The causes of add

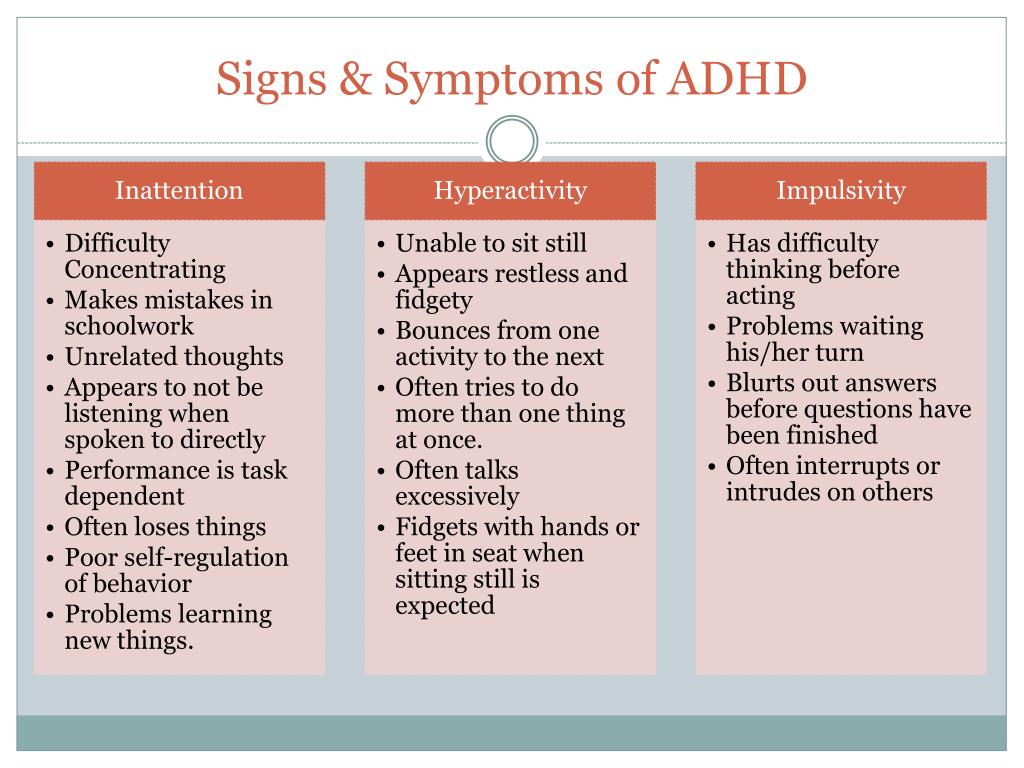

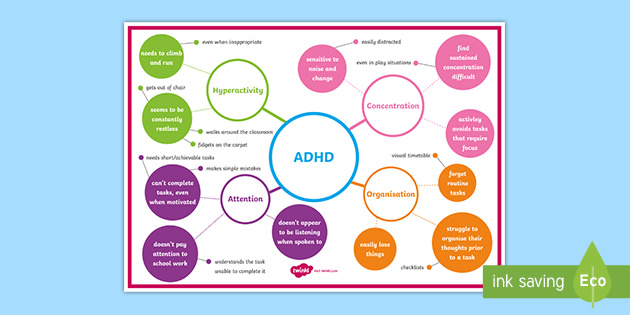

What causes attention deficit hyperactivity disorder?

1. Meltzer H. The mental health of children and adolescents in Great Britain. London: The Stationery Office; 2000 [Google Scholar]

2. Ford T, Goodman R, Meltzer H. The British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey 1999: the prevalence of DSM-IV disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:1203–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, et al. Young adult follow-up of hyperactive children: antisocial activities and drug use. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004;45:195–211 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, et al. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: adaptive functioning in major life activities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006;45:192–202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Thapar A, Langley K, Asherson P, et al. Gene–environment interplay in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and the importance of a developmental perspective. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:1–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Rutter M, Thapar A, Pickles A. Gene–environment interactions: biologically valid pathway or artifact? Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66:1287–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Biederman J. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a selective overview. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57:1215–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Thapar A, Holmes J, Poulton K, et al. Genetic basis of attention deficit and hyperactivity. Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:105–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Sprich S, Biederman J, Crawford MH, et al. Adoptive and biological families of children and adolescents with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000;39:1432–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

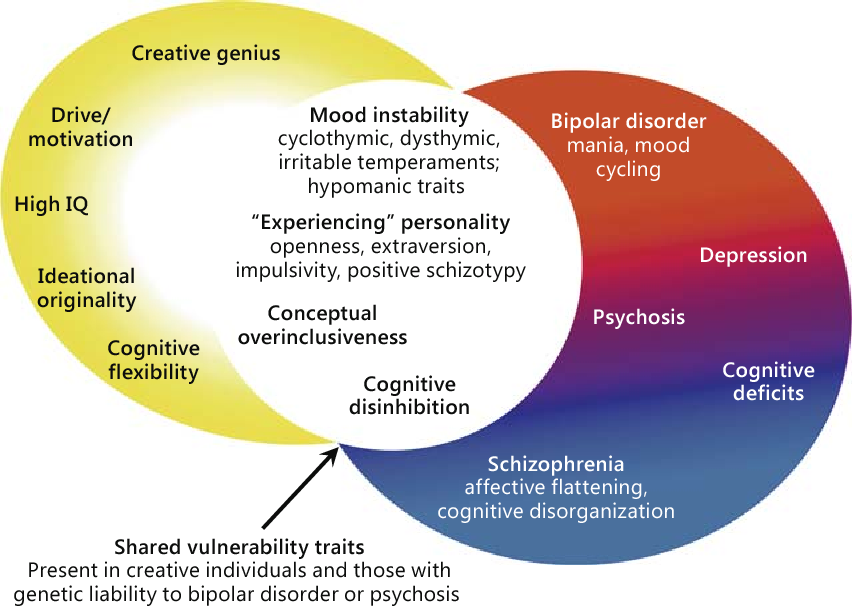

10. Lichtenstein P, Carlström E, Råstam M, et al. The genetics of autism spectrum disorders and related neuropsychiatric disorders in childhood. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:1357–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Paloyelis Y, Rijsdijk F, Wood AC, et al. The genetic association between ADHD symptoms and reading difficulties: the role of inattentiveness and IQ. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2010;38:1083–95 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Abnorm Child Psychol 2010;38:1083–95 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Kuntsi J, Eley TC, Taylor A, et al. Co-occurrence of ADHD and low IQ has genetic origins. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2004;124B:41–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Cole J, Ball HA, Martin NC, et al. Genetic overlap between measures of hyperactivity/inattention and mood in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;48:1094–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Thapar A, Harrington R, McGuffin P. Examining the comorbidity of ADHD-related behaviours and conduct problems using a twin study design. Br J Psychiatry 2001;179:224–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Thapar A, Stergiakouli E. Genetic influences on the development of childhood psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry 2008;7:277–81 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Faraone SV, Doyle AE, Mick E, et al. Meta-analysis of the association between the 7-repeat allele of the dopamine D(4) receptor gene and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1052–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1052–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, et al. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57:1313–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Li D, Sham PC, Owen MJ, et al. Meta-analysis shows significant association between dopamine system genes and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Hum Mol Genet 2006;15:2276–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Gizer IR, Ficks C, Waldman ID. Candidate gene studies of ADHD: a meta-analytic review. Hum Genet 2009;126:51–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. DiMaio S, Grizenko N, Joober R. Dopamine genes and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a review. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2003;28:27–38 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Gainetdinov RR. Dopamine transporter mutant mice in experimental neuropharmacology. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2008;377:301–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Brookes KJ, Mill J, Guindalini C, et al. A common haplotype of the dopamine transporter gene associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and interacting with maternal use of alcohol during pregnancy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:74–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A common haplotype of the dopamine transporter gene associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and interacting with maternal use of alcohol during pregnancy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:74–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Becker K, El-Faddagh M, Schmidt MH, et al. Interaction of dopamine transporter genotype with prenatal smoke exposure on ADHD symptoms. J Pediatr 2008;152:263–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Thapar A, Langley K, Fowler T, et al. Catechol O-methyltransferase gene variant and birth weight predict early-onset antisocial behavior in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:1275–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Caspi A, Langley K, Milne B, et al. A replicated molecular genetic basis for subtyping antisocial behavior in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008;65:203–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Langley K, Heron J, O'Donovan MC, et al. Genotype link with extreme antisocial behavior: the contribution of cognitive pathways. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:1317–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:1317–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Franke B, Neale BM, Faraone SV. Genome-wide association studies in ADHD. Hum Genet 2009;126:13–50 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Pe'er I, Yelensky R, Altshuler D, et al. Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet Epidemiol 2008;32:381–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Lasky-Su J, Neale BM, Franke B, et al. Genome-wide association scan of quantitative traits for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder identifies novel associations and confirms candidate gene associations. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2008;147B:1345–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Lesch KP, Timmesfeld N, Renner TJ, et al. Molecular genetics of adult ADHD: converging evidence from genome-wide association and extended pedigree linkage studies. J Neural Transm 2008;115:1573–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Mick E, Todorov A, Smalley S, et al. Family-based genome-wide association scan of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:898–905e3 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Family-based genome-wide association scan of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:898–905e3 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Neale BM, Lasky-Su J, Anney R, et al. Genome-wide association scan of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2008;147B:1337–44 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Neale BM, Medland SE, Ripke S, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:884–97 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Bastain TM, Lewczyk CM, Sharp WS, et al. Cytogenetic abnormalities in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41:806–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Stephen E, Kindley AD. Should children with ADHD and normal intelligence be routinely screened for underlying cytogenetic abnormalities? Arch Dis Child 2006;91:860–1 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Scherer SW, Lee C, Birney E, et al. Challenges and standards in integrating surveys of structural variation. Nat Genet 2007;39:S7–15 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Scherer SW, Lee C, Birney E, et al. Challenges and standards in integrating surveys of structural variation. Nat Genet 2007;39:S7–15 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Malhotra D, et al. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science 2007;316:445–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Sebat J, Levy DL, McCarthy SE. Rare structural variants in schizophrenia: one disorder, multiple mutations; one mutation, multiple disorders. Trends Genet 2009;25:528–35 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Elia J, Gai X, Xie HM, et al. Rare structural variants found in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder are preferentially associated with neurodevelopmental genes. Mol Psychiatry 2010;15:637–46 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Lesch KP, Selch S, Renner TJ, et al. Genome-wide copy number variation analysis in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: association with neuropeptide Y gene dosage in an extended pedigree. Mol Psychiatry 2011;16:491–503 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mol Psychiatry 2011;16:491–503 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Williams NM, Zaharieva I, Martin A, et al. Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet 2010;376:1401–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Counts CA, Nigg JT, Stawicki JA, et al. Family adversity in DSM-IV ADHD combined and inattentive subtypes and associated disruptive behavior problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005;44:690–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Pineda D, Ardila A, Rosselli M, et al. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in 4- to 17-year-old children in the general population. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1999;27:455–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Keenan HT, Hall GC, Marshall SW. Early head injury and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a1984. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Academy of Medical Sciences Identifying the environmental causes of disease: how should we decide what to believe and when to take action? London: Academy of Medical Sciences, 2007 [Google Scholar]

46. Collishaw S, Maughan B, Goodman R, et al. Time trends in adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004;45:1350–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collishaw S, Maughan B, Goodman R, et al. Time trends in adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004;45:1350–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Rutter M, Smith D, Psychosocial disorders in young people: time trends and their causes. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1995 [Google Scholar]

48. Meaney MJ. Epigenetics and the biological definition of gene x environment interactions. Child Dev 2010;81:41–79 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Langley K, Rice F, van den Bree MB, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy as an environmental risk factor for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder behaviour. A review. Minerva Pediatr 2005;57:359–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. D'Onofrio BM, Van Hulle CA, Waldman ID, et al. Smoking during pregnancy and offspring externalizing problems: an exploration of genetic and environmental confounds. Dev Psychopathol 2008;20:139–64 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Thapar A, Rice F, Hay D, et al. Prenatal smoking might not cause attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence from a novel design. Biol Psychiatry 2009;66:722–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biol Psychiatry 2009;66:722–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Linnet KM, Dalsgaard S, Obel C, et al. Maternal lifestyle factors in pregnancy risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and associated behaviors: review of the current evidence. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1028–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Mick E, Biederman J, Faraone SV, et al. Case–control study of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and maternal smoking, alcohol use, and drug use during pregnancy. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41:378–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Rice F, Harold GT, Boivin J, et al. The links between prenatal stress and offspring development and psychopathology: disentangling environmental and inherited influences. Psychol Med 2010;40:335–45 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Bhutta AT, Cleves MA, Casey PH, et al. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2002;288:728–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Weisglas-Kuperus N, van Goudoever JB, et al. Meta-analysis of neurobehavioral outcomes in very preterm and/or very low birth weight children. Pediatrics 2009;124:717–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Weisglas-Kuperus N, van Goudoever JB, et al. Meta-analysis of neurobehavioral outcomes in very preterm and/or very low birth weight children. Pediatrics 2009;124:717–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Hack M, Youngstrom EA, Cartar L, et al. Behavioral outcomes and evidence of psychopathology among very low birth weight infants at age 20 years. Pediatrics 2004;114:932–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Johnson S, Hollis C, Kochhar P, et al. Psychiatric disorders in extremely preterm children: longitudinal finding at age 11 years in the EPICure study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:453–63e1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Heinonen K, Räikkönen K, Pesonen AK, et al. Behavioural symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in preterm and term children born small and appropriate for gestational age: a longitudinal study. BMC Pediatr 2010;10:91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Lahti J, Räikkönen K, Kajantie E, et al. Small body size at birth and behavioural symptoms of ADHD in children aged five to six years. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006;47:1167–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006;47:1167–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Nigg JT. ADHD, lead exposure and prevention: how much lead or how much evidence is needed? Expert Rev Neurother 2008;8:519–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Bouchard MF, Bellinger DC, Wright RO, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and urinary metabolites of organophosphate pesticides. Pediatrics 2010;125:e1270–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Eskenazi B, Marks AR, Bradman A, et al. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and neurodevelopment in young Mexican-American children. Environ Health Perspect 2007;115:792–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Marks AR, Harley K, Bradman A, et al. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and attention in young Mexican-American children: the CHAMACOS study. Environ Health Perspect 2010;118:1768–74 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Rauh VA, Garfinkel R, Perera FP, et al. Impact of prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure on neurodevelopment in the first 3 years of life among inner-city children. Pediatrics 2006;118:e1845–59 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pediatrics 2006;118:e1845–59 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Eubig PA, Aguiar A, Schantz SL. Lead and PCBs as risk factors for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Environ Health Perspect 2010;118:1654–67 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Sagiv SK, Thurston SW, Bellinger DC, et al. Prenatal organochlorine exposure and behaviors associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in school-aged children. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:593–601 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Ballard W, Hall MN, Kaufmann L. Clinical inquiries. Do dietary interventions improve ADHD symptoms in children? J Fam Pract 2010;59:234–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Pelsser LM, Frankena K, Toorman J, et al. Effects of a restricted elimination diet on the behaviour of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (INCA study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:494–503 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Lifford KJ, Harold GT, Thapar A. Parent–child relationships and ADHD symptoms: a longitudinal analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2008;36:285–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Parent–child relationships and ADHD symptoms: a longitudinal analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2008;36:285–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Kreppner J, Kumsta R, Rutter M, et al. IV. Developmental course of deprivation-specific psychological patterns: early manifestations, persistence to age 15, and clinical features. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 2010;75:79–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

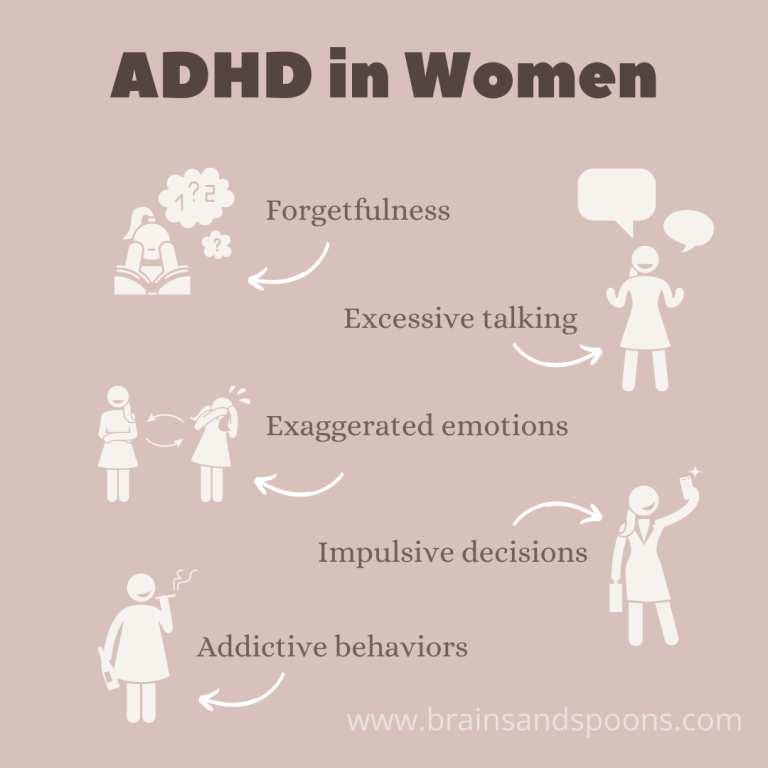

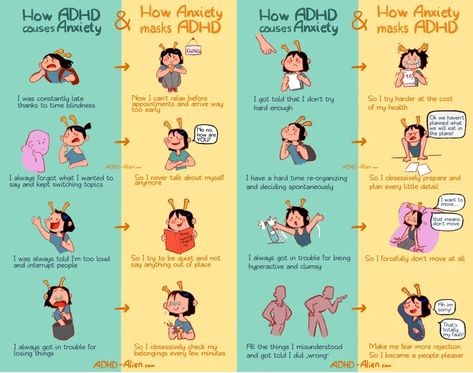

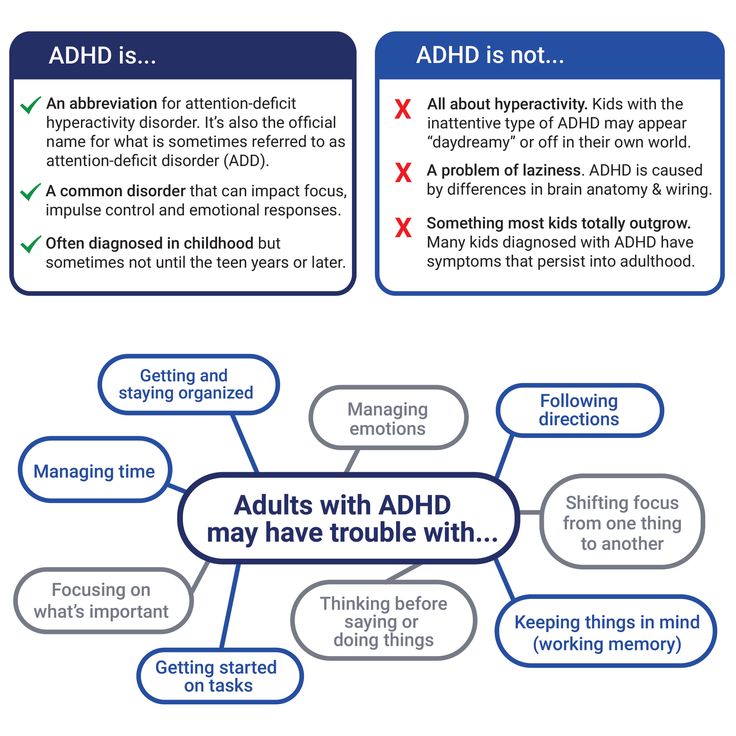

What Causes ADHD? Genes, Culture, Environment, Biology

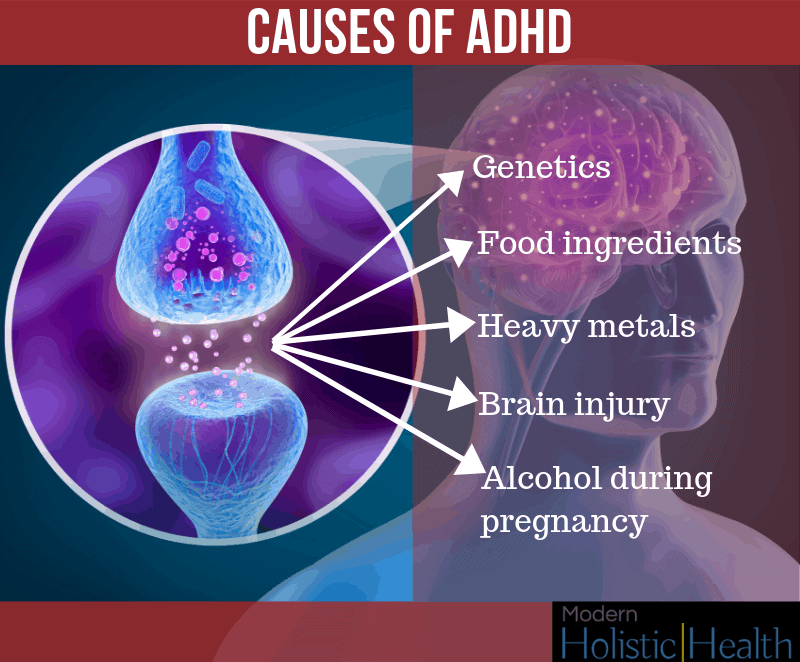

Most researchers point to genetics and heredity as deciding factors for who gets attention deficit disorder (ADHD or ADD) and who doesn’t. Scientists are investigating whether certain genes, especially ones linked to the neurotransmitter dopamine, may play a role in developing ADHD.

But Michael Ruff, M.D., a clinical associate professor of pediatrics at Indiana University, believes DNA is just part of the story. He is convinced that at least some cases of ADHD are a byproduct of our fast-paced, stressed-out, consumer-driven lifestyles. Let’s compare other research and expert insights to Dr. Ruff’s controversial theory on what causes ADHD — genetic vs. environmental triggers.

Let’s compare other research and expert insights to Dr. Ruff’s controversial theory on what causes ADHD — genetic vs. environmental triggers.

In an article in Clinical Pediatrics, Dr. Ruff called ADHD an ‘epidemic of modernity.’1 What does that mean? Is it the only explanation for ADHD?

Dr. Ruff: “I’m talking about the cultural environment that prevails today — the modern way of life and its impact on the developing brain. Today’s children are immersed in a world of instant messaging and rapid-fire video games and TV shows. Today’s parents are rushing around and working so hard to earn money to buy more stuff that they have less time to spend with their kids.”

“When kids get accustomed to such a rapid tempo, it’s hard for them to adjust to the comparatively slow pace of the classroom. They transfer the sense of urgency they’ve seen at home to their academic endeavors.”

“Researchers Daphne Bavelier and Shawn Green have demonstrated that playing action-based video games can improve processing speed. Torkel Klingberg has shown that consistent use of adaptive video games improves working memory skills and alters brain structure.”

Torkel Klingberg has shown that consistent use of adaptive video games improves working memory skills and alters brain structure.”

[Self-Test: Signs of Emotional Hyperarousal]

“Increases in grey matter in the right hippocampus, the cerebellum, and right prefrontal cortex were observed in a study of adults playing Super Mario Bros.2 Another study demonstrated that playing Tetris resulted in a larger cortex and increased brain efficiency.”3

“StarCraft, an action game, can lead to improved brain flexibility and problem solving. Playing Rayman Raving Rabbids can improve reading in children ages 7 to 13. Brain-training video games change brain functioning and slow the degree of mental decay in the elderly. All of these findings are well documented.”

“However, just as with virtually anything else in the world, too much of a good thing is bad for you. If you drink too much juice, eat too much fruit, or spend too much of your time jogging, there will be negative effects. Helping your child to have a balance of physical, social, unstructured, creative, and digital play, is vital. With video games, playing between 60 to 90 minutes a day appears to benefit kids the most.”

Helping your child to have a balance of physical, social, unstructured, creative, and digital play, is vital. With video games, playing between 60 to 90 minutes a day appears to benefit kids the most.”

ADDitude editors: The effects of video games on children with ADHD are neutral, except in extreme cases of negative obsessive fixation . While many games are advertised to improve cognition, memory, or other skills, the benefits of brain training are not proven.

There’s evidence that ADHD has a biological basis. Doesn’t that mean it’s hereditary?

Dr. Ruff: “Not entirely. The young brain is highly malleable. As it matures, some brain cells are continually making new connections with other brain cells, a process known as ‘arborizing,’ while others are being ‘pruned’ back. Arborizing and pruning determine how circuitry is wired in the prefrontal cortex, the region that is largely responsible for impulse control and the ability to concentrate. We’ve failed to acknowledge the extent to which environmental factors influence these processes. ”

”

ADDitude editors: Available evidence suggests that ADHD is genetic — passed down from parent to child. It seems to “run in families,” at least in some families.

- A child with ADHD is four times more likely to have a relative with ADHD.

- At least one-third of all fathers who had ADHD in their youth have children who have ADHD.

- The majority of identical twins share the ADHD trait.

A number of studies are now taking place to try to pinpoint the genes that lead to susceptibility for ADHD.4 Scientists are investigating many different genes that may play a role in developing ADHD, especially genes linked to the neurotransmitter dopamine. They believe it likely involves at least two genes, since ADHD is such a complex disorder.

There’s also evidence that toxins and pollution contribute to the development of ADHD, though more research is needed on these environmental factors.

[ADHD Is More Than Just Genes]

The role of environment in causing ADHD is an interesting theory, but is there evidence to support it?

Dr. Ruff: “There hasn’t been much research on the role of the environment in ADHD, but some studies are suggestive. In 2004, University of Washington researchers found that toddlers who watch lots of TV are more likely to develop attentional problems5. For every hour watched per day, the risk rose by 10 percent.

Ruff: “There hasn’t been much research on the role of the environment in ADHD, but some studies are suggestive. In 2004, University of Washington researchers found that toddlers who watch lots of TV are more likely to develop attentional problems5. For every hour watched per day, the risk rose by 10 percent.

“My group practice, in Jasper, Indiana, cares for more than 800 Amish families, who forbid TV and video games. We haven’t diagnosed a single child in this group with ADHD.”

“On the other hand, we care for several Amish families who have left the church and adopted a modern lifestyle, and we do see ADHD…in their kids. Obviously, the genes in these two groups are the same. What’s different is their environment.”

“There’s also some evidence to suggest that academic problems are rare in social and cultural groups that traditionally place a high value on education, hard work, and a tight-knit family structure. For example, a 1992 Scientific American study found that the children of Vietnamese refugees who settled in the U. S. did better in school and had fewer behavior problems than their native-born classmates.6 The researchers noted that the Vietnamese kids spent more time doing homework than did their peers, and that their parents emphasized obedience and celebrated learning as a pleasurable experience.”

S. did better in school and had fewer behavior problems than their native-born classmates.6 The researchers noted that the Vietnamese kids spent more time doing homework than did their peers, and that their parents emphasized obedience and celebrated learning as a pleasurable experience.”

ADDitude editors: While some environmental factors almost certainly do influence the development of ADHD, more than 1,800 studies have been conducted on the role of genetics in ADHD, creating strong evidence that ADHD is mostly genetic.

The genetic evidence for ADHD can be ignored, but not argued away. Studies of twins and families make it clear that genetic factors are the major causes of ADHD, says Russell Barkley, Ph.D., author of Taking Charge of Adult ADHD. In fact, an estimated 75 to 80 percent of variation in the severity of ADHD traits is the result of genetic factors.7 Some studies place this figure at over 90 percent.

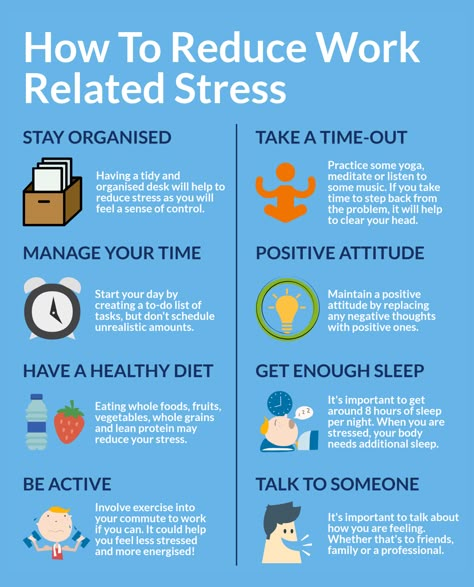

How can parents reduce the likelihood that their children will develop severe ADHD?

Dr. Ruff: “I counsel parents to limit the amount of TV their kids watch. I urge them to read to their kids every day, starting at age one, and to play board games and encourage other activities that promote reflection and patience. I also urge parents to do more slow-paced, step-by-step activities with their children, like cooking and gardening. Carve out more quiet time, when you’re not so busy. Put down the cell phone, and stop multitasking.”

Ruff: “I counsel parents to limit the amount of TV their kids watch. I urge them to read to their kids every day, starting at age one, and to play board games and encourage other activities that promote reflection and patience. I also urge parents to do more slow-paced, step-by-step activities with their children, like cooking and gardening. Carve out more quiet time, when you’re not so busy. Put down the cell phone, and stop multitasking.”

Edward Hallowell, M.D., practicing psychiatrist and founder of the Hallowell Center for Cognitive and Emotional Health: “We know enough about ADHD to offer science-based suggestions that can help reduce the likelihood of someone developing this condition.

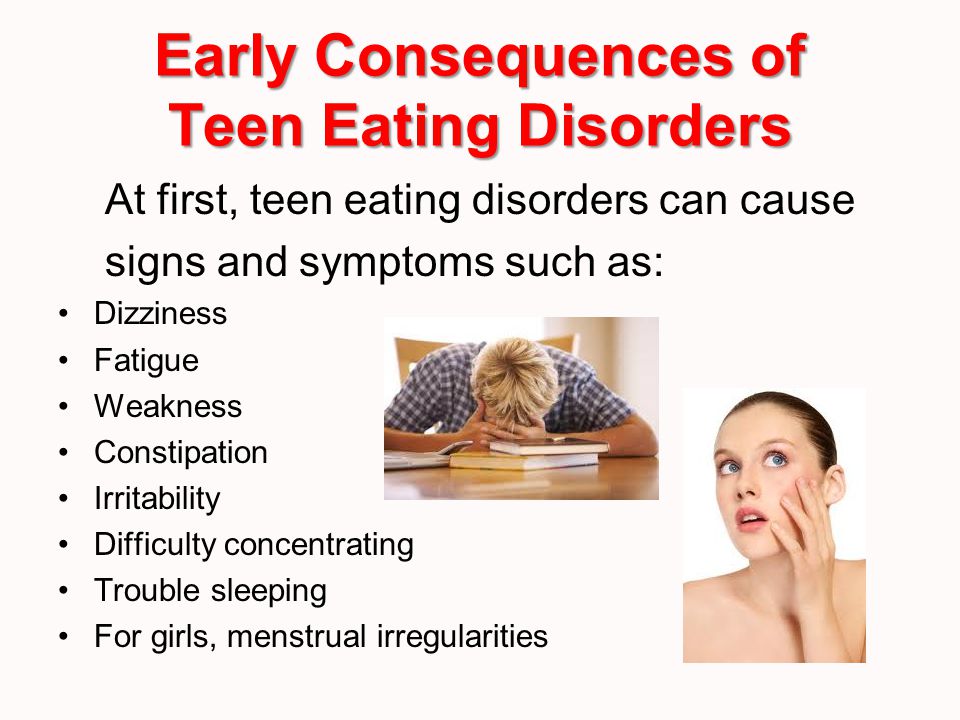

He advises expectant mothers not to “indulge in alcohol, cigarettes, or illicit drugs, or mistreat yourself or your unborn child in any other way. And get good prenatal care. Poor health care [while expecting a child] brings the risk of developing ADHD.”

“Make sure you have excellent medical care during [your] delivery…. Lack of oxygen at birth, trauma during birth, and infections acquired during delivery can cause ADHD.”

Lack of oxygen at birth, trauma during birth, and infections acquired during delivery can cause ADHD.”

“Once you give birth or bring home your adopted child, rejoice. The exciting and momentous journey of parenthood begins. That being said, your enchanting infant requires a lot of work. You may be sleep- and time-deprived, and tempted to plant your [child] in front of the TV to keep him occupied. But don’t. Studies have shown that infants and toddlers who watch more than two hours of television a day are more likely to develop ADHD than other children.”

“As you turn off the TV, turn on human interaction. Social connectedness bolsters the skills that minimize ADHD’s impact. So have family meals often, read aloud together, play board games, go outside and shoot hoops or throw a Frisbee — play, play, play. Also make sure that your child’s school is friendly and encourages social interaction.”

“These are practical measures that can help reduce the likelihood of a child developing ADHD. Remember, too, that inheriting the genes that predispose toward this condition doesn’t guarantee getting it. It is not ADHD that is inherited, but rather the predisposition toward developing it. Simply by reducing your child’s electronic time while increasing interpersonal time, you reduce the likelihood that the genes for ADHD will be expressed as he grows older — even if they were inherited.”

Remember, too, that inheriting the genes that predispose toward this condition doesn’t guarantee getting it. It is not ADHD that is inherited, but rather the predisposition toward developing it. Simply by reducing your child’s electronic time while increasing interpersonal time, you reduce the likelihood that the genes for ADHD will be expressed as he grows older — even if they were inherited.”

“A final note: You may not be able to prevent your child from developing ADHD, and that’s just fine. I have ADHD, and two of my three kids have it as well. With proper interventions, ADHD need not be a liability. In fact, it can be a tremendous asset. While a person can learn the skills to compensate for its downside, no one can learn the gifts that so often accompany ADHD: creativity, warmth, sharp intuitive skills, high energy, originality, and a ‘special something’ that defies description.”

If a child already has ADHD, can a change in the environment help control symptoms?

Dr. Ruff: “The brain can relearn executive functions like planning and attention well into the fourth decade of life. Consistent discipline, less TV and video games, and an emphasis on exercise, seem to be key. Exercise promotes on-task behavior and helps relieve the ‘desk fatigue’ that makes it hard for kids to sit still in class.”

Ruff: “The brain can relearn executive functions like planning and attention well into the fourth decade of life. Consistent discipline, less TV and video games, and an emphasis on exercise, seem to be key. Exercise promotes on-task behavior and helps relieve the ‘desk fatigue’ that makes it hard for kids to sit still in class.”

Colin Guare, a 24-year-old freelance writer and co-author of Smart But Scattered Teens: “If playing video games for hours guaranteed future success, I would be President by now.

“This isn’t the case, of course. Still, much of my mental dexterity and sharper executive function — brain-based skills required to execute tasks — can be chalked up to my hours spent in front of a screen. Gaming has helped me manage my ADHD-related shortcomings.”

ADDitude editors: Though parents will argue that video games are distracting, and an obstacle to learning, research suggests otherwise. In his book, What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy, James Paul Gee, Ph. D., notes that what makes a game compelling is its ability to provide a coherent learning environment for players. Not only are some video games a learning experience, says Gee, but they also facilitate metacognition (problem solving). In other words, good games teach players good learning habits.

D., notes that what makes a game compelling is its ability to provide a coherent learning environment for players. Not only are some video games a learning experience, says Gee, but they also facilitate metacognition (problem solving). In other words, good games teach players good learning habits.

Several video games offer individuals with ADHD the chance to have fun and to polish their executive skills at the same time. Four popular, entertaining, mentally rewarding, and cool games for teens are: Portal and Portal 2, Starcraft and Starcraft II: Wings of Liberty, The Zelda Franchise, and Guitar Hero.”

Randy Kulman, Ph.D., founder and president of LearningWorks for Kids: “Watch your child play Minecraft or other skill building games for a few minutes, and you’ll see that he plans, organizes, and problem-solves while engaged in a video game — skills we’d all like our ADHD kids to develop. Wouldn’t it be great if he could transfer those game-playing skills to everyday tasks? He can, with a little help from you. Use the following three steps to tap into the skill-building potential of video games:

Use the following three steps to tap into the skill-building potential of video games:

- Help your child identify the thinking and problem-solving skills that are necessary to play the game.

- Encourage metacognition and reflection by talking about how these skills are used in the real world.

- Engage your child in activities that use these skills, and then talk with your child about how the skills connect to game play.”

Kulman recommends the games Bad Piggies, Roblox, and Minecraft to build these skills.

How about medication?

Dr. Ruff: “There’s no doubt that medication can help control symptoms of ADHD. However, it’s problematic when doctors and parents believe ADHD to be simply the result of a ‘chemical imbalance,’ while failing to consider that a ‘lifestyle imbalance’ may also be involved. Even if medication is part of your child’s treatment plan, you still need to get the TV out of his bedroom.”

ADDitude editors: There’s no disputing that a healthy lifestyle — nutrient-rich foods, lots of water, exercise, and less stress — is better for ADHD. However, according to a study published online in the Journal of Attention Disorders in 2016, just the opposite is happening — children with ADHD engage in fewer healthy lifestyle behaviors than do their peers without the condition. There’s definitely room for improvement.

However, according to a study published online in the Journal of Attention Disorders in 2016, just the opposite is happening — children with ADHD engage in fewer healthy lifestyle behaviors than do their peers without the condition. There’s definitely room for improvement.

[When ADHD Is All In the Family]

1 Michael E. Ruff, MD, FAAP. ADD and Stimulant Use: An Epidemic of Modernity. Medscape (Feb. 2007). https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/550918

2 Kühn, S., Gleich, T., Lorenz, R. C., Lindenberger, U., Gallinat, J. Playing Super Mario induces structural brain plasticity: Grey matter changes resulting from training with a commercial video game. Molecular Psychiatry (Oct. 2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24166407

3 Richard J Haier, Sherif Karama, Leonard Leyba and Rex E Jung. MRI assessment of cortical thickness and functional activity changes in adolescent girls following three months of practice on a visual-spatial task. BMC Research Notes (2009). https://bmcresnotes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1756-0500-2-174

BMC Research Notes (2009). https://bmcresnotes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1756-0500-2-174

4 Zhang, Liuyan et al. “ADHDgene: a genetic database for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.” Nucleic acids research (Jan. 2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3245028/

5 Christakis DA, Zimmerman FJ, DiGiuseppe DL, McCarty CA. “Early television exposure and subsequent attentional problems in children.” Pediatrics (Apr. 2004). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15060216?dopt=Abstract&holding=npg

6 Caplan, Nathan, Marcella H. Choy, and John K. Whitmore. “Indochinese Refugee Families and Academic Achievement.” Scientific American (1992). http://www.jstor.org/stable/24938938

7 Franke, B et al. “The genetics of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults, a review.” Molecular psychiatry (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3449233/

nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3449233/

Previous Article Next Article

Additional reasons for suspension \ ConsultantPlus

- Main

- Documents

- Additional reasons for suspension

Additional suspension reasons

3

Clause 7 of Part 1 of Article 26 of Law N 218-FZ

Technical plan (TP) prepared in violation of Requirements N 953, in particular:

3.1

in the "Initial data" section of the TP there are no details of documents containing information from the USRN

In accordance with clause 27 of Requirements N 953, in the "Initial data" section of the TP, information about documents containing USRN information (extract from the USRN, cadastral plan of the territory) is the first to be included, while in the corresponding section of the TP such information (details of documents containing USRN information ) are not specified (or when preparing the TP, not all the information about real estate objects necessary for the preparation of the TP was used (indicate which ones) contained in the USRN, and the details of such documents are not given in the "Initial data" section of the TP)

The cadastral engineer or the customer of cadastral work needs to request information about the ACS .

.. (indicate which ones) and (or) indicate in the "Initial data" section of the TP the details of extracts from the USRN on such real estate objects or a cadastral plan of the territory containing information about such OH

.. (indicate which ones) and (or) indicate in the "Initial data" section of the TP the details of extracts from the USRN on such real estate objects or a cadastral plan of the territory containing information about such OH 3.2

no pagination in property declaration

In the declaration on the real estate object, prepared on paper and included in the TP, in violation of paragraph 10 of the Declaration Requirements, there is no numbering of sheets (through within the document)

Include in the TP a declaration on the property, on the pages of which the corresponding sheet numbers are affixed

3.3

the scheme of geodetic constructions is not drawn up in accordance with the measurement materials containing information on the geodetic justification of cadastral works

In violation of paragraph 53 of Requirements N 953, the section "Scheme of geodetic constructions" of the TP is not drawn up in accordance with the measurement materials containing information on the geodetic justification of cadastral work

Submit a technical proposal prepared in accordance with clause 53 of Requirements N 953

3.

4

4 special symbols displayed in the graphic part of the TP do not comply with those specified in Requirements N 953

1. When preparing the graphic part of the TP, the necessary special symbols were used, while not all conventional symbols (specify which ones) are displayed in the legend (in the list/list of symbols) 2. When preparing the graphic part of the TS, the necessary special symbols were used, but not all conventional symbols displayed in the legend (in the list/list of conventional symbols) (specify which ones) were used in the preparation of the graphic part of TP

Prepare the graphic part of the TP in accordance with the requirements for the preparation of the graphic part, using the necessary special symbols specified in the annex to the Requirements for the preparation of the technical plan and the composition of the information contained therein, and other symbols (indicate which ones), reflecting the applied symbols in legend

3.

5

5 the address of the property is indicated in the TP not in accordance with the information and structure contained in the federal information address system

In violation of subparagraph 7 of paragraph 43 of Requirements N 953, the address or location in the TP structure is incorrectly filled in (indicate how the address/location of the OKS is indicated in the TP, for example, "

50 " and specify how the OH address/location should be specified in the TP XML Schema). Submit the TP, in which in the address/location structure in the field "(the name of the field is given)" indicate the following "..." (indicate how the address/location of the TP should be specified in accordance with the XML structure of the TP schema)

3.

6

6 the address of the property is indicated in the declaration of the property not in accordance with the information and structure contained in the federal information address system

In violation of paragraph 12 of the Declaration Requirements, in the "Address (location) of the property" variable of the declaration on the property, the address of the OKS is not specified in a structured form in accordance with FIAS (indicate how the address should be specified) (in the absence of the address of the property assigned in the prescribed manner real estate in the line "Other" indicates the location of the property with the name of the subject of the Russian Federation, municipality, settlement, street (avenue, highway, lane, boulevard), as well as, if available, the building (structure) number, room number)

Fill in the requisite "Address (location) of the property" of the declaration of the property in accordance with paragraph 12 of the Requirements for the declaration

Main reasons for suspension Typical wording of the reasons for the suspension of state registration of an agreement for participation in shared construction concluded with the first participant in shared construction (hereinafter referred to as DDU)

Memory allocation errors can be caused by a slow increase in page file size - Windows Client

Twitter LinkedIn Facebook E-mail address

- Article

- Reading takes 2 minutes

This article provides a workaround for errors that occur when applications allocate memory frequently.

Scope: Windows 10 - All Editions

Original KB Number: 4055223Symptoms

Applications that allocate memory frequently may experience occasional out-of-memory errors. Such errors may lead to other errors or unexpected behavior in affected applications.

Cause

Memory allocation failures can occur due to the delays associated with increasing the page file size to support additional memory requirements on the system. A possible reason for these failures is that the page file size is set to "automatic". The automatic page file size starts with a small page file and automatically increases as needed.

The I/O system is made up of many components, including file system filters, file systems, volume filters, storage filters, and so on. Specific components in a given system can cause page file growth variability.

Workaround

To work around this issue, manually adjust the page file size. To do this, follow these steps:

- Press the Windows logo key + Pause/Break key to open System Properties .

- Select "Advanced system settings ", and then select "Settings" under " Performance" on the tab "Advanced ".

- Navigate to the "Advanced " tab, and then select "Edit " in section " Virtual Memory".

- Uncheck "Automatically manage paging file size for all drives".

- Select "Custom size", and then set the "Initial size" and "Maximum size" values for the paging file. It is recommended to set the initial size to 1.5 times the amount of RAM in the system.

- Click the " OK" button to apply the settings, and then restart the system. If you continue to receive out-of-memory errors, increase the initial page file size.

Microsoft has confirmed that this is a problem in Windows 10.

Intermittent build errors may occur when using the Microsoft Visual C++ Compiler (cl.