Treatment of attachment disorder

Reactive attachment disorder - Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis

A pediatric psychiatrist or psychologist can conduct a thorough, in-depth examination to diagnose reactive attachment disorder.

Your child's evaluation may include:

- Direct observation of interaction with parents or caregivers

- Details about the pattern of behavior over time

- Examples of the behavior in a variety of situations

- Information about interactions with parents or caregivers and others

- Questions about the home and living situation since birth

- An evaluation of parenting and caregiving styles and abilities

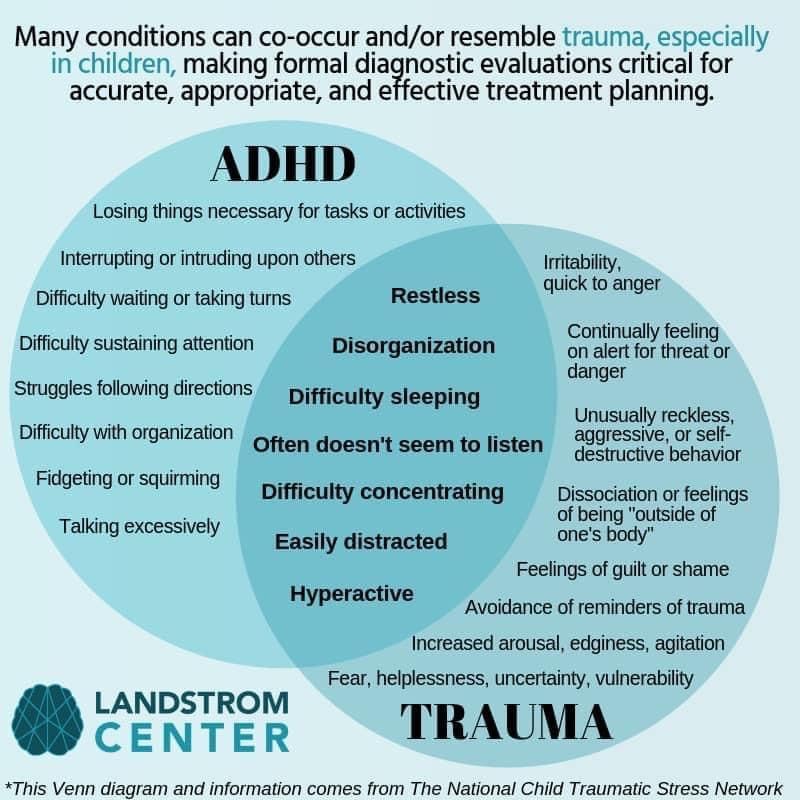

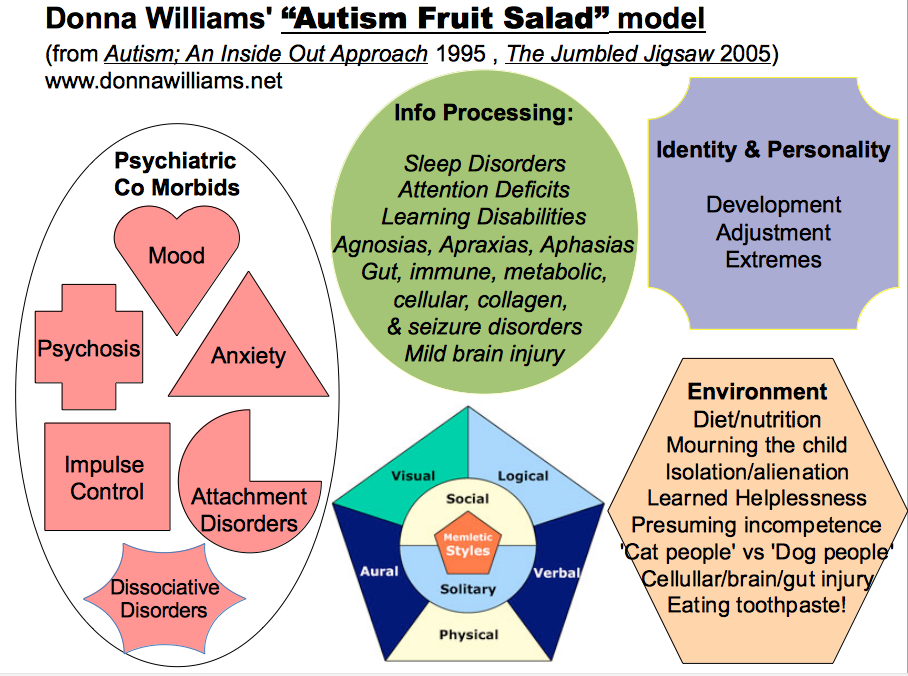

Your child's mental health provider will also want to rule out other psychiatric disorders and determine if any other mental health conditions coexist, such as:

- Intellectual disability

- Adjustment disorders

- Autism spectrum disorder

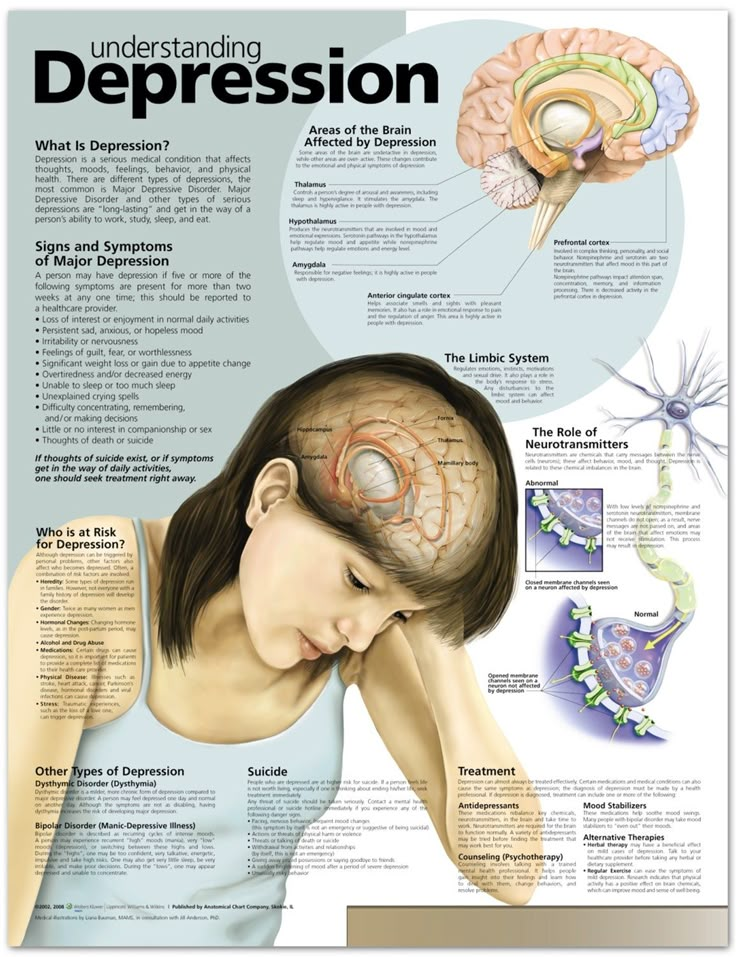

- Depressive disorders

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

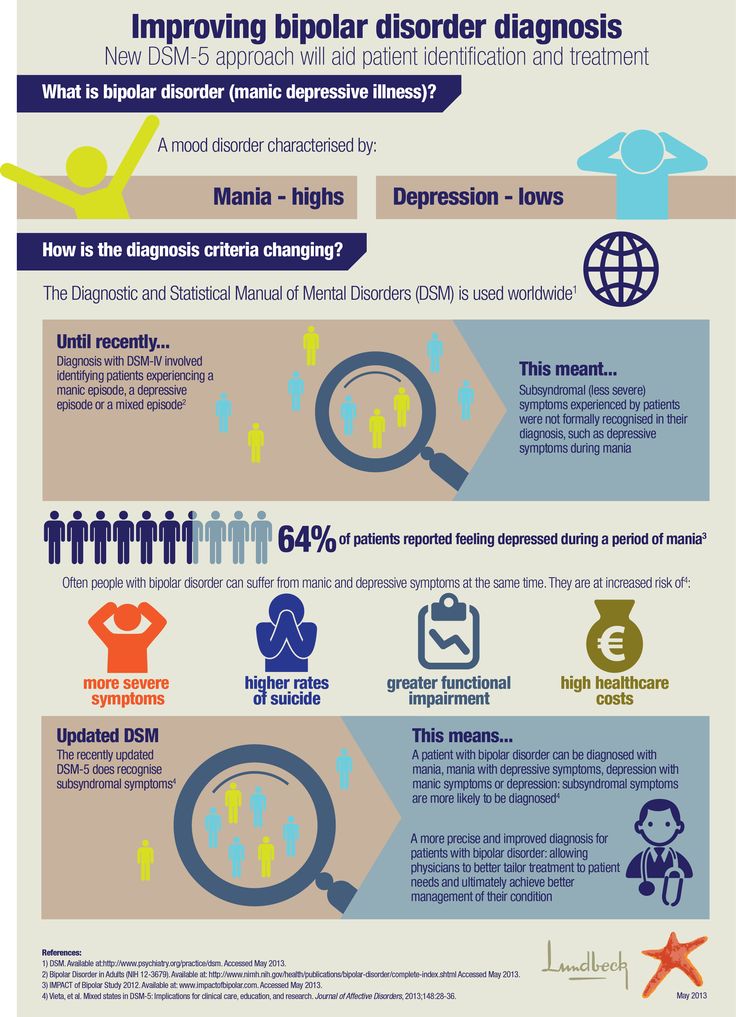

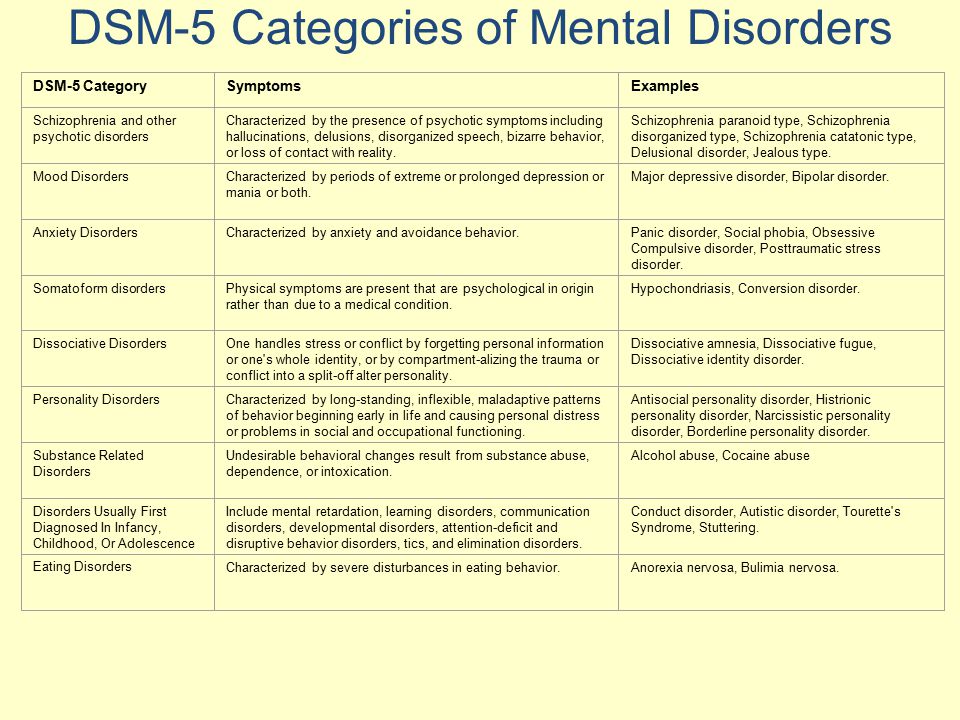

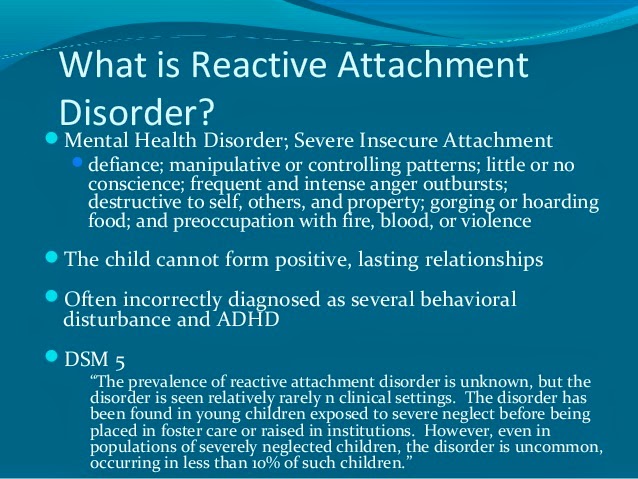

Your child's mental health provider may use the diagnostic criteria for reactive attachment disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association. Diagnosis isn't usually made before 9 months of age. Signs and symptoms typically appear before the age of 5 years.

DSM-5 criteria for diagnosis include:

- A consistent pattern of emotionally withdrawn behavior toward caregivers, shown by rarely seeking or not responding to comfort when distressed

- Persistent social and emotional problems that include minimal responsiveness to others, no positive response to interactions, or unexplained irritability, sadness or fearfulness during interactions with caregivers

- Persistent lack of having emotional needs for comfort, stimulation and affection met by caregivers, or repeated changes of primary caregivers that limit opportunities to form stable attachments, or care in a setting that severely limits opportunities to form attachments (such as an institution)

- No diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder

Treatment

Children with reactive attachment disorder are believed to have the capacity to form attachments, but this ability has been hindered by their early developmental experiences.

Most children are naturally resilient. And even those who've been neglected, lived in a children's home or other institution, or had multiple caregivers can develop healthy relationships. Early intervention appears to improve outcomes.

There's no standard treatment for reactive attachment disorder, but it should involve both the child and parents or primary caregivers. Goals of treatment are to help ensure that the child:

- Has a safe and stable living situation

- Develops positive interactions and strengthens the attachment with parents and caregivers

A mental health professional can provide both education and coaching in skills that help improve signs and symptoms of reactive attachment disorder. Treatment strategies include:

- Encouraging the child's development by being nurturing, responsive and caring

- Providing consistent caregivers to encourage a stable attachment for the child

- Providing a positive, stimulating and interactive environment for the child

- Addressing the child's medical, safety and housing needs, as appropriate

Other services that may benefit the child and the family include:

- Individual and family psychological counseling

- Education of parents and caregivers about the condition

- Parenting skills classes

Controversial and coercive techniques

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has criticized dangerous and unproven treatment techniques for reactive attachment disorder.

These techniques include any type of physical restraint or force to break down what's believed to be the child's resistance to attachments — an unproven theory of the cause of reactive attachment disorder. There is no scientific evidence to support these controversial practices, which can be psychologically and physically damaging and have led to accidental deaths.

If you're considering any kind of unconventional treatment, talk to your child's psychiatrist or psychologist first to make sure it's evidence based and not harmful.

More Information

- Family therapy

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

Coping and support

If you're a parent or caregiver whose child has reactive attachment disorder, it's easy to become angry, frustrated, guilty and distressed. You may feel like your child doesn't love you — or that it's hard to like your child sometimes.

These actions may help:

- Educate yourself and your family about reactive attachment disorder.

Ask your pediatrician or your child's mental health professional about resources or check trusted internet sites. If your child has a background that includes institutions or foster care, consider checking with relevant social service agencies for educational materials and resources.

Ask your pediatrician or your child's mental health professional about resources or check trusted internet sites. If your child has a background that includes institutions or foster care, consider checking with relevant social service agencies for educational materials and resources. - Find someone who can give you a break from time to time. It can be exhausting caring for a child with reactive attachment disorder. You'll begin to burn out if you don't periodically have downtime. But avoid using multiple caregivers. Choose a caregiver who is nurturing and familiar with reactive attachment disorder or educate the caregiver about the disorder.

- Practice stress management skills. For example, learning and practicing yoga or meditation may help you relax and not get overwhelmed.

- Make time for yourself. Develop or maintain your hobbies, social engagements and exercise routine.

- Acknowledge that it's OK to feel frustrated, angry or guilty at times.

The strong feelings you may have about your child are natural. But if needed, seek professional help.

The strong feelings you may have about your child are natural. But if needed, seek professional help.

Preparing for your appointment

You may start by visiting your child's pediatrician. However, you may be referred to a child psychiatrist or psychologist who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of reactive attachment disorder or a pediatrician specializing in child development.

Here's some information to help you get ready and know what to expect from your health care provider or mental health professional.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list of:

- Any behavior problems or emotional issues you've noticed, and include any signs or symptoms that may seem unrelated to the reason for your child's appointment

- Approaches or treatments you've tried, including how helpful or not helpful they have been.

- Key personal information, including any major stresses or life changes that you or your child have been through

- All medications, vitamins, herbal remedies or other supplements your child is taking, including the dosages

- Questions to ask your child's health care provider or mental health professional

Some basic questions to ask may include:

- What is likely causing my child's behavior problems or emotional issues?

- Are there other possible causes?

- What kinds of tests does my child need?

- What are the best treatments?

- What are the alternatives to the primary approach that you're suggesting?

- My child has these other mental or physical health conditions.

How can I best manage them together?

How can I best manage them together? - Are there any restrictions that my child needs to follow?

- Should I take my child to see other specialists?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you recommend?

- Are there social services or support groups available to parents in my situation?

- If medication is recommended, is there a generic alternative to the medicine you're prescribing for my child?

What to expect from your doctor

Your child's health care provider or mental health professional is likely to ask you a number of questions, such as:

- When did you first notice problems with your child's behavior or emotional responses?

- Have your child's behavioral or emotional issues been continuous or occasional?

- How are your child's behavioral or emotional issues interfering with his or her ability to function or interact with others?

- Can you describe your child's and the family's home and living situation since birth?

- Can you describe interactions with your child, both positive and negative?

- What approaches have you tried that have been helpful or unhelpful?

Your health care provider or mental health professional will ask additional questions based on your responses, symptoms and needs. Preparing and anticipating questions will help you make the most of your appointment time.

Preparing and anticipating questions will help you make the most of your appointment time.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

Products & Services

Attachment Disorders in Children: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment

childhood issues

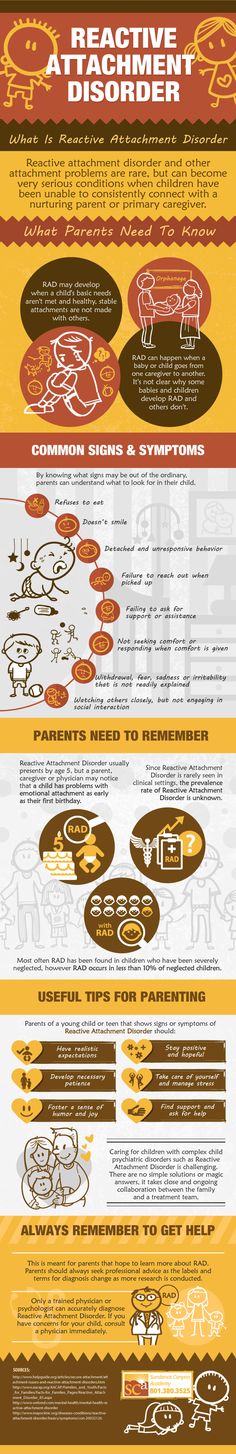

Parenting a child with reactive attachment disorder or disinhibited social engagement disorder can be challenging. But there are ways to address attachment issues and shape your child’s development.

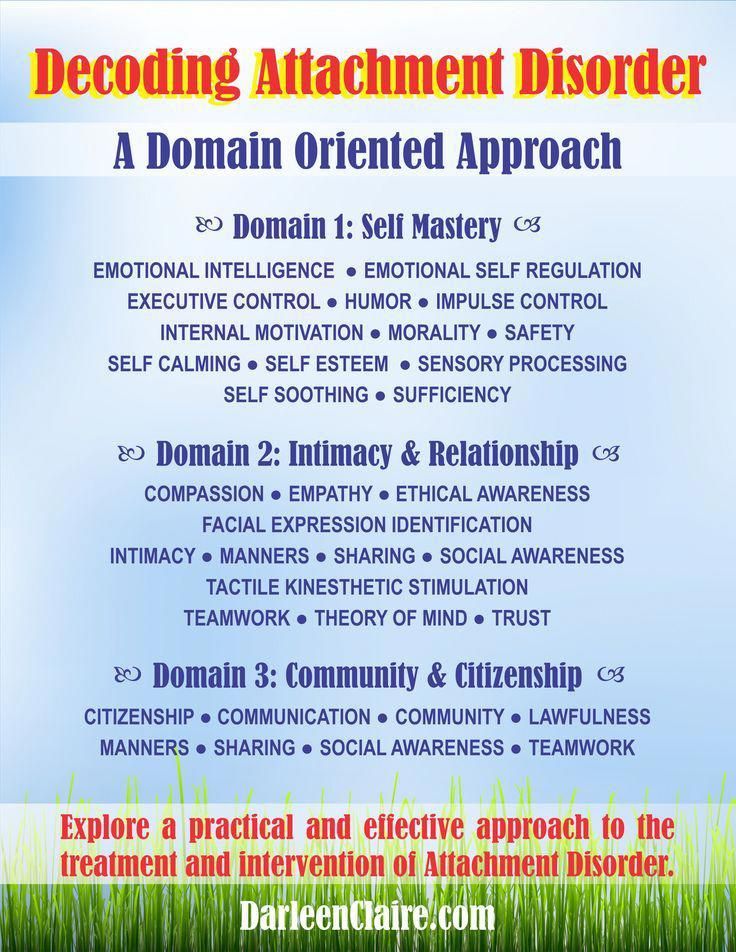

What are attachment disorders?

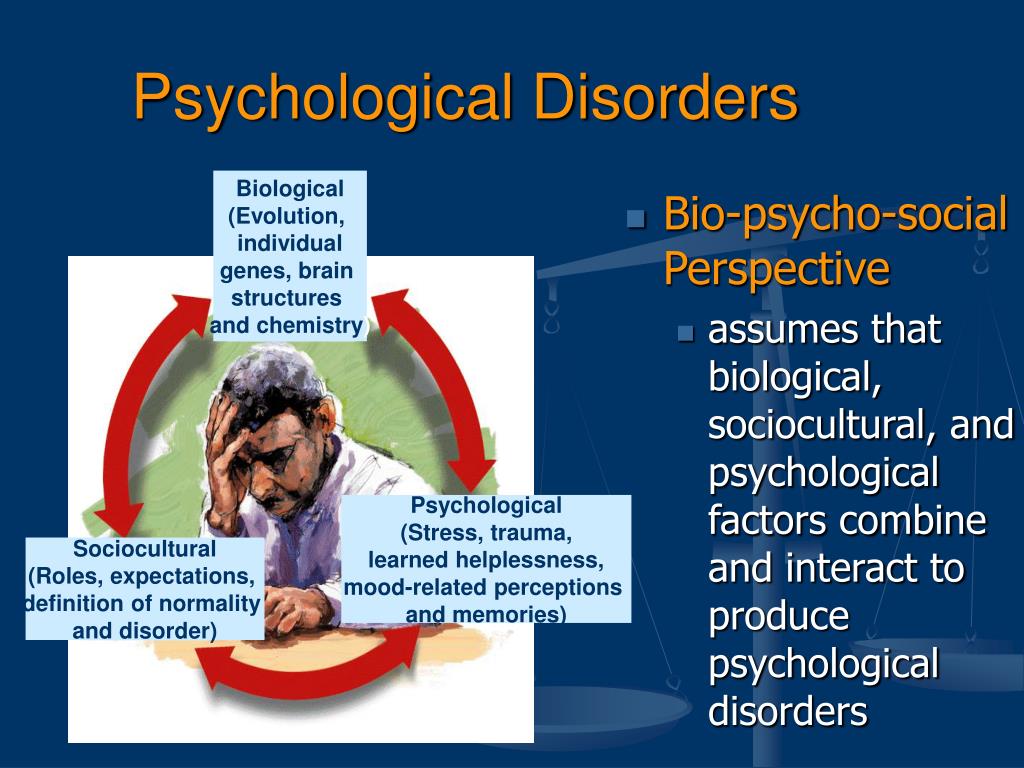

Attachment disorders are conditions that can develop in young children who have issues establishing a deep emotional connection—known as the attachment bond—with their parent or primary caregiver. Since the quality of the attachment bond profoundly impacts your child’s development, experiencing attachment issues can affect their ability to express emotions, develop trust and security, and build meaningful relationships later in life.

Children who have attachment issues tend to fall on a spectrum, from mild problems that are easily addressed to one of two distinct attachment disorders recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5): reactive attachment disorder (RAD) and disinhibited social engagement disorder (DSED).

Both types of attachment disorder are common in young children who have been traumatized, abused, bounced around in foster care, lived in orphanages, or separated from their primary caregiver after establishing a bond. These children may have difficulty relating to others and are often developmentally delayed.

However, no matter how detached or insecure your child seems, or how frustrated or exhausted you feel from trying to connect, it is possible to repair an attachment disorder. With the right tools—and a healthy dose of patience and love—you can bond with your child and help them develop healthy, meaningful, and loving relationships.

[Read: What is Secure Attachment and Bonding?]

Reactive attachment disorder (RAD)

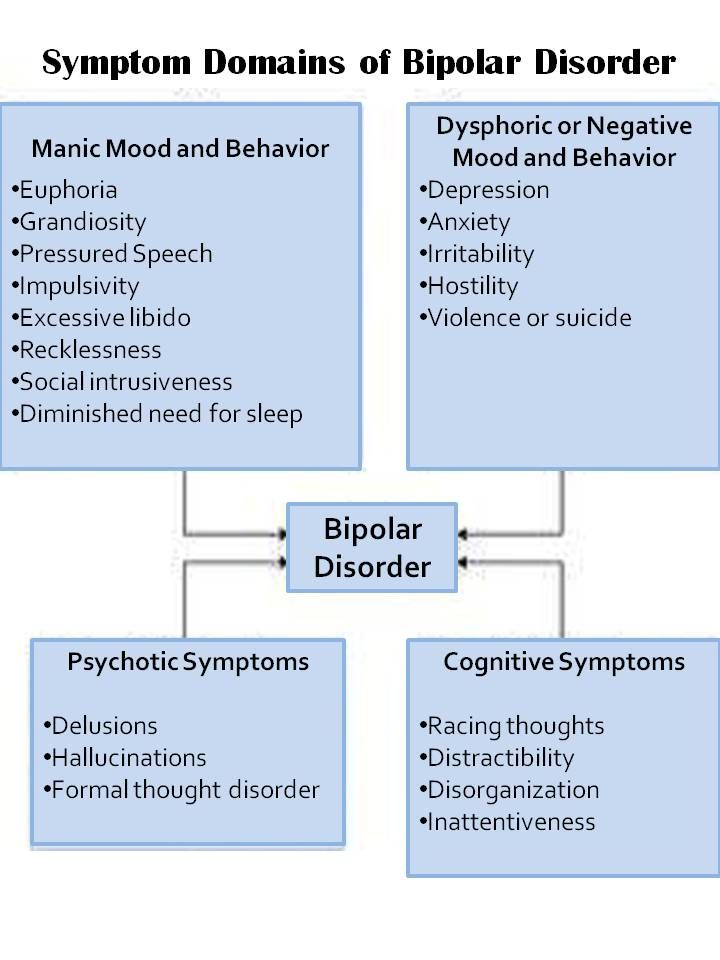

Reactive attachment disorder (RAD) can make it difficult to connect with others and manage emotions. This can result in a lack of trust and self-worth, a fear of getting close to anyone, anger, and a need to be in control.

A child with RAD rarely seeks comfort when distressed and often feels unsafe and alone. They may be extremely withdrawn, emotionally detached, and resistant to comforting. Even though the child is aware of what’s going on around them—hypervigilant even—they don’t react or respond. They may push others away, ignore them, or even act out aggressively when others try to get close.

They may be extremely withdrawn, emotionally detached, and resistant to comforting. Even though the child is aware of what’s going on around them—hypervigilant even—they don’t react or respond. They may push others away, ignore them, or even act out aggressively when others try to get close.

Disinhibited social engagement disorder (DSED)

With disinhibited social engagement disorder (DSED), a child doesn’t seem to prefer their parents over other people, even strangers. They’ll seek comfort and attention from virtually anyone, without distinction, and don’t exhibit any distress when a parent isn’t present.

While they are overly familiar with strangers, children with DSED often have trouble forming meaningful connections with others. They also tend to be extremely dependent, act much younger than their age, and can appear chronically anxious. Having DSED can also put a child at increased risk of harm from strangers.

With over 25,000 licensed counselors, BetterHelp has a therapist that fits your needs. Sign up today and get matched.

Sign up today and get matched.

GET 20% OFF

Attachment disorder causes

Attachment disorders occur when a child has been unable to consistently connect with a parent or primary caregiver. If a young child repeatedly feels abandoned, isolated, powerless, or uncared for—whatever the reason—they will learn that they can't depend on others and that the world is a dangerous and frightening place.

This can happen for many reasons:

- A baby cries and no one responds or offers comfort.

- A baby is hungry or wet, and they aren't attended to for hours.

- No one looks at, talks to, or smiles at the baby, so the baby feels alone.

- A young child gets attention only by acting out or displaying other extreme behaviors.

- An infant or young child is mistreated, traumatized, or abused.

- Sometimes a child's needs are met and sometimes they aren't. The child never knows what to expect.

- An infant or young child is hospitalized or separated from their parents.

- A baby or youngster is moved from one caregiver to another (the result of adoption, foster care, or the loss of a parent, for example).

- The parent is emotionally unavailable because of depression, illness, or substance abuse.

[Read: Child Abuse and Neglect]

Sometimes the circumstances that cause attachment problems are unavoidable, but the child is too young to understand what has happened and why. To a young child, it just feels like no one cares. They lose trust in others and the world becomes an unsafe place.

Although it is never too late to treat and repair attachment issues, the earlier you spot the symptoms of insecure attachment and take steps to repair them, the better. Caught in infancy before they become more serious problems, attachment disorders are often easy to correct with the right help and support.

[Read: Building a Secure Attachment Bond with Your Baby]

Your infant may have attachment issues if they:

- Avoid eye contact.

- Don't smile.

- Don't reach out to be picked up.

- Reject your efforts to calm, soothe, and connect with them.

- Don't seem to notice or care when you leave them alone.

- Cry inconsolably.

- Don't coo or make sounds.

- Don't follow you with their eyes.

- Aren't interested in playing interactive games or playing with toys.

- Spend a lot of time rocking or comforting themselves.

It's important to note that the early symptoms of attachment disorders are similar to the early symptoms of other issues such as ADHD and autism. If you spot any of these warning signs, make an appointment with your pediatrician for a professional diagnosis of the problem.

Comforting a crying baby

It's common to feel frustration, anxiety, and even anger when faced with a crying baby—especially if your baby wails for hours on end. In these situations, you need to remain calm and centered so you'll be better able to figure out what's going on with your child and how best to soothe their cries.

Common signs and symptoms in young children include:

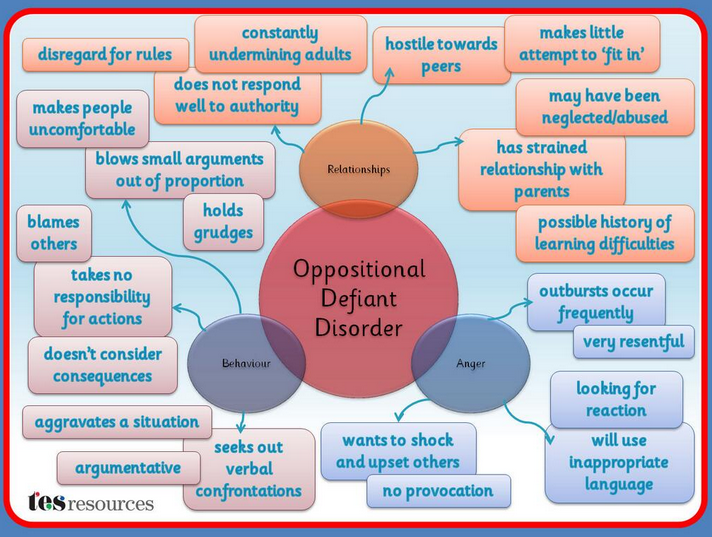

An aversion to touch and physical affection. Children with reactive attachment disorder often flinch, laugh, or even say “ouch” when touched. Rather than producing positive feelings, touch and affection are perceived as a threat.

Control issues. Most children with reactive attachment disorder go to great lengths to remain in control and avoid feeling helpless. They are often disobedient, defiant, and argumentative.

Anger problems. Anger may be expressed directly, in tantrums or acting out, or through manipulative, passive-aggressive behavior. Children with RAD, for example, may hide their anger in socially acceptable actions, like giving a high five that hurts or hugging someone too hard.

Difficulty showing genuine care and affection. For example, children with disinhibited social engagement disorder may act inappropriately affectionately with strangers while displaying little or no affection towards their parents.

Lack of inhibition. A child with DSED, for example, may be overly talkative or physical with unfamiliar adults, excited to interact or even leave with strangers, and fearless about places or situations that are strange or threatening.

An underdeveloped conscience. Children with reactive attachment disorder may act like they don't have a conscience and fail to show guilt, regret, or remorse after behaving badly. There’s evidence that left untreated attachment disorders may even lead to personality disorders in adulthood.

Parenting a child with attachment issues

Parenting a child with insecure attachment or an attachment disorder can be exhausting, frustrating, and emotionally trying. It is hard to put your best parenting foot forward without the reassurance of a loving connection with your child. Sometimes you may wonder if your efforts are worth it, but be assured that they are.

With time, patience, and concerted effort, attachment disorders can be repaired. The key is to remain calm, yet firm as you interact with your child. This will teach your child that they are safe and can trust you.

The key is to remain calm, yet firm as you interact with your child. This will teach your child that they are safe and can trust you.

A child with an attachment disorder is already experiencing a great deal of stress, so it is imperative that you evaluate and manage your own stress levels before trying to help your child with theirs. HelpGuide's free Emotional Intelligence Toolkit can teach you valuable skills for managing stress and dealing with overwhelming emotions, leaving you to focus on your child's needs.

To help a child with attachment issues, it's also important to:

Have realistic expectations. Helping your child may be a long road. Focus on making small steps forward and celebrate every sign of success.

Stay patient. The process may not be as rapid as you'd like, and you can expect bumps along the way. But by remaining patient and focusing on small improvements, you create an atmosphere of safety for your child.

Foster a sense of humor. Joy and laughter go a long way toward repairing attachment problems and energizing you even in the midst of hard work. Find at least a couple of people or activities that help you laugh and feel good.

Joy and laughter go a long way toward repairing attachment problems and energizing you even in the midst of hard work. Find at least a couple of people or activities that help you laugh and feel good.

Take care of yourself. Reduce other demands on your time, make time for yourself, and manage stress. Rest, good nutrition, and parenting breaks help you relax and recharge your batteries so you can give your attention to your child.

[Read: Relaxation Techniques for Stress Relief]

Find support. Rely on friends, family, community resources, and respite care (if available). Try to ask for help before you really need it to avoid getting stressed to breaking point. You may also want to consider joining a support group for parents.

Stay positive and hopeful. Be sensitive to the fact that children pick up on feelings. If they sense that you're discouraged, it will be discouraging to them. When you are feeling down, turn to others for reassurance.

Parents of adopted or foster care children with an attachment disorder

When you adopted a child, you may not have been aware of an attachment disorder. Anger, disinterest, or unresponsiveness from your new child can be heartbreaking and difficult to understand.

Try to remember that your adopted child isn't acting out because of lack of love for you. Their experience hasn't prepared them to bond with you, and they can't yet recognize you as a source of love and comfort. Your efforts to love them will have an impact—it just may take some time.

Making a child with an attachment disorder feel secure

Safety and stability are core issues for children with attachment problems. They are distant and detached because they feel unsafe in the world. They keep their guard up to protect themselves, but it also prevents them from accepting love and support. So, before anything else, it is essential to build up your child's sense of security. You can accomplish this by establishing clear expectations and rules of behavior, and by responding consistently so your child knows what to expect when they act a certain way and—even more importantly—knows that no matter what happens, you can be counted on.

Set limits and boundaries. Consistent, loving boundaries make the world seem more stable and predictable and less scary to children with attachment issues. It's important that they understand what behavior is expected of them, what is and isn't acceptable, and the consequences if they disregard the rules. This also teaches them that they have more control over what happens to them than they think.

Take charge but remain calm when your child is upset or misbehaving. Remember that “bad” behavior means that your child doesn't know how to handle what they're feeling and needs your help. By staying calm, you show your child that the feeling is manageable. If they are being purposefully defiant, follow through with the pre-established consequences in a cool, matter-of-fact manner. But never discipline a child with an attachment disorder when you're in an emotionally-charged state. This makes the child feel more unsafe and may even reinforce the bad behavior, since it's clear that it pushes your buttons.

Be immediately available to reconnect following a conflict. Conflict can be especially disturbing for children with attachment disorders. After a conflict or tantrum where you've had to discipline your child, be ready to reconnect as soon as they're ready. This reinforces your consistency and love, and will help your child develop a trust that you'll be there through thick and thin.

[Read: Conflict Resolution Skills]

Own up to mistakes and initiate repair. When you let frustration or anger get the best of you or you do something you realize is insensitive, quickly address the mistake. Your willingness to take responsibility and make amends can strengthen the attachment bond. Children with attachment issues need to learn that although you may not be perfect, they will be loved, no matter what.

Try to maintain predictable routines and schedules. A child with an attachment disorder won't instinctively rely on loved ones, and may feel threatened by transition and inconsistency—when traveling or during school vacations, for example. A familiar routine or schedule can provide comfort during times of change.

A familiar routine or schedule can provide comfort during times of change.

Repairing attachment disorders by helping your child feel loved

A child who has not bonded early in life will have a hard time accepting love, especially physical expressions of love. But you can help them learn to accept your love with time, consistency, and repetition. Trust and security come from seeing loving actions, hearing reassuring words, and feeling comforted over and over again.

Identify actions that feel good to your child. If possible, show your child love through rocking, cuddling, and holding—attachment experiences they missed out on earlier. But always be respectful of what feels comfortable and good to your child. In cases of previous abuse, neglect, and trauma, you may have to go very slowly because your child may be very resistant to physical touch.

Respond to your child's emotional age. Children with attachment disorders often act like younger children, both socially and emotionally. You may need to treat them as though they were much younger, using more non-verbal methods of soothing and comforting.

You may need to treat them as though they were much younger, using more non-verbal methods of soothing and comforting.

Help your child identify emotions and express their needs. Children with attachment problems may not know what they're feeling or how to ask for what they need. Reinforce the idea that all feelings are okay and show them healthy ways to express their emotions.

Listen, talk, and play with your child. Carve out times when you're able to give your child your full, focused attention in ways that feel comfortable to them. It may seem hard to drop everything, eliminate distractions, and just live in the moment, but spending quality time together provides a great opportunity for your child to open up to you and feel your focused attention and care.

Supporting the health of a child with attachment issues

Your child's eating, sleep, and exercise habits are always important, but they're even more so for kids with attachment problems. Healthy lifestyle habits can go a long way towards reducing your child's stress levels and leveling out mood swings. When children with attachment issues are relaxed, well-rested, and feeling good, it will be much easier for them to handle life's challenges.

Healthy lifestyle habits can go a long way towards reducing your child's stress levels and leveling out mood swings. When children with attachment issues are relaxed, well-rested, and feeling good, it will be much easier for them to handle life's challenges.

Diet. Make sure your child eats a healthy diet full of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and lean protein. Be sure to skip the sugar and add plenty of good fats—like fish, flax seed, avocados, and olive oil—for optimal brain health.

[Read: Healthy Food for Kids]

Sleep. If your child is tired during the day, it will be that much harder for them to focus on learning new things. Make their sleep schedule (bedtime and wake time) consistent.

Exercise. Any type of physical activity provides a great antidote to stress, frustration, and pent-up emotion, triggering endorphins to make your child feel good. Physical activity is especially important for an angry child. If your child isn't naturally active, try some different classes or sports to find something that is appealing.

Any one of these things—food, rest, and exercise—can make the difference between a good and a bad day for a child who has an attachment disorder. These basics will help ensure that your child's brain is healthy and ready to connect.

Professional treatment

If your child is suffering from a severe attachment issue, such as either type of attachment disorder, seek professional help. Extra support can make a dramatic and positive change in your child’s life, and the earlier you seek help, the better. Start by consulting with your pediatrician, a child development specialist, or an organization that specializes in child development or attachment disorders.

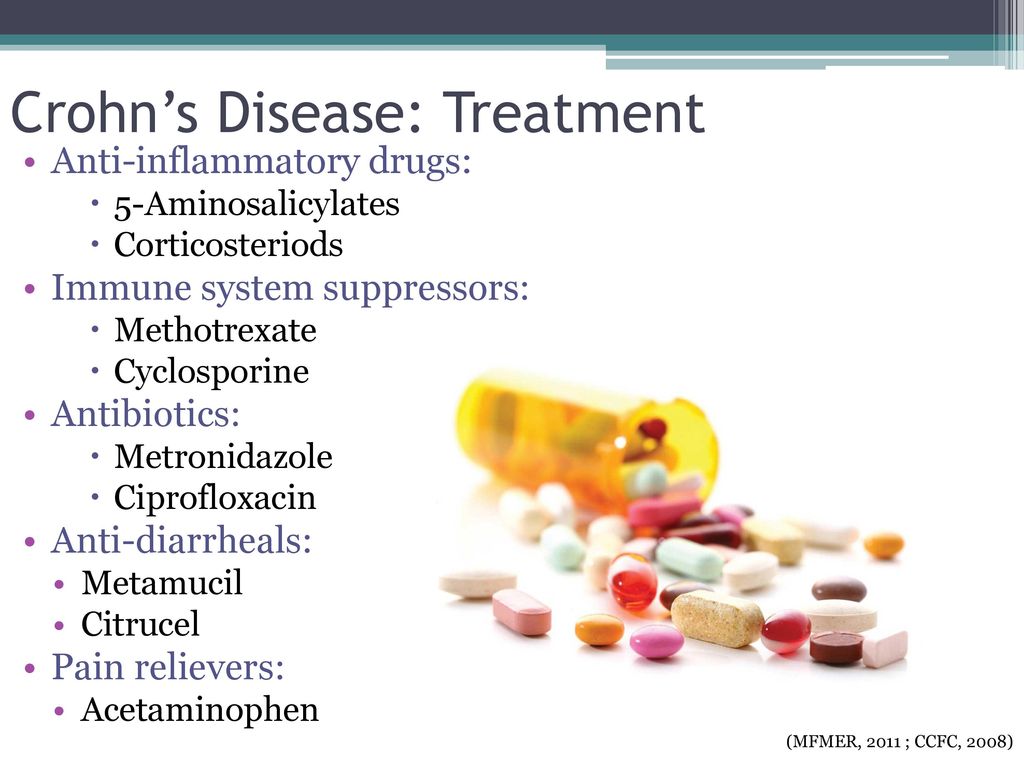

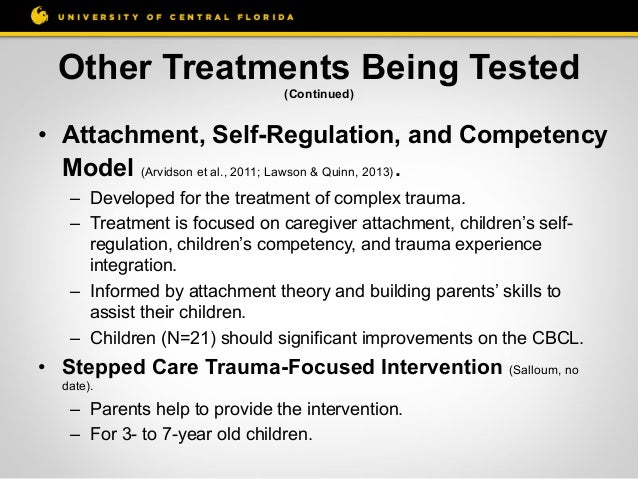

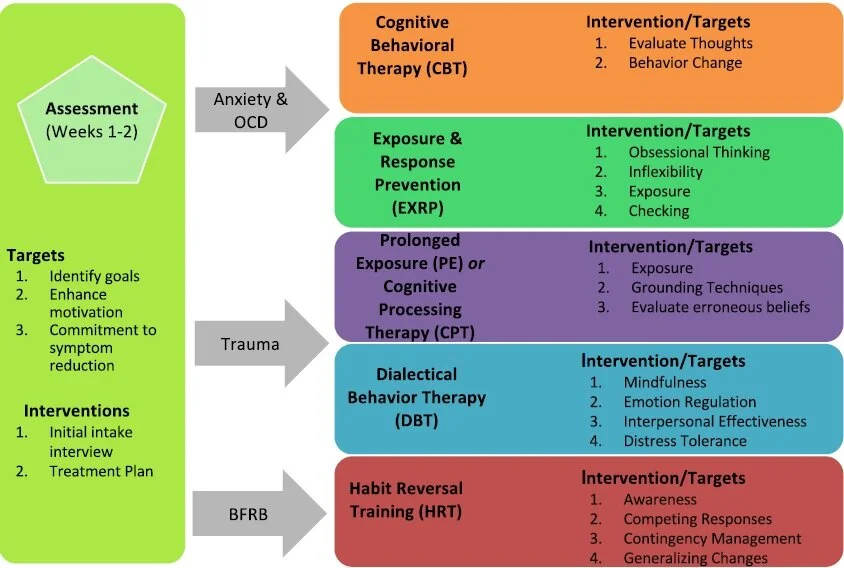

Treatment for attachment disorders usually involves a combination of therapy, counseling, and parenting education. These are designed to ensure that your child has a safe living environment, improves their peer relationships, and develops positive interactions with you, their parent or caregiver. While medication may be used to treat associated conditions, such as depression, anxiety, or hyperactivity, there is no quick fix.

Your pediatrician may recommend a treatment plan that includes:

Family therapy. Typical therapy for attachment problems includes both your child and you. Therapy often involves fun and rewarding activities that enhance the attachment bond as well as help parents and other children in the family understand the symptoms of the disorder and effective interventions.

Individual psychological counseling. Therapists may also meet with your child individually or while you observe. This is designed to help your child directly with monitoring their emotions and behavior.

Play therapy. Helps your child learn appropriate skills for interacting with peers and handling other social situations.

Special education services. Specifically designed programs within your child's school can help them learn skills required for academic and social success, while also addressing behavioral and emotional difficulties.

Parenting skills classes. Education for parents and caregivers centers on learning about attachment disorders as well as other necessary parenting skills.

Authors: Melinda Smith, M.A., Lawrence Robinson, Joanna Saisan, MSW, and Jeanne Segal, Ph.D.

- References

“CEBC » Search › Topic Areas › Dsm 5 Criteria For Reactive Attachment Disorder Rad.” Accessed August 12, 2021. https://www.cebc4cw.org/search/topic-areas/dsm-5-criteria-for-reactive-attachment-disorder-rad/

“CEBC » Search › Topic Areasdsm5 › Dsm 5 Criteria For Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder.” Accessed August 12, 2021. https://www.cebc4cw.org/search/topic-areasDSM5/dsm-5-criteria-for-disinhibited-social-engagement-disorder/

Zeanah, Charles H.

, Angela Keyes, and Lisa Settles. “Attachment Relationship Experiences and Childhood Psychopathology.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1008 (December 2003): 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1301.003

, Angela Keyes, and Lisa Settles. “Attachment Relationship Experiences and Childhood Psychopathology.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1008 (December 2003): 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1301.003Maria G, Kroupina, Rowena Ng, Claire M Dahl, Ann Nakitende, and Kathryn C Elison MSW. “Identifying Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (DSED) in a Clinical Sample of High Risk Children.” Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry 9, no. 3 (May 3, 2018). https://doi.org/10.15406/jpcpy.2018.09.00530

Humphreys, Kathryn L., Charles A. Nelson, Nathan A. Fox, and Charles H. Zeanah. “Signs of Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder at Age 12 Years: Effects of Institutional Care History and High-Quality Foster Care.” Development and Psychopathology 29, no. 2 (May 2017): 675–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417000256

Zouwen, Marion van der, Machteld Hoeve, Anne M.

Hendriks, Jessica J. Asscher, and Geert Jan J. M. Stams. “The Association between Attachment and Psychopathic Traits.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 43 (November 1, 2018): 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.09.002

Hendriks, Jessica J. Asscher, and Geert Jan J. M. Stams. “The Association between Attachment and Psychopathic Traits.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 43 (November 1, 2018): 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.09.002

Last updated: December 5, 2022

Attachment Disorder: 8 Tips for Parents and Carers

Photo from army.mil

It is human nature to seek another person, establish close relationships, become attached to someone who shows warmth and care. It is in the nature of a child to become attached to parents, grandparents, brothers and sisters, or to those who in their lives replace blood relatives.

Man is a social being, and therefore, even in conditions when parents neglect their duties, not satisfying the basic needs of the baby for food, comfort, affection, in the overwhelming majority of cases, he still loves a cruel mother or a father who drinks heavily and does not want to be separated with them.

But it happens in a different way. The difficult conditions in which the early development of the child proceeds can lead to a disease that is difficult to treat.

The difficult conditions in which the early development of the child proceeds can lead to a disease that is difficult to treat.

Most often, this problem is faced by adoptive parents whose child has experienced trouble in the birth family, and then ended up in an orphanage. The situation is even more difficult when the child has already been adopted by the family and then returned back to the children's institution.

However, there are cases of RRS in families with many children, where no one helps the mother and some of the children receive very little attention and care. The disorder can develop if the child was separated early from the parents for a long time as a result of a long hospital stay, or if the child spent most of the time with a mother suffering from depression or other serious illness that prevented her from properly caring for the child.

What is reactive attachment disorder?

Photo courtesy of phillypsychology.com

This is a condition in which a child does not form an emotional attachment to parents or persons acting in their stead. Symptoms of the disorder appear before the age of 5 years, often as early as infancy. This is lethargy, refusal to communicate, self-isolation. A small child is indifferent to toys and games, does not ask to be held, does not seek solace in physical pain. He rarely smiles, avoids eye contact, and appears sad and apathetic.

As they grow older, signs of self-isolation can manifest themselves in two seemingly opposite types of behavior: disinhibited and inhibited.

With disinhibited behavior, the child seeks to attract the attention of even strangers, often seeks help, performs acts that are inappropriate for his age (for example, comes to bed with his parents).

Misunderstanding, lack of patience, severe negative reaction to the child's behavior on the part of a significant adult can cause irritation, anger or an outburst of aggression on the part of the child, and if the violation persists in adolescence, alcohol abuse, drug addiction and other types of antisocial behavior.

With inhibited behavior, the child avoids communication and refuses help. In some cases, both types of behavior, both disinhibited and inhibited, are alternately observed in him.

Reactive attachment disorder can manifest in forms that sometimes cause despair in adoptive parents: the child constantly lies, steals, behaves impulsively, shows cruelty to animals and a complete lack of consciousness. He does not express regret or remorse after unacceptable behavior.

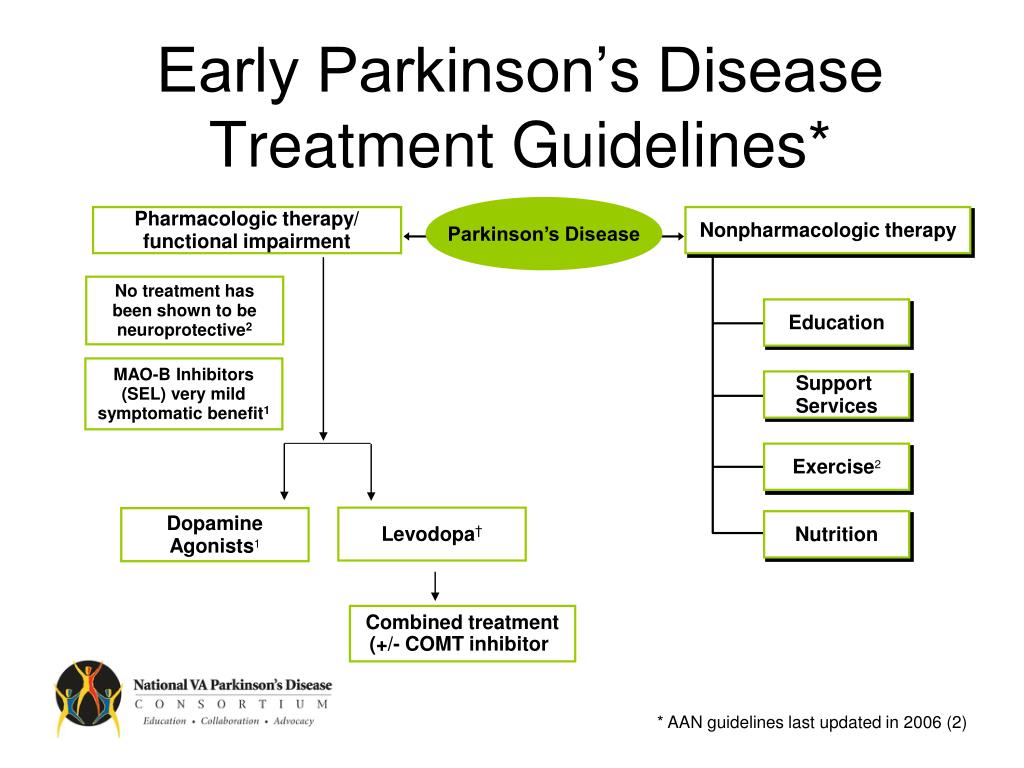

Diagnosing RRP is not an easy task. Some features of this disorder can be seen in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety disorder, autism, and post-traumatic stress disorder. In order to make an accurate diagnosis, it is necessary to observe the child's behavior in various situations over a certain period of time, analyze his biographical data, and evaluate the interaction of parents with the child.

In order to make an accurate diagnosis, it is necessary to observe the child's behavior in various situations over a certain period of time, analyze his biographical data, and evaluate the interaction of parents with the child.

Even harder to treat him

Photo from helpguide.org

Psychiatrists sometimes prescribe drugs to children with RAD, but in some cases they can only slightly improve the background against which the therapeutic interaction with the child will take place.

A child's parents or guardians play a key role in treatment. It is they who, with the help of doctors and psychologists, will have to create such an environment in which he can experience a healthy addiction, believe that an adult can be relied upon, and begin to trust him.

Experts believe that the therapeutic environment has 3 essential components: safety, stability and sensitivity.

In order to overcome the consequences of those events that caused the child's inability to form close and warm relationships, an adult must have enough time and patience to listen and hear the child with an open mind and without trying to judge him.

The child needs boundaries, but they must be set in a context of understanding and empathy. Only if the child feels emotional safety , that is, he understands that his story about himself will not cause a negative assessment from an adult, he will be filled with confidence and tell his foster mother or psychologist about the difficult experiences of his early childhood.

The second component after security is stability . The figure of an adult for the formation of a primary attachment must remain the same. It takes a long time to establish trust between a significant adult and a child with RAD. Changing such a figure, moving from one foster family to another, not only slows down the process, but also aggravates the disorder.

Having gone through the painful experience of ignoring his needs, the child must re-learn to be aware of them, as well as the fact that the same person can satisfy them over and over again: feed, give clean clothes, put in a warm bed, play, listen and comfort, help with the performance of tasks. Such children are often afraid that the new mother will abandon them or die, and only after a long period of stability do these fears subside.

Such children are often afraid that the new mother will abandon them or die, and only after a long period of stability do these fears subside.

Some children need at least a year of stability to begin to trust their significant adult, others become imbued with trust in foster parents after a few months. It depends on the temperament of the child (it is important, for example, whether he is an extrovert or an introvert), as well as how well the child and his new parent fit together in various ways.

Photo from wisegeekhealth.com

Long separations between a foster child and mother are undesirable: they can activate his defensive reaction, which is self-isolation.

And finally sensitivity . This is the emotional availability of an adult, his attentiveness to the needs of the child. Adoptive parents should be informed by specialists that while the mental development of a child with RAD may be age appropriate, his emotions often remain immature, which means that during the process of attachment formation, the need for an adult may be greater than that of a healthy child of the same age.

During this transitional period, parents must be very patient, be prepared for unexpected behaviors that are signals that the child is going through some earlier stages of development and attachment.

For example, a child who behaved suspiciously and aloofly suddenly begins to obsessively follow his mother, constantly report his fears, climb on his knees or come to sleep in his parent's bed - in a word, behave as if he suddenly stood on 2-3 years younger. In this case, parents should accept the situation and meet the child's need for greater dependence on them.

It is important for adoptive parents to understand the logic of changes happening to the child. Some adopted children initially seem emotionally cold, as experience has taught them that it is not safe for them to express their feelings and communicate their desires. At the same time, the child gives the impression of being completely obedient, because he does not show any irritation or discontent, does not talk about his needs.

Feeling safe, he intuitively feels that adults accept him and will not refuse him, which means that it is quite safe to declare your desires in any form, up to whims and tantrums.

If earlier the child remained indifferent to whether the mother was at home or she had gone somewhere, now he may burst into tears, cling to her and not let her go if she was about to leave without him. This is not easy for parents, but such behavior should be seen as a positive sign: attachment is gradually formed, the child overcomes the destructive consequences of his difficult early childhood.

In the case of RAD, the task of the psychologist is primarily to educate the parents and support them in creating a safe and stable environment for the child at home, but activities with the child can also be useful. Play therapy and other techniques can help the child to realize their own needs, to build trusting relationships with a new significant adult.

Photo courtesy of drpokea. com

com

At the same time, parents should be wary of offerings to work with their child using methods that are collectively called Attachment Therapy.

Not only does this therapy lack scientific evidence and documented efficacy, it is also not safe.

Attachment therapy combines a number of violent methods, the most famous of which are holding therapy (holding) and rebirthing (“rebirth”).

In "rebirth", the baby's body is wrapped in a blanket and forced to crawl through compressed pillows, simulating passage through the birth canal. It is assumed that "having been born again", he overcomes past negative experiences and is ready for intimacy with his mother. In 2000, a 10-year-old girl suffocated during such a procedure in Colorado (USA), and this therapy has since been banned in the state.

Until now, there are quite a few adherents of holding therapy for the treatment of autism and RRP, among them the well-known psychologists in our country, Dr. OS Nikolskaya and M. M. Liebling.

M. Liebling.

The essence of therapy is that the mother forcibly holds the child in her arms and, despite his resistance, tells him how much she needs him and how much she loves him. It is assumed that after a period of resistance, when the child tries to escape, scratches and bites, relaxation occurs, during which contact is established between mother and child.

Critics of the method argue that it is not ethical, as it is based on physical coercion, and can provoke a regression in the development of the child. Indeed, how can trust be established on the part of a child in an adult who uses physical violence against him?

Raising a child with a reactive disorder is associated with enormous emotional costs, sometimes with stress for parents who blame themselves if they do not see positive changes in the child's condition and behavior for a long time.

If your child is diagnosed with RDD

Photo from helpyourteennow.com

- Remember that there are no miracle cures to achieve a breakthrough in a child's condition in a short time.

There is no substitute for a therapeutic home environment, security, stability, and your willingness to respond emotionally to your child's needs.

There is no substitute for a therapeutic home environment, security, stability, and your willingness to respond emotionally to your child's needs. - Be sure to find an opportunity and a way to restore your own emotional balance. A child with RAD is already stressed, and your anxiety or irritability can make it worse. To feel safe, the child must feel your calmness and firmness.

- Set boundaries for what is allowed. The child must understand what behavior is unacceptable and what consequences await him in case of violation of the rules. It is important to explain to the child that your rejection does not apply to him, but to certain of his actions.

- After a conflict, be ready to quickly reconnect with your child to let him feel that the reason for your dissatisfaction was a particular behavior, but you love him and cherish the relationship with him.

- If you were wrong about something, don't be afraid to admit your mistake. This will strengthen your bond with your child.

- Set a daily routine for your child and monitor his performance. This will reduce the level of anxiety in the child.

- If possible, show your love for your child through bodily contact: rocking, hugging and holding. However, keep in mind that if a child has been abused or traumatized, he will initially resist being touched, so you will need to work slowly.

- Set aside time that you will completely devote to the child, you will play, talk, walk with him, without being distracted by other activities or other people. This is a very important part of your relationship.

You have a difficult task ahead of you, but it can be done. Do not rush things, be patient and do not lose hope.

Sources:

Reactive attachment disorder in childhood

Psychological and Behavioral Interventions

Attachment Issues and Reactive Attachment Disorder

Rebirthing therapy banned after girl died in 70 minute struggle

The Dangers of Holding Therapy

Reactive attachment disorder

interview with David Elliott - Eros and Space Integral Dialogue” is a joint initiative of the “Integral Space” project and the online magazine “Eros and Cosmos”.

1 This interview was recorded in St. Petersburg in January 2020; published for the first time. The transcript of the interview has been edited for better readability.

1 This interview was recorded in St. Petersburg in January 2020; published for the first time. The transcript of the interview has been edited for better readability. Video with Russian subtitles. If subtitles are not displayed,

you can turn them on manually.

Evgeny Pustoshkin: Welcome, David, to St. Petersburg. Thank you for agreeing to this interview.

David Elliott: No way! Glad to be here.

E.P.: So, let's go straight to our questions. The first question is this. You co-authored (or co-edited) with Daniel Brown the book Adult Attachment Disorders ( Attachment Disturbances in Adults ). What it is? What are "attachment disorders" and what are the methods of their treatment in terms of the method you have developed?

What it is? What are "attachment disorders" and what are the methods of their treatment in terms of the method you have developed?

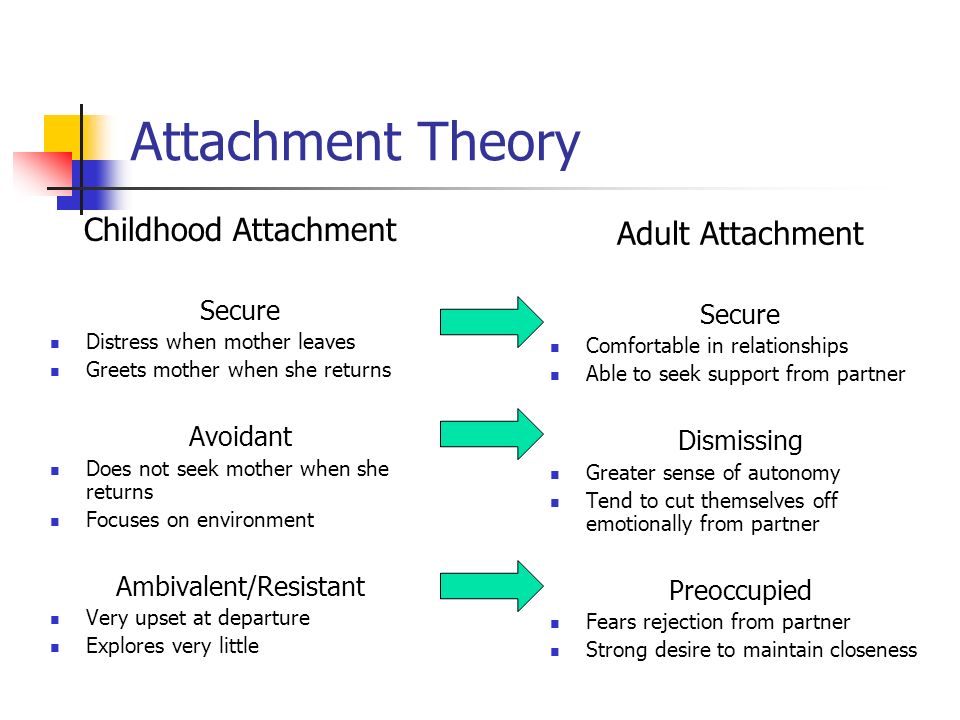

AE: Well... This book has 752 pages answering these questions, so I'll try to be concise. Attachment is a term that has a psychological meaning and describes the experience of an infant in connection with his caregiver [hereinafter referred to as the parent]. Ideally, this relationship, what is called "bonds of affection," is something psychologically described as "safe." In an ideal situation, a young child, by about the age of 2 years, has the experience of feeling secure in the relationship with the parent - secure attachment - and this means that at the level of internal experience the infant has a feeling of trust and confidence that his needs will be reasonably met - but here we are not talking about some perfection in the satisfaction of needs, but about their "good enough" satisfaction. Whenever a need arises - such as hunger, "cold", "hot", fear - the parent will be reasonably present, attentive and responsive, to try to calm and comfort the infant, restore him to a sense of relative comfort.

Ideally, this happens - as I mentioned - in a "good enough" way. We rely heavily on Winnicott's concept of "good enough parenting." This means that approximately 70% of the time the caregiver or parent will be able to respond appropriately to and meet the needs of the infant. In such circumstances, the child develops a sense of trust not only in the parent, but also in the world as such.

Daniel Brown, David Elliott. "Adult Attachment Disorders": Brown D.P., Elliott D.S. Attachment Disturbances in Adults: Treatment for Comprehensive Repair. — New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2016. 752 p. (Photo © Tatyana Parfenova) This is a secure attachment relationship that is established by about 2 years of age and serves as a foundation for the child, adolescent and eventually adult to experience a sense of security and confidence in the world: that whenever stressful circumstances, whenever needs arise, resources will always be available from outside, and then, ultimately, from within, in order to be able to respond to the need and satisfy it.

These are the circumstances of secure attachment. In most Western countries—actually, I'm talking about the United States here, because I'm most familiar with the data for this country—statistics say that approximately 60% of adults have what is called "secure attachment", and 40% have "insecure attachment". So insecure attachment is a completely different circumstance. These are circumstances in which, by about age 2, the infant and toddler lacks the feeling that his (or her) needs will be adequately met. When this happens, there is a lack of trust, a lack of experience that the parent will be sufficiently present to meet those needs. The infant and toddler must develop ways of interacting with the parent in order to try to maximize the possibility that their needs will be met. So there are several types of insecure attachment; each type describes a different attempt to adapt to the lack of a "good enough" presence of the parent.

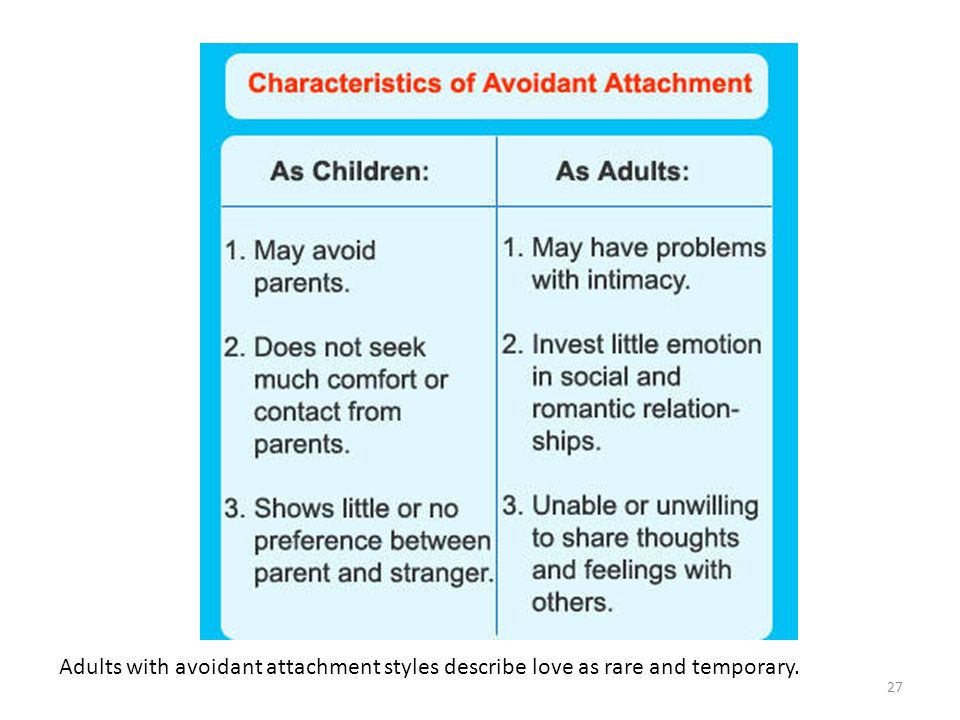

So, one of the forms of insecure attachment is called “rejecting” or “avoidant”. This happens when the child experiences his parent as someone who rejects—actually actively rejects—the child's need to connect with him. So the child learns that whenever he has a need for something and if he turns to his parent in search of comfort, support, in order to somehow satisfy this need, most often the parent will simply not be present, to meet those needs, but will actively reject and turn away from—perhaps even ridicule—the child for having that need. In this sense, the child learns not to turn to the parent for needs; the child learns to try to take care of his own need and acquires traits that are often called "avoidant". He avoids establishing closer bonds, avoids close contact with the parent, tries to be self-sufficient, tries to take care of his needs in his own way.

This happens when the child experiences his parent as someone who rejects—actually actively rejects—the child's need to connect with him. So the child learns that whenever he has a need for something and if he turns to his parent in search of comfort, support, in order to somehow satisfy this need, most often the parent will simply not be present, to meet those needs, but will actively reject and turn away from—perhaps even ridicule—the child for having that need. In this sense, the child learns not to turn to the parent for needs; the child learns to try to take care of his own need and acquires traits that are often called "avoidant". He avoids establishing closer bonds, avoids close contact with the parent, tries to be self-sufficient, tries to take care of his needs in his own way.

Another form of insecure attachment is called preoccupied attachment. These are circumstances that occur as a result of an infant (or child, or toddler) turning to a parent to pay attention to his needs and satisfy them, and the parent is sometimes present, sometimes not responding - that is, was inconsistent in his response. Sometimes the parent himself is anxious or preoccupied, so that he is not able to truly tune in to the needs of the child. In this case, the child becomes anxious about the parent and doubts whether his needs will be met. One way he may try to adapt to this is by increasing the expression of need - the child becomes more and more frustrated, more and more anxious, hoping that an increase in the intensity of the expression of need will make the parent more likely to become available to him. Then the parent may be able, even for a moment, to forget about what he himself is so much concerned about, about his own anxieties or difficulties, and attune with the baby. So, in a sense, the stress felt by the child becomes something that is very important to express in a more intense way in order to get those needs met by the parent. These patterns [reaction stereotypes], again, are usually established by the age of 2 years and, as you can imagine, will persist as development continues. They will show up in adult relationships too.

Sometimes the parent himself is anxious or preoccupied, so that he is not able to truly tune in to the needs of the child. In this case, the child becomes anxious about the parent and doubts whether his needs will be met. One way he may try to adapt to this is by increasing the expression of need - the child becomes more and more frustrated, more and more anxious, hoping that an increase in the intensity of the expression of need will make the parent more likely to become available to him. Then the parent may be able, even for a moment, to forget about what he himself is so much concerned about, about his own anxieties or difficulties, and attune with the baby. So, in a sense, the stress felt by the child becomes something that is very important to express in a more intense way in order to get those needs met by the parent. These patterns [reaction stereotypes], again, are usually established by the age of 2 years and, as you can imagine, will persist as development continues. They will show up in adult relationships too. These are the two basic patterns of insecure attachment.

These are the two basic patterns of insecure attachment.

There is another type of attachment that is more of a combination of the two. It is often referred to as "disorganized attachment". This, again, is another way of trying to adapt to circumstances where the parent is experienced as someone who does not automatically lead to needs being met.

EP: And the point is not that it should be some kind of direct psychotrauma, as, for example, when they yell and show absolute neglect of the child. It's more about the relationship and attunement of the parent with the child, right?

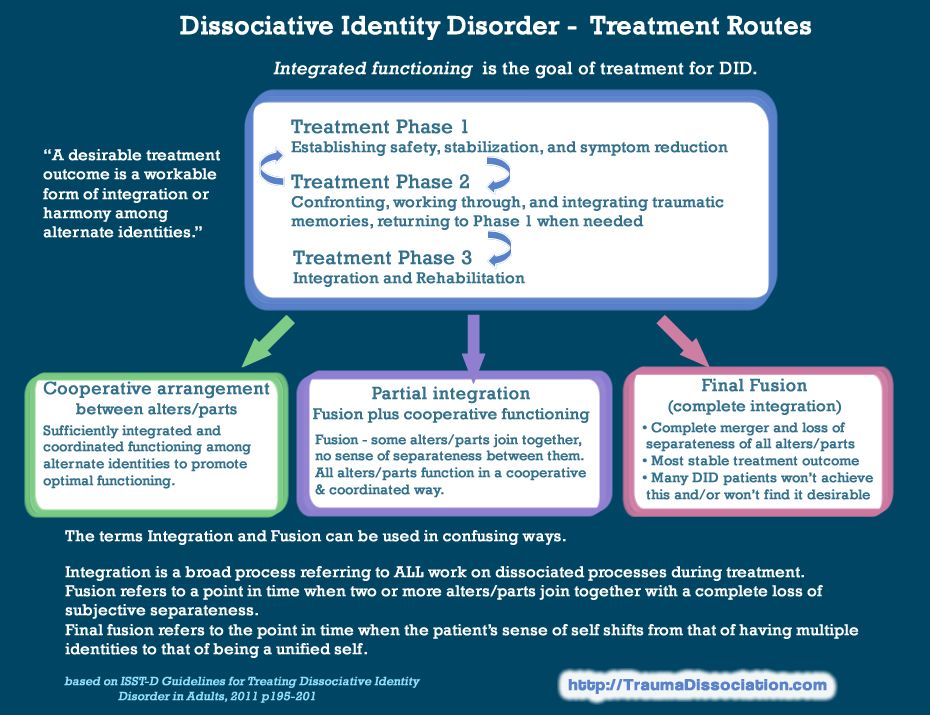

DE: Exactly. Although I would add that if there were a lot of traumatic factors and violence (abuse), such as when they yell, as you mentioned, then the degree of attachment violation, the degree of attachment insecurity will be much higher and, most likely, will manifest itself in the form of a disorganized attachments. Disorganized attachment usually causes the most problems for a young child, and also when he becomes an adult and lives with this type of attachment in adulthood. Here we are dealing with some of the most severe psychological disorders, such as "dissociative identity disorder", which was previously called "multiple personality disorder", and "borderline personality disorder", which, as a rule, gives a person great difficulties: in his internal and there is a lot of chaos in the outer life. This disorder is also difficult to heal psychologically. Disorganized attachment is almost always found at the base of both disorders.

Here we are dealing with some of the most severe psychological disorders, such as "dissociative identity disorder", which was previously called "multiple personality disorder", and "borderline personality disorder", which, as a rule, gives a person great difficulties: in his internal and there is a lot of chaos in the outer life. This disorder is also difficult to heal psychologically. Disorganized attachment is almost always found at the base of both disorders.

So, you see, what we really want is… So part of our interest and our job is to help psychologists and mental health professionals learn how to deal with insecure attachment, and also to help parents become… well, you can. say: address some of their own insecure attachment issues so they can be more accessible to their children and can raise children who don't have insecure attachments and are more likely to develop secure attachments. Research has also revealed something related to this: if a child has an insecure attachment, then there is a higher chance that he may develop a whole range of psychological problems. Such children are less flexible and resilient when faced with the stresses that occur in life and can lead to psychological difficulties. If a child has a secure attachment, then he is much more resilient and flexible when faced with the stressful and difficult situations that are inevitable in life. So they are less likely to have psychological problems as they get older.

Such children are less flexible and resilient when faced with the stresses that occur in life and can lead to psychological difficulties. If a child has a secure attachment, then he is much more resilient and flexible when faced with the stressful and difficult situations that are inevitable in life. So they are less likely to have psychological problems as they get older.

If a child has a secure attachment, then he is much more resilient and flexible when faced with stressful and difficult situations that are inevitable in life , then he, they say, is more adaptable to society. It seems that the science of attachment shows us that if you have an underlying disorder of this type of attachment, then it will be an important predictor that you will have problems in the future in adulthood, right?

DE: Yes, yes, that's right. This gives us additional motivation to try to educate people about the findings of attachment science and developmental science, both mental health professionals and the general population, so that parents have access to resources to help themselves if they have challenges to raising children with secure attachments, and to help them learn the basics… some of the foundational ways of parenting that promotes secure attachments. And that's one of the highlights of the book we published in 2016. We have described a very specific number of conditions conducive to the development of secure attachment in children.

And that's one of the highlights of the book we published in 2016. We have described a very specific number of conditions conducive to the development of secure attachment in children.

E.P.: As far as I understand, this is the result of long-term research. Is this true?

DE: Yes. What we did as part of this work was to research very carefully and consider what many professionals over the past 50 years of studying attachment issues have found about what typically leads to the development of secure attachment during parenthood, and which tends to lead to the development of insecure attachments and insecure parenting styles. Mary Ainsworth, who was a colleague of John Bowlby - we consider them the "mom" and "dad" of the field of attachment research - in general, Mary Ainsworth was one of the first people to clearly describe the conditions conducive to the development of secure attachment. And she used the term "maternal responsiveness" to refer to a fundamental aspect of parenting style that promotes secure attachment. What she meant by this when she used the word "maternal responsiveness" was that the mother - but it could also be the father or any other caregiver - is reasonably available to respond effectively to the needs of the child in any a single point in time. We are not talking about one hundred percent responsiveness and accuracy of the reaction. This is impossible for a human. But we keep coming back to Winnicott's concept of being "good enough parents" - about 70% of the time, a mother or caregiver can be responsive in certain ways.

What she meant by this when she used the word "maternal responsiveness" was that the mother - but it could also be the father or any other caregiver - is reasonably available to respond effectively to the needs of the child in any a single point in time. We are not talking about one hundred percent responsiveness and accuracy of the reaction. This is impossible for a human. But we keep coming back to Winnicott's concept of being "good enough parents" - about 70% of the time, a mother or caregiver can be responsive in certain ways.

So we have looked at Ainsworth's description of maternal responsiveness. We also studied the work of other researchers and clinicians. And we have tried to make a distillate of everything that is, in order to get quite specific descriptions of what, in our opinion, is the quintessence of the most necessary. And we've called these the "Five Conditions for Developing Secure Attachment." Do you want me to...?

EP: Of course, what are these five conditions?

DE: Okay, five conditions. Again, these are descriptions of what we consider [basic conditions] that we have identified from the work done by many other people. We do not claim that we did all this exclusively ourselves. However, we believe that these descriptions are very useful if you think about them as we suggest. So the first condition is the child's experience of security in relation to the parent; a child is more likely to feel secure in a relationship with a parent if the parent consistently demonstrates the ability to protect the child. The child, quite naturally, very often experiences fear and stress when feeling threatened. This is a fundamental aspect of appearing in our world. The world inevitably brings forth circumstances that are frightening. So, a child, when he feels fear, may somehow be frightened; it would be nice if, in an ideal situation, the parent would recognize that the child is feeling frightened and be able to protect him. For example, a baby may feel comfortable and contented...maybe he is playing with his mother and then all of a sudden someone comes into the room - a stranger - and this stranger is acting very loud, moving very fast, so the baby is most likely gets very scared.

Again, these are descriptions of what we consider [basic conditions] that we have identified from the work done by many other people. We do not claim that we did all this exclusively ourselves. However, we believe that these descriptions are very useful if you think about them as we suggest. So the first condition is the child's experience of security in relation to the parent; a child is more likely to feel secure in a relationship with a parent if the parent consistently demonstrates the ability to protect the child. The child, quite naturally, very often experiences fear and stress when feeling threatened. This is a fundamental aspect of appearing in our world. The world inevitably brings forth circumstances that are frightening. So, a child, when he feels fear, may somehow be frightened; it would be nice if, in an ideal situation, the parent would recognize that the child is feeling frightened and be able to protect him. For example, a baby may feel comfortable and contented...maybe he is playing with his mother and then all of a sudden someone comes into the room - a stranger - and this stranger is acting very loud, moving very fast, so the baby is most likely gets very scared. And if the mother is attuned to the child, then she (or he [if the guardian is male]) will recognize that the child is afraid, under stress, so maybe she will take the child in her arms, hug her and maybe take her to another room where it's quieter. And this terrible person will no longer bother the child. It is about a situation where the child experiences feelings of joy and security and something unexpected happens, so that the feeling of security disappears. There is a feeling of fear and stress, and then the child experiences that the mother immediately responds to the situation and takes effective action to protect the child from what frightened him. So, here you see a couple situation. There is a sense of security, and security is there because of certain behavior on the part of the parent. In general, this is the first condition: a feeling ... a felt sense of security and stable protection from the mother or parent.

And if the mother is attuned to the child, then she (or he [if the guardian is male]) will recognize that the child is afraid, under stress, so maybe she will take the child in her arms, hug her and maybe take her to another room where it's quieter. And this terrible person will no longer bother the child. It is about a situation where the child experiences feelings of joy and security and something unexpected happens, so that the feeling of security disappears. There is a feeling of fear and stress, and then the child experiences that the mother immediately responds to the situation and takes effective action to protect the child from what frightened him. So, here you see a couple situation. There is a sense of security, and security is there because of certain behavior on the part of the parent. In general, this is the first condition: a feeling ... a felt sense of security and stable protection from the mother or parent.

The second condition I mentioned in the description of the first condition is attunement - parental attunement. If the parent is stably attuned to the child, that is, in empathy, aware of the child's experiences and connected with them, then most likely the child will feel that he is seen and known. The child is very likely to develop the experience: “Oh, there is someone, this important person - my mother, my father - who knows, knows me; knows what I'm going through; knows when I'm afraid; knows when I'm happy; knows when I need something" - and again, we are talking about the fact that this happens in a "good enough" degree, not one hundred percent. Parental attunement leads to this feeling that your parent sees and knows you, and this is very important for developing a secure attachment.

If the parent is stably attuned to the child, that is, in empathy, aware of the child's experiences and connected with them, then most likely the child will feel that he is seen and known. The child is very likely to develop the experience: “Oh, there is someone, this important person - my mother, my father - who knows, knows me; knows what I'm going through; knows when I'm afraid; knows when I'm happy; knows when I need something" - and again, we are talking about the fact that this happens in a "good enough" degree, not one hundred percent. Parental attunement leads to this feeling that your parent sees and knows you, and this is very important for developing a secure attachment.

The third condition is that whenever the child is upset or stressed, the parent is reasonably available to him as a source of comfort and reassurance. So, it can be in the form of a defense against danger, as in the first example, and it can also be in the context of a situation where the child is very hungry and begins to feel stressed from hunger, then an attuned parent will recognize that the child is feeling hungry and not stressed, say, from something else, and then provide the child with food and nutrition . ..

..

EP: And we're talking about the first two years of life, right?

DE: Good question. Yes, it all happens, you see, right from the moment of birth, and the feeling of connection, or bonds, attachment, whether secure or insecure, is usually established by 18 months - that is, by the age of 18 months - 2 years. In general, these first years are very, very important.

So the third condition is the feeling of stable comfort from the parent, available to provide comfort and reassurance when the child is stressed.

The fourth condition is the feeling that the parent appreciates you, then the child develops a stable feeling that he is appreciated if the parent is consistent in that he rejoices at the child, is happy to be with the child, feels joy when he is connected with the child and is able to communicate this to him through a joyful facial expression, joyful sounds, and also direct verbal expression as the child understands verbal speech more and more. And this leads to the development of a feeling that you are important. “Oh, this important person to me really enjoys me,” and this is internalized [learned] in a very good way.

And this leads to the development of a feeling that you are important. “Oh, this important person to me really enjoys me,” and this is internalized [learned] in a very good way.

And the last of the five conditions that we're discussing is the feeling of being supported at your best, and that's the experience that develops when a parent consistently encourages a child to explore, learn, notice interesting things. If the parent shows interest in the child, then he can support the child so that the child can explore and discover for himself what is interesting to him [i.e. e. child]. And this contributes to the development of a sense of security in relation to the parent.

I would like to add one more component to this. You've probably noticed by now that these five conditions that support secure attachment also support some very important... some other important psychological and emotional qualities that unfold during development. One of them is the development of the "I" or self. A securely attached child is much more likely to develop a stronger, more balanced, and more stable sense of self, and this stems from all the same conditions—especially from the attunement of a parent who is able to recognize the needs of the child. When a parent consistently recognizes the inner states and needs of the child, over time this contributes to the development of emotional variability and self-recognition of their states.

A securely attached child is much more likely to develop a stronger, more balanced, and more stable sense of self, and this stems from all the same conditions—especially from the attunement of a parent who is able to recognize the needs of the child. When a parent consistently recognizes the inner states and needs of the child, over time this contributes to the development of emotional variability and self-recognition of their states.

A securely attached child is much more likely to develop a stronger, more balanced, and more stable sense of self.

Also the feeling of being appreciated by a parent who makes you happy as a child, maintains self-respect (self-esteem). Think about it: if a child consistently feels that the parent enjoys the very fact of his existence, this will increase self-esteem and support exploration and discovery in the world. Well, how do we develop a sense of our unique selves and what we like and dislike? It comes to us as a result of exploring the world around us, from feeling safe enough to move away from the parent and find for myself what I like and don’t like, and then return to the parent with the words: “Look what I found!" In a favorable situation, the parent will show interest and even joy in relation to the discovery made by the child. So, this contributes to the development of "I".

So, this contributes to the development of "I".

As we develop, in an ideal situation, we not only learn our emotions and the different types of emotions we can have, but also learn how to regulate our emotions. Individuals with borderline personality disorder or other psychological problems may be overwhelmed by emotions. They do not have a good internal ability to cope with or regulate internal emotional states. If during the first 2 years of the child's life the parent was consistently available to help the child regulate his internal states - to comfort the child when, for example, he is under stress - the child internalizes this experience, that the parent comforts him, develops in himself an internal representation - you could say an internal image - that he is comforted whenever he is stressed; and we found that if this happened to a good enough extent during childhood, then in adult life these internal representations, these internal images of being comforted whenever you are stressed, help develop the ability to self-comfort and self-regulate emotions during adulthood. life.

life.

Therefore, whenever a patient or client comes to us for psychotherapy who has a lot of emotional difficulties, overwhelming emotional experiences, and he has difficulty in regulating them, we think that he has some kind of early childhood problems with attachment, and we can work in a certain way, as we describe in the book, with an adult client to help him correct these problems so that skills of internal self-regulation can develop, even if they were not formed in childhood.

E.P.: Therefore, often an adult comes to the psychotherapist’s office with certain kinds of problems – emotional problems or scenarios – and often such people do not even think what a powerful influence the first 2 years of life had on them, because, of course, the first 2 years of life for them are subconscious or unconscious, right?

JE: You've got it right.

EP: Therefore, the essence of psychotherapeutic work, informed by knowledge about attachment, is to notice these patterns of attachment disorders and help adults correct them in their adult personality.

DE: Yes.

EP: So that they can improve their lives...

DE: Exactly. We found... You see, as I said, in the US, about 40% of adults have an insecure attachment. But among those people who come in for psychotherapy, a much higher percentage, we found, have an underlying insecure attachment—to a large extent, or at least some of it. Again, there can be a whole spectrum of severity of insecure attachment. But we… and here I must emphasize: I am talking about American statistics, however, in 2010 there was a study conducted by Natalia Pleshkova, a Russian researcher working here in St. Petersburg 2 . She took a sample of babies from St. Petersburg families - well-to-do families living in St. Petersburg. As far as I remember, there were about 130 babies there. And she found that only less than 7% were insecurely attached, which means that 93% of that sample has some form of insecure attachment here in St. babies from families that didn't seem to have any kind of violence, you know, there wasn't anything terrifying at all. But almost 93% of these children—they were in their second year of life—had an insecure attachment; and Pleshkova speculated why this was the case, why there was such a low level of secure attachment among these children.

babies from families that didn't seem to have any kind of violence, you know, there wasn't anything terrifying at all. But almost 93% of these children—they were in their second year of life—had an insecure attachment; and Pleshkova speculated why this was the case, why there was such a low level of secure attachment among these children.

It's very interesting, the ideas she was talking about: in Russian culture, in society, there is probably a lot of unresolved grief and psychological trauma due to events and incidents that have been happening for decades; and when a parent has an unresolved psychological trauma or unresolved grief, this will affect his care of the child, his parenthood. So that's another reason why it's so important to the well-being of children that parents can work through and, ideally, heal the type of inner insecurity that they carry with them - that type of unresolved grief or trauma that has arisen in their biography, in their biographies. parents, in the history of culture in general, and this is one of the aspects why I love this work so much, because it can have an effect not only individually on people who come to us for psychotherapy, but also the more we help someone individually, who can later become a parent, the more it will help, in turn, their children to develop a secure attachment.

I have been teaching this methodology in St. Petersburg for several years now. In one of my advanced seminars that the introductory seminar attendees attended, I asked about their experience with this psychotherapeutic method that we describe in our book, and one woman raised her hand and said, “and she works a lot with foster parents, especially with foster mothers, and she said that in her work she found that a great many foster mothers came to her for help in developing their parenting skills and working through their own difficult experiences that are activated in the process of being a foster parent. This woman saw that quite a few of these adoptive parents had an insecure attachment pattern, so she used the psychotherapeutic methods that I taught, and, according to her, several people who came to her - several of these adoptive mothers - after period of the sessions where this work on attachment healing was done, they said: “After our work with you, I feel more love for my children” - and I think that this . .. this is wonderful! It's... See, it can have that effect. If these parents love their children more, then the children will live better, they will be more likely to feel secure and able to grow up to reach their full potential.

.. this is wonderful! It's... See, it can have that effect. If these parents love their children more, then the children will live better, they will be more likely to feel secure and able to grow up to reach their full potential.

EP: The way Daniel Brown describes this method of psychocorrection… this method of correcting attachment disorders sounds like a modified version of… more precisely, a synthetic method that integrates something like meditation using visualization, is it? Can you at least briefly describe the essence of the technique?

DE: Absolutely. All in all, the method that Dan Brown and I developed - as part of a working group that met for over 8 years and studied attachment research and healing - includes what we call the three pillars of effective attachment therapy.

The first pillar includes the technique you are talking about - we call it the "Ideal Parent Figure Method". This includes the following: The technique is being used with adults, and we ask… first we help the adult client to align with body awareness. We want the person to not so much think about the process in some intellectual way. Ideally, we want a person to viscerally and fully bodily experience a certain series of images, which I will describe in a moment. We want a person to enter into a body-centered experience, because during the first 2 years of life, which are most significant for the experience of attachment and during which, in fact, the type of attachment is formed, the cognitive [intellectual] system is not very developed, but instead, the infant and young child experiences most things in the body—using body awareness.

We want the person to not so much think about the process in some intellectual way. Ideally, we want a person to viscerally and fully bodily experience a certain series of images, which I will describe in a moment. We want a person to enter into a body-centered experience, because during the first 2 years of life, which are most significant for the experience of attachment and during which, in fact, the type of attachment is formed, the cognitive [intellectual] system is not very developed, but instead, the infant and young child experiences most things in the body—using body awareness.