

History

A number of experiments have been conducted in the study of social and psychological affective preferences (i.e., what people like or dislike). Specific research has been done on preferences, attitudes, impression formation, and decision making. This research contrasts findings with recognition memory (old-new judgments), allowing researchers to demonstrate reliable distinctions between the two. Affect-based judgments and cognitive processes have been examined with noted differences indicated, and some argue affect and cognition are under the control of separate and partially independent systems that can influence each other in a variety of ways (Zajonc, 1980). Both affect and cognition may constitute independent sources of effects within systems of information processing. Others suggest emotion is a result of an anticipated, experienced, or imagined outcome of an adaptational transaction between organism and environment, therefore cognitive appraisal processes are keys to the development and expression of an emotion (Lazarus, 1982).

Both affect and cognition may constitute independent sources of effects within systems of information processing. Others suggest emotion is a result of an anticipated, experienced, or imagined outcome of an adaptational transaction between organism and environment, therefore cognitive appraisal processes are keys to the development and expression of an emotion (Lazarus, 1982).

Non-conscious affect and perception

In relation to perception, a type of non-conscious affect may be separate from the cognitive processing of environmental stimuli. A monoheirarchy of perception, affect and cognition considers the roles of arousal, attentional tendencies, affective primacy (Zajonc, 1980), evolutionary constraints (Shepard, 1984; 1994), and covert perception (Weiskrantz, 1997) within the sensing and processing of preferences and discriminations. Emotions are complex chains of events triggered by certain stimuli. There is no way to completely describe an emotion by knowing only some of its components. Verbal reports of feelings are often inaccurate because people may not know exactly what they feel, or they may feel several different emotions at the same time. There are also situations that arise in which individuals attempt to hide their feelings, and there are some who believe that public and private events seldom coincide exactly, and that words for feelings are generally more ambiguous than are words for objects or events.

Verbal reports of feelings are often inaccurate because people may not know exactly what they feel, or they may feel several different emotions at the same time. There are also situations that arise in which individuals attempt to hide their feelings, and there are some who believe that public and private events seldom coincide exactly, and that words for feelings are generally more ambiguous than are words for objects or events.

Affective responses, on the other hand, are more basic and may be less problematical in terms of assessment. Brewin has proposed two experiential processes that frame non-cognitive relations between various affective experiences. Those that are prewired dispositions (i.e.. non-conscious processes), able to “select from the total stimulus array those stimuli that are casually relevant, using such criteria as perceptual salience, spatiotemporal cues, and predictive value in relation to data stored in memory” (Brewin, 1989, p.381), and those that are automatic (i. e.. subconscious processes), characterized as “rapid, relatively inflexible and difficult to modify…(requiring) minimal attention to occur and…(capable of being) activated without intention or awareness” (1989 p.381).

e.. subconscious processes), characterized as “rapid, relatively inflexible and difficult to modify…(requiring) minimal attention to occur and…(capable of being) activated without intention or awareness” (1989 p.381).

Arousal

Arousal is a basic physiological response to the presentation of stimuli. When this occurs, a non-conscious affective process takes the form of two control mechanisms; one mobilization, and the other immobilizing. Within the human brain, the amygdala regulates an instinctual reaction initiating this arousal process, either freezing the individual or accelerating mobilization.

The arousal response is illustrated in studies focused on reward systems that control food-seeking behavior (Balliene, 2005). Researchers focused on learning processes and modulatory processes that are present while encoding and retrieving goal values. When an organism seeks food, the anticipation of reward based on environmental events becomes another influence on food seeking that is separate from the reward of food itself. Therefore, earning the reward and anticipating the reward are separate processes and both create an excitatory influence of reward-related cues. Both processes are dissociated at the level of the amygdale and are functionally integrated within larger neural systems.

Affect and mood

Mood, like emotion, is an affective state. However, an emotion tends to have a clear focus (i.e., its cause is self-evident), while mood tends to be more unfocused and diffused. Mood, according to Batson, Shaw, and Oleson (1992), involves tone and intensity and a structured set of beliefs about general expectations of a future experience of pleasure or pain, or of positive or negative affect in the future. Unlike instant reactions that produce affect or emotion, and that change with expectations of future pleasure or pain, moods, being diffused and unfocused, and thus harder to cope with, can last for days, weeks, months, or even years (Schucman, 1975). Moods are hypothetical constructs depicting an individual's emotional state.

Researchers typically infer the existence of moods from a variety of behavioral referents (Blechman, 1990).

Positive affect and negative affect represent independent domains of emotion in the general population, and positive affect is strongly linked to social interaction. Positive and negative daily events show independent relationships to subjective well-being, and positive affect is strongly linked to social activity. Recent research suggests that high functional support is related to higher levels of positive affect. The exact process through which social support is linked to positive affect remains unclear. The process could derive from predictable, regularized social interaction, from leisure activities where the focus is on relaxation and positive mood, or from the enjoyment of shared activities.

Affect and the present moment

In the book, The Stillness of the Mind, Eckhart focuses on self-awareness and the perception of the present that leads to a cognitive, conscious affective state of the human condition. This present-moment consciousness of affect includes various stimuli processed within the framework of cultures, organizations, and environments, all of which contribute toward the development of the emotional state of the human organism (Tolle, 1999, 2003).

Social interaction

Affect, emotion, or feeling is displayed to others through facial expressions, hand gestures, posture, voice characteristics, and other physical manifestation. These affect displays vary between and within cultures and are displayed in various forms ranging from the most discrete of facial expressions to the most dramatic and prolific gestures (Batson 1992). Affect display is a critical facet of interpersonal communication. Evolutionary psychologists have advanced the hypothesis that hominids have evolved with sophisticated capability of reading affect displays and detecting deception.[citation needed]

Meanings in art

The difference between the externally observable affect and the internal mood has been implicitly accepted in art and indeed, within language itself. The word "giddy," for example, carries within it the connotation that the characterized individual may be displaying a happiness that the speaker/observer believes either insincere or short-living.[citation needed]

References

- APA (2006). VandenBos, Gary R., ed. APA Dictionary of Psychology Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, page 26.

- Balliene, B. W. (2005). Dietary Influences on Obesity: Environment, Behavior and Biology. Physiology & Behavior, 86 (5), pp. 717-730

- Batson, C.D., Shaw, L. L., Oleson, K. C. (1992). Differentiating Affect, Mood and Emotion: Toward Functionally-based Conceptual Distinctions. Emotion. Newbury Park, CA: Sage

- Blechman, E. A. (1990). Moods, Affect, and Emotions. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ

- Brewin, C. R. (1989). Cognitive Change Processes in Psychotherapy. Psychological Review, 96(45), pp. 379-394

- Griffiths, P.

E. (1997). What Emotions Really Are: The Problem of Psychological Categories. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago

- Lazarus, R. S. (1982). Thoughts on the Relations between Emotions and Cognition. American Physiologist, 37(10), pp. 1019-1024

- Schucman, H., Thetford, C. (1975). A Course in Miracle. New York: Viking Penguin

- Shepard, R. N. (1984). Ecological Constraints on Internal Representation. Psychological Review, 91, pp. 417-447

- Shepard, R. N. (1994). Perceptual-cognitive Universals as Reflections of the World. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 1, pp. 2-28.

- Tolle, E. (1999). The Power of Now. Vancouver: Namaste Publishing.

- Tolle, E. (2003). Stillness Speaks. Vancouver: Namaste Publishing

- Weiskrantz, L. (1997). Consciousness Lost and Found. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feelings and Thinking: Preferences Need No Inferences. American Psychologist, 35(2), pp.

151-175

Footnotes

- ↑ See The Affective System: a webpage by Dr. William Huitt.

- ↑ See Affective science: affective determinants include motives, attitudes, moods, and emotions.

- ↑ See Cognition in mainstream psychology

External Links

- Personality and the Structure of Affective Responses

See also

- Affective science

- Affective neuroscience

- Affective spectrum

- Emotion

- Feeling

af:Affek bg:Афект de:Affekt et:Afekt lt:Afektas nl:Affect sk:Afektivita sr:Афект sv:Affekt uk:Афект

Template:WikiDoc Sources

What is affect, or why we can't always stop - T&P

"Theories and Practices" continues to explain the meaning of commonly used expressions that are often used in colloquial speech in the wrong sense. In this issue, what quality, according to Plato, united all the warriors, how emotions affect our memory, and what must happen in the soul of the killer in order for his sentence to be commuted.

The expression "state of passion" has passed from criminal and psychiatric practice into our everyday life. But how does an affect differ from an ordinary emotion, and in what cases does it turn into a pathology? To use this term correctly, let us recall its origin and the history of its interpretations in psychology and philosophy.

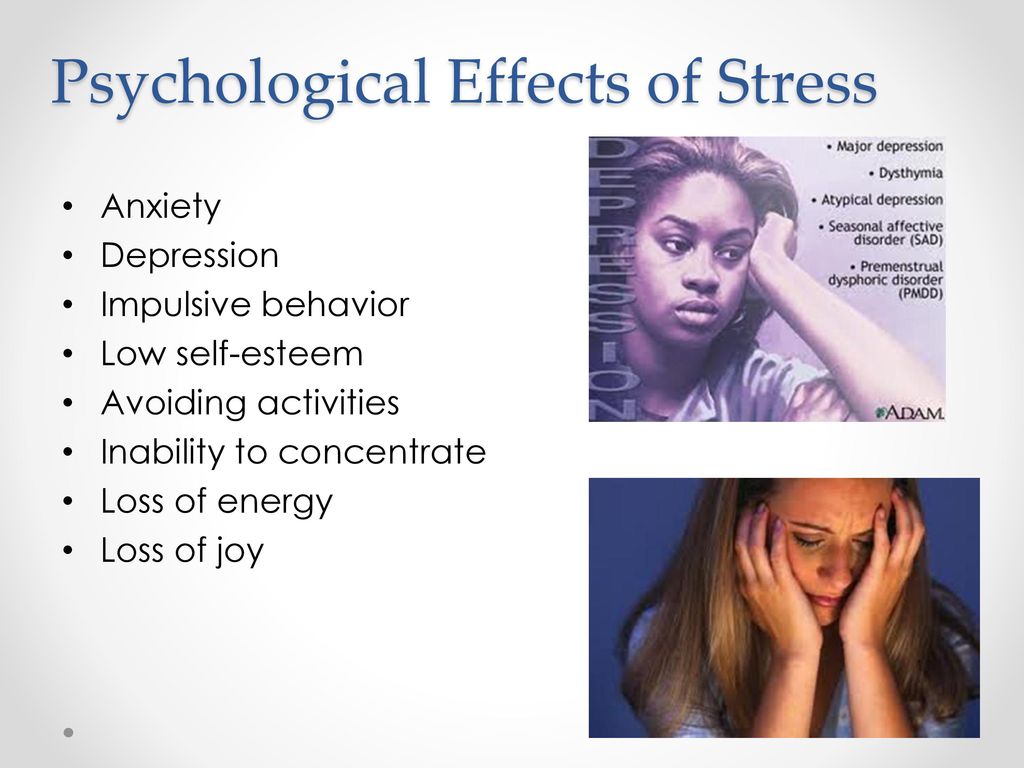

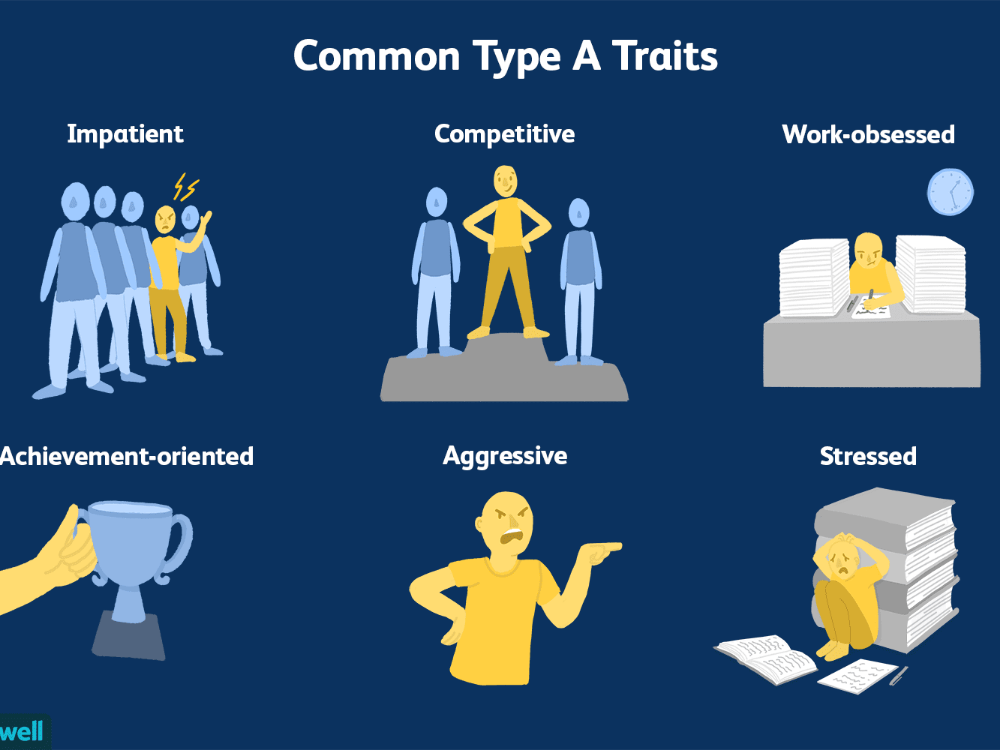

Emotion is a psychophysiological process that reflects an unconscious personal assessment of the current situation. Positive changes cause us joy, troubles - sadness or irritation, someone else's aggression - anger or fear. And affect is a very intense emotional state that does not last long, but causes pronounced somatic manifestations - changes in pulse and breathing, spasm of peripheral blood vessels, increased sweating, and impaired coordination of movements. The very name "affect" comes from the Latin word affectus, meaning "mental excitement, passion."

Even the ancient Greeks were interested in the state of affect — for example, Plato considered it one of the innate spiritual principles, including lust and reason

Depending on the type of influence, affects are divided into sthenic (from ἀσθένεια - impotence). Stenic affects - anger, delight - encourage active activity, and contribute to the mobilization of forces. And asthenic affects - melancholy, horror, impotence - relax or paralyze any activity. If the situations that cause affect are periodically repeated, the tension gradually accumulates, which can subsequently lead to a violent "explosion". This state is called cumulative affect (not to be confused with the cumulative effect, which is also associated with the accumulation process, but concerns not only emotions).

But the states of affect of a person who slammed his fist on the table out of anger, and a person who killed someone in a fit of rage, and now does not remember how it happened, are very different. The first option is the so-called physiological affect, which is natural for homo sapiens and is not accompanied by a loss of self-control. Usually we hit the table because we understand that it will help us to blow off steam - but under certain conditions we could refrain from it. Much more dangerous is the pathological affect caused by a disruption in the normal functioning of the psyche - this is a short-term (up to 30-40 minutes) psychotic state, during which consciousness is clouded, the person begins to behave on "autopilot" and can no longer stop. This state stops as suddenly as it began, and after that the subject feels a sharp exhaustion, falls into prostration and often does not remember what happened to him during the period of "falling out of reality". Everything that was done in a state of passion, the patient often perceives afterwards as being done by someone else. A good film illustration of a pathological affect is the Hulk: a green monster occurs when a hero has a certain degree of psychological stress, which can be tracked by physical indicators.

Much more dangerous is the pathological affect caused by a disruption in the normal functioning of the psyche - this is a short-term (up to 30-40 minutes) psychotic state, during which consciousness is clouded, the person begins to behave on "autopilot" and can no longer stop. This state stops as suddenly as it began, and after that the subject feels a sharp exhaustion, falls into prostration and often does not remember what happened to him during the period of "falling out of reality". Everything that was done in a state of passion, the patient often perceives afterwards as being done by someone else. A good film illustration of a pathological affect is the Hulk: a green monster occurs when a hero has a certain degree of psychological stress, which can be tracked by physical indicators.

From a legal point of view, a proven pathological affect is a mitigating circumstance: according to the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, the maximum punishment for killing a person in such a state does not exceed three years in prison. But the physiological affect is unlikely to pity the judge - it is taken into account only in the "cumulative" case, when a person endured the victim's illegal or immoral behavior for a long time and finally lost his temper.

But the physiological affect is unlikely to pity the judge - it is taken into account only in the "cumulative" case, when a person endured the victim's illegal or immoral behavior for a long time and finally lost his temper.

Even the ancient Greeks were interested in the state of passion - for example, Plato considered it to be one of the innate mental principles, including also lust and reason. Three parts of the human soul correspond to three estates in an ideal state: if a person’s character was dominated by a tendency to affects, he should have devoted himself to military affairs, the dominant of reason formed the estate of rulers-philosophers, and desires formed the estate of peasants, artisans and merchants. One way or another, the affect was considered lower in comparison with the mind, the beginning, clouding the consciousness and therefore dangerous. It was assumed that passions should be fought with the help of willpower and reasoning arguments. The Christian concept of working on oneself also involved controlling emotions.

A shift in the perception of this state occurred when Descartes and then Spinoza started talking about the role of the relationship between the soul and the body during strong emotions. Descartes in his "Passion of the Soul" suggested that intense emotional states reflect both mental and physiological processes, and Spinoza went even further, concluding that it is impossible to influence intense emotions with the help of pure reason - affect can only be destroyed by a stronger one. affect. “The true knowledge of good and evil, inasmuch as it is true, cannot hinder any affect; it is capable of this only insofar as it is considered as an affect, ”the philosopher believed. True, in Spinoza, the term "affect" has a broader meaning and unites any changes in the body (including the mind) that have arisen as a result of interaction with the outside world.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the concept of affect underwent an even more serious reappraisal. Scientists of the French sociological school Emile Durkheim and Marcel Mauss found out that the influence of society on the perception of an individual directly depends on the strength of affectation. And the French anthropologist Lucien Lévy-Bruhl found that the evoking of affect was of great importance in ancient rituals like initiation and sacrifice. He believed that primitive thinking was very different from modern logical thinking in that emotions played a much greater role in it.

And the French anthropologist Lucien Lévy-Bruhl found that the evoking of affect was of great importance in ancient rituals like initiation and sacrifice. He believed that primitive thinking was very different from modern logical thinking in that emotions played a much greater role in it.

Freud was also interested in affects - he concluded that repressed affects cause mental illness: they remain in the subconscious of a person and continue to vaguely disturb him. Sometimes they are expressed in physical symptoms - paralysis, pain and other involuntary sensations.

How to say

Wrong "A series of agreed measures will give us a good cumulative effect." That's right - "cumulative effect".

Correct “You cannot make the right decision when you are in a state of passion. Sit down, calm down and think it over."

Correct "Sometimes emotions increase productivity - yesterday Sasha redid a bunch of things for joy."

Varlamova Daria

Tags

#vocabulary

#affect

-

91 071

What is "Affect"? The concept and definition of the term "Affect" - Glossary

What is "Affect"? The concept and definition of the term "Affect" - Glossary Glossary. Psychological dictionary.

- A

- B

- B

- D

- D

- F

- Z

- and

- K

- L

- M

- H

- O

- P

- P

- C

- T

- W

- F

- X

- C

- H

- W

- E

- I

Affect (from Latin affectus - emotional excitement, passion) is a strong and relatively short-term emotional experience, which can be accompanied by sharp motor and internal mental manifestations.

Also, affect is understood as a special kind of emotional phenomena, which are distinguished by great strength and the ability to suppress, inhibit all other mental processes, imposing a certain type of reaction. Such behavioral reactions arose in an evolutionary way as a way of "emergency" resolution of a problem situation. The peculiarity of the experience of affects in a person, unlike animals, is also that an affective reaction in a person can occur not only in connection with biological instincts and needs, but also in violation of his social relations (insult, injustice, etc.). )

The peculiarity of the experience of affects in a person, unlike animals, is also that an affective reaction in a person can occur not only in connection with biological instincts and needs, but also in violation of his social relations (insult, injustice, etc.). )

An important function of affects is the accumulation of affective experience (affective traces), which is deposited in the unconscious. Affective memory manifests itself at the moment of a collision of a person who has experienced an affect with individual elements that gave rise to a once similar situation, signaling its possible repetition.

Since affects can arise in extreme conditions, when a person is not able to find a way out of a dangerous, most often unexpected situation, he reacts typically: flight, aggression, etc., although usually such methods justify themselves only in biological conditions.

As a result of repeated repetition of a situation that causes negative experiences, affect accumulates.