How can you help someone with an eating disorder

Helping Someone with an Eating Disorder

Understanding your loved one's eating disorder

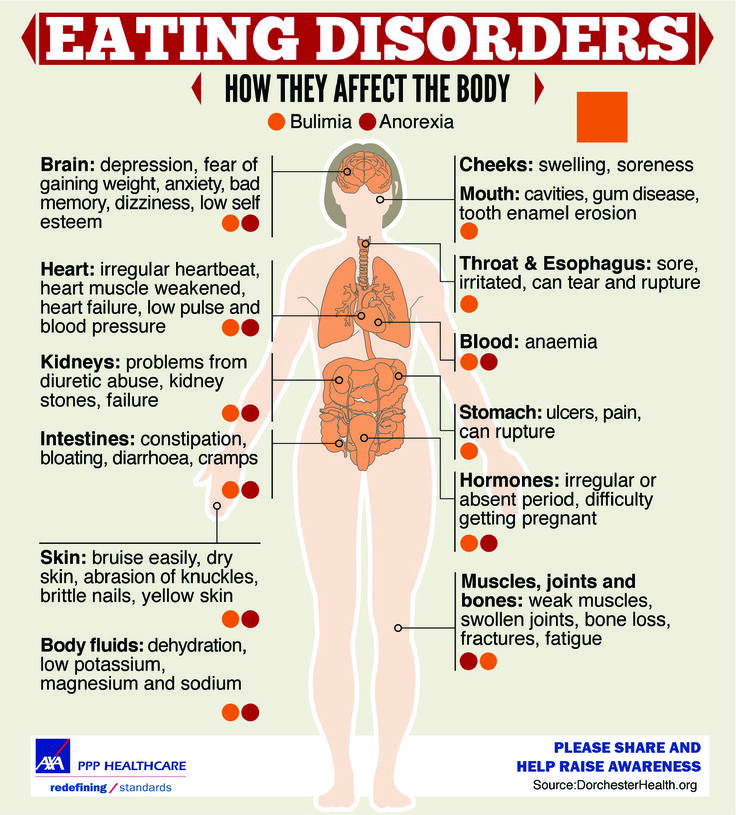

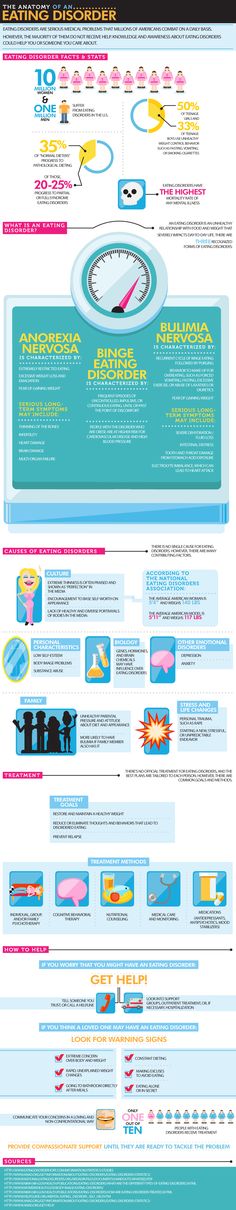

Eating disorders involve extreme disturbances in eating behaviors—following rigid diets, bingeing on food in secret, throwing up after meals, obsessively counting calories. It’s not easy to watch someone you care about damage their health—especially when the solution appears, at least on the outside, to be simple. But eating disorders are more complicated than just unhealthy dietary habits. At their core, they’re attempts to deal with emotional issues and involve distorted, self-critical attitudes about weight, food, and body image. It’s these negative thoughts and feelings that fuel the damaging behaviors.

People with eating disorders use food to deal with uncomfortable or painful emotions. Restricting food is used to feel in control. Overeating temporarily soothes sadness, anger, or loneliness. Purging is used to combat feelings of helplessness and self-loathing. Over time, people with an eating disorder lose the ability to see themselves objectively and obsessions over food and weight come to dominate everything else in their lives. Their road to recovery begins by identifying the underlying issues that drive their eating disorder and finding healthier ways to cope with emotional pain.

While you can’t force a person with an eating disorder to change, you can offer your support and encourage treatment. And that can make a huge difference to your loved one’s recovery.

Speak to a Licensed Therapist

The world's largest therapy service. 100% online. Get matched with a professional, licensed, and vetted therapist in less than 48 hours.

Get 20% off

Professional online therapy and tools based on proven CBT strategies. Get instant help, along with your own personalized therapy toolbox.

Get 20% off

Affiliate Disclosure

Types of eating disorders

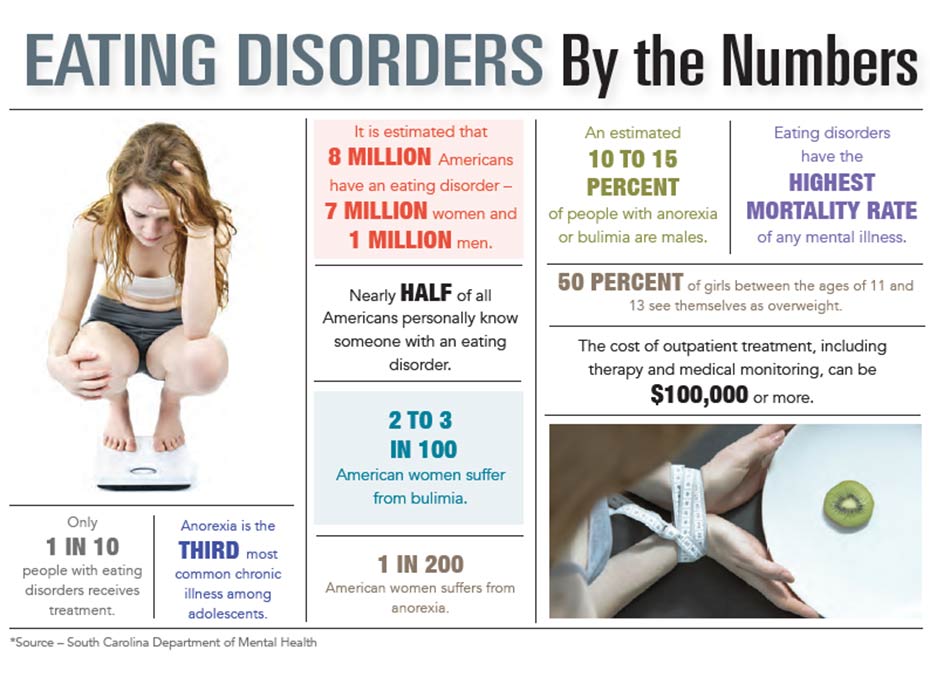

The most common eating disorders are:

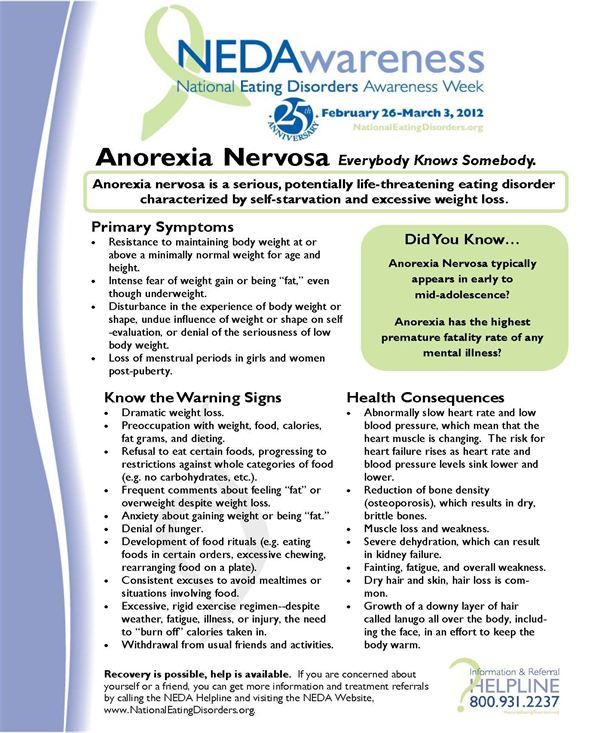

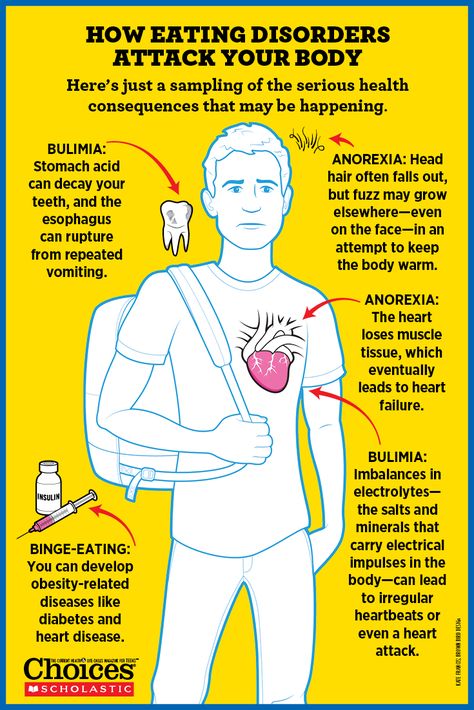

Anorexia. People with anorexia starve themselves out of an intense fear of becoming fat. Despite being underweight or even emaciated, they never believe they're thin enough. In addition to restricting calories, people with anorexia may also control their weight with exercise, diet pills, or purging.

People with anorexia starve themselves out of an intense fear of becoming fat. Despite being underweight or even emaciated, they never believe they're thin enough. In addition to restricting calories, people with anorexia may also control their weight with exercise, diet pills, or purging.

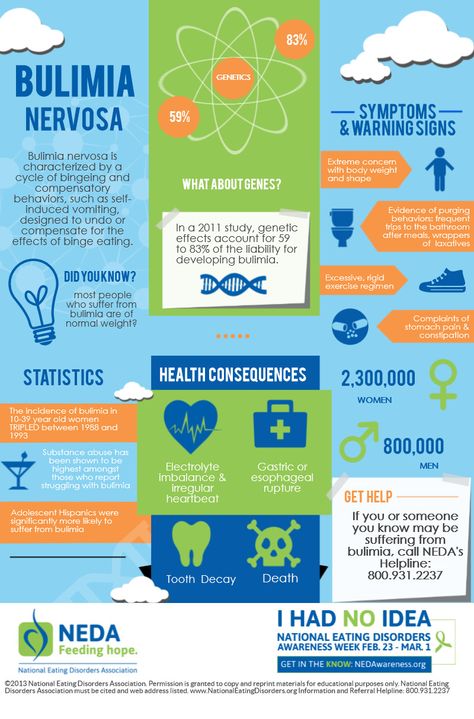

Bulimia. Bulimia involves a destructive cycle of bingeing and purging. Following an episode of out-of-control binge eating, people with bulimia take drastic steps to purge themselves of the extra calories. In order to avoid weight gain they vomit, exercise to excess, fast, or take laxatives.

Binge Eating Disorder. People with binge eating disorder compulsively overeat, rapidly consuming thousands of calories in a short period of time. Despite feelings of guilt and shame over these secret binges, they feel unable to control their behavior or stop eating even when uncomfortably full.

| Myths and Facts about Eating Disorders |

Myth 1: You have to be underweight to have an eating disorder.

Fact: People with eating disorders come in all shapes and sizes. Many individuals with eating disorders are of average weight or are overweight. |

| Myth 2: Only teenage girls and young women are affected by eating disorders. Fact: While eating disorders are most common in young women in their teens and early twenties, they are found in men and women of all ages—from children to older adults. |

| Myth 3: People with eating disorders are vain. Fact: It's not vanity that drives people with eating disorders to follow extreme diets and obsess over their bodies, but rather an attempt to deal with uncomfortable feelings. |

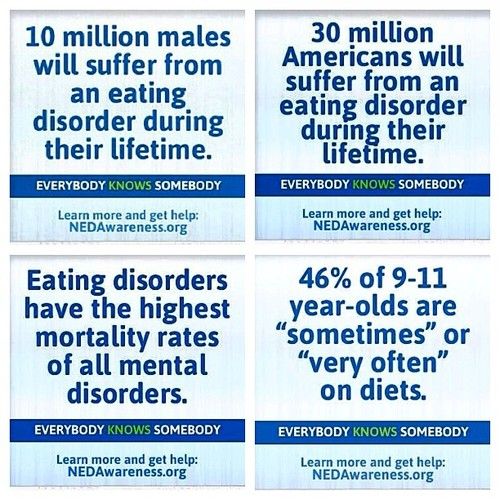

| Myth 4: Eating disorders aren't really that dangerous. Fact: Eating disorders are serious conditions that cause both physical and emotional damage. All eating disorders can lead to irreversible and even life-threatening health problems, such as heart disease, bone loss, stunted growth, infertility, and kidney damage. |

Warning signs of an eating disorder

Many people worry about their weight, what they eat, and how they look. This is especially true for teenagers and young adults, who face extra pressure to fit in and look attractive at a time when their bodies are changing. As a result, it can be challenging to tell the difference between an eating disorder and normal self-consciousness, weight concerns, or dieting. Further complicating matters, people with an eating disorder will often go to great lengths to hide the problem. However, there are warning signs you can watch for. And as eating disorders progress, the red flags become easier to spot.

Restricting food or dieting

- Making excuses to avoid meals or situations involving food (e.g. they had a big meal earlier, aren't hungry, or have an upset stomach)

- Eating only tiny portions or specific low-calorie foods, and often banning entire categories of food such as carbs and dietary fat

- Obsessively counting calories, reading food labels, and weighing portions

- Developing restrictive food rituals such as eating foods in certain orders, rearranging food on a plate, excessive cutting or chewing.

- Taking diet pills, prescription stimulants like Adderall or Ritalin, or even illegal drugs such as amphetamines (speed, crystal, etc.)

Bingeing

- Unexplained disappearance of large amounts of food in short periods of time

- Lots of empty food packages and wrappers, often hidden at the bottom of the trash

- Hoarding and hiding stashes of high-calorie foods such as junk food and sweets

- Secrecy and isolation; may eat normally around others, only to binge late at night or in a private spot where they won't be discovered or disturbed

Purging

- Disappearing right after a meal or making frequent trips to the bathroom

- Showering, bathing, or running water after eating to hide the sound of purging

- Using excessive amounts of mouthwash, breath mints, or perfume to disguise the smell of vomiting

- Taking laxatives, diuretics, or enemas

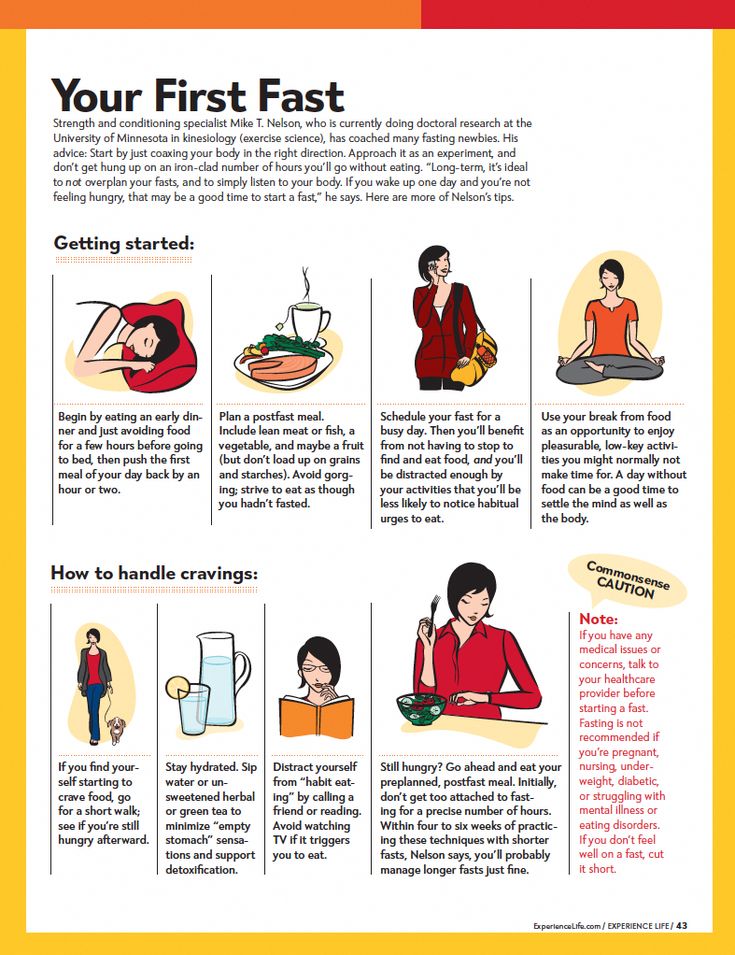

- Periods of fasting or compulsive, intense exercising, especially after eating

- Frequent complaints of sore throat, upset stomach, diarrhea, or constipation

- Discolored teeth

Distorted body image and altered appearance

- Extreme preoccupation with body or weight (e.

g. constant weigh-ins, spending lots of time in front of the mirror inspecting and criticizing their body)

g. constant weigh-ins, spending lots of time in front of the mirror inspecting and criticizing their body) - Significant weight loss, rapid weight gain, or constantly fluctuating weight

- Frequent comments about feeling fat or overweight, or about a fear of gaining weight

- Wearing baggy clothes or multiple layers in an attempt to hide weight

Worried about someone? Speak out!

If you notice the warning signs of an eating disorder in a friend or family member, it's important to speak up. You may be afraid that you're mistaken, or that you'll say the wrong thing, or you might alienate the person. However, it's important that you don't let these worries stop you from voicing your concerns.

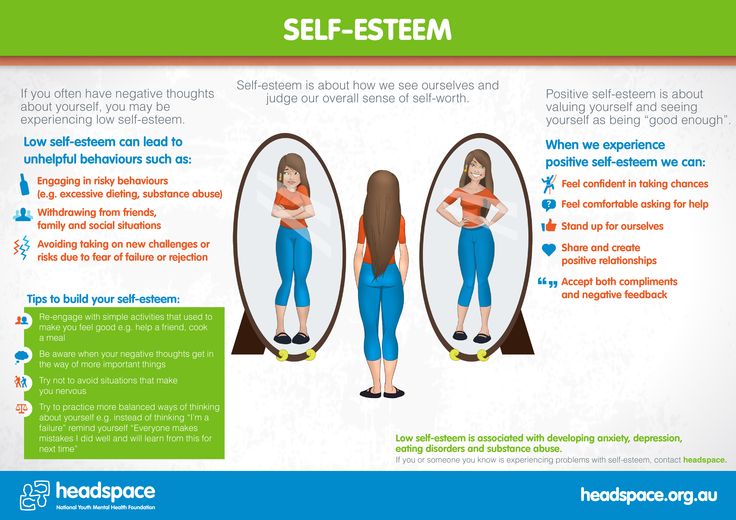

People with eating disorders are often afraid to ask for help. Some are struggling just as much as you are to find a way to start a conversation about their problem, while others have such low self-esteem they simply don't feel that they deserve any help. Whatever the case, eating disorders will only get worse without treatment, and the physical and emotional damage can be severe. The sooner you start to help, the better their chances of recovery. While you can't force someone with an eating disorder to get better, having supportive relationships is vital to their recovery. Your love and encouragement can make all the difference.

Whatever the case, eating disorders will only get worse without treatment, and the physical and emotional damage can be severe. The sooner you start to help, the better their chances of recovery. While you can't force someone with an eating disorder to get better, having supportive relationships is vital to their recovery. Your love and encouragement can make all the difference.

How to talk to someone about their eating disorder

The decision to make a change is rarely an easy one for someone with an eating disorder. If the eating disorder has left them malnourished, it can distort the way they think—about their body, the world around them, even your motivations for trying to help. Bombarding them with dire warnings about the health consequences of their eating disorder or trying to bully them into eating normally probably won't work. Eating disorders often fill an important role in the person's life—a way to cope with unpleasant emotions—so the allure can be strong. Since you may be met with defensiveness or denial, you'll need to tread carefully when broaching the subject.

Since you may be met with defensiveness or denial, you'll need to tread carefully when broaching the subject.

Pick a good time. Choose a time when you can speak to the person in private without distractions or constraints. You don't want to have to stop in the middle of the conversation because of other obligations! It's also important to have the conversation at a time of emotional calm. Don't try to have this conversation right after a blow up.

Explain why you're concerned. Be careful to avoid lecturing or criticizing, as this will only make your loved one defensive. Instead, refer to specific situations and behaviors you've noticed, and why they worry you. Your goal at this point is not to offer solutions, but to express your concerns about the person's health, how you much you love them, and your desire to help.

Be prepared for denial and resistance. There's a good chance your loved one may deny having an eating disorder or become angry and defensive. If this happens, try to remain calm, focused, and respectful. Remember that this conversation likely feels very threatening to someone with an eating disorder. Don't take it personally.

If this happens, try to remain calm, focused, and respectful. Remember that this conversation likely feels very threatening to someone with an eating disorder. Don't take it personally.

Ask if the person has reasons for wanting to change. Even if your loved one lacks the desire to change for themselves, they may want to change for other reasons: to please someone they love, to return to school or work, for example. All that really matters is that they are willing to seek help.

Be patient and supportive. Don't give up if the person shuts you down at first. It may take some time before they're willing to open up and admit to having a problem. The important thing is opening up the lines of communication. If they are willing to talk, listen without judgment, no matter how out of touch they may sound. Make it clear that you care, that you believe in them, and that you'll be there in whatever way they need, whenever they're ready.

What not to do

Avoid ultimatums. Unless you're dealing with an underage child, you can't force someone into treatment. The decision to change must come from them. Ultimatums merely add pressure and promote more secrecy and denial.

Unless you're dealing with an underage child, you can't force someone into treatment. The decision to change must come from them. Ultimatums merely add pressure and promote more secrecy and denial.

Avoid commenting on appearance or weight. People with eating disorders are already overly focused on their bodies. Even assurances that they're not fat play into their preoccupation with being thin. Instead, steer the conversation to their feelings. Why are they afraid of being fat? What do they think they'll achieve by being thin?

Avoid shaming and blaming. Steer clear of accusatory “you” statements like, “You just need to eat!” Or, “You're hurting yourself for no reason.” Use “I” statements instead. For example: “I find it hard to watch you wasting away.” Or, “I'm scared when I hear you throwing up.”

Avoid giving simple solutions. For example, “All you have to do is accept yourself.” Eating disorders are complex problems. If it were that easy, your loved one wouldn't be suffering.

If it were that easy, your loved one wouldn't be suffering.

Encouraging a person to get help

Aside from offering support, the most important thing you can do for a person with an eating disorder is to encourage treatment. The longer an eating disorder remains undiagnosed and untreated, the harder it is on the body and the more difficult it is to overcome, so urge your loved one to see a doctor right away.

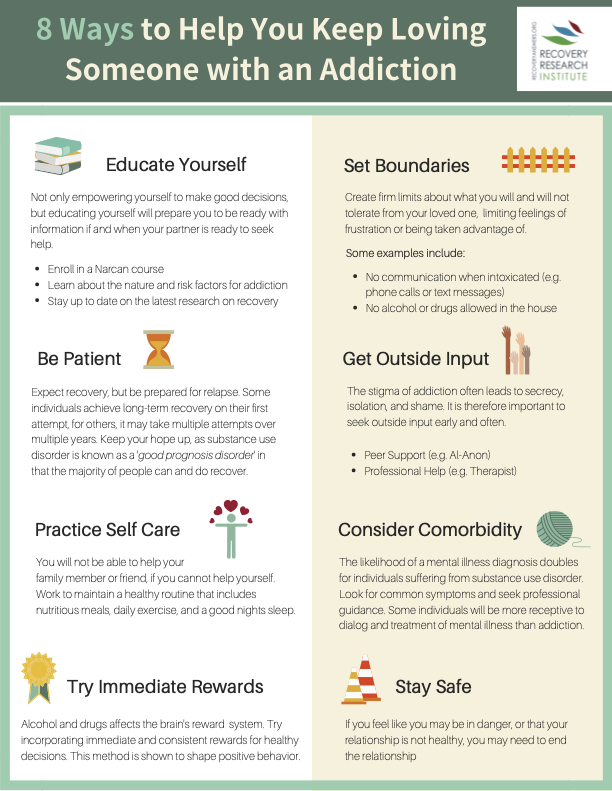

A doctor can assess your loved one's symptoms, provide an accurate diagnosis, and screen for any medical problems that might be involved. The doctor can also determine whether there are any co-existing conditions that require treatment, such as depression, substance abuse, or an anxiety disorder.

If your friend or family member is hesitant to see a doctor, ask them to get a physical just to put your worries to rest. It may help if you offer to make the appointment or go along on the first visit.

Treatments for eating disorders

The right treatment approach for each person depends on their specific symptoms, issues, and strengths, as well as the severity of the disorder. To be most effective, treatment for an eating disorder must address both the physical and psychological aspects of the problem. The goal is to treat any medical or nutritional needs, promote a healthy relationship with food, and teach constructive ways to cope with unpleasant emotions and life's challenges.

To be most effective, treatment for an eating disorder must address both the physical and psychological aspects of the problem. The goal is to treat any medical or nutritional needs, promote a healthy relationship with food, and teach constructive ways to cope with unpleasant emotions and life's challenges.

A team approach is often best. Those who may be involved in treatment include medical doctors, mental health professionals, and nutritionists. The participation and support of family members also makes a big difference in the success of eating disorder treatment.

Medical treatment. The first priority is to address and stabilize any serious health issues. Hospitalization or residential treatment may be necessary if your loved one is dangerously malnourished, suffering from medical complications, severely depressed or suicidal, or resistant to treatment. Outpatient treatment is an option when the patient is not in immediate medical danger.

Nutritional counseling. Dietitians or nutritionists can help your loved one design balanced meal plans, set dietary goals, and reach or maintain a healthy weight. Counseling may also involve education about proper nutrition.

Dietitians or nutritionists can help your loved one design balanced meal plans, set dietary goals, and reach or maintain a healthy weight. Counseling may also involve education about proper nutrition.

Therapy. Therapy plays a crucial role in eating disorder treatment. Its goals are to identify the negative thoughts and feelings that are behind the disordered eating behaviors, and to replace them with healthier and less distorted attitudes. Another important goal is to teach the person how to deal with difficult emotions, relationship problems, and stress in a productive, rather than a self-destructive way.

Common types of therapy for eating disorders

Individual therapy. Explores both the eating disorder symptoms and the underlying emotional and interpersonal issues that fuel them. The focus is on increasing self-awareness, challenging dysfunctional beliefs, and improving self-esteem and sense of control.

Family therapy. Examines the family dynamics that may contribute to an eating disorder or interfere with recovery. Often includes some therapy sessions without the patient—a particularly important element when the person with the eating disorder denies having a problem.

Examines the family dynamics that may contribute to an eating disorder or interfere with recovery. Often includes some therapy sessions without the patient—a particularly important element when the person with the eating disorder denies having a problem.

Group therapy. Allows people with eating disorders to talk with each other in a supervised setting. Helps to reduce the isolation many people with eating disorders feel. Group members support each other through recovery and share their experiences and advice.

Dealing with eating disorders in the home

As a parent, there are many things you can do to support your child's eating disorder recovery—even if they are still resisting treatment.

Set a positive example. You have more influence than you think. Instead of dieting, eat nutritious, balanced meals. Be mindful about how you talk about your body and your eating. Avoid self-critical remarks or negative comments about others' appearance. Instead, focus on the qualities on the inside that really make a person attractive.

Instead, focus on the qualities on the inside that really make a person attractive.

Make mealtimes fun. Try to eat together as a family as often as possible. Even if your child isn't willing to eat the food you've prepared, encourage them to join you at the table. Use this time together to enjoy each other's company, rather than talking about problems. Meals are also a good opportunity to show your child that food is something to be enjoyed rather than feared.

Avoid power struggles over food. Attempts to force your child to eat will only cause conflict and bad feelings and likely lead to more secrecy and lying. That doesn't mean you can't set limits or hold your child accountable for their behavior. But don't act like the food police, constantly monitoring your child's behavior.

Encourage eating with natural consequences. While you can't force healthy eating behaviors, you can encourage them by making the natural consequences of not eating unappealing. For example, if your child won't eat, they can't go to dance class or drive the car because, in their weakened state, it wouldn't be safe. Emphasize that this isn't a punishment, but simply a natural medical consequence.

For example, if your child won't eat, they can't go to dance class or drive the car because, in their weakened state, it wouldn't be safe. Emphasize that this isn't a punishment, but simply a natural medical consequence.

Do whatever you can to promote self-esteem. in your child in intellectual, athletic, and social endeavors. Give boys and girls the same opportunities and encouragement. A well-rounded sense of self and solid self-esteem are perhaps the best antidotes to disordered eating.

Don't blame yourself. Parents often feel they must take on responsibility for the eating disorder, which is something they truly have no control over. Once you can accept that the eating disorder is not anyone's fault, you can be freed to take action that is honest and not clouded by what you “should” or “could” have done.

Supporting a loved one's recovery

Recovering from an eating disorder takes time. There are no quick fixes or miracle cures, so it's important to have patience and compassion. Don't put unnecessary pressure on your loved one by setting unrealistic goals or demanding progress on your own timetable. Provide hope and encouragement, praise each small step forward, and stay positive through struggles and setbacks.

Don't put unnecessary pressure on your loved one by setting unrealistic goals or demanding progress on your own timetable. Provide hope and encouragement, praise each small step forward, and stay positive through struggles and setbacks.

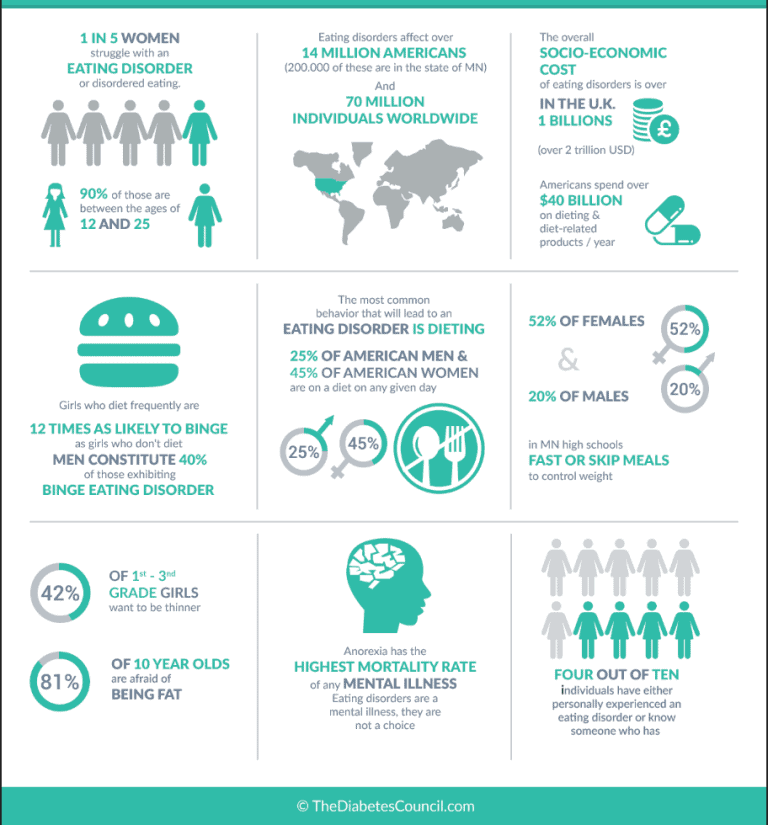

Learn about eating disorders. The more you know, the better equipped you'll be to help your loved one, avoid pitfalls, and cope with challenges.

Listen without judgment. Show that you care by asking about your loved one's feelings and concerns—and then truly listening. Resist the urge to advise or criticize. Simply let your friend or family member know that they're being heard. Even if you don't understand what they're going through, it's important to validate your loved one's feelings.

Be mindful of triggers. Avoid discussions about food, weight, eating or making negative statements about your own body. But don't be afraid to eat normally in front of someone with an eating disorder. It can help set an example of a healthy relationship with food.

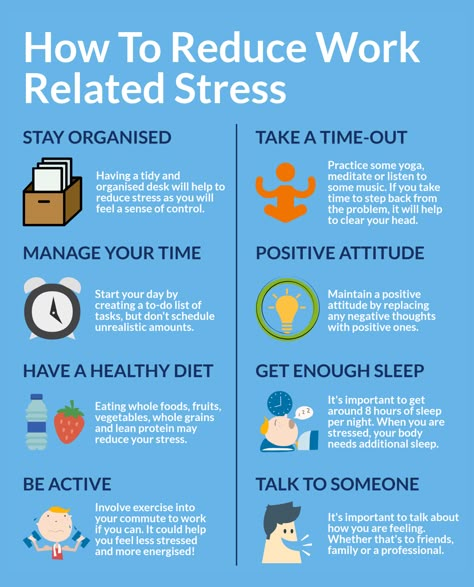

Take care of yourself. Don't become so preoccupied with your loved one's eating disorder that you neglect your own needs. Make sure you have your own support, so you can provide it in turn. Whether that support comes from a trusted friend, a support group, or your own therapist, it's important to have an outlet to talk about your feelings and emotionally recharge. It's also important to schedule time into your day for relaxing and doing things you enjoy.

Helplines and support

- In the U.S.

National Eating Disorders Association or call 1-800-931-2237 (National Eating Disorders Association)

- UK

Beat Eating Disorders or call 0345 643 1414 (Helpfinder)

- Australia

Butterfly Foundation for Eating Disorders or call 1800 33 4673 (National Eating Disorders Collaboration)

- Canada

Service Provider Directory or call 1-866-633-4220 (NEDIC)

Last updated or reviewed on February 23, 2023

Supporting someone with an eating disorder

The eating disorder can cause your loved one to misinterpret what is being said to them, which can leave you unsure of what to say and concerned about upsetting them. Below are some examples of things that you may innocently say, and what the eating disorder may cause your loved one to hear instead. It could be helpful to share these with other people likely to talk to your loved one, to help them to understand more about the eating disorder and avoid upsetting conversations.

Below are some examples of things that you may innocently say, and what the eating disorder may cause your loved one to hear instead. It could be helpful to share these with other people likely to talk to your loved one, to help them to understand more about the eating disorder and avoid upsetting conversations.

Just eat normally.

What may be heard: You’re not trying hard enough, it’s not difficult to eat, it’s your fault, you need to get over this.

Positive alternative: To outsiders it may seem like people with eating disorders just need to eat, or just need to stop purging or binge eating. This is not the case – eating disorders are not a choice but are severe mental illnesses that the person needs supporting through. It is therefore important to acknowledge to the person that you know it’s difficult for them, and you are there to support them.

You look well.

What may be heard: You look fat, you have gained weight, you’re greedy, you’re healthy now so things are easy for you.

Positive alternative: Any comments to do with your loved one looking “healthier” or “better” are often taken to mean they have put on weight. Instead of commenting on their physical appearance, try to ask the person how they are, or compliment something about your loved one that is unrelated to their body such as an item of clothing or an accessory.

I wish I had your control.

What may be heard: You are lucky to have an eating disorder, you are in control of the illness, it’s a good thing to be obsessive with food, weight and shape.

Positive alternative: Often eating disorders are used as a coping mechanism and a way to feel in control. However, when someone is suffering from an eating disorder the illness controls them and fighting against the thoughts and behaviours is extremely difficult. Avoid commenting on the eating disorder as if it is the person’s choice.

You just need to stop eating so much.

What may be heard: You are fat, you are greedy, binge eating isn’t a problem, you are making this up, it is easy to stop binge eating.

Positive alternative: Acknowledge how difficult things are for your loved one, and how distressing the eating disorder must be. Let them know that you are there to support them.

Get well soon.

What is heard: It’s easy to get over this, you aren’t trying hard enough, you are being a burden, hurry up and get better.

Positive alternative: Reassure your loved one that although you recognise how difficult things are for them, you are there for them and will continue to be throughout. Let them know how proud you are of them for challenging the illness.

I wish I had your body.

What is heard: You are lucky to have an eating disorder, you are just doing this to look a certain way, you need to keep doing the disordered behaviours.

Positive alternative: Try to avoid discussing your own weight and shape in front of your loved one as it can be unhelpful for them to hear. Instead focus on topics away from body image, food or exercise.

I can easily finish a packet of biscuits so know exactly how you feel.

What is heard: Everyone eats that way, you don’t have a problem, it is normal to binge eat, you don’t deserve support.

Positive alternative: While many people will overeat on occasion, and this may be triggered by difficult emotions, this is not the same as having binge eating disorder. Binge eating disorder is extremely distressing for the person and involves the person feeling a loss of control while eating a much larger amount of food than most people would eat in similar circumstances. It is good to be understanding, but important to avoid trivialising what the person is going through.

5 Ways to Support the Person with an Eating Disorder » MAKEOUT - A Gender & Sexuality Magazine

Eating Disorder Recovery (EDD) is, simply put, a long-term effort to give up erratic eating behavior for the sake of your health. And most often this process is felt as a constant balancing somewhere “on the edge”.

Constantly surrounded by things that can trigger a relapse, many people recovering from eating disorders behave in the same way as those who struggle with alcohol addiction: they are "stuck" in a world where their destructive behavior can easily return.

The need to constantly be strong in order to fight bad thoughts and self-destructive actions is debilitating. One wrong decision can be a disaster. Therefore, a supportive environment is very important on the path to recovery.

©Wendy van SantenBut where do I start? How to organize a safe space for someone you love? This article can be a good starting point.

While I hope that people with eating disorders find it useful (and share it with their loved ones), it is not primarily intended for them.

To be precise, this article is written for those who say, “I know that my friend or someone in my family has an eating disorder. What should I do now?

1. Find out more

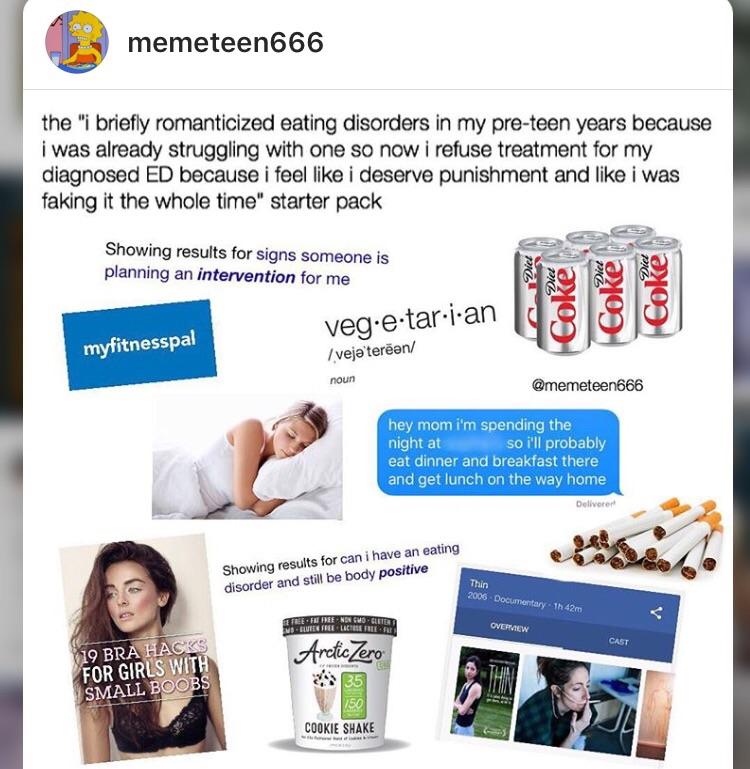

Before supporting a loved one in need, it is important to deal with your prejudices and delusions on your own. You can find a book about eating disorders, watch a documentary, or find personal stories of people with eating disorders online. Harriet Brown's Brave Girl Eating (2010) and Laurie Holes Andersen's Wintergirls (2010) are my favorite books. And then there is the documentary film "THIN" ("Anorexia", 2006): it shows the life of rehabilitation centers without embellishment.

You can find a book about eating disorders, watch a documentary, or find personal stories of people with eating disorders online. Harriet Brown's Brave Girl Eating (2010) and Laurie Holes Andersen's Wintergirls (2010) are my favorite books. And then there is the documentary film "THIN" ("Anorexia", 2006): it shows the life of rehabilitation centers without embellishment.

You can look at informal online resources (such as social media groups) about eating disorders if you want to know how some people with these disorders think, but don't jump to conclusions about your loved one's experience based on information from such sources. Remember, your lover should not be the first and only source of information about what it's like to experience or recover from an eating disorder. There are thousands of resources that can be found just by googling. A little effort in self-education will serve you well in the future.

©Wendy van Santen2. Be a good ally

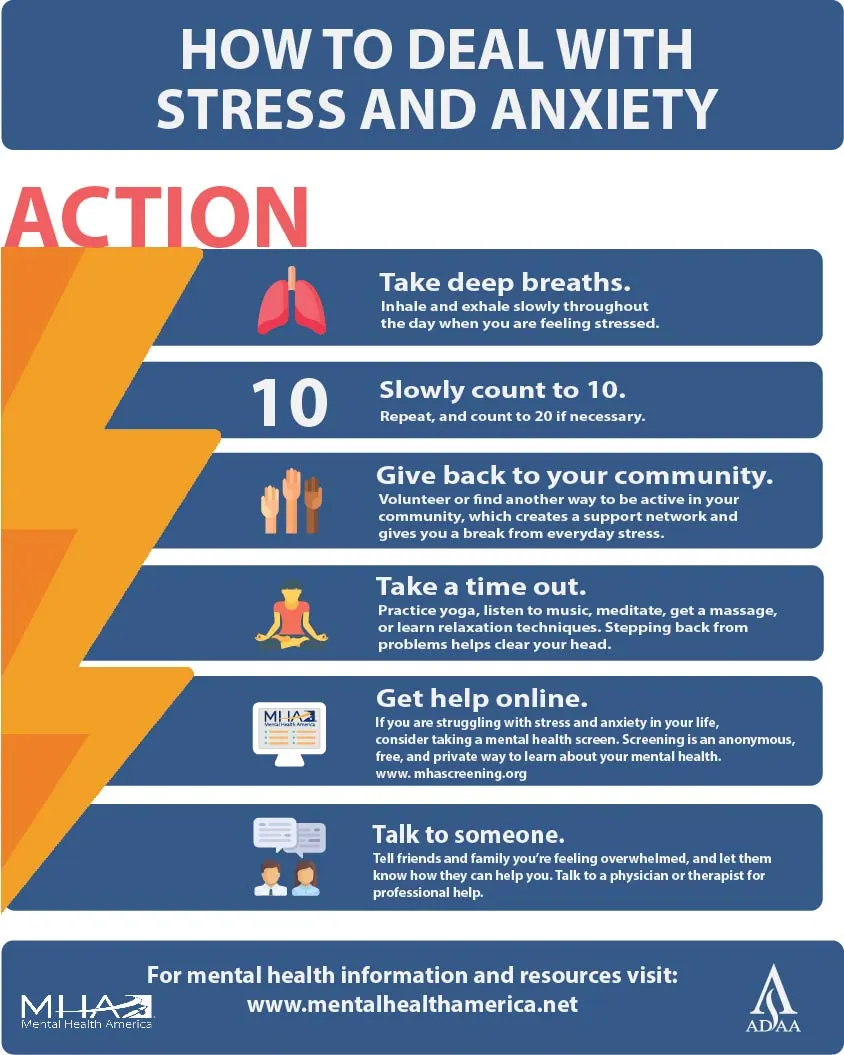

Be present in the life of your loved one, but don't pressure them. Listen if she needs it, but don't make her say something if she doesn't want to. Try not to criticize or judge the words of your loved one, even if you find it hard to contain yourself. Count to 5 (or 10 or even 20!) before answering. Avoid unsolicited advice.

Listen if she needs it, but don't make her say something if she doesn't want to. Try not to criticize or judge the words of your loved one, even if you find it hard to contain yourself. Count to 5 (or 10 or even 20!) before answering. Avoid unsolicited advice.

Remember, a person with eating disorders needs to regain his independence.

Try to understand her feelings together and work with their manifestations. Talk about your feelings and formulate your wishes based on your own thoughts and emotions, trying not to offend or blame others. Try to do this with the help of personal pronouns: "I", "me", "me". Ask your loved one to do the same. If you want to offer something, do it gently, without pressure, without saying that he_a "should" do something. If you don't understand something or want to know more information, just ask.

But always be prepared for the fact that the person you love may not want to discuss certain things. Try to approach the questions in a casual manner: “Do you mind if I ask you a few questions? You don't have to answer if you don't want to. " Be sympathetic, but collected.

" Be sympathetic, but collected.

3. Avoid talking about physicality

Don't draw attention to her body, don't try to deal with her experience by talking about her own weight or body. Phrases such as "I would like a figure like yours!" or "I already think you're beautiful" may seem supportive, but they can also be harmful to a person in remission.

Your kind compliments may sound very different to her, so it's best to avoid them. Remember! What seems like a passing remark about your own body (such as "Those jeans got big on me" or "I feel so fat today") can be a trigger for a person with an eating disorder.

Instead, focus on accomplishments and character traits that are not related to the body. Take your attention away from the physical. This is difficult to do in a culture where we are constantly open about the body (especially our dissatisfaction with it), so it may take some effort.

©Wendy van Santen4. Be sensitive to the amount of food

Food and quantity can be very stressful for people with eating disorders. Keep this in mind when planning, for example, gifts or activities (friendly advice: going out to eat or go shopping are not the best ideas). If you are eating in front of a person with an eating disorder, avoid talking about the food (“You can afford to eat more” or “You can order more than just a salad”).

Keep this in mind when planning, for example, gifts or activities (friendly advice: going out to eat or go shopping are not the best ideas). If you are eating in front of a person with an eating disorder, avoid talking about the food (“You can afford to eat more” or “You can order more than just a salad”).

Numbers often define (and therefore worry about) people with eating disorders. People in remission find it difficult to rewire their thinking to stop making constant calculations. Therefore, you'd better avoid any statements about food, weight, calories, etc. (“I lost 5 kg” or “There are 600 calories in this dish”). Think about what you are saying.

When in doubt, ask the person about her triggers.

5. Recognize accomplishments, but do so tactfully

When a person is in remission, they (finally!) begin to overcome their aversion to food and stabilize their weight. When your loved one overcomes the fear of food and reaches the desired weight, it is worth celebrating. But think twice how this holiday is worth celebrating.

But think twice how this holiday is worth celebrating.

Remember point number 3: avoid talking about the body. When you say to someone who has (had) an eating disorder, "you look so healthy!", he may interpret it as "you look fat". Focus on the achievement itself, not on its external manifestations. A simple “I’m proud of you” or “You did a great job, keep going” will be better.

©Wendy van SantenBONUS: Remember to take care of yourself

You are not responsible for someone else's treatment. It's not in your power. Being close to those who need support is a sincere act of caring. You are doing something really important for a person.

But don't forget your own needs. It's okay if the current situation starts to put pressure on you. It's okay if you need to take a step back. It's okay if you're confused, if you have questions. Take care of yourself. The most important thing is that you are trying to help.

Eating is very hard not only for the person, but also for those who try to be around. It's complicated. And all people are different.

It's complicated. And all people are different.

But no matter how different people with eating disorders are, they all want their loved ones to know that the best way to support a person with eating disorders is to ask what she needs and be honest in her answers, reactions and assessment of her abilities.

Eating disorder (ED) - symptoms and treatment

Photo: canva.com

-

Types of Eating Disorders

-

Causes of RPP

-

What signs should alert?

-

How exactly can you help a loved one with an eating disorder?

-

Which doctor should I contact with RPP?

-

How to choose a doctor?

Modern psychological forums and websites are full of questions: "How to help a loved one with an eating disorder?".

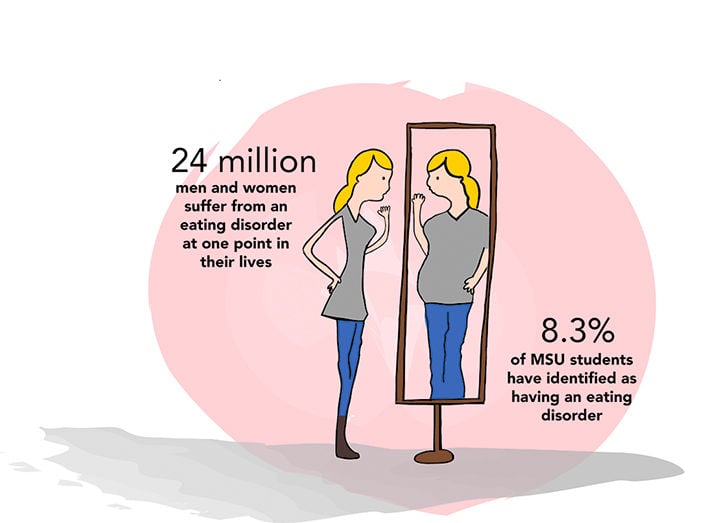

Indeed, in our time of emergency and stress, the number of people suffering from eating disorders is on the rise. Such an alarming trend is connected not only with the increased level of stress in the world, but also with the fashion for a graceful toned figure. The situation is aggravated by extensive propaganda and demonstration of reference proportions of thin bodies in social networks.

Such an alarming trend is connected not only with the increased level of stress in the world, but also with the fashion for a graceful toned figure. The situation is aggravated by extensive propaganda and demonstration of reference proportions of thin bodies in social networks.

Let's take a look at the types, signs and causes of eating disorders and how you can help your loved ones in this dangerous situation.

Types of eating disorders

Food is a source of existence and energy only if it is rationally consumed in the required quantity. Any deviation from the norm is harmful to the psyche and physical health.

An eating disorder is actually a mental illness, not just a diet or lifestyle, and this illness can manifest itself as a partial refusal to eat, alternating periods of overeating with periods of diligent fasting, all kinds of purges - from specially induced vomiting to taking laxative drugs.

The most common and at the same time dangerous RPP are:

- Anorexia nervosa is a mental illness that is more common in young adults and predominantly female adolescents.

This pathology is characterized by non-acceptance of one's external image, a conscious refusal to eat and the purposeful creation of obstacles to its absorption by the body. The result is a critical weight loss, but even then it seems to the patient that his body weighs unforgivably a lot and the fight against non-existent volumes must be continued. In some difficult cases, the disease becomes irreversible and leads to death. Note that the signs of the disease are easy to recognize, because anorexics do not notice their problem and, accordingly, do not hide.

This pathology is characterized by non-acceptance of one's external image, a conscious refusal to eat and the purposeful creation of obstacles to its absorption by the body. The result is a critical weight loss, but even then it seems to the patient that his body weighs unforgivably a lot and the fight against non-existent volumes must be continued. In some difficult cases, the disease becomes irreversible and leads to death. Note that the signs of the disease are easy to recognize, because anorexics do not notice their problem and, accordingly, do not hide. - Bulimia is the opposite of anorexia and is much more difficult to recognize. The disease is characterized by uncontrolled bouts of appetite and overeating, after which the person feels an acute sense of guilt and gets rid of what he has eaten through vomiting or laxatives. People with bulimia are usually overweight and do not differ from healthy people in their behavior during the absence of attacks.

- Binge eating disorder is an eating disorder in which binge eating episodes occur episodically.

Unlike patients with bulimia, those suffering from this type of eating disorder do not accompany binge eating with gastrointestinal cleansing or fasting, but experience psychological discomfort, guilt, and self-loathing.

Unlike patients with bulimia, those suffering from this type of eating disorder do not accompany binge eating with gastrointestinal cleansing or fasting, but experience psychological discomfort, guilt, and self-loathing. - Orthorexia - an eating disorder in which proper nutrition becomes the meaning of life. People stop experiencing the pleasure of delicious food, limit the choice of their products, focusing only on their useful qualities. If this desire had a measure, it would be worthy of praise. But patients are in constant fear of the possibility of breaking the rules and feel self-hatred when using prohibited products.

Photo: PhotoMIX-Company/Pixabay

Causes of ED

An eating disorder is a psychological pathology and can be activated for various reasons. It can be stress, hereditary factors, psychological trauma in children, aspects of education, promoted beauty standards imposed by society.

There is also a professional risk zone. These are specialties that imply maintaining an impeccable appearance - models, actors, ballerinas, athletes, stewardesses, television presenters.

These are specialties that imply maintaining an impeccable appearance - models, actors, ballerinas, athletes, stewardesses, television presenters.

The task of the psychotherapist is to find the causes of eating disorders in the process of consultation and psychological work with the patient, and then cure them, minimizing the risk of relapse.

It will be difficult for a simple person without special experience and education to figure out what exactly caused the mental disorder of his loved one, but it is in his power to notice alarming symptoms and begin to act.

What are the warning signs?

Warning symptoms are quite easy to detect in your loved ones, especially if you live together.

Here are the most common signs that a person has RPP.

Anorexia.

-

Abnormally low weight of a person - 15% of the error from the normal indicator.

-

The absence of three or more menstruation in girls.

-

Objective perception of one's mass and figure.

-

Focus on food.

-

Denial of the violation.

-

Suicidal thoughts.

-

Daily weighing on scales.

-

Avoiding eating in public.

-

Rituals while eating (for example, thoroughly chewing food).

Bulimia.

-

Uncontrolled amount of food consumed.

-

The systematic use of methods for cleaning the body of food - taking laxatives and diuretics, inducing vomiting, intense physical activity, fasting or dieting.

-

Low self-esteem is directly related to your own body weight.

-

Blood vessels often burst, the eyes turn red.

-

The habit of eating alone.

-

Deterioration of relationships with friends and family.

-

Disappointment after eating.

-

Pain in the stomach.

-

Poor condition of the teeth (gastric juice during vomiting thins the tooth enamel).

Overeating.

-

Excess food ingested uncontrollably.

-

Inability to control appetite.

-

During meals, food is practically not chewed.

-

Preoccupation with the proportions of one's figure.

-

Low self-esteem, a tendency to blame yourself for weakness and depression.

-

Overeating embarrassment.

-

A person hides food from other family members.

-

Problems with the gastrointestinal tract - pain, constipation.

-

Frequent diets that end in failure.

-

The cult of food (for example, careful table setting or the division of food according to color).

If you see this behavior in your loved ones, under no circumstances take the position of accusation. Try to reassure the patient, tell him that you are worried about his poor sleep or poor nutrition and would like to help.

How exactly can you help a loved one with an eating disorder?

To take care of the health of loved ones and help them overcome the disease, the following recommendations will help:

- Give your loved one the confidence that you care about his problems, you are always there and ready to listen and support. The very opportunity to consult with someone will give confidence and activate the desire to begin treatment. In a conversation, try to avoid criticism and admonitions - patients already constantly feel guilty and reproach themselves for weaknesses and behavior.

- Be patient. Your tantrums and anger will not help in any way in solving the problem. And a loved one, even without you, has already put forward punitive accusations and a sentence against him.

- Do not pressure or insist on instant action. It must be remembered that a sick person needs a significant time period to accept the fact of his illness and want to be treated. Persistence will only cause aggression and frighten away the positive tendencies of trust between you.

- Never try to analyze the patient's appearance. It will also make the path to healing more difficult and undermine your loved one's confidence even more. Instead of talking about weight and figure, it’s better to tell how you are worried about his health and want to help correct his mood.

- Support conversations about nutritional control. Let the person close to you understand that you are at the same time and feel your support. Believe in success and constantly encourage the patient with assurances that everything will work out.

- Try to persuade your loved one to see a specialist. An eating disorder is a real illness, not a loss of control over your diet. It is important to find the cause of the disease, to correct self-perception and self-esteem.

Such actions can only be done by an experienced doctor.

Such actions can only be done by an experienced doctor.

Which doctor should I contact with an eating disorder?

With RPP, you need to see a doctor, this is a serious disease and self-medication will be the height of irresponsibility. Such disorders are treated by a psychotherapist or psychiatrist.

The most effective treatment is a combination of psychotherapeutic conversation and medication.

Photo: canva.com

Persuade a loved one to see a doctor. Calm his fears, tell him that he will be listened to attentively and respectfully at the consultation and will be helped. Encourage that his illness is being treated and the sooner you start, the sooner the long-awaited relief will come.

How to find a doctor?

Try to get information about the experience and special education of the doctor, look for patient reviews on social networks.

People suffering from eating disorders need sensitivity and support, so it is necessary to find a therapist who has experience and cases of positive dynamics in this particular direction.